Abstract

Safety net systems need innovative diabetes self-management programs for linguistically diverse patients. A low-income government-sponsored managed care plan implemented a 27-week automated telephone self-management support (ATSM) / health coaching intervention for English, Spanish-, and Cantonese-speaking members from four publicly-funded clinics in a practice-based research network. Compared to waitlist, immediate intervention participants had greater 6-month improvements in overall diabetes self-care behaviors (standardized effect size [ES] 0.29, p<0.01) and SF-12 physical scores (ES 0.25, p=0.03); changes in patient-centered processes of care and cardiometabolic outcomes did not differ. ATSM is a strategy for improving patient-reported self-management and may also improve some outcomes.

Keywords: self care, diabetes, health information technology, health literacy, limited English proficiency, chronic disease, healthcare disparities, practice-based research network

Introduction

Patient-centered, culturally concordant care is a cornerstone of chronic disease care (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Patients with limited health literacy (LHL) and limited English proficiency (LEP) face barriers to communication and access leading to suboptimal care and poor health outcomes (Davis et al., 2006; Fernandez et al., 2011; Sarkar et al., 2010; Schillinger, Bindman, Wang, Stewart, & Piette, 2004; Schillinger, Barton, Karter, Wang, & Adler, 2006; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010).

With health care reform, Medicaid will expand coverage among low-income adults with chronic medical conditions, particularly for LHL and LEP patients (Martin & Parker, 2011; Maxwell, Cortes, Schneider, Graves, & Rosman, 2011; Pande, Ross-Degnan, Zaslavsky, & Salomon, 2011; Sentell, 2012; Sommers, Tomasi, Swartz, & Epstein, 2012). Medicaid managed care administrators report a need for innovative strategies to promote diabetes self-management among these populations (Goldman, Handley, Rundall, & Schillinger, 2007; Rittenhouse & Robinson, 2006). Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is an increasingly important patient-centered care goal that also predicts utilization (DeSalvo et al., 2009; Dorr et al., 2006; Fleishman, Cohen, Manning, & Kosinski, 2006; Magid, Houry, Ellis, Lyons, & Rumsfeld, 2004; Montori & Fernandez-Balsells, 2009; Norris, Engelgau, & Narayan, 2001; Rubin & Peyrot, 1999; Selby, Beal, & Frank, 2012; Singh, Nelson, Fink, & Nichol, 2005).

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services highlighted automated telephone self-management (ATSM) as an exemplary strategy to enhance outcomes for LHL populations (Institute of Medicine, 2010). A randomized controlled trial among safety net patients with poorly controlled diabetes was associated with improvements in self-management behaviors, self-reported days in bed, and interference in daily activities, with a cost utility for functional outcomes comparable to other diabetes interventions (Handley, Shumway, & Schillinger, 2008; Schillinger, Handley, Wang, & Hammer, 2009).

To translate research into practice, a low-income government-sponsored managed care plan implemented language-concordant ATSM with health coaching for members with diabetes at 4 clinics within an urban practice-based research network (PBRN). The Self-Management Automated and Real-Time Telephonic Support Study (SMARTSteps / Pasos Positivos /  ) is a controlled quasi-experimental evaluation of the program's impact on health-related quality of life, diabetes self-management, patient-centered processes of care, and cardiometabolic outcomes.

) is a controlled quasi-experimental evaluation of the program's impact on health-related quality of life, diabetes self-management, patient-centered processes of care, and cardiometabolic outcomes.

Methods

San Francisco Health Plan (SFHP) is a non-profit government-sponsored managed care plan created to provide high quality medical care to the largest number of low-income San Francisco residents possible. Community Health Network of San Francisco (CHNSF) – the public health department's integrated healthcare delivery system – is part of the San Francisco Bay Area Collaborative Research Network (http://accelerate.ucsf.edu/community/sfbaycrn), UCSF's primary care practice-based research network that supports the development and dissemination of practice-based evidence that improve in primary care practices and health outcomes in diverse communities.

