Abstract

Drug-induced action potential (AP) prolongation leading to Torsade de Pointes is a major concern for the development of anti-arrhythmic drugs. Nevertheless the development of improved anti-arrhythmic agents, some of which may block different channels, remains an important opportunity. Partial block of the late sodium current (INaL) has emerged as a novel anti-arrhythmic mechanism. It can be effective in the settings of free radical challenge or hypoxia. In addition, this approach can attenuate pro-arrhythmic effects of blocking the rapid delayed rectifying K+ current (IKr). The main goal of our computational work was to develop an in-silico tool for preclinical anti-arrhythmic drug safety assessment, by illustrating the impact of IKr/INaL ratio of steady-state block of drug candidates on “torsadogenic” biomarkers. The O’Hara et al. AP model for human ventricular myocytes was used. Biomarkers for arrhythmic risk, i.e., AP duration, triangulation, reverse rate-dependence, transmural dispersion of repolarization and electrocardiogram QT intervals, were calculated using single myocyte and one-dimensional strand simulations. Predetermined amounts of block of INaL and IKr were evaluated. “Safety plots” were developed to illustrate the value of the specific biomarker for selected combinations of IC50s for IKr and INaL of potential drugs. The reference biomarkers at baseline changed depending on the “drug” specificity for these two ion channel targets. Ranolazine and GS967 (a novel potent inhibitor of INaL) yielded a biomarker data set that is considered safe by standard regulatory criteria. This novel in-silico approach is useful for evaluating pro-arrhythmic potential of drugs and drug candidates in the human ventricle.

Keywords: anti-arrhythmic, drug safety, multi-channel block, reverse rate-dependence, late sodium current, transmural dispersion of repolarization

Introduction

The emerging importance of the role of an enhanced late sodium current (INaL) in mammalian ventricle as a contributor to the pathogenesis of acquired and hereditary disease has resulted in this current being a target for anti-arrhythmic drug development. Under relatively common pathological conditions, INaL density is enhanced significantly (2- to 5-fold) in ventricle. These conditions include heart failure, oxidative stress, hypoxia, ventricular hypertrophy and LQT-related mutations. When INaL is increased, the action potential duration (APD) of human ventricular myocytes lengthens.1-3 This may lead to initiation and/or maintenance of arrhythmias such as Torsade de Pointes (TdP).4,5 In all such cases the repolarization reserve is reduced.

Several experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated significant anti-arrhythmic effects of INaL blockers, such as ranolazine.6-9 However, ranolazine and other compounds in development, which are relatively selective for INaL, may also block other ion channels such as delayed rectifier potassium channels (IKr). This effect can result in action potential (AP) prolongation.7 Recently, a potent and selective inhibitor of cardiac INaL, GS967, has been reported to suppress experimental arrhythmias in female rabbits.10 It is a requirement of the process of drug development to evaluate the ratio for INaL/IKr blockade for this drug candidate.

For this purpose, detailed understanding of the role of the ionic currents involved in the different phases of AP repolarization (early, intermediate and late phases) is essential. The delicate balance of the small ionic currents, which underlie the AP plateau, determines the impact of these drugs on APD prolongation and other biomarkers for arrhythmic risk (e.g., AP triangulation). Although several experimental and theoretical studies of this have yielded substantial information,11-21 further investigation based on data and principles from human ventricle is required to fully understand ionic mechanisms underlying drug-induced changes in APD.

It is noteworthy that APD prolongation alone appears to be insufficient to define “torsadogenic” risk.22 Additional biomarkers for arrhythmic risk must be identified and evaluated when defining anti-arrhythmic drug safety. Indeed, changes in QT interval (QTint), reverse rate-dependence (RRD) of APD prolongation and transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) have been also proposed as “torsadogenic” indicators.22-24

Within the past 3 y, computer simulations have been employed in drug development programs with the goal of assessing in silico risk for drug-induced cardiac arrhythmia.25-28 However, only Mirams et al.25 and Sarkar et al.29 utilized human AP models, in addition to models of the rabbit and dog ventricular APs.

The main goals of this project were to identify the relative role of ionic currents at defined phases of repolarization in human ventricle and to use this information to reveal and illustrate the impact of INaL and IKr block on selected biomarkers that define arrhythmic risk. Our analysis reveals the biophysical basis for reverse rate-dependence in human ventricle. In addition, a new simulation tool denoted the “safety plot” is developed and utilized to assess drug safety for INaL blockers.

Results

Effects of INaL and IKr block on repolarization of diseased human ventricular AP

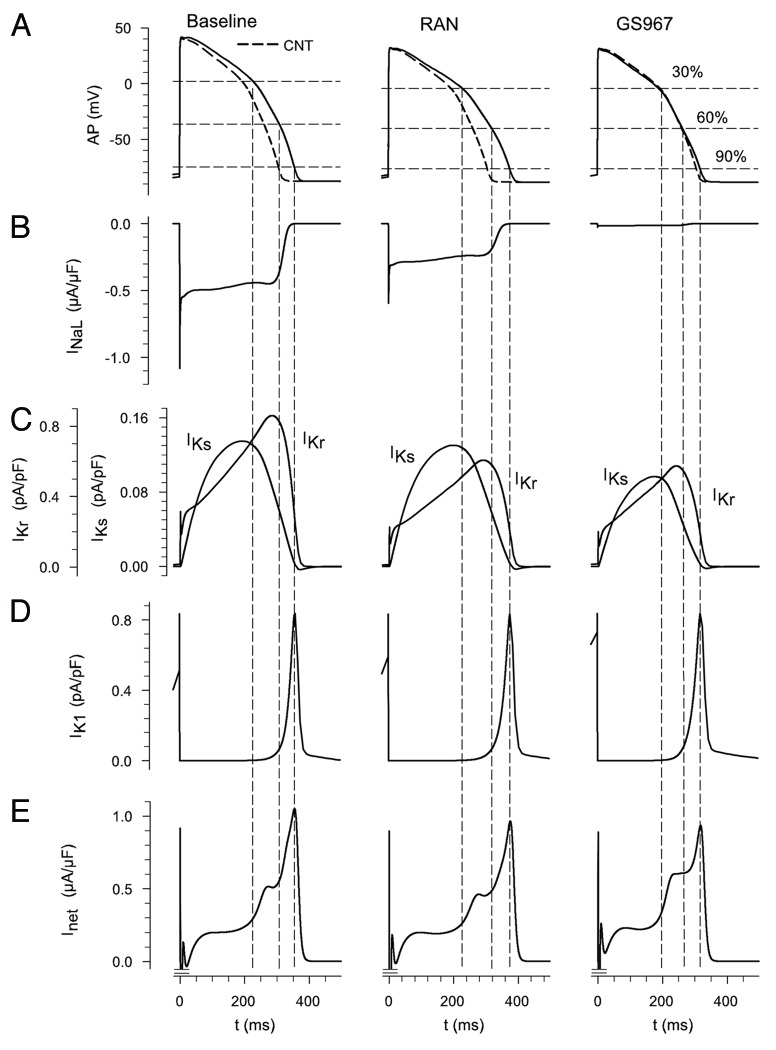

Single isolated myocyte simulations were conducted to reveal the effects of ranolazine and GS967 on AP waveform and to study the changes of several “plateau” ionic currents at defined stages during repolarization. Figure 1A shows the APs for baseline (left) together with the effects of ranolazine (center) and GS967 (right). Control AP is also shown (see dashed lines) in the three cases for reference. Ranolazine had no significant effects, apparently, changing APD30 to 100.9%, APD60 to 103% and APD90 to 105% of baseline values. In contrast, GS967 decreased APD30 to 86.9%, APD60 to 87.2% and APD90 to 91.1% of baseline. The higher selectivity of GS967 for INaL (IC50 of 0.13 μM and > 10 μM for INaL and IKr, respectively)10 compared with ranolazine, can account for its effect on APD compared with ranolazine. The differences in the changes of APD at the selected phases of repolarization can be explained by the different sizes and functional roles of the repolarization currents. For example, Figure 1B shows the small role of INaL at 90% of repolarization but also illustrates the more important role of the current at 30% and 60%. A similar pattern also holds for IKr and IKs (Fig. 1C) at 90% of repolarization. However, the waveform of repolarization also depends on the delicate balance of many other ionic currents (e.g., IK1, ICaL). Thus, the Inet (Fig. 1E) is a key variable to “track.” In general, in human ventricle a relatively specific drug for INaL has greater effects on the early phase of repolarization. This effect on early as opposed to late repolarization has been termed an increase in triangulation.24

Figure 1. Illustrations of the three main sets of conditions that are analyzed in these simulations of the ventricular action potential (AP). The top row (A) shows APs computed at 1 Hz in response to baseline conditions (left), baseline plus ranolazine (center) and a novel ranolazine derivative, GS967 (right). Note that in all calculations the baseline condition is intended to mimic the enhanced INaL, which is a hallmark feature of LQT3 syndrome.30 Thus, INaL was increased 2-fold over the value in the control conditions. The dashed line shows control AP. (B) shows baseline INaL (left) and reductions in the current following steady-state effects of ranolazine or GS967. (C) shows the relative sizes and approximate time course of the two time and voltage-dependent K+ currents in human ventricle. Note the difference in current scales for IKr vs. IKs. (D) illustrates the inwardly rectifying backgroud K+ current IK1. In (E) the net outward current during the plateau and repolarization phases of the AP are shown. The negative peak was truncated to better observe the shape of this current in a bigger scale. The dotted vertical lines provide reference points dennoting 30%, 60% and 90% of complete AP repolarization.

