Abstract

Despite sanctions’ impacts on medicine and medical supplies, Cuban health outcomes are comparable to those of developed countries.

The U.S. trade embargo against Cuba, enacted after Fidel Castro’s revolution overthrew the Batista regime, reaches 50 years in 2010. Its stated goal has been to bring democracy to the Cuban people (1), but a 2009 U.S. Senate report concluded “the unilateral embargo on Cuba has failed to achieve its stated purpose” (2). Domestic and international favor for the embargo is not strong (3). Many political and business leaders suggest changing U.S. policy toward Cuba, and President Obama eased travel and remittance restrictions of Cuban-Americans (4, 5). In light of such changes in sentiment and policy, and also the impending overhaul of U.S. health care, we review health consequences and lessons from “one of the most complex and longstanding embargoes in modern history” (2).

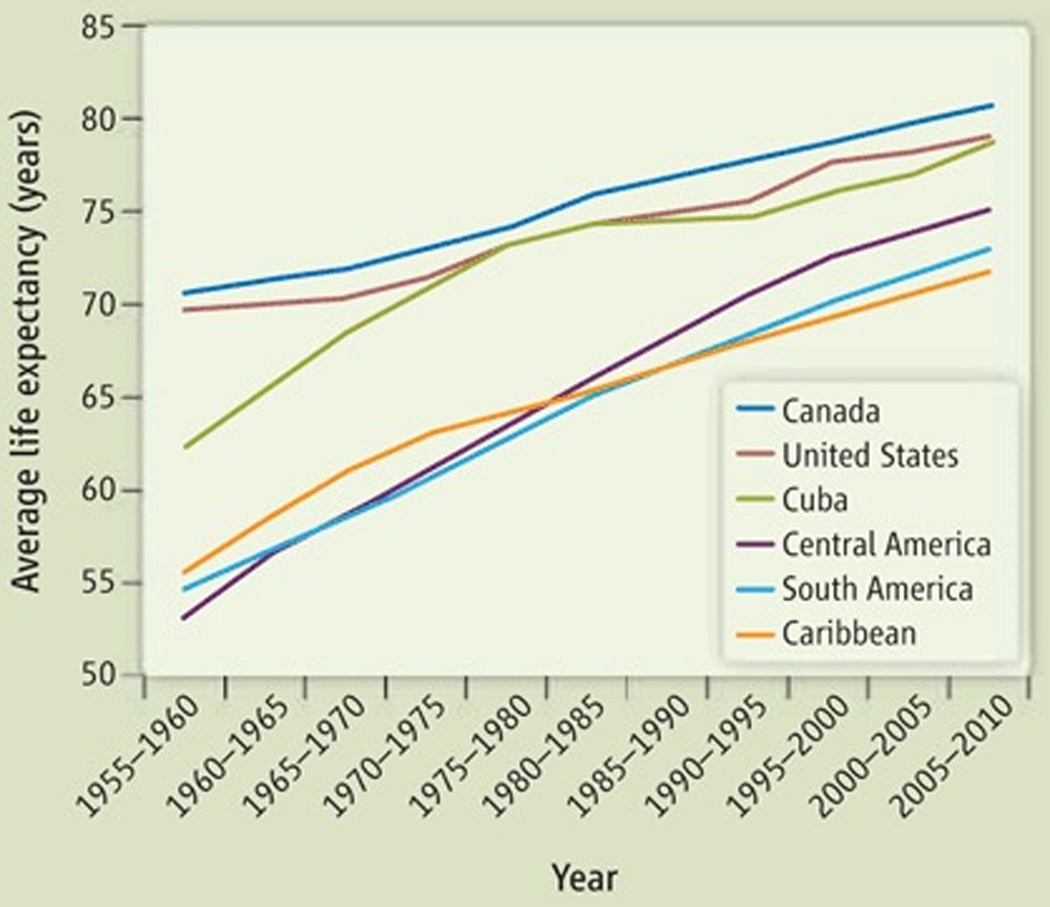

In the decades before 1960, U.S. economic support contributed to Cuba’s achieving average life expectancies that, although they lagged behind North American neighbors United States and Canada, for example, still exceeded other Latin American regions (see figure, right) (Fig. 1). In response to seizure of property owned by U.S. citizens, the United States restricted importation of Cuban sugar in 1960, followed in 1963 by prohibition of trade in food, medicines, and medical supplies (6). The embargo remained relatively unchanged and had little economic impact on Cuba during the Cold War era, mostly because of strong financial support from the Soviet Union (7, 8) (fig. S1). By 1983, Cuba was producing >80% of its medication supply with raw chemical materials acquired from the Soviet Union and Europe, and there were scant reports of medication shortages (9, 10). During the embargo’s first 30 years, Cubans’ average life expectancy increased 12.2 years, comparable to Caribbean and South American regions (see the figure) (11).

Fig. 1. Average life expectancy in Cuba and neighboring countries and regions.

Data from (11). Cuba is included in the Caribbean region.

After the Collapse of the Soviet Union

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989, foreign aid faltered, and Cuba’s economy and health suffered (7, 10, 12) (fig. S1). Adult caloric intake decreased 40%, the percentage of underweight newborns (<2500 grams) increased 23%, anemia was common among pregnant women, and the number of surgeries performed decreased 30% (8, 12). After a decade of steady declines, Cuba’s total mortality rate increased 13% (12).

