Abstract

Introduction

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is increasingly employed in the quantitative analysis and quality control (QC) of natural products (NPs) including botanical dietary supplements (BDSs). The establishment of qHNMR based QC protocols requires method validation.

Objective

Develop and validate a generic qHNMR method. Optimize acquisition and processing parameters, with specific attention to the requirements for the analysis of complex NP samples, including botanicals and purity assessment of NP isolates.

Methodology

In order to establish the validated qHNMR method, samples containing two highly pure reference materials were used. The influence of acquisition and processing parameters on the method validation were examined, and general aspects of method validation of qHNMR methods discussed. Subsequently, the established method was applied to the analysis of two natural products samples: a purified reference compound and a crude mixture.

Results

The accuracy and precision of qHNMR using internal or external calibration were compared, using a validated method suitable for complex samples. The impact of post-acquisition processing on method validation was examined using three software packages: TopSpin, MNova, and NUTS. The dynamic range of the developed qHNMR method was 5,000:1 with a limit of detection (LOD) of better than 10 μM. The limit of quantification (LOQ) depends on the desired level of accuracy and experiment time spent.

Conclusions

This study revealed that acquisition parameters, processing parameters, and processing software all contribute to qHNMR method validation. A validated method with high dynamic range and general workflow for qHNMR analysis of NPs is proposed.

Keywords: quantitative NMR, qNMR, qHNMR, validation, dynamic range, sensitivity, processing

INTRODUCTION

The growing popularity of botanical dietary supplements (BDSs) has resulted in a need for precise, accurate and rugged analytical methods and reference materials to cover various aspects of botanical integrity and quality control (QC). QC of BDSs includes the verification of the herbal identity, the identification and quantification of adulterants and/or contaminants, and the measurement of the amounts of the declared marker constituent(s) in raw materials as well as finished products (normation and standardization) (Betz et al., 2007; Cavaliere et al., 2010). Currently, QC employs primarily hyphenated liquid chromatography methods (LC-MS/-UV). LC techniques depend on the availability and quality of reference and calibration standards, so called reference materials, that are specific to the botanical, for both qualitative (retention times, fragmentation pattern, UV spectra) or quantitative analyses (Castro et al., 2010; Sugimoto et al., 2010a). Because the signal intensity in common LC detection techniques such as UV and MS depends on the analyte and involves a response factor, highly pure reference materials are needed for reliable quantitative results (Burton et al., 2005; van der Kooy et al., 2009). This poses a challenge when working with BDSs and natural products (NPs), as the commercial availability of reference materials is often limited to a few of the most abundant constituents (Chandra et al., 2011; van Breemen et al., 2010). In addition, because the reference materials used for standardization are mostly NPs that require isolation, they are likely to contain impurities (residual complexity) (Pauli et al., 2012a; Pauli et al., 2012b). Therefore, the assessment of purity of NP reference materials in particular, and the study of residual complexity of bioactive NPs in general [see refs (Chen et al., 2009; Gödecke et al., 2012; Jaki et al., 2008; Napolitano et al., 2012; Pauli et al., 2012a; Pauli et al., 2012b) and S0, Supporting Information], is crucial for the use of NPs as agents or calibrants in any kind of (semi-)quantitative chemical or biological assay (Schwarz 2010).

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is considered a primary analytical method, because a direct proportionality exists between the signal integral and the number of protons giving rise to it. As a result, quantitative 1H NMR (qHNMR) has certain advantages over LC methods such as LC-MS/-UV (Saito et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2010b): (i) structural and quantitative data can be obtained simultaneously; (ii) the time for sample preparation is relatively short; (iii) NMR is non-destructive; (iv) simultaneous determination of more than one analyte in a mixture is possible; and (v) due to the proportionality between signal area and the number of nuclei, no compound-specific recalibration is required. The latter point also entails two other important aspects of qHNMR: First, it does not rely on authentic, identical reference materials for quantitative analyses but can employ any highly pure, chemically stable and inert calibration standard of choice. Therefore, and second, qHNMR can be used for the quantitative analysis of unidentified metabolites as it is often the case for, e.g., impure NPs (Bekiroglu et al., 2008; Rundloef et al., 2010; Wells et al., 2008). Considering these advantages, the availability of standard operating protocols for purity assessment of NP reference materials, some of which are validated, has introduced qHNMR as a reliable and efficient methodology for BDS analysis (Diehl et al., 2007; Pauli et al., 2012a; Pauli et al., 2005). Validated qHNMR assays are available for absolute quantification, using a suitable calibration standard (Diehl et al., 2007), as well as for relative quantification by determining molar ratios of multiple compounds in a sample (Li et al., 2009; Pauli et al., 2007). Absolute quantification assays rely on the use of a calibration standard, or calibrant. In the case of internal calibration (IC), the calibrant is added to the sample prior to analysis. This is the most direct way to obtain accurate qHNMR results, because both the analyte and the calibrant are subjected to truly identical experimental conditions, which minimizes errors. For example, Malz et al. reported error values of 1% or lower when comparing the IC method with the weighed amount (Malz and Jancke 2005). In general, a qHNMR method for the analysis of botanical and other NP samples needs to fulfill certain requirements, which are not usually discussed in the available literature. The present study addresses these considerations. In order to take full advantage of the strength of NMR, i.e., quantification of multiple components in a complex mixture without the need for multiple and identical reference standards, suitable qHNMR methods need to have a low LOQ and at the same time provide a high dynamic range to cover a broad range of metabolite concentrations. Similar requirements apply to the purity analysis of NP isolates, where a common goal is to detect and quantify impurities at the 1% level and below.

Although the IC method is widely considered a the most accurate method of calibration and has been validated in previous studies, it is less suitable for the analysis of NPs as it requires re-contaminating samples that often were obtained through tedious purification procedures. An additional limitation of IC, which is avoided by external calibration (EC), is the potential overlap between the calibrant and the often already complex analyte signals. Therefore, the present study assesses a combination of EC, combined with the use of the residual solvent signal as internal calibrant (ECIC), a method which has been previously described to produce reliable results (Gödecke et al., 2012; Pierens et al., 2008). The residual solvent signal of DMSO-d6 was observed in a clear spectral region in recent extensive NMR analyses of natural product samples e.g. (Napolitano et al., 2012), and taken together with the ability of DMSO to dissolve a very wide range of compounds, the solvent was selected for the present study.

For the ECIC method, a calibration curve has to be acquired for each solvent type and batch. Methods that rely on external calibration (EC) only can be attractive alternatives. Some published EC methods depend on specific instrumentation [e.g. ERETIC (Akoka et al., 1999)], or on proprietary software packages that can generate an artificial calibration signal to be placed anywhere within the spectrum. As the software based approaches to EC use a calibrant signal of known concentration, all subsequent qHNMR spectra need to be acquired under identical conditions for accurate results (e.g. ERETIC 2 within Bruker TopSpin software). Taking the EC concept one step further, the qHNMR method described by Burton et al., makes the data acquisition of calibrant and analyte independent from each other. In fact, the authors have demonstrated that, by carefully calibrating the NMR acquisition parameters such as the pulse width, probe tuning, and matching, EC can be used even for samples acquired under different conditions and/or in different solvents (Burton et al., 2005).

Guidelines for the validation of analytical methods are available from the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC International). In the context of qHNMR, it is important to note that the AOAC single laboratory validation (SLV) guidelines were established for LC-based analytical methods (Bruce et al., 1998; ICH, 1995). Accordingly, they may or may not be directly applicable to qHNMR methods. With respect to NMR, previously published, and validated qHNMR methods have either used the molar ratio method for relative quantification, or applied the IC method by adding a calibrant directly into the sample. Two comprehensive studies (Malz and Jancke 2005; Maniara et al., 1998) discuss parameters relevant to the validation of qHNMR analyses using IC.

Previous reports on validation of IC methods in qHNMR have focused on the impact of acquisition parameters (AcquPs) (Al-Deen 2002; Espina et al., 2009; Lavertu et al., 2003; Malz and Jancke 2005). The present study utilized this information and developed a standardized set of AcquPs (Table S.2, Supporting Information), that are most suitable for NP analyses.

Because raw qHNMR data (free induction decay, FID) requires transformation into interpretable spectra (time domain data), post-acquisition processing is an integral part of any NMR analysis. In contrast to the AcquPs, the impact of post-acquisition data processing parameters (ProcPs) on the qHNMR result has not been evaluated comprehensively previously. To fill this gap, the present study places particular emphasis on the systematic examination and comparison of ProcPs such as window function (WF), zero filling (ZF), phasing (PH), and baseline correction (BC) algorithms. In addition, the study covers the application of three widely used NMR processing software packages, including Bruker’s TopSpin and two instrument independent software packages, NUTS and MNova. Finally, the influence of the preacquisition delay (DE) on the baseline quality was evaluated (Figure S.2, Supporting Information). As both the ProcPs and the software generally impact the quantitative outcome, our findings underscore that at the minimum, both the parameters and the software package/functions need to be reported along with any qHNMR results.

The overall aim of the present work is to provide guidelines for the optimization of ProcPs, and for the standardization of qHNMR analysis of NPs. For this purpose, the impact of the ProcPs was systematically examined using the Youden trial. Considerations for the optimization of both the AcquPs and the ProcPs are presented.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Samples were accurately weighed directly into NMR tubes (Norell, 5 mm × 7″, XR-55, lots# D080107CX and D030508CSX) and dissolved in 600 μL of DMSO-d6 (Cambridge Isotopes, lot# 8L-052, 99.8% D), unless stated otherwise. The concentration of DMSO-d5 was calculated using the calibration curve for y=1 as 80.0 mM (0.66%) (Table 2). Spectra were chemical shift referenced to the residual solvent signal (set to δH 2.500 ppm, DMSO-d5 as reference signal). Investigated NPs were: ginkgolide B (Indofine, lot# 0704023, 99% (CofA); 98.9% by qHNMR/100% method; using H-8, 1H, dd, δH 1.730 ppm), ginkgolide A (HWI, lot# 10629, 99% (CofA); 98.3% by qHNMR/100% method; using H-8, 1H, dd, δH 1.710 ppm), and a certified Ginkgo biloba terpene lactone mixture, which was kindly provided by the U.S. Pharmacopeia (Rockville, MD).

