Abstract

Objective

Se is an antioxidant micronutrient and has been studied for its potential role in CVD prevention. The purpose of the present study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature on the relationship between Se and hypertension.

Design

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed and OVID of studies on Se levels and hypertension or blood pressure published in English up to June 2011. Articles meeting inclusion criteria were reviewed and the following information was gathered from each publication: study setting, participant demographics, exclusion criteria, intervention if applicable, medium of Se measure, mean level of Se, outcome definition, relationship between Se and the outcome variable, significance of this relationship, and covariates. In studies that also reported glutathione peroxidase levels, we extracted results on the relationship between glutathione peroxidase and hypertension.

Results

Twenty-five articles were included. Approximately half of the studies reported no significant relationship between Se and hypertension. Of the remaining studies, about half found that higher Se levels were associated with lower blood pressure and the other half found the opposite relationship. The studies varied greatly in terms of study population, study design and Se levels measured in participants.

Conclusions

Based on the present systematic review, there is no conclusive evidence supporting an association between Se and hypertension. Randomized controlled trials and prospective studies with sufficient sample size in populations with different Se levels are needed to fully investigate the relationship between Se and hypertension.

Keywords: Selenium, Hypertension, Blood pressure

Approximately one billion people worldwide are afflicted by hypertension, hence there is a great deal of interest in the prevention and treatment of this chronic disorder( 1 ). Some studies have shown that individuals with hypertension produce more reactive oxygen species and have an impaired antioxidant defence system, both of which increase oxidative stress and lead to an ongoing, vicious cycle( 2 ). Antioxidants inhibit oxidation reactions, thereby reducing the number of free radicals produced and the amount of damage they can cause. Se, an essential trace element with antioxidant properties, was hypothesized to have a protective effect on hypertension( 3 ).

Se is a key component of glutathione peroxidase (GPx), an enzyme that prevents the oxidation of lipids and atherosclerotic plaque formation( 4 ). GPx also indirectly prevents the aggregation of platelets, thereby inhibiting blood clot formation( 5 ). There is a direct relationship between Se and GPx activity when Se concentrations are low, but GPx activity plateaus off at high Se levels( 6 ). A direct link between Se and hypertension was provided by the role of Se in Keshan disease, a disorder that occurred in regions of China where Se was severely deficient in the soil and diet( 7 ). Symptoms of Keshan disease, including hypertension, heart failure and pulmonary oedema, can be relieved by administering Se supplements( 7 ). However, various studies have shown that increasing Se levels above the recommended daily intake is not beneficial and can actually cause hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia( 8 ). Randomized trials with Se as part of multivitamin supplementation in Se-deplete areas were shown to reduce gastric cancer, stroke and overall mortality, but did not reduce the risk for hypertension, CVD or cataracts( 9 ).

Given the conflicting results regarding the relationship between Se levels and hypertension, we undertook a systematic evidence review that examines this relationship in studies conducted in numerous countries with various study designs.

