Abstract

Bezoars are an unusual cause of acute intestinal obstruction in children. Most cases are trichobezoars in adolescent girls who swallow their hair. Lactobezoars are another unusual but occasionally reported cause of intestinal obstruction in neonates. Phytobezoars and food bolus bezoars are the least common types of intestinal obstruction that have been reported in children. Of the few paediatric cases that have been described, the majority involve persimmons. Moreover, all of these cases involve the ingestion of raw fibres or fruit that have not been cooked. We report a case of a girl who presented with acute ileal obstruction because of lentil soup bezoar. Given the wide use of this otherwise nutritional foodstuff, we highlight the danger from its inappropriate preparation to the health of children. This is the first reported case of intestinal obstruction caused by lentils in children and we hope to raise concern among paediatricians regarding this matter.

Background

This is the first reported case of intestinal obstruction caused by lentils in children and we hope to raise concern among paediatricians regarding this matter. Given the wide use of lentils all over the world, we highlight the dangers from its inappropriate preparation.

Case presentation

An 11-year-old girl presented to the emergency department of our hospital with acute abdominal pain and vomiting. On examination, she had a generalised tenderness in her abdomen. Vital signs were normal. She had a transverse scar on the right side of her abdomen from a previous appendectomy 6 months ago. No inguinal hernia identified bilaterally. There was no history of other similar episodes. She had normal bowel movement the previous day and admitted to have eaten lentil soup 2 days earlier. No history of consumption of other raw fibres or fruits.

Investigations

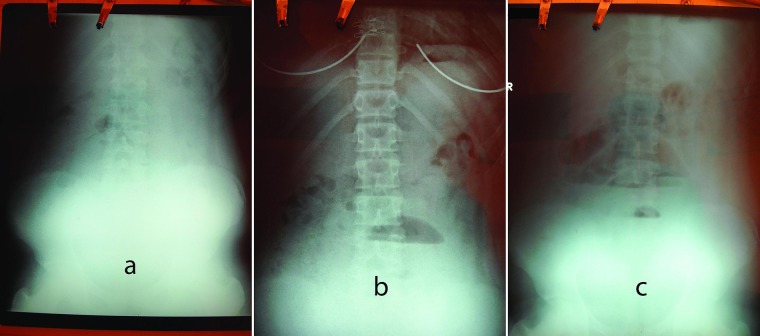

Blood test results were normal, and an abdominal X-ray did not show any specific findings (figure 1A). An abdominal ultrasound showed a gross dilation of intestinal loops. The patient was admitted to our department and was started on conservative management with a possible diagnosis of postoperative ileus, complication from her previous appendectomy. A nasogastric tube was inserted, and 100 mL of bile-containing gastric fluids were evacuated. Intravenous fluids and antibiotics were started. On a second X-ray 6 h later (figure 1B), we noticed an air-fluid level that was suggestive of small bowel pathology in the area previously operated on in the abdomen. On the other hand, her clinical condition slightly improved mainly as a result of good hydration and pain management. We decided to wait few more hours and re-evaluate our conservative approach. Six hours later her clinical condition again started to deteriorate, pain on palpation became worse, her temperature and heart rate started rising and a new abdominal X-ray showed explicit air-fluid levels dispersed in the centre of the patient's abdomen (figure 1C).

Figure 1.

X-ray findings, (A) at presentation, (B) 6 h and (C) 12 h after admission.

Differential diagnosis

Our patient had previously undergone surgery for acute appendicitis. Thus the most probable preoperative diagnosis was acute intestinal obstruction due to adhesion formation. Our initial approach was conservative management, which is widely accepted in children with postoperative small bowel obstruction, provided that there are no clinical signs of bowel strangulation.1 There are of course other possible surgical causes that could explain her symptoms such as an internal hernia, phytobezoar formation, volvulus but at the time of presentation seemed less possible. She reported consumption of lentil soup the previous night but not any other raw fibres or fruits, like persimmons that are responsible for the majority of phytobezoar cases in children.2 Volvulus presents in a more dramatic way and having had an uneventful appendectomy with normal localisation of the caecum, that also seemed improbable. Moreover, her X-ray findings were not suggestive of such a case.3 Finally an internal hernia is either congenital which is quite uncommon in a child and one would expect to have already given symptoms earlier in life or present postoperatively after a major operation involving bowel but seems unlikely after a simple appendectomy.4

