Abstract

Due to changes in the delivery of health care and in society, medicine became aware of serious threats to its professionalism. Beginning in the mid-1990s it was agreed that if professionalism was to survive, an important step would be to teach it explicitly to students, residents, and practicing physicians. This has become a requirement for medical schools and training programs in many countries. There are several challenges in teaching professionalism. The first challenge is to agree on the definition to be used in imparting knowledge of the subjects to students and faculty. The second is to develop means of encouraging students to consistently demonstrate the behaviors characteristic of a professional - essentially to develop a professional identity.

Teaching of professionalism must be both explicit and implicit. The cognitive base consisting of definitions and attributes and medicine’s social contract with society must be taught and evaluated explicitly. Of even more importance, there must be an emphasis on experiential learning and reflection on personal experience. The general principles, which can be helpful to an institution or program of teaching professionalism, are presented, along with the experience of McGill University, an institution which has established a comprehensive program on the teaching of professionalism.

Keywords: Professionalism, teaching professionalism, professional identity, medical curriculum

“Teaching professionalism is not so much a particular segment of the curriculum as a defining dimension of medical education as a whole” (Sullivan WM, 2009, p. xi).

Why teach Professionalism?

The past half century has seen major changes in the practice of medicine. The explosion of science and technology, as well as the development of multiple specialties and sub-specialties, has made the profession both more diverse and disease oriented (Starr, 1984). The increased complexity of care and its cost have brought third party payers, either governments or the corporate sector, into the business of health. Society has also changed. Starting in the 1960s all forms of authority were questioned, including the professions (Krause, 1996; Hafferty & McKinley, 1993). Medicine in particular was seen as self serving rather than promoting the public good and was felt to self-regulate poorly with weak standards applied irregularly. There was a feeling that the professions did not deserve the trust or their privileged position in society. As a result medicine began to examine the threats to its professionalism and, starting in the mid-1990s, realized that if professionalism was to survive, action would be required. It was concluded that one important step would be to teach professionalism explicitly to students, residents, and practicing physicians (Cruess & Cruess, 1997a; Cruess & Cruess, 1997b; Cohen, 2006). In many western countries this has become a requirement for accreditation of medical schools and training programs. There has been an amazing increase in the medical literature on professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society, as well as how best to teach and evaluate professionalism (Cruess et al., 2009; Stern, 2005; Hodges et al., 2011).

The Challenges

There are several challenges inherent in teaching professionalism (Cruess et al., 2009; Cruess & Cruess, 2006). The first is to obtain agreement on a definition. The next is how best to impart knowledge of professionalism to students and faculty. Of great importance is how to encourage those behaviors characteristic of a professional (developing a professional identity). Traditionally professionalism was taught by role-models (Wright et al., 1998; Kenny et al., 2003; Cruess et al., 2008). This is still an essential method but it is no longer sufficient. Both faculty, many of whom are role-models, and students should understand the nature of contemporary professionalism. In the literature there are two approaches to teaching professionalism; to teach it explicitly as a series of traits (Swick, 2000) or as a moral endeavor, stressing reflection and experiential learning (Coulehan, 2005; Huddle, 2005). Neither alone is sufficient. Teaching it by providing a definition and listing a series of traits gives students only a theoretical knowledge of the subject. Relying solely on role modeling and experiential learning is selective, often disorganized, and actually represents what was done in the past. Both approaches must be combined in order that students both understand the nature of professionalism and internalize its values (Ludmerer, 1999).

The first step to be taken in teaching professionalism is to teach its cognitive base explicitly. (Cruess et al., 2009; Cruess & Cruess, 2006) This will allow both faculty and students to have the same understanding of the nature of professionalism and share the same vocabulary as they reflect upon it. A medical institution should therefore select and agree on the definition of a profession and its attributes. There is some confusion in the literature on the exact nature of the words profession and professionalism, with some believing that it is difficult to define professionalism as it is too complex and context driven. There are however several definitions available, and all contain similar content (Stern, 2005; Swick, 2000; Steinert et al., 2007; Sullivan and Arnold, 2009; Todhunter et al., 2011). There are also attributes, drawn from the literature, which outline what is expected of a medical professional and these can form the basis of identifying the behaviors which reflect these attributes (Cruess et al., 2009).

