Abstract

Homogentisate solanesyltransferase (HST) plays an important role in plastoquinone (PQ) biosynthesis and acts as the electron acceptor in the carotenoids and abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis pathways. We isolated and identified a T-DNA insertion mutant of the HST gene that displayed the albino and dwarf phenotypes. PCR analyses and functional complementation also confirmed that the mutant phenotypes were caused by disruption of the HST gene. The mutants also had some developmental defects, including trichome development and stomata closure defects. Chloroplast development was also arrested and chlorophyll (Chl) was almost absent. Developmental defects in the chloroplasts were consistent with the SDS-PAGE result and the RNAi transgenic phenotype. Exogenous gibberellin (GA) could partially rescue the dwarf phenotype and the root development defects and exogenous ABA could rescue the stomata closure defects. Further analysis showed that ABA and GA levels were both very low in the pds2-1 mutants, which suggested that biosynthesis inhibition by GAs and ABA contributed to the pds2-1 mutants' phenotypes. An early flowering phenotype was found in pds2-1 mutants, which showed that disruption of the HST gene promoted flowering by partially regulating plant hormones. RNA-sequencing showed that disruption of the HST gene resulted in expression changes to many of the genes involved in flowering time regulation and in the biosynthesis of PQ, Chl, GAs, ABA and carotenoids. These results suggest that HST is essential for chloroplast development, hormone biosynthesis, pigment accumulation and plant development.

Introduction

HST is an important enzyme that catalyzes the condensation of the tyrosine-derived aromatic compound, homogentisate (HGA), with the isoprenoid, all-trans-nonaphenyl diphosphate solanesyl diphosphate, to form 2-Me-6-solanesyl-1,4-benzoquinol (also known as 2-demethylplastoquinol-9) [1]. This branch-point compound directly leads to the biosynthesis of either vitamin E or the photosystem II (PSII) mobile electron transport co-factor, PQ [2], [3]. Indirectly, it also links a number of other diverse, important metabolic pathways, including carotenoid biosynthesis, which uses PQ as a co-factor for phytoene desaturase, and ABA biosynthesis, which is derived from the breakdown of carotenoids [4]–[6]. Consequently, HST is likely to affect plant growth and development. While the homogentisate and solanesyl pathways are critical for forming prenylated electron carrier molecules, such as PQ in chloroplasts and ubiquinone in mitochondria (Figure 1, modified from Motohashi et al.) [7], the C20 diterpene geranylgeranyldiphospate (GGPP) stands at the crux of a number of other biosynthetic pathways important to plant survival and adaptation. GGPP is also used as a substrate in the formation of dolichol (required for protein glycosylation) and phytol side chains during Chl biosynthesis. Changes in fluxes through many of these different pathways could influence other pathways through feedback regulation, changes to higher order regulatory genes and changes to the balance between substrate “draw”, which depends on tissue-specific and organ-specific gene expressions, and expression timing. The feedback regulation balances between substrate “draw” and expression timing are known for GA biosynthesis, the 2-C-methyl-derythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway and for carotenoid biosynthesis [8], [9].

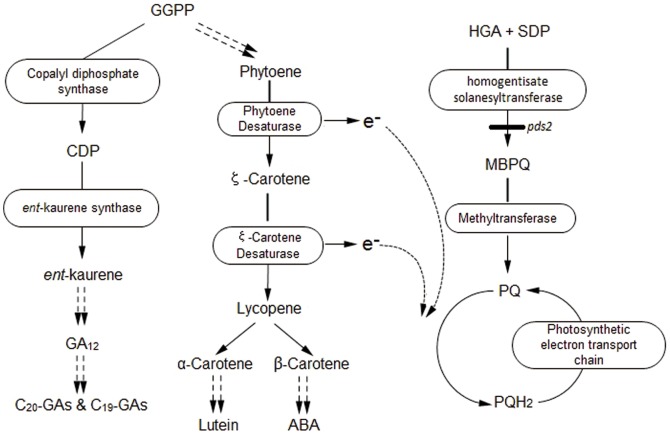

Figure 1. GA, carotenoid, ABA and PQ biosynthesis pathways in plants.

PQ acts as an intermediate electron carrier for phytoene, ζ-carotenoid desaturation enzymes and the photosynthetic electron transport chain. GGPP: geranyl geranyl diphosphate; CDP: copalyl diphosphate; e-: electron; HGA: homogentisic acid; SDP: solanesyl diphosphate; pds2-1: HST mutant; MBPQ: 2-demethyl pastoquinonol; PQH2: plastoquinol.

PQ transports electrons from PSII to cytochrome b6f in the light harvesting reactions of photosynthesis [1], [10] and is the immediate electron acceptor (co-factor) in the -carotene to lycopene stage during carotenoid and ABA biosynthesis and in the desaturation of phytoene and ζ-carotene (Figure 1). A certain quinone/hydroquinone balance is necessary for optimal phytoene desaturation. PQ is enriched in chloroplasts and is also found in Golgi membranes and in minor quantities in microsomes [11]. PQ is not detectable in mitochondria; instead the mobile quinone electron carrier, ubiquinone, dominates in mitochondria. The presence of PQ in the cytosol has also been reported, which probably reflects its transport from the site of synthesis to its final location [11], [12].

In higher plants, GAs can regulate seed germination, stem elongation, leaf expansion, trichome development and plant fertility (stamen elongation, pollen release and germination and pollen tube growth) [8], [13]–[15], GAs are mainly synthesized by the MEP/isoprenoid pathway and this biosynthesis can be divided into three stages [16]–[18]. The GA1 and GA2 genes play an important role in the conversion of GGPP to ent-kaurene and the Arabidopsis ga1 mutant is a GA-responsive male-sterile dwarf due to the disruption of GA biosynthesis. Accumulation of the 1st stage enzyme, cyclase ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase (CPS, also known as GA1), in Escherichia coli, the conversion of GGPP to copalyl diphosphate (CDP) in GA1+/GGPP synthase+ transgenic E. coli and the transgenic complementation of Arabidopsis ga1-3 mutants, confirmed that the GA1 gene locus, U11034, encodes CPS [19]. The Arabidopsis ga2 mutant is also a GA-deficient dwarf because it contains mutated ent-kaurene synthase (KS) and has impaired CDP conversion to ent-kaurene [20].

Genes encoding HST or its homologs have been isolated and identified in Arabidopsis and many other plants [2], [4], [21]–[23]. The HST gene, VTE2, was first isolated from Glycine max and the constitutive expression of VTE2-2 in transgenic Arabidopsis resulted in a significant 13% tocopherol increase compared to the transgenic vector control plants [22]. Previous studies have explored the function of the Arabidopsis HST by utilizing pds2 mutants and transgenic technology [2], [4], [21], [22]. Enzyme assay results for cell expression of the HST gene in E. coli suggested that HST catalyzes the first step in PQ biosynthesis [2]. Overexpression of the HST gene improved prenyl lipid, PQ and tocopherol levels in transgenic Arabidopsis [2], [22]. Disruption of the HST gene produced an albino phenotype and caused a deficiency in the synthesis of PQ and tocopherol by affecting the prenyl/phytyl transferase enzyme [4]. The in-frame 6 bp deletion in the coding region of the HST gene caused an albino phenotype and the expression of the HST gene in this pds2 mutant turned albino plants into green plants [21].

Recently, we screened and found a new recessive albino knockdown mutant called pds2-1. TAIL-PCR and DNA sequencing showed that the mutant phenotype was caused by a T-DNA insertion in the HST gene. To date, phenotypic analysis of HST has been restricted to an albino phenotype, which results from disruption to chloroplast development and photosynthetic pigment biosynthesis. However, in addition to pigment biosynthesis, HST indirectly regulates carotenoid and ABA biosynthesis, but analyses of the developmental and the physiological changes due to HST gene blockage have not been reported. Detailed analysis of pds2-1 indicated that HST knockdown impaired carotenoid and ABA biosynthesis, as well as GA biosynthesis and auxin content, which resulted in severe developmental defects. However, the application of exogenous GA3 and ABA to pds2-1 partially restored the wild-type phenotype. Our new mutant line and analytical data confirm that HST is essential for carotenoid, ABA, and GA biosynthesis and that it plays a critical role in plant growth and development.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia-0) plants were grown in soil or on ½ strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates (pH 5.7) containing 0.8% agar and 3% sucrose at 22°C and 65% humidity under a 16 h light (100 µmol m−2 s−1)/8 h dark cycle. Insertion mutants were obtained from a transgenic experiment via the transformation of Arabidopsis by the floral dip method [24] using Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 that contained pART27 [25]. Self pollinated seed recovered from 16 independent transgenic events was screened on ½ strength MS plates containing 50 mg L−1 of kanamycin. Then the surviving seedlings were transferred to soil to generate seeds at 22°C under long-day conditions. For PCR, RT-PCR, Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), RNA-sequencing and microscope analyses, the seedlings were grown on ½MS plates containing 3% sucrose.

