Abstract

Four conserved signaling pathways, including the bone morphogenetic proteins (Bmp), fibroblast growth factors (Fgf), Sonic hedgehog (Shh), and Wingless-related (Wnt) pathways, are each repeatedly used throughout tooth development. Inactivation of any of these resulted in early tooth developmental arrest in mice. The mutations identified thus far in human patients with tooth agenesis also affect these pathways. Recent studies show that these signaling pathways interact through positive and negative feedback loops to regulate not only morphogenesis of individual teeth but also tooth number, shape, and spatial pattern. Increased activity of each of the Fgf, Shh, and canonical Wnt signaling pathways revitalizes development of the physiologically arrested mouse diastemal tooth germs whereas constitutive activation of canonical Wnt signaling in the dental epithelium is able to induce supernumerary tooth formation even in the absence of Msx1 and Pax9, two transcription factors required for normal tooth development beyond the early bud stage. Bmp4 and Msx1 act in a positive feedback loop to drive sequential tooth formation whereas the Osr2 transcription factor restricts Msx1-mediated expansion of the mesenchymal odontogenic field along both the buccolingual and anteroposterior axes to pattern mouse molar teeth in a single row. Moreover, the ectodermal-specific ectodysplasin (EDA) signaling pathway controls tooth number and tooth shape through regulation of Fgf20 expression in the dental epithelium, whereas Shh suppresses Wnt signaling through a negative feedback loop to regulate spatial patterning of teeth. In this article, we attempt to integrate these exciting findings in the understanding of the molecular networks regulating tooth development and patterning.

Keywords: tooth development, dentition, signaling network, revitalization, Msx1, Osr2

1. Introduction

Cell-cell interactions through signal transduction pathways are crucial for the development of all multicellular organisms. Despite the enormous number of distinct cell types and a wide variety of tissue structures and patterns in the animal kingdom, a few conserved cell-cell signaling pathways, including the fibroblast growth factor (Fgf), hedgehog, transforming growth factor-beta (Tgfβ) and wingless-related (Wnt) signaling, are used repeatedly to regulate most of the developmental programs within individual animals and throughout vertebrate evolution 1. Whereas decades of genetic and biochemical studies have identified many of the molecular components of each of these signaling pathways and revealed extensive cross-talk among them, the detailed mechanisms regarding how they are modulated and how new components are integrated into existing signaling networks to control morphogenesis and patterning during mammalian organogenesis remain to be elucidated.

Teeth, like many organs, form through sequential and reciprocal inductive interactions between the adjacent epithelium and mesenchyme 2–5. Tooth development is largely independent from the rest of the body, and isolated, even dissociated and recombined, mammalian tooth germs can continue to develop to mineralized teeth upon transplantation to ectopic sites in adult animals 6, 7, such as the renal capsule. Thus, tooth development has long been used as a model for studying inductive interactions regulating organogenesis. In addition to allowing detailed analysis of the mechanisms regulating initiation, morphogenesis, and maturation of the individual organ, teeth exhibit species-specific number, shape, and patterns, and therefore provide a general paradigm for the studies of molecular mechanisms of developmental patterning and of evolution 8, 9. Through combinations of experimental embryological manipulations and transgenic and gene knockout studies in mice, research in the past twenty years have investigated the roles of each of the major signaling pathways in tooth organogenesis 2–5, 10–13. Whereas many mutant mice exhibit tooth developmental arrest phenotypes and revealed requirements of particular genes and pathways for specific steps of tooth organogenesis 10, several transgenic or gene-knockout mutant mouse strains exhibit alterations in the number, shape, and/or pattern of teeth, of which recent studies have provided fascinating new insights into the integration of signaling networks regulating tooth organogenesis and dentition patterning 13. Many review articles published previously provide excellent references on the progress in the studies of the molecular mechanisms of tooth development 2–5, 9–13. In this review, we highlight the integration of the actions of networks of activators and inhibitors of the Bmp (bone morphogenetic proteins, members of the Tgfβ superfamily), Fgf, Shh, and Wnt signaling pathways in the regulation of tooth morphogenesis and spatial patterning of the dentition.

2. The Bmp, Fgf, Shh, and Wnt signaling pathways are each repeatedly required for tooth initiation and morphogenesis

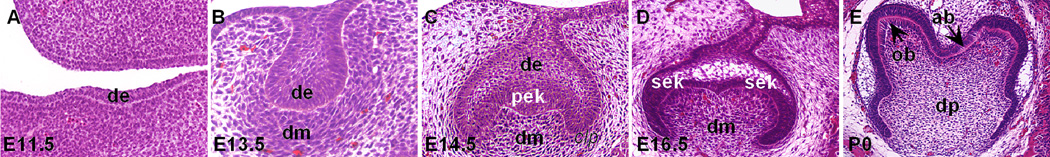

Whereas most of our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of tooth development has been derived from studies using mouse models, the basic steps of tooth organogenesis are similar in all vertebrates 8, 9. In mice, tooth development begins as a thickening of the oral epithelium, termed dental lamina (Figure 1A), at 11 days of gestation (E11). The dental lamina proliferates and buds into the underlying neural crest-derived mesenchyme and induces the mesenchyme to condense around the epithelial bud from E12 to E13 (Figure 1B). The dental mesenchyme in turn induces formation of an epithelial signaling center in the distal region of the epithelial bud, termed primary enamel knot, which drives tooth morphogenesis through the “cap” and “bell” stages (Figure 1C, D). As development proceeds, the epithelial cells in contact with the dental papilla mesenchyme differentiate into ameloblasts and the adjacent mesenchymal cells differentiate into odontoblasts (Figure 1E) 14. The ameloblasts and odontoblasts deposit enamel and dentin matrices, respectively back-to-back and subsequent mineralization of these matrices forms the hard tissues of the tooth 6. Thus, formation of each individual tooth, from its initiation through morphogenesis to cytodifferentiation, involves an extensive series of reciprocal interactions between the dental epithelium and the neural crest derived mesenchyme.

Figure 1.

Histology of first molar tooth development in mice. (A – E) Selected coronal sections of developing first molar tooth germs at dental lamina (E11.5, A), bud (E13.5, B), cap (E14.5, C), early bell (E16.5, D), and late bell (P0, E) stages are shown. ab, ameloblast; de, dental epithelium, dm, dental mesenchyme, dp, dental pulp; ob, odontoblast; pek, primary enamel knot; sek, secondary enamel knot.

2.1. Regulation of tooth initiation and tooth bud formation

At the beginning of tooth development, multiple members of the Bmp, Fgf, and Wnt families, including Bmp2, Bmp4, Bmp7, Fgf8, Fgf9, Wnt4, Wnt6, Wnt10a, and Wnt10b, and Shh are expressed in the presumptive dental epithelium15–22. Blocking each of these four signaling pathways at the beginning of tooth development genetically or in explant culture causes tooth developmental arrest at the dental lamina or early bud stage 4,5,7,10–12. Bmp and Fgf signaling is necessary for activation of expression of the Msx1 and Pax9 transcription factors, respectively, in the presumptive tooth mesenchyme 17,19,22, 23. Mice lacking either Msx1 or Pax9 function exhibit tooth developmental arrest at the bud stage 24, 25. Expression of Bmp4 shifts from the presumptive dental epithelium to the developing tooth mesenchyme at the early bud stage during normal tooth development and is significantly reduced in the developing tooth mesenchyme in either Msx1−/− or Pax9−/− mutant mice 17, 25, 26. In addition, Fgf8 induces Fgf3 expression in the dental mesenchyme in an Msx1-dependent manner 27. Although teeth develop nearly normally in Fgf3−/− mutant mice 28, 29, mice homozygous for null mutations in both Fgf3 and Fgf10, which are both expressed in the developing tooth mesenchyme, exhibit tooth developmental arrest at the bud stage 29. Fgf8 also induces expression of Inhibin-βA (Inhba) (also known as Activin-βA), another member of the Tgfβ superfamily, in the developing tooth mesenchyme 30. Mice lacking Inhba function exhibit early developmental arrest of incisors and mandibular molar tooth germs 30, 31. In addition, tissue-specific inactivation of the Bmp receptor gene Bmpr1a in either the neural crest lineage or the oral epithelium caused tooth developmental arrest at the bud stage 32–35. Mice with a deletion of the epithelial isoform of the type-2 Fgf receptor also exhibit tooth developmental arrest at the bud stage 36. Thus, both Bmp and Fgf signaling are critical for the reciprocal interactions between the epithelium and mesenchyme during early tooth development. On the other hand, although expression of the Wnt ligands is mostly restricted to the dental epithelium, with exception of expression of Wnt5a in the dental mesenchyme 21, tissue-specific inactivation of β-catenin, the obligatory intracellular mediator of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, in either the dental epithelium or the dental mesenchyme also caused tooth developmental arrest at the bud stage 37,38.

Recently, O’Connell et al. 39 analyzed properties of the gene regulatory networks mediating the reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during early mouse molar development through systematic analyses of previously reported gene expression data together with more than one hundred new microarray-based gene expression profiling datasets from isolated early tooth epithelial and mesenchymal tissues. They identified the Wnt and Bmp pathways as the two major mediators of epithelial-mesenchymal signaling in early tooth development. The Wnt and Bmp pathways collectively control the production of signaling molecules in all major pathways, including Bmp4, Shh, Fgfs, and Wnts in the epithelium and Fgfs, Bmp4, and Inhba in the mesenchyme of the early tooth germs 39. Whereas a simple ordinary differential equation model shows that the structure of a Wnt-Bmp feedback circuit recapitulates key features of the observed sequential and reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal signaling 39, the exact mechanisms that control the cross-regulation and integration of the Bmp, Fgf, Shh, and Wnt signaling pathways remain to be elucidated.