Treatment

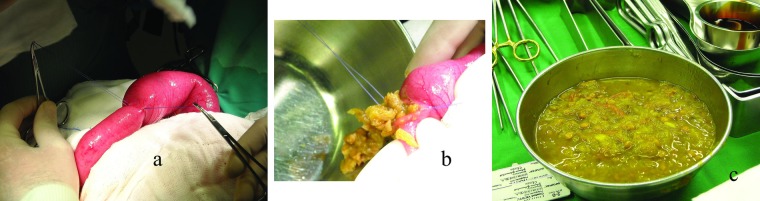

As the patient's clinical condition was not improving and her radiological evaluation showed clear signs of deterioration, we decided to proceed to an exploratory laparotomy. We decided to avoid a CT scan because we thought that this would expose the child to unnecessary radiation and it would not offer information that could change further management. Worse than that, it would delay further management. An exploratory laparotomy seemed unavoidable due to her clinical and radiological deterioration. On entering the abdomen we noticed significantly dilated small bowel loops. The appendiceal stump appeared to be normal and there were no significant adhesions inside her abdomen. We followed the dilated bowel loops until we reached a discrepancy in the diameter some 40 cm from the ileocecal valve, which signified the point of obstruction (figure 2A). There were no external signs of obstruction or kinking. Inside the bowel loops, we felt a soft mass that was impossible to move. We performed a Mikulicz enterotomy (figure 2B), and to our surprise, we found remnants of lentil soup that had formed a solid indigestible mass. We evacuated around 500 mL of lentil soup through our incision (figure 2C). After this evacuation we checked for a possible intraluminal cause for obstruction such as an incomplete membrane, but we did not find any abnormality. We closed our longitudinal enterotomy in a transverse way, and after reducing the bowel loops, we closed the abdomen.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative findings, (A) bowel loop discrepancy at the site of obstruction, (B) immediately after incising the bowel and (C) after removal of the whole material.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively the girl reported once more that she had eaten lentil soup cooked by her father 2 days earlier. She did not have anymedical history that could cause this inability to digest the soup. She was discharged in good health on the third postoperative day.

Discussion

Bezoars are an unusual cause of acute intestinal obstruction in children.5 6 Obstructing foodstuffs are those rich in fibre, including desiccated fruit and unripe fruit, which swell as they take up water within the intestinal lumen during their passage through it, or substances resistant to the digestive juices.7 Approximately 45 different obstructing agents have been reported by Ward-McQuaid.8 Of the few paediatric cases that have been described the majority involve persimmons.2

The lentil (Lens culinaris) is a type of pulse. It is a bushy annual plant of the legume family, grown for its lens-shaped seeds. World lentil production has risen steadily by 412% from 1961–1963 to 2004–2006.9 Lentils are used throughout South Asia, the Mediterranean region, the Middle East and also all over Europe, North and South America.10 Lentils are highly nutritious. They are an essential source of inexpensive protein in many parts of the world and also contain dietary fibre, folate, vitamin B1 and minerals and they are a good vegetable source of iron.11

We report the first ever reported case of a young girl who presented with acute ileal obstruction because of a lentil soup bezoar. She had previously undergone surgery for acute appendicitis. Thus the most probable preoperative diagnosis was acute intestinal obstruction due to adhesion formation. Our initial approach was conservative management, which is widely accepted in children with postoperative small bowel obstruction, provided that there are no clinical signs of bowel strangulation.1 As the patient's clinical condition did not improve and her radiological evaluation deteriorated, we decided to operate after 16 h of watchful waiting.

Intraoperatively the appendiceal stump appeared normal and there were no significant adhesions. Moreover, we did not identify any point of intestinal stenosis or other anatomic abnormality that could explain why this unusual bezoar was formed. Hermedical history was also absolutely normal, with no history of difficult digestion, and she never had taken any medication that could influence gastrointestinal function.

Lentils are known to have ‘antinutritional factors’, such as trypsin inhibitors and relatively high phytate content. As a result lentils should not be eaten raw and require a cooking time of 10–30 min, depending on the variety (shorter for small varieties with the husk removed, such as the common red lentil). In addition, the phytate concentration can be reduced by soaking the lentils in warm water overnight.10 12 Based on the above information, we believe that the most probable cause for her condition was inadequate preparation and an incorrect cooking method used for the lentil soup, which was also probably not well-masticated and was swallowed rapidly. These findings highlight that such a bezoar could form in any normal child without predisposing factors.

Learning point.

Even though the nutritional value of lentils cannot be denied, it is important to stress that they should not be eaten raw and they should be thoroughly cooked. The cooking time should be long enough that they become soft and easily digestible.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, also in revising it critically and gave final approval of the version published.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Feigin E, Kravarusic D, Goldrat I, et al. The 16 golden hours for conservative treatment in children with postoperative small bowel obstruction. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:966–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi SO, Kang JS. Gastrointestinal phytobezoars in childhood. J Pediatr Surg 1988;23:338–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millar AJ, Rode H, Cywes S. Malrotation and volvulus in infancy and childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg 2003;12:229–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang V, Daneman A, Navarro OM, et al. Internal hernias in children: spectrum of clinical and imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol 2011;41:1559–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yulevich A, Finaly R, Mares AJ. Candy bezoar. An unusual cause of food bolus bezoar. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1993;17:108–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burstein I, Steinberg R, Zer M. Small bowel obstruction and covered perforation in childhood caused by bizarre bezoars and foreign bodies. Isr Med Assoc J 2000;2:129–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandal AK, Hayes LM. Intestinal obstruction due to ingested food. J Natl Med Assoc 1964;56:153–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward-McQuaid N. Intestinal obstruction due to food. BMJ 1950;1:1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erskine W. Global production, supply and demand. In: Erskine W, Muehlbauer FJ, Sarker A, Balram S, eds. The lentil botany, production and uses. CAB International, 2009:4–12 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raghuvanshi RS, Singh DP. Food preparation and use. In: Erskine W, Muehlbauer FJ, Sarker A, Balram S, eds. The lentil botany, production and uses. CAB International, 2009:408–24 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erskine W, Muehlbauer FJ, Sarker A, et al. Introduction. In: Erskine W, Muehlbauer FJ, Sarker A, Balram S, eds. The lentil botany, production and uses.. CAB International, 2009:1–3 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vidal-Valverde C, Frias J, Estrella I, et al. Effect of processing on some antinutritional factors of lentils. J Agric Food Chem 1994;42:2291–5 [Google Scholar]