Abstract

Background

The current FDA-approved time interval between plerixafor dosing and apheresis initiation is ~ 11 hours, but this time interval is impractical for most care providers. Few studies have examined mobilization kinetics beyond 11 hours in multiple myeloma (MM) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) patients. Therefore this study’s intent was to analyze an interval of 17–18 hours between plerixafor dosing and apheresis initiation.

Study Design and Methods

In 11 patients with MM or NHL, plerixafor 240 ug/kg was administered at 5pm on day 4 of G-CSF mobilization. Peripheral blood (PB) CD34+ and CD34+CD38− concentrations were enumerated every 2 hours until 7 AM and immediately pre-apheresis on day 5, for a total interval time of 17–18 hours post-plerixafor. Data was analyzed useing mixed model analysis of repeated measures and paired t-testing.

Results

Ten of the 11 subjects achieved a CD34+ product count of >2 × 106/kg with a single leukapheresis. All 10 had a pre-plerixafor PB CD34+ concentration of at least 10/uL. PB CD34+ concentrations were not different between 10–18 hours post-plerixafor (p≈0.8). In contrast, PB CD34+CD38− concentrations significantly increased from 10 to 18 hours post-plerixafor (p=0.03).

Conclusions

In MM and NHL patients with adequate pre-plerixafor CD34+ concentrations, leukapheresis initiated 14–18 hours after plerixafor/G-CSF mobilization may not impair adequate CD34+ collection and may increase more primitive CD34+CD38− collection. In this subset of patients, late afternoon dosing of plerixafor at 5 pm with initiation of next-day apheresis as late as 11 am appears feasible without loss of efficacy.

Keywords: plerixafor; hematopoietic stem cell mobilization; pharmacodynamics; Antigens, CD34; Antigens, CD38; Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

Introduction

Plerixafor (Mozobil, Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) is approved for hematopoietic progenitor cell (HPC) mobilization into peripheral blood (PB) in combination with granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in patients with multiple myeloma (MM) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) (1, 2). Plerixafor reversibly inhibits binding of stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) to its cognate chemokine receptor CXCR4. Dosing is approved at approximately 11 hours (hr) prior to apheresis initiation, preferably in a health care setting due to the risk of an adverse hypotensive reaction. Since apheresis facilities typically open at 8–9 AM, the approved 11 hr interval requires plerixafor dosing between 9–10 pm, impractical unless the patient self-administers the drug.

Prior studies suggest that PB CD34+ concentration ([CD34+]) may be maintained. Pharmacodynamic studies in normal volunteers given plerixafor alone (3), and MM and NHL patients given G-CSF and plerixafor (4, 5), generally show increasing PB [CD34+] out to 10–11 hr after plerixafor. A retrospective study of 48 primarily MM and NHL patients, collected 15 hr after 5pm plerixafor, found that 47 patients reached ≥ 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg with a median 2 days of apheresis (6). Recently, 22 of 31 MM patients prospectively collected ~17 hr after plerixafor reached ≥ 10 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg with 1 large volume leukapheresis (7).

In 3 normal volunteers given G-CSF and plerixafor, the peak PB [CD34+] was at 14 hr but was sustained until 18 hours after dosing (8). The 18 hr peak was 3 times that seen with G-CSF alone, comparable to a 2.9 fold peak over G-CSF alone at 6 hr post-plerixafor (9) and a 2.5 fold peak over G-CSF alone at 10 hr post-plerixafor (10). A prospective study of 13 known poor mobilizers, however, found that, in 4 patients who had PB [CD34+] followed out to 14–15 hr, the [CD34+] at that time was significantly decreased from the earlier peak [CD34+] (11).

Studying, in the target population of MM and NHL patients, a total interval time of 17–18 hr post-plerixafor is important because, in practical terms, the actual leukapheresis may not be initiated until 10–11 AM. Furthermore, even if initiated earlier between 8–9 AM, a standard leukapheresis of 3 total blood volumes typically lasts 3 hr. Therefore, it is important to rule out a significant decrease in PB [CD34+] extending through this interval.

