Abstract

Introduction

Interventions to improve adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) are necessary to improve treatment completion rates and optimise tuberculosis (TB) control efforts. The high prevalence of cell phone use presents opportunities to develop innovative ways to engage patients in care. A randomised controlled trial (RCT), WelTel Kenya1, demonstrated that weekly text messages improved antiretroviral adherence and clinical outcomes among patients initiating HIV treatment. The aim of this study is to determine whether the WelTel intervention can improve treatment completion among patients with LTBI and to evaluate the intervention's cost-effectiveness.

Methods and analysis

This open, two-site, parallel RCT (WelTel LTBI) will be conducted at TB clinics in Vancouver and New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada. Over 2 years, we aim to recruit 350 individuals initiating a 9-month isoniazid regimen. Participants will be randomly allocated to an intervention or control (standard care) arm in a 1:1 ratio. Intervention arm participants will receive a weekly text-message ‘check-in’ to which they will be asked to respond within 48 h. A TB clinician will follow-up instances of non-response and problems that are identified. Participants will be followed until treatment completion (up to 12 months) or discontinuation. The primary outcome is self-reported treatment completion (taking ≥80% of doses within 12 months). Secondary outcomes include daily adherence (percentage of days participants used medication as prescribed) and time to treatment completion. Patient satisfaction with the intervention will be evaluated, and the intervention's cost-effectiveness will be analysed through decision-analytic modelling.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the University of British Columbia. This trial will test the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the WelTel intervention to improve treatment completion among patients with LTBI. Trial results and economic evaluation will help inform policy and practice on the use of WelTel in this population.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01549457.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first known trial protocol to assess the effect of a mobile health text-messaging intervention to improve treatment completion among individuals with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI).

Self-report will be used to measure adherence, rather than direct observation or electronic monitoring.

The WelTel LTBI trial will only be conducted at two sites in British Columbia; generalisability to other settings may be limited.

Introduction

The WHO estimates that in 2011 there were 8.7 million new cases of tuberculosis (TB) worldwide and 1.4 million deaths from TB.1 Despite being treatable and preventable, TB poses a significant threat to public health in Canada. Approximately 70% of the 1500 annual incident cases of TB in Canada occur in foreign-born persons as a result of reactivation of a dormant infection acquired in their country of origin prior to immigration.2 3 Treatment of latent TB infection (LTBI) can prevent progression to active TB and is a key component of TB control and elimination efforts. Standard treatment is isoniazid (INH) taken once daily for 9 months, which has an efficacy of 90% if patients complete treatment.4 Early treatment discontinuation and incomplete adherence are common and substantially limit treatment efficacy and cost-effectiveness.5 In routine practice, less than 50% of patients with LTBI complete treatment, reducing the effectiveness of this approach.6 7 Reasons for non-completion include the long course of treatment, lack of perceived disease and drug-related adverse events.6 8 9 Social support has been positively associated with LTBI treatment adherence.10

The global expansion in cell phone use presents new opportunities to incorporate mobile phones into health service delivery to help engage patients in care and treatment. The original WelTel Kenya1 study sought to capitalise on this increase in cell phone access to improve healthcare delivery, and through a multisite randomised controlled trial (RCT), demonstrated that the WelTel text-messaging intervention is effective in improving adherence to medication and clinical outcomes in individuals with HIV infection taking antiretroviral therapy.11

While the transfer of health innovation and technology has historically been unidirectional, from north to south, we are increasingly witnessing the bidirectional transfer of health technology. To determine the feasibility of adapting a Kenyan-born innovation to a Canadian environment in a new disease population, we first conducted a pilot study to assess healthcare provider and patient acceptability of the intervention, and to test the feasibility of using computer software to deliver the service. Study results indicated that patients with LTBI at the Vancouver clinic had the means to communicate with the clinic through text messaging and were receptive to doing so.12 Delivering the intervention via software was feasible, and the healthcare provider and patients felt that the programme was beneficial.12 It is unknown; however, whether WelTel is a clinically effective intervention to improve adherence to LTBI treatment. Other studies have been conducted to determine whether mobile phone text messaging improves TB treatment adherence13–15; however, a recent systematic review highlighted the paucity of high-quality research in this area and the need for further RCTs.16 This trial will examine the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the WelTel mobile health (mHealth) intervention to improve treatment completion among patients with LTBI.

