Abstract

The research explored the link between type II Female Genital Cutting (FGC) and sexual functioning. This thesis summary thus draws from an exploratory ethnographic field study carried out among the Maasai people of Kenya where type II FGC is still being practiced. A purposely sample consisting of 28 women and 19 men, within the ages of 15-80 years took part in individual interviews and 5 focus group discussions. Participants responded to open-ended questions, a method deemed appropriate to elicit insider’s in-depth information. The study found out that one of the desired effects of FGC ritual among the Maasai was to reduce women’s sexual desire, embodied as tamed sexuality. This consequence was however not experienced as an impediment to sexual function. The research established that esteeming transformational processes linked with the FGC ‘rite of passage’ are crucial in shaping a woman’s femininity, identity, marriageable status and legitimating sexuality. In turn, these elements are imperative in inculcating and nurturing a positive body-self image and sex appeal and consequently, positive sexual self actualization. These finding brings to question the validity of conventional sexuality theory, particularly those that subscribe to bio-physical models as universal bases for understanding the subject of female sexual functioning among women with FGC. Socio-cultural-symbolic nexus and constructions of sexuality should also be considered when investigating psychosexual consequences of FGC.

Keywords: Female genital cutting, female circumcision, psychosexual effects, Maasai, sexual functioning

Introduction

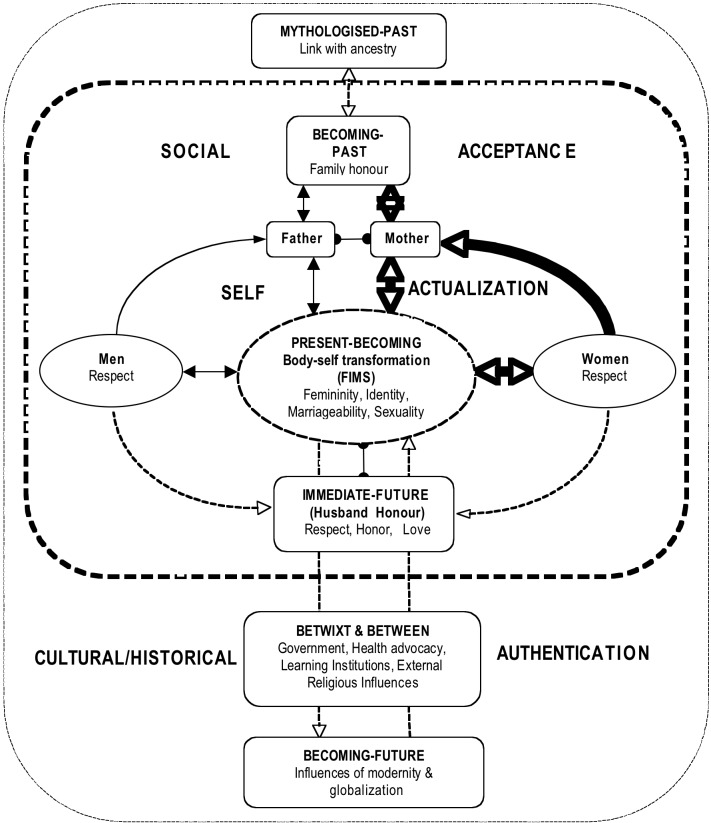

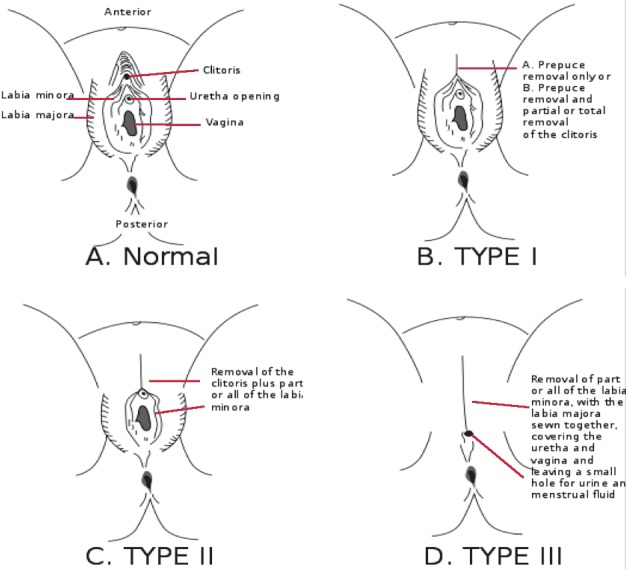

The procedure often referred to as Female Genital Cutting (FGC), Female Circumcision (FC), otherwise known as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), is defined by World Health Organization as “all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons” (WHO, 2010 p. 1). For the purpose of this work, we use the term FGC as we adopt a multi-faceted characterisation, defining it, first and foremost, as an operative procedure involving the partial alteration of external female genitalia, and secondly, as a culturally-sanctioned maturation ritual signifying the transition of girls to adult womanhood.

The World Health Organisation has classified the various forms of the procedure, narrowing the description into the four major categories (WHO, 2010). The first type, Type I, entails a form of FGC involving partial or total removal of the clitoral hood, sometimes accompanied by the removal of the clitoris, hence its popular label, Clitoridectomy. The second classification, Type II or Excision, refers to a form that involves partial or total removal of the clitoris and inner labia, in particular, the labia majora. The third type, Type III or Infibulation, is the kind of FGC that involves narrowing of the vaginal opening through the removal of all or part of the inner and outer labia, and usually the clitoris, and the fusion of the wound, leaving a small hole for the passage of urine and menstrual blood. The final category, Type IV; involves a variety of acts and ranges from symbolic pricking or piercing of the clitoris or labia, to cauterization of the clitoris, cutting into the vagina to widen it and introducing corrosive substances to tighten it.

Fig. 1. Batik Picture of Female Circumcision by Filex Jacobson, Sunset Art Studios, Arusha, Tanzania, Africa.