Methods

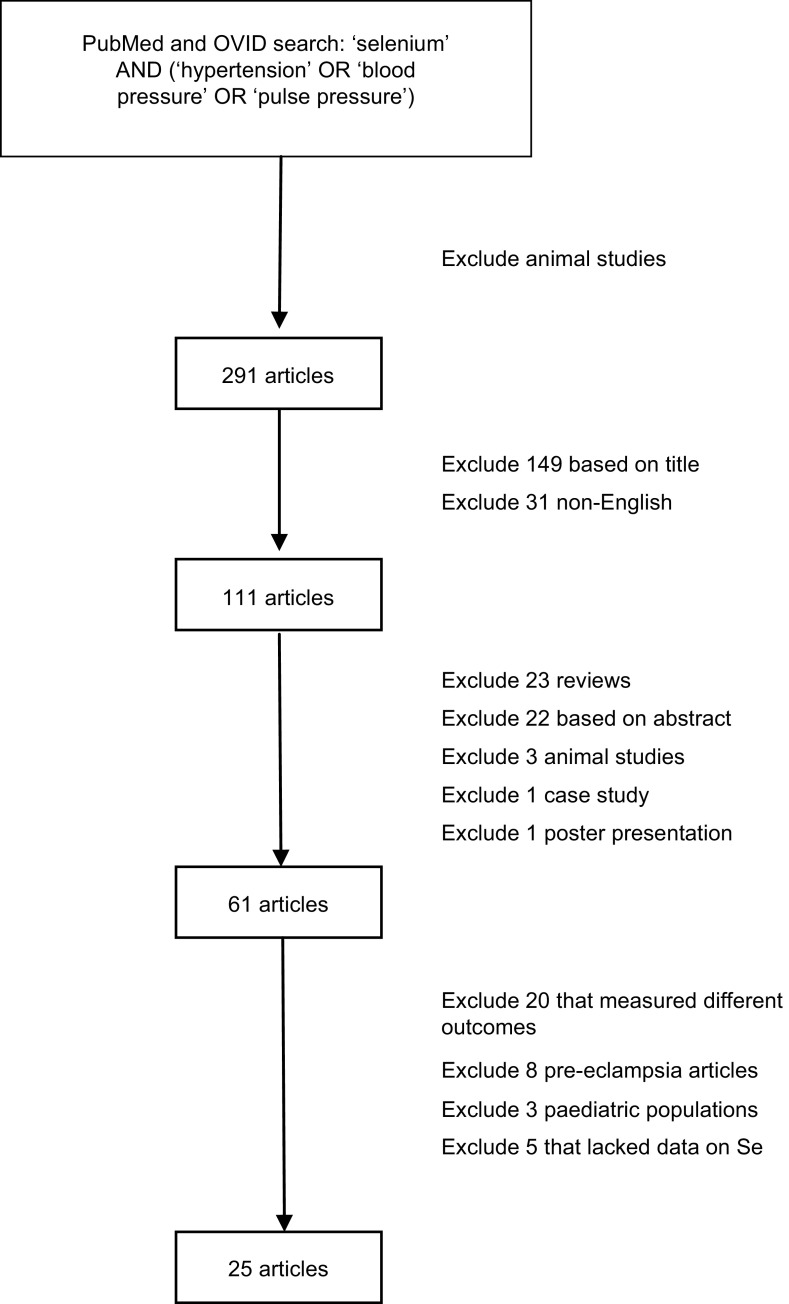

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed and OVID of all published articles as of 1 June 2011 that examined the relationship between Se and hypertension in man (Fig. 1). Search terms used were ‘selenium’ AND (‘hypertension’ OR ‘blood pressure’ OR ‘pulse pressure’). All articles that reported on animal studies were excluded. The initial search yielded 291 articles. After excluding articles that were not written in English and those that were irrelevant based on a review of article titles, 111 articles were chosen for review of the abstracts. Review articles, case studies, poster presentations, any remaining animal studies and articles with no usable information were excluded. Of the remaining sixty-one articles, those that measured a different outcome variable other than hypertension or blood pressure, used pregnant female subjects or lacked sufficient data were further excluded. Three studies on paediatric populations were further excluded since blood pressure increases continually until puberty( 10 ) and there is no standard definition of hypertension in children because their blood pressure fluctuates so much( 11 , 12 ). Twenty-five articles met the criteria for full article review and data abstraction.

Fig. 1.

Literature search on the relationship between selenium and hypertension in man

For each paper reviewed, information regarding the study setting, participant demographic information, exclusion criteria used for the study, interventional dosage for intervention studies, outcome variable and covariates were independently extracted by two reviewers (D.K. and S.G.). The level of Se measured in participants and its relationship to the outcome variable were noted. In addition, we also extracted the same information in articles that measured GPx levels. From the final multivariate model given in each paper, effect size measures, hazard ratios, parameter estimates and total or partial correlation coefficients as well as P values were recorded. The relationships were described as ‘protective’ if higher Se levels were associated with a lower risk of hypertension, ‘none’ if there was no significant relationship between Se and hypertension, or ‘harmful’ if higher Se levels were associated with a higher risk of hypertension. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0·05.

For ease of comparison across study populations, mean serum Se levels were converted to μg/l, if the original levels reported were not in those units. In three studies, the original units for the mean level of Se appeared to be incorrect as they greatly exceeded the maximum values reported in man. These were assumed to be erroneous in units and are denoted in the tables with **. For papers that expressed their mean Se level as a range or provided multiple numbers for different populations (for example, hypertensive and normotensive groups), the average of these values was used when converting the units of mean level of Se to μg/l. In those studies that measured Se levels in different media in the same group of people, we chose to include plasma measures of Se in the tables, as blood samples were the most commonly used measures in these studies.

Since the number of studies reporting randomized trials and prospective analyses was small and some of these studies lacked information necessary for meta-analysis, we conducted meta-analyses on cross-sectional studies and case–control studies where the extracted information permitted such analyses. For cross-sectional studies, outcome measures were converted to correlation coefficients if the original articles reported regression coefficients or other information using the method proposed by Thompson et al.( 13 ). Difference in mean Se levels between cases and controls was used as the outcome measure for case–control studies. Random-effect models in the software Comprehensive Meta Analysis version 2 were used for combining study results.

Results

A total of twenty-five articles reported results on the relationship between Se and hypertension in adult populations. Outcome measures used in these studies included a binary definition of hypertension with the cut-off being 140/90 mmHg, continuous systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), pulse pressure, or a combination of these variables. Table 1 provides summary information of the twenty-five studies grouped by study design. Studies reporting both longitudinal and baseline results were included in the longitudinal section only.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on the relationship between selenium levels, hypertension and blood pressure

| Mean level of Se | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study setting | Participants | Exclusion criteria | Intervention | Se measured in | Units reported | μg/l | Outcome variable | Relationship | P | Covariates |

| Randomized controlled trials including an Se component | |||||||||||

| Mark et al. (1998)( 26 ) | China | 3698 people in treatment and 3698 people in placebo (age 40–60 years) | None | Monthly dose of 15 mg β-carotene, 50 mg Se yeast, 60 mg α-tocopherol from March 1986 to April 1991 | Diet | N/A | – | SBP | None: | NS | Age, baseline SBP, baseline DBP, smoking, drinking, BMI |

| d = 0·00 (95 % CI −0·59, 0·60) | |||||||||||

| DBP | None: | NS | |||||||||

| d = 0·26 (95 % CI −0·09, 0·62) | |||||||||||

| Shargorodsky et al. (2010)( 27 ) | Israel | 70 people (36 treated with antioxidants, 34 without antioxidants) aged 55–68 years; all had to have CV risk factors | History of CVD, major surgery within 6 months preceding study, unbalanced endocrine disease, liver or kidney abnormalities | Vitamin C (500 mg), vitamin E (200 IU), coenzyme Q10 (60 mg), Se (100 μg) for 6 months | Diet | N/A | -– | SBP | Protective: | P < 0·001 | Age, sex, BMI, presence of CV risk factors, baseline BP level, arterial elasticity parameters |

| d = −6·1 | |||||||||||

| DBP | Protective: | P = 0·034 | |||||||||

| d = −2·5 | |||||||||||

| Singh et al. (1992)( 28 ) | UK | 463 people (231 in intervention group, 232 in control group), mean age 46·0 and 47·8 years, respectively; all had to have risk factors of CHD | Diarrhoea, dysentery, cancer, blood urea >40 mg/dl | Control group: AHA Step I diet (Se: 83·3 μg/d); intervention group: F&V 400 g/d in addition to control diet (Se: 112·6 μg/d) | Diet | N/A | – | SBP, % change from baseline | Protective: | P < 0·001 | Sex, serum cholesterol, BMI |