Research hypothesis

The WelTel patient-centred text-message service is an efficacious and cost-effective strategy to improve treatment completion of 9 months of INH (9-INH) among patients with LTBI at British Columbia (BC) TB clinics.

Study objectives

Primary objective

Determine the effect of the WelTel intervention and usual care compared to usual care alone on treatment completion of 9-INH within 12 months of initiating treatment among patients with LTBI.

Key secondary objectives

Evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the WelTel intervention compared to usual care on treatment completion of INH among patients with LTBI.

Assess patient satisfaction with the WelTel intervention at the end of the intervention period (between 9 and 12 months).

Other secondary objectives

Determine the effect of the WelTel intervention and usual care compared to usual care alone on daily adherence, time to treatment completion, completion using a 90% adherence threshold and quality of life at 12 months.

Determine the effect of the WelTel intervention and usual care compared to usual care alone on completing ≥80% of doses within the first 6 months of INH treatment among patients with LTBI.

Determine whether the effect of the WelTel intervention differs among important subgroups (sex, age, phone access, distance from clinic and place of birth).

Methods and analysis

Trial design

WelTel LTBI is a two-site, two-arm, open, randomised, parallel-group study with a 1:1 allocation ratio.

Study setting

The trial will take place at two outpatient TB clinics: the Vancouver and New Westminster TB Control clinics, located in urban areas in BC, Canada. These clinics offer information, screening, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with active TB or LTBI. The provision of all treatment-related services is free of charge. The population these clinics serve is primarily foreign born (70%) and includes marginalised populations.15

Study population

The study population consists of adults aged 19 or over previously diagnosed with LTBI who are initiating LTBI treatment at the Vancouver or New Westminster TB clinics. Potential participants will be referred to a TB clinic nurse who will complete an eligibility checklist; individuals must fulfil all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria to participate.

Inclusion criteria

Initiating 9-INH treatment (300 mg daily) for LTBI;

19 years of age or older;

Own or share access to a cell phone;

Able to use simple text messaging in English, or have somebody (a partner, relative, etc) who can respond on their behalf;

Able and willing to provide informed consent to participate.

Exclusion criteria

Already started treatment for LTBI;

Initiating rifampin treatment (an alternative to INH for LTBI treatment);

Enrolled in another study that assesses or may influence treatment adherence.

