Abstract

Accidental or intentional cyanide poisoning is a serious health risk. The current suite of FDA approved antidotes, including hydroxocobalamin, sodium nitrite, and sodium thiosulfate is effective, but each antidote has specific major limitations, such as large effective dosage or delayed onset of action. Therefore, next generation cyanide antidotes are being investigated to mitigate these limitations. One such antidote, 3-mercaptopyruvate (3-MP), detoxifies cyanide by acting as a sulfur donor to convert cyanide into thiocyanate, a relatively nontoxic cyanide metabolite. An analytical method capable of detecting 3-MP in biological fluids is essential for the development of 3-MP as a potential antidote. Therefore, a high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS-MS) method was established to analyze 3-MP from rabbit plasma. Sample preparation consisted of spiking the plasma with an internal standard (13C3-3-MP), precipitation of plasma proteins, and reaction with monobromobimane to inhibit the characteristic dimerization of 3-MP. The method produced a limit of detection of 0.1 µM, a linear dynamic range of 0.5–100 µM, along with excellent linearity (R2 ≥ 0.999), accuracy (±9% of the nominal concentration) and precision (<7% relative standard deviation). The optimized HPLC-MS-MS method was capable of detecting 3-MP in rabbits that were administered sulfanegen, a prodrug of 3-MP, following cyanide exposure. Considering the excellent performance of this method, it will be utilized for further investigations of this promising cyanide antidote.

Keywords: Cyanide antidote, 3-Mercaptopyruvate, Sulfanegen, Liquid chromatography-tandem mass, spectrometry

1. Introduction

Humans are exposed to cyanide (LD50, human = 1.1 mg/kg) [1,2] in a variety of ways, such as ingestion of some edible plants (spinach or cassava), industrial operations, smoke inhalation from fires and/or cigarettes, and terrorist activities [3,4]. Once cyanide is absorbed, it inhibits the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase in the electron transport system, thereby disrupting aerobic metabolism. There are currently three U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved cyanide treatments: hydroxocobalamin, sodium nitrite, and sodium thiosulfate [2,5–7].

Hydroxocobalamin (vitamin B12a) is a large molecular-weight cyanide antidote that detoxifies cyanide by sequestration. It forms a very strong bond with cyanide because of the high affinity of cyanide for the central cobalt atom (KA ≈ 1012M−1) [8]. Cyanide binds to cobalt to produce cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) [9–11], which resides in the plasma and is excreted in urine. The potential adverse effects of hydroxocobalamin are generally mild and include elevated blood pressure, decreased heart rate, rashes, and red coloring of the skin, tears, urine and sweat [12,13]. The recommended dose of hydroxocobalamin is 5 g (administered over 15 min). Because of the high dose needed for optimum therapeutic effect, hydroxocobalamin must be administered intravenously [2,14], limiting the applicability of hydroxocobalamin in mass casualty situations.

Similar to hydroxocobalamin, the mechanism of action of sodium nitrite is to sequester cyanide from cytochrome c oxidase. However, the sequestration of cyanide is indirect. Sodium nitrite causes the conversion of hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which has a high affinity towards cyanide [14,15]. Recently, another mechanism of action of sodium nitrite was proposed as the prominent method of detoxification in which nitrite is converted to nitric oxide, which subsequently displaces cyanide bound to the active site of cytochrome c oxidase [16,17]. Although sodium nitrite works well to detoxify cyanide, it is toxic at large concentrations [5,18] and has a small therapeutic window. Sodium nitrite is especially toxic when smoke inhalation has occurred, due to the conversion of hemoglobin to methemoglobin, which reduces the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood [18]. Due to its limited therapeutic efficacy, sodium nitrite is typically administered in tandem with sodium thiosulfate.

Sodium thiosulfate detoxifies cyanide by donating a sulfur to convert cyanide to the much less toxic thiocyanate [18–20]. Therefore, sodium thiosulfate belongs to a class of cyanide therapeutics known as sulfur donors, which utilize sulfurtransferase enzymes as catalysts. Sodium thiosulfate utilizes rhodanese, which is mainly found in the liver and kidneys [14,19], leaving the heart and central nervous system less protected and the main locations of cyanide toxicity [14]. It also has a slow onset of action, attributed to slow entry into cells and the mitochondria [5]. This necessitates its use in combination with faster acting therapeutics, typically sodium nitrite.