Profession and Professionalism

The literature contains many definitions which can serve as the basis of the teaching of professionalism. While the arrangement of the words may vary, the content of these definitions is remarkably similar. The International Charter on Medical Professionalism (Brennan et al., 2002), the Royal College of Physicians of London (2005), Swick (2000), Stern (2005) and others have published acceptable definitions. We developed and published the following definition of profession which has served us well in our teaching programs (Cruess et al., 2004).

Profession: An occupation whose core element is work based upon the mastery of a complex body of knowledge and skills. It is a vocation in which knowledge of some department of science or learning or the practice of an art founded upon it is used in the service of others. Its members are governed by codes of ethics and profess a commitment to competence, integrity and morality, altruism, and the promotion of the public good within their domain. These commitments form the basis of a social contract between a profession and society, which in return grants the profession a monopoly over the use of its knowledge base, the right to considerable autonomy in practice and the privilege of self-regulation. Professions and their members are accountable to those served, to the profession and to society.

Professionalism as a term is obviously derived from the word profession. The definition provided by the Royal College of Physicians of London is useful for teaching (2005).

Professionalism: A set of values, behaviors, and relationships that underpins the trust that the public has in doctors.

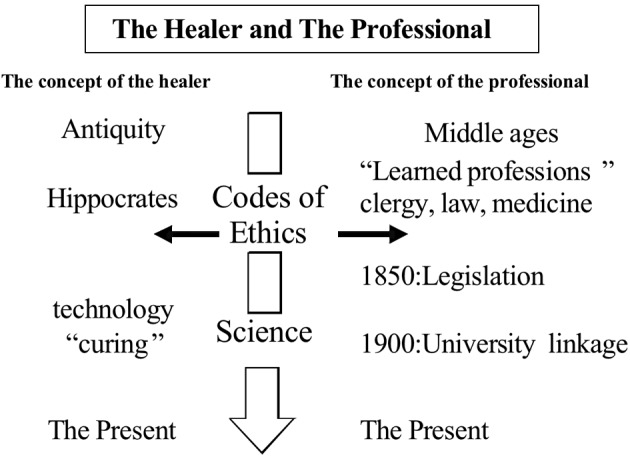

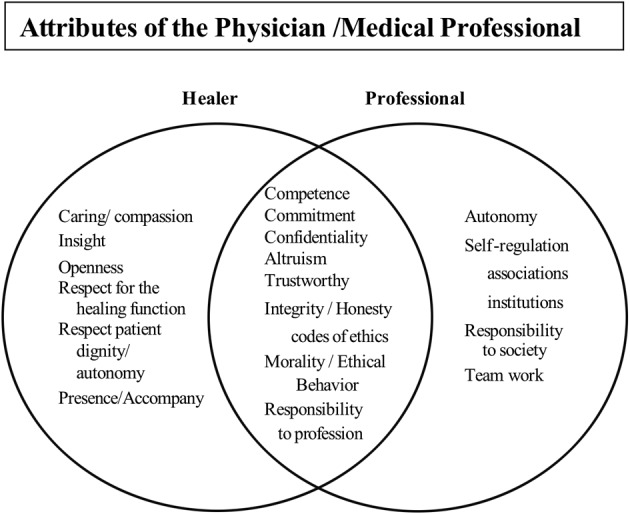

We believe that physicians serve two separate but interlocking roles as they practice medicine, those of the healer and the professional (Figure 1). While they cannot be separated in practice, for teaching purposes it is useful to distinguish them (Cruess et al., 2009). The healer has been present since before recorded history and the characteristics of the healer appear to be universal. In every society those who are ill wish healers to demonstrate competence, caring and compassion, and treat them as individuals. While the word profession has been used since the time of Hippocrates, the modern professions arose in the guilds and universities of medieval England and Europe (Starr, 1984; Hafferty & McKinley, 1993). The medical profession had little impact on society until science provided a base for modern medicine and the Industrial Revolution provided sufficient wealth so that health care could actually be purchased. At this time, society turned to the pre-existing professions and organized the delivery of healthcare around them by granting licensure. This provided a monopoly over practice, considerable autonomy, the privilege of self-regulation, and financial rewards. The attributes of the healer and of the professional are shown in Figure 2. Together, they outline societal expectations of individual physicians and the medical profession under medicine’s social contract.

Fig. 1. The healer and the professional have different origins and have evolved in parallel but separately. As shown on the left, all societies have required the services of healers. The western tradition of healing began in Hellenic Greece and is the part of the self image of the medical profession. Curing came possible only with the advent of scientific medicine. The modern professions arose in the guilds and universities of medieval Europe and England. They acquired their present form in the middle of the nineteenth century when licensing laws gave medicine. Its monopoly in practice.

