Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether there is a difference in the treatment effect of donepezil on cognition in Alzheimer disease between industry-funded and independent randomised controlled trials.

Design

Fixed effects meta-analysis of standardised effects of donepezil on cognition as measured by the Mini Mental State Examination and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale.

Data sources

Studies included in the meta-analyses reported in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) technical appraisal 217 updated with new studies through a PubMed search.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of any length comparing patients diagnosed with probable Alzheimer disease (according to the NINCDS-ADRDA/DSM-III/IV criteria) taking any dosage of donepezil. Studies of combination therapies (eg, donepezil and memantine) were excluded, as were studies that enrolled patients with a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease associated with other disorders (eg, Parkinson's disease and Down's syndrome).

Results

Our search strategy identified 14 relevant trials (4 independent) with suitable data. Trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies reported a larger effect of donepezil on standardised cognitive tests than trials published by independent research groups (standardised mean difference (SMD)=0.46, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.55 vs SMD=0.33, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.48, respectively). This difference remained when only data representing change up to 12 weeks from baseline were analysed (industry SMD=0.44, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.53 vs independent SMD=0.35, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.52). Analysis revealed that the effect of funding as a moderator variable of study heterogeneity was not statistically significant at either time point.

Conclusions

The effect size of donepezil on cognition is larger in industry-funded than independent trials and this is not explained by the longer duration of industry-funded trials. The lack of a statistically significant moderator effect may indicate that the differences are due to chance, but may also result from lack of power.

Keywords: CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First study to review and demonstrate an objective effect of industry funding on donepezil randomised controlled trial outcome.

Results are also controlled for different trial lengths.

Limited number of included trials.

Evidence is limited to cognitive changes.

Introduction

Dementia is of growing national importance, and Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common cause. In spite of this, treatment for AD is limited, and recent trials of new therapies have yielded disappointing results.1 In March 2011, the National Health Service's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded that donepezil hydrochloride (trade name Aricept, Pfizer) could be ‘recommended as (an option) for managing mild as well as moderate AD’.2 The conclusion was drawn despite reportedly poor cost efficacy3 and opinions that the use of the drug is a ‘desperate measure’.4

The NICE decision was based on two meta-analyses (the second was an update of the first) of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that demonstrated donepezil's effect on measures of cognition, behaviour, function and global skills.5 6 Of the 19 studies included, 12 were produced by the companies that manufacture and market donepezil. This is important because industry-sponsored clinical trials are more likely to find preferential outcomes for the industry's product than non-sponsored studies,7–9 demonstrating a pervasive effect of ‘industry bias’.10 A failure to address this potential bias in meta-analyses increases the risk of inflating the drug's true efficacy.11 12

While the different results published by industry-funded and non-industry-funded donepezil RCTs have been examined with respect to language and rhetoric,13 the potential bias on funding sources has not been examined by means of a formal meta-analysis. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of all relevant RCTs of donepezil in patients with mild-to-moderate AD, stratifying by the source of funding.

Method

Study selection

We updated previous systematic reviews5 6 of RCTs using a PubMed search strategy modified from that proposed by Loveman et al6 in October 2012. Our search strategy was amended to include any examples of donepezil's effect on neuropsychological tests (see online supplementary appendix 1).

Eligibility criteria

We included double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs of any length comparing patients diagnosed with mild-to-moderate probable AD (according to either National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) III/IV criteria) taking any dosage of donepezil. Studies were required to compare and report the change from baseline on cognitive, behavioural, functional or global assessments in the donepezil and placebo groups. Studies that considered other separate treatment arms in addition to the donepezil and placebo groups were also included. RCTs that enrolled patients with mixed dementias were included if AD was the predominant dementia. Studies that assessed the effect of donepezil in patients with AD in addition to other non-dementia-related diseases as separate treatment arms were also deemed suitable for inclusion. Studies of combination therapies (eg, donepezil and memantine) were excluded, as were studies that focused exclusively on patients with a diagnosis of AD associated with other disorders (eg, Parkinson's disease and Down's syndrome).

