Abstract

Aging significantly decreases the influenza vaccine-specific response as we and others have previously shown. Based on our previous data in aged mice, we hypothesize that the inflammatory status of the individual and of B cells themselves would impact B cell function. We here show that the ability to generate a vaccine-specific antibody response is negatively correlated with levels of serum TNF-α. Moreover, human unstimulated B cells from elderly make higher levels of TNF-α than those from young individuals and these positively correlate with serum TNF-α levels. These all negatively correlate with B cell function, measured by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), the enzyme of class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation. Only memory B cells (either IgM or switched), but not naïve B cells, make appreciable levels of TNF-α and more in elderly as compared to young individuals. Finally, an anti-TNF-α antibody can increase the response in cultured B cells from the elderly, suggesting that TNF-α secreted by memory B cells affects IgM memory B cells and naïve B cells in an autocrine and/or paracrine manner. Our results show an additional mechanism for reduced B cell function in the elderly and propose B cell-derived TNF-α as another predictive biomarker of in vivo and in vitro B cell responses.

Keywords: Aging, B cells, inflammation, vaccine responses

1. Introduction

Inflammation is a protective response of the individual to cope with both exogenous and endogenous stimuli. In young individuals this response is necessary to protect against infectious diseases and damaging agents. In elderly individuals, however, inflammation can be detrimental and can contribute to the development of age-related chronic diseases typical of old age, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Griffin 2006), atherosclerosis (Libby 2002; Libby 2006), osteoporosis (Kimble and others 1995), type-2 diabetes (Festa and others 2002; Pradhan and others 2001), rheumatoid arthritis (Isaacs 2009), coronary heart disease (Sarzi-Puttini and others 2005).

A low-level chronic inflammatory state is common in the elderly (Franceschi and others 2000a; Franceschi and others 2007). Enhanced IL-6 (Bryl and others 2001; Frasca and others 2013) and TNF-α (Franceschi and others 2000b) plasma levels have been associated with functional disability and mortality of the elderly. The age-related increase in circulating inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and acute phase proteins are markers of the low-grade inflammation observed with aging which has been called “inflammaging” (Franceschi 2007; Franceschi and others 2007). Age-related alterations in responses to immune stimulation, for example chronic T cell stimulation with viruses such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), also contribute to low-grade inflammation by increasing the level of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α (Pawelec and others 2010). Moreover, other cell types such as macrophages, stromal (epithelium and endothelium) and fat cells also produce these mediators in vivo. A direct relationship between age and macrophage activation has been shown and is believed to also contribute to the low-grade inflammatory process in the elderly (Franceschi and others 2000a). Changes in the microbiome as well as increased gut leakage may also be involved (Biagi and others 2011; Biagi and others 2010).

Aging represents a complex remodelling with changes in both innate and adaptive immunity, either decreases or increases in immune functions, leading to a greater susceptibility to infectious diseases and reduced responses to vaccination (Franceschi and others 2000b). In elderly individuals, diseases are more severe than in young individuals and have a greater impact on health outcomes such as morbidity, disability and mortality (Sansoni and others 2008). T cells (Lazuardi and others 2005; Pawelec and others 2009; Vallejo 2005) and innate cells (Panda and others 2010; Solana and others 2006; Sridharan and others 2010) have decreased function with age. However, we have shown that B cells also have intrinsic defects in the elderly, generating sub-optimal antibody response to exogenous antigens and vaccines. These defects include: reduction of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), necessary for class switch recombination (CSR) and somatic hypermutation and reduction in the ability to generate optimal memory B cells (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a; Frasca and others 2008).

Our hypothesis here was that the inflammatory status of the individual and that of B cells themselves would impact B cell function. B cells are affected by cytokines and other factors released by cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Moreover, B cells autonomously express innate immune receptors which recognize exogenous pathogens or the adjuvants used to induce an immune response. Therefore, B cells can either promote immune responses by acting as APC or they can regulate immune responses by secreting immunoregulatory cytokines. Others have shown that human serum TNF-α levels negatively correlate with T cell function (Bryl and others 2001; Parish and others 2009). Published data from our laboratory have shown that unstimulated splenic B cells from old mice make more TNF-α than those from young mice (Frasca and others 2012b). In particular, we have shown that the age-related increase in plasma levels of TNF-α induce TNF-α production by unstimulated B cells, without any antigenic stimulation and that this “pre-activated” phenotype of the B cells renders them incapable of being optimally stimulated by exogenous antigens, mitogens or vaccines (Frasca and others 2012b). We report here that human resting, unstimulated B cells from elderly individuals also make significantly higher levels of TNF-α than those from young subjects, which are positively correlated with serum TNF-α. These both correlate negatively with in vitro B cell function, measured by AID. Moreover, B cell function can be restored by adding an anti-TNF-α antibody to cultured B cells. These findings may help to explain the reduced antibody response of elderly individuals to antigens and vaccines and also provide biomarkers for good responsiveness and crucial targets for development of more effective vaccines. Moreover, the possibility to control inflammaging represents a powerful tool to modulate and counteract the major age-related pathologies in order to target therapeutic interventions and improve health status of the elderly population.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Experiments were conducted using blood isolated from 83 healthy individuals of different ages, 52 young (20–59 years) and 31 elderly (≥60 years), after appropriate signed informed consent and were approved with IRB protocol #20070481. We have previously shown (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2013; Frasca and others 2012a; Khurana and others 2012) that those aged ≥60 had similar characteristics for the markers we measure (AID). We have also previously shown no gender differences in either the young or elderly groups. The individuals for the study were excluded if they had diseases or were taking medications known to alter the immune response. All subjects were influenza-free at the time of enrollment, at the time of blood draws, were without symptoms associated with respiratory infections, and did not contract flu-like symptoms within a 6 month follow-up period.

2.2. Influenza vaccination

The study was conducted during the 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 seasonal influenza vaccination. Two Trivalent Inactivated Vaccines (TIV) were used: Novartis Fluvirin and GSK Fluarix. The two vaccines were given in two different centers at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Both vaccines gave similar results. Blood samples were collected immediately before (t0) and 1 week (t7) after vaccination. The in vivo response to the influenza vaccine was measured by HAI (Hemagglutination inhibition) assay.

2.3. Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay

We evaluated the response to the influenza vaccine by fold-increase in the reciprocal of vaccine-specific titers at t7 divided by that at t0 by HAI assay, as we have previously described (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a). The HAI assay is based on the ability of certain viruses or viral components to hemagglutinate the red blood cells of specific animal species. Antibodies specific to influenza can inhibit this agglutination. Paired pre- and post-immunization serum samples from the same individual were tested simultaneously. Briefly, sera were pretreated with receptor destroying enzyme (RDE, Denke Seiken Co Ltd) for 20 hrs at 37°C; in order to inactivate this enzyme, sera were then heated at 56°C for 60 min. Two-fold serial dilutions were done; 25 µl of diluted sera were incubated with an equal volume of 4 HA units of the vaccine, for 1 hr at room temperature and then 50 µl of a 1.25% suspension of chicken red blood cells were added. After two hrs of incubation at room temperature titers were determined. Serum inhibiting titers of 1/40 or greater are the defined positive measure of seroprotection against infection, whereas a four-fold rise in the reciprocal of the titer from t0 to t7 indicates a positive response to the vaccine and indicates seroconversion (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a; Ito and others 1997; Murasko and others 2002).

