Summary

Dictyostelium discoideum has proven to be a useful lead genetic system for identifying novel genes and pathways responsible for the regulation of sensitivity to the widely used anti-cancer drug cisplatin. Resistance to cisplatin is a major factor limiting the efficacy of the drug in treating many types of cancer. Studies using unbiased insertional mutagenesis in D. discoideum have identified the pathway of sphingolipid metabolism as a key regulator in controlling sensitivity to cisplatin. Using the genetic tools including directed homologous recombination and ectopic gene expression available with D. discoideum has shown how pharmacological modulation of this pathway can increase sensitivity to cisplatin, and these results have been extensively translated to, and validated in, human cells. Strategies, experimental conditions and methods are presented to enable further study of resistance to cisplatin as well as other important drugs.

Keywords: sphingosine-1-phosphate, sphingosine kinase, sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase, ceramide, chemotherapy

1. Introduction

1.5 million people in the United States (approximately 15 million world wide) are diagnosed with cancer each year (1), and the majority of them will receive chemotherapy as part of their treatment. Despite major advances in the rational design of drugs for particular, genetically definable tumor types, the vast majority of chemotherapy still uses a variety of cytotoxic drugs such as cisplatin, carboplatin, doxorubicin, taxol, and etoposide. Although these drugs are often useful in reducing tumor burden, efficacy is frequently hampered by the selection for drug resistant cells in the tumors. In the case of the platinum based drug cisplatin, which is widely used for the treatment of many solid tumors, there is a vast literature describing various mechanisms of drug resistance, ranging from decreased influx or increased efflux of the drug, to inactivation of the drug, increased DNA repair, or interference with cell death pathways (2–4). Many of these studies were based on a priori assumptions of the mechanism, and they were hampered by the virtual impossibility of assigning drug resistance phenotypes to single mutations in cultured tumor cells, which have multiple mutations and a variety of chromosome alterations.

Thus, it was advantageous to have a robust model genetic system, in which isogeneic mutant strains can be established in order to link the function of single genes to drug resistant phenotypes. Dictyostelium discoideum is an excellent eukaryotic model for such a purpose (5, 6). It has a sequenced genome and many genes and pathways are highly conserved with those in human cells (7, 8). Morphologically, the cells resemble human cells, have a simple cell membrane (no cell wall), and they proliferate by mitotic division of the single cells in simple culture medium (9). The cells are haploid and this allows the facile selection of mutants, as phenotypes are immediately apparent. Moreover, well developed systems of insertional mutagenesis (REMI-Restriction Enzyme Mediated Integration) and homologous recombination are available, and allow for unbiased genome-wide screens for previously unidentified genes, as well as for targeted gene disruption of newly found putative candidates (10).

Earlier genetic studies on D. discoideum used a system of parasexual genetics which relied on mutants that were resistant to a variety of toxic drugs and chemicals for marking the chromosomes and for selection of haploid segregants (11, 12). With the advanced molecular techniques mentioned above, it is now possible to assign single genes to some of the previously studied phenotypes. For example, we examined the molecular basis for methanol resistance (acrA mutations which also confer sensitivity to acraflavin) which has been used in many studies for over 30 years, and showed that this was due to loss of function mutations in the catalase A gene (13). Therefore, there was a strong proof of principle indicating that selection for resistance could be used to investigate the underlying molecular basis of resistance to anti-cancer drugs.

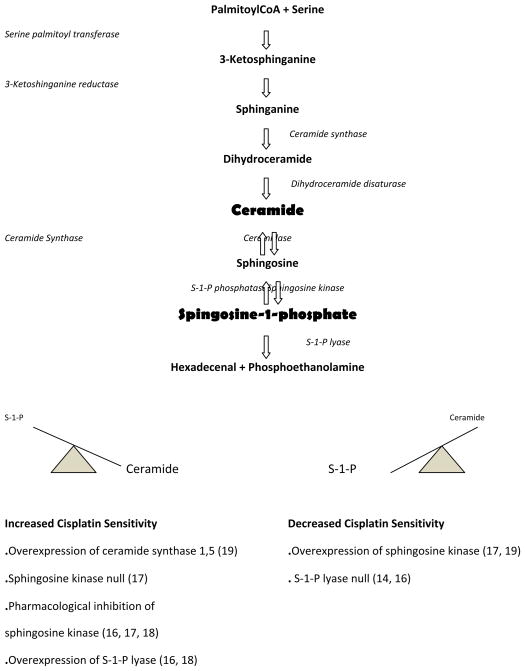

Based on these considerations we performed an unbiased screen using random insertional mutagenesis for D. discoideum mutants that were resistant to cisplatin. A number of genes involved in cisplatin resistance were identified, including the gene for sphingosine-1-phosphate (S-1-P) lyase which metabolizes S-1-P to hexadecenal and phosphoethanolamine (14). The pathway of sphingolipid metabolism is highly conserved between humans and D. discoideum (Figure 1), and the isolation of the initial mutant identified the entire pathway as potential targets for intervention to regulate sensitivity to the drug (15). We hypothesized that increased levels of S-1-P in the cells resulted in decreased sensitivity to cisplatin, which suggested that other enzymes in the pathway which regulate the levels of S-1-P should have an effect on the response to the drugs and could be targeted to improve efficacy. Therefore, we investigated the role of many of the enzymes in this pathway (S-1-P lyase, sphingosine kinase, and ceramide synthase) in the regulation of drug resistance (see Figure 1). The genetics of D. discoideum was useful in initially defining the roles of these enzymes and their cognate sphingolipid products in altering sensitivity to the drug (16, 17). Subsequently, these studies were thoroughly validated in human cells (18–23), demonstrating the power of the D. discoideum genetic system (24). The studies were also expanded to gene expression studies which identified additional genes and pathways associated with cisplatin resistance (25).

Figure 1. Pathway of sphingolipid metabolism.

Studies in D. discoideum and those subsequently validated in human cells have shown that altering the balance between ceramide and S-1-P by modulating the levels of sphingosine kinase, sphinginosine-1-phosphate lyase, or ceramide synthase has profound effects on the cytotoxic action of the anti-cancer drug cisplatin. Genetic or pharmacological (sphingosine kinase inhibitors) approaches that elevate ceramide or decrease S-1-P result in increased sensitivity to cisplatin and carboplatin. In contrast, decreasing ceramide or increasing S-1-P results in a loss of sensitivity (increased resistance) to cisplatin. Numbers in parentheses refer to published results.

