Summary

S1PR1 signaling has been shown to restrain the number and function of Tregs in the periphery under physiological conditions and in colitis models, but its role in regulating tumor-associated T cells is unknown. Here, we show that S1PR1 signaling in T cells drives Treg accumulation in tumors, limits CD8+ T cell recruitment and activation, and promotes tumor growth. S1PR1 intrinsic in T cells affects Tregs, but not CD8+ T cells, as demonstrated by adoptive transfer models and transient pharmacological S1PR1 modulation. We further investigated the molecular mechanism(s) underlying S1PR1-mediated Treg accumulation in tumors, showing that increasing S1PR1 in CD4+ T cells promotes STAT3 activation and JAK/STAT3-dependent Treg tumor migration. Furthermore functionally ablating STAT3 in T cells diminishes tumor-associated Treg accumulation and tumor growth. Our study demonstrates a stark contrast of the consequences by the same signaling receptor, namely S1PR1, in regulating Tregs in the periphery and in tumors.

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are critical mediators in shaping the immunological microenvironment in various diseases, including cancer (Chaudhry and Rudensky, 2013; Mougiakakos et al., 2010; Zou, 2006). In tumors, Tregs accumulate and suppress anti-tumor immunity by expressing anti-inflammatory cytokines and co-inhibitory molecules that modulate tumor cells and other tumor-associated immune subsets (Darrasse-Jeze et al., 2009; Josefowicz et al., 2012; Menetrier-Caux et al., 2012; Yamaguchi and Sakaguchi, 2006). Although numerous studies have implicated Tregs in promoting cancer progression through multiple mechanisms (Menetrier-Caux et al., 2012; Nishikawa and Sakaguchi, 2010), the signaling mediators that regulate their accumulation and function in tumors have yet to be fully explored. Recently, several chemokine signaling axes have been shown to mediate Treg recruitment to tumors (Mailloux and Young, 2010; Nishikawa and Sakaguchi, 2010). In addition to Gprotein coupled receptor (GPCR) chemokine receptors, sphingosine-1 phosphate receptors (S1PR1-5) are also important regulators of immune cells, including T cells (Arnon et al., 2011; Rivera et al., 2008; Spiegel and Milstien, 2011), but their impact on tumor-associated T cells remains to be directly investigated.

The roles of S1PR1 in migration and activation of specific T cell subsets has been somewhat controversial. Early studies implicated S1P and S1PR1 in regulating the differentiation of Th2, Treg, and Th17 cells, while limiting Th1 cells (Goetzl et al., 2008). More recent studies have demonstrated that S1PR1 restrains thymic development of Tregs, their peripheral numbers and their suppressive functions (Liu et al., 2009). In mice with S1pr1 ablation in T cells, Treg populations in lymphoid tissues are enhanced with elevated suppressive activity (Liu et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010). Conversely, in mice with T cells over-expressing S1pr1, Tregs are blunted in lymphoid tissues and in the colon, while Th1 subsets are increased, making them particularly susceptible to colitis in adoptive transfer models (Liu et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010). S1P and S1PR1 are also important mediators of cancer progression (Spiegel and Milstien, 2011). However, whether S1PR1 promotes or inhibits tumor Tregs remains to be addressed. In the current study using mice with S1pr1 over-expression or deletion specifically in T cells as well as transient pharmacological S1PR1 modulation, we show that S1PR1 signaling regulates the accumulation of Tregs in tumors, limits CD8+ T cell infiltration and function, and promotes tumor growth. Furthermore, we find that S1PR1-mediated tumor accumulation of Tregs requires JAK/STAT3 signaling. These findings suggest that modulation of S1PR1-JAK/STAT3 signaling in Tregs may have significant effects on the tumor microenvironment with potential immunotherapeutic implications in cancer.

Results and Discussion

T cell S1PR1 signaling promotes tumor accumulation of Tregs

To investigate whether S1PR1 regulates Treg accumulation in tumors, E0771 breast carcinoma cells were orthotopically implanted in WT (S1pr1+/+) and T cell S1pr1-deficient (S1pr1−/−) mice, and Tregs were assessed in primary tumors, spleens and tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLN). Genetic ablation of S1pr1 in T cells promoted Treg development in lymphoid tissues, with a significant increase in Foxp3+ Tregs found within the CD4+ T cell compartment in spleens and TDLN of tumor-bearing mice (Figure 1A), corroborating previous findings under non-tumor bearing conditions (Liu et al., 2009). Interestingly, Tregs were dramatically reduced in tumors by S1pr1 ablation in T cells (Figure 1A). Blockade of tumor accumulation of Tregs in S1pr1−/− mice was also confirmed in the B16 melanoma model (Supplemental Figure 1A).