Rate-dependent effects of INaL and IKr block on repolarization

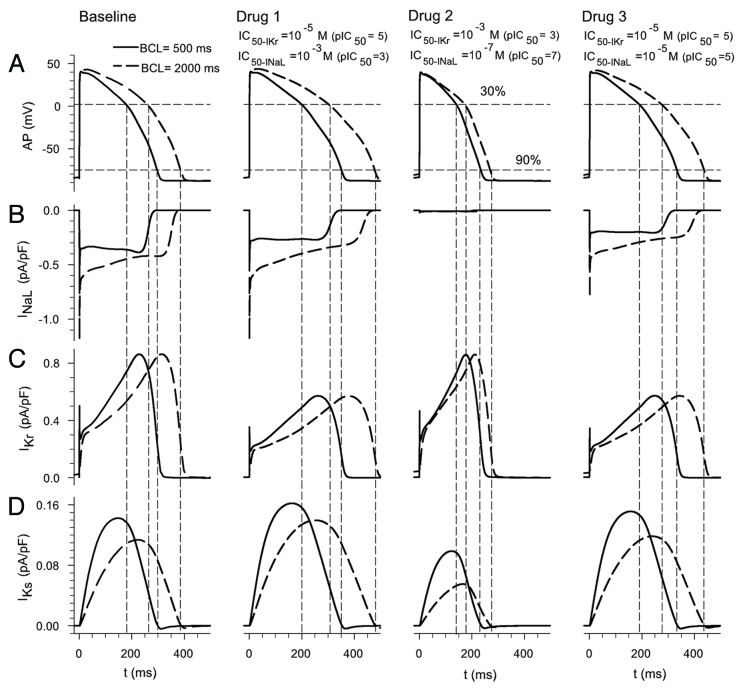

To begin to explore the effects of INaL and IKr blockers on rate-dependent APD changes, APs at two different steady-state stimulation frequencies were simulated. Test compounds with different degrees of specificity for the selected ion channels were “applied” by varying the IC50 for INaL and IKr. In all the cases the amount of block was calculated for a drug at a concentration of 5 μM. Figure 2 shows APs and several underlying ionic currents for a basic cycle length (BCL) 500 ms (continuous trace) and 2000 ms (discontinuous trace). The superimposed data depict (1) baseline (column 1), (2) in the presence of a drug specific for IKr (IC50 of 10−5 and 10−3 M for IKr and INaL, respectively) in column 2, (2) a drug specific for INaL (IC50 of 10−3 and 10−7 M for IKr and INaL, respectively) in column 3 and (4) a drug with the same specificity for these two ion channels (IC50 of 10−5 M for IKr and INaL) in column 4. As expected, these results demonstrate that a drug more specific for IKr (column 2) prolongs APD90, and this effect is larger at low frequencies (discontinuous trace) than at high frequencies (continuous trace), 124% and 118% of baseline at 0.5 Hz and 2 Hz, respectively. The so-called reverse rate-dependence effect exerted by IKr blockers, i.e., a greater APD prolongation at low frequencies (see Fig. 2C), can be in part explained by IKs accumulation at the higher frequency (residual activation), as experimentally observed by others.31 We note how in the O’Hara et al.32 (ORd) model the contribution of IKr does not change significantly with frequency. IKs is larger at the higher frequency due to residual activation.

Figure 2. Effect of change in steady-state heart rate on drug-induced block of INaL and IKr. Action potentials (APs) (A), INaL (B), IKr (C) and IKs (D) at BCLs of 2000 and 500 ms (dashed and continuous traces, respectively) under selected conditions: (1) column 1 baseline conditions, (2) drug 1 (more specific for IKr) in column 2, (3) drug 2 (more specific for INaL) in column 3 and (4) drug 3 (same specificity for INaL and IKr) in column 4.

Note that if the drug is more selective for INaL (column 3), APD90 is further shortened at low frequencies (69% and 78% of baseline value at 0.5 Hz and 2 Hz, respectively). This is because the contribution of INaL to net current is relatively large at low frequencies.

When the drug has the same specificity for INaL and IKr (column 4), the changes in APD90 are similar for both cycle lengths (113% and 112% of baseline value at 0.5 Hz and 2 Hz, respectively). Note that the reverse rate-dependence effect due to IKr block is neutralized by INaL block, as has been observed in rabbit ventricular myocytes.33 This pattern of changes holds for APD30 and APD60. Our results show that the INaL/IKr ratio of blockade of potential drugs has an important effect on reverse rate-dependence, which is an indicator to evaluate drug safety.

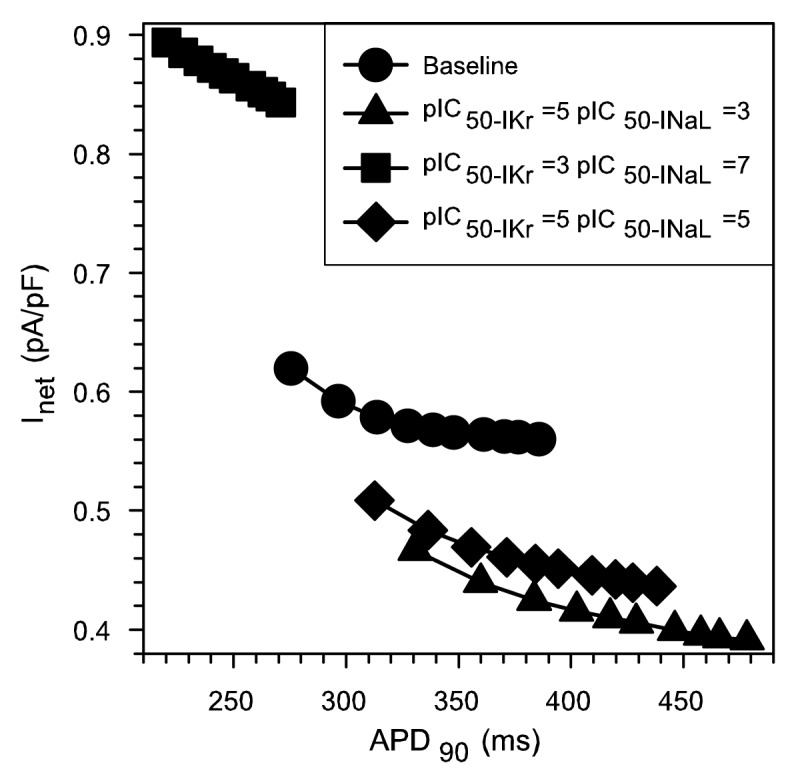

To further investigate the ionic mechanisms of reverse rate-dependence observed in the presence of INaL and IKr blockers, we calculated the net current. Indeed, as postulated by Banyasz et al.,34 RRD is an intrinsic property of these human ventricular cells; stimulus frequency modulates APD, so that at low frequencies APD is longer. In all cases, when APD is long, the net current is very small. As a consequence, any change in the very small net current (e.g., due to drug effect) causes prominent changes in APD. The opposite effects take place at high frequencies when APD is shorter and the net outward current is larger. We computed the net current at the instant of time corresponding to APD60 for the four cases considered in Figure 2 (baseline, drug 1, 2 and 3), always assuming 5 μM of the drugs with variable specificities for INaL and IKr. These changes were evaluated at different steady-state cycle lengths (from BCL 500 ms to 2000 ms). The relationship between the net current and the APD90 is illustrated in Figure 3. These results are in accordance with experimental observations of Banyasz et al.34: That is, longer APDs tend to correspond to lower net currents regardless of the drug used.

Figure 3. Instantaneous net current measured at APD60 as a function of APD90 for different combinations of IKr/INaL IC50 ratios (different symbols). For each curve, corresponding to a specific combination of IKr/INaL IC50 ratio, simulations were performed at increasing BCLs from 500 ms to 2000 ms in each curve. Baseline corresponds to conditions where only INaL is enhanced 2-fold and no drug is applied.

