Abstract

We present the rationale for and design of a randomized, open-label, active-control trial comparing the effectiveness of 200 units of onabotulinum toxin A (Botox A®) versus sacral neuromodulation (InterStim®) therapy for refractory urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). The Refractory Overactive Bladder: Sacral NEuromodulation vs. BoTulinum Toxin Assessment (ROSETTA) trial compares changes in urgency urinary incontinence episodes over 6 months, as well as other lower urinary tract symptoms, adverse events and cost effectiveness in women receiving these two therapies. Eligible participants had previously attempted treatment with at least 2 medications and behavioral therapy. We discuss the importance of evaluating two very different interventions, the challenges related to recruitment, ethical considerations for two treatments with significantly different costs, follow up assessments and cost effectiveness. The ROSETTA trial will provide information to healthcare providers regarding the technical attributes of these interventions as well as the efficacy and safety of these two interventions on other lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms. Enrollment began in March, 2012 with anticipated end to recruitment in mid 2014.

Keywords: urgency urinary incontinence, sacral neuromodulation, onabotulinum toxin A

Introduction

Urgency urinary incontinence afflicts 17% of women over the age of 45 in the United States and 27% of all U.S. women over the age of 75.[1] Women with refractory UUI reporting a mean of 3 to 8 incontinence episodes/day[2–9] have spent years attempting treatment with pelvic floor muscle training, bladder control strategies, restricting fluids and use of anticholinergic medication therapy often without significantly improving their incontinence. Clinical studies of patients with refractory UUI have shown significant baseline impairments in quality of life as measured with several validated symptom specific distress and impact measures. [2–4, 6, 7, 10, 11] Treatments for refractory UUI include sacral neuromodulation and onabotulinum toxin A therapy.

InterStim® Therapy was approved as a permanent implanted neuromodulator device by the FDA in 1997 for use in the treatment of refractory UUI. In a staged procedure, an electrode is placed via the sacral foramen along a sacral nerve (usually S-3) and attached to an external test stimulator. If first stage stimulation is successful, in a second stage procedure, the lead is connected to an implanted pulse generator (IPG) that provides stimulation. Two studies randomized successful first stage participants with UUI (total=142) to either an immediate or delayed implant.[7, 9] At 6 months, both studies reported about half of the implanted group was dry (47% and 56%) versus 4–5% in the control. Sustained improvement in baseline incontinence parameters has been documented at 3–5 year follow-up.[8, 12] No life threatening or irreversible adverse events have been reported, but revisions and device removal due to lack of efficacy, infection and pain do occur.

Botox A® is injected into the bladder detrusor smooth muscle. In a randomized trial, long-term efficacy after a single 200U Botox A® injection was reported in 60–76% of patients with OAB and refractory idiopathic detrusor overactivity, with the mean duration of the effect of 6–7 months (range 5–11).[5, 13–15] There are no reported cases of permanent urinary retention after Botox A® injections; however, the incidence of symptomatic partial retention after 200U ranges between 0–30%.[3, 5, 6, 11, 13]

A recent Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)-sponsored systematic review on treatment of overactive bladder found insufficient evidence to guide the choice between these 2 very different therapies, supporting the need for a randomized trial comparing these treatment modalities.[16] The Refractory Overactive Bladder: Sacral NEuromodulation v. BoTulinum Toxin Assessment: ROSETTA trial was designed to compare the effectiveness of sacral neuromodulation, InterStim® therapy, to a single intradetrusor injection of Botox A® toxin (200U) over 6 months for the treatment of severe refractory UUI in a randomized trial.

Material and Methods

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network

The NICHD sponsored Pelvic Floor Disorders Network (pfdn.org) comprises a team of clinical researchers who conduct high- impact studies to advance knowledge and improve care for women with pelvic floor disorders. The team consists of representatives from the sponsor, clinical centers, the data coordinating center, and an external Steering Committee Chair. An independent Advisory Committee reviews protocols for scientific integrity; an independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) reviews protocols for ethical and safety standards, monitors the safety of ongoing clinical trials and provides advice on study conduct. Following IRB approval at the data coordinating center and each clinical site, written informed consent for research is obtained from each participant prior to enrollment.

Since each funding cycle spans 5 years, the previous funding cycle clinical centers were involved in study design (see Appendix). Enrollment for ROSETTA trial began with the current funding cycle clinical centers in March 2012 and is estimated to complete by March 2014 after randomization of 380 participants. This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01502956).

Study Design Overview

The ROSETTA trial assesses whether the reduction of mean number of UUI episodes over 6 months differs between sacral neuromodulation with InterStim® therapy and a single intradetrusor injection of Botox A® toxin (200U) for the treatment of refractory UUI. Eligible participants complete baseline symptom-specific and other assessments including a bladder diary demonstrating a minimum of 6 UUI episodes on a 3-day diary and urgency predominant UI, are randomized and then scheduled for either a first stage lead placement (FSLP) InterStim® or Botox A® injection visit. InterStim® therapy was FDA approved with the prerequisite that ≥ 50% improvement over baseline urinary symptoms (UUI episodes [UUIE], frequency) must be achieved for permanent generator (Stage II) implantation. We set the criterion for an initial clinical response to InterStim® therapy as a ≥50% improvement in the mean number of UUIE/day on a 3 day bladder diary. For participants randomized to InterStim®, this diary is completed during the testing period. Participants with a ≥ 50% improvement mean number of UUIE/day are eligible to receive the implantable pulse generator (IPG). Participants will then be followed monthly to determine the durability of this therapy. We set the same criteria for a successful clinical response after Botox A® injection. This assessment is made at one month from injection, and only those having a ≥50% improvement in the mean number of UUIE/day on a 3 day bladder diary are eligible for repeat Botox A® injections after 6 months.

