Abstract

Gingival enlargement, the currently accepted terminology for an increase in the size of the gingiva, is a common feature of gingival disease. Local and systemic factors influence the gingival conditions of the patient. These factors results in a spectrum of diseases that can be developmental, reactive and inflammatory to neoplastic. In this article, the history, etiology, clinical and histopathological features, treatment strategies and preventive protocol of inflammatory hyperplasia are discussed.

Keywords: Gingival enlargement, gingival hyperplasia, inflammatory hyperplasia

INTRODUCTION

The oral mucosa is constantly subjected to external and internal stimuli and therefore manifests a spectrum of diseases that range from developmental, reactive and inflammatory to neoplastic.[1] Reactive hyperplastic lesions represent the most frequently encountered oral mucosal lesions in humans.[2] These lesions represent a reaction to some kind of irritation or low-grade injury like chewing, trapped food, calculus, fractured teeth and iatrogenic factors, including overextended flanges of dentures and overhanging dental restorations.[3] Diagnosis of each lesion from the groups is aided by their clinical and radiographic features, but histopathology is the key for final diagnosis.[4]

Gingival enlargement may be caused by a multitude of causes. The most common is chronic inflammatory gingival enlargement, when the gingiva presents clinically as soft and discolored. This is caused by tissue edema and infective cellular infiltration, caused by prolonged exposure to bacterial plaque, and is treated with conventional periodontal treatment, such as scaling and root planing. Situations in which the chronic inflammatory gingival enlargements include significant fibrotic components that do not respond to and undergo shrinkage when exposed to scaling and root planing are treated with surgical removal of the excess tissue.[5] The accumulation and retention of plaque is the chief cause of inflammatory gingival enlargement. Risk factors include poor oral hygiene[6] as well as physical irritation of the gingiva by improper restorative and orthodontic appliances.[7]

CASE REPORT

A female patient aged 38 years reported with a chief complaint of swelling in the left front region of the gums.

The lesion was nodular, circumscribed polypoid lesion measuring about 1.5 cm × 1.2 cm, pinkish to reddish in color, which bled easily, and was painless. This lesion involved the marginal and interdental gingiva on the facial surface of the maxillary left canine and 1st premolar. Local factors plaque and calculus were present [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Pre-operative photograph

Oral hygiene instructions were given and scaling and polishing were done on the first visit. Then, the patient was recalled for surgical excision of the lesion. After excision, residual calculus was removed and root planing was performed [Figures 2 and 3]. The excised lesion was sent to the Department of Oral Pathology for histopathological examination. The patient was motivated to maintain oral hygiene and was asked to rinse her mouth with 0.2% chlorehexidene mouthwash twice daily for 1 week. The patient was kept under observation through recall checkups.

Figure 2.

Post-operative photograph

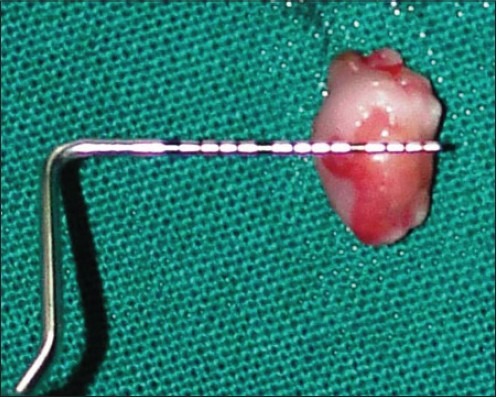

Figure 3.