Data collection

One author extracted data from included trials (LOJK). Information was recorded on: study sponsor, sample size, duration of the study, setting, characteristics of patients, clinical diagnosis and cognitive assessment (mean change from baseline). Relevant missing data were requested from the corresponding authors. Only data for changes on cognitive scales were collected due to limited data detailing change in behaviour and function in independent trials. Trials were defined as ‘industry-funded’ if any of the authors were employees of the sponsoring pharmaceutical industry, or if the trial's only source of funding was from the sponsoring industry. Papers that did not qualify for this definition were labelled as independent of industry funding (or ‘independent’). Two authors independently classified the included trials—LOJK and TCR. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or referred to a third author (SDS).

Assessing bias

Risk of bias in included trials was assessed using the relevant Cochrane Collaboration's tool.14 This tool assesses the risk of bias across the domains of selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting. Trials are noted as having a high, low or uncertain risk of bias for these specific domains. High or low risk is associated with reporting inadequate or adequate methods of avoiding bias, respectively. Uncertain risk is associated with partial or absent reports for these methods. The risk of bias for trials included in the two systematic reviews reported in the NICE technical appraisal 217 was already assessed.6 7 The risk of bias for new trials identified by the updated search strategy was assessed by one author (LOJK). Publication bias was assessed with a significance test of funnel plot asymmetry for effects reported at the study endpoint.

Planned analysis

Meta-analysis

We compared the standardised mean difference (SMD) in cognitive scales (Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog)) between the placebo and donepezil groups in independent and industry-funded trials at each study's chosen endpoint. The heterogeneity between trials was examined using the I2 statistic, which indicates the proportion of the total variation in the estimates that is due to between-studies variation. I2 for the included trials varied between 0% and 20%. Owing to this lack of heterogeneity, we considered it appropriate to pool independent trials separately from industry-funded trials using fixed effects meta-analyses.

However, the effect of industry sponsorship may be confounded by the duration of trials, as independent trials are shorter and may not be able to observe the relatively long-term effects of donepezil. To control for this, we conducted a subgroup analysis comparing the effect of donepezil and placebo up to and including observations made at 12 weeks from baseline. We chose this period as it was the point at which most data were available for industry-funded and independent trials that was also representative of the short-time frame of independent trials and to accommodate the fact that, for some trials, there were no data documenting change prior to 12 weeks from baseline.

In order to investigate whether the overall heterogeneity of included trials was significantly affected by the presence of industry funding, we conducted an additional fixed effects model with funding as a moderator variable for data from all time points and up to 12 weeks. To understand if the differences between the independent and industry-funded effects were likely to be statistically significant, we investigated whether the effect size of the independent trials fell within the 95% CIs of the industry-funded effect.

