Abstract

TNF-stimulated gene/protein-6 (TSG-6) is expressed by many different cell types in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines and plays an important role in the protection of tissues from the damaging consequences of acute inflammation. Recently, TSG-6 was identified as being largely responsible for the beneficial effects of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells, for example in the treatment of animal models of myocardial infarction and corneal injury/allogenic transplant. The protective effect of TSG-6 is due in part to its inhibition of neutrophil migration, but the mechanism(s) underlying this activity remain(s) unknown. Here we have shown that TSG-6 inhibits chemokine-stimulated trans-endothelial migration of neutrophils via a direct interaction (KD ~25 nM) between TSG-6 and the glycosaminoglycan-binding site of CXCL8, which antagonizes the association of CXCL8 with heparin. Furthermore, we found that TSG-6 impairs the binding of CXCL8 to cell surface glycosaminoglycans and the transport of CXCL8 across an endothelial cell monolayer. In vivo this could limit the formation of haptotactic gradients on endothelial heparan sulfate proteoglycans and, hence, integrin-mediated tight adhesion and migration. We further observed that TSG-6 suppresses CXCL8-mediated chemotaxis of neutrophils; this lower potency effect might be important at sites where there is high local expression of TSG-6. Thus, we have identified TSG-6 as a CXCL8-binding protein, making it the first soluble mammalian chemokine-binding protein to be described to date. We have also revealed a potential mechanism whereby TSG-6 mediates its anti-inflammatory and protective effects. This could inform the development of new treatments for inflammation in the context of disease or post transplantation.

Introduction

Neutrophils play an essential role in the inflammatory response to infection and injury, which is dependent on their rapid recruitment from the vasculature. This occurs via a multistep process that involves sequential tethering and rolling, activation by chemoattractants (e.g. chemokines), tight adhesion and trans-endothelial migration (1). However, the destructive potential of neutrophils requires that their extravasation be tightly regulated, otherwise tissue damage occurs, as seen in conditions such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and asthma. The chemokine CXCL8 (IL-8) plays a key role in neutrophil activation and transmigration (2). It is produced in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli, e.g. by endothelial cells (3), monocytes/macrophages and mast cells (4), and interacts with glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), such as heparan sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS) (5), on the vascular endothelium (6-8). GAG binding mediates presentation of CXCL8 to its G protein-coupled receptors on neutrophils, i.e. CXCR1 and CXCR2 (9), enables chemokine oligomerisation (where the monomeric and dimeric forms of CXCL8 have differential functions in vivo (10)) and generates haptotactic gradients that guide neutrophil recruitment (11,12). There is evidence that tissue-specific variations in the content, concentration and distribution of GAGs can modulate the CXCL8 monomer-dimer equilibrium and, thereby, regulate neutrophil extravasation (13).

TSG-6 (TNF-stimulated gene/protein-6), an ~35 kDa secreted glycoprotein (14), is expressed at sites of inflammation and injury; e.g. it is abundant in the synovial fluids of patients with inflammatory arthritis (15) and serum concentrations of TSG-6 correlate with the progression of murine proteoglycan-induced arthritis (PGIA) (16). There is growing evidence that TSG-6 acts to inhibit the extravasation of neutrophils in vivo (17-23), affecting both their rolling and trans-endothelial migration (17,19). For example, TSG-6-deficient mice develop much more severe PGIA than controls, with elevated neutrophil infiltration into the paw joints (20). Furthermore, secretion of TSG-6 by multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) has been shown to reduce inflammatory damage in rodent models of myocardial infarction (21), corneal wounding (22) and corneal transplantation (24). These protective properties of TSG-6 and the fact that it is produced primarily in the context of inflammation suggest that it forms part of an endogenous pathway to limit tissue damage during acute inflammatory episodes; TSG-6 is released from the secretory granules of neutrophils (25) and mast cells (16) as well as being expressed by macrophages (14,26) and a wide variety of stromal cell types (18). While it is evident that the inhibitory effect of TSG-6 on neutrophil trans-endothelial migration (17,19) contributes to its protective effects in inflammatory models, the molecular basis of this activity has not yet been determined.

TSG-6 consists mainly of contiguous Link and CUB modules (14,18). It interacts with protein ligands, including inter-α-inhibitor (17,27) and thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) (28), as well as with various GAGs, e.g. heparin, HS, chondroitin-4-sulfate (C4S), dermatan sulfate and hyaluronan (HA) (27,29,30). All of these ligands bind to the Link module domain of TSG-6, which is also responsible for the inhibition of neutrophil migration (17,19); however, it is not clear whether any of these interactions contribute to TSG-6’s anti-migratory activity (17).

Here we have demonstrated that TSG-6 acts to inhibit CXCL8-induced trans-endothelial migration of human neutrophils via a direct interaction between the TSG-6 Link module and CXCL8, which antagonizes the binding of CXCL8 to heparin/HS. Our data indicate that TSG-6 can impair the transport of CXCL8 across the endothelium and its presentation by cell surface GAGs. At high concentrations TSG-6 was also seen to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis. This work identifies TSG-6 as the first soluble, mammalian chemokine-binding protein and reveals a molecular mechanism for its tissue-protective effects during inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Protein and GAG preparation

Full-length, wild type (WT) recombinant human TSG-6 (rhTSG-6), its isolated Link module (Link_TSG6) and biotinylated Link_TSG6 were produced as described previously (29,31); the Link_TSG6_D (K34A/K54A) and Link_TSG6_T (K20A/K34A/K41A) mutants were prepared/characterized as in (27). Wild type CXCL8 and the CXCL8_S (R68A) and CXCL8_T (K64A/K67A/R68A) mutants, expressed and purified as described in (32), and CCL3, CCL5 and CXCL11 were provided by the Pharmaceutical Research Laboratory (Amanda E.I. Proudfoot, Geneva, Switzerland. Heparin (4th International Standard) was biotinylated as described in (33).

Cell culture

All cell cultures were incubated at 37°C and 5% (v/v) CO2. EA.hy 926 cells and Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) were cultured in DMEM with 10% (v/v) FBS and Endothelial Basal Medium (EBM-2; Lonza), respectively. HL-60 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium with 20% (v/v) FBS; differentiation to neutrophil-like cells, as assessed by CD11b up-regulation and morphological changes, was induced by incubation with 1.5% (v/v) DMSO for 120 h (34). The murine pre-B cell line 300-19 (35) and stable transfectants expressing CXCR1 (clone 1B4) or CXCR2 (clone 1D5) were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (w/v) glutamine and 5 × 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, under puromycin (1.5 μg/ml) selection (35).

CXCL8 transport and chemokine-induced neutrophil transmigration across endothelial cell monolayers

EA.hy 926 cells were seeded on top of 6.5 mm Transwell filters in 24-well plates (Corning permeable supports, 3 μM polyester membrane), HUVEC cells were seeded in the same way following coating of the filters with fibronection (10 μg/ml in PBS for 1 h at 37°C). Cells (5×104 cells/well in 100 μl media) were incubated at 37°C overnight, with 600 μl of media below the membrane. Monolayer formation was confirmed by eye, using a light microscope, cells were washed with PBS and Transwells were then transferred to fresh wells containing serum-free medium with or without chemokine in the absence/presence of rhTSG-6 or Link_TSG6 (WT or mutant) at the concentrations indicated.