| d = −6·1 (95 % CI 1·8−11·1) | |||||||||||

| DBP, % change from baseline | Protective: | P < 0·001 | |||||||||

| d = −8·9 (95 % CI 2·0−12·0) | |||||||||||

| Prospective studies | |||||||||||

| Arnaud et al. (2007)( 29 ) | France | 751 people aged 59–71 years, 9-year follow-up | None | None | Blood | 1·10 μmol/l | 86·9 | Se decrease from baseline | None: | NS | None |

| β = −0·005 (se 0·022) for development of HT | (P = 0·81) | ||||||||||

| Nawrot et al. (2007)( 30 ) | Belgium | 346 males aged ≥20 years, 5·2-year follow-up | Urinary volume or creatinine excretion outside published limits | None | Blood | 117·0 μg/l | 117·0 | HT (BP ≥ 130/85 mmHg or on medication) | Protective: | P = 0·0013 | Age, BMI, smoking, 24 h urinary excretion of Na and K, menopausal status, baseline SBP, DBP |

| HR = 0·63 with each unit increase in Se of 20 μg/l | |||||||||||

| 373 females aged ≥20 years, 5·2-year follow-up | None: | NS | |||||||||

| HR = 1·08 with each unit increase in Se of 20 μg/l | (P = 0·41) | ||||||||||

| AStranges et al. (2011)( 21 ) | Southern Italy | 281 normotensive males aged 44–57 years, 8-year follow-up | None | None | Serum | 77·5 μg/l | 77·5 | Development of HT | None (results not shown) | NS | Age, BMI, cigarette smoking, physical activity, use of lipid-lowering medication; baseline value of total cholesterol |

| CXun et al. (2011)( 15 ) | USA | 3883 people aged 18–30 years | Implausible total energy intake, pregnant women, HT at baseline | None | Toenail | 0·86 μg/g | – | HT (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medications) | Significant interaction with n-3 fatty acids. Independent Se effect not reported | Age, gender, ethnicity, study centre, BMI, education, smoking, alcohol, physical activity, family history of HT, total energy, Na, α-linolenic acid, linoleic acid | |

| Case–control studies | |||||||||||

| Coudray et al. (1997)( 22 ) | Nantes, France | 398 males (169 with HT, 229 with no major chronic diseases or risk factors) aged 59–71 years | None | None | Plasma | 1·12 μmol/l in hypertensives, 1·05 μmol/l in controls | 85·7 | Se | Harmful (higher Se in hypertensives than controls) | P < 0·01 | None |

| 553 females (248 with HT, 305 with no major chronic diseases or risk factors) aged 59–71 years | 1·08 μmol/l in hypertensives, 1·10 μmol/l in controls | 86·1 | Se | None | NS | ||||||

| Li et al. (2007)( 31 ) | China (Zhoukoudian area, Beijing) | 401 people (108 with HT, 293 controls) aged 15–84 years | Pregnant women, serious disease | None | Serum | 70·02 μg/l in hypertensives, 76·85 μg/l in controls | 75·01 | Se | Protective (lower Se in hypertensives than controls) | P = 0·022 | None |

| DMihailovic et al. (1998)( 32 ) | Yugoslavia | 37 people (20 with arterial HT, 17 controls) aged 41–66 years | None | None | Whole blood, plasma | 0·780 uM/l in hypertensives, 1·059 uM/l in controls in plasma (assumed μmol/l)** | 72·6 | Se and GPx | Protective (lower Se in hypertensives than controls) | P < 0·005 | None |

| CPavao et al. (2006)( 33 ) | Portugal | 57 males (7 hypertensive, 50 normotensive) aged 20–60 years | None | None | Serum | 91 μg/l in normotensive, 87 μg/l in hypertensive | 88·5 | Se and GPx | None | NS | None |

| ERusso et al. (1998)( 2 ) | Italy | 205 people (105 hypertensive, 100 normotensive) aged 29–61 years | Chronic disease, acute intercurrent illness, pregnant women, taking any drug including contraceptive pills, secondary HT | None | Serum | 1·13 mmol/l in hypertensive, 1·16 mmol/l in normotensive (assumed μmol/l)** | 90·4 | Se and erythrocyte GPx | None | NS | Age, sex |

| Cross-sectional studies | |||||||||||

| Bergmann et al. (1998)( 34 )* | East Germany | 299 females, mean age 50·59 years | Se intake via vitamins | None | Blood | 0·98 μmol/l | 77·4 | Blood pressure | None (results not given) | NS | None |

| 361 females, mean age 50·59 years | 1·19 μmol/l | 94·0 | Blood pressure | None (results not given) | NS | ||||||

| Bukkens et al. (1990)( 35 ) | Netherlands | 82 people aged 40–75 years | History of CV event and/or heart surgery, treatment in the last 5 years for kidney or lung disease, alcohol or drug abuse, age >75 years, abnormal diet, not Dutch nationality | None | Plasma, erythrocyte, toenail | 106·4 μg/l in plasma; 0·59 μg/g Hb in erythrocytes; 0·78 ppm in toenail | 106·4 | SBP | None: | NS | Age, gender |

| β = 0·0719 (se 0·1286) | |||||||||||

| DBP | None: | NS | |||||||||

| β = 0·0787 (se 0·195) | |||||||||||

| Deguchi (1985)( 36 ) | Japan | 274 males aged 20–83 years | None | None | Blood | 132 ng/ml | 132·0 | DBP | None | NS | Age |

| SBP | None | NS | |||||||||

| 419 females aged 20–82 years | Pregnant females | 122 ng/ml | 122·0 | DBP | None | NS | |||||

