Abstract

We conducted a systematic review in June 2012 (updated September 2013) to examine the prevalence and factors shaping sexual or physical violence against sex workers globally.

We identified 1536 (update = 340) unique articles. We included 28 studies, with 14 more contributing to violence prevalence estimates. Lifetime prevalence of any or combined workplace violence ranged from 45% to 75% and over the past year, 32% to 55%. Growing research links contextual factors with violence against sex workers, alongside known interpersonal and individual risks.

This high burden of violence against sex workers globally and large gaps in epidemiological data support the need for research and structural interventions to better document and respond to the contextual factors shaping this violence. Measurement and methodological innovation, in partnership with sex work communities, are critical.

Frequent reports of incidents of widespread violence against sex workers continue to emerge globally,1–3 including media reports of abuse, human rights violations, and murder.4–7 Despite increasing recognition of violence in the general population as a public health and human rights priority by policymakers, researchers, and international bodies,8–10 violence against sex workers that occurs within and outside the context of sex work is frequently overlooked in international agendas to prevent violence. Although increasing research has explored the prevalence, determinants, and correlates of violence against women,8,11–14 comparable research specifically among sex workers is lacking. There remains limited review of the magnitude, severity, or type of violence experienced by sex workers globally. This paucity of data on prevalence and incidence of violence against sex workers has been highlighted in a review on the magnitude and scope of violence globally.15

Negative health effects of intimate partner violence in the general population include poor health overall, physical and sexual injury, and mental health problems including depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder.16–21 Intimate partner violence faced by women in the general population has also been linked to unwanted pregnancy, abortion, and increased risk for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), through different direct and indirect mechanisms.22–26 Victims of violence in early childhood are also more likely to have increased risk for HIV and other STIs.27 However, the role of violence, both workplace violence and violence by intimate or other nonpaying partners, in influencing negative health outcomes among sex workers, who are highly stigmatized and often criminalized, has received comparably less attention.

The legal status of sex work can be a critical factor in shaping patterns of violence against sex workers.1,28 In many settings, the criminalized or quasicriminalized nature of sex work means that violence that occurs in the context of sex work (i.e., as a workplace harm and abuse) is not monitored by any formal bodies, with few to no legal protections afforded to sex workers by police and judicial systems.1,28 Violence against sex workers is often not registered as an offense by the police and in some cases is perpetrated by police.29,30 Physical and sexual violence, and verbal abuse or threats of abuse from police, can prevent sex workers from reporting violence to the police or accessing other public agencies (e.g., health or social services), exacerbating their trauma and health risks.1,29,30 These risks include the risk for HIV and other STIs, and in some settings, threats of arrest for possession of condoms as evidence of engaging in sex work can deter sex workers from carrying condoms.30–32 This can create a climate of tolerance of violence and thereby perpetuate violence against sex workers.

We conducted a systematic review to examine the documented magnitude of violence against sex workers and to review the factors that shape risk for violence against sex workers. In our review we were guided by theoretical frameworks that implicate structural factors in shaping vulnerabilities experienced by vulnerable populations.33–35 Within the interrelated physical, social, economic, and policy environments, factors operate to create different levels of susceptibility and risk.33–35 The current review provides an evidence base pertaining to violence against sex workers from which to better inform the development of public health and social interventions to reduce violence and ameliorate its impacts on sex workers.

METHODS

To conduct this systematic review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, consistent with previous systematic reviews among marginalized populations.36

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

We undertook a comprehensive review of all major databases between June 22 and 23, 2012 (K. N. D. and A. N.), updated September 9–14, 2013 (E. A. and P. D.). Databases included the Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science), Ovid Medline (1948 to present with daily update), Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, All Evidence-Based Medicine Review, PAIS, EMBASE, BioMed Central, PubMed, Academic Search Complete, Social Work Abstracts, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and PsycINFO. Search terms included “violence” or “sexual violence” or “physical violence” or “victimization”; and “sex work” or “sex worker” or “sex workers” or “prostitute” or “prostitutes” or “prostitution.” Both authors (K. N. D. and A. N.) searched reference lists of published articles and reviews, and Google Scholar. Articles were limited to those published in English language, but there was no limit on the year in which the study could be published. Details on the search strategy (both the original and the updated searches) are included in Table A (available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

TABLE 1—

Summary of Included Studies and the Correlates of Violence for Systematic Review in June 2012 (Updated September 2013) to Examine the Prevalence and Factors Shaping Risk of Sexual or Physical Violence Against Sex Workers Globally

| Study | Covariate | Outcomes (Standardized Violence Outcome) | AOR (95% CI) | b (P) |

| Beattie et al.37 | Participant in follow-up vs baseline sample | SV, past year, by any or combined perpetrator | 0.70 (0.53, 0.93) | |

| Participant was exposed to the intervention for < 12 mo vs ≥ 12 mo | 0.80 (0.60, 1.00) | |||

| Bhattacharjee et al.38 | Membership in peer group or collective | PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 0.70 (0.53, 0.92) | |

| SV, past year, by any or combined perpetrator | 0.84 (0.62, 1.14) | |||

| Blanchard et al.39 | “Power within”—sense of individual self-esteem | Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrators | 0.96 (< .05) | |

| “Power with”—collective identity and solidarity | 1.13 (< .05) | |||

| “Power over resources”—access to social entitlements | 1.06 (< .05) | |||

| Blanchard et al.40 | Participant illiterate vs literate | SV, past year, workplace | 1.44 (1.03, 2.00) | |

| Participant nontraditional vs traditional or socially accepted (i.e., Devadasi) sex work | 0.41 (0.28, 0.61) | |||

| Work at home vs brothel, lodge, or public place | 0.44 (0.30, 0.63) | |||

| Carlson et al.41 | Participated in wellness intervention | PV, past 90 d, by NPP | 0.15 (0.07, 0.35) | |

| SV, past 90 d, by NPP | 0.05 (0.02, 0.14) | |||

| Participated in risk-reduction intervention | PV, past 90 d, by NPP | 0.11 (0.04, 0.34) | ||

| SV, past 90 d, by NPP | 0.06 (0.02, 0.19) | |||

| Participated in risk reduction and motivational interview intervention | PV, past 90 d, by NPP | 0.29 (0.13, 0.65) | ||

| SV, past 90 d, by NPP | 0.15 (0.07, 0.33) | |||

| Chersich et al.42 | Binge vs non–binge drinker | SV, past year, workplace | 1.85 (1.27, 2.71) | |

| Never married vs separated or divorced | 1.65 (1.10, 2.48) | |||

| Widow vs separated or divorced | 2.26 (1.17, 4.35) | |||

| No. of sexual partners (increase per 1 partner) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | |||

| Choi43 | Increased sexual health knowledge | Any or combined violence, ever, workplace | 0.19 (< .05) | |

| Increased economic pressure | 0.22 (< .001) | |||

| Vietnamese vs mainland Chinese | 0.80 (< .05) | |||

| Thai vs mainland Chinese | 1.05 (< .05) | |||

| Junior secondary vs primary or lower education | 0.72 (< .05) | |||

| Church et al.44,a | Work outdoors vs indoors | Any or combined violence, ever, workplace | 81% vs 48%b | (< .001) |

| Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, workplace | AOR > 6;50% vs 26%b | (< .001) | ||

| Decker et al.45 | Participant was trafficked | SV at sex work initiation | 2.29 (1.11, 4.72) | |

| Any or combined violence, past wk, workplace | 1.38 (1.13, 1.67) | |||

| Deering et al.46 | Arrested in the past year | Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, workplace | 1.84 (1.02, 3.31) | |

| El-Bassel et al.47 | Intravenous heroin use | Any or combined violence, past year, workplace | 9.81 (2.67, 36.00) | |

| Participant traded sexual intercourse for money or drugs at a crack house | 8.70 (2.11, 35.78) | |||

| Erausquin et al.48 | Police had sexual intercourse with respondent so she could avoid trouble | Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, workplace | 3.06 (1.89, 4.93) | |

| Police accepted bribe or gift from respondent to avoid trouble | 3.16 (2.00, 4.98) | |||

| Police took condoms away | 5.62 (3.22, 9.82) | |||

| Police raided workplace | 4.64 (3.16, 6.81) | |||

| Police arrested respondent | 7.14 (4.45, 11.44) | |||

| George et al.49 | Sex trafficking | PV, past 6 mo, workplace | 0.90 (0.67, 1.22) | |

| SV, past 6 mo, workplace | 2.09 (1.42, 3.06) | |||

| Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, workplace | 1.93 (1.24, 3.01) | |||

| George et al.50 | Did contract work | PV, past 6 mo, workplace | 3.16 (2.01, 4.95) | |

| SV, past 6 mo, workplace | 2.14 (1.16, 3.95) | |||

| Go et al.51 | Had unprotected sexual activity with a nonspousal partner and > 20 d of alcohol consumption in the past 30 d vs no unprotected sexual activity, 0–9 d of alcohol consumption | SV, past 3 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 2.66 (1.13, 6.29) | |

| ≥ 2 sex partners with strong tendency to drink alcohol before sexual activity vs none | 1.87 (1.38, 2.54) | |||

| Spoke with 1–5 people about family violence past 3 mo vs none | 0.61 (0.44, 0.86) | |||

| Spoke with ≥ 6 people spoke with about family violence last 3 mo vs none | 0.41 (0.22, 0.75) | |||

| Gupta et al.52 | Sex trafficking as a mode of entry into sex work | Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 1.72 (1.20, 2.46) | |

| PV or SV, past 6 mo | 1.66 (1.16, 2.38) | |||

| Hong et al.53 | Depression | Any or combined violence, ever, workplace | 1.76 (1.34, 2.30) | |

| Loneliness | 1.61 (1.22, 2.11) | |||

| Alcohol intoxication | 1.87 (1.31, 2.65) | |||

| Drug abuse | 1.99 (1.36, 2.91) | |||

| Suicidal behavior | 1.93 (1.23, 3.03) | |||

| Depression | Any or combined violence, ever, by NPP | 2.00 (1.45, 2.76) | ||

| Loneliness | 2.08 (1.51, 2.87) | |||

| Alcohol intoxication | 2.27 (1.52, 3.39) | |||

| Drug abuse | 1.26 (0.80, 1.99) | |||

| Suicidal behavior | 2.91 (1.54, 5.49) | |||

| Odinokova et al.54 | Street sex work | SV, past year, workplace | 8.08 (4.58, 14.07) | |

| Client rape during sex work | 2.09 (1.46, 2.99) | |||

| Current intravenous drug use | 1.94 (1.15, 3.26) | |||

| Past year binge drinking | 1.46 (1.03, 2.07) | |||

| Platt et al.55 | Ever been arrested or imprisoned | PV, past year, workplace | 2.60 (2.24, 5.71) | |

| Currently has a nonpaying sex partner | 2.00 (1.03, 3.96) | |||

| Increased alcohol use (scored higher on AUDIT) | 0.40 (0.21, 0.82) | |||

| Reed et al.56 | High mobility (having worked in ≥ 3 villages or towns in the past year) | SV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 5.20 (3.00, 8.90) | |

| PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 1.70 (1.10, 2.70) | |||

| Reed et al.57 | High residential instability (≥ 5 evictions past 5 y) | SV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 3.50 (2.10, 5.80) | |

| PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 3.10 (2.10, 4.30) | |||

| Reed et al.58 | Currently in debt | PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 2.40 (1.50, 3.90) | |

| Saggurti et al.59 | ≥ 4 moves in past 2 y (vs 2 or 3) | Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator | 1.40 (1.20, 1.60) | |

| Stayed for ≤ 1 mo at previous 2 places | 1.40 (1.20, 1.60) | |||

| Visited jatra (special religious festivals) place | 2.10 (1.80, 2.40) | |||

| Visited a place frequented by seasonal male migrant workers | 1.30 (1.00, 1.60) | |||

| Shannon et al.60 | Pressured into sexual intercourse without a condom | PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator excluding clients | 2.23 (1.40, 3.61) | |

| SV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator excluding clients | 1.82 (1.01, 3.25) | |||

| Any or combined violence (physical and sexual), past 6 mo, clients | 2.23 (1.40, 3.61) | |||

| Homeless | PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator excluding clients | 2.14 (1.34, 3.43) | ||

| SV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator excluding clients | 1.73 (1.09, 3.12) | |||

| Unable to access drug treatment | PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator excluding clients | 1.96 (1.03, 3.43) | ||

| Any or combined violence (physical and sexual), past 6 mo, clients | 2.13 (1.26, 3.62) | |||

| Police confiscated drug use material | PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator excluding clients | 1.50 (1.02, 2.41) | ||

| Previous assault by police | PV, past 6 mo, by any or combined perpetrator excluding clients | 2.61 (1.32, 5.16) | ||

| Any or combined violence (physical and sexual), past 6 mo, clients | 3.45 (1.98, 6.02) | |||

| Serviced clients in cars or public spaces | Any or combined violence (physical and sexual), past 6 mo, clients | 1.50 (1.08, 2.57) | ||

| Moved away from working in main streets because of policing | Any or combined violence (physical and sexual), past 6 mo, clients | 2.13 (1.26, 3.62) | ||

| Shaw et al.61 | Anal sexual intercourse with ≥ 5 casual sexual partners in the past wk | SV, past year, by any or combined perpetrator | 4.08 (1.17, 14.26) | |

| Silverman et al.62 | Forced or coerced into sex work | SV, first mo of sex work, by any or combined perpetrator | 3.10 (1.60, 6.10) | |

| Ulibarri et al.63 | Participant experienced abuse as a child (emotional, physical, sexual) | Any or combined violence, past 6 mo, by NPP | 2.29 (1.24, 4.22) | |

| Spouse or steady partner had sexual intercourse with another partner | 2.45 (1.34, 4.82) | |||

| Increased mean relationship power scale score (sexual relationship power | 0.35 (0.18, 0.66) | |||

| Zhang et al.64,b | Risky drinking | SV (sexual advantages taken), ever, workplace | 2.19 (1.49, 3.23) | |

