Abstract

Intermittent claudication is a form of exercise intolerance characterized by muscle pain during walking in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD). Endothelial cell and muscle dysfunction are thought to be important contributors to the etiology of this disease, but a lack of preclinical models that incorporate these elements and measure exercise performance as a primary end point has slowed progress in finding new treatment options for these patients. We sought to develop an animal model of peripheral vascular insufficiency in which microvascular dysfunction and exercise intolerance were defining features. We further set out to determine if pharmacological activation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) might counteract any of these functional deficits. Mice aged on a high-fat diet demonstrate many functional and molecular characteristics of PAD, including the sequential development of peripheral vascular insufficiency, increased muscle fatigability, and progressive exercise intolerance. These changes occur gradually and are associated with alterations in nitric oxide bioavailability. Treatment of animals with an AMPK activator, R118, increased voluntary wheel running activity, decreased muscle fatigability, and prevented the progressive decrease in treadmill exercise capacity. These functional performance benefits were accompanied by improved mitochondrial function, the normalization of perfusion in exercising muscle, increased nitric oxide bioavailability, and decreased circulating levels of the endogenous endothelial nitric oxide synthase inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine. These data suggest that aged, obese mice represent a novel model for studying exercise intolerance associated with peripheral vascular insufficiency, and pharmacological activation of AMPK may be a suitable treatment for intermittent claudication associated with PAD.

Keywords: obesity, intermittent claudication, nitric oxide, exercise, 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase

peripheral artery disease (PAD) is estimated to be present in 8–10 million Americans and is especially prevalent in older individuals, occurring in nearly 5% of all persons over the age of 50 yr (10, 24, 40). PAD significantly impacts both the mortality and morbidity of affected patients, and substantial medical resources are directed toward treating its various complications. For example, there are roughly 260,000 revascularizations performed each year and 100,000 amputations, and nearly 4 million people with stable disease suffer from intermittent claudication, which is characterized by painful muscle cramps during walking that severely limit activity (16, 63). Although occlusive, extracoronary atherosclerosis in large vessels servicing the lower limbs, such as the iliac, femoral, popliteal, or tibial arteries, is one of the defining diagnostic features of PAD, tissue dysfunction at sites distal to the atherosclerotic stenosis is believed to play a prominent role in the development of claudication. For example, surgical correction of the primary flow deficit at the site of stenosis generally fails to fully reset functional performance (19, 53). Conversely, exercise training can delay the time until claudication during walking without fundamentally altering the status of upstream atherosclerotic lesions (49, 54). Thus, intermittent claudication is multifactorial, and approaches that only focus on alleviating large vessel stenosis, such as revascularization, may be insufficient in the context of downstream muscle and/or microvascular dysfunction. These observations have highlighted the potential role of endothelial and muscle dysfunction in the development of intermittent claudication (22, 31, 71) and have expanded the opportunities for developing therapeutic treatments directed toward skeletal muscle and vascular endothelial cells (ECs).

Numerous links exist between the biological mechanisms influenced by 5′-AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) and those known to be dysfunctional in PAD, suggesting that therapeutic modulation of this master regulatory protein might be beneficial in treating certain aspects of this disease, including the improvement of mitochondrial and endothelial function in skeletal muscle (71, 76). For example, exercise training can improve walking distance in patients with claudication (54, 65), and one of AMPK's most important roles is to coordinate the acute and chronic adaptation of tissues in response to exercise, including the stimulation of local angiogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis within skeletal muscle (22). 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR), which is an AMP analog and can activate AMPK, leads to increases in skeletal muscle oxidative enzyme activities in rodents indicative of mitochondrial biogenesis and/or improved efficiency (17, 70). In patients with PAD, skeletal muscle displays many characteristics of poor mitochondrial function, such as acylcarnitine accumulation, impaired electron transport chain activity, and delayed O2 utilization at the onset of exercise (7, 52). Similarly, AMPK can directly influence vascular tone through the activation of endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) within ECs (8, 71, 74, 76), reverse age-impaired endothelium-dependent vascular dysfunction (32), and increase skeletal muscle perfusion (6). Interestingly, NO bioavailability and subsequent endothelial function are compromised in patients with PAD (26, 69).

Currently, the most common preclinical approach for studying PAD is based on surgical ligation of the femoral artery in rodents. Although this model successfully creates ischemic conditions in the lower limbs, it falls short on several fronts (14, 75). First, this method is most often conducted in healthy, young animals, whereas PAD typically develops in older individuals with a history of smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, metabolic derangement, obesity, and physical inactivity. Second, the initial drops in muscle blood flow after surgical ligation are severe and rapid, as opposed to the gradual loss of limb perfusion in humans with PAD. Third, rodents are exceptional at responding to surgical ligation with aggressive arteriogenesis and angiogenesis, thereby limiting the opportunity for chronic muscle dysfunction to develop and confounding attempts to conduct long-term longitudinal studies with in-depth functional assessments, including exercise performance. In studies where age and comorbidities have been factored into the research design, the primary end point has been perfusion of the feet, and exercise performance has not been considered (15, 33). Coincidentally, clinical trials aimed at reducing claudication use the 6-min walk test as the primary end point, and drugs that have improved the recovery of perfusion in the feet have not succeeded in delaying the time until claudication in clinical trials (75).

The disconnect between the recovery of perfusion after ligation in rodents and exercise performance in humans prompted us to explore alternative model systems more closely aligned with PAD in terms of evolution of the disease, metabolism, pathological sequence, comorbidities, and functional exercise deficits. In this regard, it is known that C57BL/6 mice with dietary-induced obesity (DIO) display many of the risk factors associated with the development of PAD, including type II diabetes and dyslipidemia (60, 66). Furthermore, there is limited evidence for the development of atherosclerosis (47), poor exercise performance (30), microvascular and endothelial dysfunction (11, 43), and impaired vasodilation of conduit arteries ex vivo in rodents (5). Therefore, we characterized aged, DIO mice in terms of exercise capacity and skeletal muscle perfusion as a potential model of peripheral vascular insufficiency. We hypothesized that a novel, small-molecule AMPK activator, R118, would improve exercise capacity and skeletal muscle perfusion in this model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 and apolipoprotein E gene (ApoE)-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were males except for the comparison of C57BL/6 and ApoE−/− mice. Mice were provided food and water ad libitum and housed in a room with a 12:12-h reverse light cycle (lights on from 7:00 PM to 7:00 AM). All mice were housed at 4 mice/cage for the duration of the study with the exception that the wheel-trained mice were singly housed. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rigel Pharmaceuticals approved all procedures.

Dietary treatments.

Mice were fed either standard rodent chow [normal diet (ND); no. 5001, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO] or a high-fat diet (HFD) consisting of 60% of kcal from fat (no. D12492, Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ). The HFD was commenced at 6 wk of age. For the initial comparison of ND (n = 18) and HFD (n = 36), mice were tested monthly for exercise capacity and muscle perfusion from 9 to 46 wk of HFD. A larger, second study was conducted using 53-wk-old mice fed either the ND (n = 34) or HFD (n = 36). Exercise-trained mice fed a HFD were used as positive controls, and they were individually housed with activity wheels (n = 18). Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase 3A inhibitor that improves vasodilation (58) and was used as an active control drug that is currently approved for treatment of claudication. Two doses of cilostazol (Ontario Chemicals) were used: 550 mg/kg HFD (n = 36) and 733 mg/kg HFD (n = 18). These doses corresponded to 30 and 40 mg/kg body mass (48). AT-1015 is serotonin (5-HT)2A receptor antagonist that inhibits platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction (28) that was previously developed for the treatment of claudication. This drug failed to improve walking time in clinical trials and was associated with antimuscarinic activities and a dose-dependent decrease in tolerability, so this drug served as a negative control for the exercise tests (23). Mice were dosed with AT-1015 (Tocris Bioscience) at 55 mg/kg HFD (n = 18), and this was equivalent to 3 mg/kg body mass. R118 (21), an AMPK activator, was dosed at 244 mg/kg HFD (n = 35) and 366 mg/kg HFD (n = 36), and this was equivalent to 13 and 20 mg/kg body mass, respectively. These doses were chosen to match the exposures [24-h area under the curve (AUC24 h)] needed for maximum AMPK activation in skeletal muscle (see Fig. 6). All medicated diets were made at Research Diets and were fed to the mice for the entire duration of the study. The dosages for AT-1015 and cilostazol were chosen to match plasma exposures (AUC24 h) based on previous studies (29, 58). Sample sizes were determined based on power analyses needed to detect differences in treadmill running from previous experiments. Animals were not randomly assigned to treatment groups but were instead sorted to equally distribute mice based on their pretreatment treadmill run time, voluntary wheel running time, and body mass.

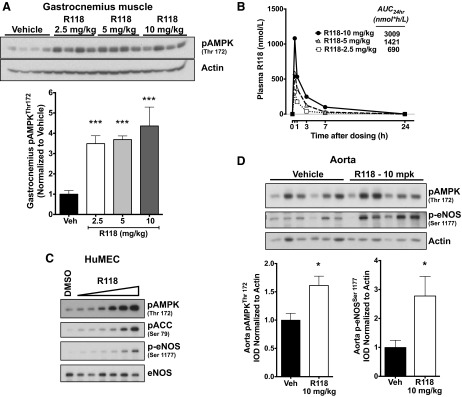

Fig. 6.

R118 activates AMPK and endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) in vitro and in vivo. A: representative Western blot showing phosphorylated (p)AMPK (Thr172) activation in gastrocnemius muscle 60 min after oral dosing of R118 at 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg body mass (n = 4 mice/group) in 11.5-wk-old C57BL/6 wild-type mice and quantitation of pAMPK (Thr172). B: plasma levels of R118 after acute dosing. Sample sizes at each time point were as follows: n = 4 mice/group except 7 h (n = 3) and 24 h (n = 2). C: human microvascular endothelial cells (HuMECs) were treated with DMSO or R118 at increasing concentrations (9, 27, 82, 244, 733, and 2,220 nM) for 10 min. The triangle represents the increasing concentration of R118. This experiment was replicated two times. D: R118 activates eNOS in the aorta in vivo. Male C57BL/6 mice fed a HFD for 47 wk were dosed orally with R118 or vehicle at 10 mg/kg body mass, and aortas were collected 60 min after dosing (n = 6 mice/group). Western blots of phosphorylation of AMPK (Thr172) and eNOS (Ser1177) are shown with a quantification of pAMPK (Thr172) and p-eNOS (Ser1177). IOD, integrated optical density. Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed with two-tailed, independent t-tests or one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak's post hoc test. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle (Veh).