The U.S. “Torricelli Bill” of 1992 tightened the embargo (13); the number of foreign-based subsidiaries of U.S. companies granted licenses to sell medicines to Cuba declined dramatically (14). The 1996 U.S. “Helms-Burton Act” sought to further penalize foreign countries trading with Cuba (15). By the end of the 20th century, few international pharmaceutical companies supplied essential medicines or raw chemicals to Cuba (10, 14).

Before Torricelli, Cuba imported $719 million worth of goods annually, 90% of which was food and medicines, from U.S. subsidiary companies (12). Between 1992 and 1995, only $0.3 million was approved for sale by U.S. subsidiaries (12). By 1996, the Cuban national formulary of 1300 medical products was reduced to <900 products (12, 16). Medication shortages were associated with a 48% increase in tuberculosis deaths from 1992 to 1993; the number of tuberculosis cases in 1995 was threefold that in 1990 (7, 17, 18). An increase in diarrheal diseases in 1993 and 1994, and an outbreak of Guillain-Barré syndrome in 1994, attributed to Campylobacter-contaminated water, followed a shortage of chlorination chemicals (12). A national epidemic of optic and peripheral neuropathy, which started in 1991, was associated with malnutrition and food shortages (19–22). Although the United States in 2000 ended restrictions on selling food to Cuba (2, 23, 24), restrictions on medicines or medical supplies were not repealed. Cuban imports of medical products from the United States have not increased substantially since 2001 (2). Although establishing causality is difficult, U.S. trade sanctions altered the medication supply and likely had focal, serious consequences on Cubans’ health (17, 19, 25).

Good Health Despite a Weak Economy

However, impacts of sanctions on Cuba’s financial systems, medical supplies, and aggregate health measures appear to be attenuated by their successes in other aspects of health care. Despite the embargo, Cuba has produced better health outcomes than most Latin American countries, and they are comparable to those of most developed countries. Cuba has the highest average life expectancy (78.6 years) and density of physicians per capita (59 physicians per 10,000 people), and the lowest infant (5.0/1000 live births) and child (7.0/1000 live births) mortality rates among 33 Latin American and Caribbean countries (11, 26).

In 2006, the Cuban government spent about $355 per capita on health, 7.1% of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (11, 26). The annual cost of health care for an American was $6714, 15.3% of total U.S. GDP. Cuba also spent less on health than most European countries. But low health care costs alone may not fully explain Cuba’s successes (27), which may relate more to their emphasis on disease prevention and primary health care, which have been cultivated during the U.S. trade embargo.