This article will outline our strategies, experimental considerations and methods for isolating cisplatin resistant mutants, the identification of the affected genes and the study of the entire pathway of sphingolipid metabolism defined by these genes, thus allowing the discovery of ways to increase or decrease sensitivity to the drug.

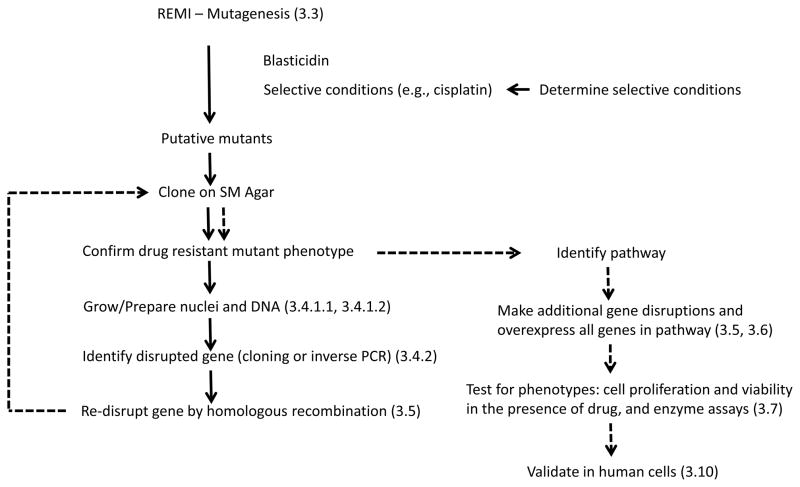

The approach described herein is easily applicable to probing the mechanism of action of any cytotoxic or cytostatic drug for example, antioxidants and botanicals with unknown function. If the drug can stop cell division or kill wild-type cells at an achievable concentration, it should be possible to isolate REMI mutant strains with decreased drug sensitivity (resistant mutants) unless the affected pathway is crucial for survival. Identification of the mutant gene is the entry point into the pathway that is regulating the response to the drug. A workflow diagram is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Workflow for identification of genes involved in drug resistance.

Workflow including references to chapter sections (in parentheses). Dotted lines indicate the second half of the procedure.

2. Materials

2.1. Chemicals

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Cisplatin (Sigma).

Normal horse serum (Sigma).

Bacto Peptone and Proteose Peptone (BD Biosciences).

LB bacterial medium (MP Biomedicals).

Antibacterial-Antimicrobial solution (penicillin G, streptomycin, amphotericin B; Gibco).

Silica gel for storage of spores (Grace Davidson).

Sphingolipids: sphingosine, S-1-P, ceramides, dimethylsphingosine (Avanti Polar Lipids). D-erythro [4,5-3H] dihydrosphingosine–1–phosphate (60 Ci/mmole; 0.1 mCi/ml; American Radiochemicals).

[γ-32P] ATP (3,000 Ci/mmole; 10 mCi/ml; New England Nuclear).

Protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma).

ATP (Sigma).

Scintillaiton liquid (Aqualume).

Triton X-100 and NP-40 (Sigma).

Glycogen (Roche Diagnostics).

Crystal Iodine (Fisher Scientific). (Fumes are produced by putting crystals in the bottom of a covered thin layer chromatography (TLC) tank).

Miscellaneous chemicals – HCl, potassium acetate, sodium acetate and NaCl (Fisher Scientific).

2.2. Buffers, solutions and growth media

All solutions are sterilized by either filtration or autoclaving.

Pt buffer to dissolve cisplatin – 3 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na-PO4, pH 7.4.

Sterile Salts (SS) solution for diluting cells for clonal plating - 0.6 g NaCl, 0.75 g KCl, 0.4 g CaCl2-2H2O per liter of H2O.

Tris-EDTA (TE buffer)– 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA.

SM broth/agar (26) for plating cells for routine maintenance and for clonally plating cells. 5x concentrated SM broth per liter – 4.75 g KH2PO4, 3.25 g K2HPO4.3H2O, 2.5 g MgSO4.7H2O, 25.0 g glucose, 25.0 g Bacto peptone, 2.5 g yeast extract, pH 6.5. The concentrated medium is made in large batches, kept frozen in 200 ml aliquots and each aliquot is diluted 5x with 800 ml H2O and autoclaved prior to use. SM plates contain 1.5% agar. 100 mm petri dishes contain 40 ml agar and 24 well plates contain 1 ml agar per well (as indicated below in 3.7.1.1. and 3.7.1.2., respectively).

HL-5 broth for cultivation of axenic strains (26). 5x concentrated HL-5 axenic medium per liter – 35 g yeast extract, 7 g proteose peptone, 2.4 g KH2PO4, 2.5 g Na2HPO4, pH 6.5. The concentrated medium is also made in large batches, kept frozen in 200 ml aliquots, and is diluted 5x with 800 ml of water and autoclaved before use. Sterile medium is stored at 4°C in the dark and can be used for well over a year. Prior to use HL5 is supplemented with 1% antibiotic/antimycotic solution and 1.3 % glucose (1:20 dilution of stock solution of 27% glucose).

Standard PBS – 10 mM Na-PO4, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl.

PBS for freezing K. aerogenes. Per liter - 0.75 g KCl, 0.58 g NaCl, 2.26 g Na2HPO4, 4.6 g KH2PO4, pH 6.5.

Blasticidin (100 mg/ml H20; Invitrogen).

NP-40 solution for preparing nuclei - 0.2% NP-40, 50 mM Tris, 25 mM KCl, 40 mM MgCl2, pH 7.6.

RNase stock – 10 mg/ml in H2O is boiled for 10 minutes to inactivate DNase; Sigma).

Tris-EDTA for suspending nuclei – 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 20 mM EDTA.

SK buffer for sphingosine kinase assays – 200 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM 4-deoxypyridoxine, 15 mM NaF, 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 40 mM glycerol phosphate, 10% glycerol, 0.007% (v/v) DTT. Before use add 1:100 protease inhibitors cocktail.

ATP mix for sphingosine kinase assays - 9 μl of 20 mM unlabeled ATP in 200 mM MgCl2, plus 1 μl (10 μCi) of (γ-32P) ATP (3,000 Ci/mmole; 10 mCi/ml).

SK-TLC (thin layer chromatography) solvent – chloroform, acetone, methanol, acetic acid water (10:4:3: 2:1- Fisher Chemicals).

S-1-P lyase assay lysis buffer - 0.25 M sucrose, 5 mM MOPS, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma).

