Abstract

Connexin hemichannels are postulated to form a cell permeabilization pore for the uptake of fluorescent dyes and release of cellular ATP. Connexin hemichannel activity is enhanced by low external [Ca2+]o, membrane depolarization, metabolic inhibition, and some disease-causing gain-of-function connexin mutations. This manuscript briefly reviews the electrophysiological channel conductance, permeability, and pharmacology properties of connexin hemichannels, pannexin 1 channels, and purinergic P2X7 receptor channels as studied in exogenous expression systems including Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cell lines such as HEK293 cells. Overlapping pharmacological inhibitory and channel conductance and permeability profiles makes distinguishing between these channel types sometimes difficult. Selective pharmacology for Cx43 hemichannels (Gap19 peptide), probenecid or FD&C Blue #1 (Brilliant Blue FCF, BB FCF) for Panx1, and A740003, A438079, or oxidized ATP (oATP) for P2X7 channels may be the best way to distinguish between these three cell permeabilizing channel types. Endogenous connexin, pannexin, and P2X7 expression should be considered when performing exogenous cellular expression channel studies. Cell pair electrophysiological assays permit the relative assessment of the connexin hemichannel/gap junction channel ratio not often considered when performing isolated cell hemichannel studies.

Keywords: connexin, gap junction, hemichannel, pannexin, P2X7 receptor, channels

Connexins as Hemichannels

Once the second mammalian gap junction protein was cloned from a rat heart cDNA library, the family of gap junction proteins was given the name “connexins” [1,2]. The notion that the undocked hexamer of connexin subunits, historically called a “connexon”, could form a functional plasmalemma ion channel, i.e. a “hemichannel”, was first reported when attempts to exogenously express the newly cloned lens connexin46 (Cx46) in Xenopus oocytes caused them to lyse [3]. Since the discovery of Cx46 hemichannels, essentially every connexin tested has been induced to form open hemichannels when presented with favorable conditions of low extracellular calcium ([Ca2+]o) and positive membrane potentials (Vm) [4]. Whether connexin hemichannels open under physiological conditions, i.e. negative Vm and 1–2 mM [Ca2+]o, is less certain. A physiological role for lens Cx46 and Cx50 hemichannels has been proposed since the lens is an avascular tissue and the microcirculatory homeostasis of the lens depends on nutrient, electrolyte, and water flow through plasmalemmal channels [5–7]. No connexin hemichannel has received more attention than connexin43 (Cx43) hemichannels. Cx43 is the most abundantly expressed connexin in the human body, being expressed in essentially every tissue with the exception of certain cell types like erythrocytes, skeletal muscle fibers, and spermatozoids [1,8]. The positive correlation between Cx43 expression in macrophage cell lines and the ability of 100 μM ATP4- to permeabilize their cell membranes led to the initial speculation that Cx43 hemichannels form the ATP-release channel in macrophages [9]. However, recent evidence of ATP permeabilization of Cx43 knockout macrophages and discovery of the pro-inflammatory role of purinergic P2X7 and pannexin 1 (Panx1) channels in immune cells provide sufficient reason to question this interpretation [10–12]. Fluorescent dye uptake into cultured Novikoff, normal rat kidney (NRK), human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells, and cortical astrocytes was later proposed to occur via putative Cx43 hemichannels [13–15]. Of paramount importance were the observations that metabolic inhibition activated cardiomyocyte and astrocyte Cx43 hemichannel-mediated dye uptake with eventual loss of membrane integrity and cell death [14,15]. Astrocyte permeabilization, dye uptake, and lysis apparently occurred via Cx43 hemichannels since astrocytes cultured from conditional or germ-line Cx43 knockout mice remained impermeable to Lucifer Yellow (LY) dye after 6 hrs of metabolic inhibition. Metabolic inhibition presumably increased Cx43 hemichannel activity by recruitment of hemichannels to the cell surface, a process that is modulated by Cx43 dephosphorylation and S-nitrosylation [16]. Protein Kinase C (PKC) activation reduces dye uptake by phosphorylation-dependent changes in Cx43 channel conductance and permeability [17]. Thus, there is supportive evidence for a pathophysiological role of Cx43 hemichannel activation during metabolic stress, but physiological activation of connexin hemichannels remains controversial.

The pathophysiological role of connexin hemichannel induced cell membrane permeabilization and death has taken on new meaning with the association of human disease-linked connexin mutations to the genesis of abberant hemichannel activity [18]. Of the 21 human connexin genes, 10 have been linked to inherited human diseases including neuropathies, deafness, skin diseases, oculodentodigital dysplasia (ODDD), and cardiac arrhythmias [19,20]. Many connexin mutations result in loss of gap junction function owing to trafficking deficiencies (i.e. gap junction plaque formation) or channel malformation (non-functional or communication-deficient channels) [21], whereas abnormal connexin hemichannel activity should be considered a gain-of-function mutation. Thus, when considering the functional consequences of a disease-linked connexin mutation, hemichannel activity should be considered as a possible mechanism in addition to the dominant or recessive inhibitory effects of mutant connexin proteins on the formation of homologous and heterologous wild-type connexin gap junction channels.

Pannexin and Purineric P2X7 Receptor channels

Pannexin-1, 2, and 3 (Panx1, Panx2, and Panx3) are vertebrate homologues of the invertebrate innexin gap junction proteins and are abundantly expressed in the central nervous system [22]. They possess a similar membrane topology to the connexins consisting of cytoplasmic N- and C-termini, four transmembrane domains, two cysteine-containing extracellular loops, and one cytoplasmic loop [23]. Panx1 is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, while Panx2 expression is restricted to the CNS. Despite the similar membrane topology, the pannexins share little sequence homology with the connexins and possess only two extracellular loop cysteines instead of three (so does Cx23). Only Panx1 induced large whole cell membrane currents when expressed in Xenopus oocytes and was initially reported to mediate intercellular communication [22]. Hence pannexin channels were called “hemichannels”, denoting their similarity to the connexon hemi-gap junction channel, i.e. connexin hemichannel. Recent evidence disputes the claim that Panx1 forms functional gap junctions, presumably due to the presence of an E2 N-linked glycosylation site that is essential to surface expression [24]. The present day consensus is that the pannexins do not form functional gap junctions and the hexameric Panx1 membrane channel should, therefore, not be referred to as a hemichannel [25].

