Abstract

The development of a radiation induced second primary cancer (SPC) is one the most serious long term consequences of successful cancer treatment. This review aims to evaluate SPC in prostate cancer (PCa) patients treated with radiotherapy, and assess whether radiation technique influences SPC. A systematic review of the literature was performed to identify studies examining SPC in irradiated PCa patients. This identified 19 registry publications, 21 institutional series and 7 other studies. There is marked heterogeneity in published studies. An increased risk of radiation-induced SPC has been identified in several studies, particularly those with longer durations of follow-up. The risk of radiation-induced SPC appears small, in the range of 1 in 220 to 1 in 290 over all durations of follow-up, and may increase to 1 in 70 for patients followed up for more than 10 years, based on studies which include patients treated with older radiation techniques (i.e. non-conformal, large field). To date there are insufficient clinical data to draw firm conclusions about the impact of more modern techniques such as IMRT and brachytherapy on SPC risk, although limited evidence is encouraging. In conclusion, despite heterogeneity between studies, an increased risk of SPC following radiation for PCa has been identified in several studies, and this risk appears to increase over time. This must be borne in mind when considering which patients to irradiate and which techniques to employ.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Second primary cancer, Systematic review

The development of a radiation induced second primary cancer (RISPC) is one of the most serious long term consequences of successful cancer treatment. Patients diagnosed with early or locally advanced prostate cancer (PCa) face a variety of treatment options, several of which involve ionising radiation: external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), brachytherapy (BT) or combination EBRT and BT (EBRT–BT) might be employed. Modern radiotherapy techniques such as IMRT result in changes in dose distribution and scatter which have resulted in theoretical concerns about an increased risk of RISPC [1]. Patients are now diagnosed with PCa at an earlier stage than in the past and so may receive treatment sooner in the course of the disease. In addition, patients now survive for longer following their diagnosis. As such the long term consequences of treatment, including the risk of RISPC, become particularly relevant.

Studies of Atomic bomb survivors demonstrated that there is a latency period of at least five years before the development of solid RISPCs [2]. A second primary cancer (SPC) is generally considered radiation induced if: (i) it is diagnosed after a latency period (usually considered to be 5 years or more) following irradiation, (ii) it occurs within the radiation field (for prostate radiotherapy, this includes the rectum, bladder, anus, prostate, soft tissues, bones or joints of the pelvis and pelvic lymphoma), (iii) it is a different histological type to the original cancer and (iv) the second tumour was not evident at the time of radiotherapy [3,4]. More commonly, PCa patients may develop subsequent SPCs which are not radiotherapy induced, but are the result of genetic and environmental factors. The distinction between RISPC and SPC can become blurred as regions beyond the primary radiation field are exposed to scattered doses of radiation, and theoretically these may increase the risk of RISPCs in out-of-field regions.

When evaluating SPCs in irradiated PCa patients, registry databases provide very large numbers of patients for analysis, and therefore have sufficient power to observe differences between patient groups. The information within registries, however, is less complete than that from institutional series. In depth details regarding treatment are often absent and details of potential confounding factors (e.g. smoking status) are often not recorded. Registries may also suffer from under-reporting of SPCs, particularly in elderly patients.

Institutional data provide more detailed information and so confounding factors may be easier to identify. Patient numbers, however, are smaller and therefore power to detect real differences in SPC incidences is limited. Institutional data do not come with its own ‘normal population’ for comparison, and so external comparators must be used. Some institutional studies only report crude rates of SPC, rather than making comparisons with SPC in non-irradiated patients or the general population, thus limiting the usefulness of these data. Series examining survival following prostate irradiation may report number of deaths due to SPCs but again, risk comparisons may not be performed.

This work reviews published registry and institutional data with particular regard to the impact of treatment technique on the risk of second cancers.

Objectives

To evaluate SPCs in PCa patients treated with radiotherapy, and to evaluate whether different radiotherapy techniques result in different risks of SPCs.

Methods

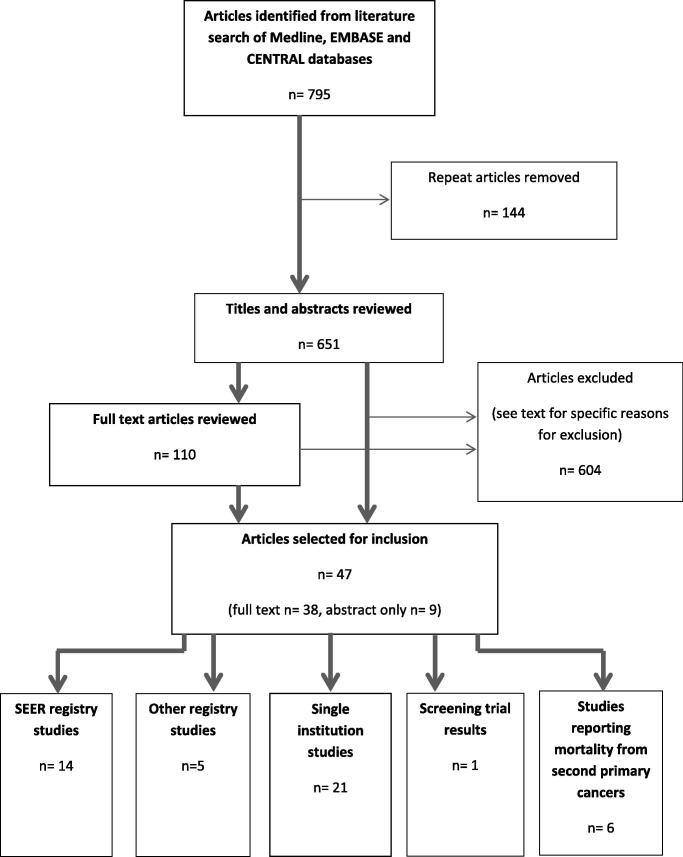

A systematic search of the literature was performed using Medline, EMBASE and CENTRAL databases. Search terms were related to SPC and RISPC, and radiotherapy and PCa. References and “related articles” of relevant articles were also reviewed. Studies in English which reported rates of, or mortality from, any SPC, rectal cancer or bladder cancer following radical irradiation for prostate adenocarcinoma were included. Studies published in full text and abstract form were included. Studies involving radiotherapy for paediatric and non-adenocarcinoma PCa were excluded. Studies examining prostate cancers as a whole, without specifically examining SPC risk in irradiated PCa patients, were also excluded. Case studies and series limited to 10 or fewer patients, and studies examining palliative radiotherapy alone, were excluded. The last search was performed on the 10th September 2013. This strategy identified 651 different articles. Reasons for exclusion included articles: not dealing with SPC (n = 241), planning studies (n = 101), primary tumour not specifically adenocarcinoma PCa (n = 74), about management of SPC but not risk (n = 3), review articles (n = 53), case reports (n = 25), not in English language (n = 24), patients treated with non-standard therapy (e.g. high dose chemotherapy; n = 6), letters/editorials without new data (n = 19), studies reporting laboratory based work (n = 6), early versions of later full study (n = 14), patients treated with palliative therapies alone (n = 20), studies examining risks related to concomitant imaging (n = 3), studies not examining irradiated PCa patients specifically (n = 2), studies examining specific second cancer other than rectal or bladder cancer (n = 3) and studies that did not specifically evaluate risks from PCa radiation (n = 10). In total, 14 SEER, 5 other registries, and 21 institutional studies were identified as well one paper reporting the results of a screening trial that examined second cancers and 6 studies reporting mortality due to SPC (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schema of article selection process.

Results

The majority of evidence addresses SPC and RISPC in patients treated with primary EBRT (mainly in the form of non-conformal and 3D-conformal (3D-CRT) techniques) which is discussed initially, considering risk of SPC overall, then rectal and bladder cancer, before evaluating SPCs following other irradiation techniques. Throughout this review, crude rates are stated as such, and wherever available, adjusted risk ratios and comparisons are presented in preference to unadjusted figures.

Overall second cancer risk associated with EBRT for prostate cancer

Compared to the general population, all four registry studies did not find irradiated patients to be at any significantly increased risk of SPC, both when considering all durations of follow-up (i.e. beyond any exclusion periods) and also when considering follow-up beyond 5 years [5–7] (Table 1). Although not reaching the threshold for statistical significance, Rapiti et al. did conclude that compared to the general population, irradiated PCa patients were at a slightly increased risk beyond 5 years which the group considered to be of “borderline significance” (p = 0.056) [8]. Brenner et al. found irradiated PCa patients to be at a significantly reduced risk of SPCs (standardised incidence ratio (SIR): 0.89) compared to the general population, although when patients under the age of 60 were considered alone, this deficit was no longer observed [6]. The low SPC incidence observed amongst irradiated PCa patients was attributed to the relatively elderly population evaluated. Bagshaw et al., a single institution study, also found irradiated patients not to be at increased risk of SPC compared to the general population [9].

Table 1.