The quasi-experimental evaluation used a waitlist variant of a stepped wedge design, in which SFHP randomized participants to waitlist or immediate intervention during four recruitment waves (April 2009 – March 2011) and waitlist participant crossed over to intervention after 6 months (Handley, Schillinger, & Shiboski, 2011; Ratanawongsa et al., 2012). This design permitted controlled evaluation, but with less intensive implementation staffing, and allowed all participants to participate in the intervention.

Eligible members were English-, Cantonese-, or Spanish-speaking adults (age ≥ 18) with diabetes type 1 or 2 and ≥1 primary care visit in the preceding 24 months to one of four CHNSF clinics. Members who were pregnant, lacked a touch-tone phone, leaving the region, or unable to provide verbal consent were ineligible. We retained in this evaluation those who disenrolled from SFHP membership during the study. We assessed diabetes diagnoses through the CHNSF diabetes registry or a combination of SFHP claims with confirmation clinician-documented diagnosis of diabetes, fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl, or HbA1c ≥ 7% (American Diabetes Association, 2009).

SFHP conducted recruitment through mailed post cards and scripted outreach calls. Enrollment workers confirmed eligibility by phone, offered $25 gift card incentives, and assessed willingness to complete evaluation interviews administered by UCSF bilingual research assistants, who later obtained verbal consent by telephone. The Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, approved the evaluation.

Interventions

SFHP assigned program participants through language-stratified randomization to 2 immediate intervention arms and 2 waitlist control arms. Tailored for literacy, language, and culture with extensive patient input (Schillinger et al., 2008), the ATSM system provided 27 weeks of 8-12 minute weekly calls in English, Cantonese, or Spanish. Calls offered rotating sets of queries about self-care, psychosocial issues, and access to preventive services. Patients received health education messages using narratives based on their touchtone responses. A series of cognitive interviews with English-, Spanish-, and Cantonese-speaking patients were used to develop and refine both the queries and health education messages, as well as the response protocols (Schillinger et al., 2008). “Out-of-range” responses triggered callbacks within 3 days from a language-concordant SFHP lay health coaches, who engaged in collaborative goal-setting to form patient-centered action plans (Bodenheimer & Handley, 2009; Fisher, Brownson, O'Toole, Shetty, Anwuri, & Glasgow, 2005; Lorig, 2006). Health coaches – supervised by an SFHP registered nurse care manager – documented in the SFHP care management database system, but contacted primary care clinics by email, fax, and phone for actionable concerns.

One of the two intervention arms received the ATSM intervention as well as medication activation and intensification coaching, triggered by self-reported non-adherence on ATSM responses, refill non-adherence by pharmacy claims, or suboptimal cardiometabolic measures (Ratanawongsa et al., 2012). This evaluation paper focuses on the comparison between the combined ATSM intervention groups and the waitlist control.

Waitlist participants received usual clinical care and existing SFHP benefits (reminders and incentives for receipt of recommended health services). After the 6-month waitlist period, participants crossed over to begin one of the 2 interventions.

Measures

Structured computer-assisted telephone interviews occurred within 2 weeks of randomization and at 6-month follow-up (after the conclusion of ATSM for immediate intervention participants or prior to crossover for waitlist participants). Spanish and Cantonese questionnaires were translated and back-translated into English. Participants received a $50 gift card for each interview.

Self-reported socio-demographic variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, language, English proficiency (Wilson, Chen, Grumbach, Wang, & Fernandez, 2005), years since immigration to the U.S., marital status, educational attainment, employment status, annual household income, self-reported health literacy (Chew et al., 2008; Sarkar, Schillinger, Lopez, & Sudore, 2011), and duration of diabetes.

HRQOL was captured by SF-12 physical and mental component scores, calculated and transformed to a 100-point scale (Ware, Kosinski, & Keller, 1996). Secondary outcomes included:

Self-reported days spent mostly in bed due to health problems, in the prior 30 days (Schillinger et al., 2009)

Diabetes “often” or “always” interfering with normal daily activities (Gill, Allore, & Guo, 2003; Piette, Weinberger, & McPhee, 2000; Schillinger et al., 2009)

Diabetes self-care in the preceding 7 days (0 to 7 overall and for each subscale) (Fleming et al., 2001; Toobert, Hampson, & Glasgow, 2000)

