Abstract

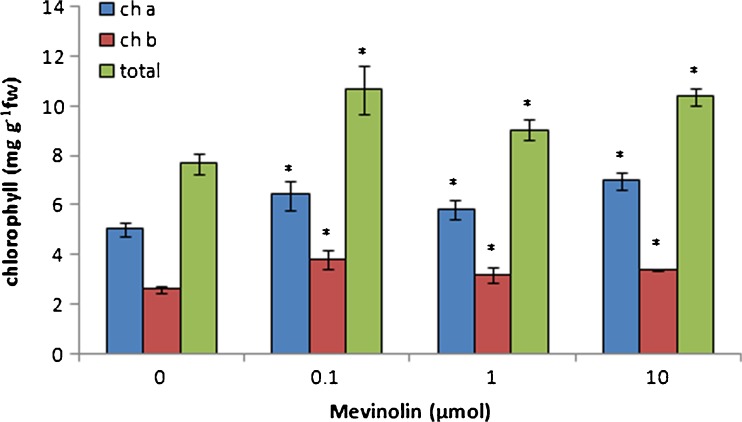

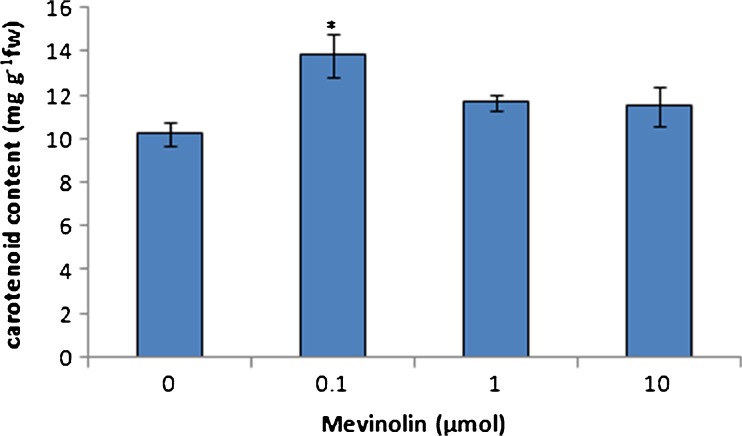

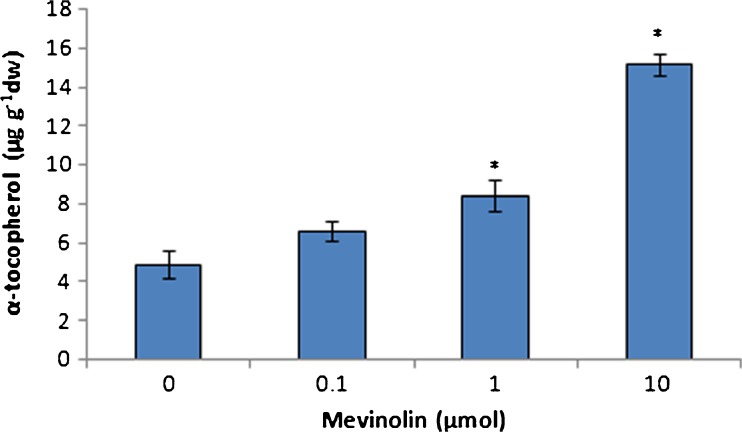

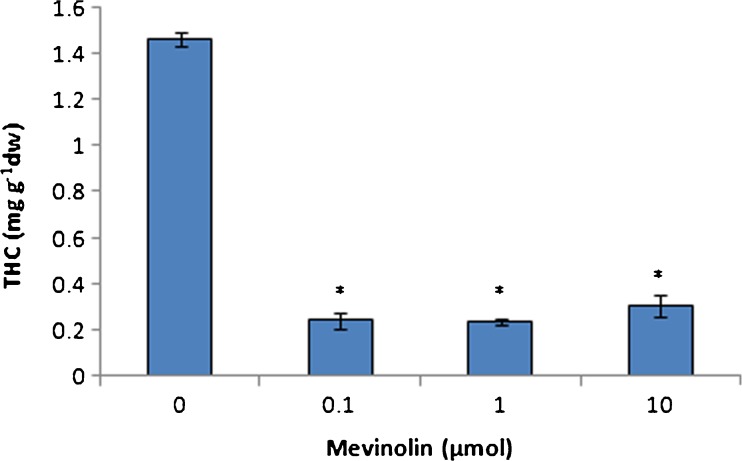

Plants synthesize a myriad of isoprenoid products that are required both for essential constitutive processes and for adaptive responses to the environment. Two independent pathways for the biosynthesis of isoprenoid precursors coexist within the plant cell: the cytosolic mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway. In this study, we investigated the inhibitory effect of the MVA pathway on isoprenoid biosynthesized by the MEP pathway in Cannabis sativa by treatment with mevinolin. The amount of chlorophyll a, b, and total showed to be significantly enhanced in treated plants in comparison with control plants. Also, mevinolin induced the accumulation of carotenoids and α-tocopherol in treated plants. Mevinolin caused a significant decrease in tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content. This result show that the inhibition of the MVA pathway stimulates MEP pathway but none for all metabolites.

Keywords: Cannabis sativa, Terpenoids, Mevinolin, Cannabinoids

Introduction

Isoprenoids represent the largest family of natural compounds. They function in respiration, signal transduction, cell division, membrane architecture, photosynthesis, and growth regulation. They also play an important role in the exchange of signals between plants and their environment or in defense against pathogens. These diverse compounds originate from a branched five-carbon unit, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). In plants, two pathways are utilized for the synthesis of IPP, the universal precursor for isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants. These pathways are mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway in the cytosol and 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway in the plastids. Usually, cytoplasmic isoprenoids such as sterols are synthesized from the MVA pathway, whereas plastidial isoprenoids such as isoprene, carotenoids, and abscisic acid and the side chains of chlorophylls and plastoquinone are synthesized from the MEP pathway (Lichtenthaler et al. 1997; Este’vez et al. 2001).