Table 2.

Summary of qHNMR calibration regressions on 7 mixed dilution samples collected on 3 different days (600 MHz, DMSO-d6, concentration range: 94.5 μM - 94.5 mM). The calibrants were caffeine and DMSO2 (used for external calibration, EC) and DMSO-d5 was used as internal calibrant (IC) and as internal reference (δH 2.500 ppm). The DMSO2 signal (6 Hs, δH 2.994 ppm), and two caffeine signals (1H, εH 8.000 ppm; 3H, δH 3.868 ppm) were used as calibration signals

| calibration regressions | IC conc.d | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| slope | y-intercept | R2 | [mM] | [%]e | ||||

| all data points | y = | 0.0125 | x + | 6.00E-04 | 0.9973 | 80.0 | 0.66 | |

| Day 1a | 1H Caff | y = | 0.0145 | x − | 8.80E-03 | 0.9985 | 69.6 | 0.58 |

| Me Caff | y = | 0.0125 | x + | 5.00E-07 | 0.9999 | 80.0 | 0.67 | |

| DMSO2 | y = | 0.0126 | x − | 2.30E-03 | 0.9999 | 79.5 | 0.66 | |

| Day 2b | 1H Caff | y = | 0.0144 | x − | 9.00E-03 | 0.9985 | 70.1 | 0.58 |

| Me Caff | y = | 0.0124 | x − | 1.00E-04 | 0.9999 | 80.7 | 0.67 | |

| DMSO2 | y = | 0.0125 | x − | 2.40E-03 | 0.9999 | 80.2 | 0.67 | |

| Day 3c | 1H Caff | y = | 0.0139 | x − | 5.40E-03 | 0.9995 | 72.3 | 0.60 |

| Me Caff | y = | 0.0122 | x − | 7.00E-04 | 1.0000 | 82.0 | 0.68 | |

| DMSO2 | y = | 0.0122 | x − | 2.70E-03 | 0.9997 | 82.2 | 0.68 | |

| MEAN | = | 0.0130 | −0.00349 | 77.4 | 0.64 | |||

| STDEV | = | 0.0010 | 0.00348 | 5.18 | 0.04 | |||

| RSD [%] | = | 7.34 | 99.70 | 6.69 | 6.69 | |||

seven samples, concentrations: caffeine 0.095/0.19/0.95/4.73/9.45/9.45/47.3 mM; dimethylsulfone 0.17/0.35/1.74/ 4.34/8.68/8.68/43.4 mM.

six samples, concentrations, 0.095/0.19/0.95/4.73/9.45/47.3 mM caffeine; 0.17/0.35/1.74/4.34/8.68/43.4 mM dimethylsulfone.

six samples, concentrations, 0.095/0.19/0.95/4.73/9.45/47.3 mM caffeine; 0.17/0.35/1.74/4.34/8.68/43.4 mM dimethylsulfone.

concentration of DMSO-d5 (internal calibrant) in DMSO-d6.

[g] DMSO-d5 /100 ml DMSO-d6.

NMR external calibration (EC) standards (external calibrants)

Dimethylsulfone (Sigma Aldrich, DMSO2, lot# 099K1615) and caffeine (Sigma Aldrich, lot# 00102EJ) were used as calibrants for EC, and the residual solvent signal (DMSO-d5) was used for internal calibration (IC). The external calibrants were chosen due to their availability in high purity, chemical stability, and non-hygroscopic nature (Pierens et al., 2008; Wells et al., 2008). Samples were prepared by mixing and dilution of stock solutions (ccaffeine = 27.5 mg/mL; cDMSO2 = 24.5 mg/mL). The spin-lattice relaxation times (T1) were determined by an inversion recovery experiment (“t1ir”; 12 increments from 50 ms to 60 s) for DMSO-d5 (12.658 s), DMSO2 (2.480 s), and caffeine (δH 8.000 ppm: 2.973 s; δH 3.868 ppm: 1.756 s). The calibrants were analyzed independently for their water content to confirm their certificates of analysis [DMSO2: 99.4% (CofA); 99.3% (modified 100% method), <0.09% H2O (elemental analysis, Karl-Fischer); caffeine: 99.5% (CofA); 98.7% (modified 100% method), < 0.9% H2O [elemental analysis, Karl-Fischer]). In addition, a second calibration curve was generated using chlorogenic acid (Sigma Aldrich, lot# 070M1331, 99% (CofA); 97.8% (modified 100% method) as calibrant, using the signal of H-5’ (1H, d, δH 6.680 ppm) as the purest signal. Samples of 6 concentrations were independently weighed (concentration range 3.3-40.4 mM) into NMR tubes and dissolved in 600 μL DMSO-d6 (Cambridge Isotopes, lot# 10K-221, 99.9% D). The concentration of DMSO-d5 was calculated using the calibration curve for y=1 as 65.0 mM (0.54%) (See also Table 3). The qHNMR spectra were recorded in triplicate for each concentration using ICON NMR and an NMR Case sample changer with a capacity of 24 samples.

Table 3.

Summary of the qHNMR calibration curves of individually weighed samples of chlorogenic acid, used as calibrant and with DMSO-d5 as internal calibrant (600 MHz, DMSO-d6). Data for six standard samples (3.3-40.4 mM) were collected on 3 different days. The signal of H-5’ (1H, δ6.86 ppm) was used for calibration.

| calibration regression | IC conc.b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| slope | y-intercept | [mM] | [%]c | ||||

| all data points | y = | 0.0154 | x − | 0.0012 | 0.9991 | 65.0 | 0.54 |

| Day 1a | y = | 0.0154 | x − | 0.0011 | 0.9990 | 65.0 | 0.54 |

| Day 2a | y = | 0.0154 | x + | 0.0010 | 0.9989 | 65.1 | 0.54 |

| Day 3a | y = | 0.0154 | x − | 0.0017 | 0.9992 | 65.0 | 0.54 |

| MEAN | = | 0.0154 | 0.0013 | 65.0 | 0.54 | ||

| STDEV | = | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.0250 | 0.0005 | ||

| RSD [%] | = | 0.00 | 29.90 | 0.04 | 0.09 | ||

six samples, concentrations: 3.23/3.60/9.33/15.99/17.14/40.36 mM.

concentration of DMSO-d5 (internal calibration standard) in DMSO-d6.

DMSO-d5/100 ml DMSO-d6.

NMR processing tools and standard parameters

NMR data were processed with TopSpin (versions: 1.3 and 3.0 Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany), NUTS (version 20100424, Acorn NMR Inc., CA), and MNova (version: 7.0.3-8830, Mestrelab Research S.L., Santiago de Compostela, Spain). The following ProcPs were used: Lorentzian Gaussian line resolution enhancement (line broadening factor: -0.3; Gaussian factor: 0.05), zero-filling to 256k, manual phasing (TopSpin, NUTS) and automatic phase correction (MNova), a polynomial baseline correction routine (FB/LP routine in NUTS; best polynomial coefficient, TS and MN). The digital resolution was better than 0.069 Hz/pt for 1H (Table S2, Supporting Information). The software rNMR (http://www.r-project.org/) (Lewis et al., 2009) was used for batch integration of the calibration signals in all spectra and for the export of integral values into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for further analysis.

Instrumentation

All 1D and homonuclear 2D 1H NMR experiments (gCOSY) were acquired on a Bruker (Karlsruhe, Germany) Avance 600 NMR spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm TXI cryoprobe, with the sample temperature maintained at 25.0 °C (298.0 K). For the preparation of NMR samples, a 1 mL gas-tight syringe (Pressure-Lok®, VICI® Precision Sampling, Baton Rouge, LA) was used. The accuracy/precision for 600 μL DMSO was 603.9 μL ± 1.31 (n=10), as determined by weighing, taking into account the solvent’s specific weight for volume conversion at the respective room temperature (range: 20-25 °C). In addition, all volumes of the samples prepared for this study were recorded by weight for more accurate calculation of concentrations. Drummond Pipetting Aids glass capillaries of different volumes were used to produce diluted samples for the calibration curve, including the determinations of limit of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ). Weights were measured on a Mettler Toledo balance (Columbus, OH 43240, USA, XP205, max 220 g, d = 0.01 mg, Excellence Plus series). The accuracy of the balance was verified using an Alloy-8 precision analytical weight set (VWR catalog number 02215115). Actual weights of 3 g (two individual weights of 2g + 1g) and 2 mg (tare 3 g weight, add 2 mg weight) were recorded on 3 different days by two operators. These conditions reflected the common task of accurately weighing few-mg samples in small containers (typically <3 g). The precision and accuracy were determined as 3.00±1.5*10-5 g (n=30, relative standard deviation: 5.1*10−4%) and 1.99±0.01 mg (n=30, relative standard deviation: 0.57%), respectively. This provided proof that weights down to the sub-mg range could be recorded with high precision and accuracy. These results also warranted to regard the sample concentration by weight as the accurate value. Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals and solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH, USA) or Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

Factors and Parameters in Quantitative NMR

Assuming that quantitative conditions are fulfilled, any 1H NMR data set may be used for relative quantification studies using the 100% method for purity assessment (Gödecke et al., 2012; Pauli et al., 2005), by comparing the integral ratios of the resonances (Gödecke et al., 2012; Pauli et al., 2005; 2011). For absolute value quantification, a number of additional parameters have to be carefully controlled. Probe tuning is critical for reproducibility and maximum signal intensity. Optimal shimming is important for field homogeneity and resulting lineshape, and the effects of inadequate shimming have been described in detail (Al-Deen 2002). Both AcquPs as well as ProcPs require careful selection, and their choice and impact on the qHNMR analysis are discussed in separate sections below. For an outline of the section topics and the nomenclature of AcquPs and ProcPs with respect to the different instrument manufactures see Table S1 (Supporting Information).