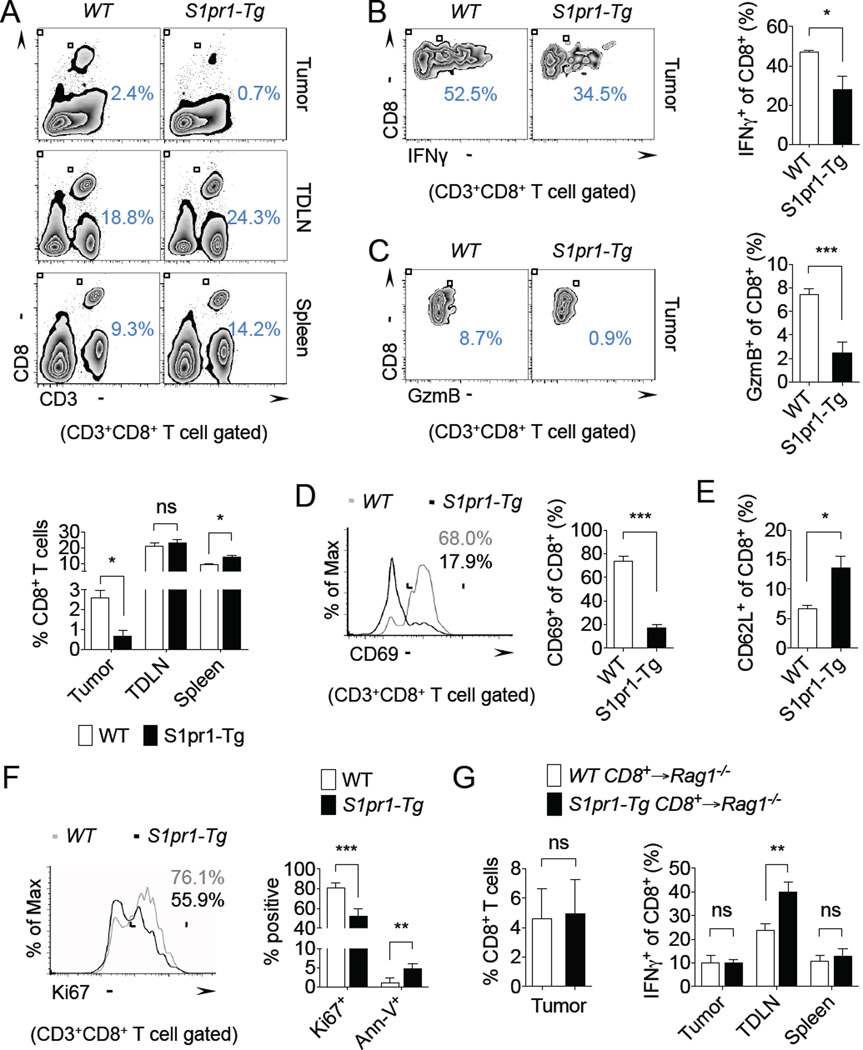

Figure 1. T cell S1PR1 signaling promotes tumor accumulation of Tregs.

(A) Foxp3+ of CD4+ T cells in the tumor, TDLN, and spleen of E0771 tumor-bearing S1pr1+/+ and S1pr1−/− mice. Representative flow cytometry images (top) and quantification of n = 4 per group (bottom). (B) Foxp3+ of CD4+ T cells in the tumor, tumor-draining lymph node (TDLN), and spleen of E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. Representative flow cytometry (top) and quantification of n = 3 per group (bottom). (C) Foxp3+ of CD4+ T cells in E0771 tumor-bearing mice treated for 24 hrs with either vehicle control (2.5% DMSO in PBS) or 50 µg FTY720. Representative flow cytometry images (top) and quantification of n ≥ 3 per group (bottom). PB = peripheral blood. (D) Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ and Foxp3+CD4+ T cells in MB49 tumor-bearing Rag2−/− mice reconstituted with WT (CD45.1) and S1pr1-Tg (CD45.2) splenic T cells. Quantification of n = 2 per group. (E) CD4+ T cells (left) and Foxp3+ of CD4+ T cells in the tumor, TDLN, and spleen (right) in B16 tumor-bearing Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with WT or S1pr1-Tg CD4+ T cells. n = 6 per group. (F) Ki67 and Annexin-V (Ann-V) expression in tumorassociated Tregs of B16 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. Representative flow cytometry images of Ki67 (top) and quantification of n ≥ 4 per group (bottom). All data shown above are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Although the use of T cell-S1pr1 deficient mice demonstrated a requirement for S1PR1 in Treg accumulation in tumors, S1PR1 is known to be crucial for thymic egress of T cells and therefore its genetic ablation leads to systemic lymphopenia (Matloubian et al., 2004). Thus, we employed T cell S1pr1-transgenic mice (S1pr1-Tg) (Graler et al., 2005) to confirm our findings in tumor models. Overexpression of S1pr1 in T cells promoted Treg accumulation in E0771 and B16 tumors (Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure 1B). Of note, total CD4+ T cell percentages in tumors remained unchanged (WT: 3.1% ± 0.3%, S1pr1-Tg: 3.4% ± 0.6%). CD25 was widely expressed by tumor-associated Tregs from WT and S1pr1-Tg mice (Supplemental Figure 1C). Although prior studies demonstrated diminished Treg numbers in lymphoid tissue of S1pr1-Tg mice, pro-cancer systemic effects in E0771 and B16 tumor-bearing mice may have counteracted the diminishing Tregs in lymphoid organs, as we observed little effect on Tregs in TDLN and a slight increase in splenic Tregs in S1pr1-Tg mice compared with control mice (Figure 1B and Supplemental Figure 1B). Taken together, our findings are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that S1PR1 restrains Treg numbers in the periphery (Liu et al., 2009). However, within the primary tumor, S1PR1 signaling is critical for Treg accumulation, which highlights a stark contrasting role of S1PR1 in regulating peripheral and tumor-associated Tregs.

To further substantiate the regulation of tumor accumulation of Tregs by S1PR1, we used a pharmacologic approach with the S1PR1 immunomodulator, FTY720 (Mandala et al., 2002). Mice bearing established E0771 tumors were treated systemically with vehicle control or FTY720 for 24 hours prior to evaluating Tregs in various tissues. There was an expected reduction of total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood of FTY720-treated mice compared with control mice (Supplemental Figure 2A–B). However, total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells percentages in tumors, spleens, and TDLN remained unchanged (Supplemental Figure 2A–B). We showed a significant reduction in tumor accumulation of Tregs, with an increased trend of Tregs in peripheral blood following transient FTY720 treatment (Figure 1C), suggesting a block in blood-to-tumor Treg recruitment. This short-term treatment strategy could have important therapeutic implications, where transient modulation of S1PR1 may prime the tumor microenvironment by inhibiting Tregs to allow for more potent anti-tumor immunity in combination with other treatment approaches, such as adoptive T cell immunotherapy (Chen et al., 2007; Zou, 2006).

