Abstract

Objectives

To examine racial and ethnic differences in the relation between body mass index (BMI) and self-rated mental health (SRMH) among community-dwelling older adults.

Design

Cross-sectional analyses of nationally representative data from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys

Setting

In-person household interviews

Participants

Older adults aged 60 and older (N = 2,017), including non-Hispanic Whites (n = 547), Blacks (n = 814), Hispanics (n = 401), and Asians (n = 255)

Measurements

SRMH was measured with a single item, “How would you rate your own mental health?” BMI categories were underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), healthy weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (≥30.0 kg/m2).

Results

Results from a two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) showed that after controlling for covariates, there was a significant main effect of race/ethnicity on SRMH, but the main effect of BMI was not significant. A significant interaction between BMI and race/ethnicity on SRMH was also found. The linear contrasts showed that Whites had a significant trend showing that SRMH decreased with increases in BMI, whereas Blacks had a significant trend showing that SRMH increased with increases in BMI. The linear trends for Hispanics and Asians were not significant.

Conclusions

There were significant racial/ethnic differences in the relation between BMI and SRMH. Understanding the role of race/ethnicity as a moderator of the relation between BMI and mental health may help improve treatment for older adults with unhealthy weights. Clinical implications are also discussed.

Keywords: Race/Ethnicity, Self-Rated Mental Health, Body Mass Index, Older Adults

Objectives

The present study focuses on the relation between weight and mental health among older adults, a group showing dramatic increases in obesity rates over the past decade. The existing literature suggests a significant association between weight and mental health (1-9). The primary focus of previous work has been on the connection between obesity and mental health, with only a few studies considering the effects of being underweight (10). The directionality of the significant association between obesity and mental health, however, remains unclear. Whereas the majority of studies used cross-sectional data, some studies used longitudinal data (11-13) and/or provided bi-directional relations (11-12) showing that while obesity predicts depression, depression also predicts obesity. One set of studies reported a positive association between obesity and mental health issues (1, 4-7, 9). For example, Scott and colleagues (9) found that severe obesity was significantly associated with psychiatric disorders in the general population. One theoretical framework proposed for this association builds on the idea that the stigma and discrimination often encountered by those with excess weight may have mental health consequences (14-18). That is, obese people, as a stigmatized group, may experience discrimination and status loss, which in turn may have harmful consequences for psychological, economic, and physical well-being (16, 19). Thus, under the assumption that societal anti-obese attitudes will be translated into discriminatory behaviors, one might expect that obesity will be associated with poor mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and psychological distress.

In contrast to the above theory, some studies reported that obesity is associated with better mental health (2-3, 8). For example, Crisp and McGuiness (2) found in their epidemiological study that obesity was significantly associated with lower levels of anxiety among adults aged 40 to 65. Palinkas and colleagues (8) found that obese adults were also at lower risk for depressive symptoms than non-obese adults. These findings support what has been labeled the “Jolly Fat” hypothesis. This suggests that being obese may be protective against the experience of mental health problems or, conversely, may be associated with a denial of actual or reported experience of mental health problems (2-3). Under this conceptualization, one might hypothesize that being obese or overweight will be associated with better reported mental health outcomes such as lower levels of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress.

The literature yields conflicting findings on the role of race/ethnicity in this dynamic. One study found no racial/ethnic differences in the association between obesity and depression among adolescents (20). Heo and colleagues (14), however, found that both overweight and obese Hispanic men in the 2001 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) were significantly more likely than healthy weight respondents to experience depressed mood. Among Black men, on the other hand, the same researchers found that obese respondents were less likely to experience depressed mood than were healthy weight respondents. Thus far, there is an absence of studies conducted with Asian samples.

The present study was prompted by the need for a better understanding of racial/ethnic differences in the association between weight and mental health status among older adults. We expected that racial/ethnic patterns of the association would not be consistent across racial/ethnic groups. Based on prior research showing that Blacks were typically more satisfied with their body and more accepting of larger body sizes (21-22), we expected that older Blacks would show a weaker association of obesity with SRMH than would non-Hispanic Whites.