Influence of Acquisition (Acqu)

Acqu1 - Pulse width Calibration and Interpulse Relaxation Delay

(P1 or D1 for Bruker, see Table S1, Supporting Information) The present study used a 90° pulse angle, and the pulse was calibrated before each experiment. Previous studies have shown that, especially when using the maximum flip angle of 90°, a careful pulse calibration is crucial, and a failure to do so has a high impact on the quantitative results (Al-Deen 2002; Burton et al., 2005). In general, selecting a 90° flip angle yields the maximum signal to noise ratio (S/N) during one acquisition cycle (number of scan (NS) = 1 for Bruker, see Table S1, Supporting Information). On the downside, for multiple scan experiments with 90° flip angles, the required relaxation delay increases. Thus, when only a limited amount of instrument time is available, selecting flip angles smaller than 90° results in a smaller S/N during each acquisition cycle, but full spin relaxation is reached faster and the acquisition cycle can be repeated more often. The Ernst Angle equation [cos(θ) = e–(D1+AQ)/T1] describes the relationship between th employed flip e angle (θ), the spin-lattice relaxation time (T1), the acquisition time (AQ), and the interpulse relaxation delay (D1). For a given T1 and the desired sum of AQ + D1, it yields the flip angle (the “Ernst angle”) that will result in maximum S/N under these conditions. For the qHNMR method presented here, the Ernst angle can be calculated as 89.7o. Because , the highest S/N in a given time (on the same instrument) is generally achieved using a 90° flip angle, and it is beneficial to achieve the required S/N by using the lowest possible number of acquisition cycles because signal averaging was shown to introduce uncertainty (Al-Deen 2002). However, when relaxation times for certain nuclei are very long (≥10 sec) and available experiment time is limited, shorter flip angles may be employed. In those cases, the Ernst Angle equation is helpful in finding an optimum flip angle to maximize the S/N for a given value of the relaxation delay, D1, but the experimental conditions under which the experiment is to be run must to be verified to insure that the results will be truly quantitative.

Acqu2 - Receiver Gain Calibration

(RG for Bruker, see Table S1, Supporting Information) The intensity (and integral) of an NMR signal depends on the receiver gain setting, which follows a nonlinear function (Mo et al., 2010). It was shown by Mo et al. that any receiver can be calibrated using the receiver gain function and a calibration sample in order to enable the comparison/conversion of spectra acquired at different RG values. The present study was conducted using a uniform RG setting (RG=16; Figure S2, Supporting Information) at ~40% of the maximum S/N of the instrument. The choice of this relatively low RG setting resulted in a high dynamic range of the method, leading to a large range of linearity between S/N and sample concentrations of up to 86 mM for a 6H-signal (see Valid7 for details). This makes the resulting qHNMR method suitable for a wide range of NP analysis, including crude extracts, fractions, and isolates.

Acqu3 – Preacquisition Delay Optimization

(DE for Bruker, Table S1, Supporting Information) The preacquisition delay has an impact on the baseline of the spectrum (Figure S9, Supporting Information). The default value is not necessarily the best value and needs to be optimized for a given combination of spectrometer, probe, and sample. Optimizing the preacquisition delay leads to elimination of 1st order phasing needs (Zhu et al., 1993).

Acqu4 – Other Acquisition Parameters

A summary of AcquPs that establish quantitative conditions as part of a standardized qHNMR protocol for NP is provided in the following review articles (Pauli et al., 2012a; Pauli et al., 2005).

Influence of processing (Proc)

Proc1 – Choice of Window Functions

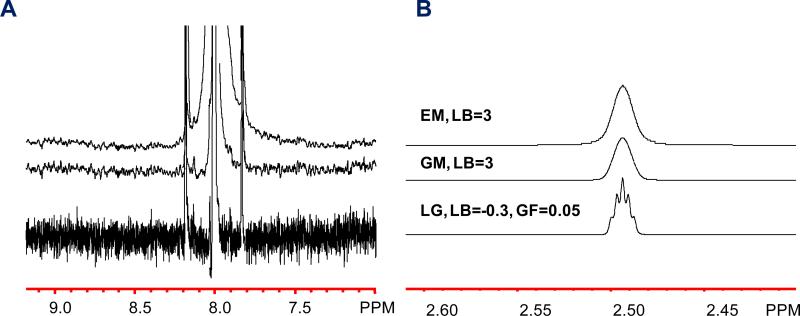

Window functions are essential to NMR post-acquisition data processing and control the balance between signal resolution, signal width, and S/N. When 1H NMR is used for compound identification, the typical goal is an optimal resolution for the observation of as much coupling information as possible. For example, the 1.7 Hz couplings of the DMSO-d5 signal can typically be well resolved when using the Lorentzian-Gaussian resolution enhancement window function (LG in NUTS), while neither Gaussian multiplication (GM in NUTS) nor exponential multiplication (EM in NUTS) yielded the signal splitting at their respectively highest S/N (Figure 1, Table S3). A comprehensive study by Malz et al. reported qHNMR results relative to the error and found that a S/N ≥ 150 yields most accurate quantification for error values ≤ 1% (Malz and Jancke 2005). In the present study, this S/N level was used as guideline during method development as the error resulting from such S/N levels is minimal and can be regarded as negligible when applied to complex NP samples. Subsequently, the impact of the three window functions and their parameters on S/N was studied systematically (Table S3, Supporting Information). In summary, the use of optimized parameters almost doubled the achievable S/N for Gaussian or exponential multiplications compared to Lorentzian-Gaussian multiplication. Comparison of the integral values that cover the range between the 13C satellites of the caffeine H-8 signal (Figure 1.A) revealed a 5% lower integral value for exponential multiplication. This unexpected observation can be explained by the insufficient width of the integral region, which likely was not wide enough to cover the entire signal under the condition of this window function. This indicates that the frequently used exponential multiplication window function leads to comparatively broad signals, which require much wider integral ranges for quantification, to capture the full signal, e.g., 5 times the signal width at half height (Malz and Jancke 2005). In addition to the impact of the different window functions on the S/N, the Gaussian multiplication, while producing less resolution enhancement than the Lorentzian-Gaussian function, leads to narrow signals and S/N values that were similar to those obtained with the exponential function. Therefore, when working with highly complex samples such as BDSs, a balance between signal overlap and S/N represents one of the major challenge for minor constituents but can be optimized by employing a GM window function. Despite these observations, and mainly because the present study was using a cryoprobe instrument where a sufficiently high dynamic range can be achieved in a reduced amount of time, the present study employed a modest Lorentzian-Gaussian multiplication (line broadening factor = -0.3 and Gaussian factor = 0.05). This approach simplifies the overall NMR workflow such that the same processed data could be used for both compound identification and quantification. In combination with the standard AcquPs, the resulting S/N was found to be sufficient for the quantification of minor impurities down to 0.2% at a sample concentration of ~35 mM (based on a 1H-signal; see section Ruggedness for discussion of results).

Figure 1.

Comparison of window functions for qHNMR analysis. The displayed spectra represent the highest S/N for the respective window function: (A) Caffeine spectra (H-8) were used in DMSO-d6 (600 MHz), applying exponential multiplication (EM, LB=3), Gaussian multiplication (GM, LB=3), and Lorentzian Gaussian multiplication (LG, LB=-0.3, GF=0.05) in NUTS processing software. (B) The DMSO-d5 residual solvent signal (J 1.7Hz) under the same processing conditions as (A). While EM and GM yielded a much improved S/N compared to LG (Table S3), the signal width at the base reached well beyond the 13C satellites when using EM, requiring large integral regions. Another aspect in the analysis of complex samples is signal resolution for compound identification. Because a sufficient dynamic range was achieved in the present case, the S/N tradeoff when using LG was acceptable and led to gain of information from small coupling constants. When a higher S/N needs to be achieved, neither GM nor EM at their respectively highest S/N (Table S3) yielded the DMSO-d5 splitting.

Proc2 – Use of Zero Filling

Zero filling (syn. zero fills; ZF) is widely used to increase the digital resolution of NMR spectra. Method validation guidelines for chromatographic analyses consider seven to ten data points across a signal as sufficient for quantification. The following compares the typically used one or two ZFs combined with Gaussian and exponential multiplication. Using the standard AcquPs at 600 MHz (Table S2, Supporting Information), a digital resolution of 0.069 Hz per point was achieved with two ZFs, while one ZF yielded a resolution of 0.14 Hz per point, and no ZF gave 0.27 Hz per point. The signal widths at half height (ω1/2) of the caffeine singlets were about 2.0 Hz (2.2 Hz, EM), about 1.4 Hz (1.6 Hz, EM) for the DMSO2 singlet, and the total signal widths were assumed to be 2ω1/2. Thus, for the DMSO2 singlet and a Gaussian multiplication, the resulting points per signal were about 40 for two ZFs (20 for one ZF, 10 for no ZF), and for an exponential multiplication yielded 46 points per signal for two ZFs (23 for one ZF, 12 for no ZF) (see section Ruggedness). In conclusion, during qHNMR method development, the digital resolution of the spectra should be evaluated and documented, and the necessary degree of ZF determined based on the spectral resolution. It should be noted that for detailed qualitative NMR analyses and observation of small coupling constants, higher resolution may be required, whereas, excessive ZF will lead to decreasing S/N values.