We next evaluated the importance of S1PR1 in the tumor accumulation of T cells by co-adoptively transferring WT (CD45.1) and S1pr1-Tg (CD45.2) splenic T cells into Rag1−/− mice, generating “chimeric” mice, which were then challenged with B16 melanoma tumors. Over-expression of S1pr1 in T cells significantly promoted tumor accumulation of Tregs, while showing a minimal effect on CD8+ T cells in tumors (Figure 1D). To address the specific impact of S1PR1 signaling on the recruitment of CD4+ T cells to tumors, WT or S1pr1-Tg CD4+ T cells were transferred into Rag1−/− mice. Although total CD4+ T cells in tumors were similar in both groups, tumor accumulation of Tregs was increased in S1pr1-Tg chimeras compared with WT chimera mice (Figure 1E). The adoptive transfer model further confirmed that systemic cancer effects may override the S1PR1-mediated restrain on Tregs in peripheral tissues, as Treg populations were relatively unaffected in spleens and TDLN by overexpression of S1pr1. To determine whether increased Tregs in tumors was due to local expansion or recruitment, we assessed proliferation and apoptosis markers in tumor-associated Tregs by flow cytometry. We found that there were no discernible differences in Ki67 or Annexin-V expression in Tregs from WT and S1pr1-Tg mice (Figure 1F), suggesting that recruitment rather than local expansion of Tregs is crucially regulated by S1PR1 signaling.

S1PR1 inhibits CD8+ T cell accumulation and activity in tumors

We next assessed whether increased accumulation of Tregs in tumors by S1PR1 signaling impacts anti-tumor immunity. Although in the co-adoptive transfer system we observed no impact of S1PR1 in CD8+ T cells in tumors, we demonstrated a significant reduction in CD8+ T cells in E0771 tumors of S1pr1-Tg mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2A), which was associated with increased tumor-associated Tregs. We observed similar findings in the B16 tumor model (Supplemental Figure 3A). Importantly, TDLN showed no differences in CD8+ T cells, although spleens showed a modest but significant increase in S1pr1-Tg mice compared with WT control mice (Figure 2A).

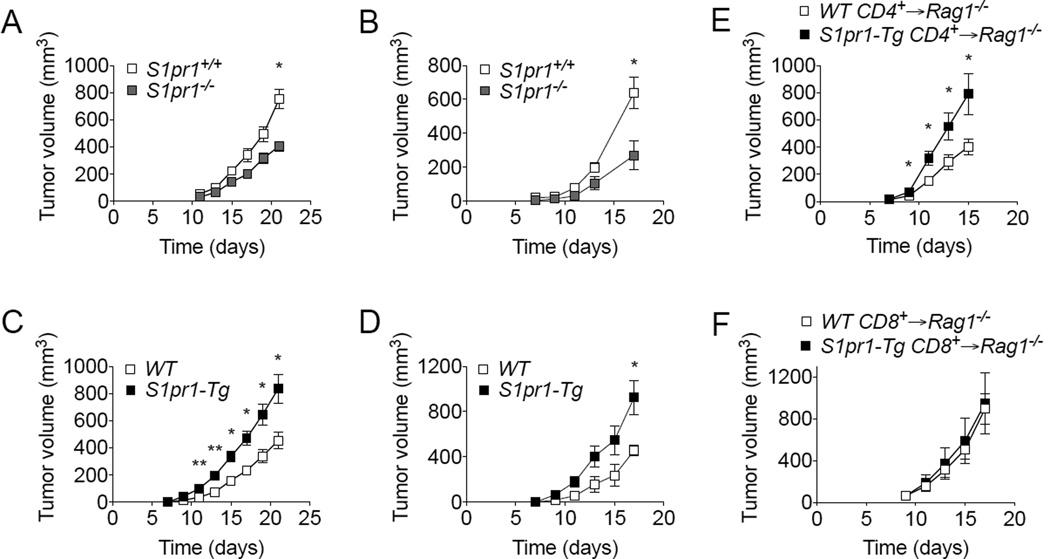

Figure 2. S1PR1 inhibits CD8+ T cell accumulation and activity in tumors.

(A) CD3+ CD8+ T cells in the tumor, TDLN, and spleen of E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. Representative flow cytometry images (top) and quantification of n = 4 per group (bottom). (B) IFNγ+ tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. Representative flow cytometry images (left) and quantification of n = 3 per group (right). (C) Granzyme B+ tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. Representative flow cytometry images (left) and quantification of n = 4 per group (right). (D) CD69+ tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. Representative flow cytometry images (left) and quantification of n = 4 per group (right). (E) CD62L+ tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. n ≥ 4 per group. (F) Ki67 and Annexin-V (Ann-V) expression in tumor-associated CD8+ T cells of B16 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. Representative flow cytometry images of Ki67 (left) and quantification of n ≥ 4 per group (right). (G) Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (left) and IFNγ+ CD8+ T cells in the tumor, TDLN, and spleen (right) of B16 tumor-bearing Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with WT or S1pr1-Tg CD8+ T cells. n = 6 per group. All data shown above are representative of at least two independent experiments.

To assess the activation status of tumor-associated CD8+ T cells, we analyzed their intracellular levels of IFNγ by flow cytometry. IFNγ+CD8+ T cells were reduced in E0771 and B16 tumors from mice with T cell over-expression of S1pr1 compared with control mice (Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure 3B). We also observed similar reductions in IFNγ production in TDLN-associated CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Figure 3C), in contrast to earlier findings in naïve non-tumor bearing mice (Liu et al., 2010). RT-PCR analysis of FACS-sorted tumor-associated CD8+ T cells confirmed their reduced IFNγ expression (Supplemental Figure 3D). Granzyme B expression in CD8+ T cells, as a measure of their cytotoxic function, demonstrated a significant reduction in S1pr1-Tg mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2C). We also observed a dramatic reduction in the activation marker, CD69, in tumor associated CD8+ T cells from S1pr1-Tg mice (Figure 2D). Correlating with their reduced activation state, CD8+ T cells from S1pr1-Tg mice showed increased CD62L expression (Figure 2E), a naïve T cell marker. Although prior studies suggested that S1PR1 expression promotes IFNγ production in CD8+ T cells (Liu et al., 2010), we showed that in tumor models, S1PR1 negatively regulated IFNγ production. Additionally, we found decreased proliferation and increased apoptosis of tumorassociated CD8+ T cells in S1pr1-Tg mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2F), suggesting local tumor inhibition.

