Abstract

Background

Systemic in vivo gene therapy has resulted in widespread correction in animal models when treated at birth. However, limited improvement was observed in postnatally treated animals with mainly targeting to the liver and bone marrow. It has been shown that an O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase variant (MGMTP140K) mediated in vivo selection of transduced hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) in animals.

Methods

We investigated the feasibility of MGMTP140K-mediated selection in primary hepatocytes from a mouse model of mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I) in vitro using lentiviral vectors.

Results

We found that multiple cycles of O6-benzylguanine (BG)/1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) treatment at a dosage effective for ex vivo HSC selection led to a two-fold increase of MGMT-expressing primary hepatocytes under culture conditions with minimum cell expansion. This enrichment level was comparable to that obtained after selection at a hepatic maximal tolerated dose of BCNU. Similar levels of increase were observed regardless of initial transduction frequency, or the position of MGMT (upstream or downstream of internal ribosome entry site) in the vector constructs. In addition, we found that elongation factor 1α promoter was superior to the long-terminal repeat promoter from spleen focus-forming virus with regard to transgene expression in primary hepatocytes. Moreover, the levels of therapeutic transgene expression in transduced, enzyme-deficient hepatocytes directly correlated with the doses of BCNU, leading to metabolic correction in transduced hepatocytes and metabolic cross-correction in neighbouring non-transduced MPS I cells.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that MGMTP140K expression confers successful protection/selection in primary hepatocytes, and provide ‘proof of concept’ to the prospect of MGMTP140K-mediated co-selection for hepatocytes and HSC using BG/BCNU treatment.

Keywords: ex-vivo selection, lentivirus vector, lysosomal storage diseases, metabolic cross correction, methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase, primary hepatocytes

Introduction

Lysosomal storage diseases (LSD) is a group of inherited disorders with a collective incidence of approximately one in 7000 live births [1]. Mucopolysaccharidosis type I (MPS I) is one of the most common LSD, which is caused by the deficiency of α-l-iduronidase (IDUA) and consequent systemic accumulation of the unprocessed glycosaminoglycans (GAG) [2]. The clinical features in patients with MPS I are associated with progressive systemic tissue pathology and multi-organ abnormalities. Early studies of MPS I have provided key insights into the metabolic cross-correction that results from intercellular enzyme transfer (i.e. enzyme release and re-uptake by receptor-mediated endocytosis and/or direct cell-to-cell contact) [3]. This phenomenon has provided the basis of treating a multi-organ systemic disease with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation (BMT). BMT is effective in prolonging life and ameliorating many of the clinical manifestations, but minimal or no response has been observed in reversing pre-existing central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities or musculoskeletal dysfunctions [4-7]. Recently, a study performed on mice with another lysosomal storage disorder, metachromatic leukodystrophy showed that gene marked HSCs (overexpressing relatively high levels of the aryl sulfatase I enzyme) are far more efficient at reversing the pre-existing CNS pathology than a bone marrow transplant using normal HSCs [8]. Results such as these could only be conceivably achieved in humans if a selection strategy was used in addition to gene transfer. The benefit of in vivo selection has been demonstrated by the recent success of ex vivo HSC gene therapy clinical trials for children with immunodeficiency [9-11]. The genetically corrected cells likely had a selective advantage over the uncorrected cells, which had compensated for the relatively low frequencies of transduced and successfully engrafted HSCs that were normally observed in all other ex vivo HSC-mediated gene therapy clinical trials. However, this selective advantage is not available in most of other diseases.

O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) is an alkyltransferase that functions to repair cellular DNA damage at the O6 position of guanine. In vitro studies have demonstrated the utility of a MGMT variant (MGMTP140K), which is resistant to the inhibition by O6-benzylguanine (BG), for the enrichment of transduced HSCs or their progeny [12-16]. This was then further advanced and confirmed by successful in vivo selection in mice [13,17,18] and large animal models [19,20] following time- and dose-intensive treatment using different O(6)-alkylating drugs such as 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) or Temozolomide (TMZ). Both BCNU and TMZ have shown variable degrees of effects in non-hematologic organs such as liver, lung and CNS. However, the potential selective effect of MGMTP140K on other organ systems has not been evaluated.

We and others have demonstrated the feasibility of in vivo gene transfer into murine adult bone marrow HSC and hepatocytes by a single intravenous injection of a lentivirus vector (LV) [21,22], or by a localized intravascular injection for hepatic transduction [23] and intrafemoral injection for bone marrow stem cell gene transfer [24]. However, the in vivo transduction efficiencies into adult mice are generally low. Despite the well-documented MGMTP140K-mediated HSC selection, it is unclear whether hepatocytes are sensitive to BG/BCNU treatment, and whether there is a possibility of co-selection of HSC and hepatocytes.

In the present study, we evaluated the potential of MGMT-mediated in vitro selection in primary hepatocytes of murine MPS I model. We showed that MGMTP140K expression conferred resistance to BG/BCNU in primary hepatocytes, leading to a two-fold increase in MGMT-expressing cells with multiple cycles of BG/BCNU treatment at a dosage effective for ex vivo HSC selection. This enrichment level was comparable to those obtained after selection at a hepatic maximal tolerated dose (MTD). Metabolic correction and cross-correction were confirmed in post-selected hepatocytes. These results warrant the need for further evaluation of hepatocyte-mediated in vivo selection, which, if successful, may also benefit gene therapy strategy for other systemic or liver-targeted diseases.

Materials and methods

Reagents and chemicals

The murine AML12 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The human MGMTP140K cDNA was obtained as a gift from Dr David Williams (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA). The packaging helper plasmids p2NRF and pEF1.Rev were kind gifts from Dr Tal Kafri (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA). Unless otherwise stated, all liquid media, serum or routine tissue-culture reagents were purchased from Gibco BRL Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA), and all chemicals were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA).

Plasmid construction and lentiviral vector production

Four bicistronic SIN-LVs were constructed by inserting elongation factor 1α promoter (EF1α) (GenBank AF403737, 1–1192) or long-terminal repeat (LTR) promoter/enhancer from Friend spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) [25] into pLV-TW [24] at the AfeI restriction sites (between cppt and WPRE). The human IDUA cDNA was generated by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction amplification using cytoplasmic RNA isolated from normal peripheral blood leukocytes as described previously [26]. The expression cassette MGMTP140K-ires-GFP (MiG) or IDUA-ires-MGMTP140K (IiM) was inserted into the HpaI site. The transfer LVs were packaged by co-transfection of 293T cells with three helper plasmids: p2NRF for gag-pol, pEF1.Rev for Rev and pMD.G for VSVG env function as previously described [24]. Five 12-h harvests were performed starting from 36 h after co-transfection, filtered through 0.45 μm-pore-size cellulose acetate filters, and ultracentrifuged twice at 21,000 r.p.m. for 120 min with 1500–2000-fold concentration. The potency of viral stocks (typical 108–109 TU/ml) was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis for GFP+ or MGMT+ percentage on 293T cells exposed to serial LV dilutions using FACS can flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA,USA).