Proc3 – Influence of Phasing

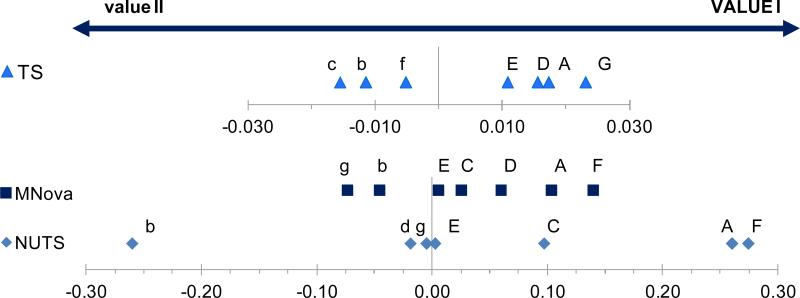

Al-Deen has previously discussed in detail (Al-Deen 2002) that improper phasing impacts integration and, therefore, needs to be optimized for accurate and reproducible qHNMR results. The author showed that the difference between the integral values of a pair of 13C satellites is a sensitive measure for the quality of phasing, especially for spectra acquired at lower S/N ratios when optical evaluation becomes difficult. While this is an effective approach, its implementation into a high-throughput workflow is hardly feasible. Representing a practical approach to the evaluation of the influence of phasing, the present study compared manual and automatic phasing routines in NUTS, TopSpin, and MNova software, using the Youden ruggedness trial (Youden and Steiner 1975). Each software package was studied individually, comparing the quantification results from manual vs. automatic phasing (Figure 2; see section Ruggedness for further discussion). In summary, phasing had a substantial impact on the quantitative results. While operator independence and reproducibility are key factors for building validated qHNMR methods, the investigated software packages are not uniform in this regard, and skillful manual phasing performed by a single operator can still outperform automatic phasing. For single and multi-laboratory validation, enhanced auto-phase algorithms will likely be most suitable.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the Youden ruggedness trial results to determine the impact of the processing parameters (factors A-G/a-g) on the qHNMR results. The distance from zero indicates the impact of each factor, while the direction indicates whether VALUE I (positive) or value II (negative) is the value of choice for implementation into the qHNMR method. The trial helped determine which processing parameters (A integration method; B integral region; C baseline correction; D phasing; E zero filling; F window function; G calibration signal) require the most careful optimization and should be kept constant to avoid variation in the qHNMR outcome. The trial results are resolved for the software packages TopSpin (TS, Bruker), NUTS (AcornNMR), and MNova (MestReLab). See Table S3 for the actual calculations.

Proc4 – Proper Baseline Correction

In addition to the choice of proper AcquPs to achieve the best baseline characteristics (see Acqu3), baseline correction in post-acquisition processing plays a central role in qHNMR analysis. Based on our observations, the integration accuracy is linked to the overall “flatness” of the baseline. The present study compared the different baseline correction algorithms within each software (NUTS: polynomial vs. linear baseline fitting; TopSpin: polynomial vs. “absd”; MNova: polynomial vs. Whittaker; Table 1), and the results were calculated by the Youden trial method (Youden and Steiner 1975) (Figure 2; see section Ruggedness for further discussion). In summary, post-acquisition baseline correction had a relatively large influence on the qHNMR results, and differed between software packages. Therefore, both the baseline correction and the selected software need to be evaluated and documented to build a validated qHNMR method.

Table 1.

Eight ProcP were evaluated in a Youden ruggedness trial. VALUE I and value II represent the two extremes in which the respective processing step (factor) can be performed, thus allowing to determine the impact of the corresponding factor on the qHNMR results

| Factor | VALUE I | value II | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| integration method | A | internal calibrant (DMSO2) | a | mod 100% Methoda |

| integral region | B | 5ω1/2b | b | 1.5ω1/2b |

| baseline correction | C | polynomial | c | other algorithmc |

| phasing | D | manual phase correction | d | Autophased |

| zero filled to | E | 256k | e | 128k |

| window function | F | (Lorentzian-)*Gaussian multiplicatione | f | Exponential multiplicationf |

| calibration signal | G | H-8 (1H, δH 8.000 ppm) | g | Me-group (3H, δH 3.868 ppm) |

modified 100% method: parameters were as follows: integration range: −5–15ppm, excluding the HDO and DMSO-d5 signals, not accounting for 13C signals.

width-at-half-height of the calibration signal.

NUTS: “BF” command; Mnova: Whittaker smoothing; Topspin: “absd” command.

NUTS: “QP” command; Mnova: “autophase”; Topspin: “apk0” then “apkl”.

NUTS: “GM” command (LB=3.0); Mnova: “Gaussian” (LB=3.0)

Topspin: “GM” (LB=−0.3, GB=0.05).

LB=3.0 was used in all software packages.

Validation of a 1D qHNMR method

The range of linearity, the selectivity, as well as the lower limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were determined, along with the accuracy and the precision of the method. Its ruggedness was evaluated and discussed based on the Youden ruggedness trial results (Youden and Steiner 1975). The samples used for the study were mixtures of reference materials, caffeine and DMSO2, which are commonly used as qHNMR calibrants, in DMSO-d6. Series with different concentrations were produced by diluting a stock solution. Both reference compounds are available in high purity, and their label purity was confirmed by independent analyses (see Experimental Section). The chosen sample makeup protocol allowed the comparison of qHNMR results using the IC method with those of the ECIC method, which represents a more suitable approach for the qHNMR analysis of NPs.

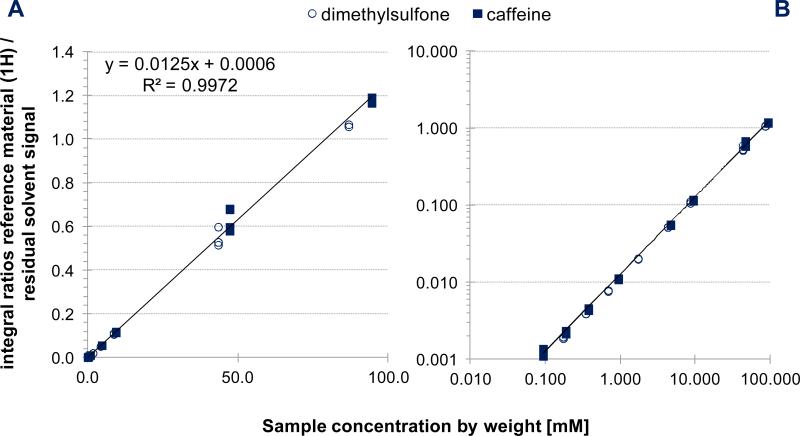

Initially, ten samples containing the two calibrants and covering the concentration range of 9.5 μM to 94.5 mM (Table S4 and Figure S13, Supporting Information) were prepared, and the qHNMR data acquired. A calibration curve (CC; Figure 5) was generated based on six of the samples (dilutions/samples 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, and 9; Figure S13). The data were acquired on three different days. Three signals per sample were integrated: the two most downfield signals of caffeine (H-8, δH 8.000 ppm [1H] and NME, δH 3.868 ppm [3H]) and the DMSO2 signal (δH 2.994 ppm [6H]). Because this assay used 1H signals that represented different numbers of protons (1H, 3H, and 6H), the data could also be used to determine the range of linearity and the LOD/LOQ. Because the integral region for each signal is another factor that greatly influences the qHNMR outcome, the integration was performed using rNMR software (see Experimental Section). This R-based freely available software allows the import of processed spectra and the batch referencing and integration, applying the same integral regions to all. The accuracy and precision of the IC and ECIC methods were also evaluated as follows.

Figure 5.

The qHNMR calibration curve using caffeine, DMSO2 (ECs) and DMSO-d5 signal (IC, δH 2.500 ppm) as calibrants for ECIC. While the plots were resolved for caffeine and DMSO2, the regression data is based on all 57 data points (for details refer to Tables 2 and Figure S12, Supporting Information). Data were acquired on 3 different days, and the selected calibration signals were one DMSO2 (6 H, δH 2.994 ppm) and two caffeine signals (1H, δH 8.000 ppm; 3H, δH 3.868 ppm). (A) linear plot, and (B) logarithmic plot of the same data.