TAIL-PCR

The CTAB method was used to isolate genomic DNA from WT seedlings and heterozygous Arabidopsis. Genomic DNA was used as a template for the TAIL-PCR, which was carried out using a Genome Walking Kit (TAKARA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The three gene-specific primers used in TAIL-PCR were: R1 (5′-GTGCTGCAAGGCGATTAAGTTGGGTAA-3′), R2 (5′-ATTGCGTTGCGCTCACTGCCCGCTTTC-3′) and R3 (5′-GTGGCTCCTTCAATCGTTGCGGTTCTG-3′). The PCR products were sequenced using R3 as the sequencing primer. The sequencing results were searched against the Arabidopsis genome sequence database (GenBank) using BLAST to localize the position of the T-DNA insertion.

Co-segregation Analysis

Three primers were designed and used to analyze the segregation pattern of the T-DNA insertion into the HST gene in seedlings that showed a mutant phenotype. The analysis was performed on DNA extracted from plates of WT and heterozygous mutant seedlings and the primer sequences were: hst-g1 (5′-CGAAAGTAAGCAGAGCAAAGAGT-3′), hst-g2 (5′-CATTCCCACAAATAAGAGCAAGA-3′) and R3 (5′-GTGGCTCCTTCAATCGTTGCGGTTCTG-3′). The PCR products were identified using 1% agar gel electrophoresis.

Cloning of the HST Gene and Binary Vector Construction

Based on the HST cDNA (Accession No.: NM_001161137.1) sequence, a pair of primers: hst-1 (5′-AAACGAAAGTAAGCAGAGCAAAG-3′) and hst-2 (5′-CTAGAGGA- AGGGGAATAACAGATAC-3′), were designed to obtain the DNA sequence that included the coding region of the HST gene. Total RNA isolated from 3-week-old Arabidopsis was used for the reverse transcription-PCR. The PCR product was cloned into the T vector (TAKARA) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The vector containing the HST full-length coding region was used as a template for binary vector construction, together with a pair of primers: HST-f (5′-cccgggccATGGAGCTCTCGATCTCACAATC-3′; where “cccggg” represents a Sma I restriction site and “ccATGG” represents a Nco I site) and HST-r (5′-tctagaactagtTTAGAGGAAGGGGAATAACAGATACT-3′; where “tctaga” represents a Spe I site and “actagt” represents a Xba I site). The PCR product was digested with Nco I and Spe I and cloned into the Nco I-Spe I site of the binary pCAMBIA1302 vector, creating 35Spro::HST, in which the HST gene was expressed from the 35S promoter. The HST antisense plasmid, Anti-HST, was created by placing the Xba I-Sma I fragment of the PCR product between the 35S promoter and the NOS terminator of the binary pBI121 vector in an antisense orientation. The primers used for subcloning the HST gene promoter included Pro-HST-f (5′-atcgatGCAGACAATGTTAATGAAGAAGGCG-3′) and Pro-HST-r (5′-tctagaTTTGTGTCCAATCCTCTTTCCGG-3′). The PCR products were subcloned into the Cla I-Xba I site of pBI121, creating HST pro::GUS, in which the GUS gene is expressed driven by the HST promoter.

Agrobacterium and Plant Transformation

The binary constructs described above were incorporated into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 using the freeze-thaw method [26]. Wild-type Arabidopsis was transformed with Agrobacterium, harboring Anti-HST or HST pro::GUS, using the floral dip method [24]. As homozygous pds2-1 mutant plants could not generate seeds, heterozygous mutant plants (PDS2-1/pds2-1) growing in soil were transformed with Agrobacterium harboring 35Spro::HST. Transgenic plants were selected using 50 mg L−1 kanamycin (Anti-HST or HSTpro::GUS) or 20 mg L−1 hygromycin B (35Spro::HST).

RT-PCR and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

For RT-PCR, WT and albino Arabidopsis plant leaves were harvested after 3 weeks growth on agar medium containing 3% sucrose. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Biomed). The cDNA was synthesized with the reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa) and Oligo d(T) primer, and PCR was performed using the hst-1 and hst-2 primers. UBQ10 (Access No.: NM_116771.5) was used as the inner control gene along with two primers: UBQ-f (5′-GCCGGAAAACAATTGGAGGATGGT-3′) and UBQ-r (5′-CATTAGAAAGAAAGAGATAACAGG-3′). RT-PCR images were captured using a Gel Image Analysis System.

qRT-PCR analysis was used for the expression analyses and was performed on 7-week-old WT plants at different developmental stages and on a variety of tissues. It was also performed on 7-week-old WT or pds2-1 mutant plants for gene expression analyses. The system used was an ABI 7500 system with SYBR green detection. For analyses of HST expression in different tissues and developmental stages of WT Arabidopsis, UBQ10 was used as an internal control. For analyses of gene expression in pds2-1 mutants, TUB2 was used as an internal control. The two-step thermal cycling profile used was 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 68°C. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed in biological triplicates using total RNA samples extracted from three independent plant materials grown under identical growth conditions. The comparative ΔΔthreshold cycle method [27] was used to evaluate the relative quantities of each amplified product in the samples. All primers used in the qRT-PCR analyses are reported in Supplementary Table S1.

RNA Sequencing

The whole plants of 3-week-old pds2-1 and WT Arabidopsis were harvested and used for RNA extraction. The experiment was then repeated following the same collection scheme, thus providing two distinct biological replicates. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer's instructions and was treated with RNase-free DNase I (NEB) to remove contaminated genomic DNA. The mRNA was isolated from the total RNA using Dynabeads oligo(dT) (Invitrogen). An illumina library was constructed using the NEB mRNA library prep kit instruction manual. The cDNA library was sequenced for paired ends on the Illumina Hiseq2000 platform at the Beijing Center for Physical and Chemical Analysis (Beijing, China). The raw reads were filtered by removing adaptor sequences, empty reads and low quality reads containing more than 50% bases with Q<30 using FASTX-Toolkit with methods described previously [28]–[30]. The resulting high-quality reads were mapped onto the Arabidopsis thaliana reference genome (TAIR 10) using Tophat (v2.0.5) [31]. Gene expression levels were measured as FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads). EdgeR outputs the T-statistic and the p-values for each gene. Differential expression was estimated and tested using the edgeR software package (R version: 2.14, edgeR version: 2.3.52) [32]. We then calculated the FDR, estimated fold change (FC) and the FC log2 values. Transcripts that had an FDR≤0.05 and an estimated absolute log2 (FC)≥1 were determined to be significantly differentially expressed. Gene Ontology (GO), SEA and PAGE tools, found at the agriGO website (http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/), were used to analyze the differential expression genes during the functional annotation and enrichment analysis.

Chl and Carotenoid Assays

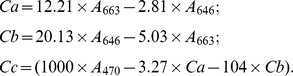

Chl and carotenoids were extracted from the aboveground parts of 40-day-old Arabidopsis, as described previously [33]. Absorbance (A) of the final solution at 663, 647 and 470 nm was measured and the concentrations of Chl a (Ca), Chl b (Cb) and carotenoids (Cc) were calculated as follows [34]:

|

ELISA Analyses

Initially, four plant hormones: ABA, GA3, IAA and ZR, were measured on the aerial parts of 3-week-old WT and pds2-1 plants by a previously described ELISA method [35].

β-Glucuronidase Staining

Histochemical β-Glucuronidase staining in HST pro::GUS transgenic plants was performed as described previously [36].

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM) Assays

Leaves harvested from 3-week-old WT and pds2-1 plants were soaked in fixation buffer (4% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2) and post-fixed for 6 h in secondary fixation buffer (1% OsO4 in 100 mM cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) at 4°C. The fixed samples were dehydrated, embedded in Spurr resin and cut into ultrathin sections. The specimens were subsequently stained with uranyl acetate and observed with a TEM (Hitachi).

For SEM analysis, leaves of 3-week-old WT and pds2-1 plants were harvested and the analysis was performed as described previously [37]. The specimens were examined by a SEM (Hitachi).