Studies examining second primary cancers at any site in prostate cancer patients irradiated using external beam radiotherapy compared to general population.

| Study | Type of data | Period examined | No. patients | Median follow-up (years) | Exclusions | Time period(s) assessed | Risk of second cancer at any site (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk (SIR, 95% confidence interval or p value in parentheses if available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pawlish (1997) [5] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1982 | 2087 | 6.1 (mean FU reported) | <1 year FU | >1 year FU | No difference | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) |

| Brenner (2000) [6] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1993 | 51,584 | 4 (mean FU reported) | <2 months | >2 months | Reduced | 0.89⁎ |

| >5 years | Reduced | 0.92⁎ | ||||||

| >10 years | Reduced | 0.96⁎ | ||||||

| Pickles (2002) [7] | Retrospective, British Columbia Tumor Registry | 1984–2000 | 9890 | 4.77 | <2 months | >2 months | No difference | 1.01 (p = 0.9) |

| 2 months–5 years | No difference | 0.96 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| >5 years | No difference |

1.08 (NS⁎) |

||||||

| >10 year | No difference | 1.12 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| Rapiti (2008) [8] | Retrospective, Geneva Cancer Registry | 1980–1998 | 264 | 7.8 | <5 years | >5 years | No difference⁎⁎ | 1.35 (p = 0.056) |

| 5–9 years | No difference | 1.28 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| ⩾10 years | No difference | 1.55 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| Bagshaw (1988) [9] | Retrospective, single institution | 1956–1985 | 914 | NR | None | All periods | No difference | 0.93 (p = 0.48) |

SIR: standardised incidence ratio, NR: not reported, NS: not significant, FU: follow-up.

p Value and/or confidence interval not reported.

The group concluded irradiated patients were at a slightly increased risk which was “of borderline significance”.

Comparing irradiated PCa patients with a non-irradiated PCa cohort may be considered more representative than comparisons with the general population, and in this situation different results are observed to those above (Table 2). All four registry studies found irradiated patients to be at increased risk of SPC compared to non-irradiated PCa patients [5,6,10,11]. This increased risk began after 1 year of follow-up in two of these studies [5,10], and was observed after 5 years of follow-up in the three studies which specifically examined this time period [6,10,11].Risk increased further beyond 10 years of follow-up in the one study which examined this period [6]. Similarly, data from prostate patients treated within the PLCO (prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian) screening trial demonstrated that irradiated PCa patients had a significantly increased risk of any second cancer (incidence: 15.5/1000 person-years in irradiated patients vs. 11.4/1000 person-years in non-irradiated patients) beyond 30 days and beyond 5 years [12].

Table 2.

Studies examining second primary cancers at any site in prostate cancer patients irradiated using external beam radiotherapy compared to non-irradiated prostate cancer patients.

| Study | Type of data | Period examined | No. patients | Median follow-up (years)† | Exclusions | Time period(s) assessed | Risk of second cancer at any site (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk (relative risk or other where stated (95% CI or p value if available)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pawlish (1997) [5] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1982 | 2087 RT | 6.1 (mean) | <1 year | >1 year | Increased | 1.23 (1.06–1.42) |

| 6390 no RT | ||||||||

| Brenner (2000) [6] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1993 | 51,584 RT | 4 (mean) | <2 months | Percentage increase in risk: | ||

| 70,539 no RT | >2 months | No difference | 4 (−1 to 9, p = 0.08) | |||||

| >5 years | Increased | 11 (3–20, p = 0.007) | ||||||

| >10 years | Increased | 27 (9–48, p = 0.002) | ||||||

| Abdel-Wahab (2008) [10] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2002 | 48,400 RT | 5.3 RT | <1 year | >1 year | Increased | HR: 1.137 (1.087–1.190) |

| 40,733 no RT | 4.3 no RT | >5 years | Increased | HR: 1.263 (1.167–1.367) | ||||

| De Gonzalez (2011) [11] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2002 | 76,363 RT | 9.4 RT (mean) | <5 years | >5 years | Increased | 1.26 (1.21–1.30) |

| 123,800 no RT | 10.1 no RT (mean) | |||||||

| Movsas (1998) [14] | Retrospective, Single Institution | 1973–1993 | 543 RT | 3.9 RT | <2 months | Crude rates (RT vs. no RT): | ||

| 18,135 no RT⁎ | 3.9 no RT (mean) | >2 months | No difference | 5.7% vs. 5.8% (p = 0.99) | ||||

| >2 months–9 years | No difference | 0.74% vs. 0.9% (p = 0.89) | ||||||

| 1–4.9 years | No difference | 3.8% vs. 3.6% (p = 0.95) | ||||||

| 5–9.9 years | No difference | 4.3% vs. 4.4% (p = 0.89) | ||||||

| >10 years | No difference | 0% vs. 8.3% (p = 0.56) | ||||||

| Huang (2011) [13] | Retrospective, Single Institution matched-pair analysis | 1984–2005 | 2120 RT | 7.15 RT | None | All durations | No difference | HR: 1.14 (0.94–1.39) |

| 2120 no RT | 6.99 no RT | |||||||

| >5 years | Increased | HR: 1.86 (1.36–2.55) | ||||||

| >10 years | Increased | HR: 4.94 (2.18–11.2) | ||||||

| Black (2013) [12] | Prospective, trial data | 1993–2001 | 3216 RT | 6 (mean) | >30 days | >30 days | Increased | 1.25 (1.1–1.5) |

| 4263 no RT | >5 years | Increased | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | |||||

RT: external beam radiotherapy, HR: hazard ratio, CI: confidence interval, NR: not reported.

If follow-up for each treatment group reported separately, then this is presented.

Non-RT patients from Connecticut Cancer Registry, approximately 12.5% received RT despite being considered as ‘no RT’ group.

In terms of single institution studies, Huang et al. compared SPC incidence between 2120 irradiated and 2120 surgically treated patients within a matched-pair analysis [13]. Most irradiated patients were treated with EBRT alone (as opposed to with EBRT–BT). Over all durations of follow-up there was no significant increased risk of SPC in irradiated patients, but, in keeping with the registry studies above, after 5 and 10 years there was a significant increase in risk of SPC in irradiated patients. After 10 years this risk was almost 5 times that of surgical patients [13]. In contrast, Movsas et al., the smallest study examined here, and the study with the shortest median follow-up, found irradiated PCa patients to be at no increased risk of SPC over all durations of follow-up, from 5 to 9.9 years, and beyond 10 years, compared to PCa patients from the SEER database (of whom only 12.5% were irradiated) [14].

Single institution studies reporting crude rates of SPC (Supplementary Material Table 1) include Johnstone et al. who reported a crude SPC rate of 17.5% beyond one year of PCa diagnosis, in a series of 154 irradiated patients after a median potential follow-up of 10.9 years [15]. This was not significantly different to the rate of non-prostate cancers diagnosed prior to PCa diagnosis (p = 0.288). Gardner et al. and Zilli et al. reported crude rates of 2.6% over all durations of follow-up and 5.4% beyond 6 months of follow-up respectively [16,17]. Long term trial results reported by Bolla et al. revealed a crude rate of SPCs in irradiated patients of 7.7% over all durations of follow-up [18]. Median follow-up is variable between these studies, and no comparisons with other population groups are performed, limiting the usefulness of these figures.

Studies examining mortality in irradiated PCa patients (Supplementary Material Table 2) reveal that up to to 4.1% of patients (crude rates) irradiated with EBRT die from SPCs although, as above, duration of follow-up is different in all studies and so these figures must be interpreted with caution [14,18,19]. In one study, 10% of all deaths were the result of second malignancies [20].

Overall, therefore, an increase in SPC has not been consistently demonstrated in irradiated patients compared to the general population. There is more consistent evidence, however, of an increase in SPC risk in comparison to non-irradiated PCa patients, particularly with increasing durations of follow-up. This raises the possibility that PCa patients are different to the general population, and so non-irradiated PCa patients and the general population should not be considered equivalent.

Patient age has an impact on SPC incidence, as illustrated by Brenner et al. above [6]. Length of follow-up is also important, and studies with shorter durations of follow-up may not detect all SPCs. Brenner et al. and Huang et al. illustrated that the relative risk of SPC in irradiated patients increased over time compared to surgically treated patients [6,13]. Brenner et al. demonstrated a 6% increase in relative risk overall for any second solid cancer, which increased to 15% and 34% beyond 5 and 10 years respectively. In absolute terms, the risk of radiation-associated SPC was 1 in 290 over all durations of follow-up, 1 in 125 beyond 5 years and 1 in 70 for those surviving beyond 10 years[6]. Similarly, Pickles et al. reported a crude risk estimate of 1 in 220 over all durations of follow-up, which is not dissimilar [7].

Second rectal cancer risk associated with EBRT for prostate cancer

Amongst the five SEER registry studies examining rectal cancer in irradiated PCa patients compared to the general population (Table 3), three show no increase in rectal cancer risk [5,21,22], while the remaining two, the only two which examined follow-up beyond 10 years, found an increased risk in irradiated patients which only began beyond 10 years [6,23]. Of the three non-SEER registry studies, one found no increase in risk from irradiation beyond 5 years, nor beyond 10 years [8] although the number of irradiated PCa patients was relatively small, while another demonstrated increased risk of rectal cancer following irradiation beyond 6 months and beyond 5 years of follow-up [24], and the third demonstrated increased risk of colorectal cancer beyond 2 months of follow-up and between 2 months and 5 years of follow-up, but not beyond 5 years or beyond 10 years [7].