| Heavy drinking | 2.49 (1.47, 4.21) | |||

| Hazardous drinking | 5.31 (2.56, 11.01) | |||

| Risky drinking | SV (demand for extra sexual service), ever, workplace | 1.23 (0.84, 1.80) | ||

| Heavy drinking | 2.11 (1.28, 3.46) | |||

| Hazardous drinking | 3.54 (1.93, 6.50) | |||

| Risky drinking | SV (being raped or sexually assaulted), ever, workplace | 0.89 (0.39, 2.02) | ||

| Heavy drinking | 2.58 (1.10, 6.05) | |||

| Hazardous drinking | 3.57 (1.46, 8.72) | |||

| Risky drinking | SV (clothes stripped off), ever, workplace | 1.51 (0.52, 4.40) | ||

| Heavy drinking | 3.44 (1.10, 10.76) | |||

| Hazardous drinking | 3.79 (1.15, 12.52) | |||

| Risky drinking | SV (coerced into sex without force), ever, workplace | 1.58 (0.88, 2.86) | ||

| Heavy drinking | 2.07 (1.00, 4.29) | |||

| Hazardous drinking | 2.27 (1.00, 5.18) | |||

| Risky drinking | SV (coerced into sexual activity with violence), ever, workplace | 0.71 (0.21, 2.47) | ||

| Heavy drinking | 1.78 (0.49, 6.46) | |||

| Hazardous drinking | 1.29 (0.27, 6.14) | |||

| Risky drinking | SV (genitals purposely injured), ever, workplace | 2.47 (0.85, 7.16) | ||

| Heavy drinking | 4.71 (1.31, 16.99) | |||

| Hazardous drinking | 1.38 (0.15, 12.82) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CI = confidence interval; NPP = intimate or other nonpaying partner; OR = odds ratio; PV = physical violence; SV = sexual violence.

Odds ratios were not presented.

Risky drinking = AUDIT score 8–15; heavy drinking = AUDIT score 16–19; hazardous drinking = AUDIT score 20–40.

We included articles that examined the prevalence and correlates of violence against sex workers (i.e., violence as an outcome) by using quantitative, multivariable methods, published in peer-reviewed journals. We also collected additional quantitative studies captured in the search process that examined the correlates of violence by using either bivariate methods to test statistical significance or no test of statistical significance. The latter studies were not included in the main review results, but we did collect violence prevalence estimates from these studies to combine with violence prevalence estimates from studies identified in the main review, to provide a more comprehensive and representative set of violence prevalence estimates. We excluded gray literature (e.g., government reports), as well as case reports and case series, reviews, editorials, and opinion pieces.

We included studies on individuals who exchanged sexual intercourse for money or other goods as a commercial activity (i.e., sex work); however, we excluded studies that focused exclusively on transactional sex (i.e., which occurs when something, primarily nonmonetary goods, shelter, gifts, services, but could include money, is informally provided in exchange for sexual services, but not within a formal or professional commercial transaction). Sex workers could be self-identified as female, male, or transgender. We included studies that included details on workplace violence (e.g., perpetrated by clients, police, managers, pimps, madams, or other third parties) and intimate and other nonpaying partners (i.e., casual, noncommercial partners). Of interest was physical or sexual violence, or violence measures that included at least 1 of physical or sexual (any or combined violence); although we did not specifically search for emotional or verbal violence, this type of violence was sometimes nested within scales that measure violence.

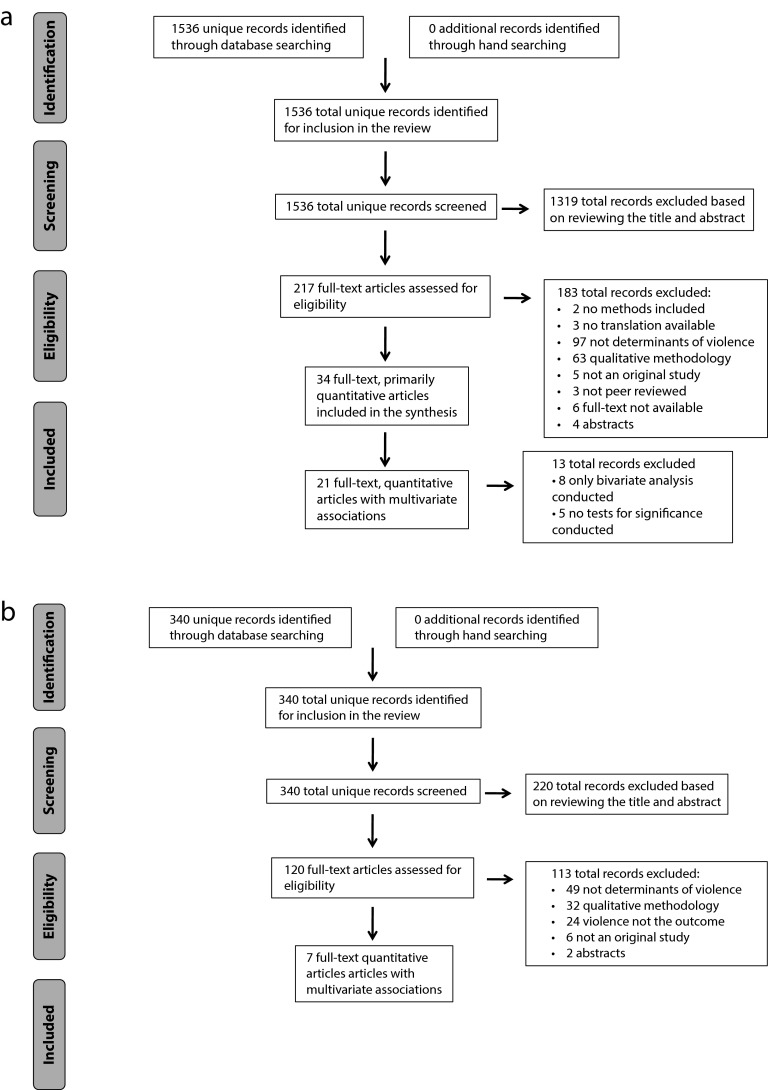

We read all abstracts to determine their relevance. We read all of the relevant articles in their entirety. Reviewers compared inclusions, and discussed them; in the case of discrepancies, we discussed with another author (K. S.) to reach a consensus. Where necessary, we contacted authors of the articles for additional data. The exclusion process and details on excluded articles are provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1—

Screening flowcharts of how studies were chosen to examine the prevalence and factors shaping risk of sexual or physical violence against sex workers globally, by (a) the original set of studies in June 2012 and (b) the updated set of studies in September 2013.

Data Extraction and Analysis

We extracted relevant information from each study (study design, participant characteristics, sex work environment [i.e., indoor, outdoor], violence outcome) and entered by one author and checked by others. We described the violence outcomes used by researchers to capture violence in each study and then summarized them into a standardized violence outcome for comparison purposes, by the type of violence (i.e., any or combined, physical, sexual), timescale (i.e., ever or lifetime, past year, past 6 months), and perpetrator (i.e., any or combined, workplace, intimate or nonpaying partners).