Results

Phenotype Analysis of the Albino Mutant

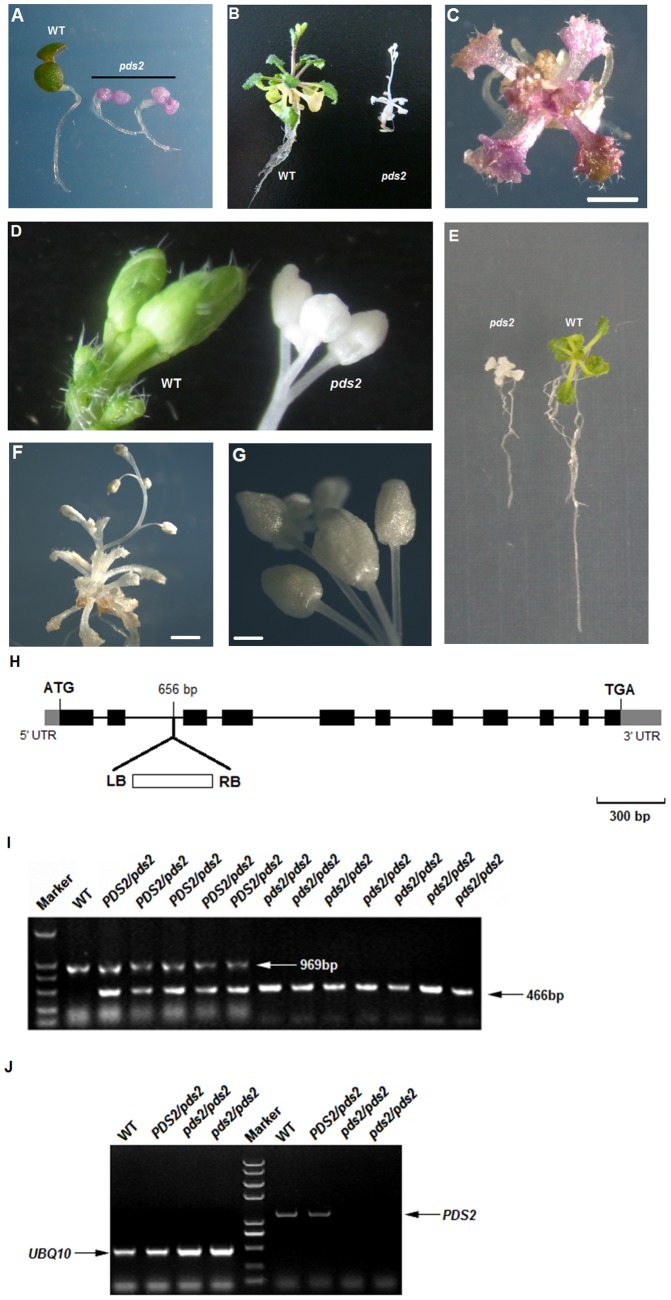

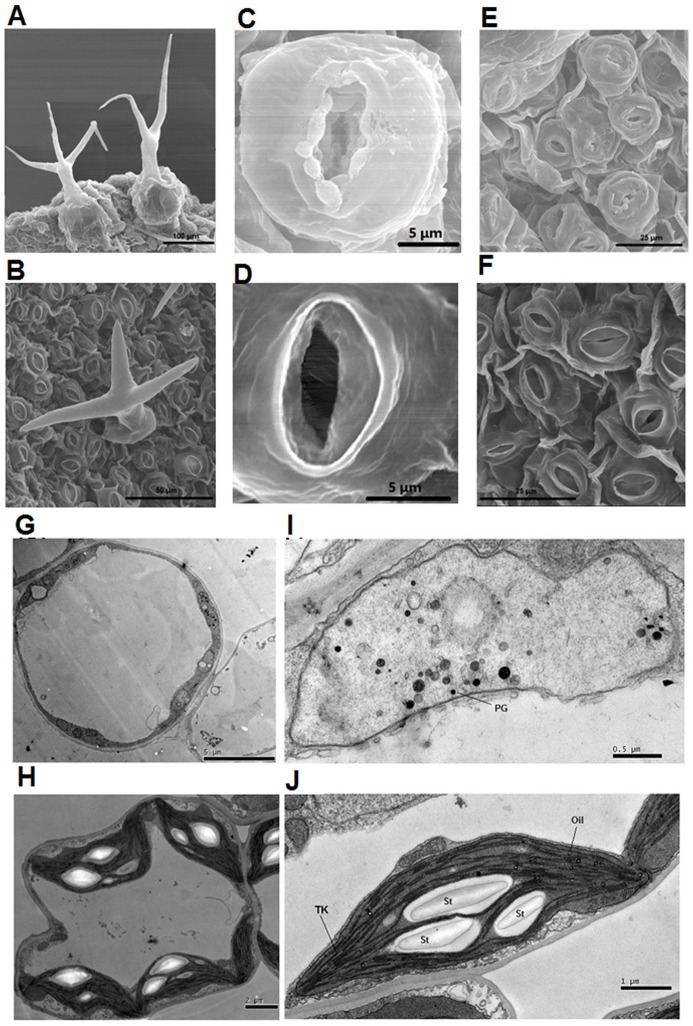

Arabidopsis thaliana was transformed by the binary vector, pART27, so that a small number (16) of T-DNA insertion lines could be generated. Seedlings from self-pollinated plants, selected on ½-strength Murashige and Skoog plates containing kanamycin and sucrose, were mainly green, but one plate contained several albino plants. Progeny from heterozygous albino plants were mainly green, but progeny derived from self-pollinated heterozygotes segregated 3∶1 into green and albino colored siliques (Figure S1). The cotyledons of all the young homozygous progeny from the albino type plants were purple on the selection medium (Figure 2 A), which suggested that Chl may be low or absent and that anthocyanin pigments may have accumulated. Most homozygous albino mutants gradually faded to white with continued growth on the selection medium. A small number of plants also showed the purple coloration on the rest of their plant parts (Figure 2 A–C). All albino seedlings died when they were grown on soil or ½ strength MS medium without sucrose, but in ½ MS medium with 3% sucrose, albino seedlings produced albino leaves (and even translucent stem tissues) and only one main shoot over their whole life cycle (Figure 2 B,E,F). Low resolution microscopy indicated that the albino plants had shorter roots, fewer root hairs, fewer and smaller leaves with shorter petioles and a reduced trichome density (Figure 2 B–F; Figure S2; Figure S3). Microscope or SEM was used to investigate the leaf surface morphology (trichomes and stomata) of pds2-1 and WT plants in greater detail. The results showed that pds2-1 trichomes were shorter in length and most (∼80%) trichomes had two branches instead of three (Figure 3 A,B; Figure S3; Figure S4). Their stomata had larger openings with unusual swollen structures surrounding the opening (Figure 3 C–F), which suggested that pds2-1 stomata may close abnormally.

Figure 2. Analysis of pds2-1 mutant plants.

(A) WT and homozygous pds2-1 (T3) seedlings with purple cotyledons grown on ½ strength MS medium for 4 days. (B) Adult homozygous pds2-1 mutant (T3) and WT plants grown on ½-strength MS medium for 4 weeks. (C) A purple T3 pds2-1 mutant seedling. Scale bar = 1 mm. (D) Inflorescences and flower buds from 8-week-old WT and pds2-1 plants. (E) Roots from pds2-1 and WT plants. (F) Adult pds2-1 plant grown on ½ strength MS medium for 8 weeks. Scale bar = 2 mm. (G) Adult inflorescence of a pds2-1 mutant plant. Scale bar = 0.5 mm. (H) HST gene structure and the T-DNA insertion site in pds2-1 mutants. Black boxes: HST gene exons; black lines: HST gene introns. (I) Co-segregation analyses of the HST transgene with pds2-1 mutant phenotypes. Marker: DNA marker; PDS2/pds2: heterozygous pds2-1 mutants; pds2/pds2: homozygous pds2-1 mutants. (J) RT-PCR analysis of the HST gene in WT and pds2-1 mutant plants. The UBQ10 gene was used as an internal control.

Figure 3. SEM and TEM of mesophyll cells and leaf surfaces of pds2-1 mutant plants.

(A) SEM analysis of trichomes from pds2-1. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) SEM analysis of the trichomes from a WT plant. Scale bar = 50 µm. (C,D) SEM analysis of stomata from a pds2-1 plant (C) and a WT plant (D). Scale bars = 5 µm. (E,F) SEM leaf surface analysis of a pds2-1 plant (E) and a WT plant (F). Scale bars = 25 µm. (G) TEM analysis of a mesophyll cell from a pds2-1 plant. Scale bar = 5 µm. (H) TEM analysis of a mesophyll cell from a WT plant. Scale bar = 2 µm. (I) TEM analysis of chloroplasts from a pds2-1 plant. PG: plastoglobule. Scale bar = 0.5 µm. (J) TEM analysis of chloroplasts from a WT plant. St: starch granule; Tk: thylakoid; Oil: oil drops. Scale bar = 1 µm.

Albino and Dwarf Phenotypes are Caused by a T-DNA Insertion into HST

We hypothesized that the albino pds2-1 phenotype was caused by a T-DNA insertion because the albino plants were obtained from transgenic Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines and the green and albino plants of T1, T2 and T3 segregated in a 3∶1 ratio on nonselective medium. To determine the insertion site within the Arabidopsis genome, DNA was isolated from T3 heterozygous plants and non-transformed WT plants (as a negative control) for the TAIL-PCR (Figure S5). The TAIL-PCR and sequencing showed that the insertion was located at Chr3:3782298, which is within the second intron of the Arabidopsis HST gene (At3g11945) (Figure 2 H).

To check whether the T-DNA insertion was responsible for the albino phenotype, DNA was isolated from WT, heterozygous (green) and homozygous (white) Arabidopsis plants for PCR analysis. Primers, hst-g1 and hst-g2 (Table S1) amplified a full-length 969 bp fragment of HST gDNA from the WT and heterozygous plants. In contrast, primers R3 and hst-g2 amplified a 466 bp fragment from the heterozygous and homozygous pds2-1 plants. These results indicated that the T-DNA insertion in the HST gene co-segregated with the albino phenotype (Figure 2J). To analyze the transcription of HST in the heterozygous and homozygous pds2-1 plants, RT-PCR was conducted using gene specific primers: hst-1 and hst-2. The results showed that HST expression was eliminated in the homozygous plants (Figure 2 J), which suggested that albino plants were HST null mutants and that the mutant phenotype was caused by a T-DNA insertion into the HST gene.

