Summary

Objective

Hedgehog signalling is mediated by the primary cilium and promotes cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis. Primary cilia are influenced by pathological stimuli and cilia length and prevalence are increased in osteoarthritic cartilage. This study aims to investigate the relationship between mechanical loading, hedgehog signalling and cilia disassembly in articular chondrocytes.

Methods

Primary bovine articular chondrocytes were subjected to cyclic tensile strain (CTS; 0.33 Hz, 10% or 20% strain). Hedgehog pathway activation (Ptch1, Gli1) and A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin Motifs 5 (ADAMTS-5) expression were assessed by real-time PCR. A chondrocyte cell line generated from the Tg737ORPK mouse was used to investigate the role of the cilium in this response. Cilia length and prevalence were quantified by immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy.

Results

Mechanical strain upregulates Indian hedgehog expression and activates hedgehog signalling. Ptch1, Gli1 and ADAMTS-5 expression were increased following 10% CTS, but not 20% CTS. Pathway activation requires a functioning primary cilium and is not observed in Tg737ORPK cells lacking cilia. Mechanical loading significantly reduced cilium length such that cilia became progressively shorter with increasing strain magnitude. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), a tubulin deacetylase, prevented cilia disassembly and restored mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling and ADAMTS-5 expression at 20% CTS.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates for the first time that mechanical loading activates primary cilia-mediated hedgehog signalling and ADAMTS-5 expression in adult articular chondrocytes, but that this response is lost at high strains due to HDAC6-mediated cilia disassembly. The study provides new mechanistic insight into the role of primary cilia and mechanical loading in articular cartilage.

Keywords: Chondrocyte, Cilia length, Primary cilium, Hedgehog, ADAMTS-5

Introduction

The primary cilium is a singular, immotile organelle elaborated by the majority of cells during interphase1. Structurally the cilium comprises a centriole-derived basal body from which projects an axoneme composed of acetylated microtubules. The axoneme is sheathed in a specialised ciliary membrane and forms a compartment which functions as a hub for numerous signalling pathways such as Wnt2, PDGF-α3 and hedgehog signalling4–6. The majority of chondrocytes exhibit a primary cilium and the size of this signalling compartment is influenced by pathological stimuli, including mechanics and inflammatory cytokines7,8. This may be responsible for the increase in primary cilia length and prevalence observed in osteoarthritic cartilage9. Previous studies have established that the chondrocyte primary cilium is required for mechanotransduction10 and the response to osmotic loading11, with genetic inhibition of primary cilia assembly leading to the development of osteoarthritic-like cartilage12.

The primary cilium is assembled and maintained by intraflagellar transport (IFT), a microtubule based motility present in the axoneme. IFT conveys axonemal precursors and signalling proteins along the length of the cilium towards the distal tip and returns them to the basal body13. Genetic mutation of IFT proteins and/or the molecular motors that drive this process disrupt cilia structure and function and are responsible for a group of related disorders termed ciliopathies14. Given their shared requirement for IFT, a correlation is often observed between the length of the cilium and its function15–17. Indeed, Tran et al. reported that a 27% reduction in retrograde transport is sufficient to disrupt both cilia morphology and hedgehog signalling17. Alterations in cilia length have been reported in several pathological conditions including osteoarthritis (OA)9,18,19.

Hedgehog signalling regulates the activity of a family of bi-functional transcription factors called Gli proteins20. A functioning primary cilium is essential for this pathway5. In the absence of hedgehog ligands, Gli proteins are modified within the ciliary compartment promoting formation of transcriptional repressors5. Binding of the hedgehog ligand to its receptor, Patched (Ptch1), releases the repression of a second transmembrane protein Smoothened (Smo)5,6. Upon activation, Smo traffics into the cilium where it promotes the formation of Gli activators and the expression of hedgehog target genes4,5.

Hedgehog signalling is aberrantly activated in osteoarthritic cartilage where it promotes chondrocyte hypertrophy and the expression of catabolic enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP-13) and A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin Motifs 5 (ADAMTS-5) leading to cartilage degeneration21,22. The level of pathway activation correlates with the severity of the OA phenotype. Inhibiting hedgehog signalling attenuates disease severity in OA models highlighting the potential of this pathway as a therapeutic target21,22.

Indian hedgehog (Ihh) is the major hedgehog ligand expressed in cartilage and regulates chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation during development23. Ihh expression is increased in early cartilage lesions24 and in osteoarthritic cartilage in association with chondrocyte hypertrophy22. However the mechanisms responsible for this are unknown. While several in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that Ihh expression is regulated by mechanical stimuli during skeletal development25,26, the mechanosensitivity of this pathway has not been examined in healthy adult chondrocytes.

This study tests the hypothesis that hedgehog signalling is mechanosensitive in adult articular chondrocytes and examines the role of the primary cilium in this response. We show that mechanical strain promotes Ihh expression and hedgehog pathway activation. However, while mechanosensitive Ihh expression was found to be independent of ciliary function, pathway activation did not occur at high magnitude strain as a result of primary cilia disassembly. We identify a role for the tubulin deacetylase histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) in mechanosensitive cilia disassembly and show that inhibition of this enzyme prevents disassembly and restores mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling and ADAMTS-5 expression. Thus we reveal the chondrocyte primary cilia structure–function relationship and how this is modulated by mechanical loading. We propose that cilia disassembly is chondroprotective, reducing enzymatic cartilage degradation in response to high magnitude strain.

Methods

Cell isolation and culture

Forefeet from freshly slaughtered adult bovine steers (aged 18–24 months) were obtained from a local abattoir and primary articular chondrocytes isolated by enzymatic digestion as previously described27. Chondrocytes were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS), 1.9 mM l-glutamine, 96 U/ml penicillin, 96 μg/ml streptomycin, 19 mM 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer, and 0.74 mM l-ascorbic acid (Sigma Aldrich). Cells were seeded onto collagen I coated BioFlex® membranes and cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 6 days without passage.

