Abstract

Background:

Obesity is a chronic inflammatory condition that has been associated to a risk factor for the development of periodontitis and cardiovascular disease; however, the relationship still needs to be clarified. The objective of this study was to evaluate the cardiovascular risk in obese patients with chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 87 obese patients were evaluated for anthropometric data (body mass index [BMI], waist circumference, body fat), systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, glycemia and periodontal parameters (visible plaque index (VPI), gingival bleeding index (GBI), bleeding on probing (BOP), periodontal probing depth (PPD) and clinical attachment level (CAL)).

Results:

Patients were divided into two groups according to the periodontal characteristics found: Group O-PD: Obese patients with chronic periodontitis (n = 45), 22 men and 23 women; and Group O-sPD: Obese patients without chronic periodontitis (n = 42), 17 men and 25 women. Patients had a BMI mean of 35.2 (±5.1) kg/m2 . Group O-PD showed a similarity between the genders regarding age, SBP, DBP, cholesterol, HDL, GBI, VPI, PPD ≥4 mm and CAL ≥4 mm. O-PD women showed greater glycemia level and smoking occurrence, but O-PD men presented a 13% - risk over of developing coronary artery disease in 10 years than O-PD women, 9% - risk over than O-sPD men and 15% - risk over than O-sPD women, by the Framingham Score.

Conclusions:

It was concluded that obesity and periodontal disease are cardiovascular risk factors and that the two associated inflammatory conditions potentially increases the risk for heart diseases.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, obesity, periodontal disease

INTRODUCTION

Now-a-days, obesity has been considered a major public health problem.[1] Grossi and Genco[2] and Kopelman,[3] verified that the fat located in the abdominal area is a significant risk factor for several chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, several types of cancer, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases (CVD), such as atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease and periodontal disease.[4,5]

According to the World Health Organization,[6] obesity is a condition characterized by abnormal or excessive accumulation body fat (BF), in which the individual's health may be affected.[7] Currently, the overweight and obesity has been considered as one of the most common nutritional disorders in the American Continent.[3]

The mechanism by which the adipose tissue predisposes to further development of these diseases has not yet well-understood. However, it has been proposed that obesity is associated with the immunological changes and systemic inflammatory.[8] A pro-inflammatory state can be found in obese patients due to the production of tumor necrosis factor-α, leptin and interleukin-1 by adipocytes.[9] Eckel et al.[10] and Haslam and James,[11] suggested that the intense secretion of fatty acids, cytokines and hormones derived from the adipose tissue, alter the hepatic metabolism, thereby causing, abnormal lipoprotein synthesis, hepatic insulin resistance and increased gluconeogenesis. Thus, obesity, insulin resistance and the type 2 diabetes mellitus are strongly associated with the chronic inflammation characterized by abnormal production of inflammatory mediators.[12] Considering the adipose tissue as a reservoir of inflammatory cytokines, we hypothesized that the BF would increase the probability of a host inflammatory response in periodontitis cases.

Studies have shown that patients with periodontal disease share many of the same risk factors to patients with cardiovascular disease including age, sex, obesity and lower socio-economic level, stress and smoking.[13,14] In addition, a large proportion of patients with periodontal disease also present the cardiovascular disease.[15] These observations suggested that periodontal disease and atherosclerosis share similar and common etiological pathways.[16]

The relation between periodontal disease and systemic pathologies has been the focus of many scientific studies and currently, researches have shown that obesity, in addition to being a public health problem, is also an indicator of risk for the onset and progression of periodontitis.[17,18,19,20]

A causal hypothesis of the association of periodontal and cardiovascular disease is the participation of the periodontitis in the pathogenesis of the atheroma formation.[14] The authors found a higher prevalence of plaque in the carotid artery of patients with dental losses arising from severe periodontitis.