2.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

TNF-α in serum was measured by an ELISA kit (Life Technologies KHC3013), following manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. B cell enrichment

PBMC were collected by density gradient centrifugation. Cells were then washed three times with 1X-PBS. B cells were isolated with anti-CD19 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech), according to the MiniMacs protocol (Miltenyi Biotech), briefly by incubation for 20 min at 4°C with 20 µl of beads/107 cells. Cells were then purified using magnetic columns. After isolation, cells were maintained in serum-free medium for 1 hr at 4°C to minimize potential effects of anti-CD19 antibodies on B cell activation.

2.6. B cell culture

B cells were cultured in complete medium (RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% FCS, 10 µg/ml Pen-Strep, and 2×10−5 M 2-ME and 2 mM L-glutamine). B cells (1×106/ml complete medium) were stimulated for 7 days in 24-well culture plates with 1 µg/106 cells of CpG (ODN 2006 In Vivogen). In the experiments with B cell subsets, naïve, IgM memory and switched memory B cells were stimulated for 7 days in 96-well round-bottom culture plates with CpG+F(ab’)2 fragments of goat anti-human Ig (2 µg/ml, Jackson Immunoresearch Labs 109-006-006), at the concentration of 104 cells/200 µl. At the end of this time, cells were harvested, and RNA extracted for quantitative (q)PCR.

2.7. RNA extraction and quantitative (q)PCR

The µMACS mRNA isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) was used. The mRNA was extracted from unstimulated B cells (to evaluate TNF-α) and from stimulated B cells (to evaluate AID). Reactions were conducted in MicroAmp 96-well plates (Life Technologies, ABI N8010560) and run in the ABI 7300 machine. Calculations were made with ABI software. Reagents and primers (Taqman) are from Life Technologies.

2.8. Intracellular staining of TNF-α

One hundred µl of blood were membrane stained for 20 min at 4°C with anti-CD19 (BD 555415) antibody. After staining, red blood cells were lyzed using the RBC Lysing Solution BD PharmLyse (BD 555899), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, cells were fixed, washed with 1X-PBS/5% FCS, permeabilized with 1X-PBS/0.02%Tween 20, followed by cytoplasmic staining with anti-TNF-α (BD 554512). Cells were analyzed within 30 min of staining. Samples were acquired on an LSR-Fortessa and analyzed using FACS Diva software. Gates were set based on isotype control staining (BD 554879).

2.9. Flow cytometry and cell sorting

The following antibodies were used: anti-CD19 (BD 555415), anti-CD27 (BD 555441), anti-IgD (BD 555778) to measure naive (IgD+CD27−), IgM memory (IgD+CD27+) and switched memory (IgD-CD27+) B cells. B cell subsets were sorted on a FACS Aria (BD). Cell preparations were typically >98% pure. After sorting, mRNA was extracted from unstimulated B cell subsets to evaluate TNF-α expression by qPCR. Subsets were also stimulated 7 days (for AID mRNA expression, see above).

2.10. Statistical analyses

Non-parametric analyses of the variables were performed by Mann-Whitney test (two-tailed), whereas correlations were performed by Pearson’s test, using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