Cell line maintenance

The AML12 cells were maintained in D-MEM/F-12 medium (ATCC) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5 μg/ml transferring, 5 ng/ml selenium, 5 μg/ml insulin, 40 ng/ml dexamethasone and antibiotics. Cells were subcultured 1 : 4–1 : 8 using 0.25% (w/v) Trypsin-EDTA, and aliquots of the same passages were used for all experiments. We cultured 293T cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamine and antibiotics. The cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, and were routinely tested for Mycoplasma infection.

Murine primary hepatocyte isolation and culture

The mouse strains C57/BL6 and B6.129-iduatm1Clk (004068, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were in-house bred in a pathogen-free facility (with micro-isolator). All animal handling and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Primary hepatocytes were isolated by two-step collagenase perfusion as described with modifications [27]. In brief, the portal vein from anaesthetized (pentobarbital, 60 mg/kg) mice (6–9 weeks old) was cannulated and perfused with PBS-EDTA containing glucose (20 mM) for 10 min, followed with PBS-collagenase solution containing 0.1 M Ca2+ and 40 mg/100 ml collagenase for additional 10 min. Cells were dispersed into 1 : 1 PBS-collagenase solution : William’s E medium with 10% FBS, followed by filtration through 100 – μm nylon cell strainers (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The hepatocytes were further purified from nonparenchymal cells by low speed centrifugation at 500 r.p.m. and 4 °C for 2 min. The loose cell pellet was resuspended in William’s E medium supplemented with 10% FBS and double dosage of antibiotics (200 IU/ml penicillin, 200 μg/ml streptomycin). Viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion with consistent yield ranging from 3–6 × 106 cells/g of liver, and viability >90%.

The isolated hepatocytes were resuspended in William’s E medium supplemented with 10% FBS, insulin (10 nM), dexamethasone (20 nM), hHGF (10 ng/ml) and antibiotics, and seeded in 24-well collagen I-coated plates (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) at a density of 2 × 105 viable cells/well. After 3 h of inoculation, medium was changed to remove non-adherent and dead cells.

Cell transduction and selection

After overnight culture, hepatocytes were washed once with PBS, and transduced for 24 h with various amounts of concentrated vector at the presence of protamine sulfate (10 ng/ml) and with or without vitamin E (50 μM). After an additional 1.5 days of culture, BG/BCNU selection was performed with 5, 20 or 80 μM of BG for 1 h at 37 °C, and the addition of various amount of BCNU (Bristol Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ, USA) for 2 h at 37 °C (protected from light). AML12 cells were transduced with TW-EMiG at the presence of 10 ng/ml protamine sulfate, and were selected 3 days post transduction with treatment of BG (20 or 80 μM) for 1 h and various amounts of BCNU for 2 h. Cells were subcultured for two to three passages and analysed by FACS using 7-aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) to eliminate dead cells.

Identification of viable and transduced hepatocytes by flow cytometry

To accurately gate viable cells by FACS analysis, hepatocytes were stained using LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. In brief, hepatocytes were harvested with 0.25% (w/v) Trypsin-EDTA and washed once in PBS with 2% FBS. After resuspended at a density of 4 × 105/ml, 0.5 μl of freshly reconstituted fluorescent reactive dye was added for a 30-min incubation on ice. For hepatocytes transduced with TW-EIiM, we further used Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) to permeate cells for intracellular MGMT staining according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation for 30 min at 4 °C with a 1 : 400 dilution of murine anti-human MGMT monoclonal antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA), cells were further stained with 1 : 30 dilution of a goat anti-mouse FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (BD Bioscience). FACScan was utilized to gate out viable cells with FL-2 and quantify GFP+ or MGMT+ cells with FL-1 channels.

In situ immunohistostaining for MGMT and immunochemical staining for lysosomal secretion

Murine hepatocytes were seeded and grown on glass cover slips that were pre-coated with l-poly lysine (Travigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). After overnight transduction and an additional 2 days of culture, cells were incubated with 75 nM LysoTracker Red (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. We then fixed and permeated cells in situ with Cytofix/Cytoperm, followed by immunostaining with 1 : 400 dilution of murine anti-human MGMT monoclonal antibody. After three washing steps with Perm/Wash buffer, a goat anti-mouse FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 100 dilution) was added for 30 min at room temperature. The cover slips with cells were then mounted invertedly using Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and observed using an Olympus inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

IDUA enzyme assay

The catalytic activity of IDUA was measured with a fluorometric enzyme assay as previously described with modifications [26]. Cell pellets were homogenized in lysis buffer (0.4 m NaFormate buffer with 0.3% Triton X-100 and pH 3.2) using an Ultrasonic Processor (Sonics, Newtown, CT, USA). Aliquots of cleared lysate or culture medium was incubated with 2.5 mm fluorogenic substrate, 4-methylumbelliferyl (4MU) α-l-idopyranosiduronic acid sodium salt (Toronto Research Chemicals Inc., North York, ON, Canada), together with no-sample blank controls in parallel. Protein concentration was measured by Coomassie blue dye-binding assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the release of 1 nmol of 4MU in a 1-h reaction at 37 °C. The intracellular IDUA specific activity was calculated as U/mg protein, and extracellular IDUA activity as U/ml medium. All samples were assayed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative assays were performed in duplicate or triplicate from at least two individual experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tailed Student t-tests. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