Diabetes self-efficacy (“how difficult has it been for you to do the following things for your diabetes exactly as members of your diabetes health care team recommended”) over the prior 6 months (0 to 100 scale) (Heisler, Bouknight, Hayward, Smith, & Kerr, 2002)

Patient Assessment of Care for Chronic Conditions (PACIC) over the prior 6 months (100-point scale) (Glasgow, Whitesides, Nelson, & King, 2005)

Interpersonal Processes of Care (IPC) over the prior 6 months (100-point scale) (Schillinger et al., 2009; Stewart, Napoles-Springer, Gregorich, & Santoyo-Olsson, 2007)

For all program participants, regardless of interview participation, we abstracted cardiometabolic measures obtained through routine care – hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and blood pressure (BP) – from the CHNSF electronic health record, clinical registry, and paper charts 45 days before or 45 days after target dates (baseline, 6 months, and 12 months). If multiple measures were available, we used values closest to the target date.

Analyses

We assessed for differences in baseline characteristics between waitlist and immediate intervention participants using chi-square tests, Fisher's exact tests, t-tests, and Wilcoxon tests. We compared 6-month changes for each outcome for the waitlist control and immediate intervention groups, on an intent-to-treat basis, using linear and logistic regression adjusting for baseline values. We calculated standardized effect sizes for scales. For self-reported days in bed, we used negative binomial models to calculate log mean differences and generated incidence rate ratios.

Estimating 500 eligible SFHP members, we anticipated recruitment of 260 participants, with 10% drop-out or loss to follow-up at 6 months. We calculated that we would have 80% power to detect a standardized effect size (SE) of 0.35 in the primary outcome of SF-12 scores. We estimated 20% of participants would have missing cardiometabolic data, yielding 80% power to detect a difference in HbA1c of 0.51% (SE 0.28).

Results

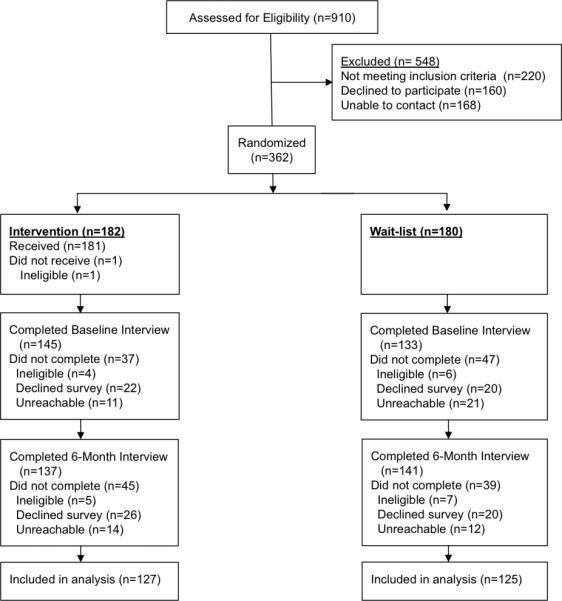

The Figure depicts the CONSORT flow diagram. Among those randomized, 252 participants (70%) completed both a baseline and 6-month follow-up interviews. Table 1 describes sociodemographic and medical characteristics of both groups, which had no observable differences. Among the 151 intervention participants who received all 27 weeks of calls, 85% completed at least one call. Immediate intervention participants completed a median of 20 calls (interquartile range 5-25).

Figure.

Patient recruitment and randomization flowchart for a quasi-experimental evaluation study of a language-concordant automated telephone self-management / health coaching diabetes intervention by a low-income government-sponsored health care plan