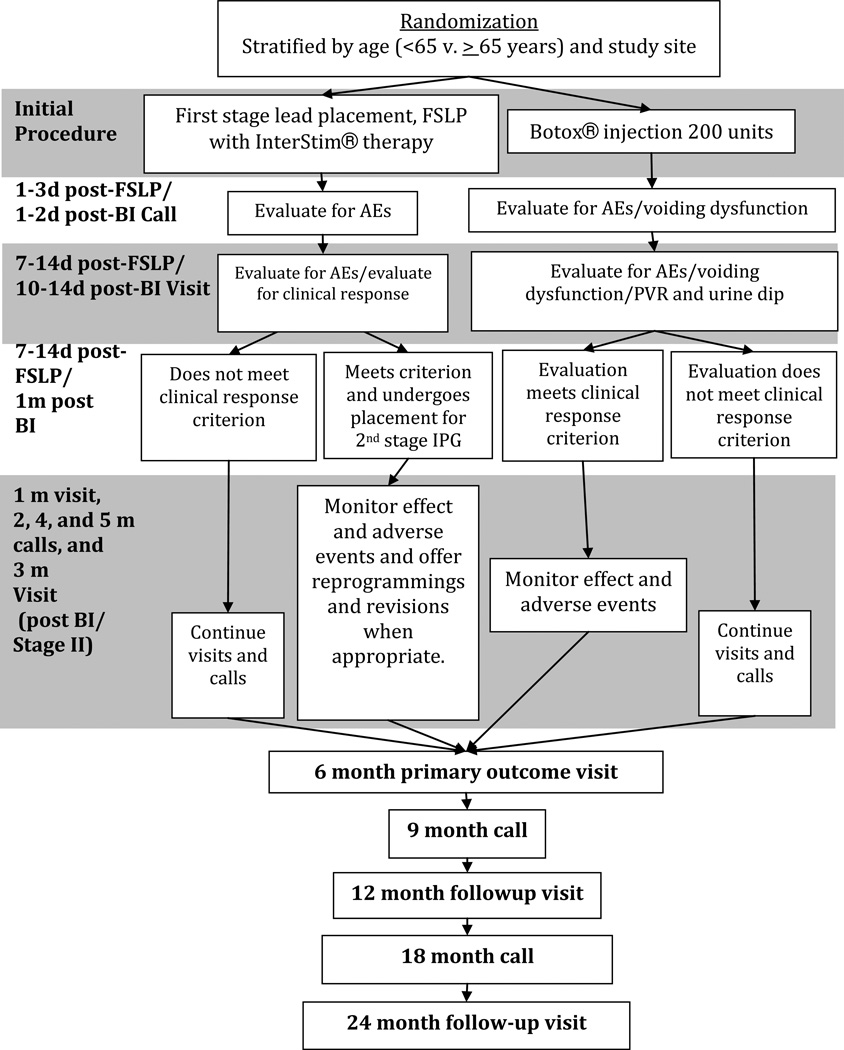

Since participants of this study have failed OAB medication and conservative therapy consisting of pelvic muscle exercises and other strategies, “responders” to Botox A® and InterStim® therapy are not allowed additional medical or conservative therapy. However, because participants have severe OAB symptoms, those who are “non responders” to the study interventions may go back on OAB medications or conservative therapy, and they continue to participate in all study follow-up visits and calls. After the primary outcome at 6 months, those who are “non responders” are allowed to obtain the study therapy to which they were not randomized, off study protocol. However, these participants continue to be followed in the study in an intent-to-treat analysis. To comprehensively assess effectiveness and adverse events, we follow the participants for at least 2 years. Fig. 1 summarizes the ROSETTA trial design.

Figure 1. Study Design Diagram.

Randomized, open-label, active-control, parallel-group study assessing InterStim® and Botox A®

Study Population

Women who have persistent severe UUI symptoms, defined as ≥ 6 UUI episodes on a 3-day bladder diary are recruited from urology and urogynecology subspecialty clinics as well as by other marketing methods. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are noted in Table 1. We exclude participants with a gross systemic neurologic condition believed to affect urologic function and clinically significant peripheral neuropathy, and complete spinal cord injury. Other exclusions include women with advanced Stage III pelvic organ prolapse as measured by the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification exam, a history of surgery for stress incontinence or prolapse within the last 6 months, and current use of a vaginal pessary, since these conditions could potentially affect urinary function. We chose not to limit our population to those with urodynamically proven detrusor overactivity (DO) that occurs only in a subset of women with UUI.[17] We felt using the definition of symptomatic UUI was more clinically meaningful and that exclusion of women who do not demonstrate DO may have limited recruitment. We exclude those with knowledge of planned MRIs, diathermy that would conflict with guidelines for implantation of a metal device. Overall, the inclusion criteria reflected women with severe UUI, similar both to previous studies for Interstim® and populations receiving 200U Botox A®.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

|

Exclusion Criteria

|

Baseline Assessments and Certifications

A summary of study visits is listed in Tables 2 and 3. At baseline, the study is explained and an IRB approved written consent is obtained. Baseline data collected in the clinic include medical and surgical history, physical exam including height and weight, urinalysis, serum creatinine level, and measurement of PVR. The PVR volume is measured with either a catheter or by ultrasound. If a PVR is 150 mL or greater on two occasions with a void over 150 ml, the patient is not eligible for participation, since Botox A® injection places women at risk for urinary retention. If a PVR value obtained by ultrasound is ≥150mL, the PVR is confirmed by catheterization. Assessment of functional mobility is completed in participants 65 years or older. Participants taking anticholinergic or β3 agonist therapy for UUI undergo a minimum of a 3-week washout period prior to completion of their baseline bladder diary. Participants are instructed to not start any conservative therapy including pelvic muscle exercises, other UI strategies or medical treatments for UUI during the first 6 months after intervention. The bladder diary is reviewed to ensure that entries are clear, interpretable and that eligibility criteria are met. Participants must have a cystometrogram and pressure flow study within the last 18 months; this is not used to determine eligibility but to better characterize the study population. Prior to randomization, participants are instructed on clean intermittent self catheterization (CISC), and the participant or an immediately available and identified person must demonstrate the ability to perform CISC to be eligible to participate in this study.

Table 2.

Timeline of visits/calls and measures through primary 6 Month Outcome

| Baseline/ screening |

Inject /FSLP^ |

3d call‡ | 2wk visit‡ | Implantation‡ | 1m visit† | 2m call† |

3m visit† |

4m call† | 5m call† | 6m visit † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Window | 1–4 wk period |

3±2d | 7–14d (Interstim) /10–14d (Botox) |

8–18d (Interstim) |

30±10d | 61±10d | 91±10d | 122±10d | 152±10d | 183±10d | |

| Consent | X | ||||||||||

| Biomarker/DNA collection | X | ||||||||||

| Hx/PE | X | ||||||||||

| Timed Up and Go | X | ||||||||||

| Urodynamic assessment | X | ||||||||||

| Serum creatinine | X | ||||||||||

| Preg test~ | X | ||||||||||

| Urine dip~ | X | X* | X* | X* | X* | X* | |||||

| PVR | X | X* | X* | X* | X* | ||||||

| Adv Events/voiding assessment | X | X/X* | X/X* | X** | X/X* | X/X* | X/X* | X/X* | X/X* | X/X* | |

| Bladder diary # | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| PGSC and OABq-SF | X (only OABq) | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Icon Programmer/ Device data** | X** | X** | X** | ||||||||

| Iconic Questionnaire ** | X** | X** | |||||||||

| IIQ-SF, UDI-SF, PISQ-12/R, Vaizey, Sandvik, Life-Space Assessment, HUI-3 | X | X | |||||||||

| PGII and OAB-SATq | X | ||||||||||

| ConMeds | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

<2 months (61 days after completion baseline/screening phase)

Relative to first injection or FSLP for those treated, to final decision to not treat for those not treated

Relative to first injection or final implantation/removal of device, to final decision to not treat for those not treated

Botox subjects only

InterStim subjects only

Also at before any subsequent reinjection or revision of surgery

Typically obtained during week prior to visit/call

Table 3.

