Abstract

Mouse models for cancer are revealing novel cancer-promoting roles for autophagy. Autophagy promotes tumor growth by suppressing the p53 response, maintaining mitochondrial function, sustaining metabolic homeostasis and survival in stress, and preventing diversion of tumor progression to benign oncocytomas.

Introduction

Macroautophagy (autophagy hereafter) is a highly conserved pathway that degrades and recycles proteins and organelles to generate nucleotides, amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, and ATP to support metabolism and survival in starvation (Rabinowitz and White, 2010). Autophagy also eliminates protein aggregates and damaged organelles to maintain protein and organelle quality (Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011). Autophagy is thought to play a dual role in cancer, where it can prevent tumor initiation by suppressing chronic tissue damage, inflammation, and genome instability via its quality control function or can sustain tumor metabolism, growth, and survival via nutrient recycling (White, 2012). Determining the contextual role of autophagy in cancer is therefore important, and the use of genetic engineered mouse models (GEMMs) in this regard is becoming increasingly useful.

Autophagy Prevents Tissue Damage and Maintains Genome Stability

Autophagy mitigates oxidative stress by removing damaged mitochondria, a key source of reactive oxygen species (ROS). A deficiency in essential autophagy genes (Atgs) causes the accumulation of defective mitochondria, excess ROS, DNA damage, and genome instability (Mathew et al., 2007, 2009). Autophagy may suppress DNA damage induced by ROS and may have other roles in enabling DNA repair. Nucleotide depletion promotes genome damage (Bester et al., 2011), and autophagy may supply nucleotides for DNA replication and repair through its recycling function (Rabinowitz and White, 2010). Autophagy has also been implicated in the timely degradation of Sae2/CtIP in response to histone deacetylase inhibition, a protein involved in homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA repair (Robert et al., 2011).

Defects in autophagy lead to aberrant accumulation of damaged organelles and proteins, particularly the autophagy receptor and substrate p62 and the antioxidant transcription factor NRF2. Their deregulation can induce chronic tissue damage and inflammation (Komatsu et al., 2010; Mathew et al., 2009). These activities may explain why mice with allelic loss of the essential autophagy gene Atg6/Beclin1 are prone to liver tumors and why those with mosaic deletion of Atg5 or liver-specific deletion of Atg7 develop benign liver hepatomas (Takamura et al., 2011). Loss of p62 reduces liver damage and hepatoma formation resulting from autophagy deficiency, indicating that aberrant accumulation of p62 is largely the cause (Komatsu et al., 2010; Takamura et al., 2011). In these contexts, autophagy likely plays a tumor-suppressive role, but whether this occurs in human cancer remains to be determined. As autophagy defects are genotoxic, it is possible that this impacts the growth of tumors with compromised DNA repair.