Conditionally immortalised wild-type (WT) and Tg737ORPK (ORPK) mouse chondrocyte cell lines were generated as previously described10. Chondrocytes were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FCS, 88 U/ml penicillin, 90 μg/ml streptomycin and 2.5 mM l-glutamine. Immortalised cells were maintained under permissive conditions at 33°C, 5% CO2 in the presence of 10 nM interferon-γ (IFN-γ). For experiments, cells were seeded onto collagen I coated BioFlex® membranes and cultured for 24 h then washed and cultured under non-permissive conditions at 37°C without IFN-γ for 4 days. WT chondrocytes express Acan and Col2a and have been shown to exhibit mechanosensitive gene expression and proteoglycan production in response to dynamic compression10.

Application of mechanical strain

Uniform, equibiaxial cyclic tensile strain (CTS) was applied to chondrocytes using the Flexcell® FX4000-T system with circular loading posts with a diameter of 25 mm. To ensure only chondrocytes that experience a uniform strain field were studied; the cells at the periphery of each well were removed by aspiration 3 days prior to loading. Cells were subjected to 10% or 20% CTS for 1 h at 0.33 Hz under serum-free conditions. For unstrained controls, chondrocytes were cultured in an identical manner but without the application of strain.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Chondrocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min followed by detergent permeabilisation with 0.5% Triton X-100 and blocking for 1 h with 5% goat serum. The BioFlex™ membrane was excised and cells were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight in a humidified chamber. Mouse monoclonal anti-acetylated tubulin, clone 611B-1 (1:2000; Sigma Aldrich) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Arl13b (1:2000; Proteintech) were used for the detection of the ciliary axoneme. Rabbit polyclonal anti-HDAC6 (1:250, Abcam) was used for the detection of HDAC6 in the cilium. Following repeated washing in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), cells were incubated with appropriate Alexa488 and Alexa594 conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature and nuclei were detected with 1 ug/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Following repeated washing, membranes were mounted with Prolong gold reagent (Molecular Probes).

Samples were imaged using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope with a 63×, 1.3-NA lens (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Primary cilia length and prevalence were measured as described previously8. In summary, confocal Z-stacks were obtained throughout the entire cellular profile with a Z-step size of 0.5 μm and an image format of 1024 × 1024 pixels. This produced an xy pixel size of 0.232 μm × 0.232 μm. Z-stacks were reconstructed and an xy maximum intensity projection generated for measurement of cilia prevalence and length using Image J software.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from individual wells immediately after loading using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA integrity was confirmed by gel electrophoresis. For each sample 1 μg total RNA was converted to cDNA using the Quantitect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This kit incorporates a DNase step for removal of genomic DNA prior to cDNA synthesis. Both RNA and cDNA were quantified using the Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (LabTech, East Sussex, UK).

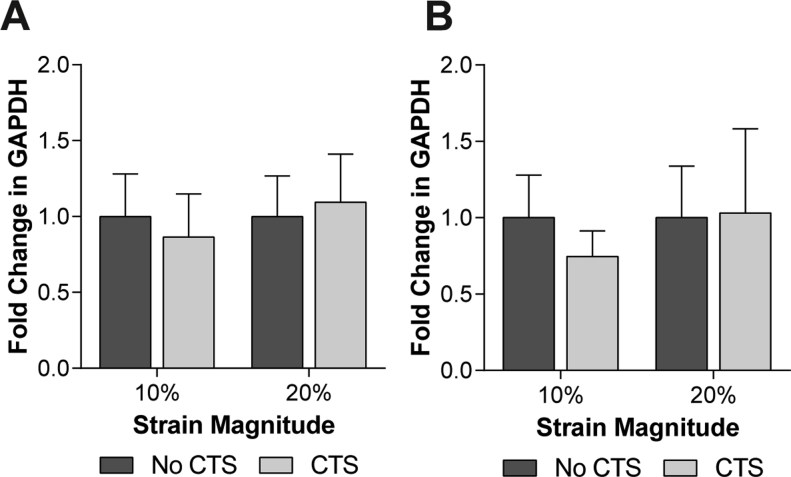

For real-time PCR, reactions were performed in 10 μl volumes containing 1 μl cDNA (diluted 1:2), 5 μl KAPA SYBR® FAST Universal 2× qPCR Master Mix (KAPA Biosystems) containing SYBER-green dye, 0.2 μl ROX reference dye and 1 μl optimised primer pairs (listed in Table I). An annealing temperature of 60°C was used for PCR reactions and fluorescence data was collected using the MX3000P QPCR instrument (Stratagene). Samples were run in triplicate to minimise pipetting errors. Data was analysed using the relative standard curve method and target genes were normalised to GAPDH28,29, the expression of which was not significantly altered by the experimental conditions used in this study (see Fig. S1).

Table I.

Primer sequence information

| Accession no. | Gene | Sequence | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| NM_001076870 | Indian Hedgehog | F-GCTTCGACTGGGTGTATTACG R-GTCTCGATGACCTGGAAAGC |

Bovine |

| NM_001205879 | Patched 1 | F-ATGTCTCGCACATCAACTGG R-TCGTGGTAAAGGAAAGCACC |

Bovine |

| NM_001099000.1 | Gli1 | F-ACCCCACCACCAGTCAGTAG R-TGTCCGACAGAGGTGAGATG |

Bovine |

| NM_001166515 | ADAMTS-5 | F-GCCCTGCCCAGCTAACGGTA R-CCCCCGGACACACACGGAA |

Bovine |

| NM_001034034 | GAPDH | F-GACAAAATGGTGAAGGTCGG R-TCCACGACATACTCAGCACC |

Bovine/Murine |

| NM_010544.2 | Indian Hedgehog | F-GCTTCGACTGGGTGTATTACG R-GTCTCGATGACCTGGAAAGC |