Considering that current cyanide antidotes each have major limitations, alternative cyanide antidotes are being investigated [5,8,21]. One such alternate antidote is 3-mercaptopyruvate (3-MP). Similar to sodium thiosulfate, 3-MP acts as a sulfur donor to produce thiocyanate but is instead catalyzed by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) [19,21,22]. Sulfanegen, a prodrug of 3-MP (i.e., sulfanegen converts to 3-MP upon administration), has been found to be highly effective in reversing cyanide toxicity [14,20,21,23,24]. Although a method for the detection of 3-MP by HPLC from mouse tissue has been proposed [25], a multistep, lengthy (>60 min), and high temperature (95 ° C) modification of 3-MP is necessary. Therefore, the objective of this study was to develop a simple and sensitive analytical method for the analysis of 3-MP from rabbit plasma to facilitate further development of 3-MP as a cyanide antidote.

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and standards

All solvents were LC–MS grade unless otherwise noted. Ammonium formate and 3-mercaptopyruvate (3-MP; HSCH2COCOOH) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Acetone (HPLC grade, 99.5%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). Isotopically-labeled 3-MP (HS13CH213CO13COOH) was synthesized and provided by the Center for Drug Design, University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, MN, USA) [21]. Millex tetrafluoropolyethylene syringe filters (0.22 µm, 4 mm, Billerica, MA, USA) were obtained through Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Monobromobimane (MBB) was obtained from Fluka Analytical (Buchs, Switzerland) and a standard solution (500 µM) was prepared in LC–MS grade water and stored at 4 °C. 3-MP calibration standards and quality controls (QCs) were prepared from a 5 mM stock solution by serial dilution with rabbit plasma. The internal standard solution was prepared from a stock solution of 1 mM isotopically-labeled 3-MP in LC–MS grade water and stored at 4 °C.

2.2. Biological fluids

Rabbit plasma was obtained from two sources, a commercial vendor and a study used to evaluate effectiveness of sulfanegen in cyanide-exposed rabbits. For method development and validation, rabbit plasma (EDTA anti-coagulated) was purchased from Pel-Freeze Biological (Rogers, AR, USA) and stored at −80 °C until used. Rabbit plasma from sulfanegen efficacy studies was gathered at the Beckman Laser Institute at the University of California-Irvine. Rabbits were intramuscularly anesthetized, intubated and placed on isoflurane. Cyanide was administered at 0.47 mg/min intravenously until apnea (13 min), sulfanegen deanol (0.4 mmol) was then administered intraosseoussly at apnea. Blood was drawn from the rabbits at baseline (i.e., before cyanide exposure), 5 min after the start of cyanide infusion, at apnea, then 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 and 30 min after apnea. Blood was drawn into heparin collection tubes and plasma was immediately separated from blood. Plasma samples were then shipped on dry ice to South Dakota State University for analysis. Upon arrival, the plasma samples were stored at −80 °C until analyzed.

2.3. Sample preparation

Plasma (100 µL, 3-MP spiked or nonspiked) was added to a 2 mL centrifuge tube along with an internal standard (100 µL of 15 µM 3-MP-13C3). Protein from the plasma was precipitated by addition of acetone (300 µL) and the samples were cold-centrifuged (Thermo Scientific Legend Micro 21R centrifuge, Waltham, MA, USA) at 8 °C for 30 min at 13,100 rpm (16,500 × g). An aliquot (100 µL) of the supernatant was then transferred into a 4 mL glass vial and dried under N2. (Note: Glass vials were used in our laboratory mainly because of practical limitations of the N2 drier.) The samples were reconstituted with 5 mM ammonium formate in 9:1 water:methanol (100 µL). Underivatized 3-MP initially produced unacceptable chromatographic behavior under all conditions evaluated because of the characteristic dimerization of 3-MP [26–;28]. Therefore, MBB (100 µL, 500 µM) was added to prohibit 3-MP dimerization by converting the thiol group, which is necessary for dimerization, to a sulfide. The samples were heated on a block heater (VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA) at 70 °C for 15 min to produce a 3-MP-bimane (3-MPB) complex (Fig. 1). The reacted samples were then filtered with a 0.22 µm tetrafluoropolyethylene membrane syringe filter into autosampler vials fitted with 150 µL deactivated glass inserts for HPLC-MS-MS analysis. It should be noted that when the number of samples were above the maximum limit of the sample apparatus (e.g., the centrifuge), the samples that were not being actively prepared were stored in a standard refrigerator (4 °C) to impede degradation of the analyte.

