Abstract

Purpose

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, can be leveraged as a surrogate measure of response to therapeutic interventions in medicine. Cysteine aspartic acid-specific proteases, or caspases, are essential determinants of apoptosis signaling cascades and represent promising targets for molecular imaging. Here, we report development and in vivo validation of [18F]4-fluorobenzylcarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone ([18F]FB-VAD-FMK), a novel peptide-based molecular probe suitable for quantification of caspase activity in vivo using positron emission tomography (PET).

Experimental Design

Supported by molecular modeling studies and subsequent in vitro assays suggesting probe feasibility the labeled pan-caspase inhibitory peptide, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK, was produced in high radiochemical yield and purity using a simple two-step, radiofluorination. The biodistribution of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK in normal tissue and its efficacy to predict response to molecularly targeted therapy in tumors was evaluated using microPET imaging of mouse models of human colorectal cancer (CRC).

Results

Accumulation of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK was found to agree with elevated caspase-3 activity in response to Aurora B kinase inhibition as well as a multi-drug regimen that combined an inhibitor of mutant BRAF and a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor in V600EBRAF colon cancer. In the latter setting, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET was also elevated in the tumors of cohorts that exhibited reduction in size.

Conclusions

These studies illuminate [18F]FB-VAD-FMK as a promising PET imaging probe to detect apoptosis in tumors and as a novel, potentially translatable biomarker for predicting response to personalized medicine.

Keywords: cancer, apoptosis, peptide, caspase, PET

Introduction

Cell death proceeds through multiple, mechanistically distinct processes that include necrosis, autophagy, mitotic catastrophe, and apoptosis (1, 2). Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is an orchestrated process that facilitates elimination of unnecessary, damaged, or compromised cells to confer an overall advantage to the host organism. As such, apoptosis is an essential component of embryonic development, tissue homeostasis, and immunological competence. Deviations from normal apoptotic programs are frequently associated with human diseases such as cancer (3). Since many anti-cancer therapies aim to selectively induce apoptosis in tumor cells (4, 5), quantitative, non-invasive imaging biomarkers that reflect apoptosis represent promising tools to improve drug discovery and predict early responses in patients (6-10).

Clinically robust molecular imaging biomarkers of apoptosis have been sought after for many years, but none have yet proven optimal. Classically, molecular imaging measures of apoptosis have relied upon labeled forms of the 36 kDa protein Annexin V, which binds to externalized phosphatidylserine on the plasma membrane of cells undergoing apoptosis (7, 11). Though functionalization of Annexin V for optical (9, 10), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) (12, 13), and positron emission tomography (PET) (14, 15) imaging have been reported, imaging probes based on Annexin V generally suffer from limitations that include suboptimal biodistribution and pharmacokinetics, calcium ion-dependency (16), and a lack of specificity (17-19). Another promising approach that capitalizes upon cell membrane alterations associated with apoptosis utilizes a small molecule known as 18F-ML-10, which has been evaluated in a limited number of patients (20, 21). The strengths and weaknesses of this approach are under investigation at a number of institutions.

Other intracellular molecular targets within the apoptosis signaling cascade represent opportunities for molecular probe development. For example, as regulators of extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis, caspases have been suggested as promising targets for molecular imaging and for drug development (6, 22). The goal of this study was to explore the utility of a peptide-based pan-caspase inhibitor, the modified tripeptide sequence Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (VAD-FMK) (23, 24), to serve as the basis for developing a PET imaging probe for detecting apoptosis. To this end, we report that [18F]4-fluorobenzylcarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone ([18F]FB-VAD-FMK), a novel and potentially translatable molecular probe, enables quantification of caspase activity in vivo using PET imaging. Utilizing small animal microPET imaging of multiple models of human colorectal cancer (CRC), we demonstrate that in vivo tumor accumulation of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK accurately reflects elevated caspase-3 activity in response to Aurora B kinase inhibition as well as a multi-drug regimen that combined an inhibitor of mutant BRAF and a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor. Furthermore, though these studies illuminate [18F]FB-VAD-FMK as a promising tool compound, more generally, these studies suggest that labeled VAD-FMK peptides warrant further development as potential scaffolds for development of translational molecular imaging probes.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Modeling

Co-crystal structures for the caspase-3 protein with an aza-peptide epoxide inhibitor (PDB ID 2CNN) (25) and a covalently bound β-strand peptidomimetic inhibitor (PDB ID 3KJF) (26) were obtained from the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank and used to evaluate the potential of prosthetically labeled VAD-FMK, and deviations thereof, to be accommodated within the active caspase-3 binding domain. Structural alignment of both caspase-3 inhibitor co-crystal structures was performed using PyMOL (Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4, Schrödinger, LLC) to reveal a minor 0.22 angstrom α-carbon protein backbone coordinate root mean squared deviation (RMSD). Both caspase-3 inhibitor-binding sites were treated as energetically equivalent and the smaller β-strand peptidomimetic inhibitor structure (PDB ID 3KJF) was chosen as the starting point for molecular docking calculations. Following removal of the co-crystallized covalent inhibitor ligand, molecular docking was performed using the high resolution, flexible SurflexDock GeomX protocol as implemented in SYBYL-X 2.0 (Tripos International, 1699 South Hanley Rd., St. Louis, Missouri, 63144, USA), with a protomol target based on the β-strand peptidomimetic inhibitor structure with the addition of a 2.0 angstrom bloat parameter. Best scoring energy-minimized docked poses were ranked using the Tripos SYBYL Surflex-Dock flexible protein scoring function, PF-score (Crash parameter) for FB-VAD-FMK, Z-VAD-FMK, IZ-VAD-FMK and VAD-FMK were determined for comparison of physically plausible, low energy minimized conformations in the bound state across the proposed peptide ligand modifications.

