Abstract

Autophagy is a process by which components of the cell are degraded to maintain essential activity and viability in response to nutrient limitation. Extensive genetic studies have shown that the yeast ATG1 kinase has an essential role in autophagy induction. Furthermore, autophagy is promoted by AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK), which is a key energy sensor and regulates cellular metabolism to maintain energy homeostasis. Conversely, autophagy is inhibited by the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a central cell-growth regulator that integrates growth factor and nutrient signals. Here we demonstrate a molecular mechanism for regulation of the mammalian autophagy-initiating kinase Ulk1, a homologue of yeast ATG1. Under glucose starvation, AMPK promotes autophagy by directly activating Ulk1 through phosphorylation of Ser 317 and Ser 777. Under nutrient sufficiency, high mTOR activity prevents Ulk1 activation by phosphorylating Ulk1 Ser 757 and disrupting the interaction between Ulk1 and AMPK. This coordinated phosphorylation is important for Ulk1 in autophagy induction. Our study has revealed a signalling mechanism for Ulk1 regulation and autophagy induction in response to nutrient signalling.

Under nutrient starvation, cells initiate a lysosomal-dependent self-digestive process known as autophagy, whereby cytoplasmic contents, such as damaged proteins and organelles, are hydrolyzed to generate nutrients and energy to maintain essential cellular activities1–4. Autophagy is a tightly regulated process and defects in autophagy have been closely associated with many human diseases, including cancer, myopathy and neurodegeneration5–7. Autophagy has also been implicated in clearance of pathogens and antigen presentation8–10. Genetic studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have defined the autophagy machinery11–13. Among the components of this machinery, the ATG1 kinase, which forms a complex with ATG13 and ATG17, is a key regulator in autophagy initiation14–18. Mammals have ATG1 homologues, Ulk1 and Ulk2 (refs 19, 20), and the mammalian counterparts of ATG13 and ATG17 are reported as mATG13 and FIP200, respectively3,21–22. However, the mechanism underlying Ulk1 regulation is largely unknown, although a modest Ulk1 activation induced by nutrient starvation has been reported18,21,23.

The inhibitory function of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) in autophagy is well established24–26. mTORC1 activity reflects cellular nutritional status27. Therefore, understanding how mTORC1 regulates autophagy is of great importance because it may link nutrient signals to regulation of autophagy. The connection between ATG1 kinase and TORC1 has been elucidated in yeast28. ATG13 is an essential component of the ATG1 complex29, and phosphorylation of ATG13 by TORC1 results in the disruption of this complex16,30. Accumulating reports have suggested that there is also a relationship between Ulk1 and mTORC1 in mammalian cells21,23,31. However, the molecular basis of mTORC1 in autophagy regulation remains to be addressed. Another potential candidate in autophagy regulation is AMPK because it senses cellular energy status to maintain energy homeostasis32. There is evidence to support a role for AMPK in autophagy induction in response to various cellular stresses, including glucose starvation33–37. However, the molecular mechanism underlying how AMPK regulates autophagy is largely unknown though it is generally assumed that AMPK stimulates autophagy by inhibiting mTORC1 at the level of TSC2 (ref. 38) and Raptor39. In this study, we provide molecular insights into how AMPK and mTORC1 regulate autophagy through coordinated phosphorylation of Ulk1.

RESULTS

Glucose starvation activates Ulk1 protein kinase through AMPK-dependent phosphorylation

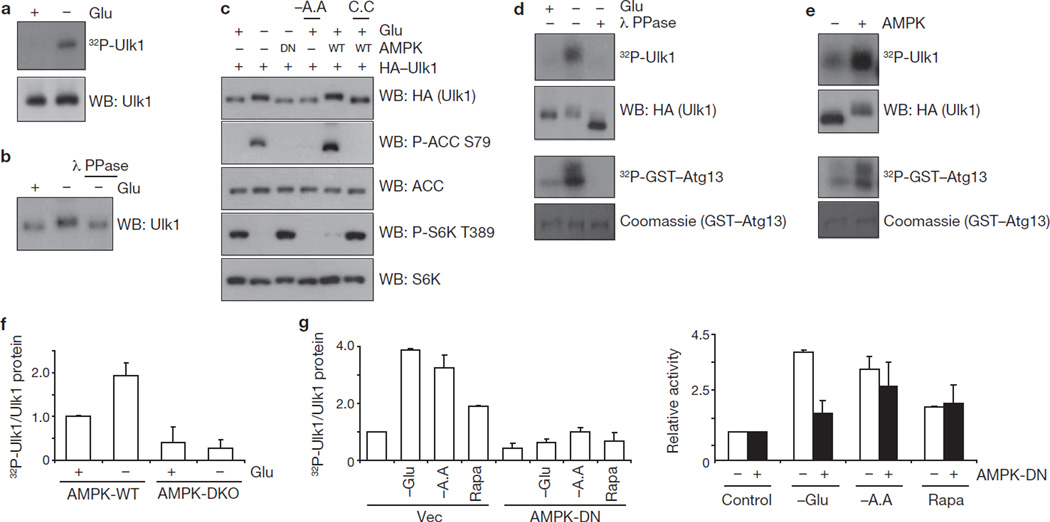

We examined the effect of glucose starvation on Ulk1 and observed a significant Ulk1 activation on glucose starvation, as indicated by increased Ulk1 autophosphorylation (Fig. 1a). Also, glucose deprivation induced a Ulk1 mobility shift that was reversed by phosphatase treatment, suggesting that glucose starvation induced Ulk1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1b). This shift was more evident on a phos-tag gel40 and was suppressed by inhibition of AMPK with compound C (6-[4-(2-Piperidin-1-yl-ethoxy)-phenyl)]-3-pyridin-4-yl-pyyrazolo[1,5-a] pyrimidine; ref. 41; Supplementary Information, Fig. S1a). Consistently, the Ulk1 mobility shift induced by glucose starvation was suppressed by co-expression of the AMPKα kinase-dead (DN) mutant, which dominantly interfered with AMPK signalling as indicated by the decreased phosphorylation of ACC (acetyl-CoA carboxylase), an AMPK substrate, and increased phosphorylation of S6K (p70S6 kinase), an mTORC1 substrate, in response to glucose starvation (Fig. 1c). Moreover, overexpression of wild-type AMPKα was sufficient to induce a Ulk1 mobility shift even under glucose-rich conditions, which was blocked by compound C (Fig. 1c). It is worth noting that amino-acid starvation, which inhibited S6K phosphorylation, did not induce obvious Ulk1 mobility shift or ACC phosphorylation. Together, these data indicate that AMPK might be responsible for Ulk1 phosphorylation induced by glucose starvation.

Figure 1.

Glucose starvation activates Ulk1 protein kinase through AMPK-dependent phosphorylation. (a) HEK293 cells were starved of glucose (4 h) as indicated, endogenous Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated and an autophosphorylation assay was performed. Proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and visualized with autoradiography (top) or western blotting (WB; bottom). (b) Cells were incubated in glucose-free medium (4 h) as indicated and lysed. Lysates were incubated with lambda phosphatase (λ PPase) as indicated. Endogenous Ulk1 mobility was examined by western blotting. (c) HA–Ulk1 was transfected into HEK293 cells together with wild-type (WT) AMPKα1 or a kinase-dead (DN) mutant. Cells were starved of glucose (4 h; Glu) or amino acids (−A.A) and treated with compound C (20 µM, C.C) as indicated. Ulk1 mobility as well as phosphorylation levels of ACC and S6K were determined by western blotting. (d) HA–Ulk1 proteins were immunopurified from transfected HEK293 cells, which had undergone glucose starvation (4 h) as indicated. The HA–Ulk1 proteins were treated with λ PPase, and in vitro kinase assays were performed in the presence of GST–ATG13. Proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE; phosphorylated proteins were visualized with autoradiography, HA–Ulk1 by western blotting and GST–Atg13 by Coomassie staining. (e) HA–Ulk1 was immunopurified from transfected HEK293 cells under glucose-rich media and treated with AMPK in the presence of cold ATP for 15 min, followed by kinase assays as described in d. (f) AMPK wild-type (WT) and α1/α2 double knockout (DKO) MEFs were incubated with or without glucose (4 h). Endogenous Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated and autophosphorylation was measured (mean ± s.d., n = 3). Autophosphorylation activity was normalized to Ulk1 protein level; relative activity is calculated by normalization to Ulk1 activity from AMPK wild-type MEFs in glucose-rich conditions. (g) HA–Ulk1 was transfected into HEK293 cells together with vector (Vec) or an AMPKα1 kinase-dead mutant (DN). The cells were starved of glucose (−Glu) or amino acids (−A.A), or treated with 50 nM rapamycin (Rapa) for 3 h before lysis. Left: autophosphorylation activity was assessed and normalized as in f (mean ± s.d., n = 3). Right: fold induction in Ulk1 autophosphorylation, compared with Ulk1 autophosphorylation from cells under nutrient-rich conditions. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

To determine the effect of the phosphorylation induced by glucose starvation on Ulk1 activity, Ulk1 immune-complex prepared from the glucose-starved cells was treated with lambda phosphatase in vitro and then measured for kinase activity. In this experimental setting we confirmed that the phosphatase was efficiently removed because no dephosphorylation of the pre-labelled 32P-GST–TSC2 occurred (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1b). We observed that the phosphatase treatment largely diminished glucose starvation-induced Ulk1 kinase activity as indicated by decreased autophosphorylation and trans-phosphorylation of GST–ATG13 (Fig. 1d). Similarly, lambda phosphatase treatment inactivated the endogenous Ulk1 and increased Ulk1 mobility (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1b). These data suggest that the phosphorylation induced by glucose starvation may contribute to Ulk1 activation.