Prevalence of FGC

Although data on the prevalence of FGC is disputable (Meyers, 2000), it is estimated that 100-140 million women have been subjected to the procedure, with 3 million young girls under the age of 15 being at risk of joining their ranks each year (WHO, 2010). With regard to geographical spread, the practice persists mainly in Africa, as well as in the parts of Arabian Peninsula and Middle East. Undoubtedly, Africa is the continent with the highest FGC prevalence, estimated at 92 million circumcised girl and women (WHO, 2010). It is more accurate however, to view FGC as being practiced by specific ethnic groups, rather than by a whole country, as communities practicing FGC straddle national boundaries (UNICEF, 2008). There are differences along countries and ethnic lines regarding the prevalent FGC typology.

In Kenya, the nature of procedure varies across ethnic designations. Although FGC is still widely practised among the Kisii, Kalenjin, Maasai, Somali, Embu and Meru, there has been a notable reduction, since 1998, in the proportion of women being circumcised in almost every ethnic group, (KDHS, 2008). Overall, prevalence has reduced from 38% in 1998 to 32% in 2003 and further to 27% in 2008 among women aged 15-49 years. There is an even more prominent decline of FGC among younger women aged 15-19 years, a cohort that traditionally produced the highest numbers of FGC subjects. While 26 percent were circumcised in 1998, the numbers decreased to 20.3 percent in 2003 and further to 14.6 percent in 2008 (KDHS, 2008). Further reductions are anticipated following recent introduction of legislation criminalizing the practice; including the Children’s Act, the Sexual Offenses Act and the Female Genital Mutilation Act of 2011.

The FGC and FSF (Female Sexual Function) Debate: Dominant Epistemic and Discursive Strands

Esho et al. Afr Identities. 2010;8:221–34.

On the one hand, the practice of FGC is viewed as an infringement on women’s physical and psychosexual integrity. Numerous health complications have been observed to accompany various forms of the FGC procedure, including short and long-term physical and psychological traumata (WHO, 2010; Almroth et al., 2005; Dare et al., 2004; Okonofua et al., 2002; Shell-Duncan, 2001; Gruenbaum, 2001; Rahman and Toubia, 2000; Knudsen, 1994; Dirie and Lindmark, 1992). Women who have been subjected to the first and the second degrees of FGC, i.e. clitoridectomy and excision, are reported to having fewer complications as compared to the ones who have undergone the third degree, i.e. infibulations (Jaldesa et al., 2005). Various studies have shown that women with infibulation report more serious consequences reported such as menstruation problems, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility and the need for later surgery due to obstructed labour during child birth, difficulties with penetration during intercourse, and scarring or keloid formation during the process of healing on the perineum (WHO, 2010; Jaldesa et al., 2010; Almroth et al., 2005; Okonofua et al., 2002). FGC has also been viewed as encroaching upon the right of women to self-determination on matters pertaining to sexuality, sex and sexual expression. It is argued to dampen a woman’s sensual sensitivity and sexual appetite as part of a wider societal scheme to have men superintend over different aspects of women’s sexuality (WHO, 2010; Rahman and Toubia, 2001; Lightfoot-Klein, 1989; Lightfoot-Klein et al., 2000; Walker, 1992).

On the other hand, the above rationale is occasionally the object of a critical cultural relativist discourse. While not necessarily disagreeing with some of the anti-FGC group’s apprehensions about the practice, the FGC empathetic lobby takes issue with what it sees as a deliberate misrepresentation of the essence of this practice from the perspective of practicing communities (Njambi, 2004). The practice is considered to be deeply embedded in cultural values and traditions of practicing societies, serving as a key building block of and critical component in their survival (Malmström, 2009; Abusharaf, 2006). The critics of the anti-FGC lobby, contrarily, conceive FGC as having a positively determinative influence on women’s social and individual identity, and as well, being a contributory factor in the enhancement of individual bodily integrity (Shweder, 2000; Gruenbaum, 2001).

The Rationale for the study

The rationale for this study stemmed from what was seen as critical deficiencies in existing perspectives regarding the phenomenon of FGC and FSF. In particular, the thesis questioned the veracity of claims advanced to the effect that FGC is detrimental to integral processes of FSF. Such claims allude to a variety of physical and psychological trauma that are alleged to ensue following FGC, as an operative procedure imposed on external female genitalia (Elnashar et al., 2007; Almroth et al., 2005; Dare et al., 2004; Thabet and Thabet, 2003; Rahman and Toubia, 2000). Citing classical theoretical standpoints regarding the female sexual response cycle, including early biomedical models (Masters and Johnson, 1966; Kaplan, 1979) and more recently, bio-physical and incentive motivation models (Basson, 2001; Bancroft, 2002; Levin, 2002; Laan and Both, 2008), these paradigms emphasize the role that external genitalia play in the sexual response cycle and in determining the nature of the overall sexual experience. It presupposes that any operative procedure that alters aspects of genital physiology will compromise the cycle’s optimal functionality. The argument is advanced in relation to all forms of genital cutting, including FGC, especially as these involve excision of nerves that innervate the external genitalia (Einstein, 2008). Since such innervations constitute a key component in the sex response cycle, as receptors and transformers of sexual stimuli (Masters and Johnson, 1966), any tampering thereof is believed to have profound and adverse consequences on sexual behaviour, the latter manifesting itself in alleged victim’s inability to achieve arousal (El Defrawi et al., 2001; Karim, 1998) and derive pleasure from sex (Lightfoot-Klein, 1989; Rahman and Toubia, 2000).