MGMTP140K-mediated selective growth of transduced murine AML12 hepatic cell line

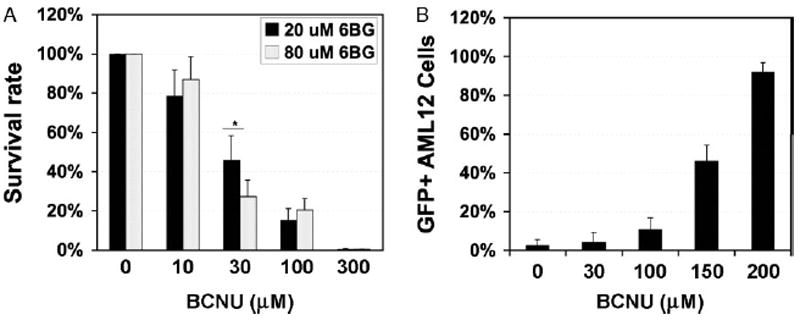

We first studied MGMTP140K-mediated selection in a non-tumorigenic murine hepatic cell line AML12 and evaluated the survival rate of AML12 using different dose combinations of BG and BCNU (Figure 1A). Significant cell death was observed in un-transduced cells treated with 30 μM BCNU in response to sensitization using increasing doses of BG. This dose effectively selects murine and human hematopoietic progenitor cells in colony forming unit assays [17]. Less than 15% or 0.5% cells survived when the BCNU dosage increased to 100 μM or 300 μM, respectively. Changing the dose of BG (to inhibit the endogenous MGMT) did not have a significant effect on selection by various amounts of BCNU, except at 30 μM. This suggested that 20 μM of BG was not sufficient to sensitize AML12 for BCNU treatment at 30 μM or less.

Figure 1.

MGMTP140K-mediated selection in murine hepatic AML12 cells. (A) Dosage response survival of AML12 cells. Cells were treated with 20 or 80 μM BG for 1 h, followed by incubation with BCNU for 2 h, and scored 3 days post selection for viable cells by Trypan-blue staining. (B) Cells were transduced at a MOI of 0.2 with TW-EMiG, followed by selection treatment 3 days later with 20 μM BG and a variable concentration of BCNU. GFP+ cells were evaluated 2 weeks after treatment by FACS analysis using 7AAD to identify viable cell population. Each point represents data derived from two separate experiments with each in triplicate. EMiG, EF1α promoter-MGMTP140K-ires-GFP; ires, internal ribosome entry site. p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test

We then transduced AML12 cells with a SIN-TW-EMiG (EF1α-MGMTP140K-ires-GFP) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2, and applied one run of selection treatment (Figure 1B). After selection treatment and 2 weeks of culture expansion, GFP+ cells in viable cell population were enriched from an initial frequency of 3% to 92% in response to increasing doses of BCNU (0–200 μM). These data indicated that the expression of MGMTP140K was effective in protecting a murine hepatic cell line from combined BG and BCNU treatment.

Survival assessment in primary hepatocytes

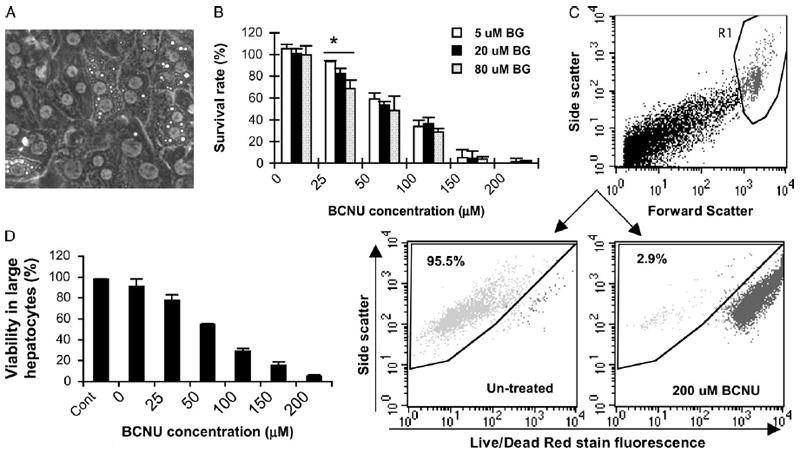

To establish a primary hepatocyte culture with minimum cell expansion (to mimic in vivo adult hepatocyte growth), we inoculated cells at relatively high density (2 × 105 in collagen-coated 24-well plates) with minimum cytokine (HGF) supplement (required to maintain viability, data not shown). Typical clutches of cuboidal cells with hepatocyte morphology were observed at early stage of culture (Figure 2A). After 6 days of ex vivo manipulation, we found only a slight increase in viable cell numbers (mean of 1.1-fold) with high viability (91 ± 5%) as determined by Trypan-blue staining. Interestingly, survival curves showed that primary hepatocytes were responsive to sensitization mediated by increasing doses of BG (5–80 μM) when the dose of BCNU was at 25 μM, but not at any of the higher BCNU doses (Figure 2B). The in vitro maximal tolerated dosage in primary hepatocytes was 150 μM BCNU with 94% of cells eliminated, which was approximately five-fold higher than that in murine hematopoietic progenitors.

Figure 2.

Survival assessment of primary hepatocytes after drug treatment. (A) Representative primary hepatocytes at day 3 of culture with typical cuboidal morphology. (B) Dose–response survival curves in hepatocyte culture. Three days after plating, hepatocytes were treated with 5 μM, 20 μM or 80 μM O6-BG for 1 h, followed by incubation with various concentrations of BCNU for 2 h. Survival rate was calculated as a percentage of total viable cells against untreated hepatocyte culture. (C) Representative dot-plots for viable hepatocyte gating. The FL-2 channel was used to detect Live/Dead red staining. (D) Viability change in large hepatocytes as determined by FACS analysis 3 days after treatment with 20 μM BG and a variable concentration of BCNU. *p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test

The primary hepatocyte isolation procedure employed in the present study normally results in a heterogeneous population with 5–10% of nonparenchymal cells [28]. In addition, hepatocytes often have multiple nuclei, which makes it challenging to identify the viable cell population (crucial to a selection study) by the commonly used staining with 7AAD or propidium iodide. To quantify viable hepatocytes using flow cytometry, we gated on cells with the largest size cells (characteristic for hepatocytes) based on forward- and side-scatter, and then analysed only viable cells in this population by using a Live/Dead Red dye that reacts with cellular amines (Figure 2C). Using this method, we found that the viabilities in large hepatocytes reduced significantly even at the lowest BCNU dosage tested, which was also confirmed by Trypan-blue staining (Figure 2D). Thus, we were able to utilize flow cytometry to quantify transduction efficiency more objectively, as well as to assess GFP expression levels, compared to commonly used fluorescence microscopy for scoring transductants in primary hepatocytes [29].

