Abstract

Psychopaths show a reduced ability to recognize emotion facial expressions, which may disturb the interpersonal relationship development and successful social adaptation. Behavioral hypotheses point toward an association between emotion recognition deficits in psychopathy and amygdala dysfunction. Our prediction was that amygdala dysfunction would combine deficient activation with disturbances in functional connectivity with cortical regions of the face-processing network. Twenty-two psychopaths and 22 control subjects were assessed and functional magnetic resonance maps were generated to identify both brain activation and task-induced functional connectivity using psychophysiological interaction analysis during an emotional face-matching task. Results showed significant amygdala activation in control subjects only, but differences between study groups did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, psychopaths showed significantly increased activation in visual and prefrontal areas, with this latest activation being associated with psychopaths’ affective–interpersonal disturbances. Psychophysiological interaction analyses revealed a reciprocal reduction in functional connectivity between the left amygdala and visual and prefrontal cortices. Our results suggest that emotional stimulation may evoke a relevant cortical response in psychopaths, but a disruption in the processing of emotional faces exists involving the reciprocal functional interaction between the amygdala and neocortex, consistent with the notion of a failure to integrate emotion into cognition in psychopathic individuals.

Keywords: psychopathy, face recognition, fMRI, functional connectivity, amygdala

INTRODUCTION

Psychopathy is characterized by the presence of callous and unemotional personality traits (Hare, 2003). The apparent emotional insensitivity of psychopaths is thought to be closely related to a reduced ability to discriminate affective cues in others, which in turn may disturb the normal development of interpersonal relationships and successful social adaptation (Blair and Coles, 2000; Blair, 2006; Corden et al., 2006).

There is strong evidence to suggest that the recognition of fearful and sad emotional facial expressions is impaired in psychopathy (Blair and Coles, 2000; Blair et al., 2001; Stevens et al., 2001; Montagne et al., 2005; Dadds et al., 2006; Dolan and Fullam, 2006; Mitchell et al., 2006), while other studies have reported deficits in the recognition of disgust (Kosson et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2008). Although less consistently observed, some studies have also indicated that the perception of faces with a positive emotional valence (e.g. happiness) may be altered in psychopaths (Dolan and Fullam, 2006; Hastings et al., 2008; Pham and Philippot, 2010), which is broadly consistent with other evidence that they show decreased subjective arousal (Eisenbarth et al., 2008) and abnormal brain responses (Deeley et al., 2006) to happy faces, as well as reduced startle reflex inhibition (Levenston et al., 2000) and electrodermal responses (Herpertz et al., 2001) to pleasant stimulation. These studies, taken together with knowledge that fear recognition is generally more difficult than happiness recognition (Elfenbein and Ambady, 2002), suggest that psychopaths may show a general impairment of emotional processing, as opposed to a specific deficit in the processing of negative cues (Cleckley, 1976; Herpertz et al., 2001).

Emotional face processing involves a distributed brain network, including occipital areas, the fusiform gyrus, the amygdala and prefrontal regions (Haxby et al., 2000; Ishai et al., 2005). The activity in the elements of this network is modulated via their well-established reciprocal connections (Pessoa et al., 2002; Fairhall and Ishai, 2007; Pujol et al., 2009). The amygdala is central to emotional face recognition due to its specific role in stimuli saliency detection (Davidson et al., 2000; Adolphs, 2008).

The hypotheses generated from the large body of behavioral data commonly point toward an association between the deficit in facial affect recognition and amygdala dysfunction in antisocial individuals (Marsh and Blair, 2008). In support of this notion, neuroimaging studies have found abnormal amygdala response to fearful facial expressions (Marsh et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2009) in children and adolescents showing callous–unemotional traits. In normal student populations, subjects scoring above average on callous–unemotional traits in the Psychopathy Personality Inventory (Lilienfeld and Andrews, 1996) showed reduced amygdala and medial frontal cortex activation (Gordon et al., 2004; Han et al., 2011) together with increased visual cortex and prefrontal cortex activation (Gordon et al., 2004) during the processing of emotion facial expressions. Despite this evidence, very few imaging studies have been conducted in adult populations that formally satisfy psychopathy criteria (Hare, 2003). One study reported abnormal activity in visual regions in response to fearful and happy faces in criminal psychopaths (Deeley et al., 2006).

There is increasing evidence that brain alterations in psychopathy also involve neural connectivity. We recently identified reduced functional connectivity between frontal and posterior cingulate cortices in criminal psychopaths under resting-state imaging conditions (Pujol et al., 2011). Aberrant functional connectivity of the posterior cingulate cortex has also been identified during an auditory target detection ‘oddball’ task in association with interpersonal and affective symptoms of psychopathy (Juárez et al., 2013). Another study demonstrated abnormal microstructural integrity in the uncinate fasciculus, which is the white matter pathway linking the anterior temporal and amygdala region with the orbitofrontal cortex (Craig et al., 2009). Motzkin et al. (2011) confirmed both reduced structural integrity in the right uncinate fasciculus and reduced functional connectivity of the frontal cortex with both the amygdala and posterior cingulate cortex. Specifically using emotional face stimulation, Marsh et al. (2008) identified reduced functional connectivity between the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex during the processing of fearful expressions in their children and adolescents with callous–unemotional traits.

