Abstract

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is frequently used in infants with postoperative cardiopulmonary failure. ECMO also suppresses circulating triiodothyronine (T3) levels and modifies myocardial metabolism. We assessed the hypothesis that T3 supplementation reverses ECMO-induced metabolic abnormalities in the immature heart. Twenty-two male Yorkshire pigs (age: 25–38 days) with ECMO received [2-13C]lactate, [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate (medium-chain fatty acid), and [U-13C]long-chain fatty acids as metabolic tracers either systemically (totally physiological intracoronary concentration) or directly into the coronary artery (high substrate concentration) for the last 60 min of each protocol. NMR analysis of left ventricular tissue determined the fractional contribution of these substrates to the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Fifty percent of the pigs in each group received intravenous T3 supplement (bolus at 0.6 μg/kg and then continuous infusion at 0.2 μg·kg−1·h−1) during ECMO. Under both substrate loading conditions, T3 significantly increased the fractional contribution of lactate with a marginal increase in the fractional contribution of octanoate. Both T3 and high substrate provision increased the myocardial energy status, as indexed by phosphocreatine concentration/ATP concentration. In conclusion, T3 supplementation promoted lactate metabolism to the tricarboxylic acid cycle during ECMO, suggesting that T3 releases the inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase. Manipulation of substrate utilization by T3 may be used therapeutically during ECMO to improve the resting energy state and facilitate weaning.

Keywords: cardiac metabolism, extracorporeal circulation, fatty acids, pediatrics, thyroid hormone, citric acid cycle

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is frequently used in infants and children with severe cardiopulmonary failure. In particular, this form of mechanical circulation provides support after injury caused during surgery for congenital heart disease. Approximately 5% of pediatric patients undergoing surgery for congenital heart disease require ECMO, intended as a bridge to recovery (1, 9). Ventricular unloading by ECMO reduces cardiac work and energy requirements and theoretically allows the heart to rest and then reestablish contractile function. Unfortunately, survival rates from ECMO remain low (35–60%) due to numerous complications such as thrombosis, stroke, and, ultimately, failure to wean from the circuit (18). ECMO, similar to cardiopulmonary bypass, induces a massive systemic surge in inflammatory cytokines and disrupts endocrine regulation (16). These effects apparently modify substrate and energy metabolism during ECMO. Our prior studies (8, 16) showed that the immature heart under ECMO maintains some metabolic flexibility by accessing available substrate for oxidation. Without prior injury, the heart on ECMO increases fatty acid (FA) oxidation to accommodate impairments in carbohydrate utilization via the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) pathway. However, another study (14) in immature hearts showed that targeting and increasing flux through PDH improves contractile function.

Flux through PDH can be manipulated by modifying substrate supply. For instance, pyruvate supplementation increases PDH flux and improves contractile function after ischemia-reperfusion (14). However, pyruvate supplementation can be impractical in clinical settings. We and others (11, 13) have also shown that thyroid hormone directly regulates pyruvate flux in the heart. Cardiopulmonary bypass disrupts thyroid hormone homeostasis, rendering the patient severely deficient in circulating triiodothyronine (T3), the active form of this hormone (15). One study (19) has suggested that ECMO causes a similar but more persistent reduction in circulating thyroid levels. A recent large clinical trial showed that T3 repletion for young infants undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass is easily achievable and improves clinical outcome (15). However, the precise mechanism for this action still requires elucidation. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that ECMO-mediated disruption in thyroid hormone homeostasis modifies substrate flux. Furthermore, we determined if T3 supplementation during ECMO targets and increases flux through PDH using a previously validated experimental ECMO model in immature swine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model.

All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of Seattle Children's Research Institute. The surgical preparation followed our previously described methods (8, 14, 16). Twenty-two male Yorkshire pigs (body weight: 10.6–15.6 kg, age: 25–38 days) were divided two groups: 8-h ECMO alone [control (CON) group] and ECMO with intravenous T3 supplementation (TH group). These groups were each further divided into two groups depending on the route of substrate delivery: systemic versus coronary infusion, as previously reported (see below). They were initially sedated with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (33 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg). After intubation through surgical tracheostomy, piglets were mechanically ventilated with an oxygen (40–50%) and isoflurane (1–2%) mixture. An arterial Pco2 of 35–45 mmHg was maintained by adjusting minute ventilation.

After median sternotomy, a flow probe was placed around the ascending aorta to measure cardiac output (TS420, Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). A 5-Fr high-fidelity micromanometer (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was used to measure left ventricular (LV) pressure within the LV body via the apex. To measure coronary venous flow, a cannula with an inflatable balloon cuff was placed into the coronary sinus via the right atrium, and blood was returned to the superior vena cava by a shunt loop. A Transonic flow probe was placed around this shunt for continuous flow monitoring. The hemiazygous vein, which drains systemic venous blood to the coronary sinus in swine, was ligated to avoid systemic contamination of the coronary venous blood. A PowerLab 16/30 recorder (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) continuously recorded data in all cases.

The ECMO circuit consisted of the following: a roller peristaltic pump console (Sarn8000 Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) and a hollow fiber membrane oxygenator (CX-RX05RW, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). The circuit was primed with dextran 40 in 0.9% NaCl, 5% dextrose, and 2,000 units heparin. The total prime volume was 80 ml. A venoarterial ECMO was established by central cannulation via the ascending aorta and right atrium. Management during ECMO kept pump flow rates of 80–100 ml·kg−1·min−1. We maintained a pH of 7.35–7.45, an arterial Pco2 of 35–45 mmHg, and a rectal temperature of 36–37.5°C. The ECMO duration time was 8 h.