In an epidemiological study, Dickson and Gotlieb[21] investigated the association between coronary heart disease (CHD) and the serology of the periodontitis, through the determination of IgG serum antibodies for Aggregactibacter actinomycentemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. The authors found out that in the dentate population, the CHD was prevalent in patients positive for P. gingivalis and with high combined response of antibodies, suggesting that periodontal infection may result in an acquired immune response and will be able to participate in the pathogenesis of CHD. This reasoning, the authors reported that the periodontal disease and the release of bacterial products (bacterial lipopolysaccharide and endotoxins) stimulate the immune system to release a series of cytokines and inflammatory mediators that can encourage the formation of atheromas.[21]

Thus, the objective of this study is to evaluate the cardiovascular risk in obese patients with chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population screening

After approval by Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number 01/08), 380 patients were examined from March 2008 through June 2009. Participants had to fulfill the following general inclusion criteria: Obese patients body mass index (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 ); ≥35 years old; a clinical diagnosis of generalized chronic periodontitis[22] considering a minimum of 6 teeth with periodontal probing depths (PPDs) ≥5 mm and clinical attachment level (CAL) ≥3 mm; subjects have to possess at least 20 teeth (excluding third molars); present negative history of antibiotic therapy during the last 6 months and anti-inflammatory treatment in the last 3 months and present absence of periodontal treatment in the last 6 months.

The sample size was calculated in a previous pilot study, using the t-test for independent means of the clinical insertion level in obese (3.8 ± 0.35 mm) and non-obese patients (4.1 ± 0.34 mm). The sample size was estimated in 24 patients per group, considering a power of 85% and α of 0.05.

Anthropometric measurement

Obesity was confirmed by the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) measurements (≥0.85 for women and ≥0.9 for men).[4] Waist circumference (WC) (≥88 cm for women and ≥102 cm for men),[23] and percentage of BF, using the bio-impedance method (≥33% for women and ≥25% for men). The obese patients presented BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 while the non-obese patients or normal weight subjects presented BMI ranging from 18.5 kg/m2 to 24.9 kg/m2 and WHR, WC and BF measurements less than the reference values obtained in obese patients.[6]

The measurement of systolic and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was performed as well as the fulfillment of a specific questionnaire for checking whether the patients are smokers, whether they perform physical activity and the frequency of it.

Periodontal parameters

A single examiner was trained to evaluate the clinical periodontal parameters (r = 0.962, P = 0.002). The clinical periodontal examination was performed using a manual periodontal probe (PCPN115BR, Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL). The analyzed parameters were visible plaque index, gingival bleeding index (GBI),[24] PPD, BOP and CAL. The PPD and CAL were grouped according to the severity in ≤3 mm, 4-6 mm and ≥7 mm.[22]

Laboratory analysis

Laboratory analyzes involved triglycerides, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, glycemia, glycosylated hemoglobin dosages. Volunteers were instructed to fast for 12 hours and the collection was going to be held in the morning at the laboratory of clinical analysis.

Analysis of cardiovascular risk indicators

We used the criteria proposed by the Framingham Score to evaluate the indicators of cardiac risk.[25] After obtaining the data, the percentage value will be calculated for all patients with relation to the risk of developing CVD in the next 10 years using the Framingham Score. For this purpose, we performed the measurement of systolic and DBP as well as the completion of a specific questionnaire for verification of use and frequency of smoking, physical activity and its frequency. This group of data together with the clinical and laboratory data was processed by the method of cardiac risk stratification of coronary artery disease (CAD): Framingham Score.[25] From then on, we calculated a percentage value for all patients having the risk of developing CAD in the next 10 years through the Framingham Score: Low (<10%), medium (10% to <20%) and high risk (≥20%).

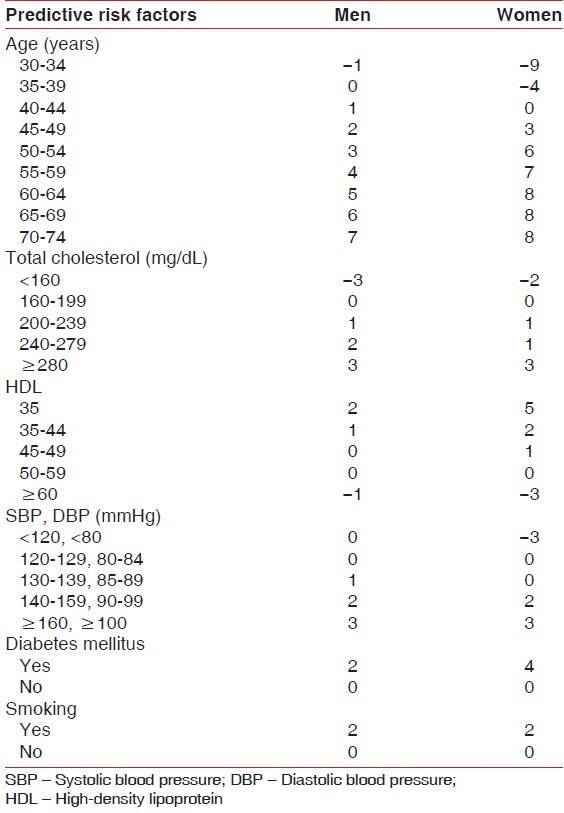

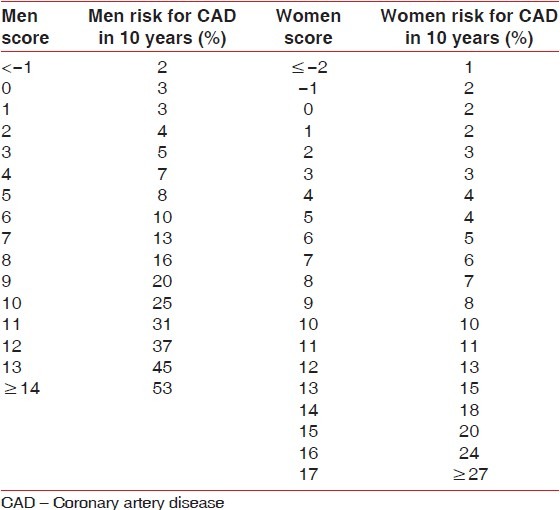

Framingham score

The calculation of the Framingham Score was performed through the sum of pre-defined values in Tables 1 and 2, referring to the intensity value of the predictive risk factor for cardiovascular disease in 10 years, whereas: Age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), total cholesterol, HDL, smoking (quantity consumed in the last month).

Table 1.

Score from the Framingham score

Table 2.

Risk of acute coronary event associated with the Framingham score

Data management and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using a specific program (BioEstat 4.0, Mamirauα Civil Society (“Sociedade Civil Mamirauα”), Belém, Brazil). The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Mann-Whitney's test was performed for ordinal data. McNemar's test was used for nominal data. A probability level of P ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Spearman test was used to verify possible correlation between obesity, periodontal disease and cardiovascular risk (α=0.05).

RESULTS

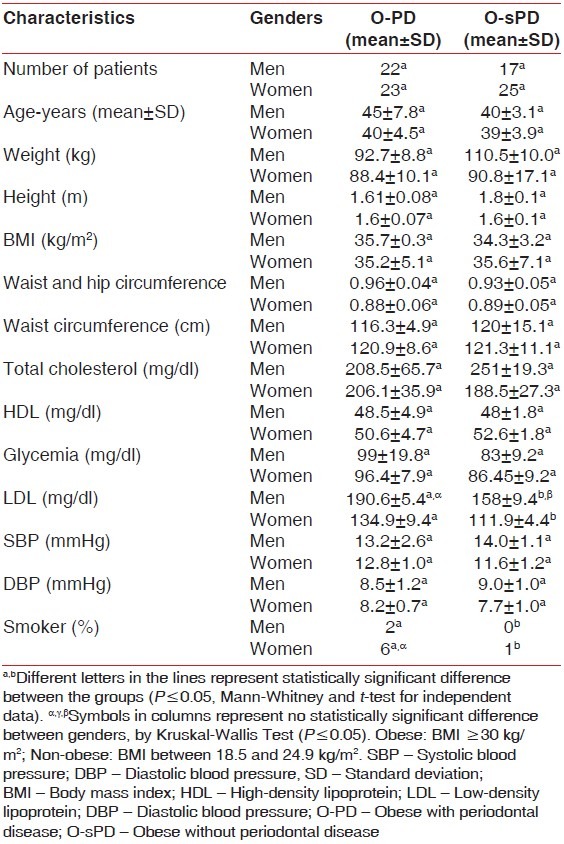

Patients were divided into two groups according to the periodontal characteristics found: Group O-PD: Obese patients with chronic periodontitis (n = 45), 22 men and 23 women, with a mean age of 45 (±7.8) and 40 (±4.5) years, respectively; and Group O-sPD: Obese patients without chronic periodontitis (n = 42), 17 men and 25 women with a mean age of 40 (±3.1) and 39 (±3.9) years, respectively.

Patients showed a BMI mean of 35.2 (±5.1) kg/m2 . In group O-PD, there were similarities between genders for: Age, SBP, DBP, total cholesterol and HDL [Table 3].

Table 3.

Demographic and anthropometric data for the population in the study

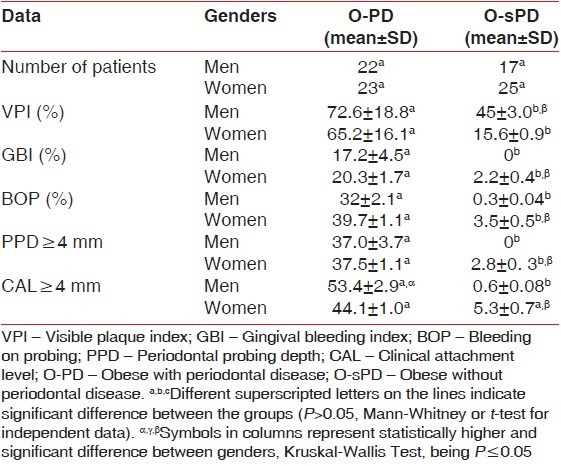

In relation to evaluated oral parameters, it was observed that there were similarities between the genders within each group for the periodontal parameters GBI, blood pressure, PD ≥ 4 mm and CAL ≥ 4 mm [Table 4]. Individuals in group O-PD presented higher periodontal levels if compared with group O-sPD, regardless of gender.

Table 4.

Clinical periodontal parameters (average and SD)

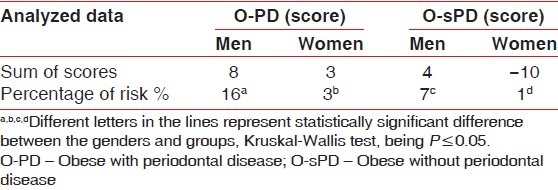

It was observed that in spite of women presenting the highest glycemia level, and the occurrence of smoking, O-PD men presented a 16% - risk of developing CAD in 10 years, which is higher than the risk found in women (3%). In group O-sPD, men had higher rates of SBP, DBP and total cholesterol than women, at a 7% - risk of developing CAD in 10 years, which was higher than the risk found in women (1%) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Cardiovascular risk by the Framingham score

The cardiovascular risk was positively correlated to obesity (O-sPD group) (r = 0.53; P < 0.0001) and to periodontal disease in obese patients (O-PD groups) (r = 0.72; P < 0.0001). It means that obesity and periodontal conditions increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (Spearman test).

DISCUSSION

Considering the existence of a strong correlation of risk factors with the increase in the prevalence of CVD, some studies have been directed to early identification of high-risk individuals to various diseases. According to the data in the studies of Framingham and PROCAM scores,[25] which evaluate the occurrence probability of a cardiovascular event, such as acute myocardial infarction, sudden death or angina, in the next 10 subsequent years, the influence of risk factors such as altered lipid profile, with the LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, age and diabetes mellitus are independent for the affection of atherosclerosis and consequent ischemic heart disease, but when they are associated, they increase in an alarming way the risk for CVD.

Sposito et al. suggested that approximately 20% of the cases of CVD are associated with the condition of overweight or obesity.[25] In addition, 60% of obese individuals reach 60 years, when compared to 90% of thin people.[6] Besides, Sposito et al. observed that 50% of the acute ischemic syndrome occurrences, reported in a university hospital is correlated with traditional risk factors (smoking, diabetes, dyslipidemia) and the other half, correlated with other factors, such as infectious agents, inflammatory mediators, the hemostatic markers and elevated homocysteine.[25] Corroborating this idea of “new” risk factors involved in the pathophysiology of acute ischemic syndromes, Wilson et al.[26] emphasize the role of the cells and inflammatory factors, both in the development of pathology and in the process of acute exacerbation of heart diseases.

Epstein et al. have found that the changes to the measures of WC and the WHR are related to a high risk for CHD.[27] Despite the fact that BMI is considered the anthropometric index recommended for clinical analysis of longitudinal follow-up after the intervention cardiology,[28] according to other study,[29] this index has been related to a significant extent with cardiovascular disease, especially in the presence of diabetes mellitus.