Oral glucose tolerance test.

ND (n = 34)-fed or HFD (n = 33)-fed mice were tested for glucose tolerance at 58 wk of age and after 52 wk of HFD. Mice were fasted for 6 h followed by a tail nick, and 1 drop of blood was analyzed for glucose using a glucometer (Breeze2, Bayer). A bolus of glucose was delivered via oral gavage at 2 g/kg body mass, and glucose was measured at 15, 30, 60, and 90 min after the glucose bolus. No anesthesia was used for blood collection.

Voluntary wheel running test.

The rationale behind this test was to determine voluntary physical activity similar to a 6-min walk test in humans. Mice were removed from their home cages and placed individually in cages equipped with wireless activity wheels (ENV-044, Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT). Ventilated racks containing a total of 160 cages with wheels were set up in the same reverse light cycle room as the mice were housed to facilitate high-throughput voluntary exercise testing. Mice were run in two shifts at ∼9 and 11 AM each day during the active dark cycle, and treatment groups were equally split across the different time slots. The amount of activity was recorded for 60 min, but each mouse was allowed to run for ∼75–80 min to facilitate the transfer of mice back to their home cages. Only 60 min of activity was recorded instead of 24-h access to prevent positive exercise training adaptations and to mimic the short, timed nature of the 6-min walk test. Mice had ad libitum access to water but not to food. Wheel-trained mice also took part in the test, but their home wheels were locked for ∼18 h to prevent exercise before the test. Mice were given 3 consecutive days for each test, and the activity across the 3 days was averaged to account for any acclimation effects. Wheel Manager software (Med-Associates) was used to collect activity wheel count data in 1-min bins. Rest time was also computed and was defined as the period of time (in 1-min intervals) where “0” counts/revolutions were recorded. Average speed was calculated only for the 1-min intervals where activity counts were >0. Preliminary data in a separate group of mice demonstrated good correlations between the first and second days of the test (n = 48, r = 0.636, P < 0.001) and second and third days of the test (r = 0.875, P < 0.001) as well as voluntary wheel running total counts and forced treadmill exercise time (n = 45, r = 0.400, P = 0.007).

Treadmill exercise test.

Mice were acclimated a total of three times (once daily) before each treadmill test using a progressive protocol in which the belt speed increased from 6 to 10 m/min over the course of 5 min. Before treadmill testing, mice were fasted for 1 h with ad libitum access to water. Treadmill tests were carried out on a Columbus Instruments 1055MSD Exer-6M Open Treadmill for mice custom modified so that the stimulation grid rested 3 cm below the plane of the top of the treadmill belt and the end of each stimulation loop terminated 0.5 cm from the treadmill belt roller. These custom modifications were important for minimizing cheating behavior in which mice learn to sit on the stimulation grid, insulated by their fur, with their legs extending downward. Treadmills were set to a 5° incline and confirmed using a clinometer. Treadmill speeds were controlled electronically using vendor-supplied software and calibrated using a bicycle speedometer mounted on each treadmill. Treadmill tests used a progressive speed increase from 6 to 18 m/min, accelerated at 1 m/min2, and remained at 18 m/min until fatigue was determined or after 2.5 h of running. Mice were encouraged to run by a mild electric shock (3 Hz, intensity: 3). Treadmills were located in the same reverse light cycle room as the mice were housed, and all tests were conducted in the dark during two possible time slots per day with start times at 10 AM or 1 PM during the active dark phase. Groups were balanced across treadmills and time slots. Data were captured in video format using FLIR A300 series thermal video cameras mounted above every two treadmills. Real-time tracking and XY positional data were accomplished using Noldus EthovisionXT 8.0 software. Real-time tracking and scoring of mice was used to determine when a mouse had reached exhaustion according to the parameters described below. Mice meeting the exhaustion criteria had their stimulation grids turned off and were left in place until the end of the test period.

Treadmill data analysis and calculation of exhaustion points.

A single exhaustion episode was defined when a mouse spent at least 45 s in the span of any 60-s segment occupying a zone (referred to as the exhaustion zone) that extended from the rear of the stimulation grid to one full body length up the length of the treadmill belt. Tabulated time in the exhaustion zone did not start until after the rear legs of the mouse touched the grid area. Timing ended as soon as the mouse advanced far enough up the treadmill belt such that the base of the tail surpassed one full body length from the end of the treadmill belt. The cumulative time in the exhaustion zone after a grid visit is referred to as anchored time. Nonexhausted mice rarely occupied any portion of this zone area. The typical time spent in the exhaustion zone after a grid visit (anchored time) by nonexhausted mice averaged just 0.1 s. Thus, 45 of 60 s in the exhaustion zone indicates a profound inability to escape the stimulation grid or the area immediately adjacent to it. Exhaustion was defined as occurring after two exhaustion episodes were observed. All figures were constructed using exhaustion time points to calculate treadmill run times. Data were quality controlled by rechecking all zone boundaries for accurate placement and scale, adjusting video contrast, rerunning XY position determination on saved video files, and manually forwarding through tracked video to make sure no physical shifts in the treadmill position occurred during the test. Calculating anchored time, exhaustion episodes, and full exhaustion for each mouse was accomplished by importing raw XY position and time data into a customized analysis program. Figure graphs were generated using Prism 6.0 (Graphpad). Data were used from all animals unless the grid was turned off prematurely or only one exhaustion point was found.

In vivo plantar flexion muscle contractions.

Contractions of the plantar flexor muscles (gastrocnemius, plantaris, and soleus muscles) were performed in a similar fashion as previously described (39). Mice were anesthetized with 1.5–2% isoflurane, the left hindlimb was shaved, and hair was further removed with depilatory cream. The animal was placed on its right side on a platform heated to 38°C. The left foot was taped to a footplate attached to a servomotor (model 305C, Aurora Scientific, Aurora, ON, Canada). Percutaneous electrodes were used to stimulate the sciatic nerve with a stimulator (model 701C, Aurora Scientific). Muscle contractions were elicited at a contraction frequency of 100 Hz, 0.15-ms square-wave pulses, and a train duration of 200 ms. The stimulator and dual-mode lever system (model 305C, Aurora Scientific) were interfaced with a PowerLab system (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) to control the stimulator and acquire data from the force transducer using LabChart software (AD Instruments). Maximal isometric torque was determined by increasing the stimulator voltage 0.2 V/min until maximum torque was reached. Muscle fatigue was measured by eliciting 1 contraction every 2 s for a total of 60 contractions. The amount of force at every contraction relative to the first contraction was used to assess the amount of fatigue.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5–2%, 500 ml O2/min), and a 27-gauge catheter was placed into each mouse's tail and kept in place with surgical glue. Each mouse was placed in a supine position on a platform heated to 38°C with each paw taped to a surface electrode to monitor ECG, heart rate, and respiratory rate. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (Vevo 2100, Visualsonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) was performed at an imaging frequency of 18 MHz. The probe was placed on the medial side of the leg to image the lower hindlimb in a sagittal plane. A bolus injection of microbubbles (Vevo MicroMarker, Bracco, Geneva, Switzerland) were injected through the tail vein catheter according to the manufacturer's instructions. A syringe pump delivered the bolus of 50 μl at an infusion rate of 17.33 μl/s. A cine loop was recorded at a frame rate of 20 frames/s for a total of 1,000 frames. Curve fit analysis was used to measure echo power over time. The difference in maximum and minimum video intensity was determined as the peak enhancement and was the variable used to determine muscle perfusion. Only samples with a quality fit of 90% or greater were used in the analysis.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound before and after muscle contractions was performed similarly except for the following modifications. Each mouse was placed in a lateral position on its right side to facilitate placement of the left foot into the footplate of the servomotor. The probe was placed on the lateral side of the leg, but the leg was still imaged in a sagittal plane. Each mouse was imaged before muscle contractions with a 20-min washout period of the microbubbles before the second cine loop was recorded after muscle contractions. Muscle contractions were performed as described above, but there was a 1-min rest before a second set of fatiguing contractions was performed, making the entire contraction procedure 5 min. The microbubble injection and cine loop recording took place ∼3 min after the fatiguing muscle contractions. Mice in the HFD + R118 group were switched to regular HFD the night before perfusion measurements to study the chronic effect of R118. Animals that did not demonstrate an increase in contraction-induced perfusion were removed from the analysis.

Cardiac ultrasound.

Parasternal short-axis M-mode images were acquired using the Vevo 2100 system (Visualsonics) as previously described (56). Mice were anesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane, and heart rate was maintained between 450 and 500 beats/min for all measurements.

Micro-computed tomography.

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) was used to detect atherosclerosis in the aorta and femoral arteries as well as the vasculature of the gastrocnemius muscle. Numira Biosciences (Salt Lake City, UT) generated images and raw data on dissected muscles and arteries. Mice were perfused with saline until blood was removed and then perfused with 5–10 ml of 10% formalin. Tissues were washed three times for 10 min in PBS with rocking and then fixed in 10% formalin for 1 wk. Samples were stained with a proprietary reagent to detect atherosclerosis and scanned using the μCT 40 desktop micro-CT scanner (SCANCO Medical, Zurich, Switzerland). Images were collected at 15-μm resolution for the aorta and 10-μm resolution for the femoral artery using image acquisition parameters as previously described (35). Given the average diameter of a mouse aorta and femoral artery to be 1,000 and 300 μm, respectively, this imaging modality can detect atherosclerotic plaques that occlude as little as 2–3% of the vessel.

A separate set of mice was perfused with heparinized saline (300 U/l) at a flow rate of 4 ml/min using a syringe pump until blood was removed and then perfused with 5 ml of warmed AltaBlu (Numira Biosciences), a proprietary contrast agent that fills and provides a mold of the blood vessels. The contrast agent was allowed to cure at 4°C for 1 h. The gastrocnemius/plantaris muscle group from both the right and left legs was dissected and fixed in 10% formalin at 4°C. Each muscle group was imaged at 6-μm resolution using similar imaging parameters as previously described (64). This imaging resolution allows the visualization of small arterioles and venules but not capillaries. Muscle samples were sent for analysis only if the contrast agent had perfused in all tissues.