Although persuasive in its own right, the foregoing paradigm is increasingly the object of reflection in contemporary critical discourse on female sexual function. Firstly, a key criticism relates to what we consider as the paradigm’s oversimplification of the sexual response cycle, and particularly the undue emphasis placed on external female genitalia as the exclusive determinant of sexual function. Critics highlight the important role that compensatory mechanisms of the nervous system and other psychological factors play in complementing any shortcomings arising from breaches in the bio-physical model of the sexual response cycle (Whipple and Komisaruk, 2002; Meston et al., 2004; Johnsdotter and Essen, 2004, Einstein, 2008). Secondly, when the bio-physical models are employed in FGC research, it poses numerous challenges due to the fact that it is challenging to objectively test sexual functioning of women with FGC, a culturally ingrained phenomenon (Esho et al., 2011). Other studies have also mentioned methodological challenges and shortcomings of FGC and sexual functioning research studies (Esho et al., 2011; Catania et al., 2007; Obermeyer, 2005). It is also instructive that whereas the bio-physical paradigm acknowledges that determinants of sexual functioning surpass instinctual bodily responses, little attempt is made to factor in the impact of external (contextual, societal, cultural and relational,) factors thereof (Laan and Both, 2008; Fourcroy, 2006; Obermeyer, 2005). Such factors are of significance in respect of transformational processes of the mind, and especially as they relate to the body and bodily function (Gruenbaum, 2001). It is no secret that psycho-social-relational factors such as self-image and partner relations, also play an important role in this regard (Meston et al., 2004; Mah and Binik, 2005). Therefore, the psycho-social-relational factors are deemed crucial intermediaries of sexual function, influencing the individual’s cognitive understanding, reinforcing sexual attitudes and behaviours, and scripts for appropriate sexual response (Bancroft, 2002).

The Pilot Study: Initial Experimentation with a Quantitative Research Methodology

Esho et al. Afr Focus. 2011;24:53-70.

The initial approach to the empirical component of this study entailed employing a hospital-based, case-control research, involving the use of psychometric instruments. This phase was implemented in July and August 2007 at the Narok district hospital in Kenya. We employed a quantitative research methodology aiming to verify the extent of genital cutting and compare with the women’s sexual functioning. The study used validated questionnaires, i.e. the Genital Self Image Scale (GSIS). The GSI scale is a 30 item survey that measured women’s attitudes toward their external genitalia, rating their feelings by classifying or agreeing with statements such as ‘unattractive’, ‘attractive’, ‘genital odour’ etc (Berman et al., 2003). We also used the questionnaire of Female Sexual Functioning Index (FSFI), a 19 item, multidimensional self-report questionnaire used to measure key domains of female sexual functioning such as ‘sexual desire’, ‘arousal’, ‘lubrication’, ‘orgasm’ ‘satisfaction’ and ‘pain’ (Rosen et al., 2000). The inclusion criteria for participants was as follows: married, sexually active and of reproductive age group.

We got a convenient sample of 11 women; their age ranging between 18-45 years old that had undergone FGC and only 4 without it as the control group with their age ranging from 18-25 years old. The women in the study were selected from the in-patient and outpatient clinics. They were informed about the research and asked to volunteer to be part of it with no form of motivation offered for their participation. All participants signed an informed consent form and anonymity was assured. Using SPSS, we found that the GSI scale of circumcised women was 36.8 while that of uncircumcised was 36.0 out of 63 total points. The total FSFI of circumcised women was 26.8 while that of uncircumcised women was 23.2 out of 36 total points. Therefore, our results indicated that circumcised women had a higher genital self-image and consequently a higher sexual functioning index as compared to uncircumcised counterparts.

It was not possible to draw strong statistical inferences in our findings for various reasons. Firstly, after a recruitment period of six weeks, the sample was too small and not representative of the general population. Difficulties were encountered in recruiting participants as not many women use health services for various socio-economic and cultural reasons. The women in the control group were few hence making it difficult to have a strong statistical significance in comparing the results of case and control groups. Secondly, conducting vaginal observations to verify the extent of cutting done to the genitalia was not welcome and therefore the extent of genital cutting could not be verified. Thirdly, the language of inquiry blocked communication between researchers and respondents since the questionnaires were in English while most participants could only speak Maasai language and Swahili, the Kenyan national language. The research questionnaires were thus not culturally sensitive to suit the context of our study. The challenge to translate them during the interviews for some participants was presented as some of the words could not be translated into the local language or into Swahili. This difficulty resulted from the fact that the survey instruments were based on Western concepts of sexuality and sexual functioning and thus do not fit to investigate sexuality in our context. Insights from this initial phase were however used to design the second phase of the project which was anthropological in orientation. Consequently, its execution necessitated the use of methods and procedures that are traditionally associated with ethnographic and qualitative research.

A Shift to a Qualitative Research: An Ethnographic Exploration

Esho et al. Afr Focus. 2011;24:53-70.

It is important to mention here that the object in this exploratory endeavour was not to achieve a statistical inference but rather a rich account of the subject. Consequently, the sampling was carried out purposive, taking cognizance of participants’ exposure to the FC ritual and knowledge of, and experience with sexuality. The study involved an in-depth exploration of the subject in the context of the Maasai community of East Africa (Kenya). Although there are significant changes in social and cultural spheres, a greater number of the community peoples still swear allegiance to traditions, customs and practices, a scenario that undoubtedly will continue to persist in the foreseeable future. Polygamy and FGC are some of the community’s most enduring practices.

The Maasai practice Type II of FGC. In spite of a decades-long, vibrant and dedicated eradication campaign, the Kenya Health Demographic Survey (2003) estimated a 93.9% prevalence of FGC amongst the Maasai of Kenya. The rates have shown a decline in recent years, with FGC prevalence rates dropping to 73.2% (KDHS, 2008). The apparent slow pace of the FGC campaign may point to shortcomings in abandonment strategies currently being pursued. Also it may attest to the fact that the critical significance of FGC relative to the overall culture of the Maasai has not yet been fully appreciated. Like in many other practicing communities, FGC amongst the Maasai, occupies a definitive position as a maturation ritual and/or ‘rite of passage’, ushering girls into womanhood and motherhood. This latter factor underscores the symbolism that the ritual bears relative to the women who persistently continue to subject themselves to all aspects of the ritual. Whatever the case, the research seeks to establish what function FGC has relative to the practice of sexuality, or at the very least in shaping the subjective sexual experiences thereof.

The actual research was carried out between July and August 2008, with the actual setting right at the heart of Kenya’s Rift Valley Province. The sample was drawn from Oloolongoi, a small village in Olpusimoru Location, Narok North District in Narok County. The area is sparsely populated, with a resident population density of about 36 inhabitants per square kilometre. A greater majority of inhabitants here were the Highland Maasai, specifically a segment of the community that has long traded nomadic pastoralism for a more sedentary lifestyle, and which now preoccupies themselves with crop cultivation and livestock rearing.

