Abstract

Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) has been increasingly recognized as playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) of renal grafts. This review provides a detailed overview of the new understanding of the involvement of TLR-4 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of renal grafts and its clinical significance in renal transplantation. TLR-4 not only responds to exogenous microbial motifs but can also recognize molecules which are released by stressed and necrotic cells, as well as degraded products of endogenous macromolecules. Upregulation of TLR-4 is found in tubular epithelial cells, vascular endothelial cells, and infiltrating leukocytes during renal ischemia-reperfusion injury, which is induced by massive release of endogenous damage-associated molecular pattern molecules such as high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1. Activation of TLR-4 promotes the release of proinflammatory mediators, facilitates leukocyte migration and infiltration, activates the innate and adaptive immune system, and potentiates renal fibrosis. TLR-4 inhibition serves as the target of pharmacological agents, which could attenuate ischemia-reperfusion injury and associated delayed graft function and allograft rejection. There is evidence in the literature showing that targeting TLR-4 could improve long-term transplantation outcomes. Given the pivotal role of TLR-4 in ischemia-reperfusion injury and associated delayed graft function and allograft rejection, inhibition of TLR-4 using pharmacological agents could be beneficial for long-term graft survival.

Keywords: renal transplantation, ischemia-reperfusion injury, Toll-like receptor 4, delayed graft function, renal graft failure

toll-like receptors (tlrs) are transmembrane proteins with a key role in innate immunity (61). They are members of the interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) superfamily and structurally related to Drosophila Toll. In general, TLRs function as pattern recognition receptors in response to infection and detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which in turn lead to the activation of innate immune defenses via intracellular signaling pathways that culminate in the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are produced constitutively in renal cells and play a key role in innate immunity against invading pathogens (26, 61). In addition to recognizing pathogens, TLRs can also mediate “sterile” inflammation in the absence of infection through recognition of endogenously released danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (74).

At least 10 TLRs have been identified in mammals (74). TLR-4 has increasingly been shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) (26), which is an inevitable episode during kidney transplantation. Kidney transplantation is the leading transplant type worldwide and the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease, shown to be associated with increased life expectancy, decreased morbidity, higher quality of life, and greater cost effectiveness compared with dialysis (28). However, the effects of IRI on renal transplantation, such as delayed graft function (DGF), continue to present a significant barrier to improving clinical outcomes for patients (63).

Herein, we review the evidence of the role of TLR-4 in renal IRI and its possible clinical impact on renal transplantation.

Expression of TLR-4 in the Kidney After IRI

One of the most detrimental factors contributing to early graft injury in renal transplantation is ischemia injury during lengthy hypothermic storage and its subsequent reperfusion injury (19, 71). Hypothermic storage of kidneys from cadaveric donors is necessary for the performance of tissue matching to optimize graft-recipient immunocompatibility and also enables the sharing and transporting of organs between transplant centers (31). During ischemia, the cytoskeleton is disrupted and polarity of tubular epithelial cells is lost. ATP exhaustion rapidly drives the conversion of monomeric G-actin to F-actin (5). Basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase pumps dissociate from the actin cytoskeleton and are redistributed (56). Anchorage of epithelial cells to the basement membrane is lost due to redistribution of integrins to the apical surface, induced by oxidative stress (24). A high level of TLR-4 expression was found in kidneys with ischemia-reperfusion, and induction of its upregulation may be caused by infiltrating macrophages as well as intrinsic renal cells (8, 97). A study by Bergler (8) demonstrated that significantly high TLR-4 expression occurs in rat allogeneic renal transplantation, which is strongly correlated with renal function of the graft.

The studies regarding TLR-4 on animal models are limited due to the technically demanding surgical procedure. However, the warm ischemia-reperfusion model provides valuable evidence for the molecular role of TLR-4 in renal graft IRI. Renal tubular epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells are the key cell types for the biological action of TLR-4.

Tubular epithelial cells.

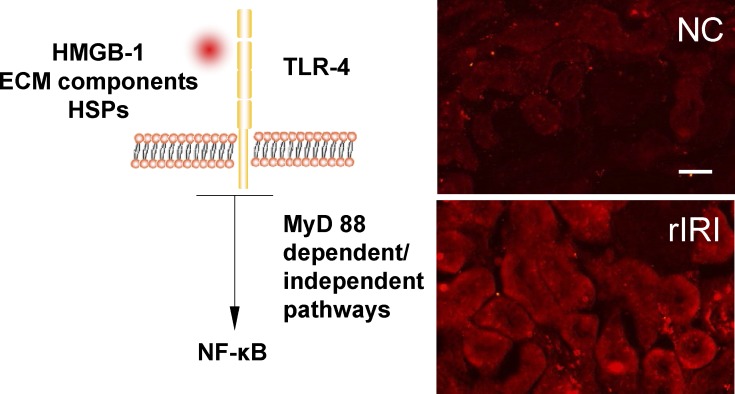

Enhanced TLR-4 expression was observed in tubular epithelial cells in ischemic rat renal grafts 24 h after transplant surgery (97) (Fig. 1). TLR-4 is constitutively expressed by proximal tubular cells, but 24 h after reperfusion it is upregulated in the cortex and outer medulla while TLR-4 can be detected in the medullary thick ascending limb and distal tubules 3–5 days following reperfusion (11). Pulskens et al. (66) used bone marrow transplantation to create chimeric mice, and they found that wild-type mice reconstituted with TLR-4-deficient bone marrow had a similar degree of dysfunction compared with mice reconstituted with wild-type bone marrow. This suggested that TLR-4 expression on parenchymal cells and on leukocytes may equally contribute to injury. However, this is not supported by the work reported by Wu et al.(88), in which TLR-4 mRNA levels are upregulated in tubular epithelial cells subjected to ischemia compared with nonischemic controls. They performed a more rigorous bone marrow chimera experiment but concluded that functional TLR-4 on kidney parenchymal cells made the more significant contribution to renal IRI compared with that on leukocytes. The discrepancies in the results of these two studies require further in-depth investigation with more vigorous molecular approaches to elucidate the potential role of TLR-4 on renal parenchymal and infiltrating leukocytes.

Fig. 1.

Ischemia-reperfusion induced Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) expression on renal cortex in transplanted grafts. Left: schematic diagram of TLR-4 pathway. Right: a Lewis rat kidney was stored in 4°C Soltran preserving solution for 24 h (cold ischemia 24 h) and then transplanted into a Lewis rat recipient; the graft was harvested 24 h after transplantation (warm reperfusion 24 h). The normal kidney serves as a naive control (NC). TLR-4 was expressed on the tubular surface (red fluorescence; cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI). In NC kidney, TLR-4 expression was detectable through a immunofluorescence technique but weak. In the transplanted renal graft after renal ischemia-reperfusion injury (rIRI), the expression of TLR-4 was significantly upregulated. Scale bar = 50 μm. HMGB-1, high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1; HSPs, heat shock proteins ECM, extracellular matrix.

Vascular endothelial cells.

It has been shown that the high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 (HMGB-1), a ligand of TLR-4, was released from injured renal cells and then bound to endothelial TLR-4, and this increased the expression of proinflammatory adhesion molecules (11, 12). The absence of endothelial TLR-4 inhibited upregulation of adhesion molecules and ameliorated inflammation and injury. This indicated that TLR-4 triggered the endothelial activation which is necessary for inflammation during ischemic injury (13). In addition, TLR-4 expression on renal endothelial cells was affected by reactive oxygen species and cellular stress with the insult of hydrogen peroxide (11).