3. Results

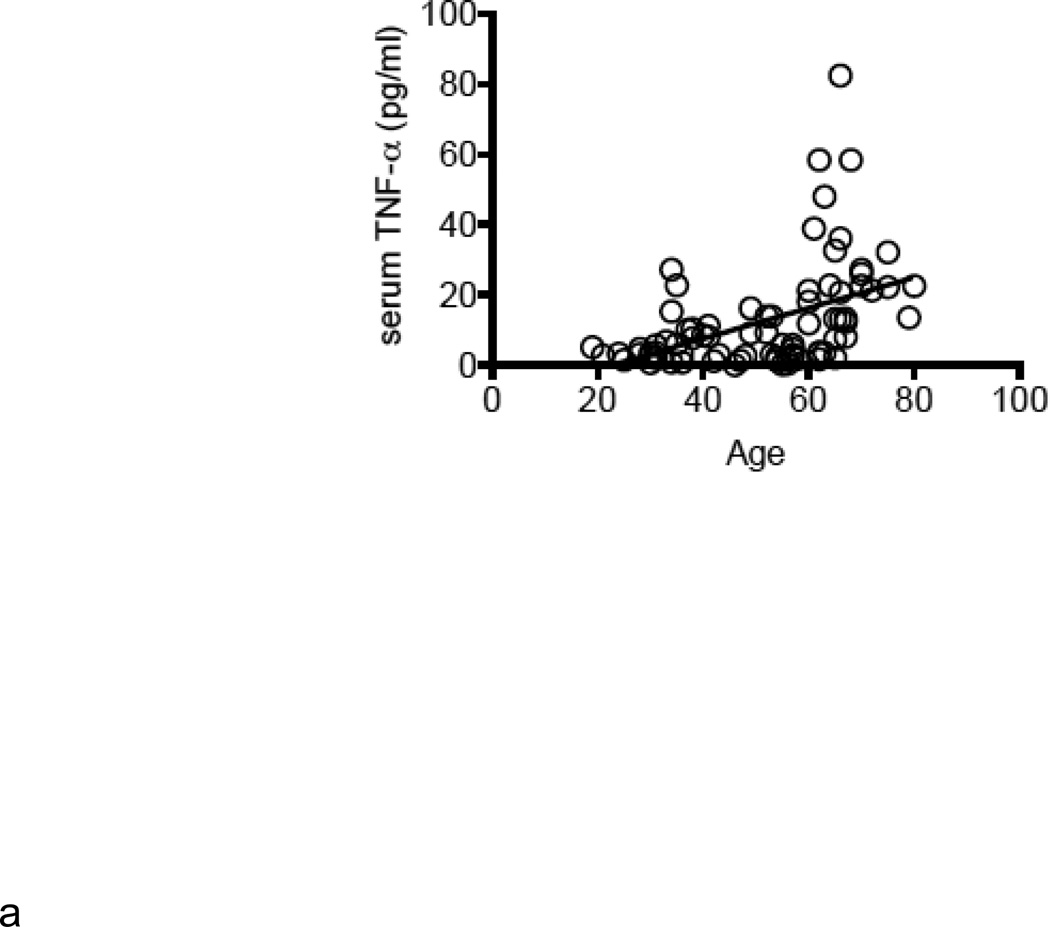

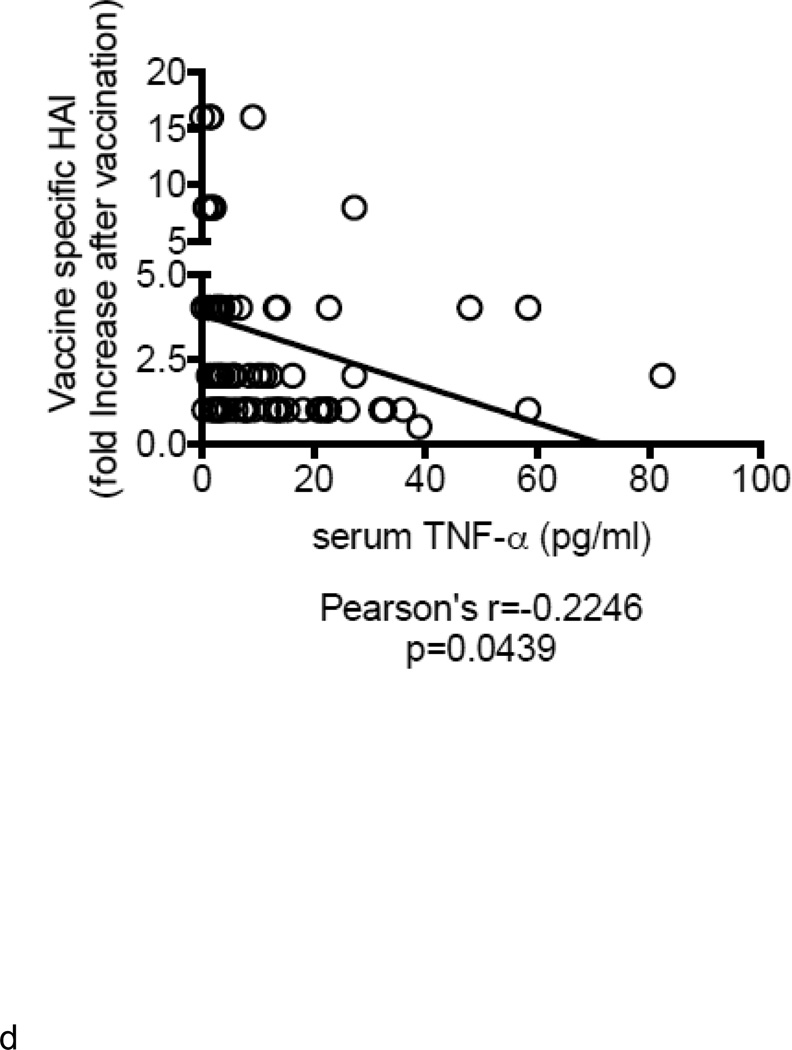

Increased serum TNF-α levels negatively correlate with the in vivo influenza vaccine response

Demographic characteristics of the participants are in Table 1. A total of 83 individuals, 52 young (20–59 years) and 31 elderly (≥60 years), were enrolled in this study during the influenza vaccine seasons 2010–2011 and 2011–2012, where the same vaccine was used. We measured serum TNF-α as marker of inflammaging and showed increased levels of this cytokine in the serum of elderly as compared to young individuals (Fig. 1A) as previously seen (Himmerich and others 2006). We analyzed the in vivo influenza vaccine response by HAI. HAI titers were evaluated at day 0 (t0), day 7 (t7) and day 28 (t28) (before vaccination and 7 or 28 days after vaccination). The peak of the response was at t7. Results (Fig. 1B) show that aging significantly decreases the in vivo vaccine-specific response of elderly as compared to young individuals, as we (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a; Khurana and others 2012) and others (Deans and others 2010; Monto and others 2009; Murasko and others 2002) have previously shown. By the criterion that seroconversion requires a 4-fold increase in titer (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a; Murasko and others 2002) most did not seroconvert. We have reported in previous studies a higher fold-increase after vaccination (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a), at least in young individuals, which was not seen here. We suggest that this was because the vaccine contained for the second (2010–2011) or third (2011–2012) time the same pandemic 2009 H1N1 swine-origin viral antigen and most individuals (78% young and 77% elderly) were protected (had at least a titer of 1/40 at the time of vaccination (t0) (Fig. 1C). Moreover, serum TNF-α levels and HAI were negatively correlated (Fig. 1D). Fig 1D shows that the ability to generate a vaccine response is negatively correlated with levels of serum TNF-α. Although border line of significance, we are in the process of analyzing more samples collected during following vaccine seasons as we want to unequivocally prove this important association that we believe is very important for vaccine responses. Similar results have been seen previously for increased serum TNF-α and correlated with increased T cell deficits in T cells from the elderly (Bryl and others 2001; Parish and others 2009) but our results here will show that deficits in B cells themselves contribute to the decreased response in the elderly and moreover that B cell-derived TNF-α correlates with these humoral deficits.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Young | Elderly | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 52 | 31 |

| Mean age (range) | 41 (19–58) | 67 (60–80)b |

| Gender (M/F) | 20/32 | 20/11 |

| Race (W/B) | 21/31 | 11/20 |

| Ethnic Categories (Hispanic/Non Hispanic) | 30/22 | 10/21 |

| Vaccine history* | 47 | 31 |

Young: 19–59 years, Elderly: ≥60 years

p<0.01,

p<0.05 (Mann-Whitney, two-tailed)

Previously vaccinated with a vaccine containing pH1N1 (swine-origin)

Figure 1. Increased serum TNF-α levels negatively correlate with the in vivo influenza vaccine response.

A. Serum TNF-α levels (pg/ml) from 52 young and 31 elderly individuals was measured by ELISA. Pearson’s r=0.4506, p<0.0001. B. Sera isolated from the same young and elderly individuals, before (t0) and after vaccination (t7), were collected and analyzed by HAI assay to evaluate antibody production to vaccine. Results are expressed as fold-increase in the reciprocal of the titer after vaccination, calculated as follows: reciprocal of titer values after vaccination/ reciprocal of titer values before vaccination. Pearson’s r=−0.2325, p=0.0367. C. HAI results are expressed as reciprocal of the titer after vaccination. Only 11 out of 52 young, 7 out of 31 elderly individuals had a non protective titer (below 1/40) at t0. D. ELISA (to measure serum TNF-α) and HAI (to measure antibody titers) were performed as described above. Pearson’s r=−0.2246, p=0.0439.

