Abstract

An 81-year-old woman treated with simvastatin for several years followed by atorvastatin for about 1 year presented with fatigue, weakness and unsteady gait. The finding of elevated creatine kinase (CK) and symmetric muscle weakness around shoulders and hips led to suspicion of a toxic statin-associated myopathy. Atorvastatin was withdrawn, but her weakness persisted. Owing to persisting weakness, an autoimmune myopathy (myositis) was suspected, but initially disregarded since a muscle biopsy showed necrotic muscle fibres without inflammatory cell infiltrates and myositis-specific autoantibodies were absent. After 18 months with slowly progressive weakness and increasing CK values, awareness of new knowledge about autoimmunity as a cause of necrotic myopathy, led to a successful treatment trial with intravenous immunoglobulines, followed by steroids and metothrexate. Antibodies to the target enzyme of statins (HMGCR (3-hydroksy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase)) were detected in her serum, and she was diagnosed with autoimmune necrotic myositis probably triggered by atorvastatin.

Background

Muscular side effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-coenzyme A) reductase inhibitors (statins) are diverse, ranging from common mild myalgia to local or generalised weakness and rare life-threatening rhabdomyolysis.1 Most side effects are toxic and self-limiting with recovery taking from one week up to several months after withdrawal of the statin.2 Statins may also trigger an autoimmune myopathy (myositis) that is treatable and therefore important to distinguish from the more common toxic myopathy.3 The distinction between autoimmune and toxic myopathy can be difficult since both may present with subacute or chronic proximal weakness of variable severity, and muscle biopsy may in both conditions show muscle fibre necrosis without inflammatory cell infiltrates. The present case illustrates these diagnostic pitfalls, and points to a recently discovered autoantibody that is useful in the diagnostic differentiation.

Case presentation

An 81-year-old woman with hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia had been treated with simvastatin 80 mg a day for several years, followed by atorvastatin 80 mg a day for about 1 year when she in 2008 developed symptoms of fatigue and general weakness. Her general practitioner (GP) found elevated levels of alanine transaminase (ALT) (132 U/L; normal <45 U/L) and aspartate transaminase (AST) (96 U/L; normal <35 U/L). The atorvastatin dose was therefore reduced to 40 mg. Her weakness continued to progress, and in March 2010 she was unable to walk and rise from a chair without support. MRI of the brain was normal. She changed to a new GP who measured her serum creatine kinase (CK) for the first time. It was markedly elevated to 11 235 U/L (normal <210 U/L). Atorvastatin was stopped, and she was admitted to the medical ward at Sørlandet Hospital in Kristiansand due to suspicion of rhabdomyolysis. On examination, she was weak and could not walk without support. Her renal function was normal, and the CK level had fallen to 5822 U/L a week after withdrawal of atorvastatin. Electromyography (EMG) showed a myopathic pattern with short, polyphasic motor-unit potentials, and profuse pathological spontaneous activity consisting of fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves. She was considered to have a toxic statin-associated myopathy and was discharged from hospital.

The patient's weakness and difficulties in walking persisted, and 5 weeks after withdrawal of atorvastatin she was admitted to the neurology ward. Neurological examination showed symmetrically reduced muscle strength for hip movements (MRC (Medical Research Council Scale) 2–3) and for shoulder movements (MRC 3–4). Sensory findings and reflexes were normal. CK was 7679 U/L. A muscle biopsy of quadriceps femoris was performed and sent to Oslo University Hospital for analysis. Owing to clinical suspicion of polymyositis she started with prednisolone 80 mg a day. At discharge 2 weeks later her muscle strength had improved slightly, and CK had fallen to 3709 U/L.