APD and rate dependence safety plots

As described above, our results show the INaL/IKr ratio of blockade of potential drugs has an important effect on rate-dependent changes in APD. To illustrate this, multiple sets of ventricular myocyte simulations were performed at different but constant stimulation frequencies for selected combinations of INaL and IKr blockade. Potential drugs having IC50 for IKr in the range 10−6 to 10−3 M, and IC50 for INaL in the range 10−7 to 10−3 M were tested at a fixed 5 μM concentration. The effects of different concentrations (3, 5 and 8 μM) at a stimulation frequency of 1 Hz can be observed in Figure S2.

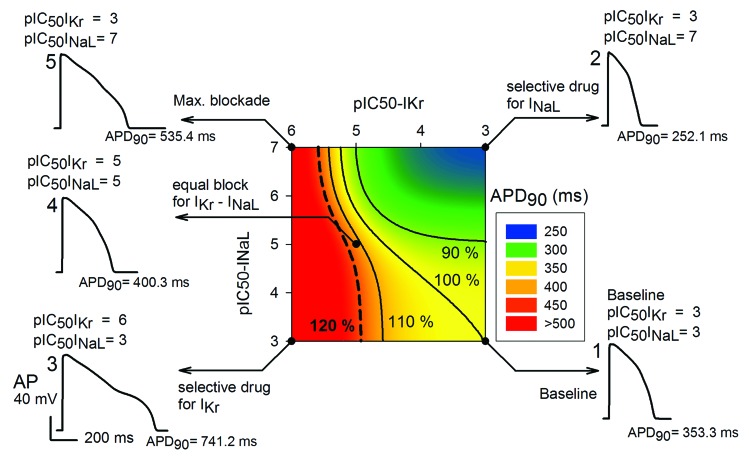

Figure 4 illustrates these findings in the form of a safety plot, using a color scale for APD90 values. Relatively large values for the biomarker (APD90) are represented in red, and relatively small APD values are shown in blue. The circle represented in bottom right corner corresponds to the baseline condition (INaL is enhanced 2-fold). Here, essentially no current block takes place (a pIC50 results in 0.995 of INaL and IKr). APD90 is 353.3 ms in this case. Consideration of data in the right edge of the safety plot, shows that when INaL is progressively blocked (IC50 for INaL decreases, and thus pIC50 increases) the biomarker decreases (APD90 is 252.1 ms in the top right corner). Data to the left in the bottom edge, corresponding to a progressive block of IKr (IC50 for IKr decreases, and pIC50 increases), lead to an increase of the biomarker [APD90 is 741.2 ms with the induction of an early-after depolarization (EAD) in the left bottom corner].

Figure 4. Illustration of combined effects of drugs (at 5 μM), which inhibit IKr, INaL or both on APD90. This “Safety Plot” is constructed using selected values of IC50 for INaL blockers on the y-axis, and IC50values of IKr block on the x-axis. The reference action potentials (APs) shown are (1) baseline waveform at 1 Hz, (2) AP waveform after complete block of only INaL, (3) AP waveform after complete block of only IKr, (4) AP waveform resulting from an equal degree of block of IKr and INaL and (5) AP waveform after complete block of INaL and IKr. Black lines join IC50 combinations for which APD is either increased or decreased by 10% or 20% with respect to the baseline APD shown at the right bottom edge of this matrix. Baseline corresponds to conditions where only INaL is enhanced 2-fold.

But what happens for other combinations of block? Where is the safety barrier? Black lines join the IC50 combinations for which the biomarker is 120%, 110%, 100% and 90% of baseline value, represented in the bottom right corner. The 90% barrier would depict beneficial effects of the drug, as the biomarker is reduced. In contrast, biomarker values, which fall to the left side of the 110% barrier, imply dangerous effects of the drug increasing the biomarker.

