Abstract

Background:

The prison population is a challenging one with many health problems, including oral health. In a country like India the information regarding the status of periodontal health in prisoners is scant.

Aim:

To assess the periodontal status of the jail inmates at Mangalore District Jail.

Materials and Methods:

Cross sectional survey Participants: A Randomly selected sample of 82 male inmates of age group 18-60 years were examined using community periodontal index (CPI) and loss of attachment from modified WHO oral health assessment proforma (1997).

Results:

The prevalence of periodontal disease was 97.5%. Majority of the study population had CPI score of 2 and 1. Majority of the prisoners were severely affected with loss of attachment with 35% had loss of attachment more than 3 mm.

Conclusion:

As there are no oral health care facilities available in the prison set up, this study emphasizes the need for special attention from government and voluntary organizations to provide the oral health care services to inmates and improve the overall health status of the prisoners.

Keywords: Community periodontal index, loss of attachment, oral health, periodontal disease, prison inmates

INTRODUCTION

The health of prisoners is of great concern particularly because the number of persons under the jurisdiction of correction systems, including those on probation or parole, continues to increase dramatically. It is generally acknowledged from extensive research that correctional populations are more vulnerable to a wide range of health problems, most commonly alcoholism, drug abuse, infectious diseases, chronic illnesses, mental illnesses, and psychosocial and psychiatric problems.[1]

The prison population is a unique and challenging one, with many health problems, including poor oral health. Dental diseases can reach epidemic proportions in the prison setting.[2]

Many challenges exist in delivering services within the prison system. This includes service provision with respect to security procedures, recruitment, and retention of dental staff in relation to strong demand and lucrative remuneration for dentists in private practice. There is currently no standardized system of assessment or prioritization of the dental needs of prisoners.[3]

The prisoner's health is neglected due to poor availability of any health professional who wants to work in a prison. The lack of health concern, facilities, and expertise, leads to further deterioration in the health of inmates. This explains the reason for such limited studies in a prison set-up, especially in India.[4]

Few studies carried out in other parts of the world, in a prison setup, have observed that the oral hygiene status of the inmates is poor compared to the general population and there is a higher prevalence of periodontal diseases.[5,6,7] This might be due to the lack of availability of oral hygiene devices and knowledge about maintenance of oral hygiene, which may lead to the increase of periodontal diseases among prisoners.

There are no studies done in India with regard to the periodontal health status of these corrective populations, and hence, the information regarding the periodontal status of prisoners is scant. As the information is sparse, the aim of the present study, the first of its kind, is to assess the periodontal health status with the parameters of age distribution, Community Periodontal Index (CPI) score, and Loss of Attachment (LOA) score, among the prisoners.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was carried out at the Mangalore district prison, Karnataka, India. The total prison population of the Mangalore district prison was 260 (250 males, 10 females) on the day of the survey. The sample size was calculated using an online sample size calculator, available at http://www.surveysystem.com; the sample required for a finite population of 260, at a confidence level of 95% was 82. A randomly selected sample of 82 male inmates within the age group of 18 to 60 years was examined. All the possible participants (260) were listed and numbered. A number was first chosen at random and every third number was picked thereafter. If a potential participant was selected, but declined to take part, the next available number was substituted. The duration of the inmates stay in the prison extended from six months to a year.

Collection of the data

The inmates were asked to sit comfortably on a chair in a well ventilated room and clinical examination was carried out under natural light with a mouth mirror, explorer, and a Community Periodontal Index and Treatment Needs (CPITN-E) probe. The data were recorded by the investigator on a printed Modified World Health Organization Oral Health Assessment Form (1997). The community periodontal index (CPI) and loss of attachment (LOA) blocks of the proforma were recorded as per the requirement of the study.

Statistical analysis

The data were then entered manually into the computer, and tabulated and analyzed. The statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 13 was used. The various tests used for analysis were the frequency, percentage, mean, and Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was taken to be statistically significant for the purpose of analysis.

RESULTS

Age distribution

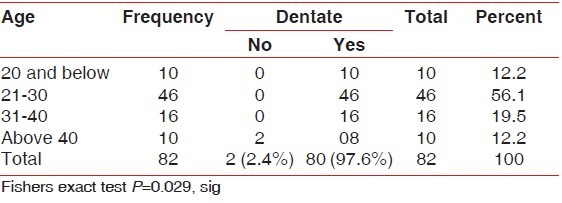

A majority of the inmates were in the age group of 21 to 30 years (56.1%), followed by the age group of 31 to 40 years (19.5%). Twelve percent of the inmates were in the age group of above 40 years. The rest of the inmates were below 20 years of age (12%) [Figure 1]. Among the inmates examined two (2.4%) were edentulous in the age group of above 40 and 80 (97.6%) were dentate inmates [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Pie chart showing distribution of age

Table 1.