Fig. 2. The attributes traditionally associated with the healer are shown in the left hand circle and those with the professional on the right. As can be seen, there are attributes unique to each role. Those shared by both are found in the large area of overlap of the circles. This list of attributes is drawn from the literature on healing and professionalism.

The definitions and list of attributes which serve as the basis of the cognitive base should be taught as early as possible in the curriculum and expanded in later sessions to reinforce the knowledge base and provide experience in using the vocabulary. As students gain experience, the concept of the social contract between society and medicine (Cruess & Cruess, 2008) can be introduced. Sociologists tell us that society uses professions to organize the essential complex services that it requires, including those of the healer. It has been described by Klein (2006) as a “bargain” in which medicine is granted prestige, autonomy, the privilege of self-regulation and rewards on the understanding that physicians will be altruistic, self-regulate well, be trustworthy, and address the concerns of society. Although it is not a written contract with deliverables, there are reciprocal expectations and obligations on both sides. The concept of the social contract assists in introducing the obligations of a physician arising from the contract and provides a justification for their presence. In addition, as medicine and society change, the contract, as well as the professionalism which is linked to it, must evolve.

Developing professional identity

As experience in teaching professionalism has been gained, the realization has grown that the educational objective is to assist students as they develop a professional identity, a process that we are only beginning to understand. Identity can be defined as: “A set of characteristics or a description that distinguishes a person or thing from others” (Oxford Dictionary, 1989). Students enter medicine with an established identity and wish to acquire the identity of a physician. Professional identity formation is an evolving process that involves “a combination of experience and reflection on experience” (Hilton & Slotnick, 2005).

Professional identity develops through socialization which is”the process by which a person learns to function within a particular society or group by internalizing its values and norms” (Oxford Dictionary, 1989). Students must understand the identity they are to acquire and must be exposed to the experiences necessary for the formation of this identity (Hafferty, 2009). Finally, they require time to reflect on these experiences in a safe environment. Fundamental to the process is the presence of role models who demonstrate the behaviors characteristic of the healer and the professional in their daily lives. Finally, the learning environment must be supportive of the development of a professional identity. Teaching institutions are responsible for providing this environment, something that requires them to pay attention to the formal, the informal and the hidden curricula.

General principles

When an institution initiates a program of teaching professionalism, experience has shown that there are some general principles that are useful to follow (Cruess & Cruess, 2006).

Institutional Support

It is difficult to initiate a major teaching program without the support of the Dean’s office and of the Chairs of the major departments. As many bodies accrediting teaching and training programs now require professionalism to be taught and evaluated, administrative and financial support is becoming somewhat easier to obtain. Time must be mobilized in the curriculum, although experience has shown that the amount of additional time required is often not great. Most faculties already have activities taking place whose objective is to develop the professionalism of its students. These can frequently be reorganized into a coherent course to which can be added new learning experiences. In addition some administrative and financial support is almost always required.

Allocation of responsibility for the program

Someone must be responsible for the program and accountable for its performance. Ideally a respected member of the faculty is chosen to lead the design and implementation of the professionalism program and be its champion. In addition the program can benefit from the presence of an advisory committee with broad representation from the faculty. It must be remembered that professionalism crosses departmental lines and ideally exposure to it should come within the context of many departmental activities.

Continuity

The definition, attributes, and behaviors serve as the basis for instruction at all levels – undergraduate, postgraduate, and practicing physician. Ideally they should inform the admission policies of the medical school, be used for teaching students, residents, and faculty, and for continuing professional development. The unifying theme is a common understanding of nature of professionalism. How it is taught and evaluated will vary depending upon the educational level. There is general agreement that “stage appropriate educational activities”, including assessment, should be devised and that they should represent an integrated entity throughout the continuum of medical education.

Incremental Approach

A comprehensive program for teaching professionalism is difficult to implement at all levels simultaneously. One should start with those activities devoted to the teaching of professionalism that are already in place. New programs often represent a combination of these activities and new learning experiences developed to complement what was previously taught. Once the objectives for the program on teaching professionalism have been developed, the program can be designed and introduced in incremental fashion.

The Cognitive Base

It is important to outline precisely what is to be taught. Thus, the cognitive base requires special attention. The definitions and attributes of the professional, which are to be the foundation of the teaching program, should be developed within the institution and general agreement on the educational approach to the subject obtained. Both the medical school and its teaching hospitals should participate in this process as all share the responsibility to understand and articulate what is expected of both students and faculty. The cognitive base must be taught explicitly and often, with increasing levels of sophistication appropriate to the student’s level of learning.