Infusion of labeled substrates and thyroid hormone.

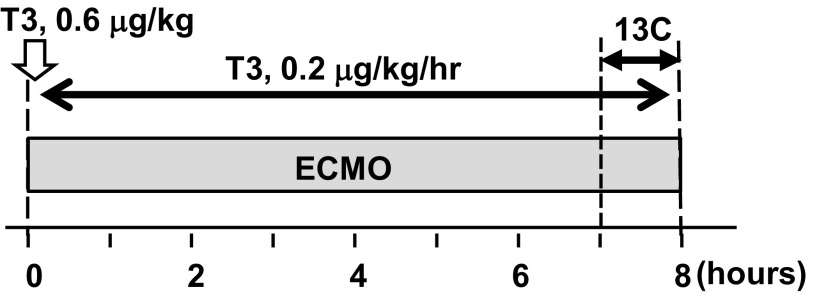

[2-13C]lactate and [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate (medium-chain FA) obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and [U-13C]long-chain mixed FAs (LCFAs) obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA) were used as metabolic markers for all groups. Labeled substrates in all protocols were infused for the final 60 min of the protocol. Two separate substrate delivery methods were used through systemic or intracoronary (IC) infusion. For two groups (CON and TH), [2-13C]lactate, [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate, and [U-13C]LCFAs were delivered into the aortic return cannula for the systemic delivered dose at 2.6, 0.8, and 0.8 μmol·kg body wt−1·min−1, respectively. The rationale for using two different substrate loading protocols has been previously discussed in detail (8). Briefly, IC substrate delivery provides a superior NMR signal from extracted tissue. Accordingly, in two other groups (CON- IC and TH-IC), the stable isotopes were infused directly into the left anterior descending coronary artery via a 24-gauge BD Saf-T-catheter (Becton Dickinson, Sandy, UT) inserted just distal to the origin of the first branch. The IC doses for the CON-IC and TH-IC groups were adjusted to achieve 1.2 mM [2-13C]lactate, 0.4 mM [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate, and 0.4 mM [U-13C]LCFA concentrations in the coronary artery and were based upon the mean LV coronary artery flow per body weight calculated in preliminary immature pig experiments (14). The TH group received an intravenous bolus of T3 (3,3′,5-triiodo-l-thyronine, Sigma) at a dose of 0.6 μg/kg just after the start of ECMO and then a continuous intravenous infusion for 8 h at 0.2 μg·kg−1·h−1 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the experimental protocols. Baseline hemodynamic and plasma data were performed before time 0. The duration of labeled substrate infusion was 60 min. The extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) duration was 8 h. Triiodothyronine (T3) was intravenously given in the T3 supplementation (TH) and intracoronary (IC) infusion-delived TH (TH-IC) groups.

Metabolic analyses by NMR.

The LV apex was freeze clamped at the end of the protocol. Freeze-clamped hearts were ground into fine powder under liquid nitrogen, and 0.5 mg were further homogenized in 2.5 ml of a methanol and double-distilled H2O (1:0.25) mix. A 2:1 chloroform and double-distilled H2O mix was added to the homogenate, vortexed, and placed on ice for 10 min. Samples were next centrifuged for 10 min at 2,000 g for 15 min. The top layer was removed to a fresh tube and subjected to vacuum lyophilization. The resulting precipitate was dissolved in deuterium oxide (DLM11–100, Cambridge Isotopes, Andover, MA) and Chenomx ISTD (DSS) (IS-1, Chenomx) at a 9:1 ratio and filtered through a 0.22-μm syringe filter into NMR sample tubes (WG-1241-8, Wilmad LabGlass, Vineland, NJ). Metabolic analyses by NMR were performed on the swine heart as previously described for the determination of specific carbon glutamate labeling (4, 12). 13C NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian Direct Drive (VNMRS) 600-MHz spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a Dell Precision 390 Linux workstation running VNMRJ 2.2C. The spectrometer system was outfitted with a Varian triple resonance salt-tolerant cold probe with a cold carbon preamplifier. Protons were decoupled with a Waltz decoupling scheme. Final spectra (∼6,000 scans, ∼6 h) were obtained using a 45° excitation pulse (7.05 μs at 58 dB) with an acquisition time of 1.3 s, a recycle delay of 3 s, and a spectral width of 224.1 ppm. Fourier-transformed spectra were fitted with commercial software (NUTS, Acorn NMR, Livermore, CA). All of the labeled carbon resonances (C1–C5) of glutamate, which include multiplets, were integrated using the Lorentzian peak-fitting subroutine in the acquisition program (NUTS). Measured peak areas were analyzed using the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle analysis-fitting algorithm tcaCALC (kindly provided by the Advanced Imaging Research Center at the University of Texas Southwestern) as previously described (8, 16). The glutamate multiplets used for analyses are outlined in the tcaCalc documentation available at http://www4.utsouthwestern.edu/rogersnmr/software/running.html (see Introduction to tcaSIM and tcaCALC). The tcaCALC algorithm requires assumptions as outlined by Malloy et al. (12) (see discussion) and the general methodology reviewed by Des Rosiers and Chatham (3, 4). The predicted initial estimates for the algorithm are available from the authors by request.

Myocardial energy metabolites and amino acid concentrations were measured by 1H NMR spectra from extracted LV tissues as previously described (7, 8, 16, 20). Collected spectra were analyzed using Chenomx software (version 7.1, Chenomx) with quantifications based on spectral intensities relative to 0.5 mM 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate, which was added as a spike to each sample.