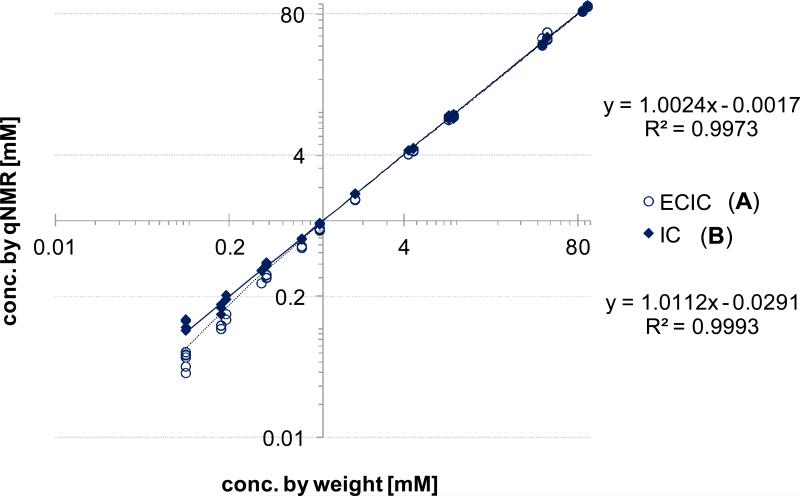

Valid1 - Accuracy and Precision

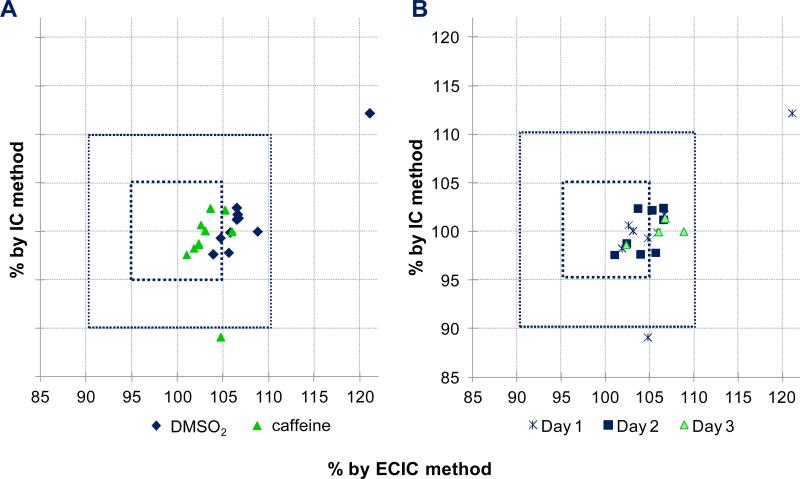

The accuracy of a quantitative method describes how close the results are to the true value. When measuring sample concentrations, the weight is often used as representative of the true value. To evaluate accuracy and precision of the two studied qHNMR calibration methods, IC and ECIC, the respective qHNMR results were plotted against the sample concentrations by weight (Figure 3). Based on the regression curves, drawn across the full concentration range, both methods are in good overall congruence with the weighed sample concentrations. The slope of the ECIC-weight correlation plot was close to unity (1.000) and exhibited a smaller value for the y-intercept, suggesting a higher accuracy compared to the IC method. On the other hand, the ECIC data points for the lower sample concentrations deviated visibly from linear behavior. Supporting this observation, precision was determined based on the respective residuals (R2 values) for ECIC (R2=0.9973) and IC (R2=0.9993). These results indicate that the IC method was somewhat more precise. The same observation was made by comparing the quantitative results of two calibrant mixtures located in the middle of the concentration range (DMSO2–caffeine 1.51 mM:0.80 mM and 1.50 mM:0.79 mM; Figure 4). The qHNMR data were collected on three different days by two individual operators. While the IC results were in close agreement with the concentrations by weight, the ECIC results were generally found to be ~5% higher (Figure 4.A), revealing a lower accuracy of the ECIC method in this setup. The precision of both methods, however, was equally good and found to be within a 5% error margin (Figure 4.A). Evaluation for day of acquisition (Figure 4.B) and operator effects (data not shown) revealed no systematic influence on the qHNMR results.

Figure 3.

Comparison of sample concentrations by weight with those determined by two qHNMR methods. (A) external calibration (EC) using the residual solvent signal as internal calibrant (ECIC), and (B) the internal calibration (IC, dimethylsulfone and caffeine as calibrants). The concentrations by weight are regarded as true values, while the concentrations by qHNMR for both methods are plotted as regression curves over the concentration range. Deviations from y = x indicate the error of the respective method.

Figure 4.

Comparison of qHNMR results obtained with the IC vs. ECIC methods, expressed as % of the respective analyte concentrations determined by weight. The caffeine and DMSO2 concentrations [mM] by weight were set to 100%. The inner and outer squares represent the 5% and 10% error margins of accuracy. Data resolved by calibrant (A) and experiment day (B). The samples were 2 mixtures of DMSO2 and caffeine 1.51mM:0.80mM and 1.50mM:0.79mM; see also Table S7 (Supporting Information), collected by 2 operators on 3 different days (Day 1: 1 sample each; Day 2: 2 samples each; Day 3: 2 samples each = 2+4+4=10 datasets).

Valid2 – Evaluation of the Calibration Curve (CC)

For this purpose, the regression equation for all data points (Figure 5), as well as individual regression equations broken down by the day of acquisition and the individual proton signals (Table 2) were compared. The residuals (R2) were interpreted as suitable measures for the precision of the method, with R2=1 indicating most precise results, while the y-axis intercept (b) was considered a measure of accuracy, with b=0 representing the ideal case. The initial data set was obtained using mixtures of the two calibrants, caffeine and DMSO2, which were produced by diluting a stock solution of both compounds. A second set of samples was obtained by individually weighing another calibrant, chlorogenic acid, directly into the NMR tubes (Table 3). The R2 and b values of this second set of regression equations confirmed the initial results and interpretations. When comparing the data of the dilution series with those of the individually weighed samples, the precision for both methods appeared equally high (R2 values) while the accuracy for the individually weighed samples was higher (lower b values). These observations indicate, that individually weighed calibration samples improve accuracy, because the random weighing error is cancelled as the number of samples used to establish the CC increases. On the other hand, the concentration range which can be covered when relying on individually weighed samples is limited. Therefore, the present outcome suggests that, for most accurate CC-based results and coverage of a wide concentration range, a combination of both, individually weighed and diluted samples, is most beneficial. Validation guidelines for LC-based methods suggest the use of seven concentrations and triplicate data collection. The present study suggests that the makeup of three individually weighed samples at different concentrations and the inclusion of dilutions of these samples would give the most accurate results. The current data also suggest that the largest deviations do not occur on a day-to-day basis, but among the different signals within one sample. This implies that the generation of a valid qHNMR CC may be feasible with only one-time acquisition when more than one signal per spectrum and/or analyte is considered. While this approach requires further research, the present study indicates that the availability of multiple quantitative signals per analyte and/or spectrum in qHNMR can potentially substitute the need to perform at least triplicate analyses, which is common practice in LC method validation.

Valid3 - Repeatability

The repeatability describes a method's ability to yield the same quantitative results on different days or by different operators. For the present study, qHNMR data were acquired on three different days and by two operators using identical AcquPs (Figure 4.B; Table S2, Supporting Information). According to Figure 4.B, the day of data acquisition had no influence on the accuracy/precision; similarly, the operator did also not influence the outcome (data not shown). Figure 4 revealed the presence of an outlier on day 1. Because none of the other samples on day 1 or the same sample on days 2 and 3 showed any further anomalies, this data point was regarded as a true outlier and product of serendipity. We think that this kind of plot might be useful for automated qHNMR workflows to evaluate large numbers of spectra for outliers that should be excluded from further analyses.

Integral Range

Setting the integral regions in a repeatable and reproducible way is another crucial aspect of qHNMR validation. In a previous publication, Malz et al. have used integral regions of five times the signal width at half height (ω1/2) and shown high accuracy of the qHNMR results using the IC method (Malz and Jancke 2005). However, qHNMR spectra of NPs including fractions and extracts are usually crowded and integral ranges need to be set as small as possible, while maintaining reproducibility through sufficient signal coverage. In order to evaluate the impact of the integral range on the qHNMR results, integral ranges of 5 * ω1/2 and 1.5 * ω1/2 were compared using the Youden ruggedness trials (see section Valid8B for details). It is important to point out that Malz et al. (Malz and Jancke 2005) had employed exponential multiplication as window function, which resulted in much broader signals compared to the Lorentzian-Gaussian multiplication used in the present study (see Proc1, Figure 1.A). In conclusion, the combination of consistently smaller integration ranges and (Lorentzian-) Gaussian multiplication yielded the best balance of lineshape and accuracy for crowded (NP) samples.

Valid4 – Selectivity and Specificity

For the present study, two calibration standards with relatively simple 1H NMR spectra were used. Hence, signal identification was apparent and signal overlap could be excluded. However, during our work with plant extracts and standard mixtures of herbal constituents, we have observed that signal purity/overlap can be determined by examining 1H,1H-COSY spectra for potential cross peak overlap of the calibrant signal to ensure selectivity of integration. While any 2D experiment could be used for this purpose, it is our experience that magnitude-mode COSY experiments are best suited due to their high sensitivity, which enables their routine acquisition as time requirements are in the same practical range as for 1D qHNMR spectra. For example, in a previous study, the 1H,1H-COSY experiment was used to select the least overlapped 1H signal of Z-ligustilide, the major alkylphthalide contained in a primary bioactive fraction of an Angelica sinensis [Oliv.] Diels extract (Gödecke et al., 2012). Signal overlap in that study was assessed by selecting the respective 1D slice from the 2D dataset that contained the highest impurity signals and by integrating both, main signal and impurity, within the selected 1D slice. Signal overlap in this previous study was assessed by selecting those 1D rows from the 2D dataset which contained the highest impurity signals and subsequently comparing the integral of both, the main signal and the impurity. While this process allows a visual assessment of signal overlap and peak purity, it remains semi-quantitative for various reasons, including deviations from quantitative conditions inherent to the COSY sequence as well as differences resulting from the integration of slices versus volume integration. However, COSY 2D plots can generally serve for the visual assessment of signal overlap and peak purity. As has been shown, the 2D experiment facilitated the identification of impurities, such as six additional alkylphthalides based on their distinctive cross peaks between protons H-8/9 (Gödecke et al., 2012). The distinctiveness of cross peaks adds to the confidence of compound identification and, thus, verifies the specificity of the qHNMR method. Another recently published example used 1H,1H-COSY for the identification of five ginkgolides in a mixture of Ginkgo biloba terpene trilactones (TTL) (Napolitano et al., 2012). Subsequently, the cross peaks were used to exclude signal overlap for the qHNMR analysis of each ginkgolide in the TTL mixture. The qHNMR results were found to be in good agreement with the LC-based certificates of analysis (Napolitano et al., 2012). In summary, 2D-COSY is a valuable, adjunctive tool for qHNMR mixture analysis, which can be used to establish the least overlapped signal of each analyte, and simultaneously verify the analyte's identity based on the cross-peak pattern. Therefore, 2D-COSY is suitable for selectivity and specificity assurance in qHNMR analysis.

Valid5 - Linearity

Determining the linear range of a quantitative method is especially crucial for methods with non-linear detector response. By default, qHNMR signal integrals are fully proportional to the number of underlying protons, thus, the response is per se linear. Nevertheless, the dynamic range of qHNMR is an important parameter. While its lower limit of linearity depends mainly on the S/N, or the ability to distinguish signal from noise, the upper limit is related to receiver saturation effects, which can result from very high signal intensities. This effect was observed for the highest concentration of the 6H signal of DMSO2 (Figure 7). Based on this observation and considering the literature, it can be concluded that the S/N is also a suitable measure for receiver overload when defining the upper limit of linearity for a qHNMR method. As indicated in section Acqu2, setting the RG value to 40% of the maximum achievable S/N using the receiver gain function (Figure S8, Supporting Information) generally yields optimized conditions for NP analysis because it balances gain for low-level constituents with accommodation of high sample concentrations.