Cuba has one of the most proactive primary health care systems in the world. By educating their population about disease prevention and health promotion, the Cubans rely less on medical supplies to maintain a healthy population. The converse is the United States, which relies heavily on medical supplies and technologies to maintain a healthy population, but at a very high cost.

The medical education and training system has emphasized primary care since 1960, when Cuba created the Rural Social Medical Service to encourage young physicians to work in rural areas (28). By 1974, all medical graduates were expected to spend up to 3 years practicing community medicine in a rural area (9). Currently, on completion of medical school, 97% of graduates enter a 3-year family medicine residency training, called “integrated general medicine” (10, 29, 30). After family medicine residency, about 65% of physicians will start practicing primary-care medicine, and the remainder will enter specialty training (31).

Cuba has also created a health care infrastructure to support primary care medicine. In 1965, Cuba created a system of community-based polyclinics, which provide primary-care, specialty services, and laboratory and diagnostic testing to a catchment area of 25,000 to 30,000 people (32). Each of the country’s 498 polyclinics tailors medical services and education to the epidemiologic profile of their local population (30). Cuba added another primary-care level in 1984 by establishing neighborhood-based family medicine clinics, called consultorios (29, 31, 33). A polyclinic serves as the organizational hub for 20 to 40 consultorios. Every Cuban is scheduled to visit, or be visited by, a consultorio physician at least yearly (34).

Cuba has some of the highest vaccination rates and percentage of births attended by skilled health workers in the world (26). Health care provided at the consultorios, polyclinics, and larger regional and national hospitals is free to patients, except for some subsidized medications (7, 10, 29). This emphasis on primary care medicine, community health literacy, universal coverage, and accessibility of health services may be how Cuba achieves developed-world health outcomes with a developing-world budget.

Policy Lessons: Travel, Trade, Health Care

A majority of Americans, both Democrats and Republicans, favor improving relations with, or easing sanctions against, Cuba (35). Congress is considering a bill to eliminate travel restrictions (H.R. 874/S. 428), and bills that could lift the trade embargo and facilitate medical imports and travel to Cuba (H.R. 188, H.R. 1530, H.R 1531, and H.R. 2272). The Obama Administration seems willing to sign these bills into law (4). We encourage legislation that at least allows unrestricted travel to Cuba and eliminates medicine and medical supplies from the embargo. Better policy would eliminate the trade embargo.

In March 2010, Congress introduced a bill to strengthen health systems and to expand the supply of skilled health workers in developing countries (H.R. 4933). Cuba has been actively doing this since 1999, when they opened the Latin American School of Medicine to train over 10,000 medical students a year from around the world (36). Cuba also continues to deploy physicians to work in some of the world’s poorest countries, a practice started in 1961.

On the U.S. domestic front, given recent momentum in support of health-care reform, there may be opportunities to learn from Cuba valuable lessons about developing a truly universal health care system that emphasizes primary care. Adopting some of Cuba’s successful health care policies may be the best first step toward normalizing relations. Congress could request an Institute of Medicine study of the successes of the Cuban health system and how to best embark on a new era of cooperation between U.S. and Cuban scientists.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Kassirer, G. Reed, J. Kates, at the Kaiser Family Foundation, and S. Montaña, a Cuban physician, for reviewing drafts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

References and Notes

- 1.U.S. Department of State. U.S.-Cuba Relations. www.state.gov/www/regions/wha/cuba/policy.html.

- 2.Lugar R. Changing Cuba Policy—in the United States National Interest: Staff Trip Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2009. http://lugar.senate.gov/sfrc/pdf/Cuba.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The U.N. General Assembly has voted overwhelmingly against the embargo for the previous 17 years, and the Organization of American States has called the embargo on food and medicines a violation of international law (37, 38). An April 2009 poll showed that the majority of Americans supported lifting the travel ban (64%) and reestablishing diplomatic relations (71%) with Cuba (35).

- 4.Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. Fact Sheet: Reaching out to the Cuban People. [released 13 April 2009]; www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Fact-Sheet-Reaching-out-to-the-Cuban-people.

- 5.Pastrana SJ, Clegg MT. Science. 2008;322:345. doi: 10.1126/science.1162561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of the Treasury. Title 31: Money and Finance, Treasury; Chapt. V–Office of Foreign Assets Control, Part 515, Cuban Assets Control Regulation, Code of Federal Regulation. 2009 www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_07/31cfr515_07.html.

- 7.Rojas Ochoa F, López Pardo CM. Int. J. Health Serv. 1997;27:791. doi: 10.2190/HBXE-6KWM-0H9V-1DCF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nayeri K, López-Pardo CM. Int. J. Health Serv. 2005;35:797. doi: 10.2190/C1QG-6Y0X-CJJA-863H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ubell RN. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983;309:1468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312083092334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Vos P. Int. J. Health Serv. 2005;35:189. doi: 10.2190/M72R-DBKD-2XWV-HJWB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Population Division. Geneva: United Nations; 2009. World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision. http://data.un.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garfield R, Santana S. Am. J. Public Health. 1997;87:15. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuban Democracy Act. Title 22, U.S. Code, § 6001 et seq. http://treas.gov/offices/enforcement/ofac/legal/statutes/cda.pdf.

- 14.Kirkpatrick AF. Lancet. 1996;348:1489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07376-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuban Liberty and Democracy Solidarity (Libertad) Act. Title 22, U.S. Code, Section 6032 et seq. www.state.gov/www/regions/wha/cuba/democ_act_1992.html.

- 16.Bourne PG. Denial of Food and Medicine: The Impact of the U.S. Embargo on Health and Nutrition in Cuba. Washington, DC: American Association for World Health; 1997. http://archives.usaengage.org/archives/studies/cuba.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Public Health. Informe Annual, 1992. Havana, Cuba: Ministry of Public Health; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marrero A, Caminero JA, Rodríguez R, Billo NE. Thorax. 2000;55:39. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuntz D. Int. J. Health Serv. 1994;24:161. doi: 10.2190/L6VN-57RR-AFLK-XW90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Román GC. Neurology. 1994;44:1784. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.10.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Cuba Neuropathy Field Investigation Team. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1176. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Román GC. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995;122:530. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Public Law 106-387–Appendix, Title IX–Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act, § 901, 14 STAT, 1549A. :67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuba then began purchasing food directly from the United States, and by 2007, the United States had become Cuba’s largest supplier of food (39).

- 25.American Public Health Association. The Politics of Suffering: The Impact of the U.S. Embargo on the Health of the Cuban People. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization (WHO) Statistical Information System. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. www.who.int/whosis/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 27.After statistically adjusting Cuban physician salaries (about $216 to $324 per year) to approximate average U.S. primary care wages ($150,000 per year) (8), the cost of providing health care in Cuba increases more than threefold ($1248 per capita), which is comparable to many European countries.

- 28.Ochoa FR. Revist. Cubana Med. Gen. Integr. 2003;19:56. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardelle AJF. Int. J. Health Serv. 1994;24:421. doi: 10.2190/2YG8-0P0C-CCYJ-330N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed G. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008;86:327. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.030508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dresang LT, Brebrick L, Murray D, Shallue A, Sullivan-Vedder L. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2005;18:297. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Márquez M. Lancet. 2009;374:1574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61919-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demers RY, Kemble S, Orris M, Orris P. Fam. Pract. 1993;10:164. doi: 10.1093/fampra/10.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veeken H. BMJ. 1995;311:935. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7010.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.C.N.N. C.N.N. Poll: Three-quarters favor relations with Cuba. [12 April 2009]; http://edition.cnn.com/2009/POLITICS/04/10/poll.cuba/index.html#cnnSTCText. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mullan F. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.United Nations. General Assembly overwhelmingly calls for end to United States embargo of Cuba, United Nations General Assembly, GA/10649. [30 October 2007]; www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2007/ga10649.doc.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walte J. U.S. urged to ease Cuban embargo. USA Today. 1995 Mar 7; [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weissert W. U.S. remains Cuba’s top food source, exported $600M in agricultural products to island in 2007. Associated Press. 2008 Jan 22; [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.