Blood analysis.

Arterial and coronary venous blood samples were collected at multiple time points: after anesthesia induction and before ECMO as a baseline, 1, 2, 4, and 7 h after the start of ECMO, and just before the completion of the labeled infusion as an end point. Blood samples were immediately centrifuged, and aliquots of plasma were stored at −80°C. Plasma lactate (BioVision, Mountain View, CA), free FA (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI), and T3 (Endocrine Technology, Newark, CA) concentrations were measured using commercial kits. Blood glucose was measured using a Bayer Contour point-of-care glucometer (Bayer HealthCare, Tarrytown, NY). Blood pH, Pco2, Po2, and hemoglobin were measured at regular intervals by a Radiometer ABL 800 (Radiometer America, Westlake, OH). Myocardial O2 consumption (Mvo2) was calculated from coronary venous flow and blood gas analysis.

Statistical analyses.

Reported values are means ± standard error (SE) in figures, text, and tables. Substrate fractional contribution (FC) data derived from the tcaCALC program were compared and analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U-test. Significant differences from the baseline value for each group in Table 1 and Fig. 2 were estimated by a paired t-test. Other statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons with Tukey's post hoc test. The criterion for significance was P < 0.05 for all comparisons.

Table 1.

Parameters of cardiac function at the beginning and end point for each group

| CON Group |

TH Group |

CON-IC Group |

TH-IC Group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End point | Baseline | End point | Baseline | End point | Baseline | End point | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 9.7 ± 0.4 | 7.2 ± 0.4* | 9.9 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.3* | 9.9 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 1.0* | 9.7 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.8* |

| Heart rate, beats/mn | 96 ± 7 | 108 ± 10 | 96 ± 3 | 118 ± 8 | 99 ± 5 | 134 ± 12 | 105 ± 2 | 125 ± 3 |

| Cardiac output, l/min | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Systolic arterial pressure, mmHg | 78 ± 2 | 55 ± 2* | 80 ± 4 | 60 ± 2* | 77 ± 3 | 60 ± 4* | 77 ± 4 | 57 ± 1* |

| Diastolic arterial pressure, mmHg | 52 ± 2 | 50 ± 2 | 51 ± 1 | 50 ± 2 | 50 ± 3 | 52 ± 3 | 52 ± 3 | 48 ± 2 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 59 ± 3 | 52 ± 2 | 62 ± 2 | 53 ± 2 | 59 ± 2 | 54 ± 3 | 60 ± 3 | 52 ± 2 |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg | 26 ± 2 | 5 ± 1* | 28 ± 3 | 11 ± 2*† | 27 ± 4 | 7 ± 2* | 25 ± 3 | 8 ± 1* |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6 piglets in the control (CON) group, 6 piglets in the thyroid hormone supplementation (TH) group, 5 piglets in the intracoronary (IC) infusion CON group, and 5 piglets in the TH-IC group.

P < 0.05 vs. baseline;

P < 0.05 vs. the CON group.

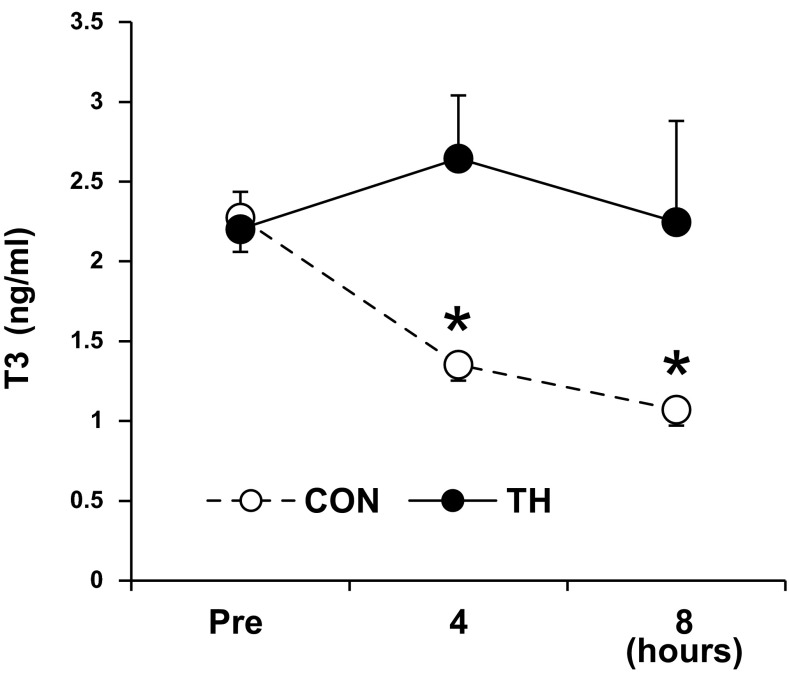

Fig. 2.

Thyroid hormone levels. The plasma T3 level was significantly decreased by ECMO in control (CON) groups (CON and CON-IC group). The T3 level in TH groups (TH and TH-IC groups) was maintained within normal range. n = 11 piglets/group. *P < 0.01 vs. before intervention (Pre; baseline before ECMO).

RESULTS

Plasma thyroid hormone, lactate, and FA levels.