Table 3.

Studies examining second rectal and second bladder cancers in irradiated prostate cancer patients compared to general population.

| Study | Type of data | Period | No. patients | Median follow-up (years) | Exclusions | Time period(s) assessed | Risk of second rectal cancer (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk of rectal cancer (SIR (95% CI or p value if available) | Risk of second bladder cancer (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk of bladder cancer (SIR (95% CI or p value if available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neugut (1996) [21] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1990 | 34,889 | NR | <6 months | >6 months–5 years | Reduced | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | No difference | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

| 5–8 years | No difference | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | No difference | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | ||||||

| >8 years | No difference | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | Increased | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | ||||||

| Pawlish (1997) [5] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1982 | 2087 | 6.1 (mean) | <1 year | >1 year | No difference | 0.95 (0.45–1.74) | Increased | 1.49 (1.07–2.02) |

| >5 years | NR | NR | Increased | 1.60 (1.05–2.35) | ||||||

| Brenner (2000) [6] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1993 | 51,584 | 4 (mean) | <2 months | >2 months | Reduced | 0.82⁎ | Increased | 1.10⁎ |

| >5 years | Reduced | 0.95⁎ | Increased | 1.20⁎ | ||||||

| >10 years | Increased | 1.18⁎ | Increased | 1.32⁎ | ||||||

| Nieder (2008) [22] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1988–2003 | 93,059 | 4.1 | 6 months | >6 months | No difference | 0.99 (0.90–1.10) | Increased | 1.42 (1.34–1.50) |

| Huo (2009) [23] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2005 | 211,882 | NR | None | All | No difference | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | NR | NR |

| <6 months | No difference | 0.99 (0.77–1.27) | ||||||||

| 6 months–5 years | No difference | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | ||||||||

| >5–10 years | No difference | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) | ||||||||

| >10 years | Increased | 1.44 (1.22–1.71) | ||||||||

| Pickles (2002) [7] | Retrospective, British Columbia Tumor Registry | 1984–2000 | 9890 | 4.77 | <2 months | >2 months | Increased† | 1.21 (p ⩽ 0.01)† | No difference | 1.04 (NS⁎) |

| >2 months to 5 years | Increased† | 1.21(p ⩽ 0.05)† | No difference | 0.86 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| >5 years | No difference† | 1.24 (NS⁎)† | No difference | 1.30 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| >10 years | No difference† | 1.01 (NS⁎)† | No difference | 1.64 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| Rapiti (2008) [8] | Retrospective, Geneva Cancer Registry | 1980–1998 | 264 | 7.8 | <5 years | >5 years | No difference | 2.0 (0.2–7.2) | No difference | 1.84 (NS⁎) |

| >5–9 years | No difference | 1.2 (0.04–6.9) | No difference | 0.80 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| ⩾10 years | No difference | 5.3 (0.2–29.3) | No difference | 5.15 (NS⁎) | ||||||

| Margel (2011) [24] | Retrospective, Israel Cancer Registry | 1982–2005 | 2163 | 11.2 | <6 months | >6 months | Increased | 1.81 (1.2–2.5) | NR | NR |

| >5 years | Increased | 1.30 (1.05–2.8) | ||||||||

| Bagshaw (1988) [9] | Retrospective, single institution | 1956–1985 | 914 | NR | None | All | No difference | 0.54 (p = 0.21) | No difference | 1.08 (p = 0.8) |

| Johnstone (1998) [15] | Retrospective, single institution | 1974–1988 | 154 | 10.9 (potential follow-up) | None | <1 year | Increased | p < 0.001⁎⁎ | Increased | p < 0.001⁎⁎ |

| 1–4 years | No difference | p = 0.64⁎⁎ | No difference | p = 0.88⁎⁎ | ||||||

| 4–10 years | No difference | p = 0.80⁎⁎ | No difference | p = 0.75⁎⁎ | ||||||

| >10 years | No difference | p = 0.69⁎⁎ | No difference | p = 0.66⁎⁎ | ||||||

| Chrouser (2005) [31] | Retrospective, single institution | 1980–1998 | 1743 | 7.1 (mean) | <30 days | >30 days | NR | NR | No difference | 0.798 (0.511–1.187) |

| >30 days to 1 year | No difference | 0.292 (0.007–1.619) | ||||||||

| 1–4 years | No difference | 0.909 (0.469–1.586) | ||||||||

| 5–9 years | No difference | 0.665 (0.267–1.367) | ||||||||

| 10–19 years | No difference | 1.37 (0.373–3.507) | ||||||||

| Singh (2005) [32] | Retrospective, single institution | 1996–2003 | 210 | NR | <6 months | >6 months | NR | NR | Increased | 7.27 (3.132–14.331) |

SIR: standardised incidence ratio, CI: confidence interval, NR: not reported, NS: not significant.

No p value or confidence interval provided.

SIRs and confidence intervals not reported.

Risk reported is for colorectal cancer.

Of the two single institution studies examining rectal cancer in irradiated PCa patients compared to the general population, one found no difference in the risk of rectal cancer following irradiation over all durations of follow-up [9], and one found an increased risk within 1 year of follow-up only [15].

Seven of the ten SEER registry studies comparing second rectal cancer incidence between irradiated and non-irradiated PCa patients demonstrated that irradiated patients were at increased risk (Table 4) [6,10,11,22,23,25,26]. This increased risk has been mainly observed after longer durations of follow-up (i.e. beyond 5 and 10 years), and appears to increase with increasing durations of follow-up. For example, the hazard ratios reported by Nieder et al., increase from 1.11 when considering follow-up from 6 months to 5 years (non-significant) to 1.39 (significant) between 5 and 10 years of follow-up to 1.79 (significant) from beyond 10 years [22]. Two of the ten SEER studies report no increase in the risk of second rectal cancer, one of which examined follow-up beyond 5 years specifically [5,27]. The one remaining SEER study, by Kendall et al., demonstrated that the specific comparator group with which irradiated PCa patients are compared might impact on the relative risk observed: when irradiated PCa patients were compared to patients treated surgically, there was a significantly increased risk of rectal cancer in irradiated patients, while compared to patients who did not receive RT or surgery, the risk of rectal cancer was significantly less, which the group felt was unrealistic [28]. Thus risk ratio was influenced by comparator group. The group therefore suggested an unidentified confounding factor was influencing results, and, after further analysis, concluded that there was insufficient evidence to confirm that irradiation for prostate cancer induced rectal cancer [28]. Indeed, Kendal et al.’s update from 2007 did not demonstrate any increase in the risk of second rectal cancer in irradiated patients over all durations of follow-up or beyond 5 years [27].

Table 4.

Studies examining second rectal and bladder cancers in prostate cancer patients irradiated using EBRT compared to non-irradiated prostate cancer patients.

| Study | Type of data | Period | No. patients | Median follow-up (years)ϐ | Exclusions | Time period(s) assessed | Risk of second rectal cancer (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk of second rectal cancer (relative risk or other where stated (95% CI or p value if available)) | Risk of second bladder cancer (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk of second bladder cancer (relative risk or other where stated (95% CI or p value if available)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pawlish 1997 [5] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1982 | 2087 RT 6390 no RT |

6.1 (mean) | <1 year | >1 year | No difference | NR | Increased | OR: 1.63 (p < 0.05)§ |

| Brenner (2000) [6] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1993 | 51,584 RT 70,539 no RT |

4 (mean) | <2 months | Percentage increase in risk: | Percentage increase in risk: | |||

| >2 months | No difference | −2 (−18 to 18, p = 0.87) | Increased | 15 (2–31, p = 0.02) | ||||||

| >5 years | No difference | 35 (−1 to 86, p = 0.06) | Increased | 55 (24–92, p < 0.01) | ||||||

| >10 years | Increased | 105 (9–292, p = 0.03) | Increased | 77 (14–163, p = 0.01) | ||||||

| Baxter (2005) [25] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1994 | 30,552 RT 55,263 no RT |

7.9 RT 8.3 no RT |

<5 years | >5 years | Increased | HR: 1.7 (1.4–2.2) | NR | NR |

| Kendal (2006) [28] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2001 | 33,831 RT 167,607 no RT (surgical patients) |

5.1 RT 5.1 no RT |

None | All | Increased | 2.38 (2.21–2.55)⁎ | NR | NR |

| 0–10 years | Increased | 2.16 (2.00–2.33) | ||||||||

| >10 years | Increased | 15.62 (12.01–19.83) | ||||||||

| Kendal (2006) [28] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2001 | 33,831 RT 36,335 no RT (non-surgical and no RT patients) |

5.1 RT 3.3 no RT |

None | All | Reduced | 0.69 (0.64–0.75)¶ | NR | NR |

| 0–10 years | Reduced | 0.66 (0.61–0.71) | ||||||||

| >10 years | No difference | 0.93 (0.64–1.46) | ||||||||

| Moon (2006) [26] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–1999 | 39,805 EBRT | 10 | <5 years | >5 years | Increased | OR: 1.60 (1.29–1.99) | Increased | OR: 1.63 (1.44–1.84) |

| Kendal (2007) [27] | Retrospective, SEER registry | Not stated | 520,780 (RT and no RT) | NR | None | All | No difference | NR | No difference | NR |

| >5 years | No difference | HR: 1.13 (0.98–1.31) | Increased | HR: 1.23 (1.15–1.32) | ||||||

| Nieder (2008) [22] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1988–2003 | 93,059 RT 109,178 no RT |

