Abstract

Objectives

China has experienced a sharply increasing rate of human brucellosis in recent years. Effective spatial monitoring of human brucellosis incidence is very important for successful implementation of control and prevention programmes. The purpose of this paper is to apply exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) methods and the empirical Bayes (EB) smoothing technique to monitor county-level incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China from 2004 to 2010 by examining spatial patterns.

Methods

ESDA methods were used to characterise spatial patterns of EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis based on county-level data obtained from the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP) in mainland China from 2004 to 2010.

Results

EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis were spatially dependent during 2004–2010. The local Moran test identified significantly high-risk clusters of human brucellosis (all p values <0.01), which persisted during the 7-year study period. High-risk counties were centred in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and other Northern provinces (ie, Hebei, Shanxi, Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces) around the border with the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region where animal husbandry was highly developed. The number of high-risk counties increased from 25 in 2004 to 54 in 2010.

Conclusions

ESDA methods and the EB smoothing technique can assist public health officials in identifying high-risk areas. Allocating more resources to high-risk areas is an effective way to reduce human brucellosis incidence.

Keywords: Human brucellosis, exploratory spatial data analysis, empirical Bayes smoothing, spatial autocorrelation, cluster detection

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Exploratory spatial data analysis methods and the empirical Bayes smoothing technique were used to analyse spatial patterns of incidence rates for human brucellosis at the county level in mainland China. Therefore, random variability was reduced, and greater stability of incidence rates was provided mainly in small counties and true cluster areas with low false-positive rates performing especially well on outlier detection had a better chance of being detected.

The number of reported cases of human brucellosis obtained from the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP) system might be only part of the actual incidence of human brucellosis across the country as human brucellosis is often under-reported or misdiagnosed.

Our analyses are based on county-level data. Smaller spatial units might provide more location-specific information about the design and implementation stages of public health programmes.

Introduction

Brucellosis, caused by Brucella species, is a zoonotic disease recognised as an emerging and re-emerging threat to public and veterinary health.1 The disease is transmitted to humans by direct/indirect contact with infected animals or through the consumption of contaminated foods.2–4 People with occupational exposure are at highest risk for brucellosis, in particular those performing husbandry activities, butchering and livestock trading.5 6 Worldwide economic losses caused by brucellosis are extensive not only in animal production but also in public health.1 Although brucellosis has been eradicated from many industrialised countries, new foci of disease appear continually, particularly in parts of Asia.7

Brucellosis is classified as one of the class II national notifiable diseases by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and as a key disease in class II by the Implement Detailed Rules of the By-law on Disease Prevention and Control of Livestock and Poultry in mainland China.8 The disease was first reported in China in 1905.8 Human brucellosis incidence was quite severe before the 1980s in the country; it decreased later and remained at a low level. From 1995 to 2001, the incidence of human brucellosis increased rapidly and spread to more than 10 provinces.8 In recent years, with the rapid development of China’s animal husbandry, human brucellosis incidence had increased sharply.9 Nationwide surveillance data indicated that the total incidence rate of human brucellosis in mainland China increased from 0.92 cases/100 000 people in 2004 to 2.62 cases/100 000 people in 2010.10 Currently, human brucellosis is considered an important public health problem in mainland China.11

The incidence rates of human brucellosis are not evenly distributed across regions in China.10 Awareness of the spatial patterns of human brucellosis is quite beneficial for the prevention and control of the disease. Exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) methods are emerging as useful approaches to achieve this understanding.12 ESDA is a set of techniques used to describe and visualise spatial distributions, identify atypical locations or spatial outliers, discover patterns of spatial association, clusters or hot spots, and suggest spatial regimes or other forms of spatial heterogeneity.12 13 The methods can be applied by health officials to monitor spatial variations in disease rates, which can assist health officials in designing more location-specific control and prevention programmes by taking into account global and local spatial influences.14 Measures of spatial autocorrelation are at the core of ESDA methods.13 ESDA methods and the empirical Bayes (EB) smoothing technique are commonly combined to characterise spatial epidemiology of diseases.14–17 The EB smoothing technique is used to reduce random variation and to provide greater stability of rates mainly in small areas associated with small populations.16

The primary purpose of this paper is to apply ESDA methods and the EB smoothing technique to monitor county-level incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China from 2004 to 2010 by examining spatial patterns. Thus, we also identified the potential presence of clusters of the disease in mainland China to provide spatial guidance for future research.

