Abstract

Site-specific labeling of enzymatically synthesized DNA or RNA has many potential uses in basic and applied research, ranging from facilitating biophysical studies to the in vitro evolution of functional nucleic acids, and the construction of various nanomaterials and biosensors. As part of our efforts to expand the genetic alphabet, we have developed a class of unnatural base pairs, exemplified by d5SICS-dMMO2 and d5SICS-dNaM, which are efficiently replicated and transcribed, and which may be ideal for the site-specific labeling of DNA and RNA. Here, we report the synthesis and analysis of the ribo- and deoxyribo-variants, (d)5SICS and (d)MMO2, modified with free or protected propargylamine linkers that allow for the site-specific modification of DNA or RNA during or after enzymatic synthesis. We also synthesized and evaluated the α-phosphorothioate variant of d5SICSTP, which provides a route to backbone thiolation and an additional strategy for the post-amplification site-specific labeling of DNA. The deoxynucleotides were characterized via steady-state kinetics and PCR, while the ribonucleosides were characterized by the transcription of both a short, model RNA as well as full length tRNA. The data reveal that while there are interesting nucleotide and polymerase-specific sensitivities to linker attachment, both (d)MMO2 and (d)5SICS may be used to produce DNA or RNA site-specifically modified with multiple, different functional groups with sufficient efficiency and fidelity for practical applications.

1. Introduction

The sequence-specific amplification of DNA and RNA has revolutionized biotechnological and biomedical research, making techniques such as cloning and sequencing routine, and also enabling a variety of emerging techniques with important applications in diverse fields ranging from synthetic biology,1 to nanomaterials2,3 and medical diagnostics.4,5 In addition, the use of polymerases to amplify DNA molecules has made it possible to evolve functional DNAs or RNAs with desired ligand recognition or catalytic properties.6,7 However, the potential physical and functional properties of nucleic acids are restricted by the limited diversity of their constituent nucleotides. While the potential diversity of DNA or RNA may be expanded via chemically synthesizing the oligonuclotides,8-10 this approach is incompatible with enzymatic amplification. Thus, efforts have been directed towards the modification of one or more of the natural triphosphates with linkers that enable the attachment of different functional groups without ablating polymerase recognition.11-21 The best sites of linker attachment have proven to be the nucleobases: specifically, the C5 position of the pyrimidines and the C7 position of the 7-deaza purine scaffold. With the pyrimidine scaffold, the detailed structure of the linker is critical,13,15 with rigid alkynes or trans-alkenes being optimal.13,19,22,23 At least with the propargylamide-like linkers and A-family polymerases (such as Taq), this appears to result at least in part from favorable hydrogen-bonding interactions between the polymerase and the amide carbonyl group of the linker.24

While the linker modification of one or more natural dNTPs allows for the polymerase-mediated synthesis of highly functionalized DNA, the efficiency of modified triphosphate incorporation is generally reduced compared to their natural counterparts, resulting in lower yields of amplified product as well as strong sequence-dependences.14,25 For oligonucleotide evolution experiments, this sequence-dependent efficiency is especially problematic because it decouples amplification level from copy number, and thus from fitness, during the amplification step required after or during selection. Moreover, high functional group density is unavoidable in any nucleotide-specific labeling strategy (i.e. all or none of a given nucleotide must be modified), but the majority of functional groups are unlikely to contribute to any desired property while still contributing to biases in replication. Finally, it is noteworthy that proteins rarely (if ever) employ such a high density of functional groups, but instead typically have only one or a few that are embedded in a controlled environment where their activity (i.e. pKa, nucleophilicity, redox potential, etc.) can be manipulated. Thus, methods to site-specifically label nucleic acids with one or a few functional groups attached to the fifth and sixth nucleotides of an expanded genetic alphabet would enable less biased selections and potentially the construction of more protein-like environments.

The development of an efficiently replicated and transcribed unnatural base pair would make possible the site-specific modification of DNA and RNA. While the four letter genetic alphabet based on complementary hydrogen-bonding (H-bonding) is conserved throughout nature, and orthogonal H-bonding patterns have been used to design unnatural base pairs,26-29 we30-41 and others42-46 have demonstrated the potential of hydrophobic and packing forces to control the efficient and selective replication of unnatural base pairs. However, as with the natural nucleotides, the general use of an unnatural base pair for the site-specific labeling of DNA or RNA requires that the unnatural nucleotides bear linkers or other functionalities that allow different groups to be attached without ablating polymerase recognition.

Two of the most promising unnatural base pairs that we have developed are those formed between d5SICS and dMMO2 (d5SICS-dMMO2) or dNaM (d5SICS-dNaM) (Fig. 1A). Both unnatural base pairs can be amplified by PCR with good to excellent efficiency and fidelity using a variety of DNA polymerases, even when embedded within difficult to replicate sequences (manuscript submitted and Ref. 34,38,39). While d5SICS-dNaM is replicated and transcribed with greater efficiency, our efforts to develop an unnatural base pair for in vitro applications include both d5SICS-dNaM and d5SICS-dMMO2, because unlike the annular ring scaffold of dNaM, the dMMO2 scaffold may be modified with linkers at a position that is analogous to the C5 position of the natural pyrimidines.

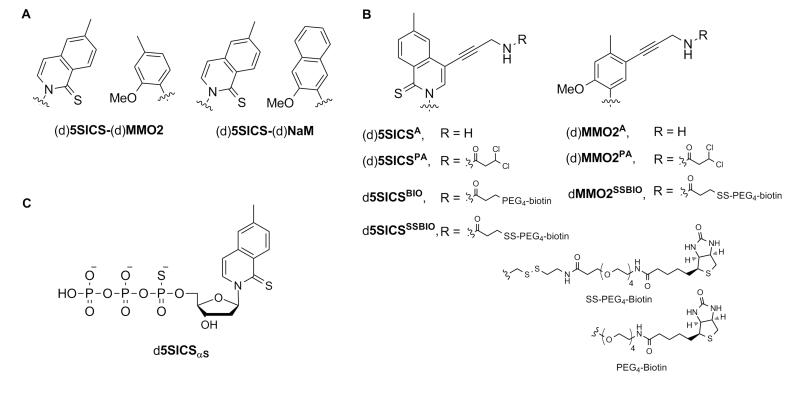

Figure 1.

(A) Parental unnatural base pairs; (B) linker modified analogs; and (C) α-phosphorothioate variant of d5SICSTP. Sugar and phosphate backbone are omitted for clarity in (A) and (B).

Here, we report the synthesis and evaluation of protected and free propargylamine linker-derivatized variants of both the deoxy- and ribo-nucleosides of MMO2 and 5SICS ((d)MMO2PA, (d)MMO2A, (d)5SICSPA, and (d)5SICSA), as well as the biotinylated deoxynucleotides dMMO2SSBIO, d5SICSBIO, and d5SICSSSBIO (Fig. 1B). The deoxynucleotides were characterized via both steady-state kinetics and PCR, and the ribonucleosides were characterized by the transcription of short model RNAs as well as a full length amber suppressor tyrosyl transfer RNA () from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii.47 Both the protected and free amino variants were evaluated to fully explore double labeling strategies, including those involving post-synthetic modification. The data reveals that the modifications of the unnatural nucleotides have varying effects on the different steps of replication and transcription and that the linkers are generally less perturbative within the (d)MMO2 scaffold. We also report the synthesis and evaluation of the α-phosphorothioate variant of d5SICSTP (d5SICSαSTP, Fig. 1C) and show that it is an efficient route to site-specifically introduce a thiolate for functional group attachment. Overall, we demonstrate that several of the modified nucleotides are sufficiently well recognized by polymerases to enable practical applications based on the site-specific labeling of nucleic acids with multiple different functionalities.

