Abstract

Despite the great diversity of teleoperator designs and applications, their underlying control systems have many similarities. These similarities can be exploited to enable inter-operability between heterogeneous systems. We have developed a network data specification, the Interoperable Telerobotics Protocol, that can be used for Internet based control of a wide range of teleoperators.

In this work we test interoperable telerobotics on the global Internet, focusing on the telesurgery application domain. Fourteen globally dispersed telerobotic master and slave systems were connected in thirty trials in one twenty four hour period. Users performed common manipulation tasks to demonstrate effective master-slave operation. With twenty eight (93%) successful, unique connections the results show a high potential for standardizing telerobotic operation. Furthermore, new paradigms for telesurgical operation and training are presented, including a networked surgery trainer and upper-limb exoskeleton control of micro-manipulators.

I. INTRODUCTION

Many telemanipulation systems have a great deal in common. The robots usually include one or more master manipulators, and one or more remote manipulators. The manipulators have up to six degrees of freedom in Cartesian position and orientation while kinematics functions translate between Cartesian information and the robots’ control workspace. Furthermore, the communication architecture for Internet based teleoperation is often an Internet protocol network socket with a well defined data interface to transmit control data in a fixed binary packet.

Despite these commonalities there has been no accepted framework for interconnecting such systems, and network interfaces are currently described arbitrarily by individual research groups. In the same way that Internet standards have connected heterogeneous computing systems, we predict robot communication standards will speed research, development and deployment of interoperable teleoperated robots.

Internet-based robotic teleoperation has been explored in many experiments using co-developed master and slave systems (e.g. [1], [2]) and network characterizations have shown that under normal circumstances Internet can be used for teleoperation with force feedback [3]. Fiorini and Oboe, for example carried out early studies in force-reflecting teleoperation over the Internet [4]. Furthermore, long distance telesurgery has been demonstrated in successful operation using dedicated point-to-point network links [5], [6]. Meanwhile, work by the Tachi Lab at the University of Tokyo sought to create a very general protocol for telerobotics by describing the unique capabilities of each robot [7].

The authors of this paper, representing nine independent telerobotics laboratories, have identified a need for inter-operability between heterogeneous, telerobotic master-slave systems. The current work is a new direction, exploiting similarities among teleoperation systems to develop standards, simplify software architecture and improve interoperability.

This paper describes a simple, yet effective solution to the problem using a shared data interface, the Interoperable Teleoperation Protocol (ITP). The ITP is very simple for a communication protocol. The simplicity is by design, and we demonstrate that this simplicity allows the easy interconnection of quite different systems. The ITP is essentially a data interface, and is intended as a starting point for development of a robust standard for Internet robotic teleoperation.

Inherent in the interoperability problem is the requirement to support a wide variety of telerobots that differ in kinematics and dynamics, scale, and application. To demonstrate the usefulness of a developed data standard it is necessary to show that it can control a heterogeneous group of robots. Our experiment, titled “Plugfest 2009”, tested the ITP on fourteen unique master and slave robots, most of them designed for telesurgery, at nine locations around the world. The hypothesis examined was that such kinematically diverse systems could be made to work together by using a common data interface and Cartesian-space teleoperation commands.

“Plugfest” is an industry term for an event where vendors come together and test their products for compliance with a new standard. We adopted this word and methodology for testing the ITP, creating a one-day event wherein many systems were interconnected and tested for functionality. Performing the testing in a single 24 hour period accomplished two goals: first, it demonstrated that extensive tweaking is not required to switch connections between systems; and second, it showed that engineers could integrate the protocol within a consistently short time from project start in early summer to the end of July. Our primary experimental result is the number of unique, successful master-slave connections, which demonstrates the value of the ITP for interoperable teleoperation. The experiment focuses on the telesurgery application domain by incorporating mostly surgical telerobots, but includes general purpose teleoperators as well.

In this experiment existing, published teleoperation robots were retrofitted to use the ITP. It is important to realize that these are not fourteen systems designed together for compatibility, but rather that a novel communication scheme can tie these disparate systems together with a small integration effort at each site.