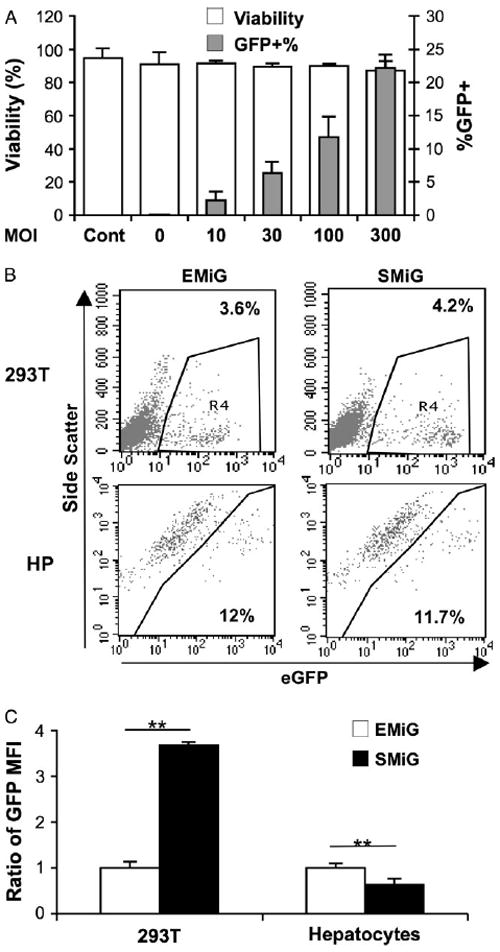

Evaluation of transduction efficiency and transgene expression in hepatocytes

We next determined the transducibility of primary hepatocytes with two marking vectors using two different promoters to express the same cassette (Figure 3). Unlike polybrene, which was reported to cause high mortality in rat hepatocytes after 18 h of plating [29], we found no difference in viability and total viable cell numbers in mouse hepatocytes mock transduced with (MOI = 0) or without (Cont) protamine sulfate (Figure 3A). A high MOI of 300 also was not toxic to hepatocytes under these conditions. The results from four experiments showed that the frequency of GFP+ large viable hepatocytes increased steadily with increasing MOI, starting from 2.2 ± 1.3% to 22.2 ± 2.0% at a MOI of 10–300. The addition of vitamin E, which was reported to increase transduction efficiency in primary human and rat hepatocytes [30], did not significantly affect transgene frequency in murine hepatocytes under this conditions (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Transduction and transgene expression in primary hepatocytes using marking vector TW-EMIG and TW-SMiG. (A) Viabilities and transduction efficiencies in large hepatocytes after 6 days of ex vivo culture and LV transduction as determined by FACS analysis. Cells were transduced with TW-EMiG (two experiments) or TW-SMiG (two experiments) 18 h after plating at an MOI of 0, 10, 30, 100 and 300, and GFP+ viable large hepatocytes were scored 4–5 days after transduction. Each point represents the mean of four experiments with two vectors in duplicate wells. (B) Representative FACS plots, showing the variation of GFP expression between TW-EMIG and TW-SMiG in 293T or hepatocytes (HP) with similar transduction efficiency. (C) Relative comparison of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) with EMiG transduced cells as 1. The transduction efficiencies were similar (2–6%) in 293T cells transduced with both vectors. Data in hepatocytes were derived from three transduction experiments using both vectors in parallel with similarly transduction frequency (9–14%). **p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test

To identify the appropriate promoter for hepatic transgene expression, we compared a strong LTR promoter from SFFV [25] with a house keeping gene promoter EF1α for co-expression of MGMTP140K and GFP in 293T cells and primary hepatocytes (Figures 3B and 3C). We found that SF promoter introduced significantly higher GFP expression (3.7-fold) than EF1α promoter in human kidney 293T cells (p < 0.01) (Figure 3C). However, the results from three individual experiments showed that expression from EF1α promoter was significantly higher than that from SF promoter when transduced under the same MOI (1.6-fold, p < 0.01). These data suggested that EF1α promoter was slightly superior to the LTR promoter from SFFV with regard to transgene expression in primary hepatocytes.

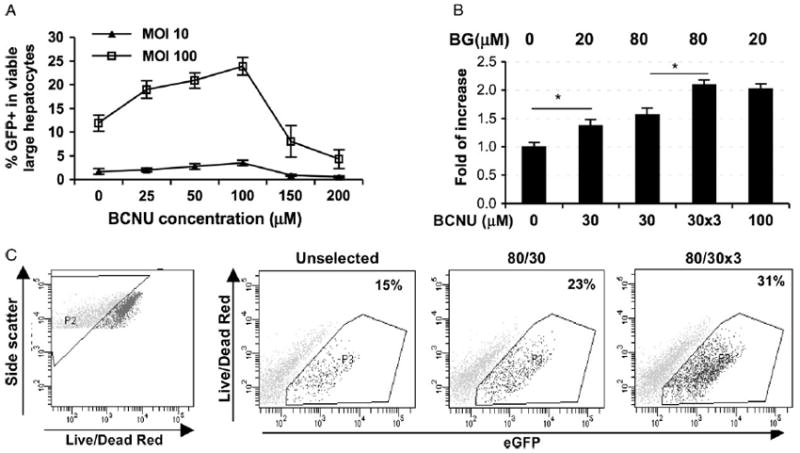

Transgene expression of MGMTP140 k conferred significant resistance to BG/BCNU

To evaluate whether expression of MGMTP140K could protect hepatocytes against BG sensitization to BCNU, we transduced primary hepatocytes with a single dose of TW-EMiG at an MOI of 10 and 100, and followed this with one cycle of BG/BCNU treatment at various concentrations 2 days post transduction (Figure 4A). The results from both transduction groups showed enrichment of transduced hepatocytes, from 1.7% to 3.5% and 12% to 24%, respectively, in a dose-dependent manner from 0–100 μM BCNU which was the hepatic MTD for post-transduction selection. Thus, regardless of the initial transduction efficiency, a two-fold enrichment of transduced cells was observed after 100 μM of BCNU treatment under this culture/selection condition. At higher doses of BCNU (150–200 μM), MGMTP140K expression levels were not sufficient for the repair of BCNU-mediated DNA damage (Figure 4A). These data suggest that hepatic expression of MGMTP140K could provide selective advantage in primary hepatocytes against BG/BCNU-induced DNA damage.