Long-Term Follow

| 9m call† | 12m visit† | 18m call† | 24m visit† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Window | 274±28d | 365±28d | 548±28d` | 730±28d |

| Consent | ||||

| Hx/PE | ||||

| Timed Up and Go | ||||

| Urodynamic assessment | ||||

| Serum creatinine | ||||

| Preg test~ | ||||

| Urine dip~ | X* | X* | ||

| PVR | X* | X* | ||

| Adv Events/voiding assessment | X/X* | X/X* | X/X* | X/X* |

| Bladder diary # | X | X | X | X |

| PGSC and OABq-SF | X | X | X | X |

| Icon Programmer/ Device data** | X** | X** | ||

| Iconic Questionnaire ** | ||||

| IIQ-SF, UDI-SF, PISQ-12/R, Vaizey, Sandvik, Life-Space Assessment, HUI-3 | X | X | ||

| PGII and OAB-SATq | X | X | ||

| ConMeds | X | X | X | X |

<2 months (61 days after completion baseline/screening phase)

Relative to first injection or FSLP for those treated, to final decision to not treat for those not treated

Relative to first injection or final implantation/removal of device, to final decision to not treat for those not treated

Botox subjects only

InterStim subjects only

Also at before any subsequent reinjection or revision of surgery

Typically obtained during week prior to visit/calls

The therapeutic intervention is completed within three months (91 days) of enrolling/consenting into the study. If more than three months pass between completion of baseline phase and intervention, then study eligibility is reconfirmed prior to proceeding and the baseline urine dip and 3-day bladder diary are repeated.

Randomization

After completion of the baseline assessment, participants are randomized in a 1:1 fashion to onabotulinum toxin A (Botox A®) or sacral neuromodulation (InterStim® therapy) using permuted blocks, with a fixed block size known only to the DCC. We stratified the randomization by age (<65 years vs. ≥ 65 years) and by study site, since advancing age may be associated with decreased response to InterStim® therapy.[2, 18, 19] A random allocation sequence was generated by the DCC and loaded into a randomization system, a secure web-based application that allows research coordinators to enter the subject ID and stratification information. The system provides the randomization number to the coordinator. The computer-based method to determine the random allocation avoids the potential violations of the randomization scheme associated with envelope method, such as biased opening, loss, or misplacement in the randomization queue of the appropriate envelope.

All randomized participants are scheduled to participate in all study follow-up visits and calls regardless of whether or not they receive either study intervention or have a poor clinical response (non responders) and subsequently use other therapy such as anticholinergic medication. Those participants who receive either InterStim® or Botox® therapy and are “responders” are also followed per protocol and use of any additional supplemental therapy such as anticholinergic medication is discouraged; such use is considered a protocol deviation.

Voiding Diary Certification and Patient Instruction

All study coordinators and/or research staff who are responsible for evaluating and abstracting data from the bladder diary underwent a one-time Bladder Diary Abstraction Certification training and test. This exercise verifies consistency of definitions and approaches across the Network centers. On the voiding diary, time of awakening and bedtime are recorded, as well as number of pads used per day. Participants record the time of all voids and all incontinence episodes and mark the type of leakage (stress, urgency, or other). Voiding diary instructions included how to report the type of leakage event and examples of each type were given.

Physician Certification of InterStim®

Surgeons at each site who have performed a total of at least 10 Interstim procedures and are performing InterStim® implants routinely in their practice are designated as an InterStim® device implanter. All surgeons performing InterStim® surgery are required to view a short instructional video demonstrating optimal techniques and detailing placement of the lead in a standardized manner.

Clinician Interstim® Programmer Certification

One individual at each site, who must have attended the advanced programming course conducted by Medtronic or completed the online training Medtronic DVDs entitled “InterStim® Therapy for Urinary Control Programming Basics and N’Vision Clinician Programmer (Model 8840) Emulators”, is designated as the programming expert. The Clinician Programmer is able to interrogate and program signals to the neurostimulator and receive status information from the neurostimulator.

Physician Botox A® Certification

All physicians administering injections are required to view a short instructional video demonstrating optimal techniques and detailing sites of drug injection in a standardized manner. In addition, physicians at each site must have previously performed at least 10 injection procedures (either intradetrusor muscle or intraurethral).

Study Interventions

Botox A® Injection and Follow-up

The bladder is catheterized and 50 mL of 2% lidocaine placed in the bladder and 10 mL of 2% lidocaine jelly in the urethra. The participant is asked to lie on her left and right lateral decubitus for several minutes at a time to ensure diffuse anesthetic effect on the bladder. Cystoscopic surveillance of the bladder is used to confirm normality. Cystoscopy is performed with a 12 or 30-degree lens and rigid scope. A 22 gauge disposable needle, which is passed through the cystoscopic channel and secured via a luer lock screw, is used. Approximately 100–200 mL of total fluid is instilled during cystoscopy to allow adequate visualization of the entire bladder urothelium. Botulinum toxin A is prepared by dissolving 200U into 10 mL of injectable saline. Indigo carmine or methylene blue 0.1 mL is added to each syringe of onabotulinum toxin A. The surgeon injects a total of 10 mL of the diluted Botox A® into approximately 15 to 20 different detrusor muscle sites under direct visualization. Injections are distributed to equally cover the posterior bladder wall and dome but spare the bladder trigone and ureteral orifices. The anterior bladder dome is not injected secondary to technical difficulties associated with injecting this area cystoscopically. All participants receive a single dose of Ciprofloxacin 500mg orally immediately after injection, and participants continue to take Ciprofloxacin 500mg orally for 3 days post injection. If the patient is allergic to Ciprofloxacin, the investigator prescribes another clinically appropriate antibiotic. Participants receive a phone call on Day 3 (±2 days) after injection to assess voiding function and any adverse experiences. The study coordinator asks the participant to perform a PVR if they answer “yes” to the voiding assessment question from the Urogenital Distress Inventory-short form (UDI-SF) questionnaire: “Are you experiencing difficulty emptying your bladder? Participants are instructed to initiate CISC if the PVR>200mL and the participant answered “moderately” or “severely” to the question: How much does this bother you?”

| □1 | □2 | □3 | □4 |

| Not at All | Mildly | Moderately | Severely |

or if the PVR>300mL regardless of bother.