To determine whether S1PR1 intrinsic to CD8+ T cells controls their recruitment and activity in tumors, we adoptively transferred splenic CD8+ T cells from WT and S1pr1-Tg mice into Rag1−/− mice. Tumor infiltration of CD8+ T cells was unaffected by S1pr1 over-expression (Figure 2G). In addition, IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells in tumors and spleens were also unaffected, although we noted increased IFNγ production by CD8+ T cells in TDLN (Figure 2G). Collectively, we have demonstrated that although S1PR1 signaling had a dramatic impact on the tumor infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells, this effect was not intrinsically regulated by S1PR1 signaling in CD8+ T cells but likely mediated through S1PR1-induced Treg accumulation in tumors. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the critical chemokine signaling mediators that are requirement for direct CD8+ T cell recruitment to tumors.

S1PR1 in Tregs promotes tumor growth

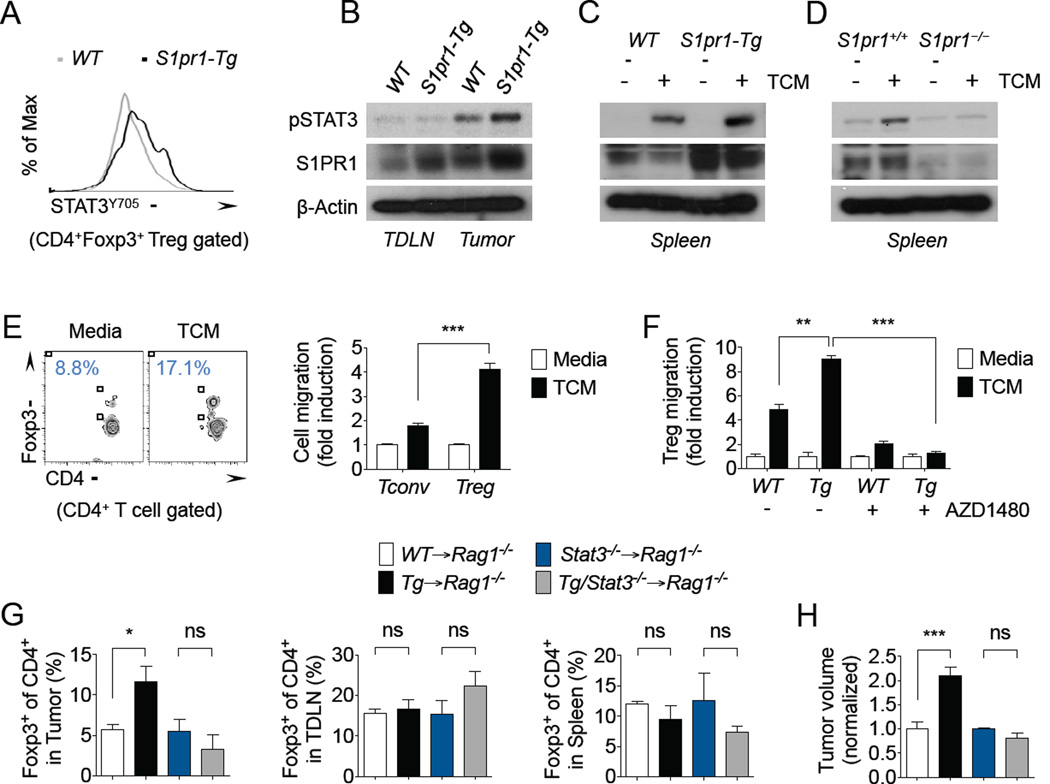

The ability of S1PR1 to promote tumor accumulation of Tregs and inhibit CD8+ T cells prompted us to assess how S1PR1 signaling in T cells ultimately affects tumor growth. We observed significant tumor growth inhibition in S1pr1−/− mice compared with S1pr1+/+ mice bearing E0771 tumors (Figure 3A) or B16 tumors (Figure 3B). Likewise, S1pr1-Tg mice showed significantly increased tumor growth kinetics compared with WT control mice (Figure 3C–D). To distinguish the potential contribution of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to tumor development, we measured tumor growth in Rag1−/− mice adoptively transferred with WT or S1pr1 over-expressing CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Rag1−/− mice adoptively transferred with S1pr1-Tg CD4+ T cells showed significantly increased tumor growth compared with WT CD4+ T cell-transferred mice (Figure 3E), while we observed no differences in tumor growth kinetics in Rag1−/− mice adoptively transferred with S1pr1-Tg CD8+ T cells (Figure 3F), suggesting that the overall impact of S1pr1 expression in T cells on tumor growth is primarily contributed by Tregs.

Figure 3. S1PR1 in Tregs promotes tumor growth.

Tumor growth kinetics of E0771 (A) and B16 (B) tumor-bearing S1pr1+/+ and S1pr1−/− mice. n = 3 per group. Tumor growth kinetics of E0771 (C) and B16 (D) tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. n ≥ 4 per group. (E) B16 tumor growth in Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with WT or S1pr1-Tg CD4+ T cells. n = 6 per group. (F) B16 tumor growth in Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with WT or S1pr1-Tg CD8+ T cells. n = 6 per group. All data shown above are representative of at least two independent experiments.