Endogenous Ligands for TLR-4 During Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion

TLR-4 was first recognized for its specific binding to LPS, a major cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria (26). Now, it is accepted that TLR-4 not only responds to exogenous microbial motifs but can also recognize molecules which are released by stressed and necrotic cells, as well as degraded products of endogenous macromolecules (78). The “surveillance model” proposes that, apart from its role in pathogen recognition, TLR-4 can act as a monitoring receptor implicated in the detection of tissue injury (37). Proposed endogenous ligands for TLR-4 that are upregulated during ischemia-reperfusion include HMGB-1, extracellular matrix (ECM) components, and heat-shock proteins (HSPs) (Table 1). However, there was concern that studies of the endogenous ligands could be confounded by contamination with LPS in these animal models. Transgenic techniques have been proven to be a useful tool in resolving this issue; for example, animals or cells deficient in these TLR-4 ligands have shown altered progression of injury and provided the direct evidence supporting their crucial association with the TLR-4 pathway (38, 42, 92).

Table 1.

Recent publications of TLR-4 and its ligands in renal transplantation

| TLR 4 and Ligands | Reference | Year | Model | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR-4 | Andrade-Oliveira et al. (3) | 2012 | Human renal transplantation | Expression levels of TLR-4 and MYD88 were higher in kidneys from deceased donors than from living donors. |

| TLR-4 | Kwon et al. (43) | 2008 | Human renal transplantation | TLR-4 mRNA expression was increased in renal allograft patients with chronic allograft dysfunction. |

| TLR-4 | Lim et al. (50) | 2005 | Rat renal transplantation | Enhanced TLR-4 mRNA and protein expression on renal tubular cells in long-term rat renal grafts. |

| HMGB-1 | Zhao et al. (97) | 2013 | Rat renal transplantation | Suppression of cytoplasmic translocation of HMGB-1 protected renal grafts against ischemia-reperfusion injury. |

| HMGB-1 | Zhao et al. (96) | 2013 | Rat renal transplantation | Suppression of the release of the HMGB-1 protected the renal grafts against ischemia-reperfusion injury. |

| HMGB-1 | Kruger et al. (41) | 2013 | Human renal transplantation | Enhanced expression of HMGB-1 in ischemic renal grafts. |

| HSP70 | Kim et al. (38) | 2005 | Rat renal transplantation | Ischemia-reperfusion injury increased TLR-2 and TLR-4 mRNA and protein expression. Production of endogenous TLR ligand HSP70 on renal tubular cells was enhanced. |

| HSP70 | Zhao et al. (98) | 2013 | Rat renal transplantation | Enhanced expression of HSP70 protected kidney grafts against ischemia-reperfusion injury. |

| Biglycan | Kruger et al. (41) | 2013 | Human renal transplantation | Enhanced expression of biglycan in ischemic renal grafts. |

| Heparan sulfate | Snoeijs et al. (73) | 2010 | Human renal transplantation | Enhanced production of heparan sulfate, which could mediate acute ischemic injury to the renal microvasculature. |

| Heparan sulfate | Ali et al. (1) | 2005 | Human renal transplantation | Expression of heparan sulfate was increased significantly during alloimmue response. |

| Hyaluronan/hyaluronic acid | Tuuminen et al. (79) | 2013 | Rat renal transplantation | Inhibition of hyaluronan induction prevented activation of innate and adaptive immune responses and protected the renal grafts. |

| Hyaluronan/hyaluronic acid | Zhang et al. (94) | 2000 | Rat renal transplantation | Blocking cell-cell interaction through hyaluronic acid interaction significantly prolonged rat allograft survival. |

TLR, Toll-like receptor; HMGB-1, high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1; HSP, heat shock protein.

HMGB-1.

HMGB-1 is a highly conserved nuclear factor with functions in nucleosome stabilization and promotion of DNA transcription. It contains three domains: box A, box B (both homologous DNA-binding motifs), and a negatively charged C terminus (2). HMGB-1 is predominantly located in the nuclei of most cells. HMGB-1 can also be released from the nucleus into the cytoplasm and extracellular milieu by both passive release from injured cells and active secretion by immune cells (30, 53). Extracellular HMGB-1 serves a different function, acting as a proinflammatory cytokine that mediates the inflammatory response to injury via various activations of receptors, including TLR-4 (30, 54).

Wu et al. (89) confirmed that HMGB-1 expression is upregulated after kidney IRI: it is secreted by necrotic or damaged tubular epithelial cells and acts as a DAMP. Apoptotic cells fail to activate monocytes due to HMGB-1 binding to chromatin. However, if this is suppressed by trichostatin A, HMGB-1 is able to act as an extracellular potent proinflammatory cytokine (6). This role has been confirmed in human kidney (HK)-2 cells. Treatment with recombinant HMGB-1 (rHMGB-1) leads to increased mRNA levels of cytokines involved in the pathology of IRI (41). HMGB1-induced cytokine upregulation reaches a similar level to that provoked by LPS treatment, suggesting the involvement of TLR-4 signaling. Administration of anti-HMGB1 antibody or rHMGB-1 to tubular epithelial cells from TLR-4-deficient mice, which block or augment HMGB-1 activity, respectively, does not result in further protection or damage in cells (89). It was therefore concluded that HMGB-1 mediates renal injury via TLR-4. Similarly, when HK-2 cells are stimulated with rHMGB-1, cytokine production is markedly blunted in cells with TLR-4 knockdown by transfection with TLR-4-specific small interfering (si) RNA compared with those transfected with nonspecific siRNA (41). Rat renal grafts have increased HMGB-1 release from nuclei and enhanced TLR-4 expression on renal tubules (97).

ECM components.

Biglycan is a small leucine-rich proteoglycan that consists of a core protein and two glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains, chondroitin and dermatan sulfate. From day 1 to day 5 after reperfusion, biglycan mRNA levels are significantly increased in mice tubular epithelial cells (88). The role of biglycan as a TLR-4 endogenous ligand was investigated by Schaefer et al. (72), who showed that biglycan was unable to promote the expression of TNF-α in TLR-4-deficient mutant macrophages in contrast to wild type.

Heparan sulfate is a polysaccharide that has been proposed to activate TLR-4. Johnson et al. (36) concluded that it promotes dendritic cell (DC) maturation in a TLR-4-dependent manner, since this process is blocked in C57BL/10ScNCr mice that have a deletion in chromosome 4 containing the TLR-4 locus.

Intracellular enzymes released during cellular rupture and tissue injury can cleave proteoglycans into smaller soluble polysaccharides. Using human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells transfected with TLR-4 expression plasmids, Okamura et al. (60) elucidated that fibronectin fragments containing the alternatively spliced exon coding for the extra domain A (EDA) can bind and activate TLR-4. EDA is capable of interacting with TLR-4 while other recombinant fragments or intact fibronectin fail to trigger cytokine and metalloproteinase secretion. Like LPS, EDA requires an accessory protein (MD-2) to elicit a maximal response.

Hyaluronan is a GAG that can be rapidly degraded in sites of inflammation to produce low-molecular-weight fragments of soluble hyaluronan (sHA). These are able to activate macrophages and DCs. Termeer et al. (76) deduced that this process is TLR-4 dependent since the administration of anti-TLR-4 antibodies blocked DC maturation and TNF- α production.

HSPs.