In CON piglets, serum T3 levels decreased by 50% over the ECMO period compared with those of baseline (Fig. 2). Baseline total T3 levels were 2.27 ± 0.22 ng/dl in the CON group and 2.20 ± 0.23 ng/dl in the TH group. After 8-h ECMO, the total T3 level in the CON group significantly decreased to 1.07 ± 0.10 mg/dl, whereas T3 in the TH group maintained near baseline or above throughout the protocol. Systemic infusion of 13C-labeled substrates did not increase nonesterified FA concentrations in plasma levels at 8-h ECMO (0.22 ± 0.02 mM in the CON group vs. 0.26 ± 0.06 mM in the TH group) from the baseline level at pre-ECMO (0.23 ± 0.05 mM in the CON group vs. 0.24 ± 0.03 mM in the TH group). Moreover, the lactate level in plasma at 8-h ECMO was not significantly different between CON (1.35 ± 0.36 mM) and TH (1.20 ± 0.09 mM) group.

Cardiac function and Mvo2 during ECMO.

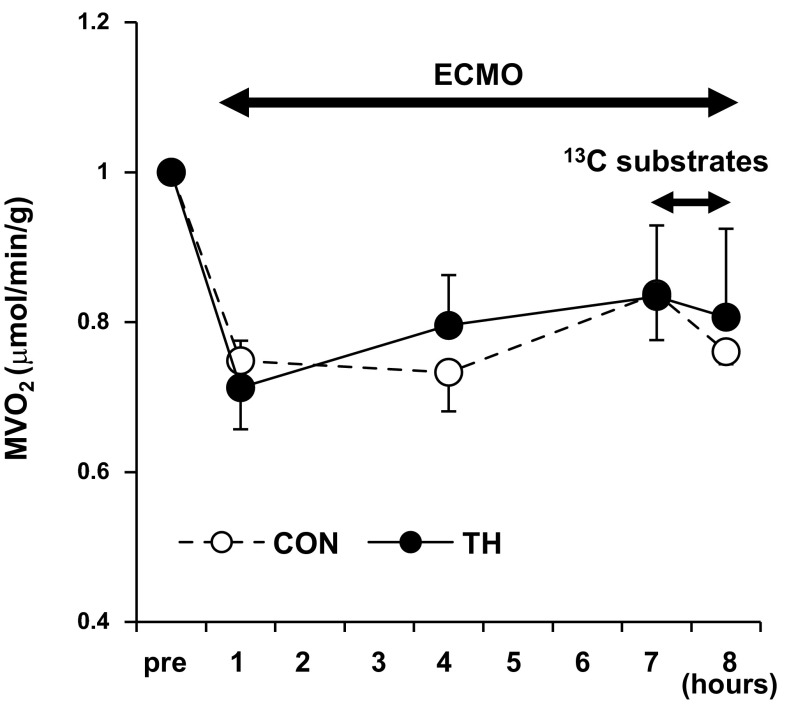

ECMO without blood transfusions maintained hemoglobin within an expected range (9.8 ± 0.2–7.1 ± 0.3 g/dl). Table 1 shows parameters of cardiac function measured at a baseline and an end point in each group. Labeled substrate infusion itself did not affect systemic hemodynamics (data not shown). As expected, ECMO markedly reduced the systemic pulse pressure but maintained mean systemic blood pressure. ECMO reduced Mvo2 ∼25% from the pre-ECMO baseline within 1 h, whereas substrate infusion itself and T3 infusion did not change the calculated Mvo2 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Myocardial O2 consumption (Mvo2) rates during ECMO. Mvo2 was significantly decreased with ventricular unloading by ECMO (P < 0.05). T3 infusion (for 8 h) and 13C-labeled substrate infusion (for final 1 h) itself did not lead to change Mvo2. n = 11 piglets/group.

Metabolism in the immature swine heart on ECMO.