2.2. Formation of the primary enamel knot and tooth morphogenesis

Just prior to transition of the tooth bud to the cap stage, the primary enamel knot forms at the tip of the tooth bud and exhibits restricted expression of multiple members of the Bmp, Fgf, and Wnt families, including Bmp2, Bmp4, Bmp7, Fgf3, Fgf4, Fgf9, Fgf20, Wnt3, Wnt6, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, as well as Shh 4, 10–12, 17–21. The primary enamel knot has a central role in patterning the tooth crown by regulating growth and folding of the dental epithelium as well as regulating secondary enamel knot formation during molar development 3, 10, 40, 41. Interestingly, while the enamel knot expresses multiple Fgf ligands, expression of Fgf receptors is dramatically downregulated and, concomitantly, expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene p21 (also known as Cdkn1a) is highly activated in the enamel knot 41, 42. Thus, the enamel knot stimulates proliferation of the surrounding epithelial cells but cells within the enamel knot do not proliferate, causing epithelial folding to form the “cap” and subsequently “bell” shaped tooth germs 12.

Induction of the enamel knot depends on a combination of signals from the epithelium and mesenchyme. Of the mesenchymally expressed signals, Bmp4 is able to induce expression of several primary enamel knot markers, including p21 in isolated dental epithelium 41 as well as to rescue the bud-to-cap transition of the Msx1−/− mutant molar tooth germs in explant culture 26, 43. On the other hand, Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the dental epithelium plays a critical role in the induction and function of the enamel knot. Constitutive stabilization of β-catenin in the oral epithelium through direct overexpression using the human keratin-14 (K14) gene promoter as well as epithelial-specific deletion of Apc resulted in continuous formation of enamel knots in the dental epithelium and subsequently supernumerary tooth formation 44, 45. Deletion of Bmpr1a together with Apc in the oral epithelium, however, blocked enamel knot formation and resulted in tooth bud developmental arrest similar to that in mice lacking epithelial Bmpr1a alone 39, indicating that both Bmp and Wnt signaling activities are required for enamel knot formation.

Integration of Bmp and Wnt signaling during the bud-to-cap transition is mediated in part by Lef1, a transcription factor that interacts with β-catenin to regulate expression of Wnt target genes 46. Lef1 is expressed in both the dental epithelium and mesenchyme at the bud stage, with the epithelial expression restricted to the primary enamel knot by the cap stage 20, 47. Both Bmp4 and Wnt10b are able to induce Lef1 mRNA expression in E10.5 mouse embryonic mandibular explants 20, 26. Lef1 function is required for Fgf4 expression in the primary enamel knot and exogenous Fgf4 is able to rescue Lef1−/− mutant tooth germs from a bud stage developmental arrest 47,48. Thus, the Bmp, Fgf, and Wnt signaling pathways are all required for tooth development through the bud-to-cap transition. Further growth and morphogenesis of the tooth germ through the cap and bell stages largely depend on Fgf signaling, with the different Fgf family members acting partially redundantly 11, 49. Shh signaling also plays a critical role in proliferation of both the dental epithelium and mesenchyme 50, 51.

Taken together, the reiterative use of the Bmp, Fgf, Shh, and Wnt signaling pathways during tooth development, combined with a large number of mutant mouse strains for their detailed analysis in tooth initiation and morphogenesis, makes mouse tooth development an excellent model for further studies of the molecular mechanisms integrating these and other signaling networks in mammalian organogenesis.

3. An integrated network of activators and inhibitors of the Bmp, Fgf, Wnt, and Shh pathways regulates tooth number and pattern along the tooth row

Mammals have a single row of teeth along the oral margin of the upper and lower jaws. The ancestral tooth formula of placental mammals consists of three incisors, one canine, four premolars, and three molars in each half of the jaw 52. In comparison, humans have a reduced number of teeth but still a full complement of tooth types, whereas mice have only one incisor and three molars, separated by a toothless diastema, in each jaw quadrant. The lack of teeth in the mouse diastema region is not due to lack of tooth initiation during embryogenesis, however. Careful 3D reconstruction analyses of histological sections and molecular marker studies showed that at least two rudimentary buds, which exhibit transient Shh expression, form in the diastema region prior to first molar morphogenesis in each quadrant of the embryonic mouse jaws 52–55. In the maxilla, both diastemal tooth buds, called R1 and R2, regress by apoptosis. In the mandible, whereas the anterior bud regresses, the posterior bud, also called R2, is only transiently affected by apoptosis and subsequently incorporated into the anterior part of the first molar 52–56. These transient tooth buds anterior to the first molar tooth germs have been interpreted as evolutionary remnants of premolars that were lost during rodent evolution 52–57. Remarkably, premolar-like supernumerary teeth anterior to the first molars have been reported in mice carrying distinct mutations that affect each of the Bmp, Fgf, Shh, and Wnt signaling pathways56–61, which provide new insights into the complex cross-regulation and integration of these pathways in the regulation of tooth morphogenesis and patterning.

3.1. Regulation of tooth number in mice by the Sprouty family of antagonists of Fgf signaling

The sprouty (spry) gene was first identified in Drosophila for its role in negatively regulating Fgf induction of tracheal branching 62. Fgf signaling induces spry expression, but the Spry protein acts in a competitive fashion to block Fgf signaling62. Of four spry homologs in mice, three are expressed during tooth development, with Spry2 abundantly expressed in the tooth bud epithelium, Spry4 in the tooth mesenchyme whereas Spry1 is expressed in both tooth epithelium and mesenchyme 57. Most Spry2-null mice exhibit a supernumerary tooth anterior to the first molar in each half of the mandible. Histological and 3D reconstruction analyses of the developing tooth germs suggest that the supernumerary teeth result from revitalization of the diastemal R2 buds 56,57. Whereas the wildtype mouse mandibular R2 buds never express Fgf4 and only transiently express Shh, the Spry2-null mouse embryos show robust expression of both Fgf4 and Shh mRNAs in each mandibular R2 bud. Heterozygosity of either Fgf3 or Fgf10 suppressed the supernumerary tooth phenotype in Spry2-null mice, indicating that the revitalization of the diastemal tooth germs is due to increased Fgf signaling 57. Whereas explant culture assays showed that Fgf3 and Fgf10 could induce Shh expression in the dental epithelium 48, 57, however, the mechanisms underlying the induction of Fgf4 expression and of enamel knot function in the Spry2-null diastemal tooth buds have not been resolved.

Some Spry4-null mice also develop supernumerary diastemal teeth in the mandible, which appeared to correlate with ectopic activation of Fgf3 expression in the R2 bud mesenchyme 57. In addition, although the Spry1−/− mice do not have supernumerary teeth, the frequency of supernumerary tooth formation in Spry4−/− mutant mice is increased 3-fold by Spry1 heterozygosity 57. Dose-dependent genetic interactions between Spry2 and Spry4 as well as between Spry1 and Spry4 have also been shown to regulate the number of incisors, with Spry2+/− Spry4−/− mice having duplicated upper incisors and Spry2−/−Spry4−/− mutant mice showing duplicated upper and lower incisors63. Thus, the Spry family proteins play critical roles in antagonizing the reciprocal Fgf signaling between the developing tooth epithelium and mesenchyme to regulate the number of teeth in the mammalian dentition.

3.2. Supernumerary tooth formation resulting from increased Shh signaling in the mouse embryonic diastema mesenchyme

Mice homozygous for a transgenic insertion Tg737orpk, which causes partial loss of function of the Ift88 gene encoding the intraflagellar transport (IFT) protein Polaris, exhibit a supernumerary tooth in the diastema in all four quadrants 59, 64. IFT proteins are essential for the formation of cilia, hair-like appendages on the cell surface. Most mammalian cells have a single primary cilium, which plays essential roles in processing the Gli2 and Gli3 transcription factors, effectors of the Hedgehog signaling pathway 65. In the Tg737orpk mutant embryos, expression of both Ptc1 and Gli1, transcriptional target genes of Hedgehog signaling, was apparently increased in the diastemal tooth mesenchyme, suggesting that increased Shh signaling underlies the revitalization of the diastemal teeth in these mutant mice 59. Whereas Shh signaling plays critical roles in regulating proliferation and differentiation of the developing dental epithelium 50, 66, tissue-specific inactivation studies showed that the formation of diastemal teeth occurred in mice lacking Polaris function in the neural crest derived dental mesenchyme but not in those lacking Polaris in the oral epithelium 59. Since Shh is the only Hedgehog signal expressed in the developing tooth germs, these results suggest that a mesenchymal factor(s) downstream of increased Shh signaling is responsible for stimulating the continued development of the diastemal tooth buds in the Polaris-deficient mouse embryos. Mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of growth arrest specific-1 (Gas1), which encodes an inhibitor of Shh signaling and is expressed in the diastema mesenchyme 67, 68, also exhibit supernumerary diastemal teeth in all four quadrants 59, further supporting the hypothesis that increased Shh signaling activates a mesenchymal factor(s) which in turn induces/maintains a functional primary enamel knot in the diastemal tooth buds to stimulate continued tooth morphogenesis. The responsible mesenchymal factor(s) has not been identified, however.