Autophagy Promotes Mammary Tumorigenesis

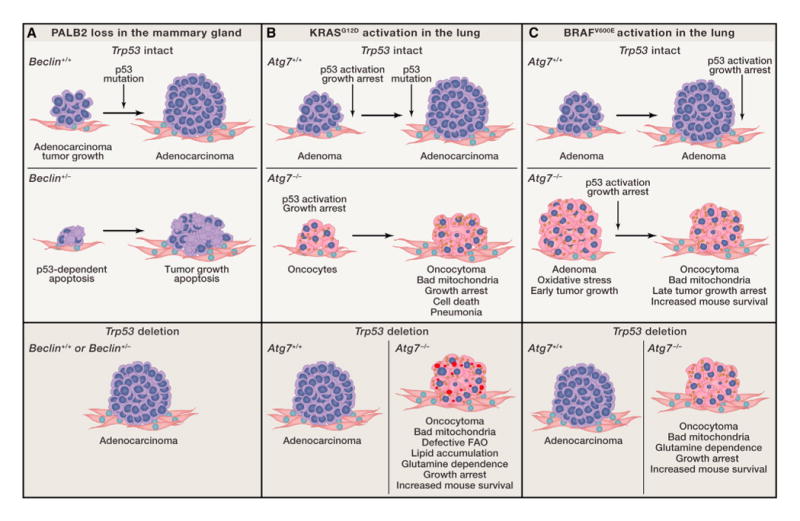

Germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2 predispose to hereditary breast cancer. These proteins function together to maintain genome stability by promoting faithful repair of double-strand breaks via HR (Moynahan and Jasin, 2010), and the genome instability from their loss likely drives tumorigenesis. BRCA1 and PALB2 also promote the NRF2-mediated antioxidant defenses (Gorrini et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2012), suggesting that oxidative stress elicited by the loss of BRCA1 or PALB2 may limit proliferation, thereby preventing tumorigenesis. The TP53 gene encoding p53 is the most commonly mutated gene in human cancers and is a DNA damage response regulator, and overcoming p53-induced cell-cycle arrest, senescence, and cell death is critical for tumorigenesis. Progression of HR-deficient and most, if not all, other tumors is facilitated by inactivation of p53 or its regulatory pathways. Similar to Brca1 and Brca2, mammary epithelial cell-specific knockout of Palb2 causes mammary tumorigenesis with long latency, and tumors contain mutations in Trp53 (Huo et al., 2013). Combined ablation of Palb2 and Trp53 accelerates tumorigenesis, establishing that p53 is a barrier to Palb2-associated mammary tumor growth (Figure 1A). Partial autophagy impairment due to allelic loss of Beclin1 increases apoptosis and significantly delays mammary tumor development following PALB2 loss but only when p53 is present (Huo et al., 2013). Thus, autophagy promotes mammary tumor growth by suppressing p53 activation induced by DNA damage (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Role of Autophagy in Tumor Progression and Fate.

(A) Autophagy promotes mammary tumorigenesis induced by PALB2 loss.

(B) Autophagy promotes the growth of KRASG12D-driven NSCLC. Lipid droplets are indicated in red, oncocytes are indicated in pink, and defective mitochondria are indicated in yellow.

(C) Autophagy promotes BRAFV600E-induced lung tumor growth.

These findings suggest that autophagy inhibition may be a valid approach for the therapy of HR-deficient breast cancers, but they also raise additional questions. Given the shared functions of BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2, do autophagy defects also suppress mammary tumor development driven by loss of BRCA1 and BRCA2? Is the defective tumorigenesis caused by allelic loss of Beclin1 due to autophagy impairment or an autophagy-independent function of Beclin1? The consequences of deleting other essential autophagy genes on tumorigenesis in this context should be tested. Whether complete rather than partial autophagy defect reveals p53-independent autophagy dependence of PALB2-deficient tumors also remains to be determined. As inhibiting autophagy may be useful in the setting of HR-deficiency with p53 intact, will it also be efficacious in combination with inhibitors of HR in repair-proficient tumors? Finally, will cancers with deficiencies in other DNA repair mechanisms also be sensitized to autophagy inhibition?

KRAS-Driven Cancers Are Addicted to Autophagy

Basal autophagy levels are low in normal, fed cells. RAS-driven cancer cells have high levels of autophagy to maintain mitochondrial function for their metabolic needs (Guo et al., 2011). Lack of Atg5 or Atg7 in KRAS-transformed cells causes accumulation of morphologically abnormal mitochondria. In contrast to KRAS-transformed cells that are autophagy proficient, those that are autophagy deficient fail to maintain levels of tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) metabolites and mitochondrial respiration upon nutrient starvation, which creates an energy crisis incompatible with survival (Guo et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011). Autophagy deficiency also impairs the tumorigenicity of KRAS-transformed cells and human cancer cell lines with activating mutations in KRAS, thereby playing a critical role in sustaining the mitochondrial metabolism and stress tolerance of these cancers.