Although this subcellular compartmentation allows both pathways to operate independently in plants, there is an evidence that shows that the two pathways have interactions together. Specific inhibitors of the MVA pathway (mevinolin) and the MEP pathway (fosmidomycin) were used to perturb biosynthetic flux in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. The interaction between both pathways was studied at the transcriptional level by using GeneChip (Affymetrix) microarrays and at the metabolite level by assaying chlorophylls, carotenoids, and sterols (Laule et al. 2003).

Cannabis sativa L. (Cannabaceae) is the most important psychotropic drug and is consumed throughout the world. Cannabinoids are a group of terpenophenolic compounds found in C. Sativa. The highest cannabinoid concentration is found in the resin secreted by the plant flowering buds. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the psychoactive component of the hemp plant; other major non-psychoactive constituents include cannabidiol (CBD) and cannabinol (CBN) (Fellermeier et al. 2001; Hilling 2004). The production and accumulation of cannabinoids in plants of C. sativa follow a non-mevalonate pathway (Fellermeier et al. 2001).

Here, we report the interactions between the cytosolic and the plastidial pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in C. sativa by treatment with mevinolin and investigation of its effects on the MEP pathway. After inhibitor addition, key metabolites of the plastidial pathway (carotenoids and chlorophylls) and two cannabinoids (THC and CBD) were assayed.

Materials and methods

Plant material and treatment

Cannabis (C. sativa L.) saplings were grown from seed in pots (15 cm i.d.) filled with perlite under controlled conditions (a photoperiod of 14 h, day and night temperatures were 22 °C and 18 °C, respectively, irradiance of 70 μmol m−2 s−1, air humidity of 40–50 %). The plants were fertilized regularly with a Hogland’s nutrient solution every week.