Immunofluorescence.

Frozen medial gastrocnemius muscles were sectioned (10 μm) with a cryostat and fixed in cold acetone for 10 min before immunofluorescent staining with anti-laminin (L9393, Sigma, 1:200 dilution) and anti-CD31 (AF3628, R&D Systems, 1:50 dilution) antibodies. Slides were digitally imaged with a ×4 objective using a Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescent microscope equipped with an Andor Neo sCMOS camera with a 2,160 × 2,160 pixel field of view. Image analysis was performed with CellProfiler. Thresholding was performed using Otsu's method minimizing weighted variance with three classes, and the middle class was assigned to background. Morphological techniques were applied to provide outlines for each fiber. Three serial sections per slide were analyzed and averaged for each animal.

Skeletal muscle AMPK activation.

R118 was delivered via oral gavage at 2.5, 5, or 10 mg/kg body mass (n = 4 mice/group) to wild-type mice fed the ND at 11.5 wk of age. Mice were euthanized by CO2, and gastrocnemius muscles were quickly dissected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen 60 min after dosing. Phosphorylation of AMPK (Thr172, no. 2535) and phosphorylated (p)acetyl-CoA-carboxylase (ACC; Ser79, no. 3661) were detected via Western blot analysis with antibodies from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Plasma samples were prepared by protein precipitation in an organic solvent mixture followed by centrifugation. The supernatant was analyzed by liquid chromotography tandem mass spectroscopy to provide quantitative determination of R118 concentration values in the plasma samples.

eNOS activation in primary human microvascular ECs and the aorta.

Human microvascular ECs (HuMECs; C2517AS, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) were grown to confluency in six-well dishes and treated with DMSO or R118 at 9, 27, 82, 244, 733, and 2,220 nM for 10 min. Cells were lysed and prepared for Western blot analysis using anti-eNOS (Ser1177, no. 9571), anti-AMPK (Thr172, no. 2535), anti-ACC (Ser79, no. 3661), and total eNOS (no. 9572; Cell Signaling).

Mice fed the HFD for 47 wk were treated with vehicle or 10 mg/kg body mass of R118 suspended in 0.5% hypromellose and 0.1% Tween 80 via oral gavage (n = 6 mice/group). Mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, blood was drawn via cardiac puncture, and plasma was collected and stored at −80°C. The thoracic aorta was quickly dissected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen 60 min after dosing. Aortic samples were homogenized, and p-AMPK (Thr172) and p-eNOS (Ser1177) protein expression was detected via Western blot analysis and normalized to actin (no. 8456, Cell Signaling) as a loading control.

Plasma assays.

Whole blood was drawn from the retroorbital sinus under brief isoflurane anesthesia after a 2-h fast after at least 17 wk of treatment. Blood was centrifuged, and plasma was collected and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Plasma was assayed for total nitrate and nitrite (kit K252-200, Biovision, Miliptas, CA) and asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA; kit ADM31-K01, Eagle Biosciences, Nashua, NH) according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Assessment of muscle mitochondrial function.

Muscles were collected under isoflurane anesthesia. Muscles were quickly dissected, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis. Citrate synthase activity was measured in the plantaris muscle of HFD-fed mice after 18 wk of treatment using a kit from Sigma (CS0720) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Enzyme activity was normalized to protein concentration using the bicinchoninic protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

In vitro kinase assay.

In vitro kinase activity of AMPK was performed at Carna Biosciences (Kobe, Japan). Full-length human AMPK-α1 or AMPK-α2 was coexpressed as an NH2-terminal glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fusion protein with GST-PRKAB1 and PRKAG1 using a baculovirus expression system. GST-AMPK constructs were purified using glutathione sepharose chromatography and activated with His-tagged Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 1. Activated GST-AMPK constructs were purified using glutathione sepharose chromatography. A mobility shift assay was used to assess the phosphorylation of SAMS peptide using a LabChip 3000 system (Caliper Life Science, Hopkinton, MA) in the presence or absence of 10 μM AMP (α1β1γ1-isoform) or 1 μM AMP (α2β1γ1-isoform) with 0.04, 0.2, and 1 μM R118.

O2 consumption rate.

HepG2 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in minimum essential Eagle medium supplemented with 10% FCS (Sigma). Mitochondria were isolated as previously described (57). Briefly, livers were rinsed before being minced with ice-cold buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM Tris (pH 7.4), and 2 mM EGTA (STE buffer). The liver slurry was homogenized using five to six strokes of a Dounce homogenizer and centrifuged for 3 min at 1,000 g. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 11,600 g. The pellet was resuspended in STE buffer, centrifuged, and then resuspended to a final concentration of 50 mg/ml. Purified mitochondria (5 μg) were added to 50 μl of MAS buffer (70 mM sucrose, 220 mM mannitol, 10 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA; pH 7.2) in 24-well plates. O2 consumption rates were performed using a XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience).

NADH oxidation assay.

Mitochondrial lysate from purified mouse livers (330 μg/ml) was added to tubes containing 2 mM NADH and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The conversion of NADH to NAD+ was calculated by measuring the change in absorbance at an optical density of 340 nm over the incubation period.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Investigators were not blinded to treatment during data collection since all tests provided objective end points. Comparisons between ND- and HFD-fed mice were made with two-tailed, independent t-tests. All other analyses were done using one- or two-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak's post hoc test. When multiple measures were made within the same mice, repeated measures were factored into the statistical design. The ROUT method (Q = 0.1%) was used to remove outliers. All analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 6) or SigmaPlot (version 12). Significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Mice maintained on a HFD develop obesity, glucose intolerance, and microvascular insufficiency in skeletal muscle.

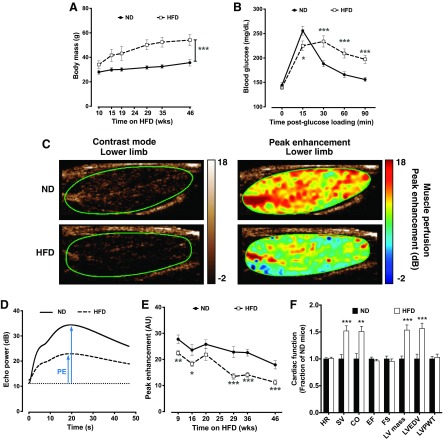

Similar to previous reports (60, 66), mice fed the HFD developed progressive obesity, and body mass exceeded ND-fed control mice by 22% after 10 wk and 52% after 46 wk of HFD (Fig. 1A). C57BL/6 mice with diet-induced obesity are known to develop glucose intolerance (1), and HFD-fed mice had clear reductions in glucose handling capabilities as measured with an oral glucose tolerance test (Fig. 1B). Despite the significant overlap that exists in the physical and metabolic profiles of mice with diet-induced obesity and patients with PAD, such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis (1, 60), assessments of lower limb skeletal muscle perfusion in DIO mice have not been previously described. We therefore used contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging to chronicle lower limb muscle perfusion over several months of HFD in sedentary mice. Significant deficits in resting muscle perfusion were first noticeable as soon as 9 wk after the HFD (19% less than ND-fed control mice) and progressed to a stable nadir of ∼40% below ND-fed control mice by 29 wk as assessed by peak enhancement, which is a measure of relative blood volume at steady-state perfusion (Fig. 1, C–E). Cardiac function was also assessed in aged, obese mice, and cardiac output was 50% greater in HFD-fed mice than in ND-fed mice, suggesting that cardiac function was not impaired (Fig. 1F), and similar to previously published results using the same diet and age of mice (3). These data point to the importance of both obesity and age in the development of peripheral vascular insufficiency.

Fig. 1.

Hindlimb skeletal muscle perfusion is reduced in male C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD). A: body mass. ND, normal diet. B: oral glucose tolerance testing after 46 wk of ND (n = 34) and HFD (n = 33). C: representative contrast-mode ultrasound images of the medial aspect of the lower hindlimb of ND- and HFD mice. D: peak enhancement (PE) is the maximum-minimum video intensity and is an indicator of blood volume. E: average PE in the hindlimb of ND-fed (n = 13–18) and HFD-fed (n = 21–35 except at 20 wk, where n = 12) mice. Only half of the HFD-fed mice were measured at the 20-wk time point. AU, arbitrary units. F: cardiac function in ND-fed (n = 11) and HFD-fed (n = 10) mice. HR, heart rate; SV, stroke volume; CO, cardiac output; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; LV mass, left ventricular (LV) mass; LVEDV, LV end-diastolic volume; LVPWT, LV posterior wall thickness. Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed with two-tailed, independent t-tests between ND and HFD at each time point. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Significant and progressive exercise intolerance develops in aged, obese mice by the 29th wk of HFD.

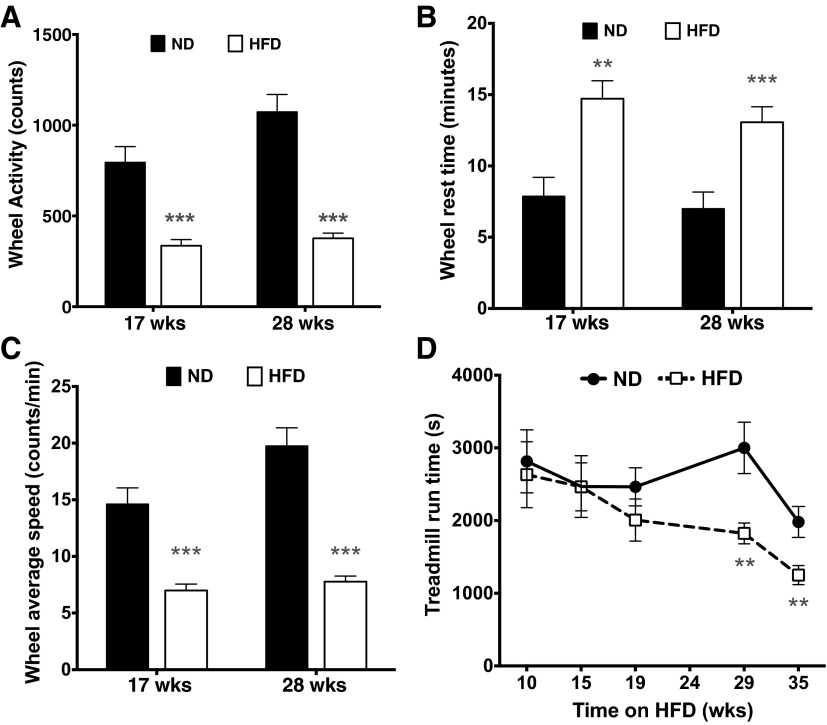

Patients with PAD (55) and mice fed a HFD (30) are known to develop exercise intolerance; therefore, we sought to longitudinally characterize exercise capacity in mice maintained on a HFD. When given a 1-h wheel running test, DIO mice voluntarily ran at least 50% less than mice on standard chow after 17 wk of HFD, and this finding was replicated after 28 wk of diet (Fig. 2A). This impaired performance was due to both a higher frequency of rest periods (Fig. 2B) and a slower running speed during activity (Fig. 2C) (18). Similarly, DIO mice ran ∼40% less during the treadmill test than mice fed normal chow, but this did not manifest until 29 wk of HFD (Fig. 2D). It is noteworthy that these decreases in treadmill exercise performance did not occur until at least 2–4 mo after the earliest perfusion deficits were first observed at 9 wk after the HFD (Fig. 1E), suggesting the sequential and gradual development of exercise intolerance secondary to initial alterations in muscle perfusion.