The primary aim of the current study was to comprehensively examine brain activation and functional connectivity responses in criminal psychopaths when performing a validated emotional face-recognition task (Hariri et al., 2000). This task served to assess implicit processing of general emotional stimulation in psychopaths, including both positive and negative emotional cues. Our hypothesis was that psychopaths would demonstrate a disruption between putative emotional and cognitive components of the face-processing network. Specifically, we predicted that they would demonstrate reduced functional connectivity between the amygdala and the other network key regions. Consistent with prior studies, we also expected decreased activation in limbic regions in psychopaths combined with increased activation of neocortical areas, presumably indicating compensatory neural processes (Levenston et al., 2000; Kiehl et al., 2001; Glenn et al., 2009; Gordon et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2009).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Twenty-two psychopathic men (Hare, 2003) with a documented history of severe criminal offense were assessed and compared with 22 non-offender control subjects. Characteristics of both samples are fully described in Table 1 and in a previous report (Pujol et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study groups

| Mean ± s.d. |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Controls | Psychopaths |

| Age, years (range) | 40.6 ± 9.5 (28–61) | 39.8 ± 9.2 (28–64) |

| Gender, men | 22 | 22 |

| Vocabulary WAIS-III | 10.3 ± 2.3 | 10.9 ± 3.0 |

| Education, years | 10.5 ± 2.3 | 9.0 ± 2.7 |

| Handedness (left/right) | 2/20 | 1/21 |

| PCL-R total | 0.8 ± 1.9 | 27.8 ± 4.5* |

| PCL-R Factor 1 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 12.5 ± 2.2* |

| PCL-R Factor 2 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 4.7* |

| Comorbidities | ||

| DSM-IV-R Axis I diagnosisa | None | None |

| Hamilton Depression Scale score | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 2.1* |

| Hamilton Anxiety Scale score | 0.8 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 3.2 |

| Y-BOCS, total score | 0 ± 0 | 0.5 ± 2.2 |

| DSM-IV-R Axis II diagnosisb | None | None |

| Impulsiveness Scale, total score | 34 ± 15 | 53 ± 23* |

| Sensitivity to punishment | 5.8 ± 4.9 | 8.1 ± 5.5 |

| Sensitivity to reward | 7.1 ± 4.6 | 11.9 ± 5.5* |

*P < 0.01.

aExcept history of substance abuse.

bExcept APD.

APD = antisocial personality disorder; PCL-R = psychopathy checklist-revised; Y-BOCS = Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale.

A total of 105 convicted subjects were initially evaluated using a comprehensive clinical protocol. The sample showed a mean Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) score (Hare, 2003) of 27.8 and served to select individuals for functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) evaluation according to the following criteria (i) total PCL-R score >20 or PCL-R Factor 1 >10, (ii) documented severe criminal offense, (iii) absence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Axis I diagnosis with the exception of past history of substance abuse, (iv) absence of DSM-IV Axis II diagnosis, apart from antisocial personality disorder, (v) absence of symptomatic medical and neurological illness, (vi) normal IQ according to the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition-Revised (WAIS-III-R; Wechsler, 1997) (sample total IQ in mean ± s.d. is 108 ± 14) and (vii) obtaining subject-specific full administrative permissions and special police custody during the fMRI assessment day, which was limited to 23 individuals (valid cases, n = 22).

Psychopathy assessment

Information for rating the PCL-R was collected by a trained senior psychiatrist from a comprehensive semi-structured interview with the inmate and a review of his institutional files and all available additional information. For the PCL-R, each of the 20 items was scored 0, 1 or 2, depending on the degree to which it was exhibited. The Spanish version of PCL-R was used (Hare, 2003). The internal consistency of the assessment was tested for the whole 105-subject sample obtaining a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.79 (inter-item correlation mean = 0.36) for PCL-R total score.

Offense history

All 22 individuals were incarcerated in correctional institutions situated in Catalonia (Spain). The mean (± s.d.) completed incarceration time at inclusion was 88 ± 63 months (range 12–251 months). The mean time of accumulated sentences was 243 ± 127 months (range 96–546 months). All were violent armed offenders. Twenty-one of the individuals had committed violent robberies. Fifteen individuals were convicted murderers. Twelve individuals had a criminal record prior to the age of 15 years. None of them had a sexual offense record.

Substance use/abuse and medical records

Although we sought to recruit a group of relatively ‘pure’ psychopaths, we avoided excessive subject exclusion from associated medical factors in an attempt to maximally provide a generally representative inmate psychopath population. No subject had consumed alcohol (except for one sporadic consumer) or relevant amounts of psychoactive substances for at least 2 months prior to the assessment (verified using drug-urine testing). A total of five individuals showed a history of alcohol abuse and fifteen individuals had been sporadic consumers of alcohol. Sixteen individuals had a history of other psychoactive substance use.

None of the subjects had suffered from any relevant symptomatic medical illness prior to the study. Four individuals showed positive testing for asymptomatic HIV, four additional individuals for asymptomatic hepatitis B virus and three for asymptomatic hepatitis C virus. None of them presented with neurological complications.

The sample of healthy non-offender subjects were recruited from the community matching the psychopathy group by age, sex and scores on the Vocabulary subscale of WAIS-III and also underwent a comprehensive medical and psychiatric assessment (Table 1). All cases and control subjects gave written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study, which was approved by local research and ethics committees (IMIM Hospital del Mar, Barcelona and Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida). The investigation was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Emotional face-matching task

Subjects were assessed using a modified version of the emotional face-matching task originally reported by Hariri et al. (2000). The task was identical to that described in our previous studies (Pujol et al., 2009; Cardoner et al., 2011). Briefly, during each 5 s trial, subjects were presented with a target face (center top) and two probes faces (bottom left and right) and were instructed to match the probe expressing the same emotion to the target by pressing a button in either their left or right hand. An fMRI block consisted of six consecutive trials in which the target face was either happy or fearful, and the probe faces included two out of three possible emotional faces (happy, fearful and angry). As a control condition, subjects were presented with 5 s trials of ovals or circles in an analogous configuration and were instructed to match the shape of the probe to the target.