4.1 | 6 months | >6 months | Increased | HR: 1.26 (1.08–1.47) | Increased | HR: 1.88 (1.70–2.08) |

| 6 months–5 years | No difference | HR: 1.11 (0.90–1.37) | Increased | HR: 1.69 (1.47–1.94) | ||||||

| 5–10 years | Increased | HR: 1.39 (1.09–1.79) | Increased | HR: 2.26 (1.89–2.69) | ||||||

| >10 years | Increased | HR: 1.79 (1.05–3.07) | Increased | HR: 1.83 (1.31–2.55) | ||||||

| Abdel-Wahab (2008) [10] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2002 | 48,400 RT 40,733 no RT |

5.3 RT 4.3 noRT |

<1 year | Percentage increase in risk: | Percentage increase in risk: | |||

| 1–5 years | Increased† | 0.07%, p < 0.001† | Increased† | 0.07% p < 0.001† | ||||||

| >5 years | Increased† | 0.16%, p = 0.023† | Increased† | 0.16% p = 0.023† | ||||||

| Huo (2009) [23] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2005 | 211,882 RT 424,028 no RT |

NR | None | All | Increased | 1.91 (1.52–1.89) | NR | NR |

| Singh (2010) [33] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2005 | 124,141 RT 163,111 no RT |

5.3 RT 4.0 No RT |

None | All | NR | NR | Increased | HR: 1.19 (1.11–1.28) |

| >6 months | Increased | HR: 1.33 (1.23–1.44) | ||||||||

| >5 years | Increased | HR: 1.58 (1.38–1.81) | ||||||||

| >10 years | Increased | HR: 1.91 (1.40–2.62) | ||||||||

| De Gonzalez (2011) [11] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1973–2002 | 76,363 RT 123,800 no RT |

9.4 RT (mean) 10.1 no RT (mean) |

<5 years | 5–9 years | Increased‡ | 1.39 (1.29–1.50)‡ | Increased‡ | 1.39 (1.29–1.50)‡ |

| 10–14 years | Increased‡ | 1.59 (1.41–1.80)‡ | Increased‡ | 1.59 (1.41–1.80)‡ | ||||||

| >15 years | Increased‡ | 1.91 (1.53–2.38)‡ | Increased‡ | 1.91 (1.53–2.38)‡ | ||||||

| Pickles (2002) [7] | Retrospective, British Columbia Tumor Registry | 1984–2000 | 9890 RT 29,371 no RT |

4.77 RT 1.7 no RT |

<2 months | >2 months | Increased (colorectal) | 1.21 (p = 0.03) | No difference | NR (NS) |

| Boorjian (2007) [30] | Retrospective, CaPSURE Disease Registry |

1989–2003 | 2471 RT 4608 no RT |

3.3 | <30 days | >30 days | No difference | NR (p = 0.14) | Increased | HR: 1.96 (1.12–3.45) |

| Bhojani (2010) [29] | Retrospective, Quebec Health Plan database | 1983–2003 | 9390 RT 8455 no RT |

NR | <5 years | >5 years | Increased | HR: 1.9 (p = 0.01) | Increased | HR: 1.5 (p = 0.01) |

| >10 years | No difference | HR: 1.6 (p = 0.5) | Increased | HR: 2.0 (p = 0.1) | ||||||

| Movsas (1998) [14] | Retrospective, Single Institution | 1973–1993 | 543 RT 18,135 ‘no RT’⁎⁎ |

3.9 RT | <2 months | >2 months | NR | NR | No difference | NR |

| 3.9 no RT (mean) | ||||||||||

| Singh (2005) [32] | Retrospective, single institution | 1996–2003 | 210 RT 416 no RT |

NR | <6 months | >6 months | NR | NR | No difference | NR (No difference based on overlapping confidence intervals for SIRs for RT vs. general population and no RT vs. general population |

| Huang (2011) [13] | Retrospective, Single Institution matched-pair analysis | 1984–2005 | 2120 RT 2120 no RT |

6.99 RT 7.15 no RT |

None | All | No difference | HR: 0.91 (0.39–2.14) | Increased | HR: 2.02 (1.2–3.41) |

| >5 years | No difference | HR: 1.98 (0.36–10.83) | Increased | HR: 4.49 (1.70–11.85) | ||||||

| >10 years | No difference | p = 0.31¥ | Increased | HR: 9.70 (1.23–76.57) | ||||||

| Black (2013) [12] | Prospective, trial data | 1993–2001 | 3216 RT 4263 no RT |

6 (mean) | >30 days | >30 days | No difference (colorectal) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | No difference | 1.6 (0.9–2.8) |

HR: hazard ratio, OR: odds ratio, NR: not reported, NS: not significant, CI: confidence interval.

HR for all time periods also available: 2.42 (95%CI: 2.08–2.81).

Non-RT patients from Connecticut Cancer Registry, approximately 12.5% received RT despite being considered as ‘no RT’ group.

Ratio reported for any ‘primary pelvic’ second cancer, considered as rectum, bladder, anus, anal canal, anorectum, prostate and other cancer from the bones, joints and lymphomas based on comparisons of age-adjusted estimates and not on multivariate Cox regression, as was used for data in other tables.

Ratio reported for organs considered to be in ‘high dose’ (>5 Gy) sites, includes rectum and bladder.

Hazard ratio not calculated as too few events.

Relative risk also reported: 1.59 (95%CI: 1.09–232).

If follow-up for each treatment group reported separately, then this is presented.

HR for all time periods also available: 0.69 (95%CI: 0.58–0.82).

Of the three non-SEER registry studies comparing second rectal cancer risk in irradiated PCa patients and non-irradiated patients, all of which contain fewer patients than the SEER studies, two demonstrate an increase in risk in irradiated patients, in one from 2 months onwards, and in the other beyond 5 years [7,29]. The third non-SEER registry study demonstrated no increase in the risk of second rectal cancer in those irradiated from 30 days [30].

The one single institution study which compared second rectal cancer risk between irradiated and non-irradiated patients, did so in the context of a matched-pair analysis. Patient numbers were smaller than in the above registry studies. No increase in risk in irradiated PCa patients was observed, both when considering risk from early on in the follow-up period, and after longer time periods [13]. Similarly, results of the PLCO trial found irradiated PCa patients to be at no increased risk of second colorectal cancers beyond 30 days compared to non-irradiated patients [12].

Two studies report crude rates of rectal cancer in irradiated PCa patients without comparison to other population groups. Crude rates of 2.6% after a median follow-up of 13.1 years are reported in one series, and of 1.8% after a median follow-up of 3.5 years in another [16,17] (Supplementary Material Table 1).

Clearly there are discrepancies between studies. There is a suggestion, however, that where an increased risk of rectal cancer is observed, this is mainly when follow-up beyond 5 or 10 years is included in the evaluated time period. Beyond 5 years, cancers may be considered radiation induced [6,22–26,28,29]. Trials with shorter durations of follow-up, or few patients with follow-up beyond 5 or 10 years, therefore may not detect all the second rectal cancers that develop and therefore underestimate the true rate. Indeed, the study by Rapiti et al. demonstrated that the median time to colorectal cancer was 8.8 years, while median follow-up was only 7.4 years for all patients, which was therefore insufficient to detect all second colorectal cancers [8]. One study revealed an increase in rectal cancer within 1 year of follow-up but not beyond [15]. This could be attributed to surveillance bias, whereby patients with rectal symptoms following RT are investigated and incidental rectal cancers are detected [15].

The increased risk of second rectal cancer is more consistently observed when irradiated PCa patients are compared to non-irradiated patients, as opposed to when irradiated patients are compared to the general population, again highlighting that there are differences between comparator groups. Differences in length of follow-up between treatment groups may contribute to these discrepancies. Since the risk of developing SPC increases with time, failure to adequately correct for duration of follow-up, may result in inaccurate conclusions. This particular criticism was levelled at Moon et al. (who demonstrated an increased risk of second rectal cancer in irradiated patients compared to non-irradiated PCa patients) by Kendal et al. (who, after correcting for duration of follow-up, demonstrated no increase in risk in irradiated patients) [26,27]. Subsequent studies which have also adjusted for length of follow-up, however, have demonstrated an increase in rectal cancer risk compared to non-irradiated patients and the general population [10,11,22,23,29].

Another important factor is selection bias: although detailed information from registries is generally not available, it is possible that surgically treated patients as a whole have less co-morbidity than patients treated with radiotherapy. These patients may also have fewer risk factors for rectal cancer. Age also impacts on the risk of rectal SPC [25,28], and the majority of the studies have tried to adjust for this [5–8,14,21–30]. Indeed, de Gonzalez et al. demonstrated that the risk of developing a second cancer within a region irradiated to high dose (>5 Gy, includes the rectum and bladder) lessened with an increasing age at diagnosis of PCa, to become non-significant for patients diagnosed with PCa aged 75 years or greater [29].