HSPs are molecular chaperones that facilitate the folding of proteins into their precise functional conformation and can be released from necrotic cells in the kidney. Their contribution to IRI has been observed in vital organs including the kidney: HSP60 and HSP70 activate TLR-4 on cardiomyocytes that are still viable in the ischemic area after reperfusion as well as on other immune cells (14). Endogenous HSP60 can be recognized by TLR-4 expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) after being internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis to activate APC function (80). TLR-4 is required for responsiveness to HSP70, as shown using HEK fibroblasts 293T (81). Interestingly, Wu et al. (88) found however that HSP70 mRNA levels in mice kidneys after ischemia-reperfusion remain no different from those in the sham-operated controls. This is different from HMGB-1, which showed that both active production and passive release were enhanced during renal IRI (88, 89). This indicated that HMGB-1 and HSPs might behave differently during ischemia-reperfusion injury. This certainly warrants more studies to further clarify the underlying molecular mechanisms.

The exact role of HSP70 in renal cell injury is still being debated. On the one hand, it is a TLR-4 ligand that initiates the inflammatory pathway which could lead to cell injury. Ben et al. (7) showed that heat shock protein-70 gp96 interacted with TLR-4 on renal tubular epithelial cells and this interaction was associated with hypoxia-induced apoptosis. On the other hand, overexpression of HSP70 has also been shown to be protective against renal injury through activating prompt repair and survival mechanisms. A study by Wang et al. (86) demonstrated that HSP70 promoted proximal tubule epithelial cell survival after acute ischemia caused by bilateral renal pedicle occlusion. HSP70 regulates the activity of Akt and GSK3β and reduces Bax activation after ischemia. Consistent with these findings, our recent work (98) demonstrated that exposure of xenon, an anesthetic gas, greatly enhanced the expression of HSP70 and conferred significant protection to renal allografts against ischemia-reperfusion injury and associated acute rejection.

Tamm-Horsfall protein.

Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP) is a glycoprotein which can modify TLR-4 expression and is found exclusively in the thick ascending limbs (18). It aggregates in casts formed during acute kidney injury, suggesting that it is responsible for tubular cast formation and tubular obstruction in acute kidney injury (87). It was found that THP could activate TLR-4 and enhance TNF-α production (70), indicating that THP might promote inflammation and enhance renal injury. However, contradictory evidence rendered the exact role of THP to be elusive. THP has been shown to have a renoprotective role: THP knockout mice kidneys manifested greater cellular necrosis, histological damage, and renal dysfunction after ischemic and reperfusion compared with wild-type mice (18). THP may regulate TLR-4 localization in tubular epithelial cells, perhaps promoting a more apical and less basolateral distribution, thereby reducing the interaction of TLR-4 with proinflammatory interstitial ligands (18).

TLR-4 Signaling Pathways

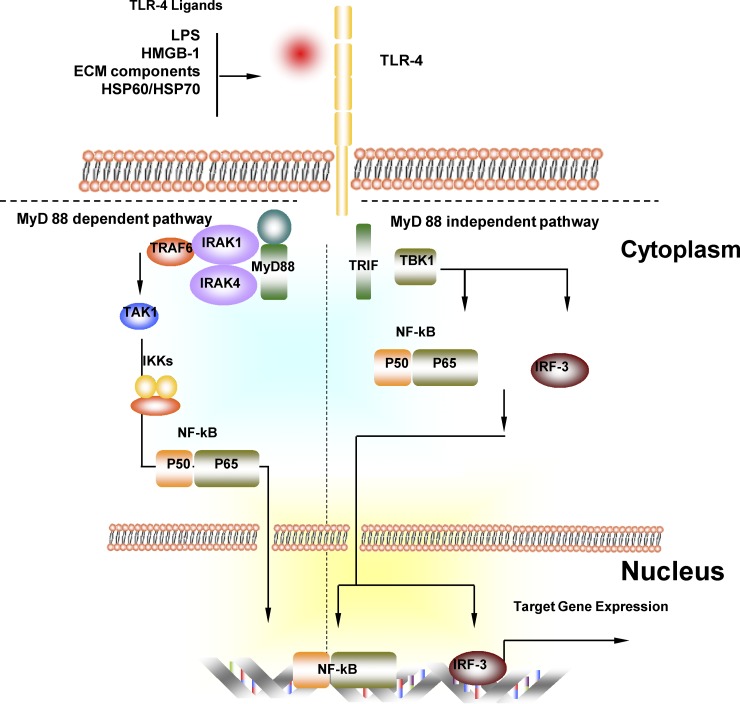

Ligand binding activates TLR-4, leading to downstream signaling via the Myd88-dependent and Myd88-independent signaling cascades. TLR-4 signaling triggered by different ligands can involve multiple components of these pathways. For example, biglycan activates p38 (72), while HSP60s activate p38, Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK1, JNK2), and the IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB) kinase (IKK) complex (80). sHA utilizes the p38/p42–44 pathway (76). Generally speaking, TLR-4 pathways could be divided into a Myd88-dependent pathway and Myd88-independent pathway (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MyD88)-dependent and MyD88-independent TLR-4 signaling pathway. In the MyD88-dependent pathway, activation of TLR-4 through TLR-4 ligand recruits and activates MyD88 and then IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-4. IRAK-4 phosphorylates IRAK-1, which recruits TNF-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6). TRAF6, ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (UEV1A, UBC13) and binding proteins (TAB1, TAB2) interact to activate TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1). Activation of TAK1 leads to the activation of the inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB kinase (IKK) complex, which releases NF-κB from its inhibitor and promotes its translocation into the nucleus. NF-κB is then translocated into the nuclear and initiates gene expression. In the Myd88-independent signaling pathway, TLR-4 activation leads to TRIF activation. TRIF recruits IKKε, which possibly forms a complex with TBK1 to activate transcription factors NF-κB and IFN-regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3). Gene expression is then initiated.

Myd88-dependent pathway.

Myd88 and an additional TIR domain-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP or MAL) recruit and activate members of the IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family (90). Wu et al. (88) consider this to be the dominant pathway mediating TLR-4-associated with kidney IRI since MyD88−/− mice were protected against kidney dysfunction and therefore targeting the Myd88-dependent pathway would serve as an effective strategy against renal IRI. Li et al. (48) observed that Myd88 knockout mice exhibit not only less tubular damage but also reduced TLR-4 mRNA levels, implying a feedback relationship between Myd88 and TLR-4.

Myd88-independent pathway.

This pathway is mediated by TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) (78). Another adaptor molecule, TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM), has been identified to provide the specificity for TLR-4 signaling. TRAM-deficient mice did not express the gene encoding IFN-β, so it was concluded that this molecule is required for the Myd88-independent pathway (91). Fitzgerald et al. (23) reported that two noncanonical IKK homologs downstream of TRIF, IKKε and TANK-binding kinase-1 (TBK1), are important for this pathway.