Fig. 1.

3-MP in equilibrium with its dimer and its reaction with MBB to form a stable 3-MPB complex.

2.4. HPLC-MS-MS analysis of 3-MPB

A Shimadzu UHPLC (LC 20A Prominence, Kyoto, Japan) coupled to a 5500 Q-Trap mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA) along with an electrospray ion source was used for HPLC-MS-MS analysis. Separation was performed on a Phenomenex Synergy Fusion RP column (50 × 2.0 mm, 4 µm 80 Å) with an injection volume of 10 µL from samples stored in a cooled autosampler (15 °C). Mobile phase solutions consisted of 5 mM aqueous ammonium for-mate with 10% methanol (Mobile Phase A) and 5 mM ammonium for-mate in 90% methanol (Mobile Phase B). A gradient of 0–100% B was applied over 3 min, held constant for 0.5 min, then reduced to 0% B over 1.5 min. The total run-time was 5.1 min with a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min, and a 3-MPB retention time of about 2.75 min. The electrospray interface was kept at 500 °C with zero air nebulization at 90 psi in positive ionization mode with drying and curtain gasses held at 60 psi each. The ion-spray voltage, declustering potential, collision cell exit potential, and channel electron multiplier voltage were 4500, 121, 10, and 2600 V, respectively. Multiple-reaction-monitoring (MRM) transitions of 311 → 223.1 and 311 → 192.2 m/z for 3-MPB and 314 → 223.1 and 314 → 192.2 m/z for the internal standard-bimane complex were used with collision energies of 30.5 and 25 V, respectively. The dwell time was 100 ms for both transitions. Analyst software (Applied Biosystems version 1.5.2) was used for data acquisition and analysis.

2.5. Calibration, quantification and limit of detection

For validation of the analytical method, we generally followed the FDA bioanalytical method validation guidelines [29]. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) and upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) were defined using the following inclusion criteria: 1) calibrator precision of <15% RSD, and 2) accuracy of ±15% of the nominal calibrator concentration back-calculated from the calibration curve. The initial calibration curve was prepared with 0.2–500 µM calibration standards (0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500 µM) in plasma to determine the linear range, with the range later decreased to 0.5–100 µM for the optimized method. A calibration curve was also prepared in aqueous solution and compared to the plasma calibration curve to assess potential matrix effects. For all other experiments, calibration standards and QCs were prepared in rabbit plasma. QCs (N = 5) were prepared at three concentrations not included in the calibration curve: 1.5 µM (low QC), 7.5 µM (medium QC) and 35 µM (high QC). The internal standard was prepared daily and added to each sample, calibration standard and QC during sample preparation. QCs were prepared fresh each day in quintuplicate during intra-assay (daily) and inter-assay (over three separate days, within six calendar days) analyses and were used to calculate intra-assay and inter-assay accuracy and precision.

The limit of detection (LOD) was determined by analyzing multiple concentrations of 3-MP below the LLOQ and determining the lowest 3-MP concentration that reproducibly produced a signal-to-noise ratio of 3, with noise measured as the peak-to-peak noise directly adjacent to the 3-MP peak. It should be noted that 3-MP is inherently present in plasma of mammals [19,22] and was typically seen in rabbit plasma at concentrations below the limit of detection in this study.