Methods

Sample

The present study used nationally representative samples of diverse racial/ethnic older Americans drawn from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES, 2001-2003). The CPES is the first nationally representative data set with sufficient power to investigate cultural influences on mental disorders in the general population. Detailed information on the CPES is available elsewhere (23). The use of publicly available CPES data received approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama.

Since racially/ethnically diverse older populations are of particular interest in this study, adults aged 60 or older (N = 2,017) with no missing data on major study variables were selected for inclusion in the analyses. The final sample included 547 non-Hispanic Whites (hereafter simply referred to as Whites), 814 Blacks, 401 Hispanics, and 255 Asians.

Measures

Self-Rated Mental Health (SRMH)

A single question, “How would you rate your overall mental health?” was used to assess SRMH. Respondents were asked to select one of five categories—excellent (coded as 1), very good (coded as 2), good (coded as 3), fair (coded as 4), or poor (coded as 5). Previous studies have established the validity of the single item SRMH measure in racially/ethnically diverse populations (24-28), showing strong associations with physical and mental health status (24-25, 28) and mental health service use (26-27) with some variations by race/ethnicity. The SRMH question, rather than psychiatric disorders, was used as our outcome measure because it assesses respondents' overall subjective mental health status, and because the distribution of diagnoses tends to be skewed among older adults. The total number of diagnoses for psychiatric disorders was however used as a covariate in all analyses.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

BMI was calculated by dividing each person's self-reported weight in kilograms by the square of self-reported height in meters (kg/m2). Although BMI does not directly measure body fat, research suggests that BMI is a reliable indicator of body fat, correlating highly with direct measures of body fat (29-30). The validity of self-reported and measured BMI has been established in previous research (31-32). The CPES reports BMI as a categorical variable with four levels: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), healthy weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2).

Covariates

An extensive array of demographic and background characteristics were employed as covariates in our analyses: age (years), sex (male/female), marital status (married/not married), educational attainment (less than high school/high school graduate/some college/4 year college degree or higher), household income (dollars), number of chronic diseases (range 0-8), number of Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)-diagnosed 12-month psychiatric disorders (range 0-11), and self-rated health (a single item question on “how would you rate your overall physical health?”; range 1-5, where higher scores indicated poorer health).

Analysis

Chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests (for continuous variables) were conducted to evaluate racial/ethnic group differences. A two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was also conducted to assess the interaction between BMI and race/ethnicity on SRMH. The two-way ANCOVA was followed by a set of linear contrasts to determine whether there was a significant linear trend in SRMH across the different levels of BMI. The linear contrasts for BMI were defined as (-3 × underweight - 1 × healthy weight + 1 × overweight + 3 × obese). We also tested for the presence of a curvilinear relation using quadratic contrasts (defined as 1 × underweight - 1 × healthy weight - 1 × overweight + 1 × obese), although this was never significant. The two-way ANCOVA and contrast analyses all controlled for the covariates discussed above. All analyses were conducted using IBM-SPSS version 20.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

As summarized in Table 1, all study variables and covariates differed significantly across the four racial/ethnic groups. Whites were the oldest and Asians were the youngest. More than half of each racial/ethnic group were female, with Whites and Blacks including more women. Dramatic racial/ethnic differences were found in marital status: Asians were most likely to be married and Blacks were least likely. Asians had the highest levels of educational attainment and Hispanics, the lowest. The total number of chronic diseases also varied by race/ethnicity, such that Blacks had the most chronic diseases and Asians had the fewest. Hispanics had the greatest number of psychiatric disorders, whereas Asians had the fewest. With regard to self-rated physical health, Hispanics rated their general health the poorest, whereas Whites rated their health the best.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Sample and Study Variables (N = 2,017).