The P2X(1-7) receptor family form ligand-gated ion channels that are activated specifically by ATP (unlike the P2Y G-protein coupled receptors that are also activated by ADP and other nucleotides) [26]. The P2X receptors form nonselective cationic ion channels that are permeable to Ca2+ and thus contribute to intracellular Ca2+ signaling in response to ATP release. The P2X7 receptor channel is unique among the P2XRs in that it possesses a long cytoplasmic C-terminal domain that contributes to the formation of an additional open “dilated” pore state that results in cell permeabilization and influx of fluorescent dyes with molecular weights of ≤ 800 daltons, e.g YO-PRO-1 [27,28]. Low external divalent cation (e.g. Ca2+ and Mg2+) concentrations potentiate the ATP activation of P2X7 receptors, but will not activate the channel in the absence of the agonist [29]. P2X7 receptor activation first induces a cationic permeability that excludes large organic cations like N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG) and YO-PRO and subsequently induces the dilated pore state that dramatically increases large cation permeability [30]. The trimeric P2X7 receptor subunit possesses cytoplasmic N- and C-termini, two transmembrane domains, and one extracellular loop with numerous disulfide bonded cysteine residues. There is speculation that Panx1 mediates the formation of the large pore state of the P2X7 receptor since Panx1 co-expression, knockdown, or pharmacological blockade correlated with dye uptake in P2X7 expressing cells [31,32]. Panx1 also co-immunoprecipitates with P2X7 when both proteins are expressed in HEK cells, although this association was observed with transient overexpression of an epitope-tagged Panx1 protein [31]. In contrast, one recent study failed to detect a decrease in cellular dye uptake with Panx1 RNAi silencing or pharmacological inhibition of prospective connexin hemichannel or Panx1 channels [33]. Furthermore, structure-function mutagenesis of the P2X7 pore-forming second transmembrane domain increased the permeability to Cl− ions and the anionic dye fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FITC) while decreasing the permeability of the cationic ethidium bromide (EtBr) dye of open P2X7[G345C] mutant receptors, consistent with the intrinsic large pore-forming ability of the P2X7 receptor [34].

Thus, activation of P2X7 and/or Panx1 channels will result in cell permeabilization, intracellular Ca2+ transients, and uptake of fluorescent dyes such as ethidium bromide (EtBr), propidium iodide (PI), Lucifer Yellow (LY), and YO-PRO, as will connexin hemichannels (LY permeability will be limited for the weakly cation-selective connexin hemichannels like Cx40, Cx46, and Cx50 since LY is anionic). Connexin hemichannel conductances range from 17 to 350 pS depending on the connexin type (e.g. 220 pS for Cx43) [4], and reports of the Panx1 channel conductance vary from 300 – 475 pS to recent observations of a ≈70 pS channel [35–38]. A 400–420 pS channel has been described that fits the pharmacological profile of the P2X7 receptor permeabilization pore in macrophages and transfected HEK293 cells [39,40]. Thus, ambiguities about the channel conductances and permeabilities of these three channel types makes distinguishing between them difficult, if not impossible.

External Ca2+ Gating of Connexin Hemichannels

The typical method for demonstrating the presence of connexin hemichannels is to voltage clamp connexin-expressing isolated cells bathed in a divalent-free saline and vary the membrane potential from negative to positive potentials since low [Ca2+]o (< 1 mM) and positive Vm conditions increases the hemichannel open probability (Po) [3–5,8,13,14,41]. Native connexin hemichannel Po is significantly reduced when [Ca2+]o is elevated to physiological levels, e.g. 2 mM. Macroscopic current – voltage relationships (e.g. −80 to +80 mV) and differential high – low [Ca2+]o whole cell current measurements are routine ways to quantify putative connexin hemichannel currents. The 50% inhibitory concentration constant (IC50) for [Ca2+]o closure of Cx46 hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes is 380 μM, 5.3 mM for [Mg2+]o, and may be as low as 100 μM [Ca2+]o for Cx50 hemichannels [5,41]. Intracellular acidification also closes Cx46 hemichannels [4,42]. An external Ca2+-gate is thought to minimize connexin hemichannel Po under physiological conditions, though the molecular identity of the connexin hemichannel calcium gate is still the subject of intense investigation (e.g. Cx26, Cx46). The external Ca2+-gate of Cx26 and Cx32 hemichannels is commonly proposed to be formed from a ring of acidic amino acid residues located on the connexin extracellular loops (E1 and/or E2) [43,44]. The extracellular location of a connexin hemichannel gate was confirmed by a substituted cysteine accessibility method (SCAM) experiment using the thiol-reactive maleimidobutyryl-biocytin (MBB) compound on an L35C mutant Cx46 hemichannel in the presence or absence of 5 mM [Ca2+]o [45]. Experimental examination of a Charcot Marie Tooth disease (CMTX) D178Y Cx32 mutation led to the proposition that the hexameric arrangement of E2 D169 and D178 residues form an extracellular binding pocket for six Ca2+ ions that accounts for the [Ca2+]o sensitivity of Cx32 hemichannels, albeit with a relatively low IC50 of 1.3 mM [44]. Structure-based molecular dynamic simulations and experimental site-directed mutagenesis of Cx26, particularly of disease-associated mutations, approaches to connexin hemichannel gating and permeation are helping to delineate the molecular bases for the differential [Ca2+]o sensitivities of specific connexin hemichannels [43,46].

