Abstract

Objectives. We examined a population-wide program, Pennsylvania’s Healthy Steps for Older Adults (HSOA), designed to reduce the incidence of falls among older adults. Older adults completing HSOA are screened and educated regarding fall risk, and those identified as being at high risk are referred to primary care providers and home safety resources.

Methods. From 2010 to 2011, older adults who completed HSOA at various senior center sites (n = 814) and a comparison group of older adults from the same sites who did not complete the program (n = 1019) were recruited and followed monthly. Although participants were not randomly allocated to study conditions, the 2 groups did not differ in fall risk at baseline or attrition. We used a telephone interactive voice response system to ascertain the number of falls that occurred each month.

Results. In multivariate models, adjusted fall incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were lower in the HSOA group than in the comparison group for both total (IRR = 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.72, 0.96) and activity-adjusted (IRR = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.70, 0.93) months of follow-up.

Conclusions. Use of existing aging services in primary prevention of falls is feasible, resulting in a 17% reduction in our sample in the rate of falls over the follow-up period.

The public health significance of falls among older adults is clear. As noted by the National Council on Aging,

falls are the leading cause of injury related deaths of older adults, the primary reason for older adult injury emergency department visits, and the most common cause of hospital admissions for trauma.1

In 2011, the rate of nonfatal fall injuries requiring emergency department care was 2301 per 100 000 among people aged 50 to 54 years but 14 159 per 100 000 among people 85 years or older.2

Self-report measures from health surveys confirm that there is a high prevalence of falls (30%–40%) among people 65 years or older and that the prevalence increases with age (40%–50% among those 80 years or older), as does the inability to get up from falls.3,4 Even noninjurious falls are disabling in that they are associated with activity restriction, isolation, deconditioning, and depression.5–8 In 2005, medical care costs associated with falls in the United States among people 50 years or older totaled about $13.5 billion (including deaths, hospital care, and emergency department admissions).2 A challenge for public health is to decrease the risk of falls without encouraging reduced physical activity, which carries other risks.

Risk factors for falls include sedative use, cognitive impairment, lower extremity weakness, poor reflexes, balance and gait abnormalities, foot problems, and environmental hazards.9,10 Community-level efforts have adapted clinical interventions in addressing such risk factors. A review of 5 prospective but nonrandomized community trials involving matched control communities suggested that fall-related fractures could potentially be reduced by 6% to 33%,11 and meta-analyses and systematic reviews provide support for the effectiveness of multifactorial assessments and management of fall risk.12 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has compiled a compendium of successful interventions that can be used by public health practitioners and community-based organizations.13,14

Recommendations for optimal means of preventing falls are still evolving.15,16 A Cochrane review reported that exercise and home safety programs reduce the rate of falls and risk of falling but did not reveal any benefits of interventions that increase knowledge regarding fall prevention without additional components.3

Pennsylvania’s Department of Aging has opted for a hybrid program in which older adults can take advantage of an intervention that offers, within the current aging service infrastructure, risk screening for falls and education regarding prevention. This voluntary program, Healthy Steps for Older Adults (HSOA), is available to all adults 50 years or older. Those identified as having a high risk for falls are referred to primary care providers and encouraged to complete home safety assessments. Because it relies on referrals to physician care rather than direct clinical interventions, the program may be less effective among people at high risk for falls; however, it is scalable across the state and reaches large numbers of people. In the case of some public health challenges, such a strategy may be more effective than more intensive interventions targeting high-risk individuals.17

There is a lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of this short-term, low-cost, population-wide program in reducing the incidence of falls among its participants, however. Here we report the results of a statewide evaluation of HSOA, which uses the state’s network of providers of aging services in its primary prevention efforts.

METHODS

From 2010 to 2011, we enrolled a large group of older adults (n = 814) who had completed HSOA at various senior center sites (503 who had completed the program for the first time and another 311 who had completed the program in prior years). First-time participants represented 12.5% of the total number of older adults (n = 4040) enrolled in the program from 2010 to 2011 (Pennsylvania tracks only first-time participants in the program). A comparison group was recruited from the same senior center sites at the same time. These were people who participated in center activities but did not enroll in HSOA because they were not present on the day of the program or declined to take part. Both groups completed a baseline telephone interview after providing informed consent, and all participants were followed for up to a year with monthly telephone interviews to track falls; they also completed telephone assessments at 6 and 12 months.