| M±SD (Median/IQR)† or % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

F (ndf, ddf) or χ2(df) | ||||

| Variable | Whites (n = 547) | Blacks (n = 814) | Hispanics (n = 401) | Asians (n = 255) | |

| Body Mass Index (BMI)a,c,e,f | 149.54 (9)*** | ||||

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 2.7% | 2.5% | 1.5% | 5.5% | |

| Healthy Weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9) | 38.4% | 26.4% | 27.7% | 60.0% | |

| Overweight (BMI = 25.0–29.9) | 34.6% | 40.2% | 48.6% | 27.5% | |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0) | 24.3% | 31.0% | 22.2% | 7.1% | |

| Self-Rated Mental Health (range 1-5) a,b,c | 2.13±1.00 | 2.43±1.03 | 2.33±1.31 | 2.51±1. 17 | 11.16 (3, 2013)*** |

| Covariates | |||||

| Age (range 60-97 years) a,b,c | 71.55±7.82 | 69.75±7.39 | 69.06±7.30 | 68.64±6.92 | 13.22 (3, 2013)*** |

| Female c,e | 62.7% | 62.0% | 57.6% | 50.2% | 14.21 (3)** |

| Married a,c,d,e,f | 42.8% | 31.1% | 49.6% | 73.3% | 149.80 (3)*** |

| Educational attainment a,b,d,e,f | 160.39 (9)*** | ||||

| < High school | 25.4% | 44.8% | 58.1% | 30.6% | |

| High school | 35.3% | 28.1% | 18.7% | 18.8% | |

| Some college | 19.4% | 11.8% | 12.0% | 19.6% | |

| ≥ 4-year college degree | 19.9% | 15.2% | 11.2% | 31.0% | |

| Annual household income ($) a,b,c,e,f | 38523.36± 37771.61 | 26920.35± 29335.90 | 29793.97± 37955.99 | 51360.63± 54927.62 | 31.50 (3, 1897)*** |

| # Chronic diseases (range 0-8) c,d,e | 2.03±1.39 (2.00/2) | 2.11±1.45 (2.00/2) | 1.85±1.38 (2.00/2) | 1.69±1.17 (2.00/2) | 7.25 (3, 1897)*** |

| # Mental disorders (12mo.) (range 0-5) a,d,e,f | 0.18±0.60 (0.00/0) | 0.10±0.39 (0.00/0) | 0.22±0.66 (0.00/0) | 0.09±0.38 (0.00/0) | 7.61 (3, 1797)*** |

| Self-rated health (range 1-5) a,b,c | 2.78±1.19 | 3.01±1.17 | 3.12±1.19 | 3.04±1.10 | 7.89 (3, 2011)*** |

Notes. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; ndf = numerator degrees of freedom; ddf = denominator degrees of freedom; df = degrees of freedom; IQR = interquartile range; ANOVA or chi-square tests were used.

Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were provided for # chronic diseases and # mental disorders variables.

Superscript letters (a, b, c, d, e, f) indicate a significant group difference based on Bonferroni post-hoc analysis.

= Whites–Blacks;

=Whites–Hispanics;

= Whites–Asians;

= Blacks–Hispanics;

= Blacks–Asians;

= Hispanics–Asians

p < .01,

p < .001

With regard to key study variables, both BMI and SRMH differed by race/ethnicity. The obesity rate was highest among Blacks and lowest among Asians. While more than half of Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics were either overweight or obese, only about one third of Asians fell into those categories. The healthy weight category was most frequent among Asians, with more than half of the Asian group falling into this category. Regarding SRMH, Whites rated their mental health the best and Asians rated theirs the poorest amongst the four racial/ethnic groups.