Pharmacological blockade of connexin, pannexin, and P2X7 channels

The application of known chemical gap junction channel blockers, fluorescent dye uptake assays, and exogenous expression systems are commonly used to associate a particular connexin with the presence of an apparent hemichannel current or molecular (dye/ATP) uptake/release pathway. Chemical classes of gap junction channel blockers include long-chain alkanols (e.g. heptanol, octanol), volatile anesthetics (e.g. halothane), long chain cis-unsaturated fatty acids and related amides (e.g. oleic acid, oleamide), glycyrrhizic acid derivatives (18-α/β glycyrrhetinic acid, carbenoxolone (CBX)), fenamates (e.g. flufenamic acid), and 2-aminophenoxyborate [47–56]. Essentially all of these lipophilic compounds affect the activity of other membrane ion channels or have other physiological effects which limit their utility as selective gap junction channel blockers. The antagonist properties of a variety of large pore channel blockers is summarized by Spray et al. (2006) [57], who also discusses the complexity of distinctly identifying the molecular origin of plasmalemmal permeabilization pores. CBX is often considered the best chemical uncoupling agent for cardiac gap junctions owing to a relative lack of pharmacological effects on the cardiac action potential [58]. However, CBX also blocks the recently identified pannexin1 channels at lower concentrations (5 μM) than Cx43 gap junctions, complicating the use of this agent as a pharmacological identifier of connexin hemichannel activity [56,59]. Selective blockade of Panx1 channels is now possible, however, with probenecid or food dye FD&C Blue #1 (Brilliant Blue FCF, BB FCF) with IC50s of 150 and 0.27 μM, respectively [60,61]. BB FCF may be especially useful since 100 μM BB FCF had no effect on connexin (Cx32E143, Cx46) hemichannels or purinergic P2X7 receptor channels, which are readily activated by benzoylbenzoyl-ATP (BzATP) and inhibited by oxidized ATP (oATP) [60]. P2X7 receptors are relatively resistant to the P2 antagonist suramin, are slowly and irreversibly inhibited by oATP, and are reversibly inhibited by BBG, A740003, and A438079 [62,63]. Selective pharmacological blockade to distinguish connexin hemichannels from Panx1 and P2X7 channels is not readily achievable with known chemical gap junction uncoupling agents. Perhaps the best way to distinguish a P2X7 channel from a Panx1 channel or connexin hemichannel is by selective pharmacological blockade with oATP, A740003, or A438079 for P2X7 channels and probenecid or BB FCF for Panx1 channels.

Another approach to the “selective” blockade of connexin channels was the development of “gap” peptides. Gap26 and Gap27 peptides were designed to mimic the extracellular loop 1 and 2 (E1 and E2) connexin domains and prevent gap junction formation by binding to the undocked connexin hemichannel prior to gap junction formation [64,65]. These connexin mimetic peptides are most effective at inhibiting neo-gap junction formation and fail to inhibit the chimeric Cx32E143 hemichannel activity despite the presence of the specific Cx43 E1 and E2 peptide sequences [66]. The Gap26 and Gap27 peptides partially inhibit Cx43 hemichannels, but also pannexin 1 channels [66,67]. Complicating matters further, a Panx1 mimetic peptide, 10panx1, partially inhibits Cx46 hemichannels despite the lack of decameric peptide sequence homology [66]. These Gap26, Gap27, and 10panx peptides are marketed by commercial vendors. The bottom line is that sequence homology, or the lack thereof, is not a reliable predictor of connexin hemi-, gap junction, or Panx1 channel blocking activity. However, one recently developed Gap 19 connexin cytoplasmic loop mimetic peptide has the unique property of inhibiting Cx43 hemichannels without affecting gap junction communication or Panx1channel activity [68]. The effect of Gap 19 on P2X7 channels has not been examined.

Exogenous expression systems for the study of connexin hemichannels

The presence of three molecularly distinct channels capable of facilitating ATP release, fluorescent dye uptake, and plasmalemmal Ca2+ permeabilization, along with the knowledge that pharmacological gap junction blockade, with the possible exception of Gap19, is poorly selective among P2X7, Panx1, and connexin hemichannels creates a dilemma for studying endogenous or exogenously expressed hemichannels. The two most abundant cellular systems for the exogenous expression of connexins are Xenopus oocytes and communication-deficient cell lines like HeLa or murine neuro2a (N2a) cells [69–71]. These preparations were originally developed for the study of newly cloned connexin gap junction proteins, but have been adapted to the study of connexin hemichannels since the concept of their existence emerged [3]. Xenopus oocytes express an endogenous connexin38, similar to mammalian Cx37, that is capable of heterogeneous coupling with Cx43 and other connexins and must, therefore, be knocked down with Cx38 antisense RNA injections prior to injection of the connexin mRNA to be studied [72]. HeLa cells exhibit a low level of endogenous gap junction coupling, presumably mediated by Cx45, which may complicate interpretation of connexin-specific functional gap junction interactions [73,74]. N2a cells are essentially devoid of endogenous connexin expression [70], but reportedly express Panx1 and P2X7 [75,76].

Another mammalian cell line that is gaining in popularity, particularly for the biophysical study of Panx1 channels, is human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293), and their SV40 large T antigen transfected variant, HEK293T, cells. The HEK293 cell line is commonly used for functional studies of exogenously expressed ion channels and receptors and only infrequently utilized for gap junction studies, e.g. hemichannel function of Cx26 and Cx30 deafness mutations [77–79]. Biophysical studies in HEK293T cells have demonstrated that Panx1 channels are activated by C-terminal caspase cleavage of an auto-inhibitory domain, even in the presence of 2 mM [Ca2+]o and [Mg2+]o, or inhibited by S-nitrosylation [80,81]. Although the original source of these cells is the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) accession code CRL-1573, there are conflicting reports about the immunoreactive expression of Cx43 in HEK293 cells [82,83]. Despite the inability to detect Cx43 gap junctions by Western blot or immunohistochemical staining in HEK293 cells, low levels of endogenous electrical coupling have been recorded [83–85]. Stong et al. [78] reported that the HEK293 cell line lacks endogenous connexin expression, citing a methods chapter on exogenous connexin expression in mammalian cells [86], although the cited work made reference to HeLa cells, not HEK293 cells, and no connexin immunoblots were performed on HEK293 cells until later [82,83]. Since electrical coupling and Cx43 immunolabeling has been detected in HEK293 cells, endogenous connexin expression in HEK293 cells should not be considered null. HEK293 cells do not endogenously express P2X7 receptor channels although they reportedly express Panx1 [87,88].