3.3. Sostdc1 and Lrp4 function as a ligand-receptor pair to regulate tooth number and tooth shape via suppression of canonical Wnt signaling

Whereas a positive feedback circuit between Wnt and Bmp4 signaling appears to be the major mediator of the reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during early molar tooth development 39, Bmp signaling also induces expression of Sostdc1 (also known as ectodin, Wise, and USAG1), a secreted protein that can antagonize both Bmp and canonical Wnt signaling 69–71. During early tooth development, Sostdc1 is expressed in the epithelium and mesenchyme surrounding the developing tooth bud but its expression is excluded from the enamel knot and adjacent epithelial and mesenchymal cells 58, 60, 70. Targeted disruption of Sostdc1 in mice resulted in multiple tooth developmental defects including molar fusions, supernumerary incisors, and a supernumerary tooth anterior to the first molar in each quadrant 60, 61,72, 73. The Sostdc1−/− mutant tooth germs show increased canonical Wnt signaling, as demonstrated by using the Top-Gal transgenic reporter 61. Reduction in gene dosage of Lrp5 (low density lipoprotein receptor related protein 5) and Lrp6, which encode co-receptors for canonical Wnt signaling, showed dose-dependent rescue of the tooth anomalies whereas heterozygosity of Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Fgf10, or Bmpr1a did not affect diastemal tooth development in the Sostdc1−/− mutant mice 61, suggesting that supernumerary tooth formation in these mutant mice primarily resulted from increased canonical Wnt signaling.

Remarkably, mice homozygous for a hypomorphic mutation in the Lrp4 gene exhibit tooth phenotypes almost identical to the Sostdc1−/− mice 58. Lrp4 shares extensive structural similarity in its extracellular domain with those of Lrp5 and Lrp6 74,75. Although Sostdc1 has been shown to physically interact with both Lrp6 and Lrp4 in vitro 58, 68, 71, recent genetic analysis showed that Lrp4 is required for Sostdc1 to exert its function in regulating epidermal appendage development in vivo 76, suggesting that Sostdc1 and Lrp4 act as a ligand-receptor pair to antagonize Lrp5/6-mediated canonical Wnt signaling 58, 76.

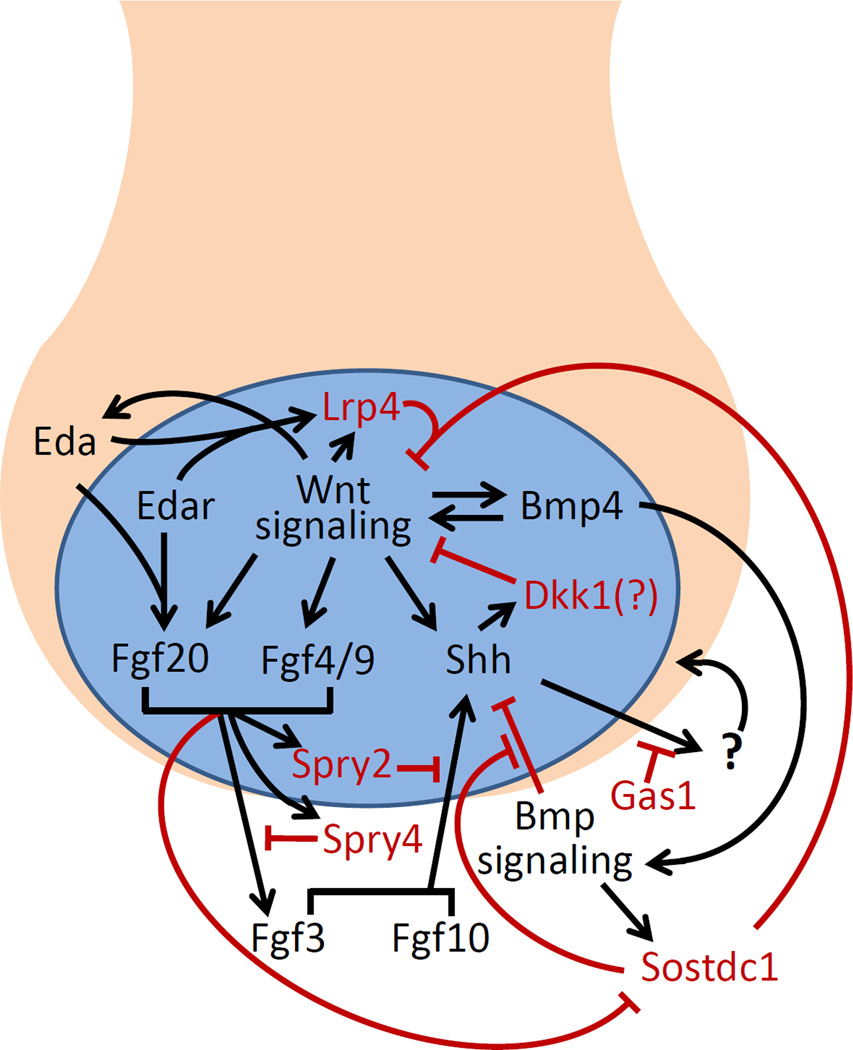

Paradoxically, whereas Shh mRNA expression and Shh signaling activity are significantly increased in the R2 tooth germs in the Sostdc1−/− mouse embryos 61, Shh+/−Sostdc1+/− double heterozygous mice exhibited high penetrance of diastemal teeth while no tooth defects were detected in either Shh+/− or Sostdc1+/− mice 61. Reducing the gene dosage of either Ptch1 or Lrp6 by 50% significantly reduced the frequency of the supernumerary tooth phenotype in Shh+/− Sostdc1+/− mice 61, suggesting that Shh and Sostdc1 act synergistically to antagonize canonical Wnt signaling in the diastemal tooth buds. Furthermore, tissue-specific deletion of Shh in the oral epithelium caused significantly increased and expanded the domain of Top-Gal reporter expression in the diastemal tooth buds, indicating that Shh inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Ahn et al. further showed that Dkk1 mRNA expression was significantly reduced in the E13.5 Shh+/− Sostdc1+/− tooth germs in comparison with the Sostdc1+/− tooth germs 61. These data uncover a Wnt-Shh negative feedback loop as part of the tooth developmental regulatory network 61 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Bmp, Fgf, Shh, Wnt, and Eda signaling pathways form an integrated network of positive and negative feedback loops to regulate early tooth development through the bud-to-cap transition. The tooth bud epithelium is represented in light cinnamon color whereas the primary enamel knot (not drawn to scale) is represented in blue color. The mesenchyme surround the tooth bud is not colored. Black arrows indicate positive input and red indicates repressive input. A question mark is placed next to Dkk1 because it has not been experimentally confirmed as the mediator of repression of Wnt signaling by Shh. The mesenchymal signal downstream of Shh is represented with a question mark because it has not been identified and it is not clear how increased Shh signaling in the tooth mesenchyme stimulates primary enamel knot function.

Consistent with the previous finding that Fgf4 acts downstream of Lef1-mediated canonical Wnt signaling at the bud-to-cap transition 48, expression of several Fgf ligands, including Fgf3 and Fgf4, is significantly increased in the E13.5 Sostdc1−/− tooth germs 61. Thus, in Sostdc1−/− as well as Lrp4-deficient mice, increased canonical Wnt signaling activates the expression of multiple Fgf ligands in the tooth bud epithelium and the increased Fgf signaling overcomes Spry2/4 inhibition to stimulate continued development of the R2 tooth buds 61 (Figure 2).

Whereas the increased Wnt signaling resulted in significantly increased Shh mRNA expression in the R2 tooth buds at E13.5, Shh mRNA expression was significantly reduced in the first molar tooth germs at E14.5 in Sostdc1−/− mouse embryos in comparison with control littermates 58, 61. Similarly, Shh mRNA expression was significantly reduced in the first molar tooth germs in Lrp4-deficient mouse embryos at E14.5 58. Tissue-specific inactivation of either Shh or Smo in the oral epithelium caused molar tooth fusions similar to that in Sostdc1−/− and Lrp4-deficient mice 50, 58, 61, 66. Molar fusion was also induced in the mouse pups by injecting pregnant mice with the Shh function-blocking antibody 5E1 between E10 and E16 77. These results suggest that the molar fusion phenotype in all of these mutant or experimentally treated mice is due to reduced Shh signaling.

Why is Shh expression significantly increased in the diastemal tooth buds but significantly reduced in the molar tooth germs in the Sostdc1−/− and Lrp4-deficient mouse embryos? The answer may lie in the finding that Sostdc1 is an antagonist of both Wnt and Bmp signaling 69–71. Both Sostdc1−/− and Lrp4-deficient tooth germs showed increased Bmp signaling activity, as demonstrated by increased accumulation of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 58, 73. In addition, Sostdc1−/− mutant molar tooth germs showed markedly increased sensitivity to Bmp4 in explant culture 60. It was shown previously that transgenic overexpression of Bmp4 in the tooth mesenchyme suppressed Shh expression in the tooth epithelium 78. Thus, increased Bmp signaling activity might have contributed to the molar fusion phenotype of the Sostdc1−/− or Lrp4-deficient mice by suppressing Shh expression in the molar tooth epithelium. However, Ahn et al.61 showed that deleting both copies of Lrp5 and one copy of Lrp6 suppressed both the supernumerary teeth and molar fusion phenotypes in Sostdc1−/− mice. It is not known whether the rescuing effects of loss of Lrp5 and Lrp6 on the Sostdc1−/− mutant tooth germs occurred upstream or downstream of Shh signaling. Canonical Wnt signaling is also required for Bmp4 expression in the developing tooth germs 79. Thus, the genetic rescue of Sostdc1−/− tooth phenotypes by inactivation of Lrp5 and Lrp6 does not exclude the possibility that Sostdc1-mediated inhibition of Bmp signaling may play a primary role in preventing molar tooth fusion. Further investigation is needed to clarify the detailed biochemical mechanisms involving Sostdc1 and Lrp4 in tooth development and patterning.