For transmigration assays differentiated HL-60 cells (as a model of human neutrophils (34)) or human neutrophils isolated from buffy coats (36) were washed, re-suspended (3.75 × 106 cells/ml) in fresh DMEM and added (750,000 cells/well) to the top of endothelial monolayers; Transwells were then incubated at 37°C, for 24 h (HL-60 cells) or 2 h (primary neutrophils) with CXCL8 ± TSG-6 in the lower chamber. Migrated neutrophils were recovered from the media below each membrane by centrifugation (10 min, 400 × g) and counted.

The transport of CXCL8 across endothelial cell monolayers was investigated using a modification of the method described in (37). Biotinylated CXCL8 (b-CXCL8; prepared as in (38) and shown to signal through CXCR2 with similar efficiency to unmodified CXCL8) was added (3 nM) below HUVEC monolayers, in the absence/presence of Link_TSG6 (5-fold molar excess), and Transwells were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Media were collected from the upper and lower chambers, followed by incubation with 10 × PBS for 3 min to recover any CXCL8 bound to cell surface GAGs; cells were then lysed with RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X-100, 1% Sodium-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA). All samples were subject to SDS-PAGE and CXCL8 was detected and quantified by western blot analysis with Streptavidin conjugated to IR Dye 800CW (LI-COR Biosciences) using an Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Analysis of the TSG-6 interaction by surface plasmon resonance

SPR analysis was carried out using a Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare), where ligands (i.e. Link_TSG6, rhTSG-6 or CXCL8) were immobilized onto a C1 Biacore chip (~500 response units (RU)) as follows. The flow rate was set at 40 μl/min and the surface was equilibrated with SPR running buffer, i.e. SPR 6.0 (10 mM NaOAc, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20, pH 6) or SPR 7.2 (10 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20, pH 7.2), for 1 h (39). Paired cells (on the SPR chip) were then activated by injecting 70 μl of a 1:1 mixture of 0.2 M 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) and 0.1 M N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (39,40). Protein ligands (rhTSG-6, Link_TSG6 or CXCL8 at 20 μg/ml) were immobilized by passing them over one of the activated cells, using buffer conditions found to be optimal in initial scouting experiments (rhTSG-6 in 10 mM sodium acetate pH 6, Link_TSG6 and CXCL8 in 10 mM Hepes pH 7.4), until the signal increased by 500 RU. Any remaining active sites in the reference and ligand-containing cells were then blocked, by injecting 1 M ethanolamine (70 μl) (39,40). Analytes (rhTSG-6, CXCL8 or other chemokines), at a range of concentrations, were passed over the immobilized CXCL8, rhTSG-6 or Link_TSG6 in SPR running buffer at either pH 6 (SPR 6.0) or pH 7.2 (SPR 7.2); the resulting sensograms were analysed using the 1:1 Langmuir interaction model with BiaEvaluation software (GE Healthcare).

Characterisation of the CXCL8-TSG-6 interaction using plate-based binding assays

Mictrotitre plate assays to compare the interaction of CXCL8 with full-length TSG-6 and its isolated Link module, were carried out essentially as described in (27,41). rhTSG-6 or Link_TSG6 (50 pmol/well), in coating buffer (20 mM Na2CO3, pH 9.6), was immobilized onto 96-well Nunc MaxiSorp plates (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) by incubation overnight at room temperature. Plates were washed three times and blocked with 1% (w/v) BSA for 90 min at 37°C. After further washing, CXCL8 (0-500 nM) was added to each well and plates were incubated for 2 h at room temperature and then for 90 min at room temperature with biotinylated anti-human CXCL8 antibody (Peprotech; 0.3 μg/ml). Bound CXCL8 was detected using Extravidin-Alkaline Phosphatase (1:10,000; Sigma), followed by SIGMAFAST™ p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution (200 μl/well; Sigma), with absorbance measurements at 405 nm being taken after 10 min. To determine the specificity of the CXCL8-Link_TSG6 interaction, CXCL8 (50 pmol/well) was immobilized onto MaxiSorp plates overnight and biotinylated Link_TSG6 (10 nM) was added in the fluid phase, in combination with unlabelled Link_TSG6 (0-1000 nM). Binding was detected as described above.

CXCL8-heparin binding assays

Microtitre plate assays were carried out essentially as described in (27,33). Briefly, CXCL8, CXCL8_S or CXCL8_T (50 pmol/well in 20 mM Na2CO3, pH 9.6) were immobilized onto 96-well Nunc MaxiSorp plates (Thermo-Fisher Scientific) by incubation at room temperature overnight. All subsequent washes (3× after each incubation), dilutions and incubations were performed in SAB6 (10 mM NaOAc, 150 mM NaCl, 2% (v/v) Tween-20, pH 6). After blocking with 5% (w/v) BSA, for 90 min at 37°C, biotinylated-heparin (b-heparin) was added alone (0-100 ng/well) or (at 25 ng/well) in combination with TSG-6 proteins (0-1000 nM) for 4 h at room temperature. Bound b-heparin was detected by addition of Extravidin-Alkaline Phosphatase (1:10,000; Sigma) followed by SIGMAFAST™ p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution (200 μl/well; Sigma). Absorbance measurements at 405 nm were taken after 10 min and corrected against blank wells.

Interaction of CXCL8 with cell surface receptors

Binding of CXCL8 to murine 300-19 cells (35) stably expressing CXCR1 (clone 1B4) or CXCR2 (clone 1D5) was determined by flow cytometry, using a biotinylated human CXCL8 Fluorkine kit (R&D Systems) according to the supplier’s instructions. Cells (1 × 105 in PBS) were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with b-CXCL8 that had been pre-incubated (1 h at 37°C) in the absence or presence of Link_TSG6. Cell-associated CXCL8 was detected, following addition of avidin-fluorescein, using a CyAn ADP flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) with excitation at 488 nm. Gating was applied to select live cells on the basis of forward scatter versus side scatter.

CXCL8-mediated chemotaxis of human neutrophils

Neutrophils were purified from fresh human blood and their chemotaxis through 3 μm pores was assayed as reported previously (36). CXCL8 (1 nM) and Link_TSG6 (0-10 μM) were placed in the lower chambers of 96-well ChemoTx plates (Neuroprobe, Cabin John, MD), neutrophils (in RPMI 1640 w/o Red Phenol, 2% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS, 1% Penicillin/streptomycin, 1% (w/v) L-glutamine) were added to the upper chambers and migrated cells were counted (using a CyQUANT kit; Molecular Probes) after 45 min at 37°C.

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences between groups were identified by repeated measures ANOVA, and Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to compare each condition with controls (GraphPad Prism, version 5.0). A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analyses involving pairwise comparisons of data sets. Levels of significance are indicated, where *, ** and *** = p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively. Where data are presented as mean values ± S.E.M., the number of times that the experiment was repeated (n) is indicated, with all conditions being set up in triplicate.