S-1-P lyase assay reaction mixture (enough for 25 reactions) - 1 ml of 0.5 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 50 μl 0.1 M EDTA, 250 μl 0.5 M NaF, 5 μl DTT, 250 μl 5 mM pyridoxal phosphate, and 1945 μl H2O.

S-1-P lyase TLC solvent - chloroform, methanol, acetic acid (50:50:1).

2.3. Kits and supplies

BCA for protein assay (Pierce Protein Research Products).

Cell Titer Glo cell viability reagent (Promega).

Thin-layer chromatography plates (Silica Gel 60; Merck).

Opaque white 96-well plates for Luminometer (Matrix Technologies Corp.).

Corex tubes (Fisher Scientific).

Nitrogen tank.

2.4. Vectors

pBSR1 is used for REMI random insertional mutagenesis; SL63 Bsr cassette is used for directed homologous recombination; pDXA3C vector (with myc or FLAG tags) is used for ectopic gene expression with Ax3-ORF cells (16, 17, 27). All vectors are available from the Dictyostelium discoideum stock center (www.DictyBase.org).

2.5. Strains and cell lines

The parental (wild-type) axenic strain used in these studies was primarily Ax4 although Ax2 has been used, and offers the advantage that it does not have a duplication of a portion of chromosome II. Ax3-ORF (27) was used for ectopic gene expression. Mutant strains in the pathway of sphingolipid metabolism with gene disruptions or with ectopically expressed genes are listed in Table 1. All strains are available from the Dictyostelium discoideum stock center (www.DictyBase.org).

Table 1.

| STRAIN | GENOTYPE | PHENOTYPE | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ax2, Ax4 | Wild-type | Wild-type | |

| Ax3 Orf | Transacting origin of replication recognition factor | Wild-type | (16, 17, 27) |

| SA555 | [sglAΔ]bsr REMI mutant |

S-1-P lyase null; Cisplatin resistant; Blasticidin resistant | (14, 33) |

| SA554 | [sglAΔ]bsr Direct homologous recombination |

S-1-P lyase null; Cisplatin resistant; Blasticidin resistant | (14, 33) |

| SA576 | [sgkAΔ]bsr | Sphingosine kinase A null; cisplatin sensitive; Blasticidin resistant | (17) |

| SA601 | [sglA-myc]neo | S-1-P lyase over-expressor; cisplatin sensitive; neomycin resistant | (16) |

| SA602 | [sglA-myc]neo | S-1-P lyase over-expressor; cisplatin sensitive; neomycin resistant | (16) |

| SA603 | [sglA-myc]neo | S-1-P lyase over-expressor; cisplatin sensitive; neomycin resistant | (16) |

| SA604 | [sgkA-FLAG]neo | Sphingosine kinase A over- expressor; cisplatin resistant; neomycin resistant | (17) |

| HM1091 | [sgkBΔ]bsr | Sphingosine kinase B null; cisplatin sensitive; Blasticidin resistant | (17) |

| HM1093 | [sgkAΔBΔ]bsr | Sphingosine kinase A/B null; cisplatin sensitive; Blasticidin resistant | (17) |

Abbreviations: sgk, sphingosine kinase; sgl, sphingosine lyase; bsr, blasticidin resistance gene; neo, neomycin resistance gene; myc, myc fusion tag; FLAG, FLAG fusion tag; Δ, disruption in the noted gene.

The bacterial food source for D. discoideum is Klebsiella aerogenes (available at www.DictyBase.org). To insure that the bacterial inoculum is always the same, a large K. aerogenes stock is grown to stationary phase at 22°C in SM broth, harvested, washed in PBS, resupsended in 1/10 volume of bacterial storage PBS, and stored frozen in 1 ml aliquots at −80°C. The concentrated bacteria are 1.6 × 1010 cell/ml. Bacteria are thawed and diluted 3x with SM broth for use.

2.6. Equipment

Electroporator (BioRad)

Speedvac centrifuge for drying lipid extracts for thin-layer chromatography (Thermo Savant SpeedVac Concentrators).

Veritas Microplate Luminometer (Promega).

FLA 7000 Phosphorimager (Fujifilm).

PTC 100 Thermocycler (M.J. Research) or equivalent.

Automatic multi-well Pipettor (Matrix Technologies Corp.)

1680 Flatbed Scanner (Epson) or equivalent.

Water bath sonicator (Heat Systems Ultrasonics).

Scintillation Counter (Beckman Instruments) or equivalent.

3. Methods

3.1. Cell maintenance and cell cultures

Clonally derived D. discoideum strains are stored either as frozen cells in liquid nitrogen in normal horse serum containing 10% DMSO at about 5 × 107 cell/ml, or as spores, suspended in sterile 5% non-fat dried milk, mixed with silica gel, and kept desiccated at 4°C (26).

New cultures of axenic strains are started by plating either desiccated spores, or frozen cells on SM agar plates in association with K. aerogenes every 4 weeks. Cells from a cleared zone are a transferred to tubes containing 2 ml axenic liquid HL-5 medium in a test tube and are incubated without shaking at 22°C for two days. Once cells are dividing in HL-5, they are inoculated into larger volumes of HL-5 medium at 1 × 105 cells/ml and grown with shaking at 200 RPM/22°C to a density never exceeding 3–4 × 106 cell/ml (mid-log phase, where stationary phase is 1–2 × 107 cells/ml) at which point they are harvested for an experiment or passed by dilution. (See Note 1).

Growing cultures are never used for more than a month. Cultures are carefully monitored to ensure an optimal doubling time of 10–12 hours. Cultures that have a slower growth rate are not used in experiments.

3.2. Establishing selective conditions

This is the most important step in the procedure, because it is crucial for obtaining mutants and reproducibly determining sensitivity to the drug. The following procedure for cisplatin is given as an example.

3.2.1. Drug Solubility

Two factors have to be considered when testing new drugs: the solvent, and the maximum solubility of the drug. Some drugs are water soluble, while other drugs must be dissolved in DMSO. Drugs should be dissolved at a concentration that allows dilution to the working concentration and does not add more than 5% DMSO or water to the medium. Higher concentrations of the solvent dramatically affect the rate of cell growth. Cisplatin is water-soluble and has a maximum solubility of about 1 mg/ml (3.3 mM) in Pt Buffer.

3.2.2. Determining an extinction coefficient for each drug

Many mutants will have only a subtle change in sensitivity to a drug, which is why preparing precise and reproducible concentrations of the drug is critical to obtaining reproducible results. (See Note 2).