Interventions

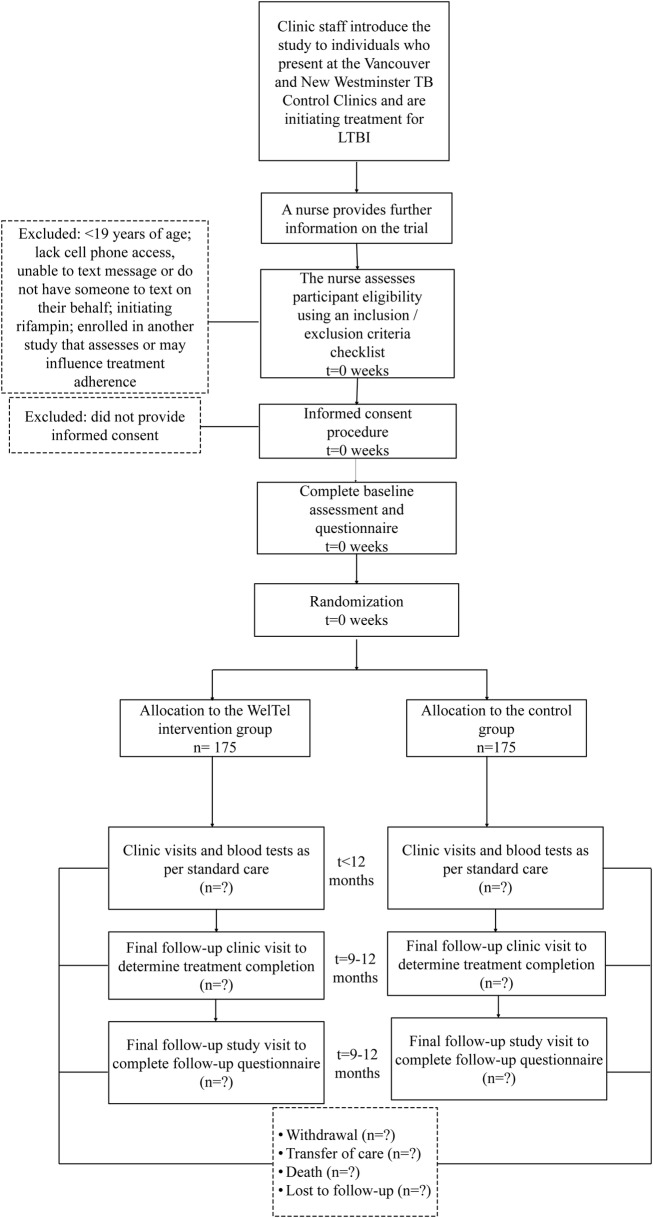

Participants will be randomly assigned to receive the WelTel text-messaging service in addition to usual care or to usual care alone. The WelTel intervention involves a weekly text message to check-in on how patients are doing and provide them with the opportunity to identify any issues or concerns that they may have (figure 1). On Monday at noon, an automated text message from a central computer at the clinic will be sent to intervention arm participants asking ‘Are you OK?’ Participants will be instructed to indicate within 48 h (ie, Wednesday of the same week) of receiving the message either that they are well (eg, yes) or that they have an issue to discuss (eg, no). A TB clinic nurse will review the incoming text messages on the central computer and call all participants who identify a problem. Those who do not respond within 48 h will receive a second text message stating ‘Haven't heard from you. How's it going?’ If the participant does not respond within 48 h (ie, by Friday), the TB nurse will call them to inquire as to their status. Participants who respond that they are OK will simply be sent another text message the following week. Participants will be informed that the text-message service supplements, but does not replace, existing clinical services and that all emergencies should be handled by usual means.

Figure 1.

The WelTel intervention illustrating how the patients and clinicians communicate on a weekly basis through the WelTel intervention.

Participants in the control and intervention groups will receive usual care for LTBI, which includes a 30-day supply of medication (daily INH 300 mg for 9 months), monthly complete blood cell count, liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) and clinic visits. Depending on the patient's tolerance of the first 3 months of medication, subsequent clinic visits may be scheduled more frequently or extended to every 2 months. At each clinic visit, the nurses or pharmacist will screen the patients for adverse events and ask the participants if they have missed any doses of their medication, and if so, the number of doses missed. Data on adherence and adverse events will be recorded in electronic clinic charts. Patients who experience adverse events will be referred to the TB physician for further evaluation and management; they may require a temporary treatment interruption, change to an alternate medication or discontinue treatment. All treatment changes will be recorded. At the final scheduled visit, participants will meet with the TB clinic physician and their TB treatment will be reviewed. At the discretion of the treating physician, participants who have had poor adherence or treatment interruptions may be recommended to continue treatment for a longer period of time. The study protocol will continue until treatment is deemed ‘complete’ or discontinued.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is treatment completion, defined as the proportion of participants who complete ≥80% of the prescribed INH doses within 12 months of initiating treatment. Completion of 80% of treatment is the conventional standard for assessing adherence in patients with LTBI.17 18 Adherence will be measured by patient self-report at each clinic visit (monthly (30-day adherence) or every 2 months (60-day adherence)).