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and medical characteristics in a quasi-experimental evaluation study of a language-concordant automated telephone self-management / health coaching diabetes intervention by a low-income government-sponsored health care plan (N=252)

| Characteristic | Intervention (n=127) | Waitlist (n=125) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 56.5 (7.9) | 55.0 (8.6) | 0.21 |

| Women, n (%) | 98 (77.2) | 89 (71.2) | 0.28 |

| Race / ethnicity, n (%) | 0.40† | ||

| Latino | 32 (25.2) | 25 (20.0) | |

| Black / African-American | 7 (5.5) | 12 (9.6) | |

| Asian / Pacific Islander | 77 (60.6) | 78 (62.4) | |

| White / Caucasian | 7 (5.5) | 9 (7.2) | |

| Multi-Ethnic / Other | 4 (3.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Born outside the U.S., n (%) | 110 (86.6) | 106 (84.8) | 0.68 |

| Language, n (%) | 0.97 | ||

| Cantonese-speaking | 69 (54.3) | 69 (55.2) | |

| Spanish-speaking | 25 (19.7) | 23 (18.4) | |

| Language-concordant primary care provider | 33 (36.7) | 26 (29.5) | 0.31 |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | 0.41 | ||

| 8th grade education or less | 50 (39.4) | 58 (46.4) | |

| Some high school | 13 (10.2) | 12 (9.6) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 33 (26.0) | 22 (17.6) | |

| College graduate or above | 31 (24.4) | 33 (26.4) | |

| Limited health literacy, n (%) | 58 (46.0) | 50 (40.0) | 0.33 |

| Employment status, n (%) | 0.57 | ||

| Employed full-time | 28 (22.0) | 26 (20.8) | |

| Part-time | 63 (49.6) | 58 (46.4) | |

| Unemployed | 12 (9.4) | 15 (12.0) | |

| Disabled | 7 (5.0) | 13 (10.4) | |

| Homemaker / Retired / Other | 17 (13.4) | 13 (10.4) | |

| Annual household income, n (%) | 0.99 | ||

| ≤ $20,000 | 73 (63.6) | 75 (63.0) | |

| $20,001 – 30,000 | 24 (20.3) | 25 (21.0) | |

| >$30,000 | 19 (16.1) | 19 (16.0) | |

| Financial Class - Insurance type, n (%) | 0.61‡ | ||

| Medicaid | 28 (22.2) | 22 (17.6) | |

| Medicare | 4 (3.2) | 7 (5.6) | |

| Uninsured/Commercial | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Healthy Worker/Healthy San Francisco | 93 (73.8) | 94 (75.2) | |

| Diabetes years, mean (SD) | 6.9 (5.9) | 7.2 (5.4) | 0.36 |

| Insulin treatment, n (%) | 25 (19.7) | 18 (14.4) | 0.26 |

| Hemoglobin A1c >8.0%, n (%) | 37 (29.8) | 29 (24.4) | 0.34 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD) | 7.8 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.3) | 0.13 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean mm Hg (SD) | 127.3 (17.3) | 128.1 (18.2) | 0.60 |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mean mg/dL (SD) | 92.7 (30.3) | 93.5 (31.5) | 0.84 |

P-values derived from chi-square tests for categorical variables if appropriate and Fisher's exact tests if needed, t-tests for interval variables if normally distributed and Wilcoxon tests if interval variables not normally distributed (age, diabetes duration and cardiometabolic indicators).

P-values calculated based on categories of Asian / Pacific Islander, Black / African-American, Hispanic / Latino, Multiethnic / Other, and White / Caucasian

P-values calculated based on categories of Healthy Worker / Healthy San Francisco, Medicaid (Community Alternatives Program or Fee-For-Service), Medicare, and Commercial / Uninsured.

Table 2 shows all outcomes comparing intervention to waitlist control participants. Intervention participants reported better changes in overall diabetes self-care behaviors with standardized effect sizes (ES 0.29, p<0.01), as well as subscale improvements in glucose monitoring (ES 0.30, p<0.01) and foot checks (ES 0.32, p<0.01). However, changes in self-efficacy, physical activity and exercise time, PACIC scores, and IPC scores did not differ between immediate intervention and waitlist control participants. We also observed a possible 6-month improvement in the primary outcome measure, the SF-12 physical component scores (standardized effect size [ES] 0.25, p=0.03), without concomitant improvements in SF-12 mental component scores, self-reported days in bed, or diabetes interference.

Table 2.

