Abstract

At concentrations that produce anesthesia, many barbituric acid derivatives act as positive allosteric modulators of inhibitory GABAA receptors (GABAARs) and inhibitors of excitatory nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs). Recent research on [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB ([3H]R-5-allyl-1-methyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyldiazirinylphenyl)barbituric acid), a photoreactive barbiturate that is a potent and stereoselective anesthetic and GABAAR potentiator, has identified a second class of intersubunit binding sites for general anesthetics in the α1β3γ2 GABAAR transmembrane domain. We now characterize mTFD-MPAB interactions with the Torpedo (muscle-type) nAChR. For nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes, S- and R-mTFD-MPAB inhibited ACh-induced currents with IC50 values of 5 and 10 µM, respectively. Racemic mTFD-MPAB enhanced the equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh to nAChR-rich membranes (EC50 = 9 µM) and inhibited binding of the ion channel blocker [3H]tenocyclidine in the nAChR desensitized and resting states with IC50 values of 2 and 170 µM, respectively. Photoaffinity labeling identified two binding sites for [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the nAChR transmembrane domain: 1) a site within the ion channel, identified by photolabeling in the nAChR desensitized state of amino acids within the M2 helices of each nAChR subunit; and 2) a site at the γ–α subunit interface, identified by photolabeling of γMet299 within the γM3 helix at similar efficiency in the resting and desensitized states. These results establish that mTFD-MPAB is a potent nAChR inhibitor that binds in the ion channel preferentially in the desensitized state and binds with lower affinity to a site at the γ–α subunit interface where etomidate analogs bind that act as positive and negative nAChR modulators.

Introduction

Barbiturates encompass a large group of structurally related compounds that have been used clinically for their anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative/hypnotic, and anesthetic effects (Mihic and Harris, 2011). At clinically relevant concentrations, barbiturates interact with members of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel superfamily, including inhibitory GABAA receptors (GABAARs) and excitatory nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (Krasowski and Harrison, 1999; Rudolph and Antkowiak, 2004). Barbiturates act as positive allosteric modulators of GABAARs (MacDonald and Olsen, 1994; Löscher and Rogawski, 2012), the in vivo target for many of the anesthetic actions of pentobarbital (Zeller et al., 2007). On the other hand, barbiturates act as noncompetitive/allosteric inhibitors of muscle-type nAChRs, as shown using electrophysiological (Gage and McKinnon, 1985; Dilger et al., 1997; Krampfl et al., 2000) and ion flux assays (de Armendi et al., 1993).

Barbiturates act as state-dependent inhibitors of the Torpedo (muscle-type) nAChR, with most having higher affinity for the open channel state than for the resting, closed channel state (de Armendi et al., 1993). However, amobarbital, one of the most potent barbiturate inhibitors, binds with high affinity in the absence of agonist to one (Arias et al., 2001) or two (Dodson et al., 1987) sites per nAChR, with binding affinity reduced by >100-fold in the presence of agonist. Amobarbital and most barbiturates probably bind to a site in the nAChR ion channel, since they fully inhibit the binding of nAChR channel blockers (Cohen et al., 1986; Arias et al., 2001). However, there may be additional nAChR binding sites, since the N-methylated analog of barbital enhanced [14C]amobarbital binding, whereas barbital fully inhibited binding (Dodson et al., 1990). In addition, in the presence of agonist, [14C]amobarbital binds with low affinity to approximately 10 sites per nAChR (Arias et al., 2001).

Cryoelectron microscopy analyses of the Torpedo [(α)2βγδ] nAChR provided the first definition of the three-dimensional structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel (Unwin, 2005), with each subunit made up of an N-terminal extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain (TMD) made up of a loose bundle of four α helices (M1–M4), and a cytoplasmic domain composed of the amino acids between the M3 and M4 helices. The transmitter binding sites are in the extracellular domain at the α–γ and α–δ subunit interfaces. The M2 helices from each subunit associate around a central axis to form the ion channel, and the M1, M3, and M4 helices form an outer ring partly exposed to lipid.

Photoaffinity labeling studies have identified three classes of binding sites for allosteric modulators in the Torpedo nAChR TMD: 1) sites in the ion channel for “classical” cationic channel blockers, including chlorpromazine (Revah et al., 1990; Chiara et al., 2009) and tetracaine (Gallagher and Cohen, 1999), as well as uncharged, hydrophobic drugs, including the general anesthetics etomidate and propofol (Pratt et al., 2000; Ziebell et al., 2004; Nirthanan et al., 2008; Hamouda et al., 2011; Jayakar et al., 2013); 2) a site at the γ−α subunit interface that binds positive (Nirthanan et al., 2008) and negative modulators (Hamouda et al., 2011; Jayakar et al., 2013); and 3) a site for negative modulators, including halothane and propofol, within the δ subunit helix bundle (Chiara et al., 2003; Arevalo et al., 2005; Hamouda et al., 2008; Jayakar et al., 2013).

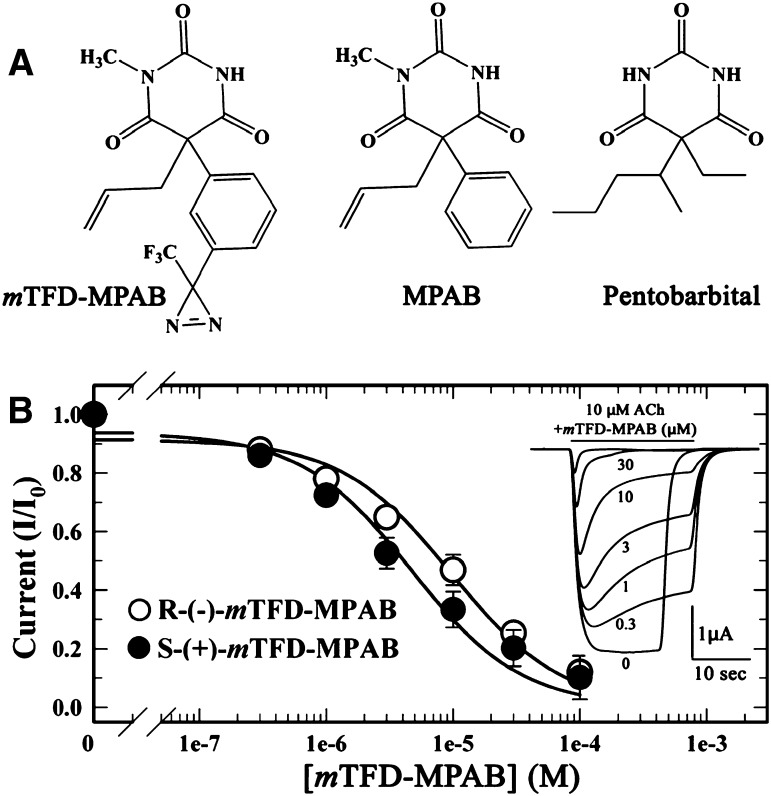

In this study, we used mTFD-MPAB [5-allyl-1-methyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyldiazirynylphenyl)barbituric acid; Fig. 1A)], a recently developed photoreactive barbiturate general anesthetic that binds to intersubunit sites in the α1β3γ2 GABAAR TMD (Savechenkov et al., 2012; Chiara et al., 2013), to identify barbiturate binding site(s) in the Torpedo nAChR. Although R-mTFD-MPAB is 10-fold more potent than S-mTFD-MPAB as an anesthetic and GABAAR potentiator (Savechenkov et al., 2012), we find that mTFD-MPAB is a potent inhibitor of Torpedo nAChR, with the S-isomer 2-fold more potent than the R-isomer. mTFD-MPAB binds with high affinity in the nAChR ion channel in the desensitized state, and direct photolabeling identified the amino acids contributing to the [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB/pentobarbital binding sites in the ion channel and at the γ−α subunit interface.

Fig. 1.

(A) Structures of TFD-MPAB, MPAB, and pentobarbital. (B) mTFD-MPAB inhibition of Torpedo nAChR responses. Oocytes injected with wild-type Torpedo nAChR mRNA at a ratio of 2α:1β:1γ:1δ were voltage clamped at −50 mV, and currents elicited by 10 µM ACh (approximately EC20) were recorded in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of R- or S-mTFD-MPAB. Each drug concentration was tested at least three times on two oocytes. Representative current traces for R-mTFD-MPAB are plotted in the inset. The peak currents at each inhibitor concentration, normalized to the current elicited by 10 µM ACh alone, are plotted (average ± S.E.). When fit to z, IC50 values for R- and S-mTFD-MPAB are 10 ± 2 and 5 ± 1 µM, respectively.

Materials and Methods

nAChR-rich membranes, isolated from Torpedo californica electric organs (Aquatic Research Consultants, San Pedro, CA) as described (Middleton and Cohen, 1991), contained 1.2–1.7 nmol [3H]ACh binding sites per milligram of protein, as determined by equilibrium centrifugation. MPAB [(5-allyl-1-methyl-5-phenyl)barbituric acid], R- and S-mTFD-MPAB, and [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB (38 Ci/mmol) were synthesized as described (Savechenkov et al., 2012). Pentobarbital and phencyclidine (PCP) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). [3H]Tenocyclidine ([3H]TCP; 57.6 Ci/mmol) was from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA), and [3H]tetracaine (30 Ci/mmol) was from Sibtech (Newington, CT).

Radioligand Binding Assays.