Effects of TLR-4 Activation in Ischemia-Reperfusion of the Renal Graft

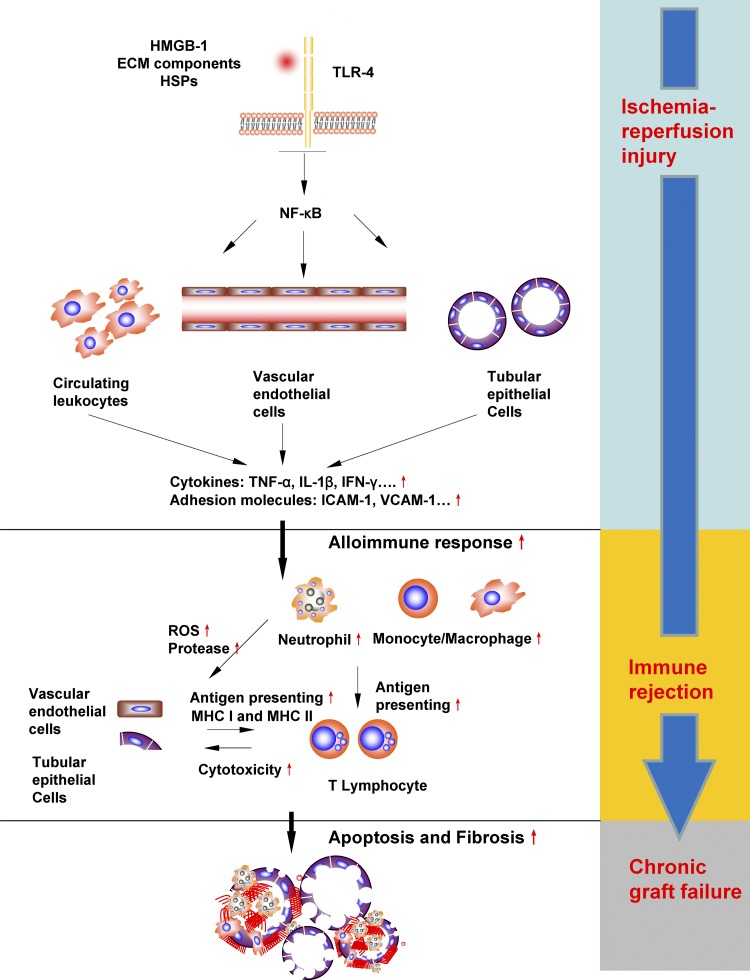

Activation of TLR-4 results in profound effects on renal grafts, including promoting injury to the tubular cells and sustaining the robust inflammation and fibrosis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of activation of TLR-4 in rIRI and associated consequences in renal grafts. Activation of TLR-4 on leukocytes, vascular endothelial cells, and tubular epithelial cells leads to increased productions of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, which elicits a strong inflammatory response in both the renal microvasculature and the interstitial space. This exacerbates the kidney damage already initiated during the ischemic phase through massive leukocyte infiltration and cytotoxicities. Increased endothelial cell and epithelial cells damages accelerate the antigen processing and presenting, and therefore immunogenicity is increased and immune rejection is promoted. Severe damaged tubules and vasculature would promote fibrosis, and all these molecular events predispose to chronic allograft failure

Promoting release of proinflammatory mediators.

The TLR-4-mediated cytokine cascade is triggered by the transcription of inflammatory genes. Cytokine release begins during the ischemic phase and is amplified upon reperfusion. Wu et al. (88) assert that the main proinflammatory cytokines upregulated following IRI are IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. This is accompanied by increased expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), chemokines involved in the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages, respectively. It has been demonstrated in experiments with TLR-4-deficient animal IRI models that this upregulation is attenuated, TNF-α is absent, and that there is limited increase in IL-6, IL-1β and MCP-1 protein levels compared with in wide-type mice (88).

Facilitating leukocyte migration and infiltration.

Vascular endothelial activation is marked by the expression of adhesion molecules, which facilitate leukocyte migration and infiltration. Leukocyte rolling is mediated by three transmembrane receptors: E-selectin, P-selectin, and L-selectin. Firm adhesion following rolling is mediated by binding of ICAM-1 on endothelial cells to lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1 or CD11a/CD18) present on leukocytes. This facilitates diapedesis and leukocyte trafficking into the renal interstitium (44, 46).

Chen et al. (11) showed that TLR-4 signaling is a requirement for the expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin. They demonstrated increased expression of adhesion molecules during ischemic kidney injury was absent in TLR-4 knockout endothelia, and transgenic knockout of TLR-4 ameliorates ischemic injury and inflammation.

Activating innate and adaptive immune system.

TLR-4 was widely expressed on immune cells in the innate immune system, and ligand binding to TLR-4 expressed on infiltrating leukocytes leads to cellular activation. Neutrophils release additional reactive oxygen species, secrete proteases, and can obstruct the renal microvasculature; hence they are regarded as the primary mediators of tissue injury (33). Infiltrating monocyte/macrophages release proteolytic enzymes and inflammatory mediators including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ (35). Local TLR-4 activation by endogenous ligands connected graft damage and subsequent cytokine/chemokine release, leading to activation of innate immunity (8, 41). It has been shown that neutrophil and macrophage infiltration was greatly reduced in TLR-4 knockout mice with renal IRI (88). Moreover, the innate immune system induces adaptive immune responses via antigen presentation and enhances neutrophil infiltration. It is naturally accepted that suppressing innate immunity through inhibiting TLR-4 might agitate the adaptive immune system to a less extent and promote the graft acceptance or tolerance. Dendritic cells (DCs) are APCs known to link the innate and adaptive immune responses. In kidney transplantation, donor renal DCs (rDCs) present graft peptides, migrate to draining lymphoid tissue, and activate alloreactive T cells. Allopeptides derived from their MHC molecules can also be presented on recipient DCs (47). Furthermore, DCs play a major role in the early pathophysiology of IRI by mediating cytokine production. CDC11c+ cells (most likely DCs) secrete TNF, CCL5, IL-6, and MCP-1, while TNF production within 24 h of IRI is predominately driven by the F4/80+ DC population, the “first responders” in the inflammatory response (16). Moreover, TLR-4 has been reported to mediate proinflammatory dendritic cell differentiation in humans and promote induction of costimulatory molecule expression (40). It was also suggested that TLR-4 induces dendritic cells with fully mature phenotypes, which prime CD8+ T cells more efficiently (64).

Sustaining tubular necrosis and potentiating renal fibrosis.

The generation and release of TLR-4 ligands from injured tubular cells cause activation and upregulation of TLR-4, which in turn induce a robust inflammatory responses and cause widespread tubular necrosis, loss of the brush border, cast formation, and tubular dilatation at the corticomedullary junction (88). Robust inflammation is known to potentiate tissue fibrosis (52). A recent study (39) has established that infiltrating macrophages mediated persistent inflammation and fibrosis after IRI. Constantly increased expression of profibrotic protein TGF-β1 was found in kidneys several weeks after the initiation of IRI, and monocyte-macrophage depletion suppressed the increase. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that TLR-4 initiates an exaggerated proinflammatory response during renal IRI, and lower levels of infiltrating cells were found in TLR4−/− mice compared with wild-type mice (66).

The association between TLR-4 and fibrosis in the setting of renal graft ischemia-reperfusion might be the case, but supporting evidence is limited. It was demonstrated that TLR-, MyD88-, and TRIF-deficient mice recipients showed a significant reduction in fibrosis (84) in chronic allograft nephropathy, reflected by significantly reduced α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen I and III accumulation. The deposition of fibrinogen (8), a fibrotic marker, in renal allografts correlated well with renal TLR-4 expression, indicating that activation of TLR-4 leads to induction of renal fibrosis.

Studies in other fibrotic renal disease models could provide further evidence supporting the potential role of TLR-4 in the fibrotic pathway. Campbell et al. (10) demonstrate a novel role for TLR-4 signaling in obstruction-induced renal fibrogenesis as such mice with intact TLR-4 signaling demonstrate a significant increase in TLR-4 expression, α-SMA expression, fibroblast and collagen accumulation, and interstitial fibrosis after unilateral ureteral obstruction. These pathological features were not found in TLR-4-deficient mice. Similarly, it was revealed that renal fibrosis is clearly attenuated in TLR-4 knockout mice after unilateral ureteral obstruction, with reduced collagen deposition in the kidney (65).