Research objective

It sought to explore the psychosexual experiences of Maasai women who have undergone FGC.

Research questions

Our research strategy and design was geared towards answering the following questions;

1. What is the significance of FGC amongst the Maasai?

2. What is the function of FGC with regards to matters of collective and individual sexuality?

3. How does FGC influence subjects’ characterisation of sexual experience?

Study Sample

A convenient sample consisting of 28 women was recruited from the area’s general population. The sample was varied in terms of age (15 to 80 years), educational background (different levels of literacy), and vocation (housewives, farmers, traders, professional teachers, traditional birth attendants, traditional circumcisers, etc). Such variation was necessary to guarantee a more balanced perspective concerning the subject. A small number of men (19) were also selected with a view to access the male perspective regarding the same. Although most participants championed the right of the community to preserve the ritual and practice of FC, they were all exposed to the ongoing national discourses concerning FC and were indeed aware of the FGC eradication campaign. They thus had the benefit of insight from both sides of the ensuing cultural debate.

Research methods and procedures

Open-ended guiding questions were used in this phase of the study. These questions were chosen for their capacity to reveal individual, social, and cultural significance of the practice of FGC but also their opinions regarding its eradication among the Maasai. All open-ended questions were first pre-tested on two female research assistants in order to make sure that they were suitable to be asked within the Maasai cultural context.

The research assistants were not experienced researchers but were well conversant with local norms and practices. They were trained briefly on how to conduct individual interviews and focus group interviews, the need to keep an open mind was emphasized, and to allow the participants to express themselves without leading them. They were also asked to refrain from providing their own ideas and experiences from during the discussions. These research assistants also translated the guiding questions into Maasai in order for the participants to understand clearly what was being asked.

The research employed individual interviews and focus group discussions. Both procedures aimed to access participants individual and shared perspectives regarding the subject under investigation. Individual open-ended questions were administered to the entire sample. Subsequently, some of them took part in five smaller focus group discussions, subject to availability. While the individual interviews lasted for about 25 to 60 minutes, the focus group interviews lasted for about 1 to 3 hours. The long discussions aided in making sure that the issues brought up are probed further until a point of saturation was achieved. The focus groups were homogenous separated by gender and not by age.

Fig. 2. A group of women after a focus group discussion. Research assistant (second left). Source: Field Survey by Esho 2008.

Moreover, the research incorporated an observation procedure entailing the researcher’s passive participation in a live initiation ceremony. The event, which took place during the period of the research, involved the circumcision of a fifteen year old girl. The aim of this latter procedure was to witness and verify the nature and extent of genital cutting imposed on subjects. Secondly, the researcher aimed to experience the dynamic surrounding the ‘day of circumcision’, an instant that symbolized initiates’ alleviation from girlhood status to womanhood. The opportunity was also used to briefly interview the circumciser, as well as a few selected respondents from amongst those witnessing the ritual. All procedures were conducted in the native Maasai language, although Swahili and English were deployed while interviewing younger and more literate respondents. Following respondents’ consent, responses and discussions were stored using a voice recorder and later transcribed verbatim prior to its analysis and interpretation.

Data analysis

The interpretative phase began with a systematic coding of outputs in order to allow key themes to emerge. As earlier mentioned, the research sought to explicate the interface between culture and sexuality. By exploring transformational processes linked to the FGC maturation ritual, and the symbolism that is attached to the accompanying bodily inscription (genital cutting), the study sought to determine the extent to which these act as intermediaries of sexual function amongst FGC subjects. This was carried out with the aid of MAXQDA, a computer aided analytical tool that translates flashes of insights in textual data into descriptive and theoretical codes. The tool, which facilitated a sentence by sentence processing (reading and re-reading) of textual data, assisted in generating recurrent patterns, with codes acting as building blocks for the construction of dominant themes. These themes were re-examined by three external auditors to validate them.

Results

In the following sections, we shall provide a synthesis of key findings as they respond to the three main research questions. The findings of the research are briefly presented in three successive analytical sections. The first we present the significance of FGC among the Maasai, using emerging insights in an initial attempt to deduce a conceptual model regarding the significance of the practice. Secondly, matters of individual and collective sexuality and the relationship between FGC and FSF are brought to the fore as informed by contextualized knowledge, attitudes and perspectives regarding the phenomenon. In the third and final section, we seek to culminate the argument by looking at the implications of the research findings with regards to the present and future circumstance of the Maasai.

Concerning the Significance of FGC amongst the Maasai: A Socio-cultural-symbolic Nexus

Esho et al. submitted.

This research established that among the Maasai, through FGC, culture plays a significant role in mediating processes of socialization and identity. These in turn act as intermediaries of female sexual functioning among others. In this framework, FGC serves a crucial element in legitimizing the status of womanhood, signifying the onset of puberty and fertility, and opening the door to matrimony and motherhood. The research unravelled that for the Maasai women the FGC ritual entraps the subject in a matrix of vertical and horizontal loyalties, upon which key parameters of femininity, identity, marriageable status and sexuality (FIMS) are negotiated, socially accepted and culturally authenticated.

We therefore used the matrix of vertical and horizontal loyalties (Figure 3) to explain the socio-cultural-symbolic significance of FGC in this community. Furthermore, it assists us in revealing the various ways in which a newly initiated woman’s position in the society is transformed just as much as her own self-image is transformed. The matrix is composed of three interconnecting realms, beginning with the inner core of self actualization, the context of social or communal acceptance and then a third encompassing one that indicates a framework of historical/cultural authentication.

Fig. 3. The Social-Cultural-Symbolic Nexus in FGC: The Matrix of Vertical and Horizontal Loyalties among the Maasai. Source: T. Esho, P. Enzlin & S. Van Wolputte (submitted).

The “vertical loyalty”, which through a time perspective, tracks historical and cultural aspects of social conventions, and norms. These in turn influences everyone in the society, subsequently informing sexual practices and experiences. It begins by providing the link between FGC and ancestry, whereby a mythologized past is brought into reality and then projected into the future. It tracks backwards the links between the initiate, her mother, her grandmother all the way back to her ancestors. The vertical loyalty ends by looking at the present influences of the practice by modern realities and then projects into the future, a future inevitably influenced by the maelstrom of globalization and modernity.