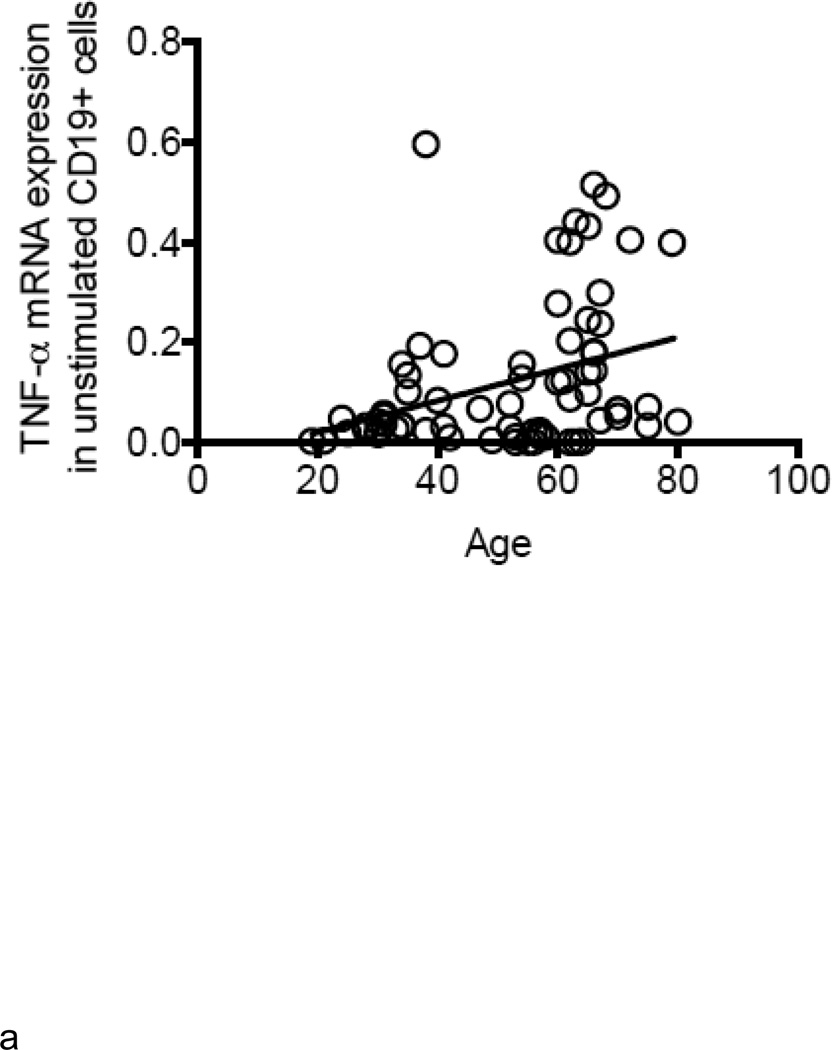

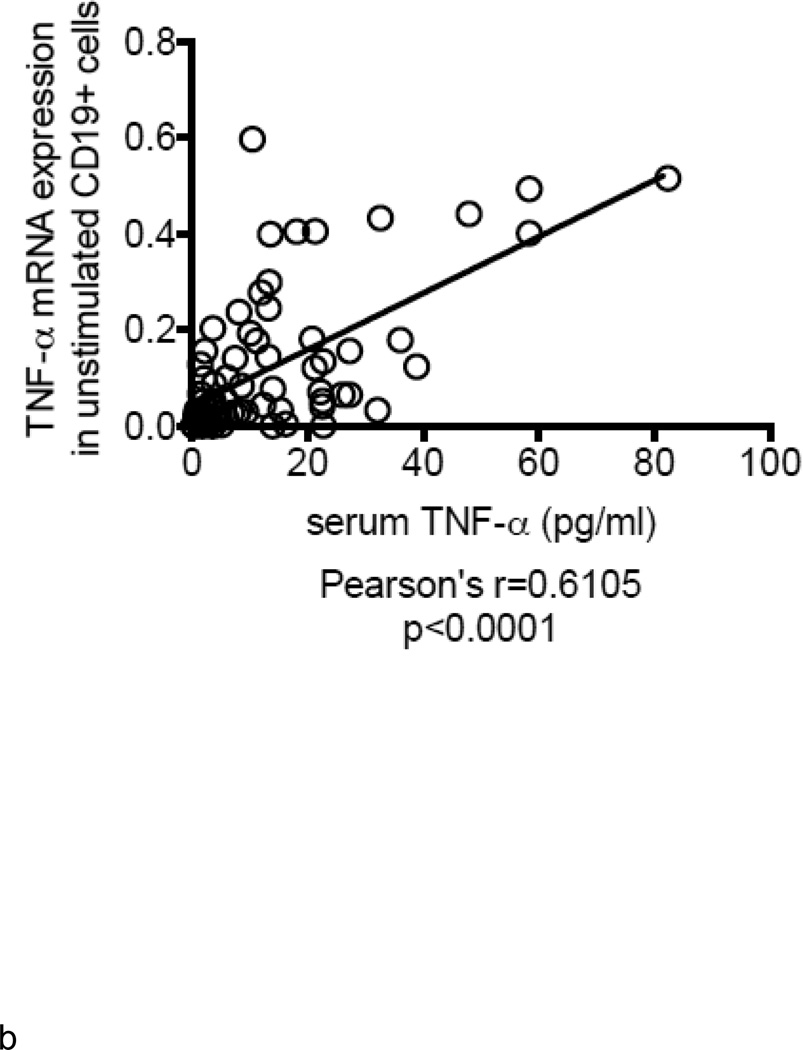

Unstimulated B cells from elderly individuals produce higher amounts of TNF-α mRNA

B cells were isolated from the peripheral blood of young and elderly individuals at t0. The mRNA was extracted from unstimulated B cells at t0 and qPCR performed to measure TNF-α mRNA expression. Results in Fig. 2A show that TNF-α mRNA expression in unstimulated B cells from elderly individuals is 3–4-fold higher as compared to that in B cells from young individuals. TNF-α mRNA expression in unstimulated B cells is positively correlated with serum TNF-α levels (Fig. 2B). In all of the participants (83) in our study, the relative percentages of B cell subsets in young versus elderly were, respectively: 58±6 versus 64±1 (naïve, p<0.05), 25±5 versus 21±2 (IgM memory, p=ns), 6±2 versus 2±0.3 (switched memory, p<0.01), 7±3 versus 13±2 (late/exhausted memory, p<0.01). In a limited number of individuals we also measured TNF-α in unstimulated B cells by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. These individuals were not “selected” but were simply chosen due to logistical problems with flow analysis for some samples. We have previously demonstrated that unstimulated B cells make detectable amounts of TNF-α, although lower than those in monocytes, whereas unstimulated T cells do not make TNF-α at all (Frasca and others 2013). Results in Fig. 2C show more TNF-α protein in unstimulated B cells from elderly individuals, confirming the mRNA results. In order to evaluate which B cell subset was responsible for TNF-α production, we sorted naïve, IgM memory and switched memory B cells from 4 young and 4 elderly individuals at t0 (who had at least 8–10% B cells at t0) (the relative percentages of the subsets in these individuals are in the legend of Fig, 2D). Results in Fig. 2D show that memory B cells (either IgM or switched), but not naïve B cells, make appreciable amounts of TNF-α and more in B cells from elderly as compared to young individuals. These data are the first to show that the different subsets of peripheral B cells make different amounts of TNF-α.