2. Results

2.1 Synthesis of modified unnatural nucleotides

With natural triphosphates, propargylamide linkers are relatively well tolerated by different polymerases.13,23 To explore the use of similar linkers with d5SICS-dNaM and d5SICS-dMMO2, we synthesized (d)5SICSPATP, (d)5SICSATP, d5SICSBIOTP, d5SICSSSBIOTP, (d)MMO2PATP, (d)MMO2ATP, and (d)MMO2BIOTP (Fig. 1B), as described in detail in the Supporting Information. Briefly, d5SICSPA was generated from the isosteryl compound, which was iodinated and then sulfonylated. The modified base was coupled to (2R,5R)-5-chloro-2-(((4-methylbenzoyl)oxy)methyl)tetrahydrofuran-3-yl 4-methylbenzoate, resulting in anomeric mixtures of nucleosides, with the pure β-anomer obtained by column chromatography. After removal of the toluoyl group, the iodo functionality was used to attach the dichloro acetyl protected propargylamine via Sonogashira coupling. Phosphorylation under Ludwig conditions48 provided d5SICSPATP, which was purified by anion exchange chromatography followed by HPLC, and then deprotected to provide d5SICSATP. The biotinylated analogs, d5SICSBIOTP and d5SICSSSBIOTP, were synthesized by coupling d5SICSATP to NHS-PEG4-biotin or NHS-SS-PEG4-biotin, respectively. To explore the use of a site-specifically incorporated backbone thiolate, d5SICSαSTP (Fig. 1C) was synthesized via the phosphorylation of the corresponding nucleoside in the presence of thiophosphoryl chloride.49 Note that this usually results in a mixture of Sp and Rp stereoisomers and that only the Sp is recognized by DNA polymerases.50 For dMMO2 derivatives, we iodinated the free nucleoside, which was synthesized as described previously,40 and then attached the dichloro acetyl protected propargylamine to provide the desired protected nucleoside.51 The nucleoside was then phosphorylated to provide dMMO2PATP, which was subsequently deprotected to provide dMMO2ATP. The cleavable biotinylated analog, dMMO2SSBIOTP, was synthesized via coupling of dMMO2ATP with NHS-SS-PEG4-biotin.

For the 5SICS ribonucleoside derivatives, 5-methyl isocarbostyril was first coupled with (2R)-2-((benzoyloxy)methyl)-5-oxotetrahydrofuran-3,4-diyl dibenzoate. The pure β anomer was purified from an anomeric mixture by column chromatography to provide the desired benzoyl protected nucleoside. Iodination, sulfonylation and benzoyl deprotection, followed by coupling with the dichloro acetyl propargylamine then provided 5SICSPA; phosphorylation provided 5SICSPATP, and deprotection provided 5SICSATP. For the MMO2 derivatives, the free nucleoside was synthesized as reported previously,39 iodinated, and then finally coupled to the dichloro acetyl protected propargylamine to produce MMO2PA. Phosphorylation and deprotection proceeded as with dMMO2A to provide MMO2PATP and MMO2ATP.

2.2 Steady-state kinetic analysis of linker modified unnatural base pair synthesis

To characterize polymerase recognition of the modified unnatural base pairs, we first explored the efficiency with which the exonuclease deficient Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I (Kf) inserts the linker-modified derivatives of d5SICSTP opposite dNaM (Table 1). For comparison, Kf inserts dATP opposite dT and d5SICSTP opposite dNaM with an efficiencies of 7.7 × 108 M−1min−1 and 2.1 × 108 M−1min−1, respectively (manuscript submitted). We found that Kf inserts d5SICSPATP with an efficiency of 8.3 × 106 M−1min−1. The 25-fold decreased insertion efficiency relative to d5SICSTP is due entirely to an elevated apparent KM. d5SICSBIOTP and d5SICSSSBIOTP were inserted less efficiently, with second order rate constants of 1.8 × 104 M−1min−1 and 4.5 × 104 M−1min−1, respectively, again, largely due to elevated apparent KM values. The insertion of d5SICSATP opposite dNaM by Kf is even less efficient, proceeding with a second order rate constant of only 4.5 × 103 M−1min−1. In this case, the reduced insertion efficiency relative to d5SICSTP is due to both a decreased apparent kcat and an increased apparent KM.

Table 1.

Steady state kinetic data for Kf-mediated insertion of modified triphosphates (dYTP) opposite their cognate nucleotide in the template (X).

| 5'–d(TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3'–d(ATTATGCTGAGTGATATCCCTCTXGCTAGGTTACGGCAGGATCGC) | ||||

|

| ||||

| X | Y | kcat (min−1) | KM (μM) |

kcat/KM × 105 (M−1

min−1) |

| T | Aa | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 0.0053 ± 0.0004 | 7700 |

| 5SICS | NaMa | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 580 |

| MM02a | 14 ± 2 | 35.8 ± 0.6 | 4.0 | |

| MMO2PA | 11 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 | 7.2 | |

| MMO2A | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 69 ± 8 | 0.97 | |

| MMO2SSBIO | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 45 ± 10 | 0.34 | |

| NaM | 5SICSa | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 0.039 ± 0.004 | 2100 |

| 5SICSPA | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 83 | |

| 5SICSA | 0.085 ± 0.05 | 19 ± 4 | 0.045 | |

| 5SICSαSc | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 0.42 ± 0.16 | 160 | |

| 5SICSBIO | 0.55 ± 0.13 | 31 ± 12 | 0.18 | |

| 5SICSSSBIO | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 29 ± 9 | 0.45 | |

Manuscript submitted.

b Below limit of detection.

Mixture of Sp and Rp diastereomers.

We then characterized the efficiency with which Kf inserts the linker-modified derivatives of dMMO2TP opposite d5SICS (Table 1). For comparison, Kf inserts dMMO2TP opposite d5SICS with an efficiency of 4 × 105 M−1min−1.31 Interestingly, we found that dMMO2PATP is inserted more efficiently (kcat/KM = 7.2 × 105 M−1min−1) than dMMO2TP, due to a 2-fold decrease in the apparent KM, while dMMO2ATP is inserted only slightly less efficiently (kcat/KM = 9.7 × 104 M−1min−1), due to small changes in both the apparent kcat and KM. Because d5SICSSSBIOTP was more efficiently recognized than d5SICSBIOTP, we also characterized dMMO2SSBIOTP and found that it is inserted by Kf opposite d5SICS with an efficiency of 3.4 × 104 M−1min−1, due to a 9-fold decrease in the apparent kcat.