The first step to ensure accurate and consistent drug concentrations is to determine the extinction coefficient using Beers Law (Absorbance λ = ε/mM/cm) by analyzing the absorbance spectrum of a known concentration of the drug and identifying the maximum wavelength of absorption. It is advised to establish an extinction coefficient by measuring the absorbance at that wavelength for a number of drug concentrations.

In the case of cisplatin we established the extinction coefficient (ε) as A220 nm = 1.957/mM/cm. We routinely made a cisplatin stock solution of 1 mg/ml (3.3 mM), which was 11x the highest concentration desired for experiments, such that adding 1 ml to 10 ml culture resulted in 1x concentration (300 μg/ml). For 150 μg/ml, and 75 μg/ml, dilute 0.5 ml or 0.25 ml cisplatin to 10 ml cultures, respectively, and bring the volume up to 11 ml with Pt buffer (See Note 3).

Weigh desired amount of cisplatin. (See Note 4).

Add 90–95% of final volume of Pt buffer, but note exactly how much was added. (See Note 5).

Vortex well, and shake for a while at 37°C. (At this concentration cisplatin does not go into solution easily).

Make a dilution of 1:10 in PT buffer, and determine A220. (Record the exact volume you removed for the dilution, and how much is left).

Multiply the absorbance by 10, to account for the above dilution.

To get the current concentration of your solution, divide by 1.957 (the extinction coefficient).

Divide the concentration you got by 3.3. This will tell you how much more concentrated your solution is than the desired 3.3 mM.

- To get the final volume, multiply the original volume (from step 4) by the factor you got (from step 7), and add enough Pt buffer to your solution to reach the final volume. See following equation that summarizes steps 5–8.

3.2.3. Selection

Selection in the presence of drugs can be done either in liquid in petri dishes, or on SM agar plates in association with K. aerogenes. The primary criteria are availability and cost of the drug, and if it is metabolized by the K. aerogenes. We selected for cisplatin resistant mutants in liquid due to cost, but have effectively isolated methanol and acraflavin resistant mutants on SM agar plates. (See Note 6).

3.3. Random Insertional mutagenesis and selection of mutant strains

Detailed protocols for REMI mutagenesis have been described previously (28, 29) and our methods are identical. We electroporate 1 × 107 cells and allow them to recover for 24 hours at 22°C in 10 ml HL-5 medium in 100 mm petri dishes before adding blasticidin to a concentration of 10 μg/ml. We suggest that cisplatin, or any other drug which is being used for selection of resistant mutants, should be added by two days post-electroporation, before blasticidin resistant colonies are visible, so as not to allow time to accumulate secondary spontaneous mutations that are not due to the REMI mutagenesis. Putative mutants that grow as colonies in selective media are picked and are plated at low density for clonal colonies on SM agar plates. Cells from a single clone are re-tested for drug resistance in HL-5 medium containing the drug with parental wild-type cells used as a control. New clonally derived mutant strains are given names and stored by freezing or desiccation on silica gel.

3.4 Identifying REMI insertions

Once a new mutant is isolated and retested, it is grown up for genomic DNA isolation in order to identify REMI insertion sites. Although there are methods that claim to be faster, we always prepare DNA from isolated nuclei, because this results in very pure DNA that is exclusively genomic. Overall, this step saves time and frustration. (See Note 7).

3.4.1. Preparation of genomic DNA

3.4.1.1 Preparation of Nuclei (See Note 8)

Grow 100–500 ml of cells in axenic medium to 1.5 – 2.0 × 107 cells/ml, pellet, wash with cold, sterile water and then with cold, sterile 0.2% NaCl.

Resuspend cells to 1 × 109 cells/30 ml with cold, sterile SS, add 13 ml 0.2% NP-40 solution and vortex 40–60 sec.

Incubate on ice for 2–3 minutes, spin at 400 × g for 5 minutes and transfer supernatant to sterile 30 ml Corex tubes (3 tubes for each 1 × 109 cells).

Centrifuge at 3500 x g for 10 minutes to pellet nuclei and carefully discard supernatant.

Repeat steps 2–3 on the pellets of un-lysed cells from step 3. If the pellets from step 3 are still fairly big, repeat steps 2–3 a third time.

Combine all nuclear pellets from step 4 in 10–20 ml SS and pellet for 10 minutes at 3700 x g.

Carefully discard supernatant and resuspend the nuclei in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 20 mM EDTA at 5 × 108 nuclei/ml (2 ml/109 cells from original count). Nuclei can be frozen at −80°C at this point.

3.4.1.2. DNA purification

Add 20% SDS to 1/20th the volume of Tris/EDTA nuclear suspension and swirl to mix (solution should become clear, with bubbles trapped by the DNA). Incubate for 30 minutes at 65 °C.

Slowly add 1/3 volume 5 M potassium acetate by dripping it into the lysed nuclei and swirling gently to mix. A white precipitate should form. Incubate for 60 minutes on ice.

Pellet the precipitate at 12,000 x g for 10 min. Transfer the supernatant to fresh Corex tubes and re-centrifuge another 10–15 min. Transfer the supernatant again to fresh Corex tubes.

Add 2.1 volumes of 100% ethanol and 2 μl 10 mg/ml glycogen to supernatant and mix gently. Precipitate the DNA at −20°C.

Pellet DNA in Corex tubes at 12,000 x g for 15 min. Discard ethanol, drain briefly and wash in 70% ethanol. Drain again and air dry inverted at 37°C for 15 minutes or until completely dry.

Dissolve pellets in TE, pH 8.0 (as much as 2–3 ml may be needed to dissolve everything).

Aliquot the preparation to microfuge tubes at 0.5 ml/tube using 1 ml pipet tips with ~5 mm cut off the ends with a sterile razor blade to prevent shearing DNA.

Digest samples at 37°C for 40 minutes with DNase-free RNase A at a final concentration of 0.02 mg/ml.

Extract the sample with an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), back extract the phenol phase with 100–500 μl TE, pH 8.0 and combine aqueous phases.

Add 1/10th volume 3 M sodium acetate pH 5.0, 2.1 volumes 100% ethanol and 2 μl 10 mg/ml glycogen. Mix gently. DNA should begin to precipitate immediately. Continue precipitating at −20°C for at least 30 minutes. Spin at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes, discard supernatant, and wash with 70% ethanol. Re-centrifuge for 10 minute, drain and dry the pellets as above.