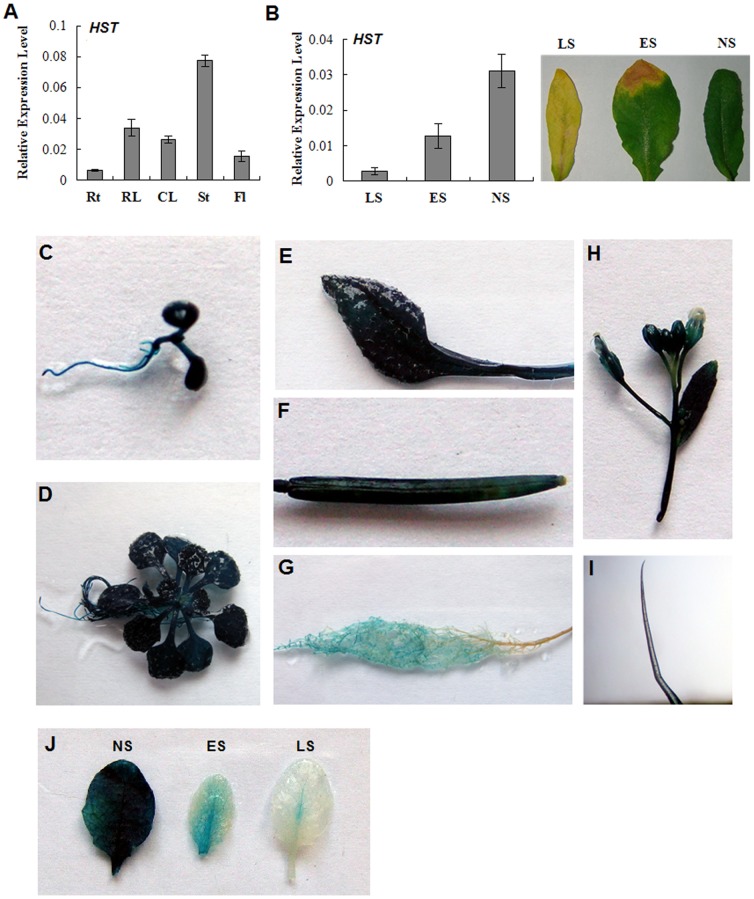

The HST Gene is Highly Expressed in Green Tissues

To understand the breadth of the role played by the HST gene, we re-examined the expression pattern of HST in WT Arabidopsis using qRT-PCR. The qRT-PCR assays revealed that HST was expressed at high levels in stems and leaves, but at relatively lower levels in the flowers and roots of adult plants (Figure 4 A). Furthermore, different HST expression levels were detected in the leaves at different developmental stages. The HST transcript levels were highest in non-senescent leaves, but they gradually decreased as the leaves began to senesce (Figure 4 B).

Figure 4. Expression analysis of the HST gene in WT Arabidopsis.

(A) Tissue-specific expression as determined by qRT-PCR. The UBQ10 gene was used as an internal control. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). Rt: roots; RL: rosette leaves; CL: cauline leaves; St: stems; Fl, flowers. (B) HST transcript levels at different leaf development stages. NS: no senescence; ES: early senescence; LS: late senescence. (C–J) Representative GUS expressions in HSTpro::GUS transgenic Arabidopsis. (C) 5-day-old etiolated seedling; (D) 15-day-old seedling; (E) mature leaf of a 4-week-old plant; (F) mature silique; (G) root; (H) inflorescence and flowers; (I) trichome from a stem; (J) leaves at different developmental stages.

To further examine the HST expression patterns in different plant tissues, a 813 bp HST promoter sequence, upstream of the transcription start site, was fused to a GUS-coding sequence and this led to the appearance of HSTpro::GUS transgenic Arabidopsis plants. In 40-day-old seedlings, GUS activity was highly detected in green tissues, such as leaves and stems (Figure 4 C–J). Notably, GUS activity was detected at a high level in adult green leaves, but at decreased levels in senescent leaves (Figure 4 J). These results suggested that HST was highly expressed in green tissues and had an important role to play in their development.

HST is Required for Pigment Accumulation, Proplastid Growth and Thylakoid Membrane Formation

Total Chl and carotenoid (Car) contents were examined in pds2-1 and WT plants. The calculated results showed that Chl and Car were almost absent in the homozygous pds2-1 mutant plants. Chl a decreased to 0.55% of the WT level, Chl b to 1.86% and total Chl to 0.93% (Table 1), while carotenoids were reduced to 0.24% of the WT level. The Chl a/b ratio also decreased dramatically in pds2-1 mutants and was only 26.90% of the WT level. As a result, the Chl/Car ratio increased to 20.79 in the pds2-1 mutants (Table 1). These results showed that disruption of the HST gene caused significant reductions in Chl and carotenoid levels and that carotenoids were affected more seriously than Chl in pds2-1 mutants.

Table 1. Chl and carotenoids contents of WT and pds2-1 mutant plants.

| Arabidopsis | Chl a (mg L−1) | Chl b (mg L−1) | Car (mg L−1) | Chl (mg L−1) | Chl a/b | Chl/Car |

| WT | 19.03±4.60 | 8.01±1.86 | 5.17±0.82 | 27.04±2.76 | 2.60±0.93 | 5.29±0.38 |

| pds2-1 | 0.10±0.01** | 0.15±0.01** | 0.01±0.00** | 0.25±0.01** | 0.70±0.03** | 20.79±3.25** |

Leaves from 40-day-old plants were sampled to determine the Chl and carotenoid contents.

** indicates significant differences of the means at P<0.01 between WT plants and pds2-1 mutant plants for each parameter measured (n = 4).

To assess the effect of pds2-1 mutations on chloroplast development, plastids from the first leaves of 30-day-old seedlings were examined by TEM. The data showed that the chloroplasts in pds2-1 were smaller than those in the wild type and lacked starch granules, oil drops and thylakoids, but contained many densely stained globule structures that resembled plastoglobules (Figure 3 G–J). These results suggested that proplastids in the mesophyll cells of the pds2-1 mutant have lost the ability to develop into mature chloroplasts. The RuBisCO large subunit levels were also highly reduced in pds2-1 when total protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Figure S6) and this was consistent with the albino phenotype and the chloroplast development defects in pds2-1. These data suggested that HST played an important role in pro-plastid growth and thylakoid membrane formation.

An anti-sense HST-RNAi vector was used to transform Arabidopsis WT plants and six transgenic Arabidopsis lines were analyzed for phenotype and chloroplast defects (Figure S7 A). Leaves from one adult RNAi transgenic line (Anti-HST) were a lighter green color than the WT plant leaves. The HST transcripts were significantly down-regulated in this line compared to the WT plants and the darker green RNAi lines (Figure S7 B,C). The levels of Chl a and b were also significantly lower in Anti-HST plants compared to the WT lines (Figure S7 D).

The HST Gene Rescues the pds2-1 Mutant Phenotype

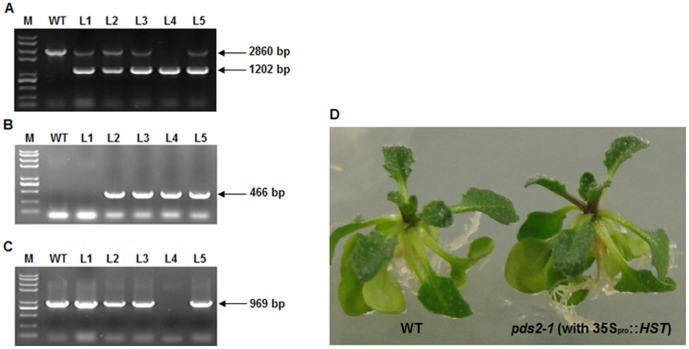

HST cDNA, driven by the 35S promoter, was inserted into the genome of the pds2-1 heterozygous mutant. Transgenic seeds were screened on ½MS plates containing 3% sucrose and 20 mg L−1 hygromycin and six independent lines were selected. Homozygous pds2-1 plants with 35Spro::HST were confirmed by PCR (Figure 5 A–C). T2 progeny of pds2-1 that were homozygous for 35Spro::HST displayed a phenotype that was similar to the WT plants (Figure 5 D). These results showed that the HST gene driven by the 35S promoter could completely rescue the mutant phenotype.

Figure 5. HST gene rescues the phenotype of pds2-1 mutant plants.

(A) PCR analysis of transgenic Arabidopsis using the HST-f and HST-r primers. The 2,860 bp band represents HST gDNA and the 1,202 bp band represents the HST coding domain sequence in transgenic Arabidopsis. M: DNA marker; WT: wild type; L1-5: five independent plants transformed with 35Spro::HST. (B) PCR analysis of transgenic Arabidopsis using the R3 and hst-g2 primers. The 466 bp band represents the T-DNA insertion in the HST gene. (C) PCR analysis of transgenic Arabidopsis using the hst-g1 and hst-g2 primers. Absence of the 969 bp band shows that L4 is a pds2-1 homozygous mutant. (D) Representative phenotype of pds2-1 homozygous plants rescued by transforming them with 35Spro::HST.