2.3 PCR amplification of modified DNA

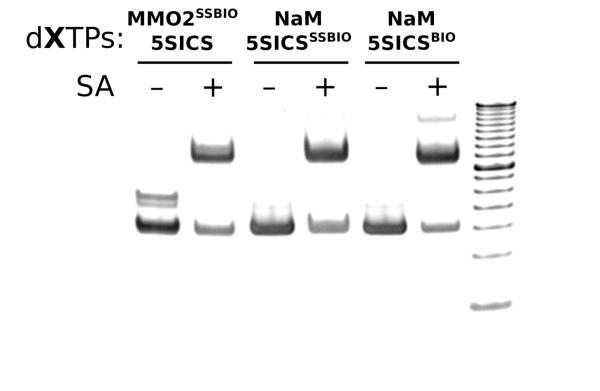

To characterize the effect of the linkers on the PCR amplification of DNA containing the unnatural base pair, we incorporated dMMO2-d5SICS into the middle of a 149-mer DNA duplex. The duplex DNA was then PCR amplified using DeepVent (exo+) DNA polymerase and a wide variety of different combinations of the modified triphosphates. The amplification level was determined for each combination of triphosphates, and then the amplicons were sequenced to determine replication fidelity (Table 2 and Fig. S1). In most cases, the amplification efficiency approaches that of the fully natural control (996-fold amplification) and the fidelity as measured by sequencing is in excess of 99% per doubling. The single exceptions are the amplifications with d5SICSATP, where the amplification level was only ~200-fold and the fidelity only ~90% per round. This agrees well with the steady-state kinetic data, which demonstrated that d5SICSATP insertion is inefficient. However, despite the slight reduction in steady-state insertion efficiency of d5SICSPATP and d5SICSαSTP, relative to d5SICSTP, no significant or systematic differences were apparent in amplification efficiency or fidelity with these three triphosphates. Fidelities of PCR amplifications involving biotin-modified triphosphates were also determined by streptavidin gel shift (Fig. 2). These fidelities paralleled those determined by sequencing, but were generally somewhat reduced. We attribute the differences to incomplete binding of streptavidin to the biotin tag due to its location in the middle of the large duplex where it is more obscured than when present at the terminus, as has been more commonly examined. This conclusion is consistent with the immobilization studies described below. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the biotin may have been lost by disulfide cleavage or exchange during PCR.

Table 2.

PCR fidelities and amplification efficiencies.a

| dXTPs incorporated | Amplification | Fidelity (sequencing)b | Fidelity (gel-shift)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| dNaM and d5SICS | 735 | >99.7 | - |

| dMMO2 and d5SICS | 609 | 99.6 | - |

| dNaM and d5SICSαSd | 662 | 99.6 | - |

| dMMO2PA and d5SICS | 489 | >99.7 | - |

| dMMO2A, d5SICS | 528 | 99.5 | - |

| dNaM and d5SICSPA | 888 | >99.7 | - |

| dNaM and d5SICSA | 160 | 91.1 | - |

| dMMO2PA and d5SICSPA | 960 | >99.7 | - |

| dMMO2A and d5SICSA | 279 | 90.9 | - |

| dMMO2A and d5SICSPA | 624 | 98.7 | - |

| dMMO2PA and d5SICSA | 167 | 91.4 | - |

| dMMO2A and d5SICSαSd | 378 | 99.4 | - |

| dMMO2SSBIO and d5SICS | 351 | 99.2 | 95.0 |

| dNaM and d5SICSSSBIO | 690 | >99.7 | 95.4 |

| dNaM and d5SICSBIO | 624 | >99.7 | 96.5 |

| dNaM only | 164e | -e | - |

| d5SICS only | 217e | -e | - |

See Materials and Methods for experimental details.

Calculated as average fidelities in both directions per doubling (see Materials and Methods for details).

Calculated from gel mobility assay (see text).

d5SICSαS was used as a mixture of Sp and Rp diastereomers.

Unnatural base pair lost during amplification.

Figure 2.

PCR fidelity determination via gel mobility. Based on the intensity of the DNA band that shifts in the presence of added streptavidin (SA), the biotin incorporation level is 65% for dMMO2SSBIO-d5SICS, 64% for dNaM-d5SICSSSBIO, and 72% for dNaM-d5SICSBIO. (Note that the slightly slower migrating band in lane 1 corresponds to unbiotinylated single-stranded DNA resulting from incomplete annealing after PCR.) The overall incorporation levels are converted to fidelities (Table 2) by normalizing by the number of doublings. A 50 bp DNA ladder is loaded in the rightmost lane.

2.4 Post-amplification modification of DNA

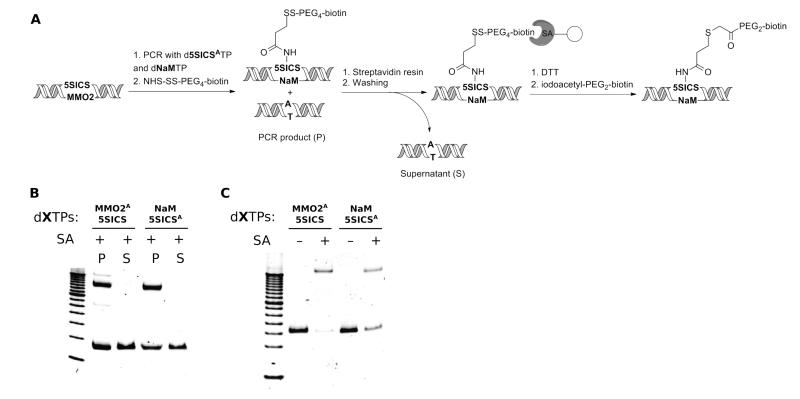

To examine the post-amplification labeling of DNA with a single functional group, we first explored strategies based on the PCR amplification of DNA with d5SICSATP and dNaMTP or d5SICSTP and dMMO2ATP (Fig. 3A, B). The resulting duplexes were biotinylated using sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin and the labeling efficiency was determined by streptavidin gel shift (Fig. 3D). We found that the reactions were complete after 1 h, with 60–70% of the duplexes modified. We next attempted to immobilize the biotin-labeled DNA to streptavidin solid support; however, unlike conventional end-labeling via biotinylated primers,52 we found that the nature and length of the spacer arm used to attach the biotin is critical. Virtually all of the biotinylated DNA was bound to the solid support when the linker was conjugated to biotin via a hydrophilic PEG4 spacer (29 Å spacer arm) or an SS-PEG4 spacer (37.9 Å spacer arm including a cleavable disulfide bridge, Fig. 4A, B) coupled to dMMO2A, but only small amounts of the DNA were bound when shorter and more hydrophobic spacers were used (for example, after conjugation to EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin which has a 24.3 Å spacer arm, data not shown). In the case of SS-PEG4-immobilized DNA, after washing to remove any contaminating natural DNA and cleaving the disulfide with DTT, the double-stranded DNA was efficiently released and then re-conjugated to iodoacetyl-PEG2-biotin. Gel-shift assays before and after the final conjugation revealed that greater than 50% of the duplexes were labeled (Fig. 4C).

Figure 3.

Post-amplification DNA labeling with single functional groups, using (A) d5SICSA, (B) dMMO2A, and (C) d5SICSαS. (D) Determination of labeling efficiency via streptavidin gel shift. The biotin incorporation level is 55% for dMMO2A-d5SICS, 70% for dNaM-d5SICSA and 70% for dNaM-d5SICSαS. A 50 bp DNA ladder is included in the rightmost lane of the gel. The faster migrating, strong band corresponds to dsDNA, while the slower migrating band corresponds to the 1:1 complex between dsDNA and streptavidin. The faint and most slowly migrating band in lane 6 corresponds to the 2:1 complex of dsDNA and streptavidin.

Figure 4.

(A) Immobilization of biotinylated dsDNA on streptavidin affinity resin. (B) Gel mobility assay of PCR amplicons labeled with NHS-SS-PEG4-biotin (P) compared to the unbound fraction remaining in the supernatant (S) after binding to the streptavidin solid support. Biotinylation levels are 53% for dMMO2A-d5SICS and 70% for dNaM-d5SICSA. A 100 bp DNA ladder is loaded in the leftmost lane. (C) Conjugation of dsDNA to iodoacetyl-PEG2-biotin after release from the streptavidin affinity resin via DTT treatment. Biotin incorporation levels are 89% for dMMO2A-d5SICS and 53% for dNaM-d5SICSA. A 50 bp DNA ladder is loaded in the leftmost lane. In (B) and (C), the faster migrating, strong band corresponds to dsDNA, while the slower migrating band corresponds to the 1:1 complex between dsDNA and streptavidin.