HSOA is a half-day workshop open to anyone who wishes to attend, and it is offered at no cost to participants. Senior center staff and lay volunteers conduct balance assessments and provide education on falls as well as referrals. Participating county Area Agencies on Aging commit to offering the program to a prespecified number of participants each year and are reimbursed by the state at $70 per participant to cover program expenses. Importantly, HSOA is a walk-in program. Although some sites seek preregistration, in practice attendance mostly depends on who attends the senior center on a day the program is offered. The short interval between the time the program is announced and offered, as well as the difficulty in not offering (or delaying) the program in certain senior centers so that a control condition could be established, made random allocation difficult.

The project included a data-sharing agreement with the Pennsylvania Department of Aging, and staff from that department as well as county health promotion coordinators were involved in the program at the local sites. County Area Agency on Aging directors and health educators from the Department of Aging were engaged in the project from the start, both in the design phase and in follow-ups through monthly conference calls. The results of this study will be used by program staff to refine the intervention and its outreach activities.

Intervention

Pennsylvania’s Department of Aging has offered HSOA on a statewide basis through its senior centers since 2007.18 The program was developed under the auspices of Health Research for Action at the University of California, Berkeley.19 To date, about 32 000 older adults in Pennsylvania have completed the program (with between 4000 and 7000 doing so each year). Overall, 40 of the state’s 67 counties have hosted HSOA, which is funded though federal and state sources and administered by the Department of Aging’s health promotion unit, PrimeTime Health, which trains providers in county Area Agencies on Aging to offer the program.

Senior centers and allied sites host the program, and interested older adults can complete HSOA as part of their normal attendance at senior centers or because of a specific interest in fall prevention. The Pennsylvania Department of Aging works with county Area Agencies on Aging (which in turn deliver the program at local senior centers) in program implementation efforts. Thus, HSOA represents the concerted use of a state’s aging service infrastructure to deliver a program to older adults designed to prevent falls.

The program includes the following elements: physical performance assessments of balance and mobility conducted by staff or trained volunteers (“timed up and go,” one-legged stand, chair stand), physician care or home safety referrals for participants who score below age- and gender-based norms on performance assessments, and a 2-hour fall prevention class involving recognition of home hazards and risk situations as well as a demonstration of exercises designed to improve balance and mobility. Two of the performance tests, timed up and go (a test used to assess a person’s mobility) and the chair stand, are validated assessment tools included in the CDC’s STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries) fall assessment tool kit.20

Program data, which are entered into a Web-based system, were made available to our research team through a data-sharing agreement. The PrimeTime Health office of the Pennsylvania Department of Aging ensures program fidelity by training staff at HSOA sites in conducting balance and mobility assessments, providing referrals to physicians and home safety assessments when indicated, and adhering to program guidelines on presenting information related to fall risk, exercise, and home safety. PrimeTime Health also ensures fidelity by monitoring data entry, conducting monthly conference calls with county Area Agencies on Aging, and surveying a random 10% of HSOA participants about their experience in the program.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of falls up to as many as 12 months of follow-up, which we measured as fall-months (i.e., months in which participants reported a fall) per 100 person-months of follow-up. A secondary outcome was fall-months per 100 person-months of follow-up adjusted for participants’ activity levels. In both cases we tracked the occurrence of any fall, as opposed to the overall number of falls in a month, because subsequent interviews with individuals who had fallen showed that 89% of fall-months involved a single fall. We were also concerned that the reported number of falls in a month might be less reliable than reports of any fall. We used the same denominators to examine the number of individuals in each study arm who had fallen. Falls were defined as any occasion when a person ended up on the floor or ground without being able to stop or prevent it.

In the activity-based secondary outcome, the denominator for follow-up time was adjusted according to self-reports of activity. It was important to include this adjustment for activity over the follow-up period because older people with balance problems or mobility limitations may reduce their daily activities to minimize their risk of falling.21–23 To allow us to make this adjustment, we asked participants to report, for each month of follow-up, the number of days in the preceding week in which they were physically active. We defined physically active as moderate or vigorous activity for at least 30 minutes on a given day. Using these reports of activity, we constructed an “active month” equivalent (e.g., a participant reporting 4 of 7 days of activity in the preceding week would have 16 days of activity in the month and contribute 0.53 months of follow-up rather than 1 month). To calculate incidence density, we summed the number of months in which respondents reported a fall (fall-months) and both follow-up month and activity-adjusted follow-up month equivalents.