All analyses were run using R V.2.15.215 with the metafor package.16

Results

Search results

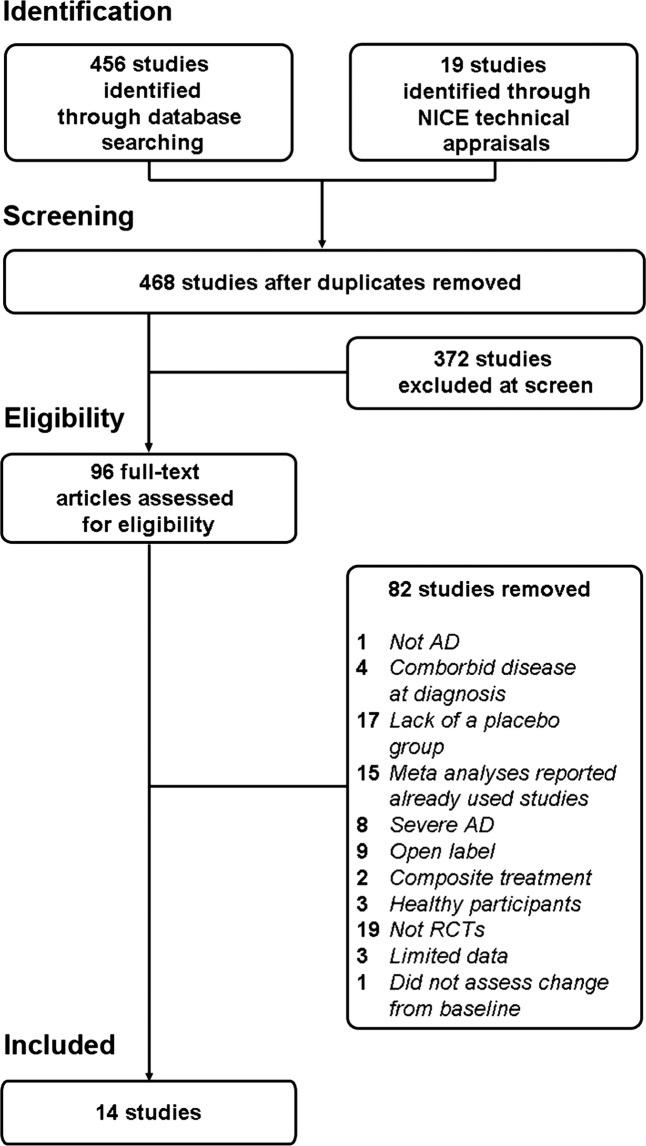

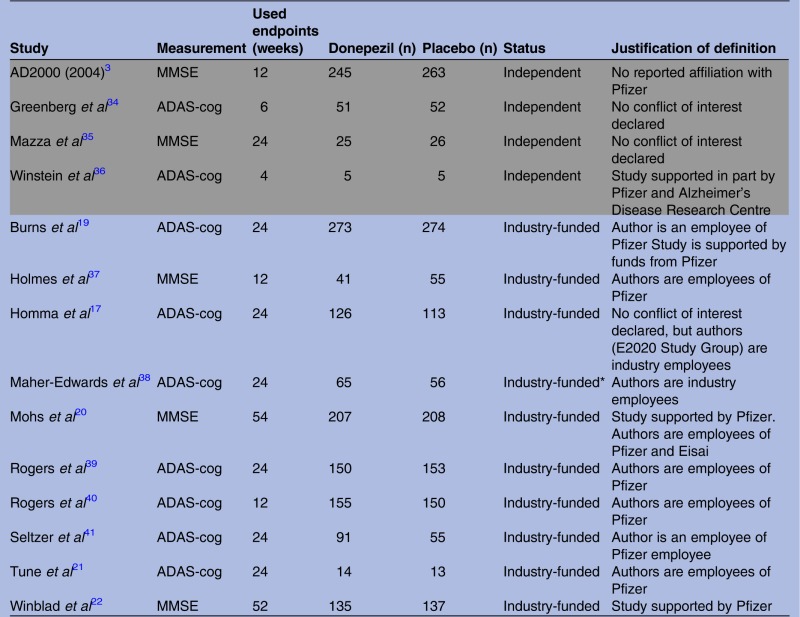

Figure 1 shows the selection process of trials included in the current meta-analyses. A total of 14 trials (10 industry-funded and 4 independent) were deemed suitable for inclusion. A summary description of the 14 included trials is given in table 1. All trials made their source of funding clear, with the exception of one trial,17 the authors of which declared to be industry-funded in a later publication.18

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included and excluded studies selected for this meta-analysis. AD, Alzheimer disease; RCT, randomised controlled trial; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Table 1.

Descriptions of the randomised controlled trials used in this meta-analysis

|

Independent studies are reported in grey rows.

*This is a GlaxoSmithKline study that investigates its own product in comparison to donepezil and placebo.

ADAS-cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination.

Risk of bias

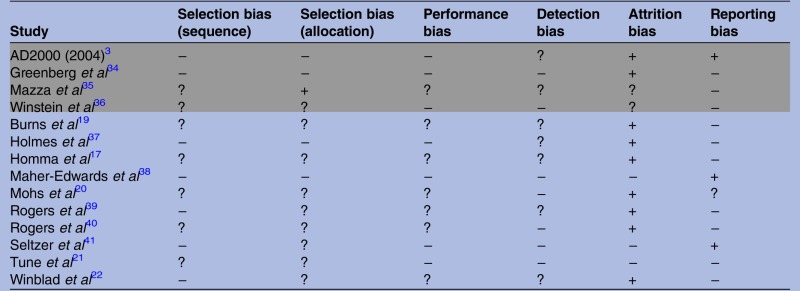

Table 2 shows that none of the included trials were free from biases. One important issue was a failure to report how biases were (or were not) controlled. Where they were reported, the trials had generally poor methodological quality. There was no clear difference in the risk of bias between independent and industry-funded trials. A test for funnel plot asymmetry returned a non-significant result (z=0.28, p=0.78), suggesting that publication bias did not have a substantial effect.