In terms of absolute risks, Baxter et al. reported the risk of second rectal cancer over 10 years (from 5 to 15 years) as 5.1 per 1000 for surgically treated patients and 10 per 1000 for patients treated with radiotherapy [25]. Over a median of 10 years (beginning from 6 months of PCa diagnosis), Margel et al. calculated a similar absolute risk of 13 per 1000 in irradiated patients [24].

Second bladder cancer risk associated with EBRT for prostate cancer

All four SEER studies which compared the risk of bladder cancer in irradiated PCa patients with the general population (Table 3) report increased risk in irradiated patients, albeit over different periods of follow-up: three report increased risk beginning from early in the follow-up period and, where examined, persisting beyond 5 and 10 years [5,6,22], while one study reports increased risk beginning after 8 years, and not before[21]. The two non-SEER registries comparing risk of second bladder cancer in irradiated patients compared to the general population report no difference in risk within 5 years, beyond 5 years and beyond 10 years of follow-up, although the study by Rapiti is relatively small [7,8]. Amongst the four single institution studies comparing risk in irradiated patients with the general population, two show no increase in the risk of bladder cancer in irradiated patients over all the follow-up periods examined (including 10–19 years in one study) [9,31]. Of the other two institutional studies, one demonstrated increased risk within 1 year of follow-up, but no increase in risk beyond this period [15], and the other showed increased risk beyond 6 months [32].

All but one of the 11 registry studies which compare the risk of second bladder cancer with non-irradiated PCa patients, show a consistently increased risk of second bladder cancer [5,6,10,11,22,26,27,29,30,33] (Table 4). The increased risk is often seen from early on in the follow-up period and frequently persists beyond 5 and, if assessed, beyond 10 years. The one study which demonstrates no increased risk is that by Pickles et al. who examined risk from 2 months and did not specifically examine longer time periods [7].

Of the three single institution studies comparing the risk of second bladder cancer in irradiated PCa patients compared to non-irradiated PCa patients, two show no difference in risk from early in the follow-up period [14,32], while the remaining study shows increased risk in irradiated patients over all durations of follow-up and beyond 5 and beyond 10 years [13] (Table 4). Results for irradiated PCa patients from the PLCO trial suggest no difference in the risk of second bladder cancer beyond 30 days in irradiated and non-irradiated patients [12].

In terms of single institution studies reporting crude rates of second bladder cancers (Supplementary Material Table 1), Zilli et al. reported a crude rate of 1.1% in a series of 276 patients with median follow-up of 42.3 months, and Gardner et al. reported no cases of bladder cancer in a series of 39 patients followed up for a median of 13.1 years [16,17]. In both studies, risk comparisons were not performed.

Overall therefore, there does appear to be an increase in the risk of second bladder cancer in irradiated PCa patients, particularly when compared to non-irradiated PCa patients. As was observed when considering second rectal cancer, the increased risk of second bladder cancer from irradiation is less consistently observed when comparisons are made with the general population. In the case of institutional data, small patient numbers may be the reason for this. Amongst registry data, there may be fundamental differences in comparator populations, duration of follow-up or how adequately differences in follow-up are corrected. Under-reporting may also be a problem in registry data. Selection bias between surgical and irradiated patients may also have an impact. Of great importance when considering bladder cancer, is smoking history and the potential confounding impact this may have. If more smokers are refused surgery due to co-morbidities, then there will be excess smokers in irradiated patient cohorts. Registry data frequently do not contain information regarding smoking status. By comparing the proportion of smokers amongst PCa patients treated with surgery and RT in an earlier case-control trial, Brenner et al. suggested that it was unlikely there were excess smokers in the irradiated patient cohort examined, and therefore concluded that smoking was unlikely to be a confounding factor [6]. The CAPSURE disease registry, however, contains data about smoking, and Bhojani et al. used this to demonstrate that both smoking and irradiation were independent risk factors for second bladder cancer and that patients treated with RT who were also smokers were more than three and a half times more likely to develop bladder cancer than non-smoking patients who did not receive RT (hazard ratio (HR): 3.65; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.45–9.16; [29]).

The increased risk of bladder cancer frequently appears to begin within 5 years of follow-up in the above studies and so radiation is not the likely cause of these early bladder tumours. Surveillance bias, as a result of regular oncological or urological follow-up may play a part in this, while the impact of smoking may also be involved in early (i.e. less than 5 years from RT) and late (i.e. beyond 5 years of RT) bladder cancer development. Beyond 5 years the risk of bladder cancer appears to increase further, and radiation may be attributed to this although the factors mentioned above should also be considered.

Impact of treatment technique: older treatments

The studies discussed above have evaluated SPC incidences in cohorts where all patients, or the vast majority of patients, received EBRT. Many of the SEER analyses have included patients treated in the 1970s and early 1980s when large pelvic fields and cobalt machines were often employed [5,6,10,11,21,23,25,26,28]. SPC risks from these treatments may therefore be different to those observed with more contemporary techniques. Some studies have adjusted for the year or era of diagnosis to try to take different treatment techniques into consideration although date of treatment did not appear to impact SPC risk [22,23,25].

Impact of treatment technique: 3D-conformal radiotherapy and IMRT

It is not possible to separate the impact of more conformal EBRT techniques and older large field treatments from most studies. Initial indications of potential reductions in SPC risk with more contemporary treatment techniques were demonstrated by Rapiti et al., who found a reduction in colorectal cancer incidence in patients irradiated to higher doses (68–80 Gy) compared to those treated to less than 67 Gy (RR: 0.2; 95% CI: 0.04–0.91 [8]). This reduction in risk was attributed to the introduction of smaller volume conformal radiotherapy techniques which accompanied dose escalation. Significance was lost, however, after adjustment for socio-economic status [8]. In addition, the study by Pickles et al., which excluded patients treated with cobalt and included fewer patients treated with large pelvic fields, found no increase in the incidence of SPC overall in irradiated patients compared to the general population [7]. The group suggested that it was the increased use of smaller fields that resulted in no difference in bladder SPC or SPC overall, although a significant increase in colorectal tumours was observed over all durations of follow-up (though not beyond 5 and beyond 10 years specifically) [7]. Two other studies also evaluated SPC in more contemporary irradiated populations, however, and these have demonstrated increased bladder SPC risk compared to the general population and compared to non-irradiated patients [22,30]. One of these studies also revealed an increase in rectal cancer beyond 5 years in irradiated patients compared to non-irradiated patients [22].

Huang et al. was the first institutional study to specifically evaluate differences in EBRT treatment technique [13] (Supplementary Material Table 3). Using a matched-pair analysis comparing irradiated and surgically treated patients in an effort to minimise confounding factors, they demonstrated that patients treated with 2D conventional RT were at increased risk of any SPC (HR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.32–2.35) and bladder cancers (HR: 2.97; 95% CI: 1.50–5.89). There were no differences in the risk of rectal cancer. In contrast, patients treated with 3D-CRT or intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), had no increase in the incidence of SPCs overall, nor in rectal or bladder cancer. The group acknowledged that the numbers of patients in each RT subset was relatively small (769 in the 2D conventional RT subset and 616 in 3D-CRT/IMRT) and that the median follow-up in the 3D-CRT/IMRT group was relatively short (4.96 years) in comparison to the 2D conventional RT group (9.26 years) [13]. Unfortunately numbers were too small to analyse SPC in patients treated with 3D-CRT and IMRT separately. Some radiotherapy planning studies, however, have raised theoretical concerns that increased low dose irradiation and leakage (because of increased monitor unit requirements) with IMRT might increase SPC incidence [1,34–39].

Zelefsky reported outcomes for a series of 897 patients treated predominantly with IMRT [40]. After median follow-up of 7 years, compared to the general population (and excluding non-melanoma skin cancers), there was no significant increase in the development of any second malignancy beyond 1 and 5 years [40] (Supplementary Material Table 3). Similarly, compared with the general population (again excluding non-melanoma skin cancers), there was no significant increase in risk of second in-field and out-of-field malignancies beyond 1 and 5 years. Within the analysis the group also compared the risk of any second malignancy between patients receiving IMRT (the majority) and 3D-CRT (number of patients not reported), and no significant difference was found (p = 0.59) [40].

In a second publication, including the same irradiated patient population with slightly longer follow-up (7.5 years) Zelefsky et al. compared SPC risks with 1348 patients treated with radical prostatectomy (median FU 9.4 years) and 413 patients treated with BT (median follow-up 7.7 years) [41]. There was no significant difference in the rates of second rectal or bladder cancer with treatment type (10 year actuarial likelihood of pelvic second malignancy: 3%, 4% and 2% for patients treated with surgery, EBRT and BT, p = 0.29). Multivariate Cox regression revealed that only age and smoking history were significant predictors of SPC, while treatment type (i.e. surgery, BT or EBRT) was not [41]. Survival following the diagnosis of a second malignancy was no different between irradiated and surgically treated patients [41].