Fig. 2.

Exercise capacity is impaired in male C57BL/6 mice fed a HFD. A: voluntary wheel running activity during a 1-h timed test in ND- and HFD-fed mice. B: rest time (1-min periods with zero counts). C: average speed calculated when mice were engaged with the wheel. Sample sizes for ND-fed mice were as follows: 17 wk (n = 16) and 28 wks (n = 18); sample sizes for HFD-fed mice were as follows: 17 wk (n = 32) and 28 wk (n = 29). D: treadmill exhaustion time in ND- and HFD-fed mice. Sample sizes for ND-fed mice were as follows: 10–29 wk (n = 18) and 35 wk (n = 16); sample sizes for HFD-fed mice were as follows: 10–15 wk (n = 33), 19 wk (n = 17), 29 wk (n = 27), and 35 wk (n = 26). Only half of the HFD-fed mice were tested at 19 wk of HFD. Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed with two-tailed, independent t-tests between ND and HFD at each time point. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Decreased skeletal muscle perfusion in DIO mice occurs independent of large vessel atherosclerosis.

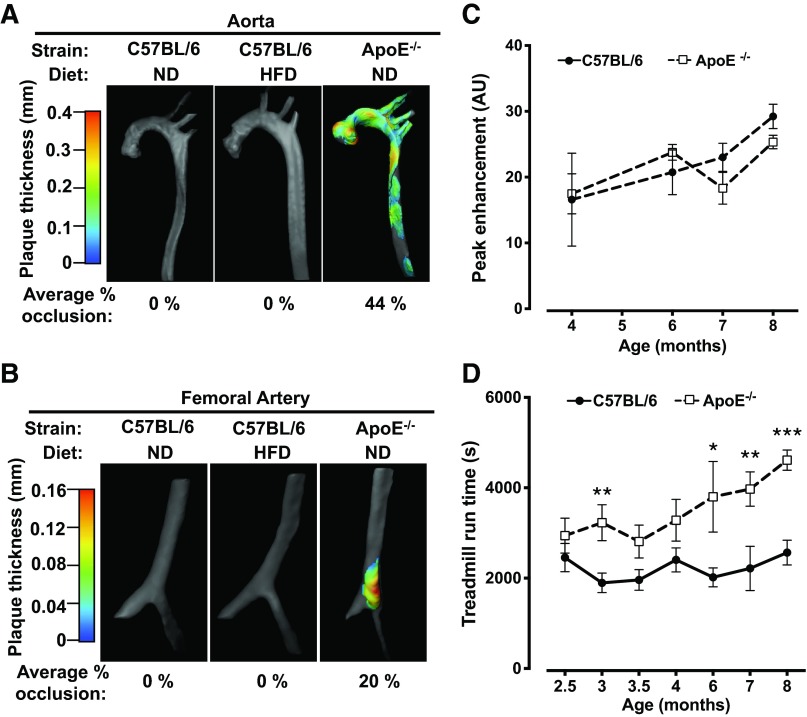

Since decreased blood flow in patients with PAD occurs in the context of atherosclerotic occlusion of large vessels (37), we used 10- to 15-μm resolution CT imaging of both the aorta and femoral arteries of mice chronically maintained on a HFD to investigate whether or not occlusive atherosclerosis was present. For these experiments, C57BL/6 ApoE−/− mice were used as positive controls since they are known to develop atherosclerosis (35, 73). Additionally, exercise performance was also evaluated in ApoE−/− mice. Extensive atherosclerosis was detected in the aorta in five of five 65-wk-old ApoE−/− mice, but no atherosclerosis was detected in six of six wild-type C57BL/6 mice even after 49–73 wk of HFD (Fig. 3A). Similarly, atherosclerosis was also detected in the femoral arteries in three of five ApoE−/− mice examined, but there were no detectable plaques noted in the femoral arteries of wild-type C57BL/6 mice on either diet (Fig. 3B). Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging of the lower limb muscles of ApoE−/− mice from 2.5 to 8 mo of age demonstrated normal levels of perfusion relative to wild-type mice (Fig. 3C), indicating that significant occlusive disease and/or microvascular dysfunction was not present in these mice. In addition, functional exercise capacity in ApoE−/− mice was equal to or greater than C57BL/6 wild-type mice, as demonstrated in treadmill exercise tests (Fig. 3D). Thus, despite extensive atherosclerosis, ApoE−/− mice are not satisfactory as a model for exercise intolerance associated with PAD since they display no functional deficits in muscle perfusion or exercise capacity.

Fig. 3.

Obesity-induced reductions in hindlimb perfusion are independent of large vessel atherosclerosis. A and B: representative images of atherosclerosis in the aorta (A) and femoral artery (B) from ND-fed (n = 5), HFD-fed (n = 6), and apolipoprotein E gene (ApoE)-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice (n = 5). Mice were assessed after 49–73 wk of HFD, and ApoE−/− mice were 65 wk old. C: C57BL/6 and ApoE−/− mice were also tested for skeletal muscle perfusion (n = 5–7 mice/group except at the age of 4 mo, where n = 3 mice/group). D: treadmill exercise capacity in C57BL/6 and ApoE−/− mice (n = 14–20 mice/group). Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed with independent t-tests between C57BL/6 and ApoE−/− mice at each time point. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

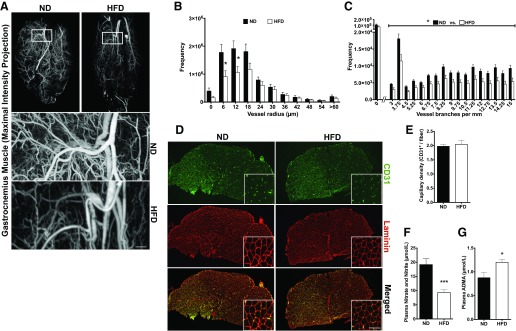

Vascular insufficiency in HFD-fed mice can be attributed to microvascular dysfunction within skeletal muscle.

Since occlusive atherosclerosis was unlikely to account for the observed decreases in muscle perfusion in HFD-fed mice, we used 6-μm resolution CT imaging to anatomically assess the status of the vascular network within the lower limb muscles (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, mice maintained on the HFD had significantly fewer detectable vessels with inner radii below 12 μm relative to ND-fed control mice. This vessel range corresponds to second- and third-order arterioles and small venules (67). Since the frequency of branch points per length of vessel increases as arteries transition into second- and third-order arterioles before progressing into capillary beds (67), a relative lack of detectable small vessels above the 6-μm detection limit will also register as a decrease in the overall number of branches, and this was the case for HFD-fed mice compared with ND-fed control mice (Fig. 4C). Capillary density was similar between ND- and HFD-fed mice (Fig. 4, D and E). Collectively, these observations suggest that the poor muscle perfusion observed in aged, obese mice is related to a substantial increase in microvascular tone.

Fig. 4.

Microvascular dysfunction in skeletal muscle and nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability contribute to vascular insufficiency in aged, obese mice. A: representative micro-computed tomography (CT) images of AltaBlu-filled gastrocnemius/plantaris muscles delineating blood vessels after 73 wk of ND (n = 7) or HFD (n = 6) in male C57BL/6 mice. Scale bar = 200 μm. B: frequency distribution of vessel radius. C: frequency distribution of vessel branching. D: representative ×40 medial gastrocnemius muscle sections depicting capillary density (CD31+: green; laminin: red). Scale bar = 100 μm. Insets show higher-magnification images. E: quantification of capillary density. F and G: plasma total nitrate and nitrite concentration (F) and plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA; G) after 46 wk of HFD (n = 8 mice/group). Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed with two-tailed, independent t-tests between ND and HFD. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Endothelium-derived NO is critical for proper vascular tone, and patients with PAD have evidence of endothelial dysfunction associated with reduced levels of NO bioavailability (36, 68). We investigated whether similar mechanisms might contribute to the lack of proper vascular tone in the muscles of aged, obese mice. NO is quickly converted to nitrate and nitrite in the plasma, and these byproducts can be used as an indicator of NO bioavailability. Total levels of nitrate and nitrite were 52% lower in aged, obese mice relative to ND-fed control mice (Fig. 4F). ADMA is an endogenous inhibitor of NOS, and circulating ADMA levels are associated with PAD symptom severity (69). In the present study, aged, obese mice had ADMA levels that were 37% higher than ND-fed control mice (Fig. 4G). Thus, decreased NO bioavailability may contribute to the overall decrease in muscle perfusion and small vessel detection.

R118 activates both AMPK and eNOS in vitro and in vivo.