The equilibrium binding of [3H]acetylcholine ([3H]ACh), [3H]TCP, and [3H]tetracaine to nAChR-rich membranes in Torpedo physiologic saline (TPS; 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) was determined using a centrifugation assay (Hamouda et al., 2011). Binding assays were performed at the following final concentrations: for [3H]ACh: 40 nM ACh binding sites, 15 nM radioligand, and 0.5 mM diisopropylphosphofluoridate to inhibit acetylcholinesterase; for [3H]TCP: 1 μM ACh binding sites, 15 nM radioligand, and 1 mM carbamylcholine (Carb) to stabilize the nAChR in the desensitized state; and for [3H]tetracaine: 1 μM ACh binding sites, 9 nM radioligand, and 5 μM α-bungarotoxin (α-BgTx) to stabilize the nAChR in the resting state. Membrane suspensions were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of MPAB, mTFD-MPAB, or pentobarbital. The bound and free 3H were separated by centrifugation (18,000g for 1 hour) and then quantified as counts per minute by liquid scintillation counting. The nonspecific binding of [3H]ACh, [3H]tetracaine, and [3H]TCP to nAChR-rich membranes was determined in the presence of 100 μM Carb, tetracaine, or proadifen, respectively. Stock solutions of pentobarbital (3 mM) were in TPS. Stock solutions of TFD-MPAB and MPAB were prepared at 50 mM in ethanol; for those assays, the final concentration of ethanol was 1% (v/v), a concentration that reduced [3H]tetracaine and [3H]TCP and increased [3H]ACh binding by <10%.

For each radioligand, fx, the specifically bound 3H (cpmtotal − cpmnonspecific) in the presence of competitor at concentration x, was normalized to f0, the specifically bound 3H in the absence of competitor. Data were fit using SigmaPlot 11 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA) to the following single site model in eq. 1:

| (1), |

where IC50 is the concentration of competitor that inhibits 50% of the total specific binding.

Electrophysiological Recording.

The effect of mTFD-MPAB on ACh-induced current responses for Torpedo nAChR expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes was examined using standard two-electrode voltage clamp techniques as described (Hamouda et al., 2011). Oocytes were obtained from adult female X. laevis using animal protocols approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care. Oocytes were injected with approximately 25 ng total mRNA mixed at a ratio of 2α:1β:1γ:1δ.

At room temperature and under continuous perfusion with ND96 (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5), oocytes were voltage clamped at −50 mV using an Oocyte Clamp OC-725C (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), and ACh (10 μM) ± mTFD-MPAB was applied for 20-second intervals with an approximately 3-minute wash between applications. ACh-induced currents were digitized using a Digidata 1322A (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and analyzed using Clampex/Clampfit 8.2 (Axon Instruments) and SigmaPlot 11 software. Peak currents were normalized to the peak current elicited by 10 μM ACh alone and were fit using eq. 1. R- and S-TFD-MPAB stocks were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide at a concentration of 100 mM and diluted in ND96 to the desired final concentrations. At the highest mTFD-MPAB concentrations tested, dimethylsulfoxide was at 0.1% (v/v), a concentration that altered ACh responses by <5%.

[3H]R-mTFD-MPAB Photolabeling and Gel Electrophoresis.

[3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabelings of nAChR-rich membranes at analytical (150 pmol ACh binding sites per condition) and preparative (15 nmol ACh binding sites per condition) scales were performed using previously described photolabeling techniques (Nirthanan et al., 2008). Briefly, nAChR-rich membranes (3 µM ACh sites, 2 mg protein/ml in TPS supplemented with 1 mM oxidized glutathione, an aqueous scavenger) were incubated with 1 µM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB for 40 minutes at 4°C in the absence or presence of other drugs and then irradiated on ice with a 365 nm UV lamp (model EN-280L; Spectronics Corporation, Westbury, NJ) for 30 minutes at a distance of <2 cm. Photolabeled nAChR-rich membranes were resolved on 1.5-mm thick, 8% polyacrylamide/0.33% bis-acrylamide gels, and the polypeptides were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Amresco, Solon, OH; 0.25% w/v in 45% methanol and 10% acetic acid).

For analytical labeling, [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation into individual polypeptides was visualized by fluorography and quantified by liquid scintillation counting of excised gel bands (Middleton and Cohen, 1991). For photolabeling on a preparative scale, bands containing the nAChR subunits were excised from the stained, 8% polyacrylamide gels. The subunits were recovered by passive elution, concentrated to a final volume of 300 μl using centrifugal filtration (Vivaspin 15 Mr 5000 concentrators; Vivascience, Edgewood, NJ), acetone precipitated (75% acetone at −20°C, overnight), and resuspended in digestion buffer (15 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.1). Alternatively, gel bands for the nAChR α and γ subunits were transferred to separate 15% polyacrylamide gels and subjected to in-gel digestion with 100 μg Staphylococcus aureus endoproteinase Glu-C (V8 protease) to generate large, nonoverlapping subunit fragments (αV8-20, αV8-18, αV8-10, γV8-24, γV8-14) (White and Cohen, 1988; Blanton and Cohen, 1994), which were recovered from the mapping gel bands and resuspended in digestion buffer.

Enzymatic Digestions.

All enzymatic digestions were performed at room temperature. The δ subunit, the αV8-20 fragment (beginning at αSer173 and containing segment C of the agonist binding sites and the αM1, αM2, and αM3 helices), and the γV8-24 fragment (beginning at γAla167 and containing the γM1, γM2, and γM3 helices) were digested for 2 weeks with 0.5 unit Lysobacter enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C (EndoLys-C; Roche, Indianapolis, IN) or for 2 days with 1 μg EndoLys-C (6.3 unit/mg; Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ). The nAChR α and β subunits and the αV8-10 fragment (beginning at αAsn338 and containing the αM4 helix) were diluted with 0.5% Genapol (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) in 50 mM NH4HCO3 buffer (pH 8.1) to reduce the SDS concentration to <0.02%. Each sample was treated with 200 μg of L-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethylchloromethylketone–treated trypsin (Worthington Biomedical Corporation, Lake Township, NJ) in CaCl2 (final concentration of 0.4 mM), and digestion was allowed to proceed for 8 hours (β subunit) or 2 days (α subunit and αV8-10). The nAChR β, γ, and δ subunits were digested for 2 days with 200 μg of V8 protease. The EndoLys-C digests of the δ subunit and trypsin digests of the β subunit were resolved on small pore (16.5% T, 6% C) Tricine (Sigma-Aldrich) SDS-PAGE gels (Schägger and von Jagow, 1987; Arevalo et al., 2005). The β and δ subunit fragments recovered from the Tricine gels and the other subunit digests were further purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (rpHPLC).

HPLC Purification and Sequence Analyses.

We performed rpHPLC and protein microsequencing as described (Nirthanan et al., 2008; Hamouda et al., 2011). [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB–labeled subunit fragments were purified on a Brownlee Aquapore BU-300 column (PerkinElmer), with material eluted at 0.2 ml/min using a nonlinear gradient increasing from 25% to 100% acetonitrile/isopropanol (3:2, 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid) over 100 minutes. The elution of peptides was monitored by the absorbance at 210 nm, and the elution of 3H was determined by liquid scintillation counting of 10% aliquots of each fraction.

rpHPLC fractions were loaded onto trifluoroacetic acid–treated glass fiber or polyvinylidene difluoride filters that were then treated with Biobrene (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and sequenced on a PROCISE 492 protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems). For some samples, sequencing was interrupted at a specific cycle, and the filter was treated with o-phthalaldehyde (OPA). OPA reacts with primary amines, and this treatment prevents further sequencing of any peptide on the filter that does not contain proline (a secondary amine) at this cycle (Brauer et al., 1984; Middleton and Cohen, 1991). For each cycle of Edman degradation, one-sixth was used for amino acid identification/quantification and five-sixths were used for 3H counting. The mass [f(x), in picomoles] of detected phenylthiohydantoin–amino acid derivative in cycle (x) was fit to the equation f(x) = I0Rx to calculate the initial mass of the peptide sequenced (I0) and the repetitive yield of Edman degradation (R), and then the photolabeling efficiency (in cpm/pmol) was calculated using the equation

Computational Analyses.

A T. californica nAChR homology model was constructed based on the cryoelectron microscopy–derived structure of Torpedo marmorata nAChR [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 2BG9; Unwin, 2005] using the Discovery Studio (Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA) software package. The CDOCKER module (Wu et al., 2003) was used to dock R-mFTD-MPAB in binding site spheres (radius = 20 Å) centered as follows: 1) in the nAChR ion channel at the level of M2-9/13, or 2) in the TMD at the γ–α subunit interface and containing amino acids from αM1 (αPro211–αTyr234), αM2 (αThr244–αSer266), γM3 (γSer308–γLys285), and γM2 (γCys252–γLeu277). Twenty randomly distributed replicas of R-mFTD-MPAB were seeded in the center of the binding site spheres, and CDOCKER was configured to generate 20 ligand conformations from each seeded R-mFTD-MPAB replica and to refine the 20 lowest-energy docking solutions for each generated ligand conformation. Docking results within the ion channel and at the γ–α subunit interface are shown as Connolly surface representations (1.4 Å diameter probe) of the ensemble of the 160 and 300 lowest-energy docking solutions, respectively.

A homology model of the T. californica nAChR TMD was constructed based on the structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans glutamate-gated chloride channel, GluCl (PDB ID 3RHW; Hibbs and Gouaux, 2011), which differs from the cryoelectron microscopy–derived nAChR structure in the vertical positioning of amino acids in the M2 and M3 helices relative to the M1 helices and may be a better representation of the locations of amino acids in the nAChR TMD (Mnatsakanyan and Jansen, 2013). The T. californica nAChR and GluCl sequences were aligned through the M1 and M2 helices by use of the conserved Pro residues in M1 and at the end of M2 (M2-23). Since no significant identity existed between the M3 helices of GluCl and the nAChR subunits, a secondary/tertiary structural alignment was made between GluCl and the neuronal β2 nAChR TMD NMR structure (PDB ID 2LM2; Bondarenko et al., 2012) using the Superimpose Proteins function of Discovery Studio, and the resulting sequence alignment was combined with a sequence alignment between Torpedo nAChR subunit TMD sequences and neuronal β2 nAChR TMD that share >50% identity. The final TMD alignment between GluCl and Torpedo nAChR subunits necessitated a one-residue deletion in the αM1-M2 loop (after αPro236) and a one-residue insertion in the M2-M3 loop (αSer269/γLeu278). The resulting T. californica nAChR homology model was placed within a computer-generated membrane force field and energy minimized for 20 cycles, allowing for relaxation of any high-energy interactions induced by residue replacement.

Results

mTFD-MPAB Inhibition of Torpedo nAChR.