It should be further noted that several communications architectures and open-source software packages are available for general robotic operation over the Internet (e.g. [8]-[11]). However, these are often designed for mobile robots, and are unsuitable for the high packet rates and extreme delay sensitivity particular to telemanipulators and telesurgery systems. One interesting software application is the Surgical Assistant Workstation [12]. Our work differs in that ITP is not a software application or library, but rather a data interface that is capable of controlling a wide range of teleoperators and can be implemented on any computing platform. Also, OpenIGTLink is a proposed protocol for medical imaging and medical device description and control [13]. This is interesting research into the medical systems integration problem, but has not yet explored the interoperability question for medical or general teleoperation systems.

II. Interoperable Telerobotics

To demonstrate interoperable telerobotics over the global Internet, fourteen unique telerobotic master and slave systems were connected by nine groups in five countries. In the context of surgical telerobotics, the master manipulator is operated by the surgeon in order to control the motions of the slave, or patient-side robot. All the connected systems used the same network facing data interface, which we call the Interoperable Teleoperation Protocol or ITP.

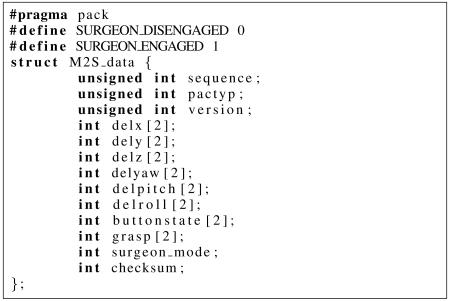

A. Interoperable Teleoperation Protocol

ITP is a stateless data description representing commands between the master and slave robot. The ideal protocol is robust enough to work with any new teleoperators independently of their design, and flexible to accommodate any new data transforms or teleoperation architectures. Therefore, a mechanism is built into ITP for designating new, numbered data specifications, extending the protocol to new innovations. To make cooperation as simple as possible, the first data interface for the ITP is a low-overhead binary UDP packet structure, and it’s C implementation is shown in Listing 1. This is the data packet used in experiments described in this paper. The “pactyp” (packet type) and “version” fields indicate the packet type in use. For these experiments packet type one was used, and the ITP version was 0.43 (or 43 as an integer). The small size, 84 bytes, makes this data type suitable for high packet rates.

Listing 1.

C implementation of the binary packet structure sent from master to slave robot.

The ITP requires a common reference frame. From the users’ perspective the right-handed frame has: the positive Y-axis pointing right, the positive X-axis pointing away, and the positive Z-axis pointing down. Each master and slave implement transformations to convert between their own coordinate systems and the common reference frame.

There are many ways to describe movement commands from master to slave. For networked teleoperation it is important that the system be robust to arbitrary network delays and packet loss. In particular, the commanded movement should be free from major discontinuities, and should act “safely” when recovering from a period of delay. In the current experiment, motion commands for two arms are encoded as position increments in three Cartesian dimensions (delx, dely, delz) and orientation increments in roll, pitch and yaw (delroll, delpitch, delyaw). Position is in units of integer microns and orientations are in integer micro-radian units. The choice of integers sidesteps the complexity of floating point specifications. Increments of position and orientation were calculated as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

In this representation there is no explicit notion of a time-step, making the scheme more robust to varying network delay and packet rate compared to velocity coding schemes. In response to packet loss, the result is position drift, compared with absolute motion commands which would entail step discontinuities in commanded position. With small packet loss the drift is minor and easily accommodated by the user through indexing.

Indexing is a common feature among teleoperation systems and allows the user to reposition the master without moving the slave. The incremental motion scheme simplifies indexing, since absolute position agreement is not required between master and slave. Two states, “engaged” and “disengaged”, are defined to coordinate indexing and are indicated in the “surgeon_mode” field of Listing 1. While in the disengaged state, the slave robot should ignore any motion commands until the engaged state is requested.