Table B (available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides the specific violence measure used in each specific study as well as the standardized outcome; Table 1 provides only the standardized outcome. The majority of “workplace” violence outcomes related to violence by clients.

RESULTS

The search process is described in Figure 1a (original search) and 1b (updated search) and Table A. Overall, 28 studies37–64 with quantitative multivariable studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the primary analysis on correlates of violence (Table 1), with 14 additional studies37,65–77 contributing violence prevalence estimates only (Table B).

Summary of Included Studies

The 41 peer-reviewed articles that met the inclusion criteria for assessing prevalence of violence (including the requirement that the study examine correlates of violence in bivariate or multivariable analysis) covered multiple geographic regions, with 27 from Asia (India, China, Thailand, Bangladesh, Mongolia), 6 from North America (Canada, United States, Mexico), 3 from Central and Western Europe, 2 from Central Africa (Kenya, Ethiopia), and 1 each from the Middle East, Latin America, Russia, and South Africa (Table B).

Overall, 27 of the studies included samples of sex workers from multiple sex work environments (e.g., homes, brothels, public places), and 12 included samples of sex workers from a single sex-work environment (6 exclusively street-based; 1 exclusively wine shop–based, where transactions with clients are brokered by wine shop patrons; 5 exclusively indoor-based); and 3 where the sex-work environment was not described. Studies were diverse according to the perpetrator (exclusively client; workplace [e.g., could include any combination of police, clients, other sex workers, the public]; any perpetrator, including nonpaying partners, police, clients, other); the type of violence (any or combined violence [could include any combination of sexual, physical, emotional], sexual violence, physical violence); and the timescale over which women were asked to estimate violent acts occurring (ever or lifetime, past year, past 6 months, past 3 months). Overall, 37 studies were of female sex workers only, with 3 studies of female and transgender (male-to-female) sex workers, and 1 study of transgender sex workers only. There were no studies of male sex workers.

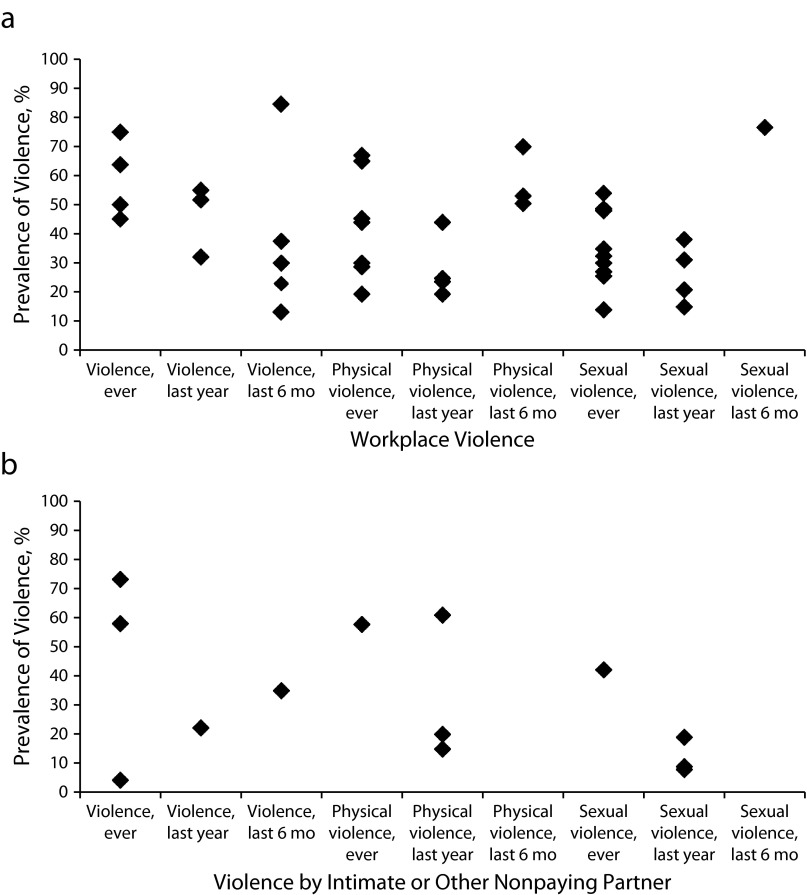

The 41 peer-reviewed articles included 105 estimates of the overall prevalence of various violence measures (Table B). Ever or lifetime of any or combined violence by any or combined perpetrators ranged from 41% to 65% (n = 2), with no estimates for the past 6 months or past year (Figure 2). Ever or lifetime of any or combined workplace violence, physical workplace violence, and sexual workplace violence ranged from 45% to 75% (n = 4; any or combined), 19% to 67% (n = 7; physical), and 14% to 54% (n = 9; sexual) and in the past year ranged from 32% to 55% (n = 3), 19% to 44% (n = 4), and 15% to 31% (n = 3), respectively (Figure 3a). Ever or lifetime of any or combined violence, physical violence, and sexual violence by intimate or nonpaying partners ranged from 4% to 73% (n = 3; any or combined), 57% (n = 1; physical), and 42% (n = 1; sexual) and in the past year ranged from 22% (n = 1), 15% to 61% (n = 3), and 8% to 19% (n = 3), respectively (Figure 3b).

FIGURE 2—

Violence prevalence estimates for all included studies, including violence committed against sex workers by any or combined perpetrators.

Note. All prevalence estimates came from studies that assessed correlates of violence bivariately or multivariably; studies that included only prevalence estimates were not specifically searched for, and thus this set of studies is an underestimate of the total violence prevalence estimates available in the literature.

FIGURE 3—

Violence prevalence estimates for all included studies, including (a) workplace violence committed against sex workers (i.e., violence committed within the context of sex work, such as by police, clients, pimps, madams, etc.) and (b) violence committed against sex workers by an intimate or other nonpaying partner.

Note. All prevalence estimates came from studies that assessed correlates of violence bivariately or multivariably; studies that included only prevalence estimates were not specifically searched for, and thus this set of studies is an underestimate of the total violence prevalence estimates available in the literature.

Risk Contexts of Violence

In 28 studies, 47 different violence measures were examined as outcomes in multivariable analysis and had a statistically significant relationship with at least 1 covariate (Table 1). Key relationships are summarized under the following 6 themes.

Legal policies and the regulation of sex work.

In 4 studies, multiple measures of policing practices (e.g,. arrest, violence, or coercion) remained independently associated with increased violence against sex workers. Police arrest is a direct measure of enforcement of criminalized laws, whereas police violence and coercion are enabled in settings where some or all aspects of sex work are criminalized.1,78 Sex workers who had ever been arrested or imprisoned were more likely to have experienced physical violence by clients in Britain,55 and physical or sexual violence by clients in India.46 In Canada, previous police violence (physical or sexual), confiscation of drug paraphernalia by police, and enforced police displacement away from main areas were independently associated with experiencing violence by clients and any physical violence.60 In India, multiple measures of police violence and coercion (police having coercive sexual activity with respondent, police accepting a bribe or gift from respondent, police taking condoms away, police raiding workplace) as well as police arrest were independently associated with increased physical or sexual violence by clients.48 Of sex workers who experienced sexual violence in the past year in India, 6.6% reported that the main perpetrators were the police37; of the total sample of sex workers in Bangladesh, 6.8% and 18.2% reported sexual violence in the past year by police and political officials, respectively, in 2000, up from 0.7% and 6.3% in 1998.68

Importantly, 1 study in India examined exposure to a combined structural and community-led intervention, which included developing partnerships with police, police training and sensitization of sex work issues, and educating sex workers of their legal rights, alongside community empowerment. Exposure to the intervention was associated with decreased rates of violence over time by any perpetrator in the past year.37

Work environments.