A total of six 30 s blocks of faces (three happy and three fearful) and six 30 s blocks of the control condition were presented interleaved in a pseudo-randomized order. A fixation cross was interspersed between each block. The paradigm was presented visually on a laptop computer running Presentation Software (http://www.neurobehavioralsystems.com). MRI-compatible high-resolution goggles (VisuaStim Digital System, Resonance Technology Inc., Northridge, CA, USA) were used to display the stimuli. Subjects’ task responses were registered using a right- and a left-hand response device based on optical fiber transmission (NordicNeuroLab Inc., Bergen, Norway).

Image acquisition and preprocessing

A 1.5 T Signa Excite system (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) equipped with an eight-channel phased-array head coil and single-shot echo-planar imaging (EPI) software was used. Functional sequences consisted of gradient recalled acquisition in the steady state [time of repetition (TR) = 2000 ms; time of echo (TE) = 50 ms; pulse angle = 90°] within a field of view of 24 cm, with a 64 × 64 pixel matrix and with a slice thickness of 4 mm (inter-slice gap = 1 mm). Twenty-two interleaved slices, parallel to the anterior–posterior commissure (AC–PC) line, were acquired to cover the whole brain. The sequence first included four additional dummy volumes to allow the magnetization to reach equilibrium.

Imaging data were transferred and processed on a Microsoft Windows platform running MATLAB version 7 (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Image preprocessing was performed in SPM5 (Statistical Parametric Mapping Software, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) and involved motion correction, spatial normalization and smoothing using a Gaussian filter (full-width at half-maximum of 8 mm). Data were normalized to the standard SPM-EPI template and re-sliced to 2 mm isotropic resolution in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. We excluded data from one psychopathic individual and one control from the larger original samples of 23 subjects, because of technical problems during fMRI.

Statistical analyses

Behavioral analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15.0 was used. Behavioral measurements were compared using independent sample Student’s t-test. Task performance was analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance with ‘accuracy’ and ‘reaction time’ (fearful faces, happy faces and shapes) as the within-subject factor and ‘study group’ (controls and psychopaths) as the between-subject factor to assess interactions.

Functional MRI analysis

Main task effects

First-level (single-subject) SPM contrast (.con) images were estimated for the following three tasks effects of interest: all faces > shapes, fear faces > shapes and happy faces > shapes. Four regressors were used in these analyses to model conditions separately corresponding to fearful, happy, shapes and baseline. A hemodynamic delay of 4 s was considered and a high-pass filter was used to remove low-frequency noise (1/128 Hz). The resulting first-level contrast images were then carried forward to subsequent second-level random-effects (group) analyses. One-sample t-test was used to assess the main task effects and two-sample t-test to assess group differences within the network activated by the task (identified with a group conjunction analysis).

Psychophysiological interactions analysis

One established method for characterizing functional connectivity within brain networks in the context of experimental tasks is ‘psychophysiological interaction’ (PPI) analysis (Friston et al., 1997). Using PPI analysis, abnormal functional connectivity between key regions of the ‘face-processing network’ has been characterized in social phobia (Pujol et al., 2009; Danti et al., 2010), autism spectrum disorder (Monk et al., 2010) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (Cardoner et al., 2011).

A series of PPI analyses were carried out in SPM5 (Friston et al., 1997) to assess the influence of task (the ‘psychological factor’) on the strength of functional coupling (‘functional connectivity’) between the amygdala and the emotional face network (voxels activated during task) and between the network (selected regions of interest, ROIs) and the amygdala.

The placement of source ROIs was determined from a global (group-combined) analysis of the ‘all faces > shapes’ contrast. The fMRI signal time course was extracted at peak activation for right (x, y, z: 32, −86, −8) and left (−22, −92, −8) visual cortices; right (40, −54, −22) and left (−40, −56, −26) fusiform gyri; right (28, 0, −26) and left (−22, −2, −26) amygdalae; and right (50, 22, 22) and left (−46, 20, 24) prefrontal cortices. The fMRI signal time course for each selected ROI was obtained using the first eigenvariate value from a 4 mm radial sphere placed on these anatomical coordinates.

As in previous studies (Pujol et al., 2009; Cardoner et al., 2011), a first-level analysis was performed for each subject to map areas where fMRI signal was predicted by the cross-product (PPI interaction term) of the ‘physiological’ (deconvolved time course of the given ROI) and the ‘psychological’ factors (regressors representing the experimental paradigm). Separate models were performed for the contrasts all faces > shapes, fearful faces > shapes and happy faces > shapes. Both the physiological and the psychological factors were included in the final SPM model as confound variables.

First-level individual contrast images were then included in a second-level random-effects (group) analysis to assess task-induced reciprocal functional connectivity between the amygdala and the emotional face network. Amygdala to emotional face network connectivity was masked by task activation map (group conjunction analysis) and network (selected ROIs) to amygdala connectivity by an anatomical mask of the amygdala created with the Wake Forest University (WFU) PickAtlas (Maldjian et al., 2003). Although our primary target was the amygdala, connectivity for each selected ROI was additionally explored within the entire emotional face network (see Supplementary material for further details).

Correlation analysis

Voxel-wise correlation analyses were performed in SPM5 to map the association between psychopathy severity (using total PCL-R scores, Factor 1 and Factor 2 as regressors) and both brain activation and task-induced functional connectivity in the psychopathy group.

Thresholding criteria

Group-level brain activation and task-induced functional connectivity maps were thresholded at PFDR < 0.05, whole-brain corrected. Between-group differences and within-group correlations within the network of interest were considered significant when involving a minimum cluster extension of 200 voxels at P < 0.01, uncorrected.