Materials and Methods

This was a single-center, prospective cohort IRB-approved study in 11 patients with NHL and MM who underwent HPC mobilization as part of standard care at Mount Sinai Medical Center from March 2010 to October 2011. Written and informed consent was obtained on all subjects. Patients were required to meet the same entry criteria specified in the initial studies that led to FDA approval, which notably excluded patients who had failed previous HPC collections or collection attempts (1, 2). Baseline PB [CD34+] prior to starting G-CSF was assessed with two separately collected samples (Figure 1). Donors then received once daily morning subcutaneous G-CSF (Neupogen, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) at 10 ug/kg for 5 days. On the 4th day of G-CSF, subcutaneous plerixafor at 240 ug/kg was administered at 5pm and patients were admitted overnight to the Clinical Research Center at Mount Sinai. Immediately pre-plerixafor (5 pm on day 4), every subsequent 2 hours until 7 AM of day 5, and then between 10–11 AM (the initiation of apheresis), 4 ml of PB was drawn through a 20-gauge angiocath attached to a medlock for CD34+ and CD34+CD38− enumeration. Samples were drawn after discard of 2 mL of PB, and run using standard technique (Stem-Kit, CD38 Ab, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) in the clinical flow cytometry laboratory. Leukapheresis was performed if the 7 am peripheral blood CD34+ concentration was at least 10/uL. Approximately 3 total blood volumes using the manufacturer’s Mononuclear Cell procedure of the COBE Spectra apheresis device (Version 6.1, Terumo BCT, Lakewood, CO) were processed on each day of collection in all donors.

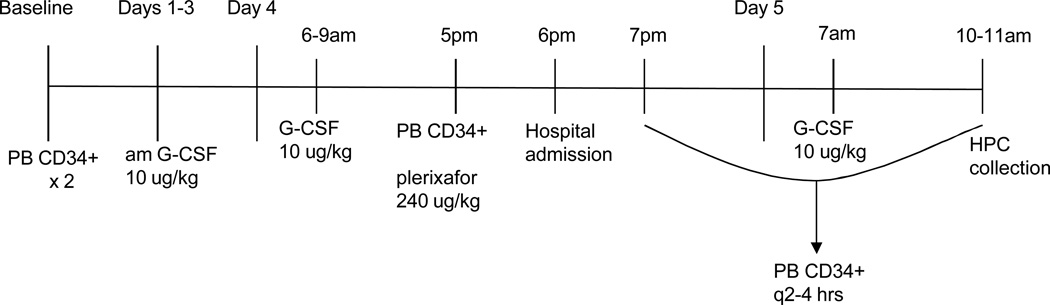

Figure 1.

Clinical study design. Peripheral blood for [CD34+] / [CD34+CD38−] was drawn every 2 hours from 5pm, Day 4 to 7am, Day 5; and then immediately prior to the initiation of apheresis at 10–11AM. Day 5 G-CSF was administered after the blood draw. PB=peripheral blood, HPC= hematopoietic progenitor cell.

Neutrophil engraftment was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days in which the absolute neutrophil count is > 500 cells/µL. Platelet engraftment was defined as the first of 7 days in which the platelet count is > 20,000/µL without transfusion. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) common toxicity criteria (CTCAE). Statistical analysis was performed, using paired t-testing and mixed model analysis of repeated measures, using the following software: Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation), SPSS Statistics 18 (IBM Corporation), and SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Corp).

Results

Eleven patients with MM or NHL signed consent for this study (Table 1). There were no drop outs. 5 patients had received prior cycles of lenalidomide (range 3–9). Average absolute baseline PB [CD34+] and [CD34+CD38−] were 3/uL (range 0–8/uL) and 0.1/uL (range 0–1), respectively. All patients except subjects #5 and #7, who had NHL and had received salvage chemotherapy, mobilized well even pre-plerixafor with a day 4, 5 pm PB [CD34+] > 10/uL. Subject #5, whose pre-plerixafor PB [CD34+] was exactly 10/uL, collected just above the minimum of > 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg and, in retrospect, had failed to meet entry criteria with a platelet count of 70,000/uL rather than the requisite > 100,000/uL. Subject #7 was not collected due to PB [CD34+] < 10/uL. He was, in retrospect, a poor mobilizer, who subsequently failed a collection with G-CSF alone and then underwent chemotherapy plus G-CSF mobilization, requiring 2 consecutive procedures to achieve a combined CD34+ product count of 2.63 × 106/kg.