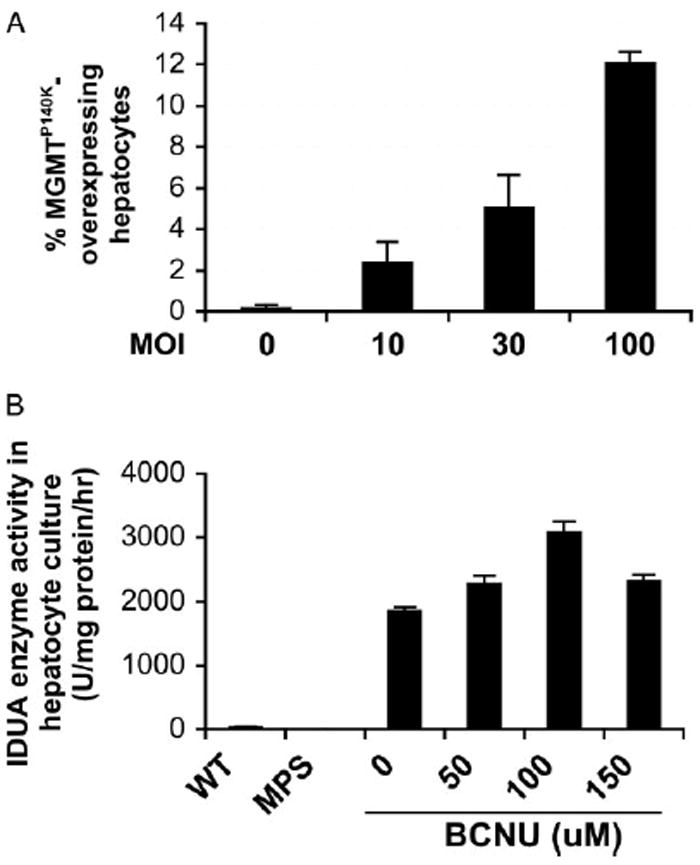

Figure 4.

Enrichment of MGMTP140K-expressing hepatocytes after one (A) or three cycles (B) of BG/BCNU selection. Eighteen hours after plating, the cells were exposed to TW-EMiG at various MOI for 24 h. (A) Selection treatment was performed with one cycle of 20 μM BG (for 1 h) and 0–200 μM BCNU (for 2 h) 2 days after transduction, and GFP+ cells were scored in the large and viable subpopulation 3 days later. (B) Three cycles of 30 μM BCNU (i.e. 30 × 3) (with 80 μM BG pretreatment) were performed on days 3, 5 and 7, together with other one-cycle treatment groups performed on day 3 post-transduction. Cells were harvested on day 9 post transduction. Three individual experiments were conducted with all groups included. Each experiment was performed in triplicate wells. *p < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. (C) Representative FACS analysis for viable, transduced and selected hepatocytes. Cells were stained with LIVE/DEAD red and analysed for GFP+ (FL-1) in viable (gated as P2) large hepatocytes

Although transduced primary hepatocytes tolerated 100 μM BCNU in vitro, this is not a feasible dose that can be given in vivo. We therefore applied three rounds of selection at the doses routinely used for ex vivo hematopoietic progenitor selection to evaluate the physiological relevance of this approach. We determined the fold increase of transduced hepatocytes by increasing BG dosage and by multiple cycles of 30 μM BCNU treatment in three independent experiments (Figures 4B and 4C). There was a trend of improvement in selection capacity with increasing BG doses from 20 μM to 80 μM, which were both significantly higher than the unselected controls (1.4-fold and 1.6-fold, respectively). More effective selection was observed when three cycles of BG/BCNU were applied, resulting in a 2.1-fold enrichment (p < 0.05). This was comparable to results obtained after one cycle of treatment at the hepatic MTD (2.0 fold). These experiments suggest that the multiple BG/BCNU treatments currently employed for successful in vivo HSC selection in animal models could also have selective pressure for hepatic selection, especially if higher BG levels can be reached locally in the liver.

Intracellular and extracellular enzymatic restoration after transduction and selection in enzyme-deficient primary hepatocytes

We next investigated whether transduction and drug selection can lead to over-expression of functional transgene product and enzymatic activity restoration in MPS I hepatocytes. One day after plating, cells were transduced with a LV (TW-EIiM) bicistronically expressing human IDUA cDNA and MGMTP140K from EF1α promoter (Figure 5). Consistent with the marking studies described above, the transduction efficiency, as determined for MGMT expression by flow cytometry, showed a dose-dependent increase from 2.3 ± 1.0% to 12 ± 0.6% at a MOI of 10–100 (Figure 5A). Moreover, the results from three selection experiments with a MOI of 100 showed that intracellular IDUA enzyme activities increased dramatically from being undetectable in MPS I cells to 1852 ± 63 U/mg protein/h in transduced MPS I hepatocyte cultures (Figure 5B). This level was 48-fold higher than those found in wild-type controls (38 ± 5 U/mg protein/h). Moreover, transduced MPS I cells released 811 ± 30 U/ml of functional enzyme to the culture medium within a 24-h period (data not shown). This level of IDUA was 900-fold higher than that from normal controls (0.9 ± 0.3 U/ml), suggesting that a higher proportion of IDUA enzyme may be discharged from transduced cells that over-expressing IDUA. Upon BG/BCNU selection, IDUA activities steadily and significantly (p < 0.01) increased to 2275 and 3072 U/mg protein/h (1.7-fold over unselected) with 50 μM and 100 μM BCNU, respectively. This selective pattern of IDUA enzyme activity is consistent with the levels observed in the marking studies. These results confirmed over-expression and release of functional enzyme in transduced and/or selected primary hepatocytes.

Figure 5.

Transduction and selection with TW-EIiM resulted in escalation of functional transgene products in enzyme-deficient hepatocytes. (A) Transduction efficiency in large hepatocytes determined by FACS analysis for MGMT expression. Data were derived from two separate experiments in triplicate. (B) Intracellular IDUA enzyme activity in hepatocyte cultures transduced at a MOI of 100. Each point represents the mean of duplicate assays in duplicate wells from three separate experiments. WT, wild-type C57/Bl6. p < 0.01 by Student’s t-test among all adjacent data points

Metabolic correction in transduced and neighbouring non-transduced MPS I hepatocytes