Peptide and Derivatives

[19F]FB-VAD-FMK and [127I]IZ-VAD-FMK were synthesized as described in supporting information (SI). VAD-FMK (American Peptide) and Z-VAD-FMK (TOCRIS Bioscience, #2163) were obtained commercially and used without further purification. Relative enzyme selectivity of [19F]FB-VAD-FMK compared to parent peptide was evaluated as described in supporting information (SI). Lipophilicity measurements (LogP7.5) of peptide derivatives were determined analogously to reported methods (27) and described in supporting information (SI).

Biochemical Caspase-3 Inhibition Assay

Caspase-Glo 3/7 (Promega) was employed as a readout of inhibition where by a caspase-cleavable protected luciferase substrate is directly sensitive to caspase-3/7 activity and quantifiable by bioluminescence (28). Caspase inhibitor dissolved in DMSO (0, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000, or 10000 nM) was combined with recombinant human caspase-3 enzyme (C1224-10UG, Sigma) (100 nM) in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in microcentrifuge tubes, vortexed, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After incubation, Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent (Promega) was added in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Solutions were vortexed, incubated for an additional 30 min, and dispensed into opaque wall/bottom 384-well plates (BD Biosciences) for measurement of caspase activity. Sample luminescence was measured using a Synergy 4 plate reader (BioTek).

Cellular Caspase Inhibition Assay

DiFi cells were propagated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Mediatech) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals) and 1 mg/mL gentamycin sulfate (Gibco) in a 95% humidity, 5% CO2, 37°C atmosphere. Cells were seeded as sub-confluent monolayer cultures at a density of 1 × 104 per well into 96-well, black wall/bottom plates (BD Biosciences) and allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37°C. For evaluation of caspase-3/7 inhibition concomitant with drug exposure, DiFi cells were incubated with cetuximab (0.5 μg/mL) for 24 h, based on our experience from previous work (9). Cell media was then replaced with 1× PBS containing inhibitor (0, 10, 100, 1000, 10000 nM) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Inhibition was assessed using Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was quantified using a Synergy 4 plate reader.

Radiotracer Preparation

Detailed chemical and radiochemical methods and characterization can be found in supporting information (SI). The radiochemical intermediate [18F]N-succinimidyl-4-fluorobenzoate ([18F]SFB), was prepared using commercial GE TRACERlab-Synthesizer MX production kits (ABX) with a BIOSCAN Coincidence radiochemistry module. [18F]SFB was then conjugated to VAD-FMK forming [18F]FB-VAD-FMK.

Animal Model

Studies involving animals were conducted in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines. Biodistribution studies were performed using male C57BL/6 mice. A detailed description of in vitro drug response studies that support the subsequently described animal models and drug therapies is provided in the supporting information (SI).

Dual xenograft-bearing mice were sequentially injected with 1 × 107 SW620 and 5 × 106 DLD-1 human CRC cells subcutaneously onto the left or right hind limbs (respectively) of 5- to 6-week old female, athymic nude mice (Harlan Sprague-Dawley). Palpable tumors were observed 2-3 weeks following inoculation. Animals bearing SW620 and DLD-1 xenograft tumors were treated with vehicle or AZD-1152 (25 mg/kg, DMSO) via intraperitoneal injection once daily for five days, analogous to previous work (29). In vivo PET imaging studies were performed on Day 5, approximately 4-6 h after treatment.

COLO-205 and LIM-2405 xenografts were generated by subcutaneously injecting 1 × 107 cells onto the right flank of 5- to 6-week old female, athymic nude mice (Harlan Sprague-Dawley). Palpable tumors were observed within three weeks following inoculation. For BEZ-235 (Selleckchem) and PLX-4720 (synthesized using reported methods) (30) single-agent treatment, animals were administered vehicle, BEZ-235 (35 mg/kg, 0.1% Tween 80 and 0.5% methyl cellulose) or PLX-4720 (60 mg/kg, DMSO) via oral gavage once daily for four days. For BEZ-235 and PLX-4720 combination treatment, BEZ-235 (35 mg/kg, 0.1% Tween 80 and 0.5% methyl cellulose) and PLX-4720 (60 mg/kg, DMSO) were administered via oral gavage as separate doses (respectively) approximately 7-8 h apart. To monitor tumor growth, tumor volumes were measured on Days 1 and 4 of treatment using a previously established ultrasound imaging based methodology (31). In vivo imaging studies were performed on the 4th day (PET), based on our previous experience with BRAF inhibition in vivo (32).

In Vivo PET Imaging and Analysis

Imaging acquisition and processing was performed analogously to our previously reported methods (32). Further details are reported in supporting information (SI).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tumor tissues were harvested immediately following conclusion of imaging, fixed for 24 h in 5% buffered formalin, and blocked in paraffin. Immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, #9664) was carried out as previously described (9). Tissues were stained using standard H&E methods and reviewed by an expert gastrointestinal pathologist (M. Kay Washington). Images displayed are representative of three randomly selected high-power fields (40×). Semi-quantitative IHC analysis was performed using the image processing software ImageJ and is described in supporting information (SI).