Endianness and data types were chosen to conform to 32-bit ×86 architecture.

Scaling of the user’s motion is another common feature among teleoperators. The scale factor is not explicitly encoded by the ITP. Instead motion scaling is controlled by the master side and is implicit in the scaled motion commands.

The lightweight UDP datagram protocol is used, since it does not require the additional overhead of the more common TCP protocol. UDP does not guarantee data integrity, but does provide the lowest possible latency. A sequence number is important for tracking out-of-sequence or lost packets, and corrupt packets are detected by the checksum and discarded. Most importantly, lost incremental motion packets will not lead to unpredictable or unsafe motion of the slave manipulator.

The ITP does not specify a packet rate. These experiments used packet rates from 10Hz up to 1kHz. 1kHz packet rates are exceptionally high compared to average Internet usage. However, there were no problems reported in our experiments due to the high rate, a result that agrees with [3].

B. Connected Slave Systems

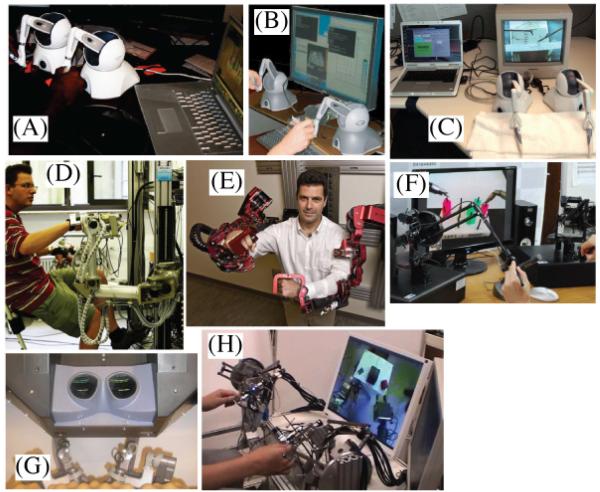

The six slave systems used in the experiment are described here and shown in Figure 1. All systems have two manipulator arms and were operated via UDP/IP using ITP. Each system is previously published and complete technical details of the robots and simulator are found in the references.

Fig. 1.

(A) TUM general purpose Telerobot. (B) Patient-side robot of the JHU custom version of the da Vinci. (C) TokyoTech IBIS IV surgical robot. (D) RPI VBLaST™. (E) SRI M7 surgical robot. (F) UW Raven surgical robot.

The Raven surgical system developed at the University of Washington, BioRobotics Lab, Seattle (UW, Seattle, WA, USA) is a six degree of freedom (DoF) capable, cable-driven research robot for remotely operated minimally invasive surgery (MIS). It has a unique spherical mechanism for MIS operation around the trocar point [14].

Located at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, Suzukakedai Campus (TokyoTech, Yokohama, Japan) the IBIS IV system is a pneumatically actuated MIS research robot with 6 DoF plus a gripper [15]. The IBIS IV detects environmental contact force without the use of a force sensor by inference from the pneumatic pressure.

Johns Hopkins University (JHU, Baltimore, MD, USA) connected a commercial MIS robot, the JHU Custom daVinci. The robot hardware is from Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA, with custom control software and electronics by Johns Hopkins. The daVinci represents the state of the art in commercial surgical robotics [16].

The M7 surgical research robot was connected at SRI International (SRI, Menlo Park, CA, USA). The M7 is a 6 DoF robot designed for open telesurgery with battlefield and trauma applications [17].

The VBLaST™ laparoscopic training simulator was connected at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI, Troy, NY,USA). It is a virtual reality based bi-manual trainer with haptics that is designed to replicate the FLS tasks. Two virtual MIS tools follow the motion of a physical tool connected to the interface, or may be teleoperated via the built-in network support.

Technische Universität München (TUM, Munich, Germany) connected a general purpose, redundant 7 DoF telemanipulator with a relatively large grasper. The two anthropomorphic arms were designed for general, large-scale manipulation tasks. [18]

This diverse group of slave systems demonstrates the wide variety of robotic capabilities that would be available to surgeons in a standardized, networked surgery world.