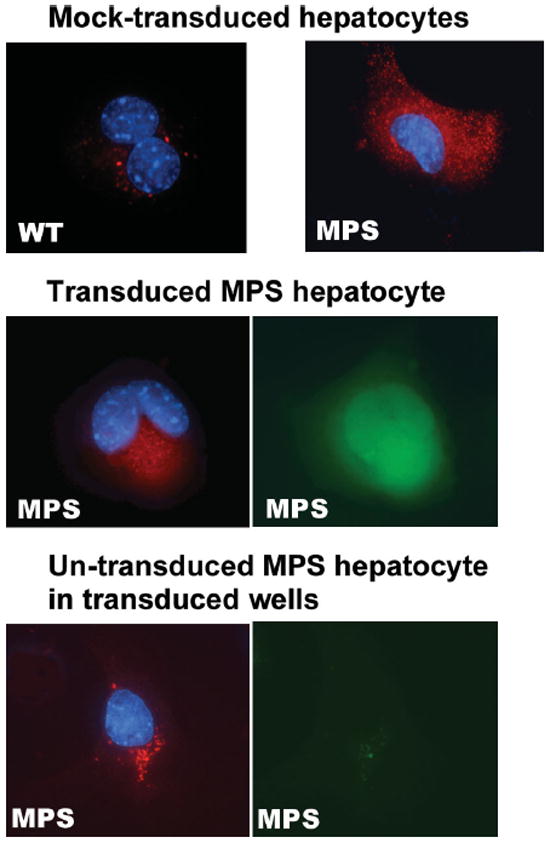

Finally, we evaluated whether the high intracellular and extracellular IDUA enzyme can reverse abnormal metabolism in MPS I hepatocytes. MPS I cells exhibit an increased abundance of lysosomes and an abnormal lysosomal morphology as a direct consequence of GAG accumulation within lysosomes. To evaluate the potential for correction of this atypical lysosomal morphology, we transduced MPS I hepatocytes with EIiM at a MOI of 100, followed by in situ immunostaining 3 days later with a fluorescent dye that can be endocytosed into lysosomes, as well as a mouse anti-human MGMT antibody for identification of transduced cells (Figure 6). MPS I hepatocytes contained more lysosomes and these compartments appeared smaller in size than those observed in normal cells. All transduced MPS I hepatocytes, as identified by positive-MGMT staining, contained fewer lysosomes that were normal in appearance. Moreover, the majority of MGMT-negative MPS I hepatocytes from transduced wells also exhibited a normalized lysosomal pattern, indicating metabolic cross-correction by extracellular IDUA enzyme released from neighbouring transduced cells. These data demonstrated that LV-mediated transgene expression could restore a normal pattern of lysosome distribution and morphology in MPS I primary hepatocytes.

Figure 6.

Normalization of lysosomal abundancy in transduced and neighbouring non-transduced MPS I hepatocytes. Cells grown on coverslips were transduced with TW-EIiM at a MOI of 100, followed by staining with the lysosome-specific fluorescent probe (red) and MGMT antibody (FITC). Representative views are shown for hepatocytes of wild-type (WT), mock-transduced MPS I, MGMT-positive MPS I transductant, and MGMT-negative un-transduced MPS I in transduced wells. Bottom right, control for MGMT staining. Red, LysoTracker; green, MGMT+; blue, DAPI for nuclei

Discussion

One goal of any clinical treatment is the correction of the target disease by a single injection of a therapeutic drug/vector. We and others have demonstrated the feasibility of in vivo gene transfer into adult BM HSC and hepatocytes by a single intravenous injection of LV [21,22], or by relatively localized administration [23,24]. The in vivo gene transfer approach would avoid many of the difficulties encountered by ex vivo HSC gene transfer such as maintaining stem cell properties and the loss of engraftment potential. It may also reduce the risk of genotoxicities related to ex vivo HSC enrichment procedures and cytokine stimulation, which may activate unwanted signaling pathways that could potentially increase the risk of non-random mutagenic events during provirus insertion [31,32]. In vivo hepatic gene transfer could change the liver into a robust source of enzyme ‘factory’ distributing high and consistent levels of therapeutic agent systemically to other organs, instead of a ‘sink’ of enzyme (by first-pass) as seen in conventional enzyme replacement therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. However, the in vivo transduction efficiencies are generally low. The enrichment of transduced HSCs or their progeny by MGMTP140K-mediated selection was demonstrated first in vitro using BG/BCNU treatment [12,13]. This was then further advanced and confirmed by successful in vivo selection of HSC transductants in mice, dogs and monkeys with bone marrow transplantation setting, resulting in significant enhancement of ex vivo transduced HSC [18-20] or human SCID-repopulating cells [14-16]. Whereas, the possibility of BG and BCNU resistance in MGMT-transduced hepatocytes has not yet been previously studied. In the present study, we demonstrated that MGMTP140K expression can confer significant resistance to BG/BCNU in primary hepatocytes, leading to significant enrichment in transduced hepatocytes at hepatic MTD, regardless of relatively high (12%) or low (1.7%) initial transduction efficiency, and notwithstanding the expression of MGMT was upstream or downstream of ires. Moreover, multiple treatments at a relatively low dosage, which was effective for ex vivo HSC selection, led to similar levels of hepatocyte selection under this condition. The escalation in intracellular and extracellular IDUA enzyme levels in transduced enzyme-deficient hepatocytes was found to directly correlate with increasing selection doses, resulting in phenotypic correction in transduced and neighbouring non-transduced hepatocytes.

The success of MGMT-mediated selection by BG/BCNU requires both the efficient elimination of un-transduced cells and the protection of transduced cells. BCNU produces O6-chloroethylguanine DNA adducts that, if left unrepaired by MGMT protein, could result in highly cytotoxic DNA interstrand crosslinks and consequent cell death [33]. In the present study, we found that primary hepatocytes were responsive to sensitization mediated by increasing dosage of BG only at the lowest BCNU dosage (25 μM) (Figure 2). This suggested that as low as 50 μM BCNU may be sufficient to surpass the repairing effect mediated by endogenous MGMT. The phenomenon that approximately 48% of cells were still alive at 50 μM BCNU might result from the delayed mortality associated with inactive cell growth under our culture condition (1.1-fold during 6 days of culture). The expression of variant MGMTP140K in transduced hepatocytes could not only increase the amount of MGMT available for DNA repair, but also provide resistance to BG-mediated inactivation with amino acid substitution (P > K) at position 140. However, the loss of selective advantage in MGMTP140K-expressing hepatocytes was observed when the dosage was higher than 100 μM BCNU. This may be due, at least in part, to insufficient levels of MGMTP140K for repairing the DNA damage at one time because each MGMT molecule can repair only one alkyl lesion. This may also be one of the reasons that multiple cycles of high-BG/low-BCNU (80 μM of BG/30 μM of BCNU) treatment achieved similar enrichment of transduced hepatocytes as those treated at hepatic MTD (20 μM/100 μM) (Figure 4B). Notably, a similar selection pattern (with transductant enrichment in regard to treatment dosages) was observed in primary hepatocytes no matter whether the translation of MGMT was initiated in a regular cap-dependent manner (as with TW-EMiG) or by using internal ribosome entry site (as with TW-EIiM).