Experiential learning and Self-Reflection

The introduction of the cognitive base provides learners with both knowledge of the nature of professionalism and its value system. Medicine’s values must then be internalized so that they can serve as the foundation of a professional identity (Hafferty, 2009). There is wide consensus that students must experience situations in which these values become relevant or challenged as a necessary first step in the process of internalization. Learners must also have opportunities and time to reflect upon these experiences in a safe environment (Schon, 1987; Epstein, 1999). Teaching programs should ensure that students are exposed to the wide variety of experiences necessary to encompass knowledge of professionalism. The majority of these encounters will be true clinical situations, but in many instances they can be supplemented with reflection on experience from simulated clinical situations, small group discussions, clinical vignettes, role plays, film and video tape reviews, narratives, portfolios, social media, or directed reading (Cruess & Cruess, 2006).

The experiences used in teaching professionalism should be appropriate to the level of the student (Rudy, 2001). Reflection can be during the experience, on the experience, or after it has occurred, considering how action might differ in similar situations in the future.

Role Modeling

Role models must understand what aspects of professionalism they are modeling and be explicit about what they modeling (Cruess & Cruess, 2006; Wright et al., 1998; Kenny et al., 2003). Faculty development is often required to provide role-models with knowledge of the cognitive base of professionalism (Steinert et al., 2007). The role-modeling of faculty should be assessed and there must be positive or negative consequences to the evaluation (Cruess et al., 2008). Role-models should be supported and good role-models rewarded, poor ones remediated, and those who have demonstrated that they cannot be a good role model removed from teaching.

Evaluation

Both the cognitive base and the behaviors reflective of professional attributes must be evaluated, obviously using different methods. Knowledge can be tested in the traditional ways, including multiple choice questions, essays, short answers etc. It has become clear that professional attitudes and values cannot be reliably evaluated. It is therefore necessary to develop a series of observable behaviors which reflect the attitudes and values of the professional that can be evaluated (Stern, 2005; Hodges et al., 2011). It has also been recognized that only by carrying out multiple observations by multiple observers can reliable and valid results be obtained. Tools have been developed in order to accomplish this, and they should be used to evaluate students, residents, and faculty.

The evaluation of behaviors should be formative as this supports the learning process (Sullivan & Arnold, 2009). Summative evaluation must also be done on students and residents as it is the responsibility of the profession to protect the public from unprofessional practitioners. The professionalism of faculty members must also be assessed (Todhunter et al., 2011). It is a universal complaint of students that they are encouraged to behave professionally but frequently are exposed to unprofessional conduct on the part of their teachers (Brainard & Bilsen, 2007). Assessment of faculty performance offers a possible means of correcting this.

The Environment

The environment in which learning takes place can have a profound positive or negative impact on learning. There are three major components to this environment: the formal, the informal, and the hidden curricula (Hafferty & Franks, 1994; Hafferty, 1998). The formal curriculum consists of the official material contained in the mission statement of an institution and its course objectives. It outlines what the faculty believes they are teaching. The informal curriculum consists of unscripted, unplanned, and highly interpersonal forms of teaching and learning that takes place in classrooms, corridors, elevators - indeed any place where students and faculty have contact. It is here that role models exert their positive or negative influence. Finally, the hidden curriculum functions at the level of the organizational structure and culture of an institution. Allocation of time to certain activities, promotion policies and reward systems, that, for example, rewards research rather than teaching, can have a profound impact on the learning environment. This impact is felt disproportionately in the area of professionalism, which is so heavily dependent upon values. As a part of the establishment of any teaching program on professionalism, all elements of the curriculum must be addressed in order to ensure that they support professional values.

Faculty Development

Faculty development is fundamental to the establishment of a program of teaching professionalism (Steinert et al., 2007). It promotes institutional agreement on definitions and characteristics of professionalism. It allows the faculty to develop methods of teaching and evaluation and, properly used can lead to substantial changes in the curriculum. Most importantly, it helps to ensure the presence of skilled teachers, group leaders, and hopefully role models.