Table 2.

Relative risk of types of bias observed in randomised controlled trials reporting the effect of donepezil in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer disease

|

Independent studies are reported in grey rows.

Risk is assessed as high (+), low (−) or uncertain (?). High or low risk is assigned when methods to avoid bias are inadequate or adequate, respectively. Uncertain risk is assigned when methods to avoid bias are either partially reported or not reported.

Meta-analyses

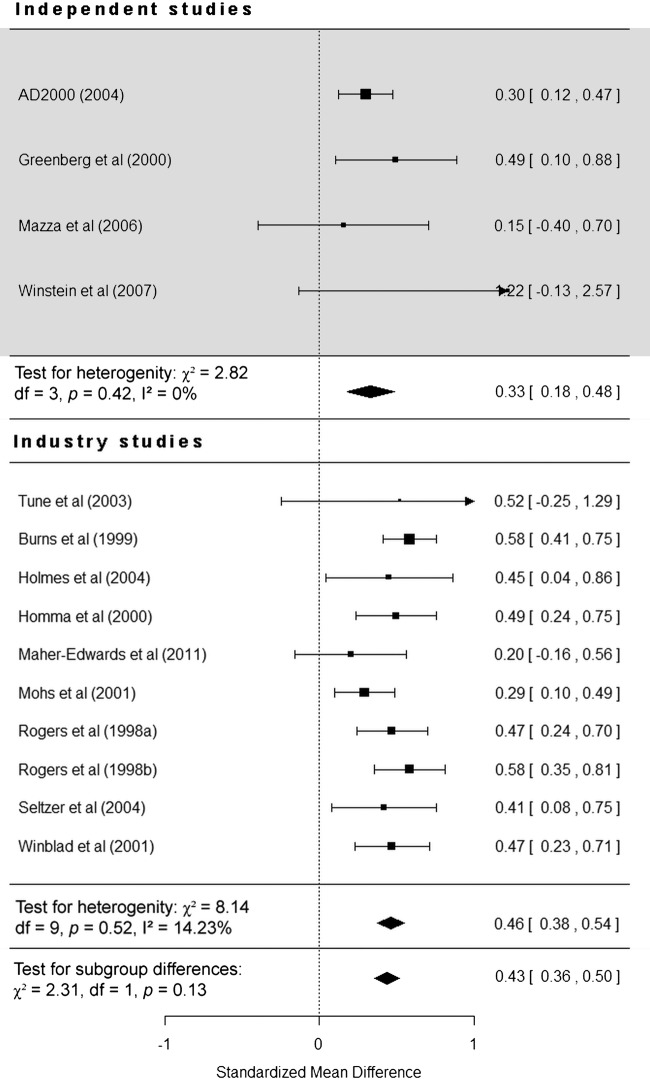

SMD at all time points

A total of 14 studies (4 independent) were included in this analysis. The overall effect of donepezil on cognition was statistically significant (SMD=0.43, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.50, p<0.0001), and independent and industry-funded studies report donepezil as being significantly more effective than placebo (p<0.0001). The effect of donepezil on SMD in cognitive scales was larger in industry-funded studies (SMD=0.46, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.54) than in independent studies (SMD=0.33, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.48; figure 2), giving a difference of 0.13 (95% CI −0.1 to 0.36). Funding was not found to be a statistically significant moderator of study heterogeneity (χ2 (1)=2.31, p=0.13).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of individual independent and industry-funded studies’ reported effect (standardised mean difference) of donepezil compared with placebo on cognitive scales observed at study endpoint (95% CIs).