Table 1.

Summary of Autologous Donor Characteristics

| Subject | Age, gender, diagnosis* |

Last chemotherapy/ Past lenalidomide (# cycles) |

Other active medical problems† |

Pre-plerixafor PB [CD34+]/ [CD34+CD38−] |

Day 5 10–11am PB [CD34+]/ [CD34+CD38−] |

Day 5 Product CD34+ × 106/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 M, MM | Primary /yes (6) | DM Type II | 20/ND | 80/16 | 6.53 |

| 2 | 58 M, MM | Primary | None | 88/9 | 158/49 | 18.44 |

| 3 | 60 M, MM | Primary/yes (3) | None | 30/7 | 145/39 | 11.87 |

| 4 | 54 M, MM | Primary | None | 73/7 | 142/36 | 13.37 |

| 5 | 61 F, DLBCL | 1st salvage | DM Type II High cholesterol Hypertension | 10/1 | 24/3 | 2.14 |

| 6 | 51 F, MM | Primary/yes (5) | DLCO 61% | 30/2 | 126/1 | 9.89 |

| 7 | 63 M, DLBCL | 1st salvage | DM Type II Hypertension Hepatitis C | 1/1 | 3/1 | Not collected |

| 8 | 49 F, MM | Primary | DLCO 47% | 25/1 | 171/5 | 14.55 |

| 9 | 59 F, MM | Primary/yes (9) | DM Type II Hypertension Asthma | 76/26 | 201/129 | 21.32 |

| 10 | 54 M, MM | Primary | None | 18/1 | 109/3 | 10.02 |

| 11 | 34 M, MM | Primary/yes (4) | None | 43/1 | 173/2 | 19.92 |

MM=multiple myeloma, DLBCL= diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

DM=diabetes mellitus, DLCO=diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide

The remaining 9 subjects, including all 5 treated with lenalidomide, collected > 5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg on the first day of collection. Two subjects (#1 and 5) completed a second day of collection with a 6th dose of G-CSF alone. Ten subjects underwent autologous transplantation with a mean and median CD34+ dose of 6.6 and 6.0 × 106/kg (range 3.8–10.8 × 106/kg). All patients transplanted engrafted within normal time frames. The mean and median days to neutrophil engraftment were 11 and 10 days, respectively (range 9–14 days). The mean and median days to platelet engraftment were 19 and 18 days, respectively (range 15–30). There were no adverse events ≥ CTCAE Grade 3. The most common Grade 1–2 adverse events were bone pain and myalgias.