As glucose starvation activated Ulk1 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and this phosphorylation was suppressed by dominant-negative AMPK or compound C, we investigated if Ulk1 could be directly activated by AMPK. HA–Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated from the transfected cells cultured on glucose-rich medium and then incubated with AMPK in the presence of cold ATP in vitro, followed by a Ulk1 kinase assay. AMPK pre-treatment significantly increased Ulk1 kinase activity and decreased Ulk1 mobility (Fig. 1e). As controls, AMPK could not activate Ulk1 in the absence of ATP or in the presence of AMPK inhibitor (compound C; Supplementary Information, Fig. S1c), indicating that AMPK directly phosphorylated and activated Ulk1. The Ulk1 autophosphorylation visualized by 32P-autoradiogram was not a result of AMPK contamination because an Ulk1 kinase-inactive mutant (K46R) did not show any Ulk1 autophosphorylation in the same experimental setting even though Ulk1K46R was phosphorylated by AMPK as evidenced by a decreased mobility (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1d). Also, overexpression of AMPK could activate the co-transfected HA–Ulk1 even in glucose-rich condition, which is comparable to Ulk1 activation by glucose starvation (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1e).

During autophagy, carboxy-terminal lipid modification of LC3 is a well-characterized phenomenon required for autophagosome formation, which can be readily detected by an increased electrophoretic mobility (LC3-II)42. Glucose starvation increased LC3-II similarly to rapamycin treatment and this effect was blocked by compound C (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1f), supporting a role for AMPK in induction of autophagy through glucose starvation. To further determine the function of AMPK in Ulk1 activation under physiological conditions, we measured Ulk1 activity in AMPKα1/α2 double knockout (DKO) cells. We observed that endogenous Ulk1 had a lower basal activity, and importantly could not be activated by glucose starvation (Fig. 1f). Together, these data demonstrate that Ulk1 activation induced by glucose starvation is mediated by AMPK, which directly activates Ulk1 by phosphorylation.

The effect of amino-acid starvation, which also induces autophagy, on Ulk1 activity was examined. Consistent with the recent reports21,23, amino-acid starvation increased Ulk1 autophosphorylation activity (Fig. 1g). Interestingly, amino-acid starvation could still stimulate Ulk1 activation in the cells expressing AMPK-DN mutant although overall Ulk1 activity was lower in these cells. Similarly, rapamycin could activate Ulk1 in these cells. In contrast, Ulk1 activation induced by glucose starvation was largely blocked by AMPK-DN. These observations are consistent with the fact that AMPK is directly involved in cellular energy sensing but not amino-acid signalling. Consistently, amino-acid starvation could induce autophagic markers, LC3 lipidation (LC3-II, Supplementary Information, Fig. S1g) and green fluorescent protein (GFP)–LC3 puncta formation (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1h), in AMPK DKO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), whereas these cells were defective during autophagy induced by glucose starvation. These data suggest that Ulk1 kinase can be activated by both AMPK-dependent (glucose starvation) and -independent (amino-acid starvation) manners.

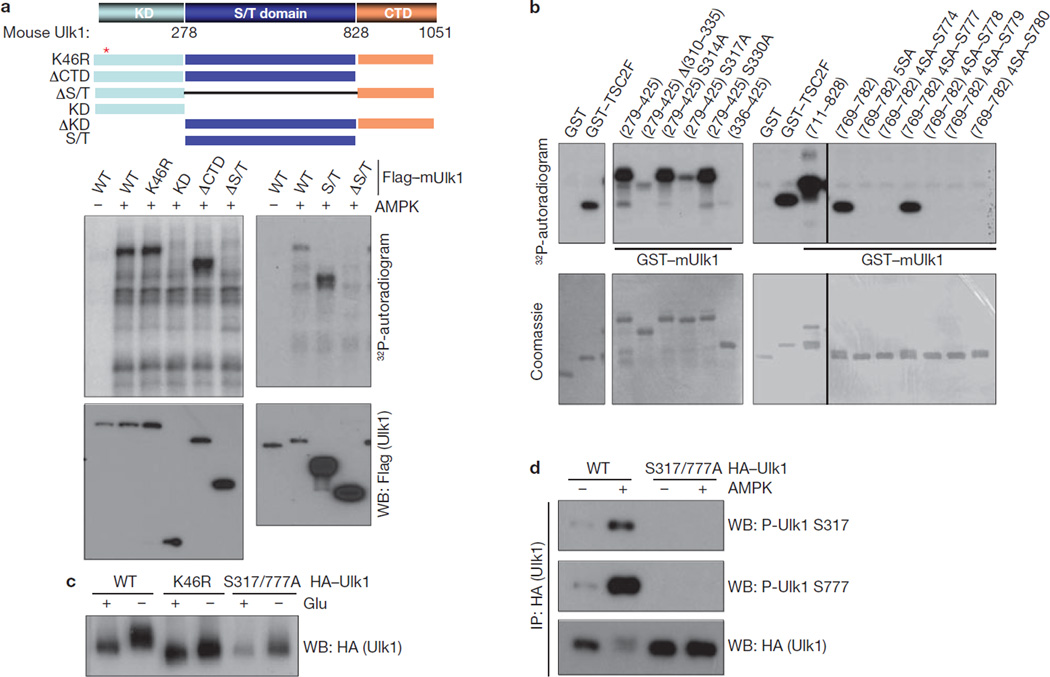

AMPK activates Ulk1 by phosphorylating Ser 317 and Ser 777

To understand the mechanism underlying Ulk1 activation by AMPK, we determined the AMPK phosphorylation sites in Ulk1. We initially tested the AMPK consensus sites in Ulk1. Surprisingly, mutation of the AMPK consensus sites (Ser 494, Ser 555, Ser 574, Ser 622, Thr 624, Ser 693 and Ser 811) in Ulk1 had no significant effect on Ulk1 phosphorylation by AMPK in vitro (data not shown). Next, we performed systematic Ulk1 deletion experiments and found that AMPK phosphorylated the serine/threonine-rich domain (S/T domain) of Ulk1 (Fig. 2a). Further deletion and mutation analyses identified Ser 317 and Ser 777 as the major AMPK phosphorylation sites (Fig. 2b). Mutation of both Ser 317 and Ser 777 significantly decreased, though not completely, the phosphorylation of full-length Ulk1 by AMPK in vitro (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2a), suggesting that there are additional AMPK phosphorylation sites in Ulk1. However, the Ulk1 mobility shift induced by glucose starvation, which was due to both phosphorylation by AMPK and autophosphorylation, was significantly compromised in the S317/777A mutant in the transfected cells (Fig. 2c), indicating that these two residues are major AMPK sites in response to glucose starvation in vivo. To confirm Ulk1 phosphorylation in vivo, antibodies were prepared and verified for specificity against recombinant Ulk1 fragments phosphorylated by AMPK in vitro at Ser 317 and Ser 777 (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2b). Western blot using these antibodies demonstrated that AMPK co-transfection increased Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

AMPK directly phosphorylates Ulk1 at Ser 317 and Ser 777. (a) AMPK phosphorylates the Ulk1 S/T domain in vitro. Top: schematic representation of Ulk1 domain structure and deletion constructs used to map phosphorylation sites. The mouse Ulk1 protein consists of an N-terminal kinase domain (KD; 1–278), serine/threonine-rich domain (S/T domain, 279–828), and C-terminal domain (CTD, 829–1051). Bottom: the indicated Flag–Ulk1 deletion mutants were immunopurified from transfected HEK293 cells and were used for in vitro AMPK assay as a substrate. Phosphorylation was examined by 32P-autoradiogram and protein level was determined by western blot. (b) Determination of AMPK phosphorylation sites in Ulk1. The indicated recombinant GST–Ulk1 mutants were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli, and used as substrates for in vitro phosphorylation by AMPK. Deletion analyses indicated that two Ulk1 fragments in the S/T domain, 279–425 and 769–782, were highly phosphorylated by AMPK in vitro. Mutation of Ser 317 abolished the majority of phosphorylation in the Ulk1 fragment 279–425. Within the fragment 769–782, mutations of five serine residues (Ser 774, Ser 777, Ser 778, Ser 779 and Ser 780) to alanine, denoted as (769–782) 5SA, completely abolished the phosphorylation by AMPK. Reconstitution of Ser 777 in this mutation background, (769–782) 4SA-S777, but not any of the other four residues, restored the phosphorylation by AMPK. GST and GST–TSC2F (TSC2 fragment 1300–1367 containing AMPK phosphorylation site at Ser 1345) were used as negative and positive controls for AMPK reaction, respectively. Phosphorylation was determined by 32P-autoradiograph and the protein levels were detected by Coomassie staining. (c) Ser 317/Ser 777 are required for glucose-starvation induced Ulk1 phosphorylation in vivo. HA–Ulk1 and mutants were transfected into HEK293 cells. Cells were starved for glucose for 4 h as indicated. HA–Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated and examined by western blot for mobility. (d) Phosphorylation of Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 are induced by AMPK. Wild-type HA–Ulk1 or S317/777A mutant were co-transfected with AMPK into HEK293 cells as indicated. HA–Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) and phosphorylation of Ser 317 and Ser 777 were determined by western blotting. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