| SBP | None | NS | |||||||||

| Jossa et al. (1991)( 37 ) | Southern Italy | 364 males aged 21–59 years | None | None | Blood | 28–187 μg/l | 86·1 | SBP | None: | NS | Age, BMI |

| r = 0·034 | |||||||||||

| DBP | None: | NS | |||||||||

| r = 0·046 | |||||||||||

| Laclaustra et al. (2009)( 19 ) | USA | 2638 people aged 40 years and older | Pregnant women | None | Serum | 137·1 μg/l | 137·1 | SBP | Harmful: | P < 0·001 | Sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI, education, smoking, cotinine concentration, menopausal status, vitamin/mineral supplements, antihypertensive medication |

| Q5 to Q1 adjusted Δ = 6·3 (95 % CI 3·4, 9·2) | |||||||||||

| DBP | Harmful: | P = 0·004 | |||||||||

| Q5 to Q1 adjusted Δ = 2·8 (95 % CI 1·1, 4·6) | |||||||||||

| Pulse pressure | Harmful: | P < 0·001 | |||||||||

| Q5 to Q1 adjusted Δ = 4·6 (95 % CI 1·8, 7·4) | |||||||||||

| Parizadeh et al. (2009)( 38 ) | Iran | 283 people (152 with angiographically defined CAD) aged 41–64 years | None | None | Serum | 111·8 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 111·8 | SBP | None | NS | None |

| DBP | None | NS | |||||||||

| 283 people (61 with normal angiogram) aged 41–64 years | 112·3 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 112·3 | SBP | None | NS | ||||||

| DBP | None | NS | |||||||||

| 283 people (70 controls) aged 41–64 years | 104·2 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 104·2 | SBP | None | NS | ||||||

| DBP | None | NS | |||||||||

| Pemberton et al. (2009)( 39 ) | UK | 94 females (46 with rheumatoid arthritis) aged 50–59 years | None | None | N/A | 84·55 μg/l | 84·6 | SBP | None: | NS | None |

| r = 0·191 | |||||||||||

| 94 females (48 controls) aged 50–59 years | 91·14 μg/l | 91·1 | SBP | None: | NS | ||||||

| r = −0·24 | |||||||||||

| Robinson et al. (1983)( 40 ) | New Zealand | 230 people aged 24–58 years | None | None | Whole blood, erythrocyte, plasma | 61 ng/ml in whole blood; 73 ng/ml in erythrocytes; 49 ng/ml in plasma | 49·0 | SBP | None | NS | None |

| DBP | None | NS | |||||||||

| Salonen et al. (1988)( 41 ) | Eastern Finland | 722 males, mean age 54 years | HT, cerebrovascular diasease, antihypertensive medication | None | Serum | 85·7 μg/l | 85·7 | SBP | Protective: | P = 0·0024 | BMI, urinary excretion of nicotine metabolites, HT in siblings, serum Zn, Mg, Cu, plasma ionized Ca, liver disease, plasma renin activity, MMPI rejection scale, work pressures, smoking |

| β = −0·109 | |||||||||||

| DBP | None: | NS | |||||||||

| β = −0·060 | (P = 0·0886) | ||||||||||

| BSuadicani et al. (1992)( 23 ) | Denmark | 3041 males aged 53–74 years | Non-fatal AMI, angina pectoris, previous stroke, intermittent claudication | None | Serum | 1·17 μmol/l in IHD patients, 1·19 μmol/l in controls | 93·2 | HT (BP > 150/100 mmHg or on medication) | Harmful: | P = 0·003 | Age |

| partial r = 0·054 | |||||||||||

| Telisman et al. (2001)( 42 ) | Croatia | 154 males aged 19–53 years | Occupational exposure to metals, use of antihypertensive medications or those containing Se, diabetes, CVD, renal disease, hyperthyroidism, adrenogenital syndrome, primary aldosteronism, and other diseases that could influence BP or metal metabolism | None | Serum | 73·6 μg/l | 73·6 | SBP | None | NS | None |

| DBP | None | NS | |||||||||

| Virtamo et al. (1985)( 43 ) | Western Finland | 582 males aged 55–74 years | None | None | Serum | 47·5 μg/l | 47·5 | SBP | None: | NS | Age |

| r = −0·03 | |||||||||||

| DBP | None: | NS | |||||||||

| r = 0·02 | |||||||||||

| Eastern Finland | 528 males age 55–74 years | 63·3 μg/l | 63·3 | SBP | None: | NS | |||||

| r = 0·05 | |||||||||||

| DBP | None: | NS | |||||||||

| r = 0·02 | |||||||||||

CV, cardiovascular; HT, hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease, AMI, acute myocardial infarction; BP, blood pressure; N/A, not applicable; AHA, American Heart Association; F&V, fruits and vegetables; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GPx, glutathione peroxidise; NS, P ≥ 0·05.

Definition of hypertension was not given unless otherwise noted: ASBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg or current antihypertensive drug treatment; Breceiving antihypertensive treatment or having BP ≥ 150/100 mmHg; CSBP ≥ 140 mmHg and DBP ≥ 90 mmHg or current use of antihypertensive medications; Dsecond- or third-degree HT using the classification of the World Association of Cardiologists; E>135/85 mmHg.

Measures of association: d = difference in BP between treatment and control groups; β = regression parameter estimate from linear regression models; HR = hazard ratio; r = correlation coefficient; Δ = difference in BP between two quintile groups (Q5, fifth quintile; Q1, first quintile).

*No numerical data provided.

