Abstract

Glaucoma is an optic neuropathy that affects 60 million people worldwide. The main risk factor for glaucoma is increased intraocular pressure (IOP), this is currently the only target for treatment of glaucoma. However, some patients show disease progression despite well-controlled IOP. Another possible therapeutic target is the extracellular matrix (ECM) changes in glaucoma. There is an accumulation of ECM in the lamina cribrosa (LC) and trabecular meshwork (TM) and upregulation of profibrotic factors such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), collagen1α1 (COL1A1), and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA). One method of regulating fibrosis is through epigenetics; the study of heritable changes in gene function caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence. Epigenetic mechanisms have been shown to drive renal and pulmonary fibrosis by upregulating profibrotic factors. Hypoxia alters epigenetic mechanisms through regulating the cell's response and there is a hypoxic environment in the LC and TM in glaucoma. This review looks at the role that hypoxia plays in inducing aberrant epigenetic mechanisms and the role these mechanisms play in inducing fibrosis. Evidence suggests that a hypoxic environment in glaucoma may induce aberrant epigenetic mechanisms that contribute to disease fibrosis. These may prove to be relevant therapeutic targets in glaucoma.

1. Introduction

Glaucoma is an optic neuropathy that affects approximately 60 million people worldwide [1]. In glaucoma, the retinal ganglion cell axons are irreversibly lost through a number of factors that combine to create the overall disease profile [2]. The factors that contribute to the disease include, but are not limited to: increased intraocular pressure (IOP), age, genetic mutations, and reduced ocular perfusion pressure (OPP) [3–7].

Within the body, there is a normal process of wound healing and scarring, however, when this process is allowed to continue unchecked, connective tissue fibrosis occurs [8, 9]. In glaucoma, fibrosis is known to occur as a build-up of extracellular matrix (ECM) materials in the trabecular meshwork (TM) at the anterior of the eye [10–12], and in the lamina cribrosa (LC) at the optic nerve head (ONH) [13–15]. This mechanism of fibrosis plays a role in the disease progression. When the TM becomes clogged with ECM, the fluid within the eye, the aqueous humor (AH) cannot easily exit via its normal pathway and the pressure within the eye subsequently increases. This increase in intraocular pressure (IOP) is one of the main risk factors associated with the progression of glaucoma [4, 16] and is currently the only target for treatment in clinical use [17]. Following the increased IOP, structural damage (cupping) occurs at the optic nerve head which is associated with the loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGC) and the loss of vision seen in glaucoma [18, 19]. The lamina cribrosa is a fenestrated region of the ONH through which the nerves travel to the brain [2]. In glaucoma, there is backward bowing of the LC, and this likely puts pressure on the optic nerves, compressing them, which then leads to loss of vision [2, 20]. This damage at the ONH region is associated with an accumulation of ECM molecules at the lamina cribrosa [4, 14, 15, 21, 22].

There are a number of profibrotic factors that have been found to have increased levels in the AH and TM of glaucomatous eyes. These include the cytokine transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) [23], the matricellular proteins thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) [24], and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) [25]. The roles of TGFβ and CTGF in fibrosis are well established [26–40]; TGFβ acts through Smad proteins to activate ECM proteins such as collagen and PAI-1 to drive fibrosis [41–44]. TGFβ binds to two different serine threonine kinase receptors—Type I and Type II. The Type II receptor is constitutively active and when a ligand binds to this receptor, it complexes with and phosphorylates the Type I receptor—this then phosphorylates Smad proteins which translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene transcription [45]. TGFβ is a known regulator of CTGF which acts as a downstream mediator for TGFβ [26, 27, 32, 46]; however, this mechanism is poorly understood.

These factors have been shown to be involved in ECM production [35, 47, 48], and as CTGF and TGFβ are present in the AH of human eyes [23, 25], it is possible that they drive the production of ECM in the TM and at the LC. As previous work from our group has shown, there are increased levels of both TGFβ1 and TSP-1 in the LC cells of glaucomatous eyes [49] and increased levels of CTGF in the AH of glaucomatous eyes affecting the TM [25]. Further, it has been shown in a number of fibrotic diseases that TGFβ plays a role in mediating fibrosis and causes an increase in ECM deposition [37, 50, 51]. Studies show that the same is true in the process of glaucoma—increased levels of TGFβ lead to increased ECM deposition in the TM and LC of glaucomatous eyes [51].

In an attempt to combat fibrosis, a number of therapeutic approaches have been studied. Baricos et al. showed that TGFβ1 inhibited ECM degradation, and blocking TGFβ1 using an anti-TGFβ1 antibody increased the degradation of ECM in human mesangial cells (HMCs) [34]. Further, a study of glomerulosclerosis in rat models demonstrated that an anti-TGFβ antibody significantly reduced fibrosis. This study demonstrated decreased mRNA expression of TGFβ isoforms and collagen type III in the presence of the antibody and showed a reduction in the level of fibrosis and sclerosis seen in the kidney [52]. It was shown that transfecting TM cells with small interfering RNA (siRNA) for CTGF inhibited TGFβ2 induced upregulation of CTGF and fibronectin [47]. A recombinant monoclonal neutralizing antibody (mAb) to human TGFβ2 was shown to significantly improve the outcome of glaucoma filtration surgery in a rabbit model of conjunctival scarring [53]. Work by our lab has shown that a humanized monoclonal anti-CTGF antibody FG-3019 was able to effectively block ECM production in LC and TM cells treated with AH samples from pseudoexfoliation glaucoma (PXFG), primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), and hydrogen peroxide, as shown by a significant reduction in the expression of profibrotic genes [54].

TSP1 has been shown to induce the active form of TGFβ by inducing its dissociation from a protein that binds to and keeps it, in its latent, inactive form, thereby regulating its pathway [55]. This can result in the induction of a fibrotic phenotype through modulation of TGFβ activity [55]. A study in mice demonstrated that knocking out TSP1 significantly lowered IOP compared to wild type mice and that this may be due to altered ECM and aqueous humour outflow in the knockout mice [56].

However, there is another method by which fibrosis may be regulated, and this is through epigenetics. Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene function caused by mechanisms other than changes in the underlying DNA sequence [57]. It involves DNA methylation [58] and histone modifications including acetylation/deacetylation and methylation [59]. It has been proposed that these epigenetic processes play a role in the progression of fibrosis in a number of diseases [60–62] (Figure 1). Previously, it has been shown that epigenetic mechanisms can influence the activity of TSP1 in cancers [63, 64], so it is likely that there may be a similar effect in fibrotic disease. Further, senescent myofibroblast resistance to apoptosis has been linked to both global and locus-specific histone modifications like methylation and acetylation [65]. Micro-RNAs (miRNAs) have been established as regulators of fibrosis in cardiac, kidney, and lung fibrosis [66–68]. It has recently been demonstrated that epigenetic mechanisms may play a role in the regulation of miRNAs and that miRNAs use epigenetic mechanisms to mediate their downstream effects in cardiovascular disease and pulmonary fibrosis [69–71].

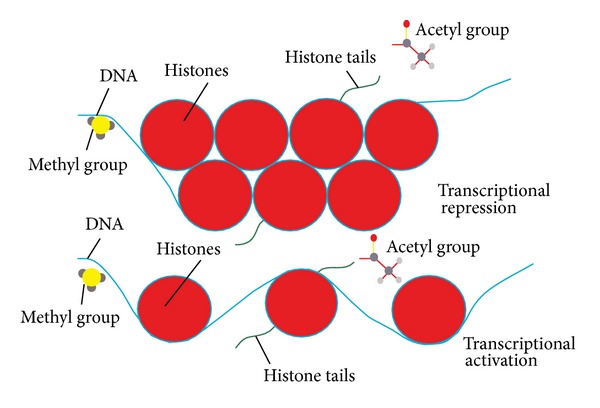

Figure 1.

Epigenetic mechanisms. DNA is wrapped around proteins called histones; this forms the core DNA package called the nucleosome. When the DNA is tightly wrapped, transcription factors cannot bind and transcription is repressed. When the DNA is more loosely wrapped, transcription is more active as transcription factors can bind. DNA methylation is when a methyl group is added to the DNA strand and is associated with transcriptional repression [58]. Histone acetylation is the addition of acetyl groups to the histone tails and this is associated with transcriptional activation. Histone deacetylation is the removal of acetyl groups which is associated with transcriptional repression [59].