3.4. The ectodysplasin (Eda) signaling pathway regulates tooth number, size, and shape through Fgf20

The EDA gene was first identified by positional cloning of the gene responsible for X-linked hipohidrotic/anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED) in humans, characterized by missing or abnormally shaped teeth, sparse hair, and impaired exocrine glands 80–82. A classical spontaneous mouse mutation, Tabby, causes similar ectodermal developmental defects, including missing teeth, smaller teeth, and reduced molar cusps, and was shown to be due to a mutation in the mouse Eda gene 83–85. Eda is a signal of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily 82. During early tooth development, expression of Eda and its receptor Edar are both restricted to the epithelium, with Eda mRNAs broadly expressed in the oral and tooth bud epithelium while Edar mRNAs restricted to the epithelial signaling centers, the placodes and enamel knots 86. Eda mRNA expression in the early tooth epithelium depends on Lef1 function and is induced by exogenous Wnt6 86, indicating that Eda acts downstream of Wnt signaling during early tooth development. Interestingly, overexpression of either Eda or an active form of Edar in the oral epithelium resulted in development of supernumerary teeth anterior to the first molars, most likely due to revitalization of the R2 diastemal tooth germs 49, 87, 88. Recently, Häärä et al. 49 identified Fgf20 as a downstream target gene of Eda signaling in the developing tooth epithelium. Mice lacking Fgf20 exhibit tooth phenotypes similar to the Tabby mice. Paradoxically, reduction in Fgf20 gene dosage increased the frequency of supernumerary teeth in the K14-Eda transgenic mice: while 50% of K14-Eda mice had supernumerary teeth, 76% of K14-Eda;Fgf20+/− and 88% of K14-Eda;Fgf20−/− mutant mice had supernumerary teeth. Häärä et al.49 further showed that Fgf20 was able to induce Spry2 and Spry4 expression in the tooth epithelium and mesenchyme, respectively, and that decreased levels of expression of these Fgf signaling antagonists likely underlie the increased frequency of supernumerary tooth development in the compound transgenic mice. Additional studies have shown that Eda signaling also regulates expression of Shh, Dkk4, follistatin, and Lrp4 in epidermal placode development 89, 90, suggesting that Eda signaling may modulate multiple components of the integrated signaling network that regulates the balance of activators and inhibitors of tooth morphogenesis and patterning (Figure 2).

4. The Bmp4-Msx1 positive feedback loop propagates mesenchymal odontogenic potential for sequential tooth formation

Mammalian molars form sequentially in an anterior-to-posterior direction but the molecular mechanisms regulating sequential tooth formation are not well understood. Kavanagh et al. 91 showed that mouse mandibular first molar tooth germ inhibited second molar development and proposed an inhibitory cascade model, in which initiation of posterior molars depends on a balance between intermolar inhibition and mesenchymal activation, to account for sequential molar initiation in mammals. The candidate mesenchymal activators include Inhibin-βA and Bmp4 whereas Sostdc1 is an excellent candidate intermolar inhibitor 91.

During mouse tooth development, Bmp4 is first expressed in the tooth epithelium at about E11 and its expression shifts to the dental mesenchyme by E12, coincident with the transfer of the tooth inductive potential from the epithelium to mesenchyme 6, 17. Exogenous Bmp4 protein induced Msx1 and Bmp4 gene expression in cultured mandibular mesenchyme explants 17, 18. Msx1 gene knockout mouse embryos exhibit developmental arrest of all tooth germs at the bud stage, with significantly reduced Bmp4 mRNA expression in the dental mesenchyme 24, 26. Remarkably, exogenous Bmp4 protein partly rescued morphogenesis of the Msx1−/− mutant mandibular molar tooth germs in explant culture 26, 43, suggesting that Bmp4 and Msx1 function in a positive feedback loop to regulate early tooth morphogenesis. Maas and Bei 92 proposed that the Bmp4-Msx1 positive feedback loop functions as a molecular amplifier to rapidly propagate the Bmp4 signal throughout the developing tooth mesenchyme during the transfer of the odontogenic potential from the epithelium to mesenchyme. In contrast to Msx1−/− mutant mice, however, the Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mice, which lack functional Bmp4 mRNA expression in the tooth mesenchyme, showed only developmental arrest of the mandibular molar but the mutant maxillary first and second molars as well as all incisors continued to develop to mineralized teeth 93 (Figure 3A, B, F, G). The mandibular molar developmental arrest in the Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre embryos correlated with a more significant decrease in Msx1 mRNA expression in the mandibular molar mesenchyme than in the maxillary molar mesenchyme 93, confirming a critical role for mesenchymal Bmp4 in the maintenance of Msx1 expression and suggesting that other Msx1-dependent mesenchymal odontogenic factors can partially complement for loss of Bmp4 in driving tooth morphogenesis through the bud-to-cap transition. Reducing Msx1 gene dosage by 50% in the Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mice enhanced the maxillary molar developmental defects such that the first molar tooth germ was significantly retarded and the second molar failed to develop (Figure 3C). These results indicate that the Bmp4-Msx1 positive feedback loop plays a critical role in propagating the mesenchymal odontogenic signals to drive sequential tooth formation.

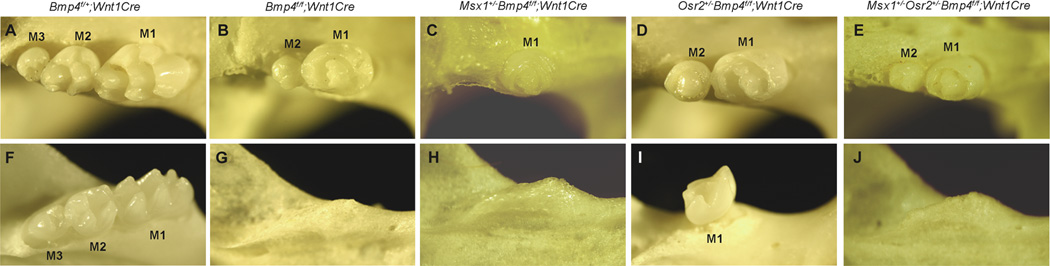

Figure 3.

Genetic interactions between Bmp4, Msx1, and Osr2 regulate sequential molar development in mice. (A–J) Skeleton preparations showing the maxillary (A–E) and mandibular molar (F–J) regions of Bmp4f/+;Wnt1Cre (A, F), Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre (B, G), Msx1+/− Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre (C, H), Osr2+/−Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre (D, I) and Msx1+/−OSR2+/−Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre (E, J) mice at 21 days after birth. M1, M2, and M3 indicate first, second, and third molars, respectively.

Cho et al.77 recently showed that development of the second molar was accelerated in mouse embryos by the Shh function-blocking antibody 5E1 and proposed a Wnt-Shh-Sostdc1 negative feedback loop, in which Wnt signaling induces Shh and Shh suppresses Wnt/β-catenin pathway indirectly via Sostdc1, as a candidate mechanism for spatial tooth patterning. Although mathematical simulation of this model could generate the molar tooth patterns of wildtype and several mutant mouse conditions 77, experimental evidence points to inability of Shh in inducing Sostdc1 expression in the intact tooth germ 70, 77. Laurikkala et al.70 showed that Shh antagonized Bmp induction of Sostdc1 expression. Although exogenous Shh protein could bring about weak Sostdc1 mRNA expression in isolated tooth mesenchyme 77, Bmp ligands induced much more robust Sostdc1 expression in whole tooth germ explants 70. Moreover, reducing Shh gene dosage further enhanced the molar fusion phenotype in Sostdc1−/− mice 61, indicating that Shh acts downstream of Sostdc1 in preventing molar tooth fusion. Ahn et al. 61 suggest that Shh antagonizes Wnt signaling through upregulation of Dkk1.

Taken together, the mechanism underlying sequential formation and spatial patterning of teeth involves integration of the Bmp4-Msx1 positive feedback loop for propagation of mesenchymal odontogenic activators, the Bmp-Wnt inter-tissue feedback circuit driving tooth morphogenesis, Bmp induction of the Sostdc1 inhibitor, and the feedback repression of Wnt signaling by Shh.