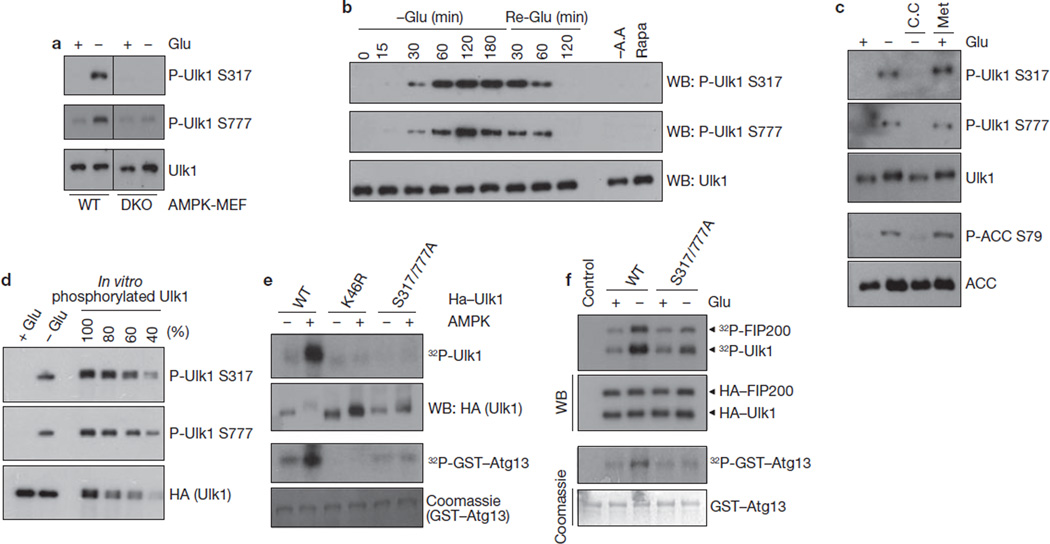

To determine Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation of endogenous Ulk1, total lysates of MEF cells were probed with phospho-Ser 317- and phospho-Ser 777-specific antibodies. We found that glucose starvation induced a robust Ulk1 phosphorylation at Ser 317 and Ser 777 (Fig. 3a). Notably, these phosphorylations were completely diminished in AMPK DKO cells. These data demonstrate an essential role for AMPK in phosphorylation of Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777. Phosphorylation of both Ser 317 and Ser 777 appeared at 30 min and peaked at 60–120 min on glucose deprivation and these phosphorylation events gradually decreased to basal level at 120 min after glucose re-addition (Fig. 3b). Notably, amino-acid starvation and rapamycin treatment were not sufficient to increase Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation because AMPK was not activated by these treatments. Moreover, phosphorylation of Ulk1 was inhibited by compound C and stimulated by Metformin (an AMPK activator43), similarly to the phosphorylation of AMPK substrate, ACC (Fig. 3c). This result shows that AMPK activation is necessary and sufficient for the phosphorylation of Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 on glucose starvation. To determine the levels of endogenous Ulk1 Ser 317/Ser 777 phosphorylation in response to glucose starvation, we compared relative phosphorylation of endogenous Ulk1 with the in vitro phosphorylated Ulk1, which was almost completely phosphorylated by AMPK based on mobility shift (Fig. 3d). Glucose starvation induced endogenous Ulk1 phosphorylation to a level approximately 50% of the in vitro phosphorylated Ulk1, indicating that a significant fraction of endogenous Ulk1 was indeed phosphorylated on glucose starvation. These data demonstrate that Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 are phosphorylated by AMPK under physiological conditions.

Figure 3.

AMPK-dependent Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation is required for Ulk1 activation in response to glucose starvation. (a) AMPK wild-type or DKO MEFs were starved of glucose (4 h) as indicated. Total cell lysates were probed for Ulk1 protein and phosphorylation. (b) Time course of Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation in response to glucose starvation/re-addition. MEFs were starved of glucose (−Glu) for the indicated times. After 3 h starvation, the culture was switched to glucose-containing (25 mM) medium and samples were harvested (Re-Glu). In parallel, cells were treated with amino-acid-free (−A.A) medium or 50 nM rapamycin (Rapa) for 3 h. (c) Phosphorylation of Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 correlates with AMPK activity. MEFs were starved of glucose (4 h) as indicated in the presence or absence of 20 µM compound C (C.C). In parallel, cells were treated with 2 mM Metformin (Met, 2 h) in glucose-rich medium. Phosphorylation of ACC S79 was tested as a positive control for AMPK activation. (d) Ulk1 is highly phosphorylated at Ser 317 and Ser 777 by glucose starvation in vivo. To determine the Ulk1 phosphorylation level in vivo, immunopurified HA–Ulk1 protein was phosphorylated by AMPK in vitro (100% represents full phosphorylation of Ulk1 by AMPK). In vitro phosphorylated HA–Ulk1 was diluted as indicated, and was immunoblotted along with the immunoprecipitated HA–Ulk1 from cells grown in either glucose-rich (+ Glu) or glucose-free (− Glu, 4 h) medium. The density of the bands was then quantified. By this measurement, approximately 50% of Ulk1 isolated from glucose-starved cells was phosphorylated on Ser 317 and Ser 777. (e) The indicated HA–Ulk1 proteins were immunopurified from transfected HEK293 cells grown in high-glucose medium, and then incubated with AMPK in the presence of cold ATP for 15 min in vitro. After the reaction, AMPK was removed by extensive washing, the resulting Ulk1 immuno-complexes were assayed for kinase activity in the presence of 32P-ATP. (f) HA–Ulk1 proteins (wild type or S317/777A mutant) were immunoprecipitated from the transfected HEK293 cells, which were incubated with or without glucose (4 h) before lysis. An in vitro kinase reaction was performed in the presence of GST–ATG13 and FIP200. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

Next, the functional significance of Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation in Ulk1 activation was examined. AMPK markedly activated wild-type Ulk1, but did not activate the kinase-inactive K46R mutant or the phosphorylation defective S317/777A mutant in vitro (Fig. 3e). Additional mutations of individual AMPK consensus sites in the S317/777A background did not markedly further decrease Ulk1 activity, suggesting that Ser 317 and Ser 777 are major sites for AMPK-induced Ulk1 activation (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2c). Consistent with the in vitro experimental data, HA–Ulk1S317/777A was minimally activated by glucose starvation in the transfected cells, whereas the wild-type HA–Ulk1 was more efficiently activated (Fig. 3f). Together, our data demonstrate the importance of Ser 317/Ser 777 phosphorylation in glucose-starvation-induced and AMPK-dependent Ulk1 activation.