C. Connected Master Systems

Eight master systems, shown in figure 2, were used in the experiments. The master systems transmitted ITP data at up to 1kHz via UDP/IP. Although many of the systems are haptic devices capable of force-feedback, that function was not used in these experiments. Again, each system is previously published and complete technical details are available in the references.

Fig. 2.

(A, B, C) Phantom Omni control station with free software at RPI, ICL and UW respectively. (D) TUM ViSHaRD7. (E) UCSC Exoskeleton. (F) Phantom Premium with custom software at KUT. (G) Master console of the JHU custom version of the daVinci. (H) TokyoTech delta master.

Three of the master systems at UW, RPI and Imperial College London (ICL, London, UK) comprised two 6DoF Phantom Omni (SensAble Inc, Woburn, MA, USA) haptic devices and surgical console software from UW [19].

Korea University of Technology and Education (KUT, Cheonan, South Korea) used the Phantom Premium (SensAble Inc.) with their own ITP compatible software.

A commercial daVinci surgeon console (Intuitive Surgical, Inc.) with custom controller and software was used at JHU [16].

At the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) an upper-limb powered exoskeleton was used, allowing whole-arm motions to scale down to surgery scale tasks [20]. One-arm operation was performed with this system, so bi-manual tasks were simplified to one arm.

At TUM, ViSHaRD7, a custom designed, general-purpose master with 7 DoF was incorporated [21]. The arms are mounted on a mobile platform to form a mobile haptic interface, but in this experiment the mobile base was not activated.

Finally TokyoTech developed a master system with haptic feedback based on a delta motion platform specifically for control of MIS assistant robots [22].

III. Experimental Methods

A. Telerobotic FLS

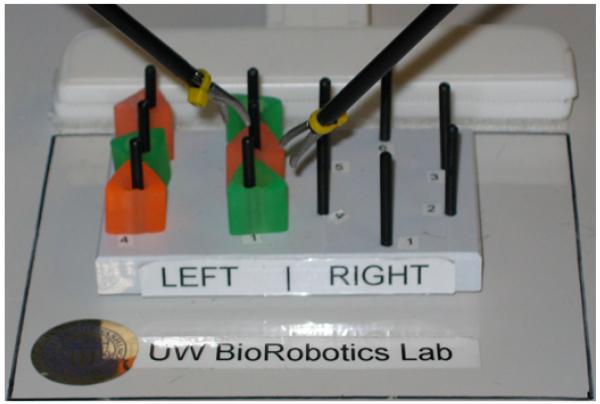

Wherever possible, participants in this experiment performed the Telerobotic Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery (TFLS) block transfer task, modified for time constraints. Exceptions were made for some robots as described below. TFLS was adapted by Lum [23] from a proprietary scoring method invented by the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) to evaluate surgeons’ laparoscopic proficiency [24]. The test can be seen in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

The Telerobotic FLS block transfer task.

The TFLS Block Transfer task is essentially a pick-and-place task. Six plastic blocks approximately one cm3 are first arranged on the left half of an array of pegs. Subjects grasp each numbered block in order with the left hand, lift it from the peg, transfer the block to the right hand tool, and place the block on a numbered peg on the right side of the board. In this experiment, participants transferred as many blocks as possible in ten minutes.

Due to particular robot configurations, task modifications were necessary in a few cases. The TUM Telerobot slave was designed for manipulating larger objects, so a substitute, bi-manual, pick-and-place task was performed. Users transferred a 4×4×5 cm cube 20 cm from the right to left side of an 8×8×8 cm obstacle, switching hands in the process.

The UCSC Exoskeleton was operated with one-arm only, so the FLS block transfer was simplified, and performed without the hand-to-hand transfer.

B. Plugfest Experiment

Nine groups from North America, Asia and Europe participated in this experiment testing interoperability among their systems. In one 24-hour period on July 30, 2009 participating groups connected over the Internet to control the other robots recording success or failure of the connection and performance on a simple task. Each master-slave connection was restricted to a one-hour slot to connect and complete the experimental task.