There is evidence of a hypoxic environment in glaucomatous eyes, both in the AH and at the ONH. Oxidative stress markers have been found in the AH of glaucomatous eyes [72] and a study by our laboratory showed that LC cells from glaucomatous donors show increased markers of oxidative stress (increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)) and compromised antioxidant activity [73]. A hypoxic environment has also been shown in studies that demonstrated the presence of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) in the ONH, which is an indicator of hypoxia [74]. Hypoxia has been shown to induce an epigenetic response which regulates the cellular response to the hypoxic insult [75]. The induction of aberrant epigenetic modifications could potentially be through the hypoxic environment caused by the oxidative stress present in glaucomatous eyes.

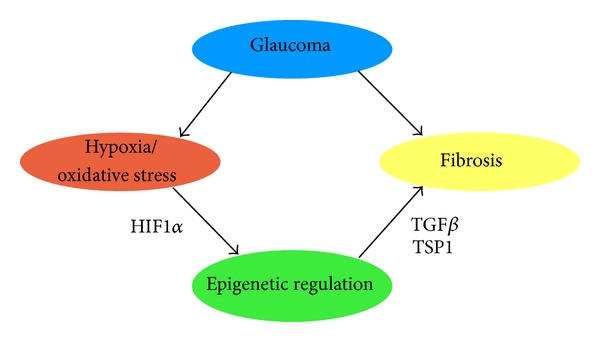

TGFβ, TSP-1, and a hypoxic environment can contribute to the disease pathogenesis of glaucoma and as there is a role for epigenetics in each of these, we will look at the epigenetic mechanisms that may be a part of the overall process (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The potential role of hypoxia and epigenetics in the fibrosis seen in glaucoma. The hypoxic environment in glaucoma [74] may cause the epigenetic profile of the cells to change bringing about a more fibrotic phenotype [61, 75].

2. TGFβ

2.1. TGFβ and Fibrosis

The TGFβ family of cytokines contains a number of multifunctional proteins that are involved in the regulation of a variety of gene products and cellular processes [13, 48, 87–89]. There are three isoforms of TGFβ (1, 2, and 3) and each of these are encoded by a different gene [90]. Members of this family are involved in inflammation, wound healing, and ECM production and accumulation, among others [38, 90]. TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 have been shown to be the predominant isoforms in the eye; in the ONH and the AH [91, 92]. TGFβ1 has been found to be elevated in PXFG, and it plays a significant role in extracellular matrix formation and accumulation in PEX syndrome [23, 93]. TGFβ2 levels have been found to have been increased in POAG [92].

The TM plays an integral role in the outflow pathway through which the aqueous humor leaves the eye. In glaucoma, the TM becomes clogged with ECM molecules [10–12] preventing the AH from being drained and creating an increase in intraocular pressure. Studies demonstrated that TGFβ acts through a number of pathways in the TM which leads to increased ECM deposition. Using exogenous TGFβ, it has been shown that the process takes place in 4 mechanisms; it increases the synthesis of ECM molecules in TM cells [51]; it increases the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 which prevents the activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that play a role in degrading ECM [51]; it increases the transglutaminase-mediated irreversible cross-linking of ECM components by TM cells [94]; and it inhibits the proliferation of TM cells [95]. Treatment of TM cells with TGFβ2 stimulates the expression of ECM genes including collagens, fibrillin, laminin, and elastin. TGFβ2 treatment can also increase the expression of fibronectin and PAI-1 [38, 51].

There is an increase in TGFβ2 levels in the ONH region of the eye; this is mostly localised to the astrocytes present in the nerve bundles in the LC [96]. TGFβ is also able to induce TSP1 which in turn activates TGFβ [24]. In the ONH, the ECM usually provides a frame and resilience for the nerves [97], however, in glaucoma, the ECM is altered by basement membrane thickening along the lamina cribrosa beams and also changes in collagen and elastin fibres within the beams [21]. TGFβ2 induces the synthesis of collagens and fibronectin [38, 51], all of which could contribute to the thickening of the basement membrane. It has been shown that TM cells secrete endogenous TGFβ1 [98], and it has also been demonstrated that exogenous TGFβ increases the synthesis and deposition of ECM proteins in LC cells, namely, fibronectin, collagens, elastin, and PAI-1 [96], so it is likely that endogenous TGFβ has a similar effect in these cells. Therefore, an increase in the amount of endogenous TGFβ secreted from the cells could increase ECM deposition at the TM. Work from our lab has shown that TGFβ1 is increased in glaucomatous LC cells in comparison to normal LC cells [49] and treatment of normal LC cells with exogenous TGFβ1 upregulated profibrotic genes such as CTGF, collagen I, and thrombospondin [99]. The use of glaucomatous-like stimulus (cyclical mechanical strain—cell stretch and a hypoxic environment—1% O2) upregulated genes associated with the ECM, such as CTGF, Collagen I, Elastin, TSP-1 macrophage migration inhibitory factor 1 (MIF), discoidin domain receptor family member 1 (DDR1/TrkE), and Insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor (IGFR2) seen in the LC region of glaucoma [84, 100].

There are a number of anti-TGFβ therapies in research and clinical trials; one such therapy is SB-431542. This is an inhibitor of the TGFβ Type I Receptor kinase activity and so an inhibitor of the TGFβ pathway. A study on the inhibition of TGFβ1-induced ECM using this therapy demonstrated that SB-431542 decreased TGFβ1-induced upregulation of fibronectin and collagen1a1 in a renal epithelial carcinoma cell line, both of which are ECM proteins [101]. A second study by Mori et al. similarly showed that SB-431542 prevented the TGFβ-induced stimulation of collagen, fibronectin, and CTGF in skin fibroblasts [102]. The TGFβ2 antibody CAT-152 has been shown to reduce collagen deposition in the subconjunctival following subconjunctival glaucoma surgery and improved surgical outcome in rabbits [103].

2.2. Epigenetic Control of TGFβ Expression

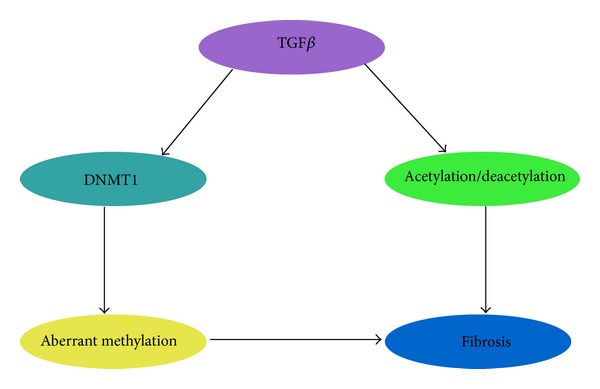

TGFβ has also been demonstrated to be regulated through epigenetic processes including DNA methylation and histone acetylation/deacetylation and methylation [76, 77, 104] (Figure 3). Alterations in the histone status of promoters of target genes may lead to a difference in the TGFβ-mediated transcription profile, and so they may determine the cell's response to TGFβ. A number of studies have shown that altered histone modifications can affect TGFβ functions within the cell [77]. The acetylation/deacetylation of histones can determine how TGFβ is able to induce a cell response to stimuli [105]. This was demonstrated in the case of corneal fibroblasts, in the normal process of wound healing, these cells transition from a proinflammatory to a profibrotic phenotype. The acetylation status of corneal fibroblasts was examined and it was found that TGFβ partially inhibited histone acetylation. This was reversed by a histone deacetylase inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA), which also reversed TGFβ-induced upregulation of profibrotic factors. Therefore, the modification of histone acetylation in corneal fibroblasts was involved in TGFβ regulation of cell transition to a profibrotic state [77]. A study by the same authors showed that HDAC inhibitors TSA and sodium butyrate (NaBu) blocked the TGFβ-induced upregulation of αSMA and collagen I in corneal stromal cells [106]. Conversely, Inoue et al. demonstrated that Smad-2 and -3 acetylation by the histone acetyltransferases CBP/P300 were enhanced by TGFβ in renal and liver cell lines [78]. This demonstrates that TGFβ plays a diverse role in the epigenetic regulation of fibrosis by both histone acetylation and histone deacetylation to drive fibrosis.

Figure 3.

Epigenetic regulation of the TGFβ pathway. TGFβ has been shown to upregulate the expression of DNMT1 which causes aberrant methylation [76] leading to a more fibrotic phenotype. Furthermore, TGFβ has been shown to decrease acetylation in corneal fibroblasts causing them to remain active and leading to fibrosis [77]. In contrast to its role in corneal fibroblasts, TGFβ enhances Smad 2/3 acetylation leading to increased activity of these Smads [78].