Number and percent of inmates according to age distribution along with dentate status

Prevalence of subjects affected

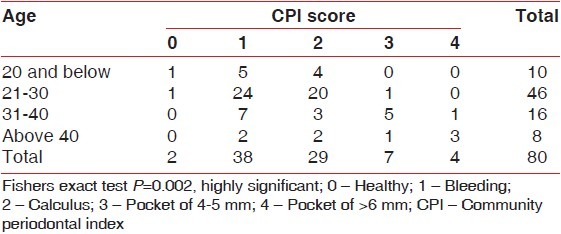

A majority of the study population had Community Periodontal Index (CPI) score of 1, which implied that the subjects had bleeding on probing; 36.3% of the subjects had a score of 2, which implied presence of deep calculus; 13.8% had scores of 3 and 4, which implied that they had a pocket depth of more than 4 mm; and 2.5% had a score of 0, which implied that their periodontal status was healthy [Table 2].

Table 2.

Prevalence of subjects affected

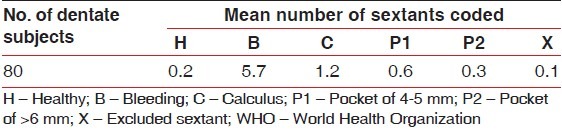

Mean number of sextants

The mean number of sextants coded (per dentate subject) showed a score of 0.2 for healthy tissues, 5.7 for bleeding from tissues on probing, 1.2 for the presence of calculus, and 0.9 for a pocket depth of >4 mm [Table 3]. This is the WHO-preferred cumulative tabulation on the basis of scoring 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or X on a cumulative basis (that is 1 or higher score, 2 or higher score, etc.).

Table 3.

The WHO-preferred cumulative tabulation for mean number of sextants coded

Loss of attachment

A majority had a score of 0 (65%), which implied that the subjects had a loss of attachment ranging from 0 to 3 mm; 22.5% of the subjects had a score of 1, which implied that the loss of attachment was in the range of 4 - 5 mm; 6.3% of the subjects had a score of 2, which implied that loss of attachment was in the range of 6 - 8 mm; 3.8% had a score of 3, which implied that loss of attachment was in the range of 9 - 11 mm; and 2.5% had a score of 4, which implied that loss of attachment was in the range of >12 mm [Table 4].

Table 4.

Loss of attachment

DISCUSSION

The results of this cross-sectional study conducted among prison inmates of the Mangalore District prison provided a unique opportunity to analyze the periodontal status in this group. To assess the periodontal status and treatment needs of a given population, Ainamo et al. (1982), developed an index called the Community Periodontal Index for Treatment Needs (CPITN).[8] However, Baelum et al. (1995), observed that this may result in severe underestimation of periodontal treatment in younger individuals.[9] To overcome these limitations, another index called Community Periodontal Index (CPI) with attachment loss was included in WHO Oral Health Surveys - Basic Methods. The Community Periodontal Index (CPI) was introduced by the WHO to provide profiles of the periodontal health status and to plan intervention programs for effective control of periodontal diseases.[10]

The present study is the first of its kind, carried out exclusively on the periodontal status of prison inmates, and parameters like age distribution, dentate status, CPI score, and LOA score were evaluated among the prisoners and the periodontal status of each prison inmate was recorded. In literature, there have been very few studies carried out on the oral health status of prisoners. Of these, some studies[11,12,13] have reported that the periodontal status of prison inmates is worse than that of the general population.

Age distribution and dentate status

Periodontal diseases are mostly observed in older individuals. This shows that age is inevitably associated with the periodontal condition. The progression of disease may vary among the population, with varying age. Furthermore, without effective periodontal therapy, progression of periodontal diseases may be faster with increasing age.[14]

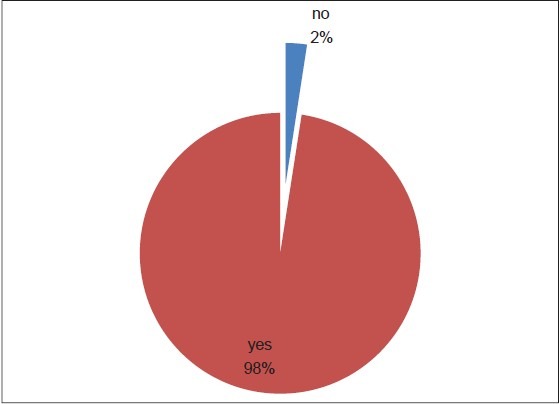

A survey carried out on 1187 dentate subjects among prison inmates in Australia, reports that there is an increase in chronic periodontal disease with concomitant increase in age, 100% occurrence of destructive periodontitis after the age of 40 years, and tooth loss owing to periodontitis, which accounts for 30 - 35% of all tooth extractions.[15] This study is in concordance with the present study, which has observed that correlation between age and a dentate status is significant [Table 1]. This implies that as age increases; there is also increased tooth loss [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Pie-chart showing dentate status

Community periodontal index score assessment

Community Periodontal Index (CPI) records the current periodontal status of the population. It was found that the CPI score among the inmates varied from 0 to 4. A survey carried out on 800 life imprisoned inmates in the Central Jails of Karnataka[16] observed that a majority of the subjects had a CPI score of 2, and 21.6% had a CPI score of 4. This study was in concordance with the present study, which found out that a majority of the inmates scored a CPI score of 1 (47.5%) and 2 (36.3%); 13.8% subjects had a score of 3 and 4; and 2.5% scored a CPI score of 0 [Table 2].