However, a final conclusion is difficult to draw since chronic inflammation is always associated with repeated repair and connective tissue accumulation in vital organs. It was demonstrated that TLR-4 enhanced inflammatory signaling and activation of fibrosis in the kidneys (8, 10), suggesting that TLR-4 could function as a molecular link between proinflammatory and profibrogenic signals in renal tissue. However, it is questionable whether TLR-4 alone could induce fibrogenesis independently of inflammation. It has been demonstrated in a model of systemic sclerosis that fibroblasts produced profibrotic chemokines such as MCP-1 in a TLR-4-dependent manner (22). Furthermore, a study by Pulskens et al. (65) showed TLR-4-deficient primary tubular epithelial cells and myofibroblasts produced significantly less type I collagen mRNA after TGF-β stimulation than did wild-type cells. This indicated that, in addition to sustaining the inflammation necessary for fibrosis, TLR-4 promoted renal fibrosis through enhancing the susceptibility and responsiveness of renal cells to TGF-β.

Allograft Rejection

The association of renal mRNA TLR-4 expression with allograft rejection in renal transplant recipients has been investigated by Kwon et al. (43), who found an increased TLR-4 expression in those patients with acute rejection and chronic rejection compared with control patients. A further study by Braudeau et al. (9) investigated renal transplant recipients with chronic rejection and transplant glomerulopathy. Renal grafts from patients with chronic rejection were found to express greater TLR-4 mRNA than grafts with stable function and normal histology, suggesting a detrimental effect of increased TLR-4 expression on transplant outcome.

An elegant study by Hwang et al. (32) evaluated the possible association between the TLR-4 and TLR-3 polymorphisms of donor-recipient pairs and acute rejection after living donor kidney transplantation. A significant difference was found in the genotype distributions of both recipient and donor TLR-4 between the control and acute rejection groups. These findings implied the importance of TLR-4 in the pathogenesis of acute rejection in kidney transplantation.

Several studies have investigated the role of TLR-4 in allograft rejection after renal transplantation by looking at the effects of the Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile TLR-4 gene polymorphisms. Studies by Ducloux et al. (17) and Nogueira et al. (59) have demonstrated that kidneys transplanted to recipients with TLR-4 polymorphisms have been shown to manifest fewer acute rejection episodes than those from donors with wild-type TLR-4 (although the findings of the latter study did not achieve statistical significance). Although allograft rejection was explored in these studies, the results highlighted the potential difference in the contribution of donor and recipient to renal graft IRI, since the severity of renal graft IRI correlated strongly with the occurrence of acute immune rejection and later graft failure (98). The bone marrow chimera findings (66, 88) described previously should be more supportive in providing an explanation in this case, and they implied that donor graft parenchymal TLR-4 may have a different level of contribution compared with TLR-4 on infiltrating leukocytes derived from recipient bone marrow. One study, however, demonstrated that transplants from cadaveric donors with either of the polymorphisms (not the recipients) exhibited lower rates of acute rejection (62). Interestingly, this reduction in acute rejection did not translate into increased long-term survival, perhaps due to small sample size and short-term follow-up. Another study by Fekete et al. (20) investigating long-term survival did find, however, that the Asp299Gly (D299G) TLR-4 polymorphism occurred more frequently in patients with 15-yr long-term survival after transplantation compared with those with graft loss due to acute rejection. Consistent with this finding, a recently published study (21) shed light on the mechanism of inhibition of TLR-4 signaling by the Asp299Gly (D299G) polymorphism. Human embryonic kidney cells transfected with D299G TLR-4 exhibited impaired LPS-induced activation of NF-κB, whereas other mutations of TLR-4, such as Thr(399)Ile (T399I) are not associated with significant inhibition. Contrary to wild-type TLR-4, mouse macrophages with expression of the TLR4D299G mutants are unable to elicit LPS-mediated induction of TNF-α and IFN-β mRNA.

Mutlubas et al. (58) also investigated the role of TLR-4 polymorphisms in chronic allograft nephropathy (CAN; progressive decline in renal function with proteinuria and hypertension) in a cohort of pediatric renal transplant patients. In this study, it was found that the Thr399Ile (T399I) polymorphism and Ile allele were only present in those recipients that did not manifest CAN and that patients who developed CAN did not carry this genotype, although these results were not statistically significant. Although this study primarily investigated chronic allograft nephropathy, it provides important indications for renal graft IRI since graft IRI is a critical factor for the development of CAN (95). All of these studies taken together strongly suggest that reduced TLR-4 signaling may have beneficial effects on clinical outcomes after kidney transplantation.

Therapeutic Interventions Targeting TLR-4

Several previous studies showed the renoprotective outcome of TLR-4 knockout. TLR-4−/− mice were protected against the effects of renal IRI; they demonstrated preserved renal function, reduced numbers of infiltrating neutrophils and macrophages, and less tubular damage compared with WT mice (66). It is important to note that TLR-2 has also been implicated in IRI. TLR-2-targeted deletions provide renoprotection in mice (84) due to the potent effects of TLR-2 signaling on immune system activation (84, 85). However, a previous study (69) using hypoxic tubular epithelial cells demonstrated that deletions of both the TLR-4 and TLR-2 locus did not give any further protection compared with the single deletion of either receptor. Therefore, proteins that block ligand binding to TLR-4 or target downstream signaling components may have therapeutic potential.

Mice treated with anti-HMGB-1-neutralizing antibody exhibit diminished tubular damage in kidney IRI models compared with untreated animals. Reduced levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 mRNA attenuated leukocyte infiltration and reduced apoptosis of TECs are observed characteristics in mice treated before and soon after ischemia, and following reperfusion (89). Recently, adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) has been shown to be promising in treating renal IRI by modulating TLRs (38). PACAP belongs to the vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)-glucagon-growth hormone releasing factor-secretin superfamily (82). It is an endogenous pleiotropic peptide with renoprotective effects through inhibiting innate immune responses (25) and oxidative stress (83). PACAP has been shown to inhibit TLR-4 through suppressing both Myd88-dependent and -independent pathways (34, 48, 75).

TLR-4 inhibitors are under development, since a direct receptor blockade would potentially offer greater protection than targeting individual ligands and downstream effectors with redundant functions (41). Eritoran, a synthetic structural analog of the lipid A portion of LPS, has recently been identified as a potent TLR-4 antagonist in rat IRI models (51). further investigation of endogenous TLR-4 negative regulators can lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches for IRI. For example, intracellular Toll-interacting protein (TOLLIP) can associate with TLR-4 and suppress the phosphorylation and activity of IRAK (93). The RP105-MD-1 complex specifically inhibits TLR-4-signaling in HEK 293 cells and DCs (15). Single immunoglobulin interleukin-1 receptor-related protein (SIGIRR) associates with TLR-4 and forms a complex with Myd88, IRAK4, IRAK, and TRAF6 to inhibit signaling (67). Other regulators include IRAKM, IRAK2c, IRAK2d, soluble TLR-4, A20, and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor (TRAILR) (49). A study by Gu et al. (29) showed the α2-adrenoceptor agonist dexmedetomidine protected the mice against ischemia-reperfusion induced kidney injury, dexmedetomidine reduced plasma HMGB-1 elevation and also decreased TLR-4 expression in tubular cells. Pre- or posttreatment with dexmedetomidine improved tubular architecture and function following renal ischemia. Recently, we have demonstrated that xenon exposure to either donor or recipient led to activation of a range of protective proteins. This treatment diminished cytoplasmic translocation of HMGB-1 and suppressed TLR-4/NF-κB activation, consequently, DGF was attenuated and graft survival was enhanced (97). Furthermore, this treatment remarkably attenuated alloimmune responses associated with IRI in renal allografts and conferred optimal protection when combined with cyclosporine A (98).