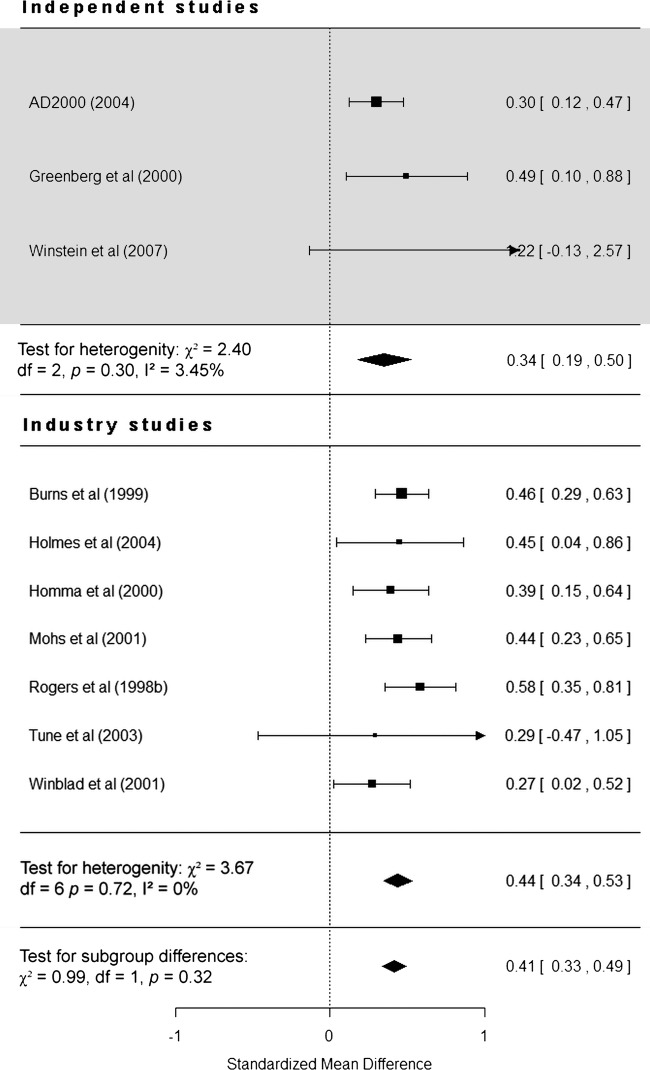

Subgroup analysis: SMD at 12 weeks

Restricting the analysis to 10 studies (3 independent) that assessed the effect of donepezil up to 12 weeks from baseline did not affect the pattern of results reported above. Data for five of these studies did not represent their chosen endpoint.17 19–22 The overall effect of donepezil is still statistically significant (SMD=0.41, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.49, p<0.0001), and independent and industry-funded studies report donepezil as being significantly more effective than placebo (p<0.0001). Industry-funded studies still report a larger effect (SMD=0.44, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.53) compared with independent studies (SMD=0.34, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.50; figure 3), giving a difference of 0.1 (95% CI −0.15 to 0.35). As before, funding was not found to be a statistically significant moderator of study heterogeneity (χ2 (1)=0.99, p=0.32).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of individual independent and industry-funded studies’ reported effect (standardised mean difference) of donepezil compared with placebo on cognitive scales observed up to 12 weeks from baseline (95% CIs).

Discussion

Summary

Across included trials, the overall effect of donepezil on cognition was statistically significant. However, crucially, the SMD change in cognitive scores between the donepezil and placebo groups was larger in trials supported by the pharmaceutical industry than that observed in trials funded by independent organisations. This pattern of results remained when we controlled for study endpoint by only considering change up to 12 weeks from baseline. Analysis revealed that the effect of funding as a moderator variable of study heterogeneity was not statistically significant at either time point.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This report is the first to stratify and analyse the effect of donepezil according to funding source. It includes all currently available published evidence regarding the effect of donepezil. The analysis with data only up to 12 weeks demonstrates that the discrepancy reported here is unlikely to be solely due to the longer duration of industry-funded studies.

Our analyses revealed that there was no statistically significant effect of funding source on study heterogeneity. This suggests that the different effects reported in independent and industry-funded studies may be due to chance. This possibility is also supported by the evidence that the CIs of the difference contain zero. However, it is important to note that a common pitfall of heterogeneity analyses is that they lack the necessary power (ie, a sufficient number of studies) to reliably detect moderator effects.23 24 This is likely to be an issue in the current meta-analyses, as the samples included contain 10 or fewer studies. This possibility is supported by a recent review which simulated the power of moderator analyses given the number of studies in a meta-analysis, the number of participants in these studies and the expected moderator effect size.25 With reference to their findings, a meta-analysis of the current study's size may not have sufficient power (0.8) to reliably detect a small-to-medium moderator effect. It is also worth noting that the level of α for these analyses should be increased to 0.10 to remedy these power issues.23 The difference we report for the effect at all time points (figure 2) can be interpreted as being at near-significance level (0.13).