Statistical Methods

Unless otherwise stated, experimental replicates are reported as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance of in vitro and in vivo data sets was evaluated using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Differences were assessed within the GraphPad Prism 6.01 software package and considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

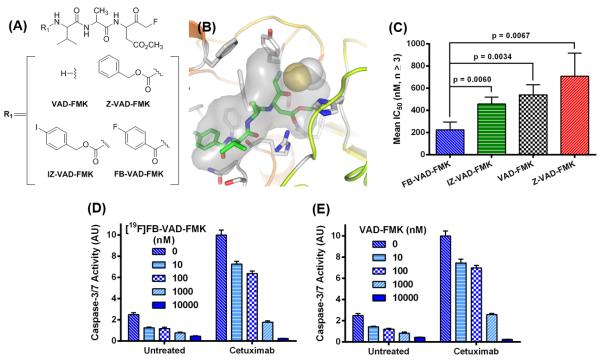

Caspase-3 Active Site Accommodates N-Terminal Functionalization of VAD-FMK

Imaging labels should impart minimal, if any, effects upon the biological and chemical properties of the parent molecule. Given this, we initially used a molecular modeling approach to explore multiple N-terminally functionalized analogues of VAD-FMK (Fig. 1A), two of which would result in PET/SPECT imaging probes: FB-VAD-FMK (Fig. 1B), benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (Z-VAD-FMK), 4-iodobenzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (IZ-VAD-FMK) (33), and VAD-FMK. Molecular docking of each peptide into an irreversible inhibitor bound protein structure of caspase-3 (PDB ID, 3KJF) (26) enabled predictions to be drawn regarding the accommodation of modified peptides into the caspase-3 active site. Flexible docking calculations were performed employing post-docking energy minimization for each peptide to assess potential energetic perturbations that result from N-terminal modification. Only docked poses that positioned the C-terminal fluoro-methyl ketone moiety within 5.0 angstroms of the caspase-3 active site cysteine 163 thiol moiety were considered in our analysis. All four peptides exhibited predicted binding energy scores that fell within the micromolar to nanomolar range (Total Score) and ranked by the steric bump parameter (Crash) using SurflexDock in Tripos SYBYL-X 2.0 (Table S1). The Surflex-Dock scoring term for Polar contacts suggested that the FB-VAD-FMK peptide had greater potential to form hydrogen bonds with active caspase-3 site residues relative to other candidate structures, including the parent peptide, while displaying less internal ligand Strain scores. Of note, IZ-VAD-FMK produced docking scores that reflected a lower-scoring Polar term and demonstrated that more poses buried the larger, lipophilic iodo-moiety toward the protein active site, suggesting greater lipophilicity than FB-VAD-FMK. Though exploratory in nature, these studies suggested both tolerance to functionalization of VAD-FMK at the N-terminus with the FB prosthesis and that the resulting PET imaging probe might possess favorable physical and chemical properties relative to parent peptide and the IZ-labeled form.

Figure 1. Prioritization of FB -modified VAD-FMK peptide caspase inhibitor.

Chemical structures for R1 substitution of VAD-FMK peptide inhibitor scaffold (A). FB-VAD-FMK (green capped sticks) shown docked into the caspase-3 protein structure with covalent inhibitor removed (PDB ID 3KJF); covalent inhibitor protein attachment at Cys163 is shown in yellow and white VDW spheres. Atom colors: oxygen = red; nitrogen = blue; carbon = grey. Grey VDW surfaces indicate the space-filling shape of the covalent bound inhibitor in PDB ID 3KJF (B). Mean IC50 values (n ≥ 3) of inhibition of human recombinant caspase-3 by VAD-FMK and analogues as assessed using a luminescence biochemistry assay-based method (Conc = concentration) (C). Caspase-3/7 inhibition with [19F]FB-VAD-FMK (D) or VAD-FMK (E) in untreated or cetuximab-treated DiFi cells (n = 4).

Enzyme Selectivity of VAD-FMK Peptide Analogues

From the binding mechanism of VAD-FMK-type peptides (23, 34), we anticipated that FB-VAD-FMK would exhibit caspase selectivity similar to that of the parent peptide. To explore this, we evaluated the relative affinity of [19F]FB-VAD-FMK against activated caspases-3/6/7/8 (Fig. S1). Addition of the FB-prosthesis had little impact on caspase selectivity compared to that of the parent peptide, where both peptides inhibited caspases-3/6/7 with single micro molar potency and caspase-8 with slightly greater potency. Caspase-3 was used in subsequent characterization and validation studies as a representative of other relevant caspases.

Lipophilicity of VAD-FMK Peptide Analogues

To validate the predicted physical properties of the labeled VAD-FMK derivatives, lipophilicity studies were undertaken using [19F]FB-VAD-FMK (Fig. S2A), Z-VAD-FMK, and [127I]IZ-VAD-FMK (Fig. S2B). We determined that the FB-modified peptide (logP7.5 = 1.41) was between 50 – 100 times less lipophilic than both Z-VAD-FMK (logP7.5 = 2.20) and [127I]IZ-VAD-FMK (logP7.5 = 2.38), in support of the predicted Polar contact scores determined by molecular modeling. These findings also agree with a previous report of IZ-VAD-FMK, which suggested this compound to be too lipophilic for in vivo use (33).

[19F]FB-VAD-FMK Potently Inhibits Active Caspase Activity

The biological activity of labeled VAD-FMK derivatives was validated with recombinant caspase-3 enzyme using a commercially available chemiluminescent caspase activity assay. Nonlinear regression analysis of the resultant inhibitory profiles yielded a mean (n ≥ 3) fifty-percent inhibitory concentration (IC50) of approximately 225 ± 70 nM for [19F]FB-VAD-FMK (Fig. 1C). Though all peptides exhibited reasonable potencies that were in line with predicted affinities, [19F]FB-VAD-FMK demonstrated the greatest potency towards caspase-3 inhibition. Similar to biochemical analysis, [19F]FB-VAD-FMK inhibited caspase-3/7 activity at nanomolar concentrations analogously to the parent in CRC cells (DiFi) in log-phase growth (Fig. 1D, E). When apoptosis was induced in DiFi cells by exposure to the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab (9), [19F]FB-VAD-FMK inhibited caspase-3/7 activity with comparable efficacy to the parent peptide. Combined with studies demonstrating acceptable physical properties, these investigations illustrated that [19F]FB-VAD-FMK exhibited caspase affinity similar to the parent VAD-FMK peptide and was subsequently prioritized for radiochemical development.