An interactive voice response (IVR) system was used to elicit information on falls and activity in a monthly telephone call.24 We tracked all falls rather than only injurious falls. Participants who provided informed consent were registered in a Web-based system that generated these monthly telephone calls. Participants were scheduled for follow-ups each month (every 30 days) beginning 30 days after their baseline interview. As the scheduled date approached, the automated system generated 2 calls each day (1 in the morning and 1 in the evening) for up to 8 days surrounding the scheduled date until the person answered and the monthly interview was completed. If a respondent did not complete the follow-up interview in the 8-day window, the follow-up was considered missing, and a call was attempted in the succeeding month.

The automated call gathered data on whether the person had fallen in the preceding 30 days as well as information on weekly activity, hospitalizations, and emergency department use during that period. Participants were also asked whether they would like to receive a telephone call from the research team. Respondents answered questions by pushing buttons on their telephone. With respect to falls, respondents were asked the following: “Think about the last 30 days. Did you fall in the last 30 days, that is, end up on the floor or ground because you were unable to stop yourself? Press 1 for yes, 2 for no.” When participants reported a fall, the system generated an e-mail message to the research team, which followed up with a telephone interview to collect information about the fall, including when it occurred (during the day or evening or at night, after getting up from bed) and the location (at home or outside).

Given the limitations of the automated telephone interview, we relied on a simple global measure of activity. Respondents were asked to think about the preceding 7 days and to press 0 if they had not been active for at least 30 minutes on any day, 1 if they had been active on 1 day, 2 if they had been active on 2 days, and so forth up to 7 days. Active days were defined as days when participants “walked, or did exercises, or did a hobby or volunteer work that involved being on your feet for at least 30 minutes.”

The monthly calls required a mean of 2.5 minutes to complete. Most were completed on the first day of the IVR-generated monthly call. Compliance was reasonably high, with about 20% of the respondents opting out at baseline. These respondents completed the same monthly interview on the same schedule via personal telephone calls. People with hearing impairments, Spanish speakers, and people lacking touchtone telephones also received personal calls. Participants could opt out of the automated IVR system at any point during the follow-up. To assess the reliability of IVR-reported falls, we compared reports of falls among a subset of people (n = 65) who had completed an IVR assessment and an assessment involving a personal telephone call in the same month. Reports of falls agreed in 95.3% of cases.

Measures

In addition to self-reported falls and activity over the follow-up period, we collected baseline measures to assess the comparability of the HSOA and comparison groups. With respect to self-reported balance, we asked “How would you rate your balance: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” This simple self-report, drawn from the assessment battery of the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers (National Institutes of Health), is highly correlated with fall risk. In this sample, the odds of reporting a fall in the preceding 12 months were 2.86 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.2, 3.7) higher among people reporting fair or poor balance at baseline than among those reporting good, very good, or excellent balance.

Other measures included self-reported medical conditions, measures of function and symptoms (adapted from the EQ-5D to assess disabilities in basic and instrumental activities of daily living, mobility, pain, and presence of symptoms of anxiety or depression25), assessments of physical performance (the Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors [CHAMPS] physical activity measure26), falls in the preceding 12 months, self-rated balance, and memory performance (Memory Impairment Screen–Telephone [MIS]27,28).

The CHAMPS questionnaire assesses weekly frequency and duration of 40 different activities typically undertaken by older adults. We summed the number of tasks performed in the preceding week to develop a measure of total physical activity and dichotomized scores at the median (10 activities). The MIS involves registration of 4 words along with a semantic category cue. After 3 to 4 minutes of distraction with other questions, respondents are asked to recall the 4 words. Scores range from 0 to 8. We dichotomized the measure at the median of the distribution (0–6 vs 7–8) as an indicator of cognitive status. Given the geographic dispersion of the sample across 19 Pennsylvania counties, data on all measures were obtained via telephone.

Data Analyses

We calculated descriptive statistics for the HSOA and comparison groups. A Poisson regression model was used to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs. We estimated a multivariate model to assess differences in the incidence of falls between the HSOA group and the comparison group after adjustment for fall risk covariates (including age, gender, race/ethnicity, disability, memory performance, self-reported balance, falls in the preceding year, and physical activity). Covariates were dichotomized to aid in interpretation, but model results were similar when continuous measures were used. Analyses were limited to follow-up data collected from the initiation of the study in October 2010 through June 2011 so that the initial impact of the program could be assessed.