Secondary outcomes

Number (percentage) of missed doses;

Treatment completion using a 90% threshold (taking 90% of doses within 12 months);

Time to treatment completion;

Quality of life using (SF12 questionnaire).19

Patient satisfaction with the WelTel intervention will be measured using Likert-type questions. A summary of primary and secondary outcomes and related hypotheses is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

WelTel LTBI: outcomes, measures and methods of analysis

| Outcome/variable | Hypothesis | Outcome measure | Method of analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Primary outcome | |||

| Treatment completion | Intervention>control | Completes ≥80% of prescribed INH in 12 months | χ2 test |

| 2. Secondary outcomes | |||

| (a) Adherence | Intervention>control | Mean (or median) number of doses taken | T test or Kruskal-Wallis test |

| (b) 90% treatment completion | Intervention>control | Completes >90% of prescribed INH in 12 months | χ2 test or Kruskal-Wallis test |

| (c) Time to treatment completion | Intervention>control | Time to INH completion | Kaplan-Meier survival analysis |

| (d) Quality of life | Intervention>control | SF12 PCS and MCS scores | t test |

| 3. Subgroup analyses | |||

| (a) Female vs male | Females>males | Regression methods with appropriate interaction term | |

| (b) Age | Younger>older | ||

| (c) Shared vs own phone | Own phone>shared phone | ||

| (d) Foreign-born | Non-foreign-born>foreign-born | ||

| (e) Distance from clinic | ≤1>1 h | ||

INH, isoniazid; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; MCS, mental composite score; PCS, physical composite score.

Sample size

The sample size required to achieve a power of 80% for a two-sided χ2 test at α=0.05 is 175 participants in each study arm. This calculation is based on finding a significant difference between the intervention and control arms in the primary outcome: the proportion of participants who complete LTBI treatment versus those who do not. The sample size estimate assumes that 72%15 of individuals in the control arm and 84% of individuals in the intervention arm will complete treatment. This difference is based on findings from a trial that examined the effect of the WelTel intervention on HIV treatment adherence.11 Sample size was calculated using IcebergSim software version beta 4.0.3 (Practihc Coordinating Office, Oslo, Norway), a clinical trial simulator using a Monte Carlo model with 5000 simulations.

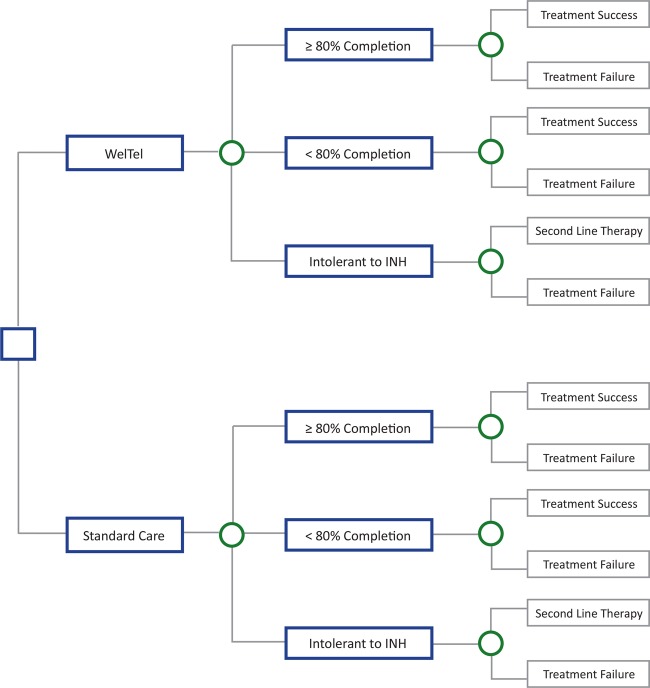

Recruitment

After standard clinical consultation with a TB physician, patients who decide to initiate LTBI therapy will be informed of the study by their physician or the clinic nurse (figure 2). Posters and pamphlets at the clinics will also inform potential participants of the study. If an individual expresses interest in participating, the clinic nurse will explain the trial in further detail. The nurse will use a checklist to assess eligibility; eligible individuals will be invited to participate and informed consent will be sought. If a participant has a mobile phone but does not know how to text, the nurse will teach them. The research coordinator will maintain a recruitment log to document screened patients, their basic demographic details (gender and age) and reasons for declining participation. The coordinator will cross-check the log with the clinical surveillance database to ensure that all potential participants are being captured. The number of participants recruited will be reported to the research team and clinic nurse supervisors on a bi weekly basis.