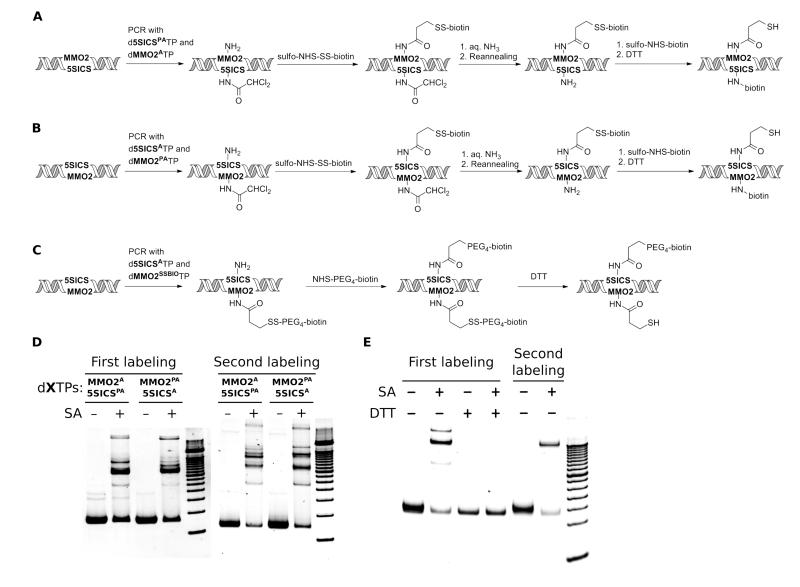

To explore the post-amplification labeling of DNA with two different groups we pursued two strategies. First, we examined the amplification of DNA containing either d5SICSPA-dMMO2A or d5SICSA-dMMO2PA (Fig. 5A, B). After amplification, the free amino groups were labeled with NHS-SS-PEG4-biotin and characterized by gel mobility. After propargylamine deprotection, the newly liberated amine was labeled with sulfo-NHS-biotin, with the labeling efficiency again characterized via gel mobility. Labeling efficiencies were 60–85% for each step of labeling via d5SICSPA-dMMO2A and d5SICSA-dMMO2PA (Fig. 5D). A second strategy for double labeling was based on the amplification of DNA using d5SICSATP and dMMO2SSBIOTP (Fig. 5C). The level of biotinylation via direct dMMO2SSBIO incorporation was characterized via streptavidin gel-shift, and a second biotin was then attached via coupling (DTT resistant) NHS-PEG4-biotin to d5SICSA. After treatment with DTT to selectively remove the biotin from dMMO2 (quantitative removal based on control reactions, Fig. 5E), the level of biotinylation at d5SICS was characterized. Labeling efficiencies were 85% and 68%, respectively, for the first and second steps via d5SICSA-dMMO2SSBIO (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5.

Post-amplification DNA labeling with two different functional groups, using (A) d5SICSPA-dMMO2A, (B) d5SICSA-dMMO2PA, and (C) d5SICSA-dMMO2SSBIO. (D) Efficiencies of first and second labeling of DNA from containing d5SICSPA-dMMO2A and d5SICSA-dMMO2PA. First labeling efficiencies are 61% for d5SICSPA-dMMO2A and 66% for d5SICSA-dMMO2PA, and second labeling efficiencies are 85% for d5SICSPA-dMMO2A and 78% for d5SICSA-dMMO2PA. A 100 bp ladder is loaded in the rightmost lane of each gel. (E) First and second labeling efficiencies of DNA containing d5SICSA-dMMO2SSBIO. The first labeling efficiency is 85% in the absence of DTT and 0% in the presence of DTT (due to linker cleavage). The second labeling efficiency is 68%. A 50 bp DNA ladder is loaded in the rightmost lane. In (D) and (E), the faster migrating, strong band corresponds to dsDNA, while the slower migrating band corresponds to the 1:1 complex between dsDNA and streptavidin. The faint and more slowly migrating bands correspond to higher order complexes of dsDNA and streptavidin.

2.5 Thiolation of DNA as a route to site-specific labeling

We also explored the use of d5SICSαSTP to site-specifically incorporate a reactive center into the backbone of DNA (Fig. 3C). As expected, steady-state kinetics revealed that the α-phosphorothioate is only slightly perturbative, with Kf inserting d5SICSαSTP opposite dNaM with an efficiency of 1.6 × 107 M−1min−1 (Table 1). To explore the use of labeling with d5SICSαS for post-amplification modification, we amplified DNA with dNaMTP and d5SICSαSTP. As expected, d5SICSαS-dNaM amplified with excellent efficiency and fidelity (Table 2). To explore post-synthetic labeling, the resulting duplex DNA was conjugated to EZ-Link iodoacetyl-PEG2-biotin. Gel-shift assays with streptavidin demonstrated that 70% of the duplexes were labeled (Fig. 3D), in good agreement with values reported in the literature for chemically synthesized α-phosphorothioate DNA.53,54

2.6 Site-specifically modified RNA

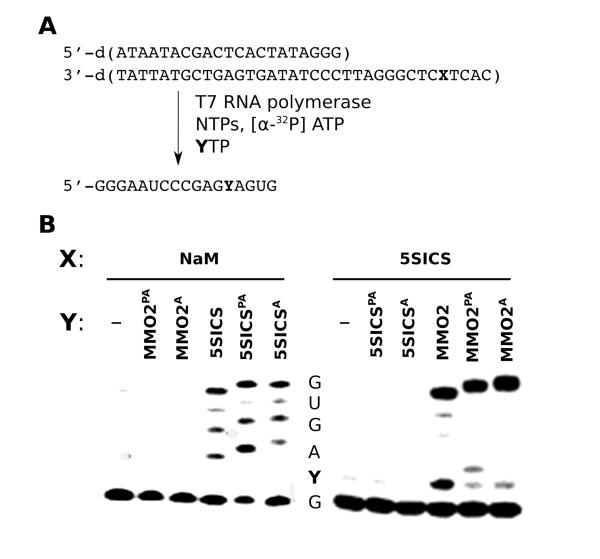

To explore the site-specific modification of RNA, we first characterized the ability of the RNA polymerase from T7 bacteriophage (T7 RNAP) to incorporate the linker-modified unnatural ribonucleotide triphosphates into 17 nt transcripts (Fig. 6A). We first examined the transcription of a template containing d5SICS with the natural ribotriphosphates and either MMO2PATP or MMO2ATP. Under the conditions employed, no full length product was observed in the absence of an unnatural triphosphate or in the presence of only a 5SICSTP derivative, and most of the truncated product corresponded to the termination of transcription immediately before d5SICS in the template (Fig. 6B). In contrast, when either MMO2PATP or MMO2ATP was present, we observed efficient conversion to full-length product. We then characterized transcription of the unnatural base pair in the opposite strand context by examining the ability of dNaM to template the transcription of RNA containing 5SICSPA or 5SICSA. Again, in the absence of an unnatural triphosphate, virtually no full-length product was observed, but addition of either cognate unnatural triphosphate, 5SICSPATP or 5SICSATP, resulted in the efficient production of the full-length transcription product (Fig. 6B). To characterize the fidelity of transcription, the experiments were repeated with [α-32P]ATP. The resulting internally labeled transcripts were digested to nucleoside 3’-phosphates, which were separated by 2D-TLC (Fig. S2), and the relative amount of each was quantified via densitometry (Table 3). Nucleotide-composition analysis confirmed that both unnatural nucleotides direct the transcription of RNA containing a cognate unnatural nucleotide with good selectivity. Interestingly, unlike with the replication of the deoxy-variants discussed above, we observed little difference in the efficiency or fidelity of 5SICSATP or 5SICSPATP incorporation.