Subsequently, our study revealed how FGC is experienced by the individual through what was termed as “horizontal loyalty” and how this impacts on a woman’s individual identity, social identity, and also its role in legitimizing her sexuality. The findings of this research revealed that the significance of FGC to the initiate is a result of the transformational process that she undergoes both physically, psychologically and socially. In addition to guaranteeing the subject’s ascension to the elevated status of womanhood, the FGC ritual is likewise linked to esteeming processes in which the subject spruces up her individual image. In fulfilling this social requirement, the subject thereby earns the respect and admiration of her peers (both male and female), and that of the entire society.This has therefore been interpreted as the ”horizontal loyalty” referring to how FGC impacts on the initiate’s sense of self-identity and actualization based on and resulting from the change in being and the status of her social relationships with other women and men in the society and most of all, in her immediate future with her husband.

In our conceptual model therefore, the subject’s decision to undergo FGC, is in many ways regulated by the socio-cultural-symbolic nexus and thus the choice may not be entirely voluntary. The three realms, of individual self transformation, social acceptance and cultural and historical authentication merge to play a significant influence on a woman’s decision making. The intricacies of the socio-cultural symbolic nexus surrounding FGC thus come into play, and pressure to conform to social norms and conventions are immense.

The Function of FGC with Regards to Matters of Collective and Individual Sexuality

Esho et al. Afr Identities. 2010;8:221–34.

With regard to matters of individual and collective sexuality, our research showed that amongst the Maasai, culture informs collective and individual sexuality and its expression thereof. Here, the esteeming process referred to above becomes a basis for ingrained inter-subjective and intra-subjective ethics in respect of the conduct of sexual relations. Although there are no strict prescriptions against sexual encounters between (pre-puberty age) youngsters, it is considered a great taboo for a girl to conceive and assume parenthood prior to undergoing the FGC ritual. Were it to happen, such an eventuality almost certainly foretells a future of infamy and uncertain prospect for the mother and children born of such a state. For the young girls, these free sexual encounters come to an end with circumcision. Overall, the FGC ritual and procedure, as a bridge towards legitimizing of purposely sexual relations, marking the onset of culturally sanctioned matrimonial relations, procreation and parenthood are only conceived within the context of marriage.

Fig. 4. Time series pictures showing the progression of the witnessed circumcision ceremony from the beginning to the end. Source: Field Survey by Esho 2008.

Another insight, which is a key component in the Maasai social formation, relates to the function of culture in the establishment of social hierarchies and of associated relational canons. As a maturation ritual, the circumcision serves as the primary basis for determining and setting up age-related hierarchies. Although there is accepted gender parity in the formation of respective age-sets, female age-groups often mimic those of their male contemporaries. And whereas males retain the same age-group distinction once acquired, females, in spite of being inferior in age, reserve the right to upgrade to the husbands higher rank upon initiation into the status of womanhood through FGC and commencement of matrimonial relations. In essence, this may create a scenario whereby their status surpasses that of men with a significantly superior age-related ranking than her own initial one, especially when the former is inferior to that of her husband. By the same measure, she is considered mature enough to warrant the same level of regard as that accorded to her husband and his peers, male and female alike. Women who benefits from this principle however do not take it for granted, but rather they conduct themselves in a manner becoming of their newly acquired status, failure of which may dishonour the woman, spouse, extended family and host age-group.

The same stratification framework has significant implications with respect to the conduct of sexual relations in the framework of matrimony. The Maasai are evidently polygamous in matrimonial orientation, meaning that one man can have several wives. It is expected that the husband of many will adequately cater for all the needs of all his wives. Extra-marital relations are not formally sanctioned, although they are generally known to occur under the shroud secrecy. A rather peculiar exception to the principle is the acceptance of intra-group sexual relations involving couples of the same age-set. This provision is however not intended to be exploited to perpetuate promiscuity but rather has the function of servicing the wife of a long absent husband, or as a means by which a husband may conceal his impotence via proxy conception. In each case, such sexual relation or relations is usually consented by respective parties.

On the Nature of “Sex after the Cut”: Sex as a Social Construct

Esho et al. Afr Identities. 2010;8:221–34.

The main purpose of this research was to explore sexual experiences of women who have undergone FGC. Our findings suggest that in the context of the Maasai, the cultural symbolism of the broader ritual supersedes psychosomatic consequences, if any, of the associated bodily inscription and that in some instances, cultural vectors act as intermediaries of sexual function in this case, positively influencing the subject’s sexual experiences. Concerning the main aim of our research, the findings debunk the hypothesis that female Genital Cutting leads to Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD). This is so because sex for these Maasai women, is not experienced as a purely physiological concept but rather as influenced by culture and its discourse. By so stating however, it is necessary to exercise a great deal of precaution, given that these findings are limited to experiences of the Maasai community, which, as was mentioned earlier, practice type II form of genital cutting and is done to teenage girls who have been taught the cultural and physical essence of the practice.

These findings thus might not be applicable in the context of other FGC practicing ethnic groups. Even so, a critical examination of the social-cultural-symbolic nexus as it relates to FGC and FSF may serve to reveal unique, context-mediated circumstances that serve as the basis upon which optimal sexual function is conceived. Furthermore, and with regard to the relationship between FGC and FSF, the research found that culture, through FGC, assists in shaping attitudes, perspectives concerning the experience of sexuality. First and foremost, the research established that in accordance to esteeming processes earlier referred to, transformational processes linked with the FGC as a ‘rite of passage’ was imperative in inculcating and nurturing a positive body-self image and sex appeal. These were key factors that emerged in determining the nature of ensuing sexual encounters and in informing FGC subjects’ appreciation of the same. Respondents identified triggers of sexual desire and arousal as critical to the actuality of their experience of sexuality in view of their tamed sexuality. In this framework therefore, self-image (body-image) and partner relations were deemed to have a significant influence. Here, individual assessments concerning personal attractiveness and the nature of relationship to spouse (closeness, commitment, love, respect, and faithfulness) were deemed to not only enhance sexual appeal, but likewise interpenetrate with actual sexual technique to motivate and determine the overall quality of coital encounters.