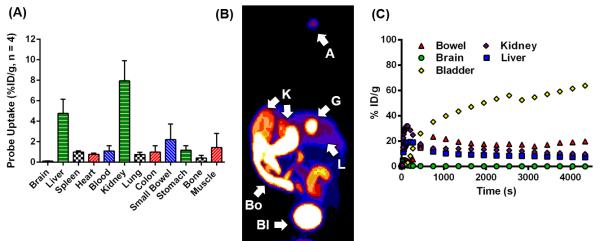

In Vivo Normal Tissue Uptake of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK

Radiochemical preparation of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK (Fig. S3) was performed as described in the supporting information (SI). The in vivo biodistribution of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK was evaluated by ex vivo tissue counting at 60 min post-administration and correlative PET imaging up to 75 min post-administration. Upon intravenous administration, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK was widely distributed throughout a range of normal tissues, with the greatest activity in kidneys and liver after 60 minutes of uptake (Fig. 2A). Very little radioactivity was found in brain, lung, or bone. Summed dynamic PET acquisitions following [18F]FB-VAD-FMK administration, 0 – 75 min (Fig. 2B, C), agreed with tissue counting measurements and provided evidence of renal and hepatobiliary excretion. This was confirmed by HPLC radiometabolite analysis, using a protocol analogous to that described in supporting information (SI) for radiochemical purity analysis, which revealed largely parent compound, approximately 50% or greater, in bile and urine samples (n = 3) at 60 min post injection.

Figure 2. In vivo biodistribution of [19F]FB-VAD-FMK in normal tissue.

Probe biodistribution as assessed from ex vivo tissue count studies in male C57BL/6 mice (n = 4) (A), and a representative PET imaged maximum intensity projection (MIP) (B), A = administration site, Bl = bladder, Bo = bowel, G = gallbladder, K = kidney, L = liver, and corresponding time-activity curves (C) for normal tissues of a non-tumor bearing athymic nude mouse.

[18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET Reflects AZD-1152-dependent Caspase-3 Activity in Tumors

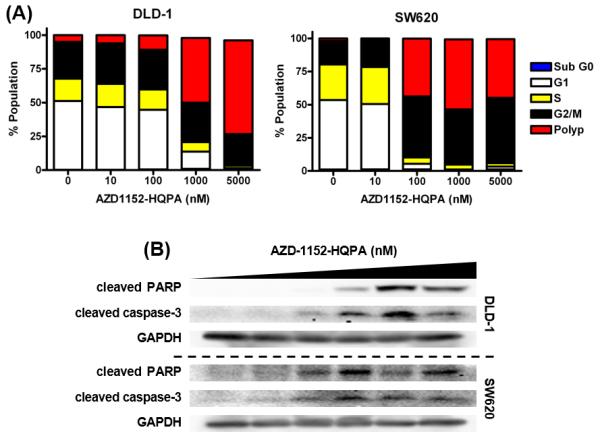

In vivo uptake of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK in tumor was evaluated in SW620 and DLD-1 human CRC cell line xenografts given the in vitro data which demonstrated, in concert with polyploidy (Fig. 3A), AZD-1152-HQPA concentration-dependent increases in cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 levels (Fig. 3B). These results, in addition to previously reported in vivo findings (35), suggest that quantification of caspase activity may reflect response to Aurora B kinase inhibition in these models.

Figure 3. AZD-1152-HQPA in vitro exposure results in cell death in DLD-1 and SW620 cell lines.

Cell cycle analysis by PI flow cytometry (A), caspase-3/7 activity (n = 5) (B), and western blot analysis of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 (C) 24 h post drug administration. Drug concentrations for western blotting were: 0, 10, 100, 500, 1000, or 5000 nM.

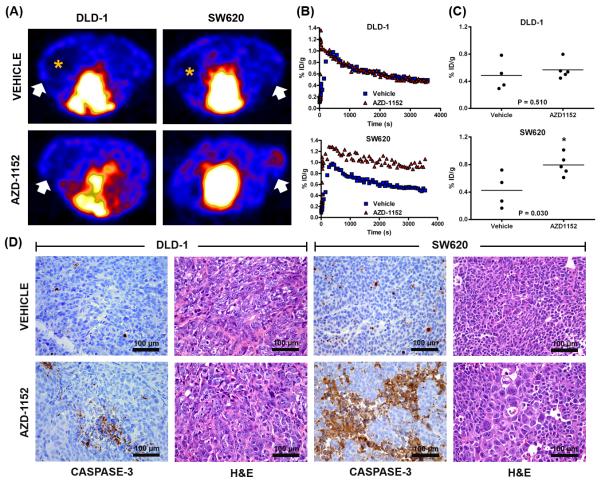

In vivo [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET was explored as a means to reflect response to AZD-1152 compared to vehicle. Animals were treated for five days and subjected to imaging after treatment on the fifth day. While vehicle treatment did not result in significant accumulation of [18F]FB-VAD-FMK in either xenograft model, AZD-1152 treatment increased [18F]FB-VAD-FMK uptake relative to vehicle in SW620 xenografts (0.79 ± 0.15 %ID/g and 0.42 ± 0.25 %ID/g respectively, p = 0.030) (Fig. 4A-C), which was in agreement with in vitro studies. Interestingly, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK uptake was absent in areas of central necrosis, as evident from 3D PET images (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, unlike in vitro studies that illustrated the sensitivity of DLD-1 cells to AZD-1152, probe accumulation was similar between AZD-1152-treated and vehicle-treated DLD-1 xenografts (0.57 ± 0.14 %ID/g and 0.49 ± 0.22 %ID/g respectively, p = 0.510).