RESULTS

Behavioral performance

Control subjects and psychopaths showed a similar performance during the emotional face task (Table 2). There was no significant interaction between study group and task condition with regards to task accuracy [F(2,84) = 1.3, P = 0.27] nor a significant main effect of group [F(1,42) = 1.3, P = 0.26]. There was, however, a main effect of task condition [F(2,84) = 4.7, P < 0.01] to which overall accuracy for fearful faces was lower than for happy faces (P = 0.04) and shapes (P = 0.009).

Table 2.

Emotional face task performance [accuracy and reaction time (RT)]

| Conditions | Mean ± s.d. |

t-value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Psychopaths | |||

| Shapes, correct, % | 100 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 | – | – |

| RT (ms) | 874 ± 155 | 886 ± 222 | 0.2 | 0.83 |

| Fearful, correct, % | 99.0 ± 2.78 | 96.5 ± 9.63 | −1.2 | 0.24 |

| RT (ms) | 1831 ± 561 | 1883 ± 482 | 0.3 | 0.75 |

| Happy, correct, % | 100 ± 0 | 99.0 ± 4.74 | −1.0 | 0.32 |

| RT (ms) | 1262 ± 322 | 1341 ± 395 | 0.7 | 0.47 |

There was no significant interaction between study group and task condition with regards to reaction time [F(2,84) = 0.2, P = 0.82] and no significant main effect of group [F(1,42) = 0.2, P = 0.63]. There was a main effect of task condition [F(2,84) = 165.1, P < 0.0001] to which reaction time for fearful face was slower than for both happy faces (P < 0.0001) and shapes (P < 0.0001), and happy faces slower than shapes (P < 0.0001).

Functional MRI

Brain response to emotional faces

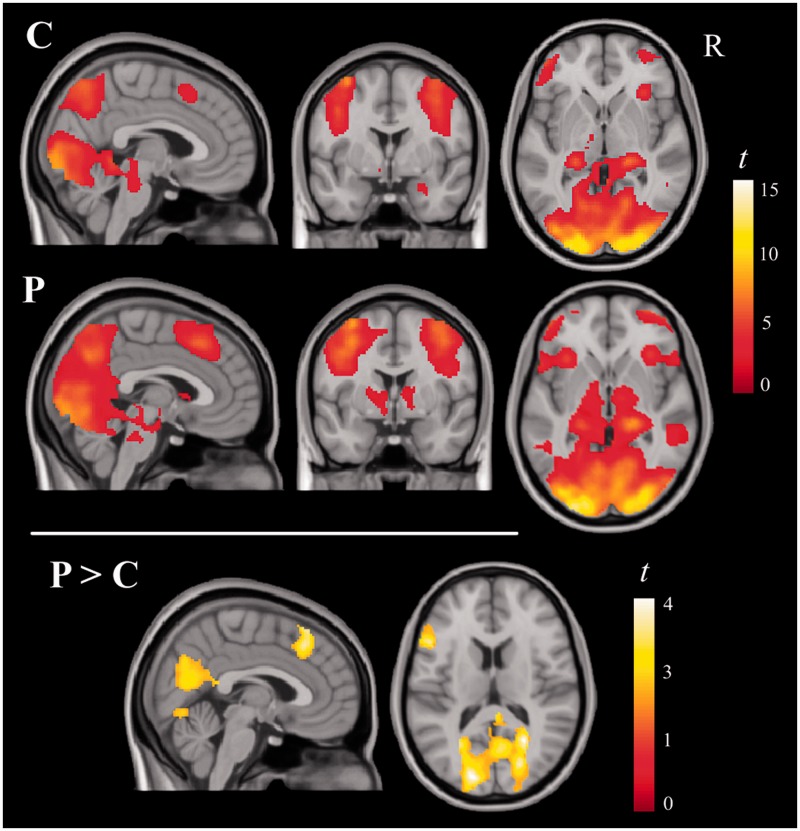

Brain activation for the ‘faces > shapes’ contrast in both groups bilaterally included a large extension of the visual cortex, the fusiform gyrus, the posterior part of the parietal lobe, the hippocampus, superior brainstem, and medial and lateral prefrontal areas. Additional activation was identified in the right amygdala in control subjects, but not in psychopaths. Psychopaths, on the other hand, showed significant activation in the basal ganglia and thalamus. Between-group comparisons showed that relative to control subjects, psychopaths demonstrated significantly greater activation of visual areas, medial frontal cortex and the left prefrontal cortex (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table S1). No brain region showed significantly greater activation in control subjects.

Fig. 1.

Brain regions activated during the emotional face-matching task in the controls (C) and psychopaths (P) subjects and between-group differences (P > C), masked by group conjunction activations.

Separate analyses for the contrasts ‘fearful faces > shapes’ and ‘happy faces > shapes’ showed a brain activation pattern similar to the pattern obtained for the ‘all faces > shapes’ contrast. Between-group comparisons also demonstrated significantly greater activation of visual areas, medial frontal cortex and the left prefrontal cortex in psychopaths relative to control subjects (Supplementary Table S2).

To test post hoc a potential effect of task difficulty on group differences in brain activation, we repeated the analyses for the contrasts ‘fearful faces > shapes’, ‘happy faces > shapes’ and ‘all faces > shapes’ using accuracy and reaction time measurements as covariates. We found comparable results before and after the covariation, which indicates no relevant task difficulty effect.

Functional connectivity (PPI) analysis

With this analysis, we set out to test for group differences in reciprocal functional connectivity between the amygdala and other key components of the emotional face-processing network. We report results for ‘all faces > shapes’ contrast only, as separate analyses for fearful and happy conditions showed amygdala connectivity changes comparable to the global (all faces) pattern.