A 12.4-mmol stock solution of mevinolin (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared after hydrolyzing the lactone ring in ethanolic NaOH (15 % [v/v] ethanol, 0.25 % [w/v] NaOH) at 60 °C for 1 h. Cannabis plants at the six-leaf stage (2 month-old plants) were used for mevinolin treatments. Mevinolin solutions (100 ml) with 0, 0.1, 1, and 10-μmol concentrations were added to pots every other day (three times). One day after the last treatment, plants were harvested for biochemical analysis and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The third pair of leaf was used for all analysis.

Chlorophyll and carotenoid determination

Chlorophyll and carotenoids were extracted from leaves with 95 % ethanol and quantified by measuring the absorbance at 664, 648, and 470 nm as described by Lichtenthaler et al. (1987).

Tocopherol extraction and measurement

Tocopherols were extracted as described for cereal seeds by Panfili et al. (2003), by grinding and homogenizing 25 mg of freeze–dried leaf material in 500 ml 100 % methanol. After 20 min of incubation at 30 °C, the samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant was transferred to new tubes, and the pellet was re-extracted twice with 250-μl 100 % methanol at 30 °C for 30 min, pooling all supernatants. Methanol extracts were subject to HPLC as described by Sattler et al. (2003).

Sample preparation for THC and CBD measurement

The third leaf pair was collected and used for cannabinoid measurement. Samples were dried at room temperature in darkness. Sample material (50 mg) was placed in a test tube with 1-ml chloroform. Sonication was carried out for 15 min. After filtration, the solvent was evaporated to dryness and the residue was dissolved in 0.5-ml methanol.

Cannabinoid extraction and chromatographic conditions

Chromatographic separations of cannabinoids were performed as described by Rustichelli et al. (1998). Cannabinoid peaks were identified by cannabinoid standards (THC and CBD) that were a generous gift from Dr. Jun Szopa Wroclaw University, Wroclaw, Poland.

Preparation of chloroplasts and pyruvate extraction

Chloroplasts were isolated from fresh cannabis leaves according to the method of Wei et al. (1987).

A 0.0125 % 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) solution was prepared by dissolving 0.1625 g of wet DNPH powder (∼30 % water) in 1,000-ml 2-N HCl. A 2-ml chloroplast suspension was added to 1 ml of a 0.0125 % solution of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine in 2-N HCl. After 15 min in a water bath at 37 °C, 5 ml of 0.6-N NaOH was added and the absorbance measured immediately on a Shimadzu model UV-160A spectrophotometer (420 nm filter, set at zero absorbance with reagent blank). The method was calibrated using sodium pyruvate as standard.

Pyruvic acid standards were prepared using sodium pyruvate. A 10-μmol/ml solution was prepared by dissolving 1.1-g sodium pyruvate in 1000 ml of distilled water. A subsequent tenfold dilution gave a 1-μmol/ml standard solution which was further diluted to prepare calibration standards.

Results and discussion

The influence of MVA pathway inhibition on MEP pathway terpenoids was studied by measuring of chloroplast terpenoids in cannabis plants treated with mevinolin. Carotenoids and phytol conjugates such as chlorophylls and tocopherols are biosynthesised by MEP pathway. Also, many secondary terpenoid metabolites such as cannabinoids in C. sativa are derived from MEP pathway. Mevinolin treatment caused an increase in the chlorophyll content of leaves. Chlorophyll a, b, and total content showed to be significantly enhanced in all of mevinolin concentrations (Fig. 1). Maximum increase in chlorophyll content was achieved at 0.1-μmol mevinolin. Mevinolin induced the accumulation of carotenoids in treated plants in comparison to control plants (Fig. 2). Low concentration of mevinolin was more effective and carotenoid content in plants treated with 1 and 10-μmol mevinolin did not show significant difference. Also, mevinolin stimulated α-tocopherol accumulation in treated plants (Fig. 3). This effect was more considerable in the high concentration of mevinolin (10 μmol) and we found a fivefold increase in the α-tocopherol content of treated plants in contrast with control plants.

Fig. 1.

Effect of mevinolin on the chlorophyll of cannabis plants. Values are means of three replications ± SD. Asterisks indicate the significance of difference at P < 0.05 level

Fig. 2.