The McGill Experience

In 1997 McGill instituted the teaching of professionalism and over the next six years, in an incremental fashion, developed a four year program on Physicianship (Cruess & Cruess, 2006; Boudreau et al., 2011; Boudreau et al., 2007). The concept includes the separate but overlapping roles of physicians as healers and as professionals. Through a series of faculty development workshops the faculty agreed upon the definitions to be used and the attributes to be taught and evaluated (Steinert et al., 2007). These became the basis for 1. the selection of students 2. the content of teaching and 3. of the evaluation of students, residents, and faculty.

Student selection

McGill changed its student selection process to one utilizing the multiple mini interview process (MMI) (Razack et al., 2009). The mini-interviews take place in a simulation center using actors. There are 10 stations, with each station designed to demonstrate the presence in the applicant of the behaviors found in a model physician. The purpose is to identify those candidates who already demonstrate the attributes of the healer and the professional and, importantly, to publicly indicate the importance of these attributes. For those students who are granted an interview, the MMI score contributes 70% of the candidate’s final ranking on the admission scale. Unpublished data indicates that the MMI scores correlate with clinical performance during medical school.

There are three major aspects to the undergraduate program; whole class activities on both the healer and the professional; unit specific activities in various departments; and a mentorship program. The faculty first identified those components that were already being taught (ethics, professionalism, narrative medicine, end-of-life care) and added the others as they were developed.

Whole class activities

In the undergraduate curriculum, a longitudinal course on Physicianship that the students are required to pass was developed and implemented (Cruess & Cruess, 2006; Boudreau et al., 2007; Boudreau et al., 2011). It contained two separate but overlapping blocks on the healer and the professional.

Whole class activities include lectures on the nature of professionalism. Of symbolic significance, the first lecture on the first day of class is a didactic session on professionalism which presents the definitions and vocabulary which will be used. This is followed by small group sessions with trained faculty that examines vignettes demonstrating good and poor professional behavior. The objective is to identify the attributes present in each, familiarizing students with the vocabulary and the use of the concept. Ethics lectures are given and are always followed by small group discussions. Communication skills are taught using the Calgary-Cambridge format (Kurtz & Silverman, 1996). The subjects covered in the bloc on the Healer are physician wellness, the perspective of both the doctor and patient in the doctor-patient relationship, working with members of the health care team, and analyzing the nature of suffering. Great emphasis is placed upon reviewing narratives of the experiences of both patients and physicians. Other whole class activities include the introduction to the cadaver as the student’s first patient as well as a body donor service developed by students to show appreciation for the donors of the bodies. There is a white coat ceremony given prior to entry into the clinical years. Palliative care is felt to emphasize the healer role and there are special reflective experiences in this domain with mentors. In the last year students attend seminars with the goal of uniting the healer and professionalism roles. Students are given a fuller exposure to the concept of medicine’s social contract with society and encouraged to reflect on which of the public expectations of the profession they will find difficult to fulfill and how they might overcome these difficulties. These discussions are guided by their mentors (Osler Fellows) who have been with them for all four years.

Unit specific activities

Each department is encouraged to develop unit specific activities on the roles of the healer and the professional. Departmental rounds are devoted to the subject, bedside discussions of conflicts in professionalism take place, and the professionalism of students is assessed on ongoing basis. Of necessity, there is less structure to unit-specific activities than is present in whole class activities, but they are of extreme importance in providing experiences upon which students reflect with their mentors.

Osler Fellows

A mentorship program was established with the mentors being given the title of “Osler Fellows”. They were selected from a list of nominations by students and faculty of those recognized as being outstanding teachers, practitioners and role models. Each Osler Fellow mentors six students throughout their medical school career. They are an important part of the teaching of professionalism as they have a series of mandated activities which must be carried out. A portfolio is instituted, with an emphasis on professionalism, and narratives are produced and reviewed. There are of course a host of unscheduled encounters during which the student and mentor establish a relationship. The Osler Fellows have a dedicated faculty development program to familiarize them with their roles (Steinert et al., 2010).

Postgraduate education

During postgraduate training, residents have several half day recall sessions each year (Snell, 2009). At one of these there is a review of the cognitive base of professionalism as many residents are from diverse backgrounds. It is important to provide a common vocabulary for use in training and practice. The review is followed by small group sessions including residents from different specialties who discuss their experiences of professionalism during residency with an emphasis on how they will meet their responsibilities to society. Residents are involved as group leaders for the undergraduate sessions, participate in the assessment of the professionalism of students and faculty, and sessions are held to assist them in understanding their roles as teachers and role-models. The subjects covered in other half-day sessions that relate to professionalism are ethics, malpractice, risk management, teamwork, communication skills, and their own wellness.