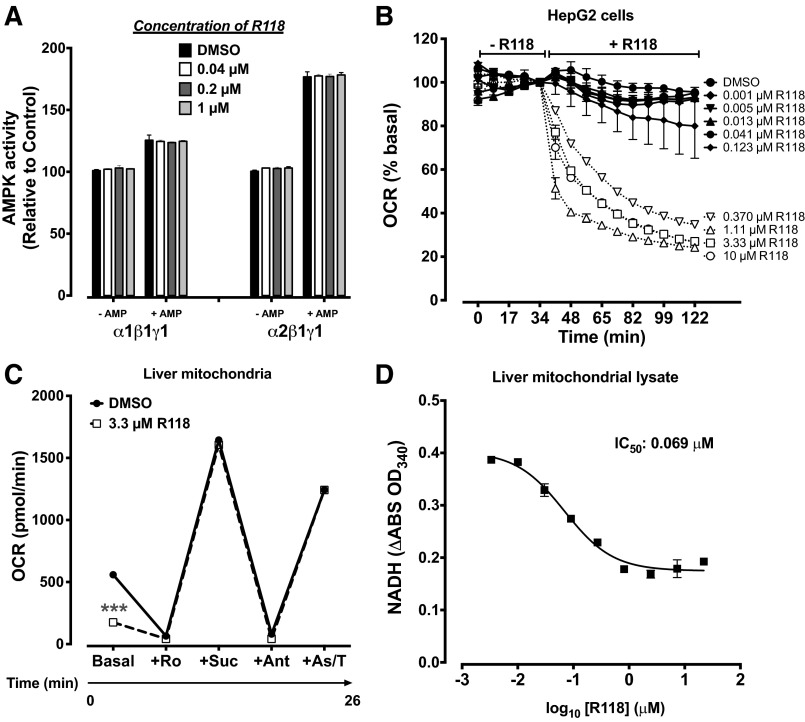

Since exercise training can significantly delay the time to claudication (54), and it is known to be a potent stimulator of AMPK (42), we hypothesized that pharmacological activation of AMPK might prove useful for the treatment of exercise intolerance associated with PAD. As part of a medicinal chemistry program directed toward activators of AMPK, we discovered a potent, small-molecule AMPK activator, R118 (21). AMPK activity is highly sensitive to shifts in the ratios of AMP, ADP, and ATP through allosteric mechanisms. R118 indirectly activates AMPK by influencing the production of these nucleotides through inhibition of mitochondrial complex I, as measured by O2 consumption rate cells or purified mitochondria, and NADH accumulation in mitochondrial lysates (Fig. 5, A–D). R118 has an EC50 of 270 nmol/l for AMPK activation in C2C12 myotubes. When R118 is administered in vivo, it dose dependently increases AMPK phosphorylation in gastrocnemius muscles of mice within 1 h at exposures as low as 690 nmol·h·l−1 (AUC24 h; Fig. 6, A and B).

Fig. 5.

R118 activates 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) through an indirect mechanism of action. A: R118 does not increase AMPK activity in vitro. Kinase activity was measured in the presence or absence of 1 μM AMP for α1β1γ1 and 10 μM for α2β1γ1 (n = 2/group). B: R118 inhibits mitochondrial respiration in a dose-dependent fashion. HepG2 cells were incubated with 0.05% DMSO or different concentrations of R118, and the O2 consumption rate (OCR) was measured in duplicate using a XF24 Seahorse instrument. All data are normalized to the time point before the addition of R118. C: R118 inhibits mitochondrial respiration by inhibiting complex I. The OCR was measured in 5 μg of purified mouse liver mitochondria in triplicate in the basal state with the addition of a complex I inhibitor [rotenone (Ro)], a stimulator of complex II [succinate (Suc)], an inhibitor of complex II [antimycin A (Ant)], and a stimulator of complex IV [ascorbate/N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (As/T)]. Sample sizes were as follows: DMSO (n = 3), 0.3 μM R118 (n = 4), and 3.3 μM R118 (n = 4). D: NADH oxidation was blunted by R118. Purified liver mitochondrial lysates were analyzed spectrophotometrically in duplicate for the conversion of NADH to NAD+ in the presence of 2 mM NADH. ***P < 0.001 vs. DMSO.

AMPK is known to directly regulate eNOS activity through the phosphorylation of Ser1177 (8), and treatment of primary HuMECs with R118 potently induced the phosphorylation of eNOS (Fig. 6C). Similarly, phosphorylation of eNOS (Ser1177) was significantly induced in the aorta of mice treated with R118 (Fig. 6D). Thus, R118 effectively activated AMPK in muscle and both AMPK and its downstream substrate, eNOS, within vascular tissue.

Treatment of aged, obese mice with an AMPK activator increases voluntary wheel running distance and average running speed, decreases the frequency of rest periods, and prevents the progressive decrease in treadmill exercise capacity as early as 5 wk posttreatment.

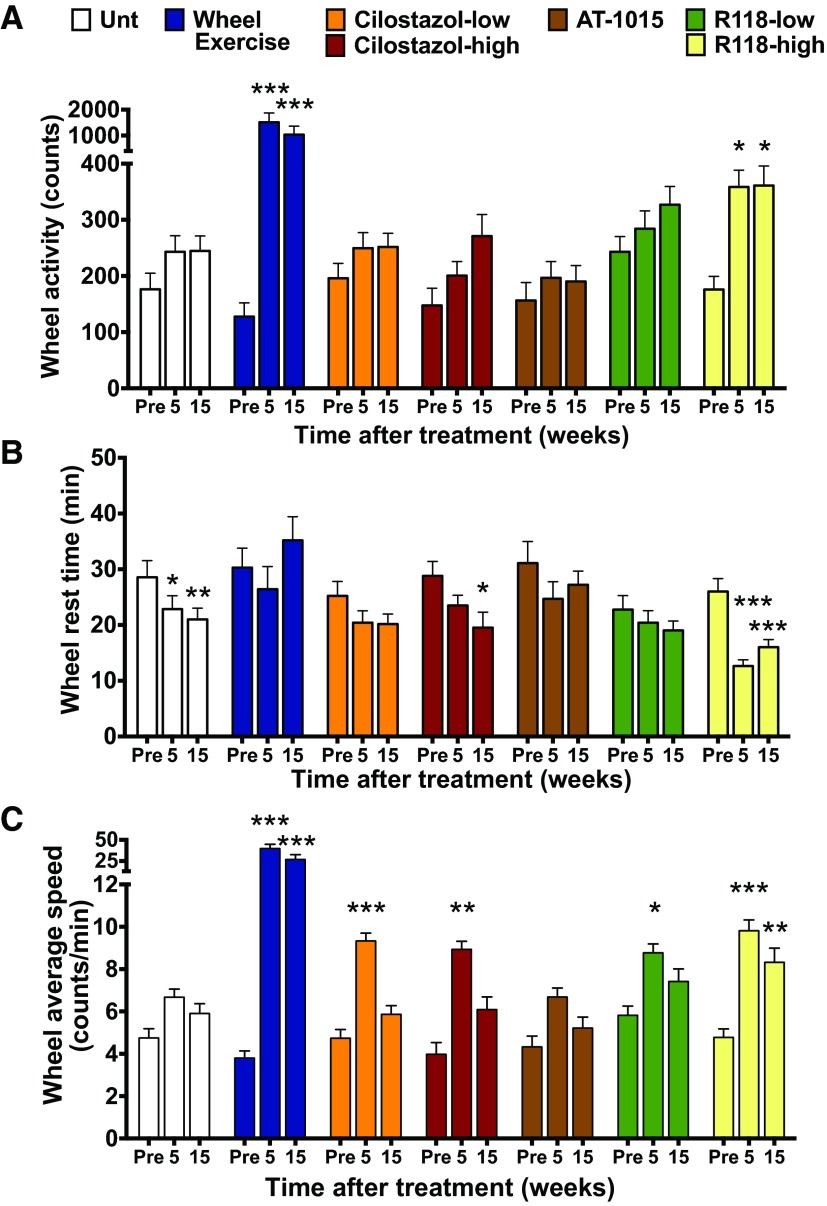

Using R118, the potential therapeutic benefit of AMPK activation for addressing vascular insufficiency and exercise intolerance was assessed in 53-wk-old DIO mice that had already progressed to a chronic disease state. Wheel running and treadmill tests were used to assess whether the treatment was capable of improving exercise performance. R118 dose dependently improved exercise capacity at both 5 and 15 wk posttreatment during the activity wheel test. Mice treated with the high dose of R118 (366 mg/kg HFD) increased their wheel running counts twofold (Fig. 7A), decreased the frequency of rest periods by 50% (Fig. 7B), and significantly increased their average running speed during periods of active wheel cycling (Fig. 7C). Estimated plasma exposures (AUC24 h) of R118-treated mice measured at the end of the study were 4,286 and 7,603 nmol·h·l−1 for the low (244 mg/kg HFD) and high doses, respectively, which are exposures sufficient to activate AMPK and eNOS in vivo (Fig. 6). In contrast, HFD mice that were untreated did not increase their wheel running counts despite small gains in rest time. Body masses were not different between untreated HFD and R118-treated mice during each wheel exercise test (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Exercise capacity is improved with R118. Mice were singly housed with a running wheel for 1 h for 3 consecutive days. Sample sizes for groups were as follows: ND (n = 32), HFD untreated (Unt; n = 31), HFD + wheel exercise (n = 16), HFD + low-dose cilostazol (cilostazol-low; n = 33), HFD + high-dose cilostazol (cilostazol-high; n = 17), HFD + AT-1015 (n = 17), HFD + low-dose R118 (R118-low; n = 29), and HFD + high-dose R118 (R118-high; n = 32). A and B: total counts (A) and rest time (B), defined as the number of 1-min intervals without a count. C: average speed was determined only when mice were actively engaged with the wheel. All data were determined and averaged over 3 days. Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Holm-Sidak's post hoc test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. pretreatment (Pre).

Cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase 3A inhibitor, is currently used clinically to treat claudication (58), and there is limited evidence that part of its mechanism may involve weak activation of AMPK (61); therefore, cilostazol was used as a comparator throughout these experiments. Cilostazol did not improve wheel running counts, but average running speed transiently increased twofold at 5 wk posttreatment. The estimated exposures for the low (550 mg/kg HFD) and high (733 mg/kg HFD) doses of cilostazol were 9,665 and 35,112 nmol·h·l−1 (AUC24 h; n = 5 mice/group), respectively. Importantly, the exposure obtained with the high dose of cilostazol was similar to that achieved clinically in humans during treatment of claudication (58). AT-1015 is a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist that showed promise in other animal models of PAD (27–29) but failed to improve the time to claudication in the clinic (23). In the present study, treatment with AT-1015 did not lead to improvements in total wheel counts, average speed, or rest time, similar to HFD-fed control mice. Plasma levels of AT-1015 were also confirmed to verify drug delivery (AUC24 h: 882 nmol·h·l−1, n = 5). Regular exercise can also improve symptoms of claudication (54), and we therefore housed mice individually with activity wheels to generate an exercised control group. Daily exercise bouts averaged 0.9 km/day at the beginning of the study and reached a peak of 4.4 km/day after 10 wk. As predicted, mice that exercised regularly in the wheels improved their 1-h timed wheel running test and did so by substantially increasing their wheel running speed without decreasing their rest time.