With eight masters and six slaves, forty-eight connections were possible. However, labs did not connect their own master-slave combinations, and, to keep the operating schedule within reasonable hours, only global regions separated by less than nine hours were connected. With these constraints thirty two connections were possible. Thirty were attempted, and two were not attempted due to time limitations.

Feedback to the user was visual only and did not include haptics. The focus of this research is on teleoperation rather than video technologies, so Skype™video was selected due to its ubiquity, easy of use and cross-platform compatibility. The type and location of the camera, PC specification, and video display configuration were not controlled in the experiment.

In each connection the block transfer task was performed one to three times and the number of transferred blocks was recorded, or transfer time when appropriate. Network time delay was measured and recorded in each connection using round trip “ping” times wherever possible.

IV. Results

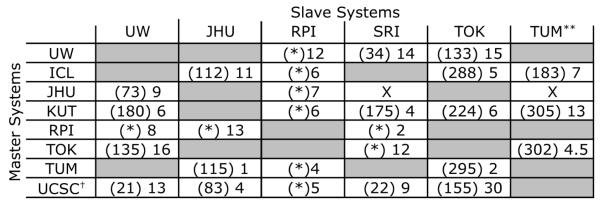

Thirty trials were conducted in which the various master and slave systems connected across the Internet. Of those, 28 resulted in successful task completion, 20 bi manual TFLS, five one-handed TFLS block transfer, and three bi-manual gross manipulation tasks.

Figure 4 shows the number of blocks transferred and ping times for each master-slave connection. The average number of blocks transferred in the 20 successful bi-manual TFLS trials was 7.4. The average number of blocks transferred one-handed was 11.6. The average time for block transfer in the gross manipulation trials was 8.2 minutes. The most blocks transferred in ten minutes with bi-manual operation was 16. 30 blocks were transferred using the upper-limb exoskeleton to control the MIS robot at Ttech, IBIS, in the one-handed mode of operation. The highest average blocks transferred per connection for any slave robot was on the UW slave system with an average of 9.5 blocks per 10 minute connection.

Fig. 4.

Number of blocks transferred in each master-slave trial, and ping response times in parenthesis. *Ping times not taken. **Block transfer task completion time. †One-handed operation only.

There were two unsuccessful trials. In one case a slow packet rate of 10Hz was incompatible with a slave-side controller that assumed 1kHz updates. The resulting behavior triggered a slave-side safety system which harmlessly shut down the robot. For unknown reasons, the behavior was asymmetrical; the right arm moved fine, while the left one caused the fault. In the second unsuccessful case, the orientation mapping between master and slave was too confusing, and the user did not complete the task.

V. Discussion

Results show that ITP, providing Cartesian-space motion control commands, is effective for operating a wide range of teleoperation systems. The outstanding result of the experiment is that twenty-eight out of thirty unique attempted connections were successful (93% success rate). In this case, successful operation is defined as an operation wherein a task could be completed, and results given in the table of Figure 4 demonstrates that all but two configurations were capable of performing the task.

Besides differences in users’ experience level and familiarity with the robots, a major source of variation in task performance was due to the video configuration. Skype™ was easy to use across platforms and was effective in all thirty connections. However, as mentioned earlier, video parameters including camera type and placement, video codecs, and display configuration were not controlled. Participants also complained about the lack of depth perception demonstrating the need for high-definition and stereo vision. This is an additional avenue of exploration that could benefit telerobotic interoperability, i.e. agreement on video standards, especially high-definition and stereo vision codecs.

Therefore, caution must be taken in considering the numerical results of Figure 4. The number of blocks transferred in a given connection was highly influenced by many factors that were not controlled in the experiment, and therefore does not serve as an objective comparison of master-slave performance. What the results do show is whether or not the ITP was an effective data interface and control link between the master and slave robots.