2.6. Stability and recovery

To evaluate the stability of 3-MP, low and high QCs were stored at various temperatures (room temperature (RT), 4 °C, −20 °C, and −80 °C) and analyzed over multiple storage times. When storage stability samples were analyzed, internal standard was added as the QCs were prepared for analysis. Stability of 3-MP was calculated as a percentage of the initial concentration (“time zero”), with 3-MP considered stable if the concentration of a stored sample was within 10% of time zero. Long-term stability was conducted at three storage conditions (4, −20, and −80 °C). The samples were analyzed in triplicate after 1, 2, 8, 15, 30, and 45 days. Autosampler stability of 3-MPB was determined after typical preparation of low and high QCs and storage in the autosampler for approximately 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. For freeze-thaw stability of 3-MP, each set of low and high QCs was prepared in triplicate. Initially, one set of QCs (low and high) was analyzed. The other standards were stored at −80 °C for 24 h. All standards were then thawed unassisted at RT and one set of QCs was analyzed. The remaining QCs were replaced in the −80 °C freezer. This process was repeated twice more for three total freeze-thaw cycles.

For recovery, five aqueous low, medium and high QCs were prepared, analyzed, and compared with equivalent concentrations of plasma QCs. Recovery of 3-MP was calculated as a percentage by dividing the analyte plasma concentration with the calculated aqueous QC concentration.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. HPLC-MS-MS analysis of 3-MP from rabbit plasma