Instructively, a wide consensus existed to the fact that such alteration had little impact on sexual response. All respondents (female and male) cited representations of what they deemed to be manifestations of optimal sexual functioning in female sexual experiences. The male response to the question of how women respond sexually was used to corroborate the female responses. Significantly, men showed no personal sexual preference for women who have not undergone ‘the cut’ over those that did, citing similarities in the overall quality of the sexual experience. This response was necessary as indicated that for Maasai men FGC did not particularly enhance their sexual pleasure. This is however, not to suggest that respondents were unaware of the significance of physiological and instinctual bodily functions in mediating sexual function. Furthermore, participating male and female respondents credited FGC with the partial loss of clitoral and labial sensitivities with slowed sexual responses. This however, did little to alter local perceptions regarding the quality of the sexual experience. For women on the one hand, tamed sexuality was considered natural while untamed sexuality was perceived as uncontrollable and thus un-natural. For men on the other hand, circumcision ascertains their sexual prowess. In her research among Egyptian women, Malmström (2009) defines female sexual urge as stronger than that of the males and thus, through FGC, female sexual desire is tamed in a bid to accord it with men’s sexual desire , by having the males appear stronger than that of females. This difference in the embodied sexual state is expected to be maintained, thus justifying a sexually subdued state for women. A woman is believed to be able to function appropriately, when she has more control of her sexual feelings. The function of FGC therefore is to control female sexuality which may seem negative. However, for the Maasai woman, such an outcome was appreciated and this control was not seen as an obstacle to sexual enjoyment.

Consequently, among Maasai women, our study showed that slow sexual desire and arousal necessitated longer foreplays, hence enhancing the quality of coitus. The same degradation of genital sensitivities was credited with giving women greater control over their sexual desires, thereby giving women more autonomy over their sexuality. Sexual function is therefore a highly complex phenomenon, the optimisation of which not only is dependent upon physiological and psychological processes of body and mind, but likewise is contingent upon a broader spectrum of factors, some of which are external to instinctual processes of body and mind.

The Present Borderland: Between Past and Present and Tradition and Modernity

Esho et al. Borderlands and frontiers in Africa. Berlin: LIT Verlag. 2011 (Book Chapter).

The culture of Maasai men and women who took part in this study, just like in other societies, has succumbed to the maelstrom of modernity, although in a way trying to maintain some aspects of what they deem crucial in their culture. Many changes were noted in their current way of life. One could be forgiven for misidentifying the local tribes-people, especially as they are clad in anything other than the characteristic red-cloth clad that many Kenyans and foreigners alike, have come to associate with the Maasai. Successive encounters confirmed that these people have long ditched their elaborate and ornamental raiment for the unembellished alien import that is the contemporary frock and suit. One cannot however fail to notice the latter’s grace, especially the beaded common Maasai accessories worn by women.. The men also carry a number of paraphernalia reminiscent of a Maasai moran or elder, including; a wooden club, a walking stick, a sheathed sword, and the occasional snuff bottle for the very elderly. A variety of visible body markings, suffice to convince a stranger that these are indeed Maasai tribesmen.

Modern and global changes are not only seen through the general Maasai way of life, but also in its body practices. Changes in the global context in policies and discourses also influence the meanings and significance of traditional practices such as FGC and consequently, the way the body and body practices are perceived. The resulting heightened state of uncertainties; necessitates a re-formulation and re-invention of body practices such as in the case of FGC. This research established that FGC, like other contemporary body practices plays a significant role among the Maasai.

Issues of femininity and identity are continually being questioned in the face of modern changing times. These changes are manifested in the way the practice is performed and experienced amongst women. Among the Maasai for instance the change from an older way of practicing FGC to a newer way referred to as Ilkirasha was noted. This style was argued to reduce negative health consequences of the procedure such as bleeding and infections, a response a reduce the medical complications discussed in the eradication discourse. As witnessed in the observed circumcision ritual, other changes were noted, such as the ceremony itself was low key, lest it attracted too much attention, from law enforcers since FGC was forbidden by the enactment of the Children’s Act of 2001 in Kenya. Such changes indicated that women are actively involved in re-inventing the practice. Female subjectivity and agency is practiced by these Maasai women in search of identity and social status, in the light of modern global discourse.

Our study revealed the contemporary condition of the African woman being in a state of suspension in a borderland, being betwixt and between different frontiers; of past and present, tradition and modernity, masculine and feminine, amongst other extremities in the pressure to capitulate to the contemporary maelstrom of modernity and a globalizing western culture. Borderlands within which a transformation into adulthood takes place serve as a significant part of Maasai women’s lives. The findings revealed that FGC especially amongst Maasai women attempts to synergise and consolidate from both the current ongoing social, cultural, political and economic developmental progression into modernity as well as what they believe to be important tradition values. Traditions themselves are a product of modernity and in a way only mirror the past. It is thus crucial for researchers to consider the differences on the level of discourse and practice in the various FGC practicing communities especially regarding FGC’s impact on sexual function.

Conclusions

By way of concluding, the above-mentioned findings are of importance for conventional understandings regarding sexuality in general, and in particular, the relationship between culture, FGC and sexual functioning. The findings of our study negate the hypothesis that female Genital Cutting leads to Female Sexual Dysfunction. In essence, they imply that certain externalities override innate bio-physical-psychological factors in mediating the experience of sexuality. This in itself is not a new finding, as both social-relational and contextual environmental factors are known to have a determinative role in influencing sexual function. In the case of the Maasai, however, social-cultural factors, namely, ritual and symbol, as well as relational canons emanating from the community’s elaborate and hierarchical social structure, have greater prominence in mediating sexual relations. Such is especially true regarding FGC, where as the findings reveal, the cultural symbolism of the broader ritual supersedes psychosomatic consequences of associated bodily inscription. This latter finding brings to question the validity of conventional sexuality theory, particularly those that subscribe to bio-physical models as universal bases for understanding the subject of female sexual functioning among women with FGC. In our interpretation of research findings, we have provided an alternate lens by which to explore the phenomenon of female sexual function amongst the Maasai, and in particular, amongst women who have undergone type II FGC procedure. Consequently, we have provided what we consider to be cultural bases for self and collective constructions and understanding of sexuality, and hence sexual experiences.