The endogenous levels of MGMT protein varies among different tissues (by 100-fold), with the highest levels found in the liver and the lowest in bone marrow [34,35]. Even though the reasons underlying this tissue variation are not clear, we have demonstrated that selectivity to BG/BCNU is not proportionally correlated to the methyltransferase levels based on the comparison of BCNU survival curves. We found that the effective dosage of BCNU to eliminate untransduced hepatocytes was only approximately five-fold higher than that for murine hematopoietic progenitors [36]. Moreover, multiple treatments at a dose effective for ex vivo HSC enrichment led to a level of hepatocyte selection similar to those obtained at hepatic MTD. Thus, it is likely that the BG/BCNU regimens currently employed for successful in vivo HSC selection in animal models may also have strong selective pressure for hepatic co-selection, especially if a higher BG level can be reached locally in the liver.

Extensive enrichment of MGMT+ cells was observed in non-tumorigenic hepatic AML12 cell line (from 3% to 92%) treated with AML12 MTD after more than five post-selection cell divisions (14 days). However, only a two-fold increase of transduced cells was detected 3 days after selection in primary hepatocytes treated with hepatic MTD. This may be largely due to the minimum cell expansion under our culture conditions to mimic in vivo adult hepatocyte growth. The delayed cell death and relatively short-term post selection observation are also likely to contribute to the limited increase of transduced cells shown in primary hepatocytes.

To optimize MGMT expression required for effective selection, we compared the activity of the SFFV LTR and human EF1α gene promoter in primary hepatocytes in vitro. The SF promoter [25] has been shown to introduce strong and sustained transgene expression in human and murine HSC, as well as their multi-lineage progenies [37]. However, the capability of strong LTRs to activate adjacent coding sequences in both directions may ascribe additional risk of insertional mutagenesis [38]. Stable activity of the EF1α promoter has been reported in primary cells across different lineages and tissue boundaries, including embryonic stem cells, neuronal precursors, and hematopoietic systems. We found much higher activity of SF promoter over EF1α in human kidney 293T cells (3.7-fold), which was consistent with observations by others. However, the expression from the EF1α promoter was higher than that from the SF promoter in transduced primary hepatocytes (1.6-fold). Although the sustainability of the EF1α promoter was not investigated in the present study due to the limitation of maintaining hepatic phenotype in ex vivo culture, others have reported long-term in vivo transgene expression by EF1α after AAV-mediated gene transfer to the liver [34]. Thus, the cellular EF1α promoter may be more suitable for high-level and stable ubiquitous gene expression in both hepatocytes and HSC.

Normally, a small proportion of IDUA enzyme ‘leaks’ out to the extracellular environment and is available for receptor-mediated reuptake and reuse by other cells. In normal hepatocytes, we detected 38 U/mg intracellular IDUA activity with only 0.9 nmol/ml enzyme released to the culture medium within a 24-h period. Upon transduction with TW-EIiM, we found 48-fold higher-than-normal IDUA levels in transduced MPS I hepatocyte cultures, but 900-fold higher-than-normal IDUA activities in culture medium. These results suggested that a higher proportion of IDUA enzyme may be discharged from transduced cells that are over-expressing IDUA. This would identify liver favourably as an ‘enzyme-factory’ to provide constant therapeutic enzyme for reuptake by other non-transduced tissues and organs.

In summary, this present study demonstrates for the first time the feasibility of protection and selection of primary hepatocytes against the combined treatment of BG/BCNU in vitro via LV-mediated expression of MGMTP140K, including when it is downstream of an ires in a bicistronic setting. Metabolic correction and cross-correction are also shown in transduced/selected and non-transduced neighbouring hepatocytes from MPS I mice. Clearly, transduction of MGMTP140K, even at minimum levels (1.7%), conferred resistance to the drug combination of BG/BCNU in hepatocytes. Moreover, the BCNU dosage effective for ex vivo HSC selection was also shown to provide efficient selection, similar to those using hepatic maximal tolerated dose, on primary hepatocytes after multiple cycles of treatment. This suggested that the BG/BCNU regimens utilized for efficient in vivo HSC selection would also have significant in vivo selective pressure on hepatocytes. These data provide ‘proof of concept’ to the possibility of MGMTP140K-mediated co-selection for HSC and hepatocytes by BG/BCNU treatment. Further in vivo studies will be needed to assess the utility of systemic in vivo co-selection mainly targeting to HSC and hepatocytes, as well as the relative toxicities associated with the use of DNA-methylating agents. Strategies to stimulate in vivo hepatocyte proliferation, such as nontraumatic physiological hormone tri-iodothyronine induced hyperplasia [39] and the vascular delivery of HGF [40,41], or surgical partial hepatectomy, during BG/BCNU treatment, may further increase MGMTP140K-mediated hepatocyte selection in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr David Williams for the MGMTP140K cDNA and his valuable suggestions, Dr Christopher Baum for the SFFV LTR promoter, and Dr Tal Kafri for LV packaging helper plasmids. We also thank Dr Punam Malik for critical reading of this manuscript. This study is supported in part by TRI grant from Cincinnati Children’s Foundation and NIH grant AI061703 (D.P.).