Severe Declines in GA and ABA Content Were Seen in pds2-1 Leaves

ELISA were performed to determine the concentrations of ABA, GA3, zeatin riboside (ZR) and IAA in the aerial parts of 3-week-old WT and pds2-1 plants. A substantial decrease in ABA (43.1%), GA3 (61.5%) and ZR (69.8%) concentrations occurred in pds2-1 plants compared to WT plants (Table 2) but the ratio of GA3:ABA was increased from 0.0621 in WT to 0.0923 in pds2-1 (Table 2). This disruption of the HST gene also led to a substantial increase (by 41.6%) in the IAA content of pds2-1.

Table 2. Plant hormone concentrations in pds2-1 and WT seedlings grown on ½ MS plates.

| Plant hormone | WT (ng·g−1·FW) | pds2-1 (ng·g−1·FW) | pds2-1:WT | P-value |

| ABA | 138.38±2.95 | 59.58±2.68 | 0.431 | <0.0001 |

| GA3 | 8.95±0.24 | 5.5±0.15 | 0.615 | <0.0001 |

| ZR | 15.94±0.56 | 11.12±0.43 | 0.698 | <0.0001 |

| IAA | 56.49±2.14 | 79.98±2.18 | 1.416 | 0.0002 |

Three-week-old seedlings were sampled to determine the levels of four plant hormones. P-values represent significant differences of the means between WT and pds2-1 tissues (n = 3) after comparing them using Student's t-test. FW: fresh weight.

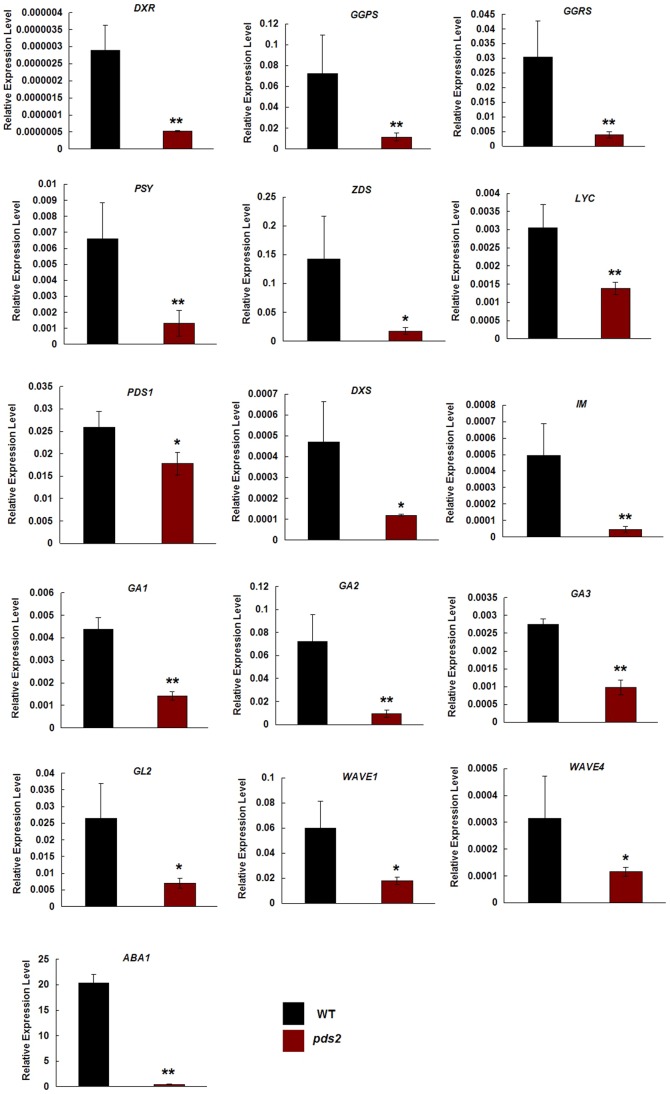

Gene Transcriptions That Specified Carotenoids, GA, ABA, Trichomes and Roots Were Depressed in pds2-1

Previous reports indicated that albino mutants blocked the MEP pathway and led to a decrease in carotenoid, GA and ABA biosynthesis [33]. Therefore, we investigated whether disruption of the HST gene changed the expression of genes involved in these pathways using qRT-PCR. DXS, DXR, LYC, IM, PSY and ZDS are involved in the MEP pathway and in the biosynthesis of carotenoids [38]–[40]. GGPS encodes an enzyme involved in isoprenoid biosynthesis [41] and GGRS encodes a protein with geranylgeranyl reductase activity [42]. The PDS1 gene (encoding the p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate) plays an important role in the synthesis of both plastoquinone and tocopherols in plants [43], GA1, GA2 and GA3 are involved in GA biosynthesis [19], [20], [44]; ABA1 plays an important role in ABA accumulation [45] and GL2, WAVE1 and WAVE2 are involved in trichome and root hair initiation [46]. The results showed that transcription of all these selected genes was significantly lower in pds2-1 plants compared to WT plants and the key gene in ABA biosynthesis, ABA1, was almost absent in the pds2-1 plants (Figure 6).

Figure 6. qRT-PCR analyses of genes involved in the carotenoid, GA and ABA biosynthetic pathways and in the regulation of trichome and root hair development.

Significant differences of the means (± SD) between WT plants and pds2-1 plants (n = 3) are indicated by * (P<0.05) and ** (P<0.01). The Arabidopsis TUB2 gene was used as an internal control.

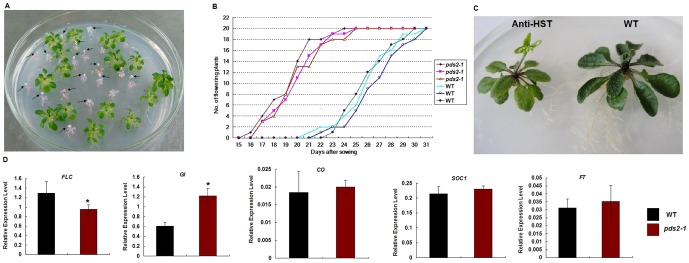

A Mutation in HST Promotes Early Flowering in pds2-1

Although the growth of homozygous mutants was severely retarded, the pds2-1 albino plants could bolt when grown on ½MS containing 3% sucrose (Figure 7 A). All the homozygous plants had flower-like structures that never matured into normal flowers (Figure 7 A,B) and the flowers and stems were usually glabrous (Figure 2 D). Therefore, psd2-1 had to be propagated in the heterozygous state, which suggested that the gene was essential for plant development. Moreover, flowering time was disrupted in pds2-1 plants and they flowered earlier than the WT plants (Figure 7 A,C). This conclusion is supported by the light green-colored anti-sense HST-RNAi line, anti-L2, which also displayed an early flowering phenotype (Figure 7 D). Transcripts for two flowering genes, FLC and GI, were also significantly depressed in pds2-1 plants, but CO, SOC1 and FT were unaffected by the mutation (Figure 7 E).

Figure 7. Reduced expression of HST results in an early flowering phenotype.

(A) Typical 22-day-old pds2-1 and WT seedlings. Black arrows indicate floral structures on bolting pds2-1 plants. (B) Onset of early flowering in three pds2-1 plants compared with WT plants. (C) Anti-HST early flowering phenotype. (D) Expression analysis by qRT-PCR of genes involved in regulating flowering time in pds2-1 plants. Significant differences of the means (± SD) between WT plants and pds2-1 plants (n = 3) are indicated by * (P≤0.05). The Arabidopsis TUB2 gene was used as an internal control. FLC: Flowering Locus C; GI: Gigantea; CO: Constans; SOC1: Supressor of Overexpression of Constance1.