Figure 4. [18F]FB-VAD-FMK uptake reflects molecular response to Aurora B kinase inhibition in vivo.

Representative [18F]FB-VAD-FMK transverse PET images of DLD-1/SW620 xenograft-bearing mice treated with vehicle or AZD-1152; tumors denoted by white arrows. Probe accumulation was absent in areas of central necrosis, as denoted by orange asterisks (A). Representative [18F]FB-VAD-FMK time-activity curves for vehicle- and drug-treated DLD-1 and SW620 xenograft tumors. Vehicle- and drug-treated DLD-1 tumors exhibited similar washout, while greater retention in drug-versus vehicle-treated xenografts was observed for SW620 tumors (B). Quantification of tissue %ID/g revealed a statistical significant difference between vehicle- and drug-treated SW620 (p = 0.030) tumors but not for analogously treated DLD-1 tumors (p = 0.510) (C). Representative high-power white-light photo micrographs (40×) of caspase-3 immunohistochemical and H&E stained DLD-1 and SW620 tissues obtained from xenografts collected immediately following imaging (D).

To validate imaging, xenograft tissues were harvested for histology immediately following imaging. In agreement with [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET, caspase-3 immunoreactivity appeared modest in both vehicle-treated SW620 and DLD-1 xenografts (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, AZD-1152 treatment led to elevated caspase-3 immunoreactivity compared to vehicle-treatment in SW620 but not DLD-1 xenografts as verified with semi-quantitative IHC analysis (Fig. S4A). AZD-1152-treated SW620 xenografts demonstrated evidence of drug exposure given the presence of enlarged nuclei evident by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (35). Conversely, the lack of in vivo effects of AZD-1152 in DLD-1 xenografts, predicted by [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET, could possibly be attributed to poor drug exposure as little evidence of polyploidy was observed by H&E staining (Fig. 4D).

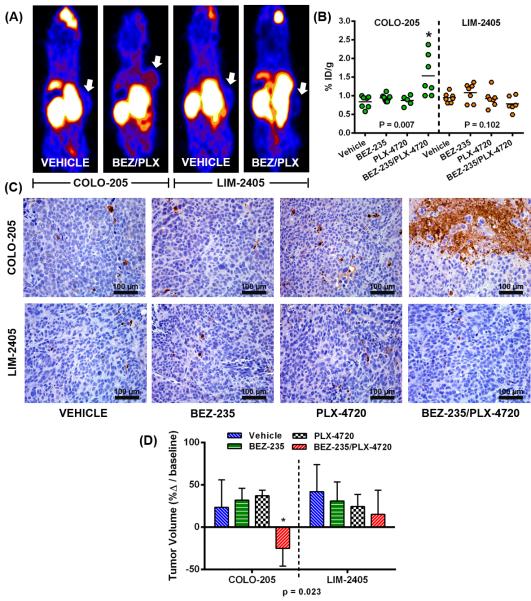

[18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET Reflects Response to Combination Therapy

Rational combination therapy for V600EBRAF melanoma (36, 37) and colon cancer (32) include an inhibitor of mutant BRAF and a PI3K family inhibitor. Leveraging this concept, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK uptake was evaluated in V600EBRAF-expressing CRC xenograft-bearing mice (COLO-205 and LIM-2405) treated with vehicle, single-agent PI3K/mTOR inhibitor (BEZ-235), single-agent BRAF inhibitor (PLX-4720), or combination therapy (BEZ-235/PLX-4720). Animals were imaged by PET after treatment on Day 4. Elevated probe uptake in COLO-205 xenografts, relative to vehicle treatment (0.84 ± 0.16 %ID/g), was observed in the dual-agent-treated cohort (1.54 ± 0.55 %ID/g, p = 0.007) but not for either the BEZ-235 or PLX-4720 single agent cohorts (0.94 ± 0.09 %ID/g, p = 0.14 and 0.87 ± 0.13 %ID/g, p = 0.69, respectively) (Fig. 5A, B). Strikingly, probe uptake in LIM-2405 xenografts was non-differential, relative to vehicle treatment (0.95 ± 0.13 %ID/g), across treatment cohorts: 1.08 ± 0.25 %ID/g, p = 0.22 (BEZ-235), 0.92 ± 0.23 %ID/g, p = 0.81 (PLX-4720), and 0.78 ± 0.20 %ID/g, p = 0.10 (BEZ-235/PLX-4720). Representative xenograft tissue was harvested immediately following imaging. In agreement with [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET, caspase-3 immunoreactivity appeared modest in vehicle- and single-agent-treated COLO-205 and LIM-2405 xenografts, while combination treatment increased caspase-3 immunoreactivity in COLO-205 but not LIM-2405 xenografts (Fig. 5C). These observations were confirmed with semi-quantitative IHC analysis (Fig. S4B). In concert with elevated probe uptake, after four days of treatment a significant reduction in tumor size (p = 0.023) was observed in COLO-205 xenografts treated with combination therapy (Fig. 5D). In contrast, statistically significant changes in tumor growth compared to vehicle were not found for single agent therapies in COLO-205 xenografts or any drug therapies in LIM-2405 cohorts

Figure 5. [18F]FB -VAD-FMK uptake reflects molecular response to combination therapy in vivo.

Representative [18F]FB-VAD-FMK coronal PET images of COLO-205 and LIM-2405 xenograft tumor-bearing vehicle or BEZ-235/PLX-4720-treated mice. Tumors are denoted by white arrows (A). PET quantification of tissue %ID/g revealed a significant difference between vehicle and BEZ-235/PLX-4720-treated COLO-205 (p = 0.007) xenografts but not for analogously treated LIM-2405 xenografts (p = 0.102) (B). Representative high-power white-light photo micrographs (40×) of caspase-3 immunohistochemical stained COLO-205 and LIM-2405 tissues obtained from xenografts collected immediately following imaging (C). Changes in COLO-205 and LIM-2405 tumor volumes by Day 4 of treatment, shown as percent change from Day 1 baseline, revealed a significant difference compared to vehicle-treated mice (p = 0.023) for BEZ-235/PLX-4720-treated COLO-205 tumors only (D).