Impact of treatment technique: Brachytherapy

Since the introduction of prostate BT, studies examining the impact of BT on SPC have been published. Four studies have compared SPC incidence after BT with the general population [22,40,42,43] (Table 5). Two of these studies have examined the risk of any SPC compared to the general population, and neither have shown any increase in risk in patients treated with BT, including when follow-up beyond 5 years is examined specifically [40,42]. The risk of rectal cancer has also been shown to be no greater than that in the general population over various time points, including beyond 5 years [22,42]. In terms of bladder cancer, Liauw et al. demonstrated more than double an increase in bladder cancer in patients treated with BT or EBRT–BT over all durations of follow-up compared to the general population. The risk was maintained over longer periods of follow-up (and was equivalent to an absolute excess risk of 35 per 10,000), but did not reach statistical significance [43]. Similarly, Nieder et al. found patients treated with EBRT–BT to be at increased risk of second bladder cancer beyond 6 months, while patients treated with BT monotherapy were not at any increased risk [22]. Hinnen et al. found an increased risk of second bladder cancer in years 1–4 of follow-up but not when considering all durations of follow-up, nor between 5 and 15 years. An increase risk in BT patients aged less than 60 was also observed (SIR: 5.84; 95% CI: 2.14–12.71) [42]. In addition, Zelefsky et al. found no difference in the risk of any in-field cancer, which includes rectal and bladder cancers, beyond 1 and beyond 5 years of follow-up [40].

Table 5.

Studies examining second primary cancers at any site, second rectal cancers and second bladder cancers in prostate cancer patients irradiated using brachytherapy compared to general population.

| Study | Type of data | Period | No. patients | Median follow-up (years)† | Exclusions | Time period(s) assessed | Risk of second cancer at any site based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0 (SIR and (95% confidence interval) | Risk of second rectal cancer based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0 (SIR and (95% confidence interval)) | Risk of second bladder cancer based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0 (SIR and (95% confidence interval)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nieder (2008) [22] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1988–2003 | 22,889 BT |

4.1 | <6 months | >6 months | NR | Reduced (0.68 (0.49–0.93)) | No difference (1.10 (0.92–1.31)) |

| Nieder (2008) [22] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1988–2003 | 17,956 EBRT–BT | 4.1 | <6 months | >6 months | NR | No difference (0.86 (0.65–1.14)) | Increased (1.39 (1.19–1.64)) |

| Liauw (2006) [43] | Retrospective, single centre | 1987–1994 | 348 (125 BT, 223 EBRT–BT) | 11.4 BT 10.2 EBRT–BT |

None | All durations | NR | NR | Increased (2.34 (1.26–3.42)) |

| 0–1 years | No difference (0) | ||||||||

| 1.1–5 years | No difference (2.80 (0.73–4.87)) | ||||||||

| 5.1–10 years | No difference (2.33 (0.60–4.06)) | ||||||||

| 10.1–20 years | No difference (2.35 (0.05–4.66)) | ||||||||

| >5 years | No difference (2.34 (0.95–3.72)) | ||||||||

| Hinnen (2011) [42] | Retrospective, single institution | 1989–2005 | 1187 | 7.1 | None | All durations | No difference (0.94 (0.78–1.12)) | No difference (0.90 (0.41–1.72)) | No difference (1.69 (0.98–2.70)) |

| 1–4 years | No difference (1.03 (0.80–1.30)) | No difference (0.41 (0.05–1.48)) | Increased (2.14 (1.03–3.94)) | ||||||

| 5–15 years | No difference (0.78 (0.56–1.04)) | No difference (1.78 (0.71–3.67)) | No difference (0.92 (0.25–2.35)) | ||||||

| Zelefsky (2012) [40] | Retrospective, single institution | 1998–2001 | 413 (322 BT, 91 EBRT (IMRT)–BT) | 7.5 | <1 year | >1 year | No difference (0.821 (0.565–1.124)) | No difference (0.753 (0.276–1.465))⁎ | No difference (0.753 (0.276–1.465))⁎ |

| >5 years | No difference (0.635 (0.304–1.085)) | No difference (0.944 (0.195–2.274))⁎ | No difference (0.944 (0.195–2.274))⁎ | ||||||

NR: not reported, BT: brachytherapy, EBRT-RT: combination external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy, IMRT: intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

If follow-up for each treatment group reported separately, then this is presented.

SIR quoted is for any in-field cancer, which includes rectal and bladder cancers.

Four studies, one registry and three single institution, have compared the incidence of any SPC in patients irradiated with BT or EBRT–BT with non-irradiated PCa patients (Table 6) [10,13,41,42]. Three of the four suggested no increased risk of any SPC following BT or EBRT–BT [13,41,42]. The fourth study, importantly, is the largest to examine SPC in patients managed with BT and specifically examines longer periods of follow-up [10]. On multivariate analysis there was no difference in risk for SPC beyond 1 year for patients treated with BT or EBRT–BT compared to non-irradiated patients (Table 6)[10]. The hazard ratios for ‘late’ SPCs (i.e. SPC developing beyond 5 years) in patients treated with BT alone, however, increased over time (0.721 at 5 years, 0.930 at 7 years and 1.2 at 9 years) but did not reach significance. Similarly, the hazard ratios for patients treated with EBRT–BT increased over time and only became significant at 9 years (HR of 1.317; 95% CI: 1.053–1.647). Amongst patients treated with BT, however, the median time to develop ‘late’ SPC was 6.9 years while the median follow-up amongst BT patients without SPC was only 6.3 years, thus the duration of follow-up was insufficient [10]. With regard to RISPC specifically (defined as those developing after 5 years in any primary pelvic site, including rectal and bladder tumours), no significant difference in risk was observed amongst patients treated with BT or EBRT–BT compared to patients receiving neither surgery nor RT [10] (Table 7).

Table 6.

Studies examining second primary cancers at any site in prostate cancer patients irradiated using brachytherapy compared to non-irradiated prostate cancer patients.

| Study | Type of data | Period | No. patients | Median follow-up (years) | Exclusions | Time period(s) assessed | Risk of second cancer at any site (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk (HR or other where stated (95% confidence interval)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdel-Wahab (2008) [10] | Retrospective, SEER database | 1973–2002 | 10,223 BT 40,733 no RT |

3.3 BT 4.3 no RT |

<1 year | >1 year | No difference | 0.958 (0.869–1.057) |

| 5 years | No difference | 0.721 (0.435–1.197) | ||||||

| 7 years | No difference | 0.930 (0.575–1.504) | ||||||

| 9 years | No difference | 1.200 (0.736–1.956) | ||||||

| Abdel-Wahab (2008) [10] | Retrospective, SEER database | 1973–2002 | 9096 EBRT–BT 40,733 no RT |

3.8 EBRT–BT 4.3 no RT |

<1 year | >1 year | No difference | 1.012 (0.920–1.112) |

| 5 years | No difference | 0.920 (0.699–1.211) | ||||||

| 7 years | No difference | 1.101 (0.910–1.331) | ||||||

| 9 years | Increased | 1.317 (1.053–1.647) | ||||||

| Hinnen (2011) [42] | Retrospective, single institution | 1989–2005 | 1187 BT 701 no RT |

7.1 BT 8.7 no RT |

None | All durations of FU | No difference | 0.87 (0.64–1.18) |

| Huang (2011) [13] | Retrospective, single institution matched-pair analysis | 1984–2005 | 333 BT 333 no RT |

6.67 BT 6.62 no RT |

None | All durations of FU | No difference | 0.53 (0.28–1.01) |

| Huang (2011) [13] | Retrospective, single institution matched-pair analysis | 1984–2005 | 402 EBRT + BT boost 402 no RT |

8.81 EBRT–BT 8.87 no RT |

None | All durations of FU | No difference | 0.83 (0.50–1.38) |

| Zelefsky (2012) [41] | Retrospective, single institution | 1998–2001 | 413 BT (322 BT, 91 EBRT (IMRT)–BT) 1348 no RT |

7.7 BT 9.4 no RT |

None | 0–10 years | No difference | 10 year second cancer actuarial likelihood BT vs. surgery: 13% vs. 11% (p = 0.37) HR non-significant on multivariate analysis |

HR: hazard ratio, BT: brachytherapy, EBRT–BT: combination external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy, IMRT: intensity-modulated radiotherapy, NS: not significant, NR: not reported.

Table 7.