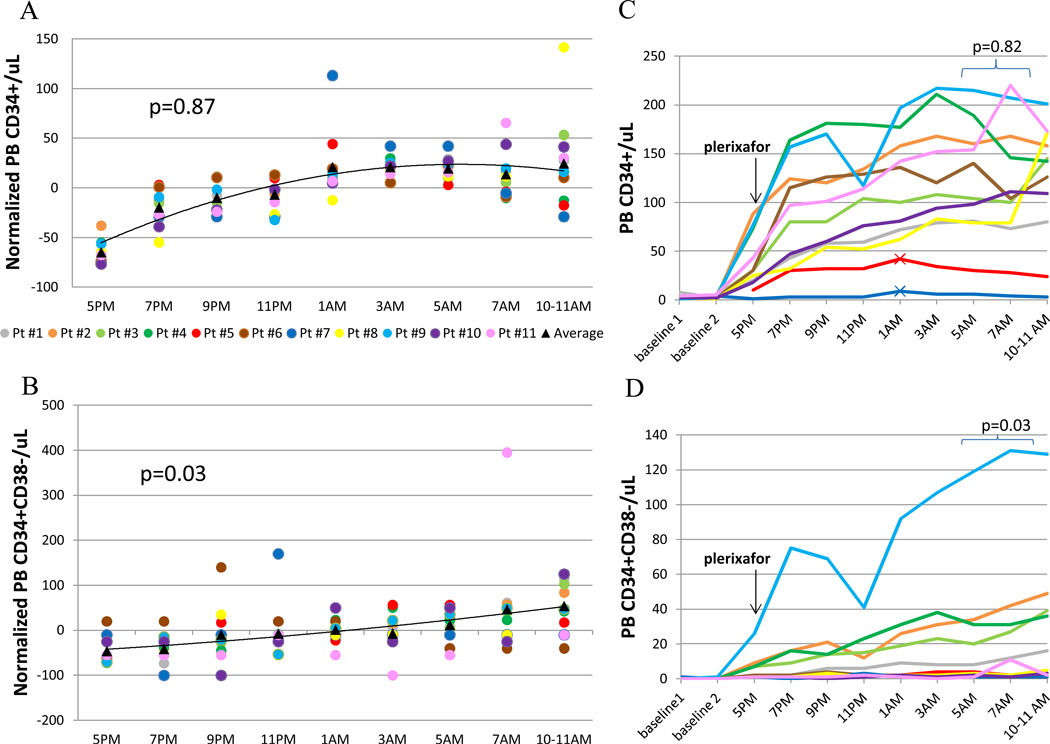

Due to the wide variation in the absolute number of HPCs mobilized in response to G-CSF and plerixafor among individual donors, each donor’s PB [CD34+] and [CD34+CD38−] was normalized as a percentage of that donor’s mean of day 4 through day 5 values (12) in order to more easily identify trends. For PB [CD34+], the peak of the trend was at 12hr post-plerixafor; for PB [CD34+CD38−], the peak of the trend was at 17–18hr post-plerixafor (Figure 2A, B). By mixed model analysis of repeated measures, the 10–18 hr trend for PB [CD34+] was not significant, whereas the 10–18hr PB [CD34+CD38−} trend was (p=0.03). Paired t-test analyses of absolute concentrations (Figure 2C, D) also showed no difference in PB [CD34+] when comparing the 10–12hr to the 14–18hr post-plerixafor values, but a significant increase in PB [CD34+CD38−] from the 10–12hr to 14–18hr post-plerixafor values (p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Study outcome data. (A) Normalized PB [CD34+]. (B) Normalized PB [CD34+CD38−]. (C) Absolute PB [CD34+]. (D) Absolute PB [CD34+CD38−]. N=11. Each donor is identified with the same color in all graphs. For (A) and (B), each dot represents an individual donor’s percent change from their PB mean. In (C), the 2 poorest mobilizers have cross-hatches added to their lines, indicating their early [CD34+] peak. P-values were obtained for 10–18 hr post-plerixafor data using mixed model analysis of repeated measures (A, B) or paired t-testing (C, D).

With G-CSF alone, there is no significant increase in PB [CD34+] from the evening of day 4 to the morning of day 5 of G-CSF (13). Therefore post- to pre-plerixafor [CD34+] ratios can be used to compare efficacy of plerixafor kinetics. The average and median ratio of the 17–18hr post- to (5pm) pre-plerixafor [CD34+] was 3.8 and 4.0, respectively (range 1.8–6.8). For comparison, the average and median ratio of the peak post- to pre-plerixafor [CD34+] was 4.8 and 4.7, respectively (range 1.9–9). This difference was not significant (p= 0.09). The three subjects with the lowest mobilization (#1, 5, and 7) all had diabetes, but the peak/pre [CD34+] ratio was not adversely affected. Two of these three (#5 and 7) reached their peak [CD34+] mobilization at 8hr post-plerixafor, whereas all other donors reached their peak [CD34+] at least 10hr post-plerixafor.