All participants are scheduled for their first post procedure visit 10–14 days after Botox A® injection with a research coordinator. Clinical staff obtains a urine dip and PVR and ask questions about difficulty emptying the bladder and adverse experiences. If participants require CISC, the coordinator contacts them weekly by phone to assess their voiding function and to determine whether they can discontinue CISC. Criteria to discontinue CISC are PVR ≤200 mL regardless of symptoms of incomplete emptying or ≤300 mL without symptoms of incomplete bladder emptying, as determined by the UDI-SF question above.

Only participants determined at the 1 month visit to have a clinical response from their initial injection (i.e. ≥50% improvement in number of UUIE/day on a 3 day bladder diary relative to baseline) may receive up to 2 additional injections between 6 months and 24 months after the initial injection. Eligibility for repeat injections is based on a Patient Global Symptom Control (PGSC) score of 1–2 and study inclusion/exclusion criteria (except inclusion items 2, 5 and 8 (Table 1). No injections are given at an interval less than 4 months. Participants who are eligible for a repeat injection but that who needed CISC for > 6 weeks after their initial Botox A® injection are dose-reduced to receive 100U of Botox A®. All other participants eligible for a repeat injection receive 200U Botox A®. Participants eligible for a 3rd (i.e. final injection) and who were dose-reduced for their 2nd injection have the option to receive either 100U or 200U with documentation of the rationale for their decision. If any participant required CISC for > 6 weeks after their 2nd injection, they are dose-reduced to 100U if they meet eligibility for a 3rd injection.

Interstim® Procedure and Follow-up

First Stage Lead Placement (FSLP) InterStim®

We standardized FSLP across all clinical centers. The surgical site is marked in the pre-operative surgical unit. Prior to operation, an antibiotic (either Ancef 1 gm or Clindamycin, if allergic to Penicillin) is given. The participant is given monitored anesthesia care (MAC) and local anesthesia with 1% bupivacaine. C-arm fluoroscopy is used to identify the sacral foramina. Spinal needles are placed in both S3 foramina. Both sides are stimulated and the side with the best response as determined by the surgeon undergoes lead placement into that S3 foramen. The tined Lead Model 3093 is used. Lead length is at the discretion of the surgeon. Each electrode is assessed intraoperatively for both sensory response (vaginal, perineal, rectal) and motor responses (bellows and/or toe). These parameters along with a standardized intensity rating of both the motor and sensory responses are recorded. Responses must be documented at an amplitude <5 Volts on at least 2 of the 4 electrodes; therefore, the lead is positioned close enough to the nerve to warrant very low amplitude for an appropriate S3 sensory response (without the stimulation being uncomfortable) or an appropriate S3 motor response. The lead tunneling and wire connections are completed and the surgeon determines the side of future generator placement. The incisions are closed in a subcuticular fashion, covered with Steri-strips™, dressed with gauze and covered with a medium-sized transparent film dressing (Tegaderm™). A large Tegaderm™ is then placed over the entire sacral area, overlying the individual dressings. PA and lateral Xray confirmation of lead placement is obtained at the end of the surgery and the films submitted to the hospital electronic radiologic system. Sensory responses, stimulus parameters, and electrode selections are reassessed and documented in the recovery room. A member of surgical team determines the external stimulator settings and two electrode combinations are determined and documented. Sensation type and intensity are documented on these two electrode combinations. A member of the study team reviews bladder diary instructions and how to use the external stimulator. Each participant completes a bladder diary during their testing period. Participants report UUIE/day on each testing day. Ciprofloxacin 500mg bid is given for the length of the testing period; if participant is allergic to Ciprofloxacin, doxycycline 100mg bid or Keflex 500mg bid is given for the same duration.

FSLP Testing Period (7–14 day period following FSLP)

During the testing period, the participants are contacted by phone by a member of the study team, and the participant may switch to the other electrode combination, as determined by the participant’s response. The 3 consecutive days on the bladder diary that represent optimized therapy are used to calculate degree of improvement. All participants are scheduled a first post-procedure visit with the coordinator and physician 7–14 days after FSLP. The physician determines if FSLP was successful using the 3 day bladder diary, and plans are made for the 2nd stage implantable pulse generator (IPG) or removal of the lead Women with a ≥ 50% improvement in the number of UUIE/day, as assessed by the mean UUIE/day over the consecutive 3 days of bladder diary recordings, relative to baseline, are eligible to undergo implantation of the IPG.

Continued sacral nerve stimulation is verified by confirming vaginal/perineal or rectal sensation of the stimulation. Those assessed as having a technical problem with their device as the cause for not responding may undergo a second attempt at lead placement. In this scenario, participants repeat the Day 3 telephone follow-up and FSLP testing period for the second FSLP attempt.

InterStim® Second Stage Surgery (IPG) (8–18 days following FSLP)

Participants with <50% improvement during the testing period or who do not desire placement of the IPG undergo MAC and local anesthesia for removal of the lead and connecting wires. Participants meeting criteria for and desiring placement of generator undergo MAC and local anesthesia for placement of either Neurostimulator Model 3023 (InterStim®) or Neurostimulator Model 3058 (Interstim II generator) as determined by the surgeon. If the participant has been requiring an amplitude setting of ≥5V during the testing period, then the Neurostimulator Model 3023 must be used. Participants are given their InterStim® iCon patient programmer (Model 3037) programmed with 4 different settings. After InterStim® implantation, participants are assessed regularly. If PGSC scores are 1–2 with technical problems deemed amenable to treatment or have pain or decreased efficacy (i.e. <50% reduction in UUIE/day), reprogramming is attempted. If reprogramming is unsuccessful or infection occurs, participants are offered a surgical revision. Only one InterStim® surgical revision is allowed for any reason (technical, pain, infection, lead migration) within the first 6 months. Any participant who has a surgical revision receives a phone call 3 days (+/− 2) after that revision. If PGSC scores are 1–2 and the InterStim® is functioning properly as assessed by the physician, participants are offered removal and an alternative therapy off study protocol. These participants are followed for a total of 2 years.

Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome Measure

The primary outcome is the change from baseline in mean number of UUIE over the first 6 months after intervention (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 month assessments) based on using each of the monthly 3-day bladder diaries at each of these time points. Using incontinence episodes as measured by a bladder diary provides consistency with prior InterStim® and Botox A® trials. Monthly assessment allows an assessment of average treatment effect over the entire active treatment period rather than change at a single time point, which is more consistent with the changing clinical response of Botox A®

Secondary Outcome Measures

Secondary outcomes were chosen that assess other symptoms, quality of life, general health status, and economic effects associated with these two approaches, both from the patient (patient reported measured outcomes) and societal perspective.