Our sample of approximately 1800 respondents allowed 80% power to detect IRRs of 0.876, 0.873, and 0.869 assuming retention rates of 90%, 85%, and 80%, respectively. These rate ratios correspond to reductions of 13% to 14% in fall incidence, which we considered reasonable for this low-intensity, population-based program.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 1833 adults 50 years or older from senior centers across 19 Pennsylvania counties from 2010 to 2011. Of the 814 individuals who completed HSOA, 9.5% completed baseline assessments before the program, 45.7% did so within 2 months after the end of the program, and 44.8% did so 2 to 4 months after the program. Because these groups did not differ with respect to baseline characteristics or fall incidence over the follow-up (results available on request), they were combined and considered a single intervention arm in assessing the effectiveness of the program. Follow-up began after completion of the baseline interview. Another 1019 older adults who did not complete the program were recruited from the same sites during the same period.

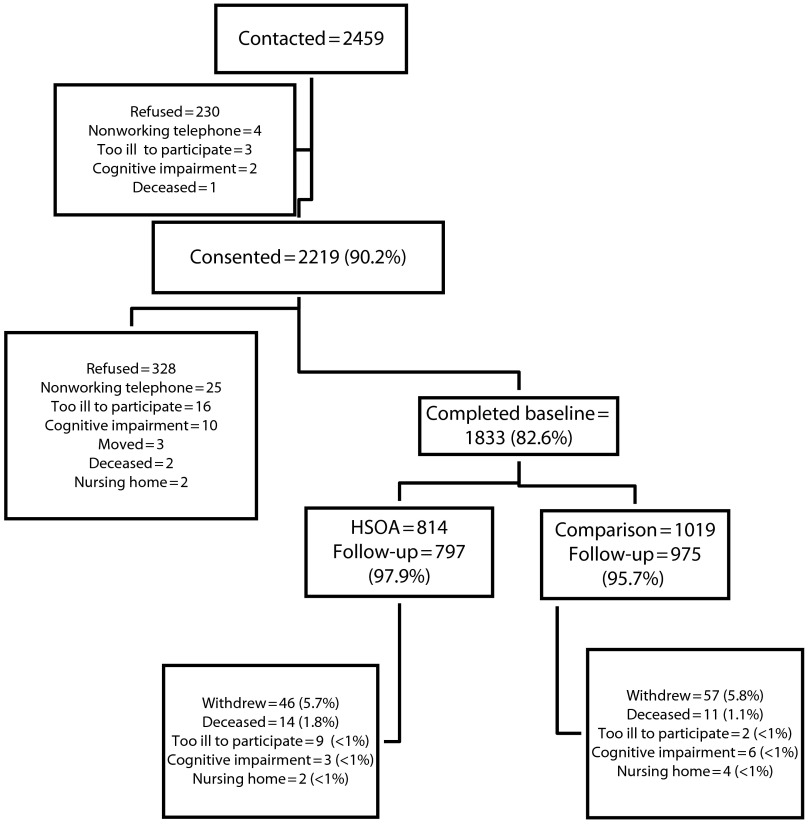

Figure 1 presents the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram for the study. The participation rate was high (90% of participants providing contact information signed a consent form, and 83% of those providing consent completed the baseline assessment). Follow-up response was also excellent (97% of the respondents completed 1 or more months of follow-up). At a median of 7.5 months of follow-up, the cohort had completed 13 227 of 16 500 possible monthly follow-up assessments, a completion rate of 80%. Attrition in the HSOA and comparison groups was similar: 5.7% in the HSOA group and 5.8% in the comparison group withdrew or were lost to follow-up. Deaths, inability to participate because of illness or cognitive impairments, and relocation outside the state were also similar between the groups.

FIGURE 1—

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials study diagram: Healthy Steps for Older Adults (HSOA) program evaluation, Pennsylvania, 2010–2011.