A major limitation of our study is that its findings regarding FGC and FSF cannot be generalized to all FGC practicing communities. FGC and sexuality is practiced and experienced differently in various peoples, cultures and regions. We thus propose further exploration of the FGC implications in relation to women’s sexual experiences in other groups in order to validate our findings.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible were it not for funding from IRO (KUL) and VLIR-SRS scholarships that assisted in funding the research and its completion respectively.

What is already known ?

Notwithstanding worldwide condemnation and legislation in all countries to forbid this practice, Female Genital Cutting (FGC) is still being performed, albeit at a reduced rate, mainly in Africa and some countries of the Middle East. It is estimated that 3 million young girls under the age of 15 are at risk of being the victim of this practice.

Apart from the cruelty of FGC, as it is currently still practised, it is generally accepted that this procedure is also associated with deleterious consequences such as serious bleeding, infection, menstrual problems, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, obstetrical problems and difficult and sexual penetration.

FGC is also considered as the expression of the dominance of male-centred traditions negating the right of women’s self-determination.

Finally, it is thought that FGC hampers a woman’s fulfilment of sexual gratification.

It is exactly this aspect that has been studied and challenged in this PhD thesis.

What is new from this research ?

A rather limited sample of women with FGC (n = 11) and an even smaller group of controls (n = 4) was investigated using psychometric instruments such as the Genital Self Image Scale the Female Sexual Functioning Index.

Circumcised women scored somewhat higher on both scales. Although not significant in a statistical sense, these results contradict the traditional view that FGC impacts negatively on a woman’s self-image and sexual gratification and challenge the biomedical models proposed by Masters and Johnson and the more recent bio-physical and incentive motivation models of the female sexual response cycle.

In a second part, an in depth interview and focus group discussions were performed with 28 women of various age and educational and professional background and with 19 men to explore their perspective with regard to FGC.

From this study it appears that circumcised women do not consider FGC as a practice imposed by cultural tradition or the expression of male dominance. On the contrary, they seem to appreciate this practice as a necessary step to womanhood and integration within their society.

Which questions will these new findings arise ?

This thesis is highly controversial because it seems to lend support to the defenders of FGC, who consider this practice to be embedded in cultural values and traditions and which has a positive influence on women’s social and individual identity.

This view has to be balanced against the cruelty of the practice, its violation of the bodily integrity and the sometimes severe complications. For all these reasons, FGC is condemned worldwide.

On the other hand, mere prohibition of FGC is not sufficient because the practice still goes on as FGC plays an important role in some cultures for a woman’s acceptance and integration in her society.

Studies like this can be helpful to understand the rationale and the woman’s perception of FGC.

The challenge will be to investigate how education, rather than prohibition, can help to find substitutes for this cruel but apparently useful ritual symbol.

M. Dhont

What is already known

Notwithstanding worldwide condemnation and legislation in all countries to forbid this practice, Female Genital Cutting (FGC) is still being performed, albeit at a reduced rate, mainly in Africa and some countries of the Middle East. It is estimated that 3 million young girls under the age of 15 are at risk of being the victim of this practice.

Apart from the cruelty of FGC, as it is currently still practised, it is generally accepted that this procedure is also associated with deleterious consequences such as serious bleeding, infection, menstrual problems, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, obstetrical problems and difficult and sexual penetration.

FGC is also considered as the expression of the dominance of male-centred traditions negating the right of women’s self-determination.

Finally, it is thought that FGC hampers a woman’s fulfilment of sexual gratification. It is exactly this aspect that has been studied and challenged in this PhD thesis.

What is new from this research

A rather limited sample of women with FGC (n = 11) and an even smaller group of controls (n = 4) was investigated using psychometric instruments such as the Genital Self Image Scale the Female Sexual Functioning Index.

Circumcised women scored somewhat higher on both scales. Although not significant in a statistical sense, these results contradict the traditional view that FGC impacts negatively on a woman’s self-image and sexual gratification and challenge the biomedical models proposed by Masters and Johnson and the more recent bio-physical and incentive motivation models of the female sexual response cycle.

In a second part, an in depth interview and focus group discussions were performed with 28 women of various age and educational and professional background and with 19 men to explore their perspective with regard to FGC.

From this study it appears that circumcised women do not consider FGC as a practice imposed by cultural tradition or the expression of male dominance. On the contrary, they seem to appreciate this practice as a necessary step to womanhood and integration within their society.

Which questions will this new findings arise

This thesis is highly controversial because it seems to lend support to the defenders of FGC, who consider this practice to be embedded in cultural values and traditions and which has a positive influence on women’s social and individual identity.

This view has to be balanced against the cruelty of the practice, its violation of the bodily integrity and the sometimes severe complications. For all these reasons, FGC is condemned worldwide.

On the other hand, mere prohibition of FGC is not sufficient because the practice still goes on as FGC plays an important role in some cultures for a woman’s acceptance and integration in her society.

Studies like this can be helpful to understand the rationale and the woman’s perception of FGC.

The challenge will be to investigate how education, rather than prohibition, can help to find substitutes for this cruel but apparently useful ritual symbol.

Promotor: Enzlin P., Department of Reproduction, Development and Regeneration, Institute for Family and Sexuality Studies, Catholic University of Leuven, Kapucijnenvoer 35, Blok D – Bus 07001, BE-3000 Leuven, Belgium; Context –Centre for Marital, Family and Sex Therapy, Department of Psychiatry, UPC Catholic University of Leuven, Kapucijnenvoer 35, Blok D – Bus 07001, BE-3000 Leuven, Belgium.

Co-promotor: Van Wolputte S., Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, Institute for Anthropological Research in Africa, Faculty of Social Sciences, Catholic University of Leuven, Parkstraat 45, Bus - 3615, 3000 Leuven, Belgium.

Co-promotor: Temmerman M., Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, International Centre for Reproductive Health, University Hospital Ghent, De Pintenlaan 185 P3, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium.