5. Osr2 patterns mammalian molar teeth into a single row by antagonizing Msx1-mediated expansion of the mesenchymal odontogenic field

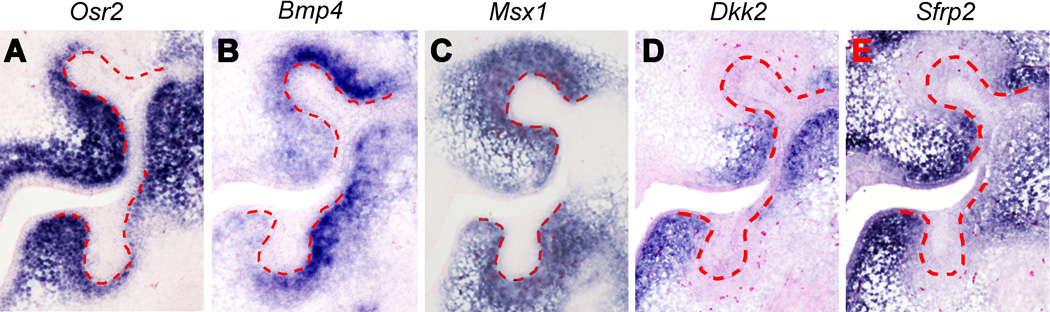

Mammals have teeth in a single row whereas many vertebrates have multirowed dentitions. The Osr2−/− mutant mice were found to develop supernumerary molar teeth from oral epithelium lingual to the normal tooth row 94. Osr2 is expressed in a lingual-to-buccal gradient in the developing tooth mesenchyme surrounding the early molar tooth buds, with higher levels on the lingual side (Figure 4A). Tissue recombination assays demonstrate that the mesenchymal odontogenic potential is expanded to the mandibular mesenchyme lingual to the molar tooth germs in the Osr2−/− mutant embryos 94. Remarkably, Bmp4 mRNA expression exhibits a complementary pattern to that of Osr2 along the buccolingual axis of the developing molar tooth mesenchyme in widltype mouse embryos even though Msx1 is expressed throughout the tooth mesenchyme (Figure 4B, C). Bmp4 expression is significantly increased and expanded into the lingual side of the developing tooth mesenchyme in the Osr2−/− mutant embryos 94. Moreover, whereas Msx1−/− mutant embryos exhibit tooth bud developmental arrest accompanied by significantly reduced Bmp4 expression in the tooth mesenchyme, Msx1−/−Osr2−/− compound mutant embryos show partial restoration of Bmp4 expression and their first molar tooth germs continue to develop beyond the bud stage 94. Together with biochemical studies showing physical interaction between Msx1 and Osr2 proteins 95, these data suggest that Osr2 patterns the buccolingual axis of the developing tooth mesenchyme by antagonizing Msx1-mediated activation of mesenchymal odontogenic signals, including Bmp4 expression, in the developing tooth mesenchyme to restrict mammalian molar tooth development in a single row (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Differential gene expression along the buccolingual axis of the developing mouse tooth bud mesenchyme at E13.5. (A – E) Spatial patterns of Osr2 (A), Bmp4 (B), Msx1 (C), Dkk2 (D), and Sfrp2 (E) mRNAs are detected by in situ hybridization of coronal sections E13.5 mouse first molar tooth germs. The mRNA signals are shown in blue color. Lingual side is to the left for all panels. Red dashed lines mark the epithelial boundary between the tooth bud epithelium and mesenchyme. Each panel shows both the maxillary (top) and mandibular (bottom) first molar tooth germs.

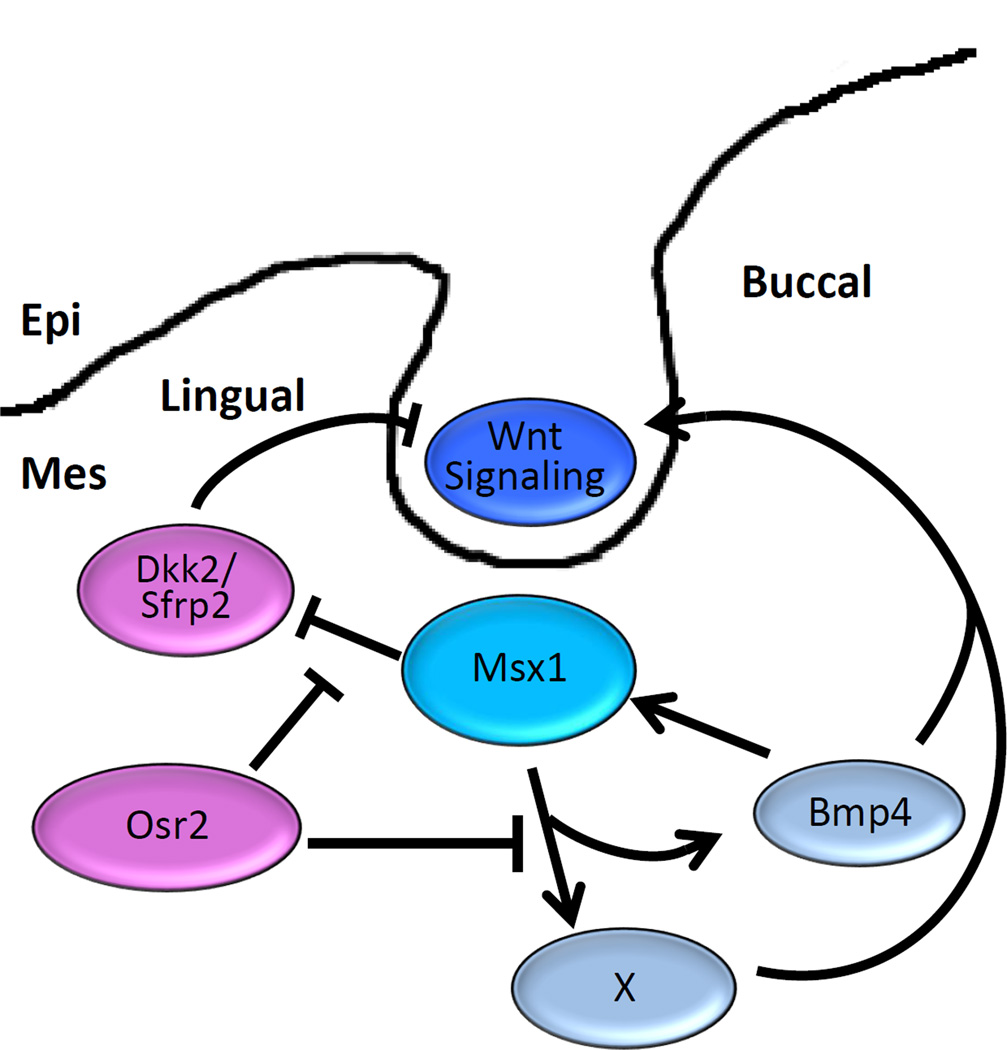

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram depicting antagonistic interactions between Msx1 and Osr2 in patterning the molar tooth developmental field. Msx1 and Bmp4 act in a positive feedback loop in the tooth mesenchyme. Osr2 restricts Msx1-mediated activation of Bmp4 and other mesenchymal odontogenic signals (represented by X) to the buccal side of the tooth mesenchyme. Expression of Dkk2 and Sfrp2 are negatively regulated by Msx1 and restricted to the lingual side, possibly resulting from Osr2-mediated repression of Msx1 function. Epi, epithelium; Mes, mesenchyme.

Whereas the Msx1−/−Osr2−/− compound mutant mice showed nearly normal morphogenesis of the first molars, they failed to develop either the supernumerary teeth or the second and third molars, in contrast to the Osr2−/− single mutants 94, suggesting that, in addition to patterning the buccolingual axis of the developing tooth mesenchyme, Osr2 interaction with Msx1 also regulates sequential tooth formation along the tooth row. This is confirmed by further analysis in the Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mice. Whereas the Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mice exhibit mandibular molar developmental arrest at the bud stage, reducing Osr2 gene dosage by 50% rescued mandibular first molar tooth germs to small mineralized teeth in the Osr2+/−Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mice 93 (Figure 3H, I). Moreover, whereas the maxillary second molars failed to develop in the Msx1+/− Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mice, they were rescued in the Osr2+/−Msx1+/−Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mice (Figure 3E). Together, these data indicate that Osr2 patterns the mesenchymal odontogenic field along both the buccolingual and anteroposterior axes by restricting the domain of Msx1-mediated propagation of mesenchymal odontogenic potential (Figure 5).

Another important finding by Jia et al.93 is that the mandibular molar mesenchyme expresses significantly higher levels of Wnt antagonists, including Dkk2 and Wif1, than the maxillary molar mesenchyme during normal tooth development. Previous studies of the Dlx1−/−Dlx2−/− and Inhba−/− mutant mice30, 96, showing maxillary-only and mandibular-only molar developmental arrest, respectively, suggested that maxillary and mandibular molar development involved distinct genetic pathways 96, 97. The findings of Jia et al. 93 suggest that normal mandibular molar morphogenesis through the bud-to-cap transition requires higher levels of mesenchymal activators than the maxillary molar tooth germs to counteract the higher levels of Wnt antagonists. Expression of Dkk2 and Wif1 mRNAs were significantly increased in the Bmp4f/f;Wnt1Cre mutant tooth mesenchyme 93, suggesting that Bmp4 signaling might crossregulate Wnt signaling activity by regulating expression of the Wnt antagonists in the developing tooth mesenchyme. Remarkably, Dkk2 mRNA expression in the developing molar tooth mesenchyme exhibits a strong lingual bias 98 (Figure 4D). Another Wnt antagonist Sfrp2 also exhibits preferential expression on the lingual side of the developing molar tooth mesenchyme (Figure 4E). Recently, we carried out real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of microdissected E13.5 Msx1−/− and control tooth bud mesenchyme and found that expression of both Dkk2 and Sfrp2 is significantly upregulated in the Msx1−/− molar mesenchyme. Thus, the antagonistic actions of Osr2 and Msx1 might pattern the buccolingual axis of the molar tooth developmental field through modulation of both Bmp4 and Wnt signaling (Figure 5).