As a further test of exercise capacity, a treadmill endurance test was conducted with all groups of mice (Table 1). As expected, exercise training was effective at improving treadmill performance. Interestingly, R118 treatment maintained treadmill run time with advancing age, but this was only effective in the low-dose group. A t-test was used to compare untreated and R118-treated mice, and R118-treated mice (low dose) ran ∼45% farther at both the 6- and 16-wk assessment periods (P < 0.026). In contrast, mice treated with either dose of cilostazol failed to prevent the progressive decline in treadmill performance. These data demonstrate that AMPK activation by R118 was effective at improving exercise performance in aged, obese mice that had already developed chronic peripheral microvascular insufficiency and exercise intolerance.

Table 1.

Treadmill endurance capacity is maintained in mice treated with R118

| HFD-Unt | HFD + Wheel Exercise | HFD + Low-Dose C Cilostazol (550 mg/kg HFD) | HFD + High-Dose Cilostazol (733 mg/kg HFD) | HFD + AT-1015 | HFD + Low-Dose R118 (244 mg/kg HFD) | HFD + High-Dose R118 (366 mg/kg HFD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of mice/group | 26 | 12 | 30 | 17 | 14 | 28 | 30 |

| Pretreatment | 746 ± 46 | 735 ± 24 | 818 ± 50 | 845 ± 86 | 640 ± 43 | 852 ± 50 | 842 ± 63 |

| 6 wk posttreatment | 680 ± 41 | 5,216 ± 1,151† | 725 ± 50* | 674 ± 61 | 630 ± 53 | 927 ± 96 | 703 ± 42 |

| 16 wk posttreatment | 595 ± 43† | 4,913 ± 1,234† | 647 ± 44‡ | 644 ± 72 | 571 ± 43 | 826 ± 80 | 693 ± 52 |

Data are presented as means ± SE. The maximum time of the test was 9,000 s. HFD, high-fat diet. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Holm-Sidak's post hoc test (pretreatment vs. 6 wk; pretreatment vs. 16 wk).

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.001 vs. pretreatment.

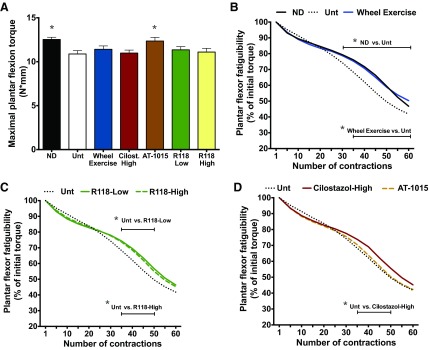

Aged, obese mice demonstrate increased muscle weakness and fatigue during repetitive contractions, and these changes can be attenuated by R118.

In addition to vascular dysfunction, skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and strength are also compromised in PAD (51, 55). Lower limb skeletal muscle strength was assessed in vivo by stimulating the sciatic nerve with electrodes inserted percutaneously to measure maximal isometric torque of the plantar flexors, similar to a calf raise exercise. Untreated HFD-fed mice had 13% less muscle strength than ND-fed mice (Fig. 8A), but R118 had no effect on absolute muscle strength when tested at least 17 wk posttreatment. Muscle fatigability was assessed by force loss during 60 consecutive in vivo plantar flexion contractions. Significant differences were detected between nonobese control and HFD-fed mice during contraction-induced muscle fatigue, and this was reversed with wheel running training (Fig. 8B). Treatment with the AMPK activator (Fig. 8C) and cilostazol (Fig. 8D) also significantly attenuated muscle fatigability, whereas AT-1015 had no effect, suggesting that both R118 and cilostazol could directly delay skeletal muscle fatigue during exercise.

Fig. 8.

R118 improves skeletal muscle fatigue after in vivo plantar flexion contractions. The following groups of mice were evaluated: ND (n = 18), HFD-Unt (n = 15), HFD + wheel exercise (n = 15), HFD + cilostazol-high (n = 15), HFD + AT-1015 (n = 16), HFD + R118-low (n = 9), and HFD + R118-high (n = 16). A: maximal isometric torque. B–D: plantar flexion torque was measured during fatiguing contractions in ND, Unt, and wheel-exercised mice (B), R118-treated mice (C), and cilostazol- and AT-1015-treated mice (D). Exercise consisted of 60 plantar flexion contractions via stimulation of the sciatic nerve with percutaneous electrodes at 100 Hz, 200-ms train duration, and 0.15-ms pulse duration. One contraction was elicited every 2 s for 2 min. Data were collected 17–23 wk posttreatment. For maximal isometric torque, data are presented as means +/- SE. For fatigue, only means are presented. The Untreated (Unt) group is regraphed in each Fig. and represents the same data set. Data were analyzed by 1-way or 2-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak's posthoc. Bars signify contractions that are different from HFD-Unt. *P < 0.05.

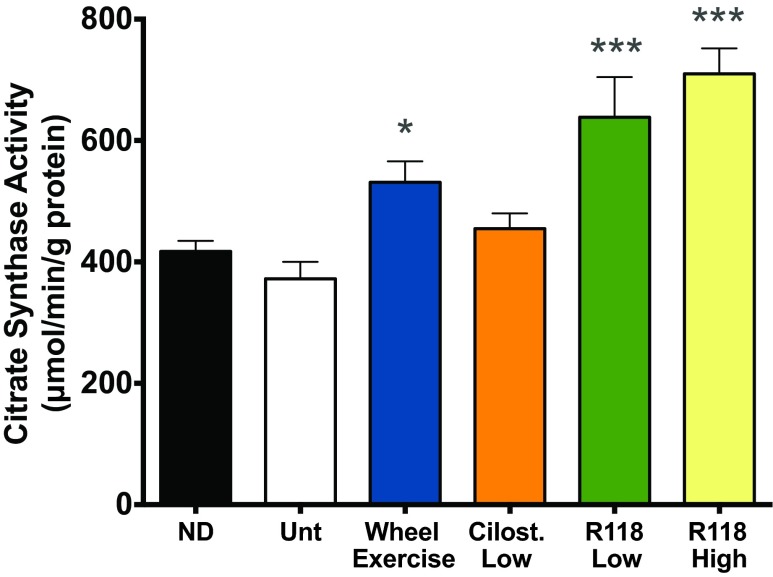

R118 improves mitochondrial function.

Exercise, AICAR, and mild mitochondrial stress stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis through a process known as mitohormesis (17, 45, 70). Since complex I inhibition using R118 could regulate this process, we measured citrate synthase activity as a marker of mitochondrial function. Citrate synthase activity in the plantaris muscle increased 70–90% with the low or high doses of R118 over untreated HFD-fed mice (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Skeletal muscle mitochondrial function is improved with R118. Plantaris muscles were collected 18 wk after treatment. A sample size of n = 7–8 was used for all measurements, except the HFD + Wheel (n = 5). Data are presented as mean +/- SE. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak's posthoc (Untreated vs. all other treatments). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. HFD-Unt.

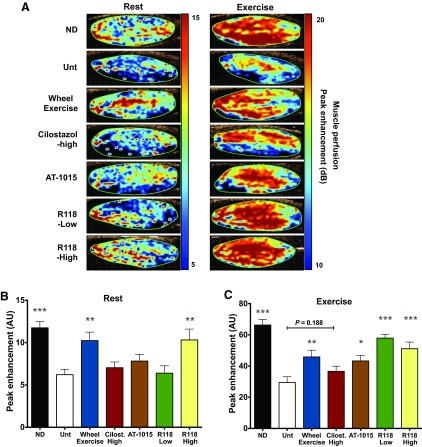

Chronic microvascular insufficiency in aged, obese mice is normalized in both resting and contracting muscle after long-term treatment with R118.

Since claudication occurs during exercise and skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise is attenuated in patients with PAD (34), we measured perfusion in both the resting and exercised state of the same limb. In addition to having less muscle perfusion at rest, untreated HFD-fed mice had ∼60% less perfusion to the muscle compared with ND-fed control mice after fatiguing muscle contractions (Fig. 10, A–C). R118-driven AMPK activation was particularly effective at almost fully reversing the dysfunctional vascular state present in aged, obese mice. R118 treatment improved muscle perfusion by 66% at rest and by as much as 97% immediately after exercise. Similar effects were seen in the wheel-trained mice, but, in this case, the improvements were only ∼50% greater than HFD-fed sedentary mice. Cilostazol failed to improve any marker of skeletal muscle perfusion at rest or after muscle contractions, whereas AT-1015 moderately improved perfusion only after plantar flexion contractions.

Fig. 10.

R118 improves skeletal muscle perfusion at rest and after exercise. Mice were fed a ND (n = 18), HFD-Unt (n = 15), HFD + Wheel (n = 15), HFD + Cilostazol-high (n = 14), HFD + AT-1015 (n = 13), HFD + R118-low (n = 9), or HFD + R118-high (n = 16). Hind limb muscle perfusion was measured with contrast-enhanced ultrasound at rest and after exercise in the same limb. Exercise consisted of 120 plantar flexion contractions via stimulation of the sciatic nerve with percutaneous electrodes at 100 Hz, 200-ms train duration, and 0.15-ms pulse duration. One contraction was elicited every 2 s for 2 min, followed by a 1-min rest and a second set of 60 contractions. Data were collected 17–22 wk posttreatment. A: representative peak enhancement images before (rest) and after fatiguing muscle contractions (exercise). B and C: peak enhancement at rest (B) and after exercise (C). Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak's post hoc test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. HFD-Unt.

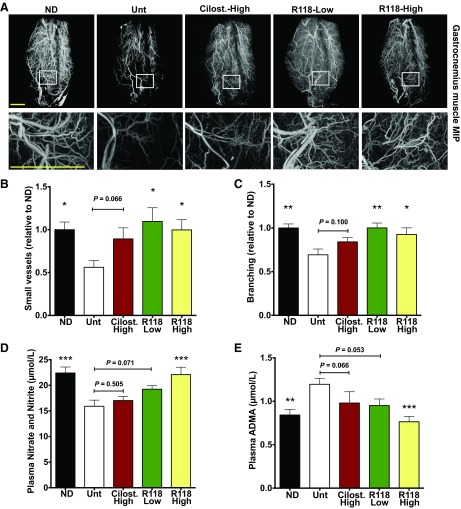

Treatment with R118 leads to a greater detection of small vessels at rest and during exercise.