Since R-mTFD-MPAB is >10-fold more potent than S-mTFD-MPAB as an anesthetic and GABAAR potentiator (Savechenkov et al., 2012), we examined the actions of both enantiomers on Torpedo nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. In the absence of agonist, neither enantiomer elicited a current response. When coapplied with ACh at 10 µM (EC20), R- and S-mTFD-MPAB each produced reversible, concentration-dependent inhibition of ACh responses with IC50 values of 10 ± 2 µM and 5 ± 1 µM, respectively (Fig. 1B). Since the enantiomers were of similar potency as nAChR inhibitors and the resolved isomers were available only in limited supply, nonradioactive, racemic mTFD-MPAB was used in radioligand binding and photolabeling experiments.

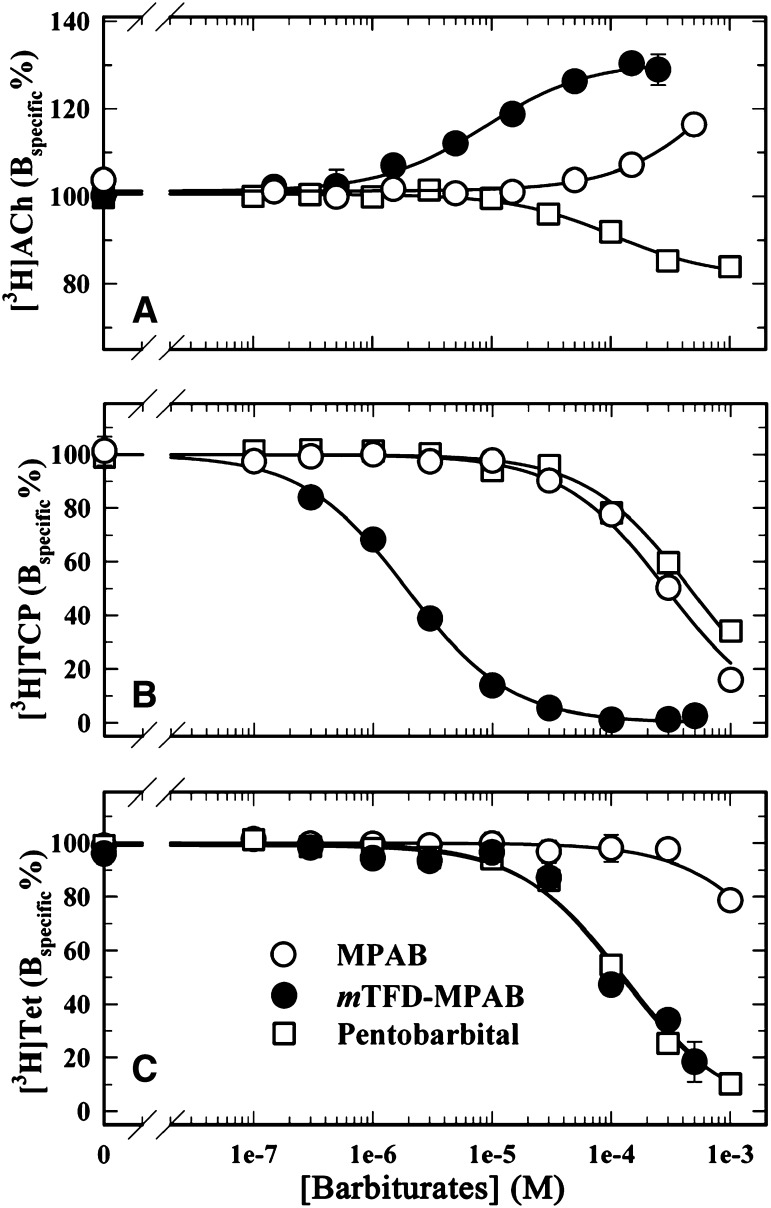

To characterize mTFD-MPAB interactions with the transmitter binding sites, we compared its effects on the equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh to nAChR-rich membranes with those of pentobarbital, which were previously characterized (Dodson et al., 1987; Roth et al., 1989), and with MPAB, which lacks the photoreactive trifluoromethyldiazirynyl group (Fig. 1A). Under our assay conditions, [3H]ACh occupied approximately 20% of the transmitter binding sites, which allowed the detection of either reduction or enhancement of [3H]ACh binding affinity. Consistent with previous results, pentobarbital at high concentrations reduced [3H]ACh binding by only approximately 20% (IC50 = 107 ± 24 μM) (Fig. 2A). By contrast, mTFD-MPAB increased [3H]ACh binding maximally by 30% (EC50 = 9 ± 1 μM), similar to the maximal increase produced by proadifen, a classic desensitizing, aromatic amine noncompetitive antagonist (Boyd and Cohen, 1984). MPAB at 600 μM increased [3H]ACh binding by approximately 20%.

Fig. 2.

mTFD-MPAB, MPAB, and pentobarbital modulation of the equilibrium binding of [3H]ACh (A), [3H]TCP (+Carb) (B), and [3H]tetracaine (+α-bungarotoxin) (C) to the Torpedo nAChR. Binding was determined using a centrifugation assay. For each experiment, the data were normalized to the specific binding in the absence of competitor. Total and nonspecific binding was 6071 ± 39 and 80 ± 9 cpm for [3H]ACh, 12,878 ± 270 and 1820 ± 20 cpm for [3H]TCP, and 15,681 ± 249 and 7420 ± 77 cpm for [3H]tetracaine. The nonspecific binding of [3H]ACh, [3H]TCP, or [3H]tetracaine was determined in the presence of 0.1 mM Carb, proadifen, or tetracaine, respectively. Binding was determined in the presence of 1% ethanol, a concentration that reduced the total and nonspecific binding of [3H]TCP and [3H]tetracaine by <10% and increased the binding of [3H]ACh by <10%.

We also characterized the effects of the barbiturates on the binding of cationic ion channel blockers that bind in the ion channel preferentially in the resting, closed channel state ([3H]tetracaine; Middleton et al., 1999) or in the desensitized state ([3H]TCP, a PCP analog; Katz et al., 1997; Arias et al., 2003, 2006). Binding assays were performed in the presence of Carb, an agonist that stabilizes nAChRs in the desensitized state, or α-BgTx, a competitive antagonist that stabilizes the nAChR in the resting state. For Torpedo nAChRs in the desensitized state (+Carb), mTFD-MPAB inhibited [3H]TCP binding with an IC50 value of 2 ± 0.2 μM (Fig. 2B). For nAChRs in the resting state (+α-BgTx), mTFD-MPAB inhibited [3H]tetracaine binding with an IC50 value of 130 ± 20 μM (Fig. 2C) and [3H]TCP with an IC50 value of 176 ± 10 μM (data not shown). Since high concentrations of mTFD-MPAB inhibited specific binding of the radioligands by >95%, the mechanism of inhibition appeared competitive. Although mTFD-MPAB bound with approximately 70-fold higher affinity to nAChR in the desensitized state than in the resting state, pentobarbital was approximately 3-fold more potent as an inhibitor of channel blocker binding in the resting state. In the presence of α-BgTx, pentobarbital inhibited [3H]tetracaine binding with an IC50 value of 123 ± 10 μM (Fig. 2C) and [3H]TCP with an IC50 value of 198 ± 22 μM (not shown). For [3H]TCP (+Carb), the IC50 value was 450 ± 35 μM (Fig. 2B). Similar to mTFD-MPAB, MPAB was more potent as an inhibitor in the desensitized state (IC50 = 286 ± 25 μM) than in the resting state (at 1 mM, <20% inhibition of [3H]tetracaine binding), but of much lower potency.

Photoincorporation of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB into the Torpedo nAChR.