A further example of how histone acetylation/deacetylation can regulate TGFβ activity was seen in corneal fibroblasts treated with TSA demonstrated inhibition of TGFβ-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and myofibroblast differentiation [104].

Bruna et al. showed that TGFβ induces proliferation in one cell line (U373MG) of glioblastoma cells, but inhibits it in another (U87MG) and this is connected to TGFβ induced platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGFB). This result can be explained by the methylation status of PDGFB in the two cell lines. In one of the cell lines (U87MG), the PDGFB promoter was methylated, which blocked TGFβ-Smad signalling in this cell line. However, in the other cell line (U373MG), the promoter was not epigenetically suppressed and so TGFβ-Smad signalling was active. Therefore, the DNA methylation status of the cells is able to determine if the cell response is controlled by TGFβ activity [89]. Furthermore, the TGFβ signalling pathway has been shown to be suppressed through methylation. A number of genes were analysed and were shown to be methylated; these genes include TGFβ receptor 2 (TGFβR2) and TSP-1. Treating the cells with DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) (responsible for the transfer of methyl groups to the DNA) inhibitors increased the TGFβ pathway activity [76].

3. Thrombospondin

3.1. Thrombospondin-1 and TGFβ

Thrombospondin-1 is a matricellular, multifunctional protein that is expressed by cell types involved in wound healing. It is known to regulate cellular events in tissue repair, including cell adhesion [107], apoptosis [108], ECM expression, and organization through modulation of growth factors [109–111]. TSP1 has been shown, by our lab, to be increased in glaucomatous LC cells compared to normal LC cells [49], and it has also been demonstrated that TSP1 is increased in glaucomatous TM cells [24]. It has been shown to be expressed at increased levels in renal tissues undergoing fibrosis [110]. In a model of renal fibrosis, it was found that TSP1 is an important mediator of the disease, and its knockout reduced renal inflammation and fibrosis [112].

TGFβ is secreted from cells in a latent form which associates with the latency-associated peptide (LAP) [113]. Dissociation of TGFβ from LAP can be induced by TSP1, and this step is necessary for the activation of TGFβ [109]. TGFβ activation by TSP1 is achieved through a conformational change and is required for the regulation of the TGFβ signalling pathway [114]. TSP1-TGFβ binding does not affect TGFβ activity; this is possibly because TSP1 may play a role in aiding TGFβ presentation to cell surface receptors [115].

Studies have shown that TSP1 activates TGFβ secreted from a number of cell types; endothelial cells, mesangial cells, and cardiac fibroblasts [111, 116, 117]. It has also been demonstrated that TSP1 activates TGFβ in fibrotic disease [118]. While activation of TGFβ by TSP1 is necessary during development to give a normal phenotype [55], it is very likely that the main role for TSP1 in regulating TGFβ activation is during the processes of injury, stress, and in pathological conditions. In glaucoma, it is likely that TSP1 is necessary for TGFβ activity, as it is present in high levels in glaucomatous TM [24]. Further, a number of studies have demonstrated that treating TM cells with glaucomatous-like stimuli (TGFβ, cyclical stretch) increases TSP1 in these cells [51, 99, 100]. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that knocking out TSP1 in mice results in a significantly lower IOP when compared to wild type [56]. This reduction in IOP was attributed to a change in the ECM of these mice and to an increase in the rate of aqueous turnover. These data suggest that TSP1 plays a role in both glaucoma and in the regulation of ECM.

3.2. TSP1 and Epigenetics

There are also methods by which TSP1 itself is regulated in the disease context. Aberrant TSP1 methylation has been seen to effect TSP1 regulation of TGFβ in some cancers. In colorectal cancer, TGFβ inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis of epithelial calls. In this form of cancer, TGFβ acts as a tumour suppressing pathway in the initial disease stages [63]. As previously discussed, TSP1 regulates the TGFβ pathway by activating TGFβ [119]. In colorectal cancer, TSP1 has been found to be aberrantly methylated, and it is thought that it may promote tumorigenesis [63]. As it is known that the TGFβ pathway is regulated by TSP1, it has now been hypothesised that TSP1 promotes the formation of tumours through inhibiting the TGFβ pathway when its methylation status is altered. For example, Rojas et al. demonstrated that the hypermethylation of the TSP1 promoter in colorectal cancer suppressed TSP1 mRNA and protein expression. The reduced levels of TSP1 inhibited the activation of TGFβ in the disease and so suppressed the TGFβ signalling pathways which are beneficial in the first stages of disease. Another study of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma demonstrated that while TSP1 promoter methylation affected the mRNA and protein levels of thrombospondin 1, there were no significant effects on TGFβ expression, although a nonsignificant decrease of active TGFβ was seen in patients with TSP1 hypermethylation [64] indicating that the methylation of TSP1 causes downregulation of TSP1 and therefore decreased active TGFβ.

4. Hypoxia

4.1. Hypoxia and Glaucoma

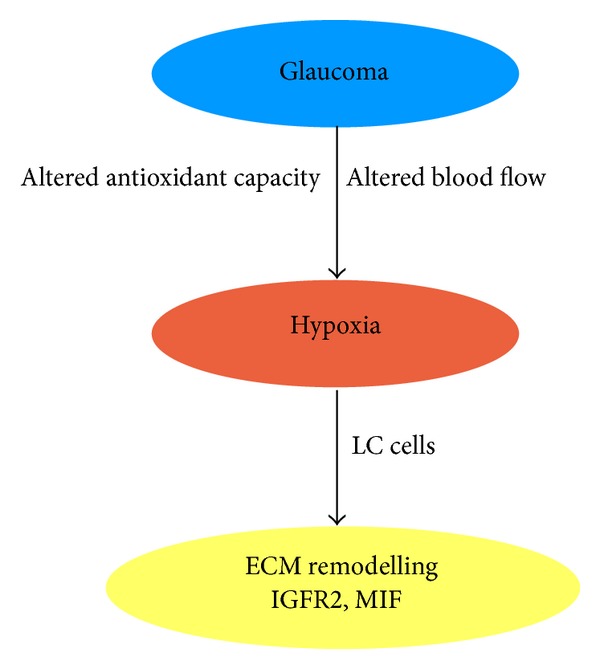

Hypoxia is a state in which there is not enough oxygen entering the tissues for them to function as normal. It is linked to age as a natural feature in many organs [120]. However the cellular response to hypoxia may result in the increased expression of survival factors [75]. There is evidence that there is a hypoxic environment present in glaucoma [74], and that this hypoxic state induces retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death which is part of the disease pathogenesis [121]. Our lab has also shown evidence of oxidative stress in glaucomatous LC cells and a decreased capacity of the cells to counteract the oxidative stress [73]. It has been shown that ocular blood flow is reduced in patients with glaucoma [79–81, 122, 123], and specifically in those in which the disease is progressing. A decrease in blood flow could lead to a decreased level of oxygen—giving a hypoxic state [82]. Increased IOP and decreased ocular perfusion pressure [4–6, 81, 83] can both effect the ocular blood flow, and so the hypoxic environment and the oxidative stress may be a result of increased IOP seen in glaucoma [82, 124]. Following from this, it has been found that a fluctuating blood flow is likely to be a cause of glaucomatous damage. Further, work from our laboratory demonstrated that in vitro hypoxia can cause LC cells to produce genes involved in ECM production and remodelling including insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor (IGFR2) and macrophage migration inhibitory factor 1 (MIF) (Figure 4). The HIF families are the key regulators of the cell's adaptive response to hypoxia, and they control the expression of many genes involved in many cell processes, including fibrosis [125, 126]. HIF1α regulates gene expression through hypoxia response elements (HRE) present in the promoter regions of target genes. Hung et al. identified a HRE in the TGFβ1 promoter; this likely allows it to be regulated by hypoxia [86].

Figure 4.

Hypoxia induces the expression of ECM remodelling genes in LC cells. It has been hypothesized that the increased IOP in glaucoma causes the blood flow to the eye to be altered, and this may be a cause of the hypoxic environment seen in glaucomatous eyes [79–83]. In addition to the altered blood flow, our group has shown that glaucomatous LC cells have decreased antioxidant capacity [73]. We have also shown that hypoxia can induce increased expression of ECM remodelling genes such as insulin-like growth factor 2 receptor (IGFR2) and macrophage migration inhibitory factor 1 (MIF) in LC cells [84].