**Units were assumed to be something other than what was given in the paper.

There were no published randomized controlled trials (RCT) with Se as the only intervention agent. There were three RCT that included Se as part of the intervention in dietary supplementation. One study co-administered Se with vitamin C, vitamin E and coenzyme Q10. Another administered Se in the form of fruits and vegetables so participants also received vitamins A, C and E, carotene, Cu, Mg and dietary fibre. In both cases, SBP and DBP were lowered significantly in the intervention groups. In addition, both of these studies enrolled only subjects carrying cardiovascular risk factors. A third and much larger RCT that administered Se with β-carotene and α-tocopherol, however, found no difference in blood pressure between intervention and control groups.

Four studies utilized the prospective study design where the development of hypertension was the outcome. One study found a significant protective effect of Se on incident hypertension in young adult males, but no significant relationship in females. The remaining three studies reported a non-significant association between Se and hypertension. In addition, one of the three studies reported a significant interaction between n-3 fatty acids and Se on hypertension risk.

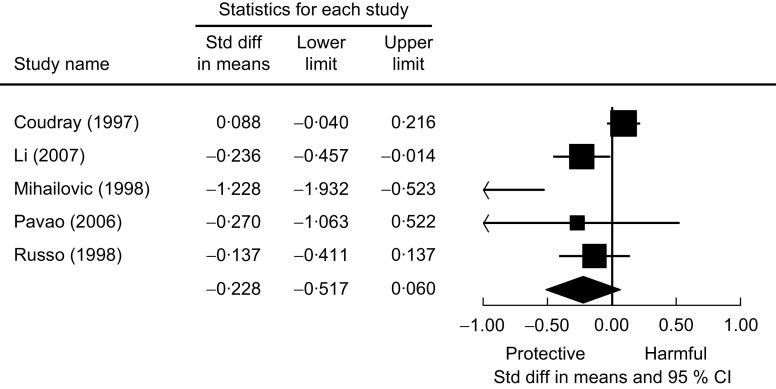

Five studies used the case–control study design and compared Se levels between hypertensive subjects and normal controls. Two studies reported significantly lower Se levels in hypertensive subjects for both males and females, one study found significantly higher Se levels in hypertensive subjects but in males only, and the other two studies found no relationship. Figure 2 presents the meta-analysis of these five studies using random-effect models. There is no overall difference in Se levels between hypertensive and normotensive subjects, as the pooled mean difference was estimated to be −0·228 (95 % CI −0·517, 0·060) μg/l.

Fig. 2.

The association of selenium with hypertension from case–control studies. Random-effects meta-analysis showing the standard difference (std diff; and 95 % confidence interval) in mean plasma selenium level (μg/l) between hypertensive subjects and normal controls; the size of the square indicates the weight of each study in the analysis, the horizontal lines represent the 95 % CI and the diamond represents the pooled mean difference (its width represents the 95 % CI of the pooled mean difference)

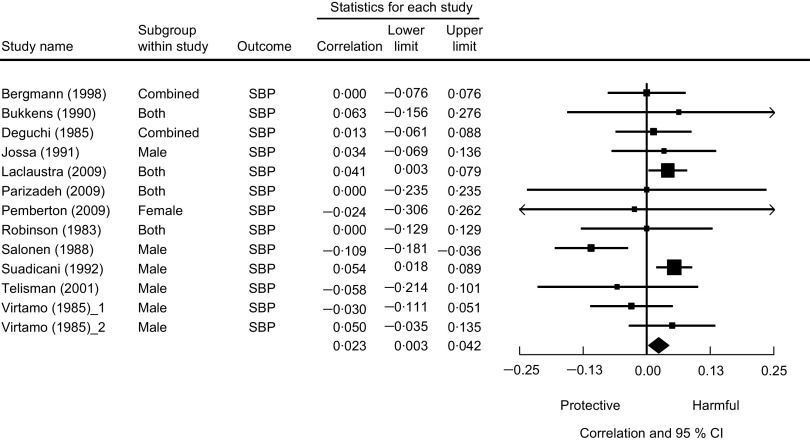

Cross-sectional analysis was used in twelve studies. Of these, nine studies found no significant association of Se with either SBP or DBP. Two studies found higher Se levels associated with higher blood pressure, while one study found the opposite relationship. We present a meta-analysis based on these cross-sectional studies in Fig. 3. The pooled correlation coefficient between Se and SBP was not statistically significant (r = 0·01, 95 % CI −0·02, 0·04).

Fig. 3.

The association between selenium and systolic blood pressure from cross-sectional studies. Random-effects meta-analysis showing the correlation coefficient (and 95 % confidence interval) between mean plasma selenium level and systolic blood pressure; the size of the square indicates the weight of each study in the analysis, the horizontal lines represent the 95 % CI and the diamond represents the pooled correlation coefficient (its width represents the 95 % CI of the pooled correlation coefficient)

Seven of the twenty-five studies measured GPx levels as well as Se in their study population (Table 2). These studies looked at the relationship between GPx and SBP, DBP, hypertension, or a combination of the three. Of these, only one study showed a protective relationship between Se and hypertension while all others showed no relationship. When examining the relationship between GPx and hypertension in these same studies, three of the four case–control studies showed lower GPx levels in hypertensive subjects than controls and one study that measured GPx in erythrocytes found higher GPx levels in hypertensive subjects than controls.

Table 2.