Four studies examined the role of work environment (i.e., places of solicitation and servicing clients) in promoting or reducing risk of violence against sex workers, with our review showing the highly heterogeneous and context-specific nature of work environments. In India, sex workers who worked in their homes (vs brothels, lodges, or public places) were less likely to experience sexual violence by clients.40 In Britain, sex workers who worked outdoors versus indoors had greater than 6 times higher odds of experiencing client violence.44 In Canada, sex workers who serviced clients in cars or public places (vs indoor settings) were more likely to experience client violence60; in Russia, sex workers in street-based settings were more likely to experience sexual violence by police.54

Economic constraints and conditions.

Economic constraints or conditions were examined in 4 studies. In China, increased economic pressure on sex workers who came from or were brought from Russia, Vietnam, Thailand, and mainland China was associated with an increase in any violence ever by clients, as measured with a client violence scale.43 In India, currently being in debt was associated with experiencing physical violence by any perpetrator.58 Also in India, residential instability (> 5 evictions in the past 5 years) was associated with experiencing both sexual and physical violence by any perpetrator.57 In Canada, being homeless was associated with experiencing both sexual and physical violence by intimate or nonpaying partners.60

Gender inequality, power, and social stigmatization of sex work.

Indirect or direct measure of gender inequality (n = 4 studies); individual, relationship, or collective power (n = 4 studies); and social stigma (n = 1 study) were considered as risks or protective factors of violence among sex workers. For example, educational attainment can be constructed as a direct structural marker of marginalization and a lack of opportunities for women. In India, sex workers who were illiterate were more likely to have experienced sexual violence by clients.40 In China, sex workers with higher education were less likely to have ever experienced violence by clients (measured on a violence scale), and increased sexual health knowledge was positively associated with ever experiencing any or combined workplace violence.43 In India, having a greater number of people who spoke about family violence was associated with reduced sexual violence by any or combined perpetrators,51 and in Mexico, sex workers had a higher likelihood of experiencing violence in the past 6 months by an intimate or nonpaying partner if the participant had experienced abuse as a child.63

Also in India, a stronger sense of power, both individual and collective (and which itself was associated with engagement with HIV programs and community mobilization activities), was associated with reduced physical or sexual violence by “more powerful groups,”39 and sex workers who were members of a sex worker group or collective experienced significantly less violence than nonmembers.38 In Mexico, an inverse relationship between average relationship power and violence was also observed, with a higher power score associated with a reduced likelihood of violence.63 In Canada, client condom refusal was associated with multiple workplace and other violence measures.60

The effects of structural stigmatization are difficult to measure quantitatively, and we found only 1 study that addressed the association between workplace stigma and violence, albeit indirectly. In India, sex workers who were initiated through a traditional practice of Devadasi were much less likely to experience sexual violence by clients in the past year compared with sex workers who entered the profession for other reasons, even after adjustment for the geographic location of work (rural vs urban) and the home-based nature of Devadasi sex-work environments, which also likely had a protective effect against violence.40 The Devadasi practice is an ancient religious practice in which girls were dedicated, through marriage, to different deities, after which they perform various temple duties including providing sexual services to priests and patrons of the temples. Today, despite a law banning the practice, it continues, but in a different form. Women who are initiated as Devadasis engage in sex work outside the temple context and this form of sex work is socially and culturally embedded in many communities.40

Population movement and sexual coercion of women and girls.

A study based in Macau, China (a city with a high level of involvement in the entertainment industry, known as “China’s Las Vegas”), found that both migrant Vietnamese and Thai sex workers were less likely to have ever experienced violence by clients than were migrant mainland Chinese sex workers.43 In India, sex workers who worked in brothels and were under contract to madams or brothel owners outside their home districts (compared with those who engaged in sex work only in their home districts) were more likely to experience both physical and sexual workplace violence in the past 6 months.50 Also in India, sex workers who were highly mobile (e.g., worked in 3 or more villages or towns in the past year) were more likely to experience both sexual and physical violence in the past 6 months, by any perpetrator56; however, another study in India examined the complexity of mobility as both a risk and protective factor with multiple measures of mobility (4 or more moves in the past 2 years vs 4 or fewer moves; staying for 1 month or less at the last 2 places vs longer-term mobility; mobility to religious festivals; mobility to places frequented by seasonal male migrant workers) were associated with experiencing physical or sexual violence in the past 6 months, by any perpetrator.59

In addition to voluntary population movement, a history of trafficking or forced labor was associated with violence against sex workers. In Thailand, sex workers who were forced or coerced into sex work (i.e., defined as “trafficked”) were more likely to have experienced sexual violence at sex work initiation and any violence or mistreatment (general, workplace, past week) compared with women who were not trafficked.45 In India, sex workers who were forced or coerced into sex work were more likely to experience physical or sexual violence by any perpetrator49,52 and in the first month of sex work.62

Interpersonal, individual, and psychosocial associations.

A number of interpersonal factors were associated with experiencing violence (e.g., marital status42,55). Several studies reported associations between partner-level sexual practices and violence: in India, having anal sex with 5 or more casual sexual partners in the past week was associated with sexual violence by any or combined perpetrator61; in Kenya, having more sexual partners was associated with workplace sexual violence42; and in Mexico, having a spouse or steady partner who had sexual intercourse with another partner was associated with any or combined violence by intimate or nonpaying partners.63 In Russia, being raped by a client was associated with sexual violence in the past year by police.54 Individual behavior or psychosocial factors were measured in a number of studies. In China, 5 measures used to assess psychosocial distress (i.e., depression, loneliness, and suicidal behavior as well as 2 related to drug use) were associated with ever experiencing violence by clients and intimate or nonpaying partners.53 In Mongolia, participating in different individual behavioral interventions was associated with reduced physical and sexual violence by intimate or nonpaying partners.41

Individual alcohol and drug use behaviors of sex workers were associated with elevated rates of violence in multiple settings, with no studies examining drug or alcohol use of violence perpetrators or clients, and only 2 studies examining drug use at the interpersonal level (e.g., concomitant sexual and drug risks in sex-work transactions). In Kenya, binge drinking was associated with sexual violence by clients,42 and in the United States, injecting heroin and trading sexual intercourse for money or drugs at a crack house were significantly associated with any violence by clients.47 In Russia both recent injecting and binge drinking were significantly associated with sexual violence by police,54 and in China sex workers who used alcohol at “risky,” “heavy,” or “hazardous” drinking levels were more likely to have experienced client-perpetrated sexual violence than those who did not (12 total associations),64 and sex workers who reported general drug use were more likely to ever have experienced violence by clients.53