Autophagy Dictates Lung Tumor Fate

In GEMMs for lung cancer, sporadic activation of an oncogenic allele of Kras (KrasG12D) results in tumor initiation and gradual progression to adenomas and adenocarcinomas upon acquisition of Trp53 mutations. Deletion of Atg7 dramatically alters the progression of these tumors, producing the accumulation of defective mitochondria, accelerated induction of p53, and proliferative arrest. Without ATG7, tumors develop into oncocytomas instead of adenomas and carcinomas, proliferation is suppressed, and tumor burden is reduced (Figure 1B) (Guo et al., 2013).

Oncocytomas are a rare, predominantly benign tumor type signified by the accumulation of respiration-defective mitochondria attributed to mitochondrial genome mutations and compensatory mitochondrial biogenesis (Gasparre et al., 2011). Generation of oncocytomas upon loss of autophagy suggests autophagy defects, and the failure to remove defective mitochondria can also produce oncocytomas. Importantly, autophagy impairment can divert progression of adenomas and carcinomas to a more benign tumor type (Guo et al., 2013). Lung cancers thus require autophagy to remove damaged mitochondria in order to maintain their function. As such, autophagy defects may be an underlying basis for the genesis of human oncocytomas, and autophagy inhibition in lung cancer therapy may suppress tumor growth and produce more benign disease.

Autophagy Addiction of BRAF-Driven Tumors

Atg7 deletion in GEMMs for BRAFV600E-driven lung cancer initially stimulates tumor growth, but this is transient and is attributed to increased mitochondrial oxidative stress. As Nrf2 deficiency in the BrafV600E lung tumors also promotes early tumor growth, whereas combined loss of both Atg7 and Nrf2 shows no additional effect, the two genes may act by the same mechanism (Figure 1C) (Strohecker et al., 2013). Nrf2 loss decreases the transcription of ROS detoxification genes, and Atg7 loss prevents elimination of ROS-producing mitochondria; thus, increased ROS may transiently stimulate the proliferation of newly forming tumors. Over time, Atg7 deficiency causes accumulation of defective mitochondria and accelerates p53 induction and growth arrest. Ultimately, Atg7 deficiency, like Nrf2 deficiency, impairs tumorigenesis. Thus, BRAFV600E-driven lung tumors are also addicted to autophagy (Strohecker et al., 2013).

One interesting distinction between the roles of autophagy in KRAS-driven compared to BRAF-driven lung tumors relates to the survival of the mice. Autophagy deficiency reduces tumor burden in both settings when p53 was present, but overall mouse survival is only increased with activated BRAF (Strohecker et al., 2013). Autophagy-deficient Kras lung tumors cause mice to die of pneumonia instead of cancer (Figure 1B and C) (Guo et al., 2013), which may be due to autophagy defects promoting inflammation (Deretic, 2011).

Autophagy Suppresses the Ability of p53 to Limit Tumor Growth

In both KRAS and BRAF lung tumors, removal of p53 greatly accelerates progression to adenocarcinomas; however, the loss of Atg7 still retains some antiproliferative effect (Figure 1B and C). This is in contrast to the Palb2-deficient tumors in which allelic loss of Beclin1 has no effect in the absence of p53. Whether autophagy works through p53-dependent or -independent mechanisms depends therefore upon the mutagenic drivers of tumor growth. For example, loss of PALB2 and HR may directly activate p53 and the DNA damage response by causing DSBs, whereas loss of KRAS and BRAF does not impinge upon a similar response.

Autophagy Relieves Dependence on Glutamine

Atg7-deficient tumor cells derived from KRASG12D-driven or BRAFV600E-driven lung cancers display less mitochondrial respiration and are sensitized to starvation-induced cell death (Guo et al., 2013; Strohecker et al., 2013). Thus, maintaining functional mitochondria by upregulating autophagy might be one survival strategy for autophagy-addicted cancers. This sensitivity to starvation conferred by loss of autophagy is rescued by glutamine supplementation (Guo et al., 2013; Strohecker et al., 2013). Autophagy may provide amino acids via protein degradation to replenish TCA cycle intermediates, enable glutamine usage for NADPH production and redox balance, and suppress senescence (White, 2013). Although RAS-driven cancers can acquire glutamine by consuming and digesting extracellular albumin through macropinocytosis, autophagy may provide an alternative glutamine supply critical in the absence of accessible extracellular protein and amino acids (White, 2013).