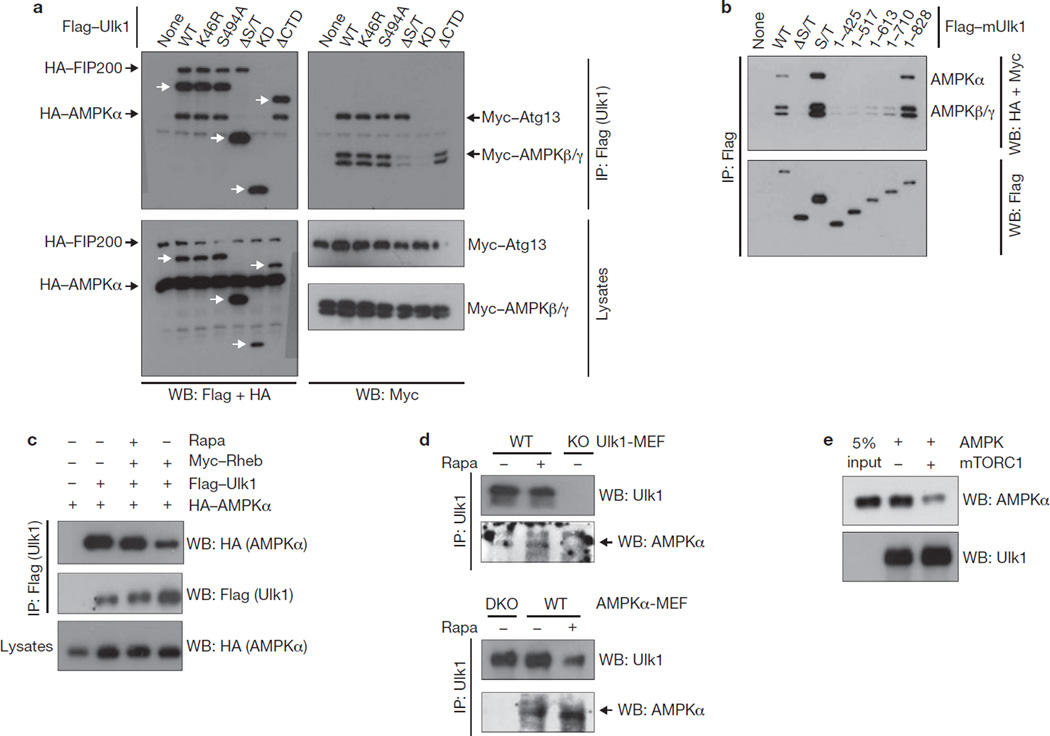

mTORC1 disrupts the Ulk1–AMPK interaction by phosphorylating Ulk1 Ser 757

In yeast, nutrient starvation promotes ATG1–ATG13–ATG17 complex formation, and concomitant ATG1-kinase activation16–17. However, a similar regulation may not apply to the mammalian Ulk1 because the Ulk1 complex formation is not regulated by nutrients22–23. Instead, we observed an interaction between Ulk1 and AMPK (Fig. 4a). Deletion analyses showed that the S/T domain, particularly the fragment (711–828) of Ulk1, was required to bind AMPK (α, β and γ; Fig. 4a, b). Notably, the AMPK-binding domain does not overlap with the ATG13- and FIP200-binding regions (C-terminal domain of Ulk1, CTD). The interactions of Ulk1–AMPK and Ulk1–ATG13–FIP200 were not affected by glucose starvation (data not shown). The yeast TORC1 was reported to disrupt the ATG1 complex16, but mTORC1 does not have a similar effect on the Ulk1–mAtg13–FIP200 complex22–23. Interestingly, we found that the interaction between Ulk1 and AMPK was disrupted by mTORC1. Overexpression of Rheb, an mTORC1 activator44–45, decreased Ulk1–AMPK co-immunoprecipitation and rapamycin suppressed the effect of Rheb (Fig. 4c). Consistently, rapamycin treatment increased the interaction of endogenous Ulk1 and AMPK (Fig. 4d). Considering the report that mTORC1 could phosphorylate Ulk1 although the phosphorylation sites were not identified21,23,31, we examined whether mTORC1 could directly regulate the Ulk1–AMPK interaction by phosphorylating Ulk1. Immunoprecipitated Ulk1 was incubated with mTORC1 in vitro and then used to pulldown AMPK. Pre-incubation with mTORC1 significantly reduced the ability of Ulk1 to pulldown AMPK (Fig. 4e). These data indicate that mTORC1 inhibits the Ulk1–AMPK interaction by directly phosphorylating Ulk1.

Figure 4.

mTORC1 disrupts the Ulk1–AMPK interaction. (a) AMPK interacts with Ulk1. HEK293 cells were transfected with the various Flag–Ulk1 deletion mutants together with AMPK α/β/γ, Atg13 and FIP200. Flag–Ulk1 protein (indicated by white arrows) was immunoprecipitated and co-immunoprecipitation of AMPK α/β/γ, Atg13 and FIP200 were examined by western blots. (b) Deletion analysis of Ulk1 regions responsible for AMPK interaction. The indicated Flag–Ulk1 truncation mutants were immunoprecipitated from transfected HEK293 cells co-expressing AMPK complex (α/β/γ). Co-immunoprecipitation of AMPK subunits was determined by western blots. (c) Rheb inhibits the Ulk1–AMPK interaction. HA–AMPKα, Flag–Ulk1 and Myc–Rheb were co-transfected into HEK293 cells as indicated. Cells were treated with or without rapamycin (50 nM Rapa) for 1 h before lysis. Flag–Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated and co-immunoprecipitates of AMPKα were determined by western blot. (d) Rapamycin treatment enhances the interaction of endogenous Ulk1 and AMPK. Endogenous Ulk1 proteins were immunoprecipitated from either Ulk1 or AMPK wild-type and knockout (single-knockout; KO or double-knockout; DKO) MEFs. Treatment with 50 nM rapamycin for 1 h is indicated (Rapa). Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous AMPKα protein was determined by western blot. The arrow indicates AMPKα protein. (e) Phosphorylation by mTORC1 inhibits the ability of Ulk1 to bind AMPK in vitro. CBP/SBP–Ulk1 was purified from transfected HEK293 cells by streptavidin beads and the Ulk1–bead complex was incubated with mTORC1, which was prepared by Raptor immunoprecipitation, in the presence of cold ATP, as indicated. The resulting Ulk1 complex was incubated with the cell lysates containing AMPK, then extensively washed. The Ulk1 and associated AMPKα were detected by western blot. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

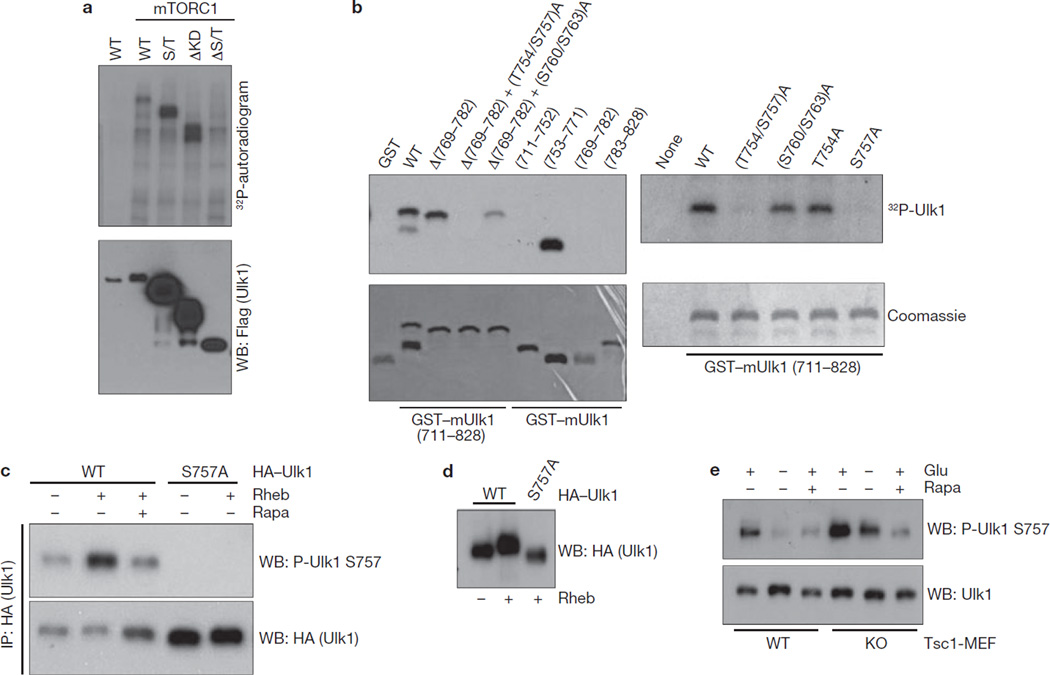

To understand the role of mTORC1 in Ulk1 regulation, we made efforts to identify the mTORC1 phosphorylation site in Ulk1. We tested phosphorylation of various Ulk1 deletions by mTORC1 in vitro. As shown in Fig. 5a, the Ulk1 S/T domain (residues 279–828) was phosphorylated by mTORC1. As mTORC1 phosphorylates the residue 651–1051 in vitro23, we assumed that mTORC1 might phosphorylate Ulk1 between residues 651 and 828. Of note, this region includes the fragment (711–828) required for AMPK interaction. Therefore, we examined the phosphorylation of Ulk1 fragment (711–828) by mTORC1. Ulk1 (711–828) was phosphorylated by mTORC1, but not by mTORC2 (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3a). Further deletion and mutagenic analyses identified Ser 757 as the mTORC1 phosphorylation site in this fragment (Fig. 5b). Using the antibody specific to phosphorylated Ser 757, we found that Ser 757 phosphorylation was increased when mTORC1 was activated by Rheb co-expression, and that rapamycin treatment inhibited the effect of Rheb (Fig. 5c). As expected, this phosphorylation was not detected in the Ulk1S757A mutant, confirming the specificity of the antibody. Consistently, we observed that Rheb overexpression induced an Ulk1 mobility shift and this shift was abolished in the Ulk1S757A mutant (Fig. 5d), suggesting that Ser 757 is the major mTORC1 phosphorylation site in vivo. We also mapped the amino-terminal region of Ulk1 as an important domain for Raptor binding (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3b), which is a substrate-recruiting subunit of mTORC146. To further evaluate a role for mTORC1 in Ulk1 phosphorylation, we examined Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation in the Tsc1−/− MEF, which has an elevated mTORC1 activity47. Phosphorylation of endogenous Ulk1 Ser 757 was increased in the Tsc1−/− MEF, but it was still inhibited by rapamycin (Fig. 5e), confirming the dependence of Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation on mTORC1 activity. Also, glucose starvation, which inhibits mTORC1, decreased endogenous Ser 757 phosphorylation (Fig. 5e). The decrease of Ser 757 phosphorylation by glucose starvation was compromised in the Tsc1−/− MEFs, consistent with an inefficient mTORC1 inhibition by glucose starvation in the Tsc mutant cells38. AMPK is required for mTORC1 inhibition in response to glucose starvation38–39. Consistently, glucose starvation was less effective to decrease Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation in the AMPK DKO MEFs (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3c), further supporting a role for mTORC1 in Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