Having demonstrated that mice chronically maintained on a HFD have evidence of fewer dilated small vessels, we conducted a similar assessment of the vascular network within the lower limb muscles of R118-treated animals (Fig. 11A). Mice treated with either dose of R118 had a higher number of detectable small vessels (≤12 μm in radius) and more branching (≥3 branch points/mm) than mice fed the HFD (Fig. 11, B and C). There was a trend for cilostazol to improve small vessel detection, coinciding with the trend to improve perfusion, but this did not achieve statistical significance.

Fig. 11.

R118 increases the number of detectable small vessels and branch points per vessel length in skeletal muscle, and this is related to NO bioavailability. The left leg was subjected to 120 plantar flexion contractions (exercise), and the contralateral limb served as a control (rest). There was no effect of exercise or an interaction, so data presented are the main effects of treatment (vessel radius: P = 0.034; vessel branching: P = 0.004). A: representative micro-CT images of the gastrocnemius muscle from the unexercised leg from the ND (n = 14), HFD-Unt (n = 12), HFD + cilostazol-high (n = 12), HFD + R118-low (n = 12), and HFD + R118-high (n = 12) groups. Muscles were collected 27–29 wk posttreatment. AT-1015-treated mice were not tested. Scale bar = 2 mm. B: mean number of small vessels (≤12 μm in radius). C: vessels with multiple branch points (≥3 branch points/mm). D and E: plasma nitrate and nitrite (D) and plasma ADMA (E) from the ND (n = 18), HFD-Unt (n = 18), HFD + cilostazol-high (n = 14), HFD + AT-1015 (n = 18), HFD + R118-low (n = 18), and HFD + R118-high (n = 18) groups. Plasma samples were collected 25 wk posttreatment. Data are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak's post hoc test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 vs. HFD-Unt.

Given that that aged, obese mice have reduced NO bioavailability and R118 can induce the phosphorylation of eNOS in ECs in vitro and in vivo, we examined NO bioavailability in R118-treated mice. Total plasma nitrate and nitrite levels (Fig. 11D) were 40% greater and plasma ADMA levels (Fig. 11E) were 40% lower in R118-treated mice compared with untreated HFD-fed control mice. Both cilostazol- and AT-1015-treated mice had ADMA and total nitrate and nitrite levels similar to untreated HFD-fed control mice. Collectively, these data suggest that AMPK activation by R118 modulates microvascular tone by mechanisms that include increased NO bioavailability, contributing to the enhanced skeletal muscle perfusion in both the resting and exercising states.

DISCUSSION

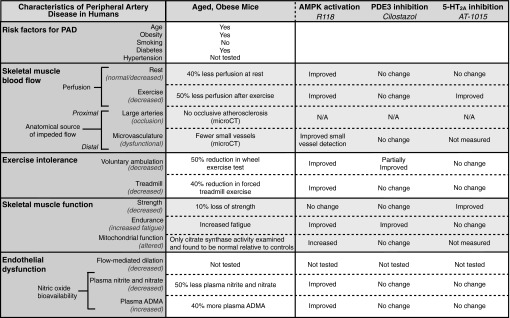

PAD is a serious medical condition that significantly limits patient mobility and is independently related to increased mortality rates (59). More effective treatments are needed to improve exercise performance and walking ability. Much of the difficulty with current preclinical animal models arises from the fact that rodents undergo rapid and robust arteriogenesis in response to surgical reductions in blood flow, and measuring the recovery of blood flow in mice has not translated into new therapies for intermittent claudication (75). Thus, alternatives to the current models are needed. The present study demonstrates numerous functional similarities between aged, obese mice and patients with PAD suffering from intermittent claudication, thereby suggesting this model as a suitable tool for exploring disease mechanisms and assessing the therapeutic potential of new treatments (Fig. 12). Evidence is provided to show that aged, obese mice progressively develop lower limb microvascular insufficiency, reduced strength, premature muscle fatigue, and a profound reduction in exercise performance that is accompanied by frequent bouts of rest. Importantly, these pathological changes occur gradually over time and are characterized longitudinally using multiple functional assessments. Furthermore, we demonstrate the presence of reduced muscle perfusion and impaired NO bioavailability independent of large vessel occlusive atherosclerosis. AMPK activation is identified as a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of intermittent claudication based on the ability of a small-molecule AMPK activator to improve NO bioavailability, normalize muscle perfusion, reduce fatigability, increase mitochondrial function, and significantly improve exercise performance.

Fig. 12.

Similarities between patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) and aged, obese mice and the efficacy of R118, cilostazol, and AT-1015 in this animal model. All data represent chronic treatment with different compounds. PDE3, phosphodiesterase 3; 5-HT, serotonin; N/A, not applicable.

Although others have documented altered ex vivo vasodilatory responses in isolated arteries of obese mice and rats (5, 11), this is the first study to show perturbed in vivo skeletal muscle perfusion in DIO mice. These differences developed relatively early in the course of the disease, suggesting that obesity can trigger microvascular dysfunction. These changes progressed gradually and then persisted over long periods of time, a situation akin to the development of PAD in humans (75). It is worth noting that perfusion was measured directly in limb muscles using contrast-enhanced ultrasound, and when this same approach is applied to patients with PAD, it is predictive of claudication (34). Furthermore, the magnitude of decreased muscle perfusion observed in aged, obese mice was very similar to that observed in patients with PAD symptomatic for intermittent claudication (40–50% below normal controls) (4). Importantly, these mice demonstrated clear impairments in the ability to mount reactive hyperemic responses during exercise, and this is one of the defining features of PAD in humans. The loss of perfusion observed in aged, obese mice was more gradual and moderate relative to surgical ligation-based models in which severe reductions are typically generated in first few days after surgery (80–90% reduction relative to baseline) (14).

In humans with PAD, atherosclerotic occlusions in peripheral arteries are not the only factor contributing to decreased muscle perfusion, and microvascular dysfunction is increasingly being recognized as an important aspect of this disease (9, 46, 68). In the present study, no evidence of occlusive atherosclerotic plaques could be found, even after 49–73 wk of HFD, in either the aortas or femoral arteries of aged, obese mice using micro-CT imaging. The resolution of this technique was sufficient to detect meaningful plaque deposits, since ApoE−/− mice had clear atherosclerosis as far down as the tibial-popliteal bifurcation of the femoral artery. Even rodents with verifiably high plaque loads, such as the ApoE−/− mice examined here, failed to develop any detectable perfusion loss in peripheral limbs. Interestingly, exercise capacity was also the same or greater than in ApoE−/− mice compared with age-matched wild-type mice, and this test was performed in the same group of mice at multiple time points. Others have also demonstrated that the distance run during an incremental treadmill test to exhaustion is similar between young wild-type and ApoE−/− mice (38, 44). These data would suggest that the presence of atherosclerosis in peripheral arteries alone is not a primary factor contributing to exercise intolerance.

Since there was no evidence of large conduit atherosclerosis, the lack of proper hindlimb perfusion in aged, obese mice appears to stem from microvascular dysfunction. High-resolution CT imaging detected a significant decrease in the number of vessels below 12 μm in radius, which tend to be more branched, in the gastrocnemius muscles of these mice. One advantage of high-resolution CT imaging is that it captures quantifiable maps of the vascular network within the entire muscle in its normal physiological state. However, one disadvantage of this approach is that the resolution of the current instruments limits detection to only those vessels with an inner radius of >6 μm. Thus, capillaries are never detected, and vessels capable of dynamically adjusting their lumen size in a range near this detection threshold, such as small arterioles, might be expected to transition between detectable and undetectable periods, depending on their state of dilation. In our study, the analysis of gastrocnemius cross-sections using high-resolution microscopy demonstrated that capillary density was the same between control and HFD-fed mice, ruling out rarefaction as the reason for reduced perfusion in HFD-fed mice. Collectively, these data sets suggest that these two groups share similarly dense networks of vasculature but that HFD-fed animals persist in a state of increased microvascular tone, leading to reduced levels of tissue perfusion. Reduced NO bioavailability, as evidenced by decreased total nitrate and nitrite levels and increased concentrations of circulating ADMA, suggest a mechanistic role for eNOS and endothelial dysfunction in the genesis of this low-perfusion state, although we cannot rule out that microvascular dysfunction in this model is multifactorial. There is evidence for underlying endothelial dysfunction in patients with PAD (25, 36, 50, 72), and it has been hypothesized to be related to functional performance (25, 36, 50). Furthermore, cardiovascular risk factors predispose individuals to endothelial dysfunction, and if the cardiovascular risk factors are not controlled, endothelial dysfunction can directly contribute to the development of atherosclerosis (12, 62). One of the more surprising outcomes from clinical trials examining lower limb revascularization surgeries in patients with PAD was that exercise performance was not consistently restored (19). This suggests that other factors, especially those controlling microvascular function, might have a major role in determining functional performance in these patients (9, 46).

Interestingly, detectable decreases in treadmill exercise performance did not develop until 2–4 mo after the first documented decrease in perfusion. This suggests that an absolute or temporal threshold of microvascular insufficiency must be reached before exercise performance is impacted. The delayed decrease in exercise performance is consistent with prevailing theories on how intermittent claudication arises in PAD. For example, one hypothesis is that limitations in blood flow result in continuous cycles of ischemia-reperfusion injury during transient exercise episodes. The ensuing oxidative stress becomes cumulatively injurious over time to ECs, muscle tissue, and even distal motor axons (4, 36, 53). In exercise wheel tests, it was clear that performance decreases were largely the result of an increased frequency of rest periods and a slower overall pace. Although we cannot determine the exact mechanism behind exercise intolerance (e.g., claudication or fatigue), more rest periods could be reflective of lower limb discomfort, such as that experienced during claudication in patients with PAD. With advancing disease progression, DIO mice performed in both measures of exercise capacity at levels ∼50% of control mice, and this drop is similar to the documented exercise reduction in patients with PAD experiencing intermittent claudication (2, 55). PAD is further associated with muscle weakness in the affected limb (55). Aged, obese mice also displayed decreased lower limb strength, measured in vivo by maximal isometric plantar flexion torque. This was accompanied by clear increases in fatigability within the same muscles during repeated serial contractions. Together, these observations demonstrate that aged, obese mice share many of the same comorbidities as patients with PAD, such as advancing age, obesity, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance, and are also functionally similar in the temporal development of reduced muscle perfusion, muscle dysfunction, and exercise intolerance. These similarities occurred despite the absence of large vessel occlusive atherosclerosis, providing evidence that microvascular dysfunction may prominently contribute to claudication.