Interpersonal factors operated together with drug use to produce higher risk for violence in India: sex workers who had unprotected sexual activity with a nonspousal partner and more than 20 days of alcohol consumption in the past 30 days (vs no unprotected sex and 0 to 9 days of alcohol consumption) and sex workers with 2 or more partners with strong tendency to drink alcohol before sexual activity (vs no partners) had increased probability of sexual violence by any partner.51 By contrast, sex workers in Britain with higher alcohol use were less likely to experience physical violence by clients.55 Compared with the large number of studies examining individual drug use behaviors of sex workers, only 1 study examined more upstream contexts of drug use environment. In Canada, sex workers who were unable to access drug treatment had higher risk for physical violence and any violence by clients.60

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified consistent evidence of a high burden of violence against sex workers globally. Despite a substantial human rights and public health concern, there are major gaps in documentation of violence against sex workers in most parts of the world, with the majority of studies from Asia, and only 2 studies from Central Africa. The review reveals a growing body of research demonstrating a link between social, physical, policy, and economic factors, alongside more proximal interpersonal and individual factors (e.g., sexual and drug risk practices, psychosocial factors), and elevated rates of violence against sex workers. Results indicate the need for more methodological innovation (e.g., longitudinal studies, mixed methods, multilevel analyses) in research and intervention design and evaluation, as well as increased measurement rigor, to better document and respond to violence against sex workers.

Key Correlates of Violence Against Sex Workers

Policing practices as enforcement of laws, either lawful (e.g., arrest) or unlawful (e.g., coercion, bribes, violence) are a critical means for measuring how criminalization and regulation of sex work may have a negative impact on risks of violence against sex workers. In our review, there was consistent evidence of an independent link between policing practices (e.g., arrest, violence, coercion) and elevated rates of physical or sexual violence against sex workers.46,48,55,60 These data support growing evidence-based calls, including World Health Organization and United Nations guidelines and Global Commission on HIV and Law,8–10 of the critical public health and human rights need to remove criminalized laws targeting sex work (e.g., decriminalization) as a barrier to basic health, safety, and rights to protection of among sex workers.

In addition to legislative changes at national or district levels, structural policy changes through police–sex worker engagement have also been proposed.8–10 Our review found 1 study showing the success of a combined structural and community-led intervention in a district in southern India (including engagement with police stakeholders, sensitivity training of police, and community empowerment) and associations with reduced violence experienced by sex workers over the year. Although challenges with replication of structural and community-led interventions are well-known,79 qualitative literature suggests that sex work engagement with police may have had success in other settings in changing the environment within which sex work operates and promoting increased capacity for sex workers to safely engage in sex work and report violence to authorities.80

In our review, we also found evidence of the role of the work environment in shaping risks for violence among sex workers, with data from 3 countries showing sex workers in street or public-place environments to be at highest risk of violence. Laws that criminalize or regulate sex-work environments (e.g., prohibitions on operating bawdy houses) shape access to indoor work environments for sex workers in many settings globally.1 Although there is growing literature of the role of supportive indoor sex-work environments (e.g., supportive venue-based policies and practices, enhanced physical access to health services) in promoting condom use,80–82 our review found no studies examining the more complex and nuanced nature of work environments in promoting or reducing rates of violence among sex workers. In light of important qualitative work from a number of settings,37,80,83 there is a clear need for epidemiology to better document these structural interventions as they unfold.

Alongside known proximal risks for violence (e.g., drug use, sexual risks with intimate, nonpaying partners), our review also documented a number of more upstream factors as linked to risks of violence against sex workers, including gender and economic inequities, voluntary migration and population movement, and history of trafficking or forced labor, further supporting need for violence prevention at structural and community levels. Of note, although drug use was measured as an individual behavior among sex workers in a number of studies, no studies examined drug use of the perpetrators and few studies considered the interpersonal or partner-level nature of drug use within sex-work environments.

As epidemiology continues to better measure and document both upstream and downstream factors, there is increasing need for multicomponent structural and community-led interventions to address and respond to violence against sex workers. Only 2 studies that examined interventions were documented in this review, suggesting a major scientific gap in evaluating interventions to reduce violence against sex workers.37,41 Because many programs and interventions happen organically (e.g., sex work–led interventions) or outside the control of science (e.g., policing policy changes), there is a critical need for more methodological innovation in evaluating interventions, in partnership with sex-work communities, including engagement with a range of stakeholders (e.g., police, clients, managers, government). Furthermore, because of the highly context-specific nature within which social, physical, policy, economic, and interpersonal factors are embedded, better dialogue between epidemiology and social sciences is a priority.

Strengths and Limitations

The cross-sectional nature of almost all of the studies available, with most based on convenience samples, limits the strength of the evidence and highlights the need for research that is of higher methodological quality. Cross-sectional studies cannot assess temporality and, thus, causality in the relationship between an explanatory variable or risk factor (e.g., being arrested) and an outcome. Some of the risk factors in the studies assessed would better be viewed as outcomes, or as being in a complex synergistic relationship with the outcome. Longitudinal studies among sex workers are rare, but critically needed to shed light on drivers of violence against sex workers, as has been done in other populations.24 More work also needs to be done on understanding how to measure structural risk factors for violence that may operate differently on micro and macro levels. In this regard, there is a strong body of social science and qualitative literature as theoretical literature on structural interventions that can be used to help guide epidemiology.33,79 The majority of associations were simple risk factor–outcome associations, which fail to take into account the complex interrelationships between factors that produce violence (e.g., social stigmatization of sex work, criminalization of sex work).

We identified no studies on perpetrators of violence against sex workers in this review, with all studies focusing on samples of sex workers. This lack of perspective is a substantial limitation to understanding how violence against sex workers can be mitigated and to developing effective prevention that includes both men and women. Increasing calls are being made to include clients, intimate or nonpaying partners, and third parties (e.g., police, managers) of sex workers in research and programming with sex workers, particularly with respect to HIV and other STIs.84–86

Because we limited the search to English-language studies from North American databases, studies published elsewhere may not be included. As probability-based sampling frames of sex workers are difficult to create, it is likely that the studies we included have limited generalizability across settings. Our review only included peer-reviewed literature of epidemiological studies and excluded other potential sources of data, both peer-reviewed qualitative and social science literature and gray literature. Although such data can be useful, we chose to restrict our review to capture the highest quality peer-reviewed evidence to better inform responses to violence against sex workers. It is possible that we missed some studies that would otherwise have been eligible; this is a limitation faced by all systematic reviews. However, we attempted to address this limitation by having multiple reviewers (who each conducted independent reviews using the same method with which to search and extract data) and by contacting authors of publications to clarify if or how the study should be included and classified.

As our study’s aim was to review the correlates of violence, we did not search for or include studies that included only violence prevalence estimates without assessing correlates (i.e., we only included violence prevalence estimates that came from studies examining correlates of violence with bivariate or multivariable analysis). Thus, the violence prevalence estimates provided in this study cannot be considered a comprehensive collection and are an underestimate of the total violence prevalence estimates available in the literature. Nevertheless, results consistently showed a high prevalence of violence against sex workers in a range of settings.