Functional connectivity between amygdala and emotional face network

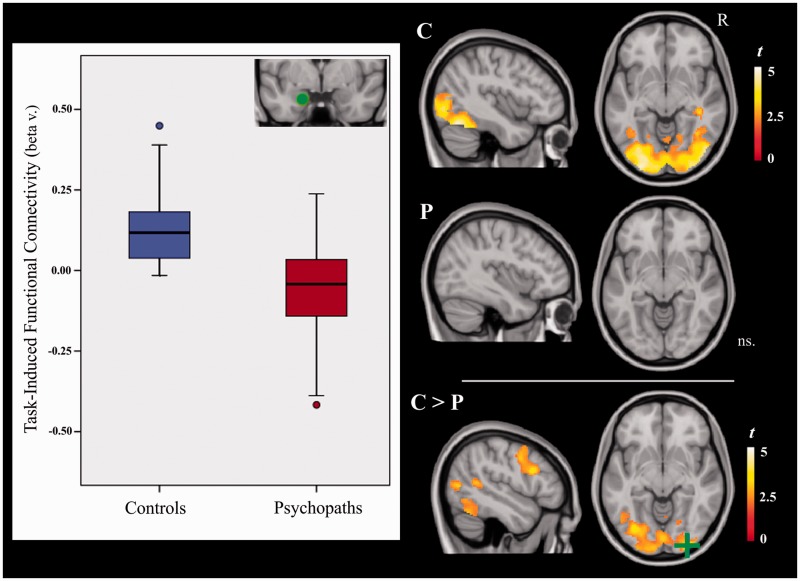

We found consistent task-induced functional connectivity between the left amygdala (seed) and both the visual cortex and left fusiform gyrus only in control subjects (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S3). A between-group comparison confirmed that psychopaths had a significant reduction in functional connectivity between the left amygdala and visual areas, the fusiform gyrus, parietal/frontal cortices and the thalamus (Supplementary Table S4). No significant within- or between-group findings were observed in the right amygdala PPI analysis.

Fig. 2.

Task-induced functional connectivity of the left amygdala in control (C) and psychopathic (P) subjects, and between-group differences (P > C). The boxplots illustrate group mean functional connectivity strength between the left amygdala seed (green spot) and right visual cortex (green cross). R = right hemisphere.

Functional connectivity between network ROIs and amygdala

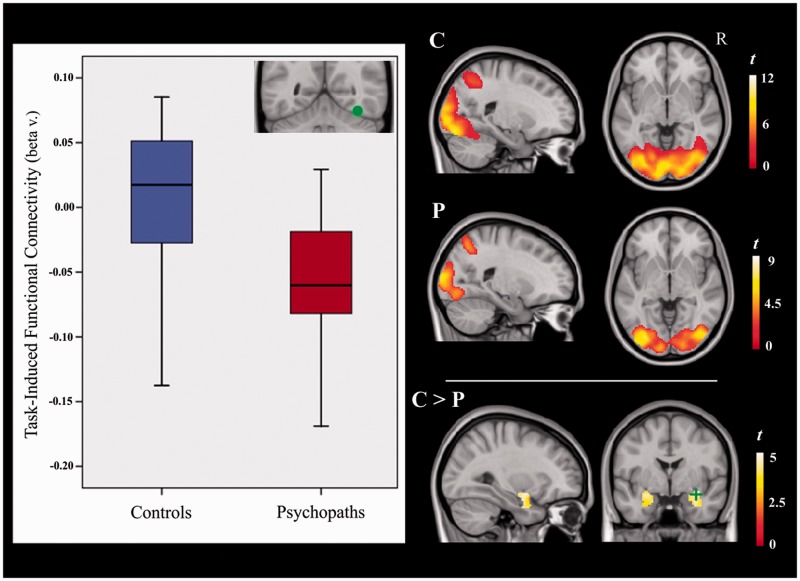

(i) PPI analyses centered on the visual extrastriate regions did not demonstrate significant functional connectivity with the amygdalae. (ii) The fusiform gyri did not show significant task-induced functional connectivity with the amygdalae in any group (no main effects), but between-group differences were significant for the right fusiform gyrus analysis. That is, because control subjects showed a tendency toward increased connectivity between the right fusiform gyrus and amygdalae and psychopaths showed the opposite pattern, there was a significant between-group difference in the functional connectivity of these regions (Figure 3). (iii) Finally, the prefrontal regions also showed no evidence of significant task-induced functional connectivity with the amygdalae.

Fig. 3.

Task-induced functional connectivity between the right fusiform gyrus and the amygdalae in control (C) and psychopathic (P) subjects, and between-group differences (P > C) within a PickAtlas (Maldjian et al., 2003) mask of the amygdala. The boxplots illustrate group mean functional connectivity strength between the right fusiform gyrus seed (green spot) and the right amygdala (green cross). R = right hemisphere.