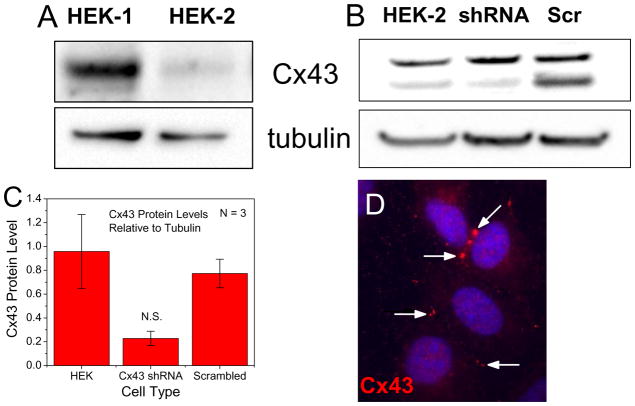

This laboratory tested a population of HEK293T cells in the 1990s and recently tested HEK293 cells obtained from two different laboratories (Fig. 1A) for endogenous gap junction coupling and measurable levels of electrical coupling were always detected. The level of Cx43 expression may vary dependent on the source of the HEK293 cells after decades of culturing, yet high levels of gap junction conductance (gj) were readily measured even in the lower Cx43 expressing variety of HEK293 cells we have assayed (HEK-2). We attempted to knockdown the endogenous Cx43 expression by stable transfection with a shRNA construct directed against human Cx43 (Origene HuSH-29 #SKU-TR312771; human GJA1 29mer shRNA). Four different Cx43 shRNA constructs and one scrambled shRNA control were transfected into HEK293-2 cells and fourteen Cx43 and two control shRNA stable clones were selected with puromycin (2 μg/ml). Clones were immunoblotted for Cx43 protein with tubulin as a loading control as previously described [89]. Representative Western blots of WT HEK293-2, the best Cx43 shRNA clone (#80-1), and one scrambled control are presented in Fig. 1B. These Western blot experiments were performed in triplicate and Cx43 protein levels were quantified by densitometry scans and the Cx43 shRNA construct reduced Cx43 protein expression by 76% relative to wild-type HEK293-2 cells (Fig. 1C). ANOVA analysis indicated that mean Cx43 relative expression levels were not significantly different (F-value = 0.08). We measured the gj values in HEK-2 and the selected Cx43 shRNA HEK293 #80-1 cell pairs by conventional double whole cell patch clamp techniques, corrected for junctional series resistance errors as previously described [90], and the average gj values measured 33.9 ± 10.8 nS, n = 6 for the untransfected HEK-2 cells and 3.6 ± 0.7 nS, n = 7 for the Cx43 shRNA knockdown #80-1 cells. Thus, despite a ¾ decrease in Cx43 expression and a 90% reduction in gj, we were not able to generate a HEK293 cell clone that was devoid of endogenous Cx43 expression and electrical coupling. Gap junction plaques could be detected as small puncta by immunocytochemical methods between cultured wild-type HEK293-2 cells (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

A, An immunoblot for Cx43 showing a variable amount of endogenous Cx43 expression in HEK293 cells obtained from two different research laboratories. B, An immunoblot for Cx43 from the low Cx43 expressing HEK293-2 cells, a stable clone (80-1) of the same cell line after knockdown of Cx43 with an anti-Cx43 shRNA, and a scrambled control shRNA. Tubulin was used as a loading control. C, Quantification of the relative Cx43 expression levels from the HEK-2 cells, the Cx43 shRNA HEK-2 cell clone, and the scrambled shRNA control from three immunoblots like the one displayed in panel B. D, Anti-Cx43 antibody (Millipore #AB1728) was immunolocalized in HEK-2 cells with an Alexa Fluor555 conjugated secondary antibody. Gap junctions appeared as small puncta (arrows) located between adjacent HEK293 cells.