Figure 6.

T7 RNAP transcription of site-selectively modified RNA. (A) Sequences of DNA template and transcription product. (B) Denaturing PAGE analysis with sequence indicated. Note that the bands for the linker-modified full length transcripts are shifted slightly more than those of the unlabeled full length product.

Table 3.

Nucleotide composition analysis of T7 RNAP transcription products.a

| Normalized composition of nucleotides incorporated 5’ to A during transcription of 17 nt RNA. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template | XTP | Ap | Gp | Cp | Up | Yp |

| d5SICS | dMMO2A | 1.02 ± 0.01 [1] |

1.94 ± 0.03 [2] |

n.d. [0]b | n.d. [0]b | 1.03 ± 0.02 [1] |

| d5SICS | dMMO2PA | 0.99 ± 0.03 [1] |

1.99 ± 0.03 [2] |

n.d. [0]b | n.d. [0]b | 1.01 ± 0.04 [1] |

| dNaM | d5SICSA | 1.03 ± 0.02 [1] |

2.00 ± 0.01 [2] |

n.d. [0]b | n.d. [0]b | 0.96 ± 0.02 [1] |

| dNaM | d5SICSPA | 1.07 ± 0.01 [1] |

1.95 ± 0.02 [2] |

n.d. [0]b | n.d. [0]b | 0.95 ± 0.01 [1] |

|

| ||||||

| Normalized composition of nucleotides incorporated 5’ to A during transcription of . |

||||||

| Template | XTP | Ap | Gp | Cp | Up | Yp |

|

| ||||||

| d5SICS | MMO2A | 4.06 ± 0.13 [4] |

3.03 ± 0.07 [3] |

5.91 ± 0.17 [6] |

0.98 ± 0.03 [1] |

1.02 ± 0.05 [1] |

| dNaM | 5SICSA | 4.16 ± 0.16 [4] |

3.10 ± 0.04 [3] |

5.86 ± 0.06 [6] |

1.01+0.02 [1] |

0.92 ± 0.04 [1] |

Values were determined by dividing the radioactivity observed for a particular monophosphate by the product of the total radioactivity and the expected number of nucleotides. Predicted values assuming 100% fidelity are show in brackets. The error reported is the standard deviation of at least three independent determinations.

Below detection limit.

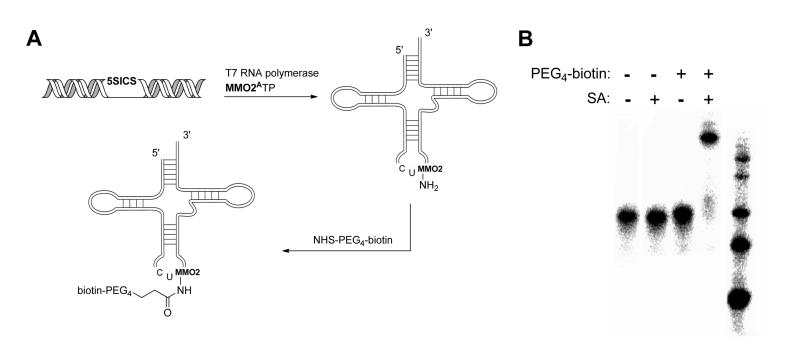

To further explore the T7 RNAP-mediated transcription of RNA for more practical applications, we synthesized a 96-nt DNA fragment encoding the 77-nt M. jannaschii with either dNaM or d5SICS at the third position of the anticodon (nucleotide 37). Full length product was efficiently produced in the presence of each natural triphosphate and the cognate unnatural triphosphate. However, unlike with the shorter model template, we were unable to identify conditions where product formation depended only upon the addition of the correct unnatural ribotriphosphate, likely due to the higher concentrations of natural NTPs required for efficient transcription of the longer RNA. Thus, we characterized the fidelity of transcription of the DNA template containing dNaM with 5SICSA and of the template containing d5SICS with MMO2A by 2D-TLC and densitometry (Table 3 and Fig. S3). The incorporation of MMO2A opposite d5SICS proceeded with excellent fidelity, while the incorporation of 5SICSA opposite dNaM proceeded with a more modest fidelity of 92%, suggesting that as with the deoxy variants and DNA polymerases, the free amine is tolerated better in the MMO2 scaffold than the 5SICS scaffold.

Finally, we explored the post-transcription site-specific labeling of RNA (Fig. 7). Purified product containing MMO2A at the third position of the anticodon loop was first unfolded by heating to 85 °C in presence of 20% DMSO and then reacted with NHS-PEG4-biotin at 37 °C for 1 hr. Based on streptavidin gel-shift, the efficiency of site-specific biotin attachment was greater than 75%.

Figure 7.

(A) Transcription of M. jannaschii site-selectively modified with MMO2A. (B) Gel mobility analysis of the modified containing MMO2A before (left two lanes) and after (right two lanes) coupling to NHS-PEG4-biotin. Coupling efficiency calculated as greater than 75%. A 25 bp DNA ladder is loaded in the rightmost lane.

3. Discussion

The development of an unnatural base pair is the first step towards creating semi-synthetic organisms with increased potential for information storage and retrieval, but would likely find more immediate use in different applications based on the production of site-specifically modified DNA or RNA. While functional unnatural base pairs that make site-specific labeling possible have recently been identified,29,33,39,43,45 little is known about their ability to accommodate the linkers required to attach the various functional groups of interest. Presumably, just as the development of the unnatural base pairs required extensive optimization, so too will development of the linkers. Previously, the Hirao group demonstrated the use of the same propargylamine linker used here, along with an acetamidohexanamide spacer, to attach a single fluorophore to a promising unnatural base pair within DNA, as well as to directly attach a biotin tag to a constituent nucleotide in RNA.43,45 To further explore the potential of linker-modified unnatural base pairs to site-specifically label DNA or RNA with one or more different moieties, either during or after enzymatic synthesis, we have explored the replication and transcription of d5SICS-dMMO2/dNaM with unnatural triphosphates bearing propargylamine-based linkers or an α-phosphorothioate.

The steady state kinetics with Kf polymerase revealed that replication of the unnatural base pair is sensitive to the structure of the linker, with the protected amino linker being the best accommodated. However, the effects of linker attachment were not the same for both nucleotides. While modification of dMMO2TP with the free or the dithiol-linked biotin modified linker reduced the efficiency of insertion opposite d5SICS 4- to 10-fold, modification with the protected amino linker actually increased insertion efficiency by 2-fold. In contrast, modification of d5SICSTP with any of the linkers examined resulted in reduced insertion efficiency opposite dNaM. Relative to d5SICSTP, the insertion efficiency of d5SICSBIOTP and d5SICSSSBIOTP is 3- to 4-orders of magnitude reduced, predominantly due to a reduction in the apparent binding of the triphosphate. The decrease was even larger for d5SICSATP due effects on both the apparent binding and turnover. In contrast, the insertion efficiency of d5SICSPATP opposite dNaM was reduced only 25-fold (due to reduced apparent binding).