Comparison of selenium and glutathione peroxidase levels in man in relation to hypertension and/or blood pressure

| Study | Mean level of Se (units given in paper) | Mean level of Se (μg/l) | GPx measured in | Mean level of GPx activity (units given in paper) | Mean level of GPx activity (U/g Hb) | Outcome variable | Se–HT relationship | P | GPx–HT relationship | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case–control studies | ||||||||||

| Djordjevic et al. (1998)( 44 ) | N/A | – | Plasma | 19·60 uM·min·mg Hb/NADPH in hypertensives, 28·64 uM·min·mg Hb/NADPH in controls | 24·12 | Se-dependent GPx | N/A | N/A | Protective (lower GPx in hypertensive subjects than controls) | P < 0·001 |

| DMihailovic et al. (1998)( 32 ) | 0·780 μM/l in hypertensives, 1·059 μM/l in controls (assumed μmol/l)** | 72·6 | Plasma | 2·116 ukat/l in hypertensives, 2·886 ukat/l in controls | – | Se and GPx | Protective (−26·3 % change from control) | P < 0·005 | Protective (lower GPx in hypertensive subjects than controls) | P < 0·001 |

| CPavao et al. (2006)( 33 ) | 87 μg/l in hypertensives, 90 μg/l in controls | 88·5 | Serum | 35 U/g Hb in hypertensives, 48 U/g Hb in controls | 41·5 | Se and GPx | None | NS | Protective (lower GPx in hypertensive subjects than controls) | P < 0·05 |

| ERusso et al. (1988)( 2 ) | 1·13 mmol/l in hypertensives, 1·16 mmol/l in controls** | 90·4 | Erythrocytes | 7·45 IU/g Hb in hypertensives, 6·58 IU/g Hb in controls | 7·015 | Se and GPx | None | NS | Harmful (higher GPx in hypertensive subjects than controls) | P < 0·005 |

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||||||

| Bukkens et al. | 106·4 μg/l | 106·4 | Erythrocytes | 28 U/g Hb | 28 | SBP | None | NS | None | NS |

| (1990)( 35 ) | 106·4 μg/l | 106·4 | Erythrocytes | 28 U/g Hb | 28 | DBP | None | NS | None | NS |

| Parizadeh et al. | 111·8 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 111·8 | Serum | 0·26 U/ml | – | SBP | None | NS | None | NS |

| (2009)( 38 ) | 112·3 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 112·3 | Serum | 0·26 U/ml | – | SBP | None | NS | None | NS |

| 104·2 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 104·2 | Serum | 0·36 U/ml | – | SBP | None | NS | None | NS | |

| 111·8 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 111·8 | Serum | 0·26 U/ml | – | DBP | None | NS | None | NS | |

| 112·3 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 112·3 | Serum | 0·26 U/ml | – | DBP | None | NS | None | NS | |

| 104·2 μmol/l (assumed μg/l)** | 104·2 | Serum | 0·36 U/ml | – | DBP | None | NS | None | NS | |

| Robinson et al. (1983)( 40 ) | 61 ng/ml whole blood, 73 ng/ml erythrocytes, 49 ng/ml plasma | 49 | Serum | 12·3 U/g Hb | 12·3 | SBP | None | NS | None | NS |

| 61 ng/ml whole blood, 73 ng/ml erythrocytes, 49 ng/ml plasma | 49 | Serum | 12·3 U/g Hb | 12·3 | DBP | None | NS | None | NS |

GPx, glutathione peroxidase; HT, hypertension; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; N/A, not applicable; NS, P ≥ 0·05.

Definition of hypertension was not given unless otherwise noted: CSBP ≥ 140 mmHg and DBP ≥ 90 mmHg or current use of antihypertensive medications; Dsecond- or third-degree HT using the classification of the World Association of Cardiologists; E>135/85 mmHg.

**Units were assumed to be something other than what was given in the paper.

Discussion

The present systematic literature review on Se and hypertension offered no conclusive evidence on a relationship between Se and hypertension. The review also highlighted the limited number of large RCT or prospective studies on Se and hypertension. No RCT with Se as the only intervention agent was published and the three RCT included in the review used different dietary components in addition to Se, making comparisons between studies difficult. Only one out of the four prospective studies reported a significant protective effect of Se on the development of hypertension while the remaining studies found no association between Se and hypertension.

It is likely that the heterogeneity in study design, sample size and demographic characteristics of study participants contributed to the divergence in findings. The present review also underscores the complex relationship between Se and blood pressure. It is possible that the relationship between Se and hypertension is non-linear so that in populations with low Se intake, higher Se may be protective against hypertension; while in those with high Se intake, higher Se may be associated with hypertension risk( 14 ).

Since the effect of Se on human health is channelled through GPx activities, it is highly likely that other agents with similar antioxidant properties may interact with Se on the control of blood pressure as reported in one prospective study( 15 ). In addition, it has been shown that in subjects with low Se intake, vitamin E can protect against hypertension( 16 ). Therefore, it is important that studies examining the relationship between Se and hypertension also measure other important antioxidant levels and explore potential interactive relationships with Se.

In the several studies measuring GPx activities as well as Se, a trend for a positive correlation between Se levels and GPx activity was seen. This was anticipated because Se is a component of GPx( 17 ). Increased GPx activity was found to reduce lipid peroxidation, atherosclerotic plaque formation and platelet aggregation( 4 , 5 ). Therefore, higher GPx activity is thought to be protective against hypertension, a view supported by animal studies. When comparing rats that received a high-Se diet with those that did not, higher Se intake increased GPx activity and reduced the size of myocardial infarct( 18 ). However, GPx activity plateaus at high Se levels despite a direct relationship between Se and GPx activity when Se concentrations are low( 6 ), making the effect of high Se level beyond that required for optimal GPx activity uncertain. In a study conducted in a US population with high mean serum Se concentration (137 μg/l), higher Se was found to be associated with higher blood pressure( 19 ). A possible explanation for the harmful effect of higher Se may be that excess Se overwhelms the liver and kidneys, both of which play an important role in the metabolism and excretion of Se( 20 ). Over time, the heart may have to work harder to pump more blood to these organs, leading to hypertension.