Dissolve pellet in 200–400 μl TE, pH 8.0 and Store DNA at −20°C.

3.4.2. Identifying the mutated gene

To identify the mutated gene from the REMI mutagenesis, we use either inverse PCR, or clone a restriction enzyme fragment that contains the REMI insertion.

3.4.2.1. Inverse PCR

This method (30) takes advantage of the high frequency of AluI restriction sites in D. discoideum DNA, and offers a sophisticated method to identify the site of REMI insertion. In our hands this method works for about 50% of the mutants. This method has been described in detail (29). Our only alteration, which is crucial for the use of the pBsr1 REMI vector (4189 bp), is to use the following two oligonucleotide primers for the PCR amplification and sequencing - Oligonucleotide 339 - 5′ GAT GCT ACA CAA TTA GGC 3′ (position 4107 – 4124); Oligonucleotide 347 - 5′ ATG CCG CAT AGT TAA GCC AG 3′ (position 3638 – 3657). These primers lie between an AluI site at position 3565 and the single BamHI site at position 28. Start the procedure with 20 μg of genomic DNA to ensure that you have enough material to complete the process. We always recover enough PCR product to sequence.

3.4.2.2 Cloning of restriction fragment

This method is exactly as previously described (28). We digest genomic DNA with several enzymes (e.g., EcoRI, ClaI, BglII), ligate the fragments into PUC18 and electroporate into electrocompetent DH5α E. coli. Transfectants carrying the REMI insertions are selected on LB plates containing ampicillin.

3.5. Homologous recombination to reconfirm REMI mutation or to delete other genes of interest

Reconfirmation of the phenotype of the original REMI insertion is routinely done to ensure that drug resistance is not due to some secondary mutational event. This procedure has been described previously (28, 29). Clearly, the precise DNA constructs depend on the gene in question. The molecular constructs for directly disrupting the D. discoideum S-1-P lyase and sphiningosine kinases by homologous recombination have been described in detail (16, 17). The double gene disruptions of the sphingosine kinase A and B genes used cre-lox technology previously described (31). Homologous recombination is confirmed by standard PCR, Southern, and Western analyses.

3.6. Overexpression of genes

In addition to homologous recombination, ectopic expression of genes has been extremely useful in demonstrating the roles of the sphingosine kinases and S-1-P lyase in regulating sensitivity to cisplatin and other chemotherapeutic drugs (16, 17). Previous studies have employed the frequently used D. discoideum AX3 ORF cell/pDXA3C vector system where the gene under study is fused with either the myc or FLAG epitope tags (27). There are now a variety of additional vectors that are designed for ectopic expression with a larger variety of tags and expression levels (32).

3.7 Phenotypic characterization

Phenotypic characterizations relevant to studies of drug resistance/sensitivity include viability and cell growth assays, and assays of the enzymes which have been implicated in being involved in the change in resistance or sensitivity.

Some mutant strains (e.g., sphingosine lyase null cells) have obvious developmental defects and have been shown to have defects in cell motility, slug migration, developmental timing and spore formation using standard cell and molecular biology techniques (33). Note, that studies on mood altering drugs used altered developmental phenotype of wild-type cells in the presence of the drug as the screen for resistance (i.e., the mutants had normal development) (34).

3.7.1. Viability studies

Accurate measurement of viability after drug treatment is critical to these studies. Cells are exposed to drugs at either a constant drug concentration for different lengths of time, or different drug concentrations at one time point, and subsequently tested for viability. A number of complementary assays are available and all have a large range of sensitivity (dynamic range).

3.7.1.1 Clonal plating (see (26)

Suspend clonally derived parent and mutant D. discoideum cells in SS buffer, count in a hemocytometer, and adjust to 1 × 106 cells/ml.

Serial dilutions are made by sequentially transferring 0.1 ml of well-vortexed cells to a tube containing 0.9 ml of SS buffer. Dilution tubes are prepared by using an automatic repeat pipettor.

0.1 ml of the dilutions predicted to contain 1000, 100, and 10 cells are plated in triplicate with 0.2 ml of diluted K. aerogenes on 100 mm SM agar plates containing 40 ml per plate. (See Note 9).

Clonal colonies (plaques) are counted starting on day 3 when they are first visible. Colony number should be linear with dilution.

Results from the triplicate plates are averaged, and viability is calculated as the percentage of the untreated control cultures. Percent survival of parent and mutant strains are then compared.

3.7.1.2. Rapid clonal plating using 24-well plates

This assay is more rapid and uses drastically less agar and plasticware that the conventional clonal plating assay (35).

-

1

Prepare 24 well plates with 1 ml SM agar per well. (See Note 10).

-

2

Place 200 μl SS per well in a 96 well dilution plate with an automatic multi-channel pipettor.

-

3

Add 100 μl of each cell culture to be assayed into the wells in the top row (A) of plate (in duplicate).

-

4

Using a Matrix multi-well automatic pipettor perform a series of 3-fold serial dilutions down the plate to row H. (Set the pipettor as follows: Fill 200 μl, Mix 10x, Fill 100 μl, Dispense into next well). (See Note 11).

-

5

Place 20 μl of diluted K. aerogenes per well of 24 well plate containing the SM agar.

-

6

Plate dilutions (from step # 4) onto 24-well plates containing SM agar and K. aerogenes promptly as follows. (See Note 12).

Add 15 μl of the last 6 dilutions of each sample (wells C-H) on to the drop of K. aerogenes in a separate well of the 24-well plate with the SM agar. Each column (wells C – H) is plated as a single row (1–6) on the 24-well plate using a multi-channel automatic pipettor. (Set pipettor as follows: - Fill 45 μl, mix, dispense 15 μl.) Discard the first 15 μl back into the 96 well plate to avoid bubbles in the dispensing. Then pull the lever to fit the 24-well plate format and dispense 15 μl onto the K. aerogenes in the 24-well plate). (See Note 13).

-

7

Shake the plate gently by hand 10–12 times (with round motion, to make sure the drop covers the well) and let dry at room temperature on a level surface for a few hours before placing at 22°C upside down.

-

8

When plaques appear, scan the 24-well plate upside down on a flatbed scanner twice each day, until no new plaques appear. Save scans as JPEG files.

-

10

Count plaques on printouts of the scan and average the counts at each dilution. Viability is calculated as percentage of the untreated controls. Survival of the mutant and parental strains are then compared.

-

10

3.7.1.3. Luminescence based assay

This assay measures the amount of ATP in living cells and is therefore a sensitive measurement of the number of living cells in a culture (36).