Figure 2.

The flow of participants through the WelTel LTBI study. LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; TB, tuberculosis.

We expect to enrol 350 participants over a 2-year period. Participants will be reimbursed $C20 at each of the two visits during which they undergo study-specific procedures (baseline and end-of-study follow-up visit). During the consent process, the nurse will inform participants that they may withdraw from the study at any time for any reason without it affecting their medical care.

Randomisation and allocation

Randomisation of participants to the intervention or control arm will be at a 1:1 ratio, using a computer-generated randomisation list. Simple randomisation will be used. The individual responsible for sequence generation and allocation concealment will not be involved in the implementation of treatment assignments. Written allocation of assignments will be sealed in individual, sequentially numbered, non-resealable, opaque envelopes that will be distributed to the clinics in sufficient quantity to allocate to the targeted number of participants. After meeting inclusion criteria, consenting to participate and completing a baseline questionnaire, participants will be immediately assigned to the randomised study arm by the nurse who will open one of the sequentially numbered envelopes to determine allocation. Before opening the envelope, the participant's study ID number will be written on the envelope. The assignment schedule will be kept in a locked filing cabinet in the study coordinator's office at the BC Centre for Disease Control.

Blinding

Participating clinic staff and participants cannot be blinded because the intervention requires overt participation; however, the data analyst will be blinded to the study arm assignment.

Follow-up

Follow-up visits will occur as per routine clinical practice; each visit will be recorded in an electronic clinical chart. At each clinic visit, patients will be asked if they had missed any doses of medication since their last visit (30 or 60 days), and if so, how many were missed. The number of doses of medication missed will be recorded and used as a measure of self-reported adherence. Usual care includes monthly visits; however, after 3 months, the visit schedule may be modified depending on the patient's tolerability of INH. If a patient misses an appointment, a reception staff member calls them to reschedule. In the event of two consecutive missed appointments, a clinic nurse calls the patient to follow-up.

In the intervention and control groups, participants will complete a self-administered follow-up questionnaire during their final clinic visit. Frequently, the final clinic visit is scheduled at 8 months, at which time patients pick up their last 30-day prescription. In these cases, the research coordinator will call the patient at month 10 to determine if treatment has been completed, record any missed doses and administer the final study questionnaire. If the participant has not completed treatment at month 10, the coordinator contacts them again at month 12. Participants who have not returned to the clinic, officially discontinued their medication, and are not contactable by telephone after several attempts will be deemed lost to follow-up.

Data collection and management

Demographic and baseline clinical information will be extracted from the patients’ electronic clinical charts. Information regarding changes in treatment regimen, other medications, clinic visits and medication adherence will also be extracted from these charts. On study participants’ clinic visit dates, the study coordinator will enter relevant information in a separate Microsoft Excel password-protected database in a secure shared drive with limited access.

All cell phone communication resulting from the text-message queries will be recorded by the WelTel software. The clinic nurse will manually record attempts to contact participants and instances of voice call communication resulting from participant follow-up in a call log. The nurse will document reasons participants responded with issues, reasons they did not respond and any actions taken. The data manager will enter data from the communications log into SPSS weekly.

Questionnaire and other study-related data will be paper-based and entered into an SPSS database at the BC Centre for Disease Control by the data manager. The baseline questionnaire will collect information on demographic characteristics, substance use, cell phone use and attitudes towards LTBI treatment. The final questionnaire will collect information on hospitalisations, clinic visits outside of standard clinic visits, patient experiences with treatment and communication with their healthcare providers. Intervention arm participants will also be asked, using Likert-type questions, about their experience with the intervention. Overall health-related quality of life will be measured at baseline and end of study with the SF12.19

The data manager will check all forms for completeness. Data processing will include range and consistency checks. Any queries will be resolved promptly. Data quality will be verified by rechecking a random sample of 10% of data collected. Hardcopies of participant files including consent forms and questionnaires will be stored in a locked cabinet in the study coordinator's office at the BC Centre for Disease Control.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics of participants’ baseline characteristics will be presented to assess their comparability. These statistics will be reported as a mean (SD) or median (first quartile, third quartile) for continuous variables, and count (%) for categorical variables. Baseline characteristics will include: gender, age, education, income, place of birth, substance use, cell phone access, reason for treatment and comorbidities.