Relative preference of a connexin to form hemichannels or gap junctions

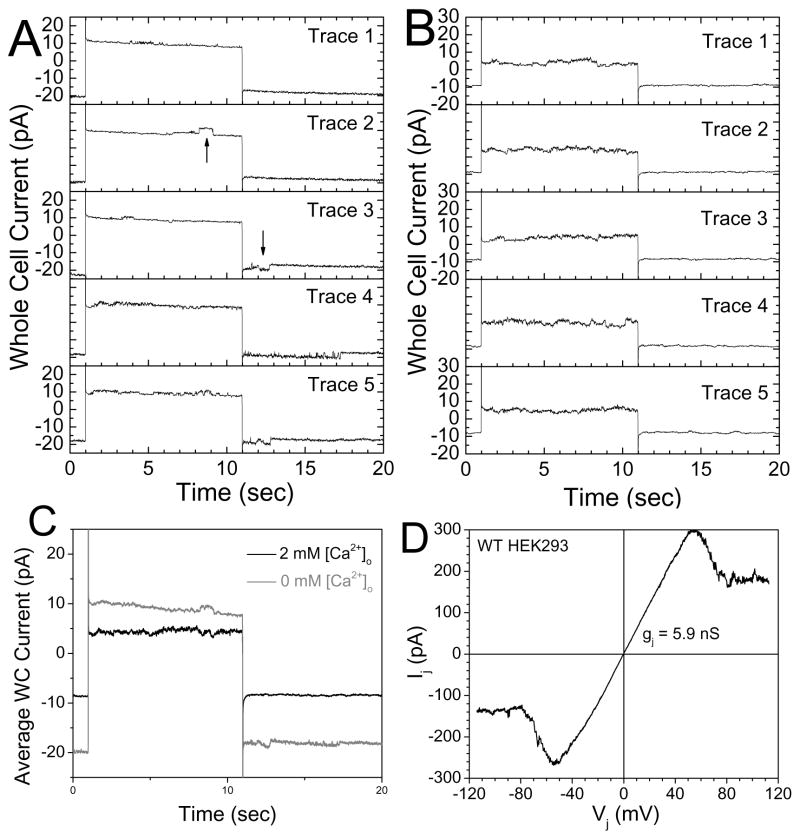

Typically connexin hemichannels are studied in isolated cells, which biases the system in favor of hemichannel formation since the lack of cell-cell contact prevents existing hemichannels from docking to form functional gap junctions. The ability of a particular connexin to form gap junctions instead of hemichannels is rarely considered in the same preparation. John et al. [14] stated that “we cannot absolutely exclude that hemichannel density in isolated myocytes is increased by the isolation procedure”. A structural study of lens Cx50 suggests that there are at least 10-fold more gap junction channels than hemichannels in lens fiber cells [7,91]. Since connexin hemichannels are generally sensitive to [Ca2+]o, we measured the Ca2+-sensitive nonjunctional membrane currents and gap junction currents (Ij) in paired HEK293-2 cells and the Cx43 shRNA knockdown #80-1 clone. At least one presumed Cx43 hemichannel was evident during whole cell current recordings from an HEK293-2 cell in 0 mM [Ca2+]o saline during the activating voltage step pulse from −40 to +30 mV (upward arrow) that sometimes remained open after stepping the membrane potential back to −40 mV (downward arrow) (Fig. 2A). After addition of 2 mM CaCl2 to the bath, the observed hemichannel activity decreased (Fig. 2B) and the ensemble averaged currents revealed a decrease in whole cell current of 15.8 pA during the −40/+30/−40 mV pulse protocol (Fig. 2C). A similar 14.9 pA current decrease was seen with the addition of 2 mM [Ca2+]o in the partner cell (data not shown). By comparison, the slope gap junctional conductance (gj) of this wild-type HEK293-2 cell pair during a ±120 mV Vj ramp measured 5.9 nS, > 25 times higher than the Ca2+-sensitive membrane conductance of 225 pS. Assuming a Cx43 hemichannel conductance (γHC) of 220 pS and a Cx43 gap junction channel conductance (γj) of 110 pS, these values correspond to a single open Cx43 hemichannel and 54 gap junction channels in this HEK293 cell pair. The 2.0 mM [Ca2+]o-sensitive current averaged 0.85 ± 0.49 nS (mean ± SEM, n = 12) in the HEK293-2 cells and 0.38 ± 0.16 nS in the #80-1 cells (n = 10). By comparison, the gj values were 40 and 10 times higher than the endogenous [Ca2+]o-sensitive whole cell current in these HEK and 80-1 cells. If one factors in the respective Cx43 gap junction channel and hemichannel conductances (γj and γHC) of 110 and 220 pS [4], then the approximate gap junction channel to hemichannel ratio is between 20 to 80. This means that only 1.25–5% of the Cx43 channels exist as hemichannels. A 1% occurrence of Cx43 hemichannels in an adult ventricular cardiomyocyte containing approximately 10,000 open gap junction channels (gj ≈ 1 μS, [92]) suggests that a cardiomyocyte may contain a hundred hemichannels, more than enough to cause Na+ and Ca2+ overloading and membrane depolarization if activated [14].

Figure 2.

A, A whole cell patch clamp recordings from an HEK293-2 cell during repeated runs of a −40 to +30 mV voltage step under low (nominally zero) [Ca2+]o conditions. Activation of a membrane channel that remained open upon return to −40 mV was frequently evident. B, A whole cell recording from the same HEK-2 cell after the addition of 2 mM CaCl2 to the bath saline illustrates the reduction in observed endogenous channel activity. C, Ensemble averages of the five current traces displayed in panels A and B illustrating the difference in whole cell currents between 0 and 2 mM [Ca2+]o. D, The junctional current – voltage relationship acquired from this HEK-2 cell coupled to a partner HEK-2 cell via Cx43 gap junctions. The ratio of [Ca2+]o-sensitive nonjunctional membrane current to gap junction current was 0.04 in this HEK-2 cell pair.

Perhaps the best evidence for abberant mutant connexin hemichannel activity being the primary cause of a disease pathology is the Cx26 G45E mutation. The Cx26 G45E mutation was identified in patients with hereditary hearing loss and keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KIDS) and, when expressed Xenopus oocytes or HEK cells, induced hemichannel currents and cell death [18,78,93,94]. The mechanistic basis for the cellular death induced by the Cx26 G45E mutation appears to be the increased Ca2+ permeability of the mutant hemichannel, not a decrease in the [Ca2+]o-sensitive gating of the hemichannel as observed with the A40V mutation [95]. A mouse model of the Cx26 G45E mutation was generated that recapitulated numerous symptoms of KIDS, thus providing a pathophysiological link for this abberant Cx26 hemichannel mutation to the human disease condition [96]. The functional data acquired using this molecule-to-mouse approach provides the strongest evidence that the aberrant hemichannel activity and Ca2+ permeability of the Cx26 G45E mutation is the basis for the disease pathologies associated with KIDS.

Concluding Remarks

Connexins are capable of forming hemichannels that are characterized by possessing a γHC twice that of the measured γj of their respective homomeric gap junction channels, are permeable to monovalent cations, Ca2+, ATP4-, metabolites, fluorescent dyes and molecules up to 500–1,000 Da in molecular weight, are sensitive to the usual lipophilic gap junction uncouplers and cytoplasmic acidification, and increase their open probability with submillimolar [Ca2+]o, positive membrane potentials, and metabolic inhibition. Panx1 channels and P2X7 receptor channels exist in many cell types and distinguishing between them and connexin hemichannels is difficult since they may possess similar nonselective cation conductances and molecular permeabilities to Ca2+, ATP4-, and fluorescent dyes like YO-PRO. Panx1 and connexin hemichannels possess overlapping sensitivities to CBX and mimetic peptides despite the lack of sequence homology, with the possible exception of Gap19 which blocks Cx43 hemichannels but not gap junctions. Panx1 channels are not gated by [Ca2+]o, are activated by caspase-dependent proteolytic cleavage, inhibited by S-nitrosylation, and apparently do not form gap junctions owing to glycosylation of their second extracellular loop. P2X7 channels are also not activated by low [Ca2+]o, but their sensitivity to the natural ATP agonist is enhanced by low external divalent cation concentrations. Perhaps the best way to distinguish between connexin hemichannels and Panx1 or P2X7 channels is pharmacologically since Panx1 channels are specifically inhibited by probenecid and the FD&C Blue #1 (Brilliant Blue FCF, BB FCF) and Brilliant Blue G (BBG) dyes with micromolar and nanomolar sensitivities, respectively. P2X7 channels may also be inhibited by BBG, but are selectively activated by (benzoly)benzoyl ATP (BzATP), reversibly inhibited by A740003 and A438079, and slowly and irreversibly inhibited oxidized ATP (oATP). Many immune and neuronal cell types express connexins, pannexins, and purinergic receptors. So mammalian cell lines used to exogenously express and electrophysiologically study any one of these channels should be screened for endogenous connexin (e.g. Cx43), Panx1, and P2X7 protein expression by real-time PCR and immunoblot assays. Immunohistochemical labeling of cells to detect the presence of gap junctions is the least sensitive assay and may not detect the presence of Cx43 despite an abundance of electrical coupling in HEK293 cells as an example. Electrophysiological assays like patch clamp channel or whole cell voltage clamp recordings are the most sensitive assays since these approaches are able to detect a single open channel. Finally, we estimate that only 1–5% of the wild-type hexameric connexin oligomers exists as a function hemichannel, relative to the abundance of gap junction channels found in those same cells, and that studying connexin hemichannels in isolated cells biases the results in favor of hemichannel formation and may overestimate the functional relevance of their activity in an artificial system where gap junction formation is not possible.