Studies examining second rectal and bladder cancers in prostate cancer patients irradiated using brachytherapy compared to non-irradiated prostate cancer patients.

| Study | Type of data | Period | No. patients | Median follow-up¥ (years) | Exclusions | Time period(s) assessed | Risk of second rectal cancer (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk of second rectal cancer (RR or other where stated, 95% CI or p value if available) | Risk of second bladder cancer (based on p < 0.05 or confidence interval not including 1.0) | Magnitude of risk of second bladder cancer (RR or other where stated, 95% CI or p value if available) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moon (2006) [26] | Retrospective, SEER database | 1973–1999 | 1285 BT 94,541 no RT |

10 | <5 years | >5 years | No difference | OR: 0.3 (NS⁎) | No difference | OR: 1.4 (NS⁎) |

| Moon (2006) [26] | Retrospective, SEER database | 1973–1999 | 2219 EBRT–BT 94,541 no RT |

10 | <5 years | >5 years | No difference | OR: 1.59 (NS⁎) | No difference | OR: 1.08 (NS⁎) |

| Abdel-Wahab (2008) [10] | Retrospective, SEER database | 1973–2002 | 10,223 BT 40,733 no RT |

3.3 RT 4.3 no RT |

<1 year | 1–4.9 years | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.01% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.01% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ |

| ⩾5 years | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.17% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.17% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ | ||||||

| Abdel-Wahab (2008) [10] | Retrospective, SEER database | 1973–2002 | 9096 EBRT–BT 40,733 no RT |

3.8 RT 4.3 no RT |

<1 year | 1–4.9 years | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.09% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.09% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ |

| ⩾5 years | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.05% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ | No difference⁎⁎ | 0.05% difference in risk (NS)⁎⁎ | ||||||

| Nieder (2008) [22] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1988–2003 | 22,889 BT 109,178 no RT |

4.1 | 6 months | >6 months | No difference | HR: 1.08 (0.77–1.54) | Increased | HR: 1.52 (1.24–1.87) |

| 6 months–5 years | No difference | HR: 0.96 (0.63–1.44) | Increased | HR: 1.48 (1.17–1.86) | ||||||

| 5–10 years | No difference | HR: 1.49 (0.75–2.94) | Increased | HR: 1.64 (1.03–2.62) | ||||||

| >10 years | No difference | HR: 1.13 (0.15–8.42) | No difference | HR: 0.47 (0.06–3.38) | ||||||

| Nieder (2008) [22] | Retrospective, SEER registry | 1988–2003 | 17,956 EBRT–BT 109,178 no RT |

4.1 | 6 months | >6 months | No difference | HR: 1.21 (0.89–1.65) | Increased | HR: 1.85 (1.54–2.22) |

| 6 months–5 years | No difference | HR: 1.05 (0.71–1.55) | Increased | HR: 1.81 (1.46–2.25) | ||||||

| 5–10 years | No difference | HR: 1.26 (0.69–2.29) | Increased | HR: 1.80 (1.22–2.67) | ||||||

| >10 years | Increased | HR: 3.25 (1.25–8.44) | No difference | HR: 1.64 (0.75–3.59) | ||||||

| Hinnen (2011) [42] | Retrospective, single institution | 1989–2005 | 1187 BT 701 no RT |

7.1 BT 8.7 no RT |

None | All durations of FU | No difference† | HR: 0.96(p = 0.92)† | No difference§ | HR: 1.13 (p = 0.75)§ |

| Huang (2011) [13] | Retrospective, single institution matched-pair analysis | 1984–2005 | 333 BT 333 no RT |

6.67 BT 6.62 no RT |

None | All durations of FU | No difference | HR: NR (too few events to analyse), p = 0.32 | No difference | HR: 0.66 (0.11–3.95) |

| Huang (2011) [13] | Retrospective, single institution matched-pair analysis | 1984–2005 | 402 EBRT + BT boost 402 no RT |

8.81 EBRT–BT 8.87 no RT |

None | All durations of FU | No difference | HR: 1.00 (0.14–7.06) | No difference | HR: 2.98 (0.31–28.7) |

| Zelefsky (2012) [41] | Retrospective, single institution | 1998–2001 | 413 BT (322 BT, 91 EBRT (IMRT)–BT) 1348 no RT |

7.7 BT 9.4 no RT |

None | 0–10 years | No difference‡ | 10 year actuarial risk BT vs. surgery: 2% vs. 3% (NS)‡ | No difference‡ | 10 year actuarial risk BT vs. surgery: 2% vs. 3% (NS)‡ |

OR: odds ratio, NS: not significant, NR: Not reported, HR: hazard ratio, RR: relative risk, CI: confidence interval, BT: brachytherapy, EBRT–BT: combination external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy, IMRT: intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

No p value or confidence interval reported.

Difference in any ‘primary’ pelvic second primary cancer (includes rectum and bladder) based on comparisons of age-adjusted estimates and not on multivariate Cox regression, as was used for data in previous tables.

Risk of second cancer in any location in digestive tract.

Risk of any second pelvic tumour reported.

If follow-up for each treatment group reported separately, then this is presented.

Risk of second cancer in urinary tract.

All studies, with one exception, which compare the risk of second rectal or second bladder cancer (Table 7) in patients managed with BT or EBRT-RT with non-irradiated PCa patients do not demonstrate an increased risk in patients managed with BT or EBRT–BT [10,13,26,41,42]. The time periods examined are variable, but follow-up beyond 5 years is examined in two of these studies [10,26]. The one exception is the study by Nieder et al., the largest study and the only one to specifically examine risk beyond 10 years. Patients treated with EBRT–BT were found to be at increased risk of second rectal cancer beyond 10 years (patients treated with BT monotherapy were at no increased risk). In addition, patients treated with BT or EBRT–BT were at increased risk of second bladder cancer from 6 months, between 6 months and 5 years and between 5 and 10 years [22]. Significance was lost beyond 10 years although fewer patients were followed up for this length of time.

Three studies have compared patients treated with BT with patients treated with EBRT (Supplementary Material Table 4) [10,41,44]. None of these have shown PCa patients irradiated with BT or EBRT–BT to be at increased risk of any SPC, nor was any increase in the risk of pelvic/primary pelvic SPCs observed (in the two studies which assessed this). While these results are encouraging overall, it should be remembered that the patient numbers are often lower than in similar studies which have examined risks in EBRT patients, and the duration of follow-up may not always be sufficient.

Gutman et al. examined the frequency of colorectal cancers before and after BT or EBRT–BT [45] (Supplementary Material Table 5). After a median follow-up of 4.6 years, no differences in the frequency of colorectal cancers were observed, nor were there any differences in the geographical location of second colorectal primaries. In addition, the addition of supplemental EBRT (i.e. EBRT–BT) did not increase the risk of colorectal cancer compared to using BT alone [45].

Of the 8 single institution studies examining SPC following BT without comparisons to other population groups (Supplemetary Material Table 5), crude rates range from 0% for any SPC, bladder and rectal cancer up to 11.1%, 5.5% and 10.4% for any SPC, second rectal and second bladder cancers respectively [45–52]. It is likely that some studies have insufficient follow-up to detect all SPCs and that other single institution studies contain a relatively small number of patients. The age of the patient population may also have an impact. For example, Yagi et al. reported no cases of SPC in patients aged less than 60 but a crude rate of 7.6% in patients aged over 60, after median follow-up of 4.3 years [50].

Studies examining survival following BT suggest that up to 3% of patients may die from SPC following BT or EBRT–BT (crude rates, Supplementary Material Table 2) [51,53,54]. The cumulative hazard of death due to a SPC was found to be 7.2% in one study of 1354 patients treated with either BT or EBRT–BT after 12 years [53]. In another series, based on competing analysis to take into account other causes of death, the 10 year risks of death from second malignancy following BT was 0.8% for out-of-field SPC and 0% for in-field SPC in a series of 413 patients [41]. In patients who developed SPC, the risk of mortality from SPC was no different between patients treated with BT or EBRT (or surgery) [41].

Overall, evidence from patients treated with BT or EBRT–BT is encouraging, and is less suggestive of an increased risk of SPCs as has been observed in studies evaluating patients treated with EBRT. Three studies have suggested an increase in bladder cancer beginning in the first few years of follow-up, which could be at least partly attributed to surveillance bias [22,42,43]. Importantly, there is a suggestion from two of the largest cohorts, that the risk of a SPC, although low, may increase with time and so it is likely that follow-up in general has been insufficient to detect all potential late increases in SPC incidence [10,22].

Impact of treatment technique: Proton therapy

Only one study was identified which reported SPC rates in patients treated with proton therapy for PCa [16]. Treatment consisted of a photon four field box to 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions followed by a 27 Gy conformal perineal proton boost. After a median follow-up of 13.1 years, 1 of the 39 patients (2.6%) developed rectal cancer [16]. Clearly no comparisons to other populations have been performed and this series is too small to draw any firm conclusions. Furthermore, the relative contribution of the EBRT and proton components cannot be assessed. Larger numbers of patients treated with proton monotherapy will be required before any conclusion can be drawn regarding the impact of proton therapy on SPC incidence in PCa patients.

Post-operative radiotherapy

Five studies using registry data have examined SPC risk in patients treated with post-operative RT (PORT) following prostatectomy [30,31,33,55,56] (Supplmentary Material Table 6).

Chrouser et al. included a subset of 184 PCa patients managed with PORT in their registry analysis and compared bladder cancer incidence to the general population [31]. No increased risk of bladder cancer was observed in patients receiving PORT over several time points.

Compared to patients treated with radical surgery alone, Abdel-Wahab et al. demonstrated that there was a significantly increased risk of a ‘primary pelvic’ SPC (i.e. tumour likely to arise within the irradiated field: includes rectum, bladder, anus, anal canal, anorectum, prostate, other pelvic soft tissue, bone or joint cancers or pelvic lymphoma) in patients who received PORT beyond 1 year and beyond 5 years of follow-up [55]. There was no increase in the risk of ‘secondary’ pelvic tumours (recto-sigmoid, penis, small intestine (not duodenum), ureter, other urinary primaries, male genital, testes and pelvic lymphoma) or non-pelvic tumours beyond 1 and beyond 5 years [55].