mTORC1 phosphorylates Ulk1 at Ser 757. (a) mTORC1 phosphorylates the Ulk1 S/T domain. Ulk1 deletion mutants were prepared from the transfected HEK293 cells and used for in vitro mTORC1 assay. Phosphorylation was examined by 32P-autoradiogram (top) and protein level was determined by western blot (bottom). (b) Ser 757 is phosphorylated by mTORC1. Left: the indicated recombinant GST–mUlk1 mutants were purified from E. coli and used for in vitro mTORC1 assay as substrates. Deletion analyses isolated the fragment (753–771) as a target for mTORC1. The Ulk1 (753–771) fragment contains five conserved serine/threonine residues, Thr 754, Ser 757, Ser 760, Thr 763 and Thr 770. Right: mutation of Ser 757 abolished Ulk1 phosphorylation by mTORC1 in vitro. GST was used as negative control for mTORC1 phosphorylation reaction. Phosphorylation was determined by 32P-autoradiograph (top), whereas protein levels were detected by Coomassie staining (bottom). (c) Rheb increases Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation. HA–Ulk1 wild type and the S757A mutant were immunoprecipitated from transfected HEK293 cells. Co-transfection with Rheb and rapamycin (Rapa) treatment are indicated. Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation was determined by western blot. (d) Rheb induces a mobility shift in wild-type Ulk1, but not the Ulk1S757A mutant. HA–Ulk1 was transfected with or without Rheb into HEK293 cells. HA–Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated from the cells under nutrient-rich medium and Ulk1 mobility was examined by western blot. (e) Endogenous Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation is elevated in Tsc1−/− MEFs. Tsc1+/+ (WT) and Tsc1−/− (KO) MEFs were starved of glucose (4 h), or treated with 50 nM rapamycin (Rapa, 1 h). Ser 757 phosphorylation of endogenous Ulk1 was detected by a phospho-Ulk1 Ser 757 antibody. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

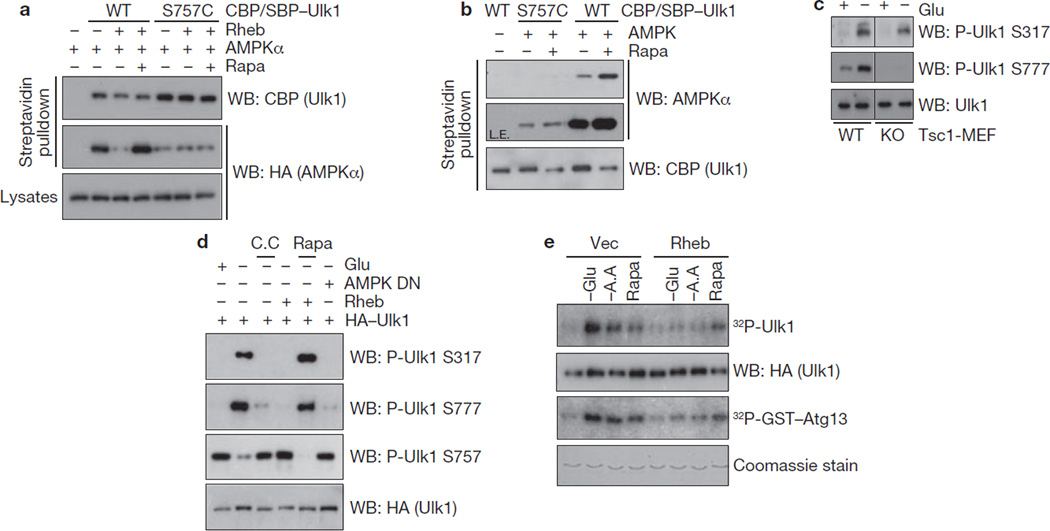

Next, we determined the effect of the mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation on the Ulk1–AMPK interaction. Ulk1 Ser 757 was mutated to either aspartate or alanine and we found that both mutations greatly diminished the Ulk1–AMPK interaction (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3d). This was not simply because of a global structural alteration of the mutation because Ulk1S757A could still associate with Atg13 and FIP200 (data not shown). Therefore, we speculated that the chemistry of this position (hydroxyl group) is critical for AMPK interaction. We replaced Ser 757 with a cysteine residue, which is structurally close to serine, and found that it retained some interaction with AMPK although weaker (Supplementary Information, Fig. S3d). Importantly, the interaction between the S757C mutant and AMPK was no longer regulated by Rheb overexpression or rapamycin treatment as determined by co-immunoprecipitation in vivo (Fig. 6a). Moreover, in an in vitro pulldown assay, wild-type Ulk1 prepared from rapamycin-treated cells had a stronger binding to AMPK than the Ulk1 prepared from the cells cultured in nutrient-rich conditions (Fig. 6b). However, the effect of rapamycin to increase the Ulk1–AMPK interaction was not observed in the S757C mutant. These data indicate that phosphorylation of Ser 757 by mTORC1 is important to regulate the Ulk1–AMPK interaction. Consistent with this hypothesis, phosphorylation of the two AMPK sites, Ser 317 and Ser 777, was suppressed in Tsc1−/− MEFs (Fig. 6c) or by Rheb co-transfection (Fig. 6d), both of which are conditions that result in high-mTORC1 activity. As shown in Fig. 6d, the phosphorylations of AMPK site Ser 317 and Ser 777 and of mTORC1 site Ser 757 were reciprocally regulated by the conditions that activate or inhibit AMPK and mTORC1. Glucose starvation decreased Ulk1 Ser 757 phosphorylation but increased Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation. As expected, the glucose starvation effect was blocked by compound C. In contrast, Rheb stimulated Ser 757 phosphorylation but inhibited Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation and these effects were reversed by rapamycin. Furthermore, overexpression of Rheb suppressed glucose-starvation induced Ulk1 activation, as demonstrated by autophosphorylation and transphosphorylation of GST–Atg13 (Fig. 6e). These data suggest that mTORC1 disrupts the interaction between Ulk1 and AMPK through phosphorylation of Ulk1 Ser 757, thereby preventing Ulk1 activation by AMPK.

Figure 6.

Phosphorylation of Ulk1 Ser 757 by mTORC1 inhibits the Ulk1–AMPK interaction. (a) Ulk1 Ser 757 is required for mTORC1 to regulate the interaction of Ulk1 with AMPK in vivo. CBP/SBP tagged Ulk1 (wild type or S757C) was co-transfected with HA–AMPKα and Rheb into HEK293 cells as indicated. Ulk1 was purified by streptavidin beads and the co-precipitated HA–AMPKα was examined by western blot (Rapa, 50 nM rapamycin treatment for 1 h before cell lysis). (b) Ulk1 Ser 757 is required for rapamycin to enhance the Ulk1–AMPK interaction in vitro. CBP/SBP Ulk1 proteins (wild type or S757C) were prepared from transfected HEK293 cells, which were pre-incubated with 50 nM rapamycin (Rapa, 1h) as indicated. The Ulk1 proteins were purified by streptavidin beads and the resulting Ulk1–bead was incubated with the bacterial purified AMPKα/β/γ complex. AMPKα protein levels in the in vitro pulldown assays were examined by western blot using AMPKα antibody. L.E.; long exposure. (c) Phosphorylation of AMPK sites Ser 317 and Ser 777 in Ulk1 are decreased in Tsc1−/− MEFs. Tsc1+/+ (WT) and Tsc1−/− (KO) MEFs were starved of glucose (4 h), or treated with 50 nM rapamycin (Rapa, 1 h). Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation of endogenous Ulk1 was examined by western blotting with antibodies against Ulk1 phosphorylated at Ser 317 or Ser 777. (d) Rheb suppresses Ulk1 Ser 317 and Ser 777 phosphorylation in a manner dependent on mTORC1. HA–Ulk1, AMPKα kinase-dead mutant (DN), and Myc–Rheb were co-transfected into HEK293 cells as indicated. The cells were incubated with glucose-free medium (−Glu, 4 h), in which either 20 µM compound C (C.C.) or 50 nM Rapamycin (Rapa) was added. Total cell lysates were probed with antibodies against Ulk1 phosphorylated at Ser 317, Ser 777, Ser 757, and HA, as indicated. (e) Rheb inhibits glucose starvation-induced Ulk1 activation. HA–Ulk1 and Myc–Rheb was transfected into HEK293 cells, which were incubated with glucose-free (−Glu), amino-acid-free (−A.A) medium, or 50 nM rapamycin (Rapa) for 4 h before lysis. HA–Ulk1 was immunoprecipitated and kinase assays were performed. Ulk1 activity was measured by 32P-autoradiogram and the protein level of HA–Ulk1 and GST–Atg13 used in the assay was determined by western blot and by Coomassie staining, respectively. Uncropped images of blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S5.