Results

TSG-6 inhibits CXCL8-mediated trans-endothelial migration of neutrophils via its Link module domain

TSG-6 is a potent inhibitor of neutrophil extravasation in vivo (17,20) and, since CXCL8 is an important chemoattractant and activator for neutrophils, we chose to investigate the effects of TSG-6 on CXCL8 using a Transwell assay. In this system CXCL8 up-regulated the trans-endothelial migration of both differentiated HL-60 cells (Fig. 1A) and primary human neutrophils (Fig. 1B) in a dose-dependent manner; 3.6 nM CXCL8 increased the numbers of migrated cells by ~2- and ~6- fold, respectively, which is consistent with previous studies (19,42). Under these conditions, we showed that a 5-fold molar excess (i.e. 18 nM) of Link_TSG6 completely ablated the CXCL8-induced migration of differentiated HL-60 cells (Fig. 1C) and significantly reduced the migration of primary human neutrophils (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, Link_TSG6 and full-length rhTSG-6 had equivalent neutrophil inhibitory effects (Fig. 1E), confirming that this activity resides within the Link module domain of TSG-6. Given that the inhibition of neutrophil migration was seen when both the CXCL8 and TSG-6 proteins were added to Transwells below the endothelial cell layer, we hypothesized that this activity of TSG-6 was due to its direct interaction with CXCL8.

Figure 1. TSG-6 inhibits trans-endothelial migration of differentiated HL-60 cells via interaction of its Link module domain with CXCL8.

Migration of differentiated HL-60 cells across a monolayer of EA.hy 926 cells (A) or primary human neutrophils across a monolayer of HUVECs (B) was measured in response to a range of concentrations of WT CXCL8 (1.2, 3.6, 6, 9 and 12 nM) (n = 3). Migration of differentiated HL-60 cells across a monolayer of EA.hy 926 cells was measured in response to (C) CXCL8 (3.6 nM (+)) alone or in combination with Link_TSG6 (at 1:1, 2:1, 5:1 and 10:1 molar ratios) (n = 8 to 28) or (E) CXCL8 (3.6 nM (+)) alone or in combination with a 5-fold molar excess of Link_TSG6 or rhTSG-6 (n = 8). Migration of primary human neutrophils across a monolayer of HUVECs was determined in response to (D) WT CXCL8 (3.6 nM (+)) alone or in combination with Link_TSG6 (at 1:1, 2:1, 5:1 and 10:1 molar ratios) (n = 3). Data are plotted as mean values (± SEM) relative to non-stimulated controls (−), where *, ** and *** = p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively, compared to non-stimulated controls (A, B) or to CXCL8 alone (C, D, E), as determined using repeated measures ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni’s post hoc test. In this, and subsequent figures, the dotted line indicates baseline neutrophil migration in the absence of CXCL8 stimulus.

TSG-6 binds to CXCL8 via its Link module

We investigated the binding of TSG-6 to CXCL8 using SPR, which revealed that these proteins interact with high affinity (see Table 1). For example, when CXCL8 was flowed over immobilized rhTSG-6, at pH 6 (Fig. S1A) or pH 7.2 (Fig. S1D), analysis of the resultant sensograms (using the 1:1 Langmuir model) revealed affinities (KD) of 26 nM and 19 nM, respectively. When rhTSG-6 was used as the analyte (and CXCL8 immobilized), KD values within the same order of magnitude were obtained; i.e. 74 nM at pH 6 (Fig. S1C) and 20 nM at pH 7.2 (Fig. S1F). Similar affinities were also observed with immobilized Link_TSG6 (6 nM at pH 6 (Fig. S1B) and 21 nM at pH 7.2 (Fig. S1E)), demonstrating that the interaction with CXCL8 is mediated via the Link module of TSG-6; this was further confirmed in plate-based assays where CXCL8 bound to immobilized rhTSG-6 and Link_TSG6 (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, unlabeled Link_TSG6 competed for the binding of biotinylated Link_TSG6 to immobilized CXCL8 with an IC50 of 15 ± 3 nM (Fig. 2B); i.e. comparable to the KD value determined above by SPR.

Table 1. Dissociation constants for the interactions of rhTSG-6 and Link_TSG6 with CXCL8 (wild-type and mutants with reduced heparin-binding) and other chemokines.

| Immobilised Ligand | Fluid-phase Analyte | KD (nM)a | Chi2 | kon (M−1s−1) | koff (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rhTSG-6 | CXCL8 (pH 6) | 26 | 6.5 | 2.9 × 104 | 7.5 × 10−4 |

| rhTSG-6 | CXCL8 (pH 7.2) | 19 | 16.7 | 3.4 × 104 | 6.5 × 10−4 |

| Link_TSG6 | CXCL8 (pH 6) | 6 | 44.3 | 5.3 × 104 | 3.2 × 10−4 |

| Link_TSG6 | CXCL8 (pH 7.2) | 21 | 18.1 | 1.9 × 104 | 1.1 × 10−3 |

| rhTSG-6 | CXCL8_Sb (pH 6) | 581 | 2.2 | 3.1 × 103 | 1.8 × 10−3 |

| rhTSG-6 | CXCL8_Tc (pH 6) | 2,109 | 1.4 | 640 | 1.4 × 10−3 |

| Link_TSG6 | CXCL8_S (pH 6) | 203 | 2.0 | 8.4 × 103 | 1.7 × 10−3 |

| CXCL8d | rhTSG-6 (pH 6) | 74 | 8.9 | 5.7 × 103 | 4.2 × 10−4 |

| CXCL8 | rhTSG-6 (pH 7.2) | 20 | 15.3 | 2.3 × 104 | 1.1 × 10−3 |

| Link_TSG6 | CCL5 (pH 7.2) | 2 | 7.3 | 5.7 × 104 | 1.1 × 10−4 |

| rhTSG-6 | CXCL11 (pH 6) | 16.4 | 7.2 | 6.4 × 103 | 1.1 × 10−4 |

| rhTSG-6 | CCL3 (pH 6) | 15,100 | 7.4 | 4.4 × 103 | 6.6 × 10−3 |

KD values determined by full kinetic analysis of SPR data

CXCL8 R68A mutant

CXCL8 K64A/K67A/R68A mutant

No fittable data were generated when Link_TSG6 was used as the analyte, due to non-specific interactions between this protein and the biosensor chip

Figure 2. TSG-6 binds specifically to CXCL8 via its Link module domain.

(A) rhTSG-6 or Link_TSG6 (50 pmol/well) was immobilized overnight onto a MaxiSorp microtitre plate. CXCL8 (0-500 nM) was added in the fluid phase and binding was detected using a biotinylated anti-CXCL8 antibody (n = 8). (B) CXCL8 (50 pmol/well) was immobilised onto a MaxiSorp plate overnight and biotinylated Link_TSG6 (10 nM) was added in fluid phase in combination with unlabelled Link_TSG6 (0-1000 nM) (n = 4). Binding was detected using Extravidin alkaline phosphatase followed by disodium p-nitrophenyl phosphate; absorbance at 405 nm was determined after 10 min. Data were plotted as mean values ± SEM using Origin Pro (v8). In (B) an IC50 of 15 ± 3 nM was obtained for the inhibition of biotinylated Link_TSG6 binding to immobilized CXCL8 by unlabeled Link_TSG6.

Together these results indicate that there is a specific, high-affinity interaction between the Link module of TSG-6 and CXCL8 (with KD values in the range ~10-70 nM), which could contribute to the inhibition of chemokine-induced neutrophil migration. Overall, there was little difference between the binding affinities determined by SPR at pH 6 and pH 7.2; this isin contrast to other interactions of TSG-6, e.g. with HA (43), heparin (27,28) and TSP-1 (28), which are all sensitive to pH in the range pH 6 to pH 7.5.