For the primary analysis, we will compare the proportion of participants who complete treatment in the intervention group with those in the control group using a χ2 test (table 1). Our analysis will be intention to treat; therefore, we will include all randomised patients according to the study group to which they were originally allocated regardless of subsequent intervention received. Results will be reported as the number of participants (with percentages) for each study arm, the relative risk with 95% CIs and p values. We will also calculate the number needed to treat for the primary outcome. Secondary binary outcomes will be similarly analysed. For other types of secondary outcomes, we will use t tests for normally distributed continuous variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for non-normally distributed variables. For time-to-event outcomes, we will analyse data with the Kaplan-Meier approach and Cox proportional hazards model.

Subgroup analyses will be performed by conducting the statistical analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes within predetermined subgroups of patients. These include: sex (men vs women), age (19–29, 30–39, 40–49 and ≥50 years of age), phone access (own phone vs shared), distance from clinic (≤1 vs >1 h) and place of birth (born outside vs in Canada). Subgroups were selected because of potential heterogeneity in the risks for treatment incompletion (with those farther from clinic and born outside of Canada less likely to complete treatment)20 and potential variance in the effect of the intervention resulting from underlying differences between groups of patients in adopting a cell phone intervention due to differences in cell phone use (sex, age and phone access).21 We will assess whether the intervention effect is homogeneous across these subgroups by including an interaction term between the intervention allocation and subgroup-defining variables in the model. p Values for the interaction tests, rather than the treatment effect within groups, will be calculated. We will report all subgroup results, regardless of significance.

Missing data will be handled using multiple imputation methods. The criterion for statistical significance will be set at α=0.05. The results will be reported as estimates of the effect, corresponding to 95% CI and associated p values. p Values will be reported to three decimal places with those less than 0.001 reported as p<0.001. Data will be analysed with up-to-date versions of Stata statistical software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Data monitoring

This trial does not have a data and monitoring committee for the following reasons: the study is minimal risk, LTBI is a non-life-threatening infection, there were no issues in previous studies of the intervention and the nature of the study population (adult, not considered vulnerable).

Harms

All adverse events occurring after enrolment until study exit will be reported. Adverse events include those directly attributable to the intervention, such as accidental disclosure of TB status, and those resulting from participation in the trial. Potential harms will be outlined during the informed consent process and potential participants will be notified about whom these events should be reported to. An adverse event report form based on standard forms of the relevant institutional review boards (IRBs) will be used as a reporting tool. The nurse will document any adverse events that occur in a weekly study log and during follow-up visits with participants. Healthcare staff will undergo training with respect to the recognition and reporting of adverse events. Adverse events and unanticipated problems will be promptly reported to the appropriate officials in accordance with IRB regulations and reported using descriptive statistics.