Murine |

| NM_008957.2 | Patched 1 | F-GCAGAGGACTTACGTGGAGG R-CTGACAGTGCAACCAACAGG |

Murine |

| NM_010296.2 | Gli1 | F-CCAAGCCAACTTTATGTCAGGG R-AGCCCGCTTCTTTGTTAATTTGA |

Murine |

| NM_011782.2 | ADAMTS-5 | F-GGATGTGACGGCATTATTGG R-GGGCTAAGTAGGCAGTGAAT |

Murine |

Data analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using Graph Pad Prism 6.01 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data is presented as mean values with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For primary articular chondrocytes an experiment is defined as follows: cells were isolated from a pool of cartilage taken from a minimum of three donors to ensure a heterogeneous population of cells for each experiment. For work using cell lines an experiment is defined as a single passage of the cells. Experiments were performed in duplicate unless otherwise stated. For real-time PCR, each analysis comprised 6–10 replicates per condition (defined as n through the manuscript) where one replicate was a single well of a tissue culture plate. For primary cilia length, prevalence and Ki-67 data, a replicate or n is defined as a single field of cells. Each analysis comprised 15–20 replicates per condition (defined as n through the manuscript). Following normality testing (Shapiro–Wilk test) data was assessed by unpaired Student's t test or by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t tests. Comparisons were made between treated or strained samples and the experimental control. Differences were considered statistically significant at ≤0.05.

Results

Mechanical strain upregulates Ihh and activates hedgehog signalling in primary chondrocytes in a strain dependent manner

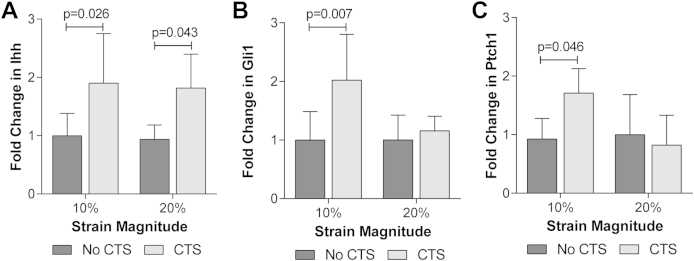

In primary bovine articular chondrocytes, the expression of Ihh was increased in response to both 10% and 20% CTS relative to the unstrained (noCTS) control [10%: P = 0.026; 20%: P = 0.043; Fig. 1(A)]. Hedgehog pathway activation was assessed by monitoring changes in the expression of Gli1 and Ptch1. The expression of these genes was increased following 10% CTS [Gli1: P = 0.007; Ptch1: P = 0.046; Fig. 1(B) and (C)] indicative of pathway activation. Despite the induction of Ihh, pathway activation was not observed in response to 20% CTS [Gli1: P > 0.999; Ptch1: P > 0.999; Fig. 1(B) and (C)].

Fig. 1.

Mechanical strain upregulates Ihh expression and activates hedgehog signalling in articular chondrocytes. Changes in (A) Ihh, (B) Gli1 and (C) Ptch1 gene expression for primary bovine articular chondrocytes subjected to CTS for 1 h at 10% or 20% strain. Data is expressed as a fold change relative to the mean of the unstrained (noCTS) control group. Data represents mean ± CI (n = 8). Data was analysed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrected t-test.

The primary cilium is required for mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling in chondrocytes

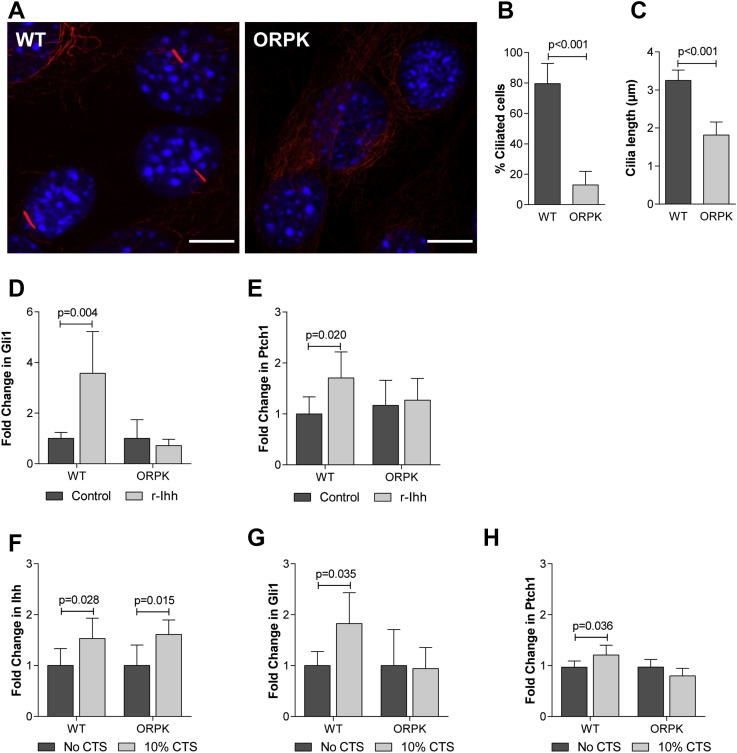

An immortalised chondrocyte cell line generated from the Tg737ORPK mouse was used to investigate the role of the primary cilium in the mechanical regulation of hedgehog signalling. In ORPK chondrocytes primary cilia are disrupted due to a hypomorphic mutation in the Ift88 gene, the protein product of which is essential for IFT and thus cilia assembly and maintenance8,10. In WT cultures 80 ± 13% of cells elaborated a primary cilium with a mean length of 3.25 ± 0.3 μm [Fig. 2(A)–(C)]. By contrast, only 13 ± 9% of cells exhibited a cilium in ORPK chondrocyte cultures [Fig. 2(B)]. Furthermore, the cilia elaborated by ORPK cells were shorter than those in WT cells with a mean length of 1.81 ± 0.3 μm [P < 0.001; Fig. 2(C)].