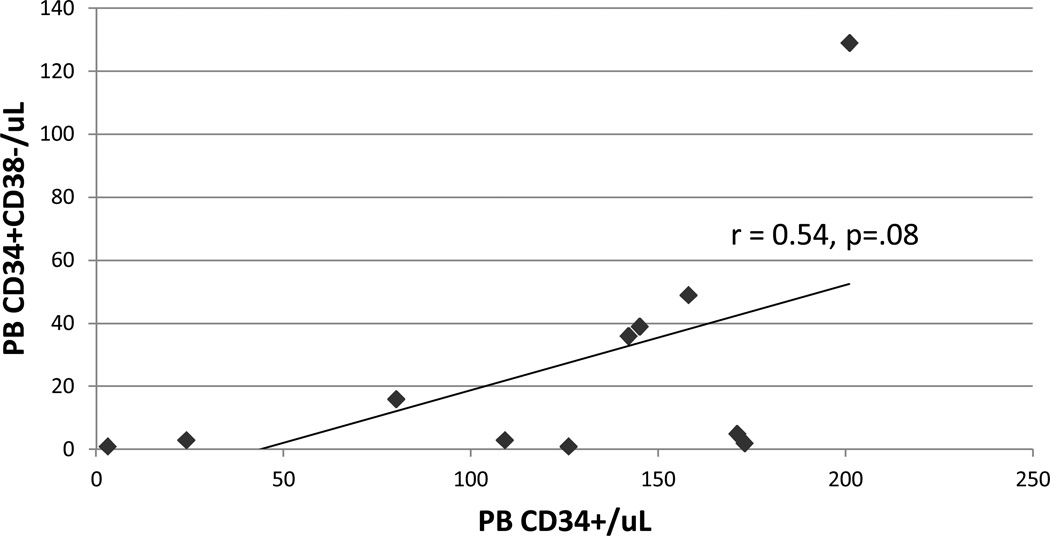

The correlation coefficient between the day 5 product CD34+ dose/kg and the day 5 pre-apheresis (10–11 am) PB [CD34+] was 0.95. The correlation coefficient of 0.54 between the PB [CD34+] and [CD34+CD38−] was weak (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation between Day 5 10–11AM PB [CD34+] and [CD34+CD38−]. r-value was obtained using Pearson correlation.

Discussion

Plerixafor is currently FDA-approved for administration approximately 11hr prior to initiation of apheresis, because in the pivotal trials leading to plerixafor approval, it was administered at 10 pm. Administration by health care personnel at 10 pm, however, is impractical.

This study is unique in examining multiple time points out to 17–18 hr post-plerixafor in MM and NHL patients, and supports prior studies that [CD34+] can be maintained up to 17–18hr post-plerixafor (7, 8). An equal number of patients reached their peak PB [CD34+] between 14–18 hr as between 10–12 hr post-plerixafor (Subject #2 reached equal peaks during both time periods). The 17–18hr post- to pre-plerixafor ratio was lower than the peak post- to pre-plerixafor ratio, but this decrease did not reach clinical significance. In addition, the median of the 17–18 hr post-pre [CD34+] ratio, 4.0, was the same as the 15hr post-pre [CD34+] ratio found in an earlier retrospective study (6), and is comparable to the median 4.6 post-pre [CD34+] ratio seen at 17 hours in the earlier MM study (7).

This study was also unique in examining PB [CD34+CD38−] concentration, which significantly peaked between 14–18 hr in 7 out of 11 patients. In the 4 patients whose PB [CD34+CD38−] peak was earlier, the increase over 14–18 hr post-plerixafor values was either minimal (Subject #4, 38/uL vs 36/uL) or the peak mobilization was low at ≤ 4/uL. Given the weak correlation between PB [CD34+] and [CD34+CD38−], the utility of using PB [CD34+CD38−] compared to [CD34+] alone to determine the optimal time for collection may be worth exploring given the correlation between CD34+CD38− graft content and long-term neutrophil and platelet reconstitution in the autologous transplant setting (14, 15).

This study also supports the consideration that patient ailments or medications influence stem cell mobilization. The three donors with post-plerixafor PB [CD34+] < 100/uL all had diabetes (type II), which has been established to impair G-CSF induced stem cell mobilization (16, 17). Murine data suggest that plerixafor overcomes this sympathetic nervous system-related defect in mobilization, and our data supports this hypothesis, since the peak [CD34+] post- to pre-plerixafor ratio was > 4 in all 3 patients. Interestingly, the donor (Subject #9) with the second highest mobilization also had diabetes but had a relatively low peak/pre [CD34+] ratio of 2.9. Therefore she had excellent mobilization with G-CSF alone, and we hypothesize that her mobilization impairment from diabetes may have been overcome by her concurrent use (for asthma) of the β2-adrenergic agonist albuterol, which has previously reported to be associated with high mobilization (13, 18).