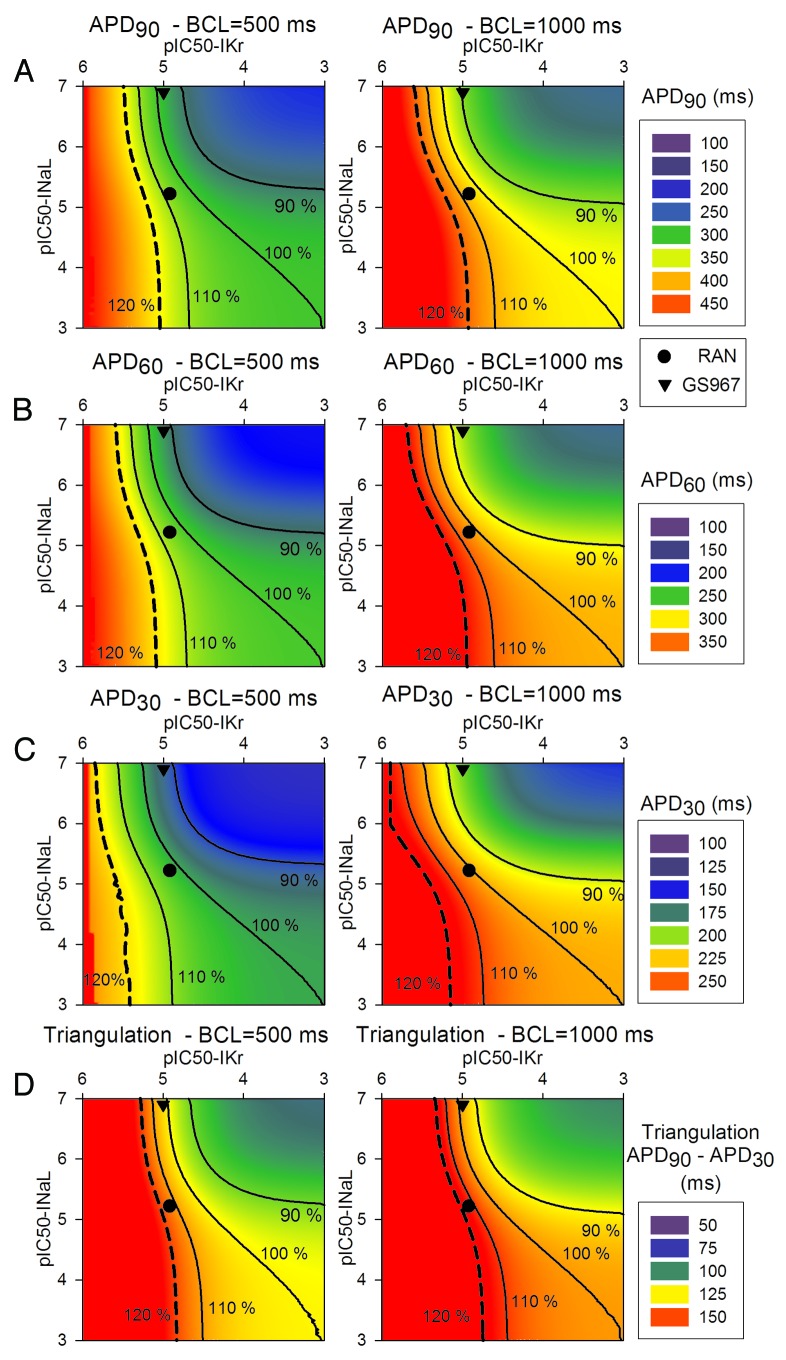

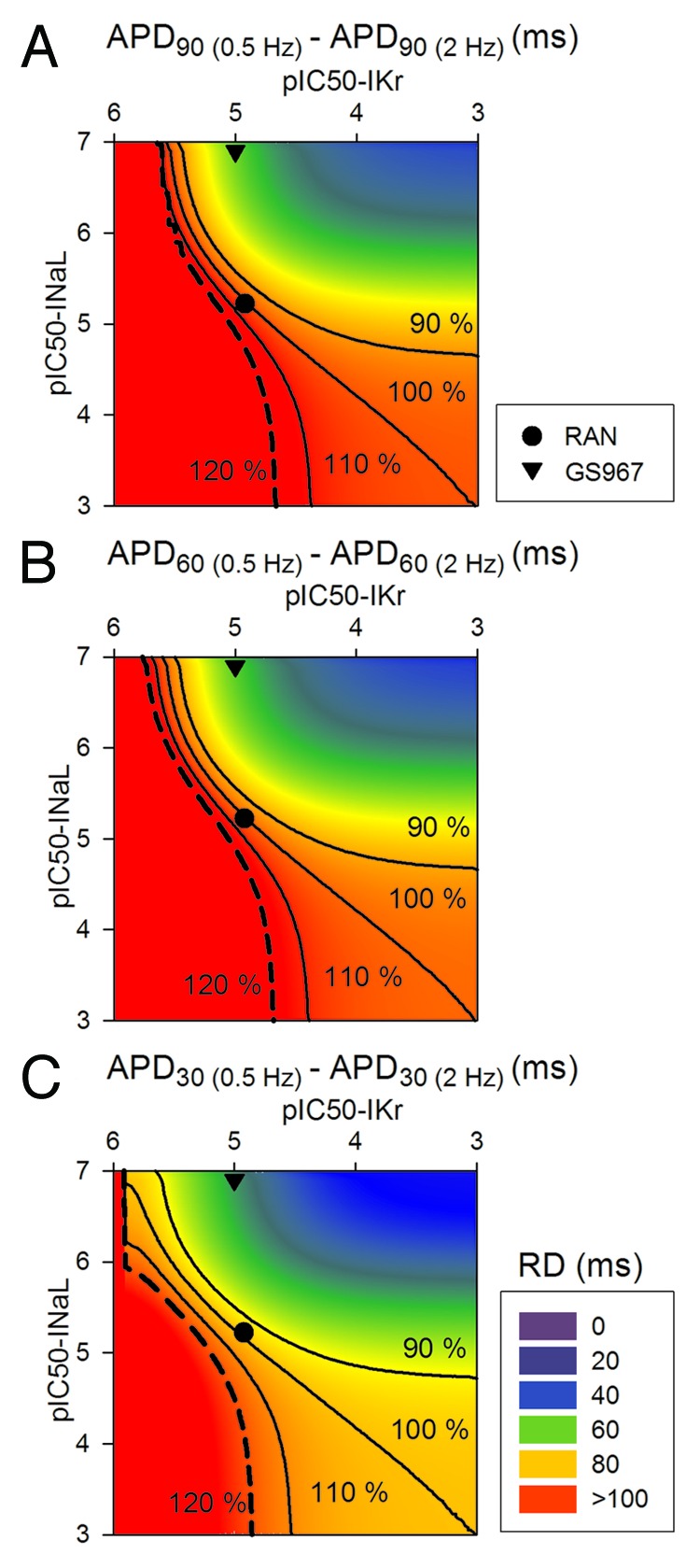

Figure 5 represents safety plots using APD90, APD60, APD30 and triangulation as biomarkers, and the safety plots in Figure 6 illustrate the rate-dependence, i.e., the effect of a BCL change on APD90. Ranolazine, represented by the black circle, can be positioned in the matrix, based on its approximately IC50 of 6 and 12 μM for INaL and IKr, respectively. Note that this drug is located in the “safe” part of the matrix. Also the test compound GS967 (IC50 of 0.13 and > 10 μM for INaL and IKr, respectively), represented by a black triangle, is apparently safer than ranolazine. At high frequencies (first column) shorter APDs and triangulation (blue and green colors) are observed. In contrast, the results at low frequencies (secomd column) show longer APDs (red and yellow colors). As expected, the decrease in APD exerted by GS967 is more pronounced at low frequencies and especially APD30, whereas the slight increase of APD exerted by ranolazine does not result in any significant changes (approximately 110% of the baseline value).

Figure 5. 2D APD90 (A), APD60 (B), APD30 (C) and triangulation (D) safety plots as a function of pIC50 for IKr (horizontal axis) and INaL (vertical axis), for a drug concentration of 5 μM. Here the effects at steady-state of two stimulation frequencies (BCL of 500 ms in the left and BCL of 1000 ms in the right) are illustrated. Ranolazine is represented by the circle and GS967 by the triangle. Black lines join IC50 combinations for which APD or triangulation is either increased or decreased by 10% or 20% with respect to baseline APD or triangulation. As in Figure 4, the baseline data are shown in the right bottom edge of the matrix, which is under conditions where only INaL is enhanced 2-fold.

Figure 6. 2D maps of the effects of steady-state changes in cycle length. APD rate-dependence (RD) was measured as APD(0.5 Hz)-APD(2 Hz). APD90 (A), APD60 (B) and APD30 (C) maps are shown. Black lines join IC50 combinations for which the effects of changes in the cycle length is increased or decreased by 10% or 20% with respect to the baseline data (again represented in the right bottom edge of the matrix, where only INaL is 2-fold enhanced).

AP triangulation data (Fig. 5D) reveal that both ranolazine and GS967 slightly increase this parameter with respect to the baseline value. Specifically, ranolazine further increases APD90 more than APD30, whereas GS967 decreases APD30 more than APD90, at each stimulus rate.

Finally, Figure 6 highlights how drugs very specific for INaL (such as GS967) decrease APD90, APD60 and APD30 rate-dependence, calculated as the difference between APD at minimum frequency and APD at maximum frequency. In the case of ranolazine, the rate dependence (RD) is unchanged (100% of baseline), due to the fact that the block of IKr would provoke large reverse rate-dependence, which is neutralized by the concomitant block of INaL by the drug.

Effects of INaL and IKr blockers on QT interval and transmural dispersion of repolarization

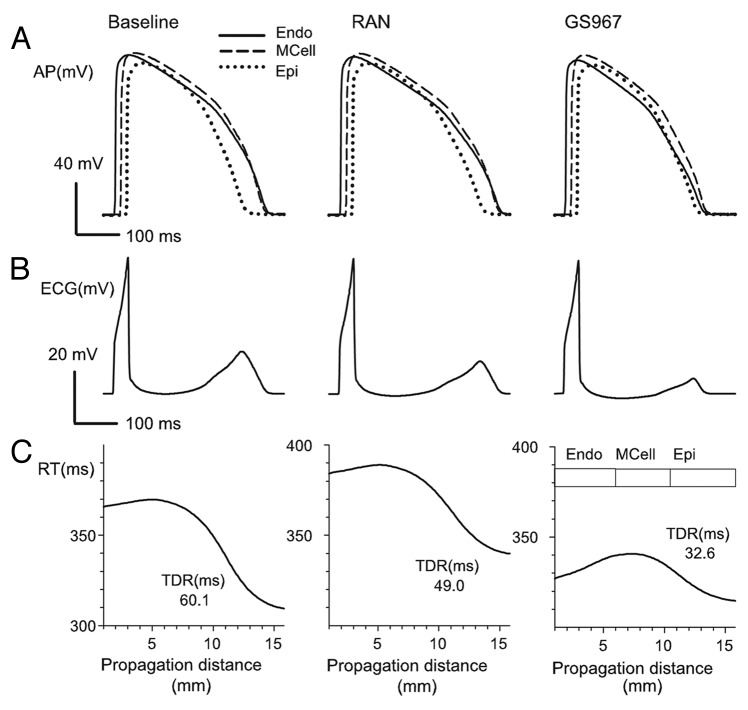

Simulations were performed at tissue level based on an in silico fiber of 165 cells composed of a fixed number of endocardial, M and epicardial cells as described in O’Hara et al.32 Pseudo-ECGs were computed and the corresponding QT intervals were measured. In addition, repolarization times of selected myocytes within the fiber were calculated, and transmural dispersion of repolarization was defined as the difference between the maximum and the minimum repolarization times in the fiber. Figure 7A shows APs measured in the central cells of each part of the tissue (endo-, midmyo- and epicardial tissues) under baseline conditions (left), in the presence of 5 μM ranolazine (center) or GS967 (right). Figure 7B shows the pseudo-ECG for these conditions. Note that QT interval was increased slightly by ranolazine (107% of the baseline value) but was decreased by GS967 (91.4% of the baseline value). Finally, repolarization times at selected myocytes within the fiber are depicted in Figure 7C, and TDR is indicated in the curves. Note that ranolazine and GS967 decreased TDR to 81.5% and 54.2% of the baseline value, respectively.

Figure 7. (A): action potentials (APs) in endocardial (continuous line), Midmyocardial (dashed line) and epicardial (dotted-dashed line) cells at baseline and after ranolazine (5 μM) and GS967 (5 µM). (B): pseudo-ECGs computed and measured as described in Materials and Methods. (C): Repolarization time (RT) profile along the transmural fiber under baseline conditions, and during steady-state effects of ranolazine (5 μM) and GS967 (5 μM). Repolarization times are shown at 90% of repolarization in these three tyopes of ventricular myocytes at baseline, and in the presence of 5 μM of Ranolazine and GS967. Transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) in ms is indicated for each case. Simulations were conducted at a BCL of 1000 ms.