It is believed that RGC death may be caused by a hypoxia-induced apoptotic pathway [74, 121]. Hypoxic states induce the expression of HIF1α, which is responsible for the transcriptional responses that allow cells to adapt to a hypoxic environment [75]. Tezel and Wax conducted a study where they found evidence of increased HIF1α expression in the ONH of glaucomatous eyes [74]. Regions of HIF1α expression indicate areas of decreased oxygen and so hypoxic stress, which suggests that there is tissue hypoxia in glaucoma and that this plays a role in the disease. Also, areas of HIF1α expression were also found to correlate to areas of visual field defects in patients [74].

4.2. Hypoxia and Fibrosis

A role for hypoxia in fibrosis has been suggested in different experimental models such as adult wound repair [127] and cirrhosis [128]. It has been shown that hypoxia up-regulates collagenase IV expression in cardiomyocytes [129], and increases interstitial collagen in renal tubulointerstitial cells, while decreasing collagen IV expression [130]. A study by Corpechot et al. demonstrated that hypoxia in hepatic stellate cells may directly affect the quantitative and qualitative change in the ECM during liver fibrogenesis [128]. As mentioned before, collagens are ECM proteins and so the upregulation of collagens leads to an increase in ECM build-up. Along with this, it has also been demonstrated that hypoxia can mediate the induction of TGFβ mRNA in a hepatoma cell line [131] and in dermal fibroblasts [132]. It has been hypothesised that hypoxia may act in converting TGFβ from its latent form to its active form [133] as there is a HRE in the TGFβ1 promoter [86], which allows it to be regulated by hypoxia.

In tubulointerstitial cells, it is believed that altered microvasculature brings about a hypoxic environment that causes a fibrotic response “the chronic hypoxia hypothesis” [134]. As mentioned before, there is altered blood flow in glaucoma [82], and this may be a similar mechanism to that seen in the tubulointerstitial cells. In tubular epithelial cells, hypoxia has been seen to induce changes in expression of genes that play a role in cell adaptation to stimuli [135]. Hypoxia has been shown to induce the expression of fibrogenic factors including TGFβ and angiogenic factors including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [136]. The cell's response to hypoxia acts with other fibrogenic stimuli to add to the fibro-vascular response, as well as inducing its own changes [137].

Hypoxia has also been shown to promote a more fibrotic phenotype in fibroblasts, which are ECM-producing cells [137]. It does this by increasing proliferation, and enhancing cell differentiation and contraction. It also alters the metabolism of the ECM and upregulates proteins associated with matrix production [138] and acts to decrease expression of proteins that degrade the ECM, such as matrix metalloproteinases [133]. There is evidence that hypoxia may also be involved in suppressing the apoptosis of fibroblasts [139]. A study by Zhang et al. showed that hypoxia increases the TSP1 pathway that activates TGFβ signalling in human umbilical vein endothelial cells [140]—suggesting that hypoxia may affect the expression of TGFβ through a number of regulatory processes. It was demonstrated that HIF1α could induce the expression of TSP1 in cells grown in hypoxic conditions. This was achieved through HRE binding near the transcription starting site, as HIF-1α was demonstrated to bind to this site in a hypoxic environment [141]. HIF1α has been shown to be the most active in regulating gene expression associated with the hypoxic response [136]. It may play a role in the promotion of fibrosis through the induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in which cells change from an epithelial phenotype to a more fibrotic, myofibroblast phenotype [136].

4.3. Hypoxia and Epigenetics

A study by Watson et al. showed that chronic hypoxia in prostate cells induced an alteration in DNA methylation and histone acetylation. In the absence of HIF1α which is responsible for downstream mediation of the hypoxic phenotype, epigenetic alterations may take over this role in establishing and maintaining the hypoxia related phenotype [75]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that HIF may require epigenetic mechanisms to aid in the initiation and maintenance of the cell phenotype in a hypoxic environment. In the presence of oxygen, HIF1α is regulated through hydroxylation, ubiquitination, and degradation by prolyl hydroxylase enzymes (PHD) [142]. In the absence of oxygen, this is inhibited which allows for HIF1α stabilisation and activation [143]. HIF1α regulates gene expression through hypoxia response elements (HRE) present in the promoter regions of target genes [144]. This binding can be affected through DNA methylation and histone modification, which may maintain a favourable chromatin conformation around HRE sites (Figure 5).

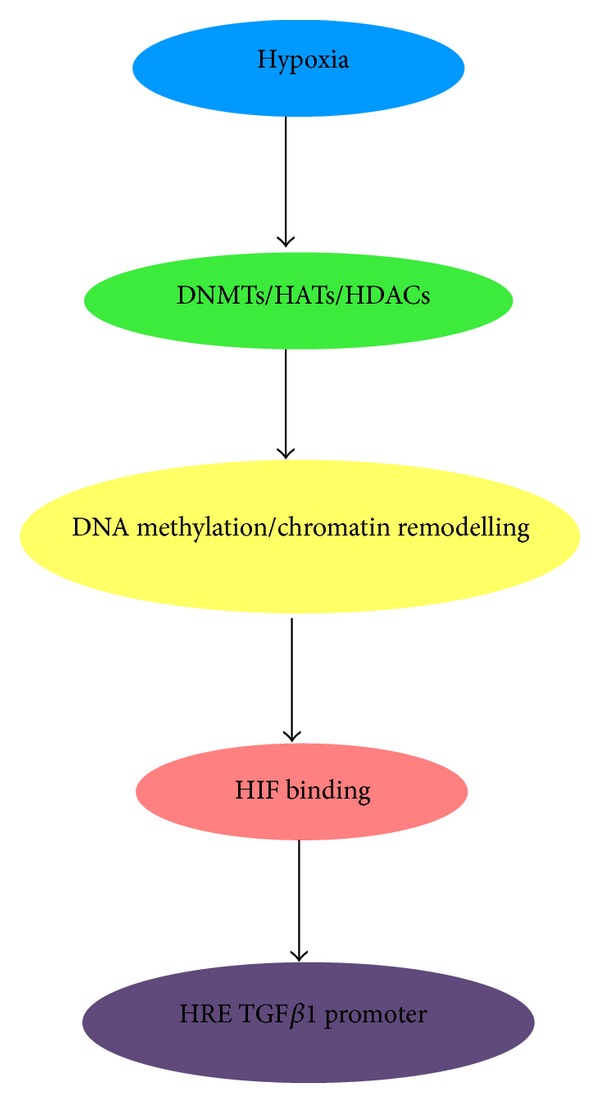

Figure 5.

Epigenetic changes allow HIF binding to HIF response elements (HREs). A hypoxic environment within a cell can cause normal epigenetic mechanisms to be changed, altering the level of DNA methylation and/or modifying chromatin conformation allowing HIF1α to bind to the HRE on the gene [85]. The TGFβ1 promoter has been previously shown to contain a HRE [86], and so hypoxia can alter TGFβ1 expression through HIF1α.

The creb binding protein/p300 coactivator (CBP/P300) is a histone acetyltransferase (HAT) that functions by adding acetyl groups to histones and driving gene transcription. It is known to associate with HIF1α to coactivate hypoxia-inducible genes [145]. This association can be affected by histone deacetylases (HDACs) and also by HDAC inhibitors. HDAC3 is a binding partner of HIF1α that aids in the regulation of its stability during the hypoxic response [146]. HIF1α binding may also be affected by the methylation of CpG sites at the HRE. DNA hypomethylation, which is typically associated with more active gene transcription, has been shown to be induced by tumour hypoxia [147].

Additionally, there is also evidence to suggest that epigenetic modifications induced by hypoxia play a role independent of HIF. Modified histones in this case can directly interact with promoter regions of hypoxia-inducible genes [147, 148]. Robinson et al. showed that DNA hypermethylation induced by hypoxia in human pulmonary fibroblasts is associated with the development of a profibrotic phenotype. Thy-1 is a glycoprotein that can affect intracellular signalling pathways. Its absence on fibroblasts is associated with a myofibroblast phenotype. This group showed that hypermethylation of the Thy-1 promoter was induced by hypoxia and led to a myofibroblast phenotype and treatment with 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine caused an increase in Thy-1 expression [61].