Cost-effectiveness evaluation

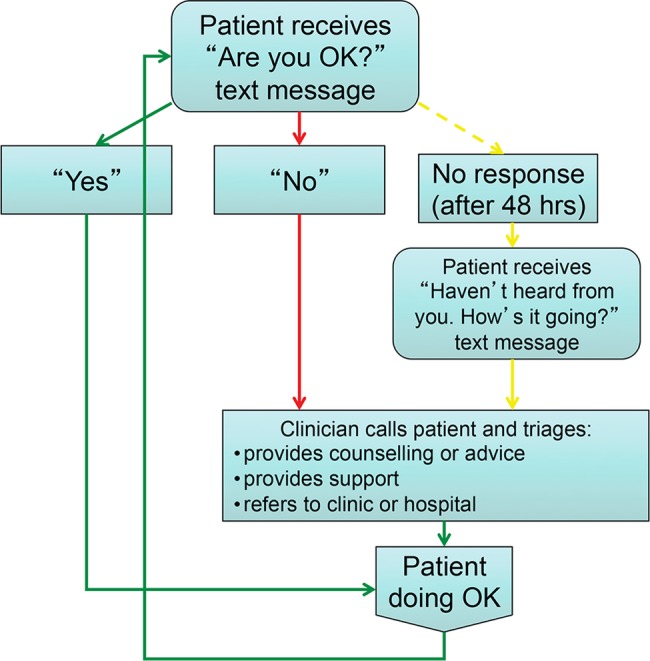

A cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) will incorporate trial data along with current evidence in TB pathophysiology and treatment to describe the value of potential clinical improvements made by WelTel. An improved rate of treatment completion can prevent additional healthcare costs such as extra clinic visits, mortality and complications from progression to active TB, and prolonged drug therapy or switching to costlier second-line drug therapy. The primary outcome of the CEA will be the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained through improvement in rates of treatment success. A secondary analysis will consider the cost per additional completion of treatment regimen. Reflecting these long-term benefits beyond the trial period will require the use of a simulation model to map the impact of the intervention on primary (treatment completion) and secondary outcomes (adherence and resource use) to long-term impact on costs and effectiveness. Such a model will transform the impact of the intervention into lifetime costs and QALYs.

A decision tree (figure 3) will describe the costs and benefits during the 12-month trial period that arise from a differential rate of treatment completion by the intervention and control arms. A third party payer perspective will be used to track costs including direct medical costs such as labour, text messages used, average length of patient calls, medications, use of health services (hospital and pharmacy) and clinic visits. WelTel software will collect data such as frequency of text messages as well as types of problems and number of calls that require clinician follow-up. In order to conduct a secondary analysis from a societal perspective, non-medical costs such as patient spending on over-the-counter medications, costs incurred receiving and sending text messages and extra travel time or upkeep will be collected through surveys administered to patients. Indirect costs such as absenteeism from work due to illness and additional clinic visits will also be collected through survey data. All costs and QALYs derived from the models will be discounted at 3%. For patients who are not successfully treated within the 12-month time frame, costs and outcomes beyond the trial period will be estimated using a Markov model of the natural history of LTBI.

Figure 3.

A decision tree that will be used in the economic analysis of the trial. INH, isoniazid.

One-way, multiway and probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSA) will be performed to evaluate the impact of alternative scenarios, assumptions and uncertainties on the results of the CEA. Results of the PSA will be presented as scatter plots on the cost-effectiveness plane and as a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, and the Canadian cost-effectiveness threshold of $C50 000/QALY will be indicated in our final results.

Consent

After a clinic staff member introduces the trial, a nurse will provide the potential participant with further details. If the participant would like to enrol, the nurse will discuss the information in the consent form and inform them that participation is voluntary. If the participant is not fluent in English, translation services are available in over 150 languages. Participants will be given the opportunity to ask questions before providing written consent. Once signed, each participant will be provided with a copy of the information sheet and consent form.

Confidentiality

To maintain participant confidentiality, all personally identifiable information will be removed from questionnaires and study documents where possible. Participants will be identified on these forms by a unique study identification number (ID). Study documents containing personal information, for example, informed consent forms, etc will be kept separate from other study data. Completed questionnaires and study documents will be stored in locked filing cabinets with limited access. The risk of breach of confidentiality resulting from the text-messaging intervention will be minimised since the content of the text messages will not include language related to TB. Data stored on computer databases will be password-protected and access to files will be limited to research staff who require direct access.

Dissemination

Regardless of the significance, direction or magnitude of effect, we will submit our findings for publication in peer-reviewed journals. We will also report study findings through conference abstracts, relevant websites, at workshops and to the participating clinic staff and patients. Once all of the data have been collected and cleaned, we will aim to submit the trial results for publication within 3 months.