Autophagy Maintains Lipid Homeostasis in KRAS-Driven Tumors with p53 Loss

A unique feature of autophagy-deficient p53 null KRAS lung cancers is the striking accumulation of lipids (Guo et al., 2013). In the absence of p53, autophagy is required to maintain mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and without autophagy, tumor cells contain mitochondria that fail to respire when provided a lipid substrate (Guo et al., 2013). p53 deficiency alters metabolism to promote lipid storage (Cheung and Vousden, 2010; Zhu and Prives, 2009). If lipid catabolism by FAO significantly contributes to the metabolism of these p53-deficient tumors, preservation of mitochondrial function through mitophagy may be essential for lipid degradation, utilization, and homeostasis. Furthermore, lipid accumulation due to autophagy ablation does not occur in BRAFV600E-induced lung tumors (Strohecker et al., 2013), indicating a fundamental difference of lipid metabolism and perhaps also utilization of mitochondria among lung tumors driven by different oncogenes.

Why Is Autophagy Addiction Partly p53 Dependent?

Autophagy suppresses the p53 response likely by limiting DNA damage, oxidative stress, or other aspects of oncogene activation, thereby alleviating an important cell-cycle checkpoint that impedes tumorigenesis. How then may autophagy limit p53 function? p53 is a key checkpoint regulator, and its abundance and activity increase following DNA damage and a myriad of other stressors. Autophagy is also a protective response to stress and prevents genome damage. Loss of PALB2 and the resulting ROS and DNA damage can trigger p53 activation that may be further enhanced by loss of the protective function of autophagy. The same may also hold true for oncogenic KRAS and BRAF because they can cause DNA replication stress that may be further augmented by autophagy deficiency. Alternatively, autophagy may degrade p53 and limit its accumulation (Korolchuk et al., 2009). This, however, seems unlikely because autophagy deficiency causes genome instability even in the absence of p53, suggesting that it is suppressing the occurrence of DNA damage rather than the response to it (Mathew et al., 2007).

Once induced, p53 can activate the transcription of genes in the autophagy pathway and promote autophagy (Crighton et al., 2006; Kenzelmann Broz et al., 2013). Autophagy induction by p53 may be a negative feedback mechanism to turn down p53 function. A failure to limit p53 in autophagy-deficient cells may be cytotoxic.

Another explanation for this dependence may relate to their roles in metabolism. p53 loss promotes glycolysis and suppresses respiration (Cheung and Vousden, 2010), which reduces ROS that may require mitigation by autophagy to limit DNA damage, growth arrest, senescence, and apoptosis. Thus, the absence of p53 can render autophagy less important. Autophagy also provides metabolic substrates to support cellular metabolism (Rabinowitz and White, 2010). Autophagy may supply nucleotides for efficient DNA repair or may otherwise promote the function of the DNA repair machinery, lessening p53 activation. Determining the mechanism by which autophagy modulates the DNA damage response and DNA repair pathways and vice versa is important.

Exploiting Autophagy Inhibition in Cancer Therapy

These recent findings that autophagy promotes tumorigenesis support the concept of autophagy inhibition as a potential approach to cancer prevention and treatment. Given that autophagy supplies metabolic substrates essential for cancer cell survival, identification of the exact substrates that are provided and the processes they support may also reveal novel targets for cancer therapy.

As with Palb2 mutation, blocking autophagy may prevent the development or slow the progression of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast cancers and perhaps other cancers whose etiology involves defective DNA repair and ROS overproduction. Moreover, blocking mitophagy or targeting mitochondrial metabolism might be a potential approach to compromise the survival of KRAS- or BRAF-driven lung cancers. Additionally, targeting FAO may be applied to KRAS-driven lung cancers with p53 inactivation. Autophagy inhibition may also be valuable in combination with other anticancer therapeutic approaches (White, 2012).