Relative to the dMMO2, the greater sensitivity of d5SICSTP insertion to linker modification may result from its being more efficiently recognized, making it more susceptible to perturbation. However, the increase in insertion efficiency observed with dMMO2PA, and the fact that d5SICSATP is inserted less efficiently opposite dNaM than dMMO2ATP is inserted opposite d5SICS, suggests that the dMMO2 scaffold is more tolerant of the modifications examined. Perhaps, hydrophobic and packing interactions between the π-rich triple bond of the linker and the flanking nucleobases within the major groove are more favorable when accessed from the dMMO2 scaffold than from the d5SICS scaffold. This is consistent with the recently reported structure of the ternary complex of the large fragment of Taq DNA polymerase, which is homologous to Kf, bound to C5-propargylamide-modified dTTP, which shows that amide moiety of the linker forms a stabilizing hydrogen-bonding interaction with the side chain of polymerase residue R660.24 This Arg residue is conserved in Kf and because the ring structure of dMMO2 is similar in size and shape to a natural pyrimidine, it likely engages in a similar stabilizing interaction with the propargylamide linker when presented within the dMMO2 scaffold. Perhaps the extra aromatic ring of the d5SICS scaffold disrupts this stabilizing interaction. The same model likely accounts for the decreased tolerance of the free amine linker as it is expected to be protonated and thus to introduce electrostatic repulsion with the positively charged side chain of R660.

Regardless of the detailed rates with which the different triphosphates are inserted opposite their cognate unnatural nucleotide in the template, PCR experiments with DeepVent clearly demonstrate that different combinations of the propargylamine-modified nucleotides may be efficiently and site-selectively incorporated into DNA with reasonable fidelity. Thus, it should be straightforward to incorporate many different functional groups into duplex DNA via amide linkage to either unnatural triphosphate. Moreover, different combinations of unnatural triphosphates bearing protected or free amines may also be incorporated into DNA via PCR and thereby provide a versatile route to the post-synthetic labeling of DNA with two different functional groups, although with d5SICS, the most efficient replication requires that the amine is incorporated in a protected form. Thus, the most simple route to the labeling of DNA with two different functionalities would be either the use of triphosphates already bearing the functional groups of interest, or the amplification of DNA containing d5SICSPA-dMMO2A, followed first by modification of dMMO2A, deprotection, and finally modification of d5SICSA. The use of d5SICSSSBIO-dMMO2A also provides a convenient route to purify DNA containing the unnatural base pair, while the use of spacers that are longer and more hydrophilic to connect the linkers to the functional groups of interest facilitates post-amplification modification.

While the efficiency of d5SICSPA insertion is likely sufficient for practical labeling applications, we nonetheless demonstrated that the incorporation of d5SICSαSTP opposite dNaM, which proceeds with a 2-fold greater efficiency, also provides a convenient route to site-specific labeling via the modification of the α-phosphorothioate. While amplification with d5SICSPATP, d5SICSαSTP, or d5SICSTP all proceeded with similar efficiencies and fidelities within the sequence context examined, it is possible that other sequences may be more sensitive to the specific triphosphate used. It also should be noted that the α-phosphorothioate- and linker-based strategies are not mutually exclusive, and when combined should allow for a given site to be simultaneously modified with up to three different functional groups, one attached to the nucleobase of d5SICS, a second attached to the nucleobase of dMMO2, and a third attached to the backbone immediately 5’ to an unnatural nucleotide (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

General scheme for labeling DNA with three different functional groups and RNA with two different functional groups. R1 and R2 may correspond to either amide-coupled functional groups of interest, or a combination of protected and free amine linkers for further elaboration as described in the text.

As observed with the deoxy variants and Kf DNA polymerase, the linker-modified unnatural ribotriphosphates were found to be substrates for T7 RNAP. While we only characterized the transcription of the protected- and free-amine modified ribotriphosphates, the data suggest that just as with their deoxy counterparts, the direct attachment of different functional groups to the ribotriphosphates should be possible, providing a direct route to the transcription of RNA labeled with one or two functional groups. In addition, we demonstrated that the incorporation of ribotriphosphates bearing free amine groups should provide a general route to the post-transcription labeling of RNA with different functionalities of interest (Fig. 8). In contrast to the differences in replication observed with d5SICSATP and the other d5SICSTP derivatives, the transcription of short RNAs with 5SICS and 5SICSA appears similar, although fidelity was somewhat reduced during the incorporation of 5SICSA into the longer and more challenging to transcribe tRNA. Because alkylated α-phosphorothioates undergo strand cleavage in RNA, this route for backbone labeling is not possible, and the current methodology is limited to the site-specific labeling of RNA with only two different functional groups. However, the ability to induce site-specific RNA cleavage could also find interesting applications.55,56

Our goal is to expand the potential physical and functional properties of DNA and RNA without losing the inherent advantages possessed by these biopolymers relative to other materials. One property of DNA that has received much recent attention is its ability to act as a scaffold for the display of different functionalities with nanometer length-scale control for nanomaterial development.2,3 The site-specific labeling approach described here seems well suited to contribute to these efforts as many of the possible applications involve a level of distance control and functional group isolation that would be challenging or impossible to obtain with the higher functionalization density inherent to nucleotide-specific labeling approaches. From the perspective of creating (or evolving) controlled environments for molecular recognition or catalysis,6,7 relative to the nucleotide-specific labeling approach, the site-specific approach is more analogous to that employed by proteins, where the position of one or only a few reactive centers are controlled within an environment provided by the remainder of the oligonucleotide. Moreover, including only one or a few modified nucleotides in different members of an oligonucleotide library is less likely to incur unnecessary replication biases than more heavily or fully functionalized DNA. Efforts to deploy the linker modified unnatural base pairs in materials applications and for the selection of DNAs or RNAs with expanded functional potential are currently underway.

4. Materials and Methods

General

All reactions were carried out in oven-dried glassware under inert atmosphere and all solvents were dried over 4 Å molecular sieves with the exceptions of dichloromethane, which was distilled from CaH2, and tetrahydrofuran, which was distilled from sodium metal. All other reagents were purchased from Aldrich and Acros. 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on Varian Mercury 300, Varian Inova-400, or Bruker AMX-400 spectrometers. High-resolution mass spectroscopic data were obtained on an ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent 6200 Series) at the TSRI Open Access Mass Spectrometry Lab; MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Applied Biosystems Voyager DE-PRO System 6008) was performed at the TSRI Center for Protein and Nucleic Acid Research. Polynucleotide kinase and Kf were purchased from New England Biolabs, T7 RNAP from Takara USA, and [α-32P]ATP and [γ-32P]ATP from MP Biomedicals. DNA ladders were obtained from Invitrogen.

Oligonucleotide synthesis

Fully natural oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Oligonucleotides containing an unnatural nucleotide were prepared by the β-cyanoethyl phosphoramidite method on controlled pore glass supports (1 μmol) using an Applied Biosystems Inc. 392 DNA/RNA synthesizer. After automated synthesis, the oligonucleotides were cleaved from the support and deprotected by heating in aqueous ammonia at 55 °C for 12 h. After purification via 8 M urea 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the oligonucleotides were electroeluted and ethanol precipitated. Oligonucleotide concentration was determined by UV absorption.

Kinetic assay

Primer oligonucleotides were 5’-radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase and annealed to template oligonucleotides by heating to 95 °C followed by slow cooling to room temperature. Reactions were initiated by adding a solution of 2× dNTP solution (5 μL) to a solution containing Kf polymerase (0.10–1.23 nM) and primer template (40 nM) in 5 μL Kf reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, and 50 μg/mL acetylated BSA). After incubation at 25 °C for 3 – 10 min, the reactions were quenched with 20 μL of loading dye (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, and sufficient amounts of bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol). Reaction products were resolved by 8 M urea 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and gel band intensities corresponding to primer and extended primer were quantified by phosphorimaging (Storm Imager, Molecular Dynamics) and Quantity One (BioRad) software. Plots of kobs versus triphosphate concentration were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation using the program Origin (Microcal Software) to determine Vmax and KM. kcat was determined from Vmax by normalizing by the total enzyme concentration. Each reaction was run in triplicate and standard deviations for both kinetic parameters were determined.