Clinical Implications for TLR-4 Expression After IRI in Renal Grafts

The principal clinical manifestation of renal ischemia-reperfusion in kidney transplantation is DGF (77), a form of acute renal failure that leads to posttransplantation oliguria (63) and is associated with increased acute rejection episodes, graft loss (57), prolonged hospitalization, greater complexity of management, and higher cost (68). As allografts from deceased-donors are exposed to longer periods of ischemia, they are associated with a higher incidence of DGF compared with allografts from live donors (63). A study by Gok et al. (27) showed that the greatest amount of free radical generation and tissue injury at reperfusion was observed in transplants from non-heart-beating donors (NHBD) compared with those from heart-beating donors (HBD) and live donors (LD). Preclinical studies have aimed to establish the contribution of donor and recipient TLR-4 to graft injury. For example, a study by Krüger et al. (41) analyzing biopsies from kidney grafts exposed to cold ischemia showed that TLR-4 expression is notably higher in the proximal and distal tubular cells of deceased-donor kidneys compared with living-donor ones. Mutations in the TLR-4 gene leading to altered receptor function may affect the outcome of transplantation. Asp299Gly and Thr399Ile are two cosegregating missense single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the TLR-4 gene that are associated with reduced inflammatory responses to LPS (4). DGF was less frequent in recipients of kidneys from TLR-4-mutant donors. This was possibly due to a blunted expression of MCP-1 and TNF-α, as well as an increased expression of the anti-inflammatory and protective heme oxygenase-1 gene (41). Furthermore, renal graft IRI is positively associated with development of human allograft rejection (55) and development of chronic graft failure (45). All these different types of injury are associated with TLR-4, and the results obtained from the animal models of acute ischemic injury are of vital relevance to these clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