Comparability of Study Arms

As noted earlier, we opted against random assignment because of the walk-in nature of the program and the short interval between program announcement and enrollment. However, the groups were quite similar at baseline, as shown in Table 1. HSOA participants were about a year older (76.1 vs 75.2 years; P < .001) than comparison participants and more likely to be female (83.7% vs 75.6%; P < .001) and non-White (15.9% vs 9.6%; P < .001); however, the 2 groups did not differ on standard measures of fall risk.

TABLE 1—

Baseline Characteristics, by Group Assignment: Healthy Steps for Older Adults Program, Pennsylvania, 2010–2011

| Characteristics | Comparison Group (n = 1022), Mean (SD) or % | HSOA Group (n = 815), Mean (SD) or % |

| Age, y | 75.2 (8.6) | 76.1*** (8.4) |

| Female | 75.6 | 83.7*** |

| Education beyond high school | 38.2 | 39.2 |

| Currently married | 36.9 | 31.7 |

| Lives alone | 51.8 | 54.8 |

| White | 90.4 | 84.1*** |

| Areas of reported difficulty | ||

| Household tasks | 27.1 | 28.8 |

| Self-care | 5.6 | 6.2 |

| Pain | 60.2 | 61.5 |

| Anxiety/depression | 29.4 | 29.4 |

| Possible dementia (memory score < 4) | 5.6 | 5.0 |

| Fall indicators | ||

| Fair/poor mobility | 20.5 | 17.8 |

| Fair/poor balance | 25.7 | 27.4 |

| Fall in past 12 mo | 29.3 | 31.2 |

| Fall in past 30 d | 6.9 | 7.1 |

***P < .001.

Similar proportions of participants reported falls in the preceding year (any fall: 28.5% in the comparison group, 29.9% in the HSOA group; 2 or more falls: 12.8% in the comparison group, 11.1% in the HSOA group) and the preceding month (6.9% in the comparison group, 7.1% in the HSOA group). The same was true for self-reported fair or poor balance (25.7% in the comparison group, 27.4% in the HSOA group) and mobility status (20.5% in the comparison group, 17.8% in the HSOA group). Disability levels in the 2 groups did not differ (27.1% of participants in the comparison group and 28.8% of participants in the HSOA group experienced difficulties in instrumental activities of daily living, and 5.6% of those in the comparison group and 6.2% of those in the HSOA group experienced difficulties in basic activities). Similar proportions in the 2 groups demonstrated poor memory (5.6% in the comparison group, 5.0% in the HSOA group) and reported pain or mental health symptoms.

Follow-up intervals in the 2 groups were similar (7.45 months in the comparison group, 7.49 months in the HSOA group), and the groups did not differ in mean number of active days over a weekly period (5.15 days in the comparison group, 5.23 days in the HSOA group) or activity-adjusted months (5.48 months in the comparison group, 5.60 months in the HSOA group). Likewise, the percentages of participants in the 2 groups reporting a fall over the follow-up period were similar (32.1% in the comparison group, 31.2% in the HSOA group). Nearly 13 percent of participants in the comparison group reported 2 or more months with a fall, as compared with 9.3% of participants in the HSOA group.

Delivery of the Intervention

During the baseline interview, participants were asked about their HSOA assessment and recommendations by staff to see physicians or complete home safety checks; 84.1% reported that they were told how well they did on the mobility and balance screening. Among participants who were told by staff members that they were at a high risk of falls (21.3%), 21.5% reported that they saw a physician to discuss their HSOA assessment. Virtually all HSOA participants (92.1%) reported that they were given a home safety checklist; 78.6% reported use of the checklist to conduct a home safety assessment, and 32% reported a change in their home environment as a result of this effort.

HSOA participants reported increases in confidence in their ability to prevent falls as a result of the program (88.3%). When asked about changes in physical activity as a consequence of the program, 25.5% reported an increase and only 2% a reduction; the remainder reported no change.

Effect on Incidence of Falls

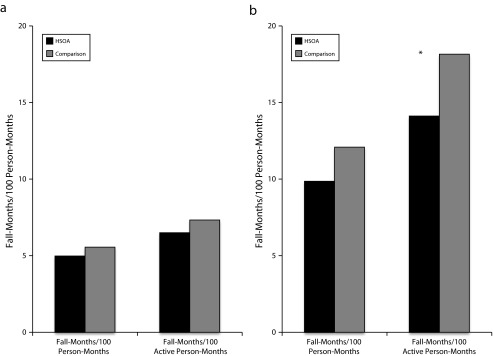

Differences in outcomes between the groups, stratified by balance category, are shown in Figure 2. The incidence of falls was 2 to 3 times higher in the group reporting fair or poor balance than in the group reporting good, very good, or excellent balance. Among people reporting fair or poor balance, activity-adjusted fall incidence rates were approximately 14 fall-months per 100 person-months in the HSOA group and 18 fall-months per 100 person-months in the comparison group (P = .015). Differences were smaller and nonsignificant among respondents reporting better balance but still favored the HSOA group.