Hypertension is suspected to impair the antioxidant defence system( 2 ). Hence, a further complication leading to the diverse study findings on Se and hypertension may be a different role for Se in hypertension prevention compared with hypertension treatment. It is possible that the amount of Se for maintaining normal blood pressure may be different from the amount required in hypertensive subjects who may already have a damaged antioxidant defence system affecting the way Se and other antioxidants are metabolized and stored. In the present review, apart from the two prospective studies( 15 , 21 ) where incident hypertension was the outcome, no other studies examined the relationship between Se and blood pressure in normotensive subjects and hypertensive subjects separately. Given the large percentage of hypertensive subjects in the reviewed studies, the possibility of a reverse causation could be another source contributing to the heterogeneity in results. We also note that a harmful relationship between Se and hypertension was observed from case–control( 22 ) and cross-sectional studies( 19 , 23 ).

Many studies included in our review were conducted in small sample sizes, thus suffering from insufficient power to detect a significant relationship between Se and blood pressure or hypertension. We decided to include all studies regardless of sample size in our review to provide the full range of studies conducted on this subject. However, if we were to restrict the review to the nine largest studies with a minimum sample size of 700, we would still have five studies finding no association, two finding higher Se to be protective and another two studies finding higher Se to be harmful for hypertension. It seems that the divergence in results remains even if we only consider studies with large sample sizes.

Our review points to a potential gender difference in the relationship between Se and hypertension. In eight studies that separately reported results for males and females, two showed a significant protective effect, two showed a harmful effect and the rest showed no association between Se and hypertension. In females, however, all of the studies found no relationship. This gender difference could be due to the antioxidant properties of oestrogen, which reduces the number of superoxide anions and results in less endothelial dysfunction in females( 24 , 25 ). Future studies will need to carefully examine a potential gender difference and plausible mechanisms for such difference.

Our review suggests that future studies investigating the relationship between Se and hypertension need to measure multiple antioxidants as well as Se in prospective designs and that the association between Se and blood pressure needs to be examined separately in hypertensive and normotensive subjects. It is also necessary to conduct more research including laboratory studies of animals focusing on the relationship between the antioxidant system and the blood pressure-regulating mechanism to provide better targets for epidemiological studies and randomized trials.

The current review has a number of strengths over previous literature reviews. Our review offered a comprehensive summary of up-to-date results on Se, hypertension and blood pressure. We also attempted to extract information on cohort characteristics, study design and other potentially relevant information from each study so that potential factors accounting for the diverse findings may be compared. There are also limitations to the review. The first is that our search terms were limited to ‘hypertension’ and ‘blood pressure’, thus studies that reported on other CVD without using blood pressure or hypertension as an outcome were not included. Second, our review excluded non-English articles and may bias the review results towards research publications in English. Since thirty-one non-English articles were identified after the initial search results out of 291 articles, assuming the same rate of usable information contained in the non-English articles as in the English articles, we anticipate missing approximately 10 % of articles (approx. three articles) with usable results on Se and hypertension.

Conclusion

The present systematic literature review does not offer conclusive evidence supporting an association between Se levels and blood pressure or hypertension. Future research focusing on the mechanism between the antioxidant system and blood pressure regulation would provide valuable input and better targets for RCT and prospective studies. These future studies should also be designed to address the role of Se in hypertension prevention separately from its role in hypertension treatment. In addition to measuring Se levels, future studies should also measure other antioxidants and GPx levels, if possible, to explore potential interactions with Se and to determine the mechanism underlying a potential relationship between Se and blood pressure.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: D.K. was supported by a Medical Student Training in Aging Research Award from the American Federation of Aging Research. The research was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 AG019181) and P30 AG10133. Ethics: Ethical approval was not required as the study was a systematic review of published literature. Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest. Authors’ contributions: literature search, D.K. and S.G.; literature review and summarization of results, D.K., S.G. and L.Y.; manuscript, D.K., S.G., H.C.H. and L.Y.