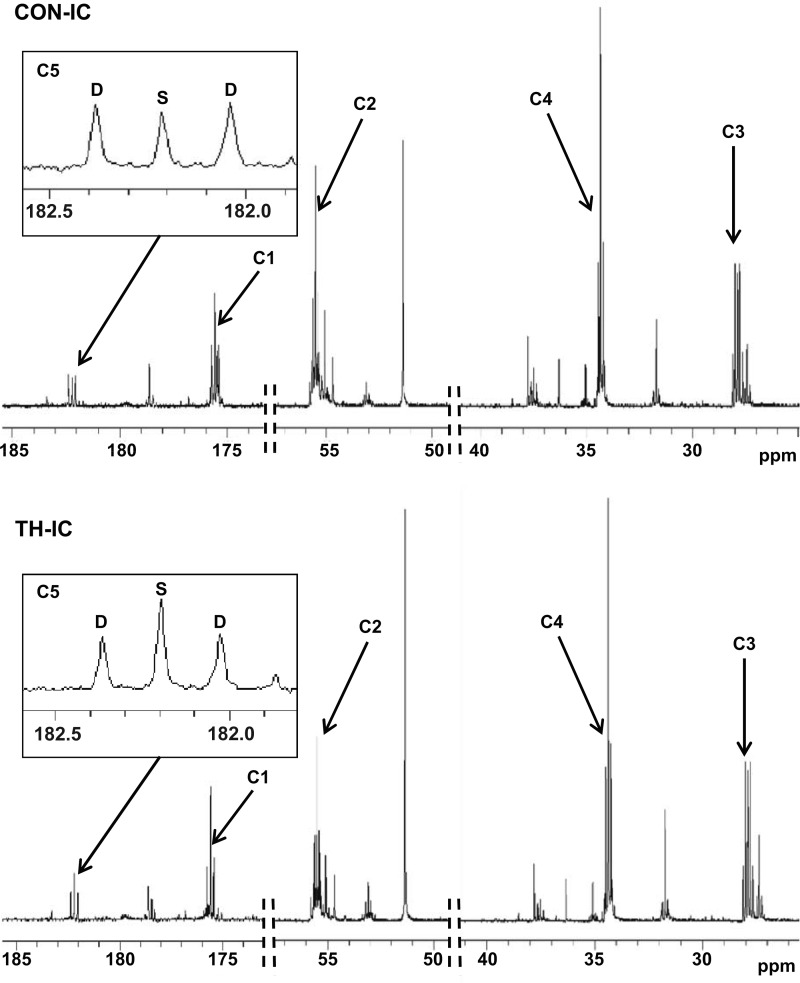

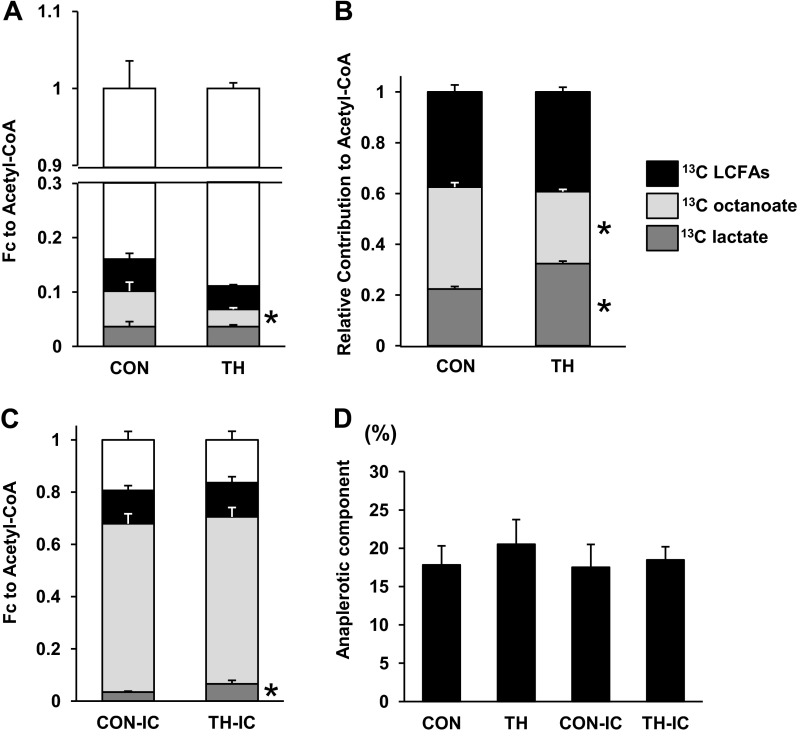

Representative spectra are shown in Fig. 4 with a signal-to-noise ratio ∼ 700:1 for the glutamate C4 singlet. Resonances for all five glutamate carbons are shown and were used in the analyses. Data passed error checking as described by F. Mark Jeffrey in tcaCALC documentation as referenced in materials and methods. This included 1) SE estimates for each parameter provided from the formal covariance matrix of the fit under the assumption of normally distributed errors and 2) estimating the parameter errors through Monte Carlo simulation. 13C NMR data showed the absolute FC for individual labeled substrates and unlabeled substrates. As expected, labeled substrates account for ∼20% of the acetyl-CoA contributed to the TCA cycle (Fig. 5A) with systemic delivery. Under these systemic substrate loading conditions, T3 supplementation decreased the FC of octanoate but did not significantly change any other FC. The relative contribution of 13C-labeled substrates compared with the total labeled fraction is shown in Fig. 5B. These data show that T3 decreased the FC of octanoate and increased the FC of lactate relative to the total contribution from the labeled substrate. Thus, lactate oxidation increases relative to FA oxidation. Direct substrate delivery into the left anterior descending coronary artery markedly decreased the FC from the unlabeled substrate and increased the contribution from isotopically labeled substrates (Fig. 5C). The TH-IC group showed an approximately twofold greater FC of lactate than observed in the CON-IC group (3.4 ± 0.3% vs. 6.5 ± 1.4%, P < 0.05). Under these IC substrate delivery conditions, FA oxidation made up a large proportion of FC (octanoate: 64.5 ± 0.4% and LCFAs: 12.7 ± 0.2%), thereby masking any FC shifts caused by T3. Anaplerotic contribution relative to total TCA cycle flux ranged between 15% and 20% and did not vary significantly among the four groups (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 4.

Typical 13C NMR spectra obtained from left ventricular extracts after a 60-min infusion of [2-13C]lactate, [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate, and [U-13C]long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) into the left anterior descending coronary artery. Spectra showed adequate signal-to-noise ratios for peak integration. Chemical shifts were as follows: C1, 175.5 ppm; C2, 55.2 ppm; C3, 27.7 ppm; C4, 34.2 ppm; and C5 of glutamate, 182.2 ppm. Marked differences occurred in glutamate peak complexes between the two conditions. For instance, glutamate C5 (insets) in the TH-IC group showed an increased singlet peak area (S) compared with the CON-IC group, indicating increased lactate oxidation with T3 supplementation. D, doublet peak area.

Fig. 5.

