Abstract

Purpose

Low health literacy is associated with inadequate health care utilization and poor health outcomes, particularly among elderly persons. There is a dearth of research exploring the relationship between health literacy and place of residence (urbanicity). This study examined the association between urbanicity and health literacy, as well as factors related to low health literacy, among cancer patients.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with a population-based sample of 1,841 cancer patients in Wisconsin. Data on sociodemographics, urbanicity, clinical characteristics, insurance status, and health literacy were obtained from the state’s cancer registry and participants’ answers to a mailed questionnaire. Partially and fully adjusted multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to examine: 1) the association between urbanicity and health literacy, and 2) the role of socioeconomic status as a possible mediator of this relationship.

Findings

Rural cancer patients had a 33% (95% CI: 1.06–1.67) higher odds of having lower levels of health literacy than their counterparts in more urbanized areas of Wisconsin. The association between urbanicity and health literacy attenuated after controlling for socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

Level of urbanicity was significantly related to health literacy. Socioeconomic status fully mediated the relationship between urbanicity and health literacy. These results call for policies and interventions to assess and address health literacy barriers among cancer patients in rural areas.

Keywords: cancer, health disparities, health literacy, rural, socioeconomic status

Low health literacy is an extensive problem in the United States. Approximately 80 million adults (36%) have limited health literacy.1, 2 Low health literacy is increasingly recognized as an important individual-level predictor of poor overall health and higher mortality among seniors.1, 3, 4 Research indicates those with low health literacy may have difficulty understanding, obtaining, and retaining health information.5 Low health literacy is also associated with under-utilization of preventive health care services, increased use of emergency services and hospitalizations, and worse physical functioning and mental health.1, 5–8 Broadly defined, the term “health literacy” encompasses an array of skills required to understand health and to function in a health care environment. The Institute of Medicine defined health literacy as the “degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic information and services needed to make appropriate decisions regarding their health.”9 The American Medical Association states that health literacy is a “constellation of skills that constitute the ability to perform basic reading and numerical tasks for functioning in the health care environment and acting on health care information.”10

Health literacy has been found to be an important factor for cancer prevention and control.3, 11 Adults with limited literacy obtain less information from cancer prevention and control materials and may be less likely to be screened for cancer.11 For instance, a review of the literature found that low health literacy is associated with a lower probability of mammography screening.1, 4 Low literacy is also associated with a 1.6 times higher odds of being diagnosed at a later stage of prostate cancer and having an inadequate understanding of complex information about cancer.11, 12 Low health literacy may hinder cancer patients’ ability to understand consent forms, follow medication directions, and manage their disease.3, 5, 11

Previous research has examined the association between health literacy and sociodemographic factors, including income, education, racial and ethnic minority status, age, and recent immigration to the United States.1, 3, 5, 11, 13 Health literacy has also been associated with lack of insurance coverage.2 Results from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) showed that, among US adults without health insurance, 28% had low (below basic) health literacy.2 Relatively less attention has been paid to the relationship between health literacy and place of residence (urbanicity). Previous research has indicated that living in rural and non-metropolitan areas is associated with higher incidence of late-stage lymphoma and prostate cancer and lower survival rates among lymphoma patients.14, 15 Studies have shown that rural residence is also associated with lower cancer screening rates, later diagnosis stage, as well as a higher incidence of lung, prostate, colon, and cervical cancer in specific US regions.14, 16–18 Whether health literacy may explain, at least partially, these associations is unknown.

Rural areas are disproportionately represented among US counties designated as medically underserved and have fewer physicians, specialists, and hospitals per capita than their urban counterparts.19, 20 One study reported no difference in health literacy between rural and urban residents.13 Instead, the results of that study suggested a U-shaped curve with lower literacy levels in urban and rural areas and higher health literacy in suburban areas.13 Characteristics typically associated with low health literacy (eg, poverty, inadequate or lack of health insurance, and the absence of a usual source of care) are more concentrated among residents of rural areas and could result in worse health outcomes and health care access for rural cancer patients independent of health literacy levels.18–20

Health literacy research has called for further investigation into sociodemographic characteristics as potential mediators, rather than confounders of relationships between health literacy and other variables such as health care utilization and health outcomes.6, 7 Cancer patients residing in medically underserved or rural areas may have lower income and education levels than patients in more urbanized areas. These socioeconomic factors could be associated with lower health literacy levels among rural patients compared to those living in more urbanized regions. Therefore, socioeconomic status could explain, at least to some extent, the relationship between rural residency and lower health literacy levels.

This study attempts to fill the gaps in knowledge regarding the relationship between urbanicity and health literacy by a) investigating the association between rural residence and health literacy in a population-based sample of cancer patients in Wisconsin, and b) testing whether education, income, and other sociodemographic factors mediate this relationship.

METHODS

Data

Data from the Assessment of Cancer Care and Satisfaction (ACCESS) study were used in these analyses.21 ACCESS was a cross-sectional survey designed to gather data on cancer care, patient satisfaction, co-morbid conditions, and quality of life among a population-based sample of Wisconsin cancer patients. The ACCESS study was conducted from 2006–2007. Eligible participants were Wisconsin residents aged 18–79 years old, newly diagnosed with lung, prostate, breast, or colorectal cancer in 2004, and reported to the Wisconsin Cancer Reporting System (WCRS). Eligibility for the ACCESS study was limited to those with valid addresses and those who were alive at first contact. Eligibility for lung cancer cases also required a publicly available telephone number. To increase minority representation in the sample, all non-white and/or Hispanic cases were selected for participation. A random sample of non-Hispanic white cancer cases and all lung cancer cases with valid phone numbers were selected from the WCRS database. In 2006, subjects were mailed a packet including a survey with a cover letter, a study participant information sheet, and a book of US postage stamps that served as an incentive (value: $7.80). Telephone calls were made to non-respondents 5 weeks after the initial mailing and 2 weeks after the second mailing.21 Due to poor prognosis, lung cancer patients were called 1 week after the initial mailing and offered the opportunity to participate.21 Of the 3,265 cancer patients selected for participation, 2,740 were living. A total of 1,841 cancer cases completed the survey (1,686 by mail and 155 by phone), yielding a response rate of 67.7% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the ACCESS study population

Health Literacy

Health literacy was assessed using 4 self-reported health literacy measurement questions on a 5-point Likert scale. Three of the questions had been validated in 2 previous studies using the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy (STOFHLA) and the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM).22, 23 These questions measured the frequency of needing help reading hospital materials, filling out medical forms, and having problems learning about their medical condition.22, 23 The fourth question assessed the frequency of having difficulty taking medications properly. The 5-point Likert scale was used (Always, Often, Sometimes, Occasionally, and Never). The responses to the question “How often can you fill out medical forms by yourself?” were reverse-coded to be consistent with the direction of the other questions. A composite health literacy variable was created by summing the scores of the 4 health literacy questions (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.63). Higher scores reflected higher levels of health literacy. The variable was then dichotomized to categorize cancer patients into the highest health literacy group (a score of 20 on a scale of 1–20) or into the group who have any health literacy problems (less than 20). This classification represents the most sensitive approach in detecting potential health literacy problems and is consistent with recommendations from previous studies that have used these or similar health literacy questions.22–25 The sample was restricted to those who responded to all 4 questions. Those who responded to none (4.45%), one (0.43%), two (0.38%), or three (1.58%) of the questions were classified as missing and comprised 6.8% of the sample (N=126).

Urbanicity

Information on county of residence was gathered from the WCRS. We used the National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) 6-level Urban-Rural classification scheme to categorize study participants according to county of residence, as follows: (1) Large Central Metro, (2) Large Fringe Metro, (3) Medium Metro, (4) Small Metro, (5) Micropolitan, and (6) Noncore. For the purposes of this study, counties in groups 2–4 were combined and designated as the “mixed urban-rural” group. Milwaukee County is the only county in Wisconsin designated as Large Central Metro and serves as the “urban” group. Milwaukee County was used as a unique category because existing data indicate high levels of health disparities as well as a high prevalence of poor health indicators and outcomes in this county.26 Counties grouped into categories 5–6 comprised the “Rural” group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Rural, Urban, and Mixed Urban-Rural Counties in Wisconsin

Education and Income

Levels of education and income were self-reported in the ACCESS survey. Respondents were classified in one of the following total annual household income categories: Less than $15,000; $15,000–$29,999; $30,000–$49,999; $50,000–$99,999; or more than $100,000. Respondents were also classified according to their highest degree or year of school completed: Grades 1–11 or lower (less than high school), grade 12 (high school diploma, GED, or any school equivalent), 1–3 years of college (junior college), 4 years of college (college degree), or advanced degree (M.A., Ph.D., M.D., J.D., etc.). Respondents who did not provide information on level of income (n=229) or education (n=40) were included in the analysis but using indicator variables representing missing education and/or income data.

Covariates

Cancer site, cancer stage at time of diagnosis, age at cancer diagnosis, and sex were determined based on data from the WCRS. Stages of cancer were designated as 0 (in situ), 1 (localized), 2 (regional, direct extension), 3 (regional, nodes only), 4 (regional, direct extension and nodes), 5 (regional, not otherwise specified), 7 (distant/systemic), and 9 (unstaged/unknown). Three indicator variables were created for cancer stage: Stage 1 (stage 1), Stage 2 (stages 2–5, 7), and Unknown (stages 0, 9). Race and ethnicity were based on participants’ responses to the ACCESS survey. Respondents could indicate whether or not they were Hispanic/Latino and mark all options that applied for race (White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Other). An indicator variable was created for race and ethnicity categorizing white, non-Hispanic into one group and all other races and ethnicities into another.

Health Insurance

Health insurance status at the time of the survey (Yes, No) was self-reported in the ACCESS survey and included in our analyses.

Mode of Survey Completion

A portion of the study sample (8%) completed the survey over the phone (N=155). A dichotomous variable indicating the mode of survey completion was added to the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

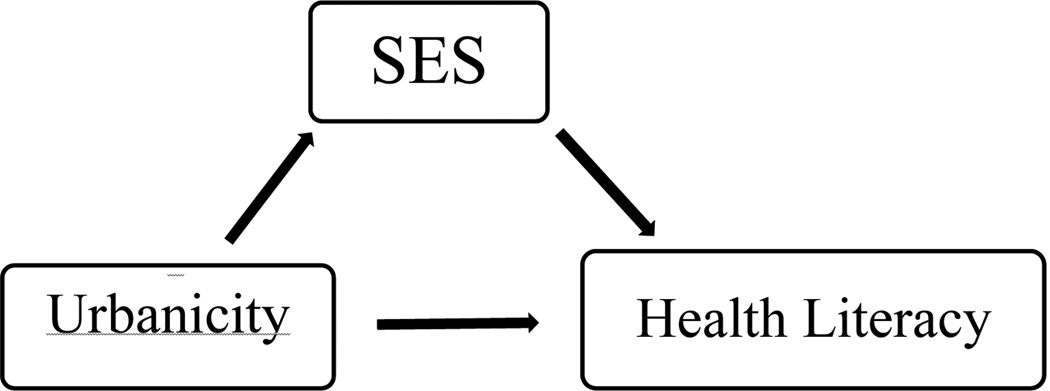

We computed descriptive statistics to characterize the study sample overall and by urbanicity level. The mixed urban-rural group was considered the reference category for our analysis. Mediation analysis was used to examine the relationship between urbanicity, health literacy, and sociodemographic characteristics (Figure 3). Mediation is a 3-variable system with 2 causal paths that feed into or impact the outcome (Figure 3).27, 28 There are 3 conditions that must hold in order for mediation to occur: 1) variations in the independent variable (urbanicity) account for variations in the supposed mediator(s) (education and income); 2) variations in the mediator(s) (education, income) account for variations in the dependent variable (health literacy); 3) when the mediators (education and income), are controlled for, a formerly significant relationship between the independent variable (urbanicity) and the dependent variables (health literacy) is significantly attenuated or no longer significant. Perfect or full mediation is indicated by the independent variable having no effect on the outcome after controlling for the mediator(s).

Figure 3.

Mediation effect of socioeconomic status (SES) on the relationship of urbanicity and health literacy.

Following the framework described above, we conducted 3 sets of statistical analyses to test for mediation. First, chi-square tests were conducted to test the association between urbanicity and the hypothesized mediators, education and income.27 Second, multivariable logistic regression models were conducted to assess the association between the potential mediators and health literacy (partially adjusted model 1) and the association between urbanicity and health literacy (partially adjusted model 2). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Health literacy was the dependent variable, and age, sex, cancer site, cancer stage, race/ethnicity, health insurance, and mode of survey completion were included as control variables. Finally, a “fully adjusted” multivariate regression model was estimated by adding income and education to the list of predictors.

Respondents with missing data on health literacy, race, ethnicity, and health insurance were excluded from the analytical sample. Models were refitted to all data with missing variables imputed using multivariate logistic regression. Ten data sets with imputed values for variables with missing observations were generated. Correct parameter estimates and standard errors were produced by averaging estimates across imputations, averaging the estimation variance across data sets, and adding the variance in the estimators across data sets. Imputed variables included health literacy (n=126), income (n=229), education (n=40), race (n=4), ethnicity (n=26), and health insurance (n=15). Stage of cancer was not available for 7 of the respondents. These were excluded from the analytical sample and the imputed models. The results of the analysis with and without imputation of missing values did not significantly change. Hence, the results from the non-imputed model are reported in this paper.

All analyses were conducted in SAS software, Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic, clinical, and health literacy characteristics of the study sample overall and by level of urbanicity. The final analytical sample included 1,682 cancer patients (50.5% females) with an average age of 63 years (standard deviation [SD]=10.6). Fifty-six percent of the analytical sample was classified as having low health literacy (Table 1). The racial and ethnic composition of the sample is mostly white, non-Hispanic (92.9%), reflecting the population of the state. Race and ethnicity differed across level of urbanicity with racial and ethnic minorities living mostly in urban areas (52.9%) versus mixed urban-rural areas (33.6%) or rural areas (13.5%, χ2=134.7, df.=2, P < .0001). Breast cancer (33.5%) accounted for the largest portion of cancer patients in the sample, with lung cancer (8.4%) representing the smallest category. Cancer type did not differ significantly across level of urbanicity (χ2=9.8, df=6, P = .13). The extent of disease at first diagnosis for the majority of cancer patients was Stage 1 (65.6%), followed by Stage 2 (32.7%) and other stages (1.7%). There were differences in cancer stage across place of residence (χ2=9.4, df=4, P = .05). The majority of the sample had private, public, or some combination of public and private health insurance at the time of the survey (97.4%). Mode of survey completion (phone vs mail) differed across place of residence. Of those who completed the survey over the phone (8.3%), 22.3% reside in Milwaukee county, 43.9% reside in the mixed urban-rural areas, and 33.8% reside in rural areas (χ2=8.9, df=2, P = .01). Health insurance coverage did not differ across place of residence (χ2=2.61, df=2, P = .27).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Health Literacy Characteristics of Cancer Patients by Place of Residence, Wisconsin, 2006–2007.

| Rural (N=489) |

Mixed (N=929) |

Urban (N=264) |

All (N=1,682) |

Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Site (%) | |||||

| Lung | 10.2 | 6.8 | 10.6 | 8.4 | .13 |

| Prostate | 29.2 | 31.2 | 29.6 | 30.4 | |

| Breast | 30.7 | 34.9 | 34.0 | 33.5 | |

| Colorectal | 29.9 | 27.1 | 25.8 | 27.7 | |

| Cancer Stage (%) | |||||

| Stage 1 | 61.5 | 68.3 | 63.6 | 65.6 | .05 |

| Stage 2 | 35.8 | 30.3 | 35.2 | 32.7 | |

| Stage Unknown | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.7 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 96.7 | 95.7 | 76.1 | 92.9 | <.0001 |

| Other | 3.3 | 4.3 | 23.9 | 7.1 | |

| Health Insurance (%) | |||||

| No | 1.8 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 2.6 | .27 |

| Yes | 98.2 | 97.4 | 96.2 | 97.4 | |

| Survey Mode (%) | |||||

| 90.4 | 93.4 | 88.3 | 91.7 | .01 | |

| Phone | 9.6 | 6.6 | 11.7 | 8.3 | |

| Age at diagnosis, Mean (SD) | 62.9 (10.6) | 62.7 (10.6) | 62.8 (11.0) | 62.8 (10.6) | .95b |

| Sex (%) | |||||

| Males | 52.2 | 49.5 | 44.7 | 49.5 | .14 |

| Females | 47.8 | 50.5 | 55.3 | 50.5 | |

| Education (%) | |||||

| Advanced Degree | 6.9 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 10.1 | .002 |

| 4 years college | 11.7 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 13.5 | |

| 1–3 years college | 20.7 | 22.5 | 26.1 | 22.5 | |

| 12 years | 46.8 | 41.0 | 34.9 | 41.7 | |

| ≤ 11 years | 13.7 | 9.7 | 11.4 | 11.1 | |

| Missing | 0.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | |

| Income (%) | |||||

| >$100,000 | 6.1 | 12.2 | 8.7 | 10.1 | <.0001 |

| $50–99,999 | 19.2 | 26.7 | 24.6 | 13.5 | |

| $30–49,999 | 24.6 | 24.4 | 17.8 | 22.5 | |

| $15–29,999 | 24.8 | 18.1 | 24.2 | 41.7 | |

| <$15,000 | 14.3 | 8.2 | 14.4 | 11.1 | |

| Missing | 11.0 | 10.4 | 10.3 | 1.1 | |

| Health Literacyc (%) | |||||

| Low | 61.4 | 53.9 | 54.9 | 56.2 | .02 |

| High | 38.6 | 46.1 | 45.1 | 43.8 |

Results based on χ2 test, except where indicated otherwise

Results based on ANOVA

High health literacy equals a score of 20 on a scale of 1–20. Low health literacy includes those with a score < 20.

Results from Tables 1 and 2 suggest a mediation effect of socioeconomic status (education and income) on the relationship between health literacy and urbanicity. Table 1 shows the relationship between urbanicity and the hypothesized mediators. Results from chi-square tests indicated a significant relationship between socioeconomic status and urbanicity with differences in income (χ2=46.7, df=10, P = <.0001) and education (χ2=26.9, df=10, P = .002) between urbanicity groups. In general, these differences showed that income and education are lower among rural cancer patients compared to their counterparts in the urban and mixed urban-rural groups. The relationship between urbanicity (independent variable) and health literacy (dependent variable) is also shown in Table 1. Approximately 54.9% of cancer patients residing in urban areas, 53.9% residing in mixed rural-urban areas, and 61.4% residing in rural areas were classified as having low health literacy. Low health literacy scores were more common in rural areas than in mixed urban-rural and urban areas (χ2=7.3, df=2, P = .02).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) of Low Health Literacy According to Place of Residence, With and Without Controlling for Socioeconomic Status, Among Cancer Patients, Wisconsin, 2006–2007. (N=1,682)

| Partially Adjusted Model 1 | Partially Adjusted Model 2 | Fully Adjusted Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Cancer Site | |||||||||

| Breast | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||

| Lung | 1.05 | 0.67–1.64 | .81 | 1.15 | 0.75–1.78 | .50 | 1.05 | 0.67–1.65 | .82 |

| Prostate | 0.74 | 0.48–1.15 | .18 | 0.68 | 0.45–1.04 | .07 | 0.74 | 0.48–1.15 | .18 |

| Colorectal | 0.86 | 0.62–1.19 | .37 | 0.92 | 0.67–1.26 | .61 | 0.86 | 0.62–1.19 | .37 |

| Cancer Stage | |||||||||

| Stage 1 | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||

| Stage 2 | 1.09 | 0.86–1.38 | .47 | 1.19 | 0.95, 1.50 | .12 | 1.08 | 0.86, 1.38 | .49 |

| Unknown | 0.80 | 0.36–1.77 | .59 | 0.78 | 0.37, 1.66 | .52 | 0.79 | 0.36, 1.74 | .56 |

| Race, Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||

| Other | 1.11 | 0.73–1.68 | .60 | 0.80 | 0.53, 1.20 | .28 | 1.08 | 0.71, 1.67 | .69 |

| Health Insurance | |||||||||

| Yes | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||

| No | 0.75 | 0.37–1.53 | .43 | 2.20 | 1.11–4.35 | .02 | 1.35 | 0.66–2.75 | .40 |

| Survey Mode | |||||||||

| 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | ||||

| Phone | 1.11 | 0.76–1.68 | .56 | 1.05 | 0.73, 1.51 | .78 | 1.12 | 0.77–1.63 | |

| Age at diagnosis | |||||||||

| Over 65 | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||

| ≤ 65 | 1.05 | 0.83–1.32 | .66 | 0.69 | 0.56–0.84 | .0003 | 1.04 | 0.82–1.30 | .72 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||

| Male | 1.79 | 1.26–2.53 | .001 | 1.71 | 1.23, 2.39 | .001 | 1.77 | 1.25, 2.51 | .001 |

| Urbanicity | |||||||||

| Mixed Urban-Rural | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||||

| Rural | 1.33 | 1.06, 1.67 | .01 | 1.14 | 0.90, 1.45 | .26 | |||

| Urban | 0.98 | 0.73, 1.32 | .92 | 1.01 | 0.74, 1.36 | .95 | |||

| Education | |||||||||

| Advanced Degree | 1 | (ref) | |||||||

| 4 years of college | 1.11 | 0.73–1.68 | .62 | 1 | (ref) | ||||

| 1–3 years of college | 1.46 | 0.98–2.15 | .05 | 1.10 | 0.72–1.68 | .64 | |||

| 12 years | 2.18 | 1.49–3.19 | <.0001 | 1.45 | 0.98–2.14 | .05 | |||

| ≤ 11 years | 4.18 | 2.50–6.97 | <.0001 | 2.17 | 1.48–3.17 | <.0001 | |||

| Missing | 2.97 | 0.97–9.07 | .05 | 4.14 | 2.48–6.9 | <.0001 | |||

| 3.05 | 1.00–9.30 | .04 | |||||||

| Income | |||||||||

| >$100,000 | 1 | (ref) | 1 | (ref) | |||||

| $50–99,999 | 1.06 | 0.72–1.56 | .74 | 1.05 | 0.72–1.55 | .76 | |||

| $30–49,999 | 1.42 | 0.95–2.14 | .08 | 1.40 | 0.93–2.11 | .10 | |||

| $15–29,999 | 2.16 | 1.39–3.34 | .0005 | 2.11 | 1.36–3.27 | .0008 | |||

| <$15,000 | 2.30 | 1.38–3.84 | .001 | 2.24 | 1.34–3.75 | .002 | |||

| Missing | 2.12 | 1.31–3.44 | .002 | 2.08 | 1.28–3.38 | .002 | |||

Model 1: Relationship between SES and Health Literacy. Model 2: Relationship between health literacy and urbanicity

Table 2 reports findings from 3 multivariate models: partially adjusted Model 1, partially adjusted model 2, and a fully adjusted model. All of the models include cancer site, cancer stage, race/ethnicity, health insurance, survey mode, age at diagnosis, and sex as control variables. Results from Model 1 show a significant relationship between the hypothesized mediators (education and income) and health literacy without the effect of the main predictor (urbanicity) included. The odds of low health literacy increased as the levels of education decreased. In the partially adjusted Model 2 (Table 2) rural cancer patients had 33% (OR 1.33, 95% CI: 1.06–1.67) higher odds of being in the low health literacy group than the mixed urban-rural cancer patients. Cancer patients in urban areas were not significantly different from those in mixed urban-rural areas in terms of their likelihood to have low levels of health literacy. Male cancer patients had 1.71 (95% CI: 1.23–2.39) times higher odds of having low health literacy than female patients. Patients aged older than 65 also had 1.44 (95% CI: 1.18–1.77) times higher odds of being in the low health literacy group than patients 65 and under. Cancer site, cancer stage, mode of survey completion, race, and ethnicity were not significantly related to the level of health literacy in this model.

In the fully adjusted model (including urbanicity, education and income levels, and the other control variables), differences in health literacy by urbanicity (Rural: 1.14, 95% CI 0.90–1.45) were attenuated. This supports the notion that the effects of urbanicity on health literacy may be fully mediated by education and income differences across urbanicity levels (Table 2).

In general, the odds of having low health literacy were greater among cancer patients with lower levels of education and income. Based on the fully adjusted model, cancer patients with at least a high school education or equivalent had 2.17 higher odds of low health literacy (95% CI: 1.48–3.17) and those with less than a high school education had a 4.14 (95% CI: 2.48–6.9) times higher odds of low health literacy than those with an advanced degree. Compared to those with an annual household income of greater than $100,000, cancer patients earning $15,000–29,999 per year have 2.11 times higher odds of low health literacy (95% CI: 1.36–3.27) and those earning less than $15,000 per year have a 2.24 higher odds of low health literacy (95% CI: 1.34–3.75). Men continued to have 1.77 times (95% CI: 1.25–2.51) higher odds of low health literacy scores than women in the fully adjusted model. Differences between cancer patients by age group disappeared after adjusting for education and income.

DISCUSSION

This study indicates that cancer patients living in rural areas are more likely than those in mixed urban-rural areas to have low levels of health literacy. These differences were attenuated after accounting for level of education and income. Urban and mixed-urban cancer patients had similar odds of reporting low health literacy regardless of the inclusion of education and income in the statistical models. The relationship between education, income, and low health literacy persisted after controlling for urbanicity. As income and education levels decreased, the odds of having low health literacy increased.

These results have important implications for health care delivery in rural areas. First, the relationship between rural residence and lower health literacy suggests cancer patients in rural areas may be more likely to struggle with understanding medical information, filling out health forms, and taking medications appropriately. As a result, their quality of life and management of their health may be compromised.1, 5, 11 Second, these findings elucidate the mechanism through which urbanicity may affect health literacy. Specifically, they suggest that the greater prevalence of low health literacy in rural areas may be related to the greater concentration of patients with lower levels of income and education in these areas.

Our study showed that the distribution of income and education differed across level of urbanicity in Wisconsin and suggested that differences in these socioeconomic variables may constrain rural cancer patients’ ability to obtain or maintain the “constellation of skills” needed to navigate the health care environment. Disparities in socioeconomic variables and health literacy could translate into poorer health outcomes and quality of life for cancer patients living in rural areas.

Consistent with previous studies, our findings also indicate that gender, age, and health insurance were significant predictors of low health literacy.1, 2, 13 Regardless of place of residence, male and older cancer patients had higher odds of having low health literacy than females and younger patients. These results suggested the importance of considering health literacy as a barrier for cancer patients in these particular groups. The association between health insurance and health literacy disappeared after adjusting for education and income. This could reflect high collinearity between these 3 and/or a confounding effect.

Implications

Research indicates that low health literacy is associated with poor health status and higher all-cause mortality among seniors, lack of health insurance coverage, and increased use of emergency care and hospitalizations.1–3, 5 Limited ability to take medications, interpret medication labels, and understand health messages is particularly important in the management of chronic and/or complex diseases that require patients to utilize numerous health literacy skills on a daily basis.3, 5 Cancer treatment often requires interacting with multiple providers, making important treatment decisions, and observing, monitoring, and contending with a wide array of physical and emotional symptoms.5, 29 Health literacy is affected by several mechanisms including the literacy skills of the patient, the ability to maneuver within the health care environment and the clinical encounter, and the communication skills of the provider.10, 30 Research indicates that cancer patients may not be able to accurately understand their likelihood of survival or intent of treatment (curative vs palliative).31 Low health literacy and/or suboptimal provider communication could hinder cancer patients’ understanding of their disease, treatment, and subsequent decisions related to their health and care.5 Given the higher prevalence of cancer patients with low health literacy in rural areas, our results underscore the need to design cancer services in these regions with health literacy in mind.

Several identified best or recommended practices to reduce barriers due to low health literacy include patient navigation interventions, adoption of health literacy best practices into patient care, improving patient-provider communication, checking understanding of care with “teach-back,” and using plain language to explain health information.30 The results reinforce the need to increase awareness of patients’ health literacy among current and future health professionals and to develop easy-to-understand health materials.10, 29, 32 Although our study suggests that low health literacy is more common among males, older patients, and those with lower socioeconomic status, it is important to note that even the most savvy patients may have trouble navigating the health system or interpreting medical information when receiving a cancer diagnosis and/or undergoing treatment. Hence, interventions to reduce health literacy barriers may be beneficial for all patients, health literacy levels notwithstanding.29

National policies and initiatives, such as Healthy People 2020 and the US Department of Health and Human Services’ National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy are setting goals and standards for incorporating health literacy best practices into patient care.34 Improving health literacy has been made a priority of quality care by the Institute of Medicine and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.10, 33, 34 Resources such as the Universal Precautions Health Literacy Toolkit are currently available and can assist health care providers with the adoption of health literacy best practices and the reduction of health literacy barriers in health care facilities.30, 35 Results from our study highlight the importance of incorporating these initiatives particularly into cancer care and in rural areas.

The findings overall indicate that larger structural factors of income and education may drive the differences in health literacy observed among rural, mixed urban-rural, and urban populations. Focusing on the intersection of these structural components with the individual environment and experience of cancer care would be a positive step in addressing disparities among rural cancer patients.36 It may be difficult to adequately identify patients with low health literacy in a clinical environment. Therefore using a “universal design” approach and adopting policies that reduce health literacy barriers for all cancer patients, regardless of literacy level, will benefit patients and families interacting with the health system.35

Limitations

Measures of health literacy, education, and income in our study are based on self-report and could be subject to several biases, including social desirability. Use of a written survey may exclude cancer patients with very low literacy. Three health literacy questions in this study are relatively established measures of health literacy and have been validated against quantitative health literacy assessments (STOFHLA, REALM). These questions have been found to be a reliable assessment of health literacy as it pertains to reading, writing, and understanding written health information.22, 23 A new question about taking medications properly was added to reflect an area in which patients with low health literacy often struggle.3, 37, 38 This question has not been validated; however, previous research shows that appropriate medication adherence and medication errors are areas of concern among patients taking multiple medications.3, 38, 39 Comprehension of verbal instructions and ability to navigate the health care system were not assessed in this study. The questions may identify disparities in different health literacy skills rather than differences in a unified construct of health literacy. The cut-off score is 19, so a comparison of very low literacy to very high literacy is not being made. Rather, our approach tries to maximize the sensitivity of our measure and aim to identify cancer patients with any level of health literacy difficulty versus those with no difficulties at all.23–25 This is consistent with recommendations from previous studies suggesting that individuals scoring in the middle or marginal health literacy groups may also need assistance in communication with health care providers and should therefore be included in the low health literacy group.24, 25 Sensitivity analyses were conducted using different arrangements of the health literacy variable (eg, selecting only a subset of questions, comparing those with the highest vs lowest scores, comparing those in the 25th vs 75th quartiles of the composite score). Analyses were also conducted for each individual question and its association with urbanicity. Bivariate analyses show a consistent pattern of results of lower health literacy among rural cancer patients for 2 of the questions (individual and combined) “How often can you fill out medical forms by yourself” and “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information,” indicating differences in these health literacy areas for rural cancer patients. There was no effect between urbanicity and the remaining questions. The sensitivity analyses were consistent with the original model in that socioeconomic status mediated the relationship between the various versions of the health literacy measure and the level of urbanicity, thus supporting the internal validity of our findings. We had 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.7 for the direct effect of rural residence on health literacy. The odds ratios for the mediating variables were larger than we could have detected for the remaining effect of urbanicity. Although there may be a weak remaining effect of mixed urban-rural versus rural that we could not detect due to power limitations, that effect would be weak and smaller than the effects we have detected for socioeconomic status (income and education).

The measures of urbanicity may not reflect the distance from more populous parts of the state or the allocation of health care resources. The median age of the sample is 64, an age where many of the respondents could be retired. Therefore, annual household income may not accurately reflect study participants’ total financial resources. The data collected were cross-sectional; consequently migration in and out of rural areas over the life course was not assessed and causality cannot be inferred. Finally, data are restricted to the state of Wisconsin and the results may not generalize to other US regions with different patterns of urbanicity.

CONCLUSIONS

Rural cancer patients have higher odds of having lower health literacy and this association appears to be mediated by lower income and education levels. Lower health literacy may result in poor health outcomes among rural cancer patients and contribute to disparities in cancer care. This study is unique as it uses a population-based, statewide sample allowing a more representative picture of health literacy among cancer patients in a large geographic area. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between urbanicity and health literacy in a population-based sample of cancer patients as well as the sociodemographic variables that mediate this relationship. This study suggests that cancer patients in rural areas disproportionately experience health literacy barriers. Additional resources, interventions, and research addressing health literacy barriers may benefit cancer patients in rural areas and mitigate health literacy disparities.

Human Participant Protection

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health through the Wisconsin Partnership Program - Reducing Cancer Disparities through Comprehensive Cancer Control, the UW Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. We would like to thank John Hampton for his assistance with the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. [Accessed September 9, 2011];The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf. Published September 2006.

- 3.Amalraj S, Starweather C, Nguyen C, Naeim A. Health literacy, communication, and treatment decision-making in older cancer patients. Oncology. 2009;23(4):369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:204–211. doi: 10.1370/afm.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koay K, Schofield P, Jefford M. Importance of health literacy in oncology. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2012;8:14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herndon J, Chaney M, Carden D. Health literacy and emergency department outcomes: A systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;57(4):334–345. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeWalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson J, Baker DW. In search of ‘low health literacy’: Threshold vs. gradient effect of literacy on health status and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1335–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, editors. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: Committee on Health Literacy, Institute of Medicine; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association Health literacy: report of the Council on Scientific Affairs. JAMA. 1999;281(6):552–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, Parker RM, Glass J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;53(3):134–149. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett CL, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, et al. Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3101–3104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin LT, Ruder T, Escarce JJ, et al. Developing predictive models of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1211–1216. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1105-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jemal A, Ward E, Wu X, Martin HJ, McLaughlin CC, Thun MJ. Geographic patterns of prostate mortality and variations in access to medical care in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(3):590–595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loberiza FR, Cannon AJ, Weisenburger DD, et al. Survival disparities in patients with lymphoma according to place of residence and treatment provider: A population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5376–5382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coughlin SS, Thompson TD, Hall I, Logan P, Uhler RJ. Breast and cervical carcinoma screening practices among women in rural and nonrural areas of the United States, 1998–1999. Cancer. 2002;94(11):2801–2812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinney AY, Harrell J, Slattery M, Martin C, Sandler RS. Rural-urban differences in colon cancer risk in blacks and whites: The North Carolina colon cancer study. J Rural Health. 2006;22(2):124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lengerich EJ, Tucker TC, Powell RK, et al. Cancer incidence in Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia: Disparities in Appalachia. J Rural Health. 2005;21(1):39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shugarman LR, Sorbero ME, Tian H, Jain AK, Ashwood JS. An exploration of urban and rural differences in lung cancer survival among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Public Health. 2008;90(7):1280–1287. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Mangan P, et al. Geographic disparities in cervical cancer mortality: What are the roles of risk factor prevalence, screening, and use of recommended treatment? J Rural Health. 2005;21(2):149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh MC, Trentham-Dietz AT, Schroepfe A. Cancer information sources used by patients to inform and influence treatment decisions. J Health Commun. 2010;15(4):445–463. doi: 10.1080/10810731003753109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powers BJ, Trinh JV, Bosworth HB. Can this patient read and understand written health information? JAMA. 2010;304(1):76–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B. The single item literacy screener: Evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Family Practic. 2006;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. [Accessed September 9, 2011];County Health Rankings 2011. [Report] Available at: http://uwphi.pophealth.wisc.edu/programs/match/wchr/2011/CHR2011_WI.pdf.

- 27.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;31(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Rev. 1993;17(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudd R, Keller D. Health literacy: New developments and research. J Commun Healthcare. 2009;2(3):240–257. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeWalt DA, Callahan LF, Hawk VH, et al. [Accessed September 9, 2011];Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. Available at: http://www.nchealthliteracy.org/toolkit/toolkit_w_appendix.pdf. Published April 2010.

- 31.Zafar SY, Alexander SC, Weinfurt KP, Schulman KA, Abernethy AP. Decision making and quality of life in the treatment of cancer: A review. Support Cancer Care. 2009;17:117–127. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sand-Jecklin K, Murray B, Summers B, Watson J. Educating nursing students about health literacy: From the classroom to the patient bedside. [Accessed February 15, 2012];OJIN. 2010 15(3) Available at: http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol152010/No3-Sept-2010/Articles-Previously-Topic/Educating-Nursing-Students-about-Health-Literacy.html. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. [Accessed September 9, 2011];HR 3590 111th Cong (2009) In GovTrack.us (database of federal legislation). Available at: http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h111-3590.

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed September 9, 2011];National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. 2010 Available at: http://www.health.gov/communication/hlactionplan/pdf/Health_Literacy_Action_Plan.pdf.

- 35.DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, et al. Developing and testing the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59(2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reifsnider E, Gallagher M, Forgione B. Using ecological models in research on health disparities. J Prof Nursing. 2005;21(4):216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puts MTE, Costa-Lima B, Monette J, et al. Medication problems in older, newly diagnosed cancer patients in Canada: How common are they?: A prospective pilot study. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(6):519–536. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200926060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, et al. To err is human: Patient understanding of prescription drug label instructions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]