References

- 1.Sands MS, Davidson BL. Gene therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Mol Ther. 2006;13:839–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopwood JJ, Morris CP. The mucopolysaccharidoses. Diagnosis, molecular genetics and treatment. Mol Biol Med. 1990;7:381–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neufeld EF. Lysosomal storage diseases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:257–280. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.001353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Souillet G, Guffon N, Maire I, et al. Outcome of 27 patients with Hurler’s syndrome transplanted from either related or unrelated haematopoietic stem cell sources. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:1105–1117. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staba SL, Escolar ML, Poe M, et al. Cord-blood transplants from unrelated donors in patients with Hurler’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1960–1969. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grewal S, Shapiro E, Braunlin E, et al. Continued neurocognitive development and prevention of cardiopulmonary complications after successful BMT for I-cell disease: a long-term follow-up report. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:957–960. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters C, Balthazor M, Shapiro EG, et al. Outcome of unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation in 40 children with Hurler syndrome. Blood. 1996;87:4894–4902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biffi A, Capotondo A, Fasano S, et al. Gene therapy of metachromatic leukodystrophy reverses neurological damage and deficits in mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3070–3082. doi: 10.1172/JCI28873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Le Deist F, Carlier F, et al. Sustained correction of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by ex vivo gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1185–1193. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiuti A, Slavin S, Aker M, et al. Correction of ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy combined with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Science. 2002;296:2410–2413. doi: 10.1126/science.1070104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ott MG, Schmidt M, Schwarzwaelder K, et al. Correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease by gene therapy, augmented by insertional activation of MDS1-EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1. Nat Med. 2006;12:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zielske SP, Gerson SL. Lentiviral transduction of P140K MGMT into human CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitors at low multiplicity of infection confers significant resistance to BG/BCNU and allows selection in vitro. Mol Ther. 2002;5:381–387. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawai N, Zhou S, Vanin EF, Houghton P, Brent TP, Sorrentino BP. Protection and in vivo selection of hematopoietic stem cells using temozolomide, O6-benzylguanine, and an alkyltransferase-expressing retroviral vector. Mol Ther. 2001;3:78–87. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai S, Hartwell JR, Cooper RJ, et al. In vivo effects of myeloablative alkylator therapy on survival and differentiation of MGMTP140K-transduced human G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood cells. Mol Ther. 2006;13:1016–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollok KE, Hartwell JR, Braber A, et al. In vivo selection of human hematopoietic cells in a xenograft model using combined pharmacologic and genetic manipulations. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1703–1714. doi: 10.1089/104303403322611728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zielske SP, Reese JS, Lingas KT, Donze JR, Gerson SL. In vivo selection of MGMT (P140K) lentivirus-transduced human NOD/SCID repopulating cells without pretransplant irradiation conditioning. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1561–1570. doi: 10.1172/JCI17922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ragg S, Xu-Welliver M, Bailey J, et al. Direct reversal of DNA damage by mutant methyltransferase protein protects mice against dose-intensified chemotherapy and leads to in vivo selection of hematopoietic stem cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5187–5195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Persons DA, Allay ER, Sawai N, et al. Successful treatment of murine beta-thalassemia using in vivo selection of genetically modified, drug-resistant hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2003;102:506–513. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neff T, Horn PA, Peterson LJ, et al. Methylguanine methyltransferase-mediated in vivo selection and chemoprotection of allogeneic stem cells in a large-animal model. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1581–1588. doi: 10.1172/JCI18782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neff T, Beard BC, Peterson LJ, Anandakumar P, Thompson J, Kiem HP. Polyclonal chemoprotection against temozolomide in a large-animal model of drug resistance gene therapy. Blood. 2005;105:997–1002. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan D, Gunther R, Duan W, et al. Biodistribution and toxicity studies of VSVG-pseudotyped lentiviral vector after intravenous administration in mice with the observation of in vivo transduction of bone marrow. Mol Ther. 2002;6:19–29. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Follenzi A, Sabatino G, Lombardo A, Boccaccio C, Naldini L. Efficient gene delivery and targeted expression to hepatocytes in vivo by improved lentiviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:243–260. doi: 10.1089/10430340252769770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park F, Ohashi K, Kay MA. The effect of age on hepatic gene transfer with self-inactivating lentiviral vectors in vivo. Mol Ther. 2003;8:314–323. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worsham DN, Schuesler T, von Kalle C, Pan D. In vivo gene transfer into adult stem cells in unconditioned mice by in situ delivery of a lentiviral vector. Mol Ther. 2006;14:514–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baum C, Hunt N, Hildinger M, et al. cis-Active elements of Friend spleen focus-forming virus: from disease induction to disease prevention. Acta Haematol. 1998;99:156–164. doi: 10.1159/000040830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan D, Aronovich E, McIvor RS, Whitley CB. Retroviral vector design studies toward hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1875–1883. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber-Benarous A, Decaux JF, Bennoun M, Allemand I, Briand P, Kahn A. Retroviral infection of primary hepatocytes from normal mice and mice transgenic for SV40 large T antigen. Exp Cell Res. 1993;205:91–100. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen BE, Bowen WC, Patrene KD, et al. Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells. Science. 1999;284:1168–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oertel M, Rosencrantz R, Chen YQ, et al. Repopulation of rat liver by fetal hepatoblasts and adult hepatocytes transduced ex vivo with lentiviral vectors. Hepatology. 2003;37:994–1005. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen TH, Oberholzer J, Birraux J, Majno P, Morel P, Trono D. Highly efficient lentiviral vector-mediated transduction of nondividing, fully reimplantable primary hepatocytes. Mol Ther. 2002;6:199–209. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baum C, Dullmann J, Li Z, et al. Side effects of retroviral gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2003;101:2099–2114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Modlich U, Bohne J, Schmidt M, et al. Cell-culture assays reveal the importance of retroviral vector design for insertional genotoxicity. Blood. 2006;108:2545–2553. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-024976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitra S, Kaina B. Regulation of repair of alkylation damage in mammalian genomes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1993;44:109–142. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mingozzi F, Liu YL, Dobrzynski E, et al. Induction of immune tolerance to coagulation factor IX antigen by in vivo hepatic gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1347–1356. doi: 10.1172/JCI16887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moritz T, Mackay W, Glassner BJ, Williams DA, Samson L. Retrovirus-mediated expression of a DNA repair protein in bone marrow protects hematopoietic cells from nitrosourea-induced toxicity in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2608–2614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maze R, Carney JP, Kelley MR, Glassner BJ, Williams DA, Samson L. Increasing DNA repair methyltransferase levels via bone marrow stem cell transduction rescues mice from the toxic effects of 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea, a chemotherapeutic alkylating agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:206–210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demaison C, Parsley K, Brouns G, et al. High-level transduction and gene expression in hematopoietic repopulating cells using a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based lentiviral vector containing an internal spleen focus forming virus promoter. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:803–813. doi: 10.1089/10430340252898984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammond SM, Crable SC, Anderson KP. Negative regulatory elements are present in the human LMO2 oncogene and may contribute to its expression in leukemia. Leuk Res. 2005;29:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forbes SJ, Themis M, Alison MR, et al. Tri-iodothyronine and a deleted form of hepatocyte growth factor act synergistically to enhance liver proliferation and enable in vivo retroviral gene transfer via the peripheral venous system. Gene Ther. 2000;7:784–789. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minami H, Tada K, Chowdhury NR, Chowdhury JR, Onji M. Enhancement of retrovirus-mediated gene transfer to rat liver in vivo by infusion of hepatocyte growth factor and triiodothyronine. J Hepatol. 2000;33:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patijn GA, Lieber A, Schowalter DB, Schwall R, Kay MA. Hepatocyte growth factor induces hepatocyte proliferation in vivo and allows for efficient retroviral-mediated gene transfer in mice. Hepatology. 1998;28:707–716. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]