Conclusion

Teaching professionalism requires that each teaching community agree on the cognitive base - a definition of profession, the attributes of the professional, and the relationship of medicine to the society which it serves. These should be taught explicitly. The program should extend throughout the continuum of medical education and passing should be obligatory for progression to the next level. The substance of professionalism must become part of each physician’s identity and be reflected in observable behaviors. Professionalism should be taught as “an Ideal to be pursued” rather than as a set of rules and regulations (Cruess et al., 2000).

References

- Boudreau JD, Cassell EJ, Fuks A. A healing curriculum. Med Ed. 2007;41:1193–1201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau DJ, Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Physicianship- educating for professionalism in the post- Flexnerian era. Perspectives in Biol & Med. 2011;54:89–105. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2011.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard AH, Bilsen HC. Learning professionalism: a view from the trenches. Acad Med. 2007;82:1010–1014. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285343.95826.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan T. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician’s charter. Ann. Int. Med. 2002;136:243–246. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JJ. Professionalism in medical education, an American perspective: from evidence to accountability. Med Educ. 2006;40:607–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulehan J. Today’s professionalism: engaging the mind but not the heart. Acad Med. 2005;80:892–898. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching medicine as a profession in the service of healing. Acad Med. 1997;72:941–952. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Teaching Professionalism: general principles. Medical Teacher. 2006;28:205–208. doi: 10.1080/01421590600643653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Expectations and obligations: professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51:579–598. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Johnston SE. Professionalism – an ideal to be pursued. Lancet. 2000;365:156–159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism must be taught. BMJ. 1997;315:1674–1677. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7123.1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Role modeling: making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ. 2008;336:718–721. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39503.757847.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. Professionalism: a working definition for medical educators. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2004;16:74–76. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833–839. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73:403–407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafferty FW. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Professionalism and the socialization of medical students; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69:861–871. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafferty FW, McKinley JB. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1993. The Changing Medical Profession: an International Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton SR, Slotnick HB. Proto-professionalism: how professionalization occurs across the continuum of medical education. Med Ed. 2005;39:58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges BD, Ginsburg S, Cruess R, et al. Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Med Teach. 2011;33:354–363. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.577300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddle TS. Teaching professionalism: is medical morality a competency? Acad Med. 2005;80:885–891. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny NP, Mann KV, MacLeod HM. Role modeling in physician’s professional formation: reconsidering an essential but untapped educational strategy. Acad Med. 2003;78:1203–1210. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. The New Politics of the National Health Service. 5th ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Pub; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krause E. Death of the Guilds: Professions, States and the Advance of Capitalism, 1930 to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge reference observation guide: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programs. Med Ed. 1996;30:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludmerer KM. Instilling professionalism in medical education. JAMA. 1999;282:881–882. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Razack S, Faremo S, Drolet F, et al. Multiple mini-interviews versus traditional interviews: stakeholder acceptability comparison. Med Educ. 2009;43:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Physicians of London. Doctors in society: medical professionalism in a changing world. London UK: Royal college of Physicians of London; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy DW, Elam CL, Griffith CH. Developing a stage-appropriate professionalism curriculum. Acad Med. 2001;76:503. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200105000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon DA. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Towards a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Snell L. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Teaching professionalism and fostering professional values during residency: the McGill experience; pp. 246–263. [Google Scholar]

- Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Steinert Y, Boudreau D, Boillat M, et al. The Osler fellowship: an apprenticeship for medical educators. Acad Med. 2010;85:1242–1249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181da760a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert Y, Cruess RL, Cruess SR, et al. Faculty development as an instrument of change: a case study on teaching professionalism. Acad Med. 2007;82:1057–1064. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285346.87708.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DT. Measuring Medical Professionalism. New York NY: Oxford Univ Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan WM. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Introduction; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C, Arnold L. Cruess R.L., Cruess S.R., and Steinert Y (eds) “Teaching Medical Professionalism”. Cambridge Univ Press; 2009. Assessment and remediation in programs of teaching professionalism; pp. 124–150. [Google Scholar]

- Swick HM. Towards a normative definition of professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75:612–616. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todhunter S, Cruess RL, et al. Developing and piloting a form for student assessment of faculty professionalism. Advanc Health Sci Edu. 2011;16:223–238. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SM, Kern D, Kolodner K, et al. Attributes of excellent attending-physician role models. NEJM. 1998;339:1986–1993. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812313392706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]