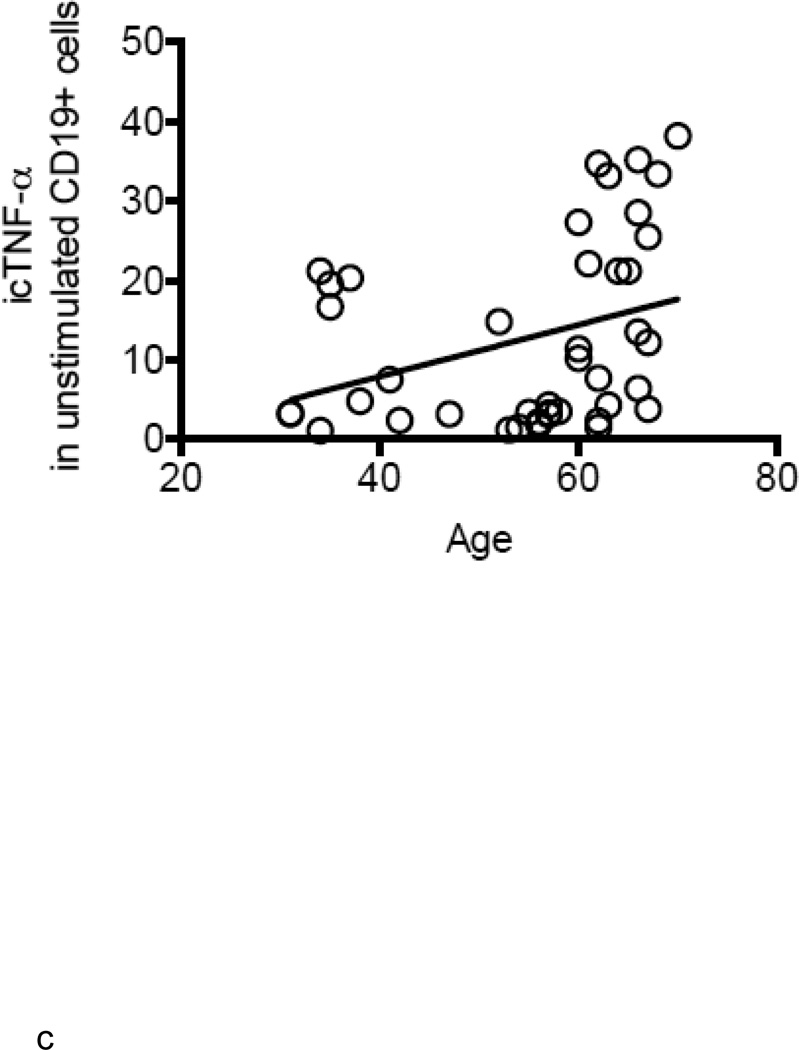

Figure 2. Unstimulated B cells from elderly individuals produce higher amounts of TNF-α mRNA.

A. B cells were isolated from PBMC by magnetic sorting and mRNA extracted to evaluate TNF-α mRNA expression. Results show qPCR values (ΔΔCt) of TNF-α mRNA expression normalized to GAPDH±SE from 52 young and 31 elderly individuals, same as in Fig. 1. Pearson’s r=0.3480, p=0.0026. B. ELISA (to measure serum TNF-α) and qPCR (to measure TNF-α mRNA) were performed as described above. Correlations were performed by Pearson’s test. Pearson’s r=0.6105, p<0.0001. Thirty-five experimental points fall between 10 (X axis) and 0.1 (Y axis). C. One hundred µl of blood at t0 from 21 young and 21 elderly individuals (among those in Fig. 1) were stained. Pearson’s r=0.3345, p=0.0304. D. Naïve, IgM memory and switched memory B cell subsets were sorted. The mRNA was extracted at the end of sorting to evaluate TNF-α mRNA expression. Vertical columns represent the qPCR values (ΔΔCt) of TNF-α mRNA expression normalized to GAPDH±SE from 4 young (white columns) and 4 elderly (black columns) individuals (among those in Fig. 1). The relative percentages of the 4 B cell subsets in these young and elderly individuals are: 32±2 (naïve), 54±11 (IgM memory), 12±2 (switched memory) and 2±1 (late/exhausted memory) in young and 59±4 (naïve), 27±10 (IgM memory), 3±1 (switched memory) and 11±5 (late/exhausted memory) in elderly individuals. Mean comparisons between groups were performed by paired Student’s t test (two-tailed).

Increased TNF-α levels in B cells from elderly individuals correlate with lower B cell response to CpG