Discussion

Irreversible caspase binding ligands are frequently utilized as tool compound inhibitors in vitro and in vivo (23, 24). Among the known inhibitors, we sought to extend the utility of VAD-FMK-type peptides to PET imaging probe development. Mechanistically, VAD-FMK peptides irreversibly bind active caspase through condensation of the fluoromethyl ketone moiety with a cysteine thiol, Cys163 for caspase-3, within the active site, permanently inactivating the enzyme (26, 38). As a molecular imaging probe, irreversible binding may confer certain advantages, such as enhanced retention in apoptotic versus healthy cells, due to slow dissociation kinetics. We believe this study is the first to report development and in vivo validation of a novel PET imaging probe derived from the VAD-FMK peptide sequence. In general, the VAD-FMK sequence is known to be quite versatile and has been previously functionalized with fluorophores (39-42) and a radioisotope (33) for in vitro and certain preclinical applications. The probe developed here possesses all of the inherent advantages of a PET imaging agent, which include sensitivity, depth, and quantification (43, 44). Furthermore, the FB derivative exhibits certain physical properties, such as improved water solubility which was a previously reported limitation of another reported labeled peptide IZ-VAD-FMK.

Inhibitor-caspase interactions have been reported (26) and provide reasonable structural templates for the design of inhibitor-based probes. The molecular modeling approaches employed in this study were confirmed by in vitro biochemical studies and suggested that FB-VAD-FMK would be accommodated in the caspase-3 active site without significant perturbation of physically plausible low-energy complex structures. We interpret our results, which identified a best-scoring docked pose for FB-VAD-FMK with the FB-prosthesis pointed away from the active site and towards solvent, to suggest that further chemical modification of the N-terminus may be feasible in an effort to tune the physical properties of the peptide and optimize biodistribution in future studies. These studies suggest that the imaging prosthesis should likely be tuned to match the solvent/protein milieu. In support of the modeling hypothesis, in vitro biochemical and cell assays validated that [19F]FB-VAD-FMK maintained similar potency against caspase-3/7 compared to the parent peptide and exhibited favorable physical properties.

Using established radiochemical methods, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK was produced with activity and purity suitable for use in small animal PET imaging studies. [18F]FB-VAD-FMK was initially evaluated in vivo in two CRC cell line models (SW620 and DLD-1) in response to prodrug (AZD-1152) treatment. Upon conversion to the active form of AZD-1152-HQPA in plasma, AZD-1152-HQPA inhibits Aurora B kinase activity (35, 45) and induces 4N DNA accumulation, endoreduplication, and polyploidy (35). As demonstrated here and elsewhere (29), these events lead to apoptosis-induced cell death and elevated caspase activity in SW620 tumor cells. We demonstrated that [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET could be used to monitor response in this setting and that imaging accurately reflected elevated levels of apoptosis in prodrug-versus vehicle-treated tumors and was validated by immunohistochemistry analysis. Caspase-3 activity corresponded accordingly with evidence of drug exposure as determined by tumor polyploidic events in tissue. Interestingly, in DLD-1 xenografts, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK uptake was not differential between drug-treated and vehicle-treated tumors. Tissues collected from these animals agreed with these findings and revealed little evidence of drug activity, as noted by the absence of polyploidy and caspase-3 activity. Thus, in this model, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET quantization reflected a lack of efficacy that appeared to be the result of poor therapeutic delivery.

Next, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET was used to evaluate response to a multi-drug therapeutic regimen, which included an inhibitor of mutant BRAF and a PI3K/mTOR inhibitor in V600EBRAF-expressing CRC models. A non-invasive imaging metric that can be used to elucidate the basis of response to complicated therapeutic multidrug regimens would be very attractive within the setting of drug development clinical trials. [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET imaging demonstrated that combination therapy led to elevated apoptosis in one of two models compared to vehicle-treated or single-agent-treated CRC xenograft bearing mice. We found that changes in tumor growth closely correlated with levels of caspase activity detected by both [18F]FB-VAD-FMK PET and IHC analysis.

These studies illuminate the potential for caspase-specific PET imaging probes, such as [18F]FB-VAD-FMK, to be utilized in the assessment of early clinical response to therapeutics. A possible limitation of this probe was the relatively modest uptake observed in target tissue responding to therapy (0.8 – 2.5 %ID/g). However, other caspase-targeted PET agents reported in the literature and under clinical development are also known to exhibit modest uptake, including the promising isatin sulfonamide chemical class (46-48) and a PEG-functionalized ‘DEVD-A’ penta-peptide analogue, [18F]-CP18 (49, 50). From the current work, as well as that from previous reports (46-50), it is not clear that improvements in the overall tumor uptake, which might result in greater signal-to-noise ratio, would result in a probe that better reflects the underlying determinants of apoptosis. Future head-to-head comparisons would be beneficial towards sorting this out. Future studies should also evaluate the advantages and limitations inherent in the use of a pan-caspase targeting probe, where extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways are indistinguishable, compared with more selective compound classes.