S1PR1-mediated tumor accumulation of Tregs requires JAK/STAT3 signaling

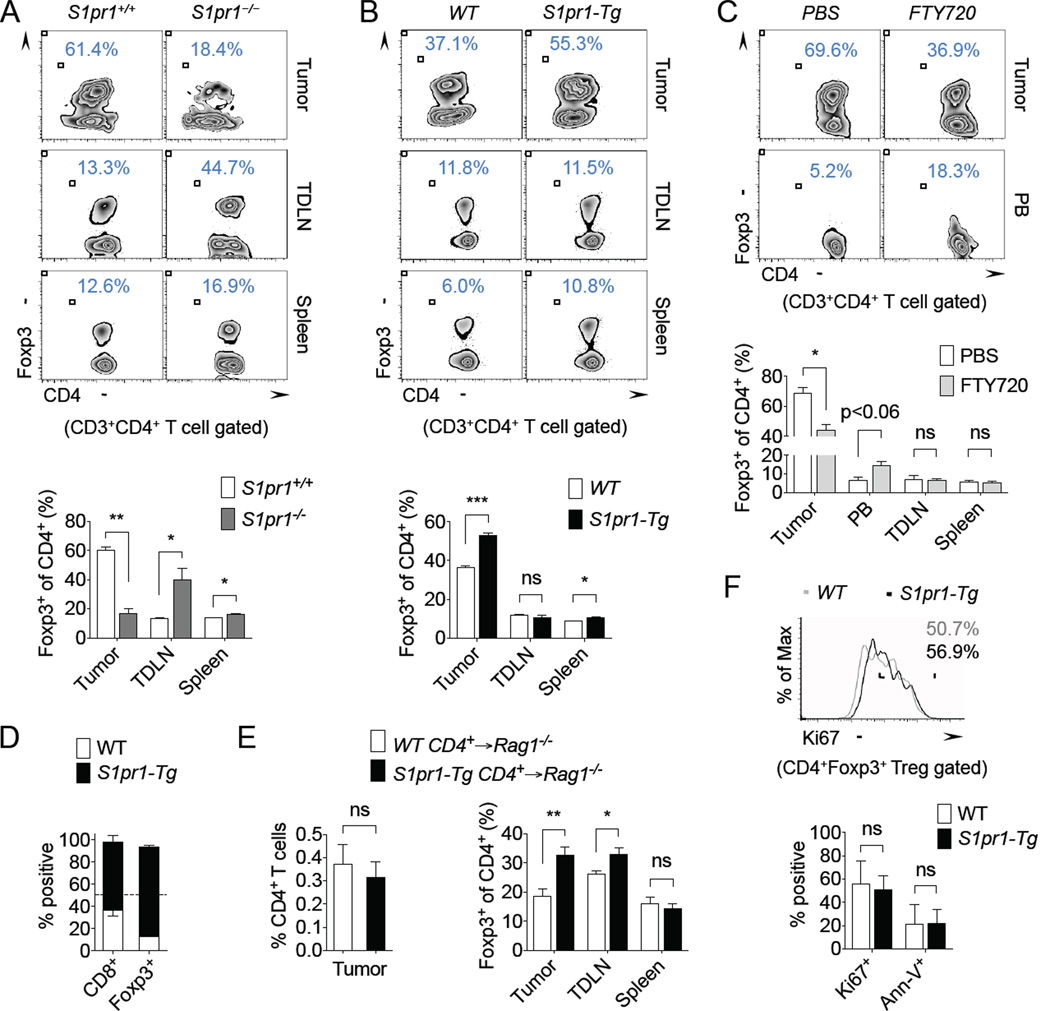

Multiple studies have also implicated STAT3 activation in driving tumor-associated Tregs, by regulating their numbers and suppressive activities in tumors (Fujita et al., 2008; Kortylewski et al., 2009; Kujawski et al., 2010; Pallandre et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2009). To determine whether STAT3 signaling may be involved in S1PR1-mediated Treg accumulation in tumors, we first assessed phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3, STAT3Y705) levels in T cells of tumor-bearing mice. Tumor-infiltrating Tregs showed moderately higher pSTAT3 levels in S1pr1-Tg mice (MFI: 2870) compared with WT mice (MFI: 2470) by flow cytometry (Figure 4A). Western blotting further demonstrated elevated STAT3 activation in tumor-associated CD4+ T cells in S1pr1-Tg mice compared with WT mice (Figure 4B). S1pr1 expression was also assessed by RT-PCR in tumor-associated WT and S1pr1-Tg Tregs from these mice (Supplemental Figure 3E–F). Our previous studies demonstrated persistent STAT3 activation by S1PR1 in tumor cells and in tumor-associated myeloid cells (Deng et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2010). To mimic this phenomenon in vitro, we stimulated T cells with tumor-derived factors derived ex vivo from B16 tumors grown in C57BL/6 mice. B16 tumor-conditioned media (TCM) induced STAT3 activation in CD4+ T cells, which was prolonged by S1pr1 over-expression (Figure 4C). Conversely, TCM failed to induce STAT3 activation in S1pr1−/− CD4+ T cells compared with controls (Figure 4D). Overall, these findings support a link between S1PR1 and STAT3 in T cells, and that STAT3 activation in tumor-associated Tregs is potently regulated by S1PR1 signaling.