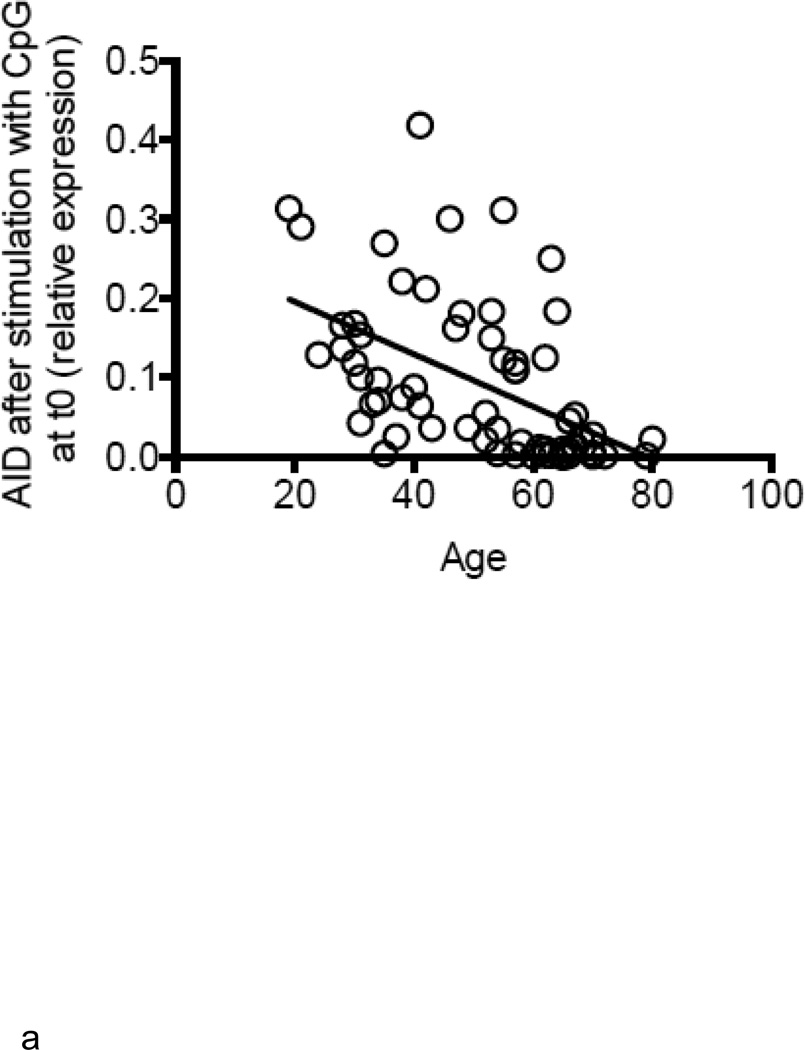

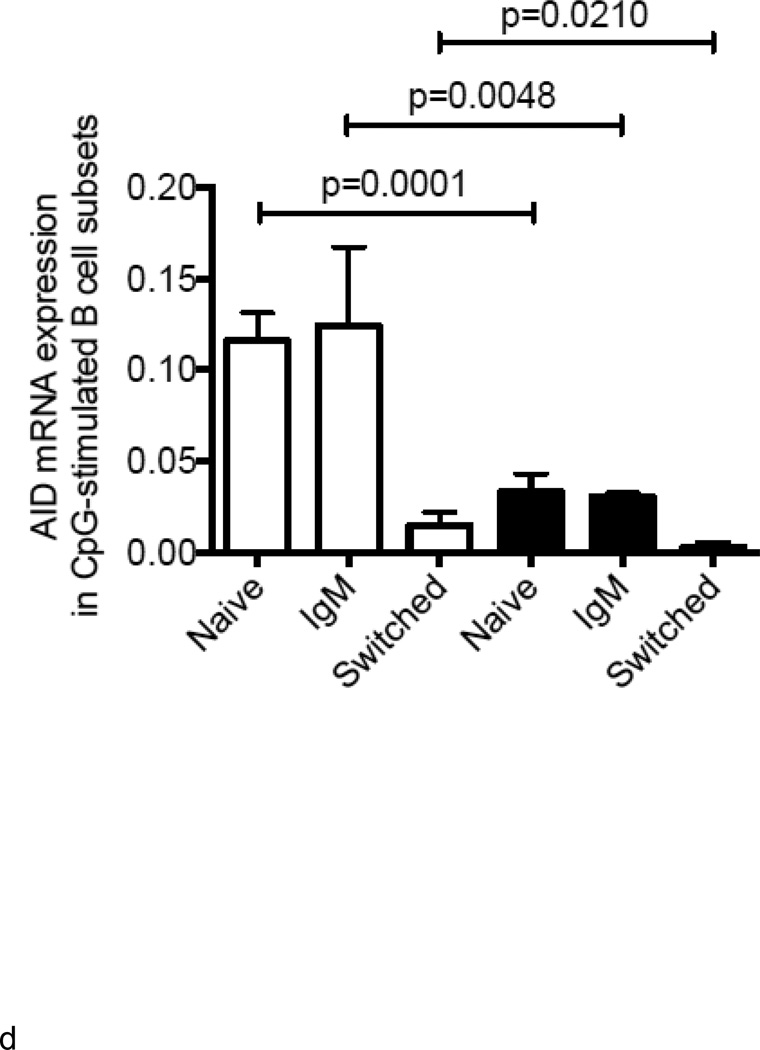

We next measured AID in response to CpG at t0, as we have shown that this is a powerful predictive biomarker of in vivo influenza vaccine responses (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a). Results (Fig. 3A) show that B cells from elderly individuals have significantly less (3 to 4-fold) CpG-induced AID response as compared to those from younger adults and this response is negatively correlated with the levels of TNF-α mRNA in the same B cells before stimulation (Fig. 3B). We have previously demonstrated that AID mRNA expression in response to CpG stimulation at t0 is a good predictive biomarker of the in vivo response. We here confirm those results showing the positive correlation between CpG-AID at t0 and the HAI response measured as fold-increase after vaccination (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that higher TNF-α production by unstimulated B cells from elderly individuals, prior to any stimulation, renders the same B cells incapable of being optimally stimulated by antigens or mitogens. We also measured whether CpG-induced AID mRNA expression in cultures of naïve and IgM memory B cells was negatively correlated with the initial amounts of TNF-α in the same B cell subsets. Naïve and IgM memory B cells are the only B cell subsets capable of in vitro class switch and up-regulating AID (Frasca and others 2008). Results in Fig. 3D show that class switch is reduced in B cells from elderly individuals and we hypothesize that this is due to more TNF-α made in their memory B cells before stimulation (see Fig. 2D and Fig. 4 below). Class switch is also reduced in naïve B cells from the elderly, but we hypothesize that this is mainly due to increased serum TNF-α levels in vivo.

Figure 3. Increased TNF-α levels in B cells from elderly individuals correlate with lower B cell response to CpG.

A. B cells were isolated from PBMC by magnetic sorting at t0. B cells were cultured with CpG for 7 days and then processed as described in Methods. Results are expressed as qPCR values of AID mRNA normalized to GAPDH, as the individuals in this study have comparable percentages of B cells. The is because we selected the elderly with sufficient percentages of B cells in order to perform the sort (7–10%). Every point in the figure is a positive value and we consider 0.1 a predictive biomarker of optimal B cell responses. Pearson’s r=− 0.5129, p<0.0001. B. Correlation between CpG-specific AID mRNA and TNF-α mRNA, both measured at t0, was performed by Pearson’s test. Pearson’s r=−0.2777, p=0.0302. C. HAI (to measure the serum response) and qPCR (to measure AID mRNA) were performed as described. Pearson’s r=0.3754, p=0.0021. D. Naïve, IgM memory and switched memory B cell subsets were sorted as described in Methods. The mRNA was extracted at the end of sorting to evaluate AID mRNA expression after stimulation with CpG. Vertical columns represent the qPCR values (ΔΔCt) of AID mRNA expression normalized to GAPDH±SE from 4 young (white columns) and 4 elderly (black columns) individuals (same individuals in Fig. 2D). Mean comparisons between groups were performed by paired Student’s t test (two-tailed).

Figure 4. Anti-TNF-α Ab increases LPS response in young and more significantly in old cultured B cells.

B cells (106 cells/ml) from 4 young and 4 elderly individuals (among those in Fig. 1) were stimulated with CpG for 7 days. Anti-TNF-α (100 ng/ml/106 cells) antibody was added to B cell cultures since the beginning. The mRNA was extracted and qPCR performed to evaluate expression of AID mRNA. Vertical columns represent the densitometric analyses (arbitrary units) of AID mRNA expression normalized to GAPDH±SE (raw qPCR values). Fold-differences in AID in cultures without and with anti-TNF-α are shown. Young B cell cultures: white (no anti-TNF-α), stripes on white background (plus anti-TNF-α). Old B cell cultures: black (no anti-TNF-α), stripes on black background (plus anti-TNF-α). The relative percentages of the 4 B cell subsets in young individuals are: 38,44,39,46 (naïve); 51,44,49,43 (IgM memory); 8,9,10,8 (switched memory) and 3,3,2,3 (late/exhausted memory) whereas in elderly individuals are: 55,53,56,62 (naïve); 35,37,32,31 (IgM memory); 3,2,3,2 (switched memory) and 7,8,9,5 (late/exhausted memory) in elderly individuals.

Anti-TNF-α Ab increases the LPS response in young and more significantly in old cultured B cells

We then wanted to test whether an anti-TNF-α antibody added at the beginning of B cell culture together with CpG would reverse the negative effects of B cell autonomous TNF-α as we have previously shown in a murine system (Frasca and others 2012b). Results in Fig. 4 show that the anti-TNF-α antibody was able to increase AID mRNA expression in B cell cultures from elderly but not from young individuals. These results suggest that the antibody was able to counteract the effects of high TNF-α levels in B cells from elderly individuals from the beginning of culture, thus allowing them to respond to CpG stimulation in a similar way as that of B cells from young individuals.