6. Concluding remarks

Research in the past twenty years has revealed that development of both the individual teeth and the whole dentition is controlled by coordinated actions of only a few conserved intercellular signaling pathways. Whereas each of the Bmp, Fgf, Shh, and Wnt signaling pathways is repeatedly used throughout tooth organogenesis and regulated by a number of activators and inhibitors, the revitalization of the same physiologically arrested diastemal tooth germs in mice due to mutations affecting distinct pathways demonstrate that these signaling pathways act in highly integrated networks regulating tooth development (Figure 2). These data suggest that tinkering with the activity of one pathway has the potential to overcome activator insufficiency in another to rescue morphogenesis of arrested tooth germs. This is further supported by the findings that constitutive activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in the dental epithelium is able to induce supernumerary tooth development even in mice lacking Msx1 or Pax9 39, 45. Although much of the molecular mechanisms mediating the coordination and integration of the signaling pathways and gene regulatory networks in tooth organogenesis remains to be elucidated, these findings have great implications for development of therapeutic strategies for tooth developmental abnormalities, particularly for congenitally missing or hypoplastic teeth.

Approximately 20% of people do not develop all third molars and 5% lack some of the other permanent teeth, with agenesis of six or more permanent teeth (apart from the third molars) occurring in about 1 in 1000 99. Mutations in MSX1, PAX9, AXIN2, EDA, and WNT10A, have been detected in a large number of nonsyndromic tooth agenesis patients 99–101. Most patients with tooth agenesis exhibit relatively normal primary tooth development and missing only some, but not all, of the permanent teeth, indicating that the phenotype is caused by perturbation of the activator-inhibitor balance, such as reduced Wnt signaling activity, rather than complete disruption of the tooth developmental gene regulatory network. The revitalization of the physiologically arrested diastemal tooth germs in mice by increased activity in Eda, Fgf, or Wnt signaling, suggests that it is possible to rescue the missing permanent teeth if specific and safe pharmacological agonists of these pathways can be developed and administered at the appropriate developmental stage. Following an experimental study that demonstrated effective correction of tooth and other ectodermal defects in Tabby mice with recombinant EDA protein 102, short postnatal treatment of XLHED dogs with recombinant EDA protein showed remarkable rescue of development of permanent teeth as well as other affected ectodermal organs 103, 104. These data provide proof of concept for development of a pharmacological cure of congenital tooth defects.

Because humans and most other mammals replace their teeth only once, tooth loss due to decay or accident is a major health problem. Development of strategies for biological replacement of lost teeth requires better understanding of the detailed molecular mechanisms controlling tooth induction and morphogenesis. Classic tissue recombination experiments demonstrated that, while tooth initiation signals first arise in the presumptive dental epithelium, the odontogenic potential shifts into the tooth mesenchyme at the early bud stage such that mouse molar mesenchyme from E12 through E16 could induce complete tooth formation when recombined with embryonic non-dental epithelium 6, 105–110. More recently, it was reported that the E13 mouse molar tooth mesenchyme instructed tooth formation when recombined with cultured human primary keratinocytes, with the human cells differentiating into enamel-secreting ameloblasts and mouse tooth mesenchyme to dentin-secreting odontoblasts 111. Thus, understanding the genetic program controlling the mesenchymal odontogenic potential will facilitate development of strategies for tooth bioengineering. The findings that the Bmp4-Msx1 pathway drives expansion of, whereas the Osr2 transcription factor suppresses, the inductive potential of the dental mesenchyme 93, 94 provide an excellent opening to uncovering the molecular network regulating mesenchymal odontogenic potential.

Highlights.

Integrated networks of Bmp, Fgf, Shh, and Wnt pathways regulate tooth organogenesis.

Increased activity of Fgf, Shh, or Wnt signaling revitalizes mouse vestigial teeth.

Bmp4-Msx1 positive feedback loop drives expansion of tooth developmental field.

Osr2 patterns odontogenic mesenchyme along buccolingual and anteroposterior axes.