5. Epigenetics in Ocular Diseases

There are a number of studies that have suggested a role for epigenetics in ophthalmology. A study of monozygotic and dizygotic twins with discordant age-related macular degeneration (AMD) showed differential methylation of the promoter regions of 231 genes [149]. A further study of AMD conducted bisulfite sequencing of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE); there was hypermethylation of the promoter regions of two glutathione S transferase (GTSM) isoforms, which resulted in decreased mRNA and protein [150]. Importantly, GTSMs are involved in defending against ROS, which have been shown by our lab to be upregulated in glaucomatous cells [73]. The hypermethylation of the αA-crystallin (CRYAA) promoter also coincided with downregulation of mRNA and protein in age-related cataract [151]. Zhou et al. showed that methylation of the collagen 1a1 (COL1A1) promoter could play a role in the development of myopia [152]. In a mouse model of optic nerve crush (ONC), there was an increase in the nuclear localisation and activity of HDACs 2 and 3 and a corresponding increase in histone 4 deacetylation; this was associated with RGC death [153]. Further, the silencing of the Fem1cR gene by histone deacetylation has been connected to RGC death in a DBA/2J mouse model of glaucoma [154]. In addition to this, there is a role for epigenetics in diabetic retinopathy; it has been shown that in streptozotocin (STZ) treated rats kept under poor glycemic control, there is increased HDACs 1, 2, and 8 in the retina and retinal endothelial cells [155].

6. Future Perspectives on Epigenetic Therapies in Glaucoma

Currently there are a number of epigenetic treatments being used to treat myelodysplastic syndromes and cutaneous T-Cell lymphoma. DNMT inhibitors Azacitidine and Decitabine are used to treat myelodysplastic syndromes [156]. These DNMT inhibitors cause DNA hypomethylation which has resulted in an improved survival rate for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. These drugs were well tolerated in patients during clinical trials. This indicates that these agents may be good candidates for glaucoma therapies, if it can be demonstrated that there is aberrant DNA methylation occurring in glaucoma.

HDAC inhibitors such as Vorinostat and Romidepsin are in use to treat cutaneous T-Cell lymphoma [157]. These drugs are used when a patient relapses and other treatments are not effective. Vorinostat is a pan-HDAC inhibitor, and so inhibits class I, II, and IV HDACs. There are some minor side-effects associated with this drug, although it is overall well-tolerated. Romidepsin is similarly a pan-HDAC inhibitor also targeting class I, II, and IV HDACs. Some minor side effects were found in clinical trials but the treatments proved very effective. Similarly, if it can be shown that the mechanisms of histone acetylation/deacetylation are altered in glaucoma, these treatments may be an option for glaucoma. Further, it has been demonstrated that HDAC inhibitors may alter DNA methylation levels [158–161]. Sanders et al. found that treating rat lung fibroblasts with TSA demethylated previously hypermethylated sites of the Thy-1 promoter region [161]; TSA also upregulated methyltransferase activity in these cells [161]. Another study demonstrated that TSA reduced the global DNA methylation of cancer cell lines and downregulated the DNMT1 protein and also altered DNMT1 activity [160]. This demonstrates that there may be a synergistic role for these epigenetic mechanisms, and so combination therapies may be beneficial in treating aberrant epigenetic mechanisms in fibrotic diseases.

As there are already epigenetic treatments in clinical use, research into the role of epigenetics in glaucoma may offer potential new avenues of therapy to treat the disease. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, increased IOP is the only target for treatment, and discovering more about the role of epigenetics may provide a target for the underlying causes of the disease.

7. Conclusion

Glaucoma is a multifactorial disease in which all of the above elements play a role. What we can take from the current information is that there is still much to be discovered about the different aspects of the disease pathogenesis. Of particular importance is the role of epigenetics within some of the contributing factors to the disease and how the overall epigenetic profile of a glaucomatous eye differs from that of a normal eye. When taking into account the roles of TGFβ and TSP1 in glaucoma, it is clear that these have an epigenetic aspect which contributes to the activity of these proteins in a number of diseases, and so it may play a part in how TGFβ and TSP1 control the cellular response in the glaucomatous environment.

This also links to the role that hypoxia plays in regulating the epigenetic profile of glaucoma, as hypoxia also plays a role in the regulation of TGFβ and TSP1. The hypoxic and oxidative stress environment found in glaucoma is thought to play a significant part in the disease pathogenesis through HIF1α and the induction of aberrant epigenetic modification. Epigenetic alterations allow a cell to adapt to the hypoxic environment and therefore change its phenotype—possibly to a profibrotic one in the context of glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Health Research Board Grants HRB HRA POR_2010-129 and HRB HRA POR_2011-13.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Quigley H, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA. Neuronal death in glaucoma. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 1999;18(1):39–57. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao KN, Nagireddy S, Chakrabarti S. Complex genetic mechanisms in glaucoma: an overview. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2011;59:S31–S42. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.73685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leske MC, Connell AMS, Wu S-Y, Hyman LG, Schachat AP. Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados eye study. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1995;113(7):918–924. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100070092031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi J, Kyung HK, Jeong J, Cho H, Chang HL, Kook MS. Circadian fluctuation of mean ocular perfusion pressure is a consistent risk factor for normal-tension glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(1):104–111. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topouzis F, Wilson MR, Harris A, et al. Risk factors for primary open-angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliative glaucoma in the thessaloniki eye study. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2011;152(2):219.e1–228.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topouzis F, Wilson MR, Harris A, et al. Association of open-angle glaucoma with perfusion pressure status in the Thessaloniki Eye study. American Journal of Ophthalmolog. 2013;155(5):843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mutsaers SE, Bishop JE, McGrouther G, Laurent GJ. Mechanisms of tissue repair: from wound healing to fibrosis. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 1997;29(1):5–17. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diegelmann RF, Evans MC. Wound healing: an overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2004;9:283–289. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohen JW, Witmer R. Electron microscopic studies on the trabecular meshwork in glaucoma simplex. Albrecht von Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1972;183(4):251–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00496153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchshofer R, Welge-Lüssen U, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Birke M. Biochemical and morphological analysis of basement membrane component expression in corneoscleral and cribriform human trabecular meshwork cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006;47(3):794–801. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acott TS, Kelley MJ. Extracellular matrix in the trabecular meshwork. Experimental Eye Research. 2008;86(4):543–561. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison JC, Dorman-Pease ME, Dunkelberger GR, Quigley HA. Optic nerve head extracellular matrix in primary optic atrophy and experimental glaucoma. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1990;108(7):1020–1024. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070090122053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albon J, Karwatowski WSS, Avery N, Easty DL, Duance VC. Changes in the collagenous matrix of the aging human lamina cribrosa. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1995;79(4):368–375. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez MR, Ye H. Glaucoma: changes in extracellular matrix in the optic nerve head. Annals of Medicine. 1993;25(4):309–315. doi: 10.3109/07853899309147290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Moraes CG, Juthani VJ, Liebmann JM, et al. Risk factors for visual field progression in treated glaucoma. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2011;129(5):562–568. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaasterland DE, Ederer F, Beck A, et al. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000;130(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quigley HA, Flower RW, Addicks EM, McLeod DS. The mechanism of optic nerve damage in experimental acute intraocular pressure elevation. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1980;19(5):505–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottanka J, Johnson DH, Martus P, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Severity of optic nerve damage in eyes with POAG is correlated with changes in the trabecular meshwork. Journal of Glaucoma. 1997;6(2):123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quigley HA, Hohman RM, Addicks EM. Morphologic changes in the lamina cribrosa correlated with neural loss in open-angle glaucoma. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1983;95(5):673–691. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(83)90389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosario Hernandez M, Andrzejewska WM, Neufeld AH. Changes in the extracellular matrix of the human optic nerve head in primary open-angle glaucoma. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1990;109(2):180–188. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albon J, Purslow PP, Karwatowski WSS, Easty DL. Age related compliance of the lamina cribrosa in human eyes. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000;84(3):318–323. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.3.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inatani M, Tanihara H, Katsuta H, Honjo M, Kido N, Honda Y. Transforming growth factor-β2 levels in aqueous humor of glaucomatous eyes. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2001;239(2):109–113. doi: 10.1007/s004170000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flügel-Koch C, Ohlmann A, Fuchshofer R, Welge-Lüssen U, Tamm ER. Thrombospondin-1 in the trabecular meshwork: localization in normal and glaucomatous eyes, and induction by TGF-β1 and dexamethasone in vitro. Experimental Eye Research. 2004;79(5):649–663. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browne JG, Ho SL, Kane R, et al. Connective tissue growth factor is increased in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52(6):3660–3666. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnott JA, Nuclozeh E, Rico MC, et al. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) is a downstream mediator for TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix production in osteoblasts. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;210(3):843–852. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen MM, Lam A, Abraham JA, Schreiner GF, Joly AH. CTGF expression is induced by TGF-β in cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes: a potential role in heart fibrosis. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2000;32(10):1805–1819. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrett Q, Khaw PT, Blalock TD, Schultz GS, Grotendorst GR, Daniels JT. Involvement of CTGF in TGF-β1-stimulation of myofibroblast differentiation and collagen matrix contraction in the presence of mechanical stress. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2004;45(4):1109–1116. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gore-Hyer E, Shegogue D, Markiewicz M, et al. TGF-β and CTGF have overlapping and distinct fibrogenic effects on human renal cells. American Journal of Physiology: Renal Physiology. 2002;283(4):F707–F716. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00007.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui Y, Sadoshima J. Rapid upregulation of CTGF in cardiac myocytes by hypertrophic stimuli: implication for cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2004;37(2):477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi-wen X, Pennington D, Holmes A, et al. Autocrine overexpression of CTGF maintains fibrosis: RDA analysis of fibrosis genes in systemic sclerosis. Experimental Cell Research. 2000;259(1):213–224. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song JJ, Aswad R, Kanaan RA, et al. Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) acts as a downstream mediator of TGF-β1 to induce mesenchymal cell condensation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;210(2):398–410. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weston BS, Wahab NA, Mason RM. CTGF mediates TGF-β-induced fibronectin matrix deposition by upregulating active α5β1 integrin in human mesangial cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2003;14(3):601–610. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000051600.53134.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baricos WH, Cortez SL, Deboisblanc M, Shi X. Transforming growth factor-β is a potent inhibitor of extracellular matrix degradation by cultured human mesangial cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1999;10(4):790–795. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kottler UB, Jünemann AGM, Aigner T, Zenkel M, Rummelt C, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U. Comparative effects of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 on extracellular matrix production, proliferation, migration, and collagen contraction of human Tenon’s capsule fibroblasts in pseudoexfoliation and primary open-angle glaucoma. Experimental Eye Research. 2005;80(1):121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krummel TM, Michna BA, Thomas BL, et al. Transforming Growth Factor beta (TGF-β) induces fibrosis in a fetal wound model. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1988;23(7):647–652. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varga J, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Transforming Growth Factor β (TGFβ) causes a persistent increase in steady-state amounts of type I and type III collagen and fibronectin mRNAs in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Biochemical Journal. 1987;247(3):597–604. doi: 10.1042/bj2470597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wordinger RJ, Fleenor DL, Hellberg PE, et al. Effects of TGF-β2, BMP-4, and gremlin in the trabecular meshwork: implications for glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007;48(3):1191–1200. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu YD, Hua J, Mui A, O’Connor R, Grotendorst G, Khalil N. Release of biologically active TGF-β1 by alveolar epithelial cells results in pulmonary fibrosis. American Journal of Physiology: Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2003;285(3):L527–L539. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00298.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto T, Noble NA, Miller DE, Border WA. Sustained expression of TGF-β1 underlies development of progressive kidney fibrosis. Kidney International. 1994;45(3):916–927. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moustakas A, Heldin C. The regulation of TGFβ signal transduction. Development. 2009;136(22):3699–3714. doi: 10.1242/dev.030338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM, Koevoet W, de Bart ACW, et al. TGFβ affects collagen cross-linking independent of chondrocyte phenotype but strongly depending on physical environment. Tissue Engineering A. 2008;14(6):1059–1066. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goc A, Choudhary M, Byzova TV, Somanath PR. TGFβ- and bleomycin-induced extracellular matrix synthesis is mediated through Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226(11):3004–3013. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyazono K. TGF-β signaling by Smad proteins. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2000;11(1-2):15–22. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heldin C, Miyazono K, Dijke PT. TGF-β signalling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390(6659):465–471. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gressner OA, Lahme B, Demirci I, Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Differential effects of TGF-β on connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) expression in hepatic stellate cells and hepatocytes. Journal of Hepatology. 2007;47(5):699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Junglas B, Yu AHL, Welge-Lüssen U, Tamm ER, Fuchshofer R. Connective tissue growth factor induces extracellular matrix deposition in human trabecular meshwork cells. Experimental Eye Research. 2009;88(6):1065–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuchshofer R, Birke M, Welge-Lussen U, Kook D, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Transforming growth factor-β2 modulated extracellular matrix component expression in cultured human optic nerve head astrocytes. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2005;46(2):568–578. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirwan RP, Wordinger RJ, Clark AF, O’Brien CJ. Differential global and extra-cellular matrix focused gene expression patterns between normal and glaucomatous human lamina cribrosa cells. Molecular Vision. 2009;15:76–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Overall CM, Wrana JL, Sodek J. Independent regulation of collagenase, 72-kDa progelatinase, and metalloendoproteinase inhibitor expression in human fibroblasts by transforming growth factor-β . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264(3):1860–1869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fleenor DL, Shepard AR, Hellberg PE, Jacobson N, Pang I, Clark AF. TGFβ2-induced changes in human trabecular meshwork: implications for intraocular pressure. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2006;47(1):226–234. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma L, Jha S, Ling H, Pozzi A, Ledbetter S, Fogo AB. Divergent effects of low versus high dose anti-TGF-β antibody in puromycin aminonucleoside nephropathy in rats. Kidney International. 2004;65(1):106–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cordeiro MF, Gay JA, Khaw PT. Human anti-transforming growth factor-β2 antibody: a new glaucoma anti- scarring agent. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1999;40(10):2225–2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallace DM, Clark AF, Lipson KE, Andrews D, Crean JK, O’Brien CJ. Anti-connective tissue growth factor antibody treatment reduces extracellular matrix production in trabecular meshwork and lamina cribrosa cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2013;54(13):7836–7848. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sweetwyne MT, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin1 in tissue repair and fibrosis: TGF-β-dependent and independent mechanisms. Matrix Biology. 2012;31(3):178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haddadin RI, Oh DJ, Kang MH, et al. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1)-null and TSP2-null mice exhibit lower intraocular pressures. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(10):6708–6717. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu C-T, Morris JR. Genes, genetics, and epigenetics: a correspondence. Science. 2001;293(5532):1103–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5532.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Auclair G, Weber M. Mechanisms of DNA methylation and demethylation in mammals. Biochimie. 2012;94(11):2202–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coward WR, Watts K, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Knox A, Pang L. Defective histone acetylation is responsible for the diminished expression of cyclooxygenase 2 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(15):4325–4339. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01776-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinson CM, Neary R, Levendale A, Watson CJ, Baugh JA. Hypoxia-induced DNA hypermethylation in human pulmonary fibroblasts is associated with Thy-1 promoter methylation and the development of a pro-fibrotic phenotype. Respiratory Research. 2012;13, article 74 doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaminski N, Allard JD, Pittet JF, et al. Global analysis of gene expression in pulmonary fibrosis reveals distinct programs regulating lung inflammation and fibrosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(4):1778–1783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rojas A, Meherem S, Kim Y, et al. The aberrant methylation of TSP1 suppresses TGF-β1 activation in colorectal cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;123(1):14–21. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guo W, Dong Z, Guo Y, Yang Z, Kuang G, Shan B. Correlation of hypermethylation of TSP1 gene with TGF-beta1 level and T cell immunity in gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Chinese Journal of Cancer. 2009;28(12):1298–1303. doi: 10.5732/cjc.009.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanders YY, Liu H, Zhang X, et al. Histone modifications in senescence-associated resistance to apoptosis by oxidative stress. Redox Biology. 2013;1(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chau BN, Xin C, Hartner J, et al. MicroRNA-21 promotes fibrosis of the kidney by silencing metabolic pathways. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(121) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003205.121ra18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature. 2008;456(7224):980–984. doi: 10.1038/nature07511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu G, Friggeri A, Yang Y, et al. miR-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207(8):1589–1597. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen K, Liao Y, Hsieh I, Wang Y, Hu C, Juo SH. OxLDL causes both epigenetic modification and signaling regulation on the microRNA-29b gene: novel mechanisms for cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2012;52(3):587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen K, Wang Y, Hu C, et al. OxLDL up-regulates microRNA-29b, leading to epigenetic modifications of MMP-2/MMP-9 genes: a novel mechanism for cardiovascular diseases. FASEB Journal. 2011;25(5):1718–1728. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-174904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dakhlallah D, Batte K, Wang Y, et al. Epigenetic regulation of miR-17∼92 contributes to the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187(4):397–405. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0888OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferreira SM, Lerner SF, Brunzini R, Evelson PA, Llesuy SF. Oxidative stress markers in aqueous humor of glaucoma patients. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004;137(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McElnea EM, Quill B, Docherty NG, et al. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and calcium overload in human lamina cribrosa cells from glaucoma donors. Molecular Vision. 2011;17:1182–1191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tezel G, Wax MB. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α in the glaucomatous retina and optic nerve head. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(9):1348–1356. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.9.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Watson JA, Watson CJ, McCrohan A, et al. Generation of an epigenetic signature by chronic hypoxia in prostate cells. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18(19):3594–3604. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matsumura N, Huang Z, Mori S, et al. Epigenetic suppression of the TGF-beta pathway revealed by transcriptome profiling in ovarian cancer. Genome Research. 2011;21(1):74–82. doi: 10.1101/gr.108803.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou Q, Yang L, Wang Y, et al. TGFβ mediated transition of corneal fibroblasts from a proinflammatory state to a profibrotic state through modulation of histone acetylation. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2010;224(1):135–143. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Inoue Y, Itoh Y, Abe K, et al. Smad3 is acetylated by p300/CBP to regulate its transactivation activity. Oncogene. 2007;26(4):500–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Emre M, Orgül S, Gugleta K, Flammer J. Ocular blood flow alteration in glaucoma is related to systemic vascular dysregulation. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2004;88(5):662–666. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.032110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kerr J, Nelson P, O’Brien C. A comparison of ocular blood flow in untreated primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 1998;126(1):42–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fuchsjäger-Mayrl G, Wally B, Georgopoulos M, et al. Ocular blood flow and systemic blood pressure in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2004;45(3):834–839. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flammer J, Konieczka K, Flammer AJ. The role of ocular blood flow in the pathogenesis of glaucomatous damage. US Ophthalmic Review. 2011;4(2):84–87. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leske MC. Ocular perfusion pressure and glaucoma: clinical trial and epidemiologic findings. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2009;20(2):73–78. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32831eef82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kirwan RP, Felice L, Clark AF, O’Brien CJ, Leonard MO. Hypoxia regulated gene transcription in human optic nerve lamina cribrosa cells in culture. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(4):2243–2255. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Watson JA, Watson CJ, Mccann A, Baugh J. Epigenetics, the epicenter of the hypoxic response. Epigenetics. 2010;5(4):293–296. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.4.11684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hung SP, Yang MH, Tseng KF, Lee OK. Hypoxia-induced secretion of TGF-beta 1 in mesenchymal stem cell promotes breast cancer cell progression. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(10):1869–1882. doi: 10.3727/096368912X657954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ho SL, Dogar GF, Wang J, et al. Elevated aqueous humour tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and connective tissue growth factor in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2005;89(2):169–173. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.044685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fuchshofer R, Welge-Lussen U, Lütjen-Drecoll E. The effect of TGF-β2 on human trabecular meshwork extracellular proteolytic system. Experimental Eye Research. 2003;77(6):757–765. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bruna A, Darken RS, Rojo F, et al. High TGFβ-Smad activity confers poor prognosis in glioma patients and promotes cell proliferation depending on the methylation of the PDGF-B gene. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(2):147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Massague J. The transforming growth factor-β family. Annual Review of Cell Biology. 1990;6:597–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pena JDO, Taylor AW, Ricard CS, Vidal I, Hernandez MR. Transforming growth factor β isoforms in human optic nerve heads. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1999;83(2):209–218. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.2.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tripathi RC, Li J, Chan FA, Tripathi BJ. Aqueous humor in glaucomatous eyes contains an increased level of TGF-β2. Experimental Eye Research. 1994;59(6):723–728. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Zenkel M, Küchle M, Sakai LY, Naumann GOH. Role of transforming growth factor-β1 and its latent form binding protein in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Experimental Eye Research. 2001;73(6):765–780. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Welge-Lüßen U, May CA, Lütjen-Drecoll E. Induction of tissue transglutaminase in the trabecular meshwork by TGF- β1 and TGF-β2. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2000;41(8):2229–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wordinger RJ, Clark AF, Agarwal R, et al. Cultured human trabecular meshwork cells express functional growth factor receptors. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1998;39(9):1575–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zode GS, Sethi A, Brun-Zinkernagel A, Chang I, Clark AF, Wordinger RJ. Transforming growth factor-β2 increases extracellular matrix proteins in optic nerve head cells via activation of the Smad signaling pathway. Molecular Vision. 2011;17:1745–1758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oyama T, Abe H, Ushiki T. The connective tissue and glial framework in the optic nerve head of the normal human eye: light and scanning electron microscopic studies. Archives of Histology and Cytology. 2006;69(5):341–356. doi: 10.1679/aohc.69.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tripathi RC, Li J, Borisuth NSC, Tripathi BJ. Trabecular cells of the eye express messenger RNA for transforming growth factor-β1 and secrete this cytokine. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1993;34(8):2562–2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kirwan RP, Leonard MO, Murphy M, Clark AF, O’Brien CJ. Transforming Growth factor-β-regulated gene transcription and protein expression in human GFAP-negative lamina cribrosa cells. Glia. 2005;52(4):309–324. doi: 10.1002/glia.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kirwan RP, Fenerty CH, Crean J, Wordinger RJ, Clark AF, O’Brien CJ. Influence of cyclical mechanical strain on extracellular matrix gene expression in human lamina cribrosa cells in vitro. Molecular Vision. 2005;11:798–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Laping NJ, Grygielko E, Mathur A, et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1-induced extracellular matrix with a novel inhibitor of the TGF-β type I receptor kinase activity: SB-431542. Molecular Pharmacology. 2002;62(1):58–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mori Y, Ishida W, Bhattacharyya S, Li Y, Platanias LC, Varga J. Selective inhibition of activin receptor-like kinase 5 signaling blocks profibrotic transforming growth factor β responses in skin fibroblasts. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2004;50(12):4008–4021. doi: 10.1002/art.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mead AL, Wong TTL, Cordeiro MF, Anderson IK, Khaw PT. Evaluation of anti-TGF-β2 antibody as a new postoperative anti-scarring agent in glaucoma surgery. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2003;44(8):3394–3401. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang L, et al. Trichostatin A inhibits transforming growth factor-beta-induced reactive oxygen species accumulation and myofibroblast differentiation via enhanced NF-E2-related factor 2-antioxidant response element signaling. Molecular Pharmacology. 2013;83(3):671–680. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.081059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ikushima H, Miyazono K. TGF-β signal transduction spreading to a wider field: a broad variety of mechanisms for context-dependent effects of TGF-β . Cell and Tissue Research. 2012;347(1):37–49. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhou Q, Wang Y, Yang L, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors blocked activation and caused senescence of corneal stromal cells. Molecular Vision. 2008;14:2556–2565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murphy-Ullrich JE, Hook M. Thrombospondin modulates focal adhesions in endothelial cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;109(3):1309–1319. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jiménez B, Volpert OV, Crawford SE, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL, Bouck N. Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nature Medicine. 2000;6(1):41–48. doi: 10.1038/71517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Crawford SE, Stellmach V, Murphy-Ullrich JE, et al. Thrombospondin-1 is a major activator of TGF-β1 in vivo. Cell. 1998;93(7):1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81460-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Daniel C, Schaub K, Amann K, Lawler J, Hugo C. Thrombospondin-1 is an endogenous activator of TGF-β in experimental diabetic nephropathy in vivo. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):2982–2989. doi: 10.2337/db07-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schultz-Cherry S, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin causes activation of latent transforming growth factor-β secreted by endothelial cells by a novel mechanism. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;122(4):923–932. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bige N, Shweke N, Benhassine S, et al. Thrombospondin-1 plays a profibrotic and pro-inflammatory role during ureteric obstruction. Kidney International. 2012;81(12):1226–1238. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gleizes P, Munger JS, Nunes I, et al. TGF-β latency: biological significance and mechanisms of activation. Stem Cells. 1997;15(3):190–197. doi: 10.1002/stem.150190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Murphy-Ullrich JE, Poczatek M. Activation of latent TGF-β by thrombospondin-1: mechanisms and physiology. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2000;11(1-2):59–69. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Murphy-Ullrich JE, Schultz-Cherry S, Hook M. Transforming growth factor-β complexes with thrombospondin. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1992;3(2):181–188. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Poczatek MH, Hugo C, Darley-Usmar V, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Glucose stimulation of transforming growth factor-β bioactivity in mesangial cells is mediated by thrombospondin-1. American Journal of Pathology. 2000;157(4):1353–1363. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64649-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhou Y, Poczatek MH, Berecek KH, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin 1 mediates angiotensin II induction of TGF-β activation by cardiac and renal cells under both high and low glucose conditions. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;339(2):633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chen Y, Wang X, Weng D, et al. A TSP-1 synthetic peptide inhibits bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 2009;61(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schultz-Cherry S, Lawler J, Murphy-Ullrich JE. The type 1 repeats of thrombospondin 1 activate latent transforming growth factor-β . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(43):26783–26788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Aalami OO, Fang TD, Song HM, Nacamuli RP. Physiological features of aging persons. Archives of Surgery. 2003;138(10):1068–1076. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.10.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chen Y, Yamada H, Mao W, Matsuyama S, Aihara M, Araie M. Hypoxia-induced retinal ganglion cell death and the neuroprotective effects of beta-adrenergic antagonists. Brain Research. 2007;1148(1):28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cherecheanu AP, Garhofer G, Schmidl D, Werkmeister R, Schmetterer L. Ocular perfusion pressure and ocular blood flow in glaucoma. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2013;13(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Butt Z, O’Brien C, McKillop G, Aspinall P, Allan P. Color Doppler imaging in untreated high- and normal-pressure open-angle glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1997;38(3):690–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Flammer J, Eppler E, Niesel P. Quantitative perimetry in the glaucoma patient without local visual field defects. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1982;219(2):92–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02173447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Halberg N, Khan T, Trujillo ME, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α induces fibrosis and insulin resistance in white adipose tissue. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(16):4467–4483. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00192-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Moon JK, Welch TP, Gonzalez FJ, Copple BL. Reduced liver fibrosis in hypoxia-inducible factor-1α-deficient mice. American Journal of Physiology: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2009;296(3):G582–G592. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90368.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Scheid A, Wenger RH, Christina H, et al. Hypoxia-regulated gene expression in fetal wound regeneration and adult wound repair. Pediatric Surgery International. 2000;16(4):232–236. doi: 10.1007/s003830050735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Corpechot C, Barbu V, Wendum D, et al. Hypoxia-induced VEGF and collagen I expressions are associated with angiogenesis and fibrogenesis in experimental cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35(5):1010–1021. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.VanWinkle WB, Snuggs M, Buja LM. Hypoxia-induced alterations in cytoskeleton coincide with collagenase expression in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 1995;27(12):2531–2542. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1995.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Orphanides C, Fine LG, Norman JT. Hypoxia stimulates proximal tubular cell matrix production via a TGF- β1-independent mechanism. Kidney International. 1997;52(3):637–647. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Patel B, Khaliq A, Jarvis-Evans J, McLeod D, Mackness M, Boulton M. Oxygen regulation of TGF-β1 mRNA in human hepatoma (HEP G2) cells. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology International. 1994;34(3):639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Falanga V, Qian SW, Danielpour D, Katz MH, Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Hypoxia upregulates the synthesis of TGF-β1 by human dermal fibroblasts. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 1991;97(4):634–637. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12483126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Behzadian MA, Wang XL, Al-Shabrawey M, Caldwell RB. Effects of hypoxia on l cell expression of angiogenesis-regulating factors VEGF and TGF-beta. Glia. 1998;24(2):216–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fine LG, Orphanides C, Norman JT. Progressive renal disease: the chronic hypoxia hypothesis. Kidney International, Supplement. 1998;53(65):S74–S78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Leonard MO, Cottell DC, Godson C, Brady HR, Taylor CT. The role of HIF-1α in transcriptional regulation of the proximal tubular epithelial cell response to hypoxia. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(41):40296–40304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kimura K, Iwano M, Higgins DF, et al. Stable expression of HIF-1α in tubular epithelial cells promotes interstitial fibrosis. American Journal of Physiology: Renal Physiology. 2008;295(4):F1023–F1029. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90209.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Norman JT, Fine LG. Intrarenal oxygenation in chronic renal failure. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2006;33(10):989–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fine LG, Norman JT. Chronic hypoxia as a mechanism of progression of chronic kidney diseases: from hypothesis to novel therapeutics. Kidney International. 2008;74(7):867–872. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Eul B, Rose F, Krick S, et al. Impact of HIF-1α and HIF-2α on proliferation and migration of human pulmonary artery fibroblasts in hypoxia. FASEB Journal. 2006;20(1):163–165. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4104fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zhang H, Akman HO, Smith ELP, et al. Cellular response to hypoxia involves signaling via Smad proteins. Blood. 2003;101(6):2253–2260. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ortiz-Masia D, et al. Induction of CD36 and thrombospondin-1 in macrophages by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and its relevance in the inflammatory process. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048535.e48535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wang GL, Jiang B, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(12):5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. A conserved family of prolyl-4-hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 2001;294(5545):1337–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1066373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and regulation of DNA binding activity by hypoxia. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(29):21513–21518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kallio PJ, Okamoto K, O’Brien S, et al. Signal transduction in hypoxic cells: inducible nuclear translocation and recruitment of the CBP/p300 coactivator by the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α . EMBO Journal. 1998;17(22):6573–6586. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Kim S, Jeong J, Park JA, et al. Regulation of the HIF-1alpha stability by histone deacetylases. Oncology Reports. 2007;17(3):647–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Shahrzad S, Bertrand K, Minhas K, Coomber BL. Induction of DNA hypomethylation by tumor hypoxia. Epigenetics. 2007;2(2):119–125. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.2.4613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Johnson AB, Denko N, Barton MC. Hypoxia induces a novel signature of chromatin modifications and global repression of transcription. Mutation Research: Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2008;640(1-2):174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wei L, Liu B, Tuo J, et al. Hypomethylation of the IL17RC promoter associates with age-related macular degeneration. Cell Reports. 2012;2(5):1151–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hunter A, Spechler PA, Cwanger A, et al. DNA methylation is associated with altered gene expression in AMD. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(4):2089–2105. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Zhou P, Luo Y, Liu X, Fan L, Lu Y. Down-regulation and CpG island hypermethylation of CRYAA in age-related nuclear cataract. FASEB Journal . 2012;26(12):4897–4902. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Zhou X, et al. Experimental murine myopia induces collagen type Iα1 (COL1A1) DNA methylation and altered COL1A1 messenger RNA expression in sclera. Molecular Vision. 2012;18:1312–1324. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Pelzel HR, Schlamp CL, Nickells RW. Histone H4 deacetylation plays a critical role in early gene silencing during neuronal apoptosis. BMC Neuroscience. 2010;11, article 62 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Pelzel HR, Schlamp CL, Waclawski M, Shaw MK, Nickells RW. Silencing of Fem1cR3 gene expression in the DBA/2J mouse precedes retinal ganglion cell death and is associated with histone deacetylase activity. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012;53(3):1428–1435. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Zhong Q, Kowluru RA. Role of histone acetylation in the development of diabetic retinopathy and the metabolic memory phenomenon. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2010;110(6):1306–1313. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Garcia-Manero G, Fenaux P. Hypomethylating agents and other novel strategies in myelodysplastic syndromes. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(5):516–523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Jain S, Zain J, O’Connor O. Novel therapeutic agents for cutaneous T-Cell lymphoma. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2012;5, article 24 doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Sarkar S, Abujamra AL, Loew JE, Forman LW, Perrine SP, Faller DV. Histone deacetylase inhibitors reverse CpG methylation by regulating DNMT1 through ERK signaling. Anticancer Research. 2011;31(9):2723–2732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Xiong Y, Dowdy SC, Podratz KC, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease DNA methyltransferase-3B messenger RNA stability and down-regulate De novo DNA methyltransferase activity in human endometrial cells. Cancer Research. 2005;65(7):2684–2689. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Arzenani MK, Zade AE, Ming Y, et al. Genomic DNA hypomethylation by histone deacetylase inhibition implicates DNMT1 nuclear dynamics. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2011;31(19):4119–4128. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01304-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]