Effect of BMI and Race/Ethnicity on SRMH

Table 2 provides the results of a two-way ANCOVA examining the main effect of BMI, the main effect of race/ethnicity, and the BMI × race/ethnicity interaction effect on SRMH. The assumptions of normality (based on the Shapiro-Wilk test) and equal variances (based on Levene's test) were both met. After controlling for covariates (age, sex, marital status, household income, educational attainment, number of chronic diseases, number of 12-month psychiatric disorders, and self-rated health), there was a significant main effect of race/ethnicity [F (3, 1654) = 8.82, p < .001], such that Whites and Hispanics showed better SRMH than Blacks and Asians. The main effect of BMI was not significant [F (3, 1654) = 1.12, p = .34], but the interaction between BMI and race/ethnicity was significant [F (9, 1654) = 1.91, p < .05]. Additional analyses were conducted to test the possibility of three-way interactions of BMI × race/ethnicity × different covariates. However, no three-way interaction was significant.

Table 2. The Effect of BMI, Race/Ethnicity, and BMI × Race/Ethnicity on Self-Rated Mental Health (N = 2,017).

| Variable | df | SS | Partial η2 | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | |||||

| Age | 1 | .58 | .000 | .68 | .41 |

| Sex | 1 | .58 | .000 | .68 | .41 |

| Marital status | 1 | 2.52 | .002 | 2.52 | .09 |

| Educational attainment | 1 | 13.14 | .009 | 15.34 | <.001 |

| Income | 1 | 7.38 | .005 | 8.61 | .003 |

| Chronic diseases | 1 | 1.09 | .001 | 1.27 | .26 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 | 23.65 | .016 | 27.61 | <.001 |

| Self-rated health | 1 | 275.64 | .163 | 321.72 | <.001 |

| Main Effect | |||||

| BMI | 3 | 2.89 | .002 | 1.12 | .34 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 3 | 22.66 | .016 | 8.82 | <.001 |

| Interaction Effect | |||||

| BMI × Race/Ethnicity | 9 | 14.74 | .010 | 1.91 | .05 |

| Error | 1654 | 1417.12 | |||

| Total | 1678 | 11548.00 |

Notes. A two-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed; df = degree of freedom; SS = sum of squares; Partial η2 = partial eta-squared; DV: self-rated mental health

In order to see how covariates affect the association between BMI, race/ethnicity, and SRMH, additional analyses were conducted without covariates. Results from a two-way ANOVA showed the same pattern of results. Without covariates, the main effect of race/ethnicity was significant [F (3, 2001) = 12.82, p = .02], but there was no significant main effect of BMI [F (3, 2001) = 1.77, p = .15]. The interaction between BMI and race/ethnicity remained significant without covariates [F (9, 2001) = 2.26, p = .02].

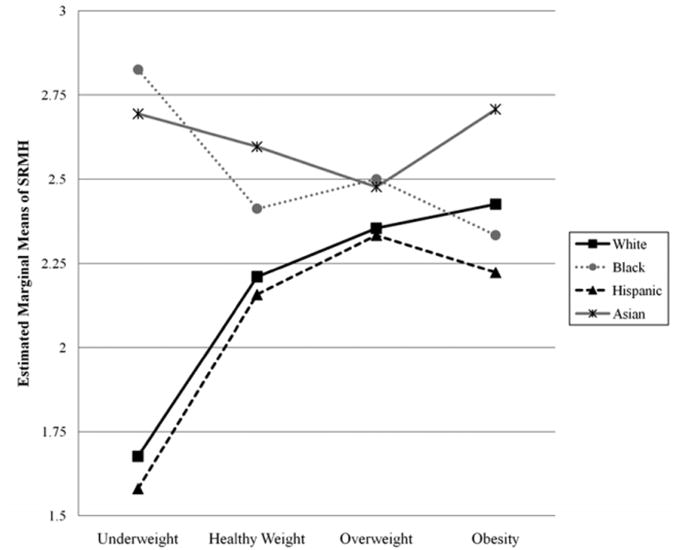

Figure 1 illustrates the estimated marginal means for SRMH by BMI and race/ethnicity. The most obvious feature of this graph is that in general SRMH gets worse with increases in BMI for Whites and Hispanics, whereas SRMH gets better with increases in BMI for Blacks and Asians. There were significant racial/ethnic differences in SRMH scores in the underweight [F (3, 48) = 4.17, p = .01] and healthy weight [F (3, 566) = 5.14, p < .001] categories.