Effect of mevinolin on carotenoids of cannabis plants. Values are means of three replications ± SD. Asterisks indicate the significance of difference at P < 0.05 level

Fig. 3.

Effect of mevinolin on α-tocopherol of cannabis plants. Values are means of three replications ± SD. Asterisks indicate the significance of difference at P < 0.05 level

Our work demonstrates a specific interaction between MVA and MEP pathway in cannabis plant. Inhibition of MVA pathway by mevinolin stimulated MEP pathway occurred, probably because this pathway obligate to prepare IPP precursor for all terpenoids (include cytosolic and plastidial terpenoids).

Rodríguez-Concepción et al. (2004) reported an upregulated uptake of MVA-derived precursors for plastidial isoprenoid synthesis in Arabidopsis seedlings. Strong biochemical evidence for such an exchange of precursors between the cytosol and the plastid was reported (Kasahara et al. 2002; Nagata et al. 2002; Hemmerlin et al. 2003).

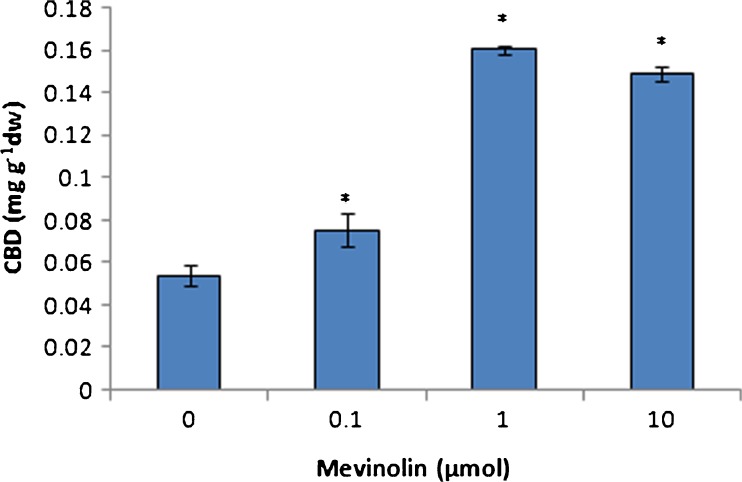

THC and CBD are two most important cannabinoids in cannabis. The results showed that THC content decreased in plants treated with mevinolin (Fig. 4). This difference was more significant and we found sevenfold decrease in the amount of THC. On the other hand, CBD accumulation was stimulated by mevinolin treatment specially in high concentrations of mevinolin (Fig. 5). Similarly, inhibition in artemisinin accumulation was observed in the presence of fosmidomycin, the competitive inhibitor of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductase (DXR). Artemisin is a sesquiterpene-lactone isolated from the aerial parts of Artemisia annua plants that is biosynthesised by MVA pathway (Ram et al. 2010).

Fig. 4.

Effect of mevinolin on THC of cannabis plants. Values are means of three replications ± SD. Asterisks indicate the significance of difference at P < 0.05 level

Fig. 5.

Effect of mevinolin on CBD of cannabis plants. Values are means of three replications ± SD. Asterisks indicate the significance of difference at P < 0.05 level