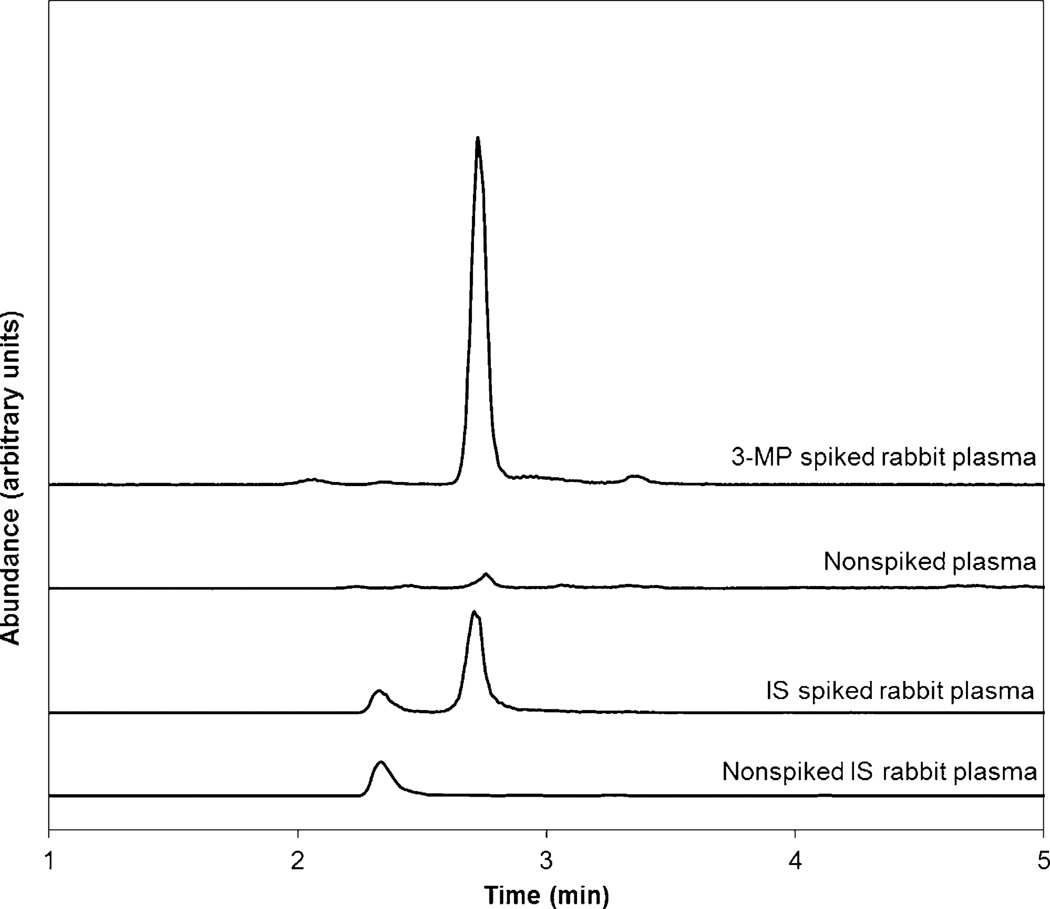

Under biological conditions, 3-MP is in rapid equilibrium with its dimer [30]. This equilibrium is difficult to control and results in poor chromatographic behavior. Because MBB reacts with the thiol group of 3-MP [26,27], which is essential for dimerization, a single 3-MPB complex is created (Fig. 1), which produced excellent chromatographic behavior. Fig. 2 shows representative chromatograms of spiked and nonspiked 3-MPB in plasma, with 3-MPB eluting at approximately 2.75 min. The method shows good selectivity for 3-MPB with no co-eluting peaks (Rs = 3.07 from the nearest peak at 3.3 min), although the nonspiked rabbit sample shows a small endogenous 3-MP concentration [19,21,22,24]. Considering the rabbit plasma analyzed for this study in aggregate, it is estimated that the endogenous concentration of 3-MP in rabbits is between 0.05 and 0.1 µM. The endogenous concentration of 3-MP has not been previously estimated due to rapid metabolism in vivo [21–23,31] and the lack of a sensitive analytical technique.

Fig. 2.

Representative chromatograms of 3-MP spiked (20 µM) and nonspiked rabbit plasma, monitoring the 311 → 223.1 m/z transition. The internal standard 314 → 223.1 m/z spiked and nonspiked in rabbit plasma is also shown. 3-MPB elutes at approximately 2.75 min. A small endogenous concentration of 3-MP can be observed in the nonspiked rabbit plasma.

The mass spectrum of 3-MPB, with tentative abundant ion assignments, is displayed in Fig. 3. The 311 → 223.1 and 311 → 192.2 transitions were selected as the quantification and identification transitions, respectively. The corresponding transitions for the internal standard, 314 → 223.1 and 314 → 192.2, were also monitored to correct for multiple sources of potential analysis error.

Fig. 3.

The mass spectrum of the 3-MPB complex with tentative identification of the abundant ions. The 3-MPB ion at 311 m/z corresponds to [M–H]+.

The simple sample preparation and short chromatographic analysis time for the method presented here permit rapid analysis of numerous plasma samples. The analysis of an individual sample using this method typically lasted approximately 1 h and 10 min, including 1 h for sample preparation and 7 min for chromatographic analysis (including equilibration time). Using conservative estimates, approximately 90 parallel samples could be prepared and analyzed in a 24 h period.

3.2. Linear range, limit of detection, and sensitivity

Calibration curves of 3-MP were constructed in the range of 0.2–500 µM in rabbit plasma. The signal ratio of each sample, defined as the peak area for each calibrator divided by its corresponding internal standard peak area was used as the corrected signal. Upon analysis of the calibration standards using non-weighted and weighted (1/x and 1/x2) calibration curves, 0.2, 200, and 500 µM standards were excluded because they did not meet the accuracy and/or precision inclusion criteria. The linear range for the method was 0.5–100 µM for 3-MP when using a 1/x2 weighted linear regression of the calibrators with a correlation coefficient (R2) >0.999. The LOD was 0.1 µM and the LLOQ and ULOQ of the method were 0.5 and 100 µM, respectively. Moderate matrix effects were observed for 3-MP analysis with the slope of the calibration curve in plasma reduced as compared to aqueous. Attempts were made to reduce the matrix effects using solid-phase extraction (i.e., weak, strong, and mixed-mode anion exchange stationary phases were tested for 3-MP, and C18-type stationary phases were tested for 3-MPB) with no reduction observed. Therefore, it is necessary to prepare all calibration standards in rabbit plasma to determine accurate concentrations of 3-MP.

3.3. Accuracy and precision

Accuracy and precision were determined by quintuplicate analysis of the low, medium, and high QCs (1.5, 7.5, and 35 µM, respectively) on three different days (within 6 calendar days; Table 1). The intra-assay accuracy (±9%) and precision (<7% RSD) and the inter-assay accuracy (±5%) and precision (<6% RSD) for the method were excellent relative to the typical precision and accuracy of analytical methods for the quantification of small molecules from plasma samples.