4. Discussion

In this study, we show that human ex vivo isolated B cells from elderly individuals make significantly higher levels of TNF-α than those from young subjects, which correlate positively with serum TNF-α. This happens prior to stimulation. Serum TNF-α negatively correlates with the in vivo vaccine response and with the in vitro B cell response to CpG at t0 and therefore we propose TNF-α as a powerful biomarker of vaccine efficacy. Although it has recently been shown that human B cells from young donors can be directly activated via Toll-like receptors or anti-CD40 and BCR cross-linking to secrete TNF-α (Agrawal and Gupta 2011), our results are the first to show that aging increases TNF-α production by B cells before stimulation in vivo or in vitro and we refer to these here as “unstimulated” B cells. Our results strongly support our hypothesis that initial pre-stimulation levels of endogenous TNF-α negatively impact the ability of B cells to generate optimal function.

Another important point of our study is that only the “unstimulated” memory B cells produce TNF-α, more in elderly that in young individuals, and these levels negatively correlate with their in vitro ability to undergo class switch in response to mitogen, similar to what occurs with whole CD19+ B cells. Cytokine production by B cells is a field of increasing interest in aging and in age-associated diseases. Our results herein highlight the differential contribution of B cell subsets to inflammaging. We hypothesize that naïve and memory B cells are programmed to play different roles in the regulation of the immune response, as they release different effector cytokines either before or after stimulation. The fact that only memory B cells (both IgM and switched) make TNF-α suggests a switch in the cytokine program of B cells transitioning from the naïve to the memory phenotype. Moreover, the major memory subset is the IgM memory and the percentage of this population is maintained (Frasca and Blomberg 2011; Frasca and others 2011; Shi and others 2005) during aging, suggesting that this subset significantly contributes to the inflammatory profile of B cells. As to naïve B cells, they have been shown to make the regulatory cytokine IL-10 (Duddy and others 2007). In the present study, we have focused only on the subsets we have already shown to be able to class switch in vitro, e.g. naïve and IgM memory, but we are aware that other minor B cell subsets can be responsible for TNF-α production. Moreover, in the present study, we haven’t sorted the late/exhausted B cell subset, which increases in percentage but not in number with age and has recently been described as a population which may contribute to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the elderly. We cannot exclude the possibility that this is also an effect of global epigenetic changes which accompany aging. We believe that these cells may also contribute to the amount of TNF-α made by B cells and this will affect their capacity to in vitro undergo CSR. Experiments currently performed in our laboratory are addressing this important question. Recent experiments performed in our laboratory in mice have demonstrated the the ABC (age-associated B cells) subset of splenic B cells, which has been considered equivalent to the human late/exhausted memory B cells, make high levels of TNF-α (similar or higher than follicular/naïve, but are incapable of class switch in vitro.

Others have shown that in vitro immunosenescence of T cells is correlated with levels of TNF-α and can be reverted with anti-TNF-α (Parish and others 2009). We have evaluated whether pre-incubation of B cells with anti-TNF-α before stimulation improves B cell responses. Our results show that an anti-TNF-α antibody significantly increases the response in old cultured total B cells, providing a proof of principle that it is possible to improve class switch in elderly individuals by counteracting autocrine TNF-α. We are currently developing other strategies of intervention to rescue the ability of B cells to undergo class switch at least in vitro by pre-incubating B cell cultures with small molecules identified from screening chemical libraries.

Influenza is associated with higher morbidity and mortality in elderly individuals and in those at high risk for complications from influenza because of other co-morbidities (Loerbroks and others 2011). These complications may include secondary bacterial infections, exacerbations of pre-existing medical conditions (Loerbroks and others 2011; Zimmerman and others 2010) and hospitalization which significantly contributes to the development of disability in the elderly (Ferrucci and others 1997) and represent a significant economic burden (Monto and others 2009). Influenza infections are associated with approximately 200,000 estimated hospitalizations and 36,000 deaths each year in the United States (Fiore and others 2010) and more than 90% of all influenza-related deaths occur in elderly individuals. The protective effects of influenza vaccination decrease with age (Goodwin and others 2006; McElhaney 2011; Simonsen and others 2007) but annual vaccinations do increase protection against influenza and help to prevent complications from influenza (Ahmed and others 1995; Keitel and others 1988). However, elderly individuals who have routinely received the vaccine can still contract the infection (Gross and others 1995; Simonsen and others 1998; Vu and others 2002). Therefore, it is important to identify markers that can either monitor or predict the efficacy of vaccine responses. We have already identified B cell-specific biomarkers which can help to monitor and predict the in vivo response to the influenza vaccine. These are switched memory B cells (both the initial level before vaccination and the increase after vaccination) and AID (both the initial level in response to CpG in vitro and the increase after vaccination). These are both decreased by age and are significantly correlated with the in vivo vaccine serum antibody (HAI) response (Frasca and others 2010; Frasca and others 2012a). Results from this study identify TNF-α as another B cell-specific biomarker, which can help to predict the quality of in vivo and in vitro B cell responses. The results of our studies will contribute to prevent infectious diseases and improve the biological quality of life in the elderly.

Highlights.

Aging increases levels of TNF-α in serum and unstimulated B cells

Levels of systemic and B cell TNF-α are positively correlated

Both systemic and B cell TNF-α negatively correlate with B cell function

Only memory B cells, but not naïve B cells, make TNF-α and more in elderly as compared to young individuals

Blocking TNF-α in vitro with specific antibodies significantly increases B cell responses