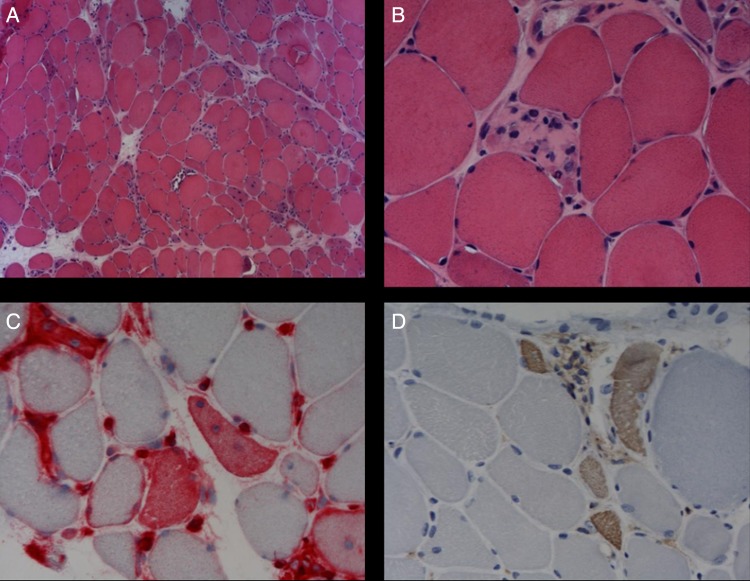

After 5 weeks on prednisolone she reported side effects, and no further improvement. The result of the muscle biopsy was now available. It showed necrotic and regenerating muscle fibres without inflammatory infiltrates (figure 1). Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I expression was detected in regenerating muscle fibres. Immunohistochemical stainings for muscle dystrophies were normal (dystrophin 1, 2 and 3, α-dystroglycan, α-sarcoglycan, β-sarcoglycan, γ-sarcoglycan and δ-sarcoglycan, caveolin, merosin, dysferlin and emerin). No tubuloreticular structures were found in the endothelial cells by electron microscopy. The following kinds of necrotic myopathy were suggested: toxic statin-associated myopathy, paraneoplastic myopathy and necrotic immune-mediated myopathy with SRP (signal recognition particle) antibodies. Blood tests and CT of the chest and abdomen revealed no malignancy. Myositis-specific autoantibodies including anti-SRP antibodies were not detected. A toxic statin myopathy with slow recovery was therefore considered to be the most likely diagnosis. Prednisolone was tapered and withdrawn in July 2010, and she was transferred to follow-up by her GP.

Figure 1.

Muscle biopsy specimen obtained from our patient at first admission. (A and B) Staining with H&E showed myofibre necrosis and regenerating fibres. (C) Expression of MHC class I antigens was detected in regenerating muscle fibres. (D) The presence of regenerating muscle fibres were confirmed with immunostaining for neonatal myosin. (Original magnification ×100 in (A) and ×400 in (B), (C) and (D)).

During the next year the patient's muscle strength improved somewhat and stabilised, so that she was able to walk unassisted and do household work. Her CK values did however increase slowly from 552 U/L in October 2010 to 2545 U/L in October 2011. From October 2011 she became gradually weaker, and was unable to walk unassisted. Examination at the neurological outpatient clinic in February 2012 showed weakness for hip flexion (MRC 3) and shoulder abduction (MRC 4). CK was 5299 U/L. Muscle biopsy showed a similar, but less extensive pattern than in 2010; there were a few necrotic muscle fibres without inflammation. Owing to the fluctuating clinical course, she was suspected to have an autoimmune myopathy. In May 2012 she was treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) (2 g/kg over 5 days), and her muscle strength improved markedly during the treatment. She started with prednisolone 40 mg a day with slow tapering. After reduction of the prednisolone dose to 5 mg a day in March 2013, her difficulties in walking and CK values increased slowly. Prednisolone was temporarily increased to 20 mg, and methotrexate 7.5 mg once a week was added as a steroid-sparing agent in September 2013.

The patient's serum tested positive for antibodies to the pharmacological target of statins (HMGCR (3-hydroksy-3-methylglutaryl-coenxyme A reductase)) by Dr Andrew Mammen (Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Labs, Baltimore, Maryland, USA) in September 2013. She was diagnosed with necrotising autoimmune myopathy with HMGCR antibodies.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient has remained on a low prednisolone dose for 14 months with addition of methotrexate for 3 months at last follow-up, and she has remained clinically stable with minimal difficulties in walking and hip weakness.