The Link module of TSG-6 inhibits CXCL8-GAG interactions

Chemokine-GAG interactions play essential roles in neutrophil migration through enabling the sequestration of chemokines by HS proteoglycans (HSPG), and hence the formation of haptotactic gradients, on the lumen of the endothelium (5,11,12); they have also been implicated in the transport of chemokines (produced in interstitial tissues) across the endothelium (11). For example, mutants of CXCL8 with impaired heparin-binding activities showed deficient transcytosis and reduced accumulation on the apical surface of the endothelium in skin (7). Therefore, we investigated whether binding of TSG-6 to CXCL8 could antagonize the interaction between CXCL8 and heparin, a GAG that is often used as a model for HS due to its similar structure and greater availability. In plate-based assays, where immobilized WT CXCL8 bound to heparin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A), we found that Link_TSG6 and rhTSG-6 were similarly effective as competitors for this interaction (IC50s ~70 nM and ~80 nM, respectively); CXCL8-heparin binding was completely abolished in the presence of 0.5 to 1 μM TSG-6 protein (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Interaction between the Link module domain of T6G-6 and the GAG-binding site of CXCL8 inhibits CXCL8-heparin binding and CXCL8-mediated neutrophil transmigration.

WT or mutant CXCL8 (250 nM) was immobilized onto MaxiSorp plates and b-heparin (0-100 ng/well) (A) or b-heparin (25 ng/well) in combination with a range of concentrations of rhTSG-6 or Link_TSG6 (0-1000 nM) (B), or in combination with a range of concentrations of WT Link_TSG6, Link_TSG6_D or Link_TSG6_T (0-2000 nM) (C) was added in the fluid phase. Binding of b-heparin was detected using Extravidin alkaline phosphatase followed by disodium p-nitrophenyl phosphate; absorbance at 405 nm was determined after 5 min (A) or 10 min (B,C). Data are plotted as mean values (n = 8) ± SEM and fitted using Origin Pro (v8). KD values of 5 ± 12 nM and 26 ± 11 nM were determined for the binding of b-heparin to WT CXCL8 and CXCL8_D, respectively (A). IC50 values of (B) 81 ± 18 nM and 71 ± 14 nM for the inhibition of b-heparin binding to CXCL8 by rhTSG-6 and Link_TSG6, respectively, and (C) 105 ± 5 nM, 172 ± 3 nM and 45 ± 5 nM for the inhibition of this interaction by WT Link_TSG6, Link_TSG6_D and Link_TSG6_T, respectively, were determined. In (D), migration of differentiated HL-60 cells across an EA.hy 926 cell monolayer was determined in response to CXCL8 (3.6 nM (+)) alone or in combination with 5:1 molar ratios of WT Link_TSG6, Link_TSG6_D or Link_TSG6_T (n = 8). Data are plotted as mean values (± SEM) relative to non-stimulated controls (−), where ** and *** = p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively, compared to CXCL8 alone, as determined using repeated measures ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni’s post hoc test.

To determine whether this inhibitory effect was due to TSG-6 (a known heparin-binding protein) interacting with heparin we used the Link_TSG6 mutants K34A/K54A (Link_TSG6_D) and K20A/K34A/K41A (Link_TSG6_T), which have ~50% and ~10% of WT heparin-binding activity, respectively (27). Both mutants antagonized the CXCL8-heparin interaction; Link_TSG6_D had similar activity to WT Link_TSG6, whilst Link_TSG6_T showed enhanced activity with maximal inhibition at 0.125 μM (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, in the Transwell system, both Link_TSG6_D and Link_TSG6_T inhibited the trans-endothelial migration of differentiated HL-60 cells with potencies similar to WT Link_TSG6 (Fig. 3D). Overall, these data indicate that both the inhibitory effect of TSG-6 on CXCL8-induced neutrophil trans-migration and its impairment of the CXCL8-heparin interaction are independent of TSG-6’s heparin-binding activity.

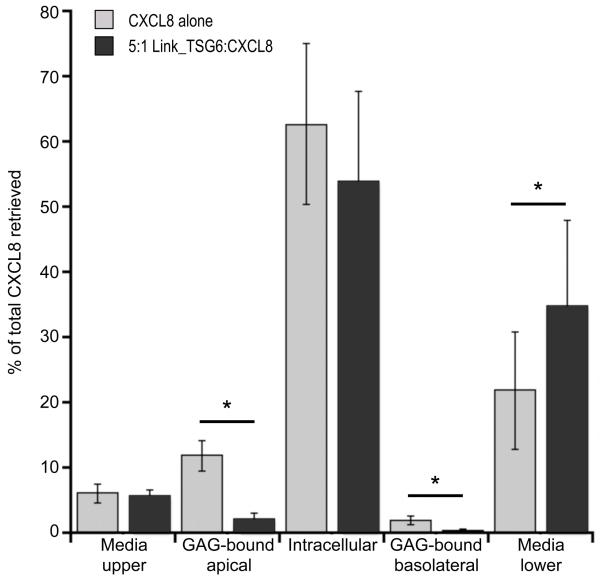

Using the Transwell system with b-CXCL8 and Link_TSG6 in the lower chamber, we went on to show that Link_TSG6 (at the same concentration seen to inhibit neutrophil trans-migration) caused significant reductions in (i) the binding of b-CXCL8 to GAGs on the basolateral surface of HUVECs (~4-fold), (ii) the movement of b-CXCL8 out of the lower Transwell chamber and (iii) the subsequent association of chemokine with GAGs on the apical cell surface (~5-fold) (Fig. 4). We observed no significant effect of Link_TSG6 on the amount of intracellular b-CXCL8. This could, at least in part, reflect that Link_TSG6 inhibits the GAG-mediated uptake of CXCL8 by endothelial cells, but has no effect on other mechanisms, e.g. via the duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC). In addition, Link_TSG6 did not alter the amount of b-CXCL8 in the media of the upper Transwell chamber. This is likely because the majority of CXCL8 present here is due to non-specific paracellular diffusion, as has been previously demonstrated (11), and is therefore independent of the transcytosis mechanism inhibited by Link_TSG6. Together, these data suggest that TSG-6 might inhibit both GAG-mediated transcytosis of CXCL8 and the presentation of CXCL8 on the lumen of the vascular endothelium.

Figure 4. TSG-6 inhibits the binding of CXCL8 to endothelial surface GAGs and the transport of CXCL8 across an endothelial cell monolayer.

HUVEC monolayers were incubated in Transwells with b-CXCL8 (3 nM), in the absence or presence of Link_TSG6 (15 nM), for 2 h. b-CXCL8, in the media from the upper and lower chambers, bound to GAGs on the apical and basolateral surfaces of the endothelial cells (recovered in 10 × PBS) and in the HUVEC lysates (intracellular), was quantified by western blot analysis using an Odyssey system (LI-COR). Data, represented as a percentage of the total b-CXCL8 recovered, are plotted as mean values (n = 6) ± SEM, where * indicates p<0.05 as determined by pairwise comparison of samples ± Link_TSG6 using the Student’s t-test.