References

- 1. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K et al. (2005) Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 365, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Russo C, Olivieri O, Girelli D et al. (1998) Anti-oxidant status and lipid peroxidation in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertens 16, 1267–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rayman MP (2000) The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet 356, 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wojcicki J, Rozewicka L, Barcew-Wiszniewska B et al. (1991) Effect of selenium and vitamin E on the development of experimental atherosclerosis in rabbits. Atherosclerosis 87, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bryant WR, Bailey JM, King JC et al. (1981) Altered platelet glutathione peroxidase activity and arachidonic acid metabolism during selenium repletion in a controlled human study. In Selenium in Biology and Medicine, pp. 395–399 [JE Spallholz, JL Martin & HE Ganther, editors]. Westport, CT: Avi Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rea HM, Thomson CD, Campbell DR et al. (1979) Relation between erythrocyte selenium concentrations and glutathione peroxidase (EC 1.11.1.9) activities of New Zealand residents and visitors to New Zealand. Br J Nutr 42, 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boosalis MG (2008) The role of selenium in chronic disease. Nutr Clin Pract 23, 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stranges S, Navas-Acien A, Rayman MP et al. (2010) Selenium status and cardiometabolic health: state of the evidence. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 20, 754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang HY, Caballero B, Chang S et al. (2006) The efficacy and safety of multivitamin and mineral supplement use to prevent cancer and chronic disease in adults: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference. Ann Intern Med 145, 372–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shankar RR, Eckert GJ, Saha C et al. (2005) The change in blood pressure during pubertal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90, 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scharer K (1987) Hypertension in children and adolescents – 1986. Pediatr Nephrol 1, 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. DeSanto NG, Trevisan M, Capasso G et al. (1988) Blood pressure and hypertension in childhood: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Kidney Int Suppl 25, S115–S118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thompson S, Ekelund U, Jebb S et al. (2011) A proposed method of bias adjustment for meta-analyses of published observational studies. Int J Epidemiol 40, 765–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Navas-Acien A, Bleys J & Guallar E (2008) Selenium intake and cardiovascular risk: what is new? Curr Opin Lipidol 19, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xun P, Hou N, Daviglus M et al. (2011) Fish oil, selenium and mercury in relation to incidence of hypertension: a 20-year follow-up study. J Intern Med 270, 175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomson CD & Robinson MF (1980) Selenium in human health and disease with emphasis on those aspects peculiar to New Zealand. Am J Clin Nutr 33, 303–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rotruck JT, Pope AL, Ganther HE et al. (1973) Selenium: biochemical role as a component of glutathione peroxidase. Science 179, 588–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tanguy S, Morel S, Berthonneche C et al. (2004) Preischemic selenium status as a major determinant of myocardial infarct size in vivo in rats. Antioxid Redox Signal 6, 792–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laclaustra M, Navas-Acien A, Stranges S et al. (2009) Serum selenium concentrations and hypertension in the US Population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2, 369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suzuki Y, Hashiura Y, Matsumura K et al. (2010) Dynamic pathways of selenium metabolism and excretion in mice under different selenium nutritional statuses. Metallomics 2, 126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stranges S, Galletti F, Farinaro E et al. (2011) Associations of selenium status with cardiometabolic risk factors: an 8-year follow-up analysis of the Olivetti Heart study. Atherosclerosis 217, 274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coudray C, Roussel AM, Mainard F et al. (1997) Lipid peroxidation level and antioxidant micronutrient status in a pre-aging population; correlation with chronic disease prevalence in a French epidemiological study (Nantes, France). J Am Coll Nutr 16, 584–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Suadicani P, Hein HO & Gyntelberg F (1992) Serum selenium concentration and risk of ischaemic heart disease in a prospective cohort study of 3000 males. Atherosclerosis 96, 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dantas AP, Tostes RC, Fortes ZB et al. (2002) In vivo evidence for antioxidant potential of estrogen in microvessels of female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 39, 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salonen JT, Salonen R, Penttila I et al. (1985) Serum fatty acids, apolipoproteins, selenium and vitamin antioxidants and the risk of death from coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 56, 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mark SD, Wang W, Fraumeni JF Jr et al. (1998) Do nutritional supplements lower the risk of stroke or hypertension? Epidemiology 9, 9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shargorodsky M, Debby O, Matas Z et al. (2010) Effect of long-term treatment with antioxidants (vitamin C, vitamin E, coenzyme Q10 and selenium) on arterial compliance, humoral factors and inflammatory markers in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Nutr Metab (Lond) 7, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh RB, Rastogi SS, Ghosh S et al. (1992) The diet and moderate exercise trial (DAMET): results after 24 weeks. Acta Cardiol 47, 543–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arnaud J, Akbaraly TN, Hininger I et al. (2007) Factors associated with longitudinal plasma selenium decline in the elderly: the EVA study. J Nutr Biochem 18, 482–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nawrot TS, Staessen JA, Roels HA et al. (2007) Blood pressure and blood selenium: a cross-sectional and longitudinal population study. Eur Heart J 28, 628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li N, Gao Z, Luo D et al. (2007) Selenium level in the environment and the population of Zhoukoudian area, Beijing, China. Sci Total Environ 381, 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mihailovic MB, Avramovic DM, Jovanovic IB et al. (1998) Blood and plasma selenium levels and GSH-Px activities in patients with arterial hypertension and chronic heart disease. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 17, 285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pavao ML, Figueiredo T, Santos V et al. (2006) Whole blood glutathione peroxidase and erythrocyte superoxide dismutase activities, serum trace elements (Se, Cu, Zn) and cardiovascular risk factors in subjects from the city of Ponta Delgada, Island of San Miguel, The Azores Archipelago, Portugal. Biomarkers 11, 460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bergmann S, Neumeister V, Siekmeier R et al. (1998) Food supply abundant increase of serum selenium concentrations in middle-aged Dresden women between 1990 and 1996. DRECAN-Team. Dresden Cardiovascular Risk and Nutrition. Toxicol Lett 96–97, 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bukkens SG, de Vos N, Kok FJ et al. (1990) Selenium status and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy Dutch subjects. J Am Coll Nutr 9, 128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deguchi Y (1985) Relationships between blood selenium concentrations and grasping power, blood pressure, hematcrit, and hemoglobin concentrations in Japanese rural residents. Nippon Eiseigaku Zasshi 39, 924–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jossa F, Trevisan M, Krogh V et al. (1991) Serum selenium and coronary heart disease risk factors in southern Italian men. Atherosclerosis 87, 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Parizadeh SM, Moohebati M, Ghafoori F et al. (2009) Serum selenium and glutathione peroxidase concentrations in Iranian patients with angiography-defined coronary artery disease. Angiology 60, 186–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pemberton PW, Ahmad Y, Bodill H et al. (2009) Biomarkers of oxidant stress, insulin sensitivity and endothelial activation in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study of their association with accelerated atherosclerosis. BMC Res Notes 2, 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Robinson MF, Campbell DR, Sutherland WH et al. (1983) Selenium and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in New Zealand. N Z Med J 96, 755–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salonen JT, Salonen R, Ihanainen M et al. (1988) Blood pressure, dietary fats, and antioxidants. Am J Clin Nutr 48, 1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Telisman S, Jurasovic J, Pizent A et al. (2001) Blood pressure in relation to biomarkers of lead, cadmium, copper, zinc, and selenium in men without occupational exposure to metals. Environ Res 87, 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Virtamo J, Valkeila E, Alfthan G et al. (1985) Serum selenium and the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Am J Epidemiol 122, 276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Djordjevic VB, Grubor-Lajsic G, Jovanovic-Galovic A et al. (1998) Selenium-dependent GSH-Px in erythrocytes of patients with hypertension treated with ACE inhibitors. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 17, 277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]