Conclusion

Poor medication adherence and incomplete LTBI treatment are critical limitations to TB control efforts. Practical, cost-effective interventions that improve treatment completion are needed. This RCT provides an opportunity to rigorously evaluate whether the use of simple weekly text messages (the WelTel intervention) can improve treatment completion among patients initiating treatment for LTBI in BC. The results of this study are important to guide future adoption and implementation of WelTel and similar mHealth interventions in populations with LTBI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Daljeet Mahal for reviewing the manuscript and the patients and staff at the Vancouver and New Westminster TB Control clinics for participating in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: RTL, JH, DT and FM conceived the study. RTL, JH, DT, FM and LH secured funding. RTL, JH, JJ, LT, FM, MS, DT, KS and MLvdK contributed to the study design. KS designed the data collection instruments. MLvdK and JM drafted the manuscript apart from the cost-effectiveness section, which AP drafted. MS and FM provided cost-effectiveness expertise. All authors contributed critical intellectual input and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The protocol reported in this publication was supported by the British Columbia Lung Association (ref. no F10-06110) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Partnerships for Health System Improvement (ref. no. 267385).

Competing interests: MLvdK is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Doctoral Award—Doctoral Foreign Study Award (October 2012), offered in partnership with the CIHR Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research and the CIHR HIV/AIDS Research Initiative. RTL is the founder of WelTel, a non-profit non-governmental mHealth organisation with the goal of scaling up evidence-based mHealth solutions.

Ethics approval: The study protocol, information and consent form, and questionnaires were approved by the University of British Columbia Clinical Research Ethics Board (H12-02216). Ethical approval will be renewed on an annual basis.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahle UR, Eldholm V, Winje BA, et al. Impact of immigration on the molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a low-incidence country. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:930–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowie RL, Sharpe JW. Tuberculosis among immigrants: interval from arrival in Canada to diagnosis. A 5-year study in southern Alberta. CMAJ 1998;158:599–602 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comstock GW. How much isoniazid is needed for prevention of tuberculosis among immunocompetent adults? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1999;3:847–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills E, Nachega J, Bangsberg D, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med 2006;3:e438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horsburgh CR, Jr, Goldberg S, Bethel J, et al. Latent TB infection treatment acceptance and completion in the United States and Canada. Chest 2010;137:401–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jasmer RM, Nahid P, Hopewell PC. Clinical practice. Latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1860–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch-Moverman Y, Daftary A, Franks J, et al. Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: systematic review of studies in the US and Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:1235–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lobato MN, Reves RR, Jasmer RM, et al. Adverse events and treatment completion for latent tuberculosis in jail inmates and homeless persons. Chest 2005;127:1296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nyamathi AM, Christiani A, Nahid P, et al. A randomized controlled trial of two treatment programs for homeless adults with latent tuberculosis infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006;10:775–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376: 1838–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Kop ML, Memetovic J, Smillie K, et al. Use of the WelTel mobile health intervention at a tuberculosis clinic in British Columbia: a pilot study. JMTM 2013;2:7–14 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridges.org. On cue compliance service pilot: testing the use of SMS reminders in the treatment of tuberculosis in Cape Town, South Africa. Cape Town, 2005

- 14.Iribarren S, Chirico C, Echevarrria M, et al. TextTB: a parallel design randomized controlled pilot study to evaluate acceptance and feasibility of a patient-driven mobile phone based intervention. JMTM 2012;1(4S):23–4 [Google Scholar]

- 15.BC Centre for Disease Control. TB in British Columbia: annual surveillance report 2011. Vancouver: Provincial Health Services Authority, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nglazi MD, Bekker LG, Wood R, et al. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to anti-tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halsey NA, Coberly JS, Desormeaux J, et al. Randomised trial of isoniazid versus rifampicin and pyrazinamide for prevention of tuberculosis in HIV-1 infection. Lancet 1998;351:786–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menzies D, Long R, Trajman A, et al. Adverse events with 4 months of rifampin therapy or 9 months of isoniazid therapy for latent tuberculosis infection: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:689–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary test of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian tuberculosis standards. 7th edn Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quorus Consulting Group. 2012 cell phone consumer attitudes study. Ottawa: Quorus Consulting Group Ltd, 2012 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.