Few studies examined violence by intimate or other nonpaying partners and thus we were unable to make conclusions related to prevalence or correlates of intimate or other nonpaying partner violence compared with workplace violence. We were limited from making comparisons between female sex workers and transgender or male sex workers, because of the few studies available (3 studies with a sample population that included combined female and transgender; 1 study with a sample of men who have sex with men and transgenders). As gender or sexual identity has been identified as a key factor influencing pathways of violence against sex workers in qualitative studies,30 the lack of studies on transgender and male sex workers is a key gap in research that should be addressed in future studies. For each correlate, a limited number of studies was available to draw definitive conclusions. Moreover, we could not conduct a meta-analysis because of the range of measures of different risk factors and violence outcomes. A standardized approach to measuring and collecting data to document prevalence and correlates of violence against sex workers would help address these limitations.

Conclusions

This systematic review reveals a high burden of violence against sex workers globally, and documents existing evidence of the social, physical, policy, economic, and interpersonal correlates of violence against sex workers. The review supports increasing evidence-based calls to make violence against sex workers a public health and human rights priority on national and international policy agendas, and the urgent need for structural research and interventions to better document and respond to the contextual factors shaping violence against sex workers. These include structural changes to legal and policy environments (e.g., decriminalization, policing practices), work environments, gender and economic inequities, population movement, and stigma. In this regard, measurement and methodological innovation (e.g., longitudinal, multilevel, and mixed-methods research) and rigor, in partnership with sex-work communities, are critical.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this review was made possible through the German BACKUP Initiative, implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit project grant to the World Health Organization. This work was partially supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Gender, Violence and HIV Team Grant (TVG-115616).

This systematic review was commissioned in part by the Department of Reproductive and Research of the World Health Organization. We thank Ruth Morgan Thomas and Penelope Saunders from the Network of Sex Work Projects for their leadership and support in the project.

Human Participant Protection

No ethical review was needed because this was a review of already published, secondary data.

References

- 1.Shannon K, Csete J. Violence, condom negotiation, and HIV/STI risk among sex workers. JAMA. 2010;304(5):573–574. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin A. Violence Against Sex Workers and HIV Prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Gender, Women and Health, World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodyear MDE, Cusick L. Protection of sex workers. BMJ. 2007;334(7584):52–53. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39087.642801.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. CBC News in Depth. Robert Pickton: The missing women of Vancouver. Canadian Broadcasting Company. January 19, 2007. Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/news2/background/pickton/history.html. Accessed February 24, 2014.

- 5. Doucette C. Man, 26, arrested for killing 72-year-old sex trade worker. Toronto Sun. September 11, 2013. Available at: http://www.torontosun.com/2013/09/11/toronto-police-to-update-north-york-murder-investigations. Accessed February 24, 2014.

- 6. Laville S. Olympics welcome does not extend to all in London as police flex muscles. The Guardian. May 4, 2012. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2012/may/04/olympics-welcome-london-police. Accessed February 24, 2014.

- 7. Chakraborty D. Sex worker raped, murdered in Asansol. The Times of India. April 10, 2012. Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/Sex-worker-raped-murdered-in-Asansol/articleshow/12603011.cms. Accessed February 24, 2014.

- 8.Garcia-Moreno C, Watts C. Violence against women: an urgent public health priority. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(1):2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.085217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.USAID Gender Equality and Female Empowerment Policy. Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Violence against women: fact sheet no. 239. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009.

- 11.Heise LL. Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-partner Sexual Violence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramsky T, Watts C, Garcia-Moreno C et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nerøien AI, Schei B. Partner violence and health: results from the first national study on violence against women in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(2):161–168. doi: 10.1177/1403494807085188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caetano R, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence and depression among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(10):661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golding J. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. J Fam Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang AJ, Kennedy CM, Stein MB. Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD among female victims of intimate partner violence. Depress Anxiety. 2002;16(2):77–83. doi: 10.1002/da.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blasco-Ros C, Sanchez-Lorente S, Martinez M. Recovery from depressive symptoms, state anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in women exposed to physical and psychological, but not to psychological intimate partner violence alone: a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):98. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2008;15(4):221–231. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M et al. Factors associated with HIV sero-status in young rural South African women: connections between intimate partner violence and HIV. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(6):1461–1468. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decker MR, Seage GRI, Hemenway D et al. Intimate partner violence functions as both a risk marker and risk factor for women’s HIV infection: findings from Indian husband–wife dyads. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(5):593–600. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a255d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman JG, Gupta J, Decker MR, Kapur N, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. BJOG. 2007;114(10):1246–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Jama PN, Puren A. Associations between childhood adversity and depression, substance abuse and HIV and HSV2 incident infections in rural South African youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(11):833–841. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shannon K. The hypocrisy of Canada’s prostitution legislation. CMAJ. 2010;182(12):1388. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simić M, Rhodes T. Violence, dignity and HIV vulnerability: street sex work in Serbia. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhodes T, Simic M, Baros S, Platt L, Zikic B. Police violence and sexual risk among female and transvestite sex workers in Serbia: qualitative study. BMJ. 2008;337:a811. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green ST, Goldberg DJ, Christie PR et al. Female streetworker–prostitutes in Glasgow: a descriptive study of their lifestyle. AIDS Care. 1993;5(3):321–335. doi: 10.1080/09540129308258615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crago A-L. Arrest the violence: human rights abuses against sex workers in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Open Society Institute & Sex Workers’ Rights Advocacy Network. 2009. Available at: http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/reports/arrest-violence-human-rights-violations-against-sex-workers-11-countries-central-and-eastern. Accessed February 24, 2014.