A logarithmically growing culture of D. discoideum cells (2 × 106 cell/ml) is diluted to 5 × 105 cell/ml and aliquoted into triplicate flasks for each time point or drug concentration. These experimental cultures are shaken for an additional 1–2 hours prior to the addition of the drug to ensure they are growing well. (See Note 14).

Cisplatin is added to the desired concentration and shaking is continued for the desired length of time. An equivalent amount of Pt buffer is added to parallel cultures as a solvent control.

The triplicate cultures are sampled at the desired time point and diluted 1 to 5 in SS. 100 μl of each dilution is placed in a well of a 96 well opaque white plate so that there are 10,000 cells/well. The assay is linear between 200 and 20,000 cells/well.

Add 100 μl of freshly mixed Promega Cell Titer Glo solution and incubate the plate for a standard amount of time (e.g., 30 minutes) at 22°C and read the plate in a multi-well plate luminometer.

Luminometer readings of the triplicates are averaged, compared to controls lacking drugs and expressed as percent. Mutant survival is then compared to that of wild-type controls.

3.7.2. Enzyme assays for sphingolipid metabolizing enzymes

3.7.2.1 Sphingosine kinase assay (see (17))

Collect 1 × 108 D. discoideum cells, spin, freeze pellet. Frozen pellets are lysed in 500 μl of SK buffer with 0.2 M KCL followed by freezing and thawing 6x and centrifugation at 150,000 x g for 30 min.

Supernatant protein concentration is determined by BCA assay.

50 to 150 μg of protein extract is brought to 180 μl with SK buffer containing either 0.2 M (for sphingosine kinase A) or 1.0 M KCl (for sphingosine kinase B) incubated with 10 μl of 1 mM sphingosine (dissolved in 5% Triton X-110) and 10 μl of ATP mix for 90 minutes at 28° C. (See Note 15).

The reaction is terminated with 20 μl of 1 N HCl and 800 μl of chloroform-methanol-HCl (50:100:1) for ten minutes at room temperature.

250 μl chloroform and 250 μl of 2 M KCl are added and mixed and the phases are separated by centrifugation.

The top aqueous layer is aspirated, and 100 μl of the organic phase is spotted on thin-layer chromatography plates developed in SK-TLC solvent and visualized on a phosphorimager. Authentic sphingosine-1-phosphate is run as a marker.

Radioactive spots containing the reaction product are scraped from the plates and quantitated with a scintillation counter. One unit of enzyme activity is defined as picomoles of S-1-P generated/minute/mg protein. Using this lot of radioisotope, 1 picomole of product was 122 dpm.

3.7.2.2 S-1-P lyase assay (see (37))

1 × 108 D. discoideum cells are harvested in cold S-1-P lyase lysis buffer.

Pellets were lysed in 80 μl lysis buffer, 0.5% Triton X-100, and diluted to 0.1 % Triton X-100 with lysis buffer. Protein concentration is determined using the BCA protein assay.

For 25 reactions, 200 μl of unlabeled 1 mM dihydrosphingosine-1-phosphate is mixed with 1 x 107 dpm (~ 72 μl) of D-erythro [4,5-3H] dihydrosphingosine–1–phosphate (60 Ci/mmole; 0.1 mCi/ml). This substrate is dried under a stream of nitrogen and redissolved in 500 μl 1% Triton X-100. The complete reaction mixture is made by adding 3.5 ml of S-1-P lyase reaction mixture (enough for 25 reactions). Warm to 37°C and sonicate in a water bath sonicator to ensure complete mixing.

40 μl of protein extract is pipetted into 5 ml screw capped glass tubes.

160 μl of reaction mixture is added to each sample and incubated at 37°C shaking in a water bath for 1 hour.

Stop reaction with 0.2 ml of HClO4 and 1.5 ml chloroform and vortex well.

Add an additional 0.5 ml chloroform and O.5 ml HClO4, vortex and separate phases by centrifugation at low speed. Remove upper phase and wash lower phase with 1 ml HClO4/methanol.

Transfer a set volume of lower phase to a clean tube and dry in a Speedvac centrifuge. Dissolve in 50 μl CHCl3/methanol (8/2) with the unlabeled reaction product hexadecenal as a marker.

Spot 20 μl on TLC plates and develop in S-1-P lyase TLC solvent. The hexadecenal product (and further products hexadecenol, and palmitic acid) run close to the front. The products are visualized by exposure to iodine fumes. (See Note 16).

Based on the position of the markers, scrape the areas of the TLC plates with the reaction products, and suspend the silica in 0.5 ml of 1% SDS and 5 ml of scintillation fluid, and count in a scintillation counter.

Activity is expressed as pmole/minute/mg protein. Using this lot of radioisotope, 1 picomole of product was 50 dpm.

3.8. Genes of unknown function

REMI mutants are often found to be in genes of unknown function. These genes can have clear human homologs, or can be “Dictyocentric” (24), i.e., only found in D. discoideum. In either case, identification of the gene provides an opportunity to determine the function of the novel gene, beyond its association with drug resistance. Further investigation, including determining expression patterns during cell growth and development, subcellular distribution studies using tagged ectopically expressed proteins or specific antibodies, and careful interrogation of the protein domains can lead to a mechanistic functional understanding of the gene and its cognate protein. This is a valuable goal in the post genomic era.

3.9. Translation to human cells

In some cases, such as the S-1-P lyase, the gene has a clear homolog in humans. Indeed, the entire pathway of sphingolipid metabolism was found to be conserved between D. discoideum and humans (15). In these cases it is important to translate the results to human cells. We have done this extensively in a number of human cell types to show that modulating the levels of sphingosine kinase, S-1-P lyase and ceramide synthase results in predictable and profound changes in sensitivity to cisplatin (18–21).

These studies validate the utility of D. discoideum genetics to identify novel genes of interest and to do initial interrogations of the gene pathways. However, it is also clear that while the overall results found in D. discoideum were validated in human cells, there were differences in some of the details. For example, in D. discoideum, altering the levels of sphingosine kinase or S-1-P lyase only affected sensitivity to the platinum based drugs cisplatin and carboplatin, which have identical underlying mechanisms of action, and had no effect on several other drugs tested (16, 17). In contrast, modulation of these enzymes in human cells affected sensitivity to some drugs in addition to cisplatin and carboplatin (18, 19).