PCR amplification

dsDNA template D1 was prepared as described previously34 (see Supporting Information for details), and amplified by PCR under the following conditions: 1 ng of the template, 1× ThermoPol reaction buffer (New England Biolabs), MgSO4 adjusted to 6.0 mM, 0.6 mM of dNTP, 0.2 mM of each unnatural triphosphates, 1 μM of each primers, and 0.03 U/μL of DeepVent (exo+, New England Biolabs) in an iCycler Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) with a total volume of 25 μL under the following thermal cycling conditions: 94 °C, 30 s; 48 °C, 30 s; 65 °C, 8 min, 14 cycles. Sybr Green I (Invitrogen) was added to the final concentration of 0.5× to monitor amplification by qPCR. Upon completion, a 5 μL aliquot was analyzed by 2% agarose gel and the remaining material was purified utilizing the PureLinkTM PCR Purification Kit (Invitrogen). Amplification efficiency was quantified by fluorescent dye binding (Quant-iT dsDNA HS Assay kit, Invitrogen) and fidelity was quantified by either sequencing (3730 DNA Analyzer, Applied Biosystems) (see Supporting Information and Malyshev et al.34) or gel mobility (see below).

Gel mobility assays

DNA samples (10 – 50 ng) were mixed with 1 μg of streptavidin (Promega) in phosphate labeling buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C, mixed with 5× non-denaturing loading buffer (Qiagen), and loaded on 10% non-denaturing PAGE. After running at 180 V for 25-40 min, the gel was soaked in 1× Sybr Gold Nucleic Acid Stain (Invitrogen) for 30 min and visualized using a Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR+ equipped with 520DF30 filter (Bio-Rad). Strong bands corresponding to dsDNA (at ~150 bp) and the 1:1 complex between dsDNA and streptavidin (at ~400 bp) were apparent. Faint bands corresponding to higher order (slower migrating) complexes of DNA and streptavidin or from unbiotinylated, single-stranded DNA resulting from incomplete annealing after PCR in some cases were also apparent.

General procedures for post-amplification DNA labeling

For post-enzymatic synthesis labeling, dsDNA with a free amino group was incubated with 10 mM EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin or EZ-Link NHS-PEG4-biotin (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at rt in phosphate labeling buffer, and then purified using the Qiagen PCR purification kit. With either dMMO2PA or d5SICSPA, the amine first required deprotection, which was accomplished by overnight incubation in a concentrated aqueous ammonia solution at rt. Ammonia was removed via a SpeedVac concentrator (water aspirator followed by oil vacuum pump). To cleave the disulfide containing linkers (i.e. SS-biotin or SS-PEG4-biotin), dsDNA was treated with DTT (final concentration of 30 mM) for 1 hour at 37 °C. For backbone labeling, dsDNA with a backbone phosphorothioate was incubated with 25 mM EZ-Link iodoacetyl-PEG2-biotin (Thermo Scientific) in phosphate labeling buffer overnight at 50 °C, and products were purified with Qiagen PCR Purification Kit. All reactions manipulating attached biotin moieties were quantified by streptavidin gel-shift assays.

DNA immobilization on streptavidin solid support

Streptavidin SepharoseTM High Performance affinity resin (GE Healthcare) was washed twice with phosphate labeling buffer to remove ethanol. Site-specifically biotinylated dsDNA was added to the pre-washed resin and incubated with occasional gentle mixing. After 1 h, the supernatant was removed (and analyzed by gel shift mobility to confirm the absence of biotinylated DNA), and the resin was washed three times with phosphate labeling buffer to remove any unbound DNA. dsDNA was recovered via DTT treatment (final concentration of 30 mM) for 1 hour at 37 °C, followed by filtration and purification with the Qiagen PCR Purification Kit.

Transcription experiments

For the transcription of short, 17 nt RNAs, the 35 nt DNA template 5’-CACTXCTCGGGATTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTAT (X = d5SICS or dNaM) and 21 nt DNA primer 5’-ATAATACGACTCACTATAGGG were annealed in a 1:1 ratio in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 10 mM NaCl, by heating at 95 °C for 3 min and slow cooling to 4 °C. Transcription was carried out at 37 °C in 10 μL reactions containing 100 nM DNA primer-template, 20 μM NTP, 0.25 mCi [α-32P]ATP, 50 U T7 RNAP (Takara), and 10 μM MMO2PATP, MMO2ATP, 5SICSPATP, or 5SICSATP in 1× Takara buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine). All solutions were prepared with DEPC-treated and nuclease-free sterilized water (Fisher Bioreagents). After incubation for 2 hr at 37 °C, the reactions were quenched by addition of gel loading dye solution (10 μL of 10 M urea, 0.05% bromophenol blue). This mixture was heated at 75 °C for 3 min, and then separated on a 7 M urea 20% polyacrylamide gel using 1× TBE buffer. The gel was removed from the apparatus and radioactivity was quantified by phosphorimaging (overnight exposure) using ImageQuant (Quantity One®).

For transcription of M. jannaschii , the template strand 5'-TGG TCC GGC GGG CCG GAT TTG AAC CAG CGC CAT GCG GAT TXA GAG TCC GCC GTT CTG CCC TGC TGA ACT

ACC GCC GGT ATA GTG AGT CGT ATT ATC (X = d5SICS or dNaM) and the non-template strand 5'- GAT AAT ACG ACT CAC TAT ACC GGC GGT AGT TCA GCA GGG CAG AAC GGC GGA CTC TAA ATC CGC ATG GCG CTG GTT CAA ATC CGG CCC GCC GGA CCA were annealed in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 10 mM NaCl, by heating at 95 °C for 3 min and cooling to 4 °C. Transcription was carried out at 37 °C in 20 μL reactions containing 2 μM DNA primer-template, 1 mM NTP, 0.25 mCi [α-32P]ATP (MP Biomedicals, LLC, Solon, OH), 50 U T7 RNAP (Takara Bio Inc.), and 1 mM MMO2ATP or 5SICSATP in 1× Takara buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 8 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine). All solutions were prepared with DEPC treated and nuclease-free sterilized water (Fisher Bioreagents). After incubation for 3 hr at 37 °C, the reaction was quenched by the addition of gel loading dye solution (20 μL of 10 M urea, 0.05% bromophenol blue). This mixture was heated at 75 °C for 3 min, and then separated on a 7 M urea 12% polyacrylamide gel using 1× TBE buffer. The gel was removed from the apparatus and radioactivity was quantified by phosphorimaging (overnight exposure) using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics).

Transcription fidelity was characterized by 2D TLC analysis. Briefly, gels containing transcription products were imaged (overnight exposure with Kodak X-OmatAR5 film), and the image was used to identify the radioactive spots corresponding to the full-length [32P]-RNA transcripts. These portions of the gel were then excised and transferred to 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes for passive elution (6–12 hours) at room temperature with 400 μL of sterilized water. Eluted full-length products were precipitated with cold ethanol (1.2 mL), CH3COONa (0.3 M, 20 μL) and E. coli tRNA (1 mM, 1 μL, Sigma Aldrich) for 2 hr. After centrifugation, the ethanol was removed and the product was evaporated to dryness with a SpeedVac concentrator. The transcripts were digested with RNaseI (10 U, 1 μL, Epicentre, WI) in 2 μL 10× RNaseI dilution buffer in a final volume of 20 μL at 37 °C for 120 min. The digestion products were analyzed by 2D TLC using high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) plates (100 × 100 mm) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with the following developing solvents: isobutyric acid-ammonia-water (66:1:33 v/v/v) for the first dimension, and sodium phosphate (0.1 M pH 6.8), ammonium sulfate, n-propanol (100:60:2 v/w/v) for the second dimension. The products on the gels and the TLC plates were analyzed by phosphorimaging using ImageQuant (Quantity One®).