Symptom-specific and General Quality of Life Measures

Symptoms of UUI are measured at baseline and follow-up using the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OABq-SF)[20] and severity of UUI using the Sandvik questionnaire[21]; disease-specific quality of life measures include the Urinary Distress Inventory-SF (UDI-SF)[22] and the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short Form (IIQ-SF)[22]. Urinary frequency and nocturia are measured using the voiding diary. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence/Sexual Function Questionnaire Short Form (PISQ-12) and IUGA-Revised Form (PISQ-IR)[23],[24] are used to assess sexual function, and the St Mark’s (Vaizey) questionnaire[25] measures bowel incontinence. Assessment of general health using the Health Utilities Index Mark-3 (HUI-3) questionnaire[26] and the Life Space Assessment[27] is given to participants 65 years and older. A utilization of medical resources assessment is used to report cost effectiveness associated with incontinence symptoms and treatments.

Post intervention Treatment Specific Assessments

The proportion of participants with poor initial clinical response is assessed by bladder diary. The proportion of participants reporting adequate improvement of their bladder function is measured by the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I)[28] and the proportion of participants satisfied with their treatment is determined using the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction of Treatment questionnaire (OAB-SATq).[29] Standardized follow-up is performed to determine the proportion of participants requiring catheterization after 200U Botox A®, symptomatic urinary tract infections, as well as the proportion of participants requiring Botox A reinjections. Standardized follow-up is performed to determine proportion of participants having side effects of the InterStim® device such as site infection, pain or lead migration/decreased efficacy. In addition, the proportion of participants requiring reprogramming, surgical revisions, and removals of InterStim® device will be determined.

Cost-effectiveness Analysis

We plan to conduct a cost-effectiveness (CE) analysis from a payer perspective; CE will be expressed as incremental cost required to produce one additional unit of quality-adjusted life year (QALY). Data on each participant’s use of medical and non-medical resources related to urogynecologic conditions will be collected during the 24 month follow-up period. Costs will be estimated using the resource costing method where medical service use from each study case report form is monetized by multiplying the number of units of each medical service by the average unit cost of this service in dollars. This method allows a consistent capture of resource use when costs are incurred across multiple health systems or payers. Direct and indirect costs of the treatment of urinary incontinence with Botox A® injections and InterStim® and women’s preference for incontinence health states for improvement in UUI will be estimated. Study CRFs will capture incremental health care resource use related to study interventions, complications and other incontinence management. Average unit cost of services will be applied to medical service use reported at the 1, 3, 12, and 24-month visits to estimate costs based on the resource costing method. Information will be collected on procedures performed (e.g. InterStim®, Botox A® injections, reprogramming or surgical revision for InterStim® and reinjection for Botox A®), other incontinence treatment (e.g. OAB medications, pelvic floor rehabilitation), clinical events (e.g. UTI, admission for pyelonephritis), and physician visits. Medical service use costs will be assigned based on national Medicare reimbursement rates. The HUI-3algorithm[30] will be used to calculate each participant’s utility index at baseline and various follow up time points based on her responses to the HUI-3 questionnaire to compare change in QALYs between the two treatment groups. Using a general rather than condition-specific scale to calculate change in utilities allows comparison of cost-effectiveness results with other interventions and diseases.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure, change from baseline in mean number of UUIE per day over the initial 6-month period (i.e., change from baseline to average number of UUIE per day across months 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) provides a cumulative measure that accounts for potentially different efficacy trajectories for the two treatments. To test for differences in this cumulative measure, the outcome will be analyzed using all of the available monthly longitudinal diary from each study participant in a linear mixed model with time (treated as a categorical variable), treatment group, treatment by time interaction, site, and age stratum (<65 vs. ≥ 65 years) as fixed covariates and participant as a random effect to account for correlation of multiple measures obtained from each participant across time. Under the model, estimates will be generated for each time and treatment group combination and the primary hypothesis will test whether the difference between the average number of UUIE/day across months 1 though 6 and the baseline number of episodes for the InterStim® arm differs from that same difference for the Botox A® arm. The primary analysis set will use a modified intent to treat approach which includes participants who are randomized, treated, and have a baseline and at least one follow up observation of UUIE. For purposes of the primary analysis, any missing observations will be treated as missing at random.

A number of secondary analyses will compare changes in both clinical and quality of life measures across the two groups over time. These will generally use linear mixed model analyses comparable to those outlined above for the primary outcome for continuous measures, while binary outcome measures will be evaluated using generalized estimating equation extensions of generalized linear models (typically robust Poisson regressing models). Linear mixed models comparable to those used for the primary analyses will be used to generate adjusted analyses that control for baseline differences in clinical or demographic characteristics and any post-randomization differences in ancillary treatment.

Sample Size

Data from past studies were insufficient to provide robust estimates of the effects of Botox A® or InterStim® in patient populations similar to that proposed in this study; available studies vary in terms of the time points analyzed (from 1 month to 3 months for the Botox A® studies and 6 months to 5 years for the InterStim® studies), [3, 5, 8, 10–12, 14, 15] the endpoint used (UUI episodes per day or total incontinence episodes per day), and population studied (e.g., refractory UUI, refractory DOI, refractory OAB, urge/frequency). Thus, a conservative approach was taken to sample size calculations for this study that utilizes a modest treatment effect size and that does not incorporate the additional information obtained from utilization of the longitudinal measurements for the primary analyses. The sample sizes are based on a 2-sided test with a type I error rate of 5%, 80% power and a 10% loss-to-follow-up rate. A sample size of 316 evaluable participants (158 per treatment group) provides at least 80% power to detect an absolute difference of −2.0 urinary UUIE per day between the two treatments (considered to be the minimal clinically important difference for this outcome measure by the protocol committee), assuming a common SD of 6.0 and two-sided type I error rate of 5% and 10% loss to follow-up. Further adjusting the sample size to allow for a 20% initial non responder rate for each treatment group, the number to be enrolled and randomized will be 380 participants (190 per treatment group).

If the trial fails to detect a significant difference between Botox A® toxin and InterStim® therapy, interval estimates of the difference in change from baseline in the number of urgency incontinence episodes between the two groups will be generated to compare descriptively, the effectiveness of Botox A® toxin and InterStim® therapy. We propose that the descriptive non-inferiority margin be established at −1.0; at that level, the effect size of the less effective treatment would be at least 83% to 86% the effect size of the more effective treatment compared to placebo.