References

- Abusharaf R. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania press; 2006. Introduction: The Custom in Question. In Abusharaf RM (ed) Female Circumcision: Multicultural perspectives; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Almroth L, Elmusharaf S, El Hadi N. Primary infertility after genital mutilation in girlhood in Sudan: A Case Control Study. Lancet. 2005;366:385–391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J. Biological factors in human sexuality. J Sex Res. 2002;39:15–21. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson R. Human sex-response cycles. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:33–43. doi: 10.1080/00926230152035831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman L, Berman J, Miles M. Genital self-image as a component of sexual health: relationship between genital self-image, female sexual function, and quality of life measures. Sex Marital Ther. 2003;(Suppl 1):11–21. doi: 10.1080/713847124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania I, Abdulcadir O, Puppo V. Pleasure and orgasm in women with female genital mutilation/cutting. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1678. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dare FO, Oboro VO, Fadiora Female genital mutilation: An analysis of 522 cases in South-Western Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:281–283. doi: 10.1080/01443610410001660850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirie MA, Lindmark G. The risk of medical complications after female circumcision. East Afric Med J. 1992;69:479–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein G. From body to brain: Considering the neurobiological effects of female genital cutting. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51:84–97. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2008.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defrawi M, Lotfy G, Dandash K. Female genital mutilation and its psychosexual impact. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:465–473. doi: 10.1080/713846810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnashar A, Dien Ibrahim M, Desoky M. Female sexual dysfunction in Lower Egypt. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;114:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esho T, Enzlin P, Van Wolputte S. Female genital cutting and sexual functioning: In search of an alternate theoretical model. Afr Identities. 2010;8:221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Esho T, Enzlin P, Van Wolputte S. Van Wolputte S. (ed.) Borderlands and frontiers in Africa. Berlin: LIT Verlag; 2011. Between ritual and mutilation: Female Genital Cutting and the making of femininine identity among the Maasai. [Google Scholar]

- Esho T, Enzlin P, Van Wolputte S. The socio-cultural-symbolic nexus in the perpetuation of Female Genital Cutting. Afr Focus. 2011;24:53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fourcroy JL. Customs, culture, and tradition-what role do they play in a woman’s sexuality? J Sex Med. 2006;3:954–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum E. The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jaldesa GW, Askew I, Njue C. Population Council/FRONTIERS/USAID; 2005. Female genital cutting among the Somali of Kenya and management of its complications. [Google Scholar]

- Jaldesa GW, Qureshi ZP, Kigondu CS. Psychosexual problems associated with Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) J Obstet Gynaecol Eastern Central Afr (JOGECA) 2010;22:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsdotter S, Essen B. Sexual health among Somali women in Sweden: Living with conflicting culturally determined sexual ideologies. INTACT conference, Advancing knowledge on psycho-sexual effects of FGC: Assessing the evidence. Alexandria, Egypt, 10-12 October. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HS. Disorders of sexual desire and other new concepts and techniques in sex therapy. N. Y: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Karim M. Female genital mutilation; historical, social, religious, sexual and legal aspect. Cairo: National Population Council; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Kenya Demographic Health Survey fact sheet Kenya. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Magnitude of FGM in Kenya. National Focal Point. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen O. The Falling Dawadawa Tree: Female Circumcision in Developing Ghana. Ghana: Smyrna Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Laan E, Both S. What makes women experience desire? Fem Psychol. 2008;18:505. [Google Scholar]

- Levin RJ. The physiology of sexual arousal in the human female: A recreational and procreational synthesis. Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31:405–411. doi: 10.1023/a:1019836007416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, Chase C, Hammond T. Szuchman LT and Muscarela FJ (eds) Psychological Perspectives on Human Sexuality, Section lV, Issues of Cultural Concern. New York: Wiley & Sons Inc; 2000. Genital surgery on children below the age of consent; pp. 440–479. [Google Scholar]

- Klein H. The sexual experience and marital adjustment of genitally circumcised and infibulated females in the Sudan. J Sex Res. 1989;26:375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Mah K, Binik NY. Are orgasms in the mind or the body? Psychosocial versus Physiological correlates of orgasmic pleasure and satisfaction. J Sex Mar Ther. 2005;31:187–200. doi: 10.1080/00926230590513401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmström MF. Just like couscous: Gender, Agency and the politics of female circumcision in Cairo. Doctoral dissertation, University of Gothenburg, School of Global Studies and Social Anthropology. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Masters W, Johnson V. Human Sexual Response. N.Y: Little Brown and Company; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Meston C, Levin R, Sipski M. Paris: Health Publications; 2004. Women’s orgasm; 850 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers DT. Feminism and women’s autonomy: The challenge of female genital cutting. Metaphilosophy. 2000;22:469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Njambi NW. Irua ria atumia and anti-colonial struggles among the Gı˜ku˜yu˜ of Kenya: A counter narrative on “female genital mutilation. Crit Sociolog. 2007;33:689–708. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeyer CM. The consequences of female circumcision for health and sexuality: An update on the evidence. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7:443–461. doi: 10.1080/14789940500181495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonofua FE, Larsen U, Oronsaye The association between female genital cutting and correlates of sexual and gynaecological morbidity in Edo state, Nigeria. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109:1089–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Toubia N. Female genital mutilation: A guide to laws and policies worldwide. London: ZED Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan B, Hernlund Y. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2001. Female “circumcision” in Africa: Dimensions of the practice and debates; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder RA. What about “female genital mutilation”? And why understanding culture matters in the first place. Daedalus. 2000;129:209. [Google Scholar]

- Thabet AS, Thabet SM. Defective sexuality and female circumcision: The cause and the possible management. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2003;29:12–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2003.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . Changing a harmful social convention: Female genital mutilation/cutting. Innocenti Digest. UNICEF; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Whipple B, Komisaruk , B Brain (PET) responses to vaginal-cervical self-stimulation in women with complete spinal cord injury: A preliminary study. J Sex Mar Ther. 2002;29:79–86. doi: 10.1080/009262302317251043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Female genital mutilation. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/index.html 2010;(Fact sheet No. 241.) [Google Scholar]