Another point to consider is the considerable redundancy that exists in the genomes higher organisms. Often there are multiple enzymes performing the same function, and multiple pathways leading to the same outcome. Thus, inactivating single genes might have different effect in the different systems. An example from the pathway of sphingolipid metabolism we studied is the enzyme ceramide synthase. The D. discoideum genome has only one enzyme (15), while mammalian cells have 6 enzymes, each encoded by a different gene, with different substrate specificity and different tissue distribution. Deletion of the individual mammalian genes leads to specific phenotypes (38, 39), while a deletion of the single ceramide synthase in D. discoideum would be predicted to be lethal. To this end, the conservation of function, and the similarities in the response to drug between human cells and D. discoideum cells is even more remarkable.

Acknowledgments

Work done in the authors’ laboratory was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM53929) and the University of Missouri Research Board (CB000359).

Footnotes

The flask size is always about 5 times the volume of medium to ensure adequate aeration for logarithmic growth with a doubling time of 10–12 hours.

We always use a freshly made solution of cisplatin, and all other drugs we have used.

For reasons that are not clear, higher concentrations of drugs are often needed to kill D. discoideum cells than human cells. We performed our experiments at 75, 150 and 300 μM cisplatin while experiments in human cells often use concentrations about 10-fold less (see references (16–19)).

Wear gloves and breathing protection throughout the procedure. Culture supernatants, and disposable plastic ware should be discarded as hazardous waste.

Thiols inactivate cisplatin. Avoid DMSO as a solvent, even though there is abundant literature on using cisplatin in DMSO.

Using either method, there must be a strong selection where there is virtually no cell growth of the wild-type parent strain in the presence of drug (less than 1 in 1 × 105 inoculated cells).

Theoretically it would be good to establish complementarity of the new mutants before identification of the REMI insertion sites to avoid the effort of cloning duplicate gene disruptions. A method for parasexual genetics for axenic strains has been developed (40, 41), but requires that each mutagenesis is done in a different genetic background and therefore does not allow complementation of mutants from a single mutagenesis. We have identified multiple – non sister - insertions within a single gene from independent mutagenesis, and this generally supports the importance of the gene in question with regard to the type of drug resistance.

Nuclei prepared this way are transcriptionally active and can be used for run-on transcription assays, although they have to be stored in a different buffer.

To obtain reproducible and comparable results it is important to use identical bacterial inocula (see 2.5).

Make sure the plates are very even (pour on a perfectly level surface). We have large sheets of thick glass leveled on our laboratory benches for this purpose. Before use, dry the plate open, upside down, for 30 minutes at 37°C. After inoculating the plates they are allowed to dry on these level surfaces as well.

If you do not have an automatic pipettor, use 50 μl into 100 μl (50 μl into a total of 150 μl, or 1:3), and mix up and down 10 times manually.

If this step is not done promptly, the cells can stick to the bottoms of the 96-well plates resulting in aberrantly low cell counts.

If you do not have an automatic pipettor, dispense by hand 15 μl into the drop of K. aerogenes. If you want to use the same tips throughout, start from the highest dilution.

Care must be taken when diluting cells for these experiments as we have found that considerable error can occur here. Large volumes of diluted cells should be made and aliquoted to the replicate experimental flasks.

The two sphingosine kinase enzymes in both D. discoideum and human cells have different KCl sensitivities that can be used to distinguish them. The D. discoideum sphingosine kinase B and human sphingosine kinase 2 enzymes are both activated to a much greater extent by 1 M KCl than are the D. discoideum sphingosine kinase A and human sphingosine kinase 1 enzymes.

The most prominent band is Triton X-100.

References

- 1.AmericanCancerSociety. Cancer Facts and Figures 2010. 2010 http://www.cancer.org/Research/CancerFactsFigures/index.