Outcomes for intervention and waitlist controls in a quasi-experimental evaluation study of a language-concordant automated telephone self-management / health coaching diabetes intervention by a low-income government-sponsored health care plan (n=252)

| Outcome | Intervention (n=127) | Waitlist (n=125) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 Months | Baseline | 6 Months | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Difference* (95% CI) | Standardized Effect Size* | p-value | |

| Physical SF-12 | 46.1 (9.0) | 47.4 (8.8) | 46.5 (9.5) | 45.5 (10.1) | 2.0 (0.1,3.9) | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| Mental SF-12 | 48.7 (10.7) | 50.4 (11.1) | 49.9 (10.4) | 49.4 (11.0) | 1.4 (−0.9,3.6) | 0.14 | 0.23 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Difference* (95% CI) | Rate Ratio* (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported days in bed in prior month | 1.4 (4.5) | 1.0 (3.3) | 1.0 (3.2) | 1.6 (5.1) | −0.5 (−1.3, 0.13) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.25 |

| Proportion | Proportion | Proportion | Proportion | Odds Ratio* (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes interference† | 6.3% | 3.9% | 8.9% | 8.8% | 0.5 (0.2, 1.4) | 0.18 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Difference* (95% CI) | Standardized Effect Size* | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Diabetes Self-Care | 4.5 (1.0) | 5.1 (0.9) | 4.4 (1.0) | 4.8 (1.1) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.29 | <0.01 |

| Medication adherence | 6.5 0.8) | 6.7 (0.7) | 6.3 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.1) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.01 | 0.87 |

| Self-efficacy | 76.7 (13.7) | 82.6 (12.6) | 73.5 (17.7) | 80.1 (16.0) | 1.1 (−2.1, 4.2) | 0.07 | 0.49 |

| Patient assessment of chronic illness care | 44.0 (23.9) | 55.5 (24.1) | 45.2 (23.0) | 54.9 (23.3) | 1.3 (−3.0, 5.6) | 0.07 | 0.54 |

| Interpersonal processes of care | 58.4 (11.7) | 56.5 (11.1) | 58.3 (11.3) | 54.5 (11.3) | 2.0 (−0.4, 4.4) | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 8.0 (1.7) | 7.5 (1.1) | 7.9 (1.5) | 7.7 (1.2) | −0.3 (−0.6, 0.1) | −0.22 | 0.13 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 129 (20.2) | 129 (16.9) | 128 (19.2) | 128 (16.2) | 0.6 (−3.8, 5.1) | 0.03 | 0.78 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 74.1 (12.4) | 75.8 (11.6) | 76.0 (12.6) | 74.6 (9.9) | 2.1 (−0.6, 4.9) | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 121.0 (42.4) | 106.0 (33.0) | 98.9 (29.1) | 90.8 (25.4) | 11.0 (−6.5, 28.4) | 0.28 | 0.22 |

Regression adjusted for baseline values.

Proportion of participants choosing responses of “often” or “always.”

Using baseline and 6-month follow-up values for 106 participants for HbA1c, 167 participants for BP, and 39 participants for LDL, we found no differences between waitlist and intervention groups in cardiometabolic outcomes.

Discussion

This study waitlist-controlled study of automated self management (ATSM) support in diabetic patients confirms some benefits documented in prior randomized controlled trials (Handley, Shumway, & Schillinger, 2008; Schillinger, Handley, Wang, & Hammer, 2009) .In particular, our ATSM documented improvement in patients' self-management behaviors and possible improvement in physical function. The study is also important because it demonstrates the potential value of waitlist-controlled method in buy practice setting where randomization would not be possible.

This PBRN study harnessed partnerships among a government-sponsored health plan, a safety net integrated health care system, and practice-based implementation researchers to translate a self-management support intervention from a randomized controlled trial into a practical implementation for a vulnerable population (Beach et al., 2006; Bonell et al., 2011; Chin et al., 2001; Cooper, Hill, & Powe, 2002; Glasgow, Davis, Funnell, & Beck, 2003; Green, 2008; Tunis, Stryer, & Clancy, 2003). Patients with LHL and LEP lack access to traditional self-management support, a critical component of chronic disease care delivery (Fisher, Brownson, O'Toole, Shetty, Anwuri, & Glasgow, 2005; Institute of Medicine, 2001; Institute of Medicine, 2004; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010). Safety net implementation of self-management programs requires staff re-training, organizational change, investments in information technology, and tailoring for diverse populations (Eakin, Bull, Glasgow, & Mason, 2002; Fiscella & Geiger, 2006; Regenstein et al., 2005; Sarkar et al., 2008; Wagner, Austin, & Von Korff, 1996). ATSM with health coaching may represent a more scalable strategy for health plans and health systems aiming to enhance chronic disease outcomes at a population-level (Bennett, Coleman, Parry, Bodenheimer, & Chen, 2010; Margolius et al., 2012; Wolever & Eisenberg, 2011).