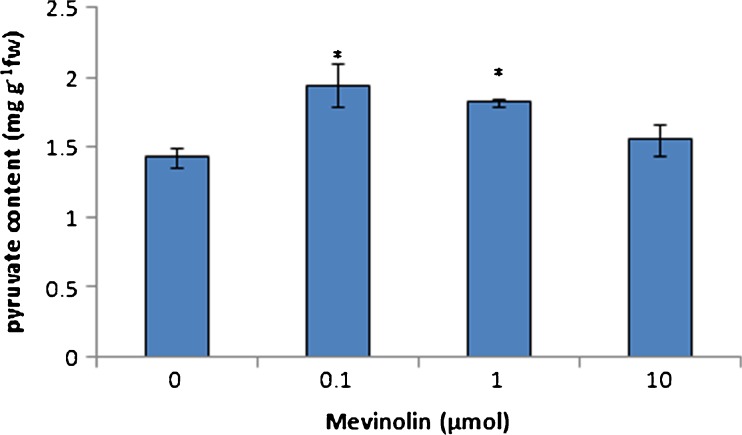

Pyruvate is a substrate for MEP pathway terpenoids. To investigate existence of a correlation between changes in terpenoid and pyruvate content, we analyzed the amount of this compound in chloroplasts. The treatment of plants with mevinolin increased the accumulation of pyruvate. These changes were significant in all concentration of mevinolin (Fig. 6). This result showed that inhibition of MVA pathway not only activates MEP pathway enzymes but also shifts substrates in to the MEP pathway.

Fig. 6.

Effect of mevinolin on chloroplast pyruvate of cannabis plants. Values are means of three replications ± SD. Asterisks indicate the significance of difference at P < 0.05 level

The data presented in this paper provide further evidence of the relationship between the MVA and MEP pathways and thus it seem that in the case of inhibition of one pathway priority, is with primary metabolites.

References

- Este’vez JM, Cantero A, Reindl A, Reichler S, Leo´n P. 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase, a limiting enzyme for plastidic isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22901–22909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellermeier M, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Zenk MH. Biosynthesis of cannabinoids: incorporation experiments with 13C-labeled glucoses. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1596–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerlin A, Hoeffler JF, Meyer O, Tritsch D, Kagan IA, Grosdemange-Billiard C. Cross-talk between the cytosolic mevalonate and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate pathways in tobacco Bright Yellow-2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26666–26676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilling KW. A chemotaxonomic analysis of terpenoid variation in Cannabis. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2004;32:875–891. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2004.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara H, Hanada A, Kuzuyama T, Takagi M, Kamiya Y, Yamaguchi S. Contribution of the mevalonate and methylerythritol phosphate pathways to the biosynthesis of gibberellins in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45188–45194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laule O, Furholz A, Chang HS, Zhu T, Wang X, Heifetz PB. Crosstalk between cytosolic and plastidial pathways of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol. 2003;100:6866–6871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031755100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:350–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK, Rohmer M, Schwender J. Two independent biochemical pathways for isopentenyl diphosphate and isoprenoid biosynthesis in higher plants. Physiol Plant. 1997;101:643–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb01049.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata N, Suzuki M, Yoshida S, Muranaka T. Mevalonic acid partially restores chloroplast and etioplast development in Arabidopsis lacking the non-mevalonate pathway. Planta. 2002;216:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0871-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panfili G, Fratianni A, Irano M. Normal phase high-performance liquid method for the determination of tocopherols and tocotrienols in cereals. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:3940–3944. doi: 10.1021/jf030009v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram M, Khan MA, Jha P, Khan S, Kiran U, Ahmad MM, Javed S, Abdin MZ. HMG-CoA reductase limits artemisinin biosynthesis and accumulation in Artemisia annua L. plants. Acta Physiol Plant. 2010;32:859–866. doi: 10.1007/s11738-010-0470-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrıguez-Concepcion M, Fores O, Martinez-Garcıa JF, Gonzalez V, Phillips MA, Ferrer A, Boronat A. Distinct light-mediated pathways regulate the biosynthesis and exchange of isoprenoid precursors during Arabidopsis seedling development. Plant Cell. 2004;16:144–156. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustichelli C, Ferioli V, Baraldi M, Zanoli P, Gamberini G. Analy of cannabinoids in fiber hemp plant varieties (Cannabis sativa L.) by high-performance liquid chromatography. Chromatographia. 1998;47:215–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02467674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler SE, Cahoon EB, Coughlan SJ, DellaPenna D. Characterization of tocopherol cyclases from higher plants and cyanobacteria. Evolutionary implication for tocopherol synthesis and function. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:2184–2195. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei JM, Shen YK, Li DY. Study about hydrogen atom participating in photophosphorylation. Sci Bull Sin. 1987;2:144–147. [Google Scholar]