Abstract

Background:

Schizophrenia is a psychosis characterized by delusions and hallucinations occurring in clear consciousness. Studies have shown that the cytokines may modulate dopaminergic metabolism and schizophrenic symptomatology in schizophrenia. Cytokine involvement in periodontal disease is also well documented. To date, however, there has been relatively little research assessing periodontal status of patients with schizophrenia. The present study was therefore mainly intended to understand the exact link, if any, between periodontal disease and schizophrenia.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 250 schizophrenic patients (140 males and 110 females), between 25 and 55 years of age, were selected from the out patient department of National Institute of Mental Health and Neural Sciences, Bangalore and their periodontal status was assessed as part of this cross-sectional epidemiological survey.

Results:

ANOVA showed that there was increased evidence of poor periodontal condition, as evidenced by gingival index and plaque index in patients who had been schizophrenic for a longer duration of time (P < 0.001). So also, higher probing pocket depths were found in schizophrenics suffering from a longer period of time than others (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Although oral neglect might be a cause of poor periodontal health in schizophrenics, the possible link between periodontal diseases giving rise to schizophrenia cannot be overlooked due to the presence of cytokine activity which is present both in schizophrenia and periodontal disease.

Keywords: Chronic periodontal disease, cytokines, oral health, periodontal disease-systemic interactions, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by a disintegration of thought processes and of emotional responsiveness.[1] It most commonly manifests as auditory hallucinations, paranoid or bizarre delusions, or disorganized speech and thinking, and it is accompanied by significant social or occupational dysfunction. The onset of symptoms typically occurs in young adulthood; with a global lifetime prevalence of about 0.3-0.7%.[2] Diagnoses is based on observed behavior and the patient's reported experiences.

Schizophrenia is a severe form of mental illness affecting about 7 per thousand of the adult population, mostly in the age group 15-35 years. Though the incidence is low (3-10,000), the prevalence is high due to chronicity.[3] The prevalence rate for schizophrenia is approximately 1.1% of the population over the age of 18 (source: NIMH) or, in other words, at any one time as many as 51 million people worldwide suffer from schizophrenia, including 6 to 12 million people in China (a rough estimate based on the population), 4.3 to 8.7 million people in India (a rough estimate based on the population), 2.2 million people in USA,285,000 people in Australia, over 280,000 people in Canada, and over 250,000 diagnosed cases in Britain.[4]

The exact cause of schizophrenia is not yet known; however, there are strong indications that it results from abnormalities in brain development and maturation that adversely affect neural circuits and neurotransmitter systems. The delusions and hallucinations may result from excess dopamine activity in limbic areas of the brain. Decreased emotional responsiveness, paucity of speech content, and a lack of goal-initiated behaviors may result from dopamine deficiency in pre-frontal areas. Aberrant levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin also have been implicated as a possible cause of both negative and positive symptoms. Structural imaging studies have shown that patients with schizophrenia have reduced whole-brain volume and specific reductions in cortical gray and white matter, frontal lobes, thalamus, and limbic system structures (amygdala, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus).[5] Functional imaging studies such as regional cerebral blood flow and positron emission tomography have demonstrated that the prefrontal cortex suffers impaired blood flow, as well as inadequate oxygen use and glucose metabolism, when a patient with the disorder performs problem-solving tasks.[6,7]

Advanced dental disease is seen frequently in patients with schizophrenia for several reasons:[8]

The disease impairs ability to plan and perform oral hygiene procedures

Some of the antipsychotic medications have adverse effects such as xerostomia or dry mouth

Limited access to treatment because of lack of financial resources and adequate number of dentists comfortable in providing care.

Reports have confirmed the association of periodontal disease with various neurologic conditions such as Alzheimer's disease[9] and Schizophrenia.[8] Although a bidirectional link between Alzheimer's disease and periodontal disease has been proposed, reports of the association between schizophrenia and periodontal disease have so far concluded only a unidirectional link with poor periodontal health in schizophrenics being attributed to a partial or complete neglect of oral health.

The present study was aimed at exploring for the first time the possible bidirectional link between periodontal disease and schizophrenia. The objective was primarily directed at assessing the periodontal status of schizophrenic patients and assess if there was a correlation, if any between the duration of illness in both the conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following approval of the Ethical Committee, Bangalore Institute of Dental Sciences and National Institute of Mental Health And Neural Sciences, Bangalore, 250 patients (140 males and 110 females) with a positive history of schizophrenia were selected from the out-patient department of National Institute of Mental Health And Neural Sciences, Bangalore, during the period from June 2011 to September 2011. A detailed case history was recorded for each patient with special emphasis on the medications being used and duration of schizophrenia. Patients with any other co-existing systemic disease or condition as well any other neurological disorder were ruled out of the study. In addition, patients with any kind of periodontal therapy done in the past were also excluded from the study.