Methods

Data source

Human brucellosis cases including 2872 counties in mainland China from 2004 to 2010 were collected through the Internet-based disease-reporting system (China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention, CISDCP), which was established in 2004 and was more integrated, effective and reliable than the previous case-reporting system.18 19 In mainland China, human brucellosis is a reportable disease. Suspected or confirmed cases must be reported to local and provincial CDC and then to Chinese CDC (CCDC). To meet case definitions, disease in persons must not only be accompanied by clinical signs, but must also be confirmed by serological tests or in isolation in accordance with the case definition of the WHO.20

In this paper, the incidence rates of human brucellosis in fact referred to the reported incidence rates. In order to conduct a geographic information system (GIS)-based analysis of the spatial distribution of human brucellosis, the county-level polygon map at a 1:1000000 scale was obtained.21 Demographic information from 2004 to 2010 was acquired from the National Bureau of Statistics of China. All human brucellosis cases were geocoded and matched to the county-level layers of the polygons by administrative code using the software Mapinfo V.7.0.21

EB smoothing technique

When raw rates derived from different counties across the whole study area are applied to estimate the underlying disease risk, differences in population size result in variance instability and spurious outliers. This is because the rates observed in areas with small populations may be highly unstable in that the addition or deletion of one or two cases can cause drastic changes in the observed values. Therefore, raw rates may not fully represent the relative magnitude of the underlying risks if compared with other counties with a high population base. To overcome this problem, the EB smoothing technique proposed by Clayton and Kaldor16 was applied to our brucellosis data. This method adjusts raw rates by incorporating data from other neighbouring spatial units.22 Essentially, raw rates get ‘shrunk’ towards an overall mean, which is an inverse function of the variance. Application of the EB smoothed incidence rate not only provides better visualisation compared with the raw rate but also serves to find true outliers.23

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

We performed spatial autocorrelation analysis in GeoDa V.0.9.5-i software.24 Global and local Moran's I statistics were calculated. The global Moran’s I statistic was estimated to assess the evidence of global spatial autocorrelation (clustering) of incidence rates over the study region.25 Anselin’s26 local Moran’s I (local indicators of spatial association (LISA)) statistic indicates the location of local clusters and spatial outliers. Spatial autocorrelation statistics for human brucellosis incidence rates were calculated based on the assumption of constant variance. The assumption might be violated when incidence rates at the county level varied greatly across the whole study region.27 The EB smoothing technique was performed to adjust for this violation. The standardised first-order contiguity Queen neighbours were used as the criteria for identifying neighbours in this paper. A significant test was performed through the permutation test, and a reference distribution was generated under an assumption that the incidence was randomly distributed. In order to obtain more robust results, the number of the permutation test was set to 9999. Since multiple comparisons increased the chances of identifying overlapping clusters, the significance level was set at 0.01. Based on these permutations and threshold, we have plotted values on a map to display the location of human brucellosis clusters in mainland China.28

Results

Annualised average of human brucellosis from 2004 to 2010

A total of 164 752 human brucellosis cases were reported in mainland China from 2004 to 2010. Annual EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis for all 2872 counties were calculated. Table 1 presents annual EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis over 100 cases/100 000 people in 28 counties, which accounted for 34.41% of all cases in the country during the study period. Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region had the highest number of 23, centred in Xilin Gol League, Ulanqab League, Hulunbeier City, Xing’an League, Baotou City, Chifeng City, Hohhot City and Tongliao City.

Table 1.

Counties with annual empirical Bayes (EB) smoothed incidence rates of human brucellosis over 100/100 000 in mainland China, 2004–2010

| No. | Province | City | County | Rate* | z-value | p Value | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inner Mongolia | Xilin Gol League | Sunitezuo Banner | 1209.60 | 31.16 | <0.001 | 1 |