Figure 1. Estimated Marginal Means of SRMH by BMI × Race/Ethnicity.

Notes. Estimated marginal means of SRMH were calculated after adjusting for covariates (age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, income, number of chronic diseases, number of psychiatric disorders, and self-rated health).

The trends depicted in Figure 1 appear to have a slight curve, so we tested for the presence of a curvilinear relation using quadratic contrasts (using weights of 1 -1 -1 1 for the four levels of BMI). This test of the quadratic contrast was not significant in the overall sample (F[1, 1655] = .60, p = .44), nor was it significant when testing each of the racial/ethnic groups separately (all ps > .10). We therefore decided to focus on the linear trends. We tested linear contrasts for BMI in each racial/ethnic group to identify whether there is a significant linear trend in SRMH across the different levels of BMI. We then used additional contrasts to test whether the strength of the linear trend differed between pairs of racial/ethnic groups, which are reported in Table 3 as homogenous subsets. As presented in Table 3, Whites had a significant trend showing poorer SRMH with increases in BMI, whereas Blacks had a significant trend showing better SRMH with increases in BMI. The linear trends for Hispanics and Asians were not significant, which may suggest the presence of a non-linear relation between BMI and SRMH (although no statistical evidence for such a trend was found in the current study). The linear trend for Blacks was significantly different from that for Whites and Hispanics, but none of the other trends were significantly different from each other.

Table 3. Linear Contrasts for BMI by Race/Ethnicity.

| Race/Ethnicity | Linear Contrast (standard error) | F [1, 1655] | p | Homogenous Subset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 547) | 2.44 (1.04) | 5.52 | .02 | B |

| Black (n = 814) | -1.40 (.68) | 4.30 | .04 | A |

| Hispanic (n = 401) | 2.07 (1.19) | 3.03 | .08 | B |

| Asian (n = 255) | -.14 (1.01) | .02 | .89 | AB |

Notes. The linear contrast is defined as (-3 × underweight - 1 × healthy weight + 1 × overweight + 3 × obese). Positive values indicate that higher BMI is associated with poor mental health. All covariates (age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, income, number of chronic diseases, number of psychiatric disorders, and self-rated health) were adjusted. The homogenous subsets represent comparisons between the linear contrasts within the different racial/ethnic groups; the linear trends for groups that do not share a subset are significantly different from each other (p < .05).

Discussion

The present study investigated the role of race/ethnicity in the association between weight (i.e., BMI) and self-ratings of general mental health status among U.S. older adults from the nationally representative data. Based on existing research, we expected that the BMI-self-rated mental health association would vary by race/ethnicity and that older Blacks would show a weaker association of obesity with SRMH than would Whites. To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated racial/ethnic differences in the association between BMI and SRMH in a geriatric population. Strong evidence for racial/ethnic differences in the association between BMI and SRMH was found; Whites and Hispanics in general showed poorer SRMH as BMI increased, whereas Blacks and Asians had better SRMH as BMI increased. The two unique linear patterns, however, differed significantly only between Whites and Blacks. The patterns for Hispanics and Asians might suggest the presence of a non-linear relation between BMI and SRMH, although we did not find statistical evidence of this in our analyses. Of particular interest was that Blacks and Asians had poorer SRMH compared with Whites and Hispanics regardless of weight.

It is striking that even after controlling for all covariates (including psychiatric diagnoses), the relation of BMI with SRMH differed significantly by race/ethnicity, revealing two distinctive racial/ethnic patterns. The previously reported positive significant relation between obesity and poor mental health (1, 4-7, 9) did appear in the present study, but only among older Whites. This finding may result from a social climate in which obesity is viewed as a deviation from the desired norm, such that those having excess weight are often stigmatized and discriminated (17-18). The opposite direction of the BMI-SRMH relation—referred to as the “Jolly Fat” hypothesis in previous research (2-3, 8)—was found among Blacks and Asians.