What’s more, Plugfest 2009 demanded that a globally dispersed robot and human operator population to interoperate in a time-critical fashion. In many cases the slave system was “hot-swapped”- operated by several different masters in rapid succession without restarting. Smooth interoperability like this will improve collaborative telerobotic action as, for example, a patient is handed off to a remote surgical specialist for part of a procedure; or multiple users trade control of a telerobot during a long operation.

Furthermore, several interesting telesurgical technologies were explored in this experiment. A virtual reality surgical simulator was controlled in the exact same way as the physical slave systems, demonstrating how surgeons around the world may train on an advanced simulation platform without a specialized simulator on-site. Also, several types of surgical master and slave systems were connected, exploring different modes for human action and control. Use of the UCSC Exoskeleton showed how a surgeon’s full range of upper limb motion could be scaled down to control minimally invasive surgical manipulators. Moreover, inexpensive, off-the shelf human interface devices were used with free, open-source software and controlled state-of-the art surgical robots for fine, surgery-like tasks. With a standard protocol, new teleoperation hardware will become easier to integrate into existing applications, and in the future surgeons, will be able to select among competing “surgical cockpit” designs.

Twenty-eight out of thirty attempted connections resulted in some degree of task completion. However, even among these there were some difficulties. In many instances, orientation mapping from master to slave was unnatural or incorrect, in that rotation of the master did not produce the desired rotation of the slave. In at least four cases this was severe enough that orientation degrees of freedom were disabled and robots were operated in three DoF Cartesian space. At the same time, the method of using orientation increments to represent the roll, pitch and yaw leaves open the problem of RPY singularities and the jump discontinuities associated therewith. This will have to be fully addressed in future work, possibly by changing the orientation representation to quaternion increments.

Future work should also address security and session negotiation. Data security is a consideration that could be addressed via encryption. Session management is another consideration. As an example, in one connection, due to a miscommunication, UCSC and UW sent packets simultaneously to RPI VBLaST resulting in erratic action of the simulated robot. To resolve this, a system for user authentication and exclusion is necessary, possibly by using a stateful session layer protocol that works with the stateless data exchange protocol.

VI. Conclusions

In this work we have shown the feasibility of using a simple data interface, the Interoperable Telerobotic Protocol, to control heterogeneous teleoperation systems over the global Internet. In a relatively short span of time in early summer 2009, robots with differing kinematics, hardware and software for medical and non-medical applications were retrofitted to use the ITP, thus becoming seamlessly inter-operable. Results of our experiment, titled Plugfest 2009, demonstrated that the uncomplicated ITP protocol is one solution to the interoperability problem. A more complex protocol would likely be more difficult and take more resources to adapt to the variety of pre-existing computing hardware, programming languages and robot controllers involved in this project.

Although this experiment focused on application to telesurgery, the developed architecture is generalizable to a wide range of telerobotics uses. Future work should focus on incorporating force feedback and more sophisticated bilateral control techniques into the ITP, while keeping the data specification simple. The results of this new research direction will be a standardized, robust telerobotics Internet protocol.

The authors predict that increased collaboration will result from this research and expect interesting synergistic results.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the following people for their contributions to this work: George Mylonas and David Noonan at Imperial College London, Diana Friedman at the University of Washington, Seattle, and Tomonori Yamamoto of Johns Hopkins University