Our findings showed differences in some outcomes measured over shorter timeframes (diabetes self-management over 1 week and SF-12 physical component score for last 30 days) but not longer-term outcomes (IPC, PACIC, and cardiometabolic outcomes over 6 months). This may be due to the fact that the intervention lasted 6 months and behavior change occurs slowly over time; because of the crossover design, we were not able to measure how differences may have been sustained or changed over 12 months. The 6-month timeframe may partly explain why self-efficacy scores were not significantly different, but this measure also depends on patient perceptions of the patient-centeredness of the health care team's recommendations and communication styles. Thus, this measure may correlate more with the PACIC and IPC measures.

The lack of improvements in patient-centered processes (PACIC and IPC) or cardiometabolic outcomes may be due to SFHP health coach inability to document within the electronic health record, SFHP lack of prescribing authority, and the population's good baseline control. However, cardiometabolic targets may not correlate with quality of life and must be adjusted based on individuals’ medical and social comorbidities, values, and preferences (American Diabetes Association, 2009; Montori & Fernandez-Balsells, 2009; Sundaram et al., 2007). Future interventions should consider health IT-facilitated strategies to integrate health plan interventions with patient-centered medical homes.

The evaluation had limitations. The change in HRQOL was small. Phone-based population recruitment may have resulted in selection bias. SFHP health coach turnover may have caused variation in the fidelity of health coach counseling and documentation. Health coaches were linguistically but not necessarily culturally-concordant with patients. The results may not be generalizable to other Medicaid managed care populations. Recruitment and cardiometabolic data availability did not reach target goals for evaluating cardiometabolic outcomes. Finally, additional patient stakeholder engagement in defining the content and approaches to the health coaching component may have improved the effectiveness of this intervention. For example, in recently funded work adapting SMARTSteps for diabetes prevention among women with recent gestational diabetes, the research team is partnering with local Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) programs and conducting focus groups to elicit post-partum women's perspectives about their health concerns, barriers to care, and desires for prevention support. This effort will help tailor the relevance of health messages, coaching narratives, and protocols for this population's specific goals and preferences, in addition to language and literacy (Handley, 2013).

In summary, this PRBN study demonstrated that a health IT self-management innovation for diverse low-income beneficiaries with diabetes was associated with high rates of engagement, enhanced self-care, and a modest improvements in one measure of HRQOL. Medicaid plans may benefit from efficient implementation of similar HIT-facilitated interventions to improve self-management and HRQOL in their populations. Moreover, this waitlist-controlled study of ATSM confirms the result of a previous RCT. This finding alone is important for those who need to conduct research in busy practice settings where randomization is not possible.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: The San Francisco Health Plan participated in the design and implementation of the intervention and evaluation. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grants R18HS017261 and 1R03HS020684-01; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant 5U58DP002007-03; Health Delivery Systems Center for Diabetes Translational Research (CDTR) funded through NIDDK grant 1P30-DK092924; National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities #P60MD006902; and the McKesson Foundation. NIH grant UL1 RR024131 supports the UCSF Collaborative Research Network. No funders had any role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: NCT00683020