As previously reported (6, 19), pre-plerixafor PB [CD34+] correlated well with (peak) post-plerixafor [CD34+] (r=0.78) as well as CD34+ product count. (r=0.76). Also as previously reported (6), prior treatment with lenalidomide did not exclude a successful collection, with all 4 such patients collecting > 5 × 106 CD34 cells/kg.

An important qualification of this study is that 9 of the 11 patients had a pre-plerixafor PB [CD34+] > 10/uL, and were thus adequate mobilizers. There have been two prior studies examining plerixafor pharmacodynamics in poorly mobilizing NHL and MM patients. Cooper et. al. (6) found that 25 of 30 patients with pre-plerixafor PB [CD34+] <10/ul still collected at least 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg in 1–2 collections. The second study (11) specifically examined patients who had previously failed 2 consecutive mobilizations, and found that the median peak PB [CD34+] was 8 hr post-plerixafor (range 6–9 hr). This finding is consistent with our study, where the 2 patients with relatively poor [CD34+] mobilization reached their peak PB [CD34+] at 8 hr post-plerixafor.

In summary, in this study primarily of patients who were adequate mobilizers, initiating leukapheresis at 17–18 hr versus 10–12 hr post-plerixafor does not significantly compromise CD34+ product yield. This includes patients with prior lenalidomide treatment but may not include patients with risk factors for poor mobilization such as diabetes or salvage chemotherapy. Poor mobilizers still responded to plerixafor, but peaked earlier ~8 hr post-plerixafor. No PB [CD34+] values were evaluated during apheresis, and the PB [CD34+] trend line at 17–18 hr was decreasing although the 17–18 hr PB [CD34+CD38] trend line was increasing. Given these considerations, the ideal time to initiate apheresis for a standard 3 TBV leukapheresis typically lasting 3–4 hours may be ~15 hr post-plerixafor for good mobilizers, and ~8 hr in poor mobilizers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study subjects; Erlinda Sacris, the study research nurse; Janice Gabrilove, Emilia Bagiella, and Vijay Nandi for statistical analysis advice and/or assistance; and Alla Oren for flow cytometry assistance.

Support: This study was funded by Grant Number #UL1RR029887 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Genzyme (Cambridge, MA). Genzyme specified subject enrollment criteria but had no other role in study design or collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. NCRR/NIH had no role in study design or collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest for any authors.