References

- [1].Goldberg K, Gentner S, Sutter C, Wiegley J. The Mercury Project: A feasibility study for Internet robots. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine. 2000;7(1):35–40. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hannaford B, Hewitt J, Maneewarn T, Venema S, Appleby M, Ehresman R. Telerobotic remote handling of protein crystals; IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation; Albuquerque, NM. Apr. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sankaranarayanan G, Potter L, Hannaford B. Measurement and simulation of time varying packet delay with applications to networked haptic virtual environments; Proceedings of Robocom 2007; Athens, Greece. Oct. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oboe R, Fiorini P. A design and control environment for internet-based telerobotics. The International Journal of Robotics Research. 1998;17(4):433. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Marescaux J, Leroy J, Gagner M, Rubino F, Mutter D, Vix M, Butner SE, Smith MK. Transatlantic robot-assisted telesurgery. Nature. 2001 Sep;413(27):379–380. doi: 10.1038/35096636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Anvari M. Remote telepresence surgery: the Canadian experience. Surgical Endoscopy. 2007;21(4):537–541. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9040-8. 04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tachi S. Real-time remote robotics-toward networked telexistence. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications. 1998;18(6):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gerkey B, Vaughan R, Howard A. The player/stage project: Tools for multi-robot and distributed sensor systems; Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Advanced Robotics; 2003.pp. 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Utz H, Sablatng S, Enderle S, Kraetzschmar G. Miromiddle-ware for mobile robot applications. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation. 2002 Aug;18(4) [Google Scholar]

- [10].Joint Architecture for Unmanned Systems (JAUS) Reference Architecture. (Version 3.0) http://www.jauswg.org/

- [11].Microsoft Robotics Studio. http://msdn.microsoft.com/robotics

- [12].Jung M, Xia T, Deguet A, Kumar R, Taylor R, Kazanzides P. A surgical assistant workstation (saw) application for teleoperated surgical robot system. The MIDAS Journal - Systems and Architectures for Computer Assisted Interventions. 2009 http://hdl.handle.net/10380/3079. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tokuda J, Fischer G, Papademetris X, Yaniv Z, Ibanez L, Cheng P, Liu H, Blevins J, Arata J, Golby A, et al. OpenIGTLink: an open network protocol for image-guided therapy environment. Int J Med Robot Comput Assist Surg. 2009;5:423–434. doi: 10.1002/rcs.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lum M, Friedman D, Sankaranarayanan G, King H, Fodero K, Leuschke R, Hannaford B, Rosen J, Sinanan M. The raven - design and validation of a telesurgery system. The International Journal of Robotics Research. 2009;28(9):1183–1197. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tadano K, Kawashima K. Development of a pneumatically driven forceps manipulator ibis iv; ICROS-SICE International Joint Conference; 2009.pp. 3815–3818. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mahvash M, Gwilliam J, Agarwal R, Vagvolgyi B, Su L, Yuh D, Okamura A. Force-feedback surgical teleoperator: Controller design and palpation experiments; 16th Symposium on Haptic Interfaces for Virtual Environments and Teleoperator Systems. [Google Scholar]

- [17].King H, Low T, Hufford K, Broderick T. Acceleration compensation for vehicle based telesurgery on earth or in space; IEEE/RSJ Int’l Conf. on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); Sept. 2008.pp. 1459–1464. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stanczyk B, Buss M. Development of a telerobotic system for exploration of hazardous environments. Sept. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sankaranarayanan G, King HH, Ko S-Y, Lum M, Friedman D, Rosen J, Hannaford B. Portable surgery master station for mobile robotic telesurgery; Proc. of ROBOCOMM; Athens, Greece. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Perry J, Rosen J. Design of a 7 degree-of-freedom upper-limb powered exoskeleton; Proceedings of the 2006 BioRob Conference; Pisa, Italy. Feb. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Peer A, Buss M. A new admittance-type haptic interface for bi-manual manipulations. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics. 2008;(4):416–428. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tadano K, Kawashima K. Development of a master slave system with force sensing using pneumatic servo system for laparoscopic surgery; IEEE Intl. Conf. on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2007.pp. 947–952. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lum M, Friedman D, Sankaranarayanan G, King H, Wright A, Sinanan M, Lendvay T, Rosen J, Hannaford B. Objective assessment of telesurgical robot systems: Telerobotic FLS; Proc., Medicine Meets Virtual Reality (MMVR); Long Beach, CA. 2008; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Peters J, Fried G, Swanstrom L, Soper N, Sillin L, Schirmer B, Hoffman K. Development and validation of a comprehensive program of education and assessment of the basic fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery. Surgery. 2004;135(1):21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]