Fig. 2.

The primary cilium is required for chondrocyte hedgehog signalling. (A) Representative confocal maximum intensity Z projections showing primary cilia immunofluorescently labelled in WT and ORPK chondrocytes cultured in the absence of strain. The cilium was labelled with antibodies directed to acetylated α-tubulin (red) while nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20 μm. (B) Primary cilia prevalence (n = 10) and (C) primary cilia length for WT and ORPK chondrocytes (n = 10). Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t test. Changes in (D) Gli1 and (E) Ptch1 gene expression for WT and ORPK chondrocytes treated with 1 μg/ml r-Ihh for 24 h. Changes in (F) Ihh, (G) Gli1 and (H) Ptch1 gene expression for WT and ORPK chondrocytes subjected to 10% CTS for 1 h. Gene expression data is expressed as a fold change relative to the mean of the untreated or unstrained control group. Data is presented as mean ± CI (n = 6–10). Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrected t-test.

Chondrocytes were treated for 24 h with 1 μg/ml recombinant Indian hedgehog ligand (r-Ihh) to establish the role of the cilium in ligand-mediated hedgehog signalling [Fig. 2(D) and (E)]. In WT chondrocytes, the expression of Gli1 and Ptch1 was increased in response to r-Ihh treatment confirming pathway activation [Gli1: P < 0.001; Ptch1: P = 0.020; Fig. 2(D) and (E)]. In ORPK chondrocytes the expression of these genes was not altered by r-Ihh treatment [Gli1: P > 0.999; Ptch1: P > 0.999; Fig. 2(D) and (E)] indicating the cilium/IFT is required for this response. To determine the role of the cilium in mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling, WT and ORPK chondrocytes were subjected to 10% CTS for 1 h [Fig. 2(F)–(H)]. The expression of Ihh was increased by CTS in both WT and ORPK chondrocytes relative to the noCTS control [WT: P = 0.028; ORPK: P = 0.015; Fig. 2(F)]. In WT chondrocytes, Gli1 expression was increased following 10% CTS (P = 0.036) suggesting hedgehog signalling is activated [Fig. 2(G)]. Ptch1 expression was also increased although the difference was not significant, this suggests the pathway is activated to a lesser extent in response to mechanical strain compared to r-Ihh treatment [Fig. 2(H)]. In ORPK chondrocytes, Gli1 and Ptch1 expression were not altered by strain (Gli1: P > 0.999; Ptch1: P > 0.1658). Thus it appears that the primary cilium is not required for mechanosensitive Ihh expression but is necessary for signal transduction and pathway activation.

Primary cilia disassemble in a strain dependent manner

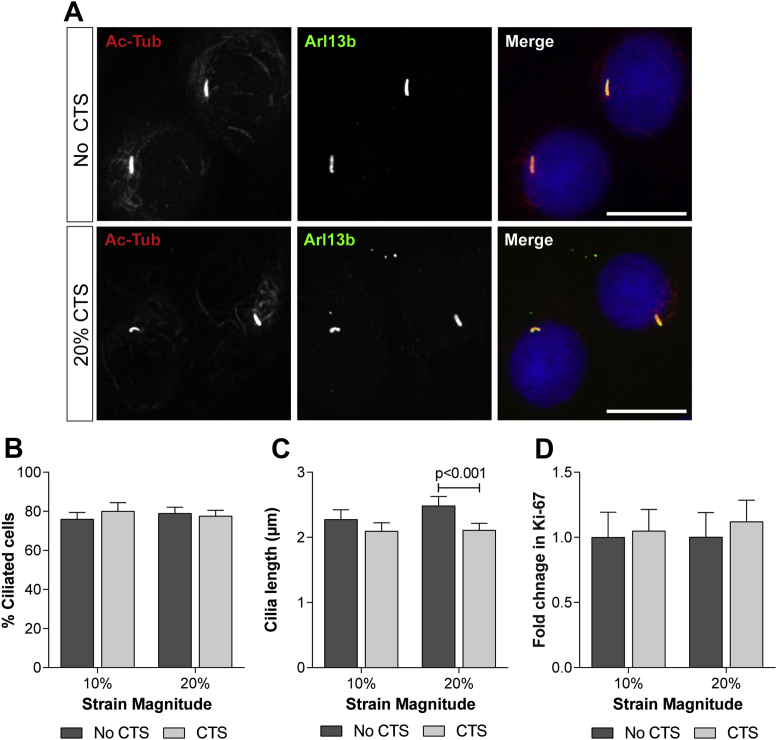

Previous studies have shown that mechanical stimuli trigger cilia disassembly in numerous cell types including chondrocytes7,15,30,31. Given the importance of the cilium for chondrocyte hedgehog signalling, changes in cilia length and prevalence were monitored in response to strain by confocal microscopy. Primary bovine articular chondrocytes were subjected to strain then immediately fixed and processed for immunofluorescent labelling. Primary cilia were labelled for the axoneme marker acetylated α-tubulin and for Arl13b, which labels the ciliary membrane. Within the cilium Arl13b and acetylated α-tubulin fully overlapped [Fig. 3(A)]. Primary cilia prevalence was not altered in response to mechanical strain [Fig. 3(B)]. However, primary cilia length was significantly reduced in cells subjected to 20% CTS relative to the noCTS control [P < 0.001; Fig. 3(A) and (C)]. Mean cilium length was reduced from 2.48 μm ± 0.1 to 2.11 μm ± 0.1, a disassembly of approximately 15.1% which was highly reproducible.

Fig. 3.