| 2 | Abag Banner | 1004.10 | 25.85 | <0.001 | 2 | ||

| 3 | Bordered Yellow Banner | 826.90 | 21.27 | <0.001 | 3 | ||

| 4 | Plain Blue Banner | 364.40 | 9.30 | <0.001 | 4 | ||

| 5 | Zhenxianghuang Banner | 303.70 | 7.73 | <0.001 | 5 | ||

| 6 | Sunite Right Banner | 294.60 | 7.50 | <0.001 | 6 | ||

| 7 | West Ujimqin Banner | 243.50 | 6.18 | <0.001 | 9 | ||

| 8 | Xilinhot City | 236.80 | 6.00 | <0.001 | 10 | ||

| 9 | East Ujimqin Banner | 219.00 | 5.54 | <0.001 | 11 | ||

| 10 | Duolun County | 176.70 | 4.45 | <0.001 | 15 | ||

| 11 | Ulanqab League | Siziwang Banner | 257.90 | 6.55 | <0.001 | 7 | |

| 12 | Huade County | 179.00 | 4.51 | <0.001 | 14 | ||

| 13 | Qahar Right Wing Rear Banner | 163.90 | 4.12 | <0.001 | 16 | ||

| 14 | Shangdu County | 142.40 | 3.56 | <0.001 | 20 | ||

| 15 | Chahar Right Middle Banner | 128.80 | 3.21 | <0.002 | 23 | ||

| 16 | Hulunbeier City | New Barhu Right Banner | 255.10 | 6.48 | <0.001 | 8 | |

| 17 | New Barhu Left Banner | 203.40 | 5.14 | <0.001 | 13 | ||

| 18 | Zhalantun City | 144.20 | 3.61 | <0.001 | 19 | ||

| 19 | Xing'an League | Horqin Right Wing Front Banner | 146.00 | 3.66 | <0.001 | 18 | |

| 20 | Baotou City | Daerhanmaomingan Union Banner | 129.80 | 3.24 | <0.002 | 22 | |

| 21 | Chifeng City | Keshiketeng Banner | 126.50 | 3.15 | <0.002 | 24 | |

| 22 | Hohhot City | Qingshuihe County | 123.90 | 3.08 | <0.005 | 25 | |

| 23 | Tongliao City | Jarud Banner | 104.90 | 2.59 | <0.010 | 28 | |

| 24 | Shanxi | Datong City | Tianzhen County | 162.30 | 4.08 | <0.001 | 17 |

| 25 | Guangling County | 136.50 | 3.41 | <0.001 | 21 | ||

| 26 | Xinzhou City | Shengchi County | 107.70 | 2.67 | <0.010 | 27 | |

| 27 | Heilongjiang | Qiqihar City | Meris Daur District | 208.10 | 5.26 | <0.001 | 12 |

| 28 | Hebei | Zhangjiakou City | Chicheng County | 117.60 | 2.92 | <0.005 | 26 |

*These are annual empirical Bayes (EB) smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis.

Summary statistics for the annual EB smoothed incidence rates for all counties were calculated. The mean and SD were 4.64 and 38.66, respectively, per 100 000 people. The statistic for outliers was the computed z-value, which was the difference between the observed and expected mean of the annual EB smoothed incidence rates standardised by the SD. Thus, it had mean 0 and SD 1. Sunitezuo Banner in Xilin Gol League in Inner Mongolia had the highest annual EB smoothed incidence rate of 1209.60, with 31.16 SDs from the mean. All 28 counties were at least 2.59 SDs from the mean, as shown in table 1.

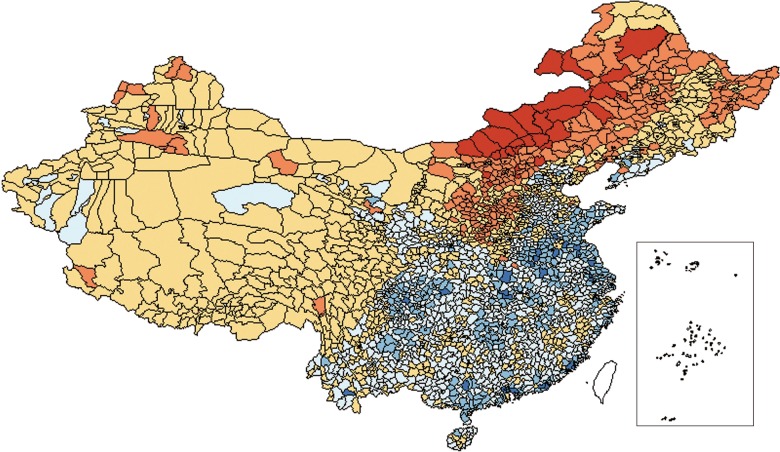

Figure 1 presented a percentile map of annual EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China by county from 2004 to 2010. The figure gives an indication of spatial associations: counties with similar colour shades tended to be near each other. Outlier counties with extreme values were highlighted (high as well as low). Six legend categories were created, corresponding to <1%, 1% to <10%, 10% to <50%, 50% to <90%, 90% to <99% and >99%. There were 29 counties at the high end.