Excised lesion

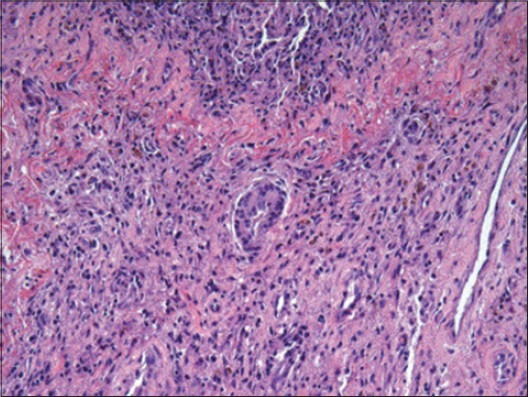

Microscopic examination revealed hyper-parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with ulceration and acanthosis of the stratum spinosum. The underlying dense fibrous connective tissue stroma showed severe chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells and a moderate number of endothelial-lined blood vessels suggestive of chronic inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of the specimen

Figures 5 and 6 show the post-operative photograph of the same lesion after 1 and 3 weeks, respectively.

Figure 5.

Healing after 1 week

Figure 6.

Healing after 3 weeks

DISCUSSION

Reactive hyperplasia comprises a group of fibrous connective tissue lesions that commonly occur in the oral mucosa as a result of injury or chronic irritation.[8] Chronic trauma can induce inflammation, which produces granulation tissue with endothelial cells and chronic inflammatory cells and, later, fibroblasts proliferate and manifest as an overgrowth called reactive hyperplasia. These tumor-like lesions are not neoplastic but indicate a chronic process in which an exaggerated repair occurs (granulation tissue and formation of scar) following repair.[9]

Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia or fibrous hyperplasia is a benign soft tissue response to a local irritant. It can be due to calculus, a sharp tooth, a broken filling, excessive plaque and other irritating factors. Fibrous hyperplasia clinically presents as a well-demarcated exophytic mass. The color ranges from normal to white or reddish depending upon whether or not the surface is ulcerated, keratotic or both or neither. It can be soft or firm in palpation.[10]

Histologically, inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia is made up of a mass of hyperplastic connective tissue with dilated blood vessels, usually with chronic inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells, but it can also be made up of solid connective tissue with minimum to no inflammatory cells, the latter called fibrous hyperplasia. The surface epithelium ranges from normal to acanthotic, ulcerated, keratotic or a combination of two or more of these features.[11]

Surgical excision is the preferred treatment of choice, with removal of local irritants to prevent recurrence. For hyperplastic lesions, a conservative approach is recommended. Local irritants should be removed. Those lesions failing to resolve should be surgically excised. Follow-up of the patient is needed as it exhibits a tendency to recur.[12]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Effiom OA, Adeyemo WL, Soyele OO. Focal reactive lesions of the gingival: An analysis of 314 cases at tertiary health institution in Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2011;52:35–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nartey NO, Mosadomr HA, Al-Cailani M, AlMobeerik A. Localised inflammatory hyperplasia of the oral cavity: Clinico-pathological study of 164 cases. Saudi Dent J. 1994;6:145–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarei MR, Chamani G, Amanpoor S. Reactive hyperplasia of the oral cavity in Kerman Province, Iran: A review of 172 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:288–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peralles PG, Borges Viana AP, Rocha Azevedo AL, Pires FR. Gingival and alveolar hyperplastic reactive lesions: Clinico-pathological study of 90 cases. Braz J Oral Sci. 2006;5:1085–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman MG, Takei H, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza’a Clinical Periodontology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996. p. 754. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirschfield I. Hypertrophic gingivitis; its clinical aspect. J Am Dent Assoc. 1932;19:799. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman MG, Takei H, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza’a Clinical Periodontology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996. p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ. Oral Pathology: Clinical-Pathologic Correlation. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008. pp. 156–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shadman N, Ebrahimi SF, Jafari S, Eslami M. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: A review of 123 cases. Dent Res J. 2009;6:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zain RB, Fei YJ. Fibrous lesions of the gingiva: A histologic analysis of 204 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:466–70. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90212-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg MS, Glick M. Burket's oral medicine: Diagnosis and treatment. 10th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Denker; 2003. pp. 138–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rose LF, Mealey BL, Genco RJ, Cohen DW. Periodontics: Medicine, surgery, and implants. 2nd rev ed. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Mosby; 2004. p. 882. [Google Scholar]