Substrate contribution to acetyl-CoA under near-physiological conditions (A and B), with high fatty acid infusion (C), and the anaplerotic component (D) by 13C NMR. A: fractional substrate contribution (FC) to acetyl-CoA with systemic infusion of labeled substrates and unlabeled substrates. B: contribution from labeled substrates only (as shown in A) during systemic infusion. [2-13C]lactate increased, whereas [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate decreased, with systemic labeled substrate infusion relative to each other. C: compared with CON-IC, the FC of [2-13C]lactate markedly increased in the TH-IC group. D: anaplerotic component relative to the tricarboxylic acid cycle flux was similar among the four groups. The FCs of [U-13C]LFCAs, [2,4,6,8-13C4]octanoate, and [2-13C]lactate are shown. n = 5–6 piglets/group. *P < 0.05 vs. CON or CON-IC groups. Error bars relate to individual FCs.

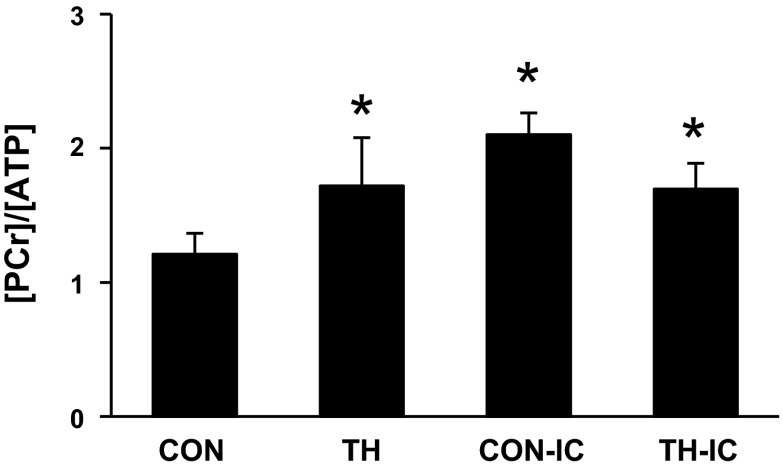

Under systemic substrate loading conditions, the tissue phosphocreatine (PCr) concentration-to-ATP concentration ratio ([PCr]/[ATP]) was elevated in the TH group compared with the CON group (Fig. 6). IC infusion with high-dose substrate also elevated [PCr]/[ATP] and obviated the TH effect. We also noted protocol-mediated shifts in amino acid concentrations. In particular, the TH groups showed substantially lower levels for branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs; leucine, isoleucine, and valine) than in comparable CON groups, although this affect was ameliorated and not significant with IC substrate infusion. IC infusion with the very high FC for LCFAs and octanoate increased glutamine and decreased glutamate and aspartate (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Energy metabolite ratios by 1H NMR spectra from left ventricular tissues at the end of the protocol. The tissue phosphocreatine concentration-to-ATP concentration ratio ([PCr]/[ATP])was significantly increased in the TH, CON-IC, and TH-IC groups compared with the CON group. n = 5–6 piglets/group. *P < 0.05 vs. the CON group.

Table 2.

Amino acid concentrations in myocardial tissues by 1H NMR

| CON Group | TH Group | CON-IC Group | TH-IC Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | 3.55 ± 0.19 | 3.22 ± 0.43 | 4.15 ± 1.19 | 3.68 ± 0.45 |

| Aspartate | 1.12 ± 0.01 | 0.76 ± 0.16 | 0.32 ± 0.10* | 0.41 ± 0.5 |

| Glutamate | 5.14 ± 0.41 | 4.16 ± 0.26 | 2.16 ± 0.24* | 1.89 ± 0.05† |

| Glutamine | 11.01 ± 2.01 | 9.57 ± 0.59 | 12.98 ± 2.82 | 14.42 ± 1.64† |

| Glutamate/glutamine | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.20 ± 0.05* | 0.18 ± 0.03† |

| Branched-chain amino acids | ||||

| Leucine | 289 ± 23 | 176 ± 17† | 305 ± 96 | 229 ± 30 |

| Isoleucine | 211 ± 28 | 121 ± 15* | 210 ± 61 | 160 ± 29 |

| Valine | 402 ± 51 | 261 ± 21* | 424 ± 126 | 295 ± 41 |

Values (in mM) are means ± SE; n = 5–6 piglets/group.

P < 0.01 vs. the CON group;

P < 0.01 vs. the TH group.

DISCUSSION

Our prior work (7, 8, 16) has shown that pyruvate decarboxylation plays an important role in providing energy for contractile function in the immature heart. Those prior studies, using the same experimental model as used in the present investigation, showed that the inflammatory response caused by several hours of ECMO modestly reduces metabolic flexibility and impairs flux through PDH. Those studies also demonstrated that ECMO markedly increases the acetyl-CoA contribution to the TCA cycle from FAs relative to pyruvate (7). In the present study, we sought to determine if metabolic targeting by thyroid hormone could alter substrate utilization and reverse these trends caused by ECMO. We found that the shift in substrate preference induced by ECMO directly relates to depletion in circulating T3. Repletion of T3 restored PDH flux despite the robust availability of both LCFAs and medium-chain FAs, which would promote FA oxidation over carbohydrate oxidation. Under systemic infusion conditions, the restored PDH flux elevated [PCr]/[ATP], which is generally considered an surrogate for phosphorylation potential and oxidative capacity. These changes in PDH flux and high-energy phosphates occurred without increasing Mvo2 and are consistent with the tenet that carbohydrate metabolism is more oxygen efficient than FA oxidation. This improvement in oxygen efficiency poses no advantage in the present scenario in which the oxygen supply is abundant but may be important to the heart exposed to continuing perfusion abnormalities or deficits in the postoperative period. Thus, T3 repletion in this setting represents a powerful strategy for metabolic manipulation, which has been previously been shown as effective for restoring contractile function after substantial myocardial injury (13). Although we did not explore the precise molecular mechanism for thyroid hormone action, other investigators have shown that T3 directly activates PDH through nongenomic signaling (11).