References

- 1.DiPersio JF, Micallef IN, Stiff PJ, Bolwell BJ, Maziarz RT, Jacobsen E, et al. Phase III prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of plerixafor plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor compared with placebo plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for autologous stem-cell mobilization and transplantation for patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4767–4773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7209. Epub 2009/09/02. doi: JCO.2008.20.7209 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7209. PubMed PMID: 19720922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiPersio JF, Stadtmauer EA, Nademanee A, Micallef IN, Stiff PJ, Kaufman JL, et al. Plerixafor and G-CSF versus placebo and G-CSF to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells for autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;113(23):5720–5726. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174946. Epub 2009/04/14. doi: blood-2008-08-174946 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174946. PubMed PMID: 19363221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lack NA, Green B, Dale DC, Calandra GB, Lee H, MacFarland RT, et al. A pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model for the mobilization of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells by AMD3100. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2005;77(5):427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.12.268. PubMed PMID: 15900288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart DA, Smith C, MacFarland R, Calandra G. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of plerixafor in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.018. PubMed PMID: 19135941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiff P, Micallef I, McCarthy P, Magalhaes-Silverman M, Weisdorf D, Territo M, et al. Treatment with plerixafor in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma patients to increase the number of peripheral blood stem cells when given a mobilizing regimen of G-CSF: implications for the heavily pretreated patient. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(2):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.11.028. PubMed PMID: 19167685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper DL, Pratt K, Baker J, Medoff E, Conkling-Walsh A, Foss F, et al. Late afternoon dosing of plerixafor for stem cell mobilization: a practical solution. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 11(3):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2011.03.014. Epub 2011/06/11. doi: S2152-2650(11)00015-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.clml.2011.03.014. PubMed PMID: 21658654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey RD, Kaufman JL, Johnson HR, Nooka A, Vaughn L, Flowers CR, et al. Temporal changes in plerixafor administration and hematopoietic stem cell mobilization efficacy: results of a prospective clinical trial in multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(9):1393–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.003. Epub 2013/06/15. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.06.003. PubMed PMID: 23764455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liles WC, Rodger E, Broxmeyer HE, Dehner C, Badel K, Calandra G, et al. Augmented mobilization and collection of CD34+ hematopoietic cells from normal human volunteers stimulated with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor by single-dose administration of AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. Transfusion. 2005;45(3):295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04222.x. Epub 2005/03/09. doi: TRF04222 [pii] 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.04222.x. PubMed PMID: 15752146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flomenberg N, Devine SM, Dipersio JF, Liesveld JL, McCarty JM, Rowley SD, et al. The use of AMD3100 plus G-CSF for autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization is superior to G-CSF alone. Blood. 2005;106(5):1867–1874. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0468. PubMed PMID: 15890685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazitt Y, Freytes CO, Akay C, Badel K, Calandra G. Improved mobilization of peripheral blood CD34+ cells and dendritic cells by AMD3100 plus granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. Stem cells and development. 2007;16(4):657–666. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0087. PubMed PMID: 17784839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lefrere F, Mauge L, Rea D, Ribeil JA, Dal Cortivo L, Brignier AC, et al. A specific time course for mobilization of peripheral blood CD34+ cells after plerixafor injection in very poor mobilizer patients: impact on the timing of the apheresis procedure. Transfusion. 2013;53(3):564–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03744.x. Epub 2012/06/26. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03744.x. PubMed PMID: 22725259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrahamsen JF, Smaaland R, Sothern RB, Laerum OD. Variation in cell yield and proliferative activity of positive selected human CD34+ bone marrow cells along the circadian time scale. Eur J Haematol. 1998;60(1):7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1998.tb00990.x. Epub 1998/02/06. PubMed PMID: 9451422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi PA, Isola LM, Gabrilove JL, Moshier EL, Godbold JH, Miller LK, et al. Prospective cohort study of the circadian rhythm pattern in allogeneic sibling donors undergoing standard granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilization. Stem cell research & therapy. 2013;4(2):30. doi: 10.1186/scrt180. Epub 2013/03/22. doi: 10.1186/scrt180. PubMed PMID: 23514984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Specchia G, Pastore D, Mestice A, Liso A, Carluccio P, Leo M, et al. Early and long-term engraftment after autologous peripheral stem cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Acta Haematol. 2006;116(4):229–237. doi: 10.1159/000095872. Epub 2006/11/23. doi: 95872 [pii] 10.1159/000095872. PubMed PMID: 17119322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henon P, Sovalat H, Becker M, Arkam Y, Ojeda-Uribe M, Raidot JP, et al. Primordial role of CD34+ 38− cells in early and late trilineage haemopoietic engraftment after autologous blood cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1998;103(2):568–581. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01066.x. Epub 1998/11/25. PubMed PMID: 9827938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferraro F, Lymperi S, Mendez-Ferrer S, Saez B, Spencer JA, Yeap BY, et al. Diabetes impairs hematopoietic stem cell mobilization by altering niche function. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(104) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002191. 104ra1. Epub 2011/10/15. doi: 3/104/104ra101 [pii] 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002191. PubMed PMID: 21998408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiPersio JF. Diabetic stem-cell "mobilopathy". N Engl J Med. 2011;365(26):2536–2538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1112347. Epub 2011/12/30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1112347. PubMed PMID: 22204729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendez-Ferrer S, Battista M, Frenette PS. Cooperation of beta(2)- and beta(3)-adrenergic receptors in hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:139–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05390.x. Epub 2010/04/16. doi: NYAS5390 [pii] 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05390.x. PubMed PMID: 20392229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cashen A, Lopez S, Gao F, Calandra G, MacFarland R, Badel K, et al. A phase II study of plerixafor (AMD3100) plus G-CSF for autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(11):1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.08.011. Epub 2008/10/23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.08.011. PubMed PMID: 18940680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]