Figure 7.

The linear correlation between the signal to noise ratio (S/N) and the sample concentration, using the mixed calibration curve samples (seven concentrations, data collected on three different days). The S/N values represent the averages of three experiments on different days, broken down by signals: DMSO2 (6Hs), the most downfield NMR signal in caffeine (3Hs), and H-8 in caffeine (1H) were used. The linear range with respect to the S/R was determined to be between ~40 and 110,000. The upper limit of linearity (*) depends on receiver gain saturation, while the lower limit (†) is due to the increasing ambiguity of signals that approach the noise level.

Valid6 - Dynamic Range

The term dynamic range refers to the concentration range over which the results are linear. The linear range was determined based on the plot of S/N vs. sample concentration (Figure 7). The lower limit of linearity was determined to be 0.09 mM for a 1H signal, and the upper limit was observed at 86 mM for a 6H signal, equivalent to 516 mM for 1H. Extrapolating the trend-lines in Figure 7 revealed the upper linearity limit to be around 500 mM for a 1H signal. Therefore, the dynamic range of the qHNMR method is better than 5,000:1.

Valid7 - Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

LOD and LOQ are validation parameters that are related to the reproducibility of the spectral background (noise) and the instrument sensitivity. It is general practice in LC data analysis to set LOD and LOQ requirements to 3 times and 5 times the S/N, respectively, and to determine the noise level by comparison with blank samples. In order to evaluate the applicability of these LC-guidelines to qHNMR, which represents a method that uses signal averaging, the equation XL = XB + kσB was used to determine LOD and LOQ (Holzgrabe et al., 2008; Thomsen et al., 2003), where XL is the smallest measure (LOD or LOQ); XB is the mean of blank measurements; k the numerical factor determining the confidence level and σB is interpreted as the standard deviation of the blank measurements. IUPAC suggests a 90% confidence level for a k-value of 3 for quantitative analyses (1995). This translates into a relative standard deviation (RSD) of 10% at the level of the LOQ, and a 33% RSD at the level of the LOD. A ratio of LOQ= 3.3LOD was used for the present study.

In general, it is perceivable to use either the integral or the S/N of a signal as measurement unit for X. Because integral values are most commonly used for qHNMR analysis, they were also used for this calculation. Because S/N calculations are a component of any NMR processing software package and proper qHNMR spectra contain expansive regions of noise, the authors feel that it is not necessary to run separate sample blanks. Instead, a signal-free region of the spectrum, similar in size to the integral regions, can serve to determine the mean integral value of the noise, XB, and the RSD, σB. Using this approach, LOD and LOQ were calculated as 23±4 μM and 73±14 μM, respectively (Figure S10, Supporting Information). These values were in good agreement with the visual analysis of the dilution series of the calibration samples, when used to determine the LOD (Figure S11, Supporting Information).

Another method by Soininen et al. suggested that LOQ and LOD can be estimated based on the CC as LOQ = 10σ/S and LOD = 3.3 σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the y-intercepts of the regression lines, and S is the slope (Soininen et al., 2005). The standard deviation of the y-intercepts and the slope can be readily calculated, e.g., by using Microsoft Excel (STEYX and SLOPE, respectively), and the present results for LOQ and LOD are summarized in Figure S12 (Supporting Information). The results indicate that the concentration range used for the calculation has an influence on the LOD/LOQ values: comparable values of 19 μM (LOD) and 57 μM (LOQ) were observed only for a concentration range of 9.5-174 μM (Figure S12, Supporting Information). However, use of the full concentration range (9.5 μM-86 mM) resulted in an LOD of 5.0 mM and LOQ of 15.3 mM. By comparison, when performing the same calculation for the CC that was based on the individually weighed samples of chlorogenic acid (3.3-40.4 mM), the resulting LOD was 1.35 mM and the LOQ 4.1 mM. Because of the nature of the statistical analysis using standard deviations, these LOD/LOQ values depend on the sample concentration, where more concentrated samples have a higher impact on the error estimation and standard deviation. It was noted that these results did not reflect the visual determination of the LOD (Figure S11, Supporting Information). Therefore, when working in the maximum dynamic range using the CC for the calculation of the LOD and LOQ does not lead to useful values, as was determined by the discrepancy of the calculated values and the LOD determined by visual inspection of the dilution series.

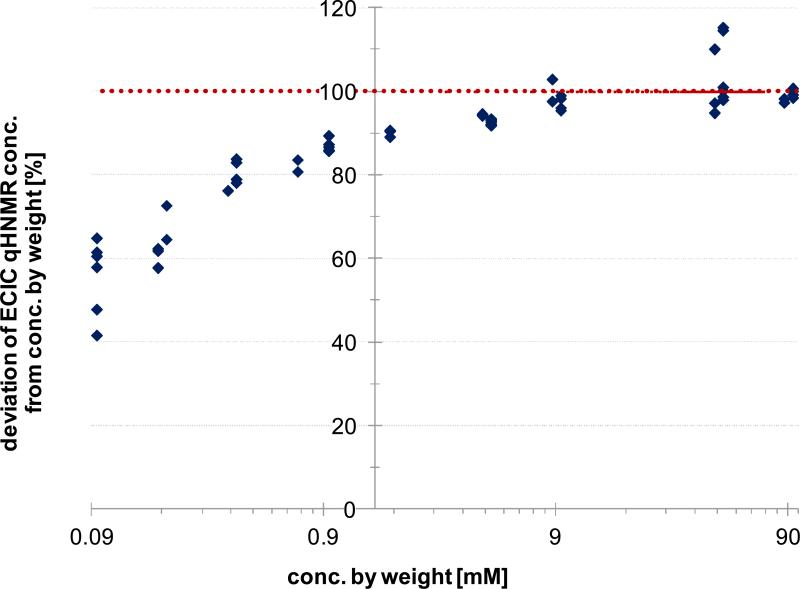

When determining LOD/LOQ values according to LC-based SLV guidelines, the LOD is always deduced first, and the LOQ is assumed to be 3-5 times the LOD. This approach entails a certainty assessment based on the Gaussian standard distribution, and the factor of 3 implies that the LOQ has a confidence level of 99%. When assessing the error values of the present ECIC qHNMR method, results fell within a 10% error limit for concentrations ≥ 0.9 mM, while the method underestimated the lowest concentrations by up to 400% (Figure 6). Accordingly, based on visual assessment of Figure 6, the LOQ of the present qHNMR method would be 0.9 mM at a confidence level of 90-95%. Projected on a Gaussian distribution curve, a confidence level of 95% is represented by a factor of 2, and the associated LOD would be 0.45 mM. This value for the LOD is in contrast to the LOD derived from visual assessment (28.2 μM; Figure S11, Supporting Information). In summary, the relation of LOQ=3-5*LOD, which entails a 95-99% confidence level of the quantitative results, did not correspond with the findings of the present study. Based on visual observations or using the general equation XL = XB + kσB revealed an LOD of 23 μM or 28 μM, respectively, but the LOQ that yielded results at a 90-95% confidence level was 0.9 mM. It can be concluded that LC-based guidelines may not be directly applicable to qHNMR analysis. The correlation of LOQ=30*LOD at a 95% confidence level may indicate that the LOD in NMR is 10 times lower compared to LC methods.

Figure 6.

Calibration curve (CC) error plot. The error in the accuracy of sample concentrations as determined by the ECIC qHNMR method is expressed as percent of the weighed sample concentrations. The weighed amounts were set to 100% and regarded as the true values. The accuracy of the qHNMR determinations stay within the 90% range for concentrations ≥ 0.9 mM. For lower concentrations, accuracy decreases as the errors increase. The precision decreases as well, as can be seen from the spread of the data points at each concentration level.

Another very practical approach to expressing the LOD and LOQ of a method utilizes the lower limit of an impurity in a sample as a percentage of the main analyte's concentration. For example, the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapter on “Validation of Compendial Procedures” states that an analytical method has to be able to detect impurities at a level of 0.1% (Pharmacopeia U.S., 2011). For the present qHNMR method with an LOD of 23 μM, this means that a 0.1% impurity (calculated as 1H) requires a ~25 mM sample (7.5 mg in 600 μL in a 5 mm tube, MR=500 g/mol). Low-level impurities containing a methyl group (3Hs) would still be detectable in a ~8 mM sample (2.5 mg/5 mm tube). Conversely, impurities with 1H signals can be detected at the 0.5% level in a 5 mM sample (1.5 mg/5 mm tube), or at the 1% level in a 2.5 mM sample (0.75 mg/5 mm tube).

The following conclusions can be made regarding the determination of the LOD in a qHNMR method: the IUPAC approach and use of signal-free regions in the calibrant spectra as the blanks, yielded results that were consistent with the graphical assessment of the LOD in a dilution series. On the other hand, the IUPAC method yielded an LOQ value that fell into the non-linear region of the CC (Figure 7). Graphical analysis led to a quantification error of >10% for sample concentrations between ~90-900 μM. Therefore, the LOQ at a confidence level of 90-95% was determined to be 0.9 mM. In conjunction, the USP approach can help determine the suitability of a qHNMR method with respect to a specific analytical problem such as impurity levels.

Valid8 – Ruggedness

To determine the ruggedness (syn. robustness) of a quantitative method, the impact of each parameter on the result has to be examined systematically by modifying one parameter at a time. A method described by Youden et al. is a substitute for this otherwise laborious approach and yields the same predictive insight. It requires the analysis to be repeated only 7 times, and the impact of 8 parameters of choice can be evaluated (Youden and Steiner 1975).