In the present study, we examined PDH flux using lactate as the primary carbohydrate substrate. Lactate and FAs were supplied in either physiological or highly elevated doses but with similarly distributed coronary artery concentrations in separate experiments. These experiments showed that PDH flux relative to total free FA flux did not change according to substrate concentration. However, we (13) have previously shown that changes in pyruvate decarboxylation were accompanied by proportional changes in pyruvate anaplerotic contribution via pyruvate carboxylase or malic enzyme. Our tcaCALC-based analyses of the present data revealed that modifications in the FC of lactate induced by thyroid hormone were not accompanied by comparable increases in total anaplerotic contribution to the TCA cycle. This finding suggests that lactate does not directly stimulate total anaplerosis in this experimental model. However, we did not design this study to directly interrogate individual anaplerotic pathways, such as pyruvate carboxylation, and flux through multiple other anaplerotic pathways could influence these results in multiple ways.

We also identified T3 modulation of myocardial concentrations for BCAAs using 1H NMR. They are essential amino acids and can be used as an oxidative fuel by the heart (5). These BCAAs undergo oxidation via branched-chain aminotransferase and, subsequently, branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes and ultimately yield a modest relative acetyl-CoA contribution to the TCA cycle in the heart (6). Previously, we (16) have shown that ECMO preserves the FC of leucine, whereas the total leucine oxidative flux changes in direct proportion to O2 consumption. However, substrate availability or composition can influence leucine uptake by the heart. In particular, pyruvate, when present at high concentrations in the extracellular environment, reduces myocardial leucine uptake and inhibits its oxidation. Our BCAA concentration data suggest that T3 regulates their cellular transport, oxidation, or incorporation into protein. Additional experiments using labeled leucine would be required to determine thyroid hormone regulation of BCAA oxidation.

As a secondary finding, we identified modifications in substrate oxidation and the amino acid profile by dramatically increasing free FA concentrations in the coronary artery to levels well above those attainable in a clinical scenario. We performed direct stable isotope delivery into the coronary artery to increase 13C myocardial enrichment and improve both signal to noise and resolution in the NMR signal. As noted, high-dose stable isotope infusion did not alter relative acetyl-CoA contributions within the labeled fraction in piglets with and without T3 supplementation. However, infusion into the coronary artery dramatically increased the labeled substrate contribution with an overwhelming portion by medium-chain FAs. Similar to results from multiple other studies (2, 17), the enhanced FA contribution increased [PCr]/[ATP]. The increase in FA oxidation also obviated changes in these parameters caused by T3 in the lower-dose group. This latter observation suggests that the affects of modifying substrate supply to the heart supersedes the influence of T3 repletion on PDH under these ECMO conditions. However, raising these IC substrate concentrations clinically is impractical compared with providing thyroid hormone supplementation.

In prior work, we noted that ventricular reloading from ECMO caused shifts in the amino acid pool favoring glutamine over glutamate, which we presumed were related to increased FA oxidation (7). The present results confirm that this amino acid shift coincides with an increase in FA oxidation. The significance of this relationship in the heart in vivo remains unclear. Lauzier et al. (10) showed that glutamine supplied at physiological levels to isolated perfused hearts does not substantially participate in anaplerosis to glutamate but does stimulate FA oxidation. These amino acids, as well as aspartate, which is also affected by increasing substrate concentration, participate in the shuttling of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide into the mitochondria, which may also be altered under conditions of extremely high fat provision.

Limitations and assumptions.

This study demonstrated changes in relative contributions from labeled substrates during metabolic perturbation by thyroid hormone during ECMO. As expected in a study performed in vivo, there was a considerable contribution from unlabeled substrates. These unlabeled substrates could include circulating carbon sources as well as heart endogenous substrates, such as triglycerides and glycogen. Our inability to specifically identify these sources after the systemic delivery of labeled substrates does represent a limitation. However, we did achieve >80% glutamate fractional 13C enrichment during the IC infusion of labeled substrates. This reduces the impact of the unlabeled component, as the relationship among the labeled substrates is similar between the two infusion protocols: thyroid hormone increases lactate oxidation relative to FAs. Additionally, our estimations of FC depend on modeling algorithms developed by Malloy et al. and incorporated into the tcaCALC program (12). These algorithms depend on the following assumptions about carbon flow into the TCA cycle: 1) carbon flows into the TCA cycle either through acetyl-CoA or anaplerotic pathways, 2) experiments are performed under steady state and the concentrations and fractional enrichment of the TCA cycle intermediates and exchanging pools are therefore constant, 3) all 13C directed into oxaloacetate is randomized between C1 and C4 and between C2 and C3, and 4) flux through the combined anaplerotic reactions equals the flux through TCA cycle intermediate disposal reactions. Theoretically, labeled carbons on octanoate or free FAs delivered via the systemic infusion protocol could enter the hepatic TCA cycle and exit the liver as an alternately labeled substrate. This relabeled substrate could affect the labeling distribution for acetyl-CoA in the heart. However, considering that the substrate delivery in these experiments occurs through the central aorta and recycling back to the heart would require several passes through the circulation, we believe such a contribution would be neglible. This contention is supported by the data that showed relative contributions from labeled substrate between the two protocols.