The complete PPI analyses’ results for the visual extrastriate cortex, fusiform gyrus and prefrontal regions are reported in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

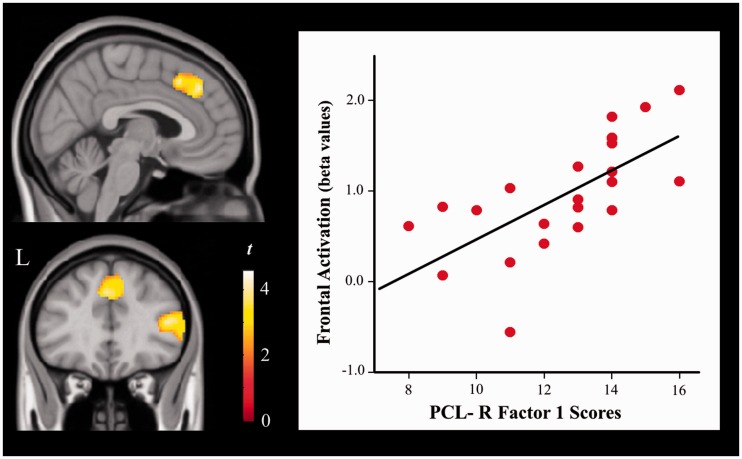

Correlation with the severity of psychopathy

We found a significant positive correlation between PCL-R Factor 1 and frontal cortex activation in the psychopathy group. The anatomy of this finding partially overlapped with areas showing abnormally increased activation in this group (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S5). In contrast, PCL-R Factor 2 was negatively correlated with task activation in frontoparietal cortex, visual areas and diencephalic–mesencephalic structures. The correlation analysis was repeated controlling for total months spent in prison. A similar correlation strength was observed with regards to PCL-R Factor 1 (e.g. r = 0.72 without control vs r = 0.72 controlling for incarceration time in medial prefrontal cortex), but the correlations were no longer significant for PCL-R Factor 2. These results indicate that the severity of the interpersonal and affective deficits (Factor 1), as opposed to antisocial behavior (Factor 2) and incarceration time, accounted for increased frontal activations during emotional face processing. PCL-R total scores were not significantly correlated with task activation measurements.

Fig. 4.

Correlations between PCL-R Factor 1 and task-related activation in psychopaths. The plot illustrates the correlation between psychopathy severity and medial prefrontal cortex activation MNI coordinates (x, y, z: 0, 36, 40 mm).

PCL-R total scores, Factor 1 and Factor 2 were not significantly correlated with task-induced functional connectivity measurements.

DISCUSSION

We have conducted a functional neuroimaging study comparing criminal psychopaths and control subjects during the execution of an emotional face-matching task. While behavioral performance was similar between the two groups, fMRI findings revealed relevant differences suggesting a generally distinct neural processing of this emotional stimulation. On the one hand, psychopaths showed greater activation of neocortical areas involving both visual and prefrontal cortices, whereas they also showed a reciprocal decrease in task-induced functional connectivity between the amygdala and the visual and prefrontal cortices. The observed pattern of results suggests that differences in the neural processing of emotional faces may combine both deficient (limbic) and compensatory (neocortical) operations. Relevantly, further correlation analyses revealed a positive association between PCL-R scores Factor 1 and brain activation in areas mostly related to the putative compensatory processes.

Behavioral studies assessing the recognition of emotional face expressions have generally reported performance deficits in psychopaths and individuals with psychopathic traits (Blair et al., 2001, 2004; Kosson et al., 2002; Dadds et al., 2006; Dolan and Fullam, 2006), which seem to contrast with our current findings. However, it is likely that the discrepancy is explained by the implicit, as opposed to explicit, emotional processing demands of our face matching task. That is, participants in our study were instructed to perceptually match correct face expressions, rather than to explicitly label each emotional expression. Supporting this interpretation, other fMRI studies have generally reported an absence of performance deficits in such populations in the context of implicit emotional face-processing tasks (Deeley et al., 2006; Marsh et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2009).

The explicit component in the current task involves the visual matching of facial features, which notably relies on visual perceptual (neocortical) abilities (Goodale and Milner, 1992). Performance success in the psychopath group may arguably be related to the efficient use of visual and frontal cortex resources. Prior functional imaging studies have reported cortical hyperactivity during other emotional tasks in psychopath cohorts (Intrator et al., 1997; Kiehl et al., 2001; Müller et al., 2003; Glenn et al., 2009), which has been generally interpreted as reflecting compensatory neural operations. Importantly, the implicit component in our task involves an inherent limbic system (hippocampus and amygdala) engagement due to the biological salience of human emotional faces (Hariri et al., 2000). Our findings suggest that this implicit limbic system engagement is disrupted in psychopaths. Amygdala activation during the task was only significant in control subjects, while functional connectivity between the amygdala and cortical regions was significantly reduced in psychopaths. To this end, a relevant question emerges with regards to the context to which emotion brain processing is deficient in psychopaths. According to Newman’s response modulation theory, the neural processing of visual emotional content should be less altered in psychopaths if emotional cues are the central focus of attention (Hiatt et al., 2004; Glass and Newman, 2009; Newman et al., 2010). In other words, the implicit nature of our task may have contributed to emphasize emotional system deficiencies in psychopaths showing an overselective attention (Hiatt et al., 2004).

The visual occipitotemporal cortex and the amygdala are tightly coupled during face perception (Haxby et al., 2000; Fairhall and Ishai, 2007; Smith et al., 2009). Functional connectivity with the fusiform gyrus is strengthened specifically by emotional faces (Fairhall and Ishai, 2007) and modulated by anxiety-related personality traits (i.e. harm avoidance and sensitivity to punishment) and emotional abilities in general (Japee et al., 2009; Pujol et al., 2009), which are known to be blunted in some psychopathic individuals (Cleckley, 1976; Hare, 2003). Overall, our finding of a functional connectivity reduction within the visual-fusiform-amygdala pathway is consistent with the studies reporting reduced affective responses to facial expressions in psychopaths (Patrick et al., 1993; Blair et al., 1997; Levenston et al., 2000; Herpertz et al., 2001; Marsh et al., 2011). More broadly, a disruption of amygdala functional connectivity is consistent with the abundant data suggesting that amygdala alterations contribute prominently to impaired stimulus-reinforcement learning in psychopaths (Kiehl et al., 2001; Birbaumer et al., 2005; Blair, 2006).