For post-transcriptional labeling of , the purified full length RNA containing MMO2A (60 μL, 2.2 ng/μL) was mixed with 15 μL of DMSO, heated at 85 °C for 5 min, and cooled immediately on ice. The resulting solution was incubated with EZ-Link NHS-PEG4-biotin (Thermo Scientific) (1.5 mg) in 30 μL 4× phosphate labeling buffer for 1 hr at 37 °C. After ethanol precipitation, 10% of the resulting material (3 μL) was mixed with 3 μL of 5× denaturing loading buffer, heated to 85 °C, cooled on ice, mixed with 3 μL of streptavidin (1 mg/mL), and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The efficiency of labeling was determined by streptavidin gel-shift on a 7 M urea 15% polyacrylamide gel using 1× TBE buffer (180 V for 25-40 min).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institute for Health (GM060005).

Footnotes

Supporting information available. Nucleoside synthesis and characterization as well as details of kinetic experiments, sequencing, and transcription analysis.

References

- 1.Benner SA, Sismour AM. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H, Yang R, Yang L, Tan W. ACS Nano. 2009;3:2451–2460. doi: 10.1021/nn9006303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen T, Shukoor MI, Chen Y, Yuan Q, Zhu Z, Zhao Z, Gulbakan B, Tan W. Nanoscale. 2011;3:546–556. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00646g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruigrok VJ, Levisson M, Eppink MH, Smidt H, van der Oost J. Biochem. J. 2011;436:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyduk T. Biophys. Chem. 2010;151:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syed MA, Pervaiz S. Oligonucleotides. 2010;20:215–224. doi: 10.1089/oli.2010.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:2672–2689. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonnberg H. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1065–1094. doi: 10.1021/bc800406a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paredes E, Evans M, Das SR. Methods. 2011;54:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavergne T, Bertrand JR, Vasseur JJ, Debart F. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:9135–9138. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battersby TR, Ang DN, Burgstaller P, Jurczyk SC, Bowser MT, Buchanan DD, Kennedy RT, Benner SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9781–9789. doi: 10.1021/ja9816436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brakmann S, Lobermann S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2001;40:1427–1429. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1427::AID-ANIE1427>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gourlain T, Sidorov A, Mignet N, Thorpe SJ, Lee SE, Grasby JA, Williams DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1898–1905. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jager S, Rasched G, Kornreich-Leshem H, Engeser M, Thum O, Famulok M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:15071–15082. doi: 10.1021/ja051725b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuwahara M, Nagashima J, Hasegawa M, Tamura T, Kitagata R, Hanawa K, Hososhima S, Kasamatsu T, Ozaki H, Sawai H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5383–5394. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehedi Masud M, Ozaki-Nakamura A, Kuwahara M, Ozaki H, Sawai H. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:584–588. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200200539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrin DM, Garestier T, Helene C. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1999;18:377–391. doi: 10.1080/15257779908043083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roychowdhury A, Illangkoon H, Hendrickson CL, Benner SA. Org Lett. 2004;6:489–492. doi: 10.1021/ol0360290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakthivel K, Barbas III CF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng. 1998;37:2872–2875. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2872::AID-ANIE2872>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tasara T, Angerer B, Damond M, Winter H, Dorhofer S, Hubscher U, Amacker M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2636–2646. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollenstein M, Hipolito CJ, Lam CH, Perrin DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1638–1649. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Held HA, Benner SA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3857–3869. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SE, Sidorov A, Gourlain T, Mignet N, Thorpe SJ, Brazier JA, Dickman MJ, Hornby DP, Grasby JA, Williams DM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1565–1573. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obeid S, Baccaro A, Welte W, Diederichs K, Marx A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21327–21331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013804107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Z, Waggoner AS. Cytometry. 1997;28:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horlacher J, Hottiger M, Podust VN, Hübscher U, Benner SA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:6329–6333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutz MJ, Held HA, Hottiger M, Hübscher U, Benner SA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1308–1313. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.7.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piccirilli JA, Krauch T, Moroney SE, Benner SA. Nature. 1990;343:33–37. doi: 10.1038/343033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Z, Chen F, Chamberlin SG, Benner SA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:177–180. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang GT, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14872–14882. doi: 10.1021/ja803833h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leconte AM, Hwang GT, Matsuda S, Capek P, Hari Y, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2336–2343. doi: 10.1021/ja078223d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leconte AM, Romesberg FE. In: Protein Engineering. RajBhandary C. K. a. U. L., editor. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2009. pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malyshev DA, Pfaff DA, Ippoliti SI, Hwang GT, Dwyer TJ, Romesberg FE. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:12650–12659. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malyshev DA, Seo YJ, Ordoukhanian P, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14620–14621. doi: 10.1021/ja906186f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuda S, Fillo JD, Henry AA, Rai P, Wilkens SJ, Dwyer TJ, Geierstanger BH, Wemmer DE, Schultz PG, Spraggon G, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10466–10473. doi: 10.1021/ja072276d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuda S, Leconte AM, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5551–5557. doi: 10.1021/ja068282b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMinn DL, Ogawa AK, Wu Y, Liu J, Schultz PG, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11585–11586. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo YJ, Hwang GT, Ordoukhanian P, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3246–3252. doi: 10.1021/ja807853m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seo YJ, Matsuda S, Romesberg FE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5046–5047. doi: 10.1021/ja9006996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seo YJ, Romesberg FE. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2394–2400. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu C, Henry AA, Romesberg FE, Schultz PG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng. 2002;41:3841–3844. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021018)41:20<3841::AID-ANIE3841>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirao I. Curr. Op. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:622–627. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirao I, Kimoto M, Mitsui T, Fujiwara T, Kawai R, Sato A, Harada Y, Yokoyama S. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:729–735. doi: 10.1038/nmeth915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirao I, Mitsui T, Kimoto M, Yokoyama S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15549–15555. doi: 10.1021/ja073830m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimoto M, Kawai R, Mitsui T, Yokoyama S, Hirao I. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:e14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitsui T, Kitamura A, Kimoto M, To T, Sato A, Hirao I, Yokoyama S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5298–5307. doi: 10.1021/ja028806h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu CC, Schultz PG. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:413–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.105824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ludwig J, Eckstein F. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:631–635. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burgess K, Cook D. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2047–2060. doi: 10.1021/cr990045m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckstein F. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985;54:367–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawai R, Kimoto M, Ikeda S, Mitsui T, Endo M, Yokoyama S, Hirao I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17286–17295. doi: 10.1021/ja0542946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rapley R. The Nucleic Acid Protocols Handbook. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fidanza JA, Ozaki H, McLaughlin LW. Methods Mol. Biol. 1994;26:121–143. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59259-513-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Padmanabhan S, Coughlin JE, Zhang G, Kirk CJ, Iyer RP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:1491–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gish G, Eckstein F. Science. 1988;240:1520–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.2453926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strobel SA, Shetty K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:2903–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.