Figure 4. S1PR1-mediated Treg tumor accumulation requires JAK/STAT3 signaling.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of pSTAT3 (STAT3Y705) levels in tumor-associated CD4+ Foxp3+ T cells in E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. (B) Western blotting of pSTAT3 and S1PR1 expression in TDLN and tumor-associated CD4+ T cells enriched from B16 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. (C–D) Western blotting of pSTAT3 and S1PR1 expression in splenic CD4+ T cells enriched from B16 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice (C) or from B16 tumor-bearing S1pr1+/+ and S1pr1−/− mice (D) stimulated with or without B16 TCM. All western blotting data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. (E) In vitro migration of WT splenic Foxp3-CD4+ (Tconv) and Foxp3+CD4+ (Treg) T cells toward media or 20% B16 TCM. Flow cytometry analysis of migrated CD4+ T cells (left) and quantification of migration (right). n = 3 per condition. Data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. (F) In vitro migration of WT and S1pr1-Tg splenic Tregs toward media or 20% B16 TCM, in the presence or absence of 5 µM AZD1480. n = 3 per condition. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. (G) Foxp3+ of CD4+ T cells in the tumor, TDLN, and spleen of B16 tumor-bearing Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with WT, S1pr1-Tg, Stat3−/−, or S1pr1-Tg/Stat3– /– CD4+ T cells. n = 6 per group. (H) Endpoint B16 tumor volumes in Rag1−/−mice reconstituted with WT, S1pr1-Tg, Stat3−/−, or S1pr1-Tg/Stat3−/− CD4+ T cells. n = 6 per group. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Our recent studies indicate that S1PR1 activates STAT3 signaling through JAK2 (Lee et al., 2010). Thus, we next evaluated whether tumor-induced factors that recruit Tregs require S1PR1-JAK/STAT3 signaling using an in vitro cell migration system. Although TCM modestly induced conventional T cell (Tconv) migration in vitro, TCM induced Treg migration (Figure 4E), supporting the high Treg/Tconv ratio in tumors in vivo. Importantly, Tregs from S1pr1-Tg mice migrated significantly more towards TCM compared with WT Tregs (Figure 4F), while Tconv cells, but not Tregs, migrated towards exogenous S1P (Supplemental Figure 4A–B). To further investigate potential mechanisms involved in S1PR1-dependent Treg migration towards tumor-derived factors, we reduced lipid levels by using charcoal-stripped TCM. Lipid-depleted TCM failed to induce Treg migration, which was not restored by only adding exogenous S1P (Supplemental Figure 4C). These data suggest that S1PR1-induced Treg migration towards TCM may require other lipid signaling mediators, in addition to S1P, although further investigation is warranted. WT and S1pr1-Tg Treg migration towards TCM was nearly completely abrogated with the JAK inhibitor AZD1480 (Hedvat et al., 2009) (Figure 4F), highlighting a central role for JAK/STAT3 signaling in S1PR1-mediated recruitment of Tregs to tumors.

To further validate the role of STAT3 signaling in S1PR1-mediated tumor recruitment of Tregs in vivo, we utilized the adoptive transfer system to generate chimeric mice with WT or S1pr1 over-expressing CD4+ T cells, with intact or deficient Stat3. In the adoptive transfer system, while T cell-Stat3 itself had little effect on Treg accumulation in tumors, ablating Stat3 in T cells completely blocked the increased Treg accumulation by over-expression of S1pr1 (Figure 4G). This effect on Treg recruitment was specific to tumors, since there was little changes in splenic or TDLN-associated Tregs in either WT or S1pr1-Tg chimeric mice by ablating Stat3. Furthermore, ablating Stat3 in T cells also inhibited the tumor-promoting effects of S1pr1 over-expression in these mice (Figure 4H). Of note, tumors growth trended higher in mice adoptively transferred with Stat3−/− CD4+ T cells compared with WT chimeric mice, but these mice did not show enhanced growth with over-expression of S1pr1 in CD4+ T cells. This phenomenon was likely due to a slight defect in homeostatic proliferation of CD4+ T cells by Stat3 ablation (Durant, Immunity 2010), thus affecting reconstituted CD4+ T cell numbers and corresponding tumor growth kinetics in these mice. In summary, we have demonstrated that S1PR1 signaling in T cells is critical for the tumor accumulation of Tregs, limiting CD8+ T cell infiltration and activation, and regulating tumor growth. Importantly, S1PR1 is a GPCR, which is more readily targetable than transcription factors, such as STAT3. Overall, these studies may provide new insight into targeting strategies to modulate the Treg-induced immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment for improving cancer immunotherapies.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

S1pr1loxp/loxp mice were kindly provided by Dr. Richard Proia (National Institutes of Health) and crossed with CD4-Cre mice (Taconic) to generate S1pr1 deletion in T cells (S1pr1−/−). Stat3loxp/loxp mice were kindly provided by Drs. Shizuo Akira and Kiyoshi Takeda (Osaka University, Japan) and crossed with CD4-Cre mice to generate Stat3 deletion in T cells (Stat3−/−). Transgenic mice expressing human S1pr1 under the control of the human CD2 promoter (S1pr1-Tg) were kindly provided by Dr. Markus Gräler (Hannover Medical School, Germany). S1pr1-Tg mice were crossed with the CD4-Cre/Stat3loxp/loxp mice to generate mice with S1pr1-Tg/Stat3−/− T cells. Foxp3-GFP knock-in mice were obtained from Dr. Defu Zeng (City of Hope) and subsequently crossed with S1pr1-Tg mice. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. Rag1−/− and Rag2−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Mouse care and experimental procedures were performed in accordance with established institutional guidance and approved protocols from Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Beckman Research Institute of City of Hope National Medical Center.

In vivo tumor studies

The B16 mouse melanoma cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The MB49 mouse bladder carcinoma line was kindly provided by Dr. J. Fidler (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center) and maintained in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS. For the B16 and MB49 tumor models, 1×105 or 5×105 cells were subcutaneously injected into 8–10 weeks old C57BL/6, Rag1−/−, or Rag2−/− mice. The E0771 mouse breast cancer cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Andreas Moeller (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Australia) and maintained in DMEM medium containing 20% FBS. For the E0771 tumor model, 1×105 E0771 cells were orthotopically injected into the 4th mammary fat pad of 8–10 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice. Tumor volumes were measured every other day and mice were euthanized once the control tumors reached approximately 1000mm3.

For adoptive T cell transfer, WT, S1pr1-Tg, Stat3−/−, and S1pr1-Tg/Stat3−/− CD4+ T cells as well as WT and S1pr1-Tg CD8+ T cells were positively enriched using MACS cell separation kits (Miltenyl Biotec). 5×106 enriched T cells were retro-orbitally injected into 8–10 weeks old Rag1−/− mice, which were subcutaneously implanted with 1×105 B16 cells one week later. For co-adoptive T cell transfer, WT and S1pr1-Tg splenic T cells were enriched using MACS cell separation, and 2×106 cells were retro-orbitally injected into 8–10 weeks old Rag2−/− mice, which were subcutaneously implanted with 5×105 MB49 cells one day later. For in vivo treatment with FTY720 (synthesized by the Synthetic and Biopolymer Chemistry Core at City of Hope), 8–10 weeks old Foxp3-GFP mice were subcutaneously implanted with 5×105 B16 cells and were retro-orbitally injected with 200 µL PBS containing 2.5% DMSO alone or 50 µg FTY720 in 2.5% DMSO once tumors reached 300–500 mm3 in size. Mice were euthanized 24 h later and tissues were collected for further analysis.