Therefore, the lack of statistical significance in heterogeneity may reflect the study's lack of power to detect a true small or medium moderator effect.

Independent studies could not be included in the meta-analyses due to insufficient data in the published reports. Consequently, this lack of data could result in a less robust independent treatment effect than that observed in industry-funded studies. The dearth of data in conjunction with the variability of study duration and cognitive scales used restricted the number of possible controlled comparisons, and required the use of SMDs rather than clearly comparing differences on a particular scale (eg, ADAS-cog and MMSE). Finally, we were not able to assess differences with respect to changes of behaviour, function or global functioning since these outcomes were not reported sufficiently often to allow their inclusion in relevant meta-analyses. These variables should not, however, be overlooked, as these changes contribute towards the time to institutionalisation, which in turn affects the cost-effectiveness of donepezil.2 It would be useful to see if these measures too are affected by the source of funding.

Ultimately, these limitations of available data and of power are intrinsic to analysing reported (ie, published) aggregated data. These same limitations could be overcome with greater transparency of clinical data, or possibly through meta-analysing individual participant data.26 Specifically, the authors argue that meta-analyses of individuals’ data afford researchers with greater precision when estimating the effect of an intervention—or what may moderate this effect—as there is more scope in adjusting for confounding factors. Furthermore, the authors also present a simulated example where the power of a meta-analysis used to detect moderator effects on treatment is far greater when individual data are used (90.8%) compared with when aggregated data are used (14.8%). In the case of the latter meta-analysis, this power indicates that there is an 85.2% chance of failing to detect any moderator effect. This change to the reporting of future studies would allow questions like those of the current study to be assessed with greater precision.

Other literature

This meta-analysis has provided a distinct example of the established phenomenon that industry funding is associated with a higher favourable outcome for the industry's product,7 as is the presence of an industry employee among trials’ authors.9 While we cannot calculate the chance of a favourable outcome given the company's funding, the observation that such trials report larger SMDs compared with independent trials implies that a favourable outcome is more likely in industry-funded trials.

With regard to the donepezil trials, the analyses complement the more positive language and rhetoric (for instance, frequent references to a drug's effect as ‘significant’ outside of explicitly stated statistical significance) reported by industry papers for this drug as summarised by Gilstad and Finucane,13 suggesting that the effect of donepezil in industry-funded papers is qualitatively and quantitatively amplified. The same authors argued that the effects reported by industry-funded and independent trials were comparable. However, they did not formally examine or calculate effect size, but rather referred to the range of treatment effect on particular scales.

The pattern of effects reported here has also been observed in other meta-analyses that stratify by source of funding. Specifically, the overall effect of donepezil masking discrepant industry-funded and independent effects mirrors a previous meta-analysis investigating smoking as a risk factor for AD.12 While the overall effect of smoking as a risk factor produced an incorrect null result (ie, cigarette smoke was not a risk for developing AD), the overall protective effect of smoking in tobacco in industry-funded trials cancelled out the increased risk shown by non-tobacco industry trials. While the results of the current study confirm that donepezil is effective in terms of cognitive outcomes, it provides another instance of how a meta-analysis may amalgamate conflicting evidence and produce an overall inaccurate effect if funding sources are not considered.

Understanding this effect

The effect sizes—and the difference between them—can be interpreted and understood as change in points on the MMSE. The industry-funded effect (0.46) was similar to the effect size reported by Holmes et al, 2004 (0.45), which equates to a two-point improvement on the MMSE. The independent effect (0.33), however, was similar to the effect size reported by the AD2000 study (0.30), which equates to a one-point improvement on the MMSE. Although the ‘translations’ of these effects are estimates, we can argue that the difference in SMDs reported in the present analysis approximately equates to a difference of one point on the MMSE.