Primary cilia disassemble in response to mechanical strain. (A) Representative confocal maximum intensity Z projections of primary bovine articular chondrocytes showing primary cilia following 1 h 20% CTS and the noCTS control. Acetylated α-tubulin (red); Arl13b (green) and nuclei (blue). Scale bar represents 20 μm. Primary cilia (B) prevalence and (C) length for primary articular chondrocytes subjected to CTS for 1 h at 10% and 20% strain. (D) The % of Ki-67 positive cells in unstrained cells and those subjected to 10% and 20% CTS. Data is expressed as the fold change relative to the mean of the unstrained samples and represents mean ± CI (n = 15–20). Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrected t-tests.

Primary cilia assembly and disassembly are intrinsically linked with the cell cycle and cilia resorption occurs upon cell cycle re-entry1. Cell-cycle status was examined using the nuclear marker Ki-67. Nuclear Ki-67 is expressed by cells during all active phases of the cell cycle (G1, S, G2, and mitosis), but is absent from resting cells (G0). Bovine articular chondrocytes were subjected to CTS for 1 h then cultured for a further 24 h prior to fixation. There was no difference in the proportion of Ki-67 positive cells between strained and unstrained groups [Fig. 3(D)] indicating ciliary resorption does not occur as a result of cell cycle re-entry. Moreover, there was no significant difference in % viability between strained and unstrained cells which remained above 98% throughout the course of the study.

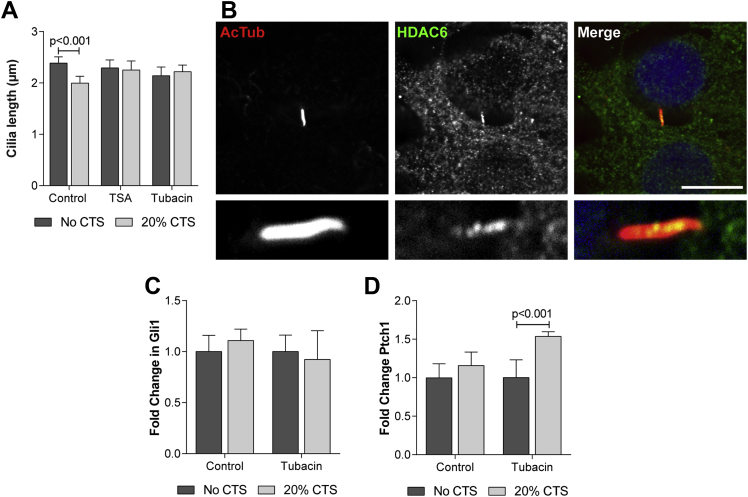

Mechanosensitive cilia disassembly requires HDAC6

Previous studies have implicated the tubulin deacetylase HDAC6 in cilia resorption which is proposed to modulate cilia length through the deacetylation and subsequent destabilisation of ciliary microtubules18,32,33. To explore the role of HDAC6 in mechanosensitive cilium disassembly, HDAC6 function was inhibited using trichostatin A (TSA) and tubacin. TSA is a broad spectrum HDAC inhibitor while tubacin specifically targets the tubulin deacetylase domain of HDAC633. Following protocols used in previous studies, primary bovine articular chondrocytes were pre-incubated with 7 nM TSA, 500 nM tubacin or the carrier DMSO (control) for 3 h prior to and during the application of 20% CTS34. Both TSA and tubacin prevented strain-induced cilium disassembly indicating HDAC6 is required for this response [Fig. 4(A)]. Consistent with this finding, examination of HDAC6 distribution in articular chondrocytes revealed that while the majority of HDAC6 staining is cytoplasmic, HDAC6 is also found within the ciliary axoneme [Fig. 4(B)]. HDAC6 staining within the cilium is punctate and occurs along the entire length of the axoneme [Fig. 4(B), insert].

Fig. 4.

HDAC6 modulates strain-induced cilia disassembly and hedgehog signalling. (A) Primary cilia length for bovine articular chondrocytes subjected to 20% CTS for 1 h in the presence of TSA (7 nM), Tubacin (500 nM) or the carrier DMSO (control). Data represents mean ± CI (n = 15). Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrected t-tests. (B) Representative confocal maximum intensity Z projection showing HDAC6 (green) localised to the primary cilium immunofluorescently labelled for acetylated α-tubulin (red). Nucleus counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20 μm, lower panel shows magnified view of the cilium. Ptch1 (C) and (D) Gli1 gene expression for primary articular chondrocytes subjected to 20% CTS for 1 h in the presence of Tubacin (500 nM) or the carrier DMSO (control). Data represents mean ± CI (n = 6). Data is expressed as a fold change relative to the mean of the untreated or unstrained control group. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrected t-tests.

The data presented so far indicates that HDAC6 inhibition rescues the cilia disassembly observed in response to 20% CTS. If the absence of hedgehog pathway activation at this strain magnitude is due to HDAC6-dependent axoneme destabilisation and cilia disassembly then inhibiting tubulin deacetylation would be expected to rescue mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling. Consistent with this hypothesis, tubacin treatment restored mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling such that the expression of Ptch1 was increased following 1 h 20% CTS relative to the noCTS control [P < 0.001; Fig. 4(C)]. By contrast, the expression of Gli1 was not increased by mechanical strain [P = 0.956; Fig. 4(D)].