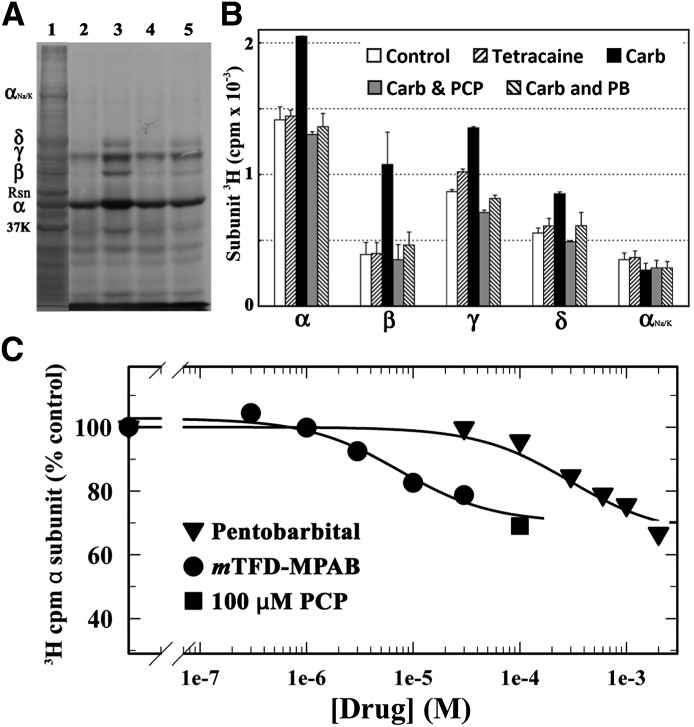

nAChR-rich membranes were photolabeled, on an analytical scale, with 1 µM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the absence or presence of nAChR ligands. The photolabeled membranes were resolved by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A, lane 1), and covalent incorporation of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB into individual polypeptides was evaluated by fluorography (Fig. 3A, lanes 2–5) and liquid scintillation counting of excised gel bands (Fig. 3B). In the absence of other drugs (Fig. 3A, lane 2), [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB was photoincorporated most efficiently into the nAChR α and γ subunits, and also into the β and δ subunits and polypeptides from contaminating membranes [calelectrin (37K) and the Na+/K+-ATPase α subunit (αNaK)]. Photoincorporation into each nAChR subunit was enhanced in nAChRs photolabeled in the desensitized state (+Carb) compared with the resting state (no drug added), and that agonist-enhanced photolabeling was inhibitable by PCP and by pentobarbital. Tetracaine had no effect on nAChR subunit labeling when nAChRs were photolabeled in the absence of agonist (Fig. 3B). To further characterize the pharmacological specificity of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation at the subunit level, we examined the concentration dependence of nonradioactive mTFD-MPAB or pentobarbital inhibition of subunit photolabeling when nAChRs were photolabeled in the desensitized state. Consistent with the concentration dependence of inhibition for [3H]TCP binding, mTFD-MPAB and pentobarbital inhibited α subunit photolabeling with IC50 values of 8 ± 2 µM and 300 ± 70 µM (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Photoincorporation of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB into Torpedo nAChR. Fluorographic (A) and liquid scintillation counting (B) determination of 3H incorporation into nAChR-rich membranes photolabeled on an analytical scale with 1 µM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the absence of other drugs (lane 2) or in the presence of the following: 1 mM Carb (lane 3), 1 mM Carb + 0.1 mM PCP (lane 4), or 1 mM Carb + 1 mM pentobarbital (lane 5). After duplicate samples were resolved on parallel SDS-PAGE gels and stained with Coomassie blue (A, lane 1), polypeptide bands were excised from one gel for 3H determination while the second gel was prepared for fluorography before gel bands were excised for 3H determination. (B) The average cpm ± S.E. of both gels were plotted. The electrophoretic mobilities of the nAChR α, β, γ, and δ subunits, calectrin (37K), rapsyn (Rsn), and the Na+/K+-ATPase α subunit (αNa/K) are indicated. (C) Inhibition of nAChR desensitized state photolabeling (α subunit) by nonradioactive mTFD-MPAB (●), pentobarbital (▾), or 100 μM PCP (▪). When data were fit to eq. 1 with PCP defining nonspecific subunit photolabeling, mTFD-MPAB and pentobarbital inhibited photolabeling with IC50 values of 7.5 ± 1.9 and 295 ± 69 μM, respectively. Similar IC50 values were also calculated for other nAChR subunits (not shown). PB, pentobarbital.

Mapping [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB Photoincorporation within nAChR α Subunit Fragments.

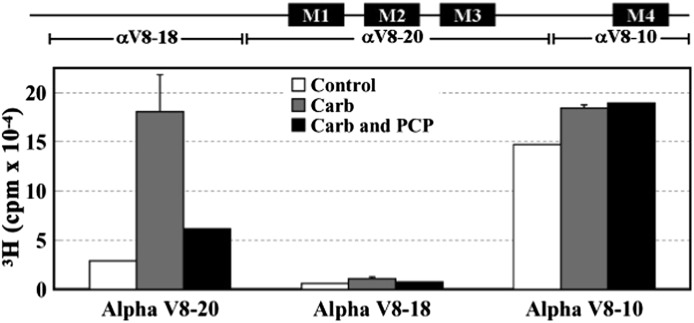

In-gel digestion of photolabeled α subunits with V8 protease was used to localize [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation within three large, nonoverlapping α subunit fragments: a 20-kDa fragment (αV8-20, containing agonist binding site segment C and the transmembrane M1–M3 helices), an 18-kDa fragment (αV8-18, containing most of the extracellular domain including agonist binding site segments A and B), and a 10-kDa fragment (αV8-10, containing part of the intracellular domain and the transmembrane M4 helix) (White and Cohen, 1988; Blanton and Cohen, 1994). In the absence or presence of Carb, [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporated in αV8-20 and αV8-10 with little, if any, labeling of αV8-18 (Fig. 4). [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation within αV8-20 was approximately 6-fold higher in the presence of Carb (desensitized state) than in its absence (resting state), and PCP inhibited that agonist-enhanced photolabeling. By contrast, photoincorporation within αV8-10 varied by <20% in the absence or presence of agonist or PCP.

Fig. 4.

[3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation into nAChR α subunit fragments. Torpedo nAChR-rich membranes were photolabeled with 1 μM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the absence or presence of other ligands, and the polypeptides were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The stained bands containing nAChR α subunits were excised and transferred to a 15% acrylamide mapping gel and subjected to in-gel digestion with V8 protease to generate large subunit fragments that were visualized by GelCode Blue. The 3H incorporation within the excised gel bands was determined by liquid scintillation counting. The locations of the subunit fragments within the α subunit primary structure are indicated above the graph. Data from two photolabeling experiments are shown in the absence (control) or presence of Carb and in the presence of Carb ± PCP. Data for Carb conditions are the average ± S.D. from the two experiments.

State-Dependent Photolabeling in the Ion Channel.

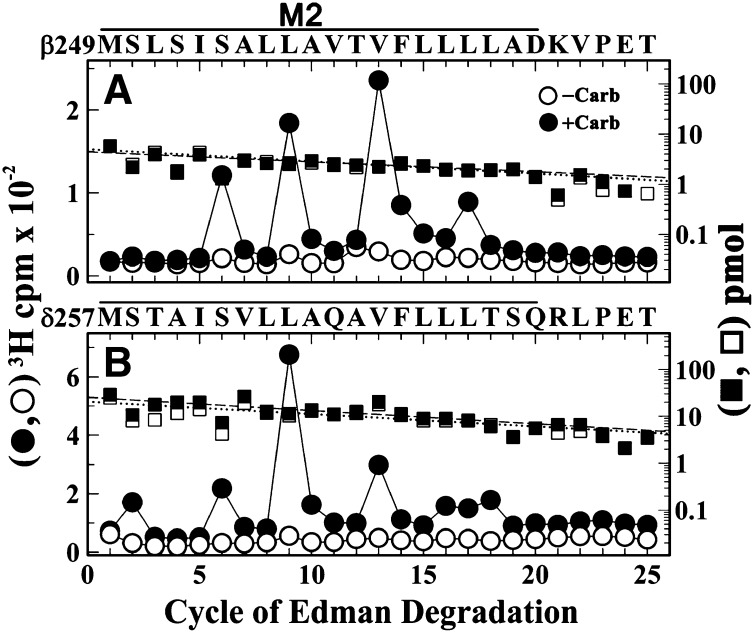

The results of the binding assays and the pharmacological specificity of nAChR photolabeling at the level of intact subunits or αV8-20 predict that [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB binds and photolabels amino acids in the nAChR ion channel in a state-dependent manner. To identify the amino acids photolabeled within the ion channel, nAChR-rich membranes were photolabeled, on a preparative scale, with 1 µM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the absence and presence of Carb, and subunit fragments beginning at the N termini of the βM2 and δM2 helices were isolated for amino acid sequence analysis. In the desensitized state (+Carb), [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeled amino acids facing the channel lumen at positions extending from position M2-2, near the cytoplasmic end, to M2-17 (Fig. 5). In the nAChR resting state, photolabeling of any of those residues, if it occurred, was at <10% the efficiency of labeling in the desensitized state. Within βM2 (Fig. 5A), [3H]mTFD-MPAB photolabeled βM2-9 (βLeu257) and βM2-13 (βVal261) most efficiently, with additional labeling at βM2-6 (βSer254) and βM2-17 (βLeu265). Within δM2, δM2-9 was labeled most efficiently, with δM2-2 (δSer258), δM2-6 (δSer262), and δM2-13 (δVal269) also photolabeled (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Agonist-enhanced [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling in βM2 and δM2. 3H (○, ●) and phenylthiohydantoin–amino acids (□, ▪) released during sequence analyses of fragments beginning at the N termini of βM2 (A) and δM2 (B) isolated (Hamouda et al., 2011) by SDS-PAGE and rpHPLC from trypsin or EndoLys-C digests of subunits from nAChRs photolabeled at a preparative scale with 1 µM [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the absence (○, □) or presence (●, ▪) of 1 mM Carb. (A) The fragment beginning at βMet249 [I0 = 5 (□) and 4 (▪) pmol] was the only sequence detected. The peaks of 3H release in cycles 6, 9, 13, and 16 indicate [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling (+Carb/−Carb, in counts per minute per picomole) at βSer254 (βM2-6, 6/0.3), βLeu257 (βM2-9,11/0.8), βVal261 (βM2-13, 16/<0.8), and βLeu265 (βM2-17, 4/<0.8). (B) The fragment beginning at δMet257 [I0 = 21 (□) and 26 (▪) pmol] was the primary sequence, with a contaminating fragment beginning at δAsn437 (I0 = 7 and 15 pmol). The peaks of 3H release in cycles 2, 6, 9, and 13 indicate photolabeling (+Carb/−Carb, in counts per minute per picomole) at δSer258 (δM2-2, 1/<0.2), δSer262 (δM2-6, 2/0.1), δLeu265 (δM2-9, 8.4/0.4), and δVal269 (δM2-13, 3.7/0.1).

Effects of PCP and Pentobarbital on [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB Ion Channel Photolabeling.

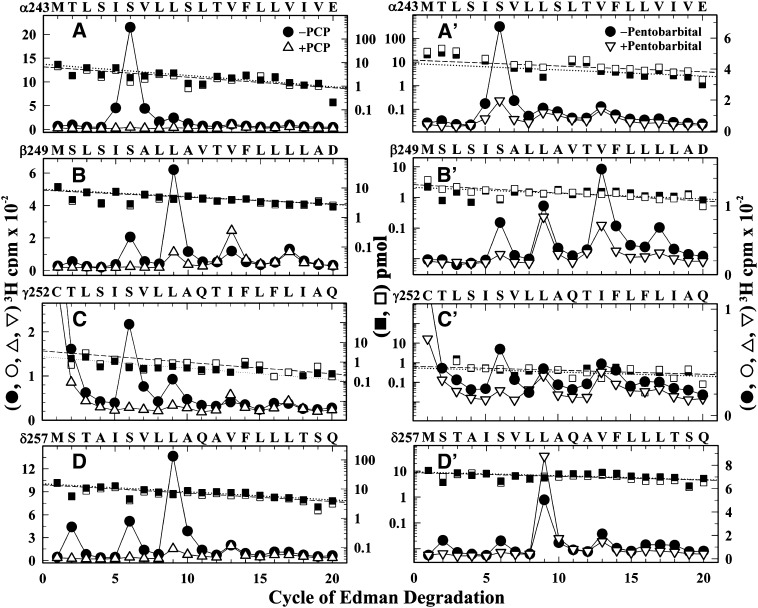

To further characterize [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling within the ion channel in the desensitized state, nAChR-rich membranes were photolabeled with [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the presence of Carb ± 100 µM PCP or ± 2 mM pentobarbital, and photoincorporation was determined in each of the M2 helices (Fig. 6, A–D, αβγδ ±PCP; and A′–D′, αβγδ ± pentobarbital). PCP inhibited photolabeling of δM2-2 and α/β/γ/δM2-6 by >95% and photolabeling of M2-9 in each subunit by >80%. PCP enhanced photolabeling of βM2-13. Similarly, pentobarbital inhibited photolabeling of δM2-2 and α/β/γ/δM2-6 by >85%. In contrast with PCP, photolabeling at position M2-9 was either reduced by approximately 15% (β, γ) or enhanced by 100% (δ) in the presence of pentobarbital, whereas photolabeling of βM2-13 and βM2-17 was reduced by approximately 70%.