FIGURE 2—

Comparison of the incidence of falls, by incidence rate ratios, in the program and comparison groups for self-reported balance categories (a) good, very good, or excellent, and (b) fair or poor: Healthy Steps for Older Adults Program (HSOA), Pennsylvania, 2010–2011.

Note. The median was 7.5 months of follow-up.

*P = .015.

The results of the multivariate analyses (Table 2) showed that HSOA participants had a reduced incidence of falls, expressed in both total months of follow-up and follow-up months adjusted for activity levels. The models adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and fall risk factors, including self-reported balance, falls in the preceding year, and self-reported physical activity. Incidence rate ratios were lower in the HSOA group than in the comparison group for both total (IRR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.72, 0.96) and activity-adjusted (IRR = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.70, 0.93) months of follow-up. Other significant predictors of fall incidence included absence of disabilities in basic and instrumental activities (activity-adjusted outcome; IRR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.71, 0.96), poorer memory (IRRs = 1.23–1.28), better self-reported balance (IRRs = 0.58–0.62), and non-White race/ethnicity (IRRs = 1.29–1.43). Participation in HSOA was associated with approximately a 17% reduction in the rate of falls after adjustment for fall risk factors.

TABLE 2—

Multivariate Assessment of Fall Incidence Rate Ratios, by Type of Follow-Up Measure: Healthy Steps for Older Adults Program (HSOA), Pennsylvania, 2010–2011

| Variables | Person-Months of Follow-Up, IRR (95% CI) | Active Person-Months of Follow-Up, IRR (95% CI) |

| Age, y | ||

| ≤ 75 | 0.96 (0.84, 1.12) | 0.96 (0.83, 1.11) |

| > 75 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 0.94 (0.80, 1.11) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.13) |

| Male (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-White | 1.28* (1.05, 1.57) | 1.41*** (1.15, 1.73) |

| White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Disability status | ||

| No disability | 0.89 (0.76, 1.03) | 0.83* (0.71, 0.96) |

| Any disability (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Memory score | ||

| < 7 | 1.23** (1.07, 1.43) | 1.28** (1.11, 1.48) |

| ≥ 7 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-reported balance | ||

| Excellent/very good/good | 0.62*** (0.53, 0.73) | 0.58*** (0.50, 0.68) |

| Fair/poor (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-reported fall in y before baseline | ||

| No | 0.59*** (0.51, 0.68) | 0.58*** (0.50, 0.68) |

| Yes (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Self-reported physical activity at baseline, CHAMPS | ||

| ≤ 10 | 0.99 (0.86, 1.15) | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) |

| > 10 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Group assignment | ||

| HSOA | 0.83* (0.72, 0.96) | 0.81** (0.70, 0.93) |

| Comparison (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note. CHAMPS = Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors; CI = confidence interval; HSOA = Healthy Steps for Older Adults; IRR = incident rate ratio.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

We repeated the analyses using the number of people who reported a fall rather than total number of falls in calculating incidence rates. In these models, HSOA status was associated with a reduced risk of falls, but differences did not achieve significance. IRRs were 0.94 (95% CI = 0.79, 1.11) for total months of follow-up and 0.92 (95% CI = 0.77, 1.09) for follow-up adjusted for activity level (i.e., 6% to 8% fewer people falling in the HSOA group than in the comparison group).

Effect on Types of Falls

Of people reporting a fall over the follow-up period, 74% (416 of 562) completed an additional interview in the month of the fall to elicit the circumstances. Among those reporting falls, falls during the night while getting up from bed were less frequent in the HSOA group; however, between-group differences did not achieve significance (11% vs 15.7%; P = .17). Falls outdoors were less likely in the HSOA group, but again differences were not significant (40.3% vs 45.2%; P = .32).