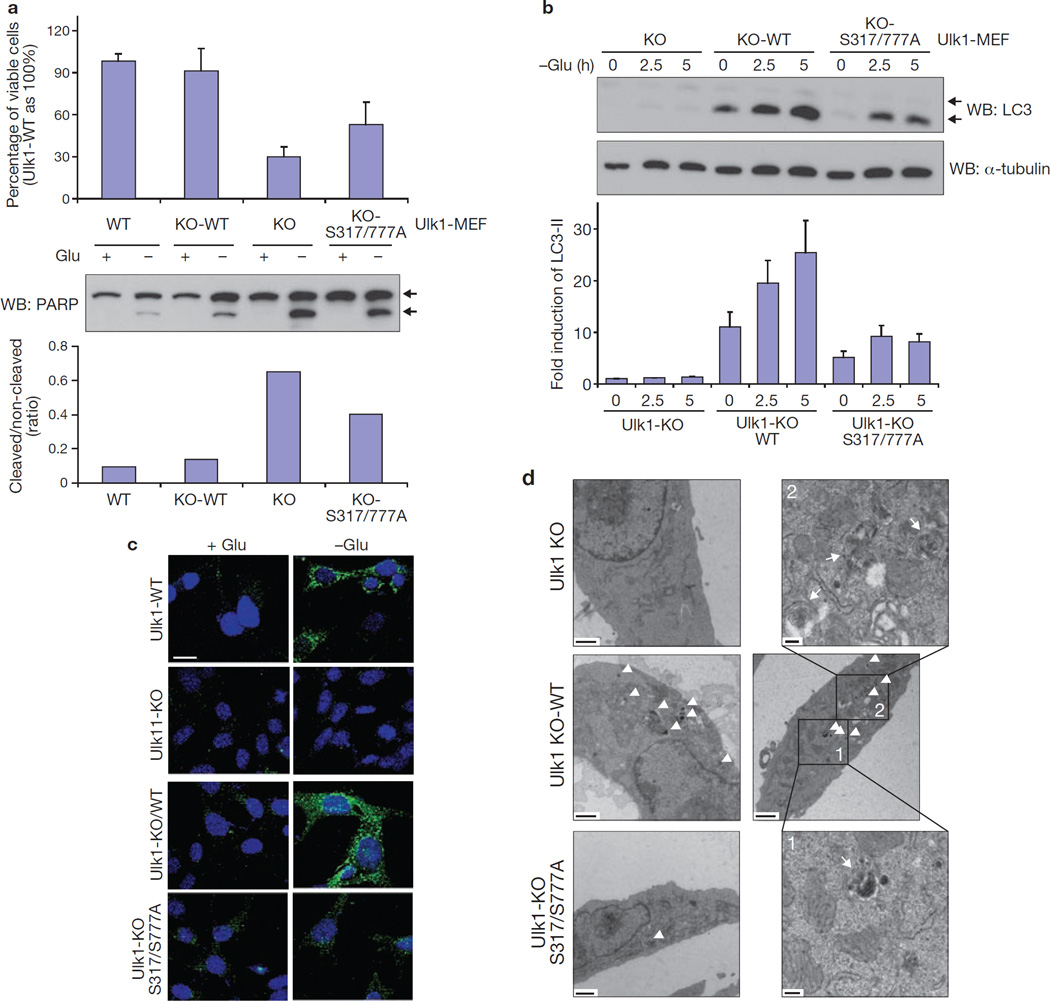

The AMPK phosphorylation is required for Ulk1 function in autophagy

To determine the biological function of Ulk1 phosphorylation by AMPK, Ulk1 wild type and the S317/777A mutant were introduced into the Ulk1−/− MEFs (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4a). GFP–LC3 was also introduced into these MEFs to monitor GFP–LC3 positive autophagic vesicles (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4b). The Ulk1−/− (KO) cells were sensitive to glucose starvation with marked apoptosis (Fig. 7a). Knockdown of Ulk2 did not further sensitize the Ulk1−/− cells to glucose starvation (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4c), indicating that Ulk2 has a minor role in the MEF cells. The Ulk1−/− cells were defective in autophagy as indicated by LC3 lipidation, GFP–LC3 puncta formation, and autophagosome/autolysosome formation42 (Fig. 7b–d). Expression of wild-type Ulk1 (KO-WT) rescued all defective phenotypes in the Ulk1−/− cells. In contrast, the Ulk1S317/777A mutant (KO-S317/777A) was less effective in protecting cells from glucose starvation-induced apoptosis (Fig. 7a). The glucose starvation-induced autophagy was also significantly compromised in cells expressing the Ulk1S317/777A mutant as indicated by LC3 lipidation (Fig. 7b and Supplementary Information Fig. S4d). As expected, glucose starvation increased autophagic flux in the wild type but not the Atg5−/− or Ulk1−/− cells (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4d). Re-expression of Ulk1 but not the S317/777A mutant restored autophagy. Consistently, Ulk1−/− cells expressing Ulk1S317/777A were defective in GFP–LC3 aggregation (Fig. 7c, S4e), and autophagosome/autolysosome formation (Fig. 7d, S4f). Based on the above data, we conclude that activation of Ulk1 through phosphorylation of Ser 317/Ser 777 by AMPK has a critical role in autophagy induction in response to glucose starvation.

Figure 7.

AMPK phosphorylation is required for Ulk1 function in autophagy on glucose starvation. (a) Ser 317/Ser 777 is required for Ulk1 to protect cells from glucose starvation. Viability (24 h, mean ± s.d., n = 4; top) and PARP cleavage (8 h; western blot, middle; quantification, n = 2, bottom) was examined in Ulk1+/+ (WT), Ulk1−/− (KO), Ulk1−/− re-expressing wild-type Ulk1 (KO-WT), and Ulk1−/− re-expressing Ulk1 S317/777A mutant (KO-S317/777A) MEFs. Arrows in western blot indicate non-cleaved and cleaved PARP. (b) The Ulk1 S317/777A mutant is compromised in LC3 lipidation in response to glucose starvation. ULK1 MEFs were cultured in glucose-free medium for the indicated times. LC3-II level was determined by western blotting and the LC3-II accumulation was normalized by α-tubulin and quantified (bottom, n = 3, mean ± s.d.). A representative western blot was shown. The LC3 antibody used in this experiment seemed to preferentially recognise the lipid-modified form of LC3-II, which migrated faster on the gel. (c) The Ulk1 S317/777A mutant is defective in autophagosome formation. The indicated MEFs were starved of glucose (4 h) and the formation of GFP–LC3-positive autophagosomes was examined by confocal microscopy. GFP–LC3; green and DAPI; blue. Scale bar, 20 µm. (d) Autophagy vacuole analysis by electron microscopy. Low-magnification images of Ulk1−/− (KO, upper left panel), Ulk1−/− reconstituted with wild-type Ulk1 (KO-WT, two middle panels with accompanying higher magnification images), and Ulk1−/− reconstituted with Ulk1 S317/777A (KO-S317/777A, lower left panel) are shown. High-magnification images of autophagosomes from KO-WT are shown in upper right and lower right panels. Autophagosome/autolysosome-like structures indicated by arrowheads on the lower-magnification images and arrows in higher-magnification images. Scale bars; lower-magnification, 1 µm; higher-magnification, 200 nm.