Fig. 6.

PCP and pentobarbital inhibition of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling within the nAChR ion channel in the desensitized state. 3H (○, ●, ▵, ▿) and phenylthiohydantoin–amino acids (□, ▪) released during sequence analyses of fragments beginning at the N termini of αM2 (A and A′), βM2 (B and B′), γM2 (C and C′), and δM2 (D and D′) isolated from nAChRs photolabeled in the presence of Carb (●, ▪), Carb and 100 µM PCP (▵, □; A–D), or Carb and 2 mM pentobarbital (▽, ⬜; A′–D′). Fragments beginning at βMet242 and δMet257 were isolated as described in Fig. 5. Fragments beginning at αMet243 and γCys252 were isolated by rpHPLC fractionation of EndoLys-C digests of αV8-20 and γV8-24, respectively, generated by subunit in-gel digestion with V8 protease. The initial yields (I0) for the sequenced fragments (Carb/Carb + PCP, Carb/Carb + PB; in picomoles): αMet242 (A, 9/7; A′, 9/12), βMet249 (B, 9/8; B′, 2/3), γCys252 (C, 2/4; C′, 0.6/0.7) and δMet257 (D, 15/14; D′, 9/9). For the βM2, γM2, and δM2 sequences, any other fragment, if present, was at < 10% of the mass of the M2 fragments. αM2 samples were contaminated by βM2 at ∼30% the level of αM2. The efficiencies of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling (Carb/Carb + PCP, Carb/Carb + PB; in counts per minute per picomole) were as follows: for αM2: αM2-5 (17/0.3, 4.4/0.2) and αM2-6 (60/2, 17/3) (A and A′); for βM2: βM2-6 (5/0.2, 7/1), βM2-9 (22/4, 11/9), βM2-13 (3/9, 20/7), and βM2-17 (5/4, 6/1) (B and B′); for γM2: γM2-6 (43/0.7, 19/4) and γM2-9 (18/2, 13/6) (C and C′); and for δM2: δM2-2 (6/<1, 3/0.3), δM2-6 (9/0.4, 3/1), δM2-9 (30/3, 14/26), and δM2-13 (4/5, 5/3) (D and D′).

Selective Photolabeling in M3 Helices of γMet299.

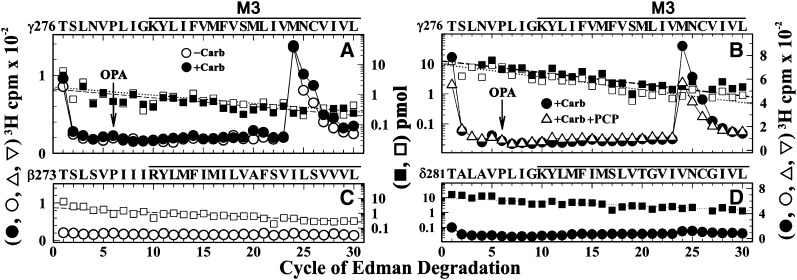

When [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation was analyzed at the level of intact subunits (Fig. 3), there was greater photolabeling in the γ subunit than in the β or δ subunit in the absence of agonist, and that photolabeling was not inhibited by tetracaine, which suggested photolabeling outside the ion channel. Since photoreactive analogs of etomidate were known to bind to a site in the nAChR TMD at the γ–α subunit interface and photolabel amino acids in γM3 (γMet295 and/or γMet299; Nirthanan et al., 2008; Hamouda et al., 2011), we characterized [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling within the β, γ, and δ M3 helices (Fig. 7). This was accomplished by sequencing fragments beginning at βThr273/γThr276/δThr281 that were generated by V8 protease cleavage and by chemical isolation of the fragments during sequencing by treatment of the sequencing filter with OPA before the sixth cycle of Edman degradation to block further sequencing of fragments not containing a proline at that cycle.

Fig. 7.

[3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabels γMet299 in γM3. 3H (○, ●, ▿) and phenylthiohydantoin–amino acids (□, ▪) released during sequence analyses of M3-containing fragments beginning at γThr276 (A and B), βThr273 (C), and δThr281 (D). The γ and δ subunits isolated from nAChRs photolabeled in the absence (○, □) or the presence of Carb (●, ▪) or Carb and 100 µM PCP (▵, □) were digested with V8 protease, and the digests were fractionated by rpHPLC. For both digests, >95% of 3H was eluted as a single hydrophobic rpHPLC peak that was pooled for sequencing, with OPA treatment at cycle 6 of Edman degradation (indicated by arrows). OPA treatment prevents further sequencing of peptides not containing a proline at cycle 6 and therefore chemically isolates fragments beginning at γThr276, βThr273, and δThr281 that each contain a proline at cycle 6. (A and B) After treatment with OPA, sequencing continued for the fragment beginning at γThr276 (A, ±Carb, approximately 2 pmol both conditions; B, +Carb/+Carb+PCP, 13/10 pmol) and for contaminating peptides beginning at βThr273 and δThr281 that were present at ≤25% the level of γThr276. The peak of 3H release in cycle 24 indicates [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling of γMet299 (A, ±Carb, 58/65 cpm/pmol; B, +Carb/+Carb+PCP, 99/105 PM/pmol). (C) Sequence analysis of the fragment beginning βThr273 (−Carb, 2 pmol), the only sequence detected after OPA treatment. Any 3H photolabeling within βM3 was at <2 cpm/pmol. Since the gel band containing the nAChR β subunit often contains a γ subunit proteolytic fragment, the fragment beginning at βThr273 was isolated by first isolating the fragment beginning at βMet249, as described in the legend of Fig. 5. rpHPLC was then used to fractionate the V8 protease digest of the βMet249 fragment. (D) Sequence analysis of the fragment beginning δThr281 (+Carb, 10 pmol). Any 3H photolabeling in δM3, if it occurred, was at <4 cpm/pmol.

When the fragment beginning at γThr276 was sequenced (Fig. 7, A and B), there was a single major peak of 3H release in cycle 24, indicating photolabeling of γMet299 at similar efficiency in the resting and desensitized states (Fig. 7A, 58/65 cpm/pmol, respectively) with PCP having no effect on photolabeling in the desensitized state (Fig. 7B, ± PCP 99/105 cpm/mol). By contrast, no peaks of 3H release were detected during sequencing through βM3 (Fig. 7C) or δM3 (Fig. 7D), which indicated that any photolabeling would be at <2 or <4 cpm/pmol.

Barbiturates Inhibit Photolabeling of γMet299.

Amino acid sequence analyses of photolabeling in γM3 (Fig. 7) established state-independent [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation at γMet299 and also established that there was little, if any, photolabeling of the residues in γM3 that are exposed to membrane lipid and photolabeled nonspecifically by [125I]TID ([125I]3-(trifluoromethyl)-3-(m-iodophenyl)diazirine; γPhe292, γLeu296, γAsn300; Blanton and Cohen, 1994). On the other hand, there was substantial [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation within the αV8-10 fragment (Fig. 4) that we localized to photolabeling of αCys412, the amino acid at the lipid-exposed face of αM4 helix that is most efficiently photolabeled by [125I]TID (Blanton and Cohen, 1994) (see below).

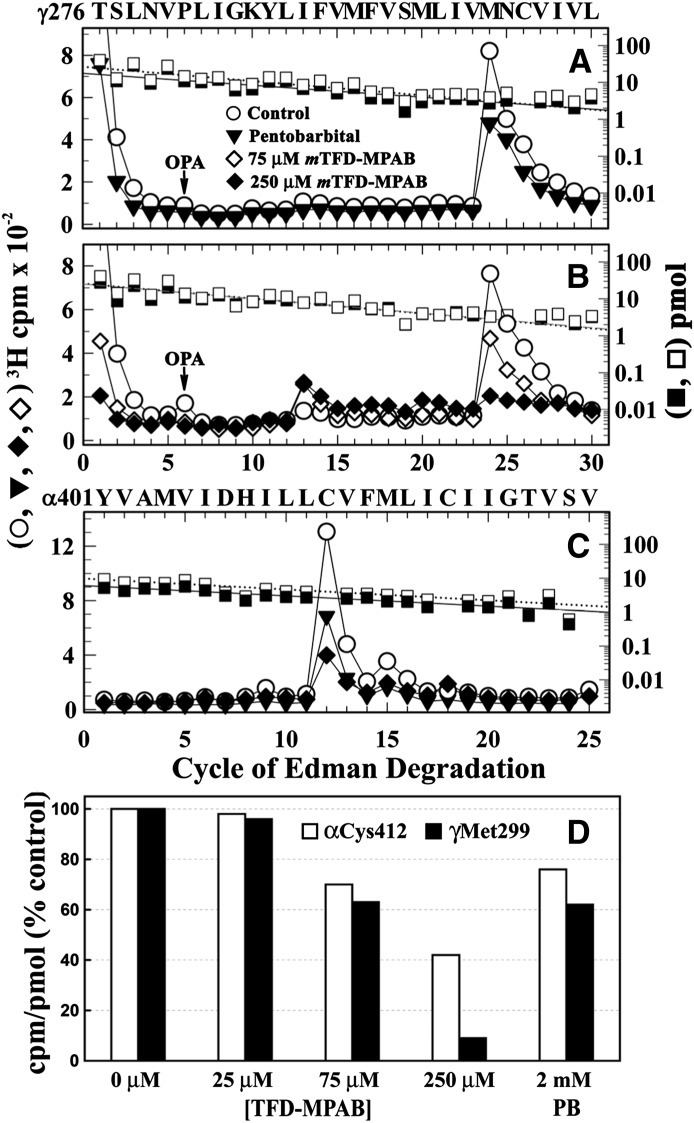

To evaluate the pharmacological specificity of γMet299 photolabeling compared with photolabeling of residues exposed at the lipid–protein interface, we examined the effects of nonradioactive mTFD-MPAB and pentobarbital on the efficiency of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling at γMet299 and αCys412 in the absence of agonist. Whereas pentobarbital at 2 mM only partially (approximately 40%) reduced photolabeling at γMet299 (Fig. 8A), mTFD-MPAB exhibited a nearly complete (>90% at 250 μM) and concentration-dependent inhibition of γMet299 photolabeling (IC50 = approximately 100 μM; Fig. 8, B and D).