- 33.Rhodes T. The ‘risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13(2):85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchard JF, Aral SO. Emergent properties and structural patterns in sexually transmitted infection and HIV research. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(suppl 3):iii4–iii9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(4):911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marshall BDL, Werb D. Health outcomes associated with methamphetamine use among young people: a systematic review. Addiction. 2010;105(6):991–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beattie TSH, Bhattacharjee P, Ramesh BM et al. Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(476) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhattacharjee P, Prakash R, Pillai P et al. Understanding the role of peer group membership in reducing HIV-related risk and vulnerability among female sex workers in Karnataka, India. AIDS Care. 2013;25(suppl 1):S46–S54. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.736607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blanchard AK, Mohan HL, Shahmanesh M et al. Community mobilization, empowerment and HIV prevention among female sex workers in south India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blanchard JF, O’Neil J, Ramesh BM, Bhattacharjee P, Orchard T, Moses S. Understanding the social and cultural contexts of female sex workers in Karnataka, India: implications for prevention of HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(suppl 1):S139–S146. doi: 10.1086/425273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlson CE, Chen J, Chang M et al. Reducing intimate and paying partner violence against women who exchange sex in Mongolia: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(10):1911–1931. doi: 10.1177/0886260511431439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chersich MF, Luchters SMF, Malonza IM, Mwarogo P, King’ola N, Temmerman M. Heavy episodic drinking among Kenyan female sex workers is associated with unsafe sex, sexual violence and sexually transmitted infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(11):764–769. doi: 10.1258/095646207782212342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi SY. Heterogeneous and vulnerable: the health risks facing transnational female sex workers. Sociol Health Illn. 2011;33(1):33–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Church S, Henderson M, Barnard M, Hart G. Violence by clients towards female prostitutes in different work settings: questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2001;322(7285):524–525. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7285.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Decker MR, McCauley HL, Phuengsamran D, Janyam S, Silverman JG. Sex trafficking, sexual risk, sexually transmitted infection and reproductive health among female sex workers in Thailand. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(4):334–339. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.096834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deering KN, Bhattacharjee P, Mohan HL et al. Violence and HIV risk among female sex workers in Southern India. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(2):168–174. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e31827df174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Wada T, Gilbert L, Wallace J. Correlates of partner violence among female street-based sex workers: substance abuse, history of childhood abuse, and HIV risks. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2001;15(1):41–51. doi: 10.1089/108729101460092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erausquin JT, Reed E, Blankenship KM. Police-related experiences and HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 5):S1223–S1228. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.George A, Sabarwal S. Sex trafficking, physical and sexual violence, and HIV risk among young female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;120(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.George A, Sabarwal S, Martin P. Violence in contract work among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 5):S1235–S1240. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Go VF, Srikrishnan AK, Parker CB et al. High prevalence of forced sex among non-brothel based, wine shop centered sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):163–171. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9758-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gupta J, Reed E, Kershaw T, Blankenship KM. History of sex trafficking, recent experiences of violence, and HIV vulnerability among female sex workers in coastal Andhra Pradesh, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114(2):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hong Y, Zhang C, Li X, Liu W, Zhou Y. Partner violence and psychosocial distress among female sex workers in China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e62290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Odinokova V, Rusakova M, Urada LA, Silverman JG, Raj A. Police sexual coercion and its association with risky sex work and substance use behaviors among female sex workers in St. Petersburg and Orenburg, Russia. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Platt L, Grenfell P, Bonell C et al. Risk of sexually transmitted infections and violence among indoor-working female sex workers in London: the effect of migration from Eastern Europe. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(5):377–384. doi: 10.1136/sti.2011.049544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reed E, Gupta J, Biradavolu M, Blankenship KM. Migration/mobility and risk factors for HIV among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: implications for HIV prevention. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(4):e7–e13. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reed E, Gupta J, Biradavolu M, Devireddy V, Blankenship KM. The role of housing in determining HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: considering women’s life contexts. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(5):710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reed E, Gupta J, Biradavolu M, Devireddy V, Blankenship KM. The context of economic insecurity and its relation to violence and risk factors for HIV among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(suppl 4):81–89. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saggurti N, Jain AK, Sebastian MP et al. Indicators of mobility, socio-economic vulnerabilities and HIV risk behaviours among mobile female sex workers in India. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):952–959. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9937-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Montaner JS, Tyndall MW. Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ. 2009;339:b2939. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaw SY, Lorway RR, Deering KN et al. Factors associated with sexual violence against men who have sex with men and transgendered individuals in Karnataka, India. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e31705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silverman JG, Raj A, Cheng DM et al. Sex trafficking and initiation-related violence, alcohol use, and HIV risk among HIV-infected female sex workers in Mumbai, India. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 5):S1229–S1234. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ulibarri MD, Strathdee SA, Lozada R et al. Intimate partner violence among female sex workers in two Mexico–U.S. border cities: partner characteristics and HIV risk behaviors as correlates of abuse. Psychol Trauma. 2010;2(4):318–325. doi: 10.1037/a0017500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang C, Li X, Stanton B et al. Alcohol use and client-perpetrated sexual violence against female sex workers in China. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18(3):330–342. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.712705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cwikel J, Ilan K, Chudakov B. Women brothel workers and occupational health risks. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):809–815. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fang X, Li X, Yang H et al. Profile of female sex workers in a Chinese county: does it differ by where they came from and where they work? World Health Popul. 2007;9(1):46–64. doi: 10.12927/whp.2007.18695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harcourt C, Beek I, Heslop J, McMahon M, Donovan B. The health and welfare needs of female and transgender street sex workers in New South Wales. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25(1):84–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jenkins C, Rahman H. Rapidly changing conditions in the brothels of Bangladesh: impact on HIV/STD. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(3, suppl A):97–106. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.4.97.23882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kurtz SP, Surratt HL, Inciardi JA, Kiley MC. Sex work and “date” violence. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:357–385. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lalor KJ. The victimization of juvenile prostitutes in Ethiopia. Int Soc Work. 2000;43:227–242. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Panchanadeswaran S, Johnson SC, Sivaram S et al. A descriptive profile of abused female sex workers in India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28(3):211–220. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v28i3.5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raphael J, Shapiro DL. Violence in indoor and outdoor prostitution venues. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:126–139. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sarkar K, Bal B, Mukherjee R et al. Sex-trafficking, violence, negotiating skill, and HIV infection in brothel-based sex workers of Eastern India, adjoining Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26(2):223–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silbert MH, Pines AM. Occupational hazards of street prostitutes. Crim Justice Behav. 1981;8:395–399. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wechsberg WM, Luseno WK, Lam WK. Violence against substance-abusing South African sex workers: intersection with culture and HIV risk. AIDS Care. 2005;17(suppl 1):S55–S64. doi: 10.1080/09540120500120419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Willman A. Risk and reward in Managua’s commercial sex market: the importance of workplace. J Hum Dev Capabilities. 2010;11(4):503–531. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yi H, Mantell JE, Wu RR, Lu Z, Zeng J, Wan YH. A profile of HIV risk factors in the context of sex work environments among migrant female sex workers in Beijing, China. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(2):172–187. doi: 10.1080/13548501003623914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Global Commission on HIV and the Law: Risks, Rights and Health. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Latkin C, Weeks M, Glasman L, Galletly C, Albarracin D. A dynamic social systems model for considering structural factors in HIV prevention and detection. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(suppl 2):222–238. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9804-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Krüsi A, Chettiar J, Ridgway A, Abbott J, Strathdee SA, Shannon K. Negotiating safety and sexual risk reduction with clients in unsanctioned safer indoor sex work environments: a qualitative study. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(6):1154–1159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S et al. Environmental–structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(1):120–125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Withers M, Dornig K, Morisky DE. Predictors of workplace sexual health policy at sex work establishments in the Philippines. AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):1020–1025. doi: 10.1080/09540120701294229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Argento E, Reza-Paul S, Lorway R et al. Confronting structural violence in sex work: lessons from a community-led HIV prevention project in Mysore, India. AIDS Care. 2011;23(1):69–74. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shannon K, Montaner JSG. The politics and policies of HIV prevention in sex work. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):500–502. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lowndes CM, Alary M, Labbé AC et al. Interventions among male clients of female sex workers in Benin, West Africa: an essential component of targeted HIV preventive interventions. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(7):577–581. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Syvertsen JL, Roberston AM, Abramovitz D et al. Study protocol for the recruitment of female sex workers and their non-commercial partners into couple-based HIV research. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]