TSG-6 inhibits CXCL8-mediated neutrophil transmigration by interacting with the GAG-binding surface of CXCL8 and blocking CXCL8-GAG binding

To further investigate the mechanism of TSG-6’s anti-migratory activity we used the CXCL8 mutants R68A (CXCL8_S) and K64A/K67A/R68A (CXCL8_T) (5,8,32), which we found to have reduced heparin-binding activity (~20-60% of WT) and no measurable activity, respectively (Fig. 3A). In SPR experiments TSG-6 showed weak binding to both mutants (Table 1 and Fig. S1G-I); the affinities for the CXCL8_S and CXCL8_T interactions with rhTSG-6 were reduced by 20-fold and 80-fold, respectively, compared to WT CXCL8 (due to slower rates of association and faster rates of dissociation). These data suggest that the heparin- and TSG-6-binding sites on CXCL8 overlap.

Despite its somewhat impaired heparin-binding function, CXCL8_S induced trans-endothelial migration of differentiated HL-60 cells (Fig. 5A) with similar efficiency to WT protein; in contrast, CXCL8_T had no such activity (Fig. 5B), reflecting the essential role of GAG-binding in CXCL8-mediated neutrophil migration. However, Link_TSG6 had no inhibitory effect on the CXCL8_S-mediated migration of either differentiated HL-60 cells (Fig. 5C) or primary human neutrophils (Fig. 5D), even when present at 10- or 20-fold molar excess. Since the affinity of TSG-6 for CXCL8_S is ~20-fold weaker than for WT CXCL8, these data indicate that a direct interaction between TSG-6 and CXCL8 is required to inhibit CXCL8-mediated trans-endothelial migration. These data indicate that TSG-6 might inhibit neutrophil migration by impairment of CXCL8 binding to endothelial cell GAGs and this is supported by our observation that Link_TSG6 and a heparin oligosaccharide (dp8) have essentially identical inhibitory effects on the interaction of b-CXCL8 with a HUVEC monolayer (data not shown).

Figure 5. The mutant CXCL8_S, with impaired binding to heparin and TSG-6, mediates trans-endothelial migration of neutrophils, but TSG-6 does not inhibit this activity.

Migration of differentiated HL-60 cells across EA.hy 926 monolayers (A, B, C) or primary human neutrophils across HUVEC monolayers (D) was measured in response to WT CXCL8 (3.6 nM) (A, B), CXCL8_S (3.6, 7.2, 12 and 24 nM) (n = 8) (A) or CXCL8_T (3.6, 7.2, 12 and 24 nM) (n = 8) (B) alone, or in response to (C) CXCL8_S (3.6 nM (+)) alone or in combination with Link_TSG6 (at 1:1, 5:1, 10:1 and 20:1 molar ratios) (n = 6) or (D) CXCL8_S (3.6 nM (+)) alone or in combination with Link_TSG6 (at 5:1 and 10:1 molar ratios) (n = 3). Data are plotted as mean values ± SEM, where *, ** and *** = p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively, compared to non-stimulated controls (A, B) or to CXCL8_S alone (C, D), as determined using repeated measures ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni’s post hoc test.

TSG-6 inhibits CXCL8-mediated neutrophil chemotaxis

In the absence of an endothelial cell monolayer, we observed dose-dependent inhibition by Link_TSG6 of CXCL8-induced neutrophil chemotaxis with an IC50 of 2.4 ± 0.3 μM (Fig. 6A). In order to promote neutrophil migration, CXCL8 must bind to CXCR1 and/or CXCR2. We, therefore, used flow cytometry to directly test the effect of TSG-6 on the interactions of CXCL8 with its receptors. Pre-incubation with Link_TSG6 gave rise to a dose-dependent reduction in the binding of b-CXCL8 to cell surface CXCR2, with an IC50 of ~5 μM (Fig. 6B); however, we did not detect any effect on the CXCL8-CXCR1 interaction even at molar excesses of Link_TSG6 as high of 600:1 (not shown). The similar potencies with which Link_TSG6 inhibited CXCL8-CXCR2 binding and CXCL8-induced chemotaxis indicate that TSG-6 can operate via an alternative mechanism to modulate CXCL8 activity, whereby its binding to the chemokine weakly inhibits subsequent interaction with CXCR2. However, this activity is only seen with μM concentrations of TSG-6, in contrast to its inhibition of neutrophil transmigration (~10 nM; Fig. 1C) and CXCL8-heparin binding (IC50 ~70 nM; Fig. 3B).

Figure 6. Link_TSG6 can inhibit the chemotaxis of human neutrophils and the interaction of CXCL8 with its receptor CXCR2.

(A) Purified human neutrophils were added to the upper chambers of ChemoTx plates, where the lower chambers contained CXCL8 (1 nM) alone or in combination with increasing concentrations of Link_TSG6 (0–20 μM). Migrated neutrophils were counted after 2 h; data were plotted as mean values (n = 3) ± SEM. (B) Biotinylated CXCL8 (120 nM), alone or following pre-incubation with Link_TSG6 (at 10:1 to 200:1 molar excess), was added to cells expressing CXCR2. Cell-associated CXCL8 was detected by flow cytometry following addition of avidin-conjugated fluorescein, with gating applied to select live cells. An overlay of histograms (incidents of absorbance against fluorescence), each representative of three independent experiments, is shown as an inset. Data, as a percentage of the maximal signal (i.e. CXCL8 alone), were plotted as mean values (n = 3) ± SEM, where * and *** = p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively relative to cells incubated with CXCL8 alone. Graphs were generated and data fitted using Origin Pro (v8) giving rise to an IC50 of 2.4 ± 0.3 μM for the inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis by Link_TSG6 (A), and an IC50 of 4.9 μM (i.e. ~41-fold molar excess) for the inhibition of CXCL8 binding to CXCR2 by Link_TSG6 (B).

Discussion

Here we have determined that TSG-6 is a novel ligand for the neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL8. This high affinity interaction (KD ~25 nM; an average of the values obtained by SPR) occurs via the Link module domain of TSG-6 and directly inhibits CXCL8-induced neutrophil trans-endothelial migration and, to a lesser extent, chemotaxis. Both TSG-6 and CXCL8 are GAG-binding proteins, where associations with GAGs are important in regulating their functions (27,44). We have demonstrated here that binding of TSG-6 to CXCL8 inhibits the interaction of CXCL8 with heparin and, thus, likely blocks binding to HS and other GAGs; consistent with this, TSG-6 was found to impair the presentation of CXCL8 on endothelial GAGs. The use of mutants revealed that suppression of CXCL8-GAG binding is independent of TSG-6’s heparin-binding properties and that the TSG-6- and GAG- binding surfaces on CXCL8 are, at least, partially overlapping.

We have also shown that, at high concentrations, TSG-6 antagonizes the binding of CXCL8 to its receptor CXCR2 and that this correlates with an inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis. CXCL8 has distinct GAG- and receptor- binding sites, in contrast to some other chemokines such as CCL3 and CCL4 (36). However, the structure of CXCL8 (45) reveals that these are close enough together that, by binding to a surface that primarily overlaps the GAG-binding site TSG-6 could partially occlude/perturb the receptor-binding site. This would be consistent with our observations that TSG-6 inhibits the CXCL8-heparin interaction more effectively than the CXCL8-CXCR2 interaction (i.e. with IC50 values of ~70-80 nM and ~5 μM, respectively).