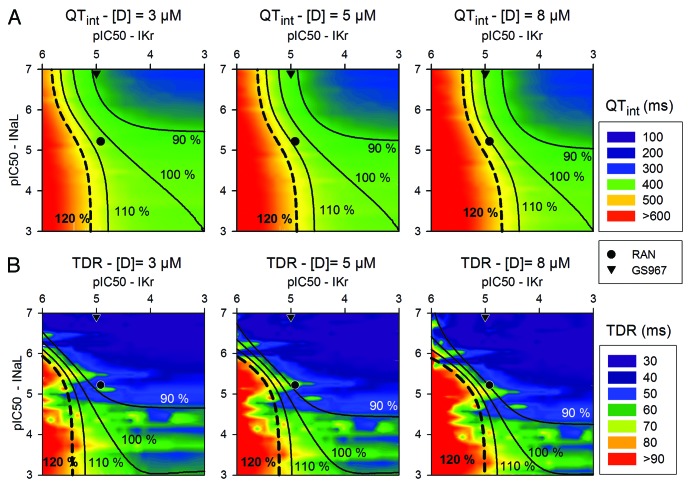

Safety plots based on QT interval and transmural dispersion of repolarization data

Figure 8 summarizes the values of QTint and TDR for different combinations of IKr and INaL blockade in different safety plots for 3 μM (left), 5 μM (center) and 8 μM (right) of potential drugs. The reference QTint and TDR correspond to the baseline conditions (right bottom corner). The results obtained in our simulations indicate that GS967 is safer than ranolazine, as it reduces the QTint down to 90% of its baseline value for the lower concentration.

Figure 8. Safety Plot analysis based on computed QT interval (QTint) (A) or transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) (B), as a function of pIC50 for IKr (horizontal axis) and INaL (vertical axis). Drug concentrations of 3, 5 and 8 μM are considered. Ranolazine is represented by the circle and GS967 by the triangle. Black lines join IC50 combinations for which Qtint or TDR increase or decrease by 10% or 20% with respect to baseline values, represented in the right bottom edge of the matrix, i.e., where only INaL is enhanced 2-fold. Simulations were conducted at a BCL of 1000 ms.

With regard to the TDR simulations shown in Figure 8B, the two drugs that were assessed reduced TDR quite significantly. This is of interest as TDR is being seriously considered an important biomarker for arrhythmic risk, and very few studies have tested the effects of drugs on this biomarker. The reduction of the TDR exerted by these drugs is notable, highlighting their beneficial effects.

Discussion

Major findings

Our computational work, based on a current and very comprehensive mathematical model of the human ventricular AP, provides novel insights into the roles of INaL and IKr block in the modulation of well accepted biomarkers for pro-arrhythmic risk. Our approach further illustrates and documents the utility of computational methods as one potential assessment tool in Safety Pharmacology. The principal findings and insights from our work are (1) demonstration that it is essential to study the role of selected drug targeted currents (INaL, IKr, IKs) at defined time points of AP repolarization; (2) novel insight into the ionic mechanisms responsible for reverse rate-dependence of anti-arrhythmic agents: delayed rectifier K+ currents exhibit a relatively large effect on the net current which governs the initiation of repolarization and modulates the repolarization waveform; (3) demonstration of importance of drug-induced APD prolongation assessed at steady-state; (4) an explanation of how selective partial block of INaL confers significant anti-arrhythmic effects in terms of reduction of APD, RRD of APD prolongation, QT interval or TDR; (5) integration of experimental data sets in terms of safety plots to illustrate that the ratios of block of INaL/IKr (measured as IC50 values) for a drug is a novel mechanism-based tool, which can be used to advantage during the initial phases of drug development.

Mechanisms for reverse-rate dependence of drug-induced APD prolongation

The repolarization of AP is determined by the very delicate balance of ionic currents.35 A very small change in this balance (net current) caused by a drug may have important consequences on AP morphology and thus on myocyte electrophysiological properties. This concept was first recognized by classical cardiac electrophysiologists35 and originally was termed all-or-none repolarization. Many subsequent studies have provided basis for understanding the ionic mechanisms for repolarization, and the concept of repolarization reserve, through mathematical modeling.13,36 The main goal of the present study (oriented to INaL and IKr block) was to reveal the effects of established or in development anti-arrhythmic drugs on repolarization in human ventricle using computational methods. Our results show that a new and very selective blocker for INaL (GS967) has a relatively large effect on the early phase of repolarization (significant decrease of APD30) in comparison with its effects on the late phase of repolarization (APD90) whereas other currents, e.g., IK1, strongly modulate APD90. Similar pattern of results has been reported,10 where GS967 reduced APD50 more than APD90 in isolated rabbit myocytes. Previously, somewhat similar results were obtained by Goineau et al.37 in rabbit Purkinje fibers. Lidocaine increased AP triangulation, by reducing APD30 more than APD90. These findings show that the net impact on AP morphology must be evaluated as a net balance of multiple ion channel conductances. In our simulations, as demonstrated in the safety plots of Figure 5, the changes in triangulation due to INaL block also depend on the amount of IKr block, i.e., on the drug specificity. If we consider a pure INaL blocker (moving upwards in the right edge of the safety plots of Figure 5D) AP triangulation tends to diminish as specificity for INaL increases. Figure 2 illustrates a plausible ionic mechanism for this. The observed decrease in AP triangulation in response to selective blockers of INaL is in accordance with the experimental observation that agents that enhance INaL have the opposite effect: an increase in triangulation.38,39 Our results also provide insight into a previous paper that reported an increase in AP triangulation following selective IKr block.40

Another new mechanistic insight from our simulations is that the ratio INaL/IKr of block by drug candidates can strongly influence the drug-induced RRD of the APD even under steady-state conditions. Most contemporary drug discovery or Safety Pharmacology initiatives consider RRD as an important biomarker for pro-arrhythmic actions.22,23,41 It is well known that Class III antiarrhythmic agents, such as dofetilide and other selective blockers of IKr, include RRD effects.31,42 RRD in human ventricle was reproduced by our simulations (see Fig. 6). Specifically, our results showed that selective block of INaL led to APD shortening in a RRD manner, in accordance with experimental studies.33 These counteracting actions lead to a neutralization of the reverse rate-dependence of APD prolongation when a drug blocks both INaL and IKr.5,33 Similar effects have been reported in the setting of simultaneous block of IKr and ICaL.43 In summary, the delicate and dynamic balance between IKr and INaL block as a consequence of any relative affinity (IC50) differences for ion channel targets can explain RRD of APD in human ventricle.

Several hypotheses have been developed to explain the underlying ionic mechanisms for reverse RRD modulation of APD. It was first postulated that IKs accumulation (that is, residual activation) observed at relative high frequencies in guinea-pig myocytes was responsible due to the slow deactivation kinetics of this current.31,44 A somewhat similar phenomenon and species-dependent (see O’Hara et al.45) can be observed in our results (Fig. 2), showing a steeper IKs increase at fast rates. Here, the kinetics of IKs could be a significant factor for the RRD of APD prolongation exerted by IKr blockers. However, IKs cannot be the only cause of RRD. Thus, even in the setting of IKs block by HMR1556, RRD APD prolongation was also observed in canine ventricular myocytes.46

Quite recently, Banyasz et al. have suggested that RRD was an intrinsic property of human ventricular cells.34 Indeed, at low frequencies, when APD is relatively long, the net repolarizing current is very small. Under these conditions any change in the plateau currents can lead to significant changes in APD. Our results provide insight into this. Note that the calculated curvi-linear relationship of the net current correlates strongly with APD90 (Fig. 3). We conclude that in human ventricle intrinsic biophysical properties of IKr and IKs and their combined contribution to Inet result in the basis for reverse rate-dependence of APD.

Safety of INaL blockers

Drug-induced APD prolongation, the associated dispersion in transmural repolarization in the human ventricle and TdP inducibility have emerged as significant concerns in drug safety evaluations. Increases in these parameters can be a major obstacle for drug approval.47 In this context, INaL is emerging as a promising pharmacological target. Inhibition of this component of Na+ current markedly reduces the TdP inducing capability of agents that prolong the QT interval.5 Furthermore, INaL block is likely to have an additional anti-arrhythmic effect, especially in conditions which are characterized by enhanced INaL due to genetic or acquired causes. These include LQT3, heart failure, hypoxia and free radical challenge.6,48-52

Our simulations demonstrate that selective block of INaL (GS967) can decrease well-accepted biomarkers for arrhythmic risk. These include APD, reverse rate-dependence, triangulation, QTint and transmural dispersion of repolarization. This insight is in accordance with experimental findings.10,53 Indeed, Belardinelli et al.10 have reported that in rabbit ventricular myocytes, GS967 almost completely restored the normal APD after it had been markedly increased with ATXII. In control conditions, GS967 had a slight tendency to decrease APD, with the effect being larger for APD50 than for APD90.10 There is also ample experimental and theoretical evidence that INaL enhancement can have opposite pro-arrhtyhmic effects, including an increase of triangulation,54 reverse rate-dependence of APD prolongation measured in transgenic mice with LQT348 or the peak to end interval of the T-wave, which closely approximates TDR, in rabbit ventricular wedges.5 Perhaps more importantly, many experimental studies have shown that inhibition of INaL can markedly reduce the risk of drug-induced TdP, e.g., by IKr blockers. Thus, the combined application of INaL blockers with IKr blockers can improve the safety profile.5,33,43,55-57 This concept was first illustrated by the simulation work of Noble et al.58 and is confirmed by our computational results. Note that ranolazine suppressed early afterdepolarizations (EADs) and reduced the increase in TDR induced by the selective IKr blocker d-sotalol in canice cardiac wedges.57 However, the net effect and clinical consequence of multiple channel blockade (mainly IKr and INaL) by ranolazine is a modest increase in the mean QT interval by 2–6 ms.57,59 This important experimental observation was also reproduced by our results (see Fig. 8), whereas more selective blockers of INaL (such as GS967) reduced QT interval.