DISCUSSION

Older adults who completed the HSOA program, a statewide primary prevention effort focusing on falls, had a significantly lower incidence of falls than a similar comparison group. In multivariate models, completion of HSOA was associated with a lower rate of falls (IRR = 0.83, a significant reduction of about 17%), as well as a reduced percentage of falls (with 6%–8% fewer people falling than in the comparison group, although this difference was not significant), in a median of 7.5 months of follow-up after the baseline assessment. This reduction in rate of falls is similar to estimates derived from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials focusing on fall prevention (relative risk = 0.85).29

Because HSOA uses the distributed network of senior center sites operated by county Area Agencies on Aging, it can be offered to large numbers of older adults. Its use of simple performance measures that can be administered by lay volunteers keeps costs low. Standardized data collection allows appropriate program audit and management across sites and counties. In 2010–2011, the Pennsylvania Department of Aging reimbursed sites $70 per person for delivering the program and allocated $1.2 million to the program as a whole. With this state commitment, HSOA is a scalable, effective platform for mass fall risk screening of older adults. It relies on the existing aging service infrastructure and includes identification of older adults at high risk of falls, referral of high-risk older adults to personal physicians for fall assessments, local resources for home safety, and education. The program provides a booklet with exercises and demonstrations of balance and strength exercises to prevent falls but does not involve exercise classes.

The specific aspects of the program that are responsible for the reduction in falls require further analysis. Only 21.5% of older adults informed that they were at a high risk of falls followed up with physicians. By contrast, more than three quarters of HSOA participants conducted home safety assessments, and a third reduced home hazards. Simply informing older adults of their high-risk status and heightening their sensitivity to situations involving a risk of falling may lead to reductions in falls. Some evidence for this interpretation can be seen in the greater benefit of the program for people with self-rated fair or poor balance. Further analyses of the experiences of this cohort will be required to identify mechanisms responsible for reductions in fall incidence.

The 17% reduction in fall incidence achieved by HSOA is lower than that achieved by individually tailored multicomponent interventions such as Yale FICSIT (Frailty and Injuries Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques), which led to a 35% reduction,10 but higher than that observed in mass provider outreach and education efforts, which in one study reduced fall incidence by 9%.30 As noted, the program offered the most benefit to people reporting fair or poor balance. Among these older adults, completion of HSOA was associated with 4 fewer months with falls per 100 active-month equivalents, that is, 14 versus 18 months with falls. This difference amounts to a reduction of 0.48 falls per person-year, or 1 less fall per person every 2 years. The potential for the program to reduce falls in Pennsylvania is high given the state’s population of approximately 4.5 million individuals older than 50 years. By the same token, the reach of HSOA is still small, with only 32 000 people having completed the program in its first 6 years of operation.

HSOA is a hybrid program combining education on fall risk, medical care referrals, and referrals to social service agencies for home safety assessments, all offered in the setting of ongoing contact with participants. For these reasons, it is not strictly comparable to fall education programs or one-time clinical referral efforts, which have not been successful in preventing falls. Also, it is designed to promote fall prevention in the community-dwelling elderly population as a whole, not only those at high risk, which again makes comparisons with other efforts difficult. Although the results of our study support this approach to primary prevention of falls, a randomized controlled trial of HSOA remains the definitive test. Further evaluation and dissemination efforts would also be valuable. Program enhancements, such as referrals for medication therapy management or notification of physicians when participants perform poorly on mobility measures, may also be useful.

Our results should be interpreted in light of the limitations of the study design. Most centrally, assignment to the HSOA and comparison groups was not random. The comparison group included people who were receiving services at the same senior centers but did not participate in the fall prevention program. However, all of the participants completed the same standardized baseline assessments and monthly follow-ups, and the 2 groups were similar at baseline with respect to fall risk and medical status. Interviewers conducting baseline assessments were unaware of participants’ group assignment status, and high compliance with the automated monthly falls assessment reduced potential interviewer bias. Attrition was not differential across groups and was uniformly low. Although baseline assessment data were obtained after the intervention for the majority of HSOA participants, the timing of the baseline assessment was not associated with baseline characteristics or fall incidence over the follow-up period.

Because participants were drawn from across Pennsylvania, we were limited to telephone contact with participants and brief assessments of their monthly physical activity. We were also unable to conduct clinical assessments or performance tests. We used self-reports and a telephone-based memory assessment as an alternative. The strong association between self-reported balance and incidence of falls suggests that self-reports were a reasonable proxy for balance assessments.