Ciezki et al. used 20-year competing risk regression to compare second rectal and bladder cancers between patients treated with surgery and PORT and those treated with surgery alone [56]. At 20 years, the cumulative incidence of second rectal cancer was 0.74% and 1.06% in patients treated with surgery alone and surgery followed by PORT respectively. The cumulative incidence of second bladder cancer at 20 years was 1.7% and 2.7% in patients treated with surgery alone and surgery plus PORT respectively. Multivariate analysis revealed a significantly increased risk of second rectal and bladder cancers amongst irradiated patients. Older age was also a significant predictor of second bladder cancer (HR: 1.01, p = 0.003) [56].

Singh et al. observed that patients treated with surgery and PORT had an increased risk of second bladder cancers overall as well as beyond 6 months of follow-up (HR: 1.28) compared to patients treated with neither surgery, nor RT [33]. The risk increased beyond 5 years and increased further beyond 10 years of follow-up (HRs: 1.52 and 1.94 respectively). The duration of follow-up in the PORT group was almost twice that in the comparator group (median 93.6 and 48.4 months respectively) and so it is possible that the incidence of bladder cancer was lower in the reference group as a result of insufficient follow-up [33].

In a small subset of patients, Boorjian et al. did not find patients receiving PORT to be at increased risk of second bladder cancer over all time periods assessed compared to patients treated with surgery alone [30].

One series of 214 patients treated with PORT reported death due to second malignancy in 1.9% of patients after median follow-up of 4.8 years (crude rate) [57] while Ciezki et al. reported very low age-adjusted mortality rates from second rectal or bladder cancers [56] (Supplementary Material Table 2).

Compared to PCa patients who do not receive PORT, there is therefore a consistent suggestion of an increased risk of second bladder/rectal cancers following PORT, and this risk appears to increase with time but may also be present early on in the follow-up period. Compared to the general population the same increase in risk is not observed, although the number of patients in this particular analysis was small [31].

Discussion

There is much heterogeneity in the above studies, in terms of methods, comparisons and results, which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Increases in SPC have been observed in irradiated PCa patients in some studies, more so when compared to non-irradiated PCa patients, and less consistently when compared to the general population. The majority of the evidence suggests that the risk of SPC increases over time, particularly for SPCs occurring within the radiation field, and if these occur beyond 5 years they may be considered RISPC.

Solid second primary cancers which occur within 5 years of irradiation are not generally considered RISPCs. Other explanations for an excess of early SPCs must therefore be sought. Surveillance bias is one explanation, as patients presenting with both bladder and bowel symptoms following RT may be investigated and incidental SPCs may be identified. Alternatively, there may be genetic or environmental factors which are common to PCa and other cancers, and therefore patients with PCa are likely to develop other cancers, within 5 years of prostate irradiation or beyond. This is one possible reason for increased cancer rates which have at times been observed when comparing irradiated PCa patients to the general population. If this were the case, then the same increased risk should be observed when comparing non-irradiated PCa patients to the general population. In practice, this is not consistently the case, and non-irradiated PCa patients have been shown to have similar (or even reduced) rates of second malignancy to the general population in terms of cancer overall, and in terms of rectal and bladder cancer specifically [5,6,8,21,24,42]. Surveillance bias is perhaps therefore a better explanation for increased early SPCs in irradiated patients. Beyond 5 years, radiation for in-field SPCs, and genetic or environmental factors for either in-field or out-of-field SPCs, may potentially contribute.

Differences in comparator group are important to consider when evaluating relative SPC risks. As well as the general population, comparisons have been made with non-irradiated PCa patients. This patient group might consist of surgically treated patients, PCa patients treated with neither surgery nor RT, or a mixture of surgically treated patients and patients treated with neither surgery, nor RT. Although we did not analyse differences between these non-irradiated groups in detail, it should not be assumed that any of these PCa patients are pure surrogates for the general population or that they are equivalent to each other. While all these non-irradiated patients have PCa, and therefore common factors contributing to this, there are likely variations in genetic or environmental factors in each of these patient groups that may contribute to or reduce the risk of other cancers.

If the non-irradiated comparator group consists of purely surgically treated patients, selection bias may contribute to differences in SPC risk between surgically treated and irradiated patients. Patients who are fit enough to undergo an operation may have fundamental differences to patients who are only deemed well enough to undergo radiotherapy, and as such surgically treated patients may lack risk factors for certain SPCs.

If the non-irradiated comparator group is patients treated with neither surgery nor RT, many of these patients may have significant co-morbidities which render them unfit for either definitive treatment. Again, this population of patients will have different risk of SPC to PCa patients overall. Furthermore, these patients may not be as thoroughly followed up or investigated for possible second malignancy compared to fitter healthier patients, thus creating additional bias in comparisons and under-reporting of SPC rates.

When the non-irradiated comparator group is a mixture of surgically treated patients as well as those who receive no definitive therapy, a mixed population is potentially created, consisting of surgically fit patients and patients unfit for any definitive therapy, leading to further difficulties in making non-biased comparisons.

It has been suggested that comparing irradiated patients to surgically treated patients results in fewer confounding factors than comparisons to the general population or other non-irradiated PCa patients [13]. Certainly, in clinical practice, if patients are fit enough to consider surgery or RT, then it can be argued that this is the most relevant comparison.

The length of follow-up between comparator groups is also important, and where this is insufficient in any group and not adequately corrected for, reported outcomes may be inaccurate in that group.

Smoking is an important potential confounding factor, especially when considering bladder and lung cancer. As discussed above, smokers may be refused surgery and therefore cohorts of patients treated with radiotherapy may contain a higher proportion of smokers, which in turn will increase the risk of SPCs. PCa patients treated with radiotherapy may also be older than surgically treated patients and this too may have an impact on risks of SPC. Indeed, age at PCa diagnosis has been shown to be another important factor: increasing age has been associated with a reduced risk of second cancers within high dose (>5 Gy) regions [11], while increasing age has been shown to be a significant predictor of bladder SPC [30,33]. Most studies have adjusted for age when calculating risks [5–8,10–14,21–33,40–42,55,56]. Similarly most studies have adjusted for race and grade of tumour. It is possible that other confounding factors exist which are more common in irradiated than non-irradiated PCa patients, and these may also contribute to SPC risk within or beyond 5 years.

A recently identified potential confounding factor is visceral adiposity [17]. Zilli et al. intended to investigate the impact of total abdominal adiposity on clinical and pathological PCa features [17]. Incidentally they observed that increased visceral adiposity was an independent significant predictor of SPCs (HR: 1.014; p = 0.0001).

While many of the studies have included patients treated with now out of date techniques, the registry studies by Neider et al., and Boorjian et al. which included patients from 1988 to 2003, are considered more contemporary EBRT populations, and so the risks observed in these studies may be considered more relevant to today’s PCa patients [22,30]. It is worth noting, therefore, that both of these studies found the risk of bladder cancer to be increased in irradiated patients [22,30], and one demonstrated an increased risk of rectal cancer as well [22]. Insufficient follow-up (median 3.3 years) may explain the absence of increased rectal cancer risk from EBRT in the other of these studies [30].

Studies including patients from the 1970s and early 1980s would have included patients diagnosed before the routine use of PSA. As such a greater proportion of patients would be diagnosed with locally advanced disease and as such would have inferior survival compared to patients in today’s society where many more patients are diagnosed at an earlier stage. A significant proportion of patients from the past may therefore have died prior to developing SPC, and so the relative risks of SPC reported from these studies may actually be lower than what would be expected from modern day PCa patients [22].

With the advent of more conformal treatments, it was hoped that SPC risk might reduce, although the clinical evidence to support this is based on limited evidence from only two relatively small populations irradiated with IMRT/3D-CRT [13,40,41] and on extrapolated evidence from two other studies [7,8]. Longer follow-up and larger numbers of patients will be required. Studies examining the impact of BT or EBRT–BT on SPC risk appear promising, although, once again, longer follow-up will be required before definitive conclusions can be drawn.

Conclusions

Given the multiple factors involved, and heterogeneity among studies, it is very difficult to tease out definitive answers regarding irradiation and the risk of SPCs. Putting all the potential confounders and biases aside, however, it must be acknowledged that a small increased risk of SPC and RISPC in irradiated PCa patients has been observed in several studies. The risk of RISPC appears small, in the range of 1 in 220 to 1 in 290 over all durations of follow-up, based on older radiation techniques. Importantly, the risk appears to increase with time, and beyond 5 years, SPCs in the region of the original field may be considered RISPCs. To date there are insufficient clinical data to draw firm conclusions about the impact of more modern RT techniques, although limited evidence is encouraging. As PCa survival improves, the risk of second malignancy becomes more relevant, especially when treating younger patients. Second primary cancer risks must therefore be borne in mind when considering which patients to irradiate and which techniques to employ.

Acknowledgment

Dr Louise Murray is a Cancer Research UK Clinical Research Fellow (Grant number: C37059/A11941).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References