Safety plots as a tool for anti-arrhythmic drug development

At present, the preclinical assessment of drug-induced ventricular arrhythmia, a major concern for the international cardiac safety pharmacology community, is based mainly on experimental studies. Recently, however, advanced computational technology for in-silico assessment of the efficacy and safety of specific drugs has emerged as a complementary and potentially valuable tool.28,29,60

Notable research efforts have been made to link molecular dynamics to biophysical models.61 Other detailed models of drug/ion-channel interaction take into account the rate of binding and unbinding62 and can be reproduced in either Hodgkin-Huxley or Markov models formulations.28,63,64 For example a recent study on the atrial-selectivity of ranolazine is based on a markovian model of its inhibiting effects on the sodium channels.65,66

In the present study we have used a classical measure of the drug action, by employing IC50 data, that is the fraction of block of the targeted channel conductance. A recent computational study by Mirams et al.25 provided interesting insights into TdP prediction following simultaneous applications of many different ion channel blockers. Other computational studies have assessed the effects of IKs and/or IKr blockers on several biomarkers for arrhythmic risk as a proof of concept in the preclinical phase of development of drugs.26,27,67 Our work complements and extends these approaches. We have evaluated for the first time the safety of drugs with different ratios of INaL/IKr block, using a recent and very detailed human AP model. Safety was estimated by accepted torsadogenic indicators: APD prolongation, triangulation, reverse rate-dependence, QTint and TDR.22-24 The sizes and shapes of the safety zones vary from one biomarker to the other, but a general pattern of behavior can be observed: As the affinity for INaL block increases, safety (blue and green colors) increases. We note that the safety plot corresponding to the biomarker AP triangulation has the most extense unsafe zone, whereas TDR safety plots have the smallest unsafe zones. In our simulated safety plots a 2-fold enhancement of INaL was considered. Based on our analyses we predict that a pathological situation in which INaL is further enhanced would increase the size of the safety zone. Indeed, if the enhanced INaL has a major role in generating the biomarker parameter, then a specific blocker of this current would tend to restore normal conditions.

Limitations of this study

We acknowledge several limitations of our approach at this stage of its development. Caution should be exercised when placing a data set in the safety plots if the simulations have been conducted at different stimulation frequencies. The efficacy of a drug can change significantly with heart rate.68 In the case of ranolazine, the observed IKr block is independent of stimulus frequency,69 whereas its IC50 for INaL decreases with increased frequency.70 This property was not evaluated in our approach because the required data for GS967 block at different frequencies are not available. After the IC50 changes as a function of stimulation frequency of a specific drug have been specified, this drug can be correctly positioned in the safety plot and the effects on the different biomarkers can be evaluated.

We also acknowledge that, as pointed out by consensus from the Cardiac Physiome Initiative,71,72 development of complex models can include propagation of errors or uncertainty in (1) data selection, (2) interpolation or (3) interpretation. It was principally for these reasons that we selected the ORd model as the fundamental computation platform. The experimental data used to build the model are from the human heart and are very extense. Nonetheless, the ORd model was developed to model normal physiological AP waveforms, and considers the controversial presence of a large number of M cells in a ventricular strand.73 Our application extends this data set to a substrate that is a target for clinical anti-arrhythmic agents or drug candidates new in development.

We conclude that safety plots can provide a very valuable tool in the initial phases of drug development, specifically in the preclinical assessment of the arrhythmogenic risk of compounds that block a number of different ion channels. This tool not only overcomes many limitations of experimentation, but also its predictive capacity allows a better selection of experiments, reducing the cost of drug screening.

Materials and Methods

Human ventricular myocyte model

Simulations of the electrical activity of an endocardial human ventricular myocyte were performed using the human ventricular AP model developed by O’Hara et al.32 (ORd). This model is based on experimental data taken from 140 healthy human hearts; it encompasses the formulation of 18 ionic currents and carrier-mediated fluxes and a detailed formulation of steady-state and transient ion concentrations, including intracellular Ca2+ transients. This model reproduces the electrophysiological behavior of all three types of human ventricular myocytes, with a high degree of fidelity, including alterations due to drug effects.

We have modified the formulation of INaL in ORd model to closely match experimental data from Maltsev et al.74 In their experiments on human ventricular myocytes, INaL/INaT (INaT denotes peak INa) ratio was approximately 0.1%. In our model, the maximum conductance (gNaL) was fitted accordingly using voltage clamp simulations, yielding 0.018 mS/μF. The new APD90 remains within experimental values.73,75,76 Details are given in the supplemental material (Fig. S1).

This INaL formulation was modified to simulate the effects of pathological conditions. Specifically, gNaL was enhanced 2-fold, as a surrogate for a genetic modification of the human INa, which results in enhanced INaL and has been denoted LQT3 syndrome,77 or to simulate part of the effects of free radical challenge,49,51 heart failure78,79 or hypoxia.50,52 We refer to this single modification of the ORd model as “baseline conditions” throughout the paper.

All model equations and code were taken from O’Hara et al.,32 which can be downloaded from rudylab.wustl.edu. Rapid integration methods are provided in the Supplemental Materials from O’Hara et al.32 For simulation of the basic human model, we used C++ code run on an array of Dell cluster nodes with 64-bit AMD Opteron processors, running Linux and Sun Microsystems Grid Engine.

Human ventricular strand model

One-dimensional simulations of AP initiation and conduction were performed using a heterogeneous multicellular strand, which resembles some functional features of a ventricular transmural wedge preparation, as described in O’Hara et al.32 This strand was composed by 60 endocardial, 45 M and 65 epicardial cells.

Drugs

The two drugs that have been evaluated in this study are ranolazine and GS967 (6-(4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyridine), a potent and selective inhibitor of INaL.10 Ranolazine has a potency of inhibition (IC50) of 6 and 12 μM for the block of INaL and IKr, respectively,57 and IC50 values for GS967 are 0.13 and > 10 μM for the block of INaL and IKr, respectively. These values were obtained in rabbit ventricular myocytes, as detailed in Belardinelli et al.10

In this study a large number of inter-related sets of simulations were performed. In each, the hypothetical potential drugs were “applied” in selected combinations arranged according to IC50 for INaL and IKr. The ranges of 10−7 to 10−3 M (pIC50 from 7 to 3) and 10−6 to 10−3 M (pIC50 from 6 to 3) were assessed respectively for INaL and IKr. The pharmaceutical description pIC50 (standing for −log IC50) was used. To simulate the steady-state effects of these drugs, INaL and IKr conductances were reduced with a multiplicative factor (1-b), related to the IC50 as follows:

where [D] stands for the concentration of the potential drug. This value is 5 μM in our simulations, which is within the therapeutic concentration for ranolazine (1 to 10 μM).80

Parameter definitions

All APs or other output parameters were measured after achieving steady-state conditions. Steady-state was then defined with an error of 1.9% in APD90 after 100 stimulation pulses. Each applied stimulus was 1.5 the threshold and 2 ms in duration. In the strand simulations, the stimuli were applied at the endocardial end of the fiber. Stimulation rate was varied in some of the single myocyte simulations and was 1 Hz in 1D-fiber simulations.

Several accepted biomarkers for arrhythmic risk were calculated in our set of simulations: APD, triangulation, APD rate-dependence (RD), QTint and transmural dispersion of repolarization. APD values were determined at 90%, 60% and 30% of repolarization and are referred as APD90, APD60 and APD30, respectively. By convention24 triangulation was defined as the difference between APD90 and APD30. APD rate-dependence was calculated as the maximum APD90 (corresponding to the minimum frequency of stimulation of 0.5 Hz) minus the minimum APD90 (corresponding to the maximum frequency of stimulation of 2 Hz). In the multicellular simulations pseudo-ECGs were computed as described in O’Hara et al.,32 and the corresponding QT intervals were measured. Finally, repolarization time (RT) in the selected myocytes of the fiber was computed as the sum of the activation time and the APD90 of this cell. Based on this, transmural dispersion of repolarization was defined as the difference between the maximum and the minimum repolarization times along the heterogeneous fiber.