Fig. 8.

Effects of mTFD-MPAB and pentobarbital on photolabeling of γMet299 and αCys412. (A–C) 3H (○, ▾, ⋄, ♦) and phenylthiohydantoin–amino acids (□, ▪) released during sequence analyses of γM3 (A and B) and αM4 (C). (A and B) Fragments beginning at γThr276 were isolated, as described in the legend of Fig. 6, from nAChRs photolabeled with [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the absence (○, □) or presence of 75 μM (⋄) or 250 μM mTFD-MPAB (♦, ▪), or 2 mM pentobarbital (▾, ▪). The masses (I0) for the γThr276 fragments were as follows: 27 pmol for the control and 18 pmol for pentobarbital (A), and approximately 25 pmol for each condition (B). (C) Fragments beginning at αTyr401 were isolated by rpHPLC from trypsin digests of α subunits from the preparative labelings of (A) and (B). The major peak of 3H release in cycle 12 indicates [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling of αCys412. (D) Efficiencies of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling of γMet299 and αCys412, calculated as the percentage of the photolabeling efficiencies in the control condition. The data are combined from three photolabeling experiments, with γMet299 photolabeled in the three controls at 45 ± 2 cpm/pmol and αCys412 at 62 ± 3 cpm/pmol (mean ± S.D.).

When the α subunit fragment beginning at αTyr401 that contains the αM4 helix was isolated from the same photolabeling experiments and sequenced, we found that photolabeling at αCys412 was partially inhibited by pentobarbital or mTFD-MPAB (Fig. 8C). As shown in Fig. 8D, at each concentration of mTFD-MPAB, photolabeling of γMet299 was reduced more than the photolabeling of αCys412, with mTFD-MPAB at 250 µM reducing αCys412 photolabeling by only 55%, in contrast with the >90% reduction of γMet299 photolabeling. The decreasing ratio of γMet299/αCys412 photolabeling with increasing concentrations of mTFD-MPAB indicates that the inhibition at each site must result from different mechanisms and/or binding affinity.

Photolabeling in αM1.

The selective [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling of γMet299 within the β/γ/δM3 helices was similar to that seen for two photoreactive etomidate analogs (Nirthanan et al., 2008; Hamouda et al., 2011). However, our sequencing results provided no evidence that [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeled αM2-10 (Fig. 6A), the other position at the γ–α interface photolabeled by the photoetomidates. To extend the identification of nAChR amino acids contributing to the mTFD-MPAB binding site in proximity to γMet299, we characterized [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation within αM1, which also contributes amino acids to the γ–α interface. The α subunit fragment beginning at αIle210 at the N terminus of αM1 was isolated for sequence analysis by rpHPLC from trypsin digests of α-subunits from nAChR photolabeled in the desensitized state (+Carb) in the absence and presence of pentobarbital (Fig. 9). The peak of 3H release at cycle 22 of Edman degradation indicated photolabeling of αLeu231 at an efficiency that was approximately 30% of the level of photolabeling of αM2-6 or δM2-9 in the ion channel and approximately 5% of the level of photolabeling of γMet299 from the same experiment. Similar to γMet299, αIle231 was photolabeled at similar efficiency in the absence and presence of agonist (data not shown).

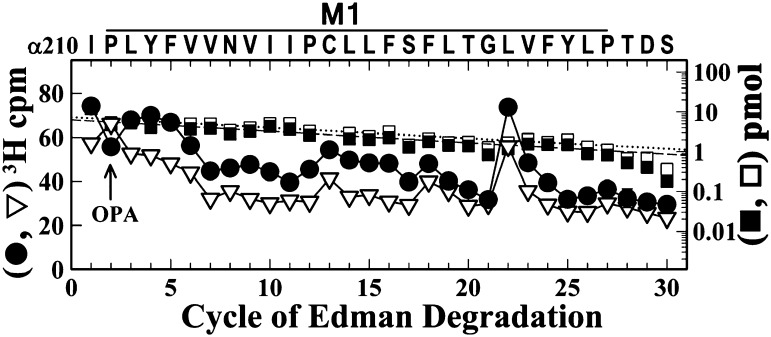

Fig. 9.

[3H]mTFD-MPAB photolabels αIle231 within the αM1 helix. 3H (●, ▿) and phenylthiohydantoin–amino acids (□, ▪) released during sequencing through fragments beginning at αIle210 before αM1 that were isolated by rpHPLC from trypsin digests (2 days) of α subunits isolated from nAChRs photolabeled [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the presence of 1 mM Carb (●, ▪) ± 2 mM pentobarbital (▿, □). During rpHPLC fractionation of α subunit trypsin digests, peptides beginning at αTyr401 and αMet253 containing αM4 and αM2, respectively, coelute as a broad peak of 3H at approximately 85% organic, whereas the fragment beginning at αIle210 eluted at approximately 65% organic (Blanton and Cohen, 1994). During sequencing, the filter was treated with OPA before cycle 2 of Edman degradation, and after that treatment the only sequence remaining began at αIle210 (7 pmol, both conditions). The peak of 3H release at cycle 22 indicates photolabeling of αLeu231 (4 cpm/pmol, both conditions).

Photolabeling in the δ Subunit Helix Bundle.

We also wanted to determine whether [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeled amino acids within the nAChR δ subunit helix bundle, since other general anesthetics ([14C]halothane, [3H]TFD-etomidate, and a photoreactive propofol analog; Chiara et al., 2003; Hamouda et al., 2011; Jayakar et al., 2013) and small, photoreactive hydrophobic drugs ([125I]TID and [3H]benzophenone; Arevalo et al., 2005; Garcia et al., 2007) that act as nAChR inhibitors photolabel in an agonist-dependent manner amino acids that contribute to this pocket from δM1 (δTyr228, δPhe232), δM2 (δM2-18), and/or the δM2-M3 loop (δIle288). Sequencing through δM2 (Fig. 6, D and D′) and the δM2-M3 loop (Fig. 7D) provided no evidence of [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling of amino acids contributing to the δ subunit helix bundle, and we also found that any photolabeling of δPhe232 was at <1% the level of photolabeling of δM2-9 in the ion channel (data not shown).

Discussion

In this work we used mTFD-MPAB, a photoreactive barbiturate general anesthetic (Savechenkov et al., 2012), to provide new information about barbiturate interactions with the muscle-type Torpedo nAChR and to directly identify by photoaffinity labeling two barbiturate binding sites in the nAChR TMD. For nAChR expressed in Xenopus oocytes, mTFD-MPAB (IC50 = 7 µM) was more potent than pentobarbital (IC50 = 40 µM; Yost and Dodson, 1993), the most potent Torpedo nAChR inhibitor identified in a screen of 14 barbiturates (de Armendi et al., 1993). Based on the inhibition of radiolabeled, cationic nAChR channel blockers, mTFD-MPAB binds in the nAChR ion channel in the desensitized state (IC50 = 2 µM) with approximately 70-fold higher affinity than in the resting, closed channel state. This state selectivity contrasts with that of amobarbital and pentobarbital, which have >100-fold and approximately 4-fold selectivity, respectively, for the channel in the resting state compared with the desensitized state (Cohen et al., 1986; Arias et al., 2001). However, mTFD-MPAB is N-methylated, and N-methylation of barbital and phenobarbital resulted in reduced affinity for the resting state and increased affinity for open channel and/or desensitized states (de Armendi et al., 1993).