Our data, therefore, may assist in further delineating the functional anatomy of disturbed neural processing of emotional stimulation in psychopaths. Importantly, functional connectivity disruption may occur at multiple stages of the normal emotion processing flow. Indeed, the alteration between visual input areas and the amygdala observed in the present study implicates a pathway relevant for the detection of stimulus saliency (Adolphs, 2008). Other studies have previously demonstrated anatomical and functional disruption between the anterior temporal/amygdala region and the orbitofrontal cortex (Marsh et al., 2008; Motzkin et al., 2011). This processing pathway is relevant to signal stimulus reinforcing value (reward expectancies) in the context of associative learning (Schoenbaum et al., 1998, 2003; Baxter et al., 2000). Finally, significantly impaired functional connectivity has also been identified between the medial frontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which are connections relevant to the large-scale integration of the emotional and cognitive components of decision-making in a moral context (Motzkin et al., 2011; Pujol et al., 2011; Juárez et al., 2013).

As mentioned above, this study is limited in that we explored neural processes related mainly to implicit emotional processing and used a task that may better assess the effect of general emotional stimuli than the effect of single emotions, as two different emotional expressions are presented in each trial. Also, the potential effect of incarceration on brain function was not controlled for using an additional control group of non-psychopathic prison inmates. The results of our correlation analysis suggest that subjects’ confinement can indeed modulate the association between antisocial behavior (PCL-R Factor 2) and brain activation. Nevertheless, our findings indicated that the interpersonal and affective traits in psychopaths (PCL-R Factor 1) accounted for cortical activation changes with little influence from the length of the incarceration period.

In conclusion, the neural response to emotional face matching in criminal psychopaths involved an increase in neocortical activation combined with reduced task-related functional connectivity between the cortex and the amygdala. We propose that psychopaths were capable of performing the task similar to control subjects by marshaling greater involvement of neocortical perceptual resources, but that the ultimate input to the limbic system was weakened. Therefore, callous and unemotional psychopaths do appear to exhibit a deficit in the neural processing of emotional stimuli, which is in broad agreement with the notion that psychopaths display low ‘somatic’ emotion. Nevertheless, new research will be of interest to further explore the ‘cognitive’ component of emotional processing in psychopathy to ascertain how their apparent emotional insensitivity translates to various aspects of their subjective experience.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at SCAN online.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the collaboration of the Secretaria de Serveis Penitenciaris, Rehabilitació i Justícia Juvenil and the Centres Penitenciaris de Catalunya. This work was supported in part by the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias de la Seguridad Social of Spain (PI050884 and PI050884), the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación of Spain (SAF2010-19434) and the Departament de Justícia de la Generalitat de Catalunya. Dr Harrison is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Clinical Career Development Award (628509). Dr Soriano-Mas is funded by a ‘Miguel Servet’ contract from the Carlos III Health Institute (CP10/00604). Drs Deus and Lopez-Sola are members of the Research Group SGR-1450 of the Catalonia Government.