Cilia disassembly inhibits mechanosensitive ADAMTS-5 expression

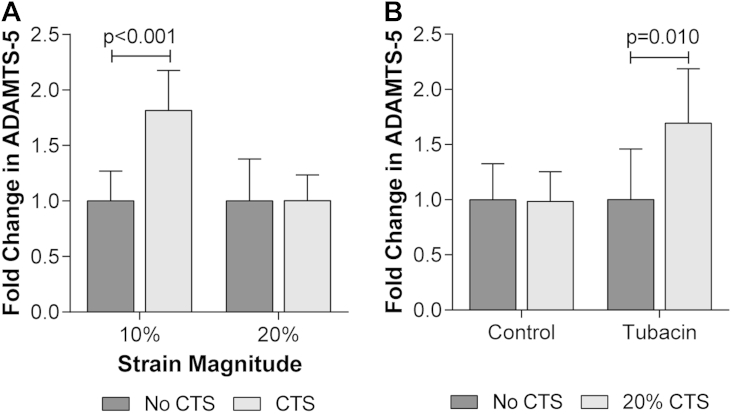

Despite reports that Ihh functions as a mechanotransduction mediator to promote chondrocyte proliferation during embryonic development26,35; cell-cycle status was not altered by strain in articular chondrocytes suggesting proliferation is not increased in these cells [Fig. 3(D)]. Previous studies have reported that hedgehog signalling promotes ADAMTS-5 expression in human articular chondrocytes21, therefore changes in ADAMTS-5 expression were examined in response to 10% and 20% CTS. Consistent with hedgehog pathway activation, the expression of ADAMTS-5 was increased following 10% CTS [P < 0.001; Fig. 5(A)]. ADAMTS-5 expression was not upregulated in response to 20% CTS [P > 0.999; Fig. 5(A)] consistent with the lack of hedgehog pathway activation at this strain magnitude. Finally, mechanosensitive ADAMTS-5 expression at 20% strain was restored when cells were subjected to strain in the presence of tubacin [P = 0.010; Fig. 5(B)]. Thus inhibiting cilia disassembly rescued both mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling and ADAMTS-5 expression in bovine chondrocytes which were lost at 20% strain.

Fig. 5.

Primary cilia disassembly regulates mechanosensitive ADAMTS-5 expression. Changes in ADAMTS-5 expression for (A) bovine articular chondrocytes subjected to 10% or 20% CTS or unstrained control period for 1 h and (B) bovine articular chondrocytes subjected to 20% CTS for 1 h in the presence of Tubacin (500 nM) or the carrier DMSO (control). Data is expressed as a fold change relative to the mean of the untreated or unstrained control group. Data represents mean ± CI (n = 6–8). Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrected t-tests.

Discussion

In this study, primary articular chondrocytes were subjected to variable levels of mechanical strain in 2D culture. For the first time we demonstrate that hedgehog signalling is mechanosensitive in adult chondrocytes and that pathway activation requires the primary cilium. Moreover we show that the chondrocyte primary cilium disassembles in response to CTS in a strain dependent manner. Cilium disassembly in chondrocytes requires HDAC6-dependent tubulin deacetylation and functions to inhibit mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling and ADAMTS-5 expression.

Chondrocytes experience a variety of mechanical or physicochemical stimuli during physiological joint loading such as compressive, tensile and shear strain, fluid flow, electrical streaming potentials and changes in pH and osmolarity (for review see36). While tensile strain may only be a small component of this physiological load the effects of tensile strain on chondrocyte function have been widely studied in 2D culture37–39. In the context of the current study, this model is advantageous as it provides a sensitive and highly reproducible system in which to reliably measure small changes in cilia length.

Mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling has previously been reported in immature chondrocytes26,35 but this study is the first to demonstrate the response in adult chondrocytes. This has important consequences for understanding the aberrant activation of hedgehog signalling in OA which promotes cartilage degeneration through the upregulation of ADAMTS-521. In agreement with our findings, Shao et al. recently used chemical disruption of the ciliary structure to demonstrate a requirement for the cilium in mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling in growth plate chondrocytes35. In contrast with the current study, Ihh expression was shown to be down-regulated by cilia disruption perhaps highlighting a key difference between mature and immature cells. Indeed, during skeletal development hedgehog signalling promotes chondrocyte hypertrophy and thus further Ihh expression23,40 however the function of hedgehog signalling for healthy articular cartilage is unclear.

The present study demonstrates that mechanical loading reduces primary cilia length in a strain dependent manner. In articular cartilage, the mean length of chondrocyte primary cilia in the superficial zone is 1.1 μm. This is approximately 27% shorter than reported for deep zone chondrocytes for which mean cilia length is 1.5 μm9. Our data suggests that zonal variations in a chondrocytes mechanical environment might be directly responsible for these differences as several studies have reported that the cells of the superficial zone are subjected to the greatest levels of both compressive and tensile strain41. The extent of cilium disassembly observed in the current study is less dramatic than the 30% reduction in length observed following prolonged dynamic compression of chondrocytes in agarose7. This suggests that different types of stimuli, or differences in the intensity and duration of the loading regime might regulate cilia structure to different extents. Indeed, a similarly low level of cilia disassembly was observed for chondrocytes in situ during short-term osmotic loading where cilia length was reduced by just 10%42.

The influence mechanosensitive disassembly exerts over the function of the cilium as a flow sensor is well studied15,43,44. However, while cilium disassembly is hypothesised to modulate other signalling pathways this has not been demonstrated in chondrocytes prior to this study. For the first time we show that loading-induced chondrocyte cilia disassembly influences mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling and ADAMTS-5 expression at high strains. Remarkably, the 15% reduction in cilia length observed at 20% strain was sufficient to completely inhibit mechanosensitive hedgehog pathway activation and ADAMTS-5 expression. These data indicate that hedgehog signalling is highly sensitive to changes in primary cilia length. In osteoarthritic cartilage there is a 50% increase in the number of ciliated cells and an increase of approximately 20% in mean primary cilia length9. Our data suggests that this modest increase will be more than sufficient to influence cilia-mediated hedgehog signalling and may therefore explain the aberrant upregulation of this pathway reported in OA21.