DISCUSSION

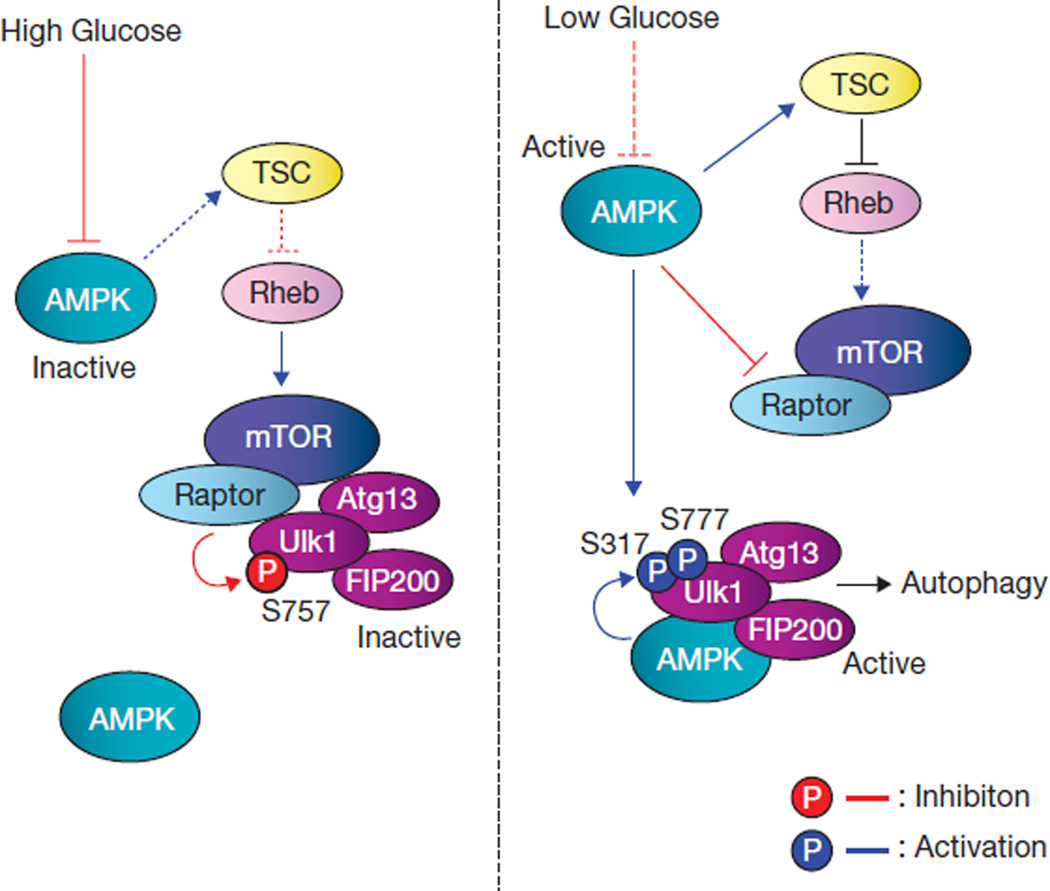

As an autophagy-initiating kinase, the mechanism of Ulk1 regulation is central to understanding autophagy regulation. This study demonstrates a biochemical mechanism of Ulk1 activation by upstream signals and the functional importance of this regulation in autophagy induction. AMPK senses cellular energy status and activates Ulk1 kinase by a coordinated cascade (Fig. 8). Under glucose starvation, the activated AMPK inhibits mTORC1 to relieve Ser 757 phosphorylation, leading to Ulk1–AMPK interaction. AMPK then phosphorylates Ulk1 on Ser 317 and Ser 777, activates Ulk1 kinase, and eventually leads to autophagy induction. Notably, a recent autophagy-interaction proteome48 and co-immunoprecipitation study49 have also shown a physical interaction between Ulk1 and AMPK, consistent with our findings. Although AMPK may phosphorylate additional sites that may contribute to Ulk1 activation, phosphorylation of Ser 317/Ser 777 is required for Ulk1 activation and efficient autophagy induction in response to glucose starvation. We noticed that Ser 777 in the mouse Ulk1 is not conserved in human Ulk1, indicating that phosphorylation of other sites in human Ulk1 by AMPK may also contribute to its activation in response to glucose starvation. Moreover, Ser 317 and Ser 777 did not match the AMPK consensus motifs39,50. Interestingly, both Ser 317 and Ser 777 are positioned at three residues C-terminal to the putative AMPK consensus sites, Ser 314 and Ser 774. Future studies are needed to test whether this represents a new AMPK recognition motif.

Figure 8.

Model of Ulk1 regulation by AMPK and mTORC1 in response to glucose signals. Left: when glucose is sufficient, AMPK is inactive and mTORC1 is active. The active mTORC1 phosphorylates Ulk1 on Ser 757 to prevent Ulk1 interaction with and activation by AMPK. Right: when cellular energy level is limited, AMPK is activated and mTORC1 is inhibited by AMPK through the phosphorylation of TSC2 and Raptor. Phosphorylation of Ser 757 is decreased, and subsequently Ulk1 can interact with and be phosphorylated by AMPK on Ser 317 and Ser 777. The AMPK-phosphorylated Ulk1 is active and then initiates autophagy.

TORC1 is one of the most important autophagy regulators. Recently, DAP1 (death-associated protein 1) has been reported as a novel mTORC1 substrate and has an inhibitory role in autophagy 51. Here, we show that mTORC1 inhibits Ulk1 activation by phosphorylating Ulk1 Ser 757 and disrupting its interaction with AMPK. Our study expands the mTORC1 regulatory networks, where Ulk1 phosphorylation represents the catabolic arm of mTORC1 biology. However, it is worth noting that inhibition of mTORC1 by amino-acid starvation or rapamycin treatment can activate Ulk1 in an AMPK-independent manner as these conditions are sufficient to activate Ulk1 and induce autophagy, but do not activate AMPK. Therefore, future studies are needed to have a comprehensive understanding of Ulk1 regulation, especially in response to amino-acid starvation.

The coordinated phosphorylation of Ulk1 by mTORC1 and AMPK may provide a mechanism for signal integration and, thus cells can properly respond to the complex extracellular milieu. For example, under conditions of moderate glucose limitation and sufficient amino acids, it is advantageous for cells to modulate metabolism but not to initiate autophagy. Under such conditions, activation of AMPK should alter cellular metabolism by phosphorylating metabolic enzymes to promote aminoacid utilization for energy production. Although AMPK would suppress mTORC1, mTORC1 should not be completely inhibited when amino acids are available. The residual mTORC1 activity may prevent Ulk1 activation, thus minimizing autophagy initiation. Therefore, the phosphorylation of Ulk1 by mTORC1 and AMPK may ensure that autophagy is not initiated unless severe starvation conditions are experienced.

The identification of Ulk1 as a direct target of mTORC1 and AMPK represents a significant step towards the understating how cellular nutrient sensor/integrator regulates autophagy machinery. Further studies directed at identifying physiological substrates of Ulk1 will be essential to understand how Ulk1 activation results in initiation of the autophagy programme.

METHODS

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-PARP (#9542, 1:1,000), AMPKα (#2532, 1:1,000) and LC3 (#2775, 1:2,000) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling technology. Anti-Ulk1 (A7481, 1:1,000), and α-tubulin (T6199, 1:10,000) antibodies were obtained from Sigma, Anti-HA (1:4,000) and Myc antibodies (1:4,000) were from Covance. Anti-phosphorylated Ser 317 and Ser 757 antibodies were generated by immunizing rabbits with phosphopeptides. The phospho-specific antibodies were affinity purified (Cell Signaling Technology). Anti-phospho Ser 777 antibody was prepared by immunizing rabbits (Biomyx). HA–Ulk1 wild-type and GFP–LC3 expression constructs were provided by J. Chung (Seoul National University, Korea) and N. Mizushima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Japan), respectively. Mutagenesis was performed based on Quik-Change mutagenesis (Stratagene).

Cell culture, transfection and viral infection

HEK293 cells or HEK293T were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 50 µg ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin. The MEFs were grown in the DMEM culture medium (complete medium) supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), 1 mM pyruvate and non-essential amino-acid mixture (Invitrogen). Transfection with polyethylenimine (PEI) was performed as described3. To generate stable cells expressing wild-type or the indicated mutant mouse Ulk1 (mUlk1) proteins, retrovirus infection was performed by transfecting 293 Phoenix retrovirus packaging cells with pQCXIH (Clontech) empty vector or mUlk1 constructs expressing CBP (Calmodulin-binding peptide)/SBP (streptavidin-binding peptide) at the N-terminus of the mUlk1 protein. After transfection (48 h), retroviral supernatant was supplemented with 5 µg ml−1 polybrene, filtered through a 0.45-µm syringe filter, and used to infect Ulk1−/− (Ulk1-KO) MEFs. After infection (36 h), cells were selected with 0.2 mg ml−1 hygromycin (Invitrogen) in the complete culture medium. To establish Ulk2 knockdown stable cells in the Ulk1-KO background, lentiviral construct (pLKO.1-TRC system, Addgene) containing shRNA targeting mouse Ulk2 (2592–2612, Forward oligonucleotide: 5′- CCGGaaccctgagctgtgcacatctCTCGAGAGATGTGCACAGCTCAGGGTTTTTTTC-3′; Reverse oligonucleotide: 5′- AATTGAAAAAaaccctgagctgtgcacatctCTCGAGAGATGTGCACAGCTCAGGGTT-3′; lower case characters and italic characters are the sense and antisense sequences for the targeting region, respectively) was generated and co-transfected with viral packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G) into HEK293T cells. Viral supernatant was filtered through 0.45-µm filter and applied to Ulk1-KO MEFs. Stable pools were obtained in the presence of 5 µg ml−1 puromycin (Sigma).

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed with mild lysis buffer (MLB; 10 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitor cocktail; Roche). These cell lysates were used for western analyses. For immunoprecipitation, the indicated antibody was coupled with protein G–Sepharose (Amersham bioscience) in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST (20 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 170 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween-20). This immune complex was added to the cell lysates and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h. The resulting beads were washed with MLB five times before analysis.

Cell death assay

Cell viability was determined by cell counting with trypan blue staining (Sigma, T8154) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Also, poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), an apoptotic marker protein, was examined by western blot. The index of apoptosis was determined by the ratio between the cleaved and noncleaved PARP protein level. The band intensity was quantified on ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

Protein purification and kinase assay

Bacterial expression constructs (pGEXKG) containing the indicated genes were transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α. Cells were induced to protein overexpression under 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside) at 18 °C. Cells were resuspended in PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, followed by ultrasonication. The proteins were purified by a single step using glutathione bead according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Amersham Bioscience). Purified proteins were dialysed against 20 mM Tris at pH 8.0, and 10% glycerol. Purified bacterial GST–Ulk1 proteins (0.5 µg) were used for either mTOR or AMPK assay as substrates to determine phosphorylation sites. For mTOR assay, mTORC1 was prepared from the HEK293 cells, where Myc-mTOR and HA–Raptor were co-transfected. mTORC1 was immunoprecipitated by Raptor and eluted from the bead by adding the excess amount of HA peptide, followed by desalting with desalting spin column. For AMPK assay, 10 ng of purified AMPK α/β/γ complex (Cell signaling technology) was used. mTORC1 (ref. 4) and AMPK (ref. 5) assay were performed as previously described. Phosphorylation of GST–Ulk1 proteins was determined by 32P-autoradiogram.