Ionic currents INaL, IKr, the slow component of the delayed rectifier potassium current (IKs), and the inward rectifier K+ current (IK1) were also measured. Importantly, net current (Inet) was determined as the sum of all ionic currents in the ORd model. This current was continuously measured during the AP (Fig. 1E). Inet was also calculated at a specific instant of time within the AP repolarization phase, i.e., 60% of repolarization (see Fig. 3).

Safety plot construction

We have developed an approach to summarize and illustrate the results of the required complete set of simulations. The effects of potential drugs, having different specificities for INaL and IKr, on a specific biomarker (APD, triangulation, rate-dependence, QTint or transmural dispersion of repolarization) can be illustrated on the plot. This has been achieved by constructing a color-coded map denoted “safety plot” (see Fig. 4; Fig. 5; Fig. 6; Fig. 8; Fig. S2). Each safety plot illustrates the values of the chosen biomarker (e.g., APD90) in a color-coded scale as a function of the pIC50 values for IKr (horizontal axis) and INaL (vertical axis). The simulations were performed for a fixed concentration of the potential drugs (5 μM). Thus, the block amount of both currents could be calculated from the correspondent pIC50. The resulting sets of biomarker values relate molecular pharmacology actions at steady-state to accepted experimental and/or clinical measures of electrophysiological effect on APD90 or QTint. This information is coupled with knowledge of regulatory agency standards for drug-induced changes (denoted by black lines). All simulations were performed under pathological conditions (with enhanced INaL).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by (1) Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica, (2) Plan Avanza en el marco de la Acción Estratégica de Telecomunicaciones y Sociedad de la Información del Ministerio de Industria Turismo y Comercio of Spain (TSI-020100-2010-469), (3) Programa de Apoyo a la Investigación y Desarrollo (PAID-06-11-2002) de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, (4) Programa Prometeo (PROMETEO/2012/030) de la Consellería d'Educació Formació I Ocupació, Generalitat Valenciana and (5) Gilead Sciences, Ltd.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AP

action potential

- APD

action potential duration

- EAD

early afterdepolarization

- IC50

half inhibition concentration

- IKr

rapidly activating rectifying K+ current (hERG)

- IKs

slowly activating rectifying K+ current

- INaL

late sodium current

- IK1

inward rectifying K+ current

- Inet

net membrane current

- LQT3

long QT 3

- pIC50

-log10IC50

- QTint

QT interval

- RRD

reverse rate-dependence

- SF

safety factor for conduction

- TDR

transmural dispersion of repolarization

- GS967

(6-(4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyridine)

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Funding for some of this work was provided by Gilead Science Ltd in the form of an unrestricted grant to investigators at Universitat Politècnica de València.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials may be found here:

http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/channels/article/24905

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/channels/article/24905

References

- 1.Maltsev VA, Silverman N, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas AI. Chronic heart failure slows late sodium current in human and canine ventricular myocytes: implications for repolarization variability. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaza A, Belardinelli L, Shryock JC. Pathophysiology and pharmacology of the cardiac “late sodium current.”. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;119:326–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song Y, Shryock JC, Wagner S, Maier LS, Belardinelli L. Blocking late sodium current reduces hydrogen peroxide-induced arrhythmogenic activity and contractile dysfunction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:214–22. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milberg P, Pott C, Fink M, Frommeyer G, Matsuda T, Baba A, et al. Inhibition of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger suppresses torsades de pointes in an intact heart model of long QT syndrome-2 and long QT syndrome-3. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1444–52. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia S, Lian J, Guo D, Xue X, Patel C, Yang L, et al. Modulation of the late sodium current by ATX-II and ranolazine affects the reverse use-dependence and proarrhythmic liability of IKr blockade. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:308–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Undrovinas AI, Belardinelli L, Undrovinas NA, Sabbah HN. Ranolazine improves abnormal repolarization and contraction in left ventricular myocytes of dogs with heart failure by inhibiting late sodium current. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(Suppl 1):S169–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu L, Shryock JC, Song Y, Li Y, Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L. Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in a guinea pig in vitro model of long-QT syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:599–605. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Schwarz KQ, Rosero S, McNitt S, Robinson JL. Ranolazine shortens repolarization in patients with sustained inward sodium current due to type-3 long-QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19:1289–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song Y, Shryock JC, Wu L, Belardinelli L. Antagonism by ranolazine of the pro-arrhythmic effects of increasing late INa in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44:192–9. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belardinelli L, Liu G, Smith-Maxwell C, Wang WQ, El-Bizri N, Hirakawa R, et al. A novel, potent, and selective inhibitor of cardiac late sodium current suppresses experimental arrhythmias. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:23–32. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.198887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bányász T, Koncz R, Fülöp L, Szentandrássy N, Magyar J, Nánási PP. Profile of I(Ks) during the action potential questions the therapeutic value of I(Ks) blockade. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:45–60. doi: 10.2174/0929867043456304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carro J, Rodriguez JF, Laguna P, Pueyo E. A human ventricular cell model for investigation of cardiac arrhythmias under hyperkalaemic conditions. Philos Transact A Math Phys. Eng Sci. 1954;2011:4205–32. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fink M, Giles WR, Noble D. Contributions of inwardly rectifying K+ currents to repolarization assessed using mathematical models of human ventricular myocytes. Philos Transact A Math Phys. Eng Sci. 1842;2006:1207–22. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2006.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopenfeld B. A mathematical analysis of the action potential plateau duration of a human ventricular myocyte. J Theor Biol. 2006;240:311–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maleckar MM, Greenstein JL, Giles WR, Trayanova NA. Electrotonic coupling between human atrial myocytes and fibroblasts alters myocyte excitability and repolarization. Biophys J. 2009;97:2179–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nygren A, Fiset C, Firek L, Clark JW, Lindblad DS, Clark RB, et al. Mathematical model of an adult human atrial cell: the role of K+ currents in repolarization. Circ Res. 1998;82:63–81. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.82.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viswanathan PC, Rudy Y. Pause induced early afterdepolarizations in the long QT syndrome: a simulation study. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:530–42. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu R, Patwardhan A. Effects of rapid and slow potassium repolarization currents and calcium dynamics on hysteresis in restitution of action potential duration. J Electrocardiol. 2007;40:188–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaniboni M. 3D current-voltage-time surfaces unveil critical repolarization differences underlying similar cardiac action potentials: A model study. Math Biosci. 2011;233:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaniboni M. Late phase of repolarization is autoregenerative and scales linearly with action potential duration in mammals ventricular myocytes: a model study. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2012;59:226–33. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2170987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaniboni M, Riva I, Cacciani F, Groppi M. How different two almost identical action potentials can be: a model study on cardiac repolarization. Math Biosci. 2010;228:56–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Vos MA. Assessing predictors of drug-induced torsade de pointes. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:619–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah RR, Hondeghem LM. Refining detection of drug-induced proarrhythmia: QT interval and TRIaD. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:758–72. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hondeghem LM, Carlsson L, Duker G. Instability and triangulation of the action potential predict serious proarrhythmia, but action potential duration prolongation is antiarrhythmic. Circulation. 2001;103:2004–13. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.15.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirams GR, Cui Y, Sher A, Fink M, Cooper J, Heath BM, et al. Simulation of multiple ion channel block provides improved early prediction of compounds’ clinical torsadogenic risk. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:53–61. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obiol-Pardo C, Gomis-Tena J, Sanz F, Saiz J, Pastor M. A multiscale simulation system for the prediction of drug-induced cardiotoxicity. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:483–92. doi: 10.1021/ci100423z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki S, Murakami S, Tsujimae K, Findlay I, Kurachi Y. In silico risk assessment for drug-induction of cardiac arrhythmia. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;98:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mirams GR, Davies MR, Cui Y, Kohl P, Noble D. Application of cardiac electrophysiology simulations to pro-arrhythmic safety testing. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:932–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar AX, Sobie EA. Quantification of repolarization reserve to understand interpatient variability in the response to proarrhythmic drugs: a computational analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1749–55. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CC, Acharfi S, Wu MH, Chiang FT, Wang JK, Sung TC, et al. A novel SCN5A mutation manifests as a malignant form of long QT syndrome with perinatal onset of tachycardia/bradycardia. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:268–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weirich J, Antoni H. Rate-dependence of antiarrhythmic and proarrhythmic properties of class I and class III antiarrhythmic drugs. Basic Res Cardiol. 1998;93(Suppl 1):125–32. doi: 10.1007/s003950050236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Hara T, Virág L, Varró A, Rudy Y. Simulation of the undiseased human cardiac ventricular action potential: model formulation and experimental validation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu L, Ma J, Li H, Wang C, Grandi E, Zhang P, et al. Late sodium current contributes to the reverse rate-dependent effect of IKr inhibition on ventricular repolarization. Circulation. 2011;123:1713–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bányász T, Bárándi L, Harmati G, Virág L, Szentandrássy N, Márton I, et al. Mechanism of reverse rate-dependent action of cardioactive agents. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:3597–606. doi: 10.2174/092986711796642355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noble D, Tsien RW. The repolarization process of heart cells. In: DeMello WC, ed. Electrical Phenomena in the Heart. New York: Academic Press, 1972:133-161. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fink M, Noble D, Virag L, Varro A, Giles WR. Contributions of HERG K+ current to repolarization of the human ventricular action potential. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96:357–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goineau S, Castagné V, Guillaume P, Froget G. The comparative sensitivity of three in vitro safety pharmacology models for the detection of lidocaine-induced cardiac effects. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2012;66:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu L, Guo D, Li H, Hackett J, Yan GX, Jiao Z, et al. Role of late sodium current in modulating the proarrhythmic and antiarrhythmic effects of quinidine. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1726–34. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diness JG, Hansen RS, Nissen JD, Jespersen T, Grunnet M. Antiarrhythmic effect of IKr activation in a cellular model of LQT3. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laursen M, Olesen SP, Grunnet M, Mow T, Jespersen T. Characterization of cardiac repolarization in the Göttingen minipig. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2011;63:186–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hondeghem LM. Thorough QT/QTc not so thorough: removes torsadogenic predictors from the T-wave, incriminates safe drugs, and misses profibrillatory drugs. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:337–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hondeghem LM, Snyders DJ. Class III antiarrhythmic agents have a lot of potential but a long way to go. Reduced effectiveness and dangers of reverse use dependence. Circulation. 1990;81:686–90. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.81.2.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bril A, Forest MC, Cheval B, Faivre JF. Combined potassium and calcium channel antagonistic activities as a basis for neutral frequency dependent increase in action potential duration: comparison between BRL-32872 and azimilide. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:130–40. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jurkiewicz NK, Sanguinetti MC. Rate-dependent prolongation of cardiac action potentials by a methanesulfonanilide class III antiarrhythmic agent. Specific block of rapidly activating delayed rectifier K+ current by dofetilide. Circ Res. 1993;72:75–83. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.72.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Hara T, Rudy Y. Quantitative comparison of cardiac ventricular myocyte electrophysiology and response to drugs in human and nonhuman species. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1023–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00785.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stengl M, Volders PG, Thomsen MB, Spätjens RL, Sipido KR, Vos MA. Accumulation of slowly activating delayed rectifier potassium current (IKs) in canine ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;551:777–86. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah RR. The significance of QT interval in drug development. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:188–202. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nuyens D, Stengl M, Dugarmaa S, Rossenbacker T, Compernolle V, Rudy Y, et al. Abrupt rate accelerations or premature beats cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mice with long-QT3 syndrome. Nat Med. 2001;7:1021–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gautier M, Zhang H, Fearon IM. Peroxynitrite formation mediates LPC-induced augmentation of cardiac late sodium currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fearon IM, Brown ST. Acute and chronic hypoxic regulation of recombinant hNa(v)1.5 alpha subunits. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:1289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward CA, Giles WR. Ionic mechanism of the effects of hydrogen peroxide in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1997;500:631–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saint DA. The cardiac persistent sodium current: an appealing therapeutic target? Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1133–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zygmunt AC, Eddlestone GT, Thomas GP, Nesterenko VV, Antzelevitch C. Larger late sodium conductance in M cells contributes to electrical heterogeneity in canine ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H689–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.2.H689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trenor B, Cardona K, Gomez JF, Rajamani S, Ferrero JM, Jr., Belardinelli L, et al. Simulation and mechanistic investigation of the arrhythmogenic role of the late sodium current in human heart failure. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wasserstrom JA, Salata JJ. Basis for tetrodotoxin and lidocaine effects on action potentials in dog ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:H1157–66. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.6.H1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin RL, McDermott JS, Salmen HJ, Palmatier J, Cox BF, Gintant GA. The utility of hERG and repolarization assays in evaluating delayed cardiac repolarization: influence of multi-channel block. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;43:369–79. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Zygmunt AC, Burashnikov A, Di Diego JM, Fish JM, et al. Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation. 2004;110:904–10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139333.83620.5D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noble D, Noble PJ. Late sodium current in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease: consequences of sodium-calcium overload. Heart. 2006;92(Suppl 4):iv1–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Hod H, Murphy SA, Belardinelli L, Hedgepeth CM, et al. Effect of ranolazine, an antianginal agent with novel electrophysiological properties, on the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from the Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36) randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2007;116:1647–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoefen R, Reumann M, Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, O-Uchi J, Gu Y, et al. In silico cardiac risk assessment in patients with long QT syndrome: type 1: clinical predictability of cardiac models. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2182–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silva JR, Pan H, Wu D, Nekouzadeh A, Decker KF, Cui J, et al. A multiscale model linking ion-channel molecular dynamics and electrostatics to the cardiac action potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11102–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904505106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Starmer CF, Nesterenko VV, Undrovinas AI, Grant AO, Rosenshtraukh LV. Lidocaine blockade of continuously and transiently accessible sites in cardiac sodium channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23(Suppl 1):73–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90026-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rudy Y, Silva JR. Computational biology in the study of cardiac ion channels and cell electrophysiology. Q Rev Biophys. 2006;39:57–116. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clancy CE, Zhu ZI, Rudy Y. Pharmacogenetics and anti-arrhythmic drug therapy: a theoretical investigation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H66–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00312.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zygmunt AC, Nesterenko VV, Rajamani S, Hu D, Barajas-Martinez H, Belardinelli L, et al. Mechanisms of atrial-selective block of Na⁺ channels by ranolazine: I. Experimental analysis of the use-dependent block. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1606–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00242.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nesterenko VV, Zygmunt AC, Rajamani S, Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C. Mechanisms of atrial-selective block of Na⁺ channels by ranolazine: II. Insights from a mathematical model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1615–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00243.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zemzemi N, Bernabeu MO, Saiz J, Cooper J, Pathmanathan P, Mirams GR, et al. Computational assessment of drug-induced effects on the electrocardiogram: from ion channel to body surface potentials. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:718–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2nd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rajamani S, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Rapid kinetic interactions of ranolazine with HERG K+ current. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51:581–9. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181799690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rajamani S, El-Bizri N, Shryock JC, Makielski JC, Belardinelli L. Use-dependent block of cardiac late Na(+) current by ranolazine. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1625–31. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bassingthwaighte J, Hunter P, Noble D. The Cardiac Physiome: perspectives for the future. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:597–605. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.044099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Quinn TA, Granite S, Allessie MA, Antzelevitch C, Bollensdorff C, Bub G, et al. Minimum Information about a Cardiac Electrophysiology Experiment (MICEE): standardised reporting for model reproducibility, interoperability, and data sharing. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;107:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Glukhov AV, Fedorov VV, Lou Q, Ravikumar VK, Kalish PW, Schuessler RB, et al. Transmural dispersion of repolarization in failing and nonfailing human ventricle. Circ Res. 2010;106:981–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.204891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maltsev VA, Undrovinas AI. A multi-modal composition of the late Na+ current in human ventricular cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li GR, Feng J, Yue L, Carrier M. Transmural heterogeneity of action potentials and Ito1 in myocytes isolated from the human right ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H369–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Drouin E, Charpentier F, Gauthier C, Laurent K, Le Marec H. Electrophysiologic characteristics of cells spanning the left ventricular wall of human heart: evidence for presence of M cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:185–92. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00167-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berecki G, Zegers JG, Bhuiyan ZA, Verkerk AO, Wilders R, van Ginneken AC. Long-QT syndrome-related sodium channel mutations probed by the dynamic action potential clamp technique. J Physiol. 2006;570:237–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maltsev VA, Silverman N, Sabbah HN, Undrovinas AI. Chronic heart failure slows late sodium current in human and canine ventricular myocytes: implications for repolarization variability. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Valdivia CR, Chu WW, Pu J, Foell JD, Haworth RA, Wolff MR, et al. Increased late sodium current in myocytes from a canine heart failure model and from failing human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:475–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Fraser H. Inhibition of the late sodium current as a potential cardioprotective principle: effects of the late sodium current inhibitor ranolazine. Heart. 2006;92(Suppl 4):iv6–14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.078790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.