Discussion

We describe a woman treated with simvastatin followed by atorvastatin who presented with fatigue and weakness for several years before CK was measured and it led to a diagnosis of myopathy based on proximal weakness, elevated CK and a myopathic EMG pattern. A toxic statin-associtaed myopathy was initially suspected, but was reconsidered since weakness persisted after withdrawal of atorvastatin. Other causes of myopathy could be muscle dystrophy or autoimmunity.4 Muscle dystrophies are diagnosed by immunostaining of muscle biopsy or by genetic testing. Our patient had negative immunostaining for various dystrophies. Autoimmune myopathies can be identified by finding inflammatory cell infiltrates in muscle biopsy, and myositis-specific autoantibodies in serum. The muscle biopsy in our patient showed a necrotising myopathy without inflammatory cell infiltration, and muscle antibodies including anti-SRP and antisynthetase antibodies were negative. Autoimmune myopathy was therefore initially considered as unlikely.

Autoimmunity is increasingly reported as the mechanism in myopathies where muscle biopsy only reveals necrotic muscle fibres with absent or minimal inflammatory cell infiltration. Necrotising autoimmune myopathy (NAM) now constitutes a separate category under the family of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies that otherwise5 includes dermatomyositis (DM), polymyositis (PM) and inclusion body myositis (IBM).6 About a third of NAM cases have classical myositis-antibodies; anti-SRP or anti-synthetase antibodies.5 Some antibody negative cases may be paraneoplastic. The prevalence of statin exposure is high (about 80%) in patients with NAM as compared to about 20% in those with DM or PM.2 Autoimmune myopathy has been reported after exposure to atorvastatin, simvastatin and paravastatin.2

A recently discovered autoantibody that binds to the pharmacological target of statins (HMGCR) seems to be quite specific for statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. In one report anti-HMGCR antibodies were found in 62% of NAM cases without classical myositis-antibodies5 and 92% of anti-HMGCR positive patients over 50 years were statin users.2 Anti-HMGCR antibodies have been found in a few patients with NAM without statin-exposure2 7 including a patient with NAM and genetically proven limb-girdle muscular dystrophy,7 but they are not found in statin-associated toxic myopathies2 and not in the vast majority of patients with and without statin exposure.2

The necrotising autoimmune myopathy in our patient was considered to be triggered by atorvastatin due to the finding of anti-HMGCR antibodies, and the lack of other known causes of necrotisinig myopathy (anti-CRP antibodies and paraneoplasia). Why she tolerated simvastastin for several years and atorvastatin for about 1 year prior to developing myopathy is unexplained, but may be related to an additional unknown environmental trigger. The time interval in our patient agrees with previous reports of autoimmune statin-associated myopathy showing that weakness follows initiation of statins by an average of 31–36 months, with a range from 0 month up to 10 years.2 3

Patients with anti-HMGCR NAM need immunosuppressive treatment. Prednisone 1 mg/kg/day is effective, but due to frequent relapses when tapering, it is probably beneficial, as in anti-SRP myositis, to add a steroid-sparing agent (for example, methotrexate (0.3 mg/kg/week)) and keep the patient on it for at least 2 years. In cases with severe weakness IVIG may be useful, and rituximab may be effective in resistant forms.4

Learning points.

Myopathy caused by statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A(HMG-coenzyme A) reductase inhibitors) may present with difficulties in walking without myalgia.

Statins may trigger a chronic autoimmune and treatable myopathy.

A myopathy can be autoimmune despite the absence of inflammatory infiltrates on muscle biopsy and absence of myositis antibodies in the serum.

Antibodies against HMG-coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR antibodies) may be a clue to the diagnosis of autoimmune myopathy.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Joy TR, Hegele RA. Narrative review: statin-related myopathy. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:858–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohassel P, Mammen AL. Statin-associated autoimmune myopathy and anti-HMGCR autoantibodies. Muscle Nerve 2013;48:477–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grable-Esposito P, Katzberg HD, Greenberg SA, et al. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:185–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allenbach Y, Benveniste O. Acquired necrotizing myopathies. Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26:554–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christopher-Stine L, Casciola-Rosen LA, Hong G, et al. A novel autoantibody recognizing 200-kd and 100-kd proteins is associated with an immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2757–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amato AA, Barohn RJ. Evaluation and treatment of inflammatory myopathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:1060–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claeys KG, Gorodinskaya O, Handt S, et al. Diagnostic challenge and therapeutic dilemma in necrotizing myopathy. Neurology 2013;81:932–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]