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH AG-32576 (BBB), NIH 5R21AI096446-02 and 1R21AG042826-01 (BBB and DF). We would like to express our gratitude to the people who participated in this study. We thank the personnel of the Department of Family Medicine and Common Health at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, in particular Dr. Robert Schwartz, chairman; Dr. Sandra Chen-Walta, Employee Health Manager and Evril Antoine, Employee Health RN; and Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core Resource.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- Agrawal S, Gupta S. TLR1/2, TLR7, and TLR9 signals directly activate human peripheral blood naive and memory B cell subsets to produce cytokines, chemokines, and hematopoietic growth factors. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9456-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AE, Nicholson KG, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS. Reduction in mortality associated with influenza vaccine during 1989–90 epidemic. Lancet. 1995;346:591–595. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagi E, Candela M, Franceschi C, Brigidi P. The aging gut microbiota: new perspectives. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:428–429. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagi E, Nylund L, Candela M, Ostan R, Bucci L, Pini E, Nikkila J, Monti D, Satokari R, Franceschi C, Brigidi P, De Vos W. Through ageing, and beyond: gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryl E, Vallejo AN, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Down-regulation of CD28 expression by TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2001;167:3231–3238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans GD, Stiver HG, McElhaney JE. Influenza vaccines provide diminished protection but are cost-saving in older adults. Journal of internal medicine. 2010;267:220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duddy M, Niino M, Adatia F, Hebert S, Freedman M, Atkins H, Kim HJ, Bar-Or A. Distinct effector cytokine profiles of memory and naive human B cell subsets and implication in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2007;178:6092–6099. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Pahor M, Corti MC, Havlik RJ. Hospital diagnoses, Medicare charges, and nursing home admissions in the year when older persons become severely disabled. JAMA. 1997;277:728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa A, D'Agostino R, Jr, Tracy RP, Haffner SM Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis, S. Elevated levels of acute-phase proteins and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 predict the development of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes. 2002;51:1131–1137. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler GL, Singleton JA, Iskander JK, Wortley PM, Shay DK, Bresee JS, Cox NJ. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C. Inflammaging as a major characteristic of old people: can it be prevented or cured? Nutr Rev. 2007;65:S173–S176. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, De Benedictis G. Inflammaging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000a;908:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, Giunta S, Olivieri F, Sevini F, Panourgia MP, Invidia L, Celani L, Scurti M, Cevenini E, Castellani GC, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Valensin S, Bonafe M, Paolisso G, Yashin AI, Monti D, De Benedictis G. The network and the remodeling theories of aging: historical background and new perspectives. Exp Gerontol. 2000b;35:879–896. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Blomberg BB. Aging affects human B cell responses. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:430–435. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9501-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Blomberg BB. Age effects on B cells and humoral immunity in humans. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:330–335. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Phillips M, Lechner SC, Ryan JG, Blomberg BB. Intrinsic defects in B cell response to seasonal influenza vaccination in elderly humans. Vaccine. 2010;28:8077–8084. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Mendez NV, Landin AM, Ryan JG, Blomberg BB. Young and elderly patients with type 2 diabetes have optimal B cell responses to the seasonal influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Phillips M, Mendez NV, Landin AM, Blomberg BB. Unique biomarkers for B-cell function predict the serum response to pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine. Int Immunol. 2012a;24:175–182. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Landin AM, Lechner SC, Ryan JG, Schwartz R, Riley RL, Blomberg BB. Aging downregulates the transcription factor E2A, activation-induced cytidine deaminase, and Ig class switch in human B cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5283–5290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Romero M, Diaz A, Alter-Wolf S, Ratliff M, Landin AM, Riley RL, Blomberg BB. A Molecular Mechanism for TNF-alpha-Mediated Downregulation of B Cell Responses. J Immunol. 2012b;188:279–286. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24:1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS. Inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:470S–474S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.470S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross PA, Hermogenes AW, Sacks HS, Lau J, Levandowski RA. The efficacy of influenza vaccine in elderly persons. A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:518–527. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-7-199510010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmerich H, Fulda S, Linseisen J, Seiler H, Wolfram G, Himmerich S, Gedrich K, Pollmacher T. TNF-alpha, soluble TNF receptor and interleukin-6 plasma levels in the general population. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs JD. Therapeutic agents for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:1463–1475. doi: 10.1517/14712590903379494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Suzuki Y, Mitnaul L, Vines A, Kida H, Kawaoka Y. Receptor specificity of influenza A viruses correlates with the agglutination of erythrocytes from different animal species. Virology. 1997;227:493–499. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keitel WA, Cate TR, Couch RB. Efficacy of sequential annual vaccination with inactivated influenza virus vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:353–364. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana S, Frasca D, Blomberg B, Golding H. AID activity in B cells strongly correlates with polyclonal antibody affinity maturation in-vivo following pandemic 2009-H1N1 vaccination in humans. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002920. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble RB, Matayoshi AB, Vannice JL, Kung VT, Williams C, Pacifici R. Simultaneous block of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor is required to completely prevent bone loss in the early postovariectomy period. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3054–3061. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.7.7789332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazuardi L, Jenewein B, Wolf AM, Pfister G, Tzankov A, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Age-related loss of naive T cells and dysregulation of T-cell/B-cell interactions in human lymph nodes. Immunology. 2005;114:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:456S–460S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.456S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loerbroks A, Stock C, Bosch JA, Litaker DG, Apfelbacher CJ. Influenza vaccination coverage among high-risk groups in 11 European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2011;22:562–568. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney JE. Influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto AS, Ansaldi F, Aspinall R, McElhaney JE, Montano LF, Nichol KL, Puig-Barbera J, Schmitt J, Stephenson I. Influenza control in the 21st century: Optimizing protection of older adults. Vaccine. 2009;27:5043–5053. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murasko DM, Bernstein ED, Gardner EM, Gross P, Munk G, Dran S, Abrutyn E. Role of humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection from influenza disease after immunization of healthy elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:427–439. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda A, Qian F, Mohanty S, van Duin D, Newman FK, Zhang L, Chen S, Towle V, Belshe RB, Fikrig E, Allore HG, Montgomery RR, Shaw AC. Age-associated decrease in TLR function in primary human dendritic cells predicts influenza vaccine response. J Immunol. 2010;184:2518–2527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish ST, Wu JE, Effros RB. Modulation of T lymphocyte replicative senescence via TNF-{alpha} inhibition: role of caspase-3. J Immunol. 2009;182:4237–4243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelec G, Akbar A, Beverley P, Caruso C, Derhovanessian E, Fulop T, Griffiths P, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Hamprecht K, Jahn G, Kern F, Koch SD, Larbi A, Maier AB, Macallan D, Moss P, Samson S, Strindhall J, Trannoy E, Wills M. Immunosenescence and Cytomegalovirus: where do we stand after a decade? Immun Ageing. 2010;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Larbi A, Strindhall J, Wikby A. Cytomegalovirus and human immunosenescence. Rev Med Virol. 2009;19:47–56. doi: 10.1002/rmv.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansoni P, Vescovini R, Fagnoni F, Biasini C, Zanni F, Zanlari L, Telera A, Lucchini G, Passeri G, Monti D, Franceschi C, Passeri M. The immune system in extreme longevity. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Doria A, Iaccarino L, Turiel M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, biologic agents and cardiovascular risk. Lupus. 2005;14:780–784. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2220oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Yamazaki T, Okubo Y, Uehara Y, Sugane K, Agematsu K. Regulation of aged humoral immune defense against pneumococcal bacteria by IgM memory B cell. J Immunol. 2005;175:3262–3267. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Schonberger LB, Arden NH, Cox NJ, Fukuda K. Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:53–60. doi: 10.1086/515616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Viboud C, Miller MA, Jackson LA. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people: an ongoing controversy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:658–666. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solana R, Pawelec G, Tarazona R. Aging and innate immunity. Immunity. 2006;24:491–494. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan A, Esposo M, Kaushal K, Tay J, Osann K, Agrawal S, Gupta S, Agrawal A. Age-associated impaired plasmacytoid dendritic cell functions lead to decreased CD4 and CD8 T cell immunity. Age (Dordr) 2010;33:363–376. doi: 10.1007/s11357-010-9191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo AN. CD28 extinction in human T cells: altered functions and the program of T-cell senescence. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:158–169. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T, Farish S, Jenkins M, Kelly H. A meta-analysis of effectiveness of influenza vaccine in persons aged 65 years and over living in the community. Vaccine. 2002;20:1831–1836. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RK, Lauderdale DS, Tan SM, Wagener DK. Prevalence of high-risk indications for influenza vaccine varies by age, race, and income. Vaccine. 2010;28:6470–6477. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]