Conclusion

These studies illuminate the VAD-FMK peptide as a promising scaffold for molecular imaging of caspase activity and response to molecularly targeted therapy using positron emission tomography. Among these peptides, [18F]FB-VAD-FMK appears to be an attractive PET imaging probe for non-invasive quantification of apoptosis in tumors and may represent a potentially translatable biomarker of therapeutic efficacy in personalized medicine.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Deviations from normal cell death programs tend to promote cell survival and are frequently associated with cancer. Many anti-cancer medicines aim to selectively induce cell death in tumor cells, but highly validated non-invasive biomarkers to assess such molecular events are lacking. This study reports a novel positron emission tomography (PET) molecular imaging agent that allows non-invasive, targeted detection of caspase activation and tumor cell death following effective drug treatment. The probe evaluated here was studied within the context of molecularly targeted therapy, but could be equivalently effective to evaluate response to conventional therapeutics and thus used to predict individualized responses in patients and accelerate the development of improved cancer therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Frank Revetta for performing the immunohistochemistry. Donald D. Nolting, Gary L. Johnson and Ronald M. Baldwin are acknowledged for helpful discussions. Md. Imam Uddin is acknowledged for assistance with chemical synthesis and M. Noor Tantawy and George H. Wilson for assistance with PET acquisitions.

Author Financial Support: These studies were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA140628, RC1-CA145138, K25-CA127349, P50-CA128323, P50-CA95103, U24-CA126588, S10-RR17858, R41-MH85768, 5P30 DK058404, R25-CA136440) and the Kleberg Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conception and design: M.R. Hight, H.C. Manning

Development of methodology: M.R. Hight, H.C. Manning

Molecular modeling: E.S. Dawson

Chemistry and radiochemistry: M.R. Hight, Y.Y. Cheung, M.L. Nickels, S. Saleh, J.R. Buck, D. Tang