To help further validate using aged, obese mice to test exercise intolerance, we treated mice with cilostazol or AT-1015 and also exercised mice in activity wheels. Cilostazol, at blood exposures comparable to clinical use in humans, was able to improve some of these parameters but not all. In contrast, AT-1015 failed to show meaningful improvement in any functional exercise assessments, similar to its performance in clinical trials (23). Not surprisingly, mice with unlimited access to an activity wheel made substantial improvements in voluntary and forced exercise tests. Exercise also offers alleviation of claudication symptoms in patients with PAD, although the effectiveness of this type of intervention is much more pronounced in this study than in the human population. The reason for the substantial improvements with exercise seen in this model (5- to 10-fold improvement) compared with humans (2-fold improvement) is most likely due to the volume of exercise performed (∼4 vs. <1 km/day) (20) and the confounding effect of weight loss, as wheel-exercised mice experienced a 15% reduction in body mass not seen with any of the other treatments.

In our experiments, pharmacological activation of AMPK significantly improved exercise performance. Interestingly, in wheel exercise tests of mice treated with the AMPK activator R118, overall exercise capacity was improved by decreasing the frequency of rests taken during the test period and by running at a higher average speed during active episodes. The benefits of cilostazol were not as robust as those observed with R118, and the time needed for functional improvements was 10 wk longer relative to R118. We also subjected mice to a forced treadmill test, and mice treated with R118 were able to maintain their run time as all other mice regressed throughout the study. Since exercise tests measure global performance, we also sought to obtain a more focused assessment of in vivo muscle function during exercise using sciatic nerve stimulation to measure plantar flexion torque. Listed in order of the size effect, exercise training, AMPK activation (R118), and cilostazol all significantly improved lower limb fatigue resistance.

There are many compelling reasons to explore the mechanism of AMPK activation in PAD, including its importance for muscle metabolism and mitochondrial function (17, 22, 70) and endothelial function through the regulatory control of eNOS (6, 8, 41, 74). The higher citrate synthase activity in skeletal muscle points to improved mitochondrial function with R118 treatment. This may be counterintuitive since acute dosing of R118 inhibits complex I. However, weak RNA interference of a complex I component demonstrates that skeletal muscles adapt to stress by increasing mitochondrial number and improving mitochondrial efficiency (45), a term known as mitohormesis. Other AMPK activators, such as exercise and AICAR, also improve mitochondrial function (17, 70), similar to the changes seen with R118. Exercise can also improve mitochondrial function, and in this study we saw comparable improvements in citrate synthase activity in wheel-trained mice but not in cilostazol-treated mice. These data suggest that improving mitochondrial function through AMPK activation may have a positive effect on walking time in patients with PAD.

The robust increases in skeletal muscle perfusion caused by AMPK activation, especially during exercise, stand out as one of the most striking findings of this study. This functional proof of improved perfusion was accompanied by anatomical evidence of increased small vessel density within hindlimb muscles, increased nitrate/nitrite, and decreased ADMA in plasma. Others have shown an important role for AMPK in arteriolar dilation (6, 13), but these assessments were not done in the context of overt disease, during exercise, or linked to functional performance. These improvements in microvascular function were not seen with cilostazol. Part of the improvement is exercise performance with AMPK activation may be related to the improvement in microvascular function of skeletal muscle. However, many systems affect exercise performance, and the relative amount of improvement in perfusion compared with exercise performance in exercise-trained mice suggest that additional physiological processes beyond AMPK activation and/or microvascular improvement contribute to exercise performance.

Preclinical animal models with relevancy to PAD present many challenges, and the limitations with current approaches have been widely commented upon (14, 75). While no single approach in animals can ever fully recapitulate the human condition, numerous aspects of functional measures, comorbidities, timescales, group sizes, controls, time of treatment (after onset of disease), and study design have been addressed here. These studies were well powered (18–36 animals/group) and included comparisons to molecules with clinical benefit (cilostazol) (58) or that have previously failed clinical trials assessing claudication (AT-1015) (23). Collectively, these data point to numerous functional and molecular overlaps between patients with PAD and aged, obese mice and highlight the therapeutic potential of AMPK activation for improving exercise tolerance in the context of underlying peripheral vascular insufficiency.

GRANTS

All research was funded by Rigel Pharmaceuticals Incorporated.

DISCLOSURES

All authors are employees and stockholders at Rigel Pharmaceuticals Incorporated.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.A.B., W. Li, S.J.S., D.G., R.S., V.M., D.L., G.P., Y.H., D.G.P., and T.M.K. conception and design of research; K.A.B., K.W., W. Li, M.D.C., W. Lang, R.A., B.K.S., A.M.F., J.M., D.H., K.M., H.N., I.J.S., G.G., S.J.S., D.G., V.M., T.-Q.S., Y.J., G.U., Y.L., A.P., T.G., and Y.H. performed experiments; K.A.B., B.K.S., J.M., D.H., H.N., V.M., T.-Q.S., and Y.H. analyzed data; K.A.B., V.M., Y.H., D.G.P., and T.M.K. interpreted results of experiments; K.A.B. and T.M.K. prepared figures; K.A.B. and T.M.K. drafted manuscript; K.A.B., K.W., W. Li, S.J.S., R.S., T.-Q.S., Y.J., Y.H., D.G.P., and T.M.K. edited and revised manuscript; K.A.B., K.W., W. Li, M.D.C., W. Lang, R.A., B.K.S., A.M.F., J.M., D.H., K.M., H.N., I.J.S., G.G., S.J.S., D.G., R.S., V.M., T.-Q.S., Y.J., G.U., Y.L., A.P., T.G., D.L., G.P., Y.H., D.G.P., and T.M.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Taisei Kinoshita, Rongxian Dong, Melissa Ho, Daniel Creger, Lisa Gross, Jason Romero, Arlana Franklin, Luke Boralsky, Bhushan Samant, and Rachel Basile for technical assistance, William Hiatt (University of Colorado-Denver) for critical insight and reading of the manuscript, and Esteban Matsuda and Peter Ganz (University of California-San Francisco/San Francisco General Hospital) for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrikopoulos S, Blair AR, Deluca N, Fam BC, Proietto J. Evaluating the glucose tolerance test in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1323–E1332, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer TA, Regensteiner JG, Brass EP, Hiatt WR. Oxygen uptake kinetics during exercise are slowed in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Appl Physiol 87: 809–816, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belin de Chantemele EJ, Mintz JD, Rainey WE, Stepp DW. Impact of leptin-mediated sympatho-activation on cardiovascular function in obese mice. Hypertension 58: 271–279, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat HK, Hiatt WR, Hoppel CL, Brass EP. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA injury in patients with unilateral peripheral arterial disease. Circulation 99: 807–812, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharya I, Mundy AL, Widmer CC, Kretz M, Barton M. Regional heterogeneity of functional changes in conduit arteries after high-fat diet. Obesity 16: 743–748, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley EA, Eringa EC, Stehouwer CD, Korstjens I, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Musters R, Sipkema P, Clark MG, Rattigan S. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside in the muscle microcirculation increases nitric oxide synthesis and microvascular perfusion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 1137–1142, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brass EP, Hiatt WR, Green S. Skeletal muscle metabolic changes in peripheral arterial disease contribute to exercise intolerance: a point-counterpoint discussion. Vasc Med 9: 293–301, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen ZP, Mitchelhill KI, Michell BJ, Stapleton D, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Witters LA, Power DA, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Kemp BE. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of endothelial NO synthase. FEBS Lett 443: 285–289, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coutinho T, Rooke TW, Kullo IJ. Arterial dysfunction and functional performance in patients with peripheral artery disease: a review. Vasc Med 16: 203–211, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Criqui MH, Fronek A, Barrett-Connor E, Klauber MR, Gabriel S, Goodman D. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in a defined population. Circulation 71: 510–515, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson EP, Coppey LJ, Calcutt NA, Oltman CL, Yorek MA. Diet-induced obesity in Sprague-Dawley rats causes microvascular and neural dysfunction. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 26: 306–318, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation 109: III27–32, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis BJ, Xie Z, Viollet B, Zou MH. Activation of the AMP-activated kinase by antidiabetes drug metformin stimulates nitric oxide synthesis in vivo by promoting the association of heat shock protein 90 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Diabetes 55: 496–505, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dragneva G, Korpisalo P, Yla-Herttuala S. Promoting blood vessel growth in ischemic diseases: challenges in translating preclinical potential into clinical success. Dis Models Mech 6: 312–322, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faber JE, Zhang H, Lassance-Soares RM, Prabhakar P, Najafi AH, Burnett MS, Epstein SE. Aging causes collateral rarefaction and increased severity of ischemic injury in multiple tissues. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 1748–1756, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinglass J, Brown JL, LoSasso A, Sohn MW, Manheim LM, Shah SJ, Pearce WH. Rates of lower-extremity amputation and arterial reconstruction in the United States, 1979 to 1996. Am J Public Health 89: 1222–1227, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fillmore N, Jacobs DL, Mills DB, Winder WW, Hancock CR. Chronic AMP-activated protein kinase activation and a high-fat diet have an additive effect on mitochondria in rat skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 109: 511–520, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner AW, Forrester L, Smith GV. Altered gait profile in subjects with peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med 6: 31–34, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner AW, Killewich LA. Lack of functional benefits following infrainguinal bypass in peripheral arterial occlusive disease patients. Vasc Med 6: 9–14, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Parker DE. Optimal exercise program length for patients with claudication. J Vasc Surg 55: 1346–1354, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goff D, Payan D, Singh R, Shaw S, Carroll D, Hitoshi Y. AMPK-Activating Heterocyclic Compounds and Methods for Using the Same, edited by Organization WIP San Francisco, CA: Rigel Pharmaceuticals, 2012 [Google Scholar]