REFERENCES

- Adolphs R. Fear, faces, and the human amygdala. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2008;18:166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter MG, Parker A, Lindner CC, Izquierdo AD, Murray EA. Control of response selection by reinforcer value requires interaction of amygdala and orbital prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:4311–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04311.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birbaumer N, Veit R, Lotze M, et al. Deficient fear conditioning in psychopathy: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:799–805. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. The emergence of psychopathy: implications for the neuropsychological approach to developmental disorders. Cognition. 2006;101:414–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Coles M. Expression recognition and behavioural problems in early adolescents. Cognitive Development. 2000;15:421–34. [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Colledge E, Murray L, Mitchell DG. A selective impairment in the processing of sad and fearful expressions in children with psychopathic tendencies. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:491–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1012225108281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Jones L, Clark F, Smith M. The psychopathic individual: a lack of responsiveness to distress cues? Psychophysiology. 1997;34:192–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Mitchell DGV, Peschardt KS, et al. Reduced sensitivity to others’ fearful expressions in psychopathic individuals. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:1111–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoner N, Harrison BJ, Pujol J, et al. Enhanced brain responsiveness during active emotional face processing in obsessive compulsive disorder. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2011;12:349–63. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.559268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley H. The Mask of Sanity. 5th edn. 1976. St Louis: Mosby. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corden B, Critchley HD, Skuse D, Dolan RJ. Fear recognition ability predicts differences in social cognitive and neural functioning in men. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18:889–97. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.6.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig MC, Catani M, Deeley Q, et al. Altered connections on the road to psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:946–53. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Perry Y, Hawes DJ, et al. Attention to the eyes and fear-recognition deficits in child psychopathy. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:280–1. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danti S, Ricciardi E, Gentili C, Gobbini MI, Pietrini P, Guazzelli M. Is social phobia a ‘mis-communication’ disorder? Brain functional connectivity during face perception differs between patients with social phobia and healthy control subjects. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2010;4:152. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation - a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–4. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeley Q, Daly E, Surguladze S, et al. Facial emotion processing in criminal psychopathy. Preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:533–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan M, Fullam R. Face affect recognition deficits in personality-disordered offenders: association with psychopathy. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1563–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth H, Alpers GW, Segrè D, Calogero A, Angrilli A. Categorization and evaluation of emotional faces in psychopathic women. Psychiatry Research. 2008;159:189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein HA, Ambady N. On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:203–35. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairhall SL, Ishai A. Effective connectivity within the distributed cortical network for face perception. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:2400–6. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Buechel C, Fink GR, Morris J, Rolls E, Dolan RJ. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. NeuroImage. 1997;6:218–29. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass SJ, Newman JP. Emotion processing in the criminal psychopath: the role of attention in emotion-facilitated memory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:229–34. doi: 10.1037/a0014866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn AL, Raine A, Schug RA, Young L, Hauser M. Increased DLPFC activity during moral decision making in psychopathy. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:909–11. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale MA, Milner AD. Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends in Neurosciences. 1992;15:20–5. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon HL, Baird AA, End A. Functional differences among those high and low on a trait measure of psychopathy. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:516–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T, Alders GL, Greening SG, Neufeld RW, Mitchell DG. Do fearful eyes activate empathy-related brain regions in individual with callous traits? Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2011;7:958–68. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AL, Johnsen BH, Hart S, Waage L, Thayer JF. Brief communication: psychopathy and recognition of facial expressions of emotion. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22:639–44. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) 2nd edn. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Bookheimer SY, Mazziotta JC. Modulating emotional responses: effects of a neocortical network on the limbic system. NeuroReport. 2000;11:43–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings ME, Tangney JP, Stuewig J. Psychopathy and identification of facial expressions of emotion. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:1474–83. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Hoffman EA, Gobbini MI. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4:223–33. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpertz SC, Werth U, Lukas G, et al. Emotion in criminal offenders with psychopathy and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:737–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt KD, Schmitt WA, Newman JP. Stroop tasks reveal abnormal selective attention among psychopathic offenders. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:50–9. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrator J, Hare R, Stritzke P, et al. A brain imaging (single photon emission computerized tomography) study of semantic and affective processing in psychopaths. Biological Psychiatry. 1997;42:96–103. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishai A, Schmidt CF, Boesiger P. Face perception is mediated by a distributed cortical network. Brain Research Bulletin. 2005;67:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japee S, Crocker L, Carver F, Pessoa L, Ungerleider LG. Individual differences in valence modulation of face-selective M170 response. Emotion. 2009;9:59–69. doi: 10.1037/a0014487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AP, Laurens KR, Herba CM, Barker GJ, Viding E. Amygdala hypoactivity to fearful faces in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:95–102. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juárez M, Kiehl KA, Calhoun VD. Intrinsic limbic and paralimbic networks are associated with criminal psychopathy. Human Brain Mapping. 2013;34(8):1921–30. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl KA, Smith AM, Hare RD, et al. Limbic abnormalities in affective processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:677–84. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Suchy Y, Mayer AR, Libby J. Facial affect recognition in criminal psychopaths. Emotion. 2002;2:398–411. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.2.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenston GK, Patrick CJ, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. The psychopath as observer: emotion and attention in picture processing. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:373–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, Andrews BP. Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal populations. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;66:488–524. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6603_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19:1233–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Blair RJ. Deficits in facial affect recognition among antisocial populations: a meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:454–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Finger EC, Mitchell DG, et al. Reduced amygdala response to fearful expressions in children and adolescents with callous-unemotional traits and disruptive behavior disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:712–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Finger EC, Schechter JC, Jurkowitz IT, Reid ME, Blair RJ. Adolescents with psychopathic traits report reductions in physiological responses to fear. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2011;52:834–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DG, Avny SB, Blair RJ. Divergent patterns of aggressive and neurocognitive characteristics in acquired versus developmental psychopathy. Neurocase. 2006;12:164–78. doi: 10.1080/13554790600611288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Weng SJ, Wiggins JL, et al. Neural circuitry of emotional face processing in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2010;35:105–14. doi: 10.1503/jpn.090085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagne B, van Honk J, Kessels RPC, et al. Reduced efficiency in recognising fear in subjects scoring high on psychopathic personality characteristics. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Motzkin JC, Newman JP, Kiehl KA, Koenigs M. Reduced prefrontal connectivity in psychopathy. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:17348–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4215-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller JL, Sommer M, Wagner V, et al. Abnormalities in emotion processing within cortical and subcortical regions in criminal psychopaths: evidence from a functional magnetic resonance imaging study using pictures with emotional content. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:152–62. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Curtin JJ, Bertsch JD, Baskin-Sommers AR. Attention moderates the fearlessness of psychopathic offenders. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Emotion in the criminal psychopath: startle reflex modulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:82–92. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa L, McKenna M, Gutierrez E, Ungerleider LG. Neural processing of emotional faces requires attention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:11458–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172403899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TH, Philippot P. Decoding of facial expression of emotion in criminal psychopaths. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2010;24:445–59. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J, Batalla I, Contreras-Rodríguez O, et al. Breakdown in the brain network subserving moral judgement in criminal psychopathy. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2011;7:917–23. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J, Harrison BJ, Ortiz H, et al. Influence of the fusiform gyrus on amygdala response to emotional faces in the non-clinical range of social anxiety. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:1177–87. doi: 10.1017/S003329170800500X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Chiba AA, Gallagher M. Orbitofrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala encode expected outcomes during learning. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:155–9. doi: 10.1038/407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Setlow B, Saddoris MP, Gallagher M. Encoding predicted outcome and acquired value in orbitofrontal cortex during cue sampling depends upon input from basolateral amygdala. Neuron. 2003;39:855–67. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CD, Lori NF, Akbudak E, et al. MRI diffusion tensor tracking of a new amygdalo-fusiform and hippocampo-fusiform pathway system in humans. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2009;29:1248–61. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D, Charman T, Blair RJ. Recognition of emotion in facial expressions and vocal tones in children with psychopathic tendencies. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2001;162:201–11. doi: 10.1080/00221320109597961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Third Edition (WAIS-III) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.