Abstract

Objectives:

To review the use of non-hormonal pharmacotherapies in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) due to presumed benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Materials and Methods:

A search of the PUBMED database was conducted for the terms BPH, LUTS, bladder outlet obstruction, alpha-adrenoceptor blockers, anti-muscarinics, and phosphodiesterase-5-inhibitors.

Results:

Medical therapy has long been established as the accepted standard of care in the treatment of male LUTS. The aim of treatment is improvement in symptoms and quality of life whilst minimizing adverse effects. The agents most widely used as 1st line therapy are alpha-blockers (AB), as a standalone or in combination with 2 other classes of drug; 5-α reductase inhibitors and anti-muscarinics. AB have rapid efficacy, improving symptoms and flow rate in a matter of days, these effects are then maintained over time. AB do not impact on prostate size and do not prevent acute urinary retention or the need for surgery. Anti-mucarinics, alone or in combination with an AB are safe and efficacious in the treatment of bothersome storage symptoms associated with LUTS/BPH. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are an emerging treatment option that improve LUTS without improving flow rates.

Conclusions:

AB are the most well-established pharmacotherapy in the management of men with LUTS/BPH. The emergence of different classes of agent offers the opportunity to target underlying pathophysiologies driving symptoms and better individualize treatment.

Keywords: Alpha antagonists, antimuscarinics, efficacy, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, side effects, uroselectivity

INTRODUCTION

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is an extremely common pathological finding in men and exhibits an age-related increase in incidence.[1] It is the most frequent cause of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and a significant cause of decreased quality of life.[2,3] Histologically, there is an increase in both the cellular and stromal components of the prostate gland that may result in the reduction in the caliber of the urethral lumen and, as a consequence, obstruction to urine flow during voiding.[4] This is thought to result in voiding symptoms such as weak flow and intermittency.[5] Storage symptoms such as frequency, nocturia, and urgency also commonly occur and typically cause patients more bother. Symptom severity, which is only weakly correlated to prostatic size,[6,7] is likely to be partly attributable to the smooth muscle tone in the prostate and bladder neck which is under sympathetic control and mediated by the alpha-adrenoceptor (AR).[8]

In contemporary practice, the first line management of LUTS due to presumed BPH, termed LUTS/BPH, entails conservative measures and behavioral modification. Should this fail to significantly improve symptoms, pharmacotherapy is often commenced. In the 1990s, alpha-blockers (AB) were the first non-hormonal agent to gain widespread usage marking the beginning of a paradigm shift in the management of LUTS/BPH away from surgical therapies to drug therapy. More recently, evidence supporting the use of other classes of agents, such as the antimuscarinics (anti-M) and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors has emerged. We review the use of non-hormonal pharmacotherapy in the management of LUTS/BPH, describing the common agents and discuss the important considerations when prescribing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A search of the PUBMED database for original articles, reviews and editorials using the terms BPH, LUTS, bladder outlet obstruction, alpha-blockers, anti-muscarinics, and Phosphodiesterase-5-inhibitors was conducted. Retrieved abstracts were checked for relevance, before the articles were then selected for inclusion.

Alpha-blockers

AB are currently widely used as initial pharmacotherapy in the treatment of men with LUTS/BPH. They offer symptomatic relief whilst being generally well tolerated.[9] In BPH, the relative contribution of stromal to epithelial components can vary significantly, but in general is around 4:1. The stromal components are approximately 50% composed of smooth muscle elements, which is the target for the mechanism of action of AB. The alpha-AR was first implicated as mediator of prostate smooth muscle contraction in the work of Marco Caine and co-workers who demonstrated that strips of human prostate tissue contracted in response to norepinephrine.[10] This contraction was inhibited by pre-treating the tissues with phenoxybenzamine, a non-selective AB. Subsequently, the alpha-AR types (1 and 2) were characterized and the alpha-1 AR was determined to be the mediator of contraction.

Mechanism of action

The alpha-1 AR are G protein-coupled receptors. When norepinephrine and epinephrine bind to the receptor there is activation of phospholipase C leading to the release of secondary messengers inositol triphosphate and diacyglycerol. This results in mobilization of intracellular calcium and culminates in the contraction of smooth muscle.[11] In the neck of the human bladder, prostate, and urethra, it is the alpha-1a AR subtype that is most prevalent,[8] constituting two-thirds of alpha-1 receptors in normal prostates and up to 85% in prostates with BPH.[12,13] AB work through antagonism of alpha-1a AR leading to relaxation of prostatic smooth muscle thereby counteracting the dynamic component of BOO caused by BPH. The non-subtype selective AB display similar affinity for all the alpha-1 AR subtypes and consequently cause vasodilation secondary to blockade of the alpha 1b-adrenoceptors that are most common in large blood vessels.

Safety and efficacy

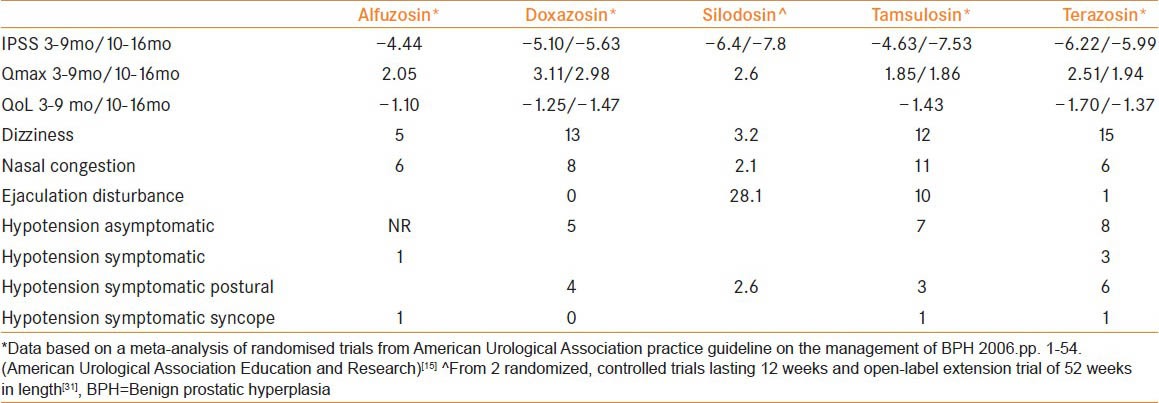

All the AB have similar efficacy with total symptom score in general improved by 30-40% and peak flow rates by 16-25%, but differ in terms of side effect profile[14,15] [Table 1]. We discuss the evolution of AB in the treatment LUTS/BPH.

Table 1.

Safety and efficacy data for current AB

Non-selective alpha-blockers

Phenoxybenzamine was the first AB shown to produce improvements in symptoms as well as flow rates in a randomized clinical trial.[16] There were however significant side effects due to the systemic antagonism of the alpha-AR including dizziness, hypotension, nasal congestion, and tiredness which limited its use.

Selective alpha-blockers

Prazazosin was the first alpha-1 AR selective agent used in LUTS/BPH and demonstrated a clear advantage over phenoxbenzamine in the side effect profile although it still had a significant impact upon blood pressure.[17] As it was short acting it, required dosing several times a day which was deemed a major limitation. Longer acting AB were then subsequently approved, firstly Terazosin then Doxazosin. Both agents demonstrated comparable efficacy in terms of symptom scores and flow rates.[18,19,20,21] All the pivotal studies with these two agents included a dose titration phase to avoid first dose efficacy and safety effects. Doxazosin has a longer half-life although this did not lead to any advantage in terms of tolerability or safety. Both agents caused a reduction in blood pressure only in those men who were on anti-hypertensives at baseline.[22,23] Alfuzosin is another alpha-1 AR selective agent which is available in a once a day slow release formulation. It has similar efficacy to the other AB with good tolerability[24,25] and its major advantage over the aforementioned agents is the lack of need for dose titration.

Subtype-selective alpha-blockers

Subtype selective agents have a greater affinity for the alpha-1a subtype over the other subtypes. They were developed on the basis that targeting the alpha-1a subtype would result in greater efficacy and less side effects than type specific agents. Tamsulosin was the first in class agent approved for LUTS/BPH. Experimentally, tamsulosin exhibited around a tenfold affinity for the alpha-1a to alpha-1b AR. The pivotal studies failed to demonstrate an efficacy advantage compared to other agents although there was a greater incidence of anejaculation noted.[26,27] This is often wrongly coded in clinical trials as retrograde ejaculation.[28] As with alfuzosin, a major advantage with this agent at the standard dose of 0.4 mg is the clinical efficacy without the need for dose titration.

Silodosin is a relatively newer AB with unparalleled selectivity for the alpha-1a AR over the alpha-1b AR.[29] In vitro studies showed that silodosin's alpha-1a: Alpha-1b binding ratio is in the order of 160:1.[29] Clinically, this has resulted in rapid and sustained efficacy, increased flow rates as well as improvements in quality of life scores, which are broadly comparable to tamsulosin.[30,31] Silodosin was found to have minimal risk of cardiovascular effects although it did have a greater risk of ejaculatory dysfunction than tamsulosin in direct comparisons, 14.2 to 22.3% versus 1.6-2.1%, respectively.[32,33]

Naftopidil is another AB, licensed for use only in Japan. It has a three-fold affinity for the alpha-1d over the alpha-1a receptor subtype. In prostate glands from men with BPH, a three-fold increase in alpha-1d expression compared to normal individuals is found and so it has been suggested that the alpa-1d receptor also contributes to prostatic smooth muscle contraction.[34] The alpha-1d receptor is also present in the detrusor muscle and lumbosacral spinal cord[35,36] where in animal studies it has been shown to play a role in facilitating the micturition reflex.[37] There is a lack of large well-designed randomized placebo controlled studies investigating safety and efficacy in men with BPH, furthermore naftopidil is yet to be studied in men from populations in other regions of the world.[38]

Anti-muscarinics

Anti-muscarinics (Anti-M) are the most common class of pharmacotherapy used in the overactive bladder syndrome (OAB). Traditionally, they have been considered to improve symptoms by reducing the frequency and strength of non-voluntary detrusor contractions (detrusor overactivity (DO)).[39] Classic teaching dictated that anti-M should be avoided in men with LUTS/BPH due to a high risk of causing acute urinary retention. Recently, this assertion has been challenged and anti-M have become an acceptable part of the armamentarium in LUTS/BPH.[40,41,42]

Basic mechanisms of storage LUTS in BPH/BOO

Whilst traditionally in men all LUTS were commonly attributed to the prostate, it is clear that the aetiology of LUTS and particular storage LUTS is wide. Storage LUTS in a proportion of individuals appear to be the result of BOO due to BPH as it can be seen that they resolve in around two-thirds of men after outflow surgery.[43] Whilst DO, which is strongly correlated with storage LUTS in men, resolves in a similar proportion of patients.[44] In these individuals, it was postulated that the bladder cholinergic receptors become hypersensitive as a consequence of denervation secondary to obstruction.[45] The exact mechanism of storage LUTS/OAB in men who do not have obstruction or in those whom symptoms continue after relief of BOO, remain the subject of academic discourse, the putative mechanisms have been discussed in detail elsewhere.[46]

Mechanism of action

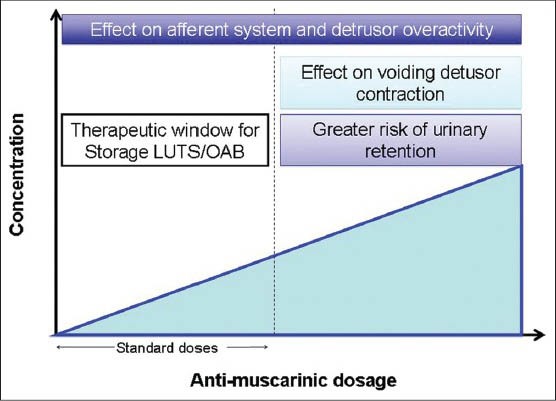

There are five known subtypes of muscarinic receptor distributed in the body (e.g.salivary gland M1/M3, gut M2/M3, brain M1 and cardiovascular system M2). In the bladder the M2 receptors are most numerous (75%) although it is the M3 receptors (25%) that are functionally important for detrusor contraction. Anti-M are traditionally viewed as exerting their effects on storage LUTS/OAB by blocking the post-junctional M3 receptors stopping the excitation−contraction coupling in the detrusor muscle.[47] This view has been challenged with the observation that in usual doses, there is no impairment of patients ability to empty their bladders whilst many derive symptomatic improvement. It is only at much higher doses that voiding efficiency is significantly affected [Figure 1]. The finding of muscarinic receptors in the urothelium and suburothelium as well as the afferent nerves suggest the possibility that anti-M may work through a sensory mechanism and correlates well with the clinical finding that patients who do not demonstrate DO on a urodynamic study often experience improvement in symptoms with anti-M. A direct action upon the prostate itself is also possible as cholinergic nerves innervate the prostatic glands and stroma.[48] Muscarinic receptors are also associated with prostatic epithelial cells suggesting a possible a role in glandular growth or function.[49]

Figure 1.

At standard doses there is a therapeutic effect without impairment of voiding contraction whilst at higher doses voiding contraction is impaired and there is an increased risk of urinary retent ion

Safety and efficacy

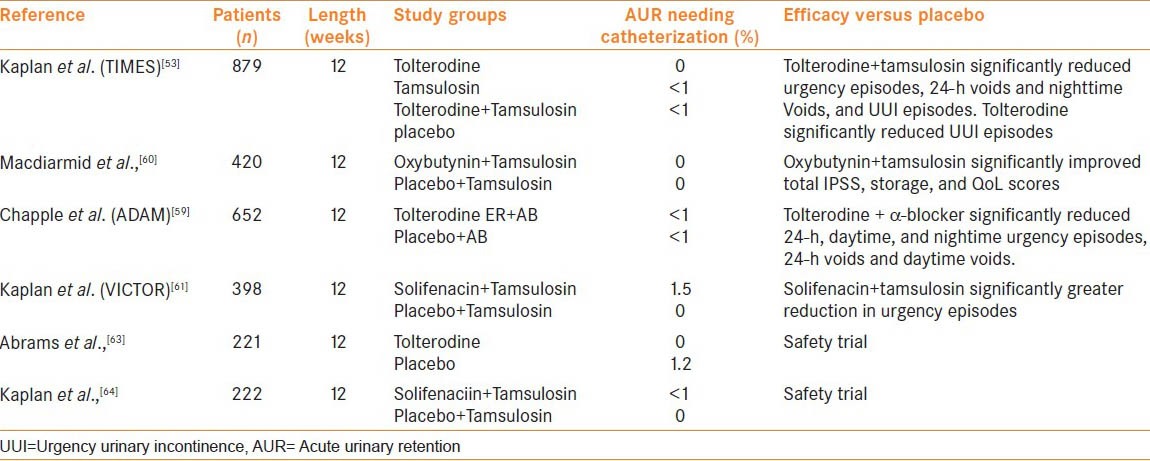

A multitude of randomized controlled trials investigating the use of several different anti-M agents in men with LUTS/BPH and men with proven BOO have been published and the results summarized in several systematic reviews.[50,51,52] The key studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key 12 week randomized placebo controlled studies investigating efficacy and/or safety of anti-M for male LUTS

The ‘Tolterodine and tamsulosin in men with LUTS including OAB: Evaluation and efficacy study’, known as the TIMES study, was a large 12 week randomized study that assessed tolterodine ER (4 mg) against tamsulosin (0.4mg) and combination therapy with tamsulosin (0.4 mg) and tolterodine ER (4 mg) or placebo.[53] The study excluded patients with evidence of bladder outlet obstruction (based on low flow rate and PVR > 200 ml). Tolterodine reduced urgency urinary incontinence episodes versus placebo but no other parameters whereas combination treatment reduced IPSS total and storage sub-scores as well as bladder diary variables. Urinary retention was uncommon and occurred to a similar extent in all groups; 0.5, 0, 0.4, and 0% for the tolterodine, tamsulosin, combination and placebo groups, respectively. In terms of Qmax, there was no difference of significance between the groups. In a post hoc analyses that stratified men by prostate volume, smaller prostatic volume (vol <30 ml and PSA <1.3 ng/ml) was associated with greater improvements in several bladder diary variables and IPSS storage sub-scores than in men with larger prostates (vol >30 ml and PSA >1.3 ng/ml).[54,55]

Tolterodine on its own was comparatively less effective which is in variance to other reports which show good efficacy for anti-M treatment in men with storage LUTS/OAB.[56,57,58] This is potentially attributable to the characteristics of the study population who had relatively high IPSS scores at entry (19.5−20.6) and had to have features of LUTS/BPH and OAB for entry and so the pathophysiology of symptoms in a greater proportion of these patients may be purely prostate driven and not expected to respond as well to an anti-M alone. Sequential therapy with tolterodine after failure of an AB alone to improve symptoms has also been studied in a randomized trial setting and found to be safe and efficacious.[59] Other anti-M that have demonstrated safety and efficacy in men in large clinical trials include oxybutynin (in combination with tamsulosin),[60] solifenacin (in combination with tamsulosin)[61] and fesoterodine (after failure of AB to improve symptoms).[62]

In order to determine whether anti-M are safe in men with urodynamically proven BOO, tolterodine 2 mg BD was studied in a small randomized trial in men >40 years with confirmed BOO and DO.[63] Patients underwent pressure flow studies at baseline and were then randomized to tolterodine or placebo before the pressure flow studies were repeated at 12 weeks. No significant difference in maximal flow rates and detrusor voiding pressure at maximal flow was observed between the groups. There was a marginal but significant increase in PVR and similar reduction in bladder contractility index for tolterodine compared to placebo, 25 ml vs. 0 ml (P ≤ 0.004) and −5 vs. +5 (P = 0.0045), respectively. Only one patient developed urinary retention who was in the placebo group. Similar findings were seen in a recent 12 week study assessing combination of tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system with solifenacin 6 mg or 9 mg with urodynamic BOO.[64]

There is dearth of studies investigating the comparative efficacy of anti-M in men. Once small study (total 107 subjects) compared tolterodine, solifenacin, and darifenacin.[65] Whilst the three agents all reduced the total number of voids and IPSS score, tolterodine, and solifenacin had an advantage over darifenacin. Darifenacin also showed the greatest increase in PVR (+16.2 ml, P < 0.001) and was associated with greatest incidences of urinary retention (56%) and constipation. There is a need for larger studies comparing agents in this group of patients.

In term of assessing safety a major limitation with these studies are that they excluded men with larger PVRs and low flow rates who would have a comparatively higher risk of developing urinary retention. In addition where prostate volume was measured this was generally low and studies were mostly 12 weeks in duration, which is arguably not long enough to gauge the true risk of developing urinary retention. For these reasons anti-M are not recommended in men with a raised PVR >200 ml, low peak flow rates or who have larger prostates or a prior history of urinary retention.

Phosphodiesterase-5-Inhibitors

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a strong and consistent relationship between LUTS/BPH and erectile dysfunction (ED).[66] Several hypotheses for a common pathway in the pathogenesis of LUTS and ED have been proposed such as a change in the NO-cGMP pathway, RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling, increased autonomic adrenergic activity, and pelvic ischemia due to atherosclerosis.[67] PDE5 inhibitors are an established treatment for ED and their potential as a therapy for LUTS/BPH has attracted great interest. The rationale for their use is to improve LUTS and any coexistent sexual dysfunction, whether pre-existent or consequent upon therapy taken for LUTS/BPH such as a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor.

Mechanism

PDE5 is expressed in the prostatic urethra, prostate and bladder neck,[68] and supplying blood vessels.[68] Experimental studies have shown PDE5 inhibitors cause relaxation of detrusor, prostate and pelvic vasculature muscle strips[69] through regulating cGMP breakdown and enhancing the NO/cGMP signaling pathway. Other possible mechanism maybe through improved pelvic oxygenation or an effect on the afferent nerves or alternatively by reducing prostatic inflammation.[70]

Safety and efficacy

A few early proof of concept studies demonstrated the potential benefit of sildenafil in men with LUTS with ED when taken on an as needed basis.[71,72] The positive effect of sildenafil was attributed to smooth muscle relaxation. These studies were open label, non-randomized and not placebo controlled. More substantive evidence was provided by a series of randomized clinical studies that assessed daily dosing with three different PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil, vardenafil, tadalafil) inhibitors alone or in combination with and AB. Gacci et al. have recently summarized the results of these studies in a systematic review and meta-analysis. In total, seven RCTs assessing the efficacy of monotherapy with PDE5 inhibitors in men with LUTS/BPH were included. The analysis demonstrated significant improvements in IPSS score (−2.8, P < 0.0001) in comparison to placebo with no improvement in flow rate.[73] In terms of safety most treatment related adverse events were mild to moderate and seldom led to discontinuation of therapy. Flushing, gastroesophageal reflux, headache, and dyspepsia all occurred more frequently with PDE5 inhibitors.

In five relatively smaller studies, combination therapy with an AB was assessed.[73] In terms of total IPSS, combination therapy significantly improved scores to a greater extent than AB alone (−1.8 P = 0.05). Interestingly, in terms of flow rate a significant benefit for combination treatment versus AB alone was evident (1.5 ml/s [+0.9 to + 2.2]; P < 0.0001). The authors postulated that the additional benefit in flow rate, not seen with PDE5 inhibitors alone, maybe explained by relaxation of the bladder counteracting any effect from relaxation of prostate smooth muscle. In terms of safety, adverse event rate was similar between the two groups, 6.8% with combination treatment and 5.1% with AB alone.

Approach to selecting non-hormonal pharmacotherapy in male LUTS

Men with LUTS/BPH represent a heterogeneous group of patients in terms of age, co-morbidities, concomitant medications, and sexual activity. All of these factors have major implications with regards to the suitability and tolerability of medical therapy and must be carefully considered in selecting which therapy is appropriate for which patient.

PVR

Anti-M as monotherapy or in combination with AB are currently recommended for use in men with LUTS/BPH with predominant storage LUTS in both the American urology association (AUA)[74] and European association of urology (EAU) guidelines.[75] The AUA guidelines recommend that PVR is checked before the initiation of therapy and that anti-M be used with caution in men with PVR >250-300 ml whilst the EAU guideline recommends caution when used in men with BOO. The EAU treatment algorithm provides the option of anti-M monotherapy in men with storage LUTS/OAB only, whilst in those with co-existent voiding LUTS an AB is recommended initially, typically for a period of 4-6 weeks, after which an anti-M is an option in men with residual storage LUTS/OAB. Monitoring of PVR within the first month of treatment using bladder ultrasound is advisable.

Age

BPH can affect men as early as the 4th decade and usually progresses with age, hence patients may range from those who are young, fit and active to those who are elderly, frail and poorly mobile. Orthostatic hypotension is a common problem associated with old age and can occur in the absence of frank cardiovascular disease. As such medications that may affect blood pressure may exacerbate this problem leading to dizziness, falls, and fall related morbidity. Non-selective AB certainly fall into this category due to associated antagonism of alpha 1b receptors in the vascular system and so need to be used with caution in more elderly men. Similarly, age is an important consideration when prescribing anti-M, due to the propensity of these agents to cause confusion in the elderly as well as constipation.

Co-morbidities and concomitant medications

LUTS/BPH often occurs in the context of common, age-related co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and erectile dysfunction. Medication taken for these conditions may potentially interact adversely with LUTS/BPH therapy. A common example of this is the addition of an alpha-blocker in the context of concomitant antihypertensive treatment leading to a pronounced hypotensive effect. There is potential for a similar scenario to occur in patients receiving PDE5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction and there is a need for this to be investigated in future studies. Anti-M use is contraindicated in a variety of medical conditions that occur in the elderly males such as narrow-angle glaucoma and intestinal atony. Hence, a careful history and assessment of current medication is essential.

Sexual function

Sexual dysfunction is a recognized side effect of treatment with alpha-blockers usually in the form of ejaculatory dysfunction which is a collective term to describe reduced semen quantity, reduced semen force or no semen associated with orgasm. These are thought to occur due to alpha-1a AR mediated inhibition of the ejaculatory apparatus rather than a deficiency in sperm function or number and the effect is reversed within days of stopping treatment.[76] Such problems of sexual function may not be a hindrance to the older male but clearly are likely to concern younger men who are more likely to be sexually active. Even so it may be the case that some men are willing to tolerate such problems as an acceptable “trade off” for improvements in bothersome LUTS that drug therapy may provide. PDE5 inhibitors offer the possibility of simultaneously treating LUTS and ED.

Tolerability

Poor adherence and persistence are common problems with anti-M. The proportion of patients still on their original medication at 1 year ranges from 14 to 35% for different agents in common use.[77] The problem stems from a lack of perceived efficacy or the inability to tolerate side effects. Common side effects include dry mouth, constipation, tiredness, blurred vision as well as cognitive impairment which the elderly are at particular risk from. In real clinical practice, if a patient fails to gain symptomatic improvement or is unable to tolerate side effects, a different anti-M agent is often trialed although there is no strong evidence for differential efficacy across agents.

CONCLUSIONS

In 2014, there are a variety of non-hormonal pharmacological agents that can be used alone or in combination to target the pathophysiologies driving the symptoms of men with LUTS/BPH. Sub-type selective AB offer the opportunity to relieve LUTS and improve flow rates with minimal cardiovascular side effects. This comes at the cost of a relatively higher incidence of ejaculatory dysfunction which may make them better suited to older individuals or those who are not sexually active. Type selective AB may be a more appropriate option in younger and sexually active individuals. Anti-M agents are now considered safe and efficacious in the treatment of storage LUTS which are typically most bothersome for patients. There is a need for further studies to understand the long-term risk of urinary retention beyond 3 months and better define the safe upper limit in terms of PVR. PDE5 inhibitors offer the potential to simultaneously treat both LUTS/BPH and ED. They have demonstrated efficacy without simultaneously improving flow rates suggesting they do not work by ameliorating BOO. Their place in treatment algorithms is yet to be established.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol. 1984;132:474–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welch G, Weinger K, Barry MJ. Quality-of-life impact of lower urinary tract symptom severity: Results from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Urology. 2002;59:245–50. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons JK. Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2010;5:212–8. doi: 10.1007/s11884-010-0067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapple C. Medical treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia. BMJ. 1992;304:1198–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6836.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clifford GM, Farmer RD. Medical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: A review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2000;38:2–19. doi: 10.1159/000020246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry MJ, Cockett AT, Holtgrewe HL, McConnell JD, Sihelnik SA, Winfield HN. Relationship of symptoms of prostatism to commonly used physiological and anatomical measures of the severity of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1993;150:351–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chute CG, Panser LA, Girman CJ, Oesterling JE, Guess HA, Jacobsen SJ, et al. The prevalence of prostatism: A population-based survey of urinary symptoms. J Urol. 1993;150:85–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson KE, Lepor H, Wyllie MG. Prostatic alpha 1-adrenoceptors and uroselectivity. Prostate. 1997;30:202–15. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970215)30:3<202::aid-pros9>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, Andriole GL, Jr, Dixon CM, Kusek JW, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caine M, Raz S, Zeigler M. Adrenergic and cholinergic receptors in the human prostate, prostatic capsule and bladder neck. Br J Urol. 1975;47:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1975.tb03947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawrylyshyn KA, Michelotti GA, Coge F, Guenin SP, Schwinn DA. Update on human alpha1-adrenoceptor subtype signaling and genomic organization. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:449–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwinn DA. The role of alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in lower urinary tract symptoms. BJU Int. 2001;88(Suppl 2):27–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00116.x. discussion 49-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawabe K. Current status of research on prostate-selective alpha 1-antagonists. Br J Urol. 1998;81(Suppl 1):48–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.0810s1048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djavan B, Marberger M. A meta-analysis on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 1999;36:1–13. doi: 10.1159/000019919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American urological association practice guideline on the Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: American Urological Association Education and Research. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caine M, Perlberg S, Meretyk S. A placebo-controlled double-blind study of the effect of phenoxybenzamine in benign prostatic obstruction. Br J Urol. 1978;50:551–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1978.tb06210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirby RS, Coppinger SW, Corcoran MO, Chapple CR, Flannigan M, Milroy EJ. Prazosin in the treatment of prostatic obstruction. A placebo-controlled study. Br J Urol. 1987;60:136–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1987.tb04950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepor H, Auerbach S, Puras-Baez A, Narayan P, Soloway M, Lowe F, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of terazosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1992;148:1467–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lloyd SN, Buckley JF, Chilton CP, Ibrahim I, Kaisary AV, Kirk D. Terazosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A multicentre, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Urol. 1992;70(Suppl 1):17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1992.tb15862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fawzy A, Braun K, Lewis GP, Gaffney M, Ice K, Dias N. Doxazosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in normotensive patients: A multicenter study. J Urol. 1995;154:105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillenwater JY, Conn RL, Chrysant SG, Roy J, Gaffney M, Ice K, et al. Doxazosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response multicenter study. J Urol. 1995;154:110–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirby RS. Doxazosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Effects on blood pressure and urinary flow in normotensive and hypertensive men. Urology. 1995;46:182–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirby RS. Terazosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Effects on blood pressure in normotensive and hypertensive men. Br J Urol. 1998;82:373–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Kerrebroeck P, Jardin A, Laval KU, van Cangh P. Efficacy and safety of a new prolonged release formulation of alfuzosin 10 mg once daily versus alfuzosin 2.5 mg thrice daily and placebo in patients with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. ALFORTI Study Group. Eur Urol. 2000;37:306–13. doi: 10.1159/000052361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roehrborn CG. Efficacy and safety of once-daily alfuzosin in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Urology. 2001 Dec;58:953–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lepor H. Phase III multicenter placebo-controlled study of tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Tamsulosin Investigator Group. Urology. 1998;51:892–900. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narayan P, Tewari A. A second phase III multicenter placebo controlled study of 2 dosages of modified release tamsulosin in patients with symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. United States 93-01 Study Group. J Urol. 1998;160:1701–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hellstrom WJ, Sikka SC. Effects of acute treatment with tamsulosin versus alfuzosin on ejaculatory function in normal volunteers. J Urol. 2006;176:1529–33. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tatemichi S, Kobayashi K, Maezawa A, Kobayashi M, Yamazaki Y, Shibata N. [Alpha1-adrenoceptor subtype selectivity and organ specificity of silodosin (KMD-3213)] Yakugaku Zasshi. 2006:126. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.126.209. Spec no:209-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osman NI, Chapple CR, Cruz F, Desgrandchamps F, Llorente C, Montorsi F. Silodosin: A new subtype selective alpha-1 antagonist for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:2085–96. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.714368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marks LS, Gittelman MC, Hill LA, Volinn W, Hoel G. Rapid efficacy of the highly selective alpha1A-adrenoceptor antagonist silodosin in men with signs and symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia: Pooled results of 2 phase 3 studies. J Urol. 2009;181:2634–40. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapple CR, Montorsi F, Tammela TL, Wirth M, Koldewijn E, Fernandez Fernandez E. Silodosin therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms in men with suspected benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results of an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled clinical trial performed in Europe. Eur Urol. 2011;59:342–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawabe K, Yoshida M, Homma Y. Silodosin, a new alpha1A-adrenoceptor-selective antagonist for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results of a phase III randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study in Japanese men. BJU Int. 2006;98:1019–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nasu K, Moriyama N, Kawabe K, Tsujimoto G, Murai M, Tanaka T, et al. Quantification and distribution of alpha 1-adrenoceptor subtype mRNAs in human prostate: Comparison of benign hypertrophied tissue and non-hypertrophied tissue. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:797–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malloy BJ, Price DT, Price RR, Bienstock AM, Dole MK, Funk BL, et al. Alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human detrusor. J Urol. 1998;160:937–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith MS, Schambra UB, Wilson KH, Page SO, Schwinn DA. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors in human spinal cord: Specific localized expression of mRNA encoding alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes at four distinct levels. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;63:254–61. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishihama H, Momota Y, Yanase H, Wang X, de Groat WC, Kawatani M. Activation of alpha1D adrenergic receptors in the rat urothelium facilitates the micturition reflex. J Urol. 2006;175:358–64. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hara N, Mizusawa T, Obara K, Takahashi K. The role of naftopidil in the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Ther Adv Urol. 2013;5:111–9. doi: 10.1177/1756287212461681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abrams P, Andersson KE. Muscarinic receptor antagonists for overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2007;100:987–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chapple CR, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, Muston D, Bitoun CE, Weinstein D. The effects of antimuscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: An update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2008;54:543–62. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaplan SA, Walmsley K, Te AE. Tolterodine extended release attenuates lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2005;174:2273–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181823.33224.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Novara G, Galfano A, Ficarra V, Artibani W. Anticholinergic drugs in patients with bladder outlet obstruction and lower urinary tract symptoms: A systematic review. Eur Urol. 2006;50:675–83. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abrams PH, Farrar DJ, Turner-Warwick RT, Whiteside CG, Feneley RC. The results of prostatectomy: A symptomatic and urodynamic analysis of 152 patients. J Urol. 1979;121:640–2. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56918-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Machino R, Kakizaki H, Ameda K, Shibata T, Tanaka H, Matsuura S, et al. Detrusor instability with equivocal obstruction: A predictor of unfavorable symptomatic outcomes after transurethral prostatectomy. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:444–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Speakman MJ, Brading AF, Gilpin CJ, Dixon JS, Gilpin SA, Gosling JA. Bladder outflow obstruction-a cause of denervation supersensitivity. J Urol. 1987;138:1461–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roosen A, Chapple CR, Dmochowski RR, Fowler CJ, Gratzke C, Roehrborn CG, et al. A refocus on the bladder as the originator of storage lower urinary tract symptoms: A systematic review of the latest literature. Eur Urol. 2009;56:810–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersson KE, Yoshida M. Antimuscarinics and the overactive detrusor-which is the main mechanism of action? Eur Urol. 2003;43:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ventura S, Pennefather J, Mitchelson F. Cholinergic innervation and function in the prostate gland. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;94:93–112. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witte LP, Chapple CR, de la Rosette JJ, Michel MC. Cholinergic innervation and muscarinic receptors in the human prostate. Eur Urol. 2008;54:326–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Abrams P, Chapple CR, Bavendam T, Guan Z. Antimuscarinics for treatment of storage lower urinary tract symptoms in men: A systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:487–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Athanasopoulos A, Chapple C, Fowler C, Gratzke C, Kaplan S, Stief C, et al. The role of antimuscarinics in the management of men with symptoms of overactive bladder associated with concomitant bladder outlet obstruction: An update. Eur Urol. 2011;60:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blake-James BT, Rashidian A, Ikeda Y, Emberton M. The role of anticholinergics in men with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2007;99:85–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, Carlsson M, Bavendam T, Guan Z. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2319–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roehrborn CG, Kaplan SA, Jones JS, Wang JT, Bavendam T, Guan Z. Tolterodine extended release with or without tamsulosin in men with lower urinary tract symptoms including overactive bladder symptoms: Effects of prostate size. Eur Urol. 2009;55:472–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roehrborn CG, Kaplan SA, Kraus SR, Wang JT, Bavendam T, Guan Z. Effects of serum PSA on efficacy of tolterodine extended release with or without tamsulosin in men with LUTS, including OAB. Urology. 2008;72:1061–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Dmochowski R, Rovner ES, Wang JT, Guan Z. Tolterodine extended release improves overactive bladder symptoms in men with overactive bladder and nocturia. Urology. 2006;68:328–32. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaplan SA, Goldfischer ER, Steers WD, Gittelman M, Andoh M, Forero-Schwanhaeuser S. Solifenacin treatment in men with overactive bladder: Effects on symptoms and patient-reported outcomes. Aging Male. 2010;13:100–7. doi: 10.3109/13685530903440408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roehrborn CG, Abrams P, Rovner ES, Kaplan SA, Herschorn S, Guan Z. Efficacy and tolerability of tolterodine extended-release in men with overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. BJU Int. 2006;97:1003–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chapple C, Herschorn S, Abrams P, Sun F, Brodsky M, Guan Z. Tolterodine treatment improves storage symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder in men treated with alpha-blockers. Eur Urol. 2009;56:534–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacDiarmid SA, Peters KM, Chen A, Armstrong RB, Orman C, Aquilina JW, et al. Efficacy and safety of extended-release oxybutynin in combination with tamsulosin for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2008;83:1002–10. doi: 10.4065/83.9.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaplan SA, McCammon K, Fincher R, Fakhoury A, He W. Safety and tolerability of solifenacin add-on therapy to alpha-blocker treated men with residual urgency and frequency. J Urol. 2009;182:2825–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Gong J, Sun F, Guan Z. Add-on fesoterodine for residual storage symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder in men receiving alpha-blocker treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms. BJU Int. 2012;109:1831–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abrams P, Kaplan S, De Koning Gans HJ, Millard R. Safety and tolerability of tolterodine for the treatment of overactive bladder in men with bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2006;175:999–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaplan SA, He W, Koltun WD, Cummings J, Schneider T, Fakhoury A. Solifenacin Plus Tamsulosin Combination Treatment in Men With Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Bladder Outlet Obstruction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur Urol. 2012;63:158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaplan SA, Zoltan E, Te AE. Safety and efficacy of tolterodine, solifenacin, and darifenacin in men with lower urinary tract symptoms on alpha-blockers with persistent overactive bladder symptoms (OAB) Abstract 2036. J Urol. 2008;179:701. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gacci M, Eardley I, Giuliano F, Hatzichristou D, Kaplan SA, Maggi M, et al. Critical analysis of the relationship between sexual dysfunctions and lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2011;60:809–25. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McVary K. Lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual dysfunction: Epidemiology and pathophysiology. BJU Int. 2006;97(Suppl 2):23–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06102.x. discussion 44-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fibbi B, Morelli A, Vignozzi L, Filippi S, Chavalmane A, De Vita G, et al. Characterization of phosphodiesterase type 5 expression and functional activity in the human male lower urinary tract. J Sex Med. 2010;7:59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giuliano F, Uckert S, Maggi M, Birder L, Kissel J, Viktrup L. The Mechanism of Action of Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Related to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2013;63:506–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vignozzi L, Gacci M, Cellai I, Morelli A, Maneschi E, Comeglio P, et al. PDE5 inhibitors blunt inflammation in human BPH: A potential mechanism of action for PDE5 inhibitors in LUTS. Prostate. 2013;73:1391–402. doi: 10.1002/pros.22686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sairam K, Kulinskaya E, McNicholas TA, Boustead GB, Hanbury DC. Sildenafil influences lower urinary tract symptoms. BJU Int. 2002;90:836–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mulhall JP, Guhring P, Parker M, Hopps C. Assessment of the impact of sildenafil citrate on lower urinary tract symptoms in men with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2006;3:662–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gacci M, Corona G, Salvi M, Vignozzi L, McVary KT, Kaplan SA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors alone or in combination with alpha-blockers for lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2012;61:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Avins AL, Barry MJ, Bruskewitz RC, Donnell RF, et al. Update on AUA guideline on the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2011;185:1793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. 2012. [Last accessed Jul 2013]. Available from: http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/12_Male_LUTS_LR May 9th 2012.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Giuliano F. Impact of medical treatments for benign prostatic hyperplasia on sexual function. BJU Int. 2006;97(Suppl 2):34–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06104.x. discussion 44-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, Siddiqui E. Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: A UK experience. BJU Int. 2012;110:1767–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]