Finally, ascertainment of falls was also based on self-reported information. We attempted to overcome biases in self-reports (such as telescoping or omission of minor falls) by using an automated fall registration system to ascertain the number of falls occurring each month. Compliance with monthly assessments was high, suggesting that a telephone-based IVR system (supplemented by personal calls) is a reasonable way to ascertain falls or other recurrent endpoints. Finally, recognizing that older adults at a high risk of falls may reduce their activity in an effort to lower their risk, we calculated fall incidence in 2 ways, total follow-up months and an activity-adjusted month equivalent. Multivariate analyses showed the effectiveness of HSOA with respect to both incidence measures.

To conclude, use of the existing aging service infrastructure in primary prevention of falls is feasible and associated with significant reductions in the rate of falls, especially among older adults who report fair or poor balance. The aging service network can be an effective platform for delivery of prevention services and should be considered part of the public health armamentarium.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement DP002657 and grant U48 DP001918) and the National Institutes of Health (grant P30 AG024827).

Note. The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1. National Council on Aging. Standing together to prevent falls. Available at: http://www.ncoa.org/calendar-of-events/webinars/standing-together-to-prevent.html. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- 3.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming J, Brayne C. Inability to get up after falling, subsequent time on floor, and summoning help: prospective cohort study in people over 90. BMJ. 2008;337:a2227. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King MB. Falls. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S, editors. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2009. pp. 659–670. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(18):1279–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710303371806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tinetti ME. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):42–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp020719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morley JE. A fall is a major event in the life of an older person. J Gerontol A Biol Med Sci. 2002;57(8):M492–M495. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.8.m492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. The effect of falls and fall injuries on functioning in community-dwelling older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Med Sci. 1998;53(2):M112–M119. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.2.m112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(13):821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClure R, Turner C, Peel N et al. Population-based interventions for the prevention of fall-related injuries in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD004441. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004441.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gates S, Lamb SE, Fisher JD, Cooke MW, Carter YH. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7636):130–133. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens JA, Sogolo ED. Preventing Falls: What Works? A CDC Compendium of Effective Community-Based Interventions From Around the World. 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing Falls: How to Develop Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs for Older Adults. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moyer VA. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):197–204. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society. 2010 AGS/BGS Clinical Practice Guideline: Prevention of Falls in Older Persons. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Health Research for Action. Pennsylvania’s Healthy Steps for Older Adults. Available at: http://www.healthresearchforaction.org/pennsylvanias-healthy-steps-older-adults. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- 19. Pennsylvania Department of Aging. Healthy Steps for Older Adults fall prevention initiative. Available at: http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/health_and_nutrition/17886/primetime_health/616002. Accessed January 15, 2014.

- 20.Stevens JA, Phelan EA. Development of STEADI: a fall prevention resource for health care providers. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(5):706–714. doi: 10.1177/1524839912463576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wijlhuizen GJ, Chorus AMJ, Hopman-Rock M. The FARE: a new way to express falls risk among older persons including physical activity as a measure of exposure. Prev Med. 2010;50(3):143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wijlhuizen GJ, de Jong R, Hopman-Rock M. Older persons afraid of falling reduce physical activity to prevent outdoor falls. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laybourne AH, Biggs S, Martin FC et al. Falls, exercise interventions, and reduced falls rate: always in the patient’s interest? Age Ageing. 2008;37(1):10–13. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wijlhuizen GJ, Hopman-Rock M, Knook DL et al. Automatic registration of falls and other accidents among community-dwelling older people: feasibility and reliability of the telephone inquiry system. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2006;13(1):58–60. doi: 10.1080/15660970500036937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kind P, Dolan P, Gudex C, Williams A. Variations in population health status: results from a United Kingdom national questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;316(7133):736–741. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7133.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(7):1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buschke H, Kuslansky G, Katz M et al. Screening for dementia with the Memory Impairment Screen. Neurology. 1999;52(2):231–238. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Kuslansky G et al. Screening for dementia by telephone using the Memory Impairment Screen. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1382–1390. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi M, Hector M. Effectiveness of intervention programs in preventing falls: a systematic review of recent 10 years and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(2):e13–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, King M et al. Effect of dissemination of evidence in reducing injuries from falls. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):252–261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]