We cannot conclude from these data whether the difference in the magnitude of treatment effect is due to inflated effect estimates in the industry-funded trials or to an underestimated effect in the independent trials; nor can we deduce the reason for it. However, previous literature has raised possibilities for this discrepancy that may be applicable to donepezil trials.7 8

The first is the use of data monitoring in trial management. Data monitoring committees in trials are a common interim safeguard against ineffective or potentially dangerous treatments. However, the use of committees introduces the possibility of bias, either through post hoc amendments to study design11 or by terminating studies that show the drug to be ineffective at a preliminary stage, violating the uncertainty principle and equipoise of treatment efficacy.27 28 Although there is no evidence to suggest that monitoring is more prevalent in industry studies than independent trials, a 2005 survey of committees revealed that industry employees are also members of the committees for their company's trial.29 Therefore, it is likely that commercially unsuccessful trials are terminated early. Second, the effects demonstrated here may reflect different rates of publication bias between independent and industry-funded trials. While design bias entails publication bias, the latter alone cannot explain examples of overwhelmingly positive evidence from industry-sponsored trials.27 Therefore, it is most likely that trials that are monitored and deemed likely to succeed are in turn more likely to be published. Furthermore, there was no evidence of publication bias on examination of a funnel plot of included trials. Third, there may be differences in patient populations across trials. There were no obvious differences between the groups of patients—in terms of scores on the MMSE or from the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale. However, it should be noted that the AD2000 trial is the only study to explicitly report the inclusion of patients with vascular dementia (for which donepezil is not licensed in the UK), who comprised 18% of the donepezil group.3 All other trials either explicitly stated exclusion of vascular dementia or did not report the proportion of participants with vascular dementias. Fourth, the discrepancy may be due to the relative efficacy of the placebo. However, while variation in the placebo effect is well documented and conceivable in trials,30 and although placebo treatments are rarely described, it is unclear how patients in the placebo group would systematically differ with respect to study funding. Finally, it is possible that the differences here are explained by the methodological quality of the included trials. However, the risk of bias assessment for individual trials suggests that industry-funded and independent trials are as likely to show methodological shortcomings. This, in conjunction with previous research, suggests that the quality of the included trials does not differ based on funding. Specifically, a review of donepezil trials indicates that they all in some way have methodological biases,31 despite a source of funding. The poor quality of recent RCTs of donepezil was also raised in the latest systematic review included in the NICE technical appraisal 217.5

Implications

Ultimately, while the pharmaceutical industry's influence is ubiquitous and something ‘researchers cannot stop’,32 it can at least be identified before deciding whether meta-analysed effects are as advertised. Our study suggests that any effect of treatment that is included in a meta-analysis should be stratified by a funding source. In the absence of this practice, we should at least be cautious in interpreting any reported effect of treatment from a meta-analysis including (but not solely consisting of) industry-funded trials. A possible way forward would be a consistent protocol for reporting conflicts of interest that is currently lacking at the level of systematic reviews and meta-analyses,33 as well as of primary studies.32 The frequency of poorly or partially reported methods obscures the exact methodology used in these studies and highlights the need for a robust and agreed standard of reporting. Future studies should strive to reduce methodological differences between trials to ensure that any effects of treatment are readily and more easily comparable.

Conclusions

Based on the included data, the effect of donepezil compared with placebo assessed by SMD change in cognition in AD is larger in industry-funded trials than in independent trials. This is unlikely to be due to differences in trial duration. The lack of a statistically significant moderator effect may indicate that the differences are due to chance, but may also result from lack of power.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the production of this manuscript. LOJK participated in the literature search, data collection, analysis and interpretation and in the drafting of the manuscript and figures. TCR participated in the data analysis and critical review of the manuscript. JMS participated in a critical review of the manuscript and study supervision. SA participated in critical review of the manuscript and study supervision. SDS participated in the study concept, critical review of the manuscript and study supervision.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: LOJK is supported by a University of Edinburgh scholarship supported by the Medical Research Council Doctoral Training Grant and the School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. During the preparation of the manuscript, TCR was supported by Alzheimer Scotland and employed in the National Health Service (NHS) by the Scottish Dementia Clinical Research Network, which is funded by the Chief Scientist Office (part of the Scottish Government Health Directorates). LOJK, TCR and JMS are members of the Alzheimer Scotland Dementia Research Centre funded by Alzheimer Scotland. TCR, JMS, SA and SDS are members of the University of Edinburgh Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology, part of the cross council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing Initiative (G0700704/84698).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. The dataset is available from the corresponding author at the Dryad repository, which will provide a permanent, citable and open access home for the dataset.