In vitro T cell migration

Migration assays were carried out using the Corning HTS Transwell 96-well permeable support system with 5.0 µm pore size polycarbonate membrane. The bottom wells were filled with 200 µL migration buffer alone (RPMI-1640 medium with 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA and 10 mM HEPES) or migration buffer containing either 10 nM S1P (Sigma-Aldrich) or 20% B16 tumor-conditioned media (TCM). To prepare B16 TCM, single-cell suspensions from B16 tumors grown in WT mice were plated at 1 × 106/mL in serum-free RPMI-1640 media for 24 hours (Deng et al., 2012). Media was collected, 0.22 µm filtered, aliquoted and stored at −80°C. To deplete lipids, TCM was incubated with dextran-coated charcoal (T-70, Sigma) at 10 mg/mL for 30 min. Total splenocytes harvested from tumor-bearing mice were stained with APC-CD3 and PE-CD4 antibodies. Cells were then washed three times and resuspended in migration buffer to a final concentration of 1 × 107/mL. In some experiments, cells were then incubated with or without 5 µM AZD1480 (AstraZeneca) at 37°C for 30 min. 50 µL of cells was added into each top well and allowed to migrate at 37°C for 1–2 hrs. Migrated cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with FITC-Foxp3 antibody, and migrated cells in the bottom wells were counted by flow cytometry (Accuri, BD Biosciences). Triplicates were performed for each condition.

Intracellular staining and flow cytometry

To prepare single-cell suspensions for flow cytometry, tumor tissue was dissected into approximately 1–5 mm3 fragments and digested with collagenase Type D (2 mg/mL, Roche) and DNase I (1 mg/mL, Roche) for 30–45 min at 37°C. Digests were filtered through 70-µm cell strainers, pelleted (1500 rpm for 5 min), and for B16 tumors, immune cells were enriched from tumor digests using Histopaque-1083 (Sigma-Aldrich). Spleens and lymph nodes were gently dissociated under 70-µm mesh for single-cell isolation. After RBC lysis (Sigma-Aldrich), single-cell suspensions were filtered, washed and resuspended in FACS Wash Buffer (2% FBS in HBSS without Ca, Mg, and phenol red). Cells were blocked with CD16/32 and incubated for 30 min on ice with fluorescein isothiocyanate-, phycoerythrin-, allophycocyanin-, peridinin chlorophyll protein-Cy5.5-, PE-Cy7-, Alexa Fluor-700, Pacific Blue, and APC-Cy7 (or Alexa Fluor-e780)-conjugated antibodies (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD62L, CD69, IFNγ and Granzyme B) purchased from Biolegend, eBioscience, or BD Bioscience. FITC-Foxp3 antibody was purchased from eBioscience. Aqua LIVE/DEAD used for cell viability was purchased from Invitrogen. Cells were washed twice before analysis on the BD LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Foxp3 Fixation/Permeabilization kit (eBioscience) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Following two washes, cells were stained for 30 min on ice with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies. For intracellular pSTAT3, cell surface markerstained cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with −20°C methanol, blocked with mouse serum, and incubated at ART for 30 min with Alexa Fluor-647 anti-phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3, Y705), purchased from BD Biosciences. Cells were washed twice before flow cytometric analysis. Cell sorting was performed on the BD FACS Aria-III (or Aria-III SORP) high-speed cell sorter using fluorophore-conjugated antibodies with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) for viability. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Real-time quantitative PCR

Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells were FACS sorted from E0771 tumor-bearing WT and S1pr1-Tg mice. RNA was extracted using column purification (Ambion RNAqueous Micro kit). cDNA was prepared using Bio-Rad cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). RT-PCR was performed using Bio-Rad SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers were generated using SciTools (Integrated DNA Technologies) and PubMed blasted for gene and species specificity. Each primer set was validated using a standard curve across the dynamic range of interest with a single melting peak.

Western blotting

For western blotting, CD4+ T cells were positively enriched using the EasySep cell isolation kit (Stemcell Technologies). In some experiments, enriched cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 2% FBS with or without 20% B16 TCM at 37 °C. Cells were lysed in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein lysates (5 – 20 µg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, probed with indicated antibodies, and detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce). Polyclonal antibodies against STAT3 and S1PR1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Monoclonal β-Actin antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Phospho-STAT3 (Y705) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error mean (SEM), unless otherwise stated. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test to calculate p-value. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

S1PR1 regulates tumor accumulation of Tregs, while restraining Tregs in the periphery

S1PR1-mediated Treg accumulation limits CD8+ T cell recruitment and activation in tumors

S1PR1 signaling in CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells promotes tumor growth