Conclusions.

In a scenario emulating infant ECMO, T3 repletion modifies metabolic flux and shifts substrate oxidation toward PDH. This shift is high-energy phosphate sparing at no additional oxygen cost. Thus, PDH represents a reasonable metabolic therapeutic target. Results from the present and previous studies suggest that T3 targeting of metabolism can serve in part as the operative mechanism for this benefit.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-60666 (to M. A. Portman). A portion of the research was performed using EMSL, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the Department of Energy's Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.K., A.K.O., and M.A.P. conception and design of research; M.K., C.M.O.P., D.L., C.X., and N.I. performed experiments; M.K., D.L., N.I., and M.A.P. analyzed data; M.K., C.M.O.P., D.L., C.X., N.I., A.K.O., and M.A.P. interpreted results of experiments; M.K. and M.A.P. prepared figures; M.K. and M.A.P. drafted manuscript; M.K. and M.A.P. edited and revised manuscript; M.K., C.M.O.P., D.L., C.X., N.I., A.K.O., and M.A.P. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal HS, Hardison DC, Saville BR, Donahue BS, Lamb FS, Bichell DP, Harris ZL. Residual lesions in postoperative pediatric cardiac surgery patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 147: 434–441, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthiaume JM, Bray MS, McElfresh TA, Chen X, Azam S, Young ME, Hoit BD, Chandler MP. The myocardial contractile response to physiological stress improves with high saturated fat feeding in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H410–H421, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatham JC, Bouchard B, Des Rosiers C. A comparison between NMR and GCMS 13C-isotopomer analysis in cardiac metabolism. Mol Cell Biochem 249: 105–112, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Des Rosiers C, Lloyd S, Comte B, Chatham JC. A critical perspective of the use of 13C-isotopomer analysis by GCMS and NMR as applied to cardiac metabolism. Metab Eng 6: 44–58, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake KJ, Sidorov VY, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH, Wikswo JP. Amino acids as metabolic substrates during cardiac ischemia. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 237: 1369–1378, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris RA, Joshi M, Jeoung NH, Obayashi M. Overview of the molecular and biochemical basis of branched-chain amino acid catabolism. J Nutr 135: 1527S-1530S, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kajimoto M, O'Kelly Priddy CM, Ledee DR, Xu C, Isern N, Olson AK, Des Rosiers C, Portman MA. Myocardial reloading after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation alters substrate metabolism while promoting protein synthesis. J Am Heart Assoc 2: e000106, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kajimoto M, O'Kelly Priddy CM, Ledee DR, Xu C, Isern N, Olson AK, Portman MA. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation promotes long chain fatty acid oxidation in the immature swine heart in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol 62: 144–152, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar TK, Zurakowski D, Dalton H, Talwar S, Allard-Picou A, Duebener LF, Sinha P, Moulick A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in postcardiotomy patients: factors influencing outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 140: 330–336 e332, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauzier B, Vaillant F, Merlen C, Gelinas R, Bouchard B, Rivard ME, Labarthe F, Dolinsky VW, Dyck JR, Allen BG, Chatham JC, Des Rosiers C. Metabolic effects of glutamine on the heart: anaplerosis versus the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol 55: 92–100, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Q, Clanachan AS, Lopaschuk GD. Acute effects of triiodothyronine on glucose and fatty acid metabolism during reperfusion of ischemic rat hearts. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E392–E399, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM. Analysis of tricarboxylic acid cycle of the heart using 13C isotope isomers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H987–H995, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olson AK, Bouchard B, Ning XH, Isern N, Rosiers CD, Portman MA. Triiodothyronine increases myocardial function and pyruvate entry into the citric acid cycle after reperfusion in a model of infant cardiopulmonary bypass. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H1086–H1093, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson AK, Hyyti OM, Cohen GA, Ning XH, Sadilek M, Isern N, Portman MA. Superior cardiac function via anaplerotic pyruvate in the immature swine heart after cardiopulmonary bypass and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2315–H2320, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Portman MA, Slee A, Olson AK, Cohen G, Karl T, Tong E, Hastings L, Patel H, Reinhartz O, Mott AR, Mainwaring R, Linam J, Danzi S. Triiodothyronine Supplementation in Infants and Children Undergoing Cardiopulmonary Bypass (TRICC): a multicenter placebo-controlled randomized trial: age analysis. Circulation 122: S224–233, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priddy CM, Kajimoto M, Ledee DR, Bouchard B, Isern N, Olson AK, Des Rosiers C, Portman MA. Myocardial oxidative metabolism and protein synthesis during mechanical circulatory support by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H406–H414, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rennison JH, McElfresh TA, Okere IC, Patel HV, Foster AB, Patel KK, Stoll MS, Minkler PE, Fujioka H, Hoit BD, Young ME, Hoppel CL, Chandler MP. Enhanced acyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity is associated with improved mitochondrial and contractile function in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 79: 331–340, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvin JW, Laussen PC, Thiagarajan RR. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for postcardiotomy mechanical cardiovascular support in children with congenital heart disease. Paediatr Anaesth 18: 1157–1162, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart DL, Ssemakula N, MacMillan DR, Goldsmith LJ, Cook LN. Thyroid function in neonates with severe respiratory failure on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfusion 16: 469–475, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weljie AM, Newton J, Mercier P, Carlson E, Slupsky CM. Targeted profiling: quantitative analysis of 1H NMR metabolomics data. Anal Chem 78: 4430–4442, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]