The Wnt-Shh and Bmp-Sostdc1 negative feedback loops regulate spatial tooth

Acknowledgements

We thank Zunyi Zhang for preparation of Figure 1. We thank Hyuk-Jae Kwon for critical reading of the manuscript and discussions. Primary research data presented in this paper were achieved through support by National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research (NIDCR) grants DE013681 and DE018401 to RJ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pires-DaSilva A, Sommer RJ. The evolution of signaling pathways in animal development. Nat Genet. 2003;4:39–49. doi: 10.1038/nrg977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pispa J, Thesleff I. Mechanisms of ectodermal organogenesis. Dev Biol. 2003;262:195–205. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thesleff I, Sharpe P. Signalling networks regulating dental development. Mech Dev. 1997;67:111–123. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jernvall J, Thesleff I. Reiterative signaling and patterning during mammalian tooth morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2000;92:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tucker AS, Sharpe PT. The cutting-edge of mammalian development, how the embryo makes teeth. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:499–508. doi: 10.1038/nrg1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumsden AG. Spatial organization of the epithelium and the role of neural crest cells in the initiation of the mammalian tooth germ. Development. 1988;103:155–169. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Y, Zhang Z, Yu X, Yan M, Zhang X, Gu S, Stuart T, Liu C, Reiser J, Zhang Y, Chen YP. Application of lentivirus-mediated RNAi in studying gene function in mammalian tooth development. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1334–1344. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser GJ, Bloomquist RF, Streelman JT. Common developmental pathways link tooth shape to regeneration. Dev Biol. 2013;377:399–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jernvall J, Thesleff I. Tooth shape formation and tooth renewal: evolving with the same signals. Development. 2012;139:3487–3497. doi: 10.1242/dev.085084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bei M. Molecular genetics of tooth development. Curr Opin Gen & Dev. 2009;19:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tummers M, Thesleff I. The importance of signaling pathway modulation in all aspects of tooth development. J. Exp. Zoolog. 2009;312B:309–319. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jussila M, Thesleff I. Signaling networks regulating tooth organogenesis and regeneration, and the specification of dental mesenchymal and epithelial cell lineages. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobourne MT, Sharpe PT. Making up the numbers: The molecular control of mammalian dental formula. Semin Cell Dev biol. 2010;21:314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thesleff I, Hurmerinta K. Tissue interactions in tooth development. Differentiation. 1981;18:75–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1981.tb01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wozney JM, Rosen V, Celeste AJ, Mitsock LM, Whitters MJ, Kriz RW, Hewick RM, Wang EA. Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science. 1988;242:1528–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.3201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons KM, Pelton RW, Hogan BL. Patterns of expression of murine Vgr-1 and BMP-2a RNA suggest that transforming growth factor-beta-like genes coordinately regulate aspects of embryonic development. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1657–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vainio S, Karavanova I, Jowett A, Thesleff I. Identification of BMP-4 as a signal mediating secondary induction between epithelial and mesenchymal tissues during early tooth development. Cell. 1993;75:45–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tureckova J, Sahlberg C, Åberg T, Ruch JV, Thesleff I, Peterkova R. Comparison of expression of the msx-1, msx-2, BMP-2 and BMP-4 genes in the mouse upper diastemal and molar tooth primordia. Int J Dev Biol. 1995;39:459–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neubuser A, Peters H, Balling R, Martin GR. Antagonistic interactions between FGF and BMP signalling pathways: a mechanism for positioning the sites of tooth formation. Cell. 1997;90:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dassule HR, McMahon AP. Analysis of epithelial mesenchymal interactions in the initial morphogenesis of the mammailan tooth. Dev Biol. 1998;202:215–227. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarkar L, Sharpe PT. Expression of Wnt signalling pathways genes during tooth development. Mech Dev. 1999;85:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker AS, Matthews KL, Sharpe PT. Transformation of tooth type induced by inhibition of BMP signaling. Science. 1998;282:1136–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandler M, Neubuser A. FGF signaling is necessary for the specification of the odontogenic mesenchyme. Dev Biol. 2001;240:548–559. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satokata I, Maas R. Msx-1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nat Genet. 1994;6:348–356. doi: 10.1038/ng0494-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters H, Neubuser A, Kratochwil K, Balling R. Pax9-deficient mice lack pharyngeal pouch derivatives and teeth and exhibit craniofacial and limb abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2735–2747. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.17.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Bei M, Woo I, Satokata I, Maas R. Msx1 controls inductive signaling in mammalian tooth morphogenesis. Development. 1996;122:3035–3044. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bei M, Maas R. FGFs and BMP4 induce both Msx1-independent and Msx1-dependent signaling pathways in early tooth development. Development. 1998;125:4325–4333. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansour SL. Targeted disruption of int-2 (fgf-3) causes developmental defects in the tail and inner ear. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;39:62–68. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080390111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang XP, Suomalainen M, Felszeghy S, Zelarayan LC, Alonso MT, Plikus MV, Maas RL, Chuong CM, Schimmang T, Thesleff I. An integrated gene regulatory network controls stem cell proliferation in teeth. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson CA, Tucker AS, Christensen L, Lau AL, Matzuk MM, Sharpe PT. Activin is an essential early mesenchymal signal in tooth development that is required for patterning of the murine dentition. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2636–2649. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matzuk MM, Kumar TR, Vassalli A, Bickenbach JR, Roop DR, Jaenisch R, Bradley A. Functional analysis of activins during mammalian development. Nature. 1995;374:354–356. doi: 10.1038/374354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andl T, Ahn K, Kairo A, Chu EY, Wine-Lee L, Reddy ST, Croft NJ, Cebra-Thomas JA, Metzger D, Chambon P, et al. Epithelial Bmpr1a regulates differentiation and proliferation in postnatal hair follicles and is essential for tooth development. Development. 2004;131:2257–2268. doi: 10.1242/dev.01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu W, Sun X, Braut A, Mishina Y, Behringer RR, Mina M, Martin JF. Distinct functions for Bmp signaling in lip and palate fusion in mice. Development. 2005;132:1453–1461. doi: 10.1242/dev.01676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Lin M, Wang Y, Cserjesi P, Chen Z, Chen Y. BmprIa is required in mesenchymal tissue and has limited redundant function with BmprIb in tooth and palate development. Dev Biol. 2011;349:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andl T, Ahn K, Kairo A, Chu EY, Wine-Lee L, Reddy ST, Croft NJ, Cebra-Thomas JA, Metzger D, Chambon P, Lyons KM, Mishina Y, Seykora JT, Crenshaw EB, III, Millar SE. Epithelial Bmpr1a regulates differentiation and proliferation in postnatal hair follicles and is essential for tooth development. Development. 2004;131:2257–2268. doi: 10.1242/dev.01125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Moerloose L, Spencer-Deneb, Revest J, Hajihosseini M, Rosewell I, Dickson C. An important role for the IIIb isoform of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) in mesenchymal-epithelial signalling during mouse organogenesis. Development. 2000;127:483–492. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F, Chu EY, Watt B, Zhang Y, Gallant NM, Andl T, Yang SH, Lu MM, Piccolo S, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Taketo MM, Morrisey EE, Atit R, Dlugosz AA, Millar SE. Wnt/betaPage catenin signaling directs multiple stages of tooth morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;313:210–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Lan Y, Baek JA, Gao Y, Jiang R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling plays an essential role in activation of odontogenic mesenchyme during early tooth development. Dev Biol. 2009;334:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Connell DJ, Ho JWK, Mammoto T, Turbo-Doan A, O’Connell JT, Haseley PS, Koo S, Kamiya N, Ingber DE, Park PJ, Mass RL. A Wnt-Bmp feedback circuit controls intertissue signaling dynamics in tooth organogenesis. Sci Signal. 2012;5:1–10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salazar-Ciudad I, Jernvall J. How different types of pattern formation mechanisms affect the evolution of form and development. Evol Dev. 2004;6:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142x.2004.04002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jernvall J, Aberg T, Kettunen P, Keranen S, Thesleff I. The life history of an embryonic signaling center: BMP-4 induces p21 and is associated with apoptosis in the mouse tooth enamal knot. Development. 1998;125:161–169. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kettunen P, Karavanova I, Thesleff I. Responsiveness of developing dental tissues to fibroblast growth factors: expression of splicing alternatives of FGFR1-2-3, and of FGFR4; and stimulation of cell proliferation by FGF-2, -4, -8, and -9. Dev Genet. 1998;22:374–385. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:4<374::AID-DVG7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bei M, Kratochwil K, Maas R. BMP4 rescues a non-cell-autonomous function of Msx1 in tooth development. Development. 2000;127:4711–4718. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.21.4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarvinen E, Salazar-Ciudad I, Birchmeier W, Taketo MM, Jernvall J, Thesleff I. Continuous tooth generation in mouse is induced by activated epithelial Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. PNAS. 2006;103:18627–18632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607289103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang XP, O’Connell DJ, Lund JJ, Saadi I, Kuraguchi M, Turbe-Doan A, Cavallesco R, Kim H, Park PJ, ZHarada H, Kucherlapati R, Mass RL. Apc inhibition of Wnt signaling regulates supernumerary tooth formation during embryogenesis and throughout adulthood. Development. 2009;136:1939–1949. doi: 10.1242/dev.033803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kratochwil K, Dull M, Farinas I, Galceran J, Grosschedl R. Lef1 expression is activated by BMP-4 and regulates inductive tissue interactions in tooth and hair development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1382–1394. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kratochwil K, Galceran J, Tontsch S, Roth W, Grosschedl R. FGF4, a direct target of LEF1 and Wnt signaling, can rescue the arrest of tooth organogenesis in Lef1−/− mice. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3173–3185. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Häärä O, Harjunmaa E, Lindfors PH, Huh SH, Fliniaux I, Åberg T, Jernvall J, Ornitz DM, Mikkola ML, Thesleff I. Ectodysplasin regulates activator-inhibitor balance in murine tooth development through Fgf20 signaling. Development. 2012;139:3189–3199. doi: 10.1242/dev.079558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gritli-Linde A, Bei M, Maas R, Zhang XM, Linde A, McMahon AP. Shh signaling within the dental epithelium is necessary for cell proliferation, growth and polarization. Development. 2002;129:5323–5337. doi: 10.1242/dev.00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeong J, Mao J, Tenzen T, Kottmann AH, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in the neural crest cells regulates the patterning and growth of facial primordia. Genes Dev. 2004;18:937–951. doi: 10.1101/gad.1190304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peterková R, Lesot H, Peterka M. Phylogenetic memory of developing mammalian dentition. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2006;306:234–235. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peterková R, Kristenová P, Lesot H, Lisi S, Vonesch JL, Gendrault JL, Peterka M. Different morphotypes of the tabby (EDA) dentition in the mouse mandible result from a defect in the mesio-distal segmentation of dental epithelium. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2002;5:215–226. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0544.2002.02226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viriot L, Peterkova R, Peterka M, Lesot H. Evolutionary implications of the occurrence of two vestigial tooth germs during early odontogenesis in the mouse lower jaw. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:129–133. doi: 10.1080/03008200290001168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prochazka J, Pantalacci S, Churava S, Rothova M, Lambert A, Lesot H, Klein O, Peterka M, Laudet V, Peterkova R. Patterning by heritage in mouse molar row development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:15497–15502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002784107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peterkova R, Churava S, Lesot H, Rothova M, Prochazka J, Peterka M, Klein OD. Revitalization of a diastemal tooth primordium in Spry2 null mice results from increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2009;312B:292–308. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klein OD, Minowada G, Peterkova R, Kangas A, Yu BD, Lesot H, Peterka M, Jernvall J, Martin GR. Sprouty genes control diastema tooth development via bidirectional antagonism of epithelial-mesenchymal FGF signaling. Dev Cell. 2006;11:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohazama A, Johnson EB, Ota MS, Choi HJ, Porntaveetus T, Oommen S, Itoh N, Eto K, Gritli-Linde A, Herz J, Sharpe PT. Lrp4 modulates extracellular intergration of cell signaling pathways in development. PLoS One. 2008;3(12):e4092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohazama A, Haycraft CJ, Seppala M, Blackburn J, Ghafoor S, Cobourne M, Martinelli DC, Fan CM, Peterkova R, Lesot H, Yoder BK, Sharpe PT. Primary cilia regulate shh activity in the control of molar tooth number. Development. 2009;136:897–903. doi: 10.1242/dev.027979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kassai Y, Munne P, Hotta Y, Penttila E, Kavanagh K, Ohbayashi N, Takada S, Thesleff I, Jernvall J, Itoh N. Regulation of Mammalian Tooth Cusp Patterning by Ectodin. Science. 2005;309:2067–2070. doi: 10.1126/science.1116848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahn Y, Sanderson BW, Klein OD, Krumlauf R. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by Wise (Sostdc1) and negative feedback from Shh controls tooth number and patterning. Development. 2010;137:3221–3231. doi: 10.1242/dev.054668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hacohen N, Kramer S, Sutherland D, Hiromi Y, Krasnow MA. Sprouty encodes a novel antagonist of FGF signaling that patterns apical branching of the Drosophila airways. Cell. 1998;92:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Charles C, Ovorakova M, Ahn Y, Marangoni P, Churava S, Biehs B, Jheon A, Lesot H, Balooch G, Kruumlauf R, Viriot L, Peterkova R, Klein OD. Regulation of tooth number by fine-tuning levels of receptor-tyrosine kinase signaling. Development. 2011;138:4063–4073. doi: 10.1242/dev.069195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Q, Murcia NS, Chittenden LR, Richards WG, Michaud EJ, Woychik RP, Yoder BK. Loss of the Tg737 protein results in skeletal patterning defects. Dev Dyn. 2003a;227:78–90. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robbins DJ, Fei DL, Riobo NA. The Hedgehog signal transduction network. Sci Signal. 2012;5:re6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dassule HR, Lewis P, Bei M, Maas R, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog regulates growth and morphogenesis of the tooth. Development. 2000;127:4775–4785. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cobourne MT, Miletich I, Sharpe PT. Restriction of sonic hedgehog signaling during early tooth development. Development. 2004;131:2875–2885. doi: 10.1242/dev.01163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee CS, Buttitta L, Fan CM. Evidence that the WNT-inducible growth arrest-specific gene 1 encodes an antagonist of sonic hedgehog signaling in the somite. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:11347–11352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201418298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Itasaki N, Jones CM, Mercurio S, Rowe A, Domingos PM, Smith JC, Krumlauf Wise, a context–dependent activator and inhibitor of Wnt signaling. Development. 2003;130:4295–4305. doi: 10.1242/dev.00674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laurikkala J, Kassai Y, Pakkasjärvi L, Thesleff I, Itoh N. Identification of a secreted BMP antagonist, ectodin, integrating BMP, FGF, and SHH signals from the tooth enamel knot. Dev Biol. 2003;264:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lintern KB, Guidato S, Rowe A, Saldanha JW, Itasaki N. Characterization of wise protein and its molecular mechanism to interact with both Wnt and BMP signals. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23159–23168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Munne PM, Tummers M, Järvinen E, Thesleff I, Jernvall J. Tinkering with the inductive mesenchyme: Sostdc1 uncovers the role of dental mesenchyme in limiting tooth induction. Development. 2009;136:393–402. doi: 10.1242/dev.025064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murashima-Suginami A, Takahashi K, Sakata T, Tsukamoto H, Sugai M, Yanagita M, Shimizu A, Sakurai T, Slavkin HC, Bessho K. Enhanced BMP signaling results in supernumerary tooth formation in USAG-1 deficient mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:1012–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Herz J, Bock HH. Lipoprotein receptors in the nervous system. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:405–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weatherbee SD, Anderson KV, Niswander LA. LDL-receptor-related protein 4 is crucial for formation of the neuromuscular junction. Development. 2006;133:4993–5000. doi: 10.1242/dev.02696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahn Y, Sims C, Logue JM, Weathererbee SD, Krumlauf R. Lrp4 and Wise interplay controls the formation and patterning of mammary and other skin appendage placodes by modulating Wnt signaling. Development. 2013;140:583–593. doi: 10.1242/dev.085118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cho SW, Kwak S, Woolley TE, Lee MJ, Kim EJ, Baker RE, Kim HJ, Shin JS, Tickle C, Maini PK, Jung HS. Interactions between Shh, Sostdc1 and Wnt signaling and a new feedback loop for spatial patterning of the teeth. Development. 2011;138:1807–1816. doi: 10.1242/dev.056051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao X, Zhang Z, Song Y, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Hu Y, Fromm SH, Chen Y. Transgenically ectopic expression of Bmp4 to the Msx1 mutant dental mesenchyme restores downstream gene expression but represses Shh and Bmp2 in the enamel knot of wild type tooth germ. Mech Dev. 2000;99:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu F, Chu EY, Watt B, Zhang Y, Gallant NM, Andl T, Yang SH, Lu MM, Piccolo S, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Taketo MM, Morrisey EE, Atit R, Dlugosz AA, Millar SE. Wnt/betacatenin signaling directs multiple stages of tooth morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;313:210–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pinheiro M, Freire-Maia N. Ectodermal dysplasias: a clinical classification and a causal review. Am J Med Genet. 1994;53:153–162. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320530207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kere J, Srivastava AK, Montonen O, Zonana J, Thomas N, Ferguson B, Munoz F, Morgan D, Clarke A, Baybayan P, Chen EY, Ezer S, Saarialho-Kere U, de la Chapelle A, Schlessinger D. X-linked anhidrotic (hypohidrotic) ectodermal dysplasia is caused by mutation in a novel transmembrane protein. Nat Genet. 1996;13:409–416. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mikkola ML. Controlling the number of tooth rows. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe53. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.285pe53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grüneberg H. The molars of the tabby mouse, and a test of the 'single-active X-chromosome' hypothesis. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;15:223–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ferguson BM, Brockdorff N, Formstone E, Ngyuen T, Kronmiller JE, Zonana J. Cloning of Tabby, the murine homolog of the human EDA gene: evidence for a membrane-associated protein with a short collagenous domain. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1589–1594. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Srivastava AK, Pispa J, Hartung AJ, Du Y, Ezer S, Jenks T, Shimada T, Pekkanen M, Mikkola ML, Ko MS, Thesleff I, Kere J, Schlessinger D. The Tabby phenotype is caused by mutation in a mouse homologue of the EDA gene that reveals novel mouse and human exons and encodes a protein (ectodysplasin-A) with collagenous domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:13069–13074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Laurikkala J, Mikkola M, Mustonen T, Aberg T, Koppinen P, Pispa J, Nieminen P, Galceran J, Grosschedl R, Thesleff I. TNF signaling via the ligand-receptor pair ectodysplasin and edar controls the function of epithelial signaling centers and is regulated by Wnt and activin during tooth organogenesis. Dev Biol. 2001;229:443–455. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mustonen T, Pispa J, Mikkola ML, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Pakkasjarvi JR, Thesleff I. Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by ectodysplasin-A1. Dev Biol. 2003;259:123–136. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tucker AS, Headon DJ, Courtney JM, Overbeek P, Sharpe PT. The activation level of the TNF family receptor, Edar, determines cusp number and tooth number during tooth. Development Dev Biol. 2004;268:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fliniaux I, Mikkola ML, Lefebvre S, Thesleff I. Identification of. dkk4 as a target of Eda-A1/Edar pathway reveals an unexpected role of ectodysplasin as inhibitor of Wnt signalling in ectodermal placodes. Dev Biol. 2008;320:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pummila M, Fliniaux I, Jaatinen R, James MJ, Laurikkala J, Schneider P, Thesleff I, Mikkola ML. Ectodysplasin has a dual role in ectodermal organogenesis: inhibition of Bmp activity and induction of Shh expression. Development. 2007;134:117–125. doi: 10.1242/dev.02708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kavanagh KD, Evans AR, Jernvall J. Predicting evolutionary patterns of mammalian teeth from development. Nature. 2007;449:427–432. doi: 10.1038/nature06153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maas R, Bei M. The genetic control of early tooth development. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8:4–39. doi: 10.1177/10454411970080010101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jia S, Zhou J, Gao Y, Baek JA, Martin JF, Lan Y, Jiang R. Roles of Bmp4 during tooth morphogenesis and sequential tooth formation. Development. 2013;140:423–432. doi: 10.1242/dev.081927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang Z, Lan Y, Chai Y, Jiang R. Antagonistic actions of Msx1 and Osr2 pattern mammlian teeth into a single row. Science. 2009;323:1232–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.1167418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou J, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Maltby KM, Liu Z, Lan Y, Jiang R. Osr2 acts downstream of Pax9 and interacts with both Msx1 and Pax9 to pattern the tooth developmental field. Dev Biol. 2011;353:344–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thomas BL, Tucker AS, Qui M, Ferguson CA, Hardcastle Z, Rubenstein JL, Sharpe PT. Role of Dlx-1 and Dlx-2 genes in patterning of the murine dentition. Development. 1997;124:4811–4818. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ferguson CA, Tucker AS, Heikinheimo K, Nomura M, Oh P, Li E, Sharpe PT. The role of effectors of the activin signaling pathway, activin receptors IIA and IIB, and Smad2, in patterning of tooth development. Development. 2001;128:4605–4613. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.22.4605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fjeld K, Kettunen P, Furmanek T, Kvinnsland IH, Luukko K. Dynamic expression of Wnt signaling-related Dickkopf1-2, and-3 mRNAs in the developing mouse tooth. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:161–166. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Arte S, Parmanen S, Pirinen S, Alaluusua S, Nieminen P. Candidate gene analysis of tooth agenesis identifies novel mutations in six genes and suggests significant role for WNT and EDA signaling and allele combinations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.van den Boogaard MJ, Creton M, Bronkhorst Y, Hout AVD, Hennekam E, Lindhout D, Cune M, Amstel HKPV. Mutations in WNT10A are present in more than half of isolated hypodontia cases. J Med Genet. 2012;49:327–331. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Plaisancié J, Bailleul-Forestier I, Gaston V, Vaysse F, Lacombe D, Holder-Espinasse M, Abramowicz M, Coubes C, Plessis G, Faivre L, Demeer B, Vincent-Delorme C, Dollfus H, Sigaudy S, Guillén-Navarro E, Verloes A, Jonveaux P, Martin-Coignard D, Colin E, Bieth E, Calvas P, Chassaing N. Mutations in WNT10A are frequently involved in oligodontia associated with minor signs of ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:671–678. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gaide O, Schneider P. Permanent correction of an inherited ectodermal dysplasia with recombinant EDA. Nat Med. 2003;9:614–618. doi: 10.1038/nm861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Casal ML, Lewis JR, Mauldin EA, Tardivel A, Ingold K, Favre M, Paradies F, Demotz S, Gaide O, Schneider P. Significant correction of disease after postnatal administration of recombinant ectodysplasin A in canine X-linked ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1050–1056. doi: 10.1086/521988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mauldin EA, Gaide O, Schneider P, Casal ML. Neonatal treatment with recombinant ectodysplasin prevents respiratory disease in dogs with X-linked ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:2045–2049. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kollar EJ, Baird GR. Tissue interactions in embryonic mouse tooth germs. I. Reorganization of the dental epithelium during tooth-germ reconstruction. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1970a;24:159–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kollar EJ, Baird GR. Tissue intereactios in embryonic mouse tooth germs. II. The inductive role of the dental papilla. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1970b;24:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ruch JV, Karcher-Djuricic V, Gerber R. Determinants of morphogenesis and cytodifferentiation of dental anloges in mice. J Biol Buccale. 1973;1:45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ruch JV, Lesot H, Karcher-Djuricic, Meyer JM. Extracellular matrix-mediated interactions during odontogenesis. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1984;151:103–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kollar E J, Fisher C. Tooth induction in chick epithelium: expression of quiescent genes for enamel synthesis. Science. 1980;207:993–995. doi: 10.1126/science.7352302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mina M, Kollar EJ. The induction of odontogenesis in non-dental mesenchyme combined with early murine mandibular arch epithelium. Arch Oral Biol. 1987;32:123–127. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(87)90055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang B, Li L, Du S, Liu C, Lin X, Chen Y, Zhang Y. Induction of human keratinocytes into enamel-secreting ameloblasts. Dev Biol. 2010;344:795–799. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]