Discussion

The ROSETTA trial compares outcomes of an established operative approach for the treatment of refractory UUI, Interstim®, with a recently approved FDA- office based approach, Botox A®. As the Interstim® device is a sustained therapy with the implantation of a pulse generator and Botox A® therapy is a medical intervention that has a finite time of efficacy, numerous design issues and outcome considerations were required. Important design issues are noted below.

Cost Differential

Since there is a significant difference in the initial costs of the 2 therapies the investigators pursued budget strategies to assure equipoise between participants’ out of pocket expenses depending upon randomization group, by allowing a portion of available budget resources to cover those who were uninsured or underinsured.

Refusal of Randomization

It is acknowledged that participants may have a preconceived bias for one particular therapy over another, specifically an office based procedure over a surgical procedure. Therefore, investigators and study coordinators are provided with talking points reviewing the peri-operative process of the InterStim® staged procedure. In addition, since InterStim® has established criteria for permanent implantation, the investigators decided to set similar criteria for repeat therapeutic intervention with repeat Botox A® injections, after the initial injection, as criteria have not been established. Clinical staff emphasized that prior to consenting participants must be willing to accept either form of therapy upon enrollment and be comfortable with this decision post randomization. During protocol development, there was an ongoing randomized trial which compared InterStim® therapy to standard anticholinergic therapy. This investigation recruited adult participants who “had failed or could not tolerate at least one anticholinergic or anticholinergic medication not yet attempted”. Thirty-five sites enrolled 147 participants over a 5 year period. The study reported that 10 participants out of 19 who had a successful FSLP did not proceed on to 2nd Stage. clinicaltrials.gov NCT:000547378

Rationale for Primary Outcome Measure

The investigators discussed whether an objective, subjective or composite outcome measure was most clinically relevant for this trial. Change in incontinence episodes as measured by a bladder diary was chosen as our primary outcome as it is the most commonly reported outcome in InterStim® and Botox A® trials and the bladder diary has been shown to be a reliable measurement method for evaluating number of incontinence episodes. Capturing the effect longitudinally was also felt to be important given the different mechanism of action of the 2 treatment arms.

Rationale for Onabotulinum A toxin Dose

Another challenge during the design development was that the literature on Botox A® was evolving and began to include studies reporting lower rates of CISC, the primary adverse event of Botox A®, with use of lower doses of the toxin, 100 and 150 U. Many of those studies using lower doses also included participants complaining of urinary frequency and urgency without UUI and with baseline criteria of UUIE at a lower threshold for enrollment than for ROSETTA. Two hundred units of Botox A® was the dose chosen for this trial as our primary outcome was to evaluate the efficacy of a single injection of onabotulinum A toxin over 6 months and the literature supported 200 U as the dose most likely to provide this durability.[3–6, 13–15, 18, 31–34] Furthermore, our study population must demonstrate a minimum of 6 UUI episodes on a prospective 3 day bladder diary (minimum of 2 episodes/day) that is similar to previous populations in which 200 U was used. The baseline UUIE/day in this study is more severe than the degree of UUI in the Allergan-sponsored onabotulinum A toxin dose finding study where participants were required to document a minimum of 1.14 UIE/day. [31] In August 2011, the FDA approved 200U of onabotulinum A toxin for urinary incontinence in adults with neurologic conditions and in January 2013, 100U was approved to treat refractory idiopathic OAB.

The placebo-controlled Botox A® studies reported a 16–28% urinary tract infection post procedural rate after placebo injections in the UUI population. Additionally, when considering other factors such as procedural discomfort, clinical assessments and procedure visits for reinjection, a clinically reasonable inter-injection period is a minimum of 4 months with potential for durability beyond 6 months. No studies show this benefit at 6 months using lower doses and assessing objective outcomes of continence status. Many studies have shown results to the contrary. [18, 35, 36]

Due to variability in monitoring PVRs in the published literature after Botox A® injections, the incidence of symptomatic partial retention remains unclear. However, studies using 200U report a clean intermittent self catheterization (CISC) rate between 0–30%. The dose response trial found an increase in PVR rate of 18–28% but the findings did not support a direct correlation between increasing dose and need for CISC nor duration of CISC. [31] In addition, it has been reported that dose reduction does not necessarily resolve the need to perform CISC and duration of efficacy was reduced. [37] This further supported the need to investigate other factors, which may predispose a patient to voiding dysfunction after Botox A® injection. It was decided to modify the design of the study after the 6 month primary outcome. This modification included a “dose reduction” to 100U for participant’s second Botox A® injection if the participant had to perform CISC for >6 weeks after their first injection and for participant’s to be able to select their 3rd dose. In light of the FDA’s approval of 100U Botox A® in the non-neurogenic, idiopathic population occurring during the recruitment phase of this study, this modification to the design will provide important clinical information for ongoing Botox therapy.

Rationale for Criteria for CISC

Many studies described impaired bladder emptying after routine PVR checks and not necessarily according to symptomatology. [3, 4, 6, 31] In the dose response trial, 28.8% of participants injected with 200U of Botox A® had a documented post treatment PVR of >200 mL. However, a stated limitation was that a PVR>200 mL was recorded as an adverse event regardless of symptoms or need for intervention. Importantly, no participants discontinued treatment due to a treatment related adverse event. [31] Two studies evaluated upper urinary tract (kidney) function with serum creatinine measurements and renal ultrasound after Botox A® injections and found no abnormalities even in the patients with partial urinary retention.[18, 35] Therefore the protocol committee chose to initiate catheterization at residual volumes >300 mL or >200 mL in the presence of bothersome retention symptoms.

Economic Evaluation

An important facet of this trial design is its comparison of a surgical procedure in the operating room to an office-based procedure. Cost analysis studies depending on the period of time assessed from initial treatment have predicted Botox A® being more cost effective than InterStim® in the short term. We plan to explicitly measure direct and indirect costs as well as quality adjusted life years (QALYs) using standard approaches to determine if either approach would be preferred.

Strengths

This landmark trial is the first such study to compare a surgical procedure involving an implantable device to bladder injections performed in an office based setting for the treatment of refractory UUI. The robust design of this multisite trial includes allocation concealment, use of objective, reliable outcomes and precise measurements with validated subjective measure and a cost effective analysis conducted from a payer perspective expressed as incremental cost required to produce one additional unit of quality-adjusted life year (QALY). The multi-site performance and the broad eligibility criteria including inclusion of all adult females facilitate applicability of the findings of the study. In addition, intra-operative testing assessing specific characteristics of stimulation responses may assist in development of algorithms to predict success. The multi center nature of this trial increases generalizability of results and required standardization the InterStim® and Botox A® surgical techniques as well as perioperative management.

Although InterStim® is relatively expensive within the first month of therapy, if greater efficacy is achieved over a longer treatment period, it is possible that costs may become favorable compared to the cost of Botox A® injections. The inclusion of a detailed cost-effectiveness analysis in this trial allows us to fully and accurately describe the differences and to inform policy makers of the costs relative to the incremental benefits. Finally, the ROSETTA trial addresses recommendations from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)- sponsored systematic review by assessing new treatment for refractory UUI in a rigorous randomized manner.

Limitations

Limitations to the study design of this randomized trial include the non-blinded active intervention design. The design as a double blind randomized trial would have involved sham surgeries that may have compromised recruitment as well as adding significantly more complexity and cost to the study jeopardizing the feasibility of this comparative trial. The research question does measure a relatively short-term primary outcome time point (6 months). However, it is reasonable, in light of our primary hypothesis and shorter duration of effect for Botox.

Conclusion

The ROSETTA trial challenged the investigators to address a clinically difficult population and consider study designs and comparative groups while contemplating issues related to ethics, evolving clinical information and availability of treatment, as well as specific issues related to comparing two unique treatment modalities. Findings from the ROSETTA trial will provide valuable information that will help clinicians counsel women on the benefits and risks of these 2 treatment modalities for the treatment of refractory severe UUI and allow a more informed choice of management for both patients and providers.

Appendix

Pelvic Floor Disorders Network Members

Duke University

Anthony G. Visco, MD, Principal Investigator

Cindy L. Amundsen, MD, Co-Investigator

Alison C. Weidner, MD, Co-Investigator

Nazema Y. Siddiqui, MD, MHSc, Co-Investigator

Shantae N. McLean, MPH, Research Coordinator

Mary J. Raynor, RN, BSN, Research Coordinator

Dominique Clark, BS, Research Assistant

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Holly E. Richter, PhD, MD, Principal Investigator

Kathryn L. Burgio, PhD, Co-Investigator

R. Edward Varner, MD, Co-Investigator

Robert L. Holley, MD, Co-Investigator

Patricia S. Goode, MD, Co-Investigator

L. Keith Lloyd, MD, Co-Investigator

Tracey Wilson, MD, Co-Investigator

Alayne D. Markland, DO, Co-Investigator

Velria Willis, RN, BSN, Research Coordinator

Nancy Saxon, BSN, Research Nurse Clinician

LaChele Ward, LPN, Research Specialist

Lisa S. Pair, CRNP

University of California, San Diego and Kaiser, San Diego

Charles W. Nager, MD, Principal Investigator

Shawn A. Menefee, MD, Co-Investigator

Emily Lukacz, MD, Co-Investigator

Karl M. Luber, MD, Co-Investigator

Michael E. Albo, MD, Co-Investigator

Keisha Dyer, MD, Co-Investigator

Gouri Diwadkar, Co-Investigator

Leah Merrin, Study Coordinator

Giselle Zazueta-Damian, Study Coordinator

Cleveland Clinic

Mathew D. Barber, MD, MHS, Principal Investigator

Marie Fidela R. Paraiso, MD, Co-Investigator

Mark D. Walters, MD, Co-Investigator

J. Eric Jelovsek, MD, Co-Investigator

Linda McElrath, RN, Research Nurse Coordinator

Donel Murphy, RN, MSN, Research Nurse

Cheryl Williams, Research Assistant

University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas

Joseph Schaffer, MD, Principal Investigator

Clifford Wai, MD, Co-Investigator

Marlene Corton, MD, Co-Investigator

David Rahn, MD, Co-Investigator

Gary Lemack, MD, Co-Investigator

Kelly Moore, RN, Research Coordinator

Shanna Atnip, NP

Margaret Hull, NP

Pam Martinez, NP

Deborah Lawson, NP

Loyola University, Chicago

Linda Brubaker, MD, MS, Principal Investigator

Kimberly Kenton, MD, MS, Investigator

MaryPat FitzGerald, MD, MS, Investigator

Elizabeth Mueller, MD, MSME, Investigator

Mary Tulke, RN, Study Coordinator

University of Utah

Ingrid Nygaard, MD, Principal Investigator

Peggy Norton, MD, Co-Investigator

Yvonne Hsu, MD, Investigator

Linda Freeman, RN, Research Coordinator

Shirley Ranke, RN, Research nurse

Laura Burr, RN, Research nurse

Linda Griffen, RN, Research coordinator

RTI International (Data Coordinating Center)

Dennis Wallace, PhD, Principal Investigator

Marie Gantz, PhD, Alternate Principal Investigator

Tracy Nolen, DrPH, Study Statistician

Ryan Whitworth, MPH, Statistician & Data Manager

Carolyn Huitema, MS, DCC Study Coordinator

Kevin Wilson, MS, Data Systems Manager

Tamara Terry, BA, Quality of Life Coordinator

James Pickett, BS, Data Systems Programmer

Geeta Sunkara, MS, Data Manager

University of Michigan

Cathie Spino, DSc, Principal Investigator

John T. Wei, MD, MS, Co-Principal Investigator

Beverly Marchant, RN, Project Manager

Donna DiFranco, MPHMPHBS, Clinical Monitor

John O.L. DeLancey, MD, Co-Investigator

Dee Fenner, MD, Co-Investigator

Nancy K. Janz, PhD, Co-Investigator

Wen Ye, PhD, Statistician

Zhen Chen, MS, Statistician

Yang Wang Casher, MS, Database Programmer

NICHD Bethesda, MD

Susan Meikle M.D., M.S.P.H, project scientist for the PFDN

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supported by grants from The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, (U10-HD041267, U10 HD041261, U10 HD054214, U10 HD054215, U10 HD054241, U10 HD041250, U10 HD069031, U10 HD069010) and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health.

This trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov under Registration #: NCT01502956.