The sites at which TSG-6 might act to regulate CXCL8-mediated neutrophil extravasation are summarized in Fig. 7. As noted above, the formation of haptotactic gradients, where CXCL8 is associated with proteoglycans on the lumenal surface of the vascular endothelium, is critical for the presentation of CXCL8 to its receptors on neutrophils (5,11,12). Our data indicate that TSG-6 can inhibit the immobilization of CXCL8 on endothelial GAGs, e.g. by blocking CXCL8-HS binding ((a) in Fig. 7). This would result in reduced concentrations of cell-associated versus fluid-phase chemokine (where the latter would then be washed away by venular flow) and/or upset the equilibrium between monomeric and dimeric CXCL8, thereby reducing receptor activation and/or increasing receptor desensitization and internalization (see (46)); GAG binding is directly coupled to the dimerization of CXCL8 (8), where the dimer and monomer have distinct roles in the formation of chemokine gradients in vivo (10). In turn, this would limit integrin-mediated attachment of neutrophils to the endothelium and their subsequent transmigration.

Figure 7. Potential mechanisms for the modulation of CXCL8 function by TSG-6.

Inhibition by TSG-6 of CXCL8-GAG interactions could antagonise (a) binding of CXCL8 to HSPGs on the lumenal surface of the endothelium, thereby preventing the formation of haptotactic gradients and/or (b) binding of CXCL8 to GAGs on the ablumenal surface, thus impairing transcytosis of CXCL8. Very high local concentrations of TSG-6 might inhibit the CXCL8-CXCR2 interaction (c, d), thereby limiting the movement of neutrophils in response a chemotactic gradient of CXCL8. TSG-6 and CXCL8 are represented by white (○) and black (●) circles, respectively.

CXCL8 that is produced, e.g. by macrophages, in inflamed or damaged extravascular tissue is transported to the lumenal surface of the endothelium via peri-cellular and trans-cellular mechanisms (11,37,47). DARC plays an important role in trancytosis (37,48,49), but this process is also dependent on the interaction of CXCL8 with HSPGs on the ablumenal surface of endothelial cells (11). Our data indicate that TSG-6, expressed at an inflammatory site, could potentially limit the transport of CXCL8 across the endothelium by antagonizing CXCL8-HSPG interactions ((b) in Fig. 7).

Human neutrophils carry the receptors CXCR1 that binds with high affinity to CXCL8, and less tightly to CXCL6, and CXCR2, which binds to CXCL1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 in addition to CXCL8 (9). There is evidence that CXCR1 and CXCR2 act in a coordinated manner, with CXCR2 being most important for early-stage CXCL8-induced neutrophil recruitment, whilst CXCR1 triggers cytotoxic effects, i.e. at sites of injury/infection (10,46). Our observation that TSG-6 inhibits the interaction of CXCL8 with cell-associated CXCR2 and also CXCL8-induced chemotaxis, with similar potencies, suggests that TSG-6 obstructs the receptor-binding surface of CXCL8. Antagonism of the CXCL8-CXCR2 interaction in vivo could prevent tight adhesion/diapedesis of neutrophils ((c) in Fig. 4) and/or their response to chemotactic gradients in the extravascular tissue ((d) in Fig. 4). The effect of TSG-6 on chemotaxis (IC50 ~2.5 μM) is ~250 fold less potent than its inhibition of neutrophil trans-migration (IC50 ~10 nM), suggesting that TSG-6 may only regulate chemotaxis in situations where it is present at a high local concentration, e.g. when secreted by neutrophils in response to inflammatory cytokines (25). This could reflect the greater affinity of the interaction between CXCL8 and CXCR2 (KD ~1 nM) (50) than between CXCL8 and heparin (low μM IC50 value) (5,32) and between CXCL8 and TSG-6 (KD ~25 nM). We did not detect any effect of TSG-6 on CXCL8 binding to CXCR1; however this does not exclude the possibility that the inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis by TSG-6 might involve perturbation of both CXCR1- and CXCR2-mediated processes.

It is becoming well established that TSG-6, e.g. when expressed by tissue-resident cells in response to inflammation, represents an endogenous pathway that is anti-inflammatory and protects tissues from damage, for instance through the inhibition of neutrophil migration (17-23). Previously reported mechanisms that might contribute to the regulation of neutrophil recruitment in vivo include (i) the formation of TSG-6-HA complexes that can modulate CD44-mediated leukocyte attachment to the vascular endothelium (see (51)) and (ii) attenuation by TSG-6 of TLR2/NF-κB signalling in resident macrophages resulting in reduced production of pro-inflammatory mediators (23), again perhaps by regulating HA/CD44 engagement. The results described here, where the binding of TSG-6 to CXCL8 directly suppresses the pro-migratory effects of CXCL8 are clearly independent of TSG-6’s HA-binding properties. Thus, we have identified a new mechanism whereby TSG-6 contributes to a negative feedback loop to limit excessive neutrophil recruitment at sites of inflammation. The CXCL8-binding activity of TSG-6 could largely explain its protective effects in in vivo models of inflammatory disease, regardless of the source of the TSG-6, i.e. endogenous, exogenously administered (see (18)) or MSC-expressed (21-24). This could also provide the mechanism whereby MSCs can promote the survival of tissue transplants in animal models given the recent finding that TSG-6 can suppress rejection of corneal allografts in mice (24) and that transplantation can give rise to high levels of CXCL8 expression (52); TSG-6 might limit inflammation post-surgery and thus prevent the onset of an adaptive immune response.

Here we have identified TSG-6 as a soluble chemokine-binding protein (CKBP) that, to our knowledge, is the first to be described in mammals. In addition to CXCL8, we have shown (using SPR) that TSG-6 interacts with some, but not all, of the CC and CXC chemokines tested. For example, it binds with high affinity to CCL5 (KD 2 nM), CXCL11 (KD 16.4 nM) (see Table 1) and CCL2 (not shown), but does not bind to CCL3 (Table 1) or to the CXCR2 ligand CXCL1 and has no effect on CXCL1-mediated neutrophil transmigration (data not shown). Thus, TSG-6 binds to at least two members of each of the CC and CXC chemokine families. Soluble CKBPs are known to be produced by viruses (reviewed in (53)) and also by parasites, such as the helminth Shistosoma mansoni (54) and blood sucking ticks (55), enabling these organisms to evade the host immune response through neutralization of chemokine activities. The soluble CKBP from S. mansoni binds to various chemokines including CXCL8 and inhibits CXCL8-mediated neutrophil migration in models of inflammatory disease (54), whilst the viral CKBPs block chemokine functions through interacting with their GAG-binding and/or their receptor-binding domains (see (53,56)). Evasin-3, in the saliva of ticks, binds selectively to CXCL8 (KD ~1 nM) and suppresses the CXCL8-CXCR1 interaction; it is a potent inhibitor of neutrophil recruitment (55,57), reducing myocardial infarct size in a mouse model of ischemia/reperfusion injury and also decreases the local production of TNF in the synovial joints of mice with antigen-induced arthritis. Thus, there are many parallels between the effects of these various CKBPs and the activities of TSG-6 described here and previously, e.g. in murine models of inflammation (17), arthritis (20) and myocardial infarction (21). Although TSG-6 does not show any obvious relationship to the parasitic or viral CKBPs in either sequence or tertiary structure, there appear to be similarities in the mechanisms through which these proteins act to neutralize chemokine function; i.e. CKBPs from pathogenic organisms might mimic the activity of TSG-6.