HST Disruption Affects the Expression of Many Photosynthetic Genes, Cellular Components and Biological Processes

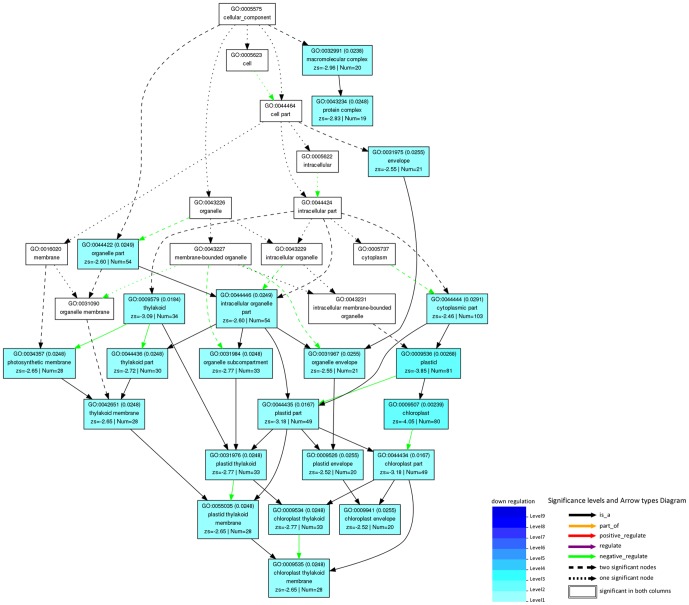

RNA sequencing was carried out to further explore the effects of the HST gene on metabolic pathways. A total of 1254 unique genes exhibited two fold or greater differential expression in pds2-1 plants compared to WT plants, with 351 genes up-regulated and 903 genes down-regulated. A total of 222 differentially expressed genes were then identified with a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05 (Table S2). Gene Ontology (GO) was used to analyze the differentially expressed genes by functional annotation and enrichment analysis, which required the use of singular enrichment analysis (SEA) and the Parametric Analysis of Gene set Enrichment tool (PAGE) [47]. In total, 212 of the 222 differentially expressed genes were assigned to at least one term in GO under the different biological process categories (molecular function, subcellular structure/components and biological process) and the number of significant GO terms were 138. In pds2-1 mutants, the expression levels of many genes related to cellular structure/components, including thylakoids, plastids, chloroplasts, photosynthetic membrane, plastoquinone, plastoglobules, light-harvesting complexes, organelles, the cytoplasm and the apoplast, were dramatically reduced (Table S3). Moreover, the expression levels of molecular components involved in photosynthesis, the light reaction, pigment metabolic processes and processes such as the regulation of catalytic activity, response to stimuli, and response to stress, had also decreased significantly. When differentially expressed genes involved in cellular components were submitted to the PAGE tool after RNA sequencing, 22 GO terms (including thylakoid, chloroplast, photosynthetic membrane, etc.) were significantly over-represented in the hierarchical tree (Figure 8; Table S4).

Figure 8. Hierarchical tree of over-represented GO terms (subcellular structure category) generated by parametric analysis of gene set enrichment.

Boxes in the graph represent GO terms as labeled by their GO ID, term definition and statistical information. Significantly over-represented terms (adjusted P<0.05) are marked with color, while non-significant terms are shown as white boxes. A box's degree of color saturation is correlated to the representation level of the term. Boxes connected by dotted, dashed and solid lines represent zero, one and two down-regulation terms at the ends connected by the line, respectively.

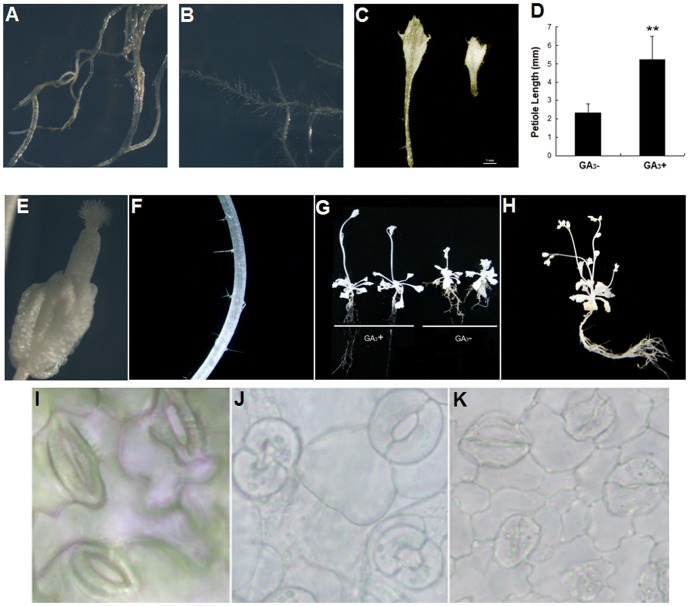

GA3 and ABA partially rescued the pds2-1 mutant phenotype

The 14-day-old pds2-1 seedlings were transferred onto ½MS medium containing 3% sucrose and 10 µM GA3. Two weeks later, the leaf petioles and roots of all the tested pds2-1 plants were longer than those grown without GA3 and root hair density had increased (Figure 9 A–D, G). The pistils of pds2-1 mutants grew longer with GA3 supplementation, but flower buds did not develop into mature flowers (Figure 9 E). Stem trichomes were obvious on pds2-1 mutant plants when treated with GA3 (Figure 9 F). The pds2-1 plants treated with GA3 also had extended petioles, were larger and grew faster than those without GA3 and they produced more branches and inflorescences (Figure 9 G,H).

Figure 9. Exogenous application of GA3 or ABA to pds2-1 mutants.

(A) Root hair of a pds2-1 mutant plant after 10 µM GA3 treatment. Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Root hair of a pds2-1 mutant plant without GA3 treatment. Scale bar = 1 mm. (C) Representative petiole lengths from pds2-1 mutants with exogenously applied GA3 (GA3+) or without GA3 (GA3−). Scale bar = 1 mm. (D) Petiole length analyses of pds2-1 plants with or without GA3 treatment. A total of 30 leaves (from 10 plants) were measured for each sample. ** indicates significantly different means (± SD) at P<0.01 compared to those without GA3 treatment. (E) The longer flower bud pistil seen on pds2-1 mutant plants after GA3 treatment. Scale bar = 0.5 mm. (F) Trichomes (arrows) on a pds2-1 mutant stem after GA3 treatment. (G) Sizes of bolting pds2-1 mutant plants grown on ½ strength MS medium with or without GA3 treatment. (H) Mature pds2-1 mutant plant showing multiple flowing shoots after GA3 treatment. (I) Usual stomata structure of a WT plant without ABA treatment. Scale bar = 5 µm. (J) Swollen open stomata structure of a pds2-1 mutant without ABA treatment. Scale bar = 5 µm. (K) Closed stomata structure of a pds2-1 mutant after 10 µM ABA treatment. Scale bar = 5 µm.

ABA plays an important role in regulating stomata closure in plants. To find out whether the stomata structural defect in pds2-1 plants was caused by ABA absence, 14-day-old pds2-1 seedlings were transferred onto ½ MS medium supplemented with ABA. Two days later, the leaves of the mutant plants were harvested and the stomata structure observed using light microscopy. The stomata closed normally in pds2-1 mutants with exogenous ABA (Figure 9 J–K), which suggested that the stomata closure defect was caused by an ABA deficiency in pds2-1 mutants.

Discussion

In this study, we identified an albino mutant, pds2-1, and showed that disruption to the HST gene resulted in an albino phenotype and developmental defects. Homozygous pds2-1 mutants all died when they were grown on soil or ½MS medium without sucrose, but produced albino leaves or white inflorescences when 3% sucrose was included. Other Arabidopsis mutants exhibited a similar albino phenotype when DXR, PDS or the IspH homologue of an isoprene biosynthetic gene were disrupted [9], [33], [48], [49].

RT-PCR and GUS staining showed that HST was expressed in almost all the plant tissues and at higher levels in green tissues. HST protein contains a putative 69 aa chloroplast transit peptide at its N-terminus. Subcellular localization analysis of HST in a previous report showed that HST was targeted at chloroplasts [21]. In this study, TEM analysis demonstrated that pds2-1 chloroplasts were smaller and developmentally malformed. Our study confirmed previous reports, which showed that HST disruption resulted in an albino phenotype in Arabidopsis [4], [21]. We measured Chl levels to confirm the negative effect of a mutated HST gene on the photosystem and found that the pds2-1 mutant had significantly reduced Chl levels, which was consistent with the reduced expression we measured for key genes involved in chloroplast biosynthesis. Moreover, SDS-PAGE analysis of the total proteins in pds2-1 plants also confirmed that the photosystem was destroyed and that RuBisCo was not produced after HST disruption. Transgenic mutants transformed with 35Spro::HST restored the normal green phenotype, but RNAi lines had yellowish-green leaves. Together, these results confirmed that HST was essential for normal plant growth and chloroplast development.

Carotenoids play important roles in many physiological processes and in chloroplast biogenesis. They are also precursors of ABA. Biochemical analysis of the pds2-1 mutant plants revealed that carotenoids, ABA and PQ levels were dramatically reduced in plant leaves. HST is a critical enzyme in the PQ biosynthesis pathway. PQ is both a PSII electron carrier and a critical component that links carotenoid and ABA biosynthesis [4]–[6] with PS I, PS II and ATP synthesis [50]. Hence, the absence of PQ in pds2-1 caused disruption to electron transport, which may have contributed indirectly to the developmental defects in chloroplasts via negative feedback during phytoene desaturation, carotenoid synthesis and chloroplast biogenesis. Inhibition of PQ biosynthesis, leading to phytoene accumulation, has also been reported in previously identified pds2 mutants [4]. Our pds2-1 mutant plants also displayed stomata closure defects and an application of exogenous ABA restored the wild type plant stomata. These results suggested that HST also had an indirect impact on stomata closure by affecting carotenoid and ABA biosynthesis through the regulation of PQ levels.