References

- 1.Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, Abrams P, Herzog AR, Corey R, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–336. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amundsen CL, Romero AA, Jamison MG, Webster GD. Sacral neuromodulation for intractable urge incontinence: are there factors associated with cure? Urology. 2005;66:746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brubaker L, Richter HE, Visco A, Mahajan S, Nygaard I, Braun TM, et al. Refractory idiopathic urge urinary incontinence and botulinum A injection. The Journal of urology. 2008;180:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flynn MK, Amundsen CL, Perevich M, Liu F, Webster GD. Outcome of a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial of botulinum A toxin for refractory overactive bladder. The Journal of urology. 2009;181:2608. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajkumar GN, Small DR, Mustafa AW, Conn G. A prospective study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, efficacy and durability of response of intravesical injection of botulinum toxin type A into detrusor muscle in patients with refractory idiopathic detrusor overactivity. BJU Int. 2005;96:848–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sahai A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Efficacy of botulinum toxin-A for treating idiopathic detrusor overactivity: results from a single center, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. The Journal of urology. 2007;177:2231–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt RA, Jonas U, Oleson KA, Janknegt RA, Hassouna MM, Siegel SW, et al. Sacral nerve stimulation for treatment of refractory urinary urge incontinence. Sacral Nerve Stimulation Study Group. The Journal of urology. 1999;162:352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel SW, Catanzaro F, Dijkema HE, Elhilali MM, Fowler CJ, Gajewski JB, et al. Long-term results of a multicenter study on sacral nerve stimulation for treatment of urinary urge incontinence, urgency-frequency, and retention. Urology. 2000;56:87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weil EH, Ruiz-Cerda JL, Eerdmans PH, Janknegt RA, Bemelmans BL, van Kerrebroeck PE. Sacral root neuromodulation in the treatment of refractory urinary urge incontinence: a prospective randomized clinical trial. European urology. 2000;37:161–171. doi: 10.1159/000020134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster RT, Sr, Anoia EJ, Webster GD, Amundsen CL. In patients undergoing neuromodulation for intractable urge incontinence a reduction in 24-hr pad weight after the initial test stimulation best predicts long-term patient satisfaction. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2007;26:213–217. doi: 10.1002/nau.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalsi V, Apostolidis A, Popat R, Gonzales G, Fowler CJ, Dasgupta P. Quality of life changes in patients with neurogenic versus idiopathic detrusor overactivity after intradetrusor injections of botulinum neurotoxin type A and correlations with lower urinary tract symptoms and urodynamic changes. European urology. 2006;49:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Kerrebroeck PE, van Voskuilen AC, Heesakkers JP, Lycklama á Nijholt AA, Siegel S, Jonas U, et al. Results of sacral neuromodulation therapy for urinary voiding dysfunction: outcomes of a prospective, worldwide clinical study. The Journal of urology. 2007;178:2029–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo HC. Clinical effects of suburothelial injection of botulinum A toxin on patients with nonneurogenic detrusor overactivity refractory to anticholinergics. Urology. 2005;66:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makovey I, Davis T, Guralnick ML, O'Connor RC. Botulinum toxin outcomes for idiopathic overactive bladder stratified by indication: lack of anticholinergic efficacy versus intolerability. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2011;30:1538–1540. doi: 10.1002/nau.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White WM, Pickens RB, Doggweiler R, Klein FA. A Short-term efficacy of botulinum toxin a for refractory overactive bladder in the elderly population. The Journal of urology. 2008;180:2522–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann KE, McPheeters ML, Biller DH, Ward RM, McKoy JN, Jerome RN, et al. Treatment of overactive bladder in women. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2009:1–120. v. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sand PK, Hill RC, Ostergard DR. Incontinence history as a predictor of detrusor stability. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1988;71:257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo HC. Will suburothelial injection of small dose of botulinum A toxin have similar therapeutic effects and less adverse events for refractory detrusor overactivity? Urology. 2006;68:993–997. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.054. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White WM, Mobley JD, 3rd, Doggweiler R, Dobmeyer-Dittrich C, Klein FA. Sacral nerve stimulation for refractory overactive bladder in the elderly population. The Journal of urology. 2009;182:1449–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coyne KS, Matza LS, Brewster-Jordan J. "We have to stop again?!": The impact of overactive bladder on family members. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2009;28:969–975. doi: 10.1002/nau.20705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandvik H, Seim A, Vanvik A, Hunskaar S. A severity index for epidemiological surveys of female urinary incontinence: Comparison with 48-hour pad-weighing tests. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2000;19:137–145. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:2<137::aid-nau4>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, McClish DK. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Neurourology and urodynamics. 1995;14:131–139. doi: 10.1002/nau.1930140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, Khalsa S, Qualls C. A short form of the pelvic organ prolapse/urinary incontinence sexual questionnaire (PISQ-12) International Urogynecology Journal. 2003;14:164–168. doi: 10.1007/s00192-003-1063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers R, Rockwood T, Constantine M, Thakar R, Kammerer-Doak D, Pauls R, et al. A new measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-Revised (PISQ-IR) International urogynecology journal. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-2020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44:77–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feeny D, Furlong W, Torrance GW, Goldsmith CH, Zhu Z, DePauw S, et al. Multiattribute and single-attribute utility functions for the health utilities index mark 3 system. Medical care. 2002;40:113–128. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peel C, Baker PS, Roth DL, Brown CJ, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Assessing mobility in older adults: the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment. Physical Therapy. 2005;85:1008–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;189:98–101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolis MK, Fox KM, Cerulli A, Ariely R, Kahler KH, Coyne KS. Psychometric validation of the overactive bladder satisfaction with treatment questionnaire (OAB-SAT-q) Neurourology and urodynamics. 2009;28:416–422. doi: 10.1002/nau.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harvie HS, Shea JA, Andy UU, Propert K, Schwartz JS, Arya LA. Validity of utility measures for women with urge, stress, and mixed urinary incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;210:85 e1–85 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dmochowski R, Chapple C, Nitti VW, Chancellor M, Everaert K, Thompson C, et al. Efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA for idiopathic overactive bladder: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized, dose ranging trial. The Journal of urology. 2010;184:2416–2422. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo HC. Comparison of effectiveness of detrusor, suburothelial and bladder base injections of botulinum toxin a for idiopathic detrusor overactivity. The Journal of urology. 2007;178:1359–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White WM, Pickens RB, Doggweiler R, Klein FA. Short-term efficacy of botulinum toxin a for refractory overactive bladder in the elderly population. The Journal of urology. 2008;180:2522–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tincello DG, Kenyon S, Abrams KR, Mayne C, Toozs-Hobson P, Taylor D, et al. Botulinum toxin a versus placebo for refractory detrusor overactivity in women: a randomised blinded placebo-controlled trial of 240 women (the RELAX study) European urology. 2012;62:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid DM, Sauermann P, Werner M, Schuessler B, Blick N, Muentener M, et al. Experience with 100 cases treated with botulinum-A toxin injections in the detrusor muscle for idiopathic overactive bladder syndrome refractory to anticholinergics. The Journal of urology. 2006;176:177–185. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werner M, Schmid DM, Schussler B. Efficacy of botulinum-A toxin in the treatment of detrusor overactivity incontinence: a prospective nonrandomized study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;192:1735–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahai A, Dowson C, Khan MS, Dasgupta P Group GKTBS. Repeated injections of botulinum toxin-A for idiopathic detrusor overactivity. Urology. 2010;75:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]