In vitro and in vivo studies: M.R. Hight, P. Zhao, M.K. Washington

Analysis and interpretation of data: M.R. Hight, H.C. Manning

Writing of the manuscript: M.R. Hight, H.C. Manning

Review/editing/manuscript approval: all authors

Study supervision: H. Charles Manning

References

- 1.Bosman FT, Visser BC, van Oeveren J. Apoptosis: pathophysiology of programmed cell death. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192:676–83. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duprez L, Wirawan E, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Major cell death pathways at a glance. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:1050–62. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang J, Ormerod M, Powles TJ, Allred DC, Ashley SE, Dowsett M. Apoptosis and proliferation as predictors of chemotherapy response in patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:2145–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotter TG. Apoptosis and cancer: the genesis of a research field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:501–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reshef A, Shirvan A, Akselrod-Ballin A, Wall A, Ziv I. Small-molecule biomarkers for clinical PET imaging of apoptosis. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:837–40. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.063917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boersma HH, Kietselaer BL, Stolk LM, Bennaghmouch A, Hofstra L, Narula J, et al. Past, present, and future of annexin A5: from protein discovery to clinical applications. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:2035–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen QD, Challapalli A, Smith G, Fortt R, Aboagye EO. Imaging apoptosis with positron emission tomography: ‘bench to bedside’ development of the caspase-3/7 specific radiotracer [(18)F]ICMT-11. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:432–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manning HC, Merchant NB, Foutch AC, Virostko JM, Wyatt SK, Shah C, et al. Molecular imaging of therapeutic response to epidermal growth factor receptor blockade in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7413–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah C, Miller TW, Wyatt SK, McKinley ET, Olivares MG, Sanchez V, et al. Imaging biomarkers predict response to anti-HER2 (ErbB2) therapy in preclinical models of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4712–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schutters K, Reutelingsperger C. Phosphatidylserine targeting for diagnosis and treatment of human diseases. Apoptosis. 2010;15:1072–82. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0503-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blankenberg FG, Vanderheyden JL, Strauss HW, Tait JF. Radiolabeling of HYNIC-annexin V with technetium-99m for in vivo imaging of apoptosis. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:108–10. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ke S, Wen X, Wu QP, Wallace S, Charnsangavej C, Stachowiak AM, et al. Imaging taxane-induced tumor apoptosis using PEGylated, 111In-labeled annexin V. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:108–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yagle KJ, Eary JF, Tait JF, Grierson JR, Link JM, Lewellen B, et al. Evaluation of 18F-annexin V as a PET imaging agent in an animal model of apoptosis. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:658–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauwens M, De Saint-Hubert M, Devos E, Deckers N, Reutelingsperger C, Mortelmans L, et al. Site-specific 68Ga-labeled Annexin A5 as a PET imaging agent for apoptosis. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:381–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balasubramanian K, Mirnikjoo B, Schroit AJ. Regulated externalization of phosphatidylserine at the cell surface: implications for apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18357–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillon SR, Constantinescu A, Schlissel MS. Annexin V binds to positively selected B cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:58–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balasubramanian K, Schroit AJ. Aminophospholipid asymmetry: A matter of life and death. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:701–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott JI, Surprenant A, Marelli-Berg FM, Cooper JC, Cassady-Cain RL, Wooding C, et al. Membrane phosphatidylserine distribution as a non-apoptotic signalling mechanism in lymphocytes. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:808–16. doi: 10.1038/ncb1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoglund J, Shirvan A, Antoni G, Gustavsson SA, Langstrom B, Ringheim A, et al. 18F-ML-10, a PET tracer for apoptosis: first human study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:720–5. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.081786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen AM, Ben-Ami M, Reshef A, Steinmetz A, Kundel Y, Inbar E, et al. Assessment of response of brain metastases to radiotherapy by PET imaging of apoptosis with (1)(8)F-ML-10. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:1400–8. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blankenberg FG. In vivo detection of apoptosis. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(Suppl 2):81S–95S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Calvo M, Peterson EP, Leiting B, Ruel R, Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Inhibition of human caspases by peptide-based and macromolecular inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32608–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekert PG, Silke J, Vaux DL. Caspase inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:1081–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganesan R, Jelakovic S, Campbell AJ, Li ZZ, Asgian JL, Powers JC, et al. Exploring the S4 and S1 prime subsite specificities in caspase-3 with aza-peptide epoxide inhibitors. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9059–67. doi: 10.1021/bi060364p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Z, Watt W, Brooks NA, Harris MS, Urban J, Boatman D, et al. Kinetic and structural characterization of caspase-3 and caspase-8 inhibition by a novel class of irreversible inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1817–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waterhouse RN, Mardon K, Giles KM, Collier TL, O’Brien JC. Halogenated 4-(phenoxymethyl)piperidines as potential radiolabeled probes for sigma-1 receptors: in vivo evaluation of [123I]-1-(iodopropen-2-yl)-4-[(4-cyanophenoxy)methyl]pip eri dine. J Med Chem. 1997;40:1657–67. doi: 10.1021/jm960720+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren YG, Wagner KW, Knee DA, Aza-Blanc P, Nasoff M, Deveraux QL. Differential regulation of the TRAIL death receptors DR4 and DR5 by the signal recognition particle. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5064–74. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J, Li K, Smith RA, Waterton JC, Zhao P, Chen H, et al. Characterizing tumor response to chemotherapy at various length scales using temporal diffusion spectroscopy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buck JR, Saleh S, Uddin MI, Manning HC. Rapid, Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis of Selective (V600E)BRAF Inhibitors for Preclinical Cancer Research. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:4161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2012.05.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayers GD, McKinley ET, Zhao P, Fritz JM, Metry RE, Deal BC, et al. Volume of preclinical xenograft tumors is more accurately assessed by ultrasound imaging than manual caliper measurements. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:891–901. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.6.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKinley ET, Smith RA, Zhao P, Fu A, Saleh SA, Uddin MI, et al. 3′-Deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine PET predicts response to (V600E)BRAF-targeted therapy in preclinical models of colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:424–30. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.108456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haberkorn U, Kinscherf R, Krammer PH, Mier W, Eisenhut M. Investigation of a potential scintigraphic marker of apoptosis: radioiodinated Z-Val-Ala-DL-Asp(O-methyl)-fluoromethyl ketone. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28:793–8. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00247-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pereira NA, Song Z. Some commonly used caspase substrates and inhibitors lack the specificity required to monitor individual caspase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:873–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson RW, Odedra R, Heaton SP, Wedge SR, Keen NJ, Crafter C, et al. AZD1152, a selective inhibitor of Aurora B kinase, inhibits human tumor xenograft growth by inducing apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3682–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai J, Lee JT, Wang W, Zhang J, Cho H, Mamo S, et al. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3041–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711741105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, Zhang J, Ibrahim PN, Cho H, et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2010;467:596–9. doi: 10.1038/nature09454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rauber P, Angliker H, Walker B, Shaw E. The synthesis of peptidylfluoromethanes and their properties as inhibitors of serine proteinases and cysteine proteinases. Biochem J. 1986;239:633–40. doi: 10.1042/bj2390633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bedner E, Smolewski P, Amstad P, Darzynkiewicz Z. Activation of caspases measured in situ by binding of fluorochrome-labeled inhibitors of caspases (FLICA): correlation with DNA fragmentation. Exp Cell Res. 2000;259:308–13. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amstad PA, Yu G, Johnson GL, Lee BW, Dhawan S, Phelps DJ. Detection of caspase activation in situ by fluorochrome-labeled caspase inhibitors. Biotechniques. 2001;31:608–10. 12, 14. doi: 10.2144/01313pf01. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smolewski P, Bedner E, Du L, Hsieh TC, Wu JM, Phelps DJ, et al. Detection of caspases activation by fluorochrome-labeled inhibitors: Multiparameter analysis by laser scanning cytometry. Cytometry. 2001;44:73–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20010501)44:1<73::aid-cyto1084>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawson VA, Haigh CL, Roberts B, Kenche VB, Klemm HM, Masters CL, et al. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of apoptotic neuronal cell death in a live animal model of prion disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:720–7. doi: 10.1021/cn100068x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson TE, Manning HC. Molecular imaging: 18F-FDG PET and a whole lot more. J Nucl Med Technol. 2009;37:151–61. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.109.062729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eckelman WC, Reba RC, Kelloff GJ. Targeted imaging: an important biomarker for understanding disease progression in the era of personalized medicine. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:748–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mortlock AA, Foote KM, Heron NM, Jung FH, Pasquet G, Lohmann JJ, et al. Discovery, synthesis, and in vivo activity of a new class of pyrazoloquinazolines as selective inhibitors of aurora B kinase. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2213–24. doi: 10.1021/jm061335f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen QD, Smith G, Glaser M, Perumal M, Arstad E, Aboagye EO. Positron emission tomography imaging of drug-induced tumor apoptosis with a caspase-3/7 specific [18F]-labeled isatin sulfonamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16375–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901310106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen DL, Zhou D, Chu W, Herrbrich PE, Jones LA, Rothfuss JM, et al. Comparison of radiolabeled isatin analogs for imaging apoptosis with positron emission tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:651–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen DL, Zhou D, Chu W, Herrbrich P, Engle JT, Griffin E, et al. Radiolabeled isatin binding to caspase-3 activation induced by anti-Fas antibody. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su H, Chen G, Gangadharmath U, Gomez LF, Liang Q, Mu F, et al. Evaluation of [(18)F]-CP18 as a PET imaging tracer for apoptosis. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:739–47. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia CF, Chen G, Gangadharmath U, Gomez LF, Liang Q, Mu F, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the caspase-3 substrate-based radiotracer [(18)F]-CP18 for PET imaging of apoptosis in tumors. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:748–57. doi: 10.1007/s11307-013-0646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.