Conflicts of Interest None of the authors had conflicts of interest, and the funders had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception and design, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, including final approval of the version to be published.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, Md: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes--2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 1):S13–61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Gary TL, Price EG, Robinson K, Gozu A, Palacio A, Cooper LA. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: A systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett HD, Coleman EA, Parry C, Bodenheimer T, Chen EH. Health coaching for patients with chronic illness. Family Practice Management. 2010;17(5):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Handley MA. Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: An exploration and status report. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;76(2):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.001. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell CP, Hargreaves J, Cousens S, Ross D, Hayes R, Petticrew M, Kirkwood BR. Alternatives to randomisation in the evaluation of public health interventions: Design challenges and solutions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2011;65(7):582–587. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, Vanryn M. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Cook S, Jin L, Drum ML, Harrison JF, Koppert J, Chiu SC. Barriers to providing diabetes care in community health centers. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):268–274. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Hill MN, Powe NR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(6):477–486. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, 3rd, Thompson JA, Tilson HH, Neuberger M, Parker RM. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(12):887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo KB, Jones TM, Peabody J, McDonald J, Fihn S, Fan V, Muntner P. Health care expenditure prediction with a single item, self-rated health measure. Medical Care. 2009;47(4):440–447. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190b716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr DA, Jones SS, Burns L, Donnelly SM, Brunker CP, Wilcox A, Clayton PD. Use of health-related, quality-of-life metrics to predict mortality and hospitalizations in community-dwelling seniors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54(4):667–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin EG, Bull SS, Glasgow RE, Mason M. Reaching those most in need: A review of diabetes self-management interventions in disadvantaged populations. Diabetes/metabolism Research and Reviews. 2002;18(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Warton EM, Adler N, Moffet HH, Schenker Y, Karter AJ. Language barriers, physician-patient language concordance, and glycemic control among insured Latinos with diabetes: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(2):170–176. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Geiger HJ. Health information technology and quality improvement for community health centers. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2006;25(2):405–412. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O'Toole ML, Shetty G, Anwuri VV, Glasgow RE. Ecological approaches to self-management: The case of diabetes. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(9):1523–1535. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O'Toole ML, Shetty G, Anwuri VV, Glasgow RE. Ecological approaches to self-management: The case of diabetes. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(9):1523–1535. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman JA, Cohen JW, Manning WG, Kosinski M. Using the SF-12 health status measure to improve predictions of medical expenditures. Medical Care. 2006;44(5 Suppl):I54–63. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000208141.02083.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming BB, Greenfield S, Engelgau MM, Pogach LM, Clauser SB, Parrott MA. The diabetes quality improvement project: Moving science into health policy to gain an edge on the diabetes epidemic. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(10):1815–1820. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.10.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Allore H, Guo Z. Restricted activity and functional decline among community-living older persons. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(11):1317–1322. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Davis CL, Funnell MM, Beck A. Implementing practical interventions to support chronic illness self-management. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety. 2003;29(11):563–574. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Whitesides H, Nelson CC, King DK. Use of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) with diabetic patients: Relationship to patient characteristics, receipt of care, and self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2655–2661. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman LE, Handley M, Rundall TG, Schillinger D. Current and future directions in Medi-cal chronic disease care management: A view from the top. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2007;13(5):263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW. Making research relevant: If it is an evidence-based practice, where's the practice-based evidence? Family Practice. 2008;25(Suppl 1):i20–4. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley MA. Adapting an automated telephone support program to prevent type 2 diabetes. National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant 5P60MD006902-02. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Handley MA, Schillinger D, Shiboski S. Quasi-experimental designs in practice-based research settings: Design and implementation considerations. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2011;24(5):589–596. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley MA, Shumway M, Schillinger D. Cost-effectiveness of automated telephone self-management support with nurse care management among patients with diabetes. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(6):512–518. doi: 10.1370/afm.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler M, Bouknight RR, Hayward RA, Smith DM, Kerr EA. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(4):243–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig K. Action planning: A call to action. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2006;19(3):324–325. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid DJ, Houry D, Ellis J, Lyons E, Rumsfeld JS. Health-related quality of life predicts emergency department utilization for patients with asthma. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2004;43(5):551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolius D, Bodenheimer T, Bennett H, Wong J, Ngo V, Padilla G, Thom DH. Health coaching to improve hypertension treatment in a low-income, minority population. Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(3):199–205. doi: 10.1370/afm.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LT, Parker RM. Insurance expansion and health literacy. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(8):874–875. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J, Cortes DE, Schneider KL, Graves A, Rosman B. Massachusetts' health care reform increased access to care for Hispanics, but disparities remain. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2011;30(8):1451–1460. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montori VM, Fernandez-Balsells M. Glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: Time for an evidence-based about-face? Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150(11):803–808. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):561–587. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande AH, Ross-Degnan D, Zaslavsky AM, Salomon JA. Effects of healthcare reforms on coverage, access, and disparities: Quasi-experimental analysis of evidence from Massachusetts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Weinberger M, McPhee SJ. The effect of automated calls with telephone nurse follow-up on patient-centered outcomes of diabetes care: A randomized, controlled trial. Medical Care. 2000;38(2):218–230. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratanawongsa N, Handley MA, Quan J, Sarkar U, Pfeifer K, Soria C, Schillinger D. Quasi-experimental trial of diabetes self-management automated and real-time telephonic support (SMARTSteps) in a Medicaid managed care plan: Study protocol. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regenstein M, Huang J, Cummings L, Lessler D, Reilly B, Schillinger D. Caring for patients with diabetes in safety net hospitals and health systems (publication no. 826) 2005.

- Rittenhouse DR, Robinson JC. Improving quality in Medicaid: The use of care management processes for chronic illness and preventive care. Medical Care. 2006;44(1):47–54. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000188992.48592.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes/metabolism Research and Reviews. 1999;15(3):205–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<205::aid-dmrr29>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar U, Handley MA, Gupta R, Tang A, Murphy E, Seligman HK, Schillinger D. What happens between visits? Adverse and potential adverse events among a low-income, urban, ambulatory population with diabetes. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2010;19(3):223–228. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.029116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar U, Piette JD, Gonzales R, Lessler D, Chew LD, Reilly B, Schillinger D. Preferences for self-management support: Findings from a survey of diabetes patients in safety-net health systems. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;70(1):102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar U, Schillinger D, Lopez A, Sudore R. Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26(3):265–265–271. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Barton LR, Karter AJ, Wang F, Adler N. Does literacy mediate the relationship between education and health outcomes? A study of a low-income population with diabetes. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974) 2006;121(3):245–254. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Bindman A, Wang F, Stewart A, Piette J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2004;52(3):315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Hammer H, Wang F, Palacios J, McLean I, Tang A, Handley M. Seeing in 3-D: Examining the reach of diabetes self-management support strategies in a public health care system. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2008;35(5):664–682. doi: 10.1177/1090198106296772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger D, Handley M, Wang F, Hammer H. Effects of self-management support on structure, process, and outcomes among vulnerable patients with diabetes: A three-arm practical clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(4):559–566. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307(15):1583–1584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentell T. Implications for reform: Survey of California adults suggests low health literacy predicts likelihood of being uninsured. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2012;31(5):1039–1048. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Nelson DB, Fink HA, Nichol KL. Health-related quality of life predicts future health care utilization and mortality in veterans with self-reported physician-diagnosed arthritis: The Veterans Arthritis Quality of Life Study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;34(5):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.001. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers BD, Tomasi MR, Swartz K, Epstein AM. Reasons for the wide variation in Medicaid participation rates among states hold lessons for coverage expansion in 2014. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2012;31(5):909–919. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0977. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperl-Hillen J, Beaton S, Fernandes O, Von Worley A, Vazquez-Benitez G, Parker E, Spain CV. Comparative effectiveness of patient education methods for type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(22):2001–2010. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.507. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer AM, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J. Interpersonal Processes of Care survey: Patient-reported measures for diverse groups. Health Services Research. 2007;42(3 Pt 1):1235–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00637.x. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram M, Kavookjian J, Patrick JH, Miller LA, Madhavan SS, Scott VG. Quality of life, health status and clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2007;16(2):165–177. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9105-0. doi:10.1007/s11136-006-9105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: Increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(12):1624–1632. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. Author; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Managed Care Quarterly. 1996;4(2):12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(9):800–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolever RQ, Eisenberg DM. What is health coaching anyway? Standards needed to enable rigorous research: Comment on “evaluation of a behavior support intervention for patients with poorly controlled diabetes”. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(22):2017–2018. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.508. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]