In vitro Ulk1 kinase assay

Ulk1 proteins were immunoprecipitated with either HA (Covance) or endogenous Ulk1 (Santa Cruz, N-17) antibodies as indicated. The immune-complex was extensively washed with MLB (once) and RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.05% SDS, 1% Triton X-100 and 0.5% deoxycholate) twice, followed by washing with kinase assay buffer containing 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 1 mM EGTA, 0.4 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2 and 0.05 mM DTT (dithiothreitol). For Ulk1 autophosphorylation assay, the immunoprecipitated Ulk1 bead was incubated in kinase assay buffer containing 10 µM cold ATP and 2 µCi [γ-32P]ATP per reaction. For kinase assays with GST–ATG13 and/or FIP200, GST–ATG13 was bacterially purified and HA–FIP200 proteins were immunopurified from the transfected HEK293 cells and eluted by adding the excess amount of HA peptide (Sigma). HA peptide was removed by desalting spin column (Pierce). The kinase reaction was performed at 37 °C for 30 min and the reaction was terminated by adding SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS–PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and autoradiography.

Lambda phosphatase/AMPK treatment in vitro

To evaluate the effects of phosphorylation on Ulk1 kinase activity, Ulk1 was pre-incubated with either lambda phosphatase or AMPK in vitro. First, the cells were starved of glucose (4 h) and then Ulk1 (endogenous Ulk1 or HA–tagged Ulk1) was immunoprecipitated as indicated. The Ulk1 immune-complex was incubated with either 5U lambda phosphatase (Cell signaling technology) in the phosphatase buffer or 5 ng of purified AMPK (Cell Signaling Technology) in kinase assay buffer supplemented with 0.2 mM AMP and 0.1 mM cold ATP, for 15 min. The Ulk1-bound beads were extensively washed with RIPA buffer and kinase assay buffer and recovered by centrifugation. The resulting Ulk1–bead was assayed for Ulk1 autophosphorylation and/or for GST–ATG13 phosphorylation in the presence of [32P]ATP. To rule out the possibility that residual AMPK or lambda phosphatase contamination might affect Ulk1 autophosphorylation (or GST–ATG13 phosphorylation), autophosphorylation of kinase-inactive Ulk1 (K46R) or dephosphorylation of 32P-prelabelled GST–TSC2 (phosphorylation on Ser 1345 in the TSC2 fragment 1300–1367) were examined as controls for AMPK and lambda phosphatase, respectively.

In vitro pulldown assay

CBP/SBP–Ulk1 (wild type or S757C mutant) and Myc–Rheb were co-transfected into HEK293 cells as indicated. The cells were treated with or without 50 nM rapamycin for 1 h and then Ulk1 proteins were purified by streptavidin beads. The resulting Ulk1–beads were incubated with the bacterial purified AMPKα/β/γ complex and recovered by centrifugation. The beads were extensively washed with MLB. For in vitro Ulk1 phosphorylation by mTOR, CBP/SBP–Ulk1 proteins were purified from the transfected HEK293 cells, which were incubated with 50 nM rapamycin for 1 h to remove any mTORC1-induced phosphorylation on Ulk1, and then incubated with mTORC1 in kinase assay buffer supplemented with 20 µM cold ATP for 30 min. The Ulk1 immune-complex was extensively washed with RIPA buffer and recovered by centrifugation. The resulting Ulk1 proteins were incubated with 100 ng of bacterially purified AMPK α/β/γ complex or the total cell lysates including endogenous AMPK complex for 15 min at 4 °C, followed by MLB washing three times. The proteins on beads were eluted by adding SDS/sample buffer and subjected to SDS–PAGE and western blot using Ulk1 and AMPKα antibodies.

GFP–LC3 fluorescence analysis

MEFs stably expressing GFP–LC3 were plated onto glass coverslips. The following day, the medium was replaced with the complete culture medium for 4 h before experiment. Autophagy was induced by glucose starvation for 4 h. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and rinsed with PBS twice. Cells were mounted and visualized under a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM, ×64 PlanAPO oil lens). To quantify GFP–LC3-positive autophagosomes, five different confocal microscopy images were randomly chosen and GFP-positive dots were examined on the images with identical brightness and contrast setting. Cells showing more than five strong GFP-positive dots were counted as GFP–LC3 autophagosomes. Total number of cells on images was determined by nuclei staining with DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole).

Electron microscopy

MEFs were fixed in modified Karnovsky’s fixative (1.5% glutaraldehyde, 3% paraformaldehyde and 5% sucrose in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer at pH 7.4) for 8 h, followed by treatment with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for an additional 1 h. They were stained in 1% uranyl acetate and dehydrated in ethanol. Samples were embedded in epoxy resin, sectioned (60–70 nm), and placed on Formvar and carbon-coated copper grids. Grids were stained with uranyl acetate and lead nitrate, and the images were obtained using a JEOL 1200EX II (JEOL) transmission electron microscope and photographed on a Gatan digital camera (Gatan).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank members of the Guan lab for discussions and reagents. We would especially like to thank I. Lian and C. Fang for technical assistance, and M. Farquhar, K. Kudicka and T. Meerloo for help with the electron microscopy. This work was supported by NIH grants GM51586 and GM62694 (to K.-L.G.).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Information is available on the Nature Cell Biology website

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.K. performed the experiments; M.K. and B.V. established the AMPK and Ulk1 knockout MEFs, respectively; J.K. and K.-L.G. designed the experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang RC, Levine B. Autophagy in cellular growth control. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1417–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hara T, et al. FIP200, a ULK-interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stipanuk MH. Macroautophagy and its role in nutrient homeostasis. Nutr. Rev. 2009;67:677–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang J, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy and human disease. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1837–1849. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.15.4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang C, Jung JU. Autophagy genes as tumor suppressors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar S, Rubinsztein DC. Huntington’s disease: degradation of mutant huntingtin by autophagy. FEBS J. 2008;275:4263–4270. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadwell K, Stappenbeck TS, Virgin HW. Role of autophagy and autophagy genes in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;335:141–167. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerena MC, Vazquez CL, Colombo MI. Bacterial pathogens and the autophagic response. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tal MC, Iwasaki A. Autophagy and innate recognition systems. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009;335:107–121. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:458–467. doi: 10.1038/nrm2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:1102–1109. doi: 10.1038/ncb1007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue Y, Klionsky DJ. Regulation of macroautophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;21:664–670. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizushima N. The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan EY, Tooze SA. Evolution of Atg1 function and regulation. Autophagy. 2009;5:758–765. doi: 10.4161/auto.8709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamada Y, et al. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1507–1513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabeya Y, et al. Atg17 functions in cooperation with Atg1 and Atg13 in yeast autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:2544–2553. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang YY, Neufeld TP. An Atg1/Atg13 complex with multiple roles in TOR-mediated autophagy regulation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:2004–2014. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan EY, Kir S, Tooze SA. siRNA screening of the kinome identifies ULK1 as a multidomain modulator of autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:25464–25474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young AR, et al. Starvation and ULK1-dependent cycling of mammalian Atg9 between the TGN and endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:3888–3900. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganley IG, et al. ULK1.ATG13.FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:12297–12305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosokawa N, et al. Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy. 2009;5:973–979. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung CH, et al. ULK–Atg13–FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1992–2003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudarsanam S, Johnson DE. Functional consequences of mTOR inhibition. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2010;13:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung CH, Ro SH, Cao J, Otto NM, Kim DH. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang YY, et al. Nutrient-dependent regulation of autophagy through the target of rapamycin pathway. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37:232–236. doi: 10.1042/BST0370232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamada Y, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y. Autophagy in yeast: a TOR-mediated response to nutrient starvation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2004;279:73–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18930-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Funakoshi T, Matsuura A, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. Analyses of APG13 gene involved in autophagy in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1997;192:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamada Y, et al. Tor directly controls the Atg1 kinase complex to regulate autophagy. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;30:1049–1058. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01344-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosokawa N, et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1–Atg13–FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1981–1991. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardie DG. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:774–785. doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vingtdeux V, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling activation by resveratrol modulates amyloid-β peptide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:9100–9113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrero-Martin G, et al. TAK1 activates AMPK-dependent cytoprotective autophagy in TRAIL-treated epithelial cells. EMBO J. 2009;28:677–685. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsui Y, et al. Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ. Res. 2007;100:914–922. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261924.76669.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang J, et al. The energy sensing LKB1-AMPK pathway regulates p27(kip1) phosphorylation mediating the decision to enter autophagy or apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:218–224. doi: 10.1038/ncb1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meley D, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase and the regulation of autophagic proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34870–34879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gwinn DM, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kinoshita E, Kinoshita-Kikuta E, Takiyama K, Koike T. Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:749–757. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500024-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou G, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151–175. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawley SA, Gadalla AE, Olsen GS, Hardie DG. The antidiabetic drug metformin activates the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade via an adenine nucleotide-independent mechanism. Diabetes. 2002;51:2420–2425. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1829–1834. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, et al. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:578–581. doi: 10.1038/ncb999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schalm SS, Fingar DC, Sabatini DM, Blenis J. TOS motif-mediated raptor binding regulates 4E-BP1 multisite phosphorylation and function. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JW, Park S, Takahashi Y, Wang HG. The association of AMPK with ULK1 regulates autophagy. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott JW, Norman DG, Hawley SA, Kontogiannis L, Hardie DG. Protein kinase substrate recognition studied using the recombinant catalytic domain of AMP-activated protein kinase and a model substrate. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:309–323. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koren I, Reem E, Kimchi A. DAP1, a novel substrate of mTOR, negatively regulates autophagy. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1093–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.