One sample of a mixture of reference materials (DMSO2 1.51 mM, 93.9 μg, 52.4%; caffeine 0.80 mM, 85.2 μg, 47.6%; Table S4) was used, eight ProcPs (factors, Table 1) were defined, and the analysis was repeated 7 times using the specific combination (Table S4, Supporting Information) of the following factors: (A) integration method, (B) integral range, (C) baseline correction [Proc4], (D) phasing [Proc3], (E) zero filling [Proc2], (F) window function [Proc1], and (G) choice of calibration signal. Following the Youden trial procedure, each factor can assume one of two values, where value I is represented by the capital letter, and value II by the corresponding lower case letter (e.g., “A” and “a”). Finally, the impact of these 8 factors on the qHNMR results were calculated (Table S5, Table S6, Supporting Information) and results are shown in Figure 2.

Valid8A

The factors (A/a) represent two methods of integration where (A) is based on the IC qHNMR method (caffeine as analyte, DMSO2 as calibrant), while (a) employs the modified 100% method (Gödecke et al., 2012) to determine the caffeine (analyte) concentration as follows: the integral of the analyte signal was related to the integral of the entire spectrum (total integral from -5 to 15 ppm, excluding the HDO and DMSO-d5 signals); the percentage of the calibrant signal was converted into a concentration for caffeine, which represents 47.6% of the mixture sample. As expected, the Youden trial results (Figure 2) revealed that the method of quantification (IC with DMSO2 as internal calibrant vs. modified 100% method) has an impact on the qHNMR results and suggested that the IC method gave more consistent results than the modified 100% method.

Valid8B

The integral range factors (B/b) were set to compare the previously reported 5 * ω1/2 integral range (B) with a much smaller range of 1.5 * ω1/2 (b). The smaller integral range covered the core of the signal, and was used to generate the CC. The largest impact of the integral range was observed when using the NUTS software, suggesting that the smaller integral range is the better option for this particular software. The same tendency can be observed for the other two software packages. However, the impact of the narrower integration is smaller in TopSpin and even more so when using MNova software.

Valid8C

With respect to baseline correction, the Youden trial results indicated that the use of a polynomial (C) vs. alternative types (c; varying by software, see Table 1) of baseline correction has a variable influence on the quantitative results in each of the three software packages. In MNova, the two compared baseline correction algorithms had no influence on the quantitative outcome. The Youden trial further suggested that in TopSpin the “absd” algorithm gave better results when compared to polynomial baseline correction. Using NUTS, the polynomial algorithm is superior to linear baseline fitting (Table 1, Figure 2). The general conclusion is that the baseline correction algorithm influences the quantitative outcome. Therefore, in order to make qHNMR results fully comparable across platforms, the same baseline correction algorithm and the same software needs to be used. At the minimum, both need to be carefully documented.

Valid8D

Phasing has been shown earlier to be a crucial parameter in qHNMR (Al-Deen 2002), and the present study systematically compared manual (D) with automatic (d) phasing routines. The results indicated that in NUTS the two phasing methods were equally good and had no impact on the qHNMR result. The biggest impact was observed in TopSpin, where manual phasing was found to be substantially better than the auto phasing routine (apk [data not shown], or apk0 + apk1). While phasing had less of an impact in MNova, the manual phasing again was the better choice. These results indicate that, while manual phasing gave better results in the current trial, the auto-phasing routines were close to equally good in two out of three software packages. Because phasing has a substantial impact on the qHNMR results, it has to be both accurate/precise and repeatable. While manual phasing exhibited higher accuracy/precision, repeatability is generally higher for automated processes and eliminates the potential for operator induced variability. However, since auto phase algorithms are proprietary and different across NMR software packages, a final recommendation cannot be made and will depend on the analytical goal and the capabilities of the software used.

Valid8E

Zero Filling (ZF) has received much attention in post-acquisition NMR processing of 2D data, to prevent phenomena such as baseline rolling due to truncation (Reynolds and Enríquez 2002). For 1D processing, a certain amount of ZF is beneficial to increase the digital resolution, while excessive ZF will have a negative impact on the S/N. The current study compared the impact of the common practice of either two (e) or three (E) ZF steps on the quantitative results. With respect to the total amount of data points of the spectrum, no impact was observed on the qHNMR results using TopSpin and MNova. In NUTS, the amount of ZF appeared to have a small impact on the qHNMR result, suggesting that 3-fold ZF was slightly beneficial. This is in line with theoretical considerations regarding the minimum number of data points per calibration signal. In summary, the use of 3-fold ZF can be considered as generally suitable for qHNMR and has the added advantage of providing spectra with high digital resolution for qualitative analysis (small J couplings).

Valid8F

Window functions (WFs) are a useful tool for 1H NMR processing to achieve either high signal resolution for the visibility of small coupling constants, or to improve on S/N in situations of low sample concentrations time limitations (Figures 1 and 2). The current study compared a [Lorentzian-]Gaussian (F) with an exponential (f) WF. The results indicated that in TopSpin the difference between Gaussian and EM on the qHNMR result is negligible. On the other hand, when using MNova or NUTS, the WF had a more pronounced impact on the quantitative outcome and the Gaussian multiplication turned out to be the better choice for consistent results (Figure 2).

Valid8G

Finally, the selected integration signal was entered as a control parameter. Theoretically, the choice of one of the analyte's signals as representative signal should have no impact on the result. The two integration signals of caffeine compared in this study were H-8 (G) and the most downfield N-methyl group (NME, g). The results confirmed that the calibration signal had no impact on the qHNMR results when using NUTS. However, in MNova, the NME signal turned out to be the better choice for consistent results, while the H-8 signal took this position when using TopSpin. In addition, when using TopSpin, the choice of the calibration signal was one of the most influential parameters with regard to the qHNMR outcome. These findings suggest that both the choice of the representative integration signal and the software impact the qHNMR outcome. More detailed studies are warranted to identify the reasons underlying the variations found between the NMR software packages.

Validated qHNMR with high dynamic range applied to natural products

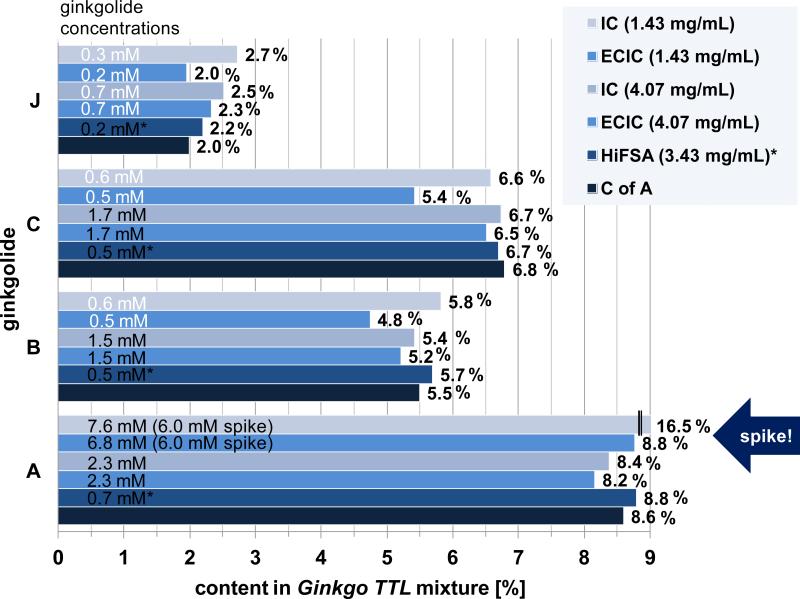

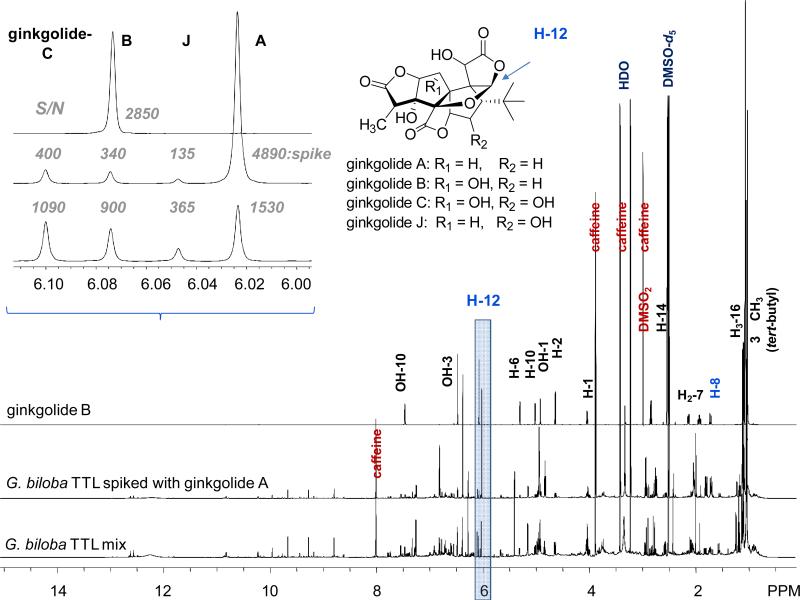

The present standardized qHNMR method (see Table S2, Supporting Information for standard AcquPs and ProcPs) was applied to two tasks: (i) the purity assessment of an isolated reference material of a NP, exemplified for ginkgolide B, and (ii) the quantification multiple constituents in a mixture, exemplified for four ginkgolides (A, B, C, J) in a Ginkgo biloba terpene lactone mixture (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Quantitative determination of the content of four ginkgolides in a certified sample of terpene lactones (USP), comparing three different qHNMR methods with the LC-based Certificate of Analysis (CofA). The results recently obtained by 1H iterative full spin analysis (HiFSA) based qHNMR (Napolitano et al., 2012) showed excellent agreement with the CofA specifications. Furthermore, ECIC or IC based qHNMR with similar sample amount (4.07 mg/mL) as HiFSA (3.43 mg/mL) gave very similar values. The error of the ECIC/IC method is expected to be higher as only isolated signals can be used for quantification, whereas HiFSA considers all resonances of the analyte. The increase in deviation from HiFSA/CofA values in the small samples ECIC/IC (1.43 mg/mL) is consistent with the increasing error at analyte concentrations ≤ 0.9 mM (white values, also see main text). A known amount of ginkgolide A had been added to that sample (spike) before analysis, increasing the total concentration of ginkgolide A to 6.8 mM, which enabled the accurate determination of the genuine amount of ginkgolide A in the sample, consistent with HiFSA/CofA values.