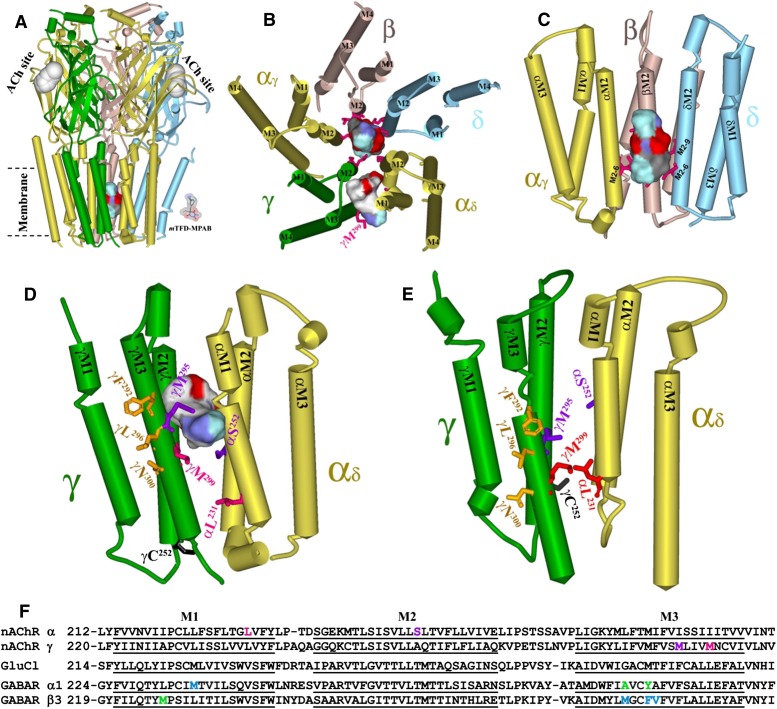

[3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photoincorporation within each nAChR subunit was enhanced in the desensitized state, and nonradioactive mTFD-MPAB and pentobarbital inhibited the agonist-enhanced subunit photolabeling with concentration dependences consistent with their inhibition of the reversible binding of the channel blocker [3H]TCP. Direct identification of the photolabeled amino acids identified a binding site for [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in the ion channel in the desensitized state and a second, lower-affinity site at the γ–α subunit interface. The photolabeled amino acids are identified in Fig. 10, A–D, in a model of the Torpedo nAChR structure based on cryoelectron microscopy (PDB ID 2BG9; Unwin, 2005) and in Fig. 10E in an homology model derived from the crystal structure of GluCl, an invertebrate glutamate-gated chloride channel (PDB ID 3RHW; Hibbs and Gouaux, 2011). Computational docking studies predict that mTFD-MPAB can bind to each of these binding sites, and the predicted binding modes are shown in Fig. 10, B–D, in Connolly surface representation.

Fig. 10.

mTFD-MPAB binding sites in the Torpedo nAChR. T. californica nAChR homology models were constructed based upon on the Torpedo marmorata nAChR structure (PDB ID 2BG9; Unwin, 2005) (A–D) and the structure of GluCl (PDB ID 3RHW; Hibbs and Gouaux, 2011) (E). Amino acid residues photolabeled by [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB are shown in stick format and colored in red. (A) Side view of the nAChR (α, gold; β, brown; γ, green; δ, cyan). (B) A view of the nAChR TMD from the base of the extracellular domain. (C) The binding site in the ion channel. (D and E) The binding site at the γ–α subunit interface, viewed from the lipid. In C–E, the M4 helices of each subunit are omitted. In A–D, the locations of R-mTFD-MPAB (molecular volume = 242 Å3) docked in the binding sites are shown as Connolly surface representations (C, black; H, white; O, red; N, blue; F, light blue) of the volumes defined by the ensemble of the energy minimized R-mTFD-MPAB docking solutions within the ion channel (160 molecules, 710 Å3; A–C) and at the γ–α subunit interface (300 molecules, 291 Å3; B and D). Also highlighted in D and E are αSer252 (αM2-10) and γMet295, residues photolabeled by [3H]TDBzl-etomidate and [3H]TFD-etomidate (Nirthanan et al., 2008; Hamouda et al., 2011), and the amino acids photolabeled by [125I]TID at the lipid interface (γPhe292, γLeu296 and γAsn300; Blanton and Cohen, 1994). γCys252 (γM2-1) is highlighted as a reference for the vertical location of M2 residues in the two models. (F) Sequence alignments used for construction of nAChR homology model based upon GluCl, with the locations highlighted in the subunit primary structures of amino acids photolabeled by [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB in nAChR αM1 and γM3 compared with the GABAAR amino acids photolabeled by [3H]R-m-TFD-MPAB in αM3 and βM1 (green; Chiara et al., 2013) and by [3H]azietomidate/[3H]TDBzl-etomidate in βM3 and αM1 (cyan; Chiara et al., 2012).

Barbiturate Binding Site in the Ion Channel.

For nAChRs in the desensitized state, the approximately 22 Å distance between the photolabeled amino acids at positions M2-2 and M2-17 exceeds the extended length of mTFD-MPAB (approximately 10 Å). However, the pharmacological specificity of photolabeling and computational docking studies indicate that [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB can bind in multiple orientations and at multiple levels in the ion channel. R-mTFD-MPAB (molecular volume = 242 Å3) docked within the Torpedo nAChR ion channel in two distinct orientations with similar energies. In the first cluster, the photoreactive diazirine was at the level of M2-13/17 with the long axis of mTFD-MPAB extending parallel to the M2 helices to below the level of M2-9. In the second cluster, mTFD-MPAB was rotated approximately 180°, with the diazirine at the level of M2-6/9 and the molecule extending to the level of M2-13. The ensemble of both clusters of mTFD-MPAB docked in the ion channel is shown in Fig. 10, B and C, in a Connolly surface representation.

Pentobarbital at 2 mM inhibited [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling in the ion channel at positions M2-2 and M2-6 by approximately 85%, consistent with its potency as an inhibitor of [3H]TCP binding in the desensitized state (IC50 = 450 µM). By contrast, photolabeling at M2-9 was either not inhibited or potentiated, which indicates that [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB can bind in the ion channel near M2-9 and M2-13 when pentobarbital binds at the level of M2-2 and M2-6. Analysis of the inhibition of mouse muscle nAChR by pentobarbital and barbital indicated that they do not compete for a single site but that the binding of one destabilized the other (Dilger et al., 1997). Our results provide the first evidence that two barbiturates can bind simultaneously and in close proximity in the ion channel.

Our photolabeling results also provide evidence that R-mTFD-MPAB and the cationic channel blocker PCP can bind simultaneously in the ion channel. PCP fully inhibited [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling at positions M2-2, M2-6, and M2-9 without inhibiting photolabeling at M2-13. In conjunction with the full inhibition of [3H]TCP binding by mTFD-MPAB, these results indicate that R-mTFD-MPAB and PCP/TCP bind in a mutually exclusive manner near the cytoplasmic end of the channel and that in the presence of PCP, [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB can bind near the level of M2-13 and M2-17. A similar result was reported for the interactions between PCP and [3H]chlorpromazine, a photoreactive, cationic channel blocker (Chiara et al., 2009). PCP fully inhibited [3H]chlorpromazine photolabeling at positions M2-6, M2-9, and M2-13, but did not inhibit photolabeling at positions M2-17 and M2-20.

Anesthetic Binding Site at the γ–α Interface.

In addition to the high-affinity barbiturate binding site within the nAChR ion channel, [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB also photolabeled γMet299, an amino acid in γM3 at the γ–α subunit interface that is photolabeled, along with αSer252 (αM2-10), by photoreactive etomidate analogs that act as positive ([3H]TDBzl-etomidate; Nirthanan et al., 2008) and negative ([3H]TFD-etomidate; Hamouda et al., 2011) modulators. Although [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB did not photolabel αM2-10, it photolabeled γMet299 in the desensitized state more efficiently than any residues in the nAChR ion channel. Whereas [3H]R-mTFD-MPAB photolabeling of γMet299 was insensitive to agonist and to PCP, photolabeling in the nAChR resting state was inhibited by nonradioactive mTFD-MPAB with an IC50 value of approximately 100 µM and pentobarbital inhibited photolabeling by 40% at the highest concentration tested (2 mM). Thus, the affinity of mTFD-MPAB for this site in the nAChR resting state is approximately 20-fold weaker than its affinity for the ion channel in the desensitized state, but is similar to its affinity for the ion channel in the resting state. R-mTFD-MPAB docked in this binding site in a single preferred orientation, with the long axis of mTFD-MPAB extending approximately perpendicular to the transmembrane helices and the diazirine positioned within 5 Å of the photolabeled γMet299 and γMet295 (Fig. 10D).

[3H]R-mTFD-MPAB also photolabeled αLeu231 in αM1 (Fig. 9), which in the nAChR structure 2BG9 is located at the γ–α interface two helical turns below and approximately 13 Å from γ Met299. However, in a nAChR homology model derived from GluCl (Fig. 10E), αLeu231 is located directly across from γMet299 and within 4 Å. mTFD-MPAB can also be docked in this homology model in the pocket at the γ–α interface in proximity to the photolabeled amino acids (not shown). The vertical shift of nAChR amino acids in the M2 and M3 helices relative to the M1 helix in the nAChR 2BG9 structure compared with the GluCl structure occurs without any change of the M2 amino acids predicted to line the lumen of the ion channel. The differences may reflect actual differences in the nAChR and GluCl structures. However, our photolabeling results, in conjunction with recent cysteine crosslinking studies designed to determine the vertical alignment of amino acids in the nAChR M2 and M3 helices (Mnatsakanyan and Jansen, 2013), provide experimental evidence favoring nAChR homology models based on the GluCl structure for the structure of the nAChR TMD.

R-mTFD-MPAB Interactions with nAChR and GABAAR.

mTFD-MPAB has similar potency as a nAChR inhibitor (IC50 = 5 µM) and GABAAR potentiator (EC50 = 2 µM; Savechenkov et al., 2012). However, the high-affinity binding sites are nonequivalent, as our results establish that R- or S-mTFD-MPAB binds in the nAChR ion channel (desensitized state), whereas the R-mTFD-MPAB binds with 20-fold higher affinity than the S-isomer to sites in the GABAAR TMD at the α+−β− and γ+−β− subunit interfaces (Chiara et al., 2013). The nAChR binding site at the γ–α interface, identified by photoaffinity labeling of γMet299, however, is analogous to the R-mTFD-MPAB GABAAR intersubunit sites. In both receptors, these sites are located at subunit interfaces that do not contain transmitter binding sites in the extracellular domain, but the nAChR photolabeled amino acids site are located in the interface two helical turns lower (toward the cytoplasm) than those photolabeled in the GABAAR (Fig. 10F).

Although mTFD-MPAB binds to nonequivalent, high-affinity sites in a nAChR and GABAAR, the TFD group is an important determinant of potency for both receptors. For nAChR in the desensitized state, mTFD-MPAB binds with 100-fold higher affinity in the ion channel than MPAB, whereas R-mTFD-MPAB binds with 20-fold higher affinity than R-MPAB to its GABAAR sites (Chiara et al., 2013). This increase in affinity contributed by the TFD substituent is close to the calculated 80-fold increase in the partition coefficient predicted for that substituent, but the strong contribution of TFD to the energetics of mTFD-MPAB binding is not seen when that substituent is introduced into other general anesthetics. p-TFD-etomidate, a photoreactive analog of etomidate incorporating the TFD group on the phenyl ring of etomidate, binds to the GABAAR etomidate site with 10-fold lower affinity than etomidate (Chiara et al., 2013) and in the nAChR ion channel with 5-fold lower affinity (Hamouda et al., 2011).