A majority of the CPI scores of 1 and 2 were in the age group of 20 - 30 years or below. Scores 3 and 4 were found in the age group of above 30 years. The correlation between the CPI score and age was highly significant (P =0.002), which implied a concomitant rise in CPI score with age, as age was regarded as an associated factor for periodontal diseases.[14]

Loss of attachment scores assessment

The loss of attachment score estimates the lifetime accumulated destruction of the periodontal attachment. A survey carried out on 800 life imprisoned inmates in the Central Jail of Karnataka (16), observed that 30.1% of the prisoners had an LOA score of 1 or 2 and 1.7% of the prisoners had a score of 4. This study was in concordance with the present study, which established that a majority had a score of 0 (65%) and 2.5% had a score of 4 [Table 4].

CONCLUSION

This survey demonstrates that the periodontal status of prison inmates was poor. There is a need to give more attention to oral health promotion, as eventually respondents will be returning to the community.

In light of the observations from the present study, the following recommendations can be made.

Prison inmates should be made aware of the need for oral healthcare and harmful effects of smoking, inadequate plaque control, and inadequate treatment facilities

Approach for general promotion of good oral hygiene practices should be carried out on a large scale for control and prevention of periodontal disease

Suitable toothbrushes and fluoride toothpaste should be made freely available in prisons

Government should consider employing a full-time dentist along with a physician to serve prisons located within distinct geographical localities.

This study also emphasizes the need for special attention from the government and voluntary organizations to meet the oral health needs of this special group. Further longitudinal studies should be conducted to explore the relationship between the onset and progression of periodontal diseases in the prison environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks go to the Inspector General of Police (Prison) Bangalore, Deputy Commissioner of Police Mangalore City Police, Prison Superintendent Mangalore District Prison, Rotary Club Belthangady, Principal, Staff and Post Graduates of KVG Dental College and Hospital and all the participants for their kind support during this research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Rotary Club Belthangady and KVG Dental College and Hospital, Sullia, D.K Karnataka

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nobil CG, Fortunato L, Pavia M. Oral health status of male prisoners in Italy. Int Dent J. 2007;57:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2007.tb00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey SB, Anderson AS. Reforming prison dental services in England – a guide to good practice. Health Educ J. 2005;4:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heng CK, Douglas EM. Dental caries experience of female inmates. J Public Health Dent. 2002;62:57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta RK, Singh GPI, Rajhree RG. Health status of inmates in prison. Indian J Commun Med. 2001;26:2001–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborn M, Butler T, Barnard PD. Oral health status of prison inmates in New South Wales, Australia. Aust Dent J. 2003;48:34–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2003.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clare JH. Survey, comparison, and analysis of caries, periodontal pocket depth, and urgent treatment needs in a sample of adult felon admissions 1996. J Correct Health Care. 1998;5:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luann H, Morris J, Jacob A. The oral health of a group of prison inmates. Dent Update. 2003;30:135–8. doi: 10.12968/denu.2003.30.3.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ainamo J, Barames D, Beagrie G. Development of the World Health Organization, Community Periodontal Index Treatment Needs. Int Dent J. 1982;32:281–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baelum V, Manji F, Wanzala P, Fejerskov O. Relationship between CPITN and periodontal attachment loss findings in an adult population. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:146–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham MA, Glenn RE, Field HM. Dental disease prevalence in a prison population. J Public Health Dent. 1985;45:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salive ME, Carolla JM, Brewer TF. Dental health status of male inmates in a state prison system. J Public Health Dent. 1989;49:83–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1989.tb02031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mixson GM, Eplee HC, Fell PH. Oral health status of a federal prison population. Public Health Dent. 1990;50:257–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1990.tb02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman M, Takei H, Klokkevold P, Carranza F. Carranza's Clinical Periodontoly. 11th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saundus Co; 2011. Aging and the Periodontium; pp. 31–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osborn M, Butler T, Barnard PD. Oral health status of prison inmates -New South Wales, Australia. Aust Dent J. 2003;48:34–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2003.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veera R, Chadlavda VK, Sunitha S, Murya M. A survey on oral health status and treatment needs of life-imprisoned inmates in central jails of Karnataka, India. Int Dent J. 2012;62:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]