Abstract

Background

Recruiting and retaining human participants in cancer clinical trials is challenging for many investigators. Although we expect participants to identify and weigh the benefits and burdens of research participation for themselves, it is not clear what burdens adult cancer participants perceive in relation to benefits. We identify key attributes and develop an initial conceptual framework of benefit and burden based on interviews with individuals enrolled in cancer clinical research.

Methods

Semistructured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 32 patients enrolled in cancer clinical trials at a large northeastern cancer center. Krueger's guidelines for qualitative methodology were followed.

Results

Respondents reported a range of benefits and burdens associated with research participation. Benefits such as access to needed medications that subjects otherwise might not be able to afford, early detection and monitoring of the disease, potential for remission or cure, and the ability to take control of their lives through actively participating in the trial were identified. Burdens included the potentiality of side effects, worry and fear of the unknown, loss of job support, and financial concerns.

Conclusions

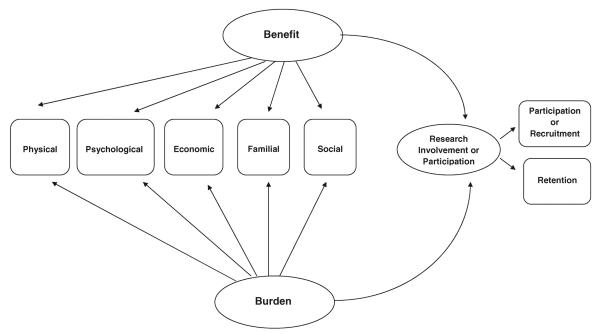

Both benefit and burden influence research participation, including recruitment and retention in clinical trials. Dimensions of benefit and burden include physical, psychological, economic, familial, and social. Understanding the benefit-burden balance involved in the voluntary consent of human subjects is a fundamental tenet of research and important to ensure that subjects have made an informed decision regarding their decision to participate in clinical research.

Keywords: benefits, burdens, cancer, clinical trials, qualitative methods

Clinical research is imperative to generate knowledge that will reduce the morbidity and mortality of human disease. In fact, the vast majority of clinical research relies on the voluntary participation of human subjects. However, it is well documented that only a small percentage of eligible adults actually enroll in cancer clinical trials in the United States, although cancer is now a global disease and contributed to more than 7 million deaths across the world in 2008 (Murthy, Krumholz, and Gross 2004; World Health Organization 2006). Participation in a clinical trial (CT) requires obligations by cancer patients that may add to the burden of cancer diagnosis and treatment. For some, this “added burden” may not be acceptable for various reasons. But how do patients make what they perceive to be the best decision in a complex and uncertain situation? Little is known about how research participants weigh the benefits and burdens of their participation in clinical trials.

Joffe and Miller (2006) rightfully argue that a risk/benefit assessment is part of any research review process. In fact, the Belmont Report, an enduring historical medical ethics document, outlines three specific ethical principles for the protection of human subjects enrolled in clinical research: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The principle of beneficence obligates researchers not only to avoid patient harm but also to minimize the risks and maximize the benefits associated with research participation. Institutional review board (IRB) members consistently evaluate the risks and benefits of research to human subjects; what is not clear, however, is how patients actually balance the benefits and burdens of research participation and how they define these concepts for themselves. Understanding the benefit–burden balance involved in the voluntary consent of human subjects is a fundamental tenet of research and important in ensuring subjects have made an informed decision regarding their decision to participate in clinical research.

The benefits and burdens of research participation have not been adequately studied in seriously ill cancer patients enrolled in clinical research. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB 1976) first used the term “respondent burden” in an effort to improve response rates to surveys by asking researchers to minimize the time and effort required of respondents. Social scientists often equate burden with time commitment associated with filling out a survey questionnaire or conducting face-to-face or telephone interviews and question the best way to achieve an acceptable response rate (Bradburn 1977; Ulrich et al. 2005). But this represents only one type of possible burden. In our previous work, we conceptually defined respondent burden in clinical research as “a subjective phenomenon that describes the perception by the subject of the psychological, physical, and/or economic hardships associated with participation in the research process.” (Ulrich, Wallen, Fiester, and Grady 2005). This article further defines respondent burden and reports results of a study that analyzes the benefits and burdens of research participation with the development of a preliminary model based on interviews with individuals enrolled in cancer clinical research.

METHODS

Sample Design and Recruitment

Adult cancer patients enrolled in cancer clinical trials at a large Northeastern cancer center were recruited for this study. This cancer center oversees one of the largest CT programs in the country, with more than 200 trials ongoing at any one time. Maximum variation sampling, a form of purposive sampling, was used to recruit a heterogeneous sample. A diverse subject pool was targeted to insure inclusion of subjects with a wide range of perceptions about the benefits and burdens in clinical trials. We included English-speaking subjects who were 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of cancer and/or solid tumor from any diagnostic category (e.g., female breast and/or ovarian, colon-rectal, prostate, lymphatic cancers including Hodgkins and non-Hodgkins lymphoma, or other areas). All subjects were currently enrolled in a Phase I, II, or III clinical research treatment trial and/or other type of clinical treatment trial (e.g., compassionate use of a drug for advanced disease, nonrandomized single-arm observational single-institutional studies for refractory cancer diagnoses). The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at the University of Pennsylvania, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Recruitment of participants was an ongoing process. First, the principal investigator (PI) discussed the study with the director of compliance and monitoring of the Clinical Trials Scientific Review and Monitoring Committee at the designated cancer center. Second, the PI contacted and met with different specialty groups of research nurses and physicians at the center to discuss the study and gain access to potential subjects. In addition, the PI worked closely with the associate administrative director of the clinical research unit for the cancer center to receive monthly patient subject accrual information via the Velos Clinical Trials Management System. Finally, following approval of the study at the cancer center, the PI and her research assistant contacted patients at their designated cancer clinic appointment or by telephone and subsequently made individual follow-up visits or telephone calls as needed.

Data Collection

Qualitative semistructured face-to-face or telephone interviews were conducted to elicit participants' perceptions of benefits and burdens related to their participation in CTs. Basic descriptive information about the participants and answers to relevant questions about the clinical trial were collected via a structured demographic form. For the qualitative interviews, we provided flexible options for cancer research participants because of the potential for fatigue or other perceived burdens. Here, we arranged for a convenient time to meet participants at a private location within the clinic and also offered them the option of telephone interviewing, if it was deemed more appropriate. As is standard in qualitative studies, the precise number of interviews was determined based upon reaching data saturation, that is, when the full range of ideas had been explored, with no new themes being discovered by additional interviews (Guest, Bunce, and Johnson 2006). Interviews were conducted in private areas or by telephone calls from a private office to ensure confidentiality. All sessions were audiotaped.

The interview tool was developed by the research team, a team that included experts in qualitative methodology, bioethics, and clinical trials, and the interview tool consisted of broad open-ended questions (e.g., “I'd like to start by having you tell me in your own words what it is like for you to be a research subject/participant in your cancer clinical trial”). We used an iterative process and added questions based on the initial interviews (e.g., questions about randomization and placebo). Sample probes were included as appropriate, and both prepared and spontaneous probes were used as themes of interest developed over the interviews.

The interviewer took detailed field notes during the interviews to provide further clarification. Participants received $20 for completing the interview. In order to minimize systematic bias and standardize our interview procedures, the interviews were conducted within 60–120 days of each participant's enrollment in a clinical trial. This time frame gave subjects the ability to reasonably define benefit–burden evaluations from their personal experience.

Data Analysis

Relying on Krueger's guidelines for qualitative methodology (Krueger 1998), the analysis plan included identifying the main themes arising from the interviews, considering the meaning of the participants' words, and evaluating consistency of responses throughout the interviews. The trustworthiness of the data and themes generated were established using standards for rigor in qualitative analysis including the following four criteria: credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability (Denzin and Lincoln 2000; Lincoln and Guba 1985).

In order to establish the first criterion of credibility, interviews were transcribed verbatim and then independently analyzed by two reviewers (GW, CM-D) who identified themes that emerged from each of the transcribed interviews. To support the second criterion of dependability, the initial content analysis by the independent reviewers was then evaluated by the PI (CU) as a review for the completeness and consistency of participants' meaning throughout the analysis. Following the independent thematic analyses and the evaluation by the PI, a debriefing session was held with the two reviewers and the PI to establish consensus regarding major themes.

Six study participants reviewed and commented on a draft of the final themes, providing further consensus that the thematic interpretation represented what they had intended to convey regarding the benefits and burdens of participation in cancer clinical trials. This additional step in the thematic consensus process engaged participants in reviewing themes and provided evidence for the third criterion for the trustworthiness of the data, namely, confirmability. NVivo 7, a computer program especially developed to manage qualitative data, was used to store and access coded text. Confirmability was also supported through the use of field notes that accompanied each of the interviews.

Transferability, the fourth criterion for trustworthiness of the data, which establishes whether the findings will have meaning to others, was supported by the final review of the established themes by the remainder of the study team that included healthcare providers with expertise in qualitative methods, clinical trials, and human subjects protections. In addition, basic descriptive statistics of the sample are presented with measures of central tendency (i.e., frequencies, means, and standard deviations).

Analysis of the Benefits and Burdens of Research Participation with Preliminary Model Development

Choosing to enroll in a cancer clinical trial raises questions of uncertainty and the risk/benefit trade-offs in one's decision to participate in the research. Based on our analysis, we developed an overarching model that includes five dimensions of decision making (physical, psychological, economic, familial, and social) and the latent constructs (benefit and burden) they measure (Figure 1). The model postulates that both benefit and burden influence research participation, including recruitment and retention in clinical trials. The analysis and description of the five dimensions used to build this model are discussed next.

Figure 1.

A model outlining the benefits and burdens of research participation. (Further testing is needed to determine the relationships among the dimensions.)

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample (n = 32) was primarily female (75%), Caucasian (78%), and married (71.9%). Nearly 20% of the sample was African-American (18.8%). Respondents' mean age was 53.9 years (SD ± 13.8, range = 29–74), and 31% were employed full-time. The majority of the sample (53%) had attended college (including some college, college degree, and postgraduate work), and 37.9% of respondents indicated that they had participated in previous research studies. For the most part, participants were privately insured (56.3%), yet one third (33.3%) reported that healthcare insurance moderately to extremely influenced their decision making regarding health care, including participation in clinical trials. More than half of the members of the sample were enrolled in Phase III trials (51.9%), and most were diagnosed with breast cancer (50%), followed by hematological disorders and melanoma (21.4% and 10.7%, respectively). Examples of the trials included the ASSURE trial, a Phase III randomized study of adjuvant sunitinib versus sorafenib in patients with resected renal-cell cancer, and a double-blind Phase III trial studying doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel, to see how well the combination of these drugs work with or without bevacizumab in treating patients with lymph-node-positive or high-risk, lymph-node-negative breast cancer.

Slightly more than one-third of subjects (37%) reported few to limited treatment options available for their disease, and when 19 of the 32 subjects were asked “How likely did you think it was that you would personally benefit from the clinical trial?,” 42.1% indicated they were not sure what to expect, while 26.3% reported moderate benefit and 10.3% indicated they hoped it cured their disease. More than two-thirds of subjects (67.8%) indicated that their physician was moderately to extremely influential in their healthcare decision making. The majority of subjects (74%) rated their spiritual and/or religious beliefs as strongly to completely important in their lives. Finally, qualitative interviews included both semistructured face-to-face (n = 15) and telephone (n = 17) interviews.

Physical Concerns of Research Participation

Health-related aspects of the decision to participate in the trial were notable and centered on several subthemes of benefits and burdens. These included the benefits of early detection and monitoring of the disease, potential for remission or cure, and weighing the harm to self. Interestingly, for subjects diagnosed with a disease where there are few standard treatment options (e.g., melanoma), the opportunity to participate in clinical trials created a sense of benefit and hope for the future. Many subjects were willing to tolerate what they termed the “inconveniences” because they were under a doctor's care and any serious side effect would be closely monitored with scheduled follow-ups. A participant described it this way:

“Another benefit is that I'm really closely monitored. Because I'm in the study, they said you know, I'll have more testing, and stuff than other people would, you know, with the follow up, and I don't know if that will get old, or I'm just gonna be thankful that I have somebody looking over my shoulder for years. You know, in case it would come back.”

Physical burdens were often expressed in terms of the severity and frequency of symptoms. As defined by one participant, a burden is a

“difficulty, or added difficulty, or an added test that you will need to do that would make maybe your day-to-day existence more difficult or you would have to handle something differently.”

Symptom burden and the seriousness of the risks that subjects might experience in the trial were significant considerations of research participation. Illustrative comments from our participants demonstrated the physical toll of research participation with emphasis on feelings of fatigue and energy depletion.

“I have less energy, and I have gone down, down the tube.”

“I mean, last month I thought about it, after oh my God, I'm just so sick. I can't do this, but I thought it was a cold coming on. And it just had me down, like when I went last month, I told them, I said, you know, I didn't even want to come here today. I just felt so bad. They said I'm glad you came, but it was the pills, they had upped the pills up, and I guess my system couldn't take it [at all]. After that I felt okay.”

The physical demands of research participation can be extremely taxing, yet many participants participated and remained in their specific trials because the side effects or symptom burdens were held to a minimum and they were committed to these trials. However, participants were also willing to accept fatigue, hair loss, digestive disturbances, and other experimental drug-related effects if it meant there was a possibility of keeping their cancer at bay, the opportunity to extend their lives for a period of time, or the chance of being cancer free. Personal inconveniences, such as travel time and disruption in daily living, were additional burdens when participants were feeling ill or otherwise weakened from experimental regimens. But having faith and confidence in the physician to recognize and evaluate any adverse symptoms associated with research participation was also noted as a beneficial aspect of participation.

Psychological Dimensions

Participation in cancer clinical trials evoked both beneficial and burdensome psychological responses. Several subthemes emerged under this category. First, participants often spoke of their sense of accomplishment and giving back. This was closely tied to their thoughts of not giving in and maintaining a sense of control over the situation. Participation in the trial was seen as contributing to a hopeful outlook about their condition. As one subject indicated, “There's a sort of a psychological benefit in that I am doing something, I'm actively taking steps to treat the disease.” Second, many participants cited the importance of gaining knowledge or learning something that they didn't know about their disease via participation.

Third, spirituality was discussed as an important component of decision making. Spirituality was perceived as having faith, trust, and confidence in the research team members as well as trusting in a higher power to cope with the cancer diagnosis and treatment course. However, fear of the unknown, of a loss of control, and of loss of self, and concerns about the generalities or procedural aspects of the trial itself were psychologically worrisome. For example, two participants discussed the burden of living with a diagnosis of cancer and its implications.

“If it's not gonna help me … if it's gonna put me over the edge and just killing me with cancer then no, I don't want to participate. I am willing to take anything that[s] going to make me feel better. Keep me strong. Keep me healthy. Keep me alive.”

“Right, nothing crippling, but just having the disease is a terrible burden. Just knowing it's there, and dealing with that every day is stressful.”

Many participants spoke of the uncertainty of living with a cancer diagnosis and the emotional distress that goes along with it. Some spoke of having an “identity crisis” by asking themselves the question: Who am I? Having positive results by participating in the trial, such as a decrease in tumor size or stable results on laboratory values, provided a “sense of security” to participants. Participation also provided a way for cancer patients to actively take control of a situation that is perceived to be out of control.

Economic or Fiscal Concerns

Economic or fiscal concerns can preclude many individuals from thinking about clinical trials or even understanding how they might access a clinical trial for their specific disease. Some respondents in our study discussed the economic or financial cost of participating in research and its impact on their care. For instance, an older African-American gentleman diagnosed with lung cancer commented:

“My belief is any kind of cancer should be researched and, don't get me wrong, I know you should have to pay something but it was a joy knowing that they were trying to help me and it was being funded. … And a lot of the cost was being diverted.”

Other participants discussed the benefit of having access to medications and/or treatments that they might not otherwise have because of the prohibitive cost burden.

“To be honest, part of being in the clinical trial, I don't have to pay my co-pay. Is that awful?”

“The cost of the drugs is astronomical. I'm getting it for free. So I looked at that, too.”

The inability to work as well as the loss of job security, and worries about providing for one's family, changes in insurance coverage, and costs of medications were identified as particularly burdensome. Diverting the cost of cancer care was a relief for many participants, especially because the option of participating in a clinical trial would otherwise not be a viable option.

Familial, Support, and Societal Influences

Familial, support, and societal factors emerged as important components of the constructs of benefit and burden. Many participants spoke of their supportive networks and the emotional care they received from family and friends and their own willingness to give something back to society. Moreover, the ability to pass on information or knowledge to at-risk children or family members was seen as a benefit of research participation. One woman who participated in the study appreciated the amount of information/knowledge that she gained from the trial and stated:

“It's knowledge for me to help me understand more, [and] if I can understand more than I can pass it on to her [refers to daughter].”

Nonetheless, concerned family members were also described paradoxically as potentially burdensome.

“And for them it's been very difficult to see me sitting, or taking naps, being pale, and I mean, I'm okay. But they don't think I'm okay. I'm not what I was before. So to them that's, that's hard. And the hardest thing is to say, `I love you, I understand what you mean, and yeah the side effects were a little tough, but I'm gonna do this anyway.”'

The Internet was also perceived as being both beneficial and burdensome. On the one hand, the Internet provided a means to gather information, gain insight into one's disease process, and prepare questions for meetings with the participants' physicians. Supportive chat rooms were especially helpful for younger participants or for those with a specific type of genetic allele (i.e., BRCA I and BRCA II). One participant stated that using the Internet “ended up doing myself more harm than good,” while others indicated that patients ultimately have to educate themselves regarding clinical trials with the educational burden squarely on the shoulders of the participant.

Weighing the Benefits and Burdens

Participants approached their decision to participate and remain enrolled in cancer clinical trials in diverse ways. Some were less structured and intuitive in their decisions, especially when they perceived they had no other available options, no time to weigh the options, no other way to receive the medicine or tests that were needed for their particular disease, or perceived the study as a “lifeline.” As one subject noted, “I didn't look at the burdens at all, I just looked at the benefits.” These subjects indicated that their decision making focused solely on potential benefits of participation; trust in the physician's recommendations about a particular study was described as a critical aspect of decision making by more than half of participants (n = 17). This focus on trusting their physician was more prevalent in those who were older in age.

Other participants were more deliberate in their decision making by trying to determine how the trial would impact their overall quality of life, the side effects that they might suffer, the ability to drop out of the study if needed, and using a cost/benefit framework to better understand their odds of survival when presented with certain treatment options. Some of the comments shared are provided here:

“And I just thought that if something became burdensome, I mean, there is always written into the study that you know, you're free to drop out whenever, so if something, you know, if I had some horrible side effects or whatever, I still had the option of not continuing if it was a problem.”

“You know if you do absolutely nothing, you have a 70 percent chance of living to be 100, and most people would consider 70 percent a lot. And this was if you do no chemo at all. You know, um, consider it a lot. But suddenly, when it's your life you're looking at, 70 percent doesn't look that impressive. Seventy percent doesn't look impressive at all! When she says, `if you do chemo, you know you have a 95 percent chance,' oh yes, and then you definitely do a cost, 70 percent has never looked that bad to me in my life.”

“Some of the studies that were suggested, they said, `oh your hair will fall out, can you handle that?' Okay. `You'll lose your sense of touch, can you handle that?' Probably could. `You will lose your sense of taste, could you handle that?' Okay. But then you have to add all those things up, and then you have to look, and they say `these are things that will happen, not things that might happen, things that will happen. Add them all up now think about it; honestly, could you handle that? Would it be fair to the people around you,' which is, that may or may not be a pivotal issue to some people, when I looked at it, it was for me. Is it a reasonable or fair thing to do? Is it reasonable for me to turn myself into somebody that I don't recognize and nobody else recognizes and you know, prop me up in the corner? Um, no, no it may not be. So there's a lot to weigh.”

The risk–benefit ratio of any study remains an important indicator of participant participation in research. Each person arrives at his or her decision with different values, needs, and expectations. There is “a lot to weigh,” as aptly noted by one of our participants. How participants weigh the benefits and burdens of research participation and what may be particularly meaningful to them in their decision making needs further evaluation. (See Tables 1 and 2 for further illustrative quotes on the benefits and burdens of research participation.)

Table 1.

Benefits

| Theme | Selected quotes representing benefit |

|---|---|

| Economic | Cost of care |

| • My belief is any kind of cancer should be researched and, don't get me wrong, I know you should have to pay something but it was a joy knowing that they were trying to help me and it was being funded. | |

| • To be honest, part of being in the clinical trial, I don't have to pay my copay Is that awful? | |

| • The cost of the drugs is astronomical. I'm getting it for free. So I looked at that, too. | |

| Familial | Generational inheritance |

| • I've participated in all of those, hoping that it helps out something in the future um, for, for, anybody in my family, or other families that are going through um, going through this. So, so I think those two are hugely beneficial. | |

| • It's knowledge for me to help me understand more, if I can understand more then I can pass it on to her [refers to daughter]. | |

| • Right, this can benefit future generations. | |

| • That's what all life is about, not thinking about ourselves, but thinking, “tomorrow.” | |

| Familial decisonal support | |

| • So I sat with my husband and we talked about it, and decided that there were more pros than cons, and yeah it would be tough, but my whole family said they'll pitch in, we'll help, we'll figure out how to do this. So I went for it. | |

| • Well, we have a great family, a great support system, and it's what we rely on, my main reason for doing it, I mean, like I said, I was very upset and I don't, to this day I'm not really even sure if I would have said yes, except, like as I said, my faith is very strong. I spoke with my brother-in-law who is a cancer survivor, who said you know, go for it. | |

| • Do whatever you can to make yourself better. And even then I wasn't convinced until my youngest son, who's 20, said, “Mom, you promised that you would kick butt and do whatever you had to do to beat this.” And I think, I think that was my deciding moment. | |

| Social networks | |

| • One of the things that amazing about this whole process is, you know, I knew I had good friends and family. I never knew I had the kind of friends and family the way that I have. | |

| • I have friends from all over, from all over the country, where I've traveled and worked and, my family they have done all kinds of things, you know, to let me know they care. That's been really, that's been a wonderful thing about this, so, and I have gotten in contact with some people that I haven't been in contact with for a long time as a result of all this. That's helpful, that's one way, don't be afraid to reach out, don't get too isolated because this can be a very isolated disease. | |

| • And is still continuing to help me. Um, let's see, having um, utilizing your friends and family as a support network. | |

| Physical | Early detection and monitoring of disease |

| • Going back in you know, and I have to travel to [cancer center] to do that um, for my checkups, you know, little bit with traffic and everything, I think it outweighs that because you normally go for checkups and things like that anyway, so in this instance I think it's a good thing. Because you are monitored by someone, um, by my oncologist, who I have, um, a lot of trust in. | |

| • My main concern was um, first of all, early detection, if there's a way of detecting this type of cancer, because it is the type that is evasive—especially the younger you are, and if you don't present with the proper symptoms, it's hard to detect. Um, I did have symptoms for several months before and it was misdiagnosed by another hospital. Until it presented itself the way it did. My whole point in any kind of research at this point would be to help in the future to diagnose this particular form of cancer at an earlier stage. | |

| • Another benefit is that I'm really closely monitored. Because I'm in the study, they said you know, I'll have more testing, and stuff than other people would, you know, with the follow up, and I don't know if that will get old, or I'm just gonna be thankful that I have somebody looking over my shoulder for years. You know, in case it would come back. | |

| • Under this study. I get everything checked, um, much more so than I think other people. | |

| Potential for remission or cure | |

| • I'm sure some people have some other personal choices why they, they wouldn't take a certain drug because the side effects are extreme, and the benefits are very minimal, I'm sure whatever stage in your disease, that may be very important, but as far as I can see, take the first thing the doctor offers you. Even though they know there's no definite benefit. | |

| • The possibility of at least some remission from the disease—the best case scenario, perhaps a cure. | |

| • You know, it gives you a life extension, and I say okay, I know I'm gonna die, I just don't want to die right now. Yeah, not today. It might be tomorrow, but that's okay. Cuz I know I have things to do. | |

| • Hopefully it will put me back in remission again. I believe it's a prime objective. | |

| Weighing harm to self | |

| • Statistically the odds aren't great, but they're there, and it did so without devastating side effects. | |

| • The side effects were explained as being minimal, and I found that to be the case. So that's why I decided to participate. | |

| • Yeah. I wanted to know, if I do this, is it going to harm me in any way, and when the answer was no, then okay, do whatever you need to do. | |

| Psychological | Sense of accomplishment |

| • My motivation is to be staying in the study until it ends. And accomplish something. | |

| • The reason to be on it is just because I think wanting to be a part of something. | |

| • I wanted to be a part of the research because I just felt so strongly that research on this particular cancer needed to be done, so um, that was something I could be a part of and it's important to me, and um, understanding how the drug worked, just being there and being a part of it, and hopefully help someone or something else, greater than what I'm going through, or someone, not having to go through this, is totally worth it. | |

| Knowing | |

| • Well, I think the knowledge helped me to be prepared. As a regular patient I don't think the patients are ready for dramatic changes and things like that. I don't know, I'm a very positive thinking person, I was dealing with oncology for a year, and I was dealing with oncology patients, so the reality, I saw in my eyes in front of me. So that preparedness helped me to look up positive and I am prepared for the chemo, I'm prepared for losing my hair, I was prepared for looking like a baby [laughs] and I could care less, I don't, I just, I'm just saying, “well, now I'm in another site of the game of the ball.” Before, you were taking care of the patient and now you're the patient, and let people take care of me. | |

| • I think it's a positive, it's very positive, because there's things that I can learn … all kinds of things I learn about the clinical trial. Things that I don't know what's going on about it also things about myself. | |

| • However, mentally, as far as my intellect goes, I appreciated learning more, learning more about the disease and of course when I was with these various medical personnel that were um, doing the biopsies or the blood tests or whatever it was um, I grilled them. | |

| • Oh I feel empowered. | |

| Spiritual grounding | |

| • I think so too, and that, you know, that truly believing that and having faith, it really makes the jo(b) a lot easier. It really does. | |

| • And then I have my children, my family, is all behind me, so that means a lot when you're sick, you've gotta have some support. And the Lord and stuff so, it's pretty good. | |

| • Yeah, but honestly, this sounds kind of strange, but I'm kind of grateful. I mean it sounds bizarre, but I'm glad I am where I am right now, I was like thank you Lord I could have been, this could have been 10 years ago, I'd be dead. So I should think everything happens for a reason. | |

| • Beneficial is a spiritual way … | |

| Not giving up | |

| • At least it was my way of fighting back. | |

| • There's a sort of a psychological benefit in that I am doing something, I'm actively taking steps to treat the disease. | |

| • It is, and I think that people need to understand that you know, 20 years ago when you heard the word, “cancer,” it was like a death sentence, and you need to understand that it isn't a death sentence. We've come so far, through research programs and through these trials, that it's okay, a little stumbling block in life: you deal with it, you get over it, you move on. You know? It isn't as much of a death sentence as it was before. And I don't look at it that way. You know, I said it's just another shovelful of stuff that you have to deal with in your life, [laughs] | |

| Turning to hope and help | |

| • If it not gonna help me … if it's gonna put me over the edge and just killing me with cancer then no, I don't want to participate. I am willing to take anything that going to make me feel better. Keep me strong. Keep me healthy. Keep me alive. | |

| • I looked at it as holy mackerel, you mean there's things out there where they could cure me? Geez! Uh, where do I go, where do I sign? | |

| • You turn to wherever there is hope or help. | |

| • There aren't a lot of options where melanoma is concerned. So it was basically, clinical trials or next to nothing. | |

| • I didn't have any other hope. And I wanted to participate because, I, I am an optimist. | |

| Optimistic presence | |

| • In addition to that, my biggest tool is a positive attitude, and they told me that four years ago because this is all about my immune system, and the immune system is linked to your attitude. A negative, fearful attitude will suppress the immune system and the reverse is true. So um, doing something, participating in a program a plan, a treatment that's designed to be helpful and positive keeps me more positive. | |

| • Now I've got too many other things in my life that I have to deal with and take care of, I'm not, I'm not gonna let that [cancer] control my life, and you have to keep the positive attitude, you have to have laughter because that really does make it a lot easier, also. | |

| • Sure. I… I tell you what. I am a pretty positive guy and if I have to leave this earth, then so be it. You know, but I look forward to tomorrow, for the next star and the next week. I don't concern myself with what can go wrong or whatever. There are times, like I told you before, buy I try not to let that bother me. And if it comes to bother me, I'll try to put my brain into something else and just forget about it. And there is something else you can do, the more wrong you think about going wrong then [its] gonna happen. It's quicker. If you're positive and least you can get out of some of it. I've always said smile and laughter is, is what keep people alive. | |

| Commitment and safety | |

| • I guess it was just that you know, maybe a commitment. Um, I know that also my safety is involved, so I know that if there was something going awry with the study, or they were finding information that there was something detrimental going on, I would be immediately advised. So that's important as well. | |

| • And I just thought that if something became burdensome, I mean, there is always written into the study that you know, you're free to drop out whenever, so if something, you know, if I had some horrible side effects or whatever, I still had the option of not continuing if it was a problem. | |

| Social | Giving back |

| • I know if it doesn't help me, it's gonna help somebody else. | |

| • I'm hoping by participating that it, if it is beneficial it's something that, if the results come out positive, that it gets it to market quicker to aid other people. Help other people. | |

| • If one person benefits from it, then I feel like okay, great. That works. | |

| • Second, I have the benefit of knowing that I'm helping other women that will be in this position, I guess women and men. Men can get this, but, but, other women. | |

| • Well, research needs people to be a part of it. If you don't have people participating, there's no way to further the research. So um, that's the biggest benefit. To you know, hopefully help scores of other women who might come down with this particular cancer. | |

| • Thinking about something else, someone else, hoping that there's a greater good for me going through this, it's not just something random, where you know, here I am, I got this cancer and I'm not doing anything about it. | |

| Reaching out, gaining information | |

| • And I think if the patients, the population knows actually what mean the research is a reality, I think we're gonna have a lot more people participate. | |

| • It is very important to reach out to the public in a way of people understand. | |

| • I've talked to maybe 10 to 12 people already um, that are considering this trial, and just to get information from somebody who's already going through it and stuff like that, it's, and possibly more, because I talked to a lot of people online, than I've had actually probably 10 to 12 people call me personally to talk to me about it, so um, so yeah, I mean, I think definitely. | |

| • Because if I didn't have the people at YSC, I think, you know, the Young Survivor Coalition, that had been through it, had given me some guidance and all, and that kind of stuff, I think that I would have been a lot more nervous about the experience. But having that helped me, it was a no-brainer for me, to be honest. |

Table 2.

Perceptions of burden

| Theme | Selected quotes representing burden |

|---|---|

| Economic | Disruption in daily routine focused on work and economics |

| • And, having to take away work, time from work, at a time in my life when every day was very precious to me—and um, you know, let's face it, with work you're only allowed so many days … | |

| • Because I traveled quite a bit. And I got around and you know, I was in the antique business for years—A lot of, a lot of fun. So when I had to give that up, it was you know, heart-wrenching. | |

| • And that, I think that comes with being out of work, probably, too, with respect to that. If it weren't for the health coverage, I would be in big trouble. I would be going to work no matter what my condition was. | |

| Familial | Familial obligations and pressures |

| • I used to travel for a living, so it really wasn't that big of a deal, but I do have a 20-month-old, so, so I guess, you know, at times that just going up there weekly, or this or that, I guess, was a small burden for, you know, but you know, I think everything else outweighs that. | |

| • I was paying more attention to what they were saying [family member]. And I had to back off. And actually look and think, you know, am I stopping this because I want to stop it or because I'm listening to all of them? And I turned around, I'm paying more attention to what they're saying, and I can't do that, I have to listen to what's best for me right now, it's selfish. And that's okay. | |

| • It pushes me to my limit. To get up and I do fix my children breakfast. Then some mornings I just can't put the cereal on the table. But I like to send my children out with some eggs, some potatoes, and some grits, and stuff like that, in the morning. Or even, we'll have oatmeal with toast and tea, I mean, if even they have breakfast at school. | |

| Family perception of burden | |

| •The other thing is, I'm okay with this. I mean, I feel they're tolerable. It's what my family perceives. I've been, I'm a very active person. Oh God, all my life I was. | |

| • Well, um the family thing can be sometimes burdensome, they don't understand. And they just see me looking horrible which they're not used to, they, my one daughter's an RN and she told me to stop the study. And for them it's been very difficult to see me sitting, or taking naps, being pale, and I mean, I'm okay. But they don't think I'm okay. I'm not what I was before. So to them that's, that's hard. Having to admit that I can't do it. And the hardest thing is to say, “I love you, I understand what you mean, and yeah the side effects were a little tough, but I'm gonna do this anyway. One day at a time, I'm doing this.” | |

| Physical | Symptom burden |

| • Because the side effects are so, they're just really wacko. They're pretty severe—the one drug you take is four weeks with two weeks off. Because the side effects build up and the fourth week you're like “yeech.” | |

| • Yeah, I'm tired. I am tired. I'm usually when I go home … there's a lot of things I don't want to do even around the house, I realized I get tired real fast. Walking is the same the thing—I get tired. If I walk too long, if I stand too long, I get tired really fast. I find myself just want to lay there. May not go to sleep, just relax my body … sometimes my body says girl sit down, you tired. Yeah, sit down. Oooh. Feels like ice cubes up my arm. | |

| • That was a different kind of pain. Um, but the pain I suffered before I went in the hospital, was gone the next morning. So you know, there are levels of pain and I can, I'm very tolerant of pain. Oh, the side effects … It affects your muscles, your vision, your back, everything, the chemo is rough stuff. | |

| • I get tired … loose [referring to bowels] and I have to take a lot of things. Otherwise, I have to have accidents on a highway, that's burdensome, it was very hard for me to manage, I would go to the grocery store and come right home 'cause I had to go to the bathroom. | |

| • Because my stomach was so nauseous, that was all, but today I am fine. Every so often you get that feeling … oh you cry why am I on this why am I on this? … I think it's natural. | |

| • Trust me, there are days that you want to tell chemo to stop. Having nothing to do with the study, just tell chemo to stop. But everybody who's been through this, I have the family members say you will get to that point that you say I don't want to do this anymore. And so I'm expecting to have those kind of days. It's fleeting. It's really fleeting, and it's not that I'm going to stop. I'm feeling so bad today, my throat hurts so bad, all of this stuff is just really, getting on my nerves. I don't even feel like getting up out of bed. But I always remember a passage from the Bible, this too shall pass. And there's a St. Theresa prayer I keep on saying, you know, remember exactly where God wants you to be. So yeah, I think anybody on chemo does get to that point of, “ahh!” | |

| • I mean, last month I thought about it, after oh my God, I'm just so sick. I can't do this, but I thought it was a cold coming on. And it just had me down, like when I went last month, I told them, I said, you know, I didn't even want to come here today. I just felt so bad. They said I'm glad you came, but it was the pills, they had upped the pills up, and I guess my system couldn't take it. At all. After that I felt okay. | |

| • That's my biggest burden right there. Losing this. Sacrificing the hair … I got over it. That's something you can get over. You can go to the store and buy a wig or buy a scarf. Oh it's cold. | |

| Travel inconveniences | |

| • The frequency … I'll need to come [so the frequency and the coming] ya the frequency [every week] just inconvenient to come every week as opposed to every two weeks. And that is really the only burden I would say um. | |

| • [The] burdensome part is going to [cancer center]. The travel, you know the sitting and waiting, and all that. | |

| • Most time consuming, including driving. | |

| Psychological | Self image/loss of self/loss of control |

| • Right, nothing crippling, but just having the disease is a terrible burden. Just knowing it's there, and dealing with that every day is stressful. | |

| • For me, I feel that the risks of not knowing what the side effects are for each one. | |

| • I always, I always saw myself that I was an R.N., and I had been in management, and I taught endocrine, I mean I did a lot. And I was still precepting, and teaching the newer nurses, and I liked it, I went back to bedside, I loved it, I absolutely loved it. That part of maybe you're never gonna do that again. Maybe you will, maybe you won't, but worst case scenario, how are you gonna deal with that? And that, that kind of got me down. | |

| • I was a single man, and not that I didn't have anybody to talk to, though you don't want to let everybody in on your business, and it was like, what do I do, you know, I was really, kind of insecure, I was like uh, what do I do, just run out, I just spend all my money, say, “okay, I'm broke now, somebody help me.” | |

| • I did get depressed. I did, it was kind of like, I guess it was that thing, who I was, that kind of thing, that identity … | |

| Generalities of the clinical trial | |

| • To me the burden itself is the paperwork part of it. Just the cancer stuff, not even the research. | |

| • That I think was the biggest burden. That I had, I should have had, it should have been presented differently [informed consent]. | |

| • I mean, at the end of the day, a lot of the burden's on the patient to investigate themselves. | |

| Fear of the unknown | |

| • Just thinking about going through the trial, and thinking about remission, those kinds of things, has it been burdensome any way from that perspective? In all honesty, yes. I think about that a lot. | |

| • The side effects of it and perhaps, you know, your own psychological thoughts about it. Like is this helping me, is it hurting me, is it gonna work, you put too much, too much stock into it, thinking that this is it, you know? That's a huge burden. | |

| • Just in general, fear of the unknown has got to come into a lot of people's heads, why would I put myself through something that I didn't know what the effects are going to be, if I'm going through that added stress, why bother, why do that to me? When I'm already dealing with enough on my plate? Keep in mind that this is part of my history but you've read about this, I was in a car accident six years ago and my right leg was amputated. | |

| • I know there are times that I have to tell myself to stop, stop this crazy thinking. You know, I have to, I know, that my thinking can get me a little crazy and so I have to tell myself to stop. | |

| Social | • Because you can be so susceptible to infection, that you can isolate yourself. But utilize the Internet, utilize the telephone, utilize ways in which you can reach out to people so you don't, um, feel like you are alone, because you are really not. |

| • I'll be honest, I went online and I looked up as much as I could before anything had happened as far as you know, what is a reconstruction breast gonna look like, and I think I ended up doing myself more harm than good … you can find entirely too much online and it scared the living crap out of me, like that is the most horrific looking breast I've ever seen! |

DISCUSSION

Our study is one of the first that we know of to focus on subjects' perceptions of the benefits and burdens of research participation and how these influence participation and retention in cancer clinical trials. In their seminal work on what makes research ethical, Emanuel, Wendler, and Grady (2000) outlined seven requirements that researchers and IRBs can use to guide the ethical conduct of research. Although a favorable risk/benefit ratio is one of the requirements for ethical research, little evaluative evidence exists to empirically measure what this actually means. The IRB, for example, has a bird's-eye view of one clinical trial at a time and cannot assess the cumulative benefit or burden of multiple trials on any one individual, thus leaving the individual and his or her family to sort out the benefits and burdens they are willing to accept in order to enroll in a clinical trial. In addition, IRB members are asked to objectively assess the risks and benefits of a given study proposal with all eligible participants in mind, but they do not account for each individual patient's experience. In contrast, participants by nature make a subjective assessment on the risks and benefits of study participation. This individual assessment includes their trust in the healthcare providers, what their family or friends think, what their religious views are, or what “suffering” they are able to tolerate.

Respondents reported a range of benefits and burdens associated with research participation. Some of these benefits and burdens appeared to be more direct than others, including access to needed medications that they otherwise might not be able to afford, early detection and monitoring of the disease, potential for remission or cure, and the ability to take control of their lives through actively participating in the trial. Of course, side effects associated with the trial intervention were of immediate concern for all participants. It was not uncommon to hear participants speak about their worry and the fear of the unknown because of their cancer diagnosis but also to worry about other aspects of their care, including economic concerns. Emotional distress is common in patients diagnosed with cancer (Carlson et al. 2004; Zabora et al. 2001). As such, we need more empirical data on how unmet psychological needs influence the benefit–burden perceptions of participants and their willingness to remain enrolled in clinical trials. In addition, it would be important to identify the benefits and burdens that have more direct versus indirect significance for participants.

Several sources of support for decision making about clinical trials or “trial support sources” can influence patients' decisions to participate in research. These include recommendations from providers, support from family and friends, online (Internet) or media information, and spiritual or religious guidance, among other factors. In fact, we found that subjects enrolled in cancer clinical trials rely on multiple sources to assist them in their decision-making processes during the research trial. However, there is a significant gap in our understanding on the quantity and quality of these different sources of trial support and their influence on patients' ability to make decisions related to their care. It is not clear how much patients actually rely on these sources or how helpful they are for informed decision making; importantly, it is not clear whether the sources of trial support paradoxically provide additional benefit or burden in the patient's decision to participate in clinical trials. Our study extends the understanding brought forward by Jenkins and colleagues that probed the general attitudes of 1066 patients regarding their attitudes towards enrolling in a hypothetical randomized control trial by interviewing cancer patients already enrolled in a clinical trial. Interestingly, our sample participants raised the hope that they would be randomized to the active arm of the study and expressed the importance of communication with both their physician and their research nurse.

Nearly three-quarters of our participants rated spirituality as an important component of their lives. Additionally, several participants discussed their faith during the semistructured interviews. As one participant noted, “Everything happens for a reason; that's such the spiritual part of it. There is a plan, there is a reason.” Although having faith in God and having faith in the doctor may be very different for each participant, our qualitative findings regarding spirituality are similar to those in the Daugherty et al. (2005) study, which examined the role of spirituality in terminally ill patients who enroll in cancer clinical trials. In their study, one participant in a Phase I trial expressed their willingness to put their faith in medicine and in God: “I put faith in doctors and God.” Both kinds of beliefs—faith in the medical team and faith in God—are important considerations in research participation decisions. They can coexist equally and vary over time. Together, these views represent not only the expectations of science to mitigate physical and emotional human suffering but also the guidance of and trust in a higher power outside of human agency to care for the spiritual pains that might exist in the participant's life.

Balboni (2007) found that the spiritual needs of advanced cancer patients were minimally or not at all supported by the medical system, yet spiritual support was positively associated with patients' quality of life. Interestingly, this author also reported a correlation between patients' religiousness and the desire for measures to extend life. Our study also builds on the work of Advani and colleagues (2003) at the Duke Cancer Clinic and the Duke Oncology Outreach Clinics, who reported the importance of religion/spiritual beliefs, particularly in African-Americans. In this work, African-Americans were less likely to participate in research if they believed God would determine their fate associated with their disease. Our work, however, recognizes the benefit of religion/spirituality in the lives of those participating in research. Other researchers have found a significantly higher tumor response to treatment in lung cancer patients with a higher spiritual faith, as well as a positive relationship between spiritual faith and survival time. Further work is needed to tease out the importance of spirituality and religion in decision making related to clinical trial recruitment and retention, and, importantly, whether responses to experimental interventions may differ based on spiritual faith.

We would be remiss if we did not mention the therapeutic misconception as it pertains to our findings. Here, the worry centers on whether patients conflate clinical care with clinical research and hold a belief that the research is therapeutic, when in fact it is not (Appelbaum, Roth, and Lidz 1982; Appelbaum et al. 1987). While we did not include an empirical measure to determine whether a therapeutic misconception existed or ask specific questions associated with this phenomenon of interest, it was clear that some study participants focused solely on the benefits of the trial in terms of treatment and potential cure without considering the risks. Thus, in future research, we first need to better understand whether this is a generational issue or whether other factors account for this finding. Second, it is not clear how much involvement patients want in the decision-making process. Some research suggests that human participants are more involved than they want to be in the decisional process (Brown et al. 2007). This raises important questions about shared decision making and whether a passive role in informed consent promotes or undermines the right to self-determination in the consenting process.

On the other hand, the benefits of research participation expressed by the participants in our study are primary to their research experience and may not reflect a therapeutic misconception per se but a way for participants to evaluate research in terms of the kind of patient they want to be. As some of our participants questioned their identity as a research participant (“who am I”?), more conceptual and empirical work on one's self-imaging as a patient-subject would better convey how research participation provides meaning in a different way than to what the patient-subject was previously accustomed. Finally, the model we developed from our semistructured interviews reflects a more in-depth and nuanced view of the benefits and burdens of research participation than previously discussed. Moreover, we are now positioned to empirically test the model in future research. If supported, the model can facilitate communication among investigators, institutional review boards, and patients regarding the potential benefits and burdens related to clinical trial enrollment and ongoing participation.

Limitations

Several limitations associated with our work warrant discussion. First, given the exploratory nature of the study, we only included English-speaking individuals. Thus, we might have missed important cultural aspects associated with individuals speaking other languages, such as Hispanic individuals. Also, because the majority of our sample was Caucasian, female, and of middle age, more research should explore differences by sociodemographics. It would be helpful to know why older adults appear more trusting of their physicians and whether there are any differences in the benefits and burdens of research participation in comparison to their younger cohort. In addition, because our interviews were not held at the time when participants provided informed consent for participation in the cancer clinical trials, our study does not reflect decision making at a particular point in time, but interprets participants' research participation decisions through their memories, reflections, and experiences. Finally, although our sample size was appropriate for qualitative research, we were not able to identify variations in participants' perception of the benefits and burdens based on trial phase, stage of disease, cancer site, or other important factors. Future research with a larger and more diverse sample would help to tease out these issues.

Conclusion

This study articulates the benefits and burdens of cancer research participation through the lens of human participants by evaluating the ethical acceptability of research participation in the voices of those most affected. Future directions include the development of quantitative measures evaluating the benefits and burdens of research participation to further quantify and validate our thematic analyses and model.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Nursing Research, grant 1R21NR010259-01A1. A special thank you to all of the cancer patients enrolled in cancer clinical research and who gave of their time to better understand these issues from their perspectives. The authors also thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments to strengthen the article.

REFERENCES

- Advani AS, Atkeson B, Brown CL, et al. Barriers to the participation of African-American patients with cancer in clinical trials. Cancer. 2003;97:1499–1506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11213. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz C. The therapeutic misconception: Informed consent in psychiatric research. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 1982;5:319–29. doi: 10.1016/0160-2527(82)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz C, Benson P, Winslade W. False hopes and bestdata: Consent to research and the therapeutic misconception. Hastings Center Report. 1987;17:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balboni T, Vanderwerken L, Block S, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associat7ion with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:467–468. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn N. Respondent burden. Presented at Health survey research methods: Second biennial conference (Williamsburg, VA); Washington, DC. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RF, Butow PN, Boyle F, Tattersall MH. Seeking informed consent to cancer clinical trials; Evaluating the efficacy of doctor communication skills training. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;6:507–516. doi: 10.1002/pon.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Amgen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of distress and fatigue in cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;90:2297–2304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage; London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty CK, Fitchett G, Murphy PE, et al. Trusting God and medicine: Spirituality in advanced cancer patients volunteering for clinical trials of experimental agents. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14(2):135–146. doi: 10.1002/pon.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel E, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:2701–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V, Farewell D, Batt L, et al. The attitudes of 1066 patients with cancer towards participation in randomised clinical trials. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;103:1801–1807. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606004. Available at www.bjcancer.com (published online November 30) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe S, Miller F. Rethinking risk-benefit assessment for Phase I cancer trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(19):2987–2990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA. Analyzing & reporting focus groups. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lidz CW, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Renaud M. Therapeutic misconception and the appreciation of risks in clinical trials. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:1689–1697. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissoni P, Messina G, Parolini D, et al. A spiritual approach in the treatment of cancer: Relation between faith score and response to chemotherapy in advanced non small cell lung cancer patients. In Vivo. 2008;22:577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FG, Joffe S. Evaluating the therapeutic misconception. Kennedy Institute of Ethics. 2006;16:353–366. doi: 10.1353/ken.2006.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research . The Belmont report. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Management and Budget . Federal statistics: Coordination, standards, guidelines. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich C, Danis M, Koziol D, Garrett-Mayer E, Hubbard R, Grady C. Does it pay to pay? A randomized trial of prepaid financial incentives and lottery incentives in surveys of nonphysician healthcare professionals. Nursing Research. 2005;54:178–183. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich CM, Wallen GR, Feister A, Grady C. Respondent burden in clinical research: when are we asking too much of subjects? IRB. 2005;27:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Cancer Day: Global action to avert 8 million World cancer day: Global action to avert 8 million cancer-related deaths by 2015. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. [(accessed July 1, 2011)]. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2006/pr06/en. [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevelance of psychosocial distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]