In summary this study has identified an endogenous mechanism whereby TSG-6 might regulate neutrophil extravasation in vivo and thus prevent/limit tissue damage during acute inflammation. Our discovery of a soluble mammalian chemokine-binding protein could inform the development of new anti-inflammatory therapeutics, for diseases of unresolved inflammation (e.g. RA and cardiovascular disease) where the regulation of chemokine activity is a potential target, or indeed lead to improved methods for transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ann Canfield (University of Manchester, UK), Mark Fuster (University of California San Diego) and Bernhard Moser (University of Cardiff, UK) for providing EA.hy 926 cells, HUVECs and the 300-19 cell lines, respectively, and Barbara Mulloy (NIBSC, UK) for provision of 4th International Standard heparin.

DPD was the recipient of a BBSRC CASE Doctoral Training Award in conjunction with Merck Serono (Geneva, Switzerland). JMT is the recipient of a BBSRC CASE Doctoral Training Award in conjunction with Eden Biodesign (Liverpool, U.K.). AJD and CMM gratefully acknowledge the support of ARUK (grants 16539 and 18472).

References

- 1.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith WB, Gamble JR, Clark-Lewis I, Vadas MA. Interleukin-8 induces neutrophil transendothelial migration. Immunology. 1991;72:65–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillyer P, Mordelet E, Flynn G, Male D. Chemokines, chemokine receptors and adhesion molecules on different human endothelia: discriminating the tissue-specific functions that affect leucocyte migration. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:431–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2003.02323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lisignoli G, Toneguzzi S, Pozzi C, Piacentini A, Riccio M, Ferruzzi A, Gualtieri G, Facchini A. Proinflammatory cytokines and chemokine production and expression by human osteoblasts isolated from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:791–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuschert GS, Hoogewerf AJ, Proudfoot AE, Chung CW, Cooke RM, Hubbard RE, Wells TN, Sanderson PN. Identification of a glycosaminoglycan binding surface on human interleukin-8. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11193–11201. doi: 10.1021/bi972867o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb LM, Ehrengruber MU, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Rot A. Binding to heparan sulfate or heparin enhances neutrophil responses to interleukin 8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7158–7162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middleton J, Neil S, Wintle J, Clark-Lewis I, Moore H, Lam C, Auer M, Hub E, Rot A. Transcytosis and surface presentation of IL-8 by venular endothelial cells. Cell. 1997;91:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frevert CW, Kinsella MG, Vathanaprida C, Goodman RB, Baskin DG, Proudfoot A, Wells TN, Wight TN, Martin TR. Binding of interleukin-8 to heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate in lung tissue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:464–472. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0084OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Horuk R, Rice GC, Bennett GL, Camerato T, Wood WI. Characterization of two high affinity human interleukin-8 receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:16283–16287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das ST, Rajagopalan L, Guerrero-Plata A, Sai J, Richmond A, Garofalo RP, Rajarathnam K. Monomeric and dimeric CXCL8 are both essential for in vivo neutrophil recruitment. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Fuster M, Sriramarao P, Esko JD. Endothelial heparan sulfate deficiency impairs L-selectin- and chemokine-mediated neutrophil trafficking during inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:902–910. doi: 10.1038/ni1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colditz IG, Schneider MA, Pruenster M, Rot A. Chemokines at large: in-vivo mechanisms of their transport, presentation and clearance. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:688–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangavarapu P, Rajagopalan L, Kolli D, Guerrero-Plata A, Garofalo RP, Rajarathnam K. The monomer-dimer equilibrium and glycosaminoglycan interactions of chemokine CXCL8 regulate tissue-specific neutrophil recruitment. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2012;91:259–265. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0511239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee TH, Wisniewski HG, Vilcek J. A novel secretory tumor necrosis factor-inducible protein (TSG-6) is a member of the family of hyaluronate binding proteins, closely related to the adhesion receptor CD44. The Journal of cell biology. 1992;116:545–557. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahoney DJ, Swales C, Athanasou NA, Bombardieri M, Pitzalis C, Kliskey K, Sharif M, Day AJ, Milner CM, Sabokbar A. TSG-6 inhibits osteoclast activity via an autocrine mechanism and is functionally synergistic with osteoprotegerin. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63:1034–1043. doi: 10.1002/art.30201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagyeri G, Radacs M, Ghassemi-Nejad S, Tryniszewska B, Olasz K, Hutas G, Gyorfy Z, Hascall VC, Glant TT, Mikecz K. TSG-6 protein, a negative regulator of inflammatory arthritis, forms a ternary complex with murine mast cell tryptases and heparin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:23559–23569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Getting SJ, Mahoney DJ, Cao T, Rugg MS, Fries E, Milner CM, Perretti M, Day AJ. The link module from human TSG-6 inhibits neutrophil migration in a hyaluronan- and inter-alpha -inhibitor-independent manner. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:51068–51076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milner CM, Day AJ. TSG-6: a multifunctional protein associated with inflammation. Journal of cell science. 2003;116:1863–1873. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao TV, La M, Getting SJ, Day AJ, Perretti M. Inhibitory effects of TSG-6 Link module on leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in vitro and in vivo. Microcirculation. 2004;11:615–624. doi: 10.1080/10739680490503438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szanto S, Bardos T, Gal I, Glant TT, Mikecz K. Enhanced neutrophil extravasation and rapid progression of proteoglycan-induced arthritis in TSG-6-knockout mice. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004;50:3012–3022. doi: 10.1002/art.20655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, Semprun-Prieto L, Delafontaine P, Prockop DJ. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh JY, Roddy GW, Choi H, Lee RH, Ylostalo JH, Rosa RH, Jr., Prockop DJ. Anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6 reduces inflammatory damage to the cornea following chemical and mechanical injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16875–16880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012451107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi H, Lee RH, Bazhanov N, Oh JY, Prockop DJ. Anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6 secreted by activated MSCs attenuates zymosan-induced mouse peritonitis by decreasing TLR2/NF-kappaB signaling in resident macrophages. Blood. 2011;118:330–338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh JY, Lee RH, Yu JM, Ko JH, Lee HJ, Ko AY, Roddy GW, Prockop DJ. Intravenous Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prevented Rejection of Allogeneic Corneal Transplants by Aborting the Early Inflammatory Response. Mol Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maina V, Cotena A, Doni A, Nebuloni M, Pasqualini F, Milner CM, Day AJ, Mantovani A, Garlanda C. Coregulation in human leukocytes of the long pentraxin PTX3 and TSG-6. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2009;86:123–132. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0608345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang MY, Chan CK, Braun KR, Green PS, O’Brien KD, Chait A, Day AJ, Wight TN. Monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation: synthesis and secretion of a complex extracellular matrix. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:14122–14135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahoney DJ, Mulloy B, Forster MJ, Blundell CD, Fries E, Milner CM, Day AJ. Characterization of the interaction between tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 and heparin: implications for the inhibition of plasmin in extracellular matrix microenvironments. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:27044–27055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuznetsova SA, Day AJ, Mahoney DJ, Rugg MS, Mosher DF, Roberts DD. The N-terminal module of thrombospondin-1 interacts with the link domain of TSG-6 and enhances its covalent association with the heavy chains of inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:30899–30908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500701200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parkar AA, Day AJ. Overlapping sites on the Link module of human TSG-6 mediate binding to hyaluronan and chrondroitin-4-sulphate. FEBS letters. 1997;410:413–417. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00621-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marson A, Robinson DE, Brookes PN, Mulloy B, Wiles M, Clark SJ, Fielder HL, Collinson LJ, Cain SA, Kielty CM, McArthur S, Buttle DJ, Short RD, Whittle JD, Day AJ. Development of a microtiter plate-based glycosaminoglycan array for the investigation of glycosaminoglycan-protein interactions. Glycobiology. 2009;19:1537–1546. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nentwich HA, Mustafa Z, Rugg MS, Marsden BD, Cordell MR, Mahoney DJ, Jenkins SC, Dowling B, Fries E, Milner CM, Loughlin J, Day AJ. A novel allelic variant of the human TSG-6 gene encoding an amino acid difference in the CUB module. Chromosomal localization, frequency analysis, modeling, and expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:15354–15362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanino Y, Coombe DR, Gill SE, Kett WC, Kajikawa O, Proudfoot AE, Wells TN, Parks WC, Wight TN, Martin TR, Frevert CW. Kinetics of chemokine-glycosaminoglycan interactions control neutrophil migration into the airspaces of the lungs. J Immunol. 2010;184:2677–2685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark SJ, Higman VA, Mulloy B, Perkins SJ, Lea SM, Sim RB, Day AJ. His-384 allotypic variant of factor H associated with age-related macular degeneration has different heparin binding properties from the non-disease-associated form. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:24713–24720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacob C, Leport M, Szilagyi C, Allen JM, Bertrand C, Lagente V. DMSO-treated HL60 cells: a model of neutrophil-like cells mainly expressing PDE4B subtype. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1647–1656. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loetscher M, Gerber B, Loetscher P, Jones SA, Piali L, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. Chemokine receptor specific for IP10 and mig: structure, function, and expression in activated T-lymphocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1996;184:963–969. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proudfoot AE, Handel TM, Johnson Z, Lau EK, LiWang P, Clark-Lewis I, Borlat F, Wells TN, Kosco-Vilbois MH. Glycosaminoglycan binding and oligomerization are essential for the in vivo activity of certain chemokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1885–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334864100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pruenster M, Mudde L, Bombosi P, Dimitrova S, Zsak M, Middleton J, Richmond A, Graham GJ, Segerer S, Nibbs RJ, Rot A. The Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines transports chemokines and supports their promigratory activity. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:101–108. doi: 10.1038/ni.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen SJ, Hamel DJ, Handel TM. A rapid and efficient way to obtain modified chemokines for functional and biophysical studies. Cytokine. 2011;55:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biacore A. Information about BiaEvaluation 3.0. Biacore AB; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Shannessy DJ, Brigham-Burke M, Peck K. Immobilization chemistries suitable for use in the BIAcore surface plasmon resonance detector. Analytical biochemistry. 1992;205:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90589-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahoney DJ, Blundell CD, Day AJ. Mapping the hyaluronan-binding site on the link module from human tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 by site-directed mutagenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:22764–22771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park CJ, Gabrielson NP, Pack DW, Jamison RD, Wagoner Johnson AJ. The effect of chitosan on the migration of neutrophil-like HL60 cells, mediated by IL-8. Biomaterials. 2009;30:436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blundell CD, Mahoney DJ, Cordell MR, Almond A, Kahmann JD, Perczel A, Taylor JD, Campbell ID, Day AJ. Determining the molecular basis for the pH-dependent interaction between the link module of human TSG-6 and hyaluronan. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:12976–12988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Handel TM, Johnson Z, Crown SE, Lau EK, Proudfoot AE. Regulation of protein function by glycosaminoglycans--as exemplified by chemokines. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:385–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clore GM, Appella E, Yamada M, Matsushima K, Gronenborn AM. Three-dimensional structure of interleukin 8 in solution. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1689–1696. doi: 10.1021/bi00459a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richardson RM, Marjoram RJ, Barak LS, Snyderman R. Role of the cytoplasmic tails of CXCR1 and CXCR2 in mediating leukocyte migration, activation, and regulation. J Immunol. 2003;170:2904–2911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Middleton J, Patterson AM, Gardner L, Schmutz C, Ashton BA. Leukocyte extravasation: chemokine transport and presentation by the endothelium. Blood. 2002;100:3853–3860. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.12.3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JS, Frevert CW, Wurfel MM, Peiper SC, Wong VA, Ballman KK, Ruzinski JT, Rhim JS, Martin TR, Goodman RB. Duffy antigen facilitates movement of chemokine across the endothelium in vitro and promotes neutrophil transmigration in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;170:5244–5251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JS, Wurfel MM, Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Rosengart MR, Ranganathan M, Wong VW, Holden T, Sutlief S, Richmond A, Peiper S, Martin TR. The Duffy antigen modifies systemic and local tissue chemokine responses following lipopolysaccharide stimulation. J Immunol. 2006;177:8086–8094. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paolini JF, Willard D, Consler T, Luther M, Krangel MS. The chemokines IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and I-309 are monomers at physiologically relevant concentrations. J Immunol. 1994;153:2704–2717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baranova NS, Nileback E, Haller FM, Briggs DC, Svedhem S, Day AJ, Richter RP. The inflammation-associated protein TSG-6 cross-links hyaluronan via hyaluronan-induced TSG-6 oligomers. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:25675–25686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.247395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Citro A, Cantarelli E, Maffi P, Nano R, Melzi R, Mercalli A, Dugnani E, Sordi V, Magistretti P, Daffonchio L, Ruffini PA, Allegretti M, Secchi A, Bonifacio E, Piemonti L. CXCR1/2 inhibition enhances pancreatic islet survival after transplantation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:3647–3651. doi: 10.1172/JCI63089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alcami A. Viral mimicry of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:36–50. doi: 10.1038/nri980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith P, Fallon RE, Mangan NE, Walsh CM, Saraiva M, Sayers JR, McKenzie AN, Alcami A, Fallon PG. Schistosoma mansoni secretes a chemokine binding protein with antiinflammatory activity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:1319–1325. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deruaz M, Frauenschuh A, Alessandri AL, Dias JM, Coelho FM, Russo RC, Ferreira BR, Graham GJ, Shaw JP, Wells TN, Teixeira MM, Power CA, Proudfoot AE. Ticks produce highly selective chemokine binding proteins with antiinflammatory activity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:2019–2031. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fallon PG, Alcami A. Pathogen-derived immunomodulatory molecules: future immunotherapeutics? Trends in immunology. 2006;27:470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montecucco F, Lenglet S, Braunersreuther V, Pelli G, Pellieux C, Montessuit C, Lerch R, Deruaz M, Proudfoot AE, Mach F. Single administration of the CXC chemokine-binding protein Evasin-3 during ischemia prevents myocardial reperfusion injury in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1371–1377. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.206011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.