The qHNMR spectra for task (i) were collected on three days by two operators. The purity of the sample was determined using three qHNMR methods: the 100% method (result: 98.9% purity), the IC (DMSO2 as internal calibrant), and the ECIC method using the established CC (Figure 5). The results for both IC and ECIC are summarized in Table S7, Supporting Information. The sample purity found for the two absolute qHNMR methods were 51.2% (IC) and 51.3% (ECIC), using ginkgolide B's H-8 (dd, δH 1.730 ppm, Figure 8) as the representative integration signal. The discrepancy between the purity determined by the 100% method vs. the absolute calibration methods, IC or ECIC, must be due to impurities that are 1H NMR “transparent” (e.g. salts, silica) or that are not quantitatively detectible by qHNMR, such as water. In the present case, it was noticed that the HDO signal in the spectrum accounted for 67% of the total spectrum integral. This observation, and the otherwise good precision and accuracy of the qHNMR protocol, allowed the conclusion that the ginkgolide B sample contained large amounts of “residual” water, either as solvate or moisture, representing a typical impurity, which is only accounted for to some degree when using the modified 100% method. Further analysis of the qHNMR spectrum led to the identification of 0.45% of ginkgolide A (S/N = 13, s, H-12) as structurally related impurity. Relative to the 2.87 mM sample concentration (prepared as 5.66 mM at 51.3% purity), this represents a concentration of 0.03 mM, which was just above the LOD of the present qHNMR method, and it fell into the nonlinear range of the CC (Figure 7). Under these S/N conditions the respective error for ECIC qHNMR is in the range of 50% points (%%; Figure 6), indicating that its quantification may not be reliable. Despite these limitations, the results also underscore the strengths of the present ECIC qHNMR method: even at very low concentrations, qHNMR still allows the unambiguous detection and identification of impurities. Therefore, once the impurity is identified, an informed decision can be made, whether a more sensitive measurement is justified. This could be achieve in two ways: preparation of a 30-fold more concentrated sample (~ 170 mM by weight), or re-acquisition to obtain a S/N of about 150 for the impurity, noting that e.g. a 10-fold S/N requires 100-fold number of scans (see section Acqu1).

Figure 8.

qHNMR spectra of the natural product examples (600MHz, DMSO-d6). Ginkgolide B (5.6 mM, DMSO2: 1.5 mM ), the compendial Gingko terpene trilactone (TTL) mixture (4.07 mg/mL; caffeine: 7.3 mM), and TTL (1.43 mg/mL, caffeine: 6.9 mM) spiked with ginkgolide A (6.0 mM) The spectral region containing the Hs-12 was used for quantitative analysis of the four terpene lactones present in the mixture.

As part of task (ii), a certified sample of a Ginkgo terpene lactone (TTL) mixture was analyzed and the content of the ginkgolides A, B, C, and J determined using different sample concentrations (Figure 8). The present ECIC method yielded quantitative results in good general agreement with the IC results (7.30 mM caffeine, H-8, δH 8.000 ppm) and the LC-based certificate of analysis (C of A; Figure 9). As shown above, the quantification error for the present ECIC method becomes substantial for sample concentrations of ≤ 0.9 mM, as indicated by the results for the minor ginkgolides B, C and J in the low-concentration sample (ECIC 1.43 mg, Figure 9). On the other hand, the quantification of ginkgolide A, which was added (analogous to spiking in LC) into the sample at a concentration of 5.97 mM, was in agreement with the CofA and the very recently published qHNMR method using 1H iterative full spin analysis (HiFSA; Figure 9) (Napolitano et al., 2012). The outcome of the Ginkgo TTL quantification confirms both the capabilities and the limitations of the ECIC method present here. ECIC can be used to reliably determine the absolute concentration of multiple constituents in various NPs, including mixtures. At lower sample concentrations, the quantification error becomes the method's limitation. This is mainly due to the decreasing S/N levels and elevated baselines. Both can be overcome to some degree by longer acquisition times, but quantification errors in mixtures also result from signal overlap, which becomes substantial for the quantification of minor constituents. The IC results generally suffer from the same shortcomings and limitations as ECIC, and for more reliable quantification at lower abundance and in complex mixtures, the recently introduced HiFSA approach (Napolitano et al., 2012) is the preferred method. Notably, the HiFSA study employed the same AcquPs as the present study. This underscores the validity of the raw qHNMR data, resulting from proper choices for AcquPs, and the importance of the post-acquisition method (classical 1D vs. HiFSA approach) and parameters (ProcPs).

While previous studies have reported validated qHNMR methods using internal calibration (IC), the present study focused on the analysis of NP isolates and complex botanical extract samples, for both of which the addition of an IC is not practical. The presented qHNMR method uses ECIC, a dual calibration method in which the omnipresent residual solvent signal is used for IC and both caffeine and dimethylsulfone are used for EC. In practice, calibration can be readily performed for individual solvent batches. The ECIC method was built on a CC from a two component EC sample and, thus, met published validation guidelines for LC-based quantitative methods. In addition, because two calibrants were present in the EC sample, the ECIC qHNMR results could be verified by the IC method. The influence of AcquPs and ProcPs on the quantitative results of the ECIC qHNMR method were examined and discussed.

The AcquPs were selected to yield a method with a high dynamic range, which is well suited for the quantitative analysis of botanical extracts or the purity analysis of residually complex NP isolates. The presented ECIC qHNMR method offers a dynamic range of at least 5,000:1. In addition, different methods to determine the LOD and LOQ were compared and the error values of the ECIC method calculated. As a result, the LOQ for a 10% error margin was determined to be 0.9 mM, and the LOD at the same confidence level was determined as 0.023 mM. It was further observed that the precision of IC and ECIC qHNMR results fell within a 5% error window, while the accuracy of ECIC was slightly compromised, yielding values at about 5% above the sample concentrations by weight. While previously published qHNMR methods have reported quantification errors at the 1%-level, these results were obtained under considerably different conditions. In contrast to the present method, those methods were developed with highly pure, analytical standards in single-compound samples, and were not limited by the extensive signal overlap commonly observed in NP samples. The quantitative analysis of crowded spectral regions requires a substantial reduction of the integral ranges, and, therefore, increases the measurement error. These factors also affect the use of window functions (resulting signal width) and internal calibrants (solvent vs. added calibrant).

The use of both EC and ECIC methods requires the evaluation of the influence of post-acquisition processing on the quantitative results. In the present study, three processing software packages were compared (Bruker TopSpin, MNova, NUTS). In summary, each software tool had distinct strengths, but also certain limitations and possesses a distinct profile of “systematic error”. The systematic error is likely due to software specific algorithms used in the internal calculations. Therefore, for qHNMR validation across studies and laboratories, the same software and identical ProcPs would need to be used in order to work with identical systematic errors and maximize reproducibility. Data processing is a major component of any NMR workflow, both qualitative and quantitative, and it remains a challenge to make it a fully transparent task for NMR users, working with partially proprietary tools. However, meticulous documentation of AcquPs and ProcPs will be very important for method validation, especially when different facilities are used and a different software tool is applied. In this respect, one recent publication has reported an automated qHNMR protocol using EC. The protocol is based on a self-developed R-script that allows the automatic integration, outlier detection, and determination of concentrations of the analyte samples by relating signal areas of analyte and calibrant (Liu et al., 2012). The fact that the authors have developed their own R script seems to support our findings for the need of transparency in NMR data processing.

The present qHNMR method was developed to fit the needs of NP mixtures and was shown to yield accurate qHNMR results for four ginkgolides present in a compendial Ginkgo terpene lactone mixture. For analyte concentrations above 0.9 mM, the ECIC results were comparable to previously published qHNMR results which used an approach based on 1H iterative full spin analysis (HiFSA). Using a ginkgolide B reference material as another example, the ECIC method yielded data that allowed the absolute determination of ginkgolide B as 2.87 mM in a 5.66 mM sample by weight, revealing a purity of only 51.3%. The data also allowed for the identification of 0.45% ginkgolide A impurity at a S/N of around 13 in the 2.87 mM sample of ginkgolide B.

Finally, the findings of this study were compiled in the form of a “qHNMR recipe” (Chart 1), which can accommodate the various methods of calibration (ECIC, IC) for absolute quantification, in addition to the most simple 100% methods. The qHNMR recipe is intended to provide NMR analysts guidance for qHNMR method development based on their respective analytical requirements. In addition, Table S2 summarizes the standard AcquPs and ProcPs determined during this study, which can serve as a starting point of parameters for ECIC qHNMR method development.

Chart 1.

From a broader perspective, the data and observations from the present study indicate that future validated qHNMR methods could be fully independent of internal calibration. While the presented ECIC qHNMR method was designed to follow and has shown to accomplish SLV guidelines, all currently available validation protocols are LC-based (Bruce et al., 1998; ICH 1995) and, thus, do not reflect qHNMR specific aspects of validation. Examples for the non-congruence of quantification parameters in qHNMR vs. LC have been addressed in the sections on the validation of the parameters above. Furthermore, considering that for qHNMR all IC methods require re-contamination and frequently produce unfavorable signal overlap, the development of EC-only based qHNMR protocols is preferable and validation will become feasible once qHNMR-specific guidelines become available.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT