Abstract

Librarians continually integrate new technologies into library services for health sciences students. Recently published data are lacking about student ownership of technological devices, awareness of new technologies, and interest in using devices and technologies to interact with the library. A survey was implemented at seven health sciences libraries to help answer these questions. Results show that librarian assumptions about awareness of technologies are not supported, and student interest in using new technologies to interact with the library varies widely. Collecting this evidence provides useful information for successfully integrating technologies into library services.

INTRODUCTION

Health sciences students enter programs with a variety of devices (laptops, tablets, and smartphones) as well as varying levels of knowledge of software. Academic medical libraries that serve students invest in new devices, software, and technology, and devote staff time to projects involving these tools 1–5. The University of Southern California (USC) Health Sciences Libraries (HSL) have conducted similar pilot projects using mobile devices, adding quick response (QR) codes to link print and electronic books; providing instruction on software, e-readers, and mobile devices; and establishing presences on social media networks. Not all of these projects succeeded as planned, so librarians turned to the literature for guidance.

Library literature provides data about patron ownership of devices and operating systems 6–10 and patron interest in new software and technologies 11–16. The rates of adopting technologies and assessing the value of these new technologies in a library setting are also discussed 1–5, 17–24. No articles simultaneously address what seem to be the three critical facets for designing student-focused library technology projects: device ownership, awareness of software and technology, and willingness to use devices and software to interact with the library. Moreover, given the rapid pace of technological change, the information in published studies is almost always too dated to be completely useful. Health sciences librarians require current data to use in making evidence-based decisions when considering projects using new technologies.

METHODS

In early 2012, the Emerging Technologies Committee of USC HSL developed a sixteen-question instrument (Appendix, online only). The survey was submitted to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at USC, and the board concluded that the research was exempt from IRB review. The survey was generated using Wufoo <http://www.wufoo.com> and was distributed only in electronic form to the USC Health Sciences incoming students in fall 2012 via email discussion lists or during class orientations and library registration. Students were advised that the survey was entirely anonymous and optional, and intended to provide USC HSL with information to tailor library services to current student interests.

The committee developed a letter to introduce the idea of the survey to other health sciences libraries to achieve a more representative sample and to lay the groundwork for a common annual survey. The letter requested that no questions except those regarding status and affiliation with the school be altered, that the health sciences schools should utilize their own survey tools, and if they did not have one available, USC would host a survey for them and that the survey should be distributed close to the arrival of incoming students. The letter was sent via email to the 116 member libraries in the Association of Academic Health Sciences Libraries. Six health sciences libraries chose to participate.* Each library designed its own method of distributing the survey to health sciences students.

RESULTS

Data were collected and combined from 1,513 respondents (out of 6,270 potential respondents) representing 7 institutions. Some institutions altered questions or responses rendering them unfit for inclusion in analysis. Response rates are included for each item. Other questions permitted selection of multiple answers, and total number of responses received is included. Some institutions expanded the survey beyond incoming health sciences students; all responses are analyzed here.

Respondents were professional students (69%), graduate students (15%), post-baccalaureate students (3%), faculty (4%), staff (1%), residents (5%), and other (1%, n = 1,326). Respondents were asked to report their affiliations: medicine (25%), pharmacy (23%), dentistry (15%), nursing (15%), physical therapy (5%), public health (5%), science and health/biomedical (5%), veterinary medicine (3%), osteopathic medicine (2%), occupational therapy (1%), and other (1%, n = 1,510). For ages, 55% were in the 20–25 range; 25% were 26–30 years, 7% were 31–35 years, 6% were 36–45 years, 5% were 46–55 years, 2% were 56–65, and 1% were 66 and up (n = 1,350). There were more female respondents (59%) than male (41%, n = 1,513).

Ownership of devices

Responses indicated that incoming students used a wide variety of devices. Fifty-six percent of respondents used PC laptops, 46% Mac laptops, 74% smartphones, 34% tablet devices, and 15% e-book readers; none did not use any of these devices (n = 3,475). For smartphone operating systems, 48% had iOS, 25% had Google/Android, 6% had Blackberry OS, 2% had Windows Mobile, 1% had other, 4% were unsure, none had Symbian, 7% did not have a smartphone but planned to get one, and 6% were not interested in any smartphone (n = 1,521). When asked about tablet operating systems, 34% had iOS, 10% had Google/Android, 1% had Blackberry, 1% had Windows Mobile, 2% were not sure, 17% did not have a tablet but planned to get one, and 32% were not interested in tablets (n = 1,467).

Respondents were asked which brand of e-book reader they used. Twenty percent owned Kindles; 18% used their tablets for reading e-books; 3% owned Nooks; none owned Kobos, Sonys, Bookeens, or COOL-ERs; 12% did not have a reader but planned to get one, and 46% said that they were not interested in any e-book reader (n = 1,300).

Awareness of new technologies

Respondents were asked to select a phrase that best describes them with regard to use of technologies. Seven percent used new technologies before anyone else, 19% used technologies a little before others, 47% used technologies at the same time as everyone else, 25% took a while to use new technologies, and 2% avoided new technologies (n = 1,148).

When asked about preferences for e-books, 33% of respondents said that they did not use e-books at all and preferred print books. Twenty percent said that they intended to use e-books more in the future; 19% said that they preferred e-books for leisure reading, but not for academic purposes; 9% said they preferred print books for leisure reading, but not for academic purposes; and 5% said they intended to use more print books in the future. Eleven percent of respondents did not have a preference with regard to e-books (1,738 total responses). When asked to select all the instant messenger (IM) tools that they currently used, 62% used Facebook, 31% used Google Talk, 7% used Yahoo Messenger, 7% used other, none used Meebo or Pidgin, and 20% did not use any IM tools at all (2,148 responses).

To gauge awareness, respondents were asked to report if they used or had heard of Facebook, Twitter, Google+, MySpace, LinkedIn, Second Life, Delicious/Diigo, Zotero, Skype, FourSquare, Pinterest, Mendeley, Google Reader, and QR codes. The only one of these systems used regularly by more than half of respondents was Facebook: 59% report that they used it all the time, 24% used it sometimes, 5% were using it more, 6% used to use it, another 6% never used it, and no one had never heard of it (n = 1,301). There was some use of Twitter and Google+: 5% of respondents used Twitter all the time, 10% used it sometimes, 3% were using it more, 9% used to use it, 2% never heard of it, and 71% never used it (n = 1,278). For Google+, 11% used it all the time, 13% used it sometimes, 7% were using it more, 13% used to use it, 53% never used it, and 2% never heard of it (n = 1,255). Ten percent of respondents used Skype all the time, while 36% used it sometimes, 11% were using it more, 20% used to use it, 22% never used it, and 1% never heard of it (n = 1,277). Other options were rarely used: 67% never used MySpace, and 3% never heard of it (n = 1,267); 62% never used LinkedIn, and 8% never heard of it (n = 1,264); 47% never used Second Life, and 51% never heard of it (n = 1,260); and 58% never used Pinterest, and 15% never heard of it (n = 1,261). In several cases, more than half of the respondents had never heard of the option: 60% of respondents said they never heard of Delicious/Diigo, and 38% never used it (n = 1,258). Thirty-five percent of respondents said they never used Zotero, and 60% never heard of it (n = 1,346); and 39% never used Mendeley, and 58% never heard of it (n = 1,261). FourSquare had 1% of respondents using it all the time, 2% using it sometimes, 1% using it more, 49% using it in the past, 24% never using it, and 24% never having heard of it (n = 1,261). For Google Reader, 4% used it all the time, 10% used it sometimes, 5% were using it more, 5% used to use it, 52% never used, and 24% never heard of it (n = 1,249). One percent used QR codes all the time, 6% used them sometimes, 3% were using them more, 4% used to use them, 39% never used them, and 47% never heard of QR codes (n = 1258).

Willingness to use new technologies to interact with the library

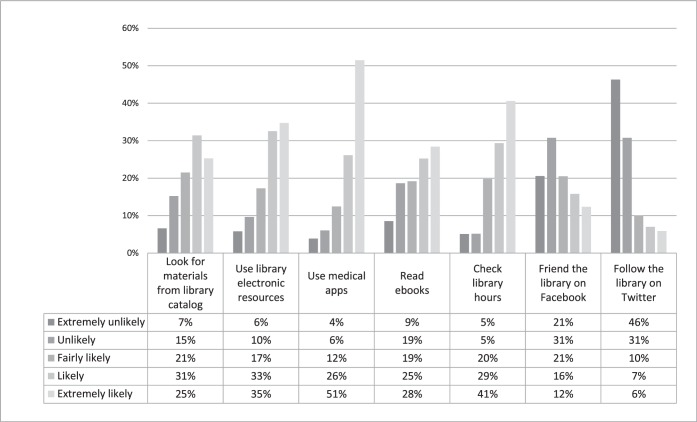

Respondents were asked how likely they would be to use their smartphone or tablet to interact with library services and staff (Figure 1). Respondents were most willing to use their smartphones or tablets to use medical apps provided through the library, check library hours, and use the library's electronic resources. They also were likely or fairly likely to use their smartphones or tablets to look for materials in the catalog or read e-books. When social media were examined, the majority of respondents were not interested in following the library on Twitter (31% unlikely, 46% extremely unlikely) or friending the library on Facebook (31% unlikely, 21% extremely unlikely).

Figure 1.

Likelihood of accessing library services through mobile technology

Respondents were asked about their likelihood of using text/short message service (SMS) to receive library services. Signing up to receive overdue or renewal notices generated the most positive responses (30% extremely likely, 29% likely, 19% fairly likely, 9% unlikely, and 3% do not text [n = 1,452]). There was moderate interest in texting a question to a librarian (13% would be extremely likely, 19% likely, 23% fairly likely, 18% unlikely, 18% extremely unlikely, and 3% do not text [n = 1,465]) or in texting to renew library material (32% would be extremely likely, 29% likely, 17% fairly likely, 9% unlikely, 10% extremely unlikely, and 3% do not text [n = 1,452]). Little interest was evidenced in texting a call number from the catalog (16% would be extremely likely, 22% likely or fairly likely, 28% unlikely, and 22% extremely unlikely [n = 1,444]).

The survey also asked respondents to indicate which monthly lunchtime workshops on technology topics they would be likely to attend. Google tools (39%) and presentation tools (37%) generated the most interest, followed by mobile device apps (29%), photo editing tools (28%), video editing tools (19%), social networking tools (15%), blogs (8%), really simple syndication (RSS) readers (7%), and Web 2.0 applications (6%) (n = 3,010).

DISCUSSION

Despite the volume of library literature discussing the adoption and benefits of new technologies 1–5, 17–24, survey results of first-year students found that they do own devices but are unaware of many of the newer technologies. Regardless of their awareness of technologies, they are only willing to use certain types to interact with the library. There is clearly little interest in using social media with the library, but there is significant interest in using devices to communicate with the library to obtain information about hours, availability of materials, due dates and interest in accessing materials licensed by the library, such as e-books and apps. Health sciences students also perceive themselves to be equal to or slightly more advanced than others in terms of adopting new technologies.

While a general understanding of student technology awareness is helpful, it is the specifics of this kind of survey that make it so valuable. As intended, the survey data have been extremely helpful in planning new technology projects. For example, QR codes are perceived to be low-cost technologies to implement, but an 18-month project to create, print, and affix codes, and track usage for 200 print books and 10 subject guides took nearly 30 hours of staff time and the majority of the QR codes received no hits. Prior to the survey, librarians were unsure if low usage was due to placement and marketing or to lack of awareness of QR codes. Survey data made it clear that it was the latter, and so projects using QR codes—linking print books with electronic equivalents and affixing them in the stacks to guide browsers to subject-specific electronic books—have been eliminated.

The authors have also been able to use awareness data to select topics for drop-in educational workshops at the USC HSL. Sessions focused on technologies that patrons reported that they had never heard of, including e-books and LinkedIn, have been well attended. Additionally, survey results permitted an in-depth assessment of social media strategies. Efforts placed on using Google+, Facebook, and Twitter have been slowed and redirected to other communications mechanisms, given that respondents are unlikely to friend or follow the library on social networks. Staff time is being directed toward implementing the technologies that patrons are interested in, such as finding, downloading, and using medical apps for mobile devices.

The authors plan to administer this survey annually and hope that other institutions will do likewise. In that way, data from this survey can also be used to anticipate and monitor future interests and needs. E-book readers have been forecast as important devices, and USC HSL were considering purchasing several such devices. With a demonstrated lack of interest in such readers in 2012/13, this project can be placed on hold and revived if patron interest is shown to change. An annual survey will permit librarians to monitor technology adoption trends and react to these trends appropriately.

There are several limitations to the survey. The survey only examined first-year students. This population was chosen because the library could make changes that would affect this group; it can take time to launch new projects. Likewise, there are many surveys conducted on campus, and survey fatigue is a problem. From prior experience, the authors realized that asking all students to complete a survey would result in few responses from students who had progressed further in their degree programs. Another concern is that the majority of respondents were from medicine or pharmacy; however, when the authors examined enrollment, pharmacy and medicine students clearly compose at least 50% of the population that each library involved in the survey serves, so the response patterns match the population surveyed. The survey instrument did not include images. Several of the technologies, such as QR codes, may not be recognized by name but may be recognized visually. Images will be included in future surveys.

CONCLUSION

The survey reported here examines three facets of student use of technology to provide a better picture of patrons' technological habits: ownership of devices, awareness of new technologies, and willingness to use these technologies to interact with the library. The survey provides timely information that librarians can use to customize their services. It can easily be updated each year as new technologies emerge and older ones fade away without compromising the longitudinal data. Ample opportunities exist for comparing trends year over year in a single institution, as well as exploring trends via data sharing across institutions. Administering the survey annually can provide a portrait of how professional health sciences students differ from other populations in terms of their technological savvy and attitudes. With some alteration of questions, the survey can be extended to faculty and clinical user populations. Through these methods, librarians can base their services on real and timely evidence that comes straight from their patrons.

The authors of this survey will continue to administer it at USC HSL and are actively seeking additional collaborators. We will contact the email discussion list of the Association of Academic Health Sciences Libraries annually and discuss the survey at regional and national conferences to obtain additional participating institutions. Health sciences librarians are encouraged to contact the authors of this article to join the collaboration. The survey is updated each spring with new technologies, and the new instrument is distributed to institutional contacts during the late summer.

Electronic Content

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janis F. Brown, AHIP, for her guidance with survey implementation and writing, and Emily Brennan, former librarian at the USC HSL, for her work developing and conducting the survey.

Footnotes

This article has been approved for the Medical Library Association's Independent Reading Program <http://www.mlanet.org/education/irp/>.

A supplemental appendix is available with the online version of this journal.

The seven participating institutions were University of Southern California Health Sciences Libraries, Oregon Health & Science University, University of Arizona, University of Florida Heath Science Center Libraries, University of Missouri–Kansas City (UMKC) Health Science Library, University of Utah, and Western University of Health Sciences (Pomona, CA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Vucovich LA, Gordon VS, Mitchell N, Ennis LA. Is the time and effort worth it? one library's evaluation of using social networking tools for outreach. Med Ref Serv Q. 2013 Jan;32(1):12–25. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2013.749107. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2013.749107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Milian R, Norton HF, Tennant MR. The presence of academic health sciences libraries on Facebook: the relationship between content and library popularity. Med Ref Serv Q. 2012 May;31(2):171–87. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2012.670588. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2012.670588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summey K, Richmond C, Bushhousen E. An examination of e-reader devices and their implications within an academic health science library. J Elec Res Med Lib. 2011 Jul;8(3):217–24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2011.601985. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuddy C, Graham J, Morton-Owens EG. Implementing Twitter in a health sciences library. Med Ref Serv Q. 2010 Oct;29(4):320–30. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2010.518915. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2010.518915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrix D, Chiarella D, Hasman L, Murphy S, Zafron ML. Use of Facebook in academic health sciences libraries. J Med Lib Assoc. 2009 Jan;97(1):44–7. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.97.1.008. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.97.1.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Ber JM, Lombardo NT, Honisett A, Jones PS, Weber A. Assessing user preferences for e-readers and tablets. Med Ref Serv Q. 2013 Jan;32(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2013.749101. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2013.749101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan N, Coppola W, Rayne T, Epstein O. Medical student access to multimedia devices: most have it, some don't and what's next. Inform Health Soc Care. 2009 Mar;34(2):100–5. doi: 10.1080/17538150902779550. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1080/17538150902779550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy G, Gray K, Tse J. “Net generation” medical students: technological experiences of pre-clinical and clinical students. Med Teach. 2008 Feb;30(1):10–6. doi: 10.1080/01421590701798737. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1080/01421590701798737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dørup J. Experience and attitudes towards information technology among first-year medical students in Denmark: longitudinal questionnaire survey. J Med Internet Res. 2004 Jan–Mar;6(1):e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.1.e10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.1.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seago BL, Schlesinger JB, Hampton CL. Using a decade of data on medical student computer literacy for strategic planning. J Med Lib Assoc. 2002 Apr;90(2):202–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atlas MC. Are medical school students ready for e-readers. Med Ref Serv Q. 2013 Jan;32(1):42–51. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2013.749115. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2013.749115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess K, Schick L. Assessment of medical students' use of e-books (originally submitted and listed in abstract book with the title “First-year medical student e-book survey”) Poster presented at: One Health: Information in an Interdependent World; 113th Medical Library Association Annual Meeting and Exhibition, 11th International Congress on Medical Librarianship, 7th International Conference of Animal Health Information Specialists, and 6th International Clinical Librarian Conference; Boston, MA; May 3–8, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushhousen E, Norton HF, Butson LC, Auten B, Jesano R, David D, Tennant MR. Smartphone use at a university health science center. Med Ref Serv Q. 2013 Jan;32(1):52–72. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2013.749134. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2013.749134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franko OI, Tirrell TF. Smartphone app use among medical providers in ACGME training programs. J Med Sys. 2012 Oct;36(5):3135–9. doi: 10.1007/s10916-011-9798-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10916-011-9798-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Muhlen M, Ohno-Machado L. Reviewing social media use by clinicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012 Sep–Oct;19(5):777–81. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000990. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris SS, Barden B, Walker HK, Reznek MA. Assessment of student learning behaviors to guide the integration of technology in curriculum reform. Info Serv Use. 2009 Jan;29(1):45–52. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.3233/ISU-2009-0591. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraft M. Using quick response (QR) codes to discover e-books. Poster presented at: One Health: Information in an Interdependent World; 113th Medical Library Association Annual Meeting and Exhibition, 11th International Congress on Medical Librarianship, 7th International Conference of Animal Health Information Specialists, and 6th International Clinical Librarian Conference; Boston, MA; May 3–8, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevetson E, Boucek B. Keeping current with mobile technology trends. J Elec Res Med Lib. 2013 Jan;10(1):45–51. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2012.762220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu SKW, Du HS. Social networking tools for academic libraries. J Lib Info Sci. 2012 Feb;45(1):64–75. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0961000611434361. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorensen K, Glassman NR. Point and shoot: extending your reach with QR codes. J Elec Res Med Lib. 2011 Jul;8(3):286–93. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2011.602312. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pacheco J, Kuhn I, Grant V. Librarians' use of Web 2.0 in UK medical schools: outcomes of a national survey. New Rev Acad Lib. 2010 Mar;16(1):75–86. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614531003597874. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeFebbo DM, Mihlrad L, Strong MA. Microblogging for medical libraries and librarians. J Elec Res Med Lib. 2009 Sep;6(3):211–23. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15424060903167385. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lapidus M, Bond I. Virtual reference: chat with us. Med Ref Serv Q. 2009 May;28(2):133–42. doi: 10.1080/02763860902816735. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763860902816735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kipnis D, Kaplan G. Analysis and lessons learned instituting an instant messaging reference service at an academic health sciences library: the first year. Med Ref Serv Q. 2008 Jan;27(1):33–51. doi: 10.1300/J115v27n01_03. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J115v27n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.