In the present study the inhibition of HDAC6 prevented strain-induced cilia disassembly and at least partially restored mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling (Fig. 4) and ADAMTS-5 expression at 20% strain [Fig. 5(B)]. It is unclear how tubulin deacetylation is influencing this pathway. However the findings agree with previous studies which show that HDAC6 is required for cilia disassembly in response to heat shock and that this inhibits hedgehog signalling34. While destabilisation of the axoneme might be influencing IFT and the traffic of Gli proteins through the cilium, previous studies have also linked ciliary dysfunction to changes in whole cell HDAC6 activity and tubulin acetylation levels45. While, gross changes in the level of whole cell tubulin acetylation were not observed in this study (not shown), subtle changes in the acetylation status of cytoplasmic microtubules could potentially affect cellular function by modulating kinesin motor activity and thus microtubule transport throughout the cell46. Alternatively, the actin regulatory protein cortactin is reportedly a substrate of HDAC6 and the increased activity of this enzyme could affect ciliary structure through changes in actin dynamics47. Gradilone et al. have recently reported that increased HDAC6 expression in cholangiocarcinoma disrupts hedgehog signalling and promotes tumour growth through the modulation of cilia structure18. HDAC6 inhibition was able to restore cilia function and rescue the signalling defect such that a reduction in tumour growth was observed. This and the current study highlight HDAC6 as a potentially targetable element which could be used to adjust cilia structure–function in vivo.

In summary, we have shown that mechanically induced cilia disassembly occurs in an HDAC6 dependent manner in healthy articular chondrocytes and attenuates mechanosensitive hedgehog signalling and ADAMTS-5 expression at higher strains. We propose that low levels of mechanical loading may activate hedgehog-mediated matrix degradation, but that cilia disassembly at higher strains provides a chondroprotective mechanism such that hedgehog signalling is prevented. The study highlights the sensitive relationship between primary cilia length and hedgehog signalling. Thus the aberrant upregulation of hedgehog signalling reported in OA21 may be directly related to an increase in cilia length9. Consequently this study provides further evidence of the importance of primary cilia structure in cartilage development, health and disease.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the drafting of this article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published.

Study conception and design: Thompson, Knight, Chapple.

Acquisition of data: Thompson.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Thompson, Knight, Chapple.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Role of the funding source

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) [grant number BB/E009824/1 to JPC]; CT was funded by a BBSRC studentship [grant number BB/F016913/1].

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr AKT Wann for helpful suggestions and discussion throughout the course of this study and for editing of the manuscript and Courtney Haycraft and Sue McGlashan for the establishment of the ORPK cell model. We are grateful to Humphreys and Sons for supplying the bovine forefeet.

Contributor Information

C.L. Thompson, Email: clare.l.thompson@qmul.ac.uk.

J.P. Chapple, Email: j.p.chapple@qmul.ac.uk.

M.M. Knight, Email: m.m.knight@qmul.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary Fig. S1.

GAPDH expression is not significantly altered by mechanical strain. Changes in GAPDH expression for (A) primary bovine articular chondrocytes and (B) WT and ORPK chondrocytes subjected to 10% or 20% CTS or unstrained control period for 1 h. Data represents mean ± CI (n = 8–10). Data is expressed as a fold change relative to the mean of the unstrained control group. Statistical significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni corrected tests.