The pds2-1 mutants showed a pronounced dwarf phenotype and trichome and root hair development defects. qRT-PCR analyses showed that three positive regulators (GL2, WAVE1 and WAVE4) of trichome or root hair development were down-regulated in pds2-1 mutants. ELISA analyses and qRT-PCR revealed that GA levels and the expression of GA biosynthesis genes, such as GA1, GA2 and GA3, declined dramatically in pds2-1 mutants. When exogenous of GA3 was added to the ½MS plates, the pds2-1 plants grew larger and had more root hairs and branches. GAs play important roles in plant height, trichome initiation and root development [51]–[56]. In plastids, GGPP is a precursor of carotenoids, ABA, tocopherols, the phytol tail of Chl, plastoquinones and GA. Qin et al. (2007) showed that disruption of the phytoene desaturase gene, PDS3, in carotenoid biosynthesis impeded the biosynthesis of GAs [9] and a negative feedback mechanism controlled upstream genes in the pds3 carotenoid mutant, which resulted in a decrease in GAs. Our novel GA findings, together with supporting literature and the other information, strongly suggest that HST disruption in pds2-1 affects many pathways through direct and indirect mechanisms.

GAs play an important role in the positive regulation of flowering time [57], [58] and reduced gibberellin synthesis usually promotes late flowering phenotypes in Arabidopsis [59], [60]. Hence, pds2-1 mutants should, in principle, exhibit late flowering because of the decrease in GA3. Instead, an unusually early flowering phenotype occurred in pds2-1 and in the anti-HST plant. This early flowering phenotype was consistent with the decrease in the expression of a key flowering repressor, FLC, and an increase in the expression of the flowering regulator, GI, in pds2-1 mutants. One interpretation of this data arises from the fact that ABA and GA levels decreased in pds2-1 mutants. ABA is believed to act as an antagonist to GAs during plant growth and development [61], [62]. ABA biosynthesis mutants have an early flowering phenotype [61], [63] and ABA can delay flowering onset by up-regulating the expression of FLC, as occurs in Arabidopsis [64]. In fact, although the levels of both hormones fell in pds2-1 seedlings, the overall ratio of GAs∶ABA increased by 48.6% (Table 2). Genetic analyses of the interaction between GAs and ABA shows that GAs play a major rate-limiting role in floral promotion [61]. Our findings, together with an earlier report, suggested that the increased ratio of GA∶ABA in pds2-1 mutants had maintained the predominant role played by GA and caused the triggering of the early transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. A second interpretation is that HST disruption affected other hormone levels. Earlier reports showed that a number of hormones, including GAs, ABA and auxins, played important roles in regulating flowering time [65]. For example, exogenous IAA was able to induce flowering in long day plants [66]. Our ELISA results showed that auxin levels (IAA) increased by 41.6% in the pds2-1 mutant compared to the WT plants. Hence, the early flowering phenotype displayed by pds2-1 mutant plants could also be due to their increased IAA levels. In summary, disruption of the HST gene promoted flowering by affecting the levels of several plant hormones.

Screening of a small Arabidopsis T-DNA population uncovered a novel albino mutant pds2-1 with a T-DNA insertion in the HST gene. This gene is known to play an important role in PQ biosynthesis. The pds2-1 mutation resulted in a typical carotenoid-deficient phenotype, with reduced PQ, abnormal chloroplast development, reduced photo-protection and reduced PS II activity. These findings confirmed that the HST gene plays an important role in pro-plastid growth and thylakoid membrane formation. However, the mutation also produced novel IAA-enhanced, ABA-deficient and GA-deficient phenotypes that had not been reported previously. Furthermore, GA3 and ABA application partially rescued the mutant phenotype. Other novel phenotypes not previously reported for this gene include short roots and petioles, fewer leaf numbers, root hairs and trichomes, more swollen stomata, an early flowering date and high expression of HST gene in green tissues. Moreover, qRT-PCR and RNA sequencing confirmed that the mutant had a blocked MEP pathway and the genes that played a role in GA biosynthesis did not function. This detailed analysis of the pds2-1 mutant paves the way for a comprehensive study of the physiological regulation of carotenoids, chloroplast components and other physiological processes by major plant hormones through the use of a combination of genetic, biochemical and molecular approaches. HST will probably lie at the heart of these processes as it appears to impact directly and indirectly on so many hormones and biological processes.

Supporting Information

Seed segregation in a silique from a heterozygous pds2-1 mutant plant.

(TIF)

Microscopic analysis of root hair from the pds2-1 mutant and WT Arabidopsis.

(TIF)

Trichome phenotype of leaves from pds2-1 and WT Arabidopsis.

(TIF)

Microscopic and statistical analyses of stomata from the pds2-1 mutant and WT Arabidopsis.

(TIF)

Representative TAIL-PCR analysis of heterozygous ( PDS2 / pds2 ) plants.

(TIF)

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showing loss of a major protein subunit (RuBisCo) in pds2-1 .

(TIF)

Gene expression and pigments in HST RNAi transgenic lines.

(TIF)

Primers used in RT-qPCT analyses.

(DOC)

Significant differential expression genes in WT and pds2-1 .

(DOC)

GO terms in all three categories (Biological Process, Cellular Component and Mollecular Function) generated by SEA.

(DOC)

GO terms in Sub-Cellular Structure/Components generated by PAGE.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Andrew Gleave, from The New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research Limited, for providing the pART27 vector sequence information required to determine T-DNA insertion loci. We thank CSIRO Plant Industry (Australia) for giving us the vector pART27. We thank Mr. Zhaofeng Huang from The Institute of Plant Protection, CAAS, for providing access to the ABI 7500 qRT-PCR apparatus. We also thank Professor. Baomin Wang from the Chinese Agricultural University for conducting the ELISA assays for ABA, GA3, IAA and ZR.

Funding Statement

This program was supported by a National Science and Technology Supporting Project of China (No. 2011BAD17B01-01-3) and a grant from The China Agriculture Research System (CARS-35-04). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Sadre R, Frentzen M, Saeed M, Hawkes T (2010) Catalytic reactions of the homogentisate prenyl transferase involved in plastoquinone-9 biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 285: 18191–18198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sadre R, Gruber J, Frentzen M (2006) Characterization of homogentisate prenyltransferases involved in plastoquinone-9 and tocochromanol biosynthesis. FEBS letters 580: 5357–5362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang W, Cahoon RE, Hunter SC, Zhang C, Han J, et al. (2011) Vitamin E biosynthesis: functional characterization of the monocot homogentisate geranylgeranyl transferase. The Plant journal 65: 206–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Norris SR, Barrette TR, DellaPenna D (1995) Genetic dissection of carotenoid synthesis in arabidopsis defines plastoquinone as an essential component of phytoene desaturation. The Plant cell 7: 2139–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nievelstein V, Vandekerckhove J, Tadros MH, Lintig JV, Nitschke W, et al. (1995) Carotene Desaturation is Linked to a Respiratory Redox Pathway in Narcissus Pseudonarcissus Chromoplast Membranes. European Journal of Biochemistry 233: 864–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rock CD, Zeevaart J (1991) The aba mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana is impaired in epoxy-carotenoid biosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 88: 7496–7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Motohashi R, Ito T, Kobayashi M, Taji T, Nagata N, et al. (2003) Functional analysis of the 37 kDa inner envelope membrane polypeptide in chloroplast biogenesis using a Ds-tagged Arabidopsis pale-green mutant. The Plant journal 34: 719–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hedden P, Thomas SG (2012) Gibberellin biosynthesis and its regulation. The Biochemical journal 444: 11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Qin G, Gu H, Ma L, Peng Y, Deng XW, et al. (2007) Disruption of phytoene desaturase gene results in albino and dwarf phenotypes in Arabidopsis by impairing chlorophyll, carotenoid, and gibberellin biosynthesis. Cell Res 17: 471–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Soll J, Kemmerling M, Schultz G (1980) Tocopherol and plastoquinone synthesis in spinach chloroplasts subfractions. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 204: 544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swiezewska E, Dallner G, Andersson B, Ernster L (1993) Biosynthesis of ubiquinone and plastoquinone in the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi membranes of spinach leaves. J Biol Chem 268: 1494–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crane FL (2010) Discovery of plastoquinones: a personal perspective. Photosynthesis research 103: 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh DP, Jermakow AM, Swain SM (2002) Gibberellins are required for seed development and pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell 14: 3133–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davies PJ (1995) Plant hormones: physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology. Kluwer Academic [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olszewski N, Sun TP, Gubler F (2002) Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. The Plant cell 14 Suppl: S61–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hedden P, Kamiya Y (1997) GIBBERELLIN BIOSYNTHESIS: Enzymes, Genes and Their Regulation. Annual review of plant physiology and plant molecular biology 48: 431–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graebe JE (1987) Gibberellin biosynthesis and control. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 38: 419–465. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamaguchi S, Kamiya Y (2000) Gibberellin biosynthesis: its regulation by endogenous and environmental signals. Plant and Cell Physiology 41: 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun TP, Kamiya Y (1994) The Arabidopsis GA1 locus encodes the cyclase ent-kaurene synthetase A of gibberellin biosynthesis. The Plant cell 6: 1509–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yamaguchi S, Sun T, Kawaide H, Kamiya Y (1998) The GA2 locus of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes ent-kaurene synthase of gibberellin biosynthesis. Plant physiology 116: 1271–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tian L, DellaPenna D, Dixon RA (2007) The pds2 mutation is a lesion in the Arabidopsis homogentisate solanesyltransferase gene involved in plastoquinone biosynthesis. Planta 226: 1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Venkatesh TV, Karunanandaa B, Free DL, Rottnek JM, Baszis SR, et al. (2006) Identification and characterization of an Arabidopsis homogentisate phytyltransferase paralog. Planta 223: 1134–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Soderlund C, Descour A, Kudrna D, Bomhoff M, Boyd L, et al. (2009) Sequencing, mapping, and analysis of 27,455 maize full-length cDNAs. PLoS genetics 5: e1000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gleave AP (1992) A versatile binary vector system with a T-DNA organisational structure conducive to efficient integration of cloned DNA into the plant genome. Plant Mol Biol 20: 1203–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holsters M, Waele D, Depicker A, Messens E, Montagu M, et al. (1978) Transfection and transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Molec Gen Genet 163: 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chao Y, Kang J, Sun Y, Yang Q, Wang P, et al. (2009) Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel gene encoding zinc finger protein from Medicago sativa L. Mol Biol Rep 36: 2315–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang XW, Zhao QY, Luan JB, Wang YJ, Yan GH, et al. (2012) Analysis of a native whitefly transcriptome and its sequence divergence with two invasive whitefly species. BMC genomics 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang XW, Luan JB, Li JM, Su YL, Xia J, et al. (2011) Transcriptome analysis and comparison reveal divergence between two invasive whitefly cryptic species. BMC genomics 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon A, Hannon G (2010) Fastx-toolkit. FASTQ/A short-reads pre-processing tools (unpublished) http://hannonlabcshledu/fastx_toolkit/.

