Abstract

Background

Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) is an innate immunity-associated protein known to inhibit HIV transmission, and is thought to inhibit a variety of infectious agents, including human papillomaviruses (HPVs). We aimed to optimize an established ELISA-based SLPI quantification assay for use with oral gargle specimens collected using mouthwash, and to assess preliminary associations with age, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

Methods

Oral gargle supernatants from 50 individuals were used to optimize the Human SLPI Quantikine ELISA Kit. Sample suitability was assessed and quality control analyses were conducted.

Results

Salivary SLPI was successfully recovered from oral gargles with low intra-assay and high inter-individual variability. Initial measurements showed that salivary SLPI varied considerably across individuals, and that SLPI was inversely associated with age.

Conclusions

This optimized assay can be used to examine the role of SLPI in the acquisition of oral HPV and other infections.

Keywords: Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor, SLPI, Innate immunity, Immune system protein, Oral disease, Oral gargle

1. Introduction

Recent evidence suggests that an antimicrobial protein known as secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) may play an important role in the acquisition of oral human papillomaviruses (HPVs) (Woodham et al., 2012; Hoffmann et al., 2013) and the development of head and neck cancer (HNC) (Cordes et al., 2011; Wen et al., 2011). SLPI is a non-glycosylated protein produced by serous and epithelial cells lining mucous membranes (Wahl et al., 1997). Though SLPI has been detected in a variety of secretions, including cervical mucus, seminal fluid, breast milk, tear fluid, sputum, and bronchial secretions, it is found in particularly high concentrations in saliva (Kramps et al., 1984; Wahl et al., 1997).

Similar to a defensin, SLPI contributes to the innate immune response by displaying antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory properties (reviewed in Wahl et al., 1997). Antiviral properties of salivary SLPI have been studied extensively with regard to HIV infection. SLPI has been found to inhibit the HIV virus (Wahl et al., 1997), offering a potential explanation for the low rates of HIV transmission through oral secretions. It has been proposed that SLPI may offer similar protection against other infections, including herpes simplex virus (Fakioglu et al., 2008), Epstein–Barr virus (Tse et al., 2012), and more recently, HPV (Woodham et al., 2012; Hoffmann et al., 2013). Laboratory evidence supports the hypothesis that SLPI protects against HPV16 infection by inhibiting viral entry into epithelial cells (Woodham et al., 2012), and in vivo evidence further demonstrates that SLPI expression is inversely associated with the detection of HPV DNA in HNC tissue (Hoffmann et al., 2013), suggesting that high concentrations of extracellular SLPI may protect against oral HPV infection.

Future epidemiological studies should investigate the role of salivary SLPI in oral HPV acquisition and subsequent HNC risk; however, salivary SLPI has not yet been quantified in oral rinse/gargle specimens, which are used in most oral HPV natural history studies. Thus, the overall aim of this study was to optimize an established ELISA-based SLPI quantification assay for use with oral gargle supernatant specimens collected using mouthwash, with the secondary aim of assessing associations between SLPI and age, smoking status, and alcohol intake.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participant selection and description of experiments

Initially, oral gargles from volunteers (n = 8) were collected for assay development. The supernatants of specimens were used in the assay optimization process to determine an appropriate dilution factor, assess variation in SLPI concentration over time (freshly collected on day 1 and on day 30), and compare fresh versus frozen specimens (freshly collected on day 1 vs. those that were frozen at −80 °C and thawed on day 30). To assess the reliability and repeatability of the newly optimized assay, triplicate measurements were obtained from 14 individuals randomly selected from the United States arm of the HPV Infection in Men [HIM] Study, a multinational, prospective male HPV natural history study (Kreimer et al., 2011), in addition to ten replicates from each of three biospecimen pools. Briefly, volunteers (n = 10) provided oral gargle specimens that were immediately combined to form one large pooled specimen, three aliquots were taken from this pooled specimen to create three equivalent pools, and ten replicates were tested from each pool to assess experimental variability. Archived oral gargle specimens from 32 HIM Study participants were used to describe inter-individual variation in salivary SLPI concentrations detected among healthy adult men and to examine preliminary associations with age, smoking status, and alcohol intake. The University of South Florida Human Subjects Committee approved all HIM Study procedures, and all participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Oral gargle collection and storage

Each oral gargle sample was collected using a 15 mL aliquot of mouthwash (15% alcohol by weight; Up&Up Brand, Target, USA), which was swished around in the mouth for 15 s and gargled in the back of the throat for 15 s (Kreimer et al., 2011). Within 24 h, samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was decanted into a collection tube, and the pellet and supernatant were stored separately at −80 °C until use.

2.3. SLPI assay and optimization for oral gargle specimens

To assess sample suitability, the Human SLPI Quantikine ELISA Kit (DP100, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This solid-phase ELISA-based assay was originally designed to measure SLPI in cell culture supernatants, serum, plasma, and urine; therefore, the assay had to be optimized to accurately quantify SLPI within the supernatant of oral gargle specimens collected using mouthwash. Briefly, RD1Q diluent buffer (100 μL) was added to each well of a 96-well plate. Standards and diluted samples were added in 100 μL volumes and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After washing with wash buffer (6 × 200 μL), aliquots (200 μL each) of the polyclonal antibody were added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The washing step was repeated (6 × 200 μL), substrate solution (200 μL) was added, and the reactions were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. Stop solution (50 μL) was added, and the plate was read after 10 min using a SpectraMax plate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at a wavelength of 450 nm with a correction at 540 nm.

2.4. Dilution factor and standard curve

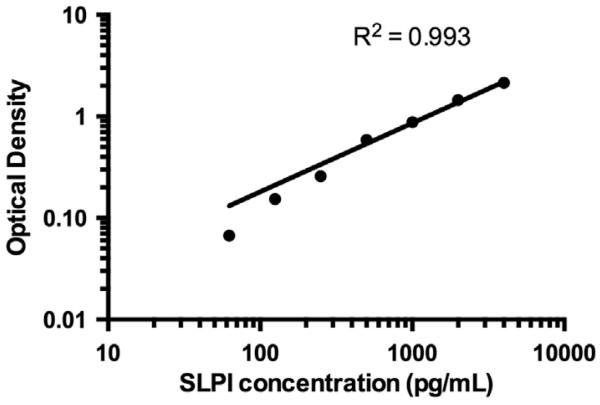

Our first experiment was designed to determine the appropriate dilution factor for the oral gargle supernatant. Each of the eight volunteer samples was concentrated 2:1 as well as diluted 1:4, 1:20, and 1:200 in mouthwash. The 1:200 dilution factor produced samples with optical density (OD) values that fit within the dynamic range of the assay standard curve (Fig. 1); based on these results, all samples were analyzed at a 1:200 dilution.

Fig. 1.

Assay standard curve for a SLPI assay optimized for supernatants of oral gargle specimens. For each assay, a standard curve was constructed by plotting the mean optical density for each standard on the y-axis against the SLPI concentration on the x-axis, with a log–log line fit through the points on logarithmic axes.

Standard curves were constructed by plotting the mean OD for each standard on the y-axis against the SLPI concentration on the x-axis, with a log–log line fit through the points on logarithmic axes. For each assay, the standard curve was used to interpolate SLPI concentrations of diluted gargle specimens (pg/mL), which were then used to estimate SLPI concentrations of the original gargle specimens (ng/mL).

2.5. Statistical analyses

In triplicate and pooled analyses, means, standard deviations, and coefficients of variation (CV%) were calculated to evaluate intra-assay variability (i.e., precision), with acceptable CV values under 10%. Descriptive statistics (dynamic range, interquartile range, mean, standard deviation [SD], and median) for SLPI concentrations in oral gargle specimens (ng/mL) were calculated for the 32 HIM Study participants. As SLPI concentrations were not normally distributed, a nonparametric test (Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient) was used to assess the relationship between continuous values of SLPI and age. To further examine associations between SLPI concentration, age, smoking status, and alcohol intake, sociodemographic and behavioral data were obtained from the risk factor questionnaire utilized in the HIM Study. SLPI concentrations were categorized into quartiles (≤197 ng/mL, 198–348 ng/mL, 349–483 ng/mL, ≥484 ng/mL), age at gargle collection was categorized into one of five groups (≤24 y, 25–34 y, 35–44 y, 45–54 y, and ≥55 y), self-reported smoking status included never, former, or current cigarette smokers, and self-reported alcohol intake was categorized as 0, 1–30, or ≥31 drinks per month. Fisher’s exact tests were used to detect statistically significant relationships between categorical variables. Analyses were performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided and were considered significant at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Variation in salivary SLPI over time and across specimen types

The average concentration of SLPI detected in freshly collected oral gargle specimens (n = 8) was 329.9 ng/mL (SD: 189.3), similar to that of fresh oral gargle specimens (n = 8) collected 30 days later from the same individuals (384.2 ng/mL; SD: 247.1). Oral gargle specimens (n = 8) that were frozen at −80 °C after collection and thawed 30 days later had a lower average SLPI concentration (234.6 ng/mL; SD: 177.1) than freshly collected specimens from the same individuals. On average, 71.7% of the SLPI in the frozen specimens was recovered when compared with fresh specimens (data not shown).

3.2. Reliability and repeatability of the optimized SLPI assay

In the quality control assessment, triplicate and pooled analyses showed acceptable levels of intra-assay variability, with most CV values below 10% (Table 1). In triplicate analyses, three replicates were tested for each of 14 identical samples randomly selected among HIM Study participants. CVs for these triplicate tests ranged from 0.7% to 12.9%, with an average CV of 6.9% across all participants. In pooled analyses, ten replicates were tested for each of the three biospecimen pools. Minimal variation was detected in pooled analyses; CVs ranged from 3.9% to 6.6%, with an average CV of 5.2% estimated across the three pools.

Table 1.

Intra-assay variability of a SLPI assay optimized for the supernatants of oral gargle specimens.

| Triplicate analysisa |

Pooled analysisb |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| n | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| SLPI (ng/mL) | |||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 168.2 | 754.8 | 202.4 | 167.6 | 455.2 | 310.2 | 69.7 | 6.2 | 298.4 | 191.1 | 65.5 | 225.7 | 7.3 | 385.4 | 228.0 | 253.2 | 253.3 |

| SD | 12.1 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 18.1 | 49.1 | 17.7 | 6.3 | 0.8 | 26.9 | 15.4 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 5.3 | 8.9 | 16.8 | 13.1 |

| CV(%) | 7.2 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 5.7 | 9.1 | 12.9 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 9.6 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 6.6 | 5.2 |

Abbreviation: SLPI, secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor; SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation.

Fourteen identical samples were tested three times on one plate to assess intra-assay variability (n = 42).

Three biospecimen pools were tested ten times on one plate to assess intra-assay variability (n = 30).

3.3. SLPI detected in oral gargles of healthy men

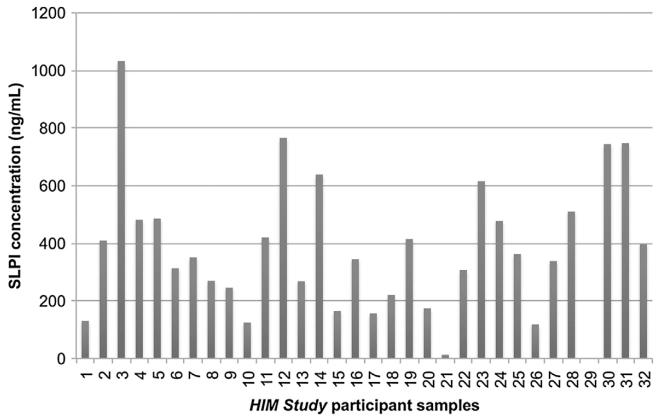

Among 32 HIM Study participants included in this study, the median age was 37 y (range: 22–66), nearly half (46.9%) were single, and one-third (37.5%) were married or cohabiting. Fifteen men (46.9%) reported that they had never smoked, five (15.6%) smoked but had quit, and 12 (37.5%) reported being current smokers. Five men (15.6%) reported that they had not had an alcoholic beverage in the past month, 14 (43.8%) reported having between 1 and 30 drinks per month, and 13 (40.6%) reported having more than 30 drinks per month. SLPI concentrations detected in oral gargle specimens of HIM Study participants ranged from 6.2 to 1032.5 ng/mL, with an average concentration of 376.7 ng/mL (SD: 234.6). Despite this wide range of values (Fig. 2), half of all measurements were detected within the range of 197.3–483.5 ng/mL. An inverse association was detected between continuous measures of SLPI concentration and age (rho = −0.332, p = 0.064). Using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, there was a statistically significant relationship between SLPI concentration and age (p = 0.026); however, no significant associations were observed between SLPI concentration and smoking status (p = 0.954) or alcohol intake (p = 0.964).

Fig. 2.

Inter-individual variation in salivary SLPI concentrations detected among participants of the HIM Study. SLPI concentrations detected in oral gargle specimens varied considerably across individuals. The SLPI concentrations of 32 HIM Study participants ranged from 6.2 to 1032.5 ng/mL, with an average concentration of 376.7 ng/mL (SD: 234.6).

4. Discussion

In this study, we optimized the Human SLPI Quantikine ELISA Kit for use with supernatants of oral gargle specimens collected and archived in mouthwash. Through quality control measures, we demonstrated reliability and repeatability of the optimized assay. Initial measurements in oral gargles showed that salivary SLPI concentrations varied considerably across individuals and that SLPI concentration was inversely associated with age but was not associated with smoking status or alcohol intake. Our preliminary findings demonstrate that production of salivary SLPI declines with age, consistent with the notion that overall immunological responses become impaired throughout the aging process.

With the ability to quantify salivary SLPI in oral gargle specimens, studies with similar archived specimens will be able to investigate the role of SLPI in the acquisition of oral HPV and the risk of developing HPV-related HNC, a cancer that has been increasing in recent decades, particularly among men (Chaturvedi et al., 2011). Recent studies have provided evidence to support the hypothesis that high levels of SLPI protect against HPV infection (Woodham et al., 2012; Hoffmann et al., 2013). Woodham et al. have suggested a mechanism in which SLPI may play a protective role in HPV16 infection by binding in a competitive manner with the putative HPV receptor known as annexin A2 heterotetramer, thereby reducing viral entry into epithelial cells (Woodham et al., 2012). In the first in vivo study to show a correlation between SLPI and HPV infection, Hoffmann et al. found that SLPI protein expression in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma was inversely associated with detection of HPV in tumor tissue, further suggesting that high SLPI levels may protect against HPV infection (Hoffmann et al., 2013). However, to establish a temporal relationship between SLPI and oral HPV infection, studies conducted among cancer-free individuals are needed to examine salivary SLPI within the context of oral HPV acquisition and persistence.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to quantify SLPI in oral gargle specimens using an established assay. However, there are limitations to be considered. Participants were asked to rinse and gargle for 30 s; therefore, differences in gargle duration and intensity may have altered SLPI concentrations and may have affected the variability detected across individuals. Furthermore, by using an alcohol-based mouthwash (15%), we may have unintentionally excluded participants with historically heavy alcohol use and oral ulcers, which may have biased our results. In future studies, alcohol-free mouthwash should be evaluated as an alternative.

4.1. Conclusions

SLPI can be quantified in oral gargle specimens collected using mouthwash. Through its antimicrobial properties, the SLPI protein is thought to inhibit various microbes from infecting mucosal surfaces, perhaps contributing to a reduced risk of developing disease. However, further investigations are needed to determine the impact of SLPI levels on the risk of HPV infection and cancer development in the oral region, particularly among men, who are at greatest risk of developing HPV-related HNC (Chaturvedi et al., 2011).

Acknowledgments

Infrastructure of the HIM Study cohort was supported through a grant from the National Cancer Institute, and the National Institutes of Health (CA R01CA098803 to ARG). The Moffitt Proteomics Facility is supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under Award No. W81XWH-08-2-0101 for a National Functional Genomics Center, the National Cancer Institute under Award No. P30-CA076292 as a Cancer Center Support Grant, and the Moffitt Foundation. CMPC was supported through a cancer prevention fellowship (National Cancer Institute, R25T CA147832).

The authors would like to thank the HIM Study team in the USA (Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL: HY Lin, JL Messina, C Gage, K Eyring, K Kennedy, K Isaacs, A Bobanic, BA Sirak, MR Papenfuss, W Fulp, MB Schabath, AG Nyitray, B Lu), and Lori Hazlehurst for the use of the plate reader.

Role of the funding sources

Infrastructure of the HIM Study cohort was supported through a grant from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (CA R01CA098803 to ARG). The Moffitt Proteomics Facility is supported by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under Award No. W81XWH-08-2-0101 for a National Functional Genomics Center, the National Cancer Institute under Award No. P30-CA076292 as a Cancer Center Support Grant, and the Moffitt Foundation. CMPC was supported through a cancer prevention fellowship (National Cancer Institute, R25T CA147832). These funding agencies had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- SLPI

secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HNC

head and neck cancer

- OD

optical density

- CV

coefficients of variation

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

ARG receives research funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. and is a consultant of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. for HPV vaccines. None of the other authors have conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, Jiang B, Goodman MT, Sibug-Saber M, Cozen W, Liu L, Lynch CF, Wentzensen N, Jordan RC, Altekruse S, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:4294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes C, Hasler R, Werner C, Gorogh T, Rocken C, Hebebrand L, Kast WM, Hoffmann M, Schreiber S, Ambrosch P. The level of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor is decreased in metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2011;39:185. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1006. http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2011.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakioglu E, Wilson SS, Mesquita PM, Hazrati E, Cheshenko N, Blaho JA, Herold BC. Herpes simplex virus downregulates secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor: a novel immune evasion mechanism. J. Virol. 2008;82:9337. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00603-08. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00603-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Quabius ES, Tribius S, Hebebrand L, Gorogh T, Halec G, Kahn T, Hedderich J, Rocken C, Haag J, Waterboer T, Schmitt M, Giuliano AR, Kast WM. Human papillomavirus infection in head and neck cancer: the role of the secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor. Oncol. Rep. 2013;29:1962. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2327. http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/or.2013.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramps JA, Franken C, Dijkman JH. ELISA for quantitative measurement of low-molecular-weight bronchial protease inhibitor in human sputum. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1984;129:959. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreimer AR, Villa A, Nyitray AG, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss M, Smith D, Hildesheim A, Villa LL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Giuliano AR. The epidemiology of oral HPV infection among a multinational sample of healthy men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:172. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0682. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-10-0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse KP, Wu CS, Hsueh C, Chang KP, Hao SP, Chang YS, Tsang NM. The relationship between secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor expression and Epstein–Barr virus status among patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl SM, McNeely TB, Janoff EN, Shugars D, Worley P, Tucker C, Orenstein JM. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) in mucosal fluids inhibits HIV-I. Oral Dis. 1997;3(Suppl. 1):S64. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1997.tb00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Nikitakis NG, Chaisuparat R, Greenwell-Wild T, Gliozzi M, Jin W, Adli A, Moutsopoulos N, Wu T, Warburton G, Wahl SM. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) expression and tumor invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;178:2866. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodham AW, Da Silva DM, Skeate JG, Raff AB, Ambroso MR, Brand HE, Isas JM, Langen R, Kast WM. The S100A10 subunit of the annexin A2 heterotetramer facilitates L2-mediated human papillomavirus infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]