References

- 1.Callaway E. Alzheimer's drugs take a new tack. Nature 2012;489:13–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NICE. Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease 2011

- 3.Courtney C, Farrell D, Gray R, et al. Long-term donepezil treatment in 565 patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD2000): randomised double-blind trial. Lancet 2004;363:2105–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finucane T. Omitting donepezil is hardly a hardship. BMJ 2007;954 http://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/11/01/omitting-donepezil-hardly-hardship [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond M, Rogers G, Peters J, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (review of TA111): a systematic review and economic model. Health Technol Assess 2012;16:1–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loveman E, Green C, Kirby J, et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine for Alzheimer's disease. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:1–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, et al. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:1167–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker CB, Johnsrud MT, Crismon ML, et al. Quantitative analysis of sponsorship bias in economic studies of antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry 2003;183:498–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tungaraza T, Poole R. Influence of drug company authorship and sponsorship on drug trial outcomes. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:82–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundh A, Lexchin J, Sismondo S, et al. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:MR000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Systematic reviews: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1086–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cataldo JK, Prochaska JJ, Glantz SA. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: an analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;19:465–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilstad JR, Finucane TE. Results, rhetoric, and randomized trials: the case of donepezil. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1556–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Altman D, Gøtzsche P, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2008. http://www.r-project.org

- 16.Lumley T.2012. rmeta.

- 17.Homma A, Takeda M, Imai Y, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of donepezil on cognitive and global function in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2000;11:299–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homma A, Imai Y, Tago H, et al. Donepezil treatment of patients with severe Alzheimer's disease in a Japanese population: results from a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;25:399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burns A, Rossor M, Hecker J, et al. The effects of donepezil in Alzheimer's disease—results from a multinational trial 1. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999;10:237–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohs RC, Doody RS, Morris JC, et al. A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients. Neurology 2001;57:481–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tune L, Tiseo PJ, Ieni J, et al. Donepezil HCl (E2020) maintains functional brain activity in patients with Alzheimer disease: results of a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;11:169–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winblad B, Engedal K, Soininen H, et al. A 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate AD. Neurology 2001;57:489–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Green S.eds Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.2. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sedgwick P. Meta-analyses: heterogeneity and subgroup analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hempel S, Miles JNV, Booth MJ, et al. Risk of bias: a simulation study of power to detect study-level moderator effects in meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2013;2:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct and reporting. BMJ 2010;340:c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fries JF, Krishnan E. Equipoise, design bias, and randomized controlled trials: the elusive ethics of new drug development. Arthritis Res Ther 2004;6:R250–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djulbegovic B, Lacevic M, Cantor A, et al. The uncertainty principle and industry-sponsored research. Lancet 2000;356:635–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clemens F, Elbourne D, Derbyshire J, et al. Data monitoring in randomized controlled trials: surveys of recent practice and policies. Clin Trials 2005;2:22–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price DD, Finniss DG, Benedetti F. A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: recent advances and current thought. Annu Rev Psychol 2008;59:565–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaduszkiewicz H, Zimmermann T, Beck-Bornholdt H-P, et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors for patients with Alzheimer's disease: systematic review of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 2005;331:321–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seife C. Is drug research trustworthy? Sci Am 2012;307:56–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roseman M, Milette K, Bero LA, et al. Reporting of conflicts of interest in meta-analyses of trials of pharmacological treatments. JAMA 2011;305:1008–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenberg SM, Tennis MK, Brown LB, et al. Donepezil therapy in clinical practice: a randomized crossover study. Arch Neurol 2000;57:94–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazza M, Capuano A, Bria P, et al. Ginkgo biloba and donepezil: a comparison in the treatment of Alzheimer's dementia in a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:981–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winstein CJ, Bentzen KR, Boyd L, et al. Does the cholinesterase inhibitor, donepezil, benefit both declarative and non-declarative processes in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease? Curr Alzheimer Res 2007;4:273–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmes C, Wilkinson D, Dean C, et al. The efficacy of donepezil in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2004;63:214–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maher-Edwards G, Dixon R, Hunter J, et al. SB-742457 and donepezil in Alzheimer disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:536–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers S, Farlow M, Doody R, et al. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Donepezil Study Group. Neurology 1998;50:291–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers S, Doody R, Mohs R, et al. Donepezil improves cognition and global function in Alzheimer disease: a 15-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1021–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seltzer B, Zolnouni P, Nunez M, et al. Efficacy of donepezil in early-stage Alzheimer disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Neurol 2004;60:1852–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.