Acknowledgments

We thank Li Gao for technical assistance culturing the HEK293 cells and Jenny J. Yang’s laboratory for providing us with the Cx43 low expressing HEK293(-2) cells. This work was supported NIH grant HL-042220 to RDV and JJY.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Connexin43: a protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2621–2629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Connexin family of gap junction proteins. J Membr Biol. 1990;116:187–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01868459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul DL, Ebihara L, Takemoto LJ, Swenson KI, Goodenough DA. Connexin46, a novel lens gap junction protein, induces voltage-gated currents in nonjunctional plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1077–1089. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sáez JC, Retamal MA, Basilo D, Bukauskas FF, Bennett MVL. Connexin-based gap junction hemichannels: Gating mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1711:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zampighi GA, Loo DDF, Kreman M, Eskandari S, Wright EM. Functional and morphological correlates of connexin50 expressed in Xenopus Laevis oocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:507–524. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donaldson P, Kistler J, Mathias RT. Molecular solutions to mammalian lens transparency. News Physiol Sci. 2001;16:118–123. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.3.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kar R, Batra N, Riquelme MA, Jiang JX. Biological role of connexin intercellular channels and hemichannels. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;524:2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sáez JC, Berthoud VM, Brañes MC, Martínez AD, Beyer EC. Plasma membrane channels formed by connexins: their regulation and functions. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1359–1400. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyer EC, Steinberg TH. Evidence that the gap junction protein connexin-43 is the ATP-induced pore of mouse macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7971–7974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alves LA, Coutinho-Silva R, Persechini M, Spray DC, Savino W, Campos de Carvalho AC. Are there functional gap junctions or junctional hemichannels in macrophages? Blood. 1996;88:328–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chekeni FB, Elliott MR, Sandilos JK, Walk SF, Kinchen JM, Lazarowski ER, Armstrong AJ, Penuela S, Laird DW, Salvesen GS, Isakson BE, Bayliss DA, Ravichandran KS. Pannexin 1 channels mediate ‘find-me’ signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature. 2010;467:863–867. doi: 10.1038/nature09413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanley PJ, Kronlage M, Kirschning C, del Rey A, Di Virgilio F, Leipziger J, Chessell IP, Sargin S, Filippov MA, Lindemann O, Mohr S, Königs V, Schillers H, Bähler M, Schwab A. Transient P2X7 receptor activation triggers macrophage death independent of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4, caspase-1, and pannexin-1 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10650–10663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.332676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Liu TF, Lazrak A, Peracchia C, Goldberg GS, Lampe PD, Johnson RG. Properties and regulation of gap junctional hemichannels in the plasma membranes of cultured cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1019–1030. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John SA, Kondo R, Wang SY, Goldhaber JI, Weiss JN. Connexin-43 hemichannels opened by metabolic inhibition. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:236–240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contreras JE, Sánchez HA, Eugenin EA, Speidel D, Theis M, Willecke K, Bukauskas FF, Bennett MVL, Sáez JC. Metabolic inhibition induces opening of unapposed connexin 43 gap junction hemichannels and reduces gap junctional communication in cortical astrocytes in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012589799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Retamal MA, Cortés CJ, Reuss L, Bennett MVL, Sáez J. S-nitrosylation and permeation through connexin 43 hemichannels in astrocytes: induction by oxidant stress and reversal by reducing agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4475–4480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511118103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ek-Vitorin JF, King TJ, Heyman NS, Lampe PD, Burt JM. Selectivity of connexin 43 channels is regulated through protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2006;98:1498–1505. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227572.45891.2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerido DA, DeRosa AM, Richard G, White TW. Aberrant hemichannel properties of Cx26 mutations causing skin disease and deafness. Am J Physiol Cell Phsyiol. 2007;293:C337–C345. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00626.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beyer EC, Berthoud VM. The family of connexin genes. In: Harris A, Locke D, editors. Connexins: A Guide. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfenniger A, Wohlwend A, Kwak BR. Mutations in connexin genes and disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:103–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laird DW. Closing the gap on autosomal dominantconnexin-26 and connexin-43 mutants linked to human disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2997–3001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruzzone R, Hormuzdi SG, Barbe MT, Herb A, Monyer H. Pannexins: a family of gap junction proteins expressed in brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13644–13649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233464100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baranova A, Ivanov D, Petrash N, Pestova A, Skoblov M, Kelmanson I, Shagin D, Nazarenko S, Geraymovych E, Litvin O, Tiunova A, Born TL, Usman N, Staroverov D, Lukyanov S, Panchin Y. The mammalian pannexin family is homologous to the invertebrate innexin gap junction proteins. Genomics. 2004;83:706–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boassa D, Ambrosi C, Qui F, Dahl G, Gaietta G, Sosinsky G. Pannexin 1 channels contain a glycosylation site that targets the hexamer to the plasmamembrane. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31733–31743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sosinsky GE, Boassa D, Dermietzel R, Duffy HS, Laird DW, MacVicar BA, Naus CC, Penula S, Scemes E, Spray DC, Thompson RJ, Zhao HB, Dahl G. Pannexin channels are not gap junction hemichannels. Channels. 2011;5:193–197. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.3.15765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coddou C, Yan Z, Obsil T, Huidobro-Toro JP, Stojilkovic SS. Activation and regulation of purinergic P2X receptor channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:641–683. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surprenant A, Rassendren F, Kawashima E, North RA, Buell G. The cytolytic P2Z receptor for extracellular ATP identified as a P2X receptor (P2X7) Science. 1996;272:735–738. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Virginio C, MacKenzie A, North RA, Surprenant A. Kinetics of cell lysis, dye uptake and permeability changes in cells expressing the rat P2X7 receptor. J Physiol. 1999;519:335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0335m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klapperstück M, Büttner C, Schmalzing G, Markwardt F. Functional evidence of distinct ATP activation sites at the human P2X7 receptor. J Physiol. 2001;534:25–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1β release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:5071–5082. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locovei S, Scemes E, Qiu F, Spray DC, Dahl G. Pannexin1 is part of the pore forming unit of the P2X7 receptor death complex. FEBS Lett. 2007;582:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albertoa AV, Faria RX, Couto CG, Ferreira LG, Souza CA, Teixeira PC, Froes MM, Alves LA. Is pannexin the pore associated with the P2X7 receptor? Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2013;386:775–787. doi: 10.1007/s00210-013-0868-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browne LE, Compan V, Bragg L, North RA. P2X7 receptor channels allow direct permeation of nanometer-sized dyes. J Neurosci. 2013;333:3557–3566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2235-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bao L, Locovei S, Dahl G. Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Letters. 2004;572:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prochnow N, Hoffman S, Dermietzel R, Zoidl G. Replacement of a single cysteine in the fourth transmembrane region of zewbrafish pannexin1 alters hemichannel gating function. Exp Brain Res. 2009;199:255–264. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kienitz MC, Bender K, Dermietzel R, Pott L, Zoidl G. Pannxen 1 constitutes the large conductance cation channel of cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:290–298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma W, Compan V, Zheng W, Martin E, North RA, Verkhratsky A, Surprenant A. Pannexin 1 forms an anion-selective channel. Pflügers Arch. 2012;463:585–592. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coutinho-Silva R, Persechini PM. P2Z purinoreceptor-associated pores induced by extracellular ATP in macrophages and J774 cells. Am J Physiol (Cell Physiol 42) 1997;273:C1793–C1800. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.6.C1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faria RX, Reis RAM, Casabulho CM, Alberto AVP, de Farias FP, Henriques-Pons A, Alves LA. Pharmacological properties of a pore induced by raising intracellular Ca2+ Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C28–C42. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00476.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebihara L, Liu X, Pal JD. Effect of external magnesium and calcium on human connexin46 hemichannels. Biophys J. 2003;84:277–286. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74848-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trexler EB, Bukauskas FF, Bennett MVL, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. Rapid and direct effects of pH on connexins revealed by the Cx46 hemichannel preparation. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:721–742. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zonta F, Polles G, Zanotti G, Mammano F. Permeation pathway of homomeric connexin 26 and connexin 30 channels investigated by molecular dynamics. J Biomolec Struct Dynamics. 2012;29:985–998. doi: 10.1080/073911012010525027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gómez-Hernández JM, de Miguel M, Larossa B, González D, Barrio LC. Molecular basis of calcium regulation in connexin-32 hemichannels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:16030–16035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2530348100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfahnl A, Dahl G. Gating of Cx46 hemichannels by calcium and voltage. Pflügers Arch – Eur J Physiol. 1999;437:345–353. doi: 10.1007/s004240050788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwon T, Harris AL, Rossi A, Bargiello TA. Molecular dynamic simulations of the Cx26 hemichannel: evaluation of structural models with Brownian dynamics. J Gen Physiol. 2011;138:475–493. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnston MF, Simon SA, Ramon F. Interaction of anesthetics with electrical synapses. Nature. 1980;286:498–500. doi: 10.1038/286498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burt JM, Spray DC. Volatile anesthetics block intercellular communication between neonatal rat myocardial cells. Circ Res. 1989;65:829–837. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burt JM. Uncoupling of cardiac cells by doxyl stearic acids: specificity and mechanism of action. Am J Physiol (Cell Physiol 25) 1989;256:C913–C924. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.4.C913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aylsworth CF, Trosko JE, Welsch CW. Influence of lipids on gap-junction-mediated intercellular communication between Chinese hamster cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 1986;46:4527–4533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guan X, Cravatt BF, Ehring GR, Hall JE, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. The sleep-inducing lipid oleamide deconvolutes gap junction communication and calcium wave transmission in glial cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1785–1792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson JS, Baumgarten IM, Harley EH. Reversible inhibition of intercellular junctional communication by glycyrrhetinic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1986;134:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harks EG, de Roos AD, Peters PH, de Haan LH, Brouwer A, Ypey DL, van Zoelen EJ, Theuvenet AP. Fenamates: a novel class of reversible gap junction channel blockers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:1031–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Srinivas M, Spray DC. Closure of gap junctions by arylaminobenzoates. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1389–1397. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veenstra RD. Physiological modulation of cardiac gap junction channels. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1991;2:168–189. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harris AL. Emerging issues of connexin channels: biophysics fills the gap. Quart Rev Biophys. 2001;34:325–472. doi: 10.1017/s0033583501003705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spray DC, Ye ZC, Ransom BR. Functional connexin “hemichannels”: a critical appraisal. Glia. 2006;54:758–773. doi: 10.1002/glia.20429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Groot JR, Veenstra T, Verkerk AO, Wilders R, Smits JP, Wilms-Schopman FJ, Wiegerinck RF, Bourier J, Belterman CN, Coronel R, Verheijck EE. Conduction slowing by the gap junctional uncoupler carbenoxolone. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bruzzone R, Barbe MT, Jakob NJ, Monyer H. Pharmacological properties of homomeric and heteromeric pannexin hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurochem. 2005;92:1033–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silverman S, Locovei S, Dahl G. Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C761–C767. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00227.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang J, Jackson DG, Dahl G. The food dye FD&C Blue No. 1 is a selective inhibitor of the ATP release channel Panx1. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:649–656. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201310966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang LH, MacKenzie AB, North RA, Surprenant A. Brilliant blue G selectively blocks ATP-gated rat P2X(7) receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donnelly-Roberts DL, Namovic MT, Han P, Jarvis MF. Mammalian P2X7 receptor pharmacology: comparison of recombinant mouse, rat and human P2X7 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1203–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dahl D, Nonner W, Werner R. Attempts to define functional domains of gap junction proteins with synthetic peptides. Biophys J. 1994;67:1816–1822. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80663-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Evans WH, Boitano S. Connexin mimetic peptides: specific inhibitors of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:606–612. doi: 10.1042/bst0290606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang J, Ma M, Locovei S, Keane RW, Dahl G. Modulation of membrane channel currents by gap junction protein mimetic peptides: size matters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;296:C1112–C1119. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00097.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang N, De Bock M, Antoons G, Gadacherla AK, Bol M, Decrock E, Evans WH, Sipido KR, Bulauskas FF, Leybaert L. Connexin mimetic peptides inhibit Cx43 hemichannel opening triggered by voltage and intracellular Ca2+ elevation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:304. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang N, De Vuyst E, Ponsaerts R, Boengler K, Palacois-Prado N, Wauman J, Lai CP, De Bock M, Decrock E, Bol M, Vinken M, Rogiers V, Tavernier J, Evans WH, Naus CC, Bukauskas FF, Sipido KR, Heusch G, Schulz R, Bultynck G, Leybaert L. Selective inhibition of Cx43 hemichannels by Gap19 and its impact on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:309. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0309-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dahl G, Miller T, Paul D, Voellmy R, Werner R. Expression of functional cell-cell channels from cloned rat liver gap junction complementary DNA. Science. 1987;236:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3035715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Veenstra RD, Wang HZ, Westphale EM, Beyer EC. Multiple connexins confer distinct regulatory and conductance properties of gap junctions in developing heart. Circ Res. 1992;71:1277–1283. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.5.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Traub O, Eckert R, Lichtenberg-Fraté H, Elfgang C, Bastide B, Scheidtmann KH, Hülser DF, Willecke K. Immunochemical and electrophysiological characterization of murine connexin40 and -43 in mouse tissues and transfected human cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1994;64:101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barrio LC, Suchyna T, Bargiello T, Xu LX, Roginski RS, Bennett MVL, Nicholson BJ. Gap junctions formed by connexins 26 and 32 alone and in combination are differently affected by applied voltage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8410–8414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eckert R, Dunina-Barkovskaya A, Hülser DF. Biophysical characterization of gap-junction channels in HeLa cells. Pflügers Arch. 1993;424:335–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00384361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rackauskas M, Kreuzberg MM, Pranevicius M, Willecke K, Verselis VK, Bukauskas FF. Gating properties of heterotypic gap junction channels formed of connexins 40, 43, and 45. Biophys J. 2007;92:1952–1965. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scemes E, Bavamian S, Charollais A, Spray DC, Meda P. Lack of “hemichannel” activity in insulin-producing cells. Cell Commun Adhes. 2008;15:143–154. doi: 10.1080/15419060802014255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wicki-Stordeur LE, Dzugalo AD, Swansburg RM, Suits JM, Swayne LA. Pannexin 1 regulates postnatal neural stem and progenitor cell proliferation. Neural Dev. 2012;7:11–21. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thomas P, Smart TG. HEK293 cell line: a vehicle for the expression of recombinant proteins. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2005;51:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stong BC, Chang Q, Ahmad S, Lin X. A novel mechanism for connexin 26 mutation linked deafness: cell death caused by leaky gap junction hemichannels. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:2205–2210. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000241944.77192.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Y, Hao H. Conserved glycine at position 45 of major cochlear connexins constitutes a vital component of the Ca2+ sensor for gating of gap junction hemichannels. Biochim Biophys Res Comm. 2013;436:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sandilos JK, Chiu YH, Chekeni FB, Armstrong AJ, Walk SF, Ravichandran KS, Bayliss DA. Pannexin 1, an ATP release channel, is activated by caspase cleavage of its pore-associated C-terminal autoinhibitory region. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11303–11311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.323378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lohman AW, Weaver JL, Billaud M, Sandilos JK, Griffiths R, Straub AC, Penuela S, Leitinger N, Laird DW, Bayliss DA, Isakson BE. S-nitrosylation inhibits pannexin 1 channel function. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:39602–39612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.397976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sroka J, Czyz J, Wojewoda M, Madeja Z. The inhibitory effect of diphenyltin on gap junctional intercellular communication in HEK293 cells is reduced by thioredoxin reductase 1. Toxicol Letters. 2008;183:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McSpadden LC, Kirkton RD, Bursac N. Electrotonic loading of anisotropic cardiac monolayers by unexcitable cells depends on connexin type and expression level. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C339–C351. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00024.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kirkton RD, Bursac N. Engineering biosynthetic excitable tissues from unexcitable c ells for electrophysiological and cell therapy studies. Nat Commun. 2011;2:300–309. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McSpadden LC, Nguyen H, Bursac N. Size and ionic currents of unexcitable cells coupled to cardiomyocytes distinctly modulate cardiac action potential shape and pacemaking activity in micropatterned cell pairs. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:821–830. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.969329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Manthey D, Willecke K. Transfection and expression of exogenous connexins in mammalian cells. In: Bruzzone R, Giaume C, editors. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 154, Connexin Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2001. pp. 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schachter JB, Sromek SM, Nicholas RA, Harden TK. HEK293 human embryonic kidney cells endogenously express the P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors. Neuropharmacol. 2009;36:1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yan Z, Li S, Liang Z, Tomic M, Stojilkovic SS. The P2X7 receptor channel pore dilates under physiological ion conditions. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:563–573. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu Q, Lin X, Andrews L, Patel D, Lampe PD, Veenstra RD. Histone deacetylase inhibition reduces cardiac Connexin43 expression and gap junction communication. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4 (Apr 15):44. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Veenstra RD. Voltage clamp limitations of dual whole cell recordings of gap junction current and voltage recordings. I Conductance measurements. Biophys J. 2001;80:2231–2247. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zampighi GA. Distribution of connexin50 channels and hemichannels in lens fibers: a structural approach. Cell Commun Adhes. 2003;10:265–270. doi: 10.1080/cac.10.4-6.265.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weingart R. Electrical properties of the nexal membrane studied in rat ventricular cell pairs. J Physiol. 1986;370:267–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Abe S, Usami S-i, Shinkawa H, Kelley PM, Kimberling WJ. Prevalent connexin 26 gene (GJB2) mutations in Japanese. J Med Genet. 2000;37:41–43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Janecke AR, Hennies HC, Günther B, Gansl G, Smolle J, Messmer EM, Utermann G, Rittenger O. GJB2 mutations in keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome including its fatal form. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;133A:128–131. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sánchez HA, Mese G, Srinivas M, White TW, Verselis VK. Differentially altered Ca2+ regulation and Ca2+ permeability in Cx26 hemichannels formed by the A40V and G45E mutations that cause keratitis ichthyosis deafness syndrome. J Gen Physiol. 2010;136:47–62. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mese G, Sellitto C, Li L, Wang HZ, Valiunas V, Richard G, Brink PR, White TW. The Cx26-G45E mutation displays increased hemichannel activity in a mouse model of the lethal form of keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4776–4786. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]