The following periodontal parameters were examined:

Gingival index (GI)

Plaque index (PI)

Probing pocket depth (PPD).

All the 250 patients were on antipsychotic medication as prescribed by the neurophysician and reported no history of any other systemic illness and also no history of any kind of periodontal treatment in the past.

The parameters assessed were statistically analyzed by the mini tab version 14 and ftss version 13 statistical program using analysis of variance (ANOVA). In case of significant difference between groups, multiple comparisons (post hoc test) using the Bonferroni test was carried out.

RESULTS

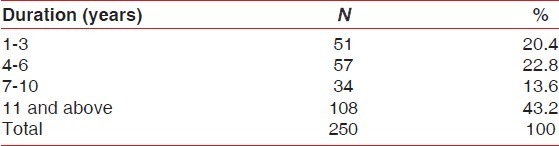

The 250 selected patients were divided on the basis of duration of schizophrenia in years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sample distribution according to duration of disease

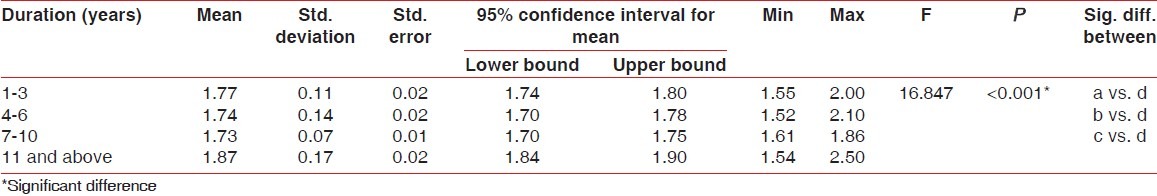

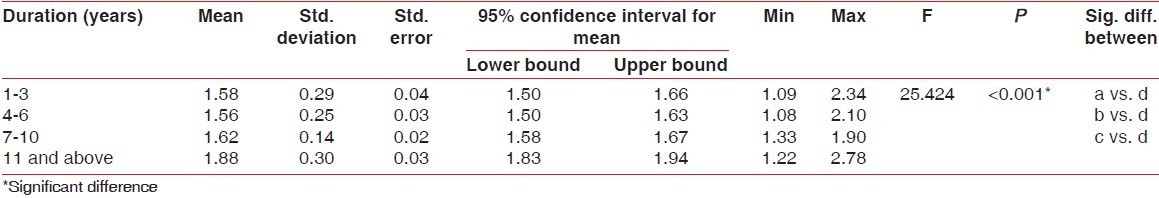

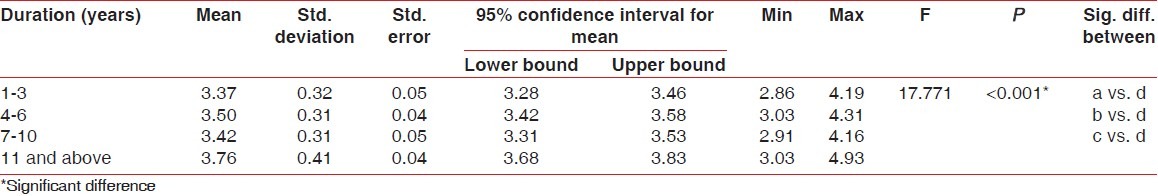

Higher mean GI [Table 2], PI [Table 3], and PPD [Table 4] were recorded in 11 years and above group followed by 1-3 years group, 4-6 years group and 7-10 years group, respectively. The difference in mean GI, PI, and PPD between the groups was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001). Further, using the Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons, it was found that significant difference existed between 11 years and above group and all the other groups (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of gingival index

Table 3.

Comparison of plaque index

Table 4.

Comparison of probing pocket depth

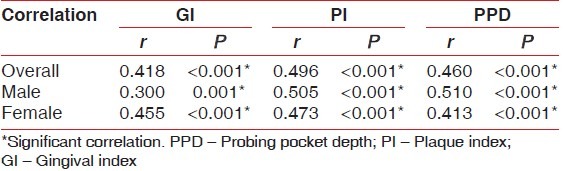

In the overall sample, and when males and females were taken individually, correlation between duration of disease and GI was found to be moderate and significant (P < 0.001). So also, correlation between duration of disease and PI and between duration of disease and PPD was found to be moderate and significant (P < 0.001) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation between duration of disease (years) and other clinical parameters

DISCUSSION

Schizophrenia ranks among the top 10 causes of disability in developed countries worldwide.[10] Social problems, such as long-term unemployment, poverty, and homelessness, are common. The average life expectancy of people with the disorder is 12 to 15 years less than those without, this being the result of increased physical health problems and a higher suicide rate (about 5%).[2] Schizophrenia has great human and economic costs.[2] It results in a decreased life expectancy of 12-15 years, primarily because of its association with obesity, sedentary lifestyles, and smoking.[2] It is also a major cause of disability, with active psychosis ranked as the third-most-disabling condition after quadriplegia and dementia and ahead of paraplegia and blindness.[11] Approximately three-fourths of people with schizophrenia have ongoing disability with relapses.[12] Schizophrenia affects around 0.3-0.7% of people at some point in their life,[2] or 24 million people worldwide as of 2011.[3] It occurs 1.4 times more frequently in males than females and typically appears earlier in men,[13 ] the peak ages of onset being 20-28 years for males and 26-32 years for females.[14]

An accurate understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of the condition is not yet clear. A combination of genetic and environmental factors may play a role in the development of schizophrenia.[2,13] People with a family history of schizophrenia who suffer a transient or self-limiting psychosis have a 20-40% chance of being diagnosed 1 year later.[15] To this effect, a number of attempts have been made to explain the link between altered brain function and schizophrenia.[16 ] One of the most common is the dopamine hypothesis, which attributes psychosis to the mind's faulty interpretation of the misfiring of dopaminergic neurons.[16] Dopamine dysregulation can be caused due to a number of factors including systemic infections, inflammations, etc., Studies have suggested the role of cytokines such as interleukins, which may modulate dopaminergic metabolism and schizophrenic symptomatology in schizophrenia.[17] These cytokines are also significantly elevated and actively responsible for the tissue destruction in periodontal disease.[18,19,20] With this cue in mind, the present study was primarily undertaken to establish a bidirectional link, if any, between periodontal disease and schizophrenia. As evidenced by the results, when gingival inflammation and plaque were correlated to the duration of schizophrenia, there was a highly significant association. This could be attributed to the fact that schizophrenics are highly negligent with regard to oral health. In addition, all of the patients in the study were under antipsychotic medication which has an adverse effect of xerostomia.[8 ] Both these events lead to poor oral and periodontal health.

The mean PPD also showed a high degree of correlation with the duration of schizophrenia suggesting that increased periodontal deterioration could be the result of increased local factors due to poor oral hygiene and xerostomia. However, it also brings to the fore another aspect to this association. Patients who have been schizophrenic for a longer period of time showed greater mean pocket depths thereby suggesting greater periodontal destruction. This could be due to the fact that these patients may have been exposed to the cytokines such as interleukins and other inflammatory mediators associated with periodontal disease for a longer time. Although these patients have been on medications for the duration of their disease, very minimal improvement was noted in their schizophrenic condition. This could possibly imply that the continued presence of the inflammatory cytokines due to periodontal disease may in some way have an influence on the neurotransmitter mechanism in schizophrenia by modulating the dopaminergic metabolism thereby negating the effects of medication. IL-1β, a key cytokine in periodontal disease, has been shown to affect the neurotransmitters by enhancing dopamine survival and inhibiting glutamate release leading to hypo function of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors which may lead to schizophrenia.[21] Similarly, elevated IL-6 levels, another cytokine implicated in periodontal disease,[22] have been shown to be associated with duration of illness of schizophrenia.[23]

Although research is still on with regard to the exact pathophysiology of schizophrenia, the possible mechanism by which periodontal disease may be implicated is suggested for the first time based on the findings in our study. In addition, there have also been reports of increased prevalence of salivary P. gingivalis in schizophrenic patients when compared to non-psychiatric controls[24] and also a positive correlation has been reported between quantity of P. gingivalis cells and severity of psychopathology of schizophrenia.[24 ] However, the exact mechanism of this correlation is not clear. The cytokine theory suggested in our study could also possibly explain the above association. Thus, the suggestion that periodontal disease may possibly contribute to schizophrenic symptoms may form an important basis for understanding the yet unclear pathogenesis of schizophrenia and also paves the way to providing an alternate method of management of the condition with a periodontal approach more so, since evidence for the effectiveness of early intervention in schizophrenics is inconclusive.[25] While there is some evidence that early intervention in those with a psychotic episode may improve short-term outcomes, there is little benefit from these measures after 5 years.[2] Attempting to prevent schizophrenia in the prodrome phase is of uncertain benefit and therefore is not recommended.[26] Prevention is also difficult as there are no reliable markers for the later development of the disease.[27] On the other hand, the drugs used to manage schizophrenics, though beneficial, have been reported to produce certain side effects such as considerable weight gain, diabetes, and risk of metabolic syndrome.[28 ] Some atypicals such as quetiapine and risperidone are associated with a higher risk of death compared to the atypical perphenazine, while clozapine is associated with the lowest risk of death.[29] It remains unclear whether the newer antipsychotics reduce the chances of developing neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a rare but serious neurological disorder.[30] All the above observations and reports highlight the fact that effective therapeutic measures for schizophrenia are still evolving. If periodontal disease is implicated as one of the possible contributing factors to schizophrenic symptoms as suggested in our study, then management of the condition by controlling periodontal disease is a far more feasible option. Further research on these lines i.e. evaluation of changes in schizophrenic symptoms following periodontal therapy could probably throw more light on this.

CONCLUSION

The findings in our study therefore suggest that although not definitive, the role of periodontal disease in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia cannot be ruled out. However, further long term interventional studies involving periodontal management of schizophrenic patients and monitoring the cytokine profile followed by assessment of changes in the schizophrenic status of these patients need to be undertaken.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oxford Reference Online. Maastricht University Library; 2010. “Schizophrenia” Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Schizophrenia. 2011. [Last cited on 2011 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/schizophrenia/en/

- 4.Schizophrenia.com[Internet] A community oriented website, providing in-depth information, support and education related to schizophrenia and related disorders. copyright 1996-2013. [updated April 2013,cited December 2011]. Available from: http://www.shizophrenia.com/szfacts.htm .

- 5.Staal WG, Hulshoff Pol HC, Schnack HG, Hoogendoom ML, Jellema K, Kahn RS. Structural brain abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia and their healthy siblings. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:416–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashima M, Kawasaki Y, Urata K, Sakai N, Nagasawa T, Koshino Y, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow in male schizophrenic patients performing an auditory discrimination task. Schizophr Res. 2000;42:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JJ, Mohamed S, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, et al. Regional neural dysfunctions in chronic schizophrenia studied with positron emission tomography. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:542–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedlander AH, Marder SR. The Psychopathology, Medical Management and Dental Implications of Schizophrenia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:603–10. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers J. The Inflammatory Response in Alzheimer's disease. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1535–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The global burden of disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank, Harvard University Press; 1996. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 28]. Available from: http://www.who.int/msa/mnh/ems/dalys/intro.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ustun TB, Rehm J, Chatterji S, Saxena S, Trotter R, Room R, et al. Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. Lancet. 1999;354:111–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith T, Weston C, Lieberman J. Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment) Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:338–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picchioni MM, Murray RM. Schizophrenia. BMJ. 2007;335:91–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39227.616447.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castle D, Wessely S, Der G, Murray RM. The incidence of operationally defined schizophrenia in Camberwell, 1965-84. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:790–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drake RJ, Lewis SW. Early detection of schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:147–50. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freudenreich O, Weiss AP, Goff DC. Psychosis and schizophrenia. In: Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Biederman J, Rauch SL, editors. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. Ch. 28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YK, Kim L, Lee MS. Relationships between interleukins, neurotransmitters and psychopathology in drug-free male schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 2000;44:165–75. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takashiba S, Naruishi K, Murayama Y. Perspective of cytokine regulation for periodontal treatment: Fibroblast biology. J Periodontol. 2003;74:103–10. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graves DT, Cochran D. The contribution of interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor to periodontal tissue destruction. J Periodontol. 2003;74:391–401. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preshaw PM, Taylor JJ. How has research into cytokine interactions and their role in driving immune responses impacted our understanding of periodontitis? J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):60–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song C, Li X, Kang Z, Kadotomi Y. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ethyl-Eicosapentaenoate Attenuates IL-1b-Induced Changes in Dopamine and Metabolites in the Shell of the Nucleus Accumbens: Involved with PLA2 Activity and Corticosterone Secretion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:736–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gani DK, Lakshmi D, Krishnan R, Emmadi P. Evaluation of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in the peripheral blood of patients with chronic periodontitis. J Ind Soc Periodontol. 2009;13:69–74. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.55840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganguli R, Yang Z, Shurin G, Chengappa KN, Brar JS, Gubbi AV, et al. Serum Interleukin-6 Concentration in Schizophrenia: Elevation Associated With Duration of Illness. Psychiatry Res. 1994;51:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fawzi MM, El-Amin HM, Elafandy MH. Detection and quantification of porphyromonas gingivalis from saliva of schizophrenia patients by culture and Taqman Real-Time PCR: A Pilot Study. Life Sci J. 2011;8:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;18:CD004718. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Koning MB, Bloemen OJ, van Amelsvoort TA, Becker HE, Nieman DH, van der Gaag M, et al. Early intervention in patients at ultra high risk of psychosis: Benefits and risks. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:426–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGorry P. The empirical status of the ultra high-risk (prodromal) research paradigm. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:661–4. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schultz SH, North SW, Shields CG. Schizophrenia: A review. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:1821–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chwastiak LA, Tek C. The unchanging mortality gap for people with schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:590–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ananth J, Parameswaran S, Gunatilake S, Burgoyne K, Sidhom T. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and atypical antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:464–70. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]