- 2.Siddik ZH. Cisplatin: mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7265–7279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabik CA, Dolan ME. Molecular mechanisms of resistance and toxicity associated with platinating agents. Cancer treatment reviews. 2007;33:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wernyj RP, Morin PJ. Molecular mechanisms of platinum resistance: still searching for the Achilles’ heel. Drug resistance updates : reviews and commentaries in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy. 2004;7:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams JG. Dictyostelium finds new roles to model. Genetics. 2010;185:717–726. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.119297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams RS, Boeckeler K, Graf R, Muller-Taubenberger A, Li Z, Isberg RR, Wessels D, Soll DR, Alexander H, Alexander S. Towards a molecular understanding of human diseases using Dictyostelium discoideum. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glockner G, Eichinger L, Szafranski K, Pachebat JA, Bankier AT, Dear PH, Lehmann D, Baumgart C, Parra G, Abril JF, Guigo R, Kumpf K, Tunggal B, Cox E, Quail MA, Platzer M, Rosenthal A, Noegel AA. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 2 of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2002;418:79–85. doi: 10.1038/nature00847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichinger L, Pachebat JA, Glockner G, Rajandream MA, Sucgang R, Berriman M, Song J, Olsen R, Szafranski K, Xu Q, Tunggal B, Kummerfeld S, Madera M, Konfortov BA, Rivero F, Bankier AT, Lehmann R, Hamlin N, Davies R, Gaudet P, Fey P, Pilcher K, Chen G, Saunders D, Sodergren E, Davis P, Kerhornou A, Nie X, Hall N, Anjard C, Hemphill L, Bason N, Farbrother P, Desany B, Just E, Morio T, Rost R, Churcher C, Cooper J, Haydock S, van Driessche N, Cronin A, Goodhead I, Muzny D, Mourier T, Pain A, Lu M, Harper D, Lindsay R, Hauser H, James K, Quiles M, Madan Babu M, Saito T, Buchrieser C, Wardroper A, Felder M, Thangavelu M, Johnson D, Knights A, Loulseged H, Mungall K, Oliver K, Price C, Quail MA, Urushihara H, Hernandez J, Rabbinowitsch E, Steffen D, Sanders M, Ma J, Kohara Y, Sharp S, Simmonds M, Spiegler S, Tivey A, Sugano S, White B, Walker D, Woodward J, Winckler T, Tanaka Y, Shaulsky G, Schleicher M, Weinstock G, Rosenthal A, Cox EC, Chisholm RL, Gibbs R, Loomis WF, Platzer M, Kay RR, Williams J, Dear PH, Noegel AA, Barrell B, Kuspa A. The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2005;435:43–57. doi: 10.1038/nature03481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessin RH. Dictyostelium - Evolution, cell biology, and the development of multicellularity. Cambridge Univ. Press; Cambridge: 2001. p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuspa A, Loomis WF. Tagging developmental genes in Dictyostelium by restriction enzyme-mediated integration of plasmid DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8803–8807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loomis WF. Genetic tools for Dictyostelium discoideum. Methods Cell Biol. 1987;28:31–65. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61636-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newell PC. Genetics. In: Loomis WF, editor. The development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Ac. Press; New York: 1982. pp. 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia MXU, Roberts C, Alexander H, Stewart AM, Harwood A, Alexander S, Insall RH. Methanol and acriflavine resistance in Dictyostelium are caused by loss of catalase. Microbiol UK. 2002;148:333–340. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li GC, Alexander H, Schneider N, Alexander S. Molecular basis for resistance to the anticancer drug cisplatin in Dictyostelium. Microbiology. 2000;146:2219–2227. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-9-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander S, Min J, Alexander H. Dictyostelium discoideum to human cells: Pharmacogenetic studies demonstrate a role for sphingolipids in chemoresistance. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subs. 2006;1760:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min J, Stegner A, Alexander H, Alexander S. Overexpression of sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase or inhibition of sphingosine kinase in Dictyostelium discoideum results in a selective increase in sensitivity to platinum based chemotherapy drugs. Eukaryotic Cell. 2004;3:795–805. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.3.795-805.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min J, Traynor D, Stegner AL, Zhang L, Hanigan MH, Alexander H, Alexander S. Sphingosine kinase regulates the sensitivity of Dictyostelium discoideum cells to the anticancer drug cisplatin. Eukaryotic Cell. 2005;4:178–189. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.1.178-189.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Min J, Van Veldhoven PP, Zhang L, Hanigan MH, Alexander H, Alexander S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase regulates sensitivity of human cells to select chemotherapy drugs in a p38-dependent manner. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:287–296. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-04-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min J, Mesika A, Sivaguru M, Van Veldhoven PP, Alexander H, Futerman AH, Alexander S. (Dihydro)ceramide Synthase 1 Regulated Sensitivity to Cisplatin Is Associated with the Activation of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Is Abrogated by Sphingosine Kinase 1. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:801–812. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sridevi P, Alexander H, Laviad EL, Min J, Mesika A, Hannink M, Futerman AH, Alexander S. Stress-induced ER to Golgi translocation of ceramide synthase 1 is dependent on proteasomal processing. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sridevi P, Alexander H, Laviad EL, Pewzner-Jung Y, Hannink M, Futerman AH, Alexander S. Ceramide synthase 1 is regulated by proteasomal mediated turnover. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1218–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oskouian B, Sooriyakumaran P, Borowsky AD, Crans A, Dillard-Telm L, Tam YY, Bandhuvula P, Saba JD. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase potentiates apoptosis via p53- and p38-dependent pathways and is down-regulated in colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17384–17389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiss U, Oskouian B, Zhou J, Gupta V, Sooriyakumaran P, Kelly S, Wang E, Merrill AH, Jr, Saba JD. Sphingosine-phosphate lyase enhances stress-induced ceramide generation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1281–1290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander S, Alexander H. Lead genetic studies in Dictyostelium discoideum and translational studies in human cells demonstrate that sphingolipids are key regulators of sensitivity to cisplatin and other anticancer drugs. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2011;22:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Driessche N, Alexander H, Min J, Kuspa A, Alexander S, Shaulsky G. Global transcriptional responses to cisplatin in Dictyostelium discoideum identify potential drug targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15406–15411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705996104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sussman M. Cultivation and synchronous morphogenesis of Dictyostelium under controlled experimental conditions. Methods Cell Biol. 1987;28:9–29. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61635-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manstein DJ, Schuster HP, Morandini P, Hunt DM. Cloning vectors for the production of proteins in Dictyostelium discoideum. Gene. 1995;162:129–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuspa WFLaA., editor. Dictyostelium Genomics. Horizon Bioscience; Norfolk, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adley KE, Keim M, Williams RS. Pharmacogenetics: defining the genetic basis of drug action and inositol trisphosphate analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;346:517–534. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-144-4:517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keim M, Williams RS, Harwood AJ. An inverse PCR technique to rapidly isolate the flanking DNA of Dictyostelium insertion mutants. Molecular biotechnology. 2004;26:221–224. doi: 10.1385/MB:26:3:221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faix J, Kreppel L, Shaulsky G, Schleicher M, Kimmel AR. A rapid and efficient method to generate multiple gene disruptions in Dictyostelium discoideum using a single selectable marker and the Cre-loxP system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e143. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubin M, Nellen W. A versatile set of tagged expression vectors to monitor protein localisation and function in Dictyostelium. Gene. 2010;465:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li G, Foote C, Alexander S, Alexander H. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase has a central role in the development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Development. 2001;128:3473–3483. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams RS. Pharmacogenetics in model systems: Defining a common mechanism of action for mood stabilisers. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander H, Vomund AN, Alexander S. Viability assay for Dictyostelium for use in drug studies. BioTechniques. 2003;35:464–470. doi: 10.2144/03353bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Min J, Sridevi P, Alexander S, Alexander H. Sensitive cell viability assay for use in drug screens and for studying the mechanism of action of drugs in Dictyostelium discoideum. BioTechniques. 2006;41:591–595. doi: 10.2144/000112260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Veldhoven V. Aphingosine-1-phosphate lyase. Methods in Enzymology. 1999;311:244–254. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)11087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pewzner-Jung Y, Brenner O, Braun S, Laviad EL, Ben-Dor S, Feldmesser E, Horn-Saban S, Amann-Zalcenstein D, Raanan C, Berkutzki T, Erez-Roman R, Ben-David O, Levy M, Holzman D, Park H, Nyska A, Merrill AH, Jr, Futerman AH. A critical role for ceramide synthase 2 in liver homeostasis: II. insights into molecular changes leading to hepatopathy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:10911–10923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pewzner-Jung Y, Park H, Laviad EL, Silva LC, Lahiri S, Stiban J, Erez-Roman R, Brugger B, Sachsenheimer T, Wieland F, Prieto M, Merrill AH, Jr, Futerman AH. A critical role for ceramide synthase 2 in liver homeostasis: I. alterations in lipid metabolic pathways. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:10902–10910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King J, Insall R. Parasexual genetics using axenic cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;346:125–135. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-144-4:125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.King J, Insall RH. Parasexual genetics of Dictyostelium gene disruptions: identification of a ras pathway using diploids. BMC genetics. 2003;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]