- 31. Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, et al. (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome biology 14: R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xing S, Miao J, Li S, Qin G, Tang S, et al. (2010) Disruption of the 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) gene results in albino, dwarf and defects in trichome initiation and stomata closure in Arabidopsis. Cell Research 20: 688–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lichtenthaler HK (1987) Chlorophyll Fluorescence Signatures of Leaves during the Autumnal Chlorophyll Breakdown. Journal of Plant Physiology 131: 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Teng N, Wang J, Chen T, Wu X, Wang Y, et al. (2006) Elevated CO2 induces physiological, biochemical and structural changes in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. The New phytologist 172: 92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cervera M (2004) Histochemical and Fluorometric Assays for uidA (GUS) Gene Detection. In: L Peña, editor editors. Transgenic Plants: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press. pp. 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yadegari R, Paiva G, Laux T, Koltunow AM, Apuya N, et al. (1994) Cell Differentiation and Morphogenesis Are Uncoupled in Arabidopsis raspberry Embryos. The Plant cell 6: 1713–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lindgren LO, Stalberg KG, Hoglund AS (2003) Seed-specific overexpression of an endogenous Arabidopsis phytoene synthase gene results in delayed germination and increased levels of carotenoids, chlorophyll, and abscisic acid. Plant physiology 132: 779–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cunningham FX, Pogson B, Sun Z, McDonald KA, DellaPenna D, et al. (1996) Functional analysis of the beta and epsilon lycopene cyclase enzymes of Arabidopsis reveals a mechanism for control of cyclic carotenoid formation. The Plant cell 8: 1613–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Estevez JM, Cantero A, Romero C, Kawaide H, Jimenez LF, et al. (2000) Analysis of the expression of CLA1, a gene that encodes the 1-deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate synthase of the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant physiology 124: 95–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tholl D, Kish CM, Orlova I, Sherman D, Gershenzon J, et al. (2004) Formation of Monoterpenes in Antirrhinum majus and Clarkia breweri Flowers Involves Heterodimeric Geranyl Diphosphate Synthases. The Plant Cell Online 16: 977–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Keller Y, Bouvier F, d'Harlingue A, Camara B (1998) Metabolic compartmentation of plastid prenyllipid biosynthesis. European Journal of Biochemistry 251: 413–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Norris SR, Shen X, DellaPenna D (1998) Complementation of the Arabidopsis pds1 mutation with the gene encoding p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase. Plant physiology 117: 1317–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P (1999) Molecular cloning and functional expression of gibberellin 2- oxidases, multifunctional enzymes involved in gibberellin deactivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96: 4698–4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barrero JM, Piqueras P, Gonzalez-Guzman M, Serrano R, Rodriguez PL, et al. (2005) A mutational analysis of the ABA1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana highlights the involvement of ABA in vegetative development. Journal of experimental botany 56: 2071–2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang S, Barron C, Schiefelbein J, Chen JG (2010) Distinct relationships between GLABRA2 and single-repeat R3 MYB transcription factors in the regulation of trichome and root hair patterning in Arabidopsis. The New phytologist 185: 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z (2010) agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic acids research 38: W64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang X, Zhang X, Yang S (2009) A novel chloroplast-localized protein EMB1303 is required for chloroplast development in Arabidopsis. Cell Res 19: 1205–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hsieh MH, Goodman HM (2005) The Arabidopsis IspH homolog is involved in the plastid nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Plant physiology 138: 641–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Barber J, Andersson B (1994) Revealing the blueprint of photosynthesis. Nature 370: 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schomburg FM, Bizzell CM, Lee DJ, Zeevaart JA, Amasino RM (2003) Overexpression of a novel class of gibberellin 2-oxidases decreases gibberellin levels and creates dwarf plants. The Plant cell 15: 151–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suo H, Ma Q, Ye K, Yang C, Tang Y, et al. (2012) Overexpression of AtDREB1A causes a severe dwarf phenotype by decreasing endogenous gibberellin levels in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr]. PloS one 7: e45568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chien JC, Sussex IM (1996) Differential regulation of trichome formation on the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces by gibberellins and photoperiod in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant physiology 111: 1321–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Perazza D, Vachon G, Herzog M (1998) Gibberellins promote trichome formation by Up-regulating GLABROUS1 in arabidopsis. Plant physiology 117: 375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yaxley JR, Ross JJ, Sherriff LJ, Reid JB (2001) Gibberellin biosynthesis mutations and root development in pea. Plant physiology 125: 627–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Inada S, Tominaga M, Shimmen T (2000) Regulation of root growth by gibberellin in Lemna minor. Plant & cell physiology 41: 657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wittwer SH, Bukovac MJ, Sell HM, Weller LE (1957) Some Effects of Gibberellin on Flowering and Fruit Setting. Plant physiology 32: 39–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wittwer SH, Bukovac MJ (1957) Gibberellin Effects on Temperature and Photoperiodic Requirements for Flowering of Some Plants. Science 126: 30–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Michaels SD, Amasino RM (1999) The gibberellic acid biosynthesis mutant ga1-3 of Arabidopsis thaliana is responsive to vernalization. Developmental genetics 25: 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lin CC, Chu CF, Liu PH, Lin HH, Liang SC, et al. (2011) Expression of an Oncidium gene encoding a patatin-like protein delays flowering in Arabidopsis by reducing gibberellin synthesis. Plant & cell physiology 52: 421–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Domagalska MA, Sarnowska E, Nagy F, Davis SJ (2010) Genetic analyses of interactions among gibberellin, abscisic acid, and brassinosteroids in the control of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. PloS one 5: e14012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ye N, Zhang J (2012) Antagonism between abscisic acid and gibberellins is partially mediated by ascorbic acid during seed germination in rice. Plant signaling & behavior 7: 563–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Barrero JM, Rodriguez PL, Quesada V, Alabadi D, Blazquez MA, et al. (2008) The ABA1 gene and carotenoid biosynthesis are required for late skotomorphogenic growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, cell & environment 31: 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wang Y, Li L, Ye T, Lu Y, Chen X, et al. (2013) The inhibitory effect of ABA on floral transition is mediated by ABI5 in Arabidopsis. Journal of experimental botany 64: 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Davis SJ (2009) Integrating hormones into the floral-transition pathway of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, cell & environment 32: 1201–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liverman JL, Lang A (1956) Induction of Flowering in Long Day Plants by Applied Indoleacetic Acid. Plant physiology 31: 147–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Seed segregation in a silique from a heterozygous pds2-1 mutant plant.

(TIF)

Microscopic analysis of root hair from the pds2-1 mutant and WT Arabidopsis.

(TIF)

Trichome phenotype of leaves from pds2-1 and WT Arabidopsis.

(TIF)

Microscopic and statistical analyses of stomata from the pds2-1 mutant and WT Arabidopsis.

(TIF)

Representative TAIL-PCR analysis of heterozygous ( PDS2 / pds2 ) plants.

(TIF)

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showing loss of a major protein subunit (RuBisCo) in pds2-1 .

(TIF)

Gene expression and pigments in HST RNAi transgenic lines.

(TIF)

Primers used in RT-qPCT analyses.

(DOC)

Significant differential expression genes in WT and pds2-1 .

(DOC)

GO terms in all three categories (Biological Process, Cellular Component and Mollecular Function) generated by SEA.

(DOC)

GO terms in Sub-Cellular Structure/Components generated by PAGE.

(DOC)