References

- 1.Wheatley D.N., Wang A.M., Strugnell G.E. Expression of primary cilia in mammalian cells. Cell Biol Int. 1996;20:73–81. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross A.J., May-Simera H., Eichers E.R., Kai M., Hill J., Jagger D.J. Disruption of Bardet–Biedl syndrome ciliary proteins perturbs planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1135–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider L., Clement C.A., Teilmann S.C., Pazour G.J., Hoffmann E.K., Satir P. PDGFR alpha alpha signaling is regulated through the primary cilium in fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1861–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbit K.C., Aanstad P., Singla V., Norman A.R., Stainier D.Y., Reiter J.F. Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature. 2005;437:1018–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huangfu D., Liu A., Rakeman A.S., Murcia N.S., Niswander L., Anderson K.V. Hedgehog signalling in the mouse requires intraflagellar transport proteins. Nature. 2003;426:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature02061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohatgi R., Milenkovic L., Scott M.P. Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1139740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGlashan S.R., Knight M.M., Chowdhury T.T., Joshi P., Jensen C.G., Kennedy S. Mechanical loading modulates chondrocyte primary cilia incidence and length. Cell Biol Int. 2010;34:441–446. doi: 10.1042/CBI20090094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wann A.K., Knight M.M. Primary cilia elongation in response to interleukin-1 mediates the inflammatory response. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2967–2977. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0980-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGlashan S.R., Cluett E.C., Jensen C.G., Poole C.A. Primary cilia in osteoarthritic chondrocytes: from chondrons to clusters. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2013–2020. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wann A.K., Zuo N., Haycraft C.J., Jensen C.G., Poole C.A., McGlashan S.R. Primary cilia mediate mechanotransduction through control of ATP-induced Ca2+ signaling in compressed chondrocytes. FASEB J. 2012;26:1663–1671. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-193649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phan M.N., Leddy H.A., Votta B.J., Kumar S., Levy D.S., Lipshutz D.B. Functional characterization of TRPV4 as an osmotically sensitive ion channel in porcine articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3028–3037. doi: 10.1002/art.24799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang C.F., Ramaswamy G., Serra R. Depletion of primary cilia in articular chondrocytes results in reduced Gli3 repressor to activator ratio, increased Hedgehog signaling, and symptoms of early osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin H., Diener D.R., Geimer S., Cole D.G., Rosenbaum J.L. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) cargo: IFT transports flagellar precursors to the tip and turnover products to the cell body. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:255–266. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waters A.M., Beales P.L. Ciliopathies: an expanding disease spectrum. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1039–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1731-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besschetnova T.Y., Kolpakova-Hart E., Guan Y., Zhou J., Olsen B.R., Shah J.V. Identification of signaling pathways regulating primary cilium length and flow-mediated adaptation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caspary T., Larkins C.E., Anderson K.V. The graded response to sonic hedgehog depends on cilia architecture. Dev Cell. 2007;12:767–778. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran P.V., Haycraft C.J., Besschetnova T.Y., Turbe-Doan A., Stottmann R.W., Herron B.J. THM1 negatively modulates mouse sonic hedgehog signal transduction and affects retrograde intraflagellar transport in cilia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:403–410. doi: 10.1038/ng.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gradilone S.A., Radtke B.N., Bogert P.S., Huang B.Q., Gajdos G.B., Larusso N.F. HDAC6 inhibition restores ciliary expression and decreases tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2259–2270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verghese E., Weidenfeld R., Bertram J.F., Ricardo S.D., Deane J.A. Renal cilia display length alterations following tubular injury and are present early in epithelial repair. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:834–841. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan K.E., Chiang C. Hedgehog secretion and signal transduction in vertebrates. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17905–17913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.356006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin A.C., Seeto B.L., Bartoszko J.M., Khoury M.A., Whetstone H., Ho L. Modulating hedgehog signaling can attenuate the severity of osteoarthritis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1421–1425. doi: 10.1038/nm.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei F., Zhou J., Wei X., Zhang J., Fleming B.C., Terek R. Activation of Indian hedgehog promotes chondrocyte hypertrophy and upregulation of MMP-13 in human osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.St-Jacques B., Hammerschmidt M., McMahon A.P. Indian hedgehog signaling regulates proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and is essential for bone formation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2072–2086. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tchetina E.V., Squires G., Poole A.R. Increased type II collagen degradation and very early focal cartilage degeneration is associated with upregulation of chondrocyte differentiation related genes in early human articular cartilage lesions. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:876–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nowlan N.C., Prendergast P.J., Murphy P. Identification of mechanosensitive genes during embryonic bone formation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Q., Zhang Y., Chen Q. Indian hedgehog is an essential component of mechanotransduction complex to stimulate chondrocyte proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35290–35296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chowdhury T.T., Bader D.L., Lee D.A. Dynamic compression inhibits the synthesis of nitric oxide and PGE(2) by IL-1beta-stimulated chondrocytes cultured in agarose constructs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:1168–1174. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larionov A., Krause A., Miller W. A standard curve based method for relative real time PCR data processing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee D.A., Brand J., Salter D., Akanji O.O., Chowdhury T.T. Quantification of mRNA using real-time PCR and Western blot analysis of MAPK events in chondrocyte/agarose constructs. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;695:77–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-984-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iomini C., Tejada K., Mo W., Vaananen H., Piperno G. Primary cilia of human endothelial cells disassemble under laminar shear stress. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:811–817. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardner K., Arnoczky S.P., Lavagnino M. Effect of in vitro stress-deprivation and cyclic loading on the length of tendon cell cilia in situ. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:582–587. doi: 10.1002/jor.21271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugacheva E.N., Jablonski S.A., Hartman T.R., Henske E.P., Golemis E.A. HEF1-dependent Aurora a activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell. 2007;129:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haggarty S.J., Koeller K.M., Wong J.C., Grozinger C.M., Schreiber S.L. Domain-selective small-molecule inhibitor of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6)-mediated tubulin deacetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:4389–4394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0430973100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prodromou N.V., Thompson C., Osborn D.P., Cogger K.F., Ashworth R., Knight M.M. Heat shock induces rapid resorption of primary cilia. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4297–4305. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao Y.Y., Wang L., Welter J.F., Ballock R.T. Primary cilia modulate Ihh signal transduction in response to hydrostatic loading of growth plate chondrocytes. Bone. 2011;50(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urban J.P. The chondrocyte: a cell under pressure. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:901–908. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Millward-Sadler S.J., Wright M.O., Lee H., Caldwell H., Nuki G., Salter D.M. Altered electrophysiological responses to mechanical stimulation and abnormal signalling through alpha5beta1 integrin in chondrocytes from osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:272–278. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang J., Ballou L.R., Hasty K.A. Cyclic equibiaxial tensile strain induces both anabolic and catabolic responses in articular chondrocytes. Gene. 2007;404:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saito T., Nishida K., Furumatsu T., Yoshida A., Ozawa M., Ozaki T. Histone deacetylase inhibitors suppress mechanical stress-induced expression of RUNX-2 and ADAMTS-5 through the inhibition of the MAPK signaling pathway in cultured human chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vortkamp A., Lee K., Lanske B., Segre G.V., Kronenberg H.M., Tabin C.J. Regulation of rate of cartilage differentiation by Indian hedgehog and PTH-related protein. Science. 1996;273:613–622. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guilak F., Ratcliffe A., Mow V.C. Chondrocyte deformation and local tissue strain in articular cartilage: a confocal microscopy study. J Orthop Res. 1995;13:410–421. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rich D.R., Clark A.L. Chondrocyte primary cilia shorten in response to osmotic challenge and are sites for endocytosis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:923–930. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwartz E.A., Leonard M.L., Bizios R., Bowser S.S. Analysis and modeling of the primary cilium bending response to fluid shear. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F132–F138. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.1.F132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Resnick A., Hopfer U. Force-response considerations in ciliary mechanosensation. Biophys J. 2007;93:1380–1390. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berbari N.F., Sharma N., Malarkey E.B., Pieczynski J.N., Boddu R., Gaertig J. Microtubule modifications and stability are altered by cilia perturbation and in cystic kidney disease. Cytoskeleton. 2013;70:24–31. doi: 10.1002/cm.21088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammond J.W., Huang C.F., Kaech S., Jacobson C., Banker G., Verhey K.J. Posttranslational modifications of tubulin and the polarized transport of kinesin-1 in neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:572–583. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma N., Kosan Z.A., Stallworth J.E., Berbari N.F., Yoder B.K. Soluble levels of cytosolic tubulin regulate ciliary length control. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:806–816. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]