There is strong evidence that TLR-4 has a detrimental role in kidney IRI as it triggers an inflammatory and maladaptive immune response that aggravates tissue injury. Following ischemia-reperfusion, endogenous ligands are released that interact with TLR-4 expressed by vascular endothelial cells, tubular epithelial cells, and leukocytes, the latter of which migrate into the graft as a result of the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules (which also results from TLR-4 signaling). Now that studies have demonstrated that the full development of kidney ischemia-reperfusion is TLR-4 dependent, treatments targeting upstream and downstream components of TLR-4 signaling should be further investigated to improve outcomes after renal transplantation. Given the pivotal role of TLR-4 in IRI and associated delayed graft function and allograft rejection, it is naturally reasoned that TLR-4 inhibition could serve as the target of pharmacological agents directed toward optimizing renal graft survival.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the British Medical Research Council (MRC), The Developmental Pathway Funding Scheme (DPFS) program (project grant G802392), and the National Natural Science Foundation, Beijing, China (81170414).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: H.Z. and A.J.G. prepared figures; H.Z., J.S.P., K.L., A.J.G., and D.M. drafted manuscript; H.Z., J.S.P., K.L., A.J.G., and D.M. approved final version of manuscript; D.M. provided conception and design of research; D.M. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of A. J. T. George: Brunel Univ. London, Uxbridge, Middlesex, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali S, Malik G, Burns A, Robertson H, Kirby JA. Renal transplantation: examination of the regulation of chemokine binding during acute rejection. Transplantation 79: 672–679, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson U, Erlandsson-Harris H, Yang H, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a DNA-binding cytokine. J Leukoc Biol 72: 1084–1091, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrade-Oliveira V, Campos EF, Goncalves-Primo A, Grenzi PC, Medina-Pestana JO, Tedesco-Silva H, Gerbase-DeLima M. TLR4 mRNA levels as tools to estimate risk for early posttransplantation kidney graft dysfunction. Transplantation 94: 589–595, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC, Zabner J, Kline JN, Jones M, Frees K, Watt JL, Schwartz DA. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat Genet 25: 187–191, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkinson SJ, Hosford MA, Molitoris BA. Mechanism of actin polymerization in cellular ATP depletion. J Biol Chem 279: 5194–5199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell CW, Jiang W, Reich CF, 3rd, Pisetsky DS. The extracellular release of HMGB1 during apoptotic cell death. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C1318–C1325, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben Mkaddem S, Pedruzzi E, Werts C, Coant N, Bens M, Cluzeaud F, Goujon JM, Ogier-Denis E, Vandewalle A. Heat shock protein gp96 and NAD(P)H oxidase 4 play key roles in Toll-like receptor 4-activated apoptosis during renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell Death Differ 17: 1474–1485, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergler T, Hoffmann U, Bergler E, Jung B, Banas MC, Reinhold SW, Kramer BK, Banas B. Toll-like receptor 4 in experimental kidney transplantation: early mediator of endogenous danger signals. Nephron Exp Nephrol 121: e59–e70, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braudeau C, Ashton-Chess J, Giral M, Dugast E, Louis S, Pallier A, Braud C, Moreau A, Renaudin K, Soulillou JP, Brouard S. Contrasted blood and intragraft toll-like receptor 4 mRNA profiles in operational tolerance versus chronic rejection in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 86: 130–136, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell MT, Hile KL, Zhang H, Asanuma H, Vanderbrink BA, Rink RR, Meldrum KK. Toll-like receptor 4: a novel signaling pathway during renal fibrogenesis. J Surg Res 168: e61–e69, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, John R, Richardson JA, Shelton JM, Zhou XJ, Wang Y, Wu QQ, Hartono JR, Winterberg PD, Lu CY. Toll-like receptor 4 regulates early endothelial activation during ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 79: 288–299, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Hartono JR, John R, Bennett M, Zhou XJ, Wang Y, Wu Q, Winterberg PD, Nagami GT, Lu CY. Early interleukin 6 production by leukocytes during ischemic acute kidney injury is regulated by TLR4. Kidney Int 80: 504–515, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Matzuk MM, Zhou XJ, Lu CY. Endothelial pentraxin 3 contributes to murine ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 82: 1195–1207, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chong AJ, Shimamoto A, Hampton CR, Takayama H, Spring DJ, Rothnie CL, Yada M, Pohlman TH, Verrier ED. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates ischemia/reperfusion injury of the heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 128: 170–179, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Divanovic S, Trompette A, Atabani SF, Madan R, Golenbock DT, Visintin A, Finberg RW, Tarakhovsky A, Vogel SN, Belkaid Y, Kurt-Jones EA, Karp CL. Negative regulation of Toll-like receptor 4 signaling by the Toll-like receptor homolog RP105. Nat Immunol 6: 571–578, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong X, Swaminathan S, Bachman LA, Croatt AJ, Nath KA, Griffin MD. Resident dendritic cells are the predominant TNF-secreting cell in early renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Kidney Int 71: 619–628, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ducloux D, Deschamps M, Yannaraki M, Ferrand C, Bamoulid J, Saas P, Kazory A, Chalopin JM, Tiberghien P. Relevance of Toll-like receptor-4 polymorphisms in renal transplantation. Kidney Int 67: 2454–2461, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Achkar TM, Wu XR, Rauchman M, McCracken R, Kiefer S, Dagher PC. Tamm-Horsfall protein protects the kidney from ischemic injury by decreasing inflammation and altering TLR4 expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F534–F544, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion–from mechanism to translation. Nat Med 17: 1391–1401, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fekete A, Viklicky O, Hubacek JA, Rusai K, Erdei G, Treszl A, Vitko S, Tulassay T, Heemann U, Reusz G, Szabo AJ. Association between heat shock protein 70s and toll-like receptor polymorphisms with long-term renal allograft survival. Transpl Int 19: 190–196, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Figueroa L, Xiong Y, Song C, Piao W, Vogel SN, Medvedev AE. The Asp299Gly polymorphism alters TLR4 signaling by interfering with recruitment of MyD88 and TRIF. J Immunol 188: 4506–4515, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fineschi S, Goffin L, Rezzonico R, Cozzi F, Dayer JM, Meroni PL, Chizzolini C. Antifibroblast antibodies in systemic sclerosis induce fibroblasts to produce profibrotic chemokines, with partial exploitation of Toll-like receptor 4. Arthritis Rheum 58: 3913–3923, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, Coyle AJ, Liao SM, Maniatis T. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 4: 491–496, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gailit J, Colflesh D, Rabiner I, Simone J, Goligorsky MS. Redistribution and dysfunction of integrins in cultured renal epithelial cells exposed to oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F149–F157, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganea D, Rodriguez R, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide: players in innate and adaptive immunity. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 49: 127–142, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gluba A, Banach M, Hannam S, Mikhailidis DP, Sakowicz A, Rysz J. The role of Toll-like receptors in renal diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol 6: 224–235, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gok MA, Shenton BK, Pelsers M, Whitwood A, Mantle D, Cornell C, Peaston R, Rix D, Jaques BC, Soomro NA, Manas DM, Talbot D. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in cadaveric nonheart beating, cadaveric heart beating and live donor renal transplants. J Urol 175: 641–647, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon EJ, Ladner DP, Caicedo JC, Franklin J. Disparities in kidney transplant outcomes: a review. Semin Nephrol 30: 81–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu J, Sun P, Zhao H, Watts HR, Sanders RD, Terrando N, Xia P, Maze M, Ma D. Dexmedetomidine provides renoprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Crit Care 15: R153, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris HE, Andersson U, Pisetsky DS. HMGB1: a multifunctional alarmin driving autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauet T, Eugene M. A new approach in organ preservation: potential role of new polymers. Kidney Int 74: 998–1003, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang YH, Ro H, Choi I, Kim H, Oh KH, Hwang JI, Park MH, Kim S, Yang J, Ahn C. Impact of polymorphisms of TLR4/CD14 and TLR3 on acute rejection in kidney transplantation. Transplantation 88: 699–705, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang HR, Rabb H. The innate immune response in ischemic acute kidney injury. Clin Immunol 130: 41–50, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji H, Zhang Y, Shen XD, Gao F, Huang CY, Abad C, Busuttil RW, Waschek JA, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Neuropeptide PACAP in mouse liver ischemia and reperfusion injury: immunomodulation by the cAMP-PKA pathway. Hepatology 57: 1225–1237, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jo SK, Sung SA, Cho WY, Go KJ, Kim HK. Macrophages contribute to the initiation of ischaemic acute renal failure in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1231–1239, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson GB, Brunn GJ, Kodaira Y, Platt JL. Receptor-mediated monitoring of tissue well-being via detection of soluble heparan sulfate by Toll-like receptor 4. J Immunol 168: 5233–5239, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson GB, Brunn GJ, Tang AH, Platt JL. Evolutionary clues to the functions of the Toll-like family as surveillance receptors. Trends Immunol 24: 19–24, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim BS, Lim SW, Li C, Kim JS, Sun BK, Ahn KO, Han SW, Kim J, Yang CW. Ischemia-reperfusion injury activates innate immunity in rat kidneys. Transplantation 79: 1370–1377, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko GJ, Boo CS, Jo SK, Cho WY, Kim HK. Macrophages contribute to the development of renal fibrosis following ischaemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 842–852, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolanowski ST, Dieker MC, Lissenberg-Thunnissen SN, van Schijndel GM, van Ham SM, Ten Brinke A. TLR4-mediated pro-inflammatory dendritic cell differentiation in humans requires the combined action of MyD88 and TRIF. Innate Immun [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kruger B, Krick S, Dhillon N, Lerner SM, Ames S, Bromberg JS, Lin M, Walsh L, Vella J, Fischereder M, Kramer BK, Colvin RB, Heeger PS, Murphy BT, Schroppel B. Donor Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3390–3395, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuboki S, Schuster R, Blanchard J, Pritts TA, Wong HR, Lentsch AB. Role of heat shock protein 70 in hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1141–G1149, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwon J, Park J, Lee D, Kim YS, Jeong HJ. Toll-like receptor expression in patients with renal allograft dysfunction. Transplant Proc 40: 3479–3480, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 678–689, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li C, Yang CW. The pathogenesis and treatment of chronic allograft nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 5: 513–519, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li L, Okusa MD. Blocking the immune response in ischemic acute kidney injury: the role of adenosine 2A agonists. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 432–444, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li L, Okusa MD. Macrophages, dendritic cells, and kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. Semin Nephrol 30: 268–277, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li M, Khan AM, Maderdrut JL, Simon EE, Batuman V. The effect of PACAP38 on MyD88-mediated signal transduction in ischemia-/hypoxia-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Nephrol 32: 522–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liew FY, Xu D, Brint EK, O'Neill LA. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 446–458, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim SW, Li C, Ahn KO, Kim J, Moon IS, Ahn C, Lee JR, Yang CW. Cyclosporine-induced renal injury induces toll-like receptor and maturation of dendritic cells. Transplantation 80: 691–699, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu M, Gu M, Xu D, Lv Q, Zhang W, Wu Y. Protective effects of Toll-like receptor 4 inhibitor eritoran on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplant Proc 42: 1539–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu Y. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 7: 684–696, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 331–342, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mantell LL, Parrish WR, Ulloa L. Hmgb-1 as a therapeutic target for infectious and inflammatory disorders. Shock 25: 4–11, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mikhalski D, Wissing KM, Ghisdal L, Broeders N, Touly M, Hoang AD, Loi P, Mboti F, Donckier V, Vereerstraeten P, Abramowicz D. Cold ischemia is a major determinant of acute rejection and renal graft survival in the modern era of immunosuppression. Transplantation 85: S3–S9, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Molitoris BA, Geerdes A, McIntosh JR. Dissociation and redistribution of Na+,K+-ATPase from its surface membrane actin cytoskeletal complex during cellular ATP depletion. J Clin Invest 88: 462–469, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moreira P, Sa H, Figueiredo A, Mota A. Delayed renal graft function: risk factors and impact on the outcome of transplantation. Transplant Proc 43: 100–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mutlubas F, Mir S, Berdeli A, Ozkayin N, Sozeri B. Association between Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 gene polymorphisms with chronic allograft nephropathy in Turkish children. Transplant Proc 41: 1589–1593, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nogueira E, Ozaki KS, Macusso GD, Quarim RF, Camara NO, Pacheco-Silva A. Incidence of donor and recipient Toll-like receptor-4 polymorphisms in kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc 39: 412–414, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Okamura Y, Watari M, Jerud ES, Young DW, Ishizaka ST, Rose J, Chow JC, Strauss JF., 3rd The extra domain A of fibronectin activates Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem 276: 10229–10233, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Neill LA, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 353–364, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palmer SM, Burch LH, Mir S, Smith SR, Kuo PC, Herczyk WF, Reinsmoen NL, Schwartz DA. Donor polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor-4 influence the development of rejection after renal transplantation. Clin Transplant 20: 30–36, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perico N, Cattaneo D, Sayegh MH, Remuzzi G. Delayed graft function in kidney transplantation. Lancet 364: 1814–1827, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pufnock JS, Cigal M, Rolczynski LS, Andersen-Nissen E, Wolfl M, McElrath MJ, Greenberg PD. Priming CD8+ T cells with dendritic cells matured using TLR4 and TLR7/8 ligands together enhances generation of CD8+ T cells retaining CD28. Blood 117: 6542–6551, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pulskens WP, Rampanelli E, Teske GJ, Butter LM, Claessen N, Luirink IK, van der Poll T, Florquin S, Leemans JC. TLR4 promotes fibrosis but attenuates tubular damage in progressive renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1299–1308, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pulskens WP, Teske GJ, Butter LM, Roelofs JJ, van der Poll T, Florquin S, Leemans JC. Toll-like receptor-4 coordinates the innate immune response of the kidney to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One 3: e3596, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qin J, Qian Y, Yao J, Grace C, Li X. SIGIRR inhibits interleukin-1 receptor- and toll-like receptor 4-mediated signaling through different mechanisms. J Biol Chem 280: 25233–25241, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Requiao-Moura LR, Durao Mde S, Tonato EJ, Matos AC, Ozaki KS, Camara NO, Pacheco-Silva A. Effects of ischemia and reperfusion injury on long-term graft function. Transplant Proc 43: 70–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rusai K, Sollinger D, Baumann M, Wagner B, Strobl M, Schmaderer C, Roos M, Kirschning C, Heemann U, Lutz J. Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pediatr Nephrol 25: 853–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saemann MD, Weichhart T, Zeyda M, Staffler G, Schunn M, Stuhlmeier KM, Sobanov Y, Stulnig TM, Akira S, von Gabain A, von Ahsen U, Horl WH, Zlabinger GJ. Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein links innate immune cell activation with adaptive immunity via a Toll-like receptor-4-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest 115: 468–475, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salahudeen AK. Cold ischemic injury of transplanted kidneys: new insights from experimental studies. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F181–F187, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schaefer L, Babelova A, Kiss E, Hausser HJ, Baliova M, Krzyzankova M, Marsche G, Young MF, Mihalik D, Gotte M, Malle E, Schaefer RM, Grone HJ. The matrix component biglycan is proinflammatory and signals through Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in macrophages. J Clin Invest 115: 2223–2233, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Snoeijs MG, Vink H, Voesten N, Christiaans MH, Daemen JW, Peppelenbosch AG, Tordoir JH, Peutz-Kootstra CJ, Buurman WA, Schurink GW, van Heurn LW. Acute ischemic injury to the renal microvasculature in human kidney transplantation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1134–F1140, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 21: 335–376, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tang Y, Lv B, Wang H, Xiao X, Zuo X. PACAP inhibit the release and cytokine activity of HMGB1 and improve the survival during lethal endotoxemia. Int Immunopharmacol 8: 1646–1651, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Termeer C, Benedix F, Sleeman J, Fieber C, Voith U, Ahrens T, Miyake K, Freudenberg M, Galanos C, Simon JC. Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med 195: 99–111, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tilney NL, Guttmann RD. Effects of initial ischemia/reperfusion injury on the transplanted kidney. Transplantation 64: 945–947, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsan MF, Gao B. Endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors. J Leukoc Biol 76: 514–519, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tuuminen R, Nykanen AI, Saharinen P, Gautam P, Keranen MA, Arnaudova R, Rouvinen E, Helin H, Tammi R, Rilla K, Krebs R, Lemstrom KB. Donor simvastatin treatment prevents ischemia-reperfusion and acute kidney injury by preserving microvascular barrier function. Am J Transplant 13: 2019–2034, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vabulas RM, Ahmad-Nejad P, da Costa C, Miethke T, Kirschning CJ, Hacker H, Wagner H. Endocytosed HSP60s use toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 to activate the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor signaling pathway in innate immune cells. J Biol Chem 276: 31332–31339, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vabulas RM, Ahmad-Nejad P, Ghose S, Kirschning CJ, Issels RD, Wagner H. HSP70 as endogenous stimulus of the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor signal pathway. J Biol Chem 277: 15107–15112, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vaudry D, Gonzalez BJ, Basille M, Yon L, Fournier A, Vaudry H. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: from structure to functions. Pharmacol Rev 52: 269–324, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vaudry D, Pamantung TF, Basille M, Rousselle C, Fournier A, Vaudry H, Beauvillain JC, Gonzalez BJ. PACAP protects cerebellar granule neurons against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Eur J Neurosci 15: 1451–1460, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang S, Schmaderer C, Kiss E, Schmidt C, Bonrouhi M, Porubsky S, Gretz N, Schaefer L, Kirschning CJ, Popovic ZV, Grone HJ. Recipient Toll-like receptors contribute to chronic graft dysfunction by both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling. Dis Model Mech 3: 92–103, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang S, Villablanca EJ, De Calisto J, Gomes DC, Nguyen DD, Mizoguchi E, Kagan JC, Reinecker HC, Hacohen N, Nagler C, Xavier RJ, Rossi-Bergmann B, Chen YB, Blomhoff R, Snapper SB, Mora JR. MyD88-dependent TLR1/2 signals educate dendritic cells with gut-specific imprinting properties. J Immunol 187: 1412–150, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Z, Gall JM, Bonegio RG, Havasi A, Hunt CR, Sherman MY, Schwartz JH, Borkan SC. Induction of heat shock protein 70 inhibits ischemic renal injury. Kidney Int 79: 861–870, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wangsiripaisan A, Gengaro PE, Edelstein CL, Schrier RW. Role of polymeric Tamm-Horsfall protein in cast formation: oligosaccharide and tubular fluid ions. Kidney Int 59: 932–940, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu H, Chen G, Wyburn KR, Yin J, Bertolino P, Eris JM, Alexander SI, Sharland AF, Chadban SJ. TLR4 activation mediates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 117: 2847–2859, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu H, Ma J, Wang P, Corpuz TM, Panchapakesan U, Wyburn KR, Chadban SJ. HMGB1 contributes to kidney ischemia reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1878–1890, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Sanjo H, Uematsu S, Kaisho T, Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kobayashi M, Fujita T, Takeda K, Akira S. Essential role for TIRAP in activation of the signalling cascade shared by TLR2 and TLR4. Nature 420: 324–329, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Uematsu S, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Akira S. TRAM is specifically involved in the Toll-like receptor 4-mediated MyD88-independent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol 4: 1144–1150, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang H, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Palmblad K, Wang H, Ochani M, Li J, Lu B, Chavan S, Rosas-Ballina M, Al-Abed Y, Akira S, Bierhaus A, Erlandsson-Harris H, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. A critical cysteine is required for HMGB1 binding to Toll-like receptor 4 and activation of macrophage cytokine release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 11942–11947, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang G, Ghosh S. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor-mediated signaling by Tollip. J Biol Chem 277: 7059–7065, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhang W, Gao L, Qi S, Liu D, Xu D, Peng J, Daloze P, Chen H, Buelow R. Blocking of CD44-hyaluronic acid interaction prolongs rat allograft survival. Transplantation 69: 665–667, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhao H, Luo X, Zhou Z, Liu J, Tralau-Stewart C, George AJ, Ma D. Early treatment with xenon protects against the cold ischemia associated with chronic allograft nephropathy in rats. Kidney Int 85: 112–23, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhao H, Ning J, Savage S, Kang H, Lu K, Zheng X, George AJ, Ma D. A novel strategy for preserving renal grafts in an ex vivo setting: potential for enhancing the marginal donor pool. FASEB J 27: 4822–33, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhao H, Watts HR, Chong M, Huang H, Tralau-Stewart C, Maxwell PH, Maze M, George AJ, Ma D. Xenon treatment protects against cold ischemia associated delayed graft function and prolongs graft survival in rats. Am J Transplant 13: 2006–2018, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhao H, Yoshida A, Xiao W, Ologunde R, O'Dea KP, Takata M, Tralau-Stewart C, George AJ, Ma D. Xenon treatment attenuates early renal allograft injury associated with prolonged hypothermic storage in rats. FASEB J 27: 4076–4088, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]