S1PR1-mediated tumor accumulation of Tregs requires JAK/STAT3 signaling

Acknowledgments

We thank staff members of the Flow Cytometry Core and Animal Facility Core in the Beckman Research Institute at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center for excellent technical assistance. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant numbers R01CA122976, U54CA163117, R01CA146092, as well as by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30CA033572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported by Tim Nesviq Fund at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center and the HEADstrong Foundation in memory of Nicholas E. Colleluori.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnon TI, Xu Y, Lo C, Pham T, An J, Coughlin S, Dorn GW, Cyster JG. GRK2-dependent S1PR1 desensitization is required for lymphocytes to overcome their attraction to blood. Science. 2011;333:1898–1903. doi: 10.1126/science.1208248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry A, Rudensky AY. Control of inflammation by integration of environmental cues by regulatory T cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:939–944. doi: 10.1172/JCI57175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Liu S, Park D, Kang Y, Zheng G. Depleting intratumoral CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells via FasL protein transfer enhances the therapeutic efficacy of adoptive T cell transfer. Cancer research. 2007;67:1291–1298. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrasse-Jeze G, Bergot AS, Durgeau A, Billiard F, Salomon BL, Cohen JL, Bellier B, Podsypanina K, Klatzmann D. Tumor emergence is sensed by self-specific CD44hi memory Tregs that create a dominant tolerogenic environment for tumors in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:2648–2662. doi: 10.1172/JCI36628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Liu Y, Lee H, Herrmann A, Zhang W, Zhang C, Shen S, Priceman SJ, Kujawski M, Pal SK, Raubitschek A, Hoon DS, Forman S, Figlin RA, Liu J, Jove R, Yu H. S1PR1-STAT3 signaling is crucial for myeloid cell colonization at future metastatic sites. Cancer cell. 2012;21:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant L, Watford WT, Ramos HL, Laurence A, Vahedi G, Wei L, Takahashi H, Sun HW, Kanno Y, Powrie F, O'Shea JJ. Diverse targets of the transcription factor STAT3 contribute to T cell pathogenicity and homeostasis. Immunity. 2010;32:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Zhu X, Sasaki K, Ueda R, Low KL, Pollack IF, Okada H. Inhibition of STAT3 promotes the efficacy of adoptive transfer therapy using type-1 CTLs by modulation of the immunological microenvironment in a murine intracranial glioma. Journal of immunology. 2008;180:2089–2098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl EJ, Liao JJ, Huang MC. Regulation of the roles of sphingosine 1-phosphate and its type 1 G protein-coupled receptor in T cell immunity and autoimmunity. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2008;1781:503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graler MH, Huang MC, Watson S, Goetzl EJ. Immunological effects of transgenic constitutive expression of the type 1 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor by mouse lymphocytes. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:1997–2003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedvat M, Huszar D, Herrmann A, Gozgit JM, Schroeder A, Sheehy A, Buettner R, Proia D, Kowolik CM, Xin H, Armstrong B, Bebernitz G, Weng S, Wang L, Ye M, McEachern K, Chen H, Morosini D, Bell K, Alimzhanov M, Ioannidis S, McCoon P, Cao ZA, Yu H, Jove R, Zinda M. The JAK2 inhibitor AZD1480 potently blocks Stat3 signaling and oncogenesis in solid tumors. Cancer cell. 2009;16:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortylewski M, Xin H, Kujawski M, Lee H, Liu Y, Harris T, Drake C, Pardoll D, Yu H. Regulation of the IL-23 and IL-12 balance by Stat3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer cell. 2009;15:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawski M, Zhang C, Herrmann A, Reckamp K, Scuto A, Jensen M, Deng J, Forman S, Figlin R, Yu H. Targeting STAT3 in adoptively transferred T cells promotes their in vivo expansion and antitumor effects. Cancer research. 2010;70:9599–9610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Deng J, Kujawski M, Yang C, Liu Y, Herrmann A, Kortylewski M, Horne D, Somlo G, Forman S, Jove R, Yu H. STAT3-induced S1PR1 expression is crucial for persistent STAT3 activation in tumors. Nature medicine. 2010;16:1421–1428. doi: 10.1038/nm.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Nagahashi M, Kim EY, Harikumar KB, Yamada A, Huang WC, Hait NC, Allegood JC, Price MM, Avni D, Takabe K, Kordula T, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate links persistent STAT3 activation, chronic intestinal inflammation, and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer cell. 2013;23:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Burns S, Huang G, Boyd K, Proia RL, Flavell RA, Chi H. The receptor S1P1 overrides regulatory T cell-mediated immune suppression through Akt-mTOR. Nature immunology. 2009;10:769–777. doi: 10.1038/ni.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Yang K, Burns S, Shrestha S, Chi H. The S1P(1)-mTOR axis directs the reciprocal differentiation of T(H)1 and T(reg) cells. Nature immunology. 2010;11:1047–1056. doi: 10.1038/ni.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailloux AW, Young MR. Regulatory T-cell trafficking: from thymic development to tumorinduced immune suppression. Critical reviews in immunology. 2010;30:435–447. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i5.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, Quackenbush E, Xie J, Milligan J, Thornton R, Shei GJ, Card D, Keohane C, Rosenbach M, Hale J, Lynch CL, Rupprecht K, Parsons W, Rosen H. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296:346–349. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cinamon G, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Brinkmann V, Allende ML, Proia RL, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 2004;427:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menetrier-Caux C, Curiel T, Faget J, Manuel M, Caux C, Zou W. Targeting regulatory T cells. Targeted oncology. 2012;7:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s11523-012-0208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougiakakos D, Choudhury A, Lladser A, Kiessling R, Johansson CC. Regulatory T cells in cancer. Advances in cancer research. 2010;107:57–117. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(10)07003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa H, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in tumor immunity. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2010;127:759–767. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallandre JR, Brillard E, Crehange G, Radlovic A, Remy-Martin JP, Saas P, Rohrlich PS, Pivot X, Ling X, Tiberghien P, Borg C. Role of STAT3 in CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory lymphocyte generation: implications in graft-versus-host disease and antitumor immunity. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:7593–7604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2008;8:753–763. doi: 10.1038/nri2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel S, Milstien S. The outs and the ins of sphingosine-1-phosphate in immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2011;11:403–415. doi: 10.1038/nri2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Wang F, Kong LY, Xu S, Doucette T, Ferguson SD, Yang Y, McEnery K, Jethwa K, Gjyshi O, Qiao W, Levine NB, Lang FF, Rao G, Fuller GN, Calin GA, Heimberger AB. miR-124 inhibits STAT3 signaling to enhance T cell-mediated immune clearance of glioma. Cancer research. 2013 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in immune surveillance and treatment of cancer. Seminars in cancer biology. 2006;16:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Kortylewski M, Pardoll D. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of STAT3 in the tumour microenvironment. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2007;7:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nri1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nature reviews. Cancer. 2009;9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.