Table 1.

The accuracy and precision of 3-mercaptopyruvate analysis in spiked rabbit plasma by HPLC-MS-MS.

| Concentration (µM) | Intra-assay accuracya | Intra-assay precisiona | Inter-assay accuracyb | Inter-assay precisionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | 102 | 6.87 | 103 | 5.13 |

| 7.5 | 98 | 2.39 | 100 | 2.74 |

| 35 | 108 | 2.97 | 105 | 2.95 |

QC method validation (N = 5) for Day 1.

QC mean from three different days of method validation (N = 15).

3.4. Stability and recovery

Long-term storage stability of 3-MP in spiked plasma was evaluated at 4, −20 and −80 °C, with short-term stability evaluated at RT. Autosampler (2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 h) and freeze-thaw stability (3 cycles) were also evaluated. While 3-MP was stable at −80 °C for at least 45 days, it was quickly removed from plasma at RT, 4, and −20 °C (i.e., <1 day) and during freeze-thaw cycles (i.e., 3-MP was stable for only one freeze-thaw cycle). Lower storage temperatures generally increased the stability of 3-MP, likely due to a decrease in enzymatic activity. In the autosampler, 3-MPB was stable for at least 24 h (i.e., the measured concentrations were within 10% of the initial concentrations). The results from the stability study suggest that if storage is necessary, plasma samples should be frozen immediately and stored at −80 °C. Samples should then be prepared immediately after thawing, but can be stored on an autosampler for at least 24 h after preparation.

The recovery of 3-MP for low, medium and high QCs was 81, 75, and 75% respectively. These recoveries were below 90%, but were very consistent. Incomplete recovery can be explained by facile enzyme catalyzed conversion of 3-MP in the plasma [19,22,30] and may be an area for further improvement of the method.

3.5. Analysis of sulfanegen-exposed rabbits

The validated HPLC-MS-MS method was applied to the analysis of plasma from rabbits exposed to cyanide and subsequently treated with sulfanegen [14,20,21,24]. The HPLC-MS-MS analysis of the plasma of sulfanegen treated and untreated rabbits is shown in Fig. 4, alongside a chromatogram of 3-MP spiked rabbit plasma. Sulfanegen treated rabbits showed greatly elevated 3-MP concentrations compared to untreated rabbits. Overall, Fig. 4 confirms that the method presented here has the ability to detect elevated 3-MP concentrations from sulfanegen treated rabbits and may be applied to future studies of this next generation cyanide therapeutic. A full pharmacokinetic analysis of sulfanegen in rabbits by the described method will be reported in the near future.

Fig. 4.

HPLC-MS-MS chromatograms of 3-MP spiked rabbit plasma, plasma from a sulfanegen treated rabbit and plasma from the same rabbit prior to sulfanegen treatment. The 3-MP signal in the sulfanegen treated rabbits corresponds to 18 µM.

4. Conclusion

An HPLC-MS-MS method for the detection of 3-MP was developed which features simple sample preparation, excellent accuracy and precision, an excellent detection limit, and has a linear range of over 2 orders of magnitude. While Ogasawara et al. [25] reported an HPLC-fluorescence method for the analysis of 3-MP in mouse tissue, the method presented here featured simple and low-temperature sample preparation (i.e., 3-MP is highly unstable at high temperatures), rapid analysis, a reduced lower limit of quantification, a wider linear dynamic range, and the ability to analyze 3-MP from plasma of sulfanegen treated rabbits, which will facilitate the study of 3-MP prodrugs (e.g., sulfanegen) as treatments for cyanide poisoning.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support from a U.S. Dept. of Education, Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) award to the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry (P200A100103). We thank the National Science Foundation Major Research Instrumentation Program (Grant Number CHE-0922816) for funding the AB SCIEX QTRAP 5500 LC-MS-MS. We also would like to acknowledge the support by the CounterACT Program, National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (NIH OD), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), (Grant Number U01NS058087-06). In addition, the LC-MS-MS instrumentation in the South Dakota State University Campus Mass Spectrometry Facility used in this study was obtained with support from the National Science Foundation/EPSCoR (Grant No. 0091948) and the State of South Dakota. Furthermore, the authors are thankful to Dr. Sari B. Mahon from the Beckman Laser Institute and Dr. Matthew Brenner from the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care (University of California-Irvine, Irvine, CA) for providing sulfanegen treated rabbit plasma. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health or the CounterACT Program.

References

- 1.Barnes CD, Eltherington LG. Drug Dosages in Laboratory Animals-A Hand-book. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings TF. Occ. Med. 2004;54:82–85. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhandari RK, Oda RP, Youso SL, Petrikovics I, Bebarta VS, Rockwood GA, Logue BA. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;404:2287–2294. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logue BA, Hinkens DM, Baskin SI, Rockwood GA. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2010;40:122–147. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall AH, Saiers J, Baud F. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2009;39:541–552. doi: 10.1080/10408440802304944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gracia R, Shepard G. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:1358–1365. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.14.1358.43149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall AH, Rhumack BH, Emerg J. Med. 1987;5:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(87)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broderick KE, Potluri P, Zhuang S, Scheffler IE, Sharma VS, Pilz RB, Boss GR. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006:641–649. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marrs TC, Thompson JP. Clin. Toxicol. 2012;50:875–885. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2012.742197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borron SW, Baud FJ, Barriot P, Imbert M, Bismuth C. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007;49:794–801. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwertner HA, Valtier S, Bebarta VS. J. Chromatogr. B. 2012;905:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker CE, Benowitz NL, Forsyth JC, Hall AH, Mueller PD, Osterloh J, Toxicol J. Clin. Toxicol. 1993;31:277–294. doi: 10.3109/15563659309000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunel C, Widmer C, Augsburger M, Dussy F, Fracasso T. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012;223:e10–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner M, Kim JG, Lee J, Mahon SB, Lemor D, Ahdout R, Boss GR, Blackledge W, Jann L, Nagasawa HT, Patterson SE. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2010;248:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DesLauriers CA, Burda AM, Wahl M. Am. J. Ther. 2006;13:161–165. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000174349.89671.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cambal LK, Swanson MR, Yuan Q, Weitz AC, Li H-H, Pitt BR, Pearce LL, Peterson J. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:1104–1112. doi: 10.1021/tx2001042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearce LL, Bominaar EL, Hill BC, Peterson J. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52139–52144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310359200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reade MC, Davies SR, Morley PT, Dennett J, Jacobs IC. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2012;24:225–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isom GE, Borowitz JL, Mukhopadhyay S. In: Comprehensive Toxicology. McQueen C, editor. 2010. pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson SE, Monteil AR, Cohen JF, Crankshaw DL, Vince R, Nagasawa HT. J. Med. Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1021/jm301633x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagasawa HT, Goon DJW, Crankshaw DL, Vince R, Patterson SE. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:6462–6464. doi: 10.1021/jm7011497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spallarossa A, Forlani F, Carpen A, Armirotti A, Pagani S, Bolognesi M, Bordo D. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:583–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagahara N, Ito T, Minami M. Histol. Histopathol. 1999;14:1277–1286. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belani KG, Singh H, Beebe DS, George P, Patterson SE, Nagasawa HT, Vince R. Anesth. Analg. 2012;114:956–961. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824c4eb5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogasawara Y, Hirokawa T, Matsushima K, Koike S, Shibuya N, Tanabe S, Ishii K. J Chromatogr. B. 2013;931:56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosower NS, Kosower EM. In: Methods in Enzymology. Jakoby WB, Griffith OW, editors. Orlando, FL, USA: Academic Press, INC; 1987. pp. 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fahey RC, Newton GL. In: Methods in Enzymology. Jakoby WB, Griffith OW, editors. Orlando, FL, USA: Academic Press, INC; 1987. p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sample Preparation in Chromatography. Boston, MA, USA: Elsevier; 2002. pp. 473–524. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry bioanalytical method validation. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper AJL, Haber MT, Meister A. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:816–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ubuka T, Ohta J, Yao WB, Abe T, Teraoka T, Kurozumi Y. Amino Acids. 1992;2:143–155. doi: 10.1007/BF00806085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]