For optimal use of autophagy inhibition in cancer therapy, additional issues need to be addressed. For example, would autophagy inhibition in established tumors lead to oncocytomas and suppressed growth? How long does it take for autophagy inhibition to suppress the growth of established tumors? Is autophagy inhibition selectively detrimental to tumors compared to normal tissue? Are the detrimental consequences of autophagy ablation reversible in tumor versus normal tissue, and is this applicable to human tumors? More importantly, what happens if autophagy is restored in autophagy-deficient tumors? These questions are readily addressable and will guide us moving forward.

Acknowledgments

The White laboratory acknowledges support from NIH grants R37CA53370, RC1CA147961, R01CA163591, and R01CA130893, the Department of Defense (W81XWH-09-01-0394), the Val Skinner Foundation, the New Jersey Commission for Cancer Research, and the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. The Xia laboratory is supported by the NIH (RC1CA147961), the American Cancer Society (RSG TBG-119822), and the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. The authors apologize for the limited number of citations due to space limitation. Eileen White is a member of the scientific advisory board of Forma Therapeutics.

References

- Bester AC, Roniger M, Oren YS, Im MM, Sarni D, Chaoat M, Bensimon A, Zamir G, Shewach DS, Kerem B. Cell. 2011;145:435–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung EC, Vousden KH. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, Gasco M, Garrone O, Crook T, Ryan KM. Cell. 2006;126:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V. Immunol Rev. 2011;240:92–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparre G, Romeo G, Rugolo M, Porcelli AM. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorrini C, Baniasadi PS, Harris IS, Silvester J, Inoue S, Snow B, Joshi PA, Wakeham A, Molyneux SD, Martin B, et al. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1529–1544. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Kamphorst JJ, Chen G, Lemons JM, Karantza V, et al. Genes Dev. 2011;25:460–470. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JY, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Mathew R, Aisner SC, Kamphorst JJ, Strohecker AM, Chen G, Price S, Lu W, Teng X, et al. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1447–1461. doi: 10.1101/gad.219642.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo Y, Cai H, Teplova I, Bowman-Colin C, Chen G, Price S, Barnard N, Ganesan S, Karantza V, White E, et al. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:894–907. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenzelmann Broz D, Spano Mello S, Bieging KT, Jiang D, Dusek RL, Brady CA, Sidow A, Attardi LD. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1016–1031. doi: 10.1101/gad.212282.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, Taguchi K, Kobayashi A, Ichimura Y, Sou YS, Ueno I, Sakamoto A, Tong KI, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:213–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolchuk VI, Mansilla A, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC. Mol Cell. 2009;33:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Cai H, Wu T, Sobhian B, Huo Y, Alcivar A, Mehta M, Cheung KL, Ganesan S, Kong AN, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1506–1517. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06271-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Kongara S, Beaudoin B, Karp CM, Bray K, Degenhardt K, Chen G, Jin S, White E. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1367–1381. doi: 10.1101/gad.1545107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karp CM, Beaudoin B, Vuong N, Chen G, Chen HY, Bray K, Reddy A, Bhanot G, Gelinas C, et al. Cell. 2009;137:1062–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Cell. 2011;147:728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynahan ME, Jasin M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:196–207. doi: 10.1038/nrm2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JD, White E. Science. 2010;330:1344–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1193497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert T, Vanoli F, Chiolo I, Shubassi G, Bernstein KA, Rothstein R, Botrugno OA, Parazzoli D, Oldani A, Minucci S, Foiani M. Nature. 2011;471:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nature09803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohecker AM, Guo JY, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Price SM, Chen GJ, Mathew R, McMahon M, White E. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1272–1285. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, Sakamoto A, Kishi C, Waguri S, Eishi Y, Hino O, Tanaka K, Mizushima N. Genes Dev. 2011;25:795–800. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2065–2071. doi: 10.1101/gad.228122.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Wang X, Contino G, Liesa M, Sahin E, Ying H, Bause A, Li Y, Stommel JM, Dell'antonio G, et al. Genes Dev. 2011;25:717–729. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Prives C. Mol Cell. 2009;36:351–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]