The opposing relationships are of particular significance to researchers interested in strategies for primary and secondary prevention. One possible reason for these different racial/ethnic patterns is related to differences in body image and body satisfaction that are found across different cultural groups. Previous research has reported evidence that Black adults tend to be more satisfied with their bodies in general (22) and with larger body sizes than are other racial/ethnic groups (23). The unique cultural environment of Blacks—namely, a cultural tolerance for overweight and obesity— may be closely related to our finding that obese or overweight Blacks are not be mentally distressed by their weight status, and that underweight Blacks may be more vulnerable in terms of their mental health and emotional well-being. However, a closer examination is clearly needed to better understand the mechanism underlying this association of body weight and mental health among older Blacks.

Our finding that racial/ethnic differences in SRMH only appeared in underweight and healthy weight categories should be highlighted. In contrast to the linear trend lines, SRMH in the overweight or obesity categories did not significantly differ by race/ethnicity. Specific reasons for this finding are not immediately apparent, but this may be closely related to age-related changes in body weight and composition that are experienced across all racial/ethnic groups. Given that older adults are likely to gain weight as they get older, at least until extreme old age, gaining weight may not be viewed as a particularly negative thing (33-34). In other words, among older persons, those who are overweight or obese may view their weight as being less problematic than do younger counterparts. A comparative study may be helpful to identify similarities and differences in the association between BMI and SRMH among younger and older adults. As was noted in the introduction, despite reported evidence that obesity is related to mental health (1-2, 4-5, 8-9, 14), our understanding of how other weight problems, such as being underweight, are associated with mental health is limited. Given that the existing literature has predominantly focused on the linkage between obesity and mental health, our findings clearly contribute to the field by providing additional information on how mental health is associated with body weight more generally.

It is also worth mentioning that both Blacks and Asians reported poorer mental health than Whites and Hispanics regardless of their BMI category. This is consistent with at least one previous study, which found Blacks and Asians had poorer SRMH scores than non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics (26). This suggests that clinicians working with older Blacks and Asians with weight problems should be aware that these ethnic groups may also have an elevated need for mental health treatment. Future research should focus on elucidating reasons for the reported racial/ethnic differences on self-ratings of mental health.

The present study is not without limitations. The first and perhaps most importantly, the BMI measure is based on self-reported weights and heights. Although BMI has been found to have high correlations with direct measures of body fat in previous research (29-30), the accuracy of BMI data based on self report in the present sample is unknown, which may raise concerns about BMI misclassification in certain racial/ethnic groups. Previous research reports the misclassification of BMI among Asian populations (35-36). Also, our use of a categorical, rather than continuous, BMI measure limits this study. Second, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is not possible to identify the causal directionality of the association between BMI and SRMH. Longitudinal research should be conducted to clearly identify the causal relation between BMI and SRMH. Third, subgroup differences within ethnicities have not been considered in the present study. Given that previous research reported the heterogeneity of Hispanic and Asian Americans (37) and subgroup differences in SRMH scores among Asian Americans (38), these subgroup differences should be taken into account in future research. Fourth, the potential effect of cohort differences was not considered. Future research should investigate whether the same association between BMI and mental health status appears among younger adults. Fifth, geographic location was not considered in analyses because it was not available in the data set; this should be considered in future research. Sixth, although prior research reports differences in the BMI–mental health association by sex (14-16), we could not find any evidence for the three way interaction of BMI, race/ethnicity, and other covariates including sex. Thus, future research might fruitfully focus on sex differences. Lastly, relying on a single-item measure to assess subjective mental health status may limit the present study. Our rationale for the use of an overall measure of perceived mental health arose from the fact that this kind of measure is more readily available to screeners and community providers than the more sophisticated, diagnostic measures of anxiety, depression or other mental health. However, use of a single-item measure restricts variability in response. Thus, future research should use a wider range of SRMH items to achieve greater validity across diverse cultural groups.

