Abstract

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) integrates growth factor signals with cellular nutrient and energy levels and coordinates cell growth, proliferation and survival. A regulatory network with multiple feedback loops has evolved to ensure the exquisite regulation of cell growth and division. Colorectal cancer is the most intensively studied cancer because of its high incidence and mortality rate. Multiple genetic alterations are involved in colorectal carcinogenesis, including oncogenic Ras activation, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway hyperactivation, p53 mutation, and dysregulation of wnt pathway. Many oncogenic pathways activate the mTOR pathway. mTOR has emerged as an effective target for colorectal cancer therapy. In vitro and preclinical studies targeting the mTOR pathway for colorectal cancer chemotherapy have provided promising perspectives. However, the overall objective response rates in major solid tumors achieved with single-agent rapalog therapy have been modest, especially in advanced metastatic colorectal cancer. Combination regimens of mTOR inhibitor with agents such as cytotoxic chemotherapy, inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor receptor and Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitors are being intensively studied and appear to be promising. Further understanding of the molecular mechanism in mTOR signaling network is needed to develop optimized therapeutic regimens. In this paper, oncogenic gene alterations in colorectal cancer, as well as their interaction with the mTOR pathway, are systematically summarized. The most recent preclinical and clinical anticancer therapeutic endeavors are reviewed. New players in mTOR signaling pathway, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and metformin with therapeutic potentials are also discussed here.

Keywords: Mechanistic target of rapamycin pathway, Colorectal cancer, Mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitor, Chemotherapy, Drug resistance

Core tip: Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway serves as a central regulating axis that coordinates cell growth and proliferation. Single-agent mTOR inhibition therapy, however, has provided only limited therapeutic efficacy towards colorectal cancer. Blocking compensatory pathways and multiple feedback loops is considered the challenge. Combination regimens are being intensively tested in clinic. This review summarizes extensive studies describing crosstalk between mTOR pathway and major oncogenic pathways contributing to colorectal cancer development and novel combinational strategies targeting the mTOR pathway in treating colorectal cancer are also introduced.

INTRODUCTION

The signaling pathway of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), regulates cell growth and proliferation largely by promoting key anabolic processes, by sensing nutrition levels and growth factors, as well as various environmental cues[1,2]. The mTOR pathway is conserved in organisms from yeast to human. The central protein, mTOR, is an atypical serine/threonine protein kinase that belongs to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-related kinase family. mTOR interacts with several proteins to form two distinct complexes, known as mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and complex 2 (mTORC2). Both complexes share a DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR), a mammalian lethal with sec-13 protein 8 (mLST8, also known as GbL)[3] and Tti1/Tel2[4]. Regulatory-associated protein of mammalian target of rapamycin (raptor)[5] and proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa (PRAS40)[6] are unique to mTORC1 and rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (rictor)[7], mammalian stress-activated MAP kinase-interacting protein 1 (mSin1)[8] and protein observed with rictor 1 and 2 (protor1/2)[9] are specific to mTORC2. mTOR is the target of rapamycin (or sirolimus), but only mTORC1 is sensitive to rapamycin inhibition upon FKBP12-rapamycin binding[10]. Rapamycin also inhibits the mTORC1 downstream targets differently[11]. mTORC1 plays a pivotal role in regulating protein and nucleotide synthesis by signaling through its main effectors, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and eIF4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1). S6 ribosomal protein, a component of the 40S ribosomal subunit, is the best characterized S6K1 substrate and a major effector of cell growth. Phosphorylated 4E-BP1 binds to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), which is an important component of the pre-initiation eIF4F complex and prevents the complex from binding with the 5’ end cap structure on messenger RNAs of proteins essential for the cell cycle progression, functioning as a rate-limiting factor in cap-dependent translation initiation. mTORC1 promotes de novo lipid synthesis by regulating Lipin-1 and SREBP1/2, and it promotes energy metabolism by positively regulating cellular metabolism and ATP production through activation of HIF1α and suppresses autophagy through ULK1 (unc-51-like kinase 1) and Atg13 (mammalian autophagy-related gene 13). mTORC2 phosphorylates protein kinase B (Akt/PKB), serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1), and protein kinase C-α (PKCα), regulating cell survival, metabolism, and cytoskeletal organization[12]. Multiple feedback loop mechanisms add to the complexity of the mTOR signaling pathway[13].

mTORC1 integrates intracellular and extracellular signals--growth factors, stress, energy status, oxygen, and amino acids--mainly through the TSC1-TSC2 (hamartin-tuberin) complex. The TSC1/2 complex functions as a GAP (GTPase-activating protein) for the Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb), of which the GTP-bound form activates mTORC1. The TSC1/2 complex relays signals from upstream regulators that sense environmental growth signals and nutrition levels. TSC1 protects TSC2 from ubiquitin degradation[14]. In response to growth signals, multiple effectors phosphorylate TSC2, including Akt, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), and ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK1), thereby promoting mTOR signaling activation.

The TSC1/2 complex also responds to diverse stress signals. Upon hypoxia or low ATP state, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylates TSC2 and enhances its GAP activity toward Rheb[15]. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 3 (MAP4K3)[16], mammalian vacuolar protein sorting 34 homolog (hVPS34)[17] and inositol polyphosphate monokinase (IPMK)[18] are reported as amino acid sensing proteins. However, our understanding of the mechanisms by which mTOR senses amino acids through the v-ATPase (vacuolar H+-ATPase)-Ragulator (LAMTOR1-3)-Rag GTPase complex has evolved greatly in recent years. Four Rag proteins, RagA to RagD, form heterodimers: RagA with RagB, and RagC with RagD. When RagA/B is bound to GTP, RagC/D is bound to GDP, and vice versa. Amino acids promote GTP loading of RagA/B, thus enabling the heterodimer to interact with raptor. Ragulator binds with Rag GTPases and translocates to the lysosome surface, where mTORC1 interacts with GTP bound Rheb. v-ATPase locates on the lysosomal membrane interacts with Ragulator to relay the amino acid level signals from the lysosomal lumen[19-22].

KEY COLORECTAL CARCINOGENESIS PATHWAYS AND THEIR INTERACTION WITH THE mTOR PATHWAY

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with more than one million cases annually. CRC caused almost 0.7 million death in 2012 globally[23]. It is the second most deadly cancer among adults in the United States[24]. In approximately 75% of cases, the cancer are confined within the wall of the colon (stage I and II), or only spreads to regional lymph nodes (stage III). These stages of cancer are mostly curable by surgical excision combined with chemotherapy. However, in about 20% of cases, the tumors metastasize to distant sites and are usually inoperable and incurable, with only a 12% 5-year relative survival rate[25,26]. Approximately 75%-80% of colorectal tumors develop in a sporadic manner[27]. An over-simplified model that generalizes the genetic cause of colorectal carcinogenesis is one where microsatellite instability (MSI) contributes to 85% of CRC, while the remaining 15% arise from chromosomal instability (CIN). However, some studies have shown that the MSI and CIN pathways are not mutually exclusive in CRC and considerable crosstalk exists between various pathways[28]. The “canonical” colorectal carcinogenesis model, that the carcinomas arise from pre-existing adenomas, was proposed in 1990 by Fearon and Vogelstein[29]. This model describes approximately 80%-90% of CRC and it is still accepted, despite a large body of new information on CRC that has emerged during the last two decades. In this model, the accumulation of genetic alterations, such as APC, p53, DCC, and K-ras, enable colorectal carcinogenesis, as well as histological malignancy progression[27].

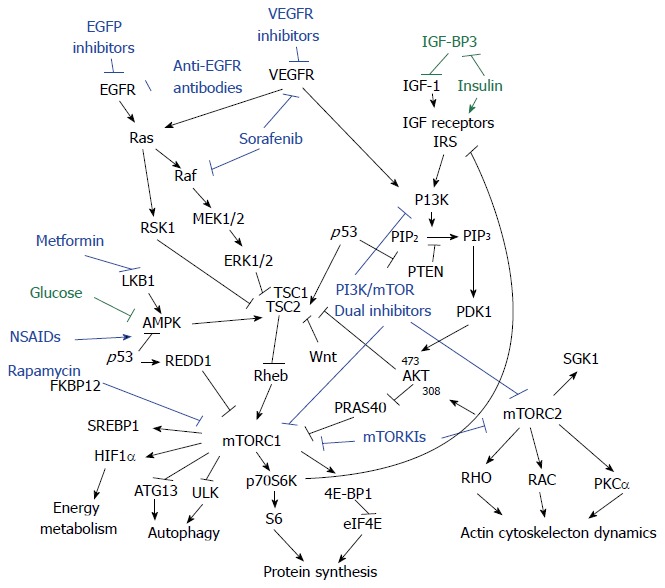

Many of the genetic pathways involved lie upstream of mTOR, and the oncogenes affected elicit part of their oncogenic effect through the mTOR signaling pathway[30]. The interaction between mTOR signaling and other important pathways involved in colorectal carcinogenesis are reviewed here (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Crosstalk between mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway and colorectal oncogenic pathways. PI3K/AKT and Ras/MAPK pathways are the major upstream mediators of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Therapeutic efforts for colorectal cancer targeting mTOR signaling include Rapamycin (or Rapalogs) inhibition as well as mTOR kinase inhibition, plus in combination with blockage of growth factor receptors, and components in upstream pathways such as Raf and PI3K, etc. New players regulating the mTOR pathway such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) and metformin merit further investigation. IGF: Insulin like growth factor; SGK1: Serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase; PRAS40: Proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa; TSC1: Tuberous sclerosis-1; TSC2: Tuberous sclerosis-2; AMPK: Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; eIF4E: Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E; RSK1: Ribosomal S6 kinase.

Wingless/wnt pathway

Aberrant crypt foci (ACF) is considered the first identifiable precursor lesion in colorectal tissue[31]. ACF derives from epithelial cells in the lining of the colon and rectum and can develop into adenomatous polyps, which could potentially progress to adenocarcinoma[32]. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor gene normally suppresses the Wnt pathway by actively degrading β-catenin and inhibits its nuclear localization[33]. A close link between β-catenin signaling and the regulation of VEGF-A expression was observed in human CRC, indicating the role of β-catenin in CRC angiogenesis[34]. β-catenin was also shown to induce cyclin D1 in CRC cells, which contributes to neoplastic transformation[35]. Aberrant, mutant APC or APC loss can cause constitutive activation of the Wnt pathway, which is considered the initiating event in colorectal cancer. APC mutation can cause more than 100 adenomatous polyps[36-38]. The Wnt signaling pathway stimulates the TSC-mTOR pathway[39]. mTOR signaling, as well as the mTOR protein level, was observed to be elevated in ApcΔ716 mice. Inhibition of the mTORC1 pathway by treating the APC mutant mice with RAD001 (everolimus) was reported to suppress intestinal polyp formation and reduce the mortality of the animals[15,39].

PI3K/AKT pathways

Nutrient signals act mostly through insulin or insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling pathways. Growth factors-receptors, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), insulin like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), and cell adhesion molecules, such as integrin and G-protein-coupled receptors, activate the PI3K pathway to promote cell survival, proliferation and cell growth[40]. The activated receptor tyrosine kinases interact with PI3K, where class I PI3K family members convert phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), hence activating phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) and mTORC2. Specifically, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) reverses this process by dephosphorylating PIP3 to PIP2. IGF-BP3 binds to IGF-1 and prevents over activation of IGF-1/AKT signaling. It is currently believed that PDK1 phosphorylates AKT on Thr308, whereas mTORC2 phosphorylates AKT at Ser473. Double phosphorylation fully activates AKT activity[41]. Hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT pathway is associated with malignant behavior, including proliferation, adherence, transformation, and survival[42-45]. PI3K/PTEN/AKT pathway mutations are found in a large number of CRC cell lines[46-49]. The PIK3CA mutation is found in 15% of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC)[50]. Germline PTEN ablation is associated with Cowden syndrome, which can cause an increased lifetime risk for CRC[51,52]. Elevated protein levels of PI3K subunit p85α and AKT1/2, and phosphorylation levels of mTORSer2448 and phosphor-p70S6KThr389 have been observed in CRC patients. Notably, p85α expression was considerably higher in stage IV tumors than in earlier stages[46]. Analyzing the mechanism of GP130-mediated mTORC1 activation in mice revealed a requirement for JAK and PI3K activity in the activation of mTORC1, leading to colorectal tumorigenesis[53]. mTOR inhibition abolishes S6K phosphorylation and relieves the feedback suppression on RTK, leading to PI3K activation and, eventually, to AKT activation[54,55].

p53 pathway

p53 is considered the “guardian of the genome”. p53 mediates diverse stress signals, such as DNA damage, energy and metabolic stress, hypoxia, oxidative stress, oncogene stress and ribosomal dysfunction. Functioning as a transcription factor, p53 regulates its downstream factors to elicit its tumor suppressive functions, which include cell cycle arrest, senescence, DNA repair, and programmed cell death[56]. Under normal conditions, p53 inhibits the mTOR pathway by multiple routes. Deregulation of the p53 pathway by either mutation of the TP53 gene or by 17p chromosomal deletion is thought to be the second key step in tumorigenesis of CRC, marking the transition from adenoma to carcinoma[26,57]. p53 closely monitors the IGF-1/AKT pathways, which is an upstream regulation pathway of mTOR[58,59]. p53 induces IGF-BP3 to inhibit mitogenic signaling[60] and directly regulates the transcription of PTEN[61]. In addition, p53 induces Sestrin1/2 upon DNA damage and oxidative stress, which negatively regulates mTOR through activation of AMPK and TSC2 phosphorylation[62]. Furthermore, in colorectal cancer cell lines, p53 can suppress mTOR activity by regulating AMPK-β1 and TSC2 directly. Notably, the increased mRNA level of TSC2 by γ-irradiation-induced p53 activation can be cell type specific. However, data showed that p53-dependent induction of TSC2 exists in HCT116 cells and mouse colon tissue[63,64]. REDD1 is another p53 target gene that regulates the mTOR pathway[65]. REDD1 is regulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress. REDD1 is necessary for hypoxia induced TSC1/2 activation[66].

RAS/RAF/MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE PATHWAY

Ras is the first identified oncogene and the most frequently mutated gene in human malignancy. Ras is a small GTPase that relays signals from a subset of growth factors responsive RTK to its effector pathways, which are responsible for growth, migration, adhesion, cytoskeletal integrity, survival and differentiation. The three true Ras proteins in the RAS family that have been most studied are H-Ras, N-Ras and K-RAS[67]. The K-RAS gene is the most mutated RAS pathway member in CRC, with a 35%-45% mutation rate in mCRC, compared with BRAF 8% and NRAS 4%[50]. K-RAS mutation is thought to be a relatively early event that correlates histologically with early to late adenomas. N-RAS mutations are also observed in a small percentage of CRC[31]. The major Ras downstream pathway is the Raf-mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase-MAP kinase signal transduction pathway. Ras also indirectly signals to mTOR through its other effector pathway, the PI3K/AKT pathway[68,69]. The p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (MAPK)-ERK1/2 directly phosphorylates and inactivates TSC2[70,71]. ERK phosphorylates ribosomal protein S6, a direct effector of S6K1, stimulating cap-dependent translation[72,73]. The MAPK-activated kinase and RSK interact with and phosphorylate TSC2 at Ser-1798, thus inhibiting the tumor suppressor function of the TSC1/2 complex, resulting in increased mTOR signaling to S6K1[74].

Autophagy

It is well established that mTORC1 negatively regulates autophagy. Atg1/ULK1 are central components in autophagy, and ULK1 as a direct target of TORC1[75]. On the other hand, the role of autophagy in cancer, including colorectal cancer, can be complicated. Autophagy can contribute to cell death during chemotherapy, but could also serve as a survival mechanism for cancer cells. In fact, its function may vary in different types of tumors, as well as for various stages of cancer[76-78]. Autophagy is also reported to contribute to cancer cachexia. High level of HMGB1 was detected in the serum of CRC patients, and was associated with colorectal cancer progression. HMGBI was shown to induce autophagy in muscle tissue by reducing mTOR phosphorylation in tumors bearing mice, therefore increasing plasma free amino acid levels, providing energy source to the cancer cells[79].

Other mechanisms

The mTOR signaling pathway may have a direct effect on carcinogenesis. Elevated mTOR mRNA and protein levels, as well as Raptor and Rictor levels, are observed in CRC patient tissues. Furthermore, a good correlation between a higher malignancy stage and higher expression level was observed[80,81] mTORC1/2 are critical for CRC metastases via RhoA and Rac1 signaling[81]. Using a genetically engineered mouse model, mTOR was proposed to contribute to tumorigenesis by causing chromosomal instability[82,83].

COLORECTAL CANCER THERAPIES TARGETING THE mTOR PATHWAY

mTOR has a central role in the regulatory network sensing nutrition and growth signals, coordinating cell growth and proliferation. It has long been proposed that mTOR inhibitors may be efficacious for treating and preventing tumor progression[84-86], particularly in CRCs[87]. Tremendous efforts have been made to develop potent and effective molecules to target the mTOR pathway[88]. Efforts on targeting the mTOR pathway for CRC treatment have been reviewed extensively in previously published reviews[89,90].

Nowadays, CRC chemotherapy consists mainly of oral fluoropyrimidines, with the addition of irinotecan and oxaliplatin. The emergence of targeted monoclonal antibodies (Mabs), such as bevacizumab (Bev) (anti-VEFG-A), cetuximab and panitumumab (anti-EGFR), has provided more treatment options to extend survival and improve clinical outcomes in mCRC[91,92]. However, less than 20% of patients with mCRC respond to clinically available targeted drugs when used as monotherapy[50]. This also suggests that a better understanding of the in depth molecular alterations in CRC is needed to discover more precise and effective therapeutic targets for those CRC cases that do not respond well to current treatment paradigms.

First generation of mTOR inhibitors-rapamycin and rapalogs

Rapamycin is the first discovered natural inhibitor of mTOR. The antitumor effect of rapamycin in colorectal cancer has been demonstrated in vitro and in various mouse models[39,53,93] Rapamycin inhibits mTORC1 with high specificity; however, its hydrophobicity and poor bioavailability has made it a less than optimal antitumor agent. Rapalogs, such as temsirolimus (CCI-779), everolimus (RAD001), and ridaforolimus (AP-23573, deforolimus) confer better potency, pharmacokinetic profiles and clinical activity than rapamycin, and are thus being used in the clinic or in developing treatments for many types of cancer, mostly solid tumors[90]. Temsirolimus and everolimus are approved for treating metastatic renal cell carcinoma and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Everolimus is also approved for breast cancer therapy. However, multiple clinical trials have failed to demonstrate meaningful efficacy of everolimus in the treatment of CRC in the single agent setting[94,95]. Moreover, Rapalogs used alone are thought to be cytostatic in most tumor types and primarily stabilize clinical disease[83,86]. Deregulation of the PI3K and K-Ras signaling pathways determines therapeutic response to everolimus[96]. The central role of the PI3K/mTOR pathway in cancer biology suggests that other drug combinations showing mTOR inhibition merit evaluation. Combinational regimens consisting of Rapalogs and other antitumor agents have shown promising results[97].

Both preclinical data and clinical trials have demonstrated that combined VEGF and mTOR inhibition has greater anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor activity than either monotherapy. Bevacizumab and everolimus combined therapy was well tolerated, with prolonged stable disease in patients with refractory, metastatic colorectal cancer[98,99]. Reported side effects included risks related to mucosal damage and/or impaired wound healing[100]. The addition of a chemotherapy agent, such as doxorubicin, is also in development for advanced cancer therapy. Molecular analyses revealed an association between tumor response and a PIK3CA mutation and/or PTEN loss/mutation, suggesting further evaluation in patients with PI3K pathway dysregulation[100]. Using a xenograph tumor model, Lapatinib was shown to reduce tumor volume synergistically with everolimus, by reducing P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux of everolimus through inhibition of P-gp. This provided a new lead towards new chemotherapy in mCRC harboring K-RAS mutations[101]. The mosaic mutations in various oncogenic/tumor suppressive genes downstream of EGFRs undermines the therapeutic response of the anti-EGFR antibodies. K-RAS and BRAF mutations are associated with poor prognosis in CRC[102]. Temsirolimus has limited efficacy in chemotherapy-resistant K-RAS mutant disease, and K-RAS mutation is a negative predictive prognostic factor during mCRC treatment with anti-EGFR compounds[95,103]. Sorafenib, which is a multikinase inhibitor of Ras/MAPK signaling targeting Raf, also inhibits growth factor receptors, such as VEGFR and PDGFR. Sorafenib has been shown to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of rapamycin in CRC carrying oncogenic K-RAS and PIK3CA, in preclinical settings[104].

In a subgroup analysis of the Phase III trial, the combination of everolimus and octreotide LAR demonstrated a significant prolonged median progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with advanced colorectal neuroendocrine tumors[105]. Everolimus combined with irinotecan proved to be well tolerated in a phase I study as second-line therapy in mCRC; however, an in vitro study showed an additive effect in HT29 tumor xenografts, but not in HCT116, which both harbor BRAF/PIK3CA mutations[106].

Second generation of mTOR inhibitors-Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors and mTOR kinase inhibitors

Isolated inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin or Rapalogs proved that they were only partial inhibitors of mTORC1 and they do not have a meaningful contribution clinically in a single agent setting. Moreover, because of the release of feedback inhibition of AKT from S6K1 inhibition, a pro-survival effect derives from induced AKT activity. Inhibitors that block both the PI3K signaling pathway and mTORC1/2 have been developed and have shown greater anticancer effects than Rapalogs[107-111]. Dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors are less likely to induce drug resistance than single-kinase inhibitors. mTOR specific kinase inhibitors are expected to inhibit mTORC1 and mTORC2 simultaneously, although inhibiting mTORC1 may cause mTORC2 upstream AKT activation. Many dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitors and mTOR kinase inhibitors are under preclinical study and some have entered the clinical phase[88].

Resistance arises from simultaneous mutation in parallel pathways related to the mTOR pathway. Preclinical and clinical studies indicate that PIK3CA mutation in the absence of KRAS mutation is a predictive marker for the response to PI3K and mTOR inhibitors[109,112]. However, CRC with the KRAS activation mutation is frequently observed, and it commonly coexists with PIK3CA mutations. Coexisting mutations of KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA attenuate sensitivity to PI3K/mTOR inhibition in CRC cell lines[113,114]. Partial mTOR inhibition from rapamycin and mTOR kinase inhibitors indicates the existence of an unknown 4E-BP1 kinase that is potentially responsible for resistance in CRC[115]. The combination of a MEK inhibitor and PI3K/mTOR inhibitor was thus proposed to overcome the intrinsic resistance to MEK inhibition in CRCs[116,117]. Concomitant BRAF and PI3K/mTOR inhibition has been shown to be required for treatment of BRafV600E CRC[118].

Others

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including aspirin and selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, have been investigated for protection against CRC development[119]. Aspirin was reported to lower the risk of, and improve the survival from, colorectal cancer[120,121]. PIK3CA mutation in colorectal cancer may serve as a predictive molecular biomarker for adjuvant aspirin therapy[122]. A study showed that aspirin reduced mTOR signaling by activating AMPK; suppressed autophagy by mTOR inhibition may contribute to the antitumor effect of aspirin[123]. Indomethacin and nimesulide are also reported to reduce mTOR signaling and suppress CRC growth via a COX-2 independent pathway. These studies unveiled a novel mechanism through which COX-2 inhibitors exert their anticancer effects, as well showing protective effects against development of CRC, further emphasizing the validity of targeting mTOR signaling in anticancer therapy[124]. Additive antitumor effects with low carbohydrate diets were observed with the mTOR inhibitor CCI-779 and, especially, with the COX-2 inhibitor Celebrex[125].

A meta-analysis showed that diabetes mellitus increased risk of developing CRC[126], while metformin therapy appears to be associated with a significantly lower risk of colorectal cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes[127,128]. Metformin regulates glucose homeostasis by inhibiting liver glucose production and increasing muscle glucose uptake. A preclinical study showed that metformin inhibits insulin-independent growth and xenograft tumor growth of cells carrying the gain-of-function H1047R mutation of the PI3KCA gene, which has been shown to form diet restricted-refractory xenotumors[129], suggesting that metformin was not a bona fide diet restriction mimetic[130]. In both chemical carcinogen-induced and APC mutant colorectal carcinogenesis murine models, metformin activated AMPK and inhibited the mTOR/S6K1 pathway, leading to suppressed colonic epithelial proliferation and reduced colonic polyp formation[131,132]. These data suggest that metformin might be a safe and promising candidate for the chemoprevention of CRC.

Tandutinib inhibits several receptor tyrosine kinases, including the Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), and c-Kit receptor tyrosine kinase. Tandutinib inhibits the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway to inhibit CRC growth[133].

Curcumin, derived from the tropical plant Curcuma longa, has a long history in traditional Asian medicine. The preventive and therapeutic properties of curcumin are associated with its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties. Curcumin regulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, growth factor receptors, enzymes, adhesion molecules, apoptosis related proteins, and cell cycle proteins. Curcumin modulates the activity of several transcription factors and their signaling pathways[134]. The antitumor effect of curcumin towards CRC was mediated by modulation of Akt/mTOR signaling[135]. Another natural product, pomegranate polyphenolics, was shown to suppress azoxymethane-induced colorectal aberrant crypt foci and inflammation, possibly by suppressing the miR-126/VCAM-1 and miR-126/PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways[136].

PERSPECTIVE

Epidemiological studies indicate that lifestyle factors throughout life influence CRC incidence and prognosis[137]. For example, a large waist circumference and body mass index has been associated with CRC risk[138,139]. A plausible mechanism was proposed that ample nutrition factors such as amino acids, insulin, glucose and IGF-1 circulating in the body, constantly activates the mTOR pathway. Another study showed that hyperinsulinemia decreases IGFBP3 and consequently increases circulating IGF-1 and diabetes, both of which increase the risk of CRC[140]. CRC is a multifactorial disease. A new model: convergence of hormones, inflammation, and energy-related factors (CHIEF), proposes that various environmental agents (commensal bacteria, dietary antigens, mucosal irritants and pathogens) activate a basal, repetitive, mild subclinical inflammation, while additionally estrogen, androgens and insulin levels provoke the inflammation, which influences the CRC risk[141]. mTOR appears to be in the hub of this network. The concept of the CHIEF model agrees with the contemporary therapeutic trend, recognizing multiple parallel pathways, and suggesting that combined inhibition of multiple pathways would provide more comprehensive tumor suppression efficacy, with a better chance of overcoming resistance.

Footnotes

Supported by National Nature Science Foundation, No. 81270035; and International Cooperation Grant, No. 11410708100

P- Reviewers: Hong J, Pan CC S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howell JJ, Ricoult SJ, Ben-Sahra I, Manning BD. A growing role for mTOR in promoting anabolic metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:906–912. doi: 10.1042/BST20130041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Latek RR, Guntur KV, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. GbetaL, a positive regulator of the rapamycin-sensitive pathway required for the nutrient-sensitive interaction between raptor and mTOR. Mol Cell. 2003;11:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaizuka T, Hara T, Oshiro N, Kikkawa U, Yonezawa K, Takehana K, Iemura S, Natsume T, Mizushima N. Tti1 and Tel2 are critical factors in mammalian target of rapamycin complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20109–20116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vander Haar E, Lee SI, Bandhakavi S, Griffin TJ, Kim DH. Insulin signalling to mTOR mediated by the Akt/PKB substrate PRAS40. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:316–323. doi: 10.1038/ncb1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM. Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1296–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, Sabatini DM. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearce LR, Sommer EM, Sakamoto K, Wullschleger S, Alessi DR. Protor-1 is required for efficient mTORC2-mediated activation of SGK1 in the kidney. Biochem J. 2011;436:169–179. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng XF, Florentino D, Chen J, Crabtree GR, Schreiber SL. TOR kinase domains are required for two distinct functions, only one of which is inhibited by rapamycin. Cell. 1995;82:121–130. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thoreen CC, Sabatini DM. Rapamycin inhibits mTORC1, but not completely. Autophagy. 2009;5:725–726. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laplante M, Sabatini DM, et al. Mtor signaling. Cold Spring: Harbor Perspectives in Biology; 2012. p. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR and cancer: many loops in one pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benvenuto G, Li S, Brown SJ, Braverman R, Vass WC, Cheadle JP, Halley DJ, Sampson JR, Wienecke R, DeClue JE. The tuberous sclerosis-1 (TSC1) gene product hamartin suppresses cell growth and augments the expression of the TSC2 product tuberin by inhibiting its ubiquitination. Oncogene. 2000;19:6306–6316. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoki K, Ouyang H, Zhu T, Lindvall C, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yang Q, Bennett C, Harada Y, Stankunas K, et al. TSC2 integrates Wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by AMPK and GSK3 to regulate cell growth. Cell. 2006;126:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Findlay GM, Yan L, Procter J, Mieulet V, Lamb RF. A MAP4 kinase related to Ste20 is a nutrient-sensitive regulator of mTOR signalling. Biochem J. 2007;403:13–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byfield MP, Murray JT, Backer JM. hVps34 is a nutrient-regulated lipid kinase required for activation of p70 S6 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33076–33082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Dann SG, Kim SY, Gulati P, Byfield MP, Backer JM, Natt F, Bos JL, et al. Amino acids mediate mTOR/raptor signaling through activation of class 3 phosphatidylinositol 3OH-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14238–14243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Chang S, Gumper I, Snitkin H, Wolfson RL, Kirak O, Sabatini DD, Sabatini DM. Regulation of mTORC1 by the Rag GTPases is necessary for neonatal autophagy and survival. Nature. 2013;493:679–683. doi: 10.1038/nature11745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator is a GEF for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Cell. 2012;150:1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Globocan 2013. Cancer Fact Sheets for Colorectal Cancer. 2013. Available from: http://www.whoint/ mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/indexhtml. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2012. Cancer J Clin. 2012:62: 10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howlader N, NA, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds) Seer cancer statistics review 1975-2010. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2013. pp. 1975–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markowitz SD, Bertagnolli MM. Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2449–2460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morán A, Ortega P, de Juan C, Fernández-Marcelo T, Frías C, Sánchez-Pernaute A, Torres AJ, Díaz-Rubio E, Iniesta P, Benito M. Differential colorectal carcinogenesis: Molecular basis and clinical relevance. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:151–158. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i3.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imai K, Yamamoto H. Carcinogenesis and microsatellite instability: the interrelationship between genetics and epigenetics. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:673–680. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Lundgreen A, Fitzpatrick FA, Curtin K, Wolff RK. Genetic variation in a metabolic signaling pathway and colon and rectal cancer risk: mTOR, PTEN, STK11, RPKAA1, PRKAG2, TSC1, TSC2, PI3K and Akt1. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1604–1611. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fearnhead NS, Wilding JL, Bodmer WF. Genetics of colorectal cancer: hereditary aspects and overview of colorectal tumorigenesis. Br Med Bull. 2002;64:27–43. doi: 10.1093/bmb/64.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grady WM, Markowitz SD. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in colon cancer. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2002;3:101–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.3.022502.103043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science. 1997;275:1787–1790. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Easwaran V, Lee SH, Inge L, Guo L, Goldbeck C, Garrett E, Wiesmann M, Garcia PD, Fuller JH, Chan V, et al. beta-Catenin regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3145–3153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brabletz T, Jung A, Reu S, Porzner M, Hlubek F, Kunz-Schughart LA, Knuechel R, Kirchner T. Variable beta-catenin expression in colorectal cancers indicates tumor progression driven by the tumor environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10356–10361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171610498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneikert J, Behrens J. The canonical Wnt signalling pathway and its APC partner in colon cancer development. Gut. 2007;56:417–425. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.093310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goss KH, Groden J. Biology of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1967–1979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujishita T, Aoki K, Lane HA, Aoki M, Taketo MM. Inhibition of the mTORC1 pathway suppresses intestinal polyp formation and reduces mortality in ApcDelta716 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13544–13549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800041105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheid MP, Marignani PA, Woodgett JR. Multiple phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent steps in activation of protein kinase B. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6247–6260. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.17.6247-6260.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips WA, St Clair F, Munday AD, Thomas RJ, Mitchell CA. Increased levels of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in colorectal tumors. Cancer. 1998;83:41–47. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980701)83:1<41::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roymans D, Slegers H. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in tumor progression. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:487–498. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parsons DW, Wang TL, Samuels Y, Bardelli A, Cummins JM, DeLong L, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Willson JK, et al. Colorectal cancer: mutations in a signalling pathway. Nature. 2005;436:792. doi: 10.1038/436792a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson SM, Gulhati P, Rampy BA, Han Y, Rychahou PG, Doan HQ, Weiss HL, Evers BM. Novel expression patterns of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway components in colorectal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:767–776, 776-778. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ekstrand AI, Jönsson M, Lindblom A, Borg A, Nilbert M. Frequent alterations of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:125–129. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perrone F, Lampis A, Orsenigo M, Di Bartolomeo M, Gevorgyan A, Losa M, Frattini M, Riva C, Andreola S, Bajetta E, et al. PI3KCA/PTEN deregulation contributes to impaired responses to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:84–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandurangan AK. Potential targets for prevention of colorectal cancer: a focus on PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Wnt pathways. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:2201–2205. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Roock W, De Vriendt V, Normanno N, Ciardiello F, Tejpar S. KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and PTEN mutations: implications for targeted therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:594–603. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shuch B, Ricketts CJ, Vocke CD, Komiya T, Middelton LA, Kauffman EC, Merino MJ, Metwalli AR, Dennis P, Linehan WM. Germline PTEN mutation Cowden syndrome: an underappreciated form of hereditary kidney cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1990–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pritchard CC, Smith C, Marushchak T, Koehler K, Holmes H, Raskind W, Walsh T, Bennett RL. A mosaic PTEN mutation causing Cowden syndrome identified by deep sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:1004–1007. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thiem S, Pierce TP, Palmieri M, Putoczki TL, Buchert M, Preaudet A, Farid RO, Love C, Catimel B, Lei Z, et al. mTORC1 inhibition restricts inflammation-associated gastrointestinal tumorigenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:767–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI65086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, Lane H, Hofmann F, Hicklin DJ, Ludwig DL, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, Chandarlapaty S, Pagano NC, Poulikakos PI, Scaltriti M, Moskatel E, Baselga J, Guichard S, Rosen N. mTOR kinase inhibition causes feedback-dependent biphasic regulation of AKT signaling. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:248–259. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levine AJ, Finlay CA, Hinds PW. P53 is a tumor suppressor gene. Cell. 2004;116:S67–S69, 1 p following S69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baker SJ, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, Paraskeva C, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Hamilton S, Vogelstein B. p53 gene mutations occur in combination with 17p allelic deletions as late events in colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7717–7722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng Z. p53 regulation of the IGF-1/AKT/mTOR pathways and the endosomal compartment. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001057. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Feng Z, Levine AJ. The regulation of energy metabolism and the IGF-1/mTOR pathways by the p53 protein. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buckbinder L, Talbott R, Velasco-Miguel S, Takenaka I, Faha B, Seizinger BR, Kley N. Induction of the growth inhibitor IGF-binding protein 3 by p53. Nature. 1995;377:646–649. doi: 10.1038/377646a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stambolic V, MacPherson D, Sas D, Lin Y, Snow B, Jang Y, Benchimol S, Mak TW. Regulation of PTEN transcription by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;8:317–325. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Budanov AV, Karin M. P53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mtor signaling. Cell. 2008:134: 451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8204–8209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502857102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feng Z, Hu W, de Stanchina E, Teresky AK, Jin S, Lowe S, Levine AJ. The regulation of AMPK beta1, TSC2, and PTEN expression by p53: stress, cell and tissue specificity, and the role of these gene products in modulating the IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3043–3053. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ellisen LW, Ramsayer KD, Johannessen CM, Yang A, Beppu H, Minda K, Oliner JD, McKeon F, Haber DA. REDD1, a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53, links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2002;10:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E, Witters LA, Ellisen LW, Kaelin WG. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2893–2904. doi: 10.1101/gad.1256804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajalingam K, Schreck R, Rapp UR, Albert S. Ras oncogenes and their downstream targets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1177–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rajalingam K, Schreck R, Rapp UR, and Albert Š, Ras oncogenes and their downstream targets. BBA. 2007:1773: 1177–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ballif BA, Roux PP, Gerber SA, MacKeigan JP, Blenis J, Gygi SP. Quantitative phosphorylation profiling of the ERK/p90 ribosomal S6 kinase-signaling cassette and its targets, the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:667–672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409143102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roux PP, Shahbazian D, Vu H, Holz MK, Cohen MS, Taunton J, Sonenberg N, Blenis J. RAS/ERK signaling promotes site-specific ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation via RSK and stimulates cap-dependent translation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14056–14064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pende M, Um SH, Mieulet V, Sticker M, Goss VL, Mestan J, Mueller M, Fumagalli S, Kozma SC, Thomas G. S6K1(-/-)/S6K2(-/-) mice exhibit perinatal lethality and rapamycin-sensitive 5’-terminal oligopyrimidine mRNA translation and reveal a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent S6 kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3112–3124. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3112-3124.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roux PP, Ballif BA, Anjum R, Gygi SP, Blenis J. Tumor-promoting phorbol esters and activated Ras inactivate the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13489–13494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405659101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.García-Mauriño S, Alcaide A, Domínguez C. Pharmacological control of autophagy: therapeutic perspectives in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3853–3873. doi: 10.2174/138161212802083653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Francipane MG, Lagasse E. Selective targeting of human colon cancer stem-like cells by the mTOR inhibitor Torin-1. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1948–1962. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raina K, Agarwal C, Wadhwa R, Serkova NJ, Agarwal R. Energy deprivation by silibinin in colorectal cancer cells: a double-edged sword targeting both apoptotic and autophagic machineries. Autophagy. 2013;9:697–713. doi: 10.4161/auto.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Luo Y, Yoneda J, Ohmori H, Sasaki T, Shimbo K, Eto S, Kato Y, Miyano H, Kobayashi T, Sasahira T, et al. Cancer usurps skeletal muscle as an energy repository. Cancer Res. 2014;74:330–340. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alqurashi N, Gopalan V, Smith RA, Lam AK. Clinical impacts of mammalian target of rapamycin expression in human colorectal cancers. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2089–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gulhati P, Bowen KA, Liu J, Stevens PD, Rychahou PG, Chen M, Lee EY, Weiss HL, O’Connor KL, Gao T, et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 regulate EMT, motility, and metastasis of colorectal cancer via RhoA and Rac1 signaling pathways. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3246–3256. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aoki K, Tamai Y, Horiike S, Oshima M, Taketo MM. Colonic polyposis caused by mTOR-mediated chromosomal instability in Apc+/Delta716 Cdx2+/- compound mutant mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35:323–330. doi: 10.1038/ng1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Menon S, Yecies JL, Zhang HH, Howell JJ, Nicholatos J, Harputlugil E, Bronson RT, Kwiatkowski DJ, Manning BD. Chronic activation of mTOR complex 1 is sufficient to cause hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra24. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tsang CK, Qi H, Liu LF, Zheng XF. Targeting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) for health and diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun SY. mTOR kinase inhibitors as potential cancer therapeutic drugs. Cancer Lett. 2013;340:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM. Targeting the mTOR signaling network for cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2278–2287. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang YJ, Dai Q, Sun DF, Xiong H, Tian XQ, Gao FH, Xu MH, Chen GQ, Han ZG, Fang JY. mTOR signaling pathway is a target for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2617–2628. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang YJ, Duan Y, Zheng XF. Targeting the mTOR kinase domain: the second generation of mTOR inhibitors. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim DD, Eng C. The promise of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1775–1788. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.721353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Altomare I, Hurwitz H. Everolimus in colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:505–513. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.770473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Price TJ, Segelov E, Burge M, Haller DG, Ackland SP, Tebbutt NC, Karapetis CS, Pavlakis N, Sobrero AF, Cunningham D, et al. Current opinion on optimal treatment for colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2013;13:597–611. doi: 10.1586/era.13.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wong A, Ma BB. Personalizing therapy for colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gulhati P, Cai Q, Li J, Liu J, Rychahou PG, Qiu S, Lee EY, Silva SR, Bowen KA, Gao T, et al. Targeted inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling inhibits tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7207–7216. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ng K, Tabernero J, Hwang J, Bajetta E, Sharma S, Del Prete SA, Arrowsmith ER, Ryan DP, Sedova M, Jin J, et al. Phase II study of everolimus in patients with metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma previously treated with bevacizumab-, fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-based regimens. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3987–3995. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spindler KL, Sorensen MM, Pallisgaard N, Andersen RF, Havelund BM, Ploen J, Lassen U, Jakobsen AK. Phase II trial of temsirolimus alone and in combination with irinotecan for KRAS mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: outcome and results of KRAS mutational analysis in plasma. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:963–970. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.776175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Di Nicolantonio F, Arena S, Tabernero J, Grosso S, Molinari F, Macarulla T, Russo M, Cancelliere C, Zecchin D, Mazzucchelli L, et al. Deregulation of the PI3K and KRAS signaling pathways in human cancer cells determines their response to everolimus. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2858–2866. doi: 10.1172/JCI37539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Altomare I, Bendell JC, Bullock KE, Uronis HE, Morse MA, Hsu SD, Zafar SY, Blobe GC, Pang H, Honeycutt W, et al. A phase II trial of bevacizumab plus everolimus for patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2011;16:1131–1137. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bullock KE, Hurwitz HI, Uronis HE, Morse MA, Blobe GC, Hsu SD, Zafar SY, Nixon AB, Howard LA, and Bendell JC. Bevacizumab (b) plus everolimus (e) in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4080. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wolpin BM, Ng K, Zhu AX, Abrams T, Enzinger PC, McCleary NJ, Schrag D, Kwak EL, Allen JN, Bhargava P, et al. Multicenter phase II study of tivozanib (AV-951) and everolimus (RAD001) for patients with refractory, metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18:377–378. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Moroney J, Fu S, Moulder S, Falchook G, Helgason T, Levenback C, Hong D, Naing A, Wheler J, Kurzrock R. Phase I study of the antiangiogenic antibody bevacizumab and the mTOR/hypoxia-inducible factor inhibitor temsirolimus combined with liposomal doxorubicin: tolerance and biological activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5796–5805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chu C, Noël-Hudson MS, Boige V, Goéré D, Marion S, Polrot M, Bigot L, Gonin P, Farinotti R, Bonhomme-Faivre L. Therapeutic efficiency of everolimus and lapatinib in xenograft model of human colorectal carcinoma with KRAS mutation. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2013;27:434–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2012.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, Elliott F, Daly CL, Meade AM, Taylor G, Barrett JH, Quirke P. KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5931–5937. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sharma S, Reid T, Hoosen S, Garrett C, Beck J, Davidson S, MacKenzie M, Brandt U, and Hecht J. Phase i study of rad001 (everolimus), cetuximab, and irinotecan as second-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer (mcrc) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gulhati P, Zaytseva YY, Valentino JD, Stevens PD, Kim JT, Sasazuki T, Shirasawa S, Lee EY, Weiss HL, Dong J, et al. Sorafenib enhances the therapeutic efficacy of rapamycin in colorectal cancers harboring oncogenic KRAS and PIK3CA. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1782–1790. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Anthony L, Bajetta E, Kocha W, Panneerselvam A, Saletan S, and O'Dorisio T, Efficacy and safety of everolimus plus octreotide lar in patients with colorectal neuroendocrine tumors (net): Subgroup analysis of the phase iii radiant-2 trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011:106: S154–S155. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bradshaw-Pierce EL, Pitts TM, Kulikowski G, Selby H, Merz AL, Gustafson DL, Serkova NJ, Eckhardt SG, Weekes CD. Utilization of quantitative in vivo pharmacology approaches to assess combination effects of everolimus and irinotecan in mouse xenograft models of colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fang DD, Zhang CC, Gu Y, Jani JP, Cao J, Tsaparikos K, Yuan J, Thiel M, Jackson-Fisher A, Zong Q, et al. Antitumor Efficacy of the Dual PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor PF-04691502 in a Human Xenograft Tumor Model Derived from Colorectal Cancer Stem Cells Harboring a PIK3CA Mutation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mueller A, Bachmann E, Linnig M, Khillimberger K, Schimanski CC, Galle PR, Moehler M. Selective PI3K inhibition by BKM120 and BEZ235 alone or in combination with chemotherapy in wild-type and mutated human gastrointestinal cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:1601–1615. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1869-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Roper J, Richardson MP, Wang WV, Richard LG, Chen W, Coffee EM, Sinnamon MJ, Lee L, Chen PC, Bronson RT, et al. The dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 induces tumor regression in a genetically engineered mouse model of PIK3CA wild-type colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Deming DA, Leystra AA, Farhoud M, Nettekoven L, Clipson L, Albrecht D, Washington MK, Sullivan R, Weichert JP, and Halberg RB, et al. PLoS One. 2013:8: 1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Atreya CE, Ducker GS, Feldman ME, Bergsland EK, Warren RS, Shokat KM. Combination of ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors with standard chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:2219–2225. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9793-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Janku F, Tsimberidou AM, Garrido-Laguna I, Wang X, Luthra R, Hong DS, Naing A, Falchook GS, Moroney JW, Piha-Paul SA, et al. PIK3CA mutations in patients with advanced cancers treated with PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:558–565. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim A, Lee JE, Lee SS, Kim C, Lee SJ, Jang WS, Park S. Coexistent mutations of KRAS and PIK3CA affect the efficacy of NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/MTOR inhibitor, in regulating the PI3K/MTOR pathway in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:984–996. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.She QB, Halilovic E, Ye Q, Zhen W, Shirasawa S, Sasazuki T, Solit DB, Rosen N. 4E-BP1 is a key effector of the oncogenic activation of the AKT and ERK signaling pathways that integrates their function in tumors. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang Y, Zheng XF. mTOR-independent 4E-BP1 phosphorylation is associated with cancer resistance to mTOR kinase inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:594–603. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.3.19096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Martinelli E, Troiani T, D’Aiuto E, Morgillo F, Vitagliano D, Capasso A, Costantino S, Ciuffreda LP, Merolla F, Vecchione L, et al. Antitumor activity of pimasertib, a selective MEK 1/2 inhibitor, in combination with PI3K/mTOR inhibitors or with multi-targeted kinase inhibitors in pimasertib-resistant human lung and colorectal cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2089–2101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang H, Daouti S, Li WH, Wen Y, Rizzo C, Higgins B, Packman K, Rosen N, Boylan JF, Heimbrook D, et al. Identification of the MEK1(F129L) activating mutation as a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to MEK inhibition in human cancers carrying the B-RafV600E mutation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5535–5545. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Coffee EM, Faber AC, Roper J, Sinnamon MJ, Goel G, Keung L, Wang WV, Vecchione L, de Vriendt V, Weinstein BJ, et al. Concomitant BRAF and PI3K/mTOR blockade is required for effective treatment of BRAF(V600E) colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2688–2698. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Das D, Arber N, Jankowski JA. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. Digestion. 2007;76:51–67. doi: 10.1159/000108394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chia WK, Ali R, Toh HC. Aspirin as adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer--reinterpreting paradigms. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:561–570. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lai SW, Liao KF. Aspirin use after diagnosis improves survival in older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:843–844. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Baba Y, Shima K, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1596–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Din FV, Valanciute A, Houde VP, Zibrova D, Green KA, Sakamoto K, Alessi DR, Dunlop MG. Aspirin inhibits mTOR signaling, activates AMP-activated protein kinase, and induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1504–1515.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhang YJ, Bao YJ, Dai Q, Yang WY, Cheng P, Zhu LM, Wang BJ, Jiang FH. mTOR signaling is involved in indomethacin and nimesulide suppression of colorectal cancer cell growth via a COX-2 independent pathway. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:580–588. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ho VW, Leung K, Hsu A, Luk B, Lai J, Shen SY, Minchinton AI, Waterhouse D, Bally MB, Lin W, et al. A low carbohydrate, high protein diet slows tumor growth and prevents cancer initiation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4484–4493. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1679–1687. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang ZJ, Zheng ZJ, Kan H, Song Y, Cui W, Zhao G, Kip KE. Reduced risk of colorectal cancer with metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2323–2328. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Higurashi T, Takahashi H, Endo H, Hosono K, Yamada E, Ohkubo H, Sakai E, Uchiyama T, Hata Y, Fujisawa N, et al. Metformin efficacy and safety for colorectal polyps: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kalaany NY, Sabatini DM. Tumours with PI3K activation are resistant to dietary restriction. Nature. 2009;458:725–731. doi: 10.1038/nature07782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cufí S, Corominas-Faja B, Lopez-Bonet E, Bonavia R, Pernas S, López IÁ, Dorca J, Martínez S, López NB, Fernández SD, et al. Dietary restriction-resistant human tumors harboring the PIK3CA-activating mutation H1047R are sensitive to metformin. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1484–1495. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, Sugiyama M, Uchiyama T, Suzuki K, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, Fujita K, Yoneda M, et al. Metformin suppresses azoxymethane-induced colorectal aberrant crypt foci by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49:662–671. doi: 10.1002/mc.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tomimoto A, Endo H, Sugiyama M, Fujisawa T, Hosono K, Takahashi H, Nakajima N, Nagashima Y, Wada K, Nakagama H, et al. Metformin suppresses intestinal polyp growth in ApcMin/+ mice. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2136–2141. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ponnurangam S, Standing D, Rangarajan P, Subramaniam D. Tandutinib inhibits the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway to inhibit colon cancer growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:598–609. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Shishodia S. Molecular mechanisms of curcumin action: gene expression. Biofactors. 2013;39:37–55. doi: 10.1002/biof.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Johnson SM, Gulhati P, Arrieta I, Wang X, Uchida T, Gao T, Evers BM. Curcumin inhibits proliferation of colorectal carcinoma by modulating Akt/mTOR signaling. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3185–3190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Banerjee N, Kim H, Talcott S, Mertens-Talcott S. Pomegranate polyphenolics suppressed azoxymethane-induced colorectal aberrant crypt foci and inflammation: possible role of miR-126/VCAM-1 and miR-126/PI3K/AKT/mTOR. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:2814–2822. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Weijenberg MP, Hughes LA, Bours MJ, Simons CC, van Engeland M, van den Brandt PA. The mTOR Pathway and the Role of Energy Balance Throughout Life in Colorectal Cancer Etiology and Prognosis: Unravelling Mechanisms Through a Multidimensional Molecular Epidemiologic Approach. Curr Nutr Rep. 2013;2:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s13668-012-0038-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hughes LA, Simons CC, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, van Engeland M, Weijenberg MP. Body size and colorectal cancer risk after 16.3 years of follow-up: an analysis from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1127–1139. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Pischon T, Lahmann PH, Boeing H, Friedenreich C, Norat T, Tjønneland A, Halkjaer J, Overvad K, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Body size and risk of colon and rectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:920–931. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kaaks R, Lukanova A. Energy balance and cancer: the role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001;60:91–106. doi: 10.1079/pns200070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Slattery ML, Fitzpatrick FA. Convergence of hormones, inflammation, and energy-related factors: a novel pathway of cancer etiology. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:922–930. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]