Due to the complexity for the diagnosis of atherosclerosis because it presents multifactorial etiology,[30] at present study the organic, environmental and behavioral conditions as possible predictors of cardiovascular risk. Evidences suggest that changes in one or more risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides) and glycemia, can affect the evolution of the disease.[31,32] In observational studies, it was found that the sedentary individuals were twice as likely to develop coronary event compared with physically active ones.[33]

Considering that the LDL is involved with the development and progression of ateroscleroses, while the HDL is related to the reverse transport of lipids in the liver tissue.[34] Persson and Persson, suggested that high serum levels of LDL and low levels of HDL are predictive of cardiovascular disease; thus, representing important risk factors for heart disease.[35] This fact may justify the laboratory data of O-PD group in which LDL level was greater in relation to group O-sPD.

The groups had some similarities considering the periodontal parameters; however, in spite of women had higher glycemia level, occurrence of smoking, O-PD men presented a 13% - risk over of developing CAD in 10 years, than O-PD women, 9%-risk over than O-sPD men and 15%-risk over than O-sPD women, by the Framingham Score.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that the association of obesity and periodontal disease potentially increases the risk for heart diseases.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Monteiro CA, D’A Benicio MH, Conde WL, Popkin BM. Shifting obesity trends in Brazil. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:342–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: A two-way relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:51–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopelman PG. Obesity as a medical problem. Nature. 2000;6:635–43. doi: 10.1038/35007508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Koga T, Tsuzuki M, Ohshima A. Relationship between upper body obesity and periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1631–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800070701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alabdulkarim M, Bissada N, Al-Zahrani M, Ficara A, Siegel B. Alveolar bone loss in obese subjects. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2005;7:34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO-World Health Organization. Report of the WHO Consultation on Obesity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deurenberg P, Yap M. The assessment of obesity: Methods for measuring body fat and global prevalence of obesity. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;13:1–11. doi: 10.1053/beem.1999.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;96:939–49. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:911–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366:1197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1983;67:968–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck JD, Offenbacher S. The association between periodontal diseases and cardiovascular diseases: A state-of-the-science review. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:9–15. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umino M, Nagao M. Systemic diseases in elderly dental patients. Int Dent J. 1993;43:213–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:38–53. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doll S, Paccaud F, Bovet P, Burnier M, Wietlisbach V. Body mass index, abdominal adiposity and blood pressure: Consistency of their association across developing and developed countries. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:48–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Borawskit EA. Obesity and periodontal disease in young, middle-aged, and older adults. J Periodontol. 2003;74:610–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarlati F, Akhondi N, Ettehad T, Neyestani T, Kamali Z. Relationship between obesity and periodontal status in a sample of young Iranian adults. Int Dent J. 2008;58:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ylöstalo P, Suominen-Taipale L, Reunanen A, Knuuttila M. Association between body weight and periodontal infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickson BC, Gotlieb AI. Towards understanding acute destabilization of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2003;12:237–48. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(03)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armitage GC. Periodontal diseases: Diagnosis. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:37–215. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association of National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sposito AC, Caramelli B, Fonseca FA, Bertolami MC, Afiune Neto A, Souza AD, et al. IV Brazilian guideline for dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis prevention: Department of atherosclerosis of brazilian society of cardiology. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;88(Suppl 1):2–19. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007000700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: The Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1867–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein SE, Zhou YF, Zhu J. Infection and atherosclerosis: Emerging mechanistic paradigms. Circulation. 1999;100:e20–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruberg L, Weissman NJ, Waksman R, Fuchs S, Deible R, Pinnow EE, et al. The impact of obesity on the short-term and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: The obesity paradox? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:578–84. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01802-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarastchuk JC, Guérios EE, Bueno Rda R, Andrade PM, Nercolini DC, Ferraz JG, et al. Obesity and coronary intervention: Should we continue to use Body Mass Index as a risk factor? Arq Bras Cardiol. 2008;90:284–9. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2008000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balkau B, Deanfield JE, Després JP, Bassand JP, Fox KA, Smith SC, Jr, et al. International Day for the evaluation of abdominal obesity (IDEA): A study of waist circumference, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus in 168,000 primary care patients in 63 countries. Circulation. 2007;116:1942–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Libby P. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of the acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2001;104:365–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy RI. Cholesterol and coronary artery disease. What do clinicians do now? Am J Med. 1986;80:18–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell KE, Thompson PD, Caspersen CJ, Kendrick JS. Physical activity and the incidence of coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Public Health. 1987;8:253–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.08.050187.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, Maroni J, Szarek M, Grundy SM, et al. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1301–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persson GR, Persson RE. Cardiovascular disease and periodontitis: An update on the associations and risk. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(Suppl 3):62–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]