Abbreviations

- α-BgTx

α-bungarotoxin

- ACh

acetylcholine

- Carb

carbamylcholine

- EndoLys-C

Lysobacter enzymogenes endoproteinase Lys-C

- GABAAR

GABAA receptor

- MPAB

(5-allyl-1-methyl-5-phenyl)barbituric acid

- mTFD-MPAB

5-allyl-1-methyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyldiazirinylphenyl)barbituric acid

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- OPA

o-phthalaldehyde

- PCP

phencyclidine

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- rpHPLC

reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- TCP

tenocyclidine

- TFD

trifluoromethyldiazirinyl

- TID

3-(trifluoromethyl)-3-(m-iodophenyl)diazirine

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- V8 protease

Staphylococcus aureus endoproteinase Glu-C

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Hamouda, Cohen.

Conducted experiments: Hamouda, Stewart.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Savechenkov, Bruzik.

Performed data analysis: Hamouda, Stewart, Chiara, Cohen.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Hamouda, Cohen.

Footnotes

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grant P01-GM58448 (to J.B.C.)].

References

- Arevalo E, Chiara DC, Forman SA, Cohen JB, Miller KW. (2005) Gating-enhanced accessibility of hydrophobic sites within the transmembrane region of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor’s δ-subunit. A time-resolved photolabeling study. J Biol Chem 280:13631–13640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Bhumireddy P, Spitzmaul G, Trudell JR, Bouzat C. (2006) Molecular mechanisms and binding site location for the noncompetitive antagonist crystal violet on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochemistry 45:2014–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, McCardy EA, Gallagher MJ, Blanton MP. (2001) Interaction of barbiturate analogs with the Torpedo californica nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. Mol Pharmacol 60:497–506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Trudell JR, Bayer EZ, Hester B, McCardy EA, Blanton MP. (2003) Noncompetitive antagonist binding sites in the torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. Structure-activity relationship studies using adamantane derivatives. Biochemistry 42:7358–7370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton MP, Cohen JB. (1994) Identifying the lipid-protein interface of the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: secondary structure implications. Biochemistry 33:2859–2872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondarenko V, Mowrey D, Tillman T, Cui T, Liu LT, Xu Y, Tang P. (2012) NMR structures of the transmembrane domains of the α4β2 nAChR. Biochim Biophys Acta 1818:1261–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd ND, Cohen JB. (1984) Desensitization of membrane-bound Torpedo acetylcholine receptor by amine noncompetitive antagonists and aliphatic alcohols: studies of [3H]acetylcholine binding and 22Na+ ion fluxes. Biochemistry 23:4023–4033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer AW, Oman CL, Margolies MN. (1984) Use of o-phthalaldehyde to reduce background during automated Edman degradation. Anal Biochem 137:134–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Dangott LJ, Eckenhoff RG, Cohen JB. (2003) Identification of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor amino acids photolabeled by the volatile anesthetic halothane. Biochemistry 42:13457–13467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Dostalova Z, Jayakar SS, Zhou X, Miller KW, Cohen JB. (2012) Mapping general anesthetic binding site(s) in human α1β3 γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors with [³H]TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive etomidate analogue. Biochemistry 51:836–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Hamouda AK, Ziebell MR, Mejia LA, Garcia G, 3rd, Cohen JB. (2009) [(3)H]chlorpromazine photolabeling of the torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor identifies two state-dependent binding sites in the ion channel. Biochemistry 48:10066–10077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara DC, Jayakar SS, Zhou X, Zhang X, Savechenkov PY, Bruzik KS, Miller KW, Cohen JB. (2013) Specificity of intersubunit general anesthetic-binding sites in the transmembrane domain of the human α1β3γ2 γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor. J Biol Chem 288:19343–19357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JB, Correll LA, Dreyer EB, Kuisk IR, Medynski DC, Strnad NP. (1986) Interactions of local anesthetics with Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, in Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Anesthetics (Roth S, Miller KW. eds) pp 111–124, Plenum, New York [Google Scholar]

- de Armendi AJ, Tonner PH, Bugge B, Miller KW. (1993) Barbiturate action is dependent on the conformational state of the acetylcholine receptor. Anesthesiology 79:1033–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilger JP, Boguslavsky R, Barann M, Katz T, Vidal AM. (1997) Mechanisms of barbiturate inhibition of acetylcholine receptor channels. J Gen Physiol 109:401–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson BA, Braswell LM, Miller KW. (1987) Barbiturates bind to an allosteric regulatory site on nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-rich membranes. Mol Pharmacol 32:119–126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson BA, Urh RR, Miller KW. (1990) Relative potencies for barbiturate binding to the Torpedo acetylcholine receptor. Br J Pharmacol 101:710–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage PW, McKinnon D. (1985) Effects of pentobarbitone on acetylcholine-activated channels in mammalian muscle. Br J Pharmacol 85:229–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher MJ, Cohen JB. (1999) Identification of amino acids of the torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contributing to the binding site for the noncompetitive antagonist [(3)H]tetracaine. Mol Pharmacol 56:300–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G, 3rd, Chiara DC, Nirthanan S, Hamouda AK, Stewart DS, Cohen JB. (2007) [3H]Benzophenone photolabeling identifies state-dependent changes in nicotinic acetylcholine receptor structure. Biochemistry 46:10296–10307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Chiara DC, Blanton MP, Cohen JB. (2008) Probing the structure of the affinity-purified and lipid-reconstituted Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry 47:12787–12794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Stewart DS, Husain SS, Cohen JB. (2011) Multiple transmembrane binding sites for p-trifluoromethyldiazirinyl-etomidate, a photoreactive Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor allosteric inhibitor. J Biol Chem 286:20466–20477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs RE, Gouaux E. (2011) Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature 474:54–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakar SS, Dailey WP, Eckenhoff RG, Cohen JB. (2013) Identification of propofol binding sites in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with a photoreactive propofol analog. J Biol Chem 288:6178–6189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz EJ, Cortes VI, Eldefrawi ME, Eldefrawi AT. (1997) Chlorpyrifos, parathion, and their oxons bind to and desensitize a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: relevance to their toxicities. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 146:227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampfl K, Schlesinger F, Dengler R, Bufler J. (2000) Pentobarbital has curare-like effects on adult-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channel currents. Anesth Analg 90:970–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasowski MD, Harrison NL. (1999) General anaesthetic actions on ligand-gated ion channels. Cell Mol Life Sci 55:1278–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löscher W, Rogawski MA. (2012) How theories evolved concerning the mechanism of action of barbiturates. Epilepsia 53 (Suppl 8):12–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Olsen RW. (1994) GABAA receptor channels. Annu Rev Neurosci 17:569–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton RE, Cohen JB. (1991) Mapping of the acetylcholine binding site of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: [3H]nicotine as an agonist photoaffinity label. Biochemistry 30:6987–6997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton RE, Strnad NP, Cohen JB. (1999) Photoaffinity labeling the torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with [(3)H]tetracaine, a nondesensitizing noncompetitive antagonist. Mol Pharmacol 56:290–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic SJ, Harris RA. (2011) Hypnotics and sedatives, in Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Experimental Therapeutics (Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. eds) pp 457-480, McGraw-Hill, New York [Google Scholar]

- Mnatsakanyan N, Jansen M. (2013) Experimental determination of the vertical alignment between the second and third transmembrane segments of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurochem 125:843–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nirthanan S, Garcia G, 3rd, Chiara DC, Husain SS, Cohen JB. (2008) Identification of binding sites in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor for TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive positive allosteric effector. J Biol Chem 283:22051–22062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MB, Husain SS, Miller KW, Cohen JB. (2000) Identification of sites of incorporation in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor of a photoactivatible general anesthetic. J Biol Chem 275:29441–29451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revah F, Galzi JL, Giraudat J, Haumont PY, Lederer F, Changeux JP. (1990) The noncompetitive blocker [3H]chlorpromazine labels three amino acids of the acetylcholine receptor γ subunit: implications for the α-helical organization of regions MII and for the structure of the ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:4675–4679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth SH, Forman SA, Braswell LM, Miller KW. (1989) Actions of pentobarbital enantiomers on nicotinic cholinergic receptors. Mol Pharmacol 36:874–880 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. (2004) Molecular and neuronal substrates for general anaesthetics. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:709–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savechenkov PY, Zhang X, Chiara DC, Stewart DS, Ge R, Zhou X, Raines DE, Cohen JB, Forman SA, Miller KW, et al. (2012) Allyl m-trifluoromethyldiazirine mephobarbital: an unusually potent enantioselective and photoreactive barbiturate general anesthetic. J Med Chem 55:6554–6565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger H, von Jagow G. (1987) Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem 166:368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. (2005) Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol 346:967–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White BH, Cohen JB. (1988) Photolabeling of membrane-bound Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with the hydrophobic probe 3-trifluoromethyl-3-(m-[125I]iodophenyl)diazirine. Biochemistry 27:8741–8751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Robertson DH, Brooks CL, 3rd, Vieth M. (2003) Detailed analysis of grid-based molecular docking: A case study of CDOCKER-A CHARMm-based MD docking algorithm. J Comput Chem 24:1549–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost CS, Dodson BA. (1993) Inhibition of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by barbiturates and by procaine: do they act at different sites? Cell Mol Neurobiol 13:159–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller A, Arras M, Jurd R, Rudolph U. (2007) Identification of a molecular target mediating the general anesthetic actions of pentobarbital. Mol Pharmacol 71:852–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebell MR, Nirthanan S, Husain SS, Miller KW, Cohen JB. (2004) Identification of binding sites in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor for [3H]azietomidate, a photoactivatable general anesthetic. J Biol Chem 279:17640–17649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]