Notwithstanding these limitations, there are several strengths that enable the present study to contributes substantially to the existing literature. A key strength is our focus on racial/ethnic differences in the association between BMI and how people perceive their own mental health status. Previous findings that obesity was associated with poorer mental health conditions were not uniformly supported for the present diverse elderly samples. Only older Whites and Hispanics with obesity tended to have poorer mental health status than their underweight or healthy weight counterparts. The finding of unique racial/ethnic patterns clearly advances our knowledge of the relation of BMI with self-ratings of mental health status in the geriatric population. In addition, given that most of the existing work on body image and race/ethnicity has been with younger, often exclusively female samples, the important contribution of this work is that the association between weight and well-being extends to diverse older adults, albeit not always consistently.

In conclusion, understanding the role of race/ethnicity as a moderator of the association between BMI (including those who are underweight, healthy weight, overweight, and obese) and mental health may help improve treatment for older adults with unhealthy weights. Future research should identify reasons for the different association of BMI and SRMH across diverse cultural groups, as well as the mechanism of the relation between weight and mental health. It should be noted that our study examined a community sample that was relatively healthy. While using a generally healthy sample strengthened internal validity of the study, it also is possible that different associations may appear among older, frailer individuals, because nutritional issues may be more important and the “failure to thrive” syndrome may lead to increased medical-psychiatric comorbidity (39-40). Thus, future research should be conducted in different populations to clearly understand how weight status affects self-ratings of mental health status and general emotional well-being. Public health programs or intervention strategies that target unhealthy weight older adults should consider potential comorbid mental health problems among certain racial/ethnic groups. Clinicians working with geriatric patients with weight problems should recognize that race/ethnicity may play a crucial role in the relation of weight and mental health. In particular, obesity's association with positive mental health among older Blacks deserves attention. Clearly, the BMI-SRMH connection should be understood in the cultural environment context.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: The Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) were supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (#U01-MH60220, #U01-MH57716, #U01-MH062209, and #U01-MH62207). This research is supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (P30AG031054, the Deep South Resource Center for Minority Aging Research [RCMAR]) and the University of Alabama Research Grants Committee (RGC) grant (PI: Giyeon Kim).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No Disclosures to Report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baumeister H, Härter M. Mental disorders in patients with obesity in comparison with healthy probands. Int J Obesity. 2007;31:1155–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crisp AH, McGuiness B. Jolly fat: relationship between obesity and psychoneurosis in the general population. BMJ. 1976;1:7–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6000.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crisp AH, Queenan M, Sittampaln Y, Harris G. ‘Jolly fat’ revisited. J Psychosom Res. 1980;24:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(80)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiat Res. 2010;178:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.John U, Meyer C, Rumpf HJ, Hapke U. Relationships of psychiatric disorders with overweight and obesity in an adult general population. Obes Research. 2005;13:101–109. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCrea RL, Berger YG, King MB. Body mass index and common mental disorders: exploring the shape of the association and its moderation by age, gender and education. Int J Obesity. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.65. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of depression and its treatment in the general population. J Psychiat Research. 2007;41:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palinkas LA, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Depressive symptoms in overweight and obese older adults: A test of the ‘jolly fat’ hypothesis. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott KM, McGee MA, Wells E, Browne MAO. Obesity and mental disorders in the adult general population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly S, Daniel M, Dal Grande E, Taylor A. Mental ill-health across the continuum of body mass index. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:765. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2010;67:220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan A, Sun Q, Czernichow S, Kivimaki M, Okereke OI, Lucas M, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and obesity in middle-aged and older women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011 Jun 7; doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.111. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukamal KJ, Kawachi I, Miller M, Rimm EB. Body mass index and risk of suicide among men. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Mar 12;167(5):468–475. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heo M, Pietrobelli A, Fontaine KR, Sirey JA, Faith MS. Depressive mood and obesity in US adults: comparison and moderation by sex, age, and race. Int J Obesity. 2006;30:513–519. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Istvan J, Zavela K, Weidner G. Body weight and psychological distress in NHANES I. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16:999–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onyike CU, Crum RM, Lee HB, Lyketsos CG, Eaton WW. Is obesity associated with major depression? Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. Am J Epidemiology. 2003;58:1136–1147. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr D, Friedman MA. Is obesity stigmatizing? Body weight, perceived discrimination, and psychological well-being in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46:244–259. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:788–805. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franko DL, Striegel-Moore RH, Thompson D, Schreiber GB, Daniels SR. Does adolescent depression predict obesity in black and white young adult women? Psychol Med. 2005;35:1505–1513. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reboussin BA, Rejeski WJ. Body function and body appearance in middle- and older aged adults: The Activity Counseling Trial (ACT) Psychol Health. 2000;15:239–254. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgibbon ML, Blackman LR, Avellone ME. The relationship between body image discrepancy and body mass index across ethnic groups. Obes Res. 2000;8:582–589. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan H, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int J Method Psych. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleishman JA, Zuvekas S. Global self-rated mental health: Associations with other mental health measures and with role functioning. Med Care. 2007;45:602–609. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim G, DeCoster J, Chiriboga DA, Jang Y, Allen RS, Parmelee P. Associations between self-rated mental health and psychiatric disorders among older adults: Do racial/ethnic differences exist? Am J Geriat Psychiat. 2011;19:416–422. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181f61ede. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim G, Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Ma GX, Schonfeld L. Factors associated with mental health service use in Latino and Asian immigrant elders. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:535–542. doi: 10.1080/13607860903311758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuvekas SH, Fleishman JA. Self-rated mental health and racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use. Med Care. 2008;46:915–923. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817919e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang Y, Park NS, Kim G, Kwag KH, Roh S, Chiriboga DA. The association between self-rated mental health and symptoms of depression in Korean American older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16:481–485. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.628981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrow JS, Webster J. Quetelet's index (W/H2) as a measure of fatness. Int J Obesity. 1985;9:147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mei Z, Grummer-Strawn LM, Pietrobelli A, Goulding A, Goran MI, Dietz WH. Validity of body mass index compared with other body-composition screening indexes for the assessment of body fatness in children and adolescents. Am J Clin Nutri. 2002;75:978–985. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAdams MA, Van Dam RM, Hu FB. Comparison of self-reported and measured BMI as correlates of disease markers in U.S. adults. Obesity. 2007;15:188–196. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight i 4808 EPIC–Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andres R. Does the “best” body weight change with age? In: Stunkard AJ, Baum A, editors. Perspectives in behavioral medicine: Eating, sleeping, and sex. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 1989. pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiggemann M. Body image across the adult life span: stability and change. Body Image. 2004;1:29–41. doi: 10.1016/S1740-1445(03)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dudeja V, Misra A, Pandey RM, Devina G, Dumar G, Vikram NK. BMI does not accuratel predict overweight in Asian Indians in northern India. Brit J Nutr. 2001;86:105–112. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goh VHH, Tain CF, Tong TYY, Mok HPP, Wong MT. Are BMI and other anthropometric measures appropriate as indices for obesity? A study in an Asian population. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1892–1898. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400159-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim G, Chiriboga DA, Bryant AN, Huang CH, Crowther M, Ma GX. Self-rated mental health among Asian American adults: Association with psychiatric disorders. Asian Am J Psychol. 2012;3:44–52. doi: 10.1037/a0024318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim G, Chiriboga DA, Jang Y, Lee S, Huang CH, Parmelee P. Health status of older Asian Americans in California. J Am Geriat Soc. 2010;58:2003–2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed N, Mandel R, Fain MJ. Frailty: An emerging geriatric syndrome. Am J Med. 2007;120:748–753. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robertson RG, Montagnini M. Geriatric failure to thrive. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:343–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]