Figure 1.

Percentile map of annual empirical Bayes (EB) smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China by county, 2004–2010.

The global Moran’s I value of annual EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China by county from 2004 to 2010 was 0.5803 (z=8.3660, p=0.0025), statistically significant at the 0.01 level.

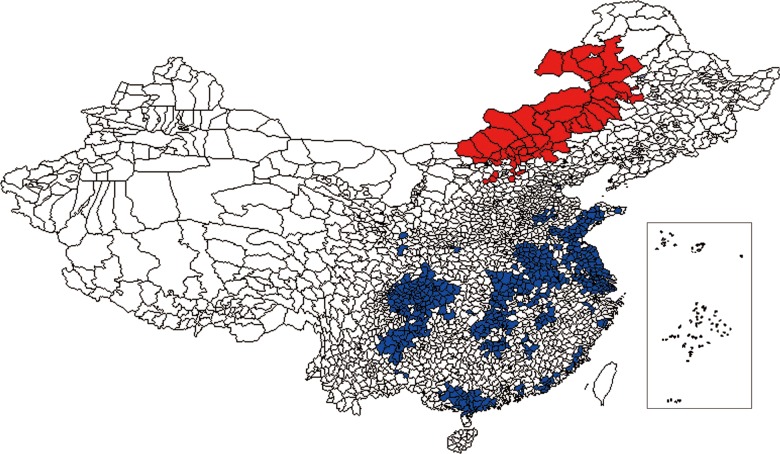

We also calculated the local Moran’s I and gave a LISA cluster map of annual EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China by county from 2004 to 2010. The LISA cluster map showed those counties with a significant local Moran statistic classified by type of spatial correlation: bright red for the high–high association, bright blue for low–low, light blue for low–high and light red for high–low (figure 2). The high–high and low–low locations suggest a clustering of similar values, whereas the high–low and low–high locations indicate spatial outliers.

Figure 2.

Local indicators of spatial association (LISA) cluster map of annual empirical Bayes (EB) smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China by county, 2004–2010.

The local Moran’s I method of annual EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis showed major high-risk clustered areas of human brucellosis located in northern China. High-risk counties were centred in Inner Mongolia (40 counties, 72.3%), Hebei (7 counties, 12.7%), Shanxi (5 counties, 9.1%), Heilongjiang (2 counties, 3.6%) and Jilin provinces (1 county, 1.8%) and included a total of 55 counties. These provinces accounted for 90.88% of the reported cases. EB smoothed incidence rates for these counties ranged from 7.70 to 1209.60 cases/100 000 people.

Changes in human brucellosis incidence rates from 2004 to 2010

The value of global Moran's I of EB smoothed incidence rates increased from 0.2460 to 0.6179 during 2004–2010, indicating that the spatial distribution of human brucellosis had become more uneven (ie, the clustering of high and low values is becoming more prominent; table 2). The formal test of spatial dependence was statistically significant at the 0.01 level, implying that distribution of human brucellosis was spatially dependent in mainland China.

Table 2.

Global spatial autocorrelation analyses for empirical Bayes (EB) smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China (per year), 2004–2010

| Year | Moran's I | z-score | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 0.2460 | 4.7733 | 0.0087 |

| 2005 | 0.4734 | 9.0229 | 0.0012 |

| 2006 | 0.4662 | 7.6853 | 0.0026 |

| 2007 | 0.5063 | 7.3102 | 0.0042 |

| 2008 | 0.5594 | 8.4932 | 0.0025 |

| 2009 | 0.5509 | 8.3389 | 0.0020 |

| 2010 | 0.6179 | 11.1187 | 0.0002 |

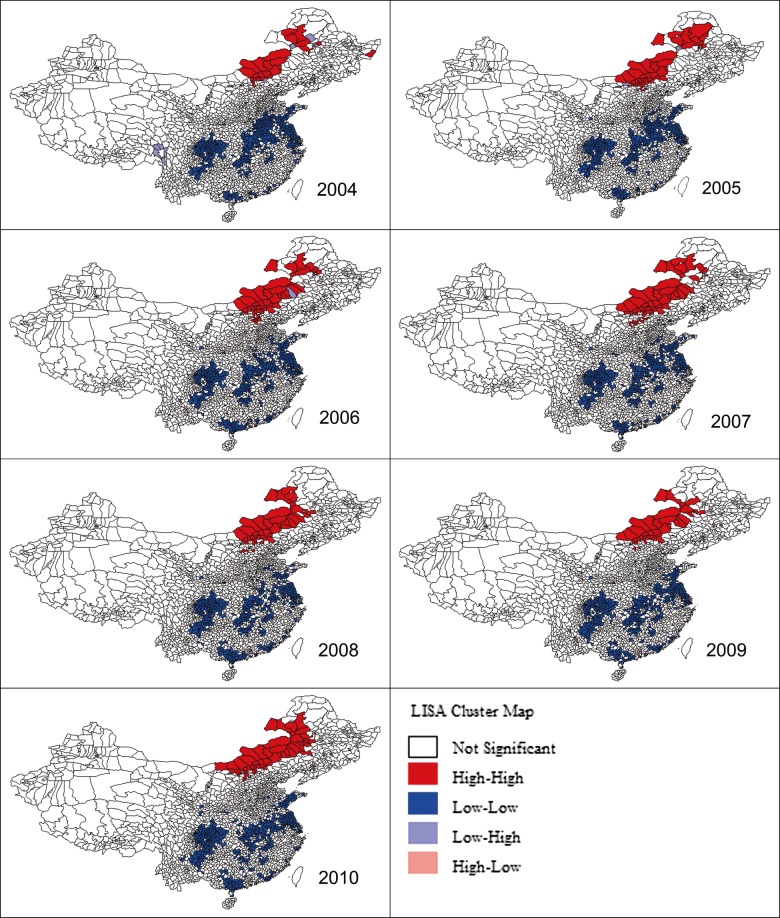

The clustered areas varied during the 7-year study period (figure 3). The number of high-risk counties—that is, those counties included in clustered areas of high human brucellosis risk identified by the local Moran’s I method—increased from 25 in 2004 to 54 in 2010.

Figure 3.

Local indicators of spatial association (LISA) cluster maps of empirical Bayes (EB) smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis in mainland China by county (per year), 2004–2010.

The number of high-risk counties in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region was the largest one, increasing from 22 in 2004 to 46 in 2010. Among the 101 counties in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, the number of EB smoothed incidence rates over 100 cases/100 000 people increased from 8 in 2004 to 29 in 2010. The most notable change was that the EB smoothed incidence rate in Sunitezuo Banner increased from 373.7 in 2004 to 2482.1 in 2009, but then decreased to 1443.0 cases/100 000 people in 2010.

In Hebei Province, the number of high-risk counties kept an upward trend, rising from one in 2004 to three in 2010. The most noteworthy change was that the EB smoothed incidence rate in Wei County increased from 9.70 to 79.40 cases/100 000 people between 2004 and 2010.

The number of high-risk counties in Shanxi Province increased from zero in 2004 to two in 2010. The most notable change was that the EB smoothed incidence rate in Xinrong District increased from 0.9 to 88.1 cases/100 000 people between 2004 and 2010.

In Jilin Province, the number of high-risk counties increased from zero in 2004 to three in 2010. The most notable change was that the EB smoothed incidence rate in Tongyu County increased from 0 to 155.6 cases/100 000 people between 2004 and 2010.

In Heilongjiang Province, the number of high-risk counties decreased from two to zero between 2004 and 2010. Meris Daur District had the highest EB smoothed incidence rates of human brucellosis in the province, at more than 130 cases/100 000 people per year between 2004 and 2010. The most notable change was that the EB smoothed incidence rate in Zhaozhou County increased from 1.3 to 74.2 cases/100 000 people between 2004 and 2010.

Discussion

In this paper, ESDA methods were used to explore spatial patterns of EB smoothed incidence rates for human brucellosis at the county level in mainland China from 2004 to 2010. We found that the occurrence of human brucellosis persisted throughout many areas of the country and was spatially dependent during the 7-year study period. Since human brucellosis is not a contagious disease, spatial clusters of human brucellosis are most likely a result of animal processing, shared food sources, more intensive agricultural production zones or similar sociocultural practices.17 29 Further researches are needed to determine whether human brucellosis clusters in China are associated with specific natural and/or social environmental characteristics. During the period 2004–2010, the areas with serious epidemics of human brucellosis persisted in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and other Northern provinces (ie, Hebei, Shanxi, Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces) around the border with the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region where animal husbandry had developed, all of which were epidemic regions before the 1980s. This spatial pattern may be related to the transboundary transfer of animal brucellosis in the region of Inner Mongolia from the neighbouring hyperendemic Mongolia, which had been described as the country with the second highest incidence worldwide.7 30 In addition, the leading risk factors for the high incidence rate of human brucellosis were the increase in animal feeding, lack of immunisation and animal quarantine, and frequent trading.9 30

Several intervention strategies had been suggested to reduce the incidence of human brucellosis, such as increasing local knowledge of proper food handling techniques of dairy products including pasteurisation, decreasing occupational exposures, quarantining, separating and eliminating infected animals with brucellosis, establishing surveillance points of brucellosis and its network, and vaccination programmes aimed at reducing the prevalence of disease in livestock.8 31 However, Zhang9 suggested that the most effective means of human brucellosis control were the comprehensive measures of universal immunisation in livestock without quarantine in epidemic regions, which had been proved to be effective measures.

A previous study analysed cluster identification of the annualised raw incidence rates of county-level human brucellosis in China by using SaTScan and ArcGIS software.32 Our work is very different from the previous study. First, we used the EB smoothing technique to smooth the human brucellosis incidence rates. Therefore, random variability was reduced and a greater stability of incidence rates was provided mainly in small counties. Second, although the previous study and our work analysed county-level human brucellosis cases in mainland China from 2004 to 2010, the previous study performed cluster detection by using 7-year average human brucellosis cases which merely reflected the average spatial aggregation. In this paper, we performed the cluster detection year by year by using the annual human brucellosis cases from 2004 to 2010 which fully reflected the year-by-year changes in spatial pattern of human brucellosis incidence rates from 2004 to 2010. Third, compared with the spatial scan statistic, LISA has a better chance of detecting true cluster areas, with low false-positive rates performing especially well on outlier detection.33 This is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, which has applied ESDA methods and the EB smoothing technique to analyse spatial patterns of incidence rates for human brucellosis at the county level in mainland China. We believe that conclusions on the basis of the combinations of the two methods provide reliable results. The results of these two methods differed slightly and complemented each other. In addition, the previous study is just a letter, the results of which are very simple and rough and provided very limited information.

Our study is not without limitations. First of all, the number of reported cases of human brucellosis obtained from the CISDCP system might be only part of the actual incidence of human brucellosis across the country as human brucellosis is often under-reported or misdiagnosed.30 The true human brucellosis rates might be much higher than reported. Nevertheless, the data used in this paper are still able to reflect the current trend in human brucellosis incidence in mainland China. Second, the cross-organisational collaboration (between public health, clinics and hospitals) has been very efficient within the healthcare system. However, information sharing between healthcare organisations and non-health departments, such as the government's agriculture department, has not been extensive. Currently, animal and human health disease surveillance databases are not linked. Additionally, we cannot obtain the data of animal brucellosis because of confidentiality restrictions.18 Therefore, we did not analyse the density of livestock compared with the distribution of human cases. Furthermore, our analyses are based on county-level data. Smaller spatial units might provide more location-specific information about the design and implementation stages of public health programmes.14 The methods employed in this paper can be applied to finer geographic units (eg, postal units). Thus smaller spatial units within counties with higher burdens of human brucellosis would be focused on to obtain more location-specific information in further research.

In conclusion, our study offered a good understanding of the spatial patterns of human brucellosis incidence in mainland China, and might help to determine allocating resources to high-risk areas with the goal of reducing human brucellosis incidence. With the assistance of the spatial framework provided by our study, China’s human brucellosis control programmes could be focused on locations where they will have the greatest influence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JZ designed the research, collected the data, drafted the manuscript, analysed the data and interpreted the results. FY designed the research, collected the data, interpreted the results and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. TZ, CY and XZ interpreted the results and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. XL designed the research, interpreted the results, critically reviewed the manuscript and supervised the whole study process. ZH offered research data and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Infectious Disease Surveillance Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (No.2012ZX10004201) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30571618).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Seleem MN, Boyle SM, Sriranganathan N. Brucellosis: a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Microbiol 2010;140:392–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Massis F, Di Girolamo A, Petrini A, et al. Correlation between animal and human brucellosis in Italy during the period 1997–2002. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005;11:632–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marianelli C, Graziani C, Santangelo C, et al. Molecular epidemiological and antibiotic susceptibility characterization of Brucella isolates from humans in Sicily, Italy. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:2923–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memish ZA, Balkhy HH. Brucellosis and international travel. J Travel Med 2004;11:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Man TF, Wang D, Cui B, et al. Analysis on surveillance data of brucellosis in China, 2009. Dis Surveill 2010;25:944–6 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim HS, Min YS, Lee HS. Investigation of a series of brucellosis cases in Gyeongsangbuk-do during 2003–2004. J Prev Med Public Health 2005;38:482–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pappas G, Papadimitriou P, Akritidis N, et al. The new global map of human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:91–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shang D, Xiao D, Yin J. Epidemiology and control of brucellosis in China. Vet Microbiol 2002;90:165–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J. Reasons and prevention and control measures for the high brucellosis incidence. Dis Surveill 2010;25:341–2 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Yu X, He T. An analysis of brucellosis epidemic situation in humans from 2004 to 2010 in China. Chin J Control Endemic Diseases 2012;27:18–20 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao G, Xu J, Ke Y, et al. Literature analysis of brucellosis epidemic situation and research progress in China from 2000 to 2010. Chin J Zoonoses 2012;28:1178–84 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anselin L. Exploratory spatial data analysis and geographic information systems. In: New tools for spatial analysis. Luxemburg: EuroStat, 1994:19–33 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anselin L. Interactive techniques and exploratory spatial data analysis. In: Geographical information systems: principles, techniques, management and applications. New York: Wiley, 1999:251–64 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owusu Edusei K, Owens CJ. Monitoring county-level chlamydia incidence in Texas, 2004–2005: application of empirical Bayesian smoothing and exploratory spatial data analysis (ESDA) methods. Int J Health Geogr 2009;8:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martins-Melo FR, Ramos AN, Alencar CH, et al. Mortality of Chagas’ disease in Brazil: spatial patterns and definition of high-risk areas. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:1066–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clayton D, Kaldor J. Empirical Bayes estimates of age-standardized relative risks for use in disease mapping. Biometrics 1987;43:671–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdullayev R, Kracalik I, Ismayilova R, et al. Analyzing the spatial and temporal distribution of human brucellosis in Azerbaijan (1995–2009) using spatial and spatio-temporal statistics. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Wang Y, Yang G, et al. China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP). http://www.pacifichealthsummit.org/downloads/HITCaseStudies/Functional/CISDCP.pdf (accessed 26 Jan 2013)

- 19.Cao M, Feng Z, Zhang J, et al. Contextual risk factors for regional distribution of Japanese encephalitis in the People's Republic of China. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:918–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Guo W, Sun S, et al. Human brucellosis, Inner Mongolia, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16:2001–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin F, Feng Z, Li X. Spatial analysis of primary and secondary syphilis incidence in China, 2004–2010. Int J STD AIDS 2012;23:870–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maguire DJ, Batty M, Goodchild MF. GIS, spatial analysis and modelling. Redlands, CA: ESRI, 2005:93–111 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anselin L, Lozano N, Koschinsky J. Rate transformations and smoothing. Urbana 2006;51:61801 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anselin L. Exploring spatial data with GeoDaTM: a workbook. Urbana 2004;51:61801 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anselin L, Syabri I, Kho Y. GeoDa: an introduction to spatial data analysis. Geographical Anal 2006;38:5–22 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anselin L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geographical Anal 1995;27:93–115 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang L, Yan L, Liang S, et al. Spatial analysis of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China. BMC Infect Dis 2006;6:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dewan AM, Corner R, Hashizume M, et al. Typhoid fever and its association with environmental factors in the Dhaka metropolitan area of Bangladesh: a spatial and time-series approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7:e1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fosgate GT, Carpenter TE, Chomel BB, et al. Time-space clustering of human brucellosis, California, 1973–1992. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:672–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong Z, Yu S, Wang X, et al. Human brucellosis in the People's Republic of China during 2005–2010. Int J Infect Dis 2013;17:289–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Shamahy H, Whitty C, Wright S. Risk factors for human brucellosis in Yemen: a case control study. Epidemiol Infect 2000;125:309–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Z, Zhang W, Ke Y, et al. High-risk regions of human brucellosis in China: implications for prevention and early diagnosis of travel-related infections. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:330–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson MC, Huang L, Luo J, et al. Comparison of